Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 13-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-135

Papers

English language in the Classes Integrais in the 1960s: a study at Colégio Estadual do Paraná1

1Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (Brazil). sofia.bocca@hotmail.com

2Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (Brazil). rosa_lydia@uol.com.br

This article aims to understand the purposes of teaching English at Colégio Estadual do Paraná, in the 1960s, when an experiment was in progress aiming at the renewal of secondary education, whose classes were called Classes Integrais. With theoretical support from Cultural History (CHARTIER, 2002) and the concept of School Culture (JULIÁ, 2001), the study uses as a document the Reports of the Classes Integrais from 1960 to 1967. The results indicate that these Classes brought novelties in English Language teaching such as the adoption of active methodologies, diverse teaching resources, differentiated assessment, vocabularies, and grammatical structures were dealt with in specific situations familiar to students, the practice of the four skills (reading, writing, speaking, listening). However, the general objectives of the teaching of this subject were, in addition to mastering the basic structures of the language, interpreting texts in order to prepare for higher education or professional training.

Keywords: English teaching; School subject; Classes Integrais

Este artigo tem por objetivo compreender as finalidades do ensino de língua inglesa no Colégio Estadual do Paraná, na década de 1960, quando estava em andamento um experimento que visava a renovação do ensino secundário, cujas turmas foram denominadas Classes Integrais. Com apoio teórico da História Cultural (CHARTIER, 2002) e do conceito de Cultura Escolar (JULIÁ, 2001), o estudo toma como fonte documental os Relatórios das Classes Integrais de 1960 a 1967. Os resultados apontam que estas Classes trouxeram novidades no ensino da Língua Inglesa, como: adoção de metodologias ativas, emprego de recursos didáticos diversificados, avaliação diferenciada, vocabulários e estruturas gramaticais eram tratadas em situações específicas e familiares aos alunos, prática das quatro habilidades (ler, escrever, falar, ouvir). No entanto, os objetivos gerais do ensino desta disciplina eram, além do domínio das estruturas básicas da língua, interpretar textos com a finalidade de se preparar para o curso superior ou profissionalizante.

Palavras-chave: Ensino de inglês; Disciplina escolar; Classes Integrais

Este artículo tiene como objetivo comprender los propósitos de la enseñanza del inglés en el Colégio Estadual do Paraná, en la década de 1960, cuando se desarrollaba un experimento orientado a la renovación de la educación secundaria, cuyas clases se denominaron Clases Integrales. Con apoyo teórico de Historia Cultural (CHARTIER, 2002) y de Cultura Escolar (JULIÁ, 2001), el estudio utiliza como documento los Informes de Clases Integrales de 1960 a 1967. Los resultados muestran que estas clases trajeron novedades en la enseñanza del idioma inglés: adopción de metodologías activas, el uso de diversos recursos didácticos, evaluación diferenciada, vocabularios y estructuras gramaticales en situaciones específicas familiares a los estudiantes, práctica de las cuatro habilidades (lectura, escritura, expresión oral, comprensión auditiva). Los objetivos generales de la docencia de esta asignatura eran, además de dominar las estructuras básicas del idioma, interpretar textos para prepararse para la educación superior o la formación profesional.

Palabras clave: Enseñanza del inglés; Disciplina escolar; Clases Integrales

Introduction

The teaching of English in Brazil has, since the arrival of the Portuguese Court, presented characteristics that change over time, whether in terms of purpose, or didactics, methods, contents, etc. To investigate the trajectory of a school subject, it is necessary to explore social, ideological, political, cultural, and economic elements in order to compose the reading of its object. With this in mind, this article aims to understand the purposes of English classes at Colégio Estadual do Paraná, in the 1960s, when there was an experiment aiming at renewing secondary education, whose classes were called Classes Integrais.

For that, we use Cultural History, which aims to identify how, in different places and times, a certain reality was thought, built, and interpreted, as argued by Chartier (2002). In addition, taking the educational sphere, Juliá (2001, p. 22) states that “[...] the school is not only a place for learning knowledge, but also a place for inculcating behavior and habitus that requires a science of government transcending and directing, according to its own purpose”.

We also rely on the concept of school culture as summarized by Juliá (2001, p. 9): “a set of norms that define knowledge to be taught and behaviors to be inculcated, and a set of practices that allow the transmission of this knowledge and the incorporation of these behaviors”. The author proposes three axes to understand school culture as a historical object: the first being focused on the norms and purposes of the school; the second aimed at the professionalization of the educator; and the third directed to the contents taught and ways of teaching. We will focus, mainly, on the third axis, because contents, practices, and school subjects are inseparable from educational purposes.

Following these theoretical precepts, we begin by contextualizing the Classes Integrais; then, we discuss the research procedures and sources; next, we present the teaching of English at that school; finally, the final considerations.

Contextualizing the Classes Integrais

Colégio Estadual do Paraná (CEP), a traditional educational institution, now located in the center of the capital, has been making its history for over 170 years. It is also a space for cultural, sports, and social activities for people from Paraná, promoting science fairs, with a planetarium, musical band, museum, and a center for Modern Foreign Languages.

In the 1960s, this school was the stage of an experience and what was called the Experimental Classes in several regions of the country, in CEP was called Classes Integrais. It was a similar pedagogical experience, but with different nomenclatures.

