Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-152

Dossiê 1 - História da formação e do trabalho de professoras e professores de escolas rurais (1940-1970)

Memories of teachers in the amazon region: work and ways of teaching in rural schools in the third quarter of the 20th Century1

1Universidade Federal de Rondônia (Brazil). josemir.barros@unir.br

2Instituto Federal de Educação Ciência e Tecnologia de Rondônia (Brazil). marcia.nunes@ifro.edu.br

3Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Rio Grande do Norte (Brazil). andressa.lima@ifrn.edu.br

The investigation is about teachers from rural schools in the Amazon region, North of Brazil, today the state of Rondônia. The time frame begins in 1955 with the creation of the Rural Social Service, linked to the Ministry of Agriculture. The final year of the research is 1971, with the creation of the Association of Credit and Rural Assistance of the Federal Territory of Rondônia. The objective is to identify and analyze ways of teaching the work of rural teachers and school infrastructure in the Brazilian political and economic context, given the migration of settlers to the Amazon region. Ways of teaching are scrutinized from the work of teachers in multigrade rural schools in the Amazon. The methodology is based on sources: laws, decrees, books and semi-structured interviews carried out with three teachers, through the Google Meet platform, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was found that ways of teaching and teaching work are articulated with teaching and thinking of teachers.

Keywords: Rural education; Rural teacher; History of Education

A investigação é sobre professoras de escolas rurais na região amazônica, Norte brasileiro, hoje estado de Rondônia. O recorte temporal tem início em 1955 com a criação do Serviço Social Rural, vinculado ao Ministério da Agricultura. O ano final da pesquisa é 1971, com a criação da Associação de Crédito e Assistência Rural do Território Federal de Rondônia. O objetivo é identificar e analisar modos de ensinar, o trabalho de professoras rurais e infraestrutura de escolas em contexto político e econômico brasileiro diante da migração de colonos para a região amazônica. Perscrutam-se os modos de ensinar a partir do trabalho de professoras em escolas rurais multisseriadas na Amazônia. A metodologia se ancora em fontes: leis, decretos, livros e entrevistas semiestruturadas realizadas com três professoras, por meio da plataforma Google Meet, diante da pandemia da COVID-19. Constata-se que modos de ensinar e trabalho docente estão articulados ao fazer e pensar docente.

Palavras-chave: Ensino rural; Professora rural; História da Educação

La investigación trata sobre docentes de escuelas rurales de la región amazónica, en el norte de Brasil, hoy estado de Rondônia. El marco temporal inicia en 1955 con la creación del Servicio Social Rural, vinculado al Ministerio de Agricultura. El último año de la investigación es 1971, con la creación de la Asociación de Crédito y Asistencia Rural del Territorio Federal de Rondônia. El objetivo es identificar y analizar las formas de enseñanza, el trabajo de las maestras rurales y la infraestructura de las escuelas en el contexto político y económico brasileño, ante la migración de colonos a la región amazónica. Se examinan formas de enseñanza a partir del trabajo de los docentes en escuelas rurales multigrado de la Amazonía. La metodología se basa en fuentes: leyes, decretos, libros y entrevistas semiestructuradas realizadas con tres docentes, a través de la plataforma Google Meet, ante la pandemia COVID-19. Se constata que los modos de enseñar y el trabajo educativo se articulan en el hacer y pensar docente.

Palabras clave: Educación rural; Maestra rural; Historia de la educación

For sailors with a desire for wind,

memory is a starting point.

(GALEANO, 1994, p. 96)

Introduction

Education carries specificities that give it the character of complex activities. In this way, all dialectical scientific investigation matters to us. “Education is a human social practice; it is an unfinished historical process that emerges from the dialectic between man, world, history and circumstances” (GHEDIN; FRANCO, 2011, p. 40).

The objective of the research was to identify and analyze the ways of teaching and the work of rural teachers and school infrastructure in the Brazilian political and economic context given the migration of settlers to the Amazon region. Ways of teaching are scrutinized from the work of teachers in multigrade rural schools in this region.

The temporal cut begins in 1955, with the creation of the Rural Social Service, created through Law n. 2613, of September 1955, linked and subordinated to the Ministry of Agriculture.

Art 3 The Rural Social Service will aim to:

I. The provision of social services in rural areas, aimed at improving the living conditions of its population, especially with regard to:

a) food, clothing and housing;

b) health, education and sanitarian assistance;

c) to the incentive to the productive activity and to any enterprises in order to value the ruralist and to fix him to the land.

II. Promote learning and improvement of work techniques suitable for rural areas;

III. Foster the economy of small properties and domestic activities in rural areas;

IV. Encourage the creation of communities, cooperatives or rural associations;

V. Carry out surveys and studies for knowledge and dissemination of the social and economic needs of rural people;

VI. Provide the Social Security and Labor Statistics Service every six months with statistical reports on the remuneration paid to rural workers. (BRASIL, 1955).

The year 1971 is the final cut of the research; the landmark of the creation of the Association of Credit and Rural Assistance of the Federal Territory of Rondônia (Associação de Crédito e Assistência Rural do Território Federal de Rondônia, ACAR-RO), with the objective of promoting rural extension.

The research relies on several sources, including laws, decrees, bibliographic materials and semi-structured interviews carried out with three teachers who worked in rural schools in the interior of the state of Rondônia. Official documents, such as laws and decrees, were collected from the archives of the virtual library of the Senate of the Republic of Brazil. The semi-structured interviews were carried out in the second half of 2021, through online platforms, given the pandemic scenario of the new coronavirus, Covid-19 in Brazil.

The audio and video interviews had a script or guide previously prepared and were recorded and transcribed in full, and this process enabled important analyses. Oral sources are part of the testimonies.

As mentioned by Ricouer (2007, p. 176): “The testimony is originally oral; it is listened to, heard. The file is written; it is read, consulted. [...] testimony, we said, provides a narrative sequence to declarative memory”.

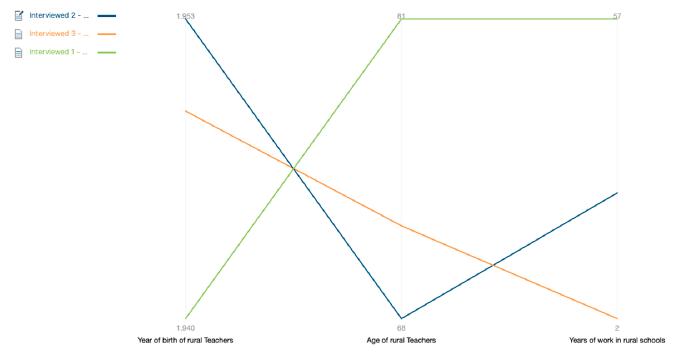

The teachers interviewed have proven experience in teaching in the Amazon forest area: Teacher 1 has been working for 57 years; Teacher 2 has 25 years of experience, and Teacher 3 has 2 years of teaching experience. They were born, respectively, in 1940, 1953 and 1949. The age of the interviewees corresponds to 81, 68 and 72 years old. In all, it took 2 hours and 55 minutes for recordings made in September 2021, totaling 54 pages of transcripts.

