Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-204

Dossiê 4 - Visões e práticas da educação como ferramentas transformativas

The New Education Fellowship and South America: a panorama of the establishment of networks (1920-1930)1

1Universidade de São Paulo (Brasil). Bolsista de Produtividade em Pesquisa (Nível 1A). dvidal@usp.br

2Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (Brasil). rafaelasilvarabelo@hotmail.com

3Universidade Federal Fluminense (Brasil). vinimoncaodois@gmail.com

The New Education Fellowship (NEF) is a subject matter widely examined by historiography of education, considering its conferences, as presented by Brehony in his best-known article, or related to educators and networks established in different countries, as addressed by Middleton, Haenggeli-Jenni, Watras, and others. However, this historiography is markedly limited to Europe, with some advances into Oceania and North America. With the aim of filling a gap in regard to the processes of establishment of networks between the NEF and South America, we intend to draw up a historical panorama of the initial years of creation of the NEF, from 1920-1930, taking the conference that occurred in Locarno, Switzerland, in 1927 as the inflection point. To review these networks in South America, the main sources are correspondence exchanged by South American educators, reports of conferences, and the journals The New Era and Pour l’Ére Nouvelle.

Keywords: Transnational history of education; New School; Networks

A New Education Fellowship é um objeto amplamente visitado pela historiografia da educação, considerando seus congressos, como apresentado por Brehony em seu artigo mais conhecido, ou relacionada a educadores e redes estabelecidas em diferentes países, como endereçado por Middleton; Haenggeli-Jenni; Watras, dentre outros. No entanto, esta historiografia está marcadamente circunscrita à Europa, com algumas incursões acerca da Oceania e América do Norte. Com o propósito de preencher uma lacuna no que se refere aos processos de constituição de redes entre a NEF e a América do Sul, pretendemos desenhar um panorama histórico compreendido nos anos iniciais da criação da NEF, entre 1920 e 1930, tomando o Congresso, ocorrido em Locarno, na Suíça, em 1927, como ponto de inflexão. Para retraçar essas redes na América do Sul, as principais fontes são correspondências trocadas por educadores sul-americanos, relatórios dos congressos e as revistas The New Era e Pour l’Ére Nouvelle.

Palavras-chave: História transnacional da educação; Escola nova; Redes

La New Education Fellowship est un objet largement visité dans l'historiographie de l'éducation, pour l'intérêt suscité par ses congrès, comment présentée par Brehony dans son article le plus connu, ou liée aux éducateurs et aux réseaux établis dans différents pays, qui sont abordés dans les travaux de Middleton; Haenggeli-Jenni; Watras et autres.. On perçoit néanmoins que cette historiographie est nettement circonscrite en Europe, certains ouvrages se référant et à l’Océanie, et à l’Amérique du Nord. Nous proposons donc de créer un panorama historique permettant de comprendre le processus impliqué dans la formation de réseaux entre la NEF et l’Amérique du Sud dans les années 1920 et 1930, ayant comme point de repère le fameux congrès de la NEF à Locarno en 1927. Afin de reconstituer ces réseaux en Amérique du Sud, nos principales sources comprendront la correspondance entre les éducateurs sud-américains, les comptes rendus des congrès et les revuesThe New Era et Pour l’Ère Nouvelle.

Mots clés: Histoire transnationale de l’éducation; Nouvelle education; Réseaux

La New Education Fellowship ha sido objeto muy estudado por la historiografía de la educación, con respecto a son congresos, como la discusión presentada por Brehony en um articulo muy conocido, o en relación a educadores y redes establecidas en diferentes países, tema tratado por Middleton, Haenggeli-Jenni, Watras, y otros. Aún así, podemos percibir que la historiografía está circunscrita de manera marcada a Europa con algunos trabajos referidos a Oceanía y Norte-América. En este sentido, nuestro propósito es crear un panorama que haga posible entender los procesos de constitución de redes entre NEF y América del Sur, en los años veinte y treinta, usando como hito la Conference de NEF in Locarno en 1927. Para trazar estas redes en América del Sur, consultamos los intercambios de correspondencia entre los educadores de América del Sur, los Informes de la Conferencia, y las revistas The New Era y Pour l’Ère Nouvelle.

Palabras claves: Historia transnacional de la educación; Nueva educación; Redes

The New Education Fellowship (NEF), also known as the Ligue Internationale pour l'Éducation Nouvelle, is a subject matter widely examined by historiography of education, considering its conferences, as discussed by Brehony2 in his best-known article, or related to educators and networks established in different countries, as addressed by studies of Middleton3, Haenggeli-Jenni4, Watras5, and others. However, this historiography is markedly limited to Europe, with some advances into Oceania and North America. With the aim of filling a gap in regard to the processes of establishment of networks between the NEF and South America, we intend to draw up a historical panorama of the initial years of creation of the NEF, from 1920-1930, taking the conference that occurred in Locarno, Switzerland, in 1927 as the inflection point.

The choice of the Locarno Conference is not fortuitous. Although the NEF arose in 1921 as a result of the Calais Conference in France, and it organized two other conferences before 1927 - in Montreux, Switzerland, in 1923 and Heidelberg, Germany, in 1925 - it was only in Locarno that we find the attendance of educators coming from South America. In the records of The New Era (TNE), there is information of representation from Brazil, Peru, and Uruguay. Pour l’Ére Nouvelle (PEN) adds the participation of Argentina in the same event. The only names mentioned by the periodicals, however, were Laura Jacobina Lacombe6 for Brazil and Clotilde Guillen de Rezzano, Antonio Sagarna, and Pascual Guaglianone for Argentina. There is no news of others.

From that time on, the participation of South America emerges, even if on an ad hoc basis, in the subsequent conferences of Elsinore, Denmark, in 1929 and Nice, France, in 1932, when Chile and Argentina were represented in the former and Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Uruguay in the latter. We must not fail to consider that the greater presence in Nice may be related to the trip undertaken by Adolphe Ferrière to Portugal, Spain, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil7 from April to October 1930. After all, according to Joseph Coquoz, a strategic plan had already been developed in 1921 defining areas of activity of the three main founders of the NEF: Ferrière would be in charge of disseminating the Fellowship among Latin language countries, Beatrice Ensor would care for English speaking countries, and Elisabeth Rotten would care for Germanic language countries8.

In fact, the Locarno Conference and the intermediation of Ferrière seem to have been decisive events in the incorporation of South American educators in the NEF. It is not a coincidence that the first references to branches in South America began to appear in TNE in 1927, with journals from Argentina (Nueva Era, edited by José Rezzano) and Chile (La Nueva Era, edited by Armando Hamel) provisionally affiliated with the Fellowship9. However, according to Coquoz, Ferrière was dissatisfied with the small participation of the Latin educators in the Locarno and Elsinore conferences. The trip to South America thus arose as an opportunity to increase the engagement of the region in the NEF, and it had immediate repercussions. Outside of Argentina, which had created its branch in 1928, Ecuador and Peru joined the Fellowship in 1930, Chile in 1931, and Paraguay and Uruguay in 1932. The branches in Bolivia in 1936 and Brazil in 1942, however, were more delayed10.