Under the New School ideals2, and following the same precepts of the Classes Nouvelles3- a proposal for an alternative and innovative pedagogical model for secondary education in France, which aimed at training not only for work but for life -, in the late 1950s and mid-1960s, the pedagogical renovation of secondary education was proposed, called Classes Experimentais4. These aimed to contribute to the transformation of secondary education, mainly in relation to the democratization of access to this level of education, which was exclusive to the elites until then.

The idea that educational laws and practices were outdated, that such a rigid, uniform and tight education no longer fit in that developing society with diverse demands, circulated among defenders of public education, as well as among students, Therefore, these Classes intended to “[...] develop a curriculum adapted to the conditions of the students and the demands of a democratic society in a growing phase of industrialization, urbanization and modified by new scientific discoveries [...]” (CHAVES JUNIOR, 2016, p. 520). School education was believed to be responsible for economic and social development, forming individuals capable of integrating into the new society (urban, modern, industrial, and democratic) that was developing. To meet the new audience and the new purpose of teaching, a change in the program, in the curriculum, in the method was necessary.

The Classes Experimentais, as described by Chaves Junior (2017) and Dallabrida (2018), would be developed in institutions with pedagogical conditions to allow such an experience; they should have a reduced number of teachers who should be accredited, and who should hold frequent meetings; there was the need for the consent of the parents or guardians of the enrolled students, and they also had to participate in periodic meetings; the curriculum should seek solid human formation, attending to individual aptitudes and aiming at a greater articulation of the teaching of the various disciplines through the use of active methods; they should have a reduced number of students in each class (maximum 30); also, the increased time spent in school would be filled with extracurricular activities called Clubs.

Dallabrida (2018), on the experimental secondary classes between 1959 and 1962, reports that “[...] this renewing pedagogical experience was carried out, during this period, in 46 schools, located in eight states, most of which belonged to the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro [...]” (p. 104), among these states is Paraná. Here, the institution that had the authorization to implement the Experimental Classes was CEP.

The activities were full-time: from 7:20 am to 11:50 am (initially, classes started at 8:00 am, but there was a need for this increase) the subjects offered were Portuguese, Mathematics, Geography, History, Science, French, English or Latin, Drawing and Physical Education; in the afternoon, from 1:50 pm to 5:30 pm, artistic-cultural activities were conducted, with the disciplines of Music, Applied Arts, and Religion, as well as reinforcement classes for the disciplines studied in the morning. In addition to the weekly classes, students had classes on Saturdays, from 7:20 am to 9:50 am (CHAVES JUNIOR, 2016).

The activities “extended to social aspects, of professional orientation, with interviews, of sexual orientation, and physical education, clubs, trips, tours and visits” (STRAUBE, 1993, p.114). The annual reports (PARANÁ, CEP, 1960-1967) indicate that the clubs were extracurricular activities offered regularly, varying according to the interest of students and availability of teachers. They included chess, checkers, drawing, painting, ceramics, photography, theater, dance, literature, English, etc.

There was a project called “Articulation of disciplines”, which indicated the work of several disciplines focusing on the same theme. Chaves Junior (2017) shows, through teachers’ reports, that it was an attempt to do interdisciplinary work, which sometimes resulted in great connections between disciplines, other times, there was not so much interaction between them.

The results of the experience pointed to a reduction in the dropout and failure rate, success and benefits were also obtained in the sense of renewal, even though there were points of conservatism, such as the students’ selection criteria, or the requirement of compulsory common disciplines. However, for various structural, administrative, and financial reasons - mainly in relation to the payment of teachers, who received for full-time work - in 1967, the Classes Integrais ceased to exist and the students who were still attending them were incorporated into the Common Classes.

Thus, in this experience, we observed some innovative cultural aspects that aimed to break with traditional cultural aspects.

Sources and Methodological Procedures

The documents taken for analysis in this study were the “Reports of the Classes Integrais” written by the teachers in the period from 1960 to 1967, which were divided by year, being, therefore, eight books, one for each year. The reports are hardcover books with thin sheets, typewritten, with an average of 220 pages each. They do not contain typed pagination, but handwritten enumerations - not always in numerical sequence.

The following information is found in the reports: General enrollment chart; Nominal list of students; List of teachers and other employees; Copy of the final results minutes; Performance statistics for the previous academic year; School timetable; General observations on school activities for the school year; Modifications made to the Classes Integrais plan; Class organization (two classes of each grade - 25 students each); Teachers’ meetings; Articulation of disciplines; Demonstrations performed by students; Report of the Educational Guidance service; Environmental Study (visits made during the year); Projected Films Report; Campaigns carried out; Extra Class Activities (Clubs of Science, Arts, Gouache, Photography, Chess, Philately, Folk Dances, Carpentry, Model Aircraft, Crosswords, Literature, Dentifrice, Sports, etc.); Reports for each discipline; School performance (bimonthly of all subjects, of all classes).

The record of each subject is signed by the teacher in charge and, at the end of the report, there is the signature of the coordinator of the Classes Integrais of CEP, Ruth Compiani. This type of document, because it is written by the teacher him/herself, has significance and relevance, as it allows us to approach the reality of the classes, that is, they rely on the veracity of the information contained therein, thus enabling access to the practice in the context of the classroom. Below is a description of what is included in each of the Reports.

