Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de História da Educação

On-line version ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub Sep 13, 2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-128

Papers

Public Magistrary in Brazil: remuneration and first statutory tests1

1State University of Goiás (Brazil). jarbas.machado@ueg.br

This article discusses the remuneration of the public teaching profession in Brazil, identified in the official norms, in the period between 1759 and 1889. It shows that in the analyzed period there was no recognition of teaching activity with evidences that point to decent salary conditions, especially for those that were dedicated to the "first letters". Nonetheless, it is suggested that the first statutory and career rules for the public teaching profession regulated by the State were established in this period.

Keywords: Teacher remuneration; Teaching profession; Teacher salary increase; Teaching career

Este artigo discute a remuneração do magistério público no Brasil, identificada nas normas oficiais, considerando o período de 1759 a 1889. Trata-se de um ensaio de caráter documental e bibliográfico. Mostra que no período analisado não houve o reconhecimento da atividade docente com evidências que apontem para dignas condições salariais, principalmente para aqueles que se dedicavam às “primeiras letras”. Apesar disso, são apresentados elementos sugestivos de que nesse período tenham sido instituídas as primeiras normas estatutárias e de carreira para o magistério público regulado pelo Estado.

Palavras chave: Remuneração do magistério; Profissão docente; Valorização salarial; Carreira do magistério

Este artículo discute la remuneración del magisterio público en Brasil, identificada en las normas oficiales, en el período comprendido entre 1759 y 1889. Muestra que en el período analizado no hubo el reconocimiento de la actividad docente con evidencias que apunte a dignas condiciones salariales, principalmente para aquellos que se dedicaban a las "primeras letras". A pesar de ello, se presentan elementos sugestivos de que en ese período se establecieron las primeras normas estatutarias y de carrera para el magisterio público regulado por el Estado.

Palabras clave: Remuneración del magisterio; Profesión docente; Valorización salarial docente; Carrera del magisterio

Introduction

The origin of teaching work in Brazil, with a close connection with European civilization, particularly with the Portuguese Metropolis, dates from the arrival of the Jesuit priests in 1549. According to Azevedo (1963, p. 501) this fact “not only marks the beginning of history of education in Brazil, but inaugurates the first phase, [...] certainly the most important due to the figure of the work realized and above all the consequences that resulted from it for our culture and civilization”.

The Society of Jesus, a religious order affiliated with the Jesuits, was imcubed by the Portuguese Crown and the Catholic Church with “integrating the new lands and their 'savage' natives into the Christian and civilized world, in the service of the Faith and the Empire” (XAVIER, RIBEIRO and NORONHA, 1994, p. 40). For the maintenance of the “civilizing” services of the Society of Jesus in Brazil, in addition to subsidies from the Portuguese Crown for the installation of schools and the “redithe”, which corresponded to 10% of the taxes charged in the Colony, for its maintenance, points out Monlevade (2000) , that the Jesuits organized a self-financing system based mainly on raising cattle on the vast lands along the Brazilian coast, ceded by the Portuguese Crown and took care by indigenous and African slave labor, which over time relieved the Metropolis of its responsibility for the inauguration of what Azevedo (1963, p. 507) calls the “bases of popular education”: defense that the work of the Jesuits was not limited to the propagation of the Catholic faith, but that it also had a secular educational character and undertook to contemplate the population diversity of the time2.

Funding, be from the Metropolis or from the income generation system itself, was not intended for the remuneration of schoolmasters3, but for the maintenance and proliferation of the educational/religious system. Also because the Jesuits who dedicated themselves to teaching, according to the rules emanating from the “Ratio Studiorum”, were admitted with the “condition of spontaneously consecrating their lives to the service of God in the teaching of letters”, had a “vow of poverty”, they were not remunerated for the work performed and, therefore, did not live on wages paid by public or private employers.

Certainly, the lack of remuneration for teachers and coadjutor brothers who took care of material work, in addition to the use of slave force to work on cattle farms, among others, provided to the Jesuits a considerable expansion of their properties, coming to mean “20% of the Colony's GDP” (MONLEVADE, 2000, p. 17), which would become an object of interest to the Portuguese government as an alternative for capitalizing its economy.

According to Ribeiro (1993), for internal and external reasons Portugal was unable to advance from the mercantile to the industrial stage of the capitalist regime, reaching the 18th century with an economy in full decline. Criticism for both intellectual backwardness and economic impoverishment fell “on account of the religious who had the exclusive direction of national character and education” (AZEVEDO, 1963, p. 538).

On July 21, 1959, the Jesuits were expelled from the Portuguese kingdom and its domains as one of the main measures of the State reform implemented by the Marquis of Pombal, then Portuguese minister. For the government, the expulsion of the Society of Jesus was necessary because “a) it held economic power that should be returned to the government; b) educated the Christian in the service of the religious order and not the interests of the country” (RIBEIRO, 1993, p. 33).

When the decree of the Marquis of Pombal dispersed the priests of the Society, expelling them from the Colony and confiscating their property, all of their colleges were suddenly closed, leaving only the buildings, and it was disjointed, completely collapsing the education apparatus, set up and directed by the Jesuits in Brazilian territory. [...] at the time of their expulsion, the Jesuits [...] in the Colony had 25 residences, 36 missions and 17 colleges and seminaries, not counting minor seminaries and reading and writing schools, installed in almost all the villages and towns where the Company's houses existed. (AZEVEDO, 1963, p. 539).

According to Ribeiro (1993, p. 33) “with this public education emerges. No longer financed by the State, but which formed the individual for the Church, but financed by and for the State”. In this new perspective of public education, there is a demand for a new educational agent: the public teacher4 regulated and paid by the State.

From above-mentionet context, the following is problematized: how were public teachers paid in Brazil in the period between 1759, marked by the expulsion of the Jesuits, and 1889, end of the Empire5? What statutory elements related to teaching activity can be evidenced during this period?

