Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-163

Artigos

Republican speech and the debate on the formation of the Brazilian people in the trajectory of Virgilio Cardoso de Oliveira1

1Federal University of Pará (Brazil). albertod@ufpa.br

2Federal University of Paraná (Brazil). cevieira9@gmail.com

This article aims at discussing the trajectory of Virgilio Cardoso de Oliveira (1868-1935), focusing on the relation between the republican discourse and the debates on the formation of the Brazilian people in the context of the First Republic, especially in the period between centuries, in the Amazon region. In theoretical terms, we will explore the concept of intellectual, the notions of space of experience and horizons of expectations, as well as the concepts of language games and normative concepts. Among the sources used for the analysis, we highlight: newspapers, state documents, books, and images. We conclude by stating that Virgilio Cardoso represented an important position within republican discourse and practice, even though his power to transform the country's educational reality has been limited, by explicit and implicit resistance, to make the Republic a democratic project and capable of promoting political inclusion, and social justice.

Keywords: Virgilio Cardoso de Oliveira; Intellectuals; Formation of the people

O objetivo deste artigo é discutir a trajetória de Virgílio Cardoso de Oliveira (1868-1935), tendo como foco a relação entre o discurso republicano e os debates sobre a formação do povo brasileiro no contexto da Primeira República, especialmente no período do entresséculos, na região amazônica. Em termos teóricos, exploraremos, o conceito de intelectual, as noções de espaço de experiência e horizontes de expectativas, além dos conceitos de jogos de linguagem e conceitos normativos. Entre as fontes utilizadas para a análise destacamos: jornais, documentos do Estado, livros e imagens. Concluímos afirmando que Virgílio Cardoso representou uma posição importante dentro do discurso e da prática republicana, ainda que seu poder de transformar a realidade educacional do país tenha sido limitada, pelas resistências, explícitas e implícitas, em tornar a República um projeto democrático e capaz de promover inclusão política e a justiça social.

Palavras chave: Virgílio Cardoso de Oliveira; Intelectuais; Formação do povo

El objetivo de este artículo es discutir la trayectoria de Virgílio Cardoso de Oliveira (1868-1935), teniendo como foco la relación entre el discurso republicano y los debates sobre la formación del pueblo brasileño en el contexto de la Primera República, especialmente en el período del entresséculos, en la región amazónica. En términos teóricos, exploraremos, el concepto de intelectual, las nociones de espacio de experiencia y horizontes de expectativas, además de los conceptos de juegos de lenguaje y conceptos normativos. Entre las fuentes utilizadas para el análisis destacamos: periódicos, documentos del Estado, libros e imágenes. Concluimos afirmando que Virgilio Cardoso representó una posición importante dentro del discurso y de la práctica republicana, aunque su poder de transformar la realidad educativa del país haya sido limitada, por las resistencias, explícitas e implícitas, hacer de la República un proyecto democrático y capaz de promover la inclusión política y la justicia social.

Palabras clave: Virgilio Cardoso de Oliveira; Intelectuales; Formación del pueblo

Introduction

This article aims at discussing the intellectual trajectory of Virgilio Cardoso de Oliveira (1868-1935), focusing on the relation between the republican discourse and the debates on the formation of the Brazilian people in the context of the First Republic, especially in the period between centuries, in the Amazon region2.

We hypothesize that Virgílio Cardoso represented a radical aspect of republicanism, which defended the education of people as a basic principle for the construction of the Republic, confronting prevalent trends in republican circles that, without breaking with monarchist elitism, kept the popular classes on the sidelines of politics, insofar as they did not invest substantively in the processes concerning the formation of the people. We are convinced that Virgílio Cardoso's trajectory represents, to a large extent, a path common to many republican intellectuals, who projected a change in the Republic that included and went beyond the question of the form of government. Among these desired social reforms there was the question of the school and the formative processes of republican citizens, since, according to the beliefs of this group, only this type of investment would take the country to a new level of civility, modernity, and development. Therefore, the analysis we propose will allow, at the same time, to understand the public behavior of Virgílio Cardoso and the group of intellectuals to which he was linked3.

For this reflection on the trajectory of this character - understood as an influential intellectual in the education of the states of Amazonas and, above all, of Pará, at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century - we will start from four aspects that, according to Vieira (2011), help us to understand the public behavior of Brazilian intellectuals in this period:

a) feeling of belonging to the social stratum that, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, produced the intellectual's social identity; b) political engagement provided by the feeling of mission or social duty; c) elaboration and propagation of the discourse that establishes the relationship between education and modernity; d) assumption of the centrality of the State as a political agent for the realization of the modern project of social reform (VIEIRA, 2011, p. 29).