1960’s Report

The year 1960 was the first year of the experiment and only 1st grade classes A and B were offered. In this report, there is an item called “Description of the Didactic Method” in which it is stated that, in addition to adopting “Learning by doing”, teaching essentially consisted of guiding student activities; the student researched, compared, analyzed, formulated syntheses. In short, it was oriented towards rediscovering the content, working on it, and organizing it into a meaningful whole. The adoption of the “Teaching Unit Method” (CEP, 1960’s Report) is also referenced. In addition, it brings indications of the use of study sheets, and the intention of raising the autonomy and responsibility of the students.

This report does not provide information about the teaching of English because, in that year, only French was studied as a foreign language.

1961’s Report

In 1961, 4 classes were organized - two of the 1st grade and two of the 2nd grade. With regard to the search for the pedagogical experience, of 219 approved in the entrance exam, 103 applied and 50 were selected.

In the project “Articulation of Disciplines”, it is stated that, when studying the Americas, the 2nd grade worked on the flag of the United States of America, pictures of the White House with its rooms, erosion in the USA, tea in England, in addition to a visit to the American Consulate. At the closing party of the year, the students sang “Silent Night” (CEP, Report of 1961).

Pan-Americanism is also mentioned in the report, although there is no description of the work carried out on the topic.

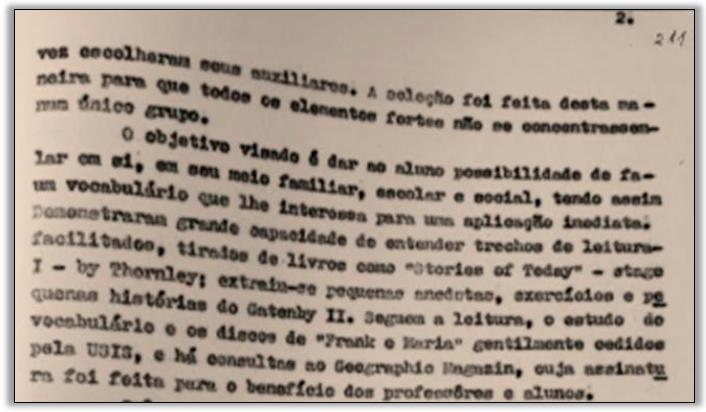

Source: CEP, Reports of the Classes Integrais of 1961 - CMCEP, p. 13.

Figure 1 Articulations of the 2nd grade (Units III, IV, and V) - 1961

There is no mention of the use of textbooks. However, the book Frank and Maria - Book I, provided by the United States of America Cultural Relations and Dissemination Service5 (CEP, 1961’s Report), was adopted as supplementary reading.

1962’s Report

In 1962, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grade classes were organized, with English being offered from the 2nd grade onwards, with a workload of 4 lessons per week.

Regarding the interest in those Classes that year, 243 students were approved, of these 86 applied, of which 50 were drawn. Compared to data from the previous year, there was a greater search for the Classes.

The report contained an extra topic bringing the issue of “Classes Integrais (Experimentais) of Colégio Estadual do Paraná in the face of Opinion nº 13 and the Law of Directives and Bases”. It is reported that Secondary Education establishments with ongoing experiments, and wishing to continue with them, were asked to provide the following: 1 - Complete report of the results; 2 - Reasons why they cannot adapt to the new legislation; 3 - New proposal to proceed with the experience for the entire course. In addition to this, a report on the “Improvement internships carried out by teachers of the integral classes at the Oswaldo Aranha Vocational Gymnasium, in São Paulo”.

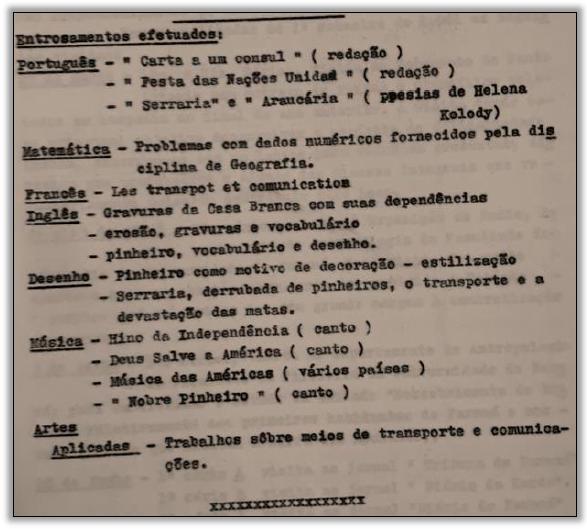

The Articulations of Subjects carried out involving the subjects of History, Geography and English were: in the 2nd grade - location, limits and areas of Paraná and Brazil; relief of Paraná; Paraná’s hydrography; vegetation. At parents’ meetings, students participated by performing songs in English and French, in addition to reading poetry in a choir. In the 3rd grade - they visited the School’s Library and the Public Library. In the English classes, the vocabulary about means of transport and communication was explored.

Regarding the use of teaching materials, it is reported that “[...] easy reading excerpts, taken from books such as “Stories of Today” - stage I - by Thornley; little anecdotes, exercises, and little stories were extracted from Gatenby II” (CEP, 1962’s Report, p. 211). In addition to these, as in the previous year, reading and listening skills were worked on with Frank and Maria. In addition to the information about the teaching materials adopted to assist in the teaching and learning process, it also brings its objectives: to enable the student to acquire enough vocabulary necessary to talk about specific subjects and read the selected texts.