It is not the intention of this study to discuss the issue of teaching in terms of its place in the capitalist system, being as a profession in the sense, for example, of Enguita (1991), as proletarianization in the sense, for example, of Monlevade (2000). ) or in other intermediate strands that deal with these analyses. It only intends to verify how the work of these State agents who started to compose the history of education in Brazil was regulated and, above all, remunerated.

Teacher remuneration in the Pombaline Reforms

According to Azevedo (1963) the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Portuguese kingdom did not mean a simple adjustment or immediate replacement of the education system. The closing of the order's activities was radical, without any proposal worthy of mention that could, at least, mitigate its absence. On the other hand, the crisis generated by the expulsion of the Jesuits provoked the approval of measures that contributed to advances in the constitution of a less confessional education, controlled by the State. In order to exercise this control, the Régio license of July 28, 1759 created the position of General Director of Studies, who should forward public competitions to royal professors and give account directly to the king, at the end of each year, on the work and teacher performance. It was also up to the general director to grant licenses for public and private teaching. All professors in the kingdom would be subordinate to him, including under penalty of warning, loss of position, fine and even exile. The official mechanisms, not only of admission, but also of monitoring and inspection of teaching work, therefore date back to the appointment of the first public teachers controlled by the State.

With regard to the constitution of public teaching statute controlled by State, understood as a set of rules directly linked to the teaching activity, in the Charter of July 28, 1759, which establishes some rules for hiring royal teachers for the classes of Latin grammar, Greek and rhetoric, the first contributions are presented. The main ones, for the purposes of this study, consist of the following points:

11. No one will be able to teach outside the aforesaid classes, either publicly or privately, without the approval and permission of the Director of Studies, who, in order to grant it, will first have the applicant examined by two royal professors of Grammar; and with the approval of the latter, he will grant him the said license, being a person in whom the requirements of good and proven customs concurrently compete; and of science and prudence; and giving her approval free of charge, without her or her signature taking the slightest stipe.

12. All said professors will carry the privilege of nobles, incorporated in common law, and especially in the Title Code of professuribus of medicis. (Order of July 28, 1759).

However, according to Azevedo (1963) it was only in 1772, that is, thirteen years after the expulsion of the Jesuits and the determination of the aforementioned Charter, that a royal order ordered the establishment of these classes (Latin, Greek and rhetoric) in Rio de Janeiro and in the main cities of the captaincies. According to the author,

Although determined by the charter of 1759 that created a directorate-general of studies in Portugal, the supervision of classes and royal schools did not begin to be carried out regularly in Brazil until 1799, already in the twilight of the 18th century, when the Portuguese government assigned to the Viceroy the general inspection of the Colony, with the right to annually appoint a teacher to visit the classes and inform him of the state of instruction. (AZEVEDO, 1963, p. 542).

For Monlevade (2000, p. 18) “from 1759 to 1772, Brazil was without schools, except for the sparse classes that some religious and lay people offered without a system or document”, which means at the same time precarious situations both in terms of working conditions and in terms of pay conditions. Furthermore, they did not comply with the decree of the 28th of July, on the basis of which no one could teach outside the classes provided by royal teachers licensed by the director general of studies.

it is certain that, from a formal point of view, of organizational the “system unity” was succeeded by fragmentation into the plurality of isolated and dispersed classes. This structure fragmentation became all the more serious as the reforming government did not know or could not recruit the teachers it needed, guarantee them a dignified situation, nor subject them to a discipline capable of introducing the necessary unity in the teaching staff. of views and efforts. (AZEVEDO, 1963, p. 543) (emphasis added).

In the Law of November 6, 1772, in the second stage of the educational reform of the Pombal Marquis, the terms of the Charter of July 28, 1759 were ratified, adding to the subjects of Latin, Greek and rhetoric, philosophy (teaching secondary). To the Masters of reading, writing and counting (primary education) there is a determination of accountability regarding the number of students they attended, as well as the academic performance of each one of them. This determination would probably be much more linked to the control of who pays than to the monitoring of student learning, because contradictorily, Dom José, the Monarch at the time, argues in the aforementioned law, that it would not be necessary for everyone to have access to the highest levels of instruction: “those who are necessarily employed in the rustic services and in the Manufacturing Arts that provide the livelihood of the Peoples, and constitute the arms and hands of the Political Body, must be deducted; the instruction of the parish priests would suffice for the people of these associations”.

For what is presented as components of a probable statutory genesis for the public teaching profession controlled by State, the following excerpts from the Law of November 6, 1772 are relevant.

I. I order: that for the aforementioned Provision of Masters Orders to be posted in these Kingdoms and their Domains for the convening of opponents to the Teaching: And that it be practiced in the future in all cases of vacancy of the Chairs.

II. Item I order: That the exams of the Masters that are made in Lisbon; when there is no president, they are carried out in the presence of a Deputy, with two Examiners appointed by the acting President [...] In the Overseas Captaincies, the exams will be carried out in the same way [...].

III. Item I order: That all the aforementioned teachers, subordinate to Meza, are obliged to send to Ella, at the end of each Academic Year, the relation names of all, and each of their respective Disciples, giving an account of the Delles Processes and morigeration; for Ella to regulate the Bureau the Certificates; [...] which you have to send by your secretary [...]

IV. [...]

V. Item I command: That the Masters of reading, writing and counting be obliged to teach not only the good form of characters, but also the general rules of Portuguese Orthography [...] at least the four kinds of Simple Arithmetic [.. .]

SAW. [...]

VII. Item I order: That individuals who are able to have teachers for their children within their own homes, as usually happens, be allowed to use said freedom [...]