Reviewing the establishment of the networks that connected South American educators to the NEF is the main objective of this article. For that purpose, we made use of the exchange of correspondence, reports of conferences, and texts published in The New Era and Pour l’Ére Nouvelle. The discussion is based on the perspective of transnational history of education11, which considers that the social and historical processes cannot be grasped within the conventional borders of states, nations, empires, or regions. In contrast, it highlights the relevance of the interactions and of the circulation of subjects and ideas beyond geographic borders, prompting the use of tools of network theory12 and of digital history.

The network approach has been quite valuable for the transnational perspective in that which provides visibility to individual and collective agency. We start from the premise that the NEF constituted a hub. Hubs consist of nodes with various connections; therefore, they are not initial or final points, but points of contact; that is, they are not a condition or result, but a convergence. Nodes, in turn, can designate individuals, groups, corporations, or any type of collective13. That way, we are suspicious of analyses that use the center-periphery dichotomy model of cultural transfer, preferring to consider the exchanges as pervaded with appropriations and produced in multiple directions. Digital history, for its part, offers the possibility of consulting and processing digital files and mass documentation, such as the collections of periodicals taken here as a source. We adopted ATLAS.Ti, a qualitative data analysis program (CAQDAS) for treating digital or digitized documentation.

To manifest the course of our discussion, we have structured the text in three parts that complement this introduction and the conclusion. In the first part, we focus specifically on the Locarno Conference, describing its organization and the South American participation. In the second, we trace the movements prior to the event, the contacts of members of the NEF with South American educators, for the purpose of presenting some webs of connections that culminated in the presence of the region in 1927 in Switzerland. In the third part are the repercussions in subsequent conferences, the creation of branches, and the affiliation of journals, which spurs writing.

1. The Locarno Conference and South American participation

According to Béatrice Haenggeli-Jenni14, the period from 1927 to 1930 constitutes the “golden age” of the NEF. Until then, the author argues, the Fellowship did not have a body of rules, functioning more as a federation than a true association. Nevertheless, the rapid growth of the capillarity of the NEF had led to the creation of an international committee in 1925, formed of representatives from England (B. Ensor), Germany (E. Rotten), Belgium (O. Decroly), Bulgaria (dr. Katzaroff), Hungary (M. Nemes), Scotland (G. Krutwell), Denmark (S. Naessgard), Italy (G. Lombardo-Radice), France (J. Hauser), Spain (L. Luzuriaga), and Switzerland (A. Ferrière). It replaced the executive committee, previously composed of Ensor, Ferrière, Rotten, and Baillie-Weaver, the last, resigning in 1925, had given his place over to George S. Arundale.

It was actually during the Locarno Conference that the international committee decided to better organize the structure of the NEF, defining the conditions of affiliation for branches and journals, which included the payment of a financial contribution to the Fellowship. This decision was driven by the expansion in the number of participants in the event. In 1927, 42 countries were represented, with attendance of approximately 1200 people. The numbers were in contrast with past events. In Calais, there had been only 150 participants; in Montreaux, 300; in Heidelberg, 45015. Locarno, therefore, nearly tripled the number of the previous conference that occurred in 1925.

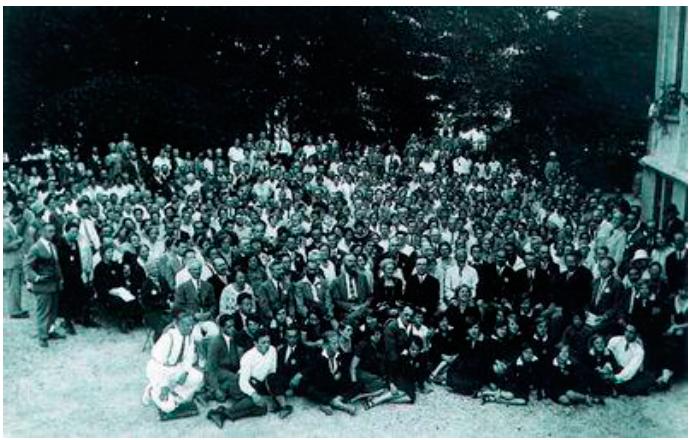

The IV World Conference on New Education with the theme “Freedom in education”, which took place from August 3-15, 1927, was considered a great success. A photograph, published both in the initial pages of PEN16 and of TNE17, served as evidence.

Source: Phototheque UNIGE - Archives Institut Jean Jacques Rousseau. Retrieved from: https://phototheque.unige.ch/aijjr/unige:34162. Accessed on Aug. 8, 2022.

Figure 1

Indeed, issues 31 and 32 of PEN of September, October, and November 1927 and issue 32 of TNE of October of the same year were wholly dedicated to disseminating news and conferences offered at the event. In the list of the conference participants published by TNE, only Ad. Ferrière for Argentina and Laura Lacombe for the Brazilian government and Brazilian Education Association appear as representatives of South America. In the table of contents of PEN18, however, we also locate reference to Clotilde Guillen de Rezzano, an Argentinian educator who signed the text “Rèpublique Argentine: un essai pour rendre possible l’autonomie de l’écolier dans les écoles d’Etat”, as well as Lacombe, author of “Brésil: L'enseignement public à Rio de Janeiro”. Both were part of the section called “La participation des Pays Latins” in PEN. The complete texts published in PEN, however, appeared in summary form in TNE, which, moreover, reported that they were the communication of Guillen de Rezzano read by Ferrière, with the assistance of the Minister of Public Instruction of Argentina, Antonio Sagarna, and of the Inspector General, Pascual Guaglianone, of the Escola Normal no. 5 of Buenos Aires; and that in the presentation of Lacombe, a film portraying education in Rio de Janeiro had been shown, with special emphasis on the health of the students through sun baths and open air classes19. The same edition of TNE also recorded participation of two more delegates from Brazil, one from Uruguay, and one more from Peru in the Locarno Conference, without, however, providing greater details20.

The publishing strategies of the two journals denote the differentiated emphasis given to the representatives of South America. Certainly, as editor of PEN and the one responsible for dissemination of NEF in Latin America, Ferrière gave greater emphasis to communications from the region, even acting as the spokesperson of the Argentinian educator. In turn, Beatrice Ensor, editor of TNE and charged with propagating the Fellowship among English-speaking countries, attributed greater relevance to European, North American, and Australian educators. Whereas in PEN, one notes interest in recording all the presentations made in the Conference - a chronicle of the event, as asserted in the editorial Avis de la rédaction21 - in TNE, we find only a selection. Perhaps the frequency of the two journals did not allow the same exposition. PEN was practically monthly in 1927 (the only months combined were July-August and September-October), whereas TNE was quarterly, with editions in January, April, July, and October. Furthermore, the evaluation of Ensor regarding Latin participation may have led to the different publishing treatment.

In the section “The Outlook Tower”, which leads off each issue of TNE as an editorial, we find the following manifestation: “The Latin races were thinly represented, and it was a great disappointment that political difficulties prevented many Italians from participating. The French-speaking group was composed of members from many parts of the globe.”22

The two South American communications published in full by PEN approach education in Brazil and in Argentina from different angles. Laura Lacombe, through showing the film produced by the Board of Public Instruction of Rio de Janeiro, addressed three aspects: health in school, teaching in school, and social action in school. Guillen de Rezzano, in contrast, stuck to the central theme of the event, discussing the relationship between the school regimen and the principle of liberty.