In theoretical terms, we will also explore the notions of space of experience and horizons of expectations, present in the formulations of the history of concepts, and, in the conclusions, we will question, in a specific way, the notions of language games and normative concepts, typical of the theory of interpretation supported by linguistic contextualism4. The combination of these approaches is justified by the common object: the language practiced by political actors.

Among the sources used to analyze Virgílio Cardoso's speech, we highlight: the brochure entitled O Instituto Civico-Juridico, published in 1898, which brings together seven articles published in the newspaper A Provincia do Pará. In this publication, Virgílio Cardoso exposes his ideas about republican education and, although he was at the time the General Director of Public Instruction for the state of Pará, he chose not to sign the articles, keeping them anonymous. He justified this option by arguing, later, that he had allowed the articles in question to enter the publicity scene unrelated to their name, obeying “an imposition of my sincerity towards the cause of the people and the Republic, which I advocated, without brilliance, it is certain, but with the utmost loyalty” (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1898, s.p.).

Another document that we will explore records a speech given by Virgílio Cardoso, in his capacity as Director General of Instruction of Pará, addressed to the members of the Superior Council of Public Instruction, on September 30, 1899, on the occasion of his inauguration as President of that collegiate, which was published in the magazine A Escola. From this same magazine, we will analyze other published materials. The works written by Virgílio Cardoso are numerous and many of them will be analyzed, however, there is a highlight to the book A Patria Brazileira, from 1903, which was later reissued and titled Nossa Patria. Other documents, from the press and official journals, in addition to biographical dictionaries, are part of the analyzed documentary corpus. The interpretation of these sources will allow us to access Virgílio Cardoso's discourse, language, beliefs, and public behavior, especially those related to his condition as an intellectual engaged in the defense of popular education, as well as his relations with the State and the political elite of the epoch5.

Having defined the documents that support this analysis, we would like to affirm, supported by Koselleck, that the historian, when diving into the past, goes beyond

his own experiences and memories, driven by questions, but also by desires, hopes, and concerns, he is first confronted with vestiges, which have been preserved until today, and which, in greater or lesser numbers, have reached us. By transforming these vestiges into sources that testify to the history he wants to learn, the historian always moves on two planes. Either he analyzes facts that have already been articulated in language or else, with the help of hypotheses and methods, he reconstructs facts that have not yet been articulated, but that he reveals from these traces (KOSELLECK, 2006, p. 305).

In this sense, based on the available evidence, we will continue to apprehend different aspects of Virgílio Cardoso's trajectory, from his formative process in Salvador to his arrival in Belém, where he became a prominent figure in the public education of the state. This study is located at the intersection between intellectual history, education, and intellectuals, also dialoguing with political history, especially in the period between centuries, in the scenario of the First Republic.

The trajectory of a traveling intellectual: between the space of experience and the horizons of expectations

On the title page of the book Meu Lar (s.d), Virgílio Cardoso summarizes his curriculum: Bachelor of Laws; Attorney of the Republic State of Minas Gerais; General Director of Public Instruction of Pará; Secretary General of the State of Pará; Secretary of State for Justice, Interior and Public Instruction of Pará; Administrator of the Post Office of the State of Pará; Director of Municipal Education of Belém; and Director of the Instituto Cívico Jurídico Paes de Carvalho of Belém. A career, without any doubt, marked by the occupation of numerous prominent positions in the public service. However, we are interested in knowing how this process went, from the anonymity of private life to consecration in the public space.

Virgílio Cardoso was born in Salvador, Bahia, on December 15th, 1868. Son of Rodolpho Cardoso de Oliveira and Maria Virginia da Motta, he had a brother, a medical doctor named Climério Cardoso de Oliveira6. Little information is available about his childhood and youth, we only know that he studied law at the prestigious Recife Faculty of Law. The Recife School, as this institution was named and consecrated in Brazilian intellectual history, was notable for its encyclopedic legal training, which linked legal knowledge to philosophy, literary criticism, sociology, and anthropology. Virgílio Cardoso completed his law course in 1889, precisely when the republican movement triumphed and there were intensified hopes for changes in the country.

The children of the Cardoso de Oliveira family, Climério and Virgílio, medical doctor and lawyer respectively, showed in their professional choices traits common to young people from wealthy families, interested in socially projecting their children, based on the prestige of liberal careers, typical in formation choices of the Brazilian intellectual elite in the last quarter of the 19th century. Already graduated, Virgílio Cardoso returned to Salvador and contributed to the foundation of the Faculty of Law of Bahia, becoming a member of the faculty of this institution, created in 1891.