VIII. Item I order: That the Persons, who wish to give Lessons through private houses, cannot do before qualifying for these Magisteriums with Exams, and approvals from the Meza; under the penalty of a hundred paid crusaders from the Jail for the first time; and for the second of the same condemnation in double, and of five years of exile to the Kingdom of Angola. (Law of November 6, 1972).

To subsidize the expenses resulting from this law, the Royal Charter of November 10, 1772 established rules regarding the educational funding system, creating the literary subsidy, specially for the payment of the Masters of First Letters.

I. I order that from this publication date onwards, are abolished and extinct all collectas, which in the Cabeções das Sizas, or in any other Books or Books of Collection, to be paid with them, Masters of Reading, and writing, or Solfa, or grammar, or any other instruction for boys: From now on, by the aforementioned teaching titles, one cannot demand from My Vassals any other contribution, other than the one I determine below.

II. Item, I order that for the said application of the same public education, instead of the aforementioned collections until now launched in charge of the Peoples; establish, as I do, the only tax: to know: in these Kingdoms, and Islands of Azores, and Madeira, of one real in each Winebasket; and four réis in each canada of Agua Ardente; one hundred and sixty cents for each barrel of Vinegar: In America, and Africa, one real in each pot of meat that is cut in the Butchers, and in them, and in Asia, ten cents in each drips canada from which they do in the Lands, under any name given to them, or that will be given to them. (Royal Letter of November 10, 1772).

The levy of the literary subsidy is the responsibility of the Municipal Councils, “whose products should be deposited, every four months, in the general fund of the Boards of Finance in order to be used in masters and teachers’ payment, nominated to public education (ALMEIDA, 2000, p. 38). Note that the author refers to masters (Masters of reading, writing and counting/primary) and to teachers (regents/secondary). This is an important finding, as they are two groups of professors with different perspectives both in terms of social prestige and in terms of received fees. The author says that the teacher, had a lifetime job, and like the magistrate, was immovable. “The holder of the role was, in a way, its owner and could, in case of illness, be replaced by an alternate of his choice, provided he had a certificate of studies in the subject taught. The holder himself paid his substitute”. (ALMEIDA, 2000, p. 40).

For the regal teachers, there was no salary markup. There is the observation that the arrival of the royal family to Brazil, in 1808, has contributed, among others, for the salaries to be significant6, however, diversified. One of the cases presented below shows that in Brazil the salary of a teacher came to represent twice what he received in Portugal.

on August 18, 1809, as can be deduced from another document, Priest João Batista, a bachelor, had been appointed professor of Geometry. The appointment letter said: [...] with a salary of 500,000 per year. [...]

On the 26th of August of the same year, the King also appointed Priest René Boiret, professor of the French language, for 400,000 per year. [...] The professor came from Portugal where he performed the same duties at the Colégio Real dos Nobres, with a salary of 200,000 [...] By a royal letter, registered and preserved in the archives of the City Council, ensure that on September 9, 1809, Priest Jean Joyce, Irish, was nominated English professor, with a salary of 400$000 a year. (ALMEIDA, 2000, p. 42)

Meanwhile, the Masters of reading, writing and counting7, royal masters, or lay masters, in the colony, who, in the terms of Azevedo (1963, p. 543), “[...] generally showed, according to testimonies of the time, not only a thick ignorance of the subjects they taught, but an absolute lack of pedagogical sense” continued hadn’t, also for this reason, neither prestige nor plausible remuneration. According to Almeida (2000, p. 43), “these institutes that started to be recruited hadn’t, in general, only a brief elementary education and had not taken exams [...]; each taught what he knew, more or less, imperfectly, and no more could be demanded of them”. Despite the determination that there would be competitions for masters, carried out directly by qualified examiners in the presence of at least one deputy, this function was granted to the religious of the colony as bishops, priest-masters and mill chaplains, “who became, later the departure of the Jesuits, the main responsible for the education of Brazilian boys” (AZEVEDO, 1963, p. 543). According to Almeida (2000, p. 46) “[...] in certain cases and under the opinion of the District Judge, the parish priests or chaplains appointed the instituters of their own parish. It was a means of increasing part of their salaries [...] derisively modest”.

Even with all the evidence of precariousness experienced by educational agents, especially the Masters of reading, writing and counting, there are arguments that the “Regal Classes” have represented an advance in the constitution of the teaching profession.

Statistically, there is no doubt that registration coverage by Jesuit schools was higher, although there are no rigorous data on which to base it. However, if wage earning is a more advanced work relation than survival by income from a slave or serve relationship, the royal classes provided an advance. It is a significant advance, as it places education as a public policy, even if limited in quantity and certainly inferior in reaching any qualitative goal. Let us try to understand the process as a historical evolution towards the constitution of an autonomous category of public teaching. (MONLEVADE, 2000, p. 18-19)

There is no doubt that the genesis and evolution of the teaching activity in Brazil, carried out by a public agent controlled by the State, involves the exercise of “Regal Classes”8. The main norms “tested” in the period, which guided (or should guide) the public contract of the teacher with the State, therefore representing a kind of formal statute, are: i) Prohibition of the activity of public or private education without the approval and license of the Director General of Studies. The license was to be gained through public examinations9; ii) Granting of the privilege of nobles, including incorporation into the Title Code of professoribus et medicis10; iii) Admission through public tender in the public competition in the presence of a competent authority and experts in the field; iv) Obligation of teachers to provide accounts of students at the end of each year for the emission of a certificate by the Bureau; v) Determination to the Masters to read, write and count so that the general rules of Portuguese orthography and at least the four fundamental arithmetic operations could be taught; vi) Permission for individuals to hire, at their own expense, teachers for their children. Even in these cases the masters would not be exempt from the obligation of public examinations; vii) Determination of severe consequences for anyone who insists on teaching without proper license11; viii) Remuneration paid by the State and exclusive financing, via literary subsidy12; and ix) Lifetime employability commitment13.