In regard to the presentation of Lacombe, the educator sought to offer a panorama of public education in Rio de Janeiro, highlighting the initiatives of the Antonio Carneiro Leão administration. Regarding the first aspect, she discussed programs such as school soup and cup of milk and actions such as services of school clinics, dental offices, and the Red Cross to students. In addition, she reported the establishment of an open-air school in Jacarepaguá for “frail” children. Physical education, manual labors, the sloyd technique, the active methods used in the study of geography and agriculture, open-air classes, access to school libraries, mental tests for uniformity of the classes, vocational guidance, and the teaching of home economics were some of the topics included in the second aspect. For the third, she selected the work of the Mothers’ Circle, Parents’ Association, and Youth Red Cross, as well as efforts of the administration and of teachers in developing international solidarity and fraternity among students23.

As for Guillen de Rezzano, the discussion aimed at entering into the difficulties faced by proponents of the new school to ensure child autonomy within school processes. To do so, she made use of an experience carried out in the Normal School no. 5 of Buenos Aires, in which she was the principal, with students from 6 to 9 years of age. The text, however, only announced its purpose, because the author referred to the booklet made available to the conference participants in which the presentation was accompanied by photographs that had been published in the periodical Nueva Era24, “organo de la sección argentina de la Liga internacional de la nueva educación”, edited by José Rezzano, Clotilde’s husband.

The highlight given by PEN and by its editor to Laura Lacombe and Clotilde Guillen de Rezzano was not by chance. After all, Guillen de Rezzano had not even been present at the Conference, and Lacombe may have been accompanied by two other Brazilians, since the list of participants published by TNE25 indicated 3 delegates from Brazil. The difference arose from the previous contacts made by the two educators with Ad. Ferrière, the Jean Jacques Rousseau Institute (JJRI), and other names associated with educational renewal in the period. Teasing out the threads that wove these webs of connections is the purpose of the next section.

2. Recovering the threads: the constitution of networks prior to the Locarno Conference

Though the records found confirm the South American presence in the NEF conferences only in 1927, there is a network of connections that is constituted in previous years that begins to prepare the stage for these educators coming from the republics from the other side of the Atlantic. The spread of the NEF through different countries, associating new members and circulating their discussions, occurred in different manners. The conferences were only one of these strategies. The mobilization itself for participation in the conferences made use of mechanisms that sustained and expanded the international networks of educators, of which we can cite the study missions carried out by NEF members in different continents, the circulation of official journals, and even educators from different countries passing through the hubs of teacher formation, such as the JJRI in Switzerland and the Teachers College at Columbia University in the USA.

Taking the Locarno Conference as a point of departure for this article, we now draw the threads of the names of the South Americans that are credited in it, beginning with the Brazilian Laura Lacombe. Her participation in the Locarno Conference came following contacts with European educators, which culminated in her going to Europe in 1925 to study in the JJRI. During her attendance at the institution, she came to know educators linked to the NEF, namely, Bovet, Claparède, and Ferrière, with whom she maintained correspondence in the following years.26

Another name cited in the conference was that of Clotilde Rezzano. The fact that her report had been read by Ferrière27 confirms that dialogue had previously been established. Clotilde Guillen de Rezzano was a name known from a group linked to the new education movement in Argentina, generally cited in the historiography through the the action of group members in the dissemination and experimentation of new pedagogical ideas, such as the centers of interest of Decroly. It should be noted that Clotilde went to Europe in 1906 on a study mission to observe the organization of schools.28

Among the Argentinian educators aligned with the new educational ideas was her husband, José Rezzano, editor of the journal La Obra. Founded in 1921, La Obra gathered a group of collaborators that converged in defense of pedagogical innovations. In 1926, the journal made its adherence to the NEF official through publication of the newly created supplement under the title Nueva Era, which, as of 1927, began to be edited in an independent manner also under the direction of José Rezzano29. References to the Nueva Era emerge in the TNE as affiliated with the NEF only in 192730, but they appear in PEN since 192631.

In its first issue dated July 1926, the supplement showed in the header that it was linked with the “Liga para la Educación Nueva” and a little below, the inaugural issue opened with a letter addressed to Pierre Bovet, director of the International Bureau of Education (IBE). The letter discussed the importance of the journal La Obra, its support for the newly created IBE, the launch of Nueva Era, and its alignment with the Fellowship. Its penultimate paragraph best clarifies how these connections were perceived by the editor.

La Obra, which has dedicated itself in recent times to tirelessly and eagerly disseminating the most recent desires and attempts of an educational nature in the old countries of Europe and in the United States, reveals the deep concern it has for such matters, inaugurating a special section in its pages as of today, called "Nueva Era". Its sole purpose is to divulge the current state of the world in school matters, especially analyzing that which refers to the movement that unifies the "International New Education Fellowship”, with the most absolute conviction of the truth that the founders of the “Bureau” hold when they think that only a new, generous, and broad mentality will fight the good fight against the forces of evil that seem to dominate the world today, and that this new mentality is only possible with a new education.32

The second issue of the supplement, published in August of the same year, also began with a text regarding the Fellowship, under the title “Our adherence to the ‘International New Education Fellowship’”. It is also through Nueva Era that we have access to details of Maria Montessori’s visit to Argentina in 1926. The first mention of the trip appears in issue 5, dated September, which contains articles discussing the Montessori method and describing the courses offered by the Italian educator during her stay. References to the courses extend through the following two issues (of October 5 and 20), closing with the news of the return of Montessori to Europe.33 The presence of Maria Montessori in Argentina in 1926 constitutes an important element of the web of connections that precede the Conference of 1927, considering that she was a figure close to Beatrice Ensor and that, especially in the first years of the NEF, the Montessori method and its proponents had a marked presence in the events and in the journal TNE34.

In the issue after Montessori’s departure, the first text of the supplement reports on the Locarno Conference of the NEF. Under the title “The next Conference of the International New Education Fellowship”, it begins with the following paragraph:

We have just learned that the next conference of the New Education Fellowship is to be held in Locarno, famous in the diplomatic annals of recent times, during the first two weeks of August 1927. As our readers are aware, the previous meetings - which are held every two years - took place in Calais, Montreux, and Heidelberg35.

In addition to information on possible participants at the event, the text also presents concern that the Argentinian educational experiences and innovations be reported at the conference, though not explicitly indicating possible representatives.

If in pulling up the name Clotilde Rezzano we arrived at the supplement Nueva Era, it is still in the trail of pedagogical printed matter that we proceed with the discussion, since another way of mapping these networks is analyzing the official journals of the NEF, specifically Pour l’Ere Nouvelle, which is more representative of the dialogue in Latin language countries. Edited by Adolphe Ferrière, PEN provides a glimpse of the contacts established by members of the NEF - specifically Ferrière himself - with South American educators, as well as circulation of the journal itself in different countries.