From Salvador, he moved to Manaus, probably motivated by professional reasons. In this city, he began to practice law.

Source: Jornal Amazonas 07-28-1892 p. 4.

Figure 2: Advertisement for Virgílio Cardoso de Oliveira's law firm

In addition to maintaining a law firm with his partner, Virgílio Cardoso was an employee of the State, where he worked as Tax Prosecutor of the Treasury, Secretary of the Board of Trade, Curator of Bankruptcies, an examiner in public tenders in Portuguese and French tests and member of the Superior Council of Instruction. In these first incursions into the public service, one could promptly identify a concern to work in the area of education, either as an examiner of public tenders or as a Councilor responsible for reflecting on the directions of public education in the state of Amazonas.

During his stay in Manaus, he wrote Memorias sobre a historia do Estado, widely publicized in the Amazon press and reported by Augusto Blake in his Diccionario Bibliographico Brazileiro.

In the field of journalism, he was the owner and editor of a periodical called Archivo Juridico and editor-in-chief of the newspaper Correio da Manhã, defined by him as

completely oblivious to parties' fights, with the main objective of dealing with the improvements demanded by Amazonas, and with high political interests that can help the administration in its general utility plans, without prejudice to fair censorship, when necessary (Diario de Manáos, 04/20/1893, p. 1).

His work in the press reveals his concern for intervention in the public space, vocalizing and guiding problems related to city life and, above all, associated with the experience of building the republican project.

In this period Virgílio Cardoso began as a writer of textbooks and reading books, all with strong civic content, such as Ligeiros traços and Leitura amena, elementary works that the Fiscal Council of Public Instruction of Amazonas authorized for use in primary schools and for which he received the prize of Rs2:000$000 (two contos de réis) from the state government.

These writings promptly and unquestionably show Virgílio Cardoso's belief in republican values and the importance of public education for the consolidation of the new form of state organization. His republicanism was associated with the group of Silva Jardim, one of the exponents of republican radicalism and a notorious interpreter of the work of August Comte in Brazil7. Justifying this option, Virgílio Cardoso considered that

with the reaction carried out by all arbitrary means, to the point that the police would no longer allow a 'long life' to the Republic, it was no longer possible to appeal for the sweet peace of the schools, for the slow action of propaganda. I then became a sectarian of the Silva Jardim dissidence: - the Republic by any means ( VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1898, p. 12).

The move to Belém represented the culmination moment in his trajectory, especially concerning his work in the educational sphere and the occupation of spaces of power in state structures. We believe that this transfer took place between 1898 and 1899 since we identified Virgílio Cardoso in the list of voters who changed residence, in an official source of the state (Diario Official do Amazonas, 7/7/1899, p. 16522).

In Pará, he established a strong relation with the newspaper A Provincia do Pará, owned by Antonio Lemos, Intendant of Belém and a first-time ally that would allow him to reach higher levels in the field of public education. Throughout his performance in the state, he held different public positions, among them that of Substitute Federal Judge; General Director of Public Instruction of the State of Pará; Head of the Secretariat for the Interior, Justice, and Transport; Director of the Instituto Cívico Jurídico Paes de Carvalho; Director of Municipal Education and Post Office Administrator. In the exercise of these functions, he always expressed his uncompromising position in defense of the Republic and in favor of an education based on moral and civic values. He was the founder and editor-in-chief of the official teaching magazine of the municipality of Belém, called A Escola, which was created in 1900 and was characterized by disseminating themes, which were intended to support teachers in their school practices.

Virgílio Cardoso was one of the founding partners of the Historical and Geographical Institute of Pará - IHGP, an institution created on May 3, 1900, during the government of José Paes de Carvalho, under the name of Historical, Geographical and Ethnographic Institute of Pará. He also wrote books and newspaper articles on a variety of subjects, ranging from poetry to legal and educational matters.

As already mentioned, his most important work was A Patria brazileira, sponsored by the Municipal Intendant of Belém, Antonio Lemos, who, in a letter to the Municipal Council, requested a pecuniary amount to finance the publication, which was granted under the argument of the importance of the work for the instruction and dissemination of republican values. The reviewers considered that this work was “effectively of value, not only as an element of national education, but also as valuable propaganda for Brazilian things, and propaganda all the more profitable as the book should be illustrated with 260 engravings" (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1903, p. III).