Source: The authors, based on interview data and with resources from the Maxqda 2022 software

Figure 1 Interviews with rural teachers.

Data from semi-structured interviews correspond to the narratives and were categorized based on two axes: i) infrastructure of rural schools, and ii) ways of teaching and work of rural teachers. The Maxqda qualitative analysis software was fundamental for a better systematization of the collected materials. Gibbs (2009) discusses the importance of categorizing field data through the use of software in qualitative research.

According to Barros and Ferreira (2020, p. 448), “[...] in the testimonies of rural teachers, we perceive both the pedagogical practices [ways of doing] used in the intricacies of their classes and the ways in which the teachers created shortcuts to assert their profession [...]” as laypeople.

It is worth noting that, in the time frame from 1955 to 1971, the focus of the research, the three rural teachers were lay teachers, working in different schools, many under the responsibility of the government of the Federal Territory of Rondônia. Initial training came later to only one of them, almost a decade after the final mark of the research cut, through a lay teacher training program, called ‘Logos II’. Nunes (2019) describes that Logos II was a type of emergency training to train and qualify lay teachers, especially in rural schools, and there was no relationship between what the teachers learned in the course and the context of the rural Amazon rainforest in which they worked.

Rural teachers from Rondônia present in their narratives significant experiences in teaching, ways of thinking and doing education in the Amazon rainforest region and in the Brazilian context of authoritarianism installed with the Military Coup of 1964.

The Brazilian context of the Years of Lead

Brazil in the 1960s experienced the hardships of the beginning of the military period, which lasted from 1964 to 1985. The military dictatorship was discursively presented as one of the possibilities to rid the country of corruption and the danger of communism.

From 1964 to 2022, it is clear that, in the history of Brazil, there are recurrences or permanences. The current president of the republic, Jair Messias Bolsonaro, elected in October 2018, egress from the military career, relied on false speeches to convince part of the Brazilian electorate about the imminent risk of communism and of putting an end to corruption.

Jair Bolsonaro's victory in the 2018 presidential elections is due to several factors, among which stands out: the removal of President Dilma Rousseff, on August 31, 2016, through a coup, the impeachment.

The impeachment process of President Dilma Rousseff, consummated by the Senate on August 31, 2016, sets up as a very difficult struggle. On the one hand, because there is still no temporal distance that allows us to make more precise analyses. On the other hand, the consequences resulting from such an event for Brazil and, in particular, for Brazilian public institutions, are not fully known. Furthermore, it must be considered that the events that led to Dilma Rousseff's impeachment are still ongoing. (SILVA et al., 2017, p. 2).

Comparatively, the 1964 military coup and the impeachment process of President Dilma Rousseff (2016 coup) present facts that are close to each other. If, as of 1964, the so-called Institutional Acts (AI), as decrees, began to establish guidelines in the name of the exercise of Constituent Power; in 2016, a broad game of essentially political interests determined the nation project again, the coup-prone bias in a new guise, although without the visible participation of the military in the articulation process.

With the presidential inauguration, in 2019, Jair Bolsonaro, a retired army officer, received support of security forces from the municipal, state and federal spheres. A government was instituted with proposals for the militarization of education, permitting the carrying of weapons for civilians and unfounded attacks on Brazilian science.

The arguments on which the propagation of the “new” nation project to rid Brazil of corruption is based are well-known strategies. These are “reheated” stories and speeches that, articulated with ideological persuasion, were disseminated through Fake News, that is, untruths with the purpose of winning the 2018 presidential elections.

On the one hand, the results of the 2018 presidential elections in Brazil were indicative of damage to democracy and discredit of the scientific community on the part of the presidency, with substantial cuts in funding lines for universities and federal institutes.

In Brazil, there is an intense movement of parliamentarians from the president's support base to strengthen the Executive Power and reduce the field of action of the various organizations - councils, unions, social movements, among others.

In each of the contexts, the military coup in 1964 and the impeachment coup of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016, the conflicts of interests manifested by different sectors of the capitalist bourgeoisie had repercussions, in order to present limitations in the processes of democratization of opportunities, mainly in the social sphere. Demonstrations against the 1964 coup, as mentioned by Ventura (1988), student marches spread throughout the country. The 2016 coup was supported by the bourgeois media, as mentioned by Matias and Barros (2019).

In the meantime, the school is a preponderant factor, sometimes as a reproducer of capitalist society, sometimes in its Freirean aspect, which can provide better interactions between subjects, especially critical awareness. “Critical consciousness ‘is the representation of things and facts as they occur in empirical existence’” (FREIRE, 2001, p. 113).

It is a fact to note that schooling in the 1960s did not and still does not have a homogeneous development throughout the Brazilian territory. The inequalities in care are complex and acute:

While in some regions the education system seems to be finally approaching the realization of the old pedagogical ideal of a universalized common school, in other areas, in the poorest states and, in general, in rural areas or in some sectors of the periphery of the urban centers, also generally populated by massive migratory contingents from rural areas, the network of schools is still far from absorbing the totality of schoolable inhabitants, even in the first grade of the common school. (HOLANDA, 1995, p. 399).

In rural regions, there is a lack of schools, teachers and other pedagogical artifacts to institute the teaching and learning process - a situation that in many cases reproduces the exclusion of the poorest from the education systems.

In the case of rural schools, one can find teachers without specific teaching training and in effective exercise; they are lay teachers.

Regardless of having a teacher education course or not, in the 1960s, the lay teacher was the only alternative to teach children to read and write in the Amazon region. The rural school, when it was the focus of the authoritarian State's interest, began to be supervised by the Army itself; and the idea was to avoid the proliferation of ideas contrary to bourgeois capitalist ideology, instilling fear of communists.

My father's assistant went to receive the military. They arrived and asked: I was aware that there is a school here in this house. The employee pointed to me and said: The teacher is there. He looked at me scared and said: That girl over there?! I said: Yes, sir, captain, I'm the teacher, and he said: What are you doing in the pigsty with these boys? I am teaching them how pigs eat, how pigs live, what they are for, what you serve pigs, I said. He looked at me and shook his head and said: You're teaching well, but you don't have any books. He asked: What book do you have there? I said: Let's go to the small room and I'll show you. Then I opened the boxes of books, I showed everything, he said: Okay, it's within the rules [...], he continued saying: I know your father has a book of Karl Marx. I said: Yes. The captain said: We came to get it. I said: No, you didn't come to get it, because it's not yours, it's my father's, and it's in the locked trunk. The captain asked: Do you have access to it? I said: No, I don't have it, because my father doesn't let us read. Why does your father have this book? [the captain asked, and added]: Is he by any chance a communist? I said: Sir, he is Brazilian, he is nationalized as Brazilian, and he is an excellent father; a farmer who helps needy families. Then the captain shut up... they already knew that my father had this book. So that day you can't imagine how much I was shaking with fear [...]. (TEACHER 3, 2021).