Upon mapping references to South America in the journal, the term appears for the first time in April 1922 in the editorial section36. In 1923, also in the editorial section, Ferrière refers to attempts at contacts with editors of other journals, citing Uruguay, but without providing details.37 In April 1924, he mentions Brazil. These first indicators found in PEN allow us to trace other connections. Through them, we learn of the correspondence established with the Brazilian educator Carneiro Leão38.

In the collection of Antônio Carneiro Leão, under the safekeeping of the Brazilian National Library, is the response letter of Ferrière, dated March 28, 1924, which mentions original correspondence from Carneiro Leão written in February. Analyzing both the letter from Ferrière regarding the information on education in Rio de Janeiro that he introduces in the editorial of PEN, we conclude that Carneiro Leão entered in contact with Ferrière after discovering the periodical. It was also Carneiro Leão that encouraged Laura Lacombe to go to the JJRI in 1925. Lacombe would come to be the first official representative of Brazil in a conference of NEF in 1927. And, upon attending the event in Locarno, she had images of the Carneiro Leão administration in Rio de Janeiro exhibited39.

Beyond the quick mentions, the first more substantial notes on South America appear in the July 1925 issue, regarding Colombia and Uruguay, within the text under the title “Écoles expérimenteles em Europe et en Amérique”, written by Ferrière.40 In the note on Colombia, dedicated specifically to the activity of Nieto Caballero heading the Gimnasio Moderno, Ferrière refers to him as a “former student of the JJRI”, who had given a lecture in that institution in April. The note on Uruguay reproduces information of a letter sent by Salas Olaizola about a journal published at the Las Piedras school, of which he was the director, and initiatives directed to educational renewal in Uruguay.

Other notes on South American education, once more on Colombia and Uruguay, are published in the issue of January 1926.41 Regarding Uruguay, it once more reproduces segments of a letter sent by Sabas Olaizola, who is ready to send copies of the journal published in his school, and refers to other initiatives. In the note on Colombia, it mentions the presence of Decroly in that country and that he would send an article reporting his experience to PEN. The article cited is published in two parts in the two following issues of the journal (March and April) under the title: "Une école nouvelle en Amerique du sud. Le Gymnase moderne Bogota (Colombie)"42.

Regarding Sabas Olaizola (1894-1974), we have little information on the contacts that bring him close to NEF and to Ferrière in the 1920s beyond the correspondence mentioned in PEN itself. In addition to being a reference in the renewal movement in Uruguay and later in Venezuela, we know that in 1927, Olaizola was on a mission in Belgium and Switzerland and that he met Ferrière during his stay.43 As already mentioned, the Locarno conference had a representative from Uruguay, and although his name does not appear in TNE or PEN, from the sequence of dates, it is reasonable to presume that Olaizola was the participant.

Returning to the article of Decroly on Colombia, we find that he discusses innovative experiences, focusing specifically on the Gimnasio Moderno in Bogotá and on the activity of its founder, Nieto Caballero. Moreover, he highlights the international training of the Colombian educator, his trips through Europe and the United States, including previous contacts with the JJRI in the 1910s and the journey through the South American republics from 1924 to 1925. Finally, he mentions the presence of a student of Montessori in Colombia in 1917.

As can be perceived in the references to South America in PEN, all the notes on Colombia in the 1920s refer to Nieto Caballero, an indication of the importance he would assume in later years as Latin representative in the NEF. Although his name does not appear in the Locarno Conference, he would attend later conferences, acting even as one of the main speakers at the Cheltenham Conference in 193644. Taking Decroly’s article as a reference, the connection made between the Gimnasio Moderno (a rural school for boys inspired by the Decroly and Montessori methods that became an international emblem of pedagogical renewal and symbol of the new school movement in Colombia) and Nieto Caballero necessarily passes through the international movement of the educator.

The history of activity of Agustin Nieto Caballero is full of travels from the time of his youth. In 1904, he set off to Europe with his brothers and then went to New York where he finished his studies. In 1910, he entered Teachers College at Columbia University and, following that, he went to Europe, where he studied Law and Pedagogy in France. In that period, he came in contact with discussions regarding new education. He returned to Colombia in 1913, and in the following year he led an initiative that resulted in establishment of the Gimnasio Moderno. Among his comings and goings through different countries and institutions, we find the presence of Nieto Caballero in Rio de Janeiro in 1925, and his discussions with the Brazilian Education Association, of which Carneiro Leão was part.45

But the presence of Nieto Caballero in the JJRI in the 1920s and his return in 1925 that would motivate Decroly to go to Colombia, spotlights not only the role of circulation of the journal PEN, but also the role that the presence of South American students in the JJRI (and as of 1925 in the IBE) played in the spread of the NEF, or better, of the Ligue Internationale pour l’Education Nouvelle. Another example cited well at the beginning of this topic was that of the Brazilian Laura Lacombe, whose presence in the JJRI preceded her going to the Locarno Conference.

The web of connections that were established over the 1920s and culminated in the participation of South Americans in the Locarno Conference achieved dimensions that in the following years were manifested in the presence of delegations in the NEF conferences and in the creation of affiliated groups, as presented in the following topic.

3. Following the trail of the weaving of networks

In seeking to locate the subjects, institutions, and actions that make up the global network of the NEF after the Locarno Conference, we focus our attention on the journals TNE and PEN, so as to identify which aspects of the South American context were considered in the pages of the periodicals. That way, we also activate here the notion of hub, understanding the two main journals of the Fellowship as a large connecting node of information and reports of the educational experiences carried out in different locations.

Nevertheless, expansion of the documental mass coming from the very densification of the network constituted by the NEF after 1927 in its “golden age” led us to get tools for qualitative surveying and processing of large volumes of data, bringing us closer to the debates on digital history. Before examining the findings from research, some theoretical-methodological considerations on this advance need to be made.

Invoking the metaphor of the craftwork process of weaving threads, the treatment given the digitized files requires similar attention. The digitized files first need to be handled so that the tools of CAQDAS are useful for analyses. Both journals passed though digitization processes and are available to the public free of charge46. However, each one has specific characteristics.

The lack of OCR results in the need to carry out only human reading of the material, impeding the use of CAQDAS and the operations it offers in a more extensive way. For example, for the codification process, we can make use of the “text research” tool in the entire collection and it presents the results found. From there on, performing analyses becomes more agile and practical; otherwise, it is necessary to read all the material, which from the perspective of the extent of the content of the two collections, becomes unviable.

Every OCR process requires that the digitized file was captured with good image resolution, pages in order, and correct positioning, as well as other properties indispensable for production of a good file. A digitized image of low quality, out of focus, or with noise that impedes reading makes the use of CAQDAS impracticable in the text search process. In TNE, little noise was identified, but in PEN, noise was greater, such as to require treatment in the quality of the image, correction of pages that were upside-down, and various scans by human reading to identify ways of minimizing difficulties.