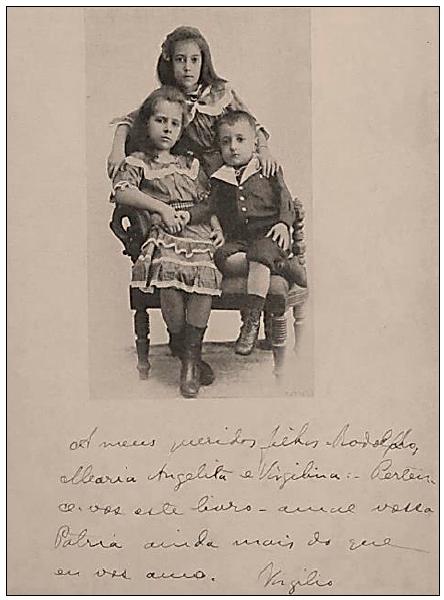

It is important to note that the first of these engravings is a photo of Virgílio’s children, followed by a dedication with the following message: “To my dear children - Rodolpho, Maria Angelita and Virgilina: This book belongs to you - love your country even more than I do love you. Virgilio ” (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1903, p. V).

Source: Book A Patria brazileira

Figure 3 Photo of Virgílio Cardoso's children by Virgílio Cardoso with dedication

The book deserved “compliments and praises, in opinions unanimously approved by the superior councils of Public Instruction of the States of Pará, Parahyba and Goyaz” (BAHIA ILLUSTRADA, September/1918, p. 6) and was praised by the Bahian magazine as being “one of the best, if not the best, that we have in the genre, [it] must be featured in all the schools, to whose directors and teachers we appeal, in the name of the Republic” (idem, p. 6).

In another issue of this magazine, in a column called Notas sobre a instrução primária baiana, the author talks about the importance of reading Virgílio Cardoso's work for childhood and compares him with Olavo Bilac, Coelho Neto and Manoel Bomfim, since he wrote: "with paternal affection, books full of instructive subjects, [with] very salutary moral and civic precepts” (BAHIA ILUSTRADA, February 1919, p. 46).

Based on this evidence, we can affirm that Virgílio Cardoso's trajectory articulated the fields of law, education, and politics, projecting a polygraph intellectual, versed in different subjects and active as a lawyer, graduated public servant, journalist, and writer 8.

For Koselleck (2006), “all histories were constituted by people's lived experiences and expectations” (KOSELLECK, 2006, p. 306). According to the German historian:

Experience is the current past, the one in which events have been incorporated and can be remembered. In experience, rational elaboration and unconscious forms of behavior are both merged [...] Furthermore, in the experience of each one, transmitted by generations and institutions, an experience of others is always contained and preserved. In this sense, history has always been conceived as knowledge of the experiences of others. Something similar can be said of expectation: it too is linked to the person and the interpersonal at the same time, expectation is also fulfilled today, it is the present future, turned towards the not-yet, towards the unexperienced, towards what can only be predicted. Hope and fear, desire and will, restlessness, but also rational analysis (2006, p.310) 9.

Thus, Virgílio Cardoso, as an intellectual who proposed to accomplish a vital mission for the implantation of the Republic, accumulated experiences in the political and educational fields and projected his desires, his horizons of expectations concerning a Republic, which was organized, educated, and shaped by the civic and patriotic spirit. In his abnegation to the republican project, he maintained that

in the development of our ideas, in each act or public function that we are called to exercise, and even in any relation in social or private life, let us convince ourselves that these two powerful elements will not be entirely effective if they are not closely supported by the - Peace - and by - Concordia -, without which it cannot be ensured the - Order -, the basis of every stable organization, and it cannot be achieved the - Progress -, the crowning of all social efforts ( VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1903, p. 357).

In the positivist-inspired binomial of order and progress, we identify, especially, in the second term of the pair, a concept that marked the horizons of expectations of the 19th century, included, as is well known, in the flag of republican Brazil. According to Koselleck, the concept of

Spiritual "prophecies" had been replaced by a mundane "progressus". The objective of a possible perfection, which before could only be achieved in the beyond, was put at the service of an improvement of earthly existence, which allowed the doctrine of ultimate ends to be surpassed, assuming the risk of an open future (2006, p.316).

The space of experience in which the intellectual Virgílio Cardoso worked was situated between centuries, when Brazil ceased to be ruled by a Monarchy and started to organize itself as a Republic. Under the aegis of the telos of progress, the country began to experience, gradually, modernizing changes in its daily life, among which can be highlighted the concern with public health and hygiene, the incorporation of scientific and technological advances in social life, and the implementation of a new model of public instruction. This model, outlined in Benjamin Constant's Reform of 1890, provided for: the graded primary school, organized in the form of school groups; reforms at the secondary level and higher education; the creation of Pedagogium, an institution that aimed to transform the processes of teacher training; the new intuitive and practical teaching methods; and the emphasis on science and mathematics at the expense of literary studies.