1963’s Report

Given the greater demand for studying English, this year, the language was offered from the 1st grade onwards, and Latin and French were suppressed (in the new 1st and 2nd grade classes). For this reason, this report, in comparison with the previous ones, provides more information about the English classes.

With regard to the use of textbooks, it is mentioned that, for the 1st grade, “[...] during this first stage, eminently oral, a textbook has not yet been adopted [...]”, which suggests that a textbook would later be adopted.

Subjects related to the Articulation of Disciplines were taught in the form of reading and questionnaires. The grammatical part was given indirectly. At the meeting of parents and 2nd grade students, there was a presentation of two children’s songs: Brother John and Row your boat. In grade 3, English related to History and Geography in the following topics: prehistory (reading excerpt), Egypt (reading and conversation), Assyrians and Chaldeans (conversation), Hebrews, and monotheism (conversation). When the subject was Asia, a questionnaire about its geographical situation was applied: limits, area and location, relief, hydrography, climate and vegetation, population, language, and religion.

Also, the Greek world and the European continent: Greek mythology, issues about Greece, Rome, Great Britain, limits and characteristics of Europe. Also, these were activities of the Articulation: the animals of the zoo after visiting Passeio Público, descriptions of hypothetical picnics and walks to the beach. For the theme “In the City”, a purchase at a clothing store was simulated so that students could practice knowledge about clothing descriptions, and also a trip to the cinema, involving the knowledge related. For the next topics, “Our Homeland” and “Our State”, works were carried out on cardboard. Also, for the end of the year, they made plans for the holidays and Christmas cards.

In addition, as in the previous year, the 3rd graders had a weekly audition of the Frank and Maria albums, with comments on vocabulary, grammar, and history, derived from the lessons that accompany the albums. This information, compared with that of the 1961 report, leads us to believe that they were audiobooks that worked both reading and listening skills. In addition to this material, short stories and anecdotes were taken from the book by Gatenby II and given as supplementary reading. It is stated in the report that greater emphasis was given to oral work, but that the written work was also intensified - the tests were only oral, but they carried out several written exercises in the notebook.

For the 4th grade, in the Articulation project, teamwork was carried out on medieval Europe and the crusades, through the translation of the National Geographic Magazine. A study was carried out on the origins of the Parliament and the students answered a questionnaire about the Hundred Years’ War. Also, reading and discussion about English and American Civilization and representative writers such as Shakespeare. In addition, with greater emphasis on the written part than on orality, the themes “Collecting stamps”, “Climbing Mount Everest”, “English Country Life”, “An English Village”, “A visit to London and New York”, “Life in English-speaking Countries” with individual works, in pairs or teams. Also for this grade, it is revealed that some exercises from the book Beginning lessons in English (CEP, 1963’s Report) were introduced.

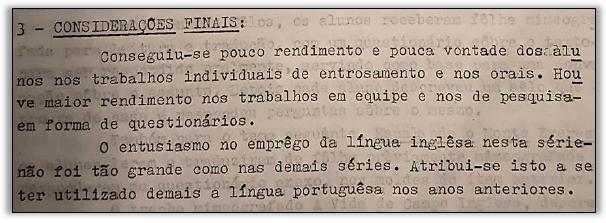

This was an important year for the pedagogical experiment, as the first groups completed the full course - from 1st to 4th grade. Some results for this discipline are exposed, although they are not very optimistic.

It is reported that the enthusiasm for using the English language in the 4th grade was not as great as in the other grades, which could be due to the excessive use of the Portuguese language in previous years.

1964’s Report

As extra activities, they read short stories taken from the book by Gatenby II-Direct Method such as A sad story, The four musicians, A cross-word puzzle, A story about Edison. In addition to these, there was an oral reading of the poetry The squaw dance by Lew Sarett and work with the song Never on Sundays. As usual, at the end of the year, they made Christmas cards.

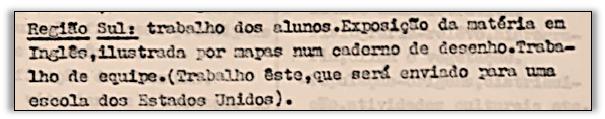

As for the Articulation of English with the disciplines of History and Geography, in the 1st grade, there was a dialogue about Curitiba and vocabulary about the herb “mate”. In the 4th grade, works with research, reading, and conversation about the British Empire and the United States of America in various aspects (rural and urban environments, universities, literature) were carried out. Also for this grade, when studying the southern region of Brazil, teamwork was proposed and, according to the record, it would be sent to a school in the United States, as can be seen in the following excerpt:

Source: CEP, Reports of the Classes Integrais of 1964 - CMCEP, p. 20.

Figure 4 Articulation of English and Geography in 1964

The demonstrations performed by the students, involving English Language and Music, were a chant for 1st graders, and a musical presentation in English for 2nd graders (CEP, Report, 1964).

1965’s Report

That year, of the 111 who applied, 49 new students were drawn for the 1st grade - one of the vacancies was occupied by a repeating student.

In the Articulation of disciplines, it is mentioned that, for the 1st grade, the following was explored: dialogues about Curitiba; cardinal points and their use in orienteering in the United States of America; vocabulary about temperature; the use of tea in England.