After the process of adjustment of the digitized file of PEN to run in ATLAS.Ti in a satisfactory way, we began the process of code clustering. We proceeded to close reading and general reading of the digitized collection of TNE and of PEN which, in the 1920s and 1930s, published 138 and 151 issues, respectively. For construction of the cluster, in both journals, we chose the names of countries, cities, persons, and institutions as codes, with the understanding that such nodes could lead us to other nodes and thus to the constitution of networks. The terms used for codification were adopted through having been identified during contact with the sources and historiography we had handled during research. Furthermore, for the codification process, it was necessary to take the differentiated content published by each one of the periodicals and their languages into consideration. Among the codes collected, some remarks can be made considering the table below:

Table 1 Codes and magnitudes of occurrences in the TNE and PEN journals (1920-1930)

| Code | TNE | PEN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnitude | Order | Proportion | Magnitude | Order | Proportion | |

| Agustín Nieto Caballero | 5 | 11th | 2.7% | 15 | 10th | 3.5% |

| Argentina | 30 | 1st | 16.3% | 43 | 3rd | 10.1% |

| Armando Hamel | 11 | 7th | 6.0% | 24 | 4th | 5.7% |

| Assunção | 1 | 20th | 0.5% | 0 | - | - |

| Bolivia | 3 | 12th | 1.6% | 21 | 6th | 5.0% |

| Brazil | 12 | 5th | 6.5% | 14 | 11th | 3.3% |

| Buenos Aires | 17 | 4th | 9.2% | 17 | 9th | 4.0% |

| Chile | 22 | 2nd | 12.0% | 75 | 1st | 17.7% |

| Clotilde Rezzano | 3 | 12th | 1.6% | 3 | 22nd | 0.7% |

| Colombia | 20 | 3rd | 10.9% | 44 | 2nd | 10.4% |

| Ecuador | 1 | 20th | 0.5% | 1 | 25th | 0.2% |

| Espírito Santo | 1 | 20th | 0.5% | 1 | 25th | 0.2% |

| Fernando de Azevedo | 0 | - | - | 5 | 20th | 1.2% |

| Gimnasio Moderno de Bogotá | 1 | 20th | 0.5% | 13 | 13th | 3.1% |

| Guayaquil | 0 | - | - | 1 | 25th | 0.2% |

| J. B. Fonseca | 0 | - | - | 1 | 25th | 0.2% |

| Jose Rezzano | 12 | 5th | 6.5% | 14 | 11th | 3.3% |

| Laura Lacombe | 3 | 12th | 1.6% | 6 | 19th | 1.4% |

| Lourenço Filho | 1 | 20th | 0.5% | 0 | - | - |

| M. L. Pons | 1 | 20th | 0.5% | 0 | - | - |

| Montevideo | 2 | 18th | 1.1% | 18 | 8th | 4.2% |

| Paraguai | 3 | 12th | 1.6% | 12 | 15th | 2.8% |

| Peru | 8 | 9th | 4.3% | 11 | 16th | 2.6% |

| Quito | 0 | - | - | 9 | 18th | 2.1% |

| Ramon Cardozo | 2 | 18th | 1.1% | 3 | 22nd | 0.7% |

| Rio de Janeiro | 3 | 12th | 1.6% | 13 | 13th | 3.1% |

| Santiago | 0 | - | - | 10 | 17th | 2.4% |

| São José dos Campos | 0 | - | - | 1 | 25th | 0.2% |

| São Paulo | 0 | - | - | 4 | 21st | 0.9% |

| Universidade de La Plata | 3 | 12th | 1.6% | 3 | 22nd | 0.7% |

| Uruguai | 7 | 10th | 3.8% | 20 | 7th | 4.7% |

| Valparaiso | 11 | 7th | 6.0% | 22 | 5th | 5.2% |

| Venezuela | 1 | 20th | 0.5% | 0 | - | - |

| Total | 184 | - | 100.0% | 424 | - | 100.0% |

The table presents the labeled codes. The “magnitude” refers to the number of times that the code was identified in the body of the journals in absolute number48. The “order” indicates the placement of the code in decreasing perspective, according to magnitude. The proportion is the individual frequency considering the total magnitude of the codes in each journal.

As expected, the PEN shows greater frequency (magnitude of 424) of citations to the South American context than the English journal (magnitude of 184), and among them, the codes Argentina, Colombia, and Chile occupy the first three places in the degree of occurrence in both journals. For Argentina and Chile, we understand that the magnitude is associated with the recurring presence of the name of the journals La Obra49 (and its supplement Nueva Era) and La Nueva Era in the editions of TNE and of PEN when they came to be part of the international network of periodicals as of 1927. In the same way, the names of the editors José Rezzano (of Argentina), Agustín Nieto Caballero (of Colombia), and Armando Hamel (of Chile) appear among the persons most cited among those codified.

Among the educational institutions, we identified references to the Universidade de La Plata and to the Gimnasio Moderno de Bogotá. Mention of the Universidade de La Plata, though of low magnitude in both journals, indicates possible proximity between the proposals of new education and teacher training on a university level, to which the professional activity of the editor Jose Rezzano, professor of Educational Sciences at the institution, is associated. In regard to the Gimnasio Moderno de Bogotá, the references stem from the activity of Nieto Caballero in the secondary school that, as said before, became a model for implementation of new school principles, showing considerable frequency (magnitude of 13) in PEN.50

The code “Brazil” occupies 5th position in TNE and 11th in PEN in an overview of the percent of magnitude of occurrence of the codes, showing a difference of 3.2%. However, there are other indications that can be identified in TNE and in PEN that allow us to visualize circulations, appropriations, and participation of the country in the new education scenario without necessarily being officially inserted in the international network. For example, one can point to the information of purchase and distribution of movie projectors for the normal schools and secondary schools in Espírito Santo51, as well as the article published in PEN entitled “Une tâche sociale urgente: la transformation des Ecoles Normales au Brésil”, written by J. B. Fonseca, teacher of the Normal School of São José dos Campos in the state of São Paulo52. Such information allows us to shift the axis of analysis from the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, enabling a glimpse of integration of other locations overlooked by historiography of education in the international discussion regarding the new school.

The connections between NEF and South America include the trips made by members of the network to the region, members such as Decroly, Ferrière, and Montessori, already mentioned, that induce us to think of the establishment of connections through pedagogical missions of an institutional nature headed up by members of the Fellowship in their endeavor to get to know the South American reality and draw near South American educators.

Working with the reports of the conferences of 1929 and 1932, in the issues dedicated to the meetings of Elsinore and Nice, we sought indications of South American presence, even though the information in general is brief news and comments. At the Elsinore Conference, 1746 members of the NEF were present, coming from 43 countries, among which only Chile and Argentina appeared as representatives of South America. The two countries accounted for 6 participants, without identification of all their names. Yet, in a partial listing of the delegates of the national groups published by the journal is a reference to the representative of the Chilean government “M. E. Salas” and to “Mlle. M. L. Pons” for Uruguay.53

Of these representatives, only the report produced by M. E. Salas was published. According to the editorial of TNE, the reports published were selected by the editor of the journal among the countries that had undertaken important educational reforms in the past decade54.

Our hypothesis is that “Salas” is Darío Enrique Salas Díaz (1881-1941), a Chilean educator involved with educational projects of new education and teacher training in his country. According to Neumann55, Salas Díaz obtained a doctorate at New York University during his stay in the United States, and after returning to Chile, he came to act as professor at the Pedagogical Institute of the Universidad de Santiago56. During his stay in New York, like Caballero, Salas Diaz had close contact with Dewey and other educators of the Teachers College at Columbia University.