In the interview fragment of the lay rural teacher, it is possible to verify how the one-room rural school was improvised by the family itself. In a “little room”, the teacher was a skinny girl, the daughter of farmers, who taught as best she could, with few materials. In her activities, there was the practice of dealing with rural life, in this case, raising pigs. In the improvised little room, in her own house in a rural area of the Amazon region, the teacher, in her effective exercise, handles a set of cognitive skills to teach other children.

The debate instituted by the lay teacher with the captain of the Brazilian Army corresponds to the idea that lay culture is a type of space in which social reality is reconstructed from what is seen or known. In turn, the captain makes use of the “[...] belief in the assumption that, to our human nature, the homo educandus species begins to be shaken as he studied the history of the economic concepts of Mandeville and Marx [...]” (ILLICH, 1991, p. 40 - author's emphasis). Hence the preoccupation with the status quo, with order and progress; slogans established in the face of the violence and authoritarianism of the repressive period of the military dictatorship.

The political context expressed is one of oppression and the absence of political actions consistent with rural communities in the Amazon region - a perfect combination to generate contempt in the scope of public policies. The State is the producer of a certain set of attitudes or cultural conventions to spread its project of nation. The school is one of the stages or locus of the implementation of State attitudes and/or conventions, especially when the Legal Amazon2 is mentioned in the face of the process of expansion of the agricultural frontier.

The expansion of the agricultural frontier to other axes - Central-West and North regions, has frequent variation based on conditioning factors, used to intensify the development of the economy - follows the expansion of transport networks, whether rail or road. “[...] The expansion of the agricultural frontier during the last decades [military period] was, ultimately, a result of the new pattern of accumulation of the Brazilian economy, and the concentration - functional, sectoral and regional - of the income that it engendered” (HOLANDA, 1995, p.129).

The expansion of the agricultural frontier caused an intense migratory process to the Amazon rainforest region, especially during the military period. One of the examples corresponds to the National Integration Plan (Plano de Integração Nacional, PIN), instituted from Decree-Law No. 1,106, of July 16, 1970 in the authoritarian government of Emílio Garrastazu Médici, who persecuted his opponents, intensified torture, censored the media, among others, in addition to being one of the most violent governments.

In the National Integration Plan, article 1, there is a budget allocation of two billion cruzeiros, voluminous resources used between the years 1971 to 1974. In “Art. 2. The first stage of the National Integration program will consist of the immediate construction of the Transamazônica and Cuiabá-Santarém highways”. In item 1, it can be verified that “a strip of land of up to ten kilometers to the left and right of the new highways will be reserved for colonization and agrarian reform, in order, as the resources of the National Integration Program, to carry out the occupation of the Earth and adequate and productive economic exploitation” (BRASIL, 1970).

In the reports produced by the Economy and Budget committees of the federal senate on Decree-Law n. 1,106, of July 16, 1970, we find: i) Economy - “the new National Integration Program contains heroic measures in a certain sense; a sacrifice for investors in southern regions regarding the possibility of implementing specific projects for primary and secondary economic activities in the North and Northeast” and ii) Budget:

Alongside industrialization, strengthening agriculture in the semi-arid zone and in the humid valleys so that it can absorb a level of productivity, the largest possible portion of the population existing there ‘is opening an alternative for surplus labor’ because any compulsory measure on to be unenforceable would be hateful and intolerable [...].

VI - Two words about the Integration of the Amazon region not only to the Northeast, but to Brazil: It is already a cliché to say ‘Integrate in order not to deliver’. The occupation of these vast empty spaces is a challenge for our generation. The creation of SUDAM, from Porto Franco de Manaus, were already important steps, but not enough, together with the patriotic work of the engineering battalions, to not even start such a start. (BRASIL, 1970).

President Médici adopted an agricultural-export development model, based on the Strategic Development Program (Programa Estratégico de Desenvolvimento, PED), launched in previous years. The aim of creating a mass market and essentially focused on agricultural expansion, as one of the possibilities to raise the economy and expand the desired industrialization, according to Macarini (2005) exposes the history of the Medici nation project.

The Integrated Colonization Projects (Projetos Integrados de Colonização, PICs) were implemented by the Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Instituto de Colonização e Reforma Agrária, INCRA). According to Oliveira (2001), several population groups from the South, Southeast and Center-West regions of Brazil moved to the Amazon region in search of better living conditions and access to land.

Within this context, with the enlargement of the agricultural frontier, the agrarian-export model, and the motto “Integrate to not deliver”, we find the slogan “Land without men, for men without land” - an advertisement to fill the demographic voids of the Amazon. This process, which generated an intense migratory flow, fueled violence against indigenous and traditional populations, all in the name of integration, that is, the economic development of the Legal Amazon.

From the Federal territory of Guaporé to the state of Rondônia

Through Decree-Law no. 5812, of September 13, 1943, several federal territories were created in Brazil. In “Art. 1st The Federal Territories of Amapá, Rio Branco, Guaporé, Ponta Porã and Iguassú are created with dismembered parts of the States of Pará, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Paraná and Santa Catarina”. On the Federal Territory of Guaporé, we have item 3, which established the following limits:

- to the Northwest, by the river Ituxí until its mouth in the river Purús and by this one down to the mouth of the river Mucuim;

- to the Northeast, East and Southeast [sic], the Curuim River, from its mouth in the Purús River to the parallel that passes through the source of the Cuniã Igarapé, continues along the aforementioned parallel until reaching the head of the Cuniã Igarapé, going down this one to its confluence with the Madeira river, and down this one to the mouth of the Gi-Paranã (or Machado) river, going up to the mouth of the Comemoração or Floriano river, it continues up this one to its source, and from there it continues along the Vilhena plateau watershed, skirting it to the source of the Cabixi River and descending it to the mouth of the Guaporé River;

- to the South, Southwest and West by the limits with the Republic of Bolivia, from the confluence of the Cabixí river in the Guaporé river, to the limit between the Territory of Acre and the State of Amazonas, along the boundary line it continues until it finds the right bank of the river Ituxí, or Iquirí. (BRASIL, 1943).

The creation of the Federal Territory of Guaporé is also related to the national security plan established in the period of Getúlio Vargas, from 1930 to 1945. The interest in protecting geographic borders is something explicit.

In 1956, through Law no. 2,731, of February 17, 1956, the Federal Territory of Rondônia was created, in “Art. 1. The name of the Federal Territory of Guaporé is changed to the Federal Territory of Rondônia” (BRASIL, 1956). The name Rondônia comes from the activities carried out by Marshal Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon: expeditionary actions to map and colonize regions. Rondon opened trails in the forest, implemented telegraph lines and, although he founded the Indian Protection Service (Serviço de Proteção ao Índio, SPI), which proposed friendly contact with indigenous people, the annihilation of native populations occurred due to contact with whites, a clash of cultures. The lands cleared by Rondon became part of the expansion of the agricultural frontier.

From the Federal Territory of Rondônia to the state of Rondônia, one can see the intensity of the economic project of development and colonization, even from deforestation, which caused damage to natural ecosystems, especially to indigenous peoples.

The state of Rondônia was created by Complementary Law n. 41, of December 22, 1981: “Art. 1st - The State of Rondônia is created, through the elevation of the Federal Territory of the same name to this condition, maintaining its current limits and confrontations. Art. 2nd - The city of Porto Velho - will be the capital of the new state” (BRASIL, 1981).