In the 2nd and 3rd grades, reading was taught through phonetic symbols, when necessary, and great attention was given to “Pattern Practices”, that is, to word substitutions in new structures. Also, in classes, students memorized and acted out dialogues, in addition to copying them in the notebook afterward. To learn the parts of the body, in the 2nd grade, “Hoocki-Poocki” was sung. They also sang the song “God save America”, in addition to watching the movies “Modern New York” and “World’s Fair”. In the 3rd grade, a study was made of famous sentences from the magazine “Life” v. 34, no. 9, no. 4 and no. 5 (CEP, 1965’s Report). The 4th grade class did not perform a relevant activity of Articulation. In this series, the written exercise was focused - in order to prepare the students for High School. Even so, oral presentations were made, for example, students giving explanations in English to a slide show on the English Parliament.

1966’s Report

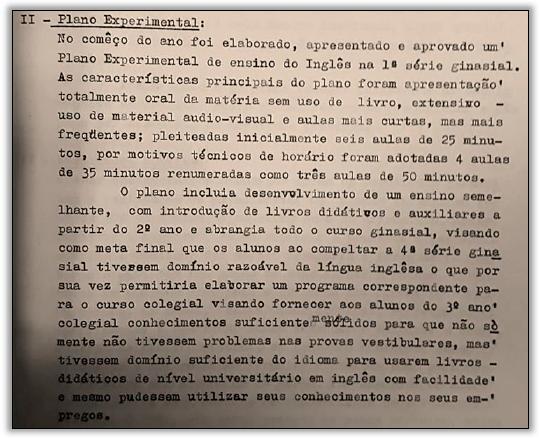

That year, 47 places were filled for the 1st grade - there were 3 repeating students. This report announces the decision to gradually extinguish the Classes Integrais, integrating it into the establishment’s common system. Among the reasons given are the recommendation of the State Board of Education to reduce the study schedule in just one period, ceasing to be full-time. Another factor was teacher remuneration - late payments discouraged teachers, affecting their performance in class. The use of physical spaces in classrooms by larger numbers of students was also an issue raised. As a result, from 1967 onwards, no new classes would be opened. The existing classes would continue their classes only in the morning, with cuts in the workload. Regarding the English classes, in the 1st grade, a change in the schedule was proposed, with shorter classes being offered more frequently (4 classes of 35 minutes each). It was foreseen that these would be strictly oral, with the aid of audiovisual material, without the use of books, as seen in the image below:

Source: CEP, Reports of the Classes Integrais of 1966 - CMCEP, p. 77.

Figure 5 Plans for the English classes in 1966

However, faults that prevented such execution are accused, such as the lack of quality of the material provided by the C.C.A.A. and null cooperation from Cultura Inglesa, which should also provide audiovisual material.

This report contains a record of the “Sing Song Club”, in which the subjects of English and Music were worked together. It is reported that there was an improvement in the students’ pronunciation, as the lyrics were initially worked on and then put into practice in the singing. Additionally, games and disc auditions were made.

The teaching of English in the annual registers of the Classes Integrais

Law No. 4024 of 1961 in Chapter II on secondary education contains:

Art. 45. In the junior high cycle, nine subjects will be taught.

Single paragraph. In addition to educational practices, no less than 5 or more than 7 subjects can be taught in each grade, of which one or two must be optional and freely chosen by the institution for each course.

In this way, the teaching of a foreign language lost its obligation, and its inclusion or exclusion was the responsibility of each state. As a result, some schools maintained French and English, as was the case with CEP, while others did not offer the English language.

In 1962, in the 1st cycle of the Secondary Course and in the Normal Course, divided into 4 series, French (1st and 2nd series) and English (3rd and 4th series) classes were offered, with different curricula. For the 2nd cycle of secondary school, i.e. high school, English classes were offered in the last three grades.

In the indications for the 4th grade of junior high school, the following addendum appears in the High School Programs: “This subject, then, assimilated in this way, will serve as a foundation for the high school course, both in the classical orientation (2nd and 3rd grades) and in the scientific orientation, where, in the three series, the student will have ENGLISH LANGUAGE PRACTICE” (PARANÁ, 1962, p. 51). Thus, we infer that in the early grades, “theory” was learned and, in later grades, knowledge was put into “practice”.

According to data from the reports, the initial objective of studying English was to make the language known to students so that they could consciously choose between English and French in the 2nd semester. As a result, most students opted for English, which created a serious problem in the second semester, as the classes were too large, making it difficult to teach and learn the content. The solution to the problem was to subdivide the classes into smaller groups. Chaves Junior (2016, p. 532) also comments on language teaching in the Classes Integrais,

work with “French, in a recreational way” was planned throughout the 1st grade of the course. In the first semester of the 2nd grade, students would attend English and French classes so that in the second semester they could choose one of them or, when demonstrating “taste and aptitude”, continue with both.

In order to better visualize the issue of languages offered, a table follows in which it is possible to observe the gradual opening of new classes, in addition to the offers and options for foreign languages.