The report published in TNE refers to the efforts made for advances in schooling undertaken by the Chilean government, such as increase in literacy rates, reorganization of education, and financial investments. Regarding Pons, no further information was found.

In August 1932, the 6th NEF conference took place in Nice, France. There were nearly the same number of participants at this event as at Elsinore. Unlike the coverage given by TNE to the previous conference, the themes discussed at this conference were more publicized, without the concern of reporting the composition of the delegates in greater detail. Only two reports were published in the English journal, elaborated by the Japanese commission and by the Chinese commission57.

However, in issue no. 6, before the conference was held, in the section of international notes, information was published regarding the registrations that the conference commission had received. The note reports participants from various countries, especially from Europe and from the United States, such as Jean Piaget, Maria Montessori, Ovide Decroly, Paul Langevin, Henri Wallon, and Carleton Washburne. Outside of this geographical sectioning is the name of Lourenço Filho, as director of Public Instruction in Brazil58.

Four years after the conference of 1932, the meeting occurred in Cheltenham, closing the two decades of international conferences of the NEF. In that conference, as already mentioned, we identify the participation of Nieto Caballero in the role of one of its main speakers. The lecture he gave, entitled “Le renouvellement d’un peuple par l’éduction” was published in PEN in 193759. For the first time, a South American educator achieved such prominence in an event of the NEF. The international circuit he had traveled since youth, the contacts established on both sides of the Atlantic with members of the NEF, his attendance at institutions such as JJRI and the Teachers College at Columbia University, the importance assumed by the Gimnasio Moderno as an emblem of the new school in Colombia, the visits to the South American country made by Ferrière and Decroly, as well as the proficiency of Nieto Caballero in various languages are elements that compose the web of accreditation of his invitation as conference speaker in 1936. We clearly perceive the strategies mobilized by members of the network in consolidation of ties and in tightening nodes, articulating large scale movements, national or international, with more local and individual actions. These strategies serve as indications in analyzing the principles of governance placed in operation in the NEF for construction of hierarchies, attribution of prestige to educators, and dynamic (re)positioning of individuals in the network60.

Upon choosing a network analysis perspective, oscillating between the quantitative and qualitative dimensions for historical research, we perceive the possibility of understanding how certain terms fall within and act in the historical-social dynamic. Although it is “out of style”, we believe the quantitative approach in association with digital history still has much to offer to historians.

Finally, it should be noted that in the quantitative data used here, there was no intention of representing all the terms referring to South America that are in the two journals. We can say that they operated as emulators of a qualitative approach of the theme. Names of cities, subjects, and educational institutions, for example, Mendoza, Juan Cassani, Juan Mantovani, and Universidad de Buenos Aires, were not included in the table simply through having been identified by human reading. This reminder shows the concern we should have in establishing and expanding discussions regarding digital history (of education). Beyond the disclosure of collections and experiences, it is important to observe aspects of a technological order in reference to digitization and to maintenance of digitized sources, as well as to the methodological treatment compatible with the new challenges of the historiographic operation.

Final comments

The approach launched here regarding the South American presence in the networks constituted by and through the NEF is still in the beginning. The highlights placed on educators and institutions, as well as periodicals and branches, requires deeper treatment through advances into the national histories of the countries mentioned (Colombia, Peru, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Ecuador, Chile, Bolivia), complementing and broadening the findings for Brazil61. In this scenario, recourse to transnational history of education seems unavoidable. Without disregarding national historiographic productions, whose support for interpretations regarding the actions of subjects is indispensable, the focus on the international movement of educators and on the establishment of networks tends to allow identification of new problems or to emulate new analyses of long-standing themes.

In the case of the international new education movement, this operation is fundamental, as it displaces the objects of study from national contexts, considering how the international injunctions operated both in legitimation of educators in their countries of origin, and also called for appropriations and hybridization of experiences and theories in an ever more connected world, whether as a result of increasing development of international capitalism or as an immediate result of fears engendered by the horrors of the First World War. Certainly, pedagogical trips and international study missions date back to decades prior to 1920, as well as internationalization of pedagogical ideas and artifacts. However, the end of the armed world conflict awakened, in the population in general and in educators in particular, the need to join spirits around a peaceful and supportive society. The choice of the term “fellowship” cannot be understood otherwise in characterizing the new network that formed in 1921 in Calais. The term “liga” that the NEF assumes in Latin countries, if it does not represent a direct translation of the term, retains its main primacy, expressed in the properties of mixture, of unity.

Upon attributing to itself the purpose of constituting an international brotherhood, the NEF forms quintessentially an entity that intends to transcend the nation-states in construction of universal school practices, taking as a foundation pedagogical and psychological principles that are also seen as universals. But what prompts taking it as an object of a transnational history of education is, beyond its objectives, the rapid spread of the web it was able to weave in the narrow period of 15 years and the likewise rapid movement of deconstruction that the network underwent in the geopolitical changes that occurred with the dawn of the Second World War. The NEF was thus a symptom and victim of the period between the wars.

Knowing the ways South American educators connected to the NEF helps us understand the (un)expected effects of international circulation of subjects, artifacts, and pedagogical models in a time period in which, through the very force of a scientific and empirical conception of school education, the first departments/faculties of education were incorporated in universities in different countries, changing the way teacher training occurred. It also helps us perceive the obstacles and the possibilities that then existed in the schooling process in South America, identifying bonds and tensions between educators and proposals. Furthermore, it helps us accompany the mechanisms activated in the constitution of networks and in the principles that dynamically organize their governance. Finally, it helps us better understand the origins of this “age of extremes”, as it was qualified by Eric Hobsbawm62.

REFERENCES

BARABÁSI, Albert-László. Linked: how everything is connected to everything else and what it means for business, science, and everyday life. New York: Plume, 2003. [ Links ]

BERNAL, Julio Santiago Cubillos. Agustín Nieto Caballero y el proceso de apropriación del pensamiento pedagógico y filosófico de John Dewey. Bogotá: Programa Editorial Universidad del Valle, Gimnasio moderno de Bogotá 2007. [ Links ]

BREHONY, Kevin. “A new education for a new era: the contribution of the conferences of the New Education Fellowship to the disciplinary field of education 1921-1938”, Paedagogica Historica 40, no. 5-6 (2004): 733-755. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, Marta Maria Chagas de. “A bordo do navio, lendo notícias do Brasil: o relato de viagem de Adolphe Ferrière”, em Viagens pedagógicas, org. Ana Chrystina Mignot e José Gonçalves Gondra. São Paulo: Cortez, 2007). [ Links ]

CUCUZZA, Héctor Rubén. “Desembarco de la Escuela Nueva en Buenos Aires. Heterogéneas naves atracan en puertos heterogéneos”, Pesquisa (Auto)Biográfica 2, no. 05 (2017): 310-329. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31892/rbpab2525-426X.2017.v2.n5.p310-329. [ Links ]

FRECHTEL, Ignacio. “Formas de circulación del conocimiento pedagógico renovador en la Argentina: revistas, visitas pedagógicas y exilios”, In Circulaciones, tránsitos y traducciones en la historia de la educación, org. Eduardo Galak, Ana Abramowski, Agustín Assaneo e Ignacio Frechtel. Buenos Aires: UNIPE: Editorial Universitaria; Saiehe, 2021. [ Links ]