Pedlowski et al. (2006) mention that the state of Rondônia played a strategic role in the process of economic development in view of the deliberations of the World Bank, in addition to being a source of natural resources for the production of pharmaceuticals from flora and fauna inputs.

The history of the state of Rondônia is intertwined with the settlements of populations from other regions of Brazil, projects of the military governments from the 1960s onwards, to establish settlers, protect borders, promote economic growth, intensify the use of natural resources and, somehow, garner political support, as it was the prerogative of the Federal government to appoint the governor of the Federal Territory of Rondônia - a kind of intervener - and, in this way, count on electoral support on its various fronts and locations.

Given the contexts in which the migratory flow intensified to the North region in an area of forest, the school was necessary. But in the end, which school? A school to serve the population centers, together with the occupation of demographic voids? “Communities often anticipate government action, installing schools in physical spaces built by them, under the direction of teachers chosen from among their members” (LIMA, 1993, p. 9). In the excerpt, two aspects can be seen: the first concerns the interest and concern of the settlers with the educational instruction process, leaving them with no other option but to build the school with their own hands; the second aspect deals with the delay and technical incapacity of governors, sometimes President of the Republic, sometimes governor/intervener of the Federal Territory of Rondônia to implement rural schools.

Rural schools in the Amazon context

The narratives of the three lay rural teachers dealt with some of the characteristics of Amazonian schools, the current geographic space from the North to the Southern Cone of the state of Rondônia.

The interviewed teachers taught classes in the municipalities of Guajará Mirim, Porto Velho, Cacoal, Vilhena and Pimenta Bueno, between 1955 and 1971 - all cities in the Federal Territory of Rondônia. Of the three interviewees, two are from the Northeast region and one from the South of Brazil; moved to the Federal Territory of Rondônia from the so-called “March to the West” - a migration process instituted in the military period for the colonization of the North region of Brazil. The effects of the migratory flow in the then territory of Rondônia is a retrospective that can help to perceive the increase in the quantitative population of the region between the years 1950 to 1970.

Table 1 Number of inhabitants of the Federal Territory of Guaporé.

| Number of inhabitants | |

|---|---|

| Years | Inhabitants |

| 1950 1960 1970 |

36.935 69.792 111.064 |

Source: INEP (1950, 1960 and 1970 Census. Data organized by the authors).

In the years from 1950 to 1970, there was a large-scale increase in the inhabitants of the region, a situation that required a greater number of schools. Silva (2019) contextualizes the demographic swelling experienced from the 1950s onwards and the opening of rural schools, showing how much the population increase affected educational demands.

The accelerated migration to Rondônia also caused a chaotic context in education [...]. The families that entered here demanded educational assistance, so, many schools began to function in a disjointed way [...]. In other words, the school structures were precarious, and the teachers were not qualified, the so-called lay teacher. (SILVA, 2019, p. 43).

Rural schools were far from urban centers, they made up the Amazon rainforest region, and accessing them was not easy. Teacher 1 narrated what she did to get to school: “You will go down the Madeira River, then you will take the Pimenta River, which is the Jamari River and go, go, go away. Go there in Extrema with Cuiabá, and I say: 'There! I went there!’ [...] There was only weeds there”. In that context of teaching work in the middle of the bush, in a forested area, the rural school was an attraction; Indigenous peoples approached the classroom and, according to Teacher 2 (the first teacher at a rural school in the city of Cacoal), the native ones caused a certain astonishment among the whites.

One of the facts that impressed me a lot... When I left Castanhal I went to teach in Riozinho and I was the first teacher at Escola Maria do Carmo do Riozinho, and at that time the Indians were still walking around naked on the street. When it was time to release the students, I was stuck at school... me and two other students who came from Porto Velho; they were terrified of these Indians, they had never seen them either, they were children and I stayed at these people's houses. And the three of us were stuck at school because they were at the window, wanting to get the notebooks, things. I used to go home with the material and they would come at me wanting the students' notebooks and I was scared to death with that! It was something that impacted me a lot; marked me a lot. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Indigenous peoples living in the Amazon rainforest were excited about the news, after all, the rural school was something different from what they knew. The teacher adds that she later managed to build a school on her own farming place.

The school was here at my place. Because when they went to build the schools, they had to be every 4 kilometers. Then the first was at the entrance where I worked; the school was called Machado de Assis. Then when I was transferred here, the school was supposed to be on plot 5 of all the schools on the line, only mine is on plot 4 because the neighbor across the street was from Sergipe and did not accept to have the school on his plot of land. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Lay teachers, their families and communities were responsible for building schools, donating trees to be sawn, helping to build and assisting in school maintenance, due to absences from the government.

Nunes (2019) highlights the assignment of land, donation of wood for the construction of schools by communities in the Southern Cone of Rondônia, a practice that extended to other historical periods and other geographic regions.

According to the narratives, rural schools were made of straw, tapiri and wood. Table 2 helps to understand part of the infrastructure characteristics of rural Amazonian schools.

Table 2 Infrastructure of rural schools.

| Interviewed Teachers | Compositions | Fragments of interviews with lay rural teachers |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher 1 (2021) | Rural schools | There was no blackboard there, and I had to fix it. I made a raffle here and managed to buy a blackboard. We stayed here at the school, just me for 63 students [...]. We didn't even have a school meal. I was janitor, the lunch lady, the teacher and the principal. And I said that if I had to make the lunch, the gas was mine, the stove was mine, the cupboard was mine, the blackboard was mine, the mimeograph was mine. If I had things at school, I bought everything for my work, because I taught 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th grades. |

| Teacher 2 (2021) | Rural schools | The school always had a pattern, all made of wood. The schools had floors, it was a little high off the ground and I never understood why there were stairs for those children to climb; I don't know why they didn't do it right away [...] The only things that came from outside, that they sometimes bought in Pimenta Bueno or in Ji-Paraná, were tiles, nails, these things, because Cacoal didn't have a store at that time. Then the rest they made everything out of wood. |

| Teacher 3 (2021) | Rural schools | [...]The difficult thing really was the space. There was no way to build a built space. Something like that, comfortable, it wasn't [...] the bathroom was there in the bush. It didn't have that physical aspect, it didn't have these advantages, so my father had the bathroom houses built right outside, around the house that belonged to the boys and girls, that bathroom that is the hole in the floor, a board covering, which is a toilet. So he wrote 'boys and girls' himself, and he had a little door. It was really difficult the physical space and this difficulty of being everyone together. |

Source: The authors, based on interview data and with resources from the Maxqda 2022 software.

According to Thompson (1978, p. 183), “the facts that people remember (and forget) are themselves the substance of which history is made”. The lay rural teachers in their memories establish concreteness from the environments in which they worked and, above all, part of their experiences; a way of expressing their readings of a historical context marked by intense work to build rural schools with the material resources available in the region.

All practices and/or actions expressed by rural teachers for the composition of schools are not unique and isolated characteristics of the Amazon region, in Chaloba et al., (2020), examples can be found about the same temporal context and other locations in Brazil.