However, even considering the essays for the constitution of a statute based on the two stages of the reform (1959 and 1972), and which support both Monlevade's (2000) and Nóvoa's (1999) arguments for understanding the period as evolutionary from the point of view of professionalization or at least the functioning of the teaching activity, in Brazil this was practically unnoticed, especially on what referes to primary education. According to Almeida (2000, p. 59) “it cannot be said that the government was indifferent to primary education, but the measures taken, the decrees issued, the promulgated laws remained a dead letter for most of the country”. In this direction, the regime of classes, the distance between the Director General of Studies and the masters, the absence of inspection and especially the lentor in any intervention, among others, are according to Azevedo (1963, p. 545), “reasons why Pombal's reconstructive action only grazed school life in the Colony”.

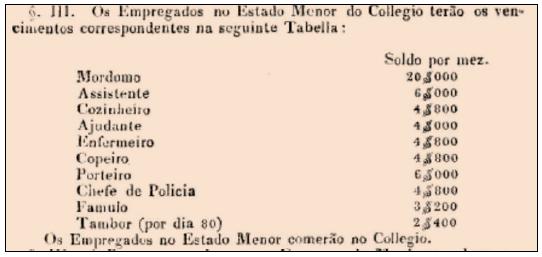

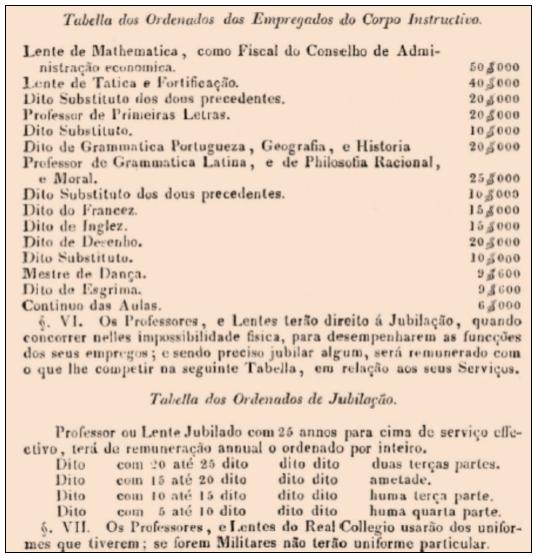

The inertia that affected the aspect of teacher remuneration during the period of the “Regal Classes”, with the rare exception of some appointments to isolated positions of secondary education, especially after the arrival of Dom João VI in the Colony, could not be considered by the absence of experience of the Portuguese government in reference of school organization and the constitution of statutes capable of regulating and at the same time remunerating educational agents. On May 18, 1816, from the Palace of Rio de Janeiro, Dom João VI approved the Statute for the creation of the Militar School da Luz in Lisbon14. Although the maintenance of this unit was not exclusively realized by the royal treasury, the Statute, in terms of form and content, can be considered a reference for this type of document for that period. Teachers' remuneration, as shown in the following Figure 1, varied according to the subject taught. In general, substitute teachers were paid only half of what a full professor was paid.

Source: License of May 18, 1816.

Figure 1 Salary table for the teaching staff of Militar School da Luz.

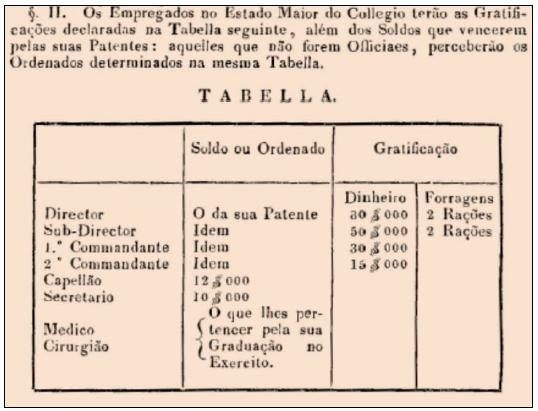

As already discussed, the teaching role of royal teachers was for the entire life and when the titular was unable to act, he paid a substitute with his own salary. In the case of Militar School Luz, teachers who could no longer teach due to illness were retired and continued to be paid by the State. Just as a reference, for comparison purposes, Figure 2, attached, shows the salaries of the employees of the Staff of the Militar School Luz.

According to the cited document, with the exception of the butler, support employees received lower wages than teachers. While the members of the State higher than the administrative body of the college, had remuneration as set out in figure 3.

Imperial propositions from 1827

The introduction of mutual schools15 in Brazil represents a different model for organizing public education activities. The first school in this model seems to have been created in the Parish of Sacramento on the premises of the Militar School in Rio de Janeiro. According to Almeida (2000, p. 57), “its foundation is due to the Minister of War and the institute's salaries were set at 500$000 per year, a high amount for his time and for his job”. However, the author emphasizes, it was a matter of appointing a person who was an expert on the subject and was probably the one introduced it in Brazil.

If in the individual or simultaneous method the teacher was the teaching agent, in the mutual method (used for more than 20 years), the students with the best performance are the monitors responsible for this function. According to Lesage (1999, p. 12) “the monitors are only one of the fundamental elements of the new method. But at the level of practices, they are the essential element or, according to Maurice Gontarde's formula, the working agent of the method” (emphasis added). According to Azevedo (1963), in a primary school with 500 students, for example, instead of the twelve teachers needed for twelve classes, each one of 40 students, more or less, it would not take more than one teacher, who would unload on 50 students of better improvement the teaching of the others distributed in decuries. The mutual schools are, therefore, from an economic point of view, a cheap alternative for the cost of public education for the period. Ironically, “A lot and quickly and without cost: the ideal for Brazil” (PEIXOTO apud AZEVEDO, 1963, p. 564).