FUCHS, Eckhardt. “Networks and the History of Education”, Paedagogica Historica 43, no. 2, (2007): 185-197. [ Links ]

GVIRTZ, Silvina; BAROLO, Gabriela. “A escola nova na Argentina. Apontamentos locais de uma tradição pedagógica transnacional”, In Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova, org. Vidal e Rabelo. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020, 133-152. [ Links ]

HAENGGELI-JENNI, Béatrice. L’Éducation nouvelle entre science et militance: débats et combats à travers la revue Pour l’Ère Nouvelle (1920-1940). Bern: Peter Lang, 2017. [ Links ]

HERRERA, Martha Cecilia. “Apropriações e ressignificações da Escola Nova na Colômbia na primeira metade do século XX”. In: Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova. Org. Diana Vidal e Rafaela Rabelo. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020. [ Links ]

HOBSBAWM, Eric. A era dos extremos. São Paulo: Cia. das Letras, 1995. [ Links ]

MIDDLETON, Sue. “Clare Soper’s hat: New Education Fellowship correspondence between Bloomsbury and New Zealand, 1938-1946”. History of Education 42, no. 1 (2013): 92-114. [ Links ]

MIDDLETON, Sue. “New Zealand Theosophists in ‘New Education’ networks, 1880s-1938”. History of Education Review 46, no. 1 (2017): 42-57. [ Links ]

MIGNOT, Ana Chrystina. “Claparède, mestre e amigo: memórias de travessias”. Revista Interinstitucional Artes de Educar 2, no. Especial (jun - out 2016): 253-265. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12957/riae.2016.25510 [ Links ]

MIGNOT, Ana Chrystina. “Eternizando travessia: memórias de formação em álbum de viagem”. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa (Auto)biográfica 2, no. 5 (2017): 330-42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31892/rbpab2525-426X.2017.v2.n5.p330-342 [ Links ]

NALERIO, Martha. “Sabas Olaizola”. In Historia de la Educación Uruguaya, Tomo III (1886-1930). Org. Agapo Luis Palomeque. Montevideo, Ediciones de la Plaza, 2012. [ Links ]

NEUMANN, Emma Salas. “Darío Enrique Salas Diáz: um educador de excepción”. Pensamiento educativo 34, (2004): 99-118. Disponível em: http://pensamientoeducativo.uc.cl/index.php/ pel/article/view/26643/21375. Acesso em: 9/8/2022. [ Links ]

PIRES, Raquel Lopes. Escritas itinerantes: a Reforma da Instrução Pública do Distrito Federal na revista Pour l’Ère Nouvelle e no Boletim de Educação Pública (1927-1931). Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2021. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL, Silvia. Contributos para uma discussão do conceito de rede na teoria sociológica, Oficina do CES nº 271, Março (2007). [ Links ]

RABELO, Rafaela Silva; VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves. “A seção brasileira da New Education Fellowship; (des) encontros e (des) conexões”. In: Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova. Org. Diana Vidal e Rafaela Rabelo. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020. [ Links ]

RABELO, Rafaela Silva, Ariadne Lopes Ecar, e Diana Gonçalves Vidal. “Caminhos que se cruzam na educação: Faria de Vasconcelos, Julio Larrea, Nieto Caballero e Lourenço Filho”. Trabalho apresentado no XII Congresso Luso-Brasileiro de História da Educação, Cuiabá, 2021. [ Links ]

ROLDÁN VERA, Eugenia; FUCHS, Eckhardt. “Introduction: the transnational in the History of Education”, In: The transnational in the History of Education: concepts and perspective. Org. Eckhardt Fuchs e Eugenia Roldán Vera. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019. [ Links ]

ROMANO, Antonio. “’Nueva Educación’ y enseñanza secundaria en Uruguay (1939-1963)”. Cadernos de História da Educação 15, no. 2 (2016): 468-491. Disponível em: https://seer.ufu.br/index.php/che/article/view/36090. Acesso em: 13 mai. 2023. [ Links ]

RUYSKENSVELDE, S. V. “Towards a history of e-ducation? Exploring the possibilities of digital humanities for the history of education”. Paedagogica Historica 50, no. 6 (2014): 861-870. [ Links ]

TORO-BLANCO, Pablo. “Conselhos de viajantes: a Escola Nova e a transformação do papel do professor no Chile (1920-1930). Um olhar conciso da história transnacional e das emoções”, In: Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova, org. Diana Vidal e Rafaela Rabelo. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020). [ Links ]

VAN GORP, Angelo, Frank Simon, e Marc Depaepe. “Frictions and fractions in the New Education Fellowship, 1920s-1930s: Montessori(ans) v. Decroly(ans)”. History of Education & Children’s Literature 12, no. 1, (2017): 251-270. [ Links ]

WATRAS, Joseph. “The New Education Fellowship and UNESCO’s programme of fundamental education”. Paedagogica historica 47, no. 1-2 (2011): 191-205. [ Links ]

ZAAGSMA, G. “On Digital History”. Low Countries Historical Review 128, no. 4 (2013): 3-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.9344 [ Links ]

2Kevin J. Brehony, “A new education for a new era: the contribution of the conferences of the New Education Fellowship to the disciplinary field of education 1921-1938”, Paedagogica Historica 40, no. 5-6 (2004): 733-55.

3Sue Middleton, “Clare Soper’s hat: New Education Fellowship correspondence between Bloomsbury and New Zealand, 1938-1946”, History of Education 42, no. 1, (2013): 92-114. Sue Middleton, “New Zealand Theosophists in ‘New Education’ networks, 1880s-1938”, History of Education Review 46, n. 1 (2017): 42-57.

4Béatrice Haenggeli-Jenni, L’Éducation nouvelle entre science et militance: débats et combats à travers la revue Pour l’Ère Nouvelle (1920-1940) (Bern: Peter Lang, 2017).

5Joseph Watras, “The New Education Fellowship and UNESCO’s programme of fundamental education”, Paedagogica historica 47, no. 1-2 (2011): 191-205.

6Regarding the participation of Lacombe, see Ana Christina Mignot, “‘Claparède, mestre e amigo’: memórias de travessias”, Revista Artes de Educar 2, no. 2, (2016): 253-265; Ana Christina Mignot, “Eternizando travessia: memórias de formação em álbum de viagem”. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa (Auto)biográfica 2, no. 5 (2017): 330- 342.

7Regarding the trip of Ferrière to Brazil, see Marta Maria Chagas de Carvalho, “A bordo do navio, lendo notícias do Brasil: o relato de viagem de Adolphe Ferrière”, in Viagens pedagógicas, org. Ana Chrystina Mignot and José Gonçalves Gondra (São Paulo: Cortez, 2007), 277-93; Raquel Lopes Pires. “Escritas itinerantes: a Reforma da Instrução Pública do Distrito Federal na revista Pour l’Ère Nouvelle e no Boletim de Educação Pública (1927-1931)” (Master’s degree thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2021).

8Joseph Coquoz, “Le Home ‘Chez Nous’ comme modèle d’attention à l’enfance”, Educació i Història: Revista d’Història de l’Educació, no. 20 (2012): 43.