In any case, the rural school in the Federal Territory of Rondônia was a standard: made by various hands and with materials extracted from the Amazon rainforest itself; its operation relied on the existence of a network of supporters, whether from the teachers' and/or students' family members and the school community.

Teachers did everything in rural schools. They were responsible for the multigrade classroom without even having a training course for teaching; were lay people and took on attributions other than rural teaching within the scope of public administration: they built the schools, raised financial resources for the purchase of necessary basic materials, financed part of the expenses of school meals, cleaned, repaired and, above all, taught classes for children and young people of different ages in multigrade classrooms.

Ways of teaching and the work of rural teachers

When they were in charge of teaching in rural schools in Rondônia, the teachers were very young, they moved almost suddenly from playing to working. Teacher 3 recalled that she was between 15 and 16 years old and played with her dolls and “suddenly stopped being a child to be a teacher, to deal with laws and with students” (TEACHER 3, 2021). The teachers did not have any initial pedagogical training, they only relied on the knowledge of the experience they had, still in childhood, as students. The beginning of the teaching profession was guided by observations and reproductions of what they did, what they experienced as teachers' helpers in classroom activities, when their teachers were very busy and asked for someone to help them, passing the content on the board and correcting the colleagues' notebooks; “And with that I learned through [my] teacher” (TEACHER 1, 2021).

Schelbauer and Souza (2020, p. 368) explain that, when dealing with a rural teacher, “the value of experience is evident in the maxim 'I taught as I had learned', as people remember”. Teacher 2 confirmed that “I saw how her teacher taught and everything, then I did it. I started teaching by teaching; I took the hands of those who had never been to school, as if it were a preschool and there I taught” (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Teacher 3 said that, after finishing the 5th year of primary school, she did not enter the gym because she was invited to teach. He stated that, over time, the difficulties with classroom practice became moments of teaching learning: “I learned from the students themselves; it was with their difficulties that I continued to learn” (TEACHER 3, 2021). She says that, in addition to letters and numbers, before starting the school contents themselves, it was necessary to teach about education in a broader way, such as good manners, ways of sitting and socialization of students.

The teaching task was to teach students until the students actually learned. When something was taught and it was noticed that a student did not learn, the teacher tried to plan in a different way to teach, testing until it worked, that is, until the student learned. The students' learning was simultaneously the teacher's greatest concern and greatest gratification, although her references for teaching were her own work.

I was developing according to my needs: if yesterday I taught in a certain way and the boy had difficulties, he cried, it seemed that he did not understand, at night I already thought 'Tomorrow I will do the same subject but in a different way'. I set up another ‘scheme’ to work with this student individually. Then I felt if that new methodology had improved and I continued with it. If I taught and he didn't learn, I didn't think I wasn't competent to teach, I thought: 'I have to improve it’. (TEACHER 3, 2021).

Book, board, notebook, letters, numbers, drawings and a lot of creativity inside the room - practically everything was on the board and in the notebook. Rural teachers formulated exercises to link words to drawings and activities of circling and filling were constant. Schelbauer and Souza (2020) assert that, faced with scarce material resources, the use of the board, chalk, book and copy was even more accentuated.

Book and notebook. That was more or less all we used: blackboards, drawings... and we drew a lot. I also did an exercise to call, for example, the 2nd grade, I did the drawing and the word for them to do the drawing with the word. I liked to do a chess type for them to discover the word. Circular activities, for example, but it was all manual. Everything was on the board and in the student's notebook. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Other ways of teaching correspond to the inventive proposition of the lay teachers themselves, who divided the picture into parts: sometimes a part for each subject, other times a part for each grade, since they taught in multigrade rural schools. At the beginning of each part of the board, the teacher identified the class to which the activity would be directed. Other practices such as dictation, separating syllables, copying, reading, memorizing the multiplication table and solving math problems were part of the teacher's activities and knowledge in the rural school. At times, the use of books was one of the possibilities for implementing rural teaching.

We always followed the books at the time and did the exercises. It was all manual, all on the board. There was no way to type or do anything printed. The board was quite large and, to make it easier, I divided the board by subject or by grade. When I was Portuguese or in the 2nd grade, I always wrote there: 2nd grade. I drew a line, took a part of the board and there I went through the activities... we did a lot of dictation, separating syllables, copying. I made the students read so that we could hear who had the most difficulty and who already read well. We were very careful in Mathematics; in teaching multiplication tables; at that time, I had to know the multiplication table, do a lot of exercise to even memorize the multiplication table. We used to use those math problems too. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Reading and calculation were the main focus of rural teachers for students' school learning; were the most observed and worked on points, because there were demands from the Education Department when inspecting rural schools.

As the school only had the classroom, the teachers also used the external environment to teach; in Science classes, they created possibilities to observe and teach in direct contact with nature, that is, to plant and observe the development of plants. “[...] Sometimes I would leave the room and make the most of it when it was Science class, to see the plants. People planted. There where the school was, there are araçá trees, there are many plants that were planted at the time that we used them as exercise, as an activity (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Another very creative task, described by Teacher 1, was the so-called “surprise snack”, an activity that excited and introduced new words and foods not yet known by the students. Missing, the teacher recovers the memory that “the surprise lunch was a very big picture, nobody knew. The surprise was vatapá, it was salad, everything that children didn't know”. The aforementioned teacher described that she was even asked by the board of the Department of Education about having authorization to carry out this practice at school and promptly replied: “Me! I'm the school principal! I authorized it!!” (TEACHER 1, 2021). The teacher explained that she was alone to do everything at school, that is, according to Barros and Ferreira (2020), rural teaching was full of attributions: teaching classes was essential, but not the only activity developed. Rural teachers were everything at school and for school.

In the rural school, the teacher dealt with problems inside and outside the classroom and one of the examples is about absent students. The absences were usually related to the harvest season, in which, especially the boys, needed to help their parents in the fields, developing activities from the perspective of family farming; the child's work in the countryside was associated with the educational principle.

This was the biggest difficulty because, when the harvest time came, to harvest rice, the students were absent a lot because the father took them out of school to help in the fields [...] this interfered a lot with our work, because I only stayed with those who didn't go to the fields; the girls rarely went there, but the boys went more. I couldn't stop because of those who didn't come. When they returned to school, they were lost because we had already passed the lessons from the books and they were confused and we had to go back to teach, to show the whole exercise. It was almost like teaching them twice because they missed classes a lot. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Although children were part of family labor, and often the only possibility of helping in agricultural production for subsistence, Antuniassi (1983) mentioned that the early entry into work activities by children and young people living in rural environments harms and interferes negatively in the process of their schooling. The author explains that, “even when the child combines work activities with school activities at the peak of agricultural activities, they fail to attend school to help their parents” (ANTUNIASSI, 1983, p. 42-43). This reality can generate significant dropout rates, that is, discontinuity in the appropriation of formal - school knowledge - necessary for a better understanding of the contexts in which they are inserted.