Probably thinking of a school organization based on the Lancaster method, Dom Pedro I approved the Law of October 15, 1827. In it, the Emperor determines that “In all cities, towns and populous places, there will be schools of first letters that are necessary” (Article 1). At the same time it gives autonomy to the Presidents of the provinces to mark the number and where the schools would be created, being able to extinguish them in one place and remove teachers to other places, depending on the size of the population.

The Law of October 15, 1827, determines the rules that certainly constituted a statutory reference for the link between the teacher and the State.

Art. 3º The presidents, in Council, will temporarily tax the salaries of Professors, regulating them from 200$000 to 500$000 per year, taking into account the circumstances of the population and the scarcity of places, and will do so to the General Assembly for approval.

[...]

Art. 7º Those who intend to be filled in the occupation will be publicly examined towards the Presidents, in Council; [...]

Art. 8º Only Brazilian citizens who are in the enjoyment of their civil and political rights will be admitted and examined, without any note on the regularity of their conduct.

Art. 9º The current Professors will not be provided in the occupation that are created again, without an approval exam, in the form of Art. 7º.

Art. 10 The Presidents, in Council, are authorized to grant an annual bonus that does not exceed one third of the salary, to those Professors who, for more than twelve years of uninterrupted exercise, have distinguished themselves by their prudence, care, large number and use of disciples.

Art. 13 The female Masters will earn the same salaries and bonus granted to masculine Masters.

Art. 14 The provisions of Professors and Masters will be for lifetimes; but the Presidents-in-Council, to whom the supervision of the schools belongs, may suspend them and only by sentences they will be dismissed, providing for an interim replacement. (BRAZIL, 1827)

Some of these rules, especially those referring to the payment of teachers, are the result of discussions held in the 1824 constitution, which made clear the precariousness with which teachers were paid and the need, consequently, to improve their salaries.

It is the first time that the possibility of women working officially in public education appears in the legislation, and at least with regard to legality, their salaries should be the same as those of teachers. However, this rule was vicious in origin, since the very definition of a salary band ranging from 200$000 to 500$000 per year could justify the salary differential. Another aspect to be observed is the use of the terms “teachers” and “masters”. In the “Regal Classes” this issue was treated with distinction: these were the masters of reading, writing and counting who worked in primary education, while those were the teachers of specific subjects related to secondary education. Because it is a specific legislation for primary education, it seems to be from there, even if in a confusing way, that the masters of reading, writing and counting or masters of first letters are officially called teachers.

The band of 200$000 to 500$000 per year as teachers' remuneration did not change much what was already being done in relation to secondary school teachers who, in general, already received higher salaries. However, for the institutes of the first letters, it represented, for the first time, a minimum standard of remuneration, a floor and a salary ceiling.

The admission to one of the occupation (or tenure in a mutual school), according to the Law of October 15, 1827, should be made through public examinations, having as criteria Brazilian nationality, regularity of civil and political rights, regularity in conduct and knowledge of the Lancaster method, and it is up to Teachers who did not have the necessary instruction in this teaching, to go to educate themselves “in the short term and at the expense of their salaries in schools in the capitals” (Article 4). Teachers who wanted to work in a second “occupation” had to apply for a new exam. This refers to the understanding that the duplicity of the teacher's workday was allowed and even necessary in the face of the scarcity of "qualified" labor. The aforementioned law also determined that the Presidents, in Council, could grant teachers a “performance bonus” of up to one third of their salary, taking into account: the “effective exercise” of at least twelve uninterrupted years, “their prudence, care, large number and use of disciples”16.

Based on the Law of October 15, 1827, it is possible to observe, among others, that the following norms were approved, which constituted a statute for the teaching profession, although it did not receive that name: i) Annual remuneration varying between 200$000 and 500$000 per year; ii) Nomination based on a public examination with the profile of being Brazilian, enjoying civil and political rights, not having a note on the regularity of their conduct; iii) Possibility of acting, through public examination, in more than one occupation; iv) Possibility of receiving “performance bonus”; v) Salary parity between male and female masters; vi) Lifetime provisions, except subjection to the supervision of the Presidents of the provinces, who, in Council, could determine the dismissal of the teacher.

However, these norms, which could correspond, at least to indications of the genesis of the statutory constitution in the primary teacher/State relationship, do not seem to guarantee a standardized valuation for the time, which it maintained not only among elementary school teachers, but between them and secondary teachers, a significant salary differential. While primary teachers perceived annual salaries based on the band of 200$000 to 500$000, with a tendency for a “floor” of 300$000 (VIEIRA, 2007), holders of secondary education chairs, less penalized, increased their salaries that “varied from 500,000 to 800$,000 per year” (ALMEIDA, 2000, p. 63).

Decree nº 4, of June 20th, 1834, for example, “approves the salaries set by the President in Council of the Province of Goyaz to the Professors of several subjects of first letters” according to the law of October 15th, 1827, however they maintain the individual method, in the following terms:

Art. 1. The salary of 200$000 is approved and ordered, set by the President of the Province of Goyaz in Council to the Teachers of the courses of first letters by the individual method of the villages of Imperial Porto, Cavalcanti, Carmo, Carolina and Palma: and so also that of 240 $000 to S. José de Tocantins and Flores, all in the same region as S. João das Duas Barras. (BRAZIL, 1834a)

The aforementioned decree was one of the last ones to come from the central power in this period and for this purpose, since Law nº 16, of August 12, 1834, known as the Additional Act of 1834 (BRASIL, 1834b), gives the provinces autonomy to legislate “on public instruction” (Art. 10, §2), as well as on the creation and suppression of most municipal and provincial jobs, including the competence to establish the respective salaries (Art. 10, §7). According to Monlevade (2000), with this additional act, the law of 15 october 1827 loses its mandatory validity and consequently the “band” of salaries is compromised, leaving from then on to each province, the competence to determine the remuneration of teachers of primary and secondary education. In many cases, the chairs were created, but they were not occupied due to the lack of teachers able to develop the function. For Almeida (2000), this was justified by the fact that it was a painful career, with low pay and without the deserved social prestige

Since 1772, masters and professors have been able to experience the first tests of a statutory relationship, which, however insufficient they may be to guarantee a decent remuneration, represented, at least on paper, an evolution in the regulation of the activity with the government that at that time appeared as a centralized way, with a tendency towards standardization of general rules. On the contrary, the Additional Act of 1834 represented the victory of the decentralizing tendencies, dominant at the time, and “suddenly suppressed all possibilities of establishing the organic unity of the system in formation that, at best [...] it would fragment into a plurality of regional systems” (AZEVEDO, 1963, p. 566). These regional “systems” began to legislate on primary and secondary education, regulating statutory relation with teachers.