Table 1 List of foreign languages offered by grades in the Classes Integrais

| YEAR | GRADES | LANGUAGES OFFERED | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 1st grade | ENGLISH | FRENCH | LATIN |

| No | Yes | No | ||

| 1961 | 1st grade 2nd grade |

No Yes |

Yes Yes |

No Yes |

| 1962 | 1st grade 2nd grade 3rd grade |

No Yes Yes |

Yes Yes Yes |

No Yes Yes |

| 1963 | 1st grade 2nd grade 3rd grade 4th grade |

Yes Yes Yes Yes |

No No Yes Yes |

No No No Yes |

| 1964 | 1st grade 2nd grade 3rd grade 4th grade |

Yes Yes Yes Yes |

No No No Yes |

No No No No |

| 1965 | 1st grade 2nd grade 3rd grade 4th grade |

Yes Yes Yes Yes |

No No No No |

No No No No |

| 1966 | 1st grade 2nd grade 3rd grade 4th grade |

Yes Yes Yes Yes |

No No No No |

No No No No |

| 1967 | 2nd grade 3rd grade 4th grade |

Yes Yes Yes |

No No No |

No No No |

Source: The authors (based on information taken from the reports analysed).

In the table, it can be seen that English became predominant from 1962 onwards. In that year, 2nd grade students, in the 2nd semester, had to choose between one language or another. Thus, as new classes were created, English classes were prioritized, and French started losing its position. The reason was not only the predilection, but also the fact that, due to the new LDB of 1961, there was a change in the plan of the Classes Integrais in relation to foreign languages. This issue was exposed in an item in the 1962’s report, as follows.

The planning of the work for the year 1962, for the 3rd grades, was carried out in accordance with the Plan for the Organization of Classes Integrais. Only one aspect was modified in face of the new Law of Directives and Bases of National Education - the issue of the living foreign languages study.

The Classes Integrais Plan allowed the student to choose one of them (French or English) after the mandatory period of familiarization with their study; it also admitted the possibility for the student to continue studying both, because perhaps they would need them when entering the 2nd cycle.

The choice was made after the 1st semester of the 2nd grade and the result was the following: 33 students opted for English; 7 students opted for French; 6 students continued with both, foreseeing the possibility of needing them in the scientific course, a reason that is annulled in the face of the new law.

Considering the new situation and also trying to serve the group of students who, studying both languages, requested a new opportunity to define themselves by one of them, since they were not satisfied and thought they were disadvantaged in relation to the other group, it was decided that they would be given the chance lost - and the result was the following: 39 students opted for English; 7 students for French (CEP, 1962’s Report).

According to the 1963’s report, due to the low interest in French, and also to the fact that the dedication to a single language during the 4 years of junior high school could bring greater performance, the language was suppressed on an experimental basis, and English was introduced since 1st grade. In the same way, Latin did not have a demand, possibly due to the lack of incentive, expressed by the LDB of 1961, being definitively suppressed. So, students who were already participating in classes of these two languages were able to complete them by the end of the year, but they were no longer offered the following year for new students, and were completely extinct in 1964.

The school year was divided bimonthly, and the option for English or French (while it was still offered) was done every six months. As for the frequency of language classes, two to four classes per week were offered, depending on the grade and the option for French (before being excluded).

As an extracurricular English language activity, the “Sing Song Club” was offered, where songs were sung in English. This activity allowed the students to interact and provided the opportunity for oral practice of the language.

As mentioned before, in the project “Articulation of Disciplines” the content of English was generally concentrated on lexical acquisition and was related, especially, to the disciplines of History and Geography.

In the reports, it appears that the verification of learning was done through objective tests, oral and written exercises, and conversation. After each test, the students themselves corrected their work in the notebooks, which contained illustrative vocabulary, complementary exercises, songs, and poetry.

As for the rate of use of English classes, these records indicate that the objectives were achieved, since the students demonstrated a reasonable command of the language. The 1961’s report presents results of a comparison between the Integral and Common Classes: the students of the 2nd grade English classes of the Classes Integrais presented more knowledge even when compared to the students of the 3rd and 4th grades of the Common Classes. However, we found no evidence of this information, such as activity sheets, or in-depth descriptions of the assessments carried out.

There was a great variety of teaching resources in the classes, such as games, oral activities, written exercises, musical presentations, films, magazines, audiobooks, and activities such as visits, simulations, etc. The classes focused on orality, that is, conversation practiced in teams. During the 4 grades, vocabularies and grammatical structures were worked on in specific situations that were familiar to the students, for example, describing the family, school, students’ habits and activities, cities, food, sports, the human body, animals, shopping situations or going to the movies, comparison between the United States of America and Brazil in various aspects, making Christmas cards, etc. Through a lot of repetition and revision, it was possible to learn vocabulary and phrases from the students’ daily lives. Among the objectives pursued, we highlight: making another nation known, with its customs and traditions, accentuating what there is in common between Brazil and abroad, teaching to respect cultures and traditions of other peoples.

Regarding the use of textbooks, it appears, although without details, that some were used to provide texts, stories, poems, and grammatical exercises that would be worked on with the students. Possibly, this is justified because it is a proposal that adopts the active method and is opposed to teaching with textbooks only.

Educators aimed to renew school culture, reform pedagogical practices that were plastered in traditional conservative concepts, through this experimental proposal, which lasted for almost a decade.

Resuming the concept of school culture proposed by Juliá (2001), the Classes Integrais can be understood both from the point of view of their conception, as well as organization and functioning, as an experiment that proposed a new set of norms, defining other knowledge and behaviors, generating differentiated practices and renewed purposes, through reformed contents and ways of teaching. A new culture was being created within that school, which already had its culture established.