Antuniassi's assumptions (1983) can be seen when rural school teachers narrate that it was not possible to stop the content for the students who were attending and, after the absent students returned from the harvest, they were oblivious to the content developed in the classroom, so it was necessary to pick up where they left off to go back to teaching, doubling the teaching work. An action developed by lay teachers to try to get around the situation was a kind of relocation of the students inside the classroom itself, that is, when they returned from work in the countryside, after days without attending class, the students were reassigned to a grade according to the teacher's evaluations.

Although they had no pedagogical training, the teachers practically prepared the planning for the teaching activities and followed it at school. The lesson plan provided guidance on what to teach, how to teach, and the organization of scarce materials based on the real needs of their students. The teachers, according to Alencar (1993), had understanding about the process of obtaining and fixing knowledge for themselves and for the students.

It was necessary to have a lesson plan to know what was going to happen on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday. You have to know what you are going to (sic) teach on the day. You have to organize the materials, Portuguese and Mathematics, which are mandatory, but we have Social Sciences and there are other things that the teacher tries to create, especially when he realizes that he doesn't have a certain study and doesn't know certain things. So we have to organize ourselves according to reality, according to need. (TEACHER 1, 2021).

The teaching planning evidenced the expertise of the teachers, who, although lay ones, mobilized their knowledge in order to organize materials and subjects in proportion to the time and the weekly school days to establish ways of teaching children and young people in the Amazon rainforest region. The Department of Education did not participate much in terms of teaching planning; the document (maps) sent to the schools to guide the work of the teachers was not enough.

Teacher 3 reports that she received only a few written instructions from the Department of Education called maps, which served to guide teaching, from literacy to the fourth year. In the multigrade school, the teacher organized the teaching of the various grades, serving students of different ages and levels of knowledge in the same room simultaneously. The materials worked on in each series were different, “all the maps came, all the guidelines on how to work from the little boys in literacy to the boys in the third or fourth year. Everything came separately. Only the students were together, but the material was separate” (TEACHER 3, 2021). Teacher 1, on the other hand, presents a contradiction, stressing that “the Department did not send the contents ready, and I had to formulate my lesson plans. It was not to copy what the Department imposed; they sent only a direction to prepare the classes with the necessary content” (TEACHER 1). Teacher 2 also confirms that:

I planned at home; I knew what I was going to present in class the next day, what I had to do. I couldn't go there and flip through the page, looking for what I was going to teach that day. In addition to correcting [students' activities], the other day I already knew what I was going to do. I had a plan, I marked the right way, I tried to do the exercises. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Subsequently, the contents worked by the teachers were recorded in another type of document, also called a map, which was delivered to the Department of Education, so that “each month, for literacy, there was a space to insert what I had taught within that planning; I would transfer that planning after teaching it to a ‘map’, like some notebooks, then I would transcribe what I had worked with” (TEACHER 3, 2021).

The multigrade room was organized in rows of desks, separating students into small groups according to the grade to which they belonged: “I placed [the students] in the 1st grade all close together. I put those from the 2nd, 3rd grades and the last ones were from the 4th grade” (TEACHER 2, 2021), and, according to this marking, the teacher organized the content on the board, separating the activity for each grade corresponding. Rural teachers constantly reinvented ways of thinking and doing education in the face of needs, contexts, the public and the few resources they had.

The daily lives of rural teachers were based on the realities of one-room schools: consequently, multigrade; the table was divided to enable activities with the different grades. Teachers were responsible for the schools in their entirety and used the recurring structure of rural schools: blackboard, chalk and the work of the 1st to 4th grades of the first grade, in a single environment. Assim, a organização dos conteúdos ficava a cargo de cada um(a). Thus, the organization of the contents was in charge of each one. They taught children to read and write through basic principles, without any sophistication; each teacher used their own way and organization of the room/school. (BARROS et al., 2020, p. 1015).

The beginning of literacy was the most challenging point for the teachers. In many cases, they received few materials for the work, so it was necessary to improvise and be creative. Old spelling books, drawings, games, connecting the word to the drawing and circulating words made up the expertise created by the teachers to teach their students to read and write. Teacher 3 said that she made illustrations and related them to words to make sense to the student:

I made drawings for them to understand what it was, I put it, I materialized the words on top of a picture for them to learn. If the student wasn’t learning the word ‘daddy’, then I invented techniques and methods for him to learn which letters and who was daddy: I would draw a figure of a man, the same way I drew a figure of a mother, then I would say this is daddy, then he wrote D-A-D-D-Y, so they would know how to write the word. And so I created this technique of making drawings, I drew leaves, ants, birds, poorly drawn […] but I drew […]. There was an old ABC primer there; they had to scratch on a piece of paper where the letter that was that one was perforated. The student would look at a whole one and through that little hole in the letter he would write which letter was the one that was in that hole. This was for the ones I was starting to teach to read the first few letters. (TEACHER 3, 2021).

According to the students’ performance, the teacher created ways of teaching and activities focused on the development of each stage. Thus, the teaching work was very diversified, for example, for students who were starting to read, the teacher would listen to them and, if necessary, spell the words so that the student could learn to read. After mastering the reading, activities were carried out to transcribe words from the spelling book to the notebook. For students who developed faster, another booklet was offered for reading and copying in the notebook. Finally, when the student had already mastered the ability to read and write, the contents selected by the teacher were written directly on the board for the students to copy in their notebooks.

For the others, it was already the booklet for learning to read, which had those booklets that have 'the ship is grandma's', 'the ship is grandpa's' that had the word game. Then I would send copies of these in the notebook, I would go there, teach them to read, spell for them. Then they learned to spell and slowly transcribed those words from the booklet to the notebook; for the more advanced ones, who were already other primers, they also read and copied. So, while some were working, doing this activity, I would go to the board to write for those more advanced who no longer needed books that they already copied straight from the board. (TEACHER 3, 2021).

As can be seen in the previous excerpt, although a layperson, without specific training for rural teaching, the teacher had very different ways of teaching, based on a repertoire of activities that was built from her own practice: observing the difficulties of her students and making the necessary adaptations to their work in the rural school, at times, with the contribution of pedagogical materials.

It was noted, in general terms, that the issue of didactic-pedagogical and school material did not mean a consensus among the teachers; over the years, there was no pattern or continuity of actions. Teacher 3, who had her experience with rural teaching only during the years 1965 to 1967, when Rondônia was still the Federal Territory of Rondônia, described that there was a lot of material such as booklets, books and school supplies such as pencils, pens, notebooks and rubber, in addition to school lunches with a variety of canned, packaged and powdered foods. However, the school had a precarious infrastructure, there was no physical space to organize this material that came in boxes monthly, the school lunch needed to be stored and prepared at the teacher's house.

The difficulty was with the space, because the pedagogical material came all over, it came from the ABC booklet to the book; everything came, every month my father received the boxes, the boxes of school supplies, pencils, pen, eraser, even the snack, milk came, packages came, the cheese cans, the cans of canned fish that was to give the children's lunch, everything was made there at my house. So there were plenty of [...] resources for that; it came from outside, from the Federal Government, because it was still territory there, so there was a lot of material, it was a very great wealth of material [...] It was of great importance because a script was followed, not to mention the material for the student [...]. First came a calling map, which were the diaries, then the ABC spelling book, then other ones and books. And a lot of notebooks, lots of notebooks. (TEACHER 3, 2021).