Castanha and Bittar (2012), when discussing the role of teachers in the imperial period, present evidence that some provinces followed previously established norms and improved their legislation. For the authors, it is not possible to say that the decentralization of teaching has meant a total absence of unity, especially with regard to the work of teachers. The documents analyzed by the authors and exposed in great detail, point to an alignment of the analyzed provinces, in the main statutory aspects of the teaching profession. However, they do not ignore the precariousness that involved the teaching work at the time, described as follows by Almeida (2000, p. 101):

If there is a role that sometimes requires great morality, solid instruction, a special vocation and continuous devotion, it is certainly that of the public teacher, the educator of youth. But those who gather all these qualities, to a more or less high degree, need to have a secure existence for themselves and their family, and to be surrounded by every kind of public consideration that unites the more or less wealthy position of the man to his relative independence. It is contrary to equity for their efforts to confine them to misery, or at least to a deprivation, to a penury that disregards them in the eyes of all and their own.

Based on the study by Castanha and Bittar (2012), we list some of the main rules that guided the relation of teachers with provincial17 and court employers, which we now present.

The Admission passed through public examinations, which in some cases included practical classes directly in the school environment. About age for entry, the law of October 15, 1927 required that the candidate was in full enjoyment of his political rights, which he had when he was 25 years old. The provinces, lacking adepts to the teaching profession, started to demand only the common majority, that is, 18 or 21 years old. For the contest, the teacher must present the certificate of majority and morality attested by the parish priest, chief of police, and in some cases other authorities, inherent to the period of the last three years. another requirement it was common for the candidate to professed the Catholic faith, which lost strength from the 1870s onwards.

In cases where the candidate presented a qualification in normal schools or in higher education courses in the Empire, public examinations were waived. Otherwise, still in accordance with the model of the Law of October 15, 1827, the candidate was submitted to a committee that deliberated on failure, approval as an interim teacher or as an effective teacher. In the first two cases, the teacher could request, within a certain time, another assessment.

The “probationary stage” became part of the admission process. Everything indicates that it took place for the first time in the province of Rio de Janeiro from 1849 onwards. In general, a period of experience of 3 to 5 years was required.

To receive the title of lifetime, the rules were stricter. It was no longer enough to just pass the contest. The authorities complained that when the teacher was approved in the competition, the teacher stopped getting involved with his own learning, collaborating to worsen the precariousness of teaching. In this sense, from 1870 onwards, in order to receive the title of professor for life, after the probationary period, the professor would have to prove to be assiduous, dedicated, zealous in teaching, respected, unblemished conduct, to be “capable of passing 10% of his students each year” and not perform another remunerated function. Lifetime professors were granted the benefit of retirement18, even proportional, depending on the situation. Full retirement was granted after 25 years of work, but without bonuses. The teacher was encouraged to remain active through additional pay, which after 30 or 35 years of work, were incorporated into retirement.

Some regulations provided for bonuses for time of service, but conditioned to the quality of the teacher's work. Others rewarded teachers taking into account, for example, student attendance and approval. “There was also assistance for renting houses and schools or teaching houses”.

The documentary citation used by Castanha and Bittar (2012, p. 13) reveals some of the demands assigned to teachers from the second half of the 19th century:

Art. 1º The public teacher must: § 1º Search for all means to instill in the hearts of his disciples the feeling of duties towards God, towards the Country, parents and relatives, towards the neighbor and towards himself. The Professor's procedure and his examples are the most effective means of achieving this result. § 2 Keep silence at school. § 3rd Present yourself there decently dressed. § 4 To report to the respective Delegate any impediment that inhibits him from performing his duties. § 5º Organize annually with the same Delegate the budget of the expenses of the respective School for the following financial year. § 6 Send at the end of each quarter a nominal map of the students enrolled with a statement of attendance and achievement of each one, and at the end of the year a general map comprising the results of the exams, noting among the students those who are recommended for talent, application and morality. These maps will be organized according to printed models sent by the Inspector General. Art. 2nd The Professor can only use in his School the books and compendia, which are designated by the General Inspector. Art. 3º The Public Teacher cannot: § 1º Engage in strangers objects to teaching during lesson hours, nor employ students in their service. § 2º to be absent on school days of the Parishes, where the School is located, to any distant point, without permission from the respective Delegate, who can only grant it and for urgent reasons, up to three consecutive days. § 3 To exercise a commercial or industrial profession. § 4 To exercise any administrative job without the prior authorization of the General Inspector. (BRAZIL. Ordinance of October 20, 1855, p. 345).19

In addition, the teachers were responsible for: “accompanying students to Mass on Sundays and holy days, cleaning the school, taking care of furniture and utensils, among others” (CASTANHA and BITTAR, 2012, p. 13).

Castanha and Bittar (2012) point out that in most provinces the annual salary of teachers ranged between 200$000 and 400$000, but they point out that there are records of interim teachers who earned less than 200$000, which added to constant delays in receiving, the demands provinces, low prestige and high price, kept candidates away from teaching.