It is worth pointing out here that the teaching of English, since its implementation in Brazilian schools in the 19th century, as reported by Oliveira (1999), took the mother tongue as a reference for its learning, in addition to being taught through selected excerpts from literature books in the English language. At the beginning of the 20th century, in the Vargas era, with the reform of Francisco Campos in 1931, there was a change in the teaching structure aimed at adapting it to the new reality of the country, nationalization, and modernization. This reform specified the objectives, content, and teaching methodology of subjects; in the case of the English language, it reinforced its cultural and literary character, adhering to the Direct Method, according to which the foreign language should be taught in the foreign language itself, also known as Natural, since it proposed learning in an oral and natural way, without the use of translation. The transmission of meaning would take place through gesticulations, mimes, and images.

Redondo (2013) details that, in this period, vocabulary and everyday phrases were taught with an emphasis on the correct pronunciation of words, oral and listening comprehension mattered. Grammar was taught inductively. From the teacher, fluency in the target language was expected in order to be able to conduct classes only in that language. This was one of the reasons for the lack of success of such an approach in public schools.

Oliveira (1999) mentions that, in 1951, there were changes in the Brazilian curriculum due to the recognition of the leaders about its inadequacy for the moment, given its bookish tradition, which required a simplification of the programs, including the suppression of the study of the history of the English literature.

From 1958 to 1970, the Audiolingual and Audiovisual Approach prevailed, which, according to Casimiro (2005), can be considered a re-edition of the Direct Approach, which emphasized oral language - the student should move on to spelling after assimilating orality. It adopted the process of stimulus and response, being important the reinforcement from the teacher to the right answers. The method was based on the association of figures and sentences, encouraging the student to repeat sentences with the syntactic and lexical aspects of the class.

For the Paraná Secretariat of Education, “Audio-visual method is a very comfortable term that can designate a method entirely based on the use of audio-visual material (still or animated images, recordings on disks or magnetic tapes)” (PARANÁ, SEEC, 1972, p. 30), which, at first, seems to oppose the traditional method, precisely because it uses audio and images. However, in it, the teacher makes use of a didactic manual to transmit knowledge and, according to the same document, “[...] it may happen that audio-visual material is used just to appear up-to-date, while still practicing a traditional design method, inspired by old-fashioned principles” (PARANÁ, SEEC, 1972, p. 31).

Thus, taking into account the context, presented above, of the teaching of the English language at the time, Classes Integrais brought novelty in the most diverse aspects: new methodologies were adopted, diversified material was used, the way in which the student was evaluated was differentiated, the aim was to encourage student’s autonomy and offer comprehensive training, even the way of enrolling these Classes was unique. However, with the end of the experience, the students had to be inserted in the Common Classes of the CEP in their already consolidated cultures.

Therefore, studying school culture means recovering the manifestations established on the inside of institutions. In this case, we were able to observe the norms, theories, practices, disciplinary organizations that the CEP implemented in the English language in the 1960s.

Weaving considerations

The set of norms and practices that define the knowledge that society wants to be taught, and the values and behaviors to be inculcated, are reflected in school subjects.

Regarding the English Language subject, we can say that its inclusion in the CEP curriculum in the 1960s was justified by its instrumental and cultural functions, as it aimed to contribute to the improvement of linguistic activities, by expanding vocabulary and forms of communication, and the development of social activities, by providing contact with other civilizations and cultures.

With this, we emphasize that its main objective was training for work since the nation’s project was the search for progress and industrialization. At that moment, language was not being seen as an intellectual activity, for the formation of the linguistic scientific-philosophical spirit, but had become a mechanism for professional training. The general objectives of teaching the English language were, in addition to mastering the basic structures of the language, to interpret texts in order to prepare for higher education or vocational training.

Although the Classes Integrais used active methodologies, which sought to give voice to students and sought to implement the practice of the four skills (reading, writing, speaking, listening), they announced the preparation for the later level of education, the High School, and the student’s preparation for life, including the job market. To reinforce this statement, we shall remember that the Experimental Classes project, which was implemented nationally, aimed to raise the standards of secondary education based on new methods and principles, fully training students and making them suitable for the society in which they lived.

It is interesting to notice the two parallel proposals that took place in that period: the Common Classes, adopting the technicist precepts and conducts that were slowly being instituted; while the Classes Integrais looked for alternative methods to teach the same contents.

Classes Integrais, making use of the most diverse materials, sought to expose American and British culture through their characteristics and customs. Even so, only with the intention of demonstrating the culture of the native-speaking countries of the studied language. Through it, the teaching of the English language crossed the school culture and also imposed elements of economically developed cultures on it.

Finally, we want to highlight the importance of this study for having entered into the reports of the practices carried out by English Language teachers and with that having pointed out a moment of change in the teaching of this subject, following the precept that “It is advisable to carefully examine the evolution of school subjects, taking into account several elements (...): the content taught, the exercises, the practices of motivation and stimulation of the students, which are part of these “innovations” that are not seen” (JULIÁ, 2001, p. 34).