Teacher 3 considered the support from the Federal Government to be very important, because, in addition to offering guidance to teaching practices, students were also benefited with specific materials for them.

Teacher 2, who worked in different periods, both in the Federal Territory of Rondônia and in the State of Rondônia, reported that the only material she received from the government was a spelling book, the teacher's book and the answer book.

It was really material, because they sent a handout and a teacher's book came according to the student's book. We had our book and what was in the student's book was in ours, but ours already had the answers, sometimes everything was already completed. Then we followed that there, if there were more other things I believe it would help, more different materials. But at the time there wasn't, it was just the books. It was just the teacher's book and we were guided by the materials they sent. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Teacher 2 reported that she received only basic school materials such as books, notebooks, pencils and erasers in sufficient quantity. However, there were no other materials for her to use in the preparation and improvement of her classes or in the development of activities carried out by the students; she didn't have cardboard, crayons and paints.

They only sent the school material, the teaching material, but not everything came, it was just books, notebooks, pencils, erasers, there was no shortage of that at school. Now they didn't have other materials: cardboard, colored pencils, everything was very difficult. If I was going to do a painting, I would paint it with my own pencil, they would do it themselves. And material for ourselves, didactic, also came very little at the time. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Teacher 1, who worked for 57 years in the teaching profession, from 1963 to 2020, narrated receiving basic school materials only once a year, in addition, the book was not consumable and this created a problem - so much so that she had to hold a raffle in the community, gathered money and bought consumables for his students.

The book came, but it was not consumable. So I found a way: I made a raffle here. I got money and sent for the consumable book in São Paulo. It was forbidden, but I ordered it, and it came. I used the consumable book. The book they sent helped with what to do at home, to learn to read. (TEACHER 1, 2021).

With regard to the activities that the teachers developed at school, there is unanimity: they did everything at school. In addition to planning and teaching classes, they were responsible for fetching food in the city to cook school lunches, cleaning and maintaining whatever was needed at school. As mentioned by Lima et al., (2016, p. 220), although in another geographic location in Brazil, but in a temporal context similar to this research: “[...] the teachers, even lay teachers, or maybe even for this reason, did not prostrate themselves in the face of the difficulties encountered in the daily life of the school.” Lay rural teachers did everything; were the mainstay of education in the locality where they worked.

For Teacher 2, the workload was doubled: “[...] you work double because you have to teach classes, bring all those notebooks to correct at home, grade by grade. And using a lamp, because at that time there was no energy”.

The work related to preparing lunch and cleaning, among other activities that the teachers performed in rural schools, ended up demanding ample dedication and more than doubled the workload. At home, and at night, and with the use of a lamp, corrections were made to the activities developed or elaborated by the students. In addition, the preparation or elaboration of the lesson plan was fundamental. To cope with all the work demanded at school, the teachers needed support, but it was little and limited. Within the school itself, the older students advised and collaborated with the activities, helping the teacher.

The water was far from the school. It was on the other side of the road and these children went to fetch water to make this lunch, to drink, we were experiencing all these difficulties. Now you think of my concern about these boys crossing this road to fetch water! But there was no other way, I couldn't leave them alone in the room and go get water. It was the older ones who went to pick them up and at the time there was almost no car passing by, it was very quiet. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

Working with children required greater care; at the same time, at the school, apart from the teacher and the students, there was no one who could help fetch water to drink, prepare and cook the lunch. So the older girls were the helpers. This situation reinforces the customs of a sexist culture in which the woman is responsible for the house.

When going to school, the teachers had no one to leave their children at home with, so they took them to work together, and again, at that moment, it was the older students who ended up helping the teacher.

I took my children to school because I had no one to leave them with at home. Sometimes, they took the child, they went outside because the children got tired, they got sick, wanting to leave; the older ones had already done the chores and even helped me with that too, as a nanny, because it was all on my own. (TEACHER 2, 2021).

The teachers were everything, they did a lot and with the little they had; support networks were limited, restricted, especially the communities to which they had some degree of belonging, whether as migrants, women, mothers, friends and holders of relevant knowledge, built not by chance, but from their enthusiasm and cunning about knowledge assessed as necessary for rural populations.

Final considerations

Rural schools in the Amazonian context, in the third quarter of the 20th century, from 1955 to 1971, were constituted from intense economic, political, social and cultural changes in Brazil.

On the one hand, they had the idea of development, filling the demographic gaps, the need to build schools; on the other hand, the inertia of public administrations on the process of subsidy and democratization of the school, mainly in rural areas.

We learned that rural teachers were lay teachers, worked in schools or multigrade classrooms with students in different age groups; children and young people, many of whom performed work activities with their families from the perspective of family farming in strips or plots of land distributed by military governments as an incentive to colonize the northern region of Brazil - state of Rondônia. This process generated a significant population increase from migration, between the 1950s and 1970s.

The work of children and young people in the fields caused distance from rural schools, infrequent students, but essential to produce foodstuffs on the lots where they lived and helped with planting and raising animals for subsistence.

The work activities of lay rural teachers did not present explicit links with the Rural Social Service, although the Ministry of Agriculture, in 1955, indicated the need for improvements in the provision of social services, in our case, rural education.

The characteristics of rural schools present approximations, precarious infrastructure, one-room schools, without drinking water and in places of difficult access. The Amazonian rural school is much more than the chaotic infrastructure generated by governments. The rural school is the result of several efforts, especially of the lay teachers themselves who became teachers throughout their practices and experiences as children students in other times.

The ways of teaching children and young people in rural schools correspond to one of the expertise of lay teachers who created, invented, insisted and taught in their own way. The teaching work was essential in view of the absence of adequate teaching materials and assistance from public administrations.

Due to the difficulties faced by rural teachers in their schools, they produced relevant educational actions in and for the realization of their classes; reorganized content and materials to help with their activities, taught children and young people to read and write. Rural teachers in the tense world of Brazil during the “years of lead” did a lot; they did everything in the schools they passed through, launched and established wisdom, and became more teachers over time, based on their own efforts. They spread dreams!