To better illustrate, we compare the salary of Court teachers with other professions. In 1858, the salary of a master builder was approximately 1:280$000, of a master carpenter 1:100$000, while the simple carpenter received 730$000. In 1865, the salary of a soldier in the military police was approximately 460$000, and in 1873 an urban guard received 720$000. (HOLLOWAY, 1997, p. 160, 163 and 218, apud CASTANHA and BITTAR, 2012, p. 17).

In this context, “the situation of the institutes became critical and the authority echoed their claims, publishing in their official reports that the school teacher lacked what was necessary to supply his situation of penury and deprivation” (ALMEIDA, 2000, p. 100).

The regulations, in general, determined that teachers who, through negligence or ill will, neglect their job, misinstruct students and other such faults, would have, among others, the possible penalties: admonition from the parish inspector, reprimand from the competent authorities, suspension of the exercise or expiration, fines ranging from 50$ to 60$000 and dismissal.

The contractual regulation and regulation of teachers during the Empire took different directions in each of the provinces, mainly due to the decentralizing character adopted by the Additional Act of 1834. This decentralization was not able to guarantee teachers neither statute nor dignified remuneration, especially if we thought as national scope possibilities. This scenario remained, and was even ratified in the so-called First Republic, from 1889 onwards. For Azevedo (1963, p. 607):

At no time in the 19th century, after Independence, were such important events for national life prepared and produced as in the last quarter of that century, when the first industrial boom took place, an immigration policy was established, abolished the regime of slavery, the organization of free labor began and, with the fall of the Empire, the experience of a new political regime was inaugurated.

However, with regard to statutory regulation of teaching work, especially for primary teachers, no records were observed that point to any kind of progress. It should be noted that at the end of the 19th century, the emergence of school groups created from the junction of isolated schools, provided their teachers with some kind of social prestige and better prospects of remuneration, which in many cases, was determined taking into account the location of the school unit, the number of students attended and the attendance and approval indicators. However, the provision of primary education, in general, continued to take place in isolated schools, marked both by the precariousness of working conditions and by the limitations of teacher training and remuneration.

Final considerations

The Pombaline reforms regulated in 1759 and 1772 demanded for the Portuguese Empire a new type of educational agent, that from then stopped being exclusively religious, to be also an activity developed by Masters of reading, writing and counting and by contracted and controlled by the state.

In the period from 1772 to 1834, the activities of this new “category” were nationally regulated based on official State documents, having as a guideline the Royal Charter of 1759, which had little repercussion in the Colony, the Law of November 6, 1772 and the Law of 1772 of October 15, 1827. If, on the one hand, this set of laws failed to guarantee the teaching staff, especially the Masters of First Letters, a consistent remuneration with the prestige that the activity should represent, on the other hand, it must be recognized that at least in the regulation, the aspects that characterize the first statutory norms of public teaching work in Brazil are evident. Among others, it is possible to observe the attempt to regulate the admission, work and remuneration of this category.

With the Additional Act of 1834, together with the decentralization of primary and secondary education, the regulation of teaching work was granted to the provinces. Even though it was possible to verify a certain alignment in some provincial regulations, decentralization made it difficult for further advances that were thought, not from the economic potential of each region, but from the particularities that made the teaching profession similar and fundamental. By being limited to the conditions of local collection, the remuneration of public teachers controlled by the State remained, with rare exceptions, in the degrading inertia of the beginnings in which it emerged from 1759. In addition, from 1834, the teachers started to live with the ever-increasing demands of the regulations: stricter admission processes, specific rules for obtaining the title for life, probationary period, bonus for performance, forecast of harsh penalties, etc. All this in contrast to the terrible or non-existent training conditions, precarious working conditions, low pay and the latent demand for more and more places in public education. This was the characteristic scenery of the transition from the Imperial to the Republican model and it is certainly maintained in many aspects, until the present day.

REFERENCES

Alvará de 18 de Maio de 1816. Estatuto para criação do Colégio Militar da Luz em Lisboa. Disponível em: http://www.sg.min-edu.pt/fotos/editor2/RDE/L/S19/1811_1820/1816_05_ 18alvara.pdf. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

Alvará Régio de 1759. Disponível em http://www.sg.min-edu.pt/fotos/editor2/RDE/L/ S18/1751_1760/1759_06_28_alvara.pdf. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

AZEVEDO, Fernando de. A cultura brasileira: introdução ao estudo da cultura no Brasil. 4ª ed. Brasília, Editora Universidade de Brasília, 1963. [ Links ]

BASTOS, M. H. C. e FARIAS FILHO, L. M. A escola elementar no século XIX: o método monitorial mútuo. Passo Fundo: Ediupf, 1999. Disponível em http://pt.scribd.com/doc/ 23609298/Metodo-monitorial-mutuo. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 4, de 20 de junho de 1834. Disponível em http://www.camara.gov.br/Internet/InfDoc/conteudo/colecoes/Legislacao/Legimp-19/Legimp-19_2.pdf. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. (1834a) [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei de 15 de outubro de 1827. Disponível em: http://www.camara.gov.br/Internet/InfDoc/conteudo/colecoes/Legislacao/Legimp-J_19.pdf. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 16, de 12 de agosto de 1834. Disponível em: http://www.camara.gov.br/Internet/InfDoc/conteudo/colecoes/Legislacao/Legimp-19/Legimp-19_3.pdf. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. (1834b) [ Links ]

CARDOSO, T.F.L. Imagens sobre a profissão docente no mundo luso-brasileiro. Revista de Ciências da Educação, n.11, jan./abr. 2010. Disponível em http://sisifo.fpce.ul.pt/pdfs/Revista%2011%20PT%20D6.pdf. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

Carta Régia de 10 de novembro de 1772. Disponível em http://www.sg.min-edu.pt/fotos/editor2/RDE/L/S18/1771_1780/1772_11_10alvara_1.pdf. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