REFERENCES

CASIMIRO, Glauce S. A língua inglesa no Brasil: contribuições para a história das disciplinas escolares. Campo Grande: Editora da Uniderp, 2005. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A história cultural: entre práticas e representações. Trad. Maria Manuela Galhardo. 2.ed. Difel, p.13-28, 2002 [ Links ]

CHAVES JUNIOR, Sergio Roberto. As inovações pedagógicas do Ensino Secundário brasileiro nos anos 1950/1960: apontamentos sobre as classes integrais do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. In: Cadernos de História da Educação, v.15, n.2, p. 520-539, maio-ago. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v15n2-2016-4 [ Links ]

CHAVES JUNIOR, Sergio Roberto. “Um embrião de laboratório de Pedagogia”: as classes integrais do Colégio Estadual do Paraná no contexto das inovações pedagógicas no ensino secundário (1960-1967). Tese (Doutorado em Educação), 270 f. Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2017. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO ESTADUAL DO PARANÁ (CEP). Relatório anual. Classes Integrais. Curitiba. 1960. Acervo do Centro de Memória do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO ESTADUAL DO PARANÁ (CEP). Relatório anual. Classes Integrais. Curitiba. 1961. Acervo do Centro de Memória do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO ESTADUAL DO PARANÁ (CEP). Relatório anual. Classes Integrais. Curitiba. 1962. Acervo do Centro de Memória do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO ESTADUAL DO PARANÁ (CEP). Relatório anual. Classes Integrais. Curitiba. 1963. Acervo do Centro de Memória do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO ESTADUAL DO PARANÁ (CEP). Relatório anual. Classes Integrais. Curitiba. 1964. Acervo do Centro de Memória do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO ESTADUAL DO PARANÁ (CEP). Relatório anual. Classes Integrais. Curitiba. 1965. Acervo do Centro de Memória do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO ESTADUAL DO PARANÁ (CEP). Relatório anual. Classes Integrais. Curitiba. 1966. Acervo do Centro de Memória do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO ESTADUAL DO PARANÁ (CEP). Relatório anual. Classes Integrais. Curitiba. 1967. Acervo do Centro de Memória do Colégio Estadual do Paraná. [ Links ]

DALLABRIDA, Norberto. Circuitos e usos de modelos pedagógicos renovadores no ensino secundário brasileiro na década de 1950. Hist. Educ., Santa Maria, v. 22, n. 55, p. 101-115, ago. 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/80587 [ Links ]

JULIA, Dominique. A cultura escolar como objeto histórico. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Campinas/SP, n. 1, p. 9-44, 2001. [ Links ]

MIGUEL, Maria Elisabeth Blanck. A reforma da Escola Nova no Paraná: as atuações de Lysímaco Ferreira da Costa e de Erasmo Pilotto. In: MIGUEL et al. (orgs.). Reformas educacionais: as manifestações da escola nova no brasil (1920 a 1946). 1ed. Campinas - São Paulo: Editora Autores Associados, 2011, p. 121-137, 2011. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Luiz Eduardo M. de. A historiografia brasileira da literatura inglesa: uma história do ensino de inglês no Brasil (1809-1951). Dissertação (Mestrado) 195 p. Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem, Campinas, SP, 1999. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Secretaria de Educação e Cultura. Programas de Ensino Médio. Curitiba, 1962. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Secretaria de Educação e Cultura. Articulação e Integração no Ensino de 1º Grau (Diretrizes Teóricas dos Currículos de 5ª e 6ª séries do Ensino de 1º Grau). Revista do Ensino. Porto Alegre, RG, n. 147, suplemento especial n. 4 - Educação no Paraná - 1972. [ Links ]

REDONDO, Diego Moreno. Dos Double-manuals aos Single-manuals: uma retrospectiva histórica do ensino de inglês. Odisseia, Natal, n. 10, p. 1-20, jan./jun. 2013. [ Links ]

STRAUBE, Ernani Costa. Do Licêo de Coritiba ao Colégio Estadual do Paraná 1846-1993. Curitiba, PR: Fundepar.1993. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Letícia; CHIOZZINI, Daniel Ferraz. Luis Contier como catalisador de redes: Classes Experimentais e renovação do ensino secundário em São Paulo nas décadas de 1950 e 1960. Hist. Educ., Santa Maria, v.22, n.55, p.61-80, ago. 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/80603 [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Leticia; DALLABRIDA, Norberto. Classes experimentais no Ensino Secundário: o pioneirismo de Luis Contier (1951-1961). Cadernos de História da Educação, EDUFU - Editora da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, MG, v.15, n.2, p. 492-519, out. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v15n2-2016-3 [ Links ]

2Progressive proposal, with an active method, inspired by the ideas of the right to education - public and free to all citizens, and aimed at the development of teaching autonomy, teaching heritage - then, the fight against social institutions. In Brazil, it gained notoriety in 1932, with the Manifesto dos Pioneiros, featuring names such as Fernando de Azevedo, Lourenço Filho and Anísio Teixeira (MIGUEL, 2011).

3About the influence of these classes on the Classes Experimentais in Brazil, see “Luis Contier as a catalyst for networks: Experimental Classes and the renewal of secondary education in São Paulo in the 1950s and 1960s” by Vieira and Chiozzini (2018).

4For more on the introduction of Classes Experimentais in Brazil, see “Classes experimentais no Ensino Secondário: o pioneirismo de Luis Contier (1951-1961)” by Vieira and Dallabrida (2016).

Received: November 01, 2021; Accepted: February 07, 2022

texto en

texto en