REFERENCES

ALENCAR, José F. de. A professora “leiga” um rosto de várias faces. In: THERRIEN, Jacques; DAMASCENO, Maria Nobre (coord.). Educação e escola no campo. Campinas: Papirus, 1993. p. 177-190. [ Links ]

ANTUNIASSI, Maria Helena Rocha. Trabalhador Infantil e escolarização no meio rural. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar editores, 1983. [ Links ]

BARROS, Josemir Almeida; et al. Memórias de professores e professoras rurais sobre o fazer docente em Rondônia, fins do século XX e início do XXI. Educa - Revista Multidisciplinar em Educação, Porto Velho, v.7, n.17, p.998-1024, jan./dez., 2020. Disponível em: https://periodicoscientificos.ufmt.br/ojs/index.php/educacaopublica/article/view/11754. Acesso em: 10 dez. de 2021. [ Links ]

BARROS, Josemir Almeida; FERREIRA, Nilce Vieira Campos. Pesquisa em História da Educação rural: professoras e professores entre teias e tessituras. In: CHALOBA, Rosa Fátima de Souza; CELESTE FILHO, Macioniro; MESQUITA, Ilka Miglio de (org.). História e memória da Educação Rural no Século XX. São Paulo: Cultura Acadêmica, 2020. p. 439-475. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto-lei nº 1.106, de 01 de jul. de 1970. Cria o Programa de Integração Nacional. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, DF, ano 25, n. 65, p. 2994-3026, 09 jul., 1970. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto-lei nº 5.812, de 13 de setembro de 1943. Cria os Territórios Federais do Amapá, do Rio Branco, do Guaporé, de Ponta Porã e do Iguassú. Diário Oficial da União - Seção 1 - 15 set., 1943. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE. Amazônia Legal, Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/cartas-e-mapas/mapas-regionais/15819-amazonia-legal.html?=&t=o-que-e. Acesso em: 11 dez. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei Complementar nº 41, de 22 de dez. de 1981. Cria o estado de Rondônia e da outras providencias. Diário Oficial da União, col. 1, 23 de dez., 1981. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 2.731, de 17 de fev. 1956. Muda a denominação do Território Federal do Guaporé para Território Federal de Rondônia. Diário Oficial da União, Seção 1 de 21 de fev. 1956. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 2613, de set. 1955. Autoriza a União a criar uma Fundação denominada Serviço Social Rural. Diário Oficial da União, 27 de set.,1955. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Educação como prática da liberdade. 25. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra S/A., 2001. [ Links ]

GALEANO, Eduardo. As palavras andantes. Porto Alegre: L&PM, 1994. [ Links ]

GHEDIN, Evandro; FRANCO, Maria Amélia Santoro. Questão de método na construção da pesquisa em educação. 2. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

GIBBS, Graham. Análise de dados qualitativos. Porto Alegre: Artemed, 2009. [ Links ]

HOLANDA, Sérgio Buarque de. O Brasil republicano: economia e cultura (1930-1964). 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil S.A., 1985. v.11. [ Links ]

ILLICH, Ivan. Um apelo à pesquisa em cultura escrita leiga. In: OLSON, David. R.; TORRANCE, Nancy (org.). Cultura escrita e oralidade. São Paulo: Ática, 1995. [ Links ]

LIMA, Abnael Machado de. Achegas para História da Educação no estado de Rondônia. 2. ed. Porto Velho: SEDUC, 1993. [ Links ]

LIMA, Sandra Cristina Fagundes de; ASSIS, Danielle Angélica de; GONÇALVES, Silvana de Jesus. “Inventores de trilhas nas selvas da racionalidade funcionalista”: professoras leigas e alunos das escolas rurais (Uberlândia-MG, 1950-1979). In: LIMA, Sandra Cristina Fagundes de; MUSIAL, Gilvanice Barbosa da Silva (org.). Histórias e memórias da escolarização das populações rurais: sujeitos, instituições, práticas, fontes e conflitos. São Paulo: Pacto, 2016. p. 199-233. [ Links ]

MACARINI, José Pedro. A política econômica do governo Médici: 1970-1973. Nova Economia [online]. 2005, v.15, n.3, p.53-92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-63512005000300003. [ Links ]

MATIAS, Juliana Cândido; BARROS, Josemir Almeida. As políticas sociais nos planos de governo dos presidenciáveis 2018 no Brasil e a mídia. Revista de Políticas Públicas, São Luís, v.23, n.1, p.339-355, 25 jul. 2019. Universidade Federal do Maranhão. Disponível em: http://www.periodicoseletronicos.ufma.br/index.php/rppublica/article/view/11923. Acesso em: 15 dez. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18764/2178-2865.v23n1p339-355 [ Links ]

NUNES, Marcia Jovani de Oliveira. Do professor leigo ao graduado no magistério rural: ações pedagógicas e processos formativos na transição do século XX para o XXI em Colorado do Oeste - RO. 2019. 211 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Curso de Pós-graduação em Educação Escolar: Mestrado e Doutorado Profissional, Universidade Federal de Rondônia - UNIR, Porto Velho, 2019. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Ovídio Amélio de. História, desenvolvimento e colonização do estado de Rondônia. Porto Velho: Dinâmica Ltda, 2001. [ Links ]

PEDLOWSKI, Marcos; DALE, Virginia; MATRICARDI, Eraldo. A criação de áreas protegidas e os limites da conservação ambiental em Rondônia. Ambiente & Sociedade [online]. 1999, n.5, p.93-107. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-753X1999000200008. Acesso em: 12 dez. 2021. [ Links ]

RICOEUR, Paul. A memória, a história, o esquecimento. Campinas: UNICAMP, 2007. [ Links ]

SCHELBAUER, Analete Regina; SOUZA, José Edimar de. Atuação docente no meio rural: cultura e práticas escolares. In: CHALOBA, Rosa Fátima de Souza; CELESTE FILHO, Macioniro; MESQUITA, Ilka Miglio de (org.). História e memória da Educação Rural no Século XX. São Paulo: Cultura Acadêmica, 2020. p. 363-398. [ Links ]

SILVA, Andressa Lima da. Infâncias da terra: histórias, memórias e suas repercussões na prática docente em escolas rurais de Ariquemes - RO. 2019. 202 f. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Curso de Pós-graduação em Educação Escolar: Mestrado e Doutorado Profissional, Universidade Federal de Rondônia - UNIR, Porto Velho, 2019. [ Links ]

SILVA, Maurício Ferreira da; BENEVIDES, Silvio César; PASSOS, Ana Quele da Silva. Impeachment ou golpe? Análise do processo de destituição de Dilma Rousseff e dos desdobramentos para a democracia brasileira. In: Congresso Latino-Americano de Ciência Politica, 9., 2017, Montevidéu. [Trabalhos apresentados]. Montevidéu: ALACIP, 2017. p. 1-22. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, Paul. A voz do passado: história oral. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1992. [ Links ]

VENTURA, Zuenir. 1968 o ano que não terminou. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1988. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

PROFESSORA 1. COSTA, Maria Clara Villar da. [81 anos]. [set. 2021]. Entrevistador e entrevistadoras: Josemir Almeida Barros; Marcia Jovani de Oliveira Nunes e Andressa Lima da Silva. Porto Velho, RO, 03 set. 2021. Google Meet, 74 min. [ Links ]

PROFESSORA 2. SILVA, Luizene Moreira. [68 anos]. [set. 2021]. Entrevistador e entrevistadoras: Josemir Almeida Barros; Marcia Jovani de Oliveira Nunes e Andressa Lima da Silva. Porto Velho, RO, 24 set. 2021. Google Meet, 52 min. [ Links ]

PROFESSORA 3. SILVA, Francisca Araújo da. [62 anos]. [set. 2021]. Entrevistador e entrevistadoras: Josemir Almeida Barros; Marcia Jovani de Oliveira Nunes e Andressa Lima da Silva. Porto Velho, RO, 08 set. 2021. Google Meet, 49 min. [ Links ]

Received: July 11, 2022; Accepted: September 26, 2022

texto en

texto en