CASTANHA, André Paulo; BITTAR, Marisa. Os professores e seu papel na sociedade imperial. Disponível em: http://www.histedbr.fae.unicamp.br/acer_histedbr/seminario/seminario8/_files/. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

ENGUITA, M. F. A ambigüidade da docência: entre o profissionalismo e a proletarização. Teoria e Educação, n. 4, “Dossiê: interpretando o trabalho docente”, p. 41-61, Porto Alegre, 1991. [ Links ]

FAVORETO, A. e GALTER, M. I. Ambiguidade de Fernando de Azevedo sobre a atuação da Cia de Jesus na organização da educação brasileira no período colonial. Educere et Educare, v. 1, nº 2, jul./dez. 2006, p. 73-82. [ Links ]

Lei de 6 de novembro de 1772. Disponível em http://www.sg.min-edu.pt/fotos/editor2/RDE/ L/S18/1771_1780/1772_11_06lei.pdf. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

LESAGE, Pierre. A pedagogia nas escolas mútuas do século XIX. In.: BASTOS, M. H. C. e FARIAS FILHO, L. M. A escola elementar no século XIX: o método monitorial mútuo. Passo Fundo: Ediupf, 1999. Disponível em http://pt.scribd.com/doc/23609298/Metodo-monitorial-mutuo. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

MONLEVADE, J.A.C. Educação pública no Brasil: contos e descontos. Ceilândia-DF: Idéa Editora, 1997. [ Links ]

MONLEVADE, J.A.C. Valorização Salarial dos Professores: O papel do Piso Salarial Profissional Nacional como Instrumento de Valorização dos Professores da Educação Básica Pública. 2000. 317 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Unicamp, Campinas-SP. [ Links ]

NÓVOA, Antônio. Profissão Professor. 2ª ed. Porto: Editora Porto, 1999. [ Links ]

O Método Pedagógico dos Jesuítas - O "Ratio Studiorum" - Organização e Plano de Estudos da Companhia de Jesus. In: http://www.histedbr.fae.unicamp.br/navegando/acervos.html. Acesso em: 08 de dezembro de 2012. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, M. A. S. História da educação brasileira: a organização escolar. 13ª ed. Campinas, SP: Autores Associados, 1993. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Jussara Maria Dutra. Piso Salarial Nacional dos Educadores: Dois Séculos de Atraso. Brasília: s/n, 2007. [ Links ]

XAVIER, M. E.; RIBEIRO, M. L. e NORONHA, O. M. História da Educação. A escola no Brasil. São Paulo: FTD, 1994. [ Links ]

2On Fernando de Azevedo's sometimes "ambiguous" position regarding Jesuit action in Brazil, see Favoreto and Galter (2006).

3Title cited by Azevedo (1963, p. 507) referring to the legitimacy with which it would be attributed to Father José de Anchieta. According to the author, with the same sense of "educator" and "protector and apostle of the Indians".

4Considering, for example, Azevedo (1963) description of the Jesuit activity in the civilizing process of Colonial Brazil, it could be said that this was an activity developed by public teachers. The difference is that the public teacher after Pombal will establish a contractual relationship with the Portuguese State, implying, among others, the obligation of his remuneration. Nóvoa (1999) refers to this educational agent as a public teacher "controlled by the State".

5Regarding the object analyzed in this study, the Proclamation of the Republic does not represent an event that immediately changes the conditions existing at the time. The clipping has the objective of situating the discussion having as limit the end of the Imperial period.

6It should be noted, however, that in that context, the installation of the Portuguese elite in the colony required the opening or improvement of various services, including educational ones. This does not mean that all royal teachers were graced with royal benevolence, nor that the hirings were sufficient to attend to all subjects indiscriminately.

7The terms "masters of reading, writing and counting", Mestres regios" and later "institutors and "primary teachers" are used by Azevedo (1963), almeidaa (2000) and Monlevade (2000) as synonyms to indicate who worked in primary education, which at the time was reduced to literacy and teaching the four fundamental operations of mathematics.

8According to Monlevade (1997), p.24), the "Aulas Régias" were in force in Brazil from 1772 to 1822.

10"This means gaining a title of social and political distinction, which brought advantages in social ascension, in addition to guaranteeing certain privileges, such as exemption from certain taxes, the possibility of occupying positionsdestined for the nobility, the exclusion of infamous sentences, or even the privilege of not going to prison. In the list of honors granted to subjects, the literate category, consisting of doctors, graduates and graduates, held the lowest degree of nobility." (CARDOSO, 2010, p. 60). For the author " The decree of July 14, 1775 reinforced this distinction, by establishing that royal professors were entitled to the Privilege of Homage, in terms of the nobility of their employment" (CARDOSO, 2010 p. 60).

14Unity was not maintained by the royal treasury alone. Part of the budget came from the "contribution" of the military, which was justified by the exclusivity of their children in accessing the institution.

16At that time, there was already a policy of intensification of teaching work based on meritocratic artifices.

17Not all the rules presented apllied in all provinces. As each one having the autonomy to legislate on the subject, there were different, but not distant, rules for hiring and controlling teaching work.

18As previously mentioned, the granting of retirement to teachers was alreadry part of the Statute of the Militar school da Luz in 1816, approved by D. João VI. It was only in the last decades of the imperial period that it began to be implemented in Brazil.

19In addition, according to artigo 6º “The school must Always be clean and tidy, making the teacher sweep the house at least once a day, wash it twice a month, and keep the windows opened as much as possible”. It is importante to highlight that the provisions contained in the Internal Rules of Court schools, of November 6, 1883, remain pratically the same. Cf. BRASIL.Decision n. 77, 1883, p. 77-8. (Authors’Note)

Received: October 13, 2021; Accepted: February 11, 2022

text in

text in