10In the case of Brazil, it arises as a result of the visit of another educator, this time of Carleton Washburne from the United States. See: Rafaela Silva Rabelo and Diana Gonçalves Vidal, “A seção brasileira da New Education Fellowship; (des) encontros e (des) conexões”, In Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova. Org. Diana Gonçalves Vidal and Rafaela Silva Rabelo (Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020), 27-28.

11Eugenia Roldán Vera and Eckhardt Fuchs, “Introduction: the transnational in the History of Education”, In: The transnational in the History of Education: concepts and perspectives, Org. Eckhardt Fuchs and Eugenia Roldán Vera (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

12See, for example, Eckhardt Fuchs, “Networks and the History of Education”, Paedagogica Historica 43, no. 2, (2007): 185-197.

13Albert-László Barabási, Linked: how everything is connected to everything else and what it means for business, science, and everyday life (New York: Plume, 2003); Silvia Portugal, “Contributos para uma discussão do conceito de rede na teoria sociológica”, Oficina do CES nº 271, Março (2007).

26Rafaela Silva Rabelo and Diana Gonçalves Vidal, “A seção brasileira da New Education Fellowship: (des)encontros e (des)conexões”, In Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova, Org. Vidal e Rabelo (Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020), 25-47.

28Héctor Rubén Cucuzza, “Desembarco de la Escuela Nueva en Buenos Aires. Heterogéneas naves atracan en puertos heterogéneos”, Pesquisa (Auto)Biográfica 2, no. 05 (2017): 310-329.

29Silvina Gvirtz e Gabriela Barolo, “A escola nova na Argentina. Apontamentos locais de uma tradição pedagógica transnacional”, In Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova, org. Vidal e Rabelo (Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020), 133-152; Ignacio Frechtel, “Formas de circulación del conocimiento pedagógico renovador en la Argentina: revistas, visitas pedagógicas y exilios”, In Circulaciones, tránsitos y traducciones en la historia de la educación, org. Eduardo Galak, Ana Abramowski, Agustín Assaneo e Ignacio Frechtel (Buenos Aires: UNIPE: Editorial Universitaria; Saiehe, 2021), 19-33.

32Nueva era, no. 1 (1926). La Obra, que se ha consagrado en estos últimos tiempos a difundir con celo incansable los más recientes anhelos y tentativas de carácter educacional en los viejos países de Europa y en los Estados Unidos, revela la honda preocupación que a tales asuntos concede, inaugurando desde hoy, en sus páginas, una sección especial, denominada “Nueva Era”, con el único propósito de hacer conocer el estado actual del mundo en materia escolar, analizando en especial lo que se refiere al movimiento que unifica la “Liga Internacional para la Educación Nueva”, con la convicción más absoluta de la verdad que asisten a los fundadores del “Bureau”, cuando piensan que sólo una nueva mentalidad, generosa y amplia librará el buen combate contra las fuerzas del mal que parecen dominar hoy al mundo, y que esa nueva mentalidad sólo ha de ser posible con una nueva educación.

34Observe, for example, the issues of the TNE of the 1920s and beginning of the 1930s. Angelo Van Gorp, Frank Simon, Marc Depaepe, “Frictions and fractions in the New Education Fellowship, 1920s-1930s: Montessori(ans) v. Decroly(ans)”, History of Education & Children’s Literature 12, no. 1 (2017): 251-270.

35Nueva Era, no. 8 (1926). Acabamos de saber que en Locarno, célebre en los anales diplomáticos de los últimos tiempos, ha de realizarse el próximo congreso de la Liga para la Educación Nueva, durante la primera quincena de agosto de 1927. Como no lo ignoran nuestros lectores, las anteriores reuniones - que se llevan a cabo cada dos años - se efectuaron en Calais, Montreux y Heidelberg.

39Rafaela Silva Rabelo e Diana Gonçalves Vidal, “A seção brasileira da New Education Fellowship: (des)encontros e (des)conexões”, In Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova, org. Vidal e Rabelo (Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020), 25-47.

43Martha Nalerio, “Sabas Olaizola”, In Historia de la Educación Uruguaya, Tomo III (1886-1930), org. Agapo Luis Palomeque (Montevideo: Ediciones de la Plaza, 2012), 231-254; Antonio Romano, “’Nueva Educación’ y enseñanza secundaria en Uruguay (1939-1963)”, Cadernos de História da Educação 15, no. 2 (2016): 468-491.

45Julio Santiago Cubillos Bernal, Agustín Nieto Caballero y el proceso de apropriación del pensamiento pedagógico y filosófico de John Dewey (Bogotá: Programa Editorial Universidad del Valle, Gimnasio moderno de Bogotá, 2007); Rafaela Silva Rabelo, Ariadne Lopes Ecar e Diana Gonçalves Vidal, “Caminhos que se cruzam na educação: Faria de Vasconcelos, Julio Larrea, Nieto Caballero e Lourenço Filho”, trabalho apresentado no XII Congresso Luso-Brasileiro de História da Educação, Cuiabá, 2021.

46TNE is available for download at https://archive.org/details/uclinstituteofeducation; and PEN is available for download at https://www.unicaen.fr/recherche/mrsh/archives/ere_nouvelle/pen.html.

47Term used for the treatment given to digitized documents that passed through the optical character recognition process.

48Considering that the quality of digital files, whether in the process of digitization or in the OCR process, affect the reading system, their magnitude may vary. Yet, in working with qualitative analysis, we consider the data obtained valid for the proposed discussion.

49The first appearance of La Obra in TNE was in 1926 in the section “reviews and notes”. TNE, no. 28 (1926): 191.

50See discussion regarding the Ginásio Moderno de Bogotá in Herrera (2020). Martha Cecília Herrera, “Apropriações e ressignificações da Escola Nova na Colômbia na primeira metade do século XX”, In: Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova, org. Diana Vidal e Rafaela Rabelo (Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020), 25-48.

55Emma Salas Neumann, “Darío Enrique Salas Diáz: um educador de excepción”, Pensamiento educativo 34, (2004): 99-118.

56For a panorama of the context of the reforms and the new school pedagogical development in Chile in the 1920s and 1930s, see Pablo Toro-Blanco, “Conselhos de viajantes: a Escola Nova e a transformação do papel do professor no Chile (1920-1930). Um olhar conciso da história transnacional e das emoções”, In: Movimento Internacional da Educação Nova, org. Diana Vidal e Rafaela Rabelo (Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2020), 25-48.

58TNE, no. 6 (1932): 179. See analysis regarding the presence of Lourenço Filho as a participating memeber of the Nice Conference in Rabelo e Vidal, A seção brasileira da New Education Fellowship; (des) encontros e (des) conexões.

60Eckhardt Fuchs, “Networks and the History of Education”, Paedagogica Historica 43, no. 2 (2007): 185-97.

61In addition to the studies referred to throughout this article, noteworthy is the post-doctoral project developed by Franciele França entitled “A NEF no circuito sul-americano”, FAPESP process no. 2020/12621-3, under the supervision of Diana Vidal.

Received: October 11, 2022; Accepted: January 31, 2023

texto en

texto en