The intellectual, the education and the political field: republican conflicts in the Amazonian belle époque

In the Amazon, since the 18th century, economic strategies were already different from the rest of the country. In this sense, Souza (2002) warns that

In Grão-Pará and Rio Negro, the economy was based on manufactured production, based on the transformation of latex. It was a flourishing industry, producing world-renowned objects such as shoes and wellies, waterproof covers, springs, and surgical instruments, destined for export or domestic consumption. It was also based on the naval industry and smallholder agriculture. (SOUZA, 2002, p. 32).

The city of Belém was built to be the administrative capital of the region and for that, the Bolognese architect and urban planner Antônio José Landi was hired. In the state of Pará, this was a period of economic prosperity, for it is located in the so-called age of rubber:

During this period, 15 new establishments were installed, including two important newspapers: "A Província do Pará" (1876) and "A Folha do Norte" (1896), which contributed to the dissemination of information about Pará and the Amazon region. The industrial census of 1892 found the existence of 89 establishments, excluding sugar and aguardente mills and printing shops, classified as 'solid factories', among which 35 steam sawmills and 35 potteries linked to civil construction stood out. The editorial and graphic service had 41 typographic and two lithographic workshops, responsible for the production and editing of thirty-two newspapers, books, and other graphic materials in Pará (albums, Indicador Ilustrado do Pará, magazines, etc.). It is noteworthy that all the regional material for the 1911 Turin International Exhibition was produced in some of these establishments, as well as the advertising materials of local industries (MOURÃO, 2017, p. 9).

It is important to highlight that, in the so-called belle époque, Belém was an important pole of innovations, which were not only limited to large economic transactions or European-styled urbanization initiatives. In a document of accountability in the area of public education, dating from 1900, Governor José Paes de Carvalho, asserts that for the first time, in the form of republican government, public education had a reform "pierced by the modern pedagogic methods, inspired by the best lessons provided by doctrine and practice, this reform was, we can say, the solid base on which the foundation that today sustains the public instruction of the State was set”. (PARÁ, 1900, p. 6). He reiterates that this reform was the one that, for the first time, “gave primary education the program most compatible with the demands of our educational environment and more in line with modern pedagogic methods. (PARÁ, 1900, p. 7).

The new political, economic, and cultural demands required human resources capable of facing the challenges of a country that aimed to enter the developed world, and in this context, education was presented as a strategic instrument for the organization of the Republic. It was under these circumstances, with the new regime imposing itself, that public instruction came to represent an instrument for national redemption, forming the nationality that, according to the rhetoric of republican elites, would transform the inhabitants of the territory into patriotic and civilized citizens, who were capable to correspond to the aspirations and intents of the country.

It was in response to these expectations that took place “the affirmation of the new regime in the face of society, through policies of valuing public instruction and the exaltation of civic and moral values” (COSTA; MENEZES NETO, 2016, p. 70). In the same line of thought, Shueler and Magaldi (2009) argue that a key element in the project of the republican primary school, "concerns the role assumed by this institution in the formation of character and the development of moral virtues, patriotic feelings, and discipline in the child" (SCHUELER & MAGALDI, 2009, p. 45).

In Pará, the situation was not different, the legal document that guided the structure and functioning of primary education provided for the offer of a subject called Civic Culture, whose program provided for the

reading and explanation of the Federal and State constitutions - Succinct notions and practices of national law. - Basic provisions of the main federal and state laws - Civil rights and political rights - Requirements for the full enjoyment of both - Essential qualities to the contracting parties - Civil duties - Civility and public spirit (PARÁ, 1890, p. 25).

In addition to civic culture, subjects such as Moral Culture, also in primary education, aimed to instill in children “the cult of the truth, the beautiful and the good, and preparing them to become good citizens in the future, will strive to prepare humanity in general - and this is the higher end of education - good and useful servants” (PARÁ, 1890, p. 45).

It is noticed, and historiography confirms, that in the republican primary school project, scientific and mathematical knowledge, even though they were the basis of positivist philosophy, did not represent the main formative investment. Moral and civic values, hygienic habits, and physical culture were the privileged contents in the training of children and young people. Historical, geographical, and linguistic knowledge were also associated with the dissemination of civic and patriotic values. This project engendered transformations in the field of instruction that materialized in new buildings, teaching methods, and didactic materials. A large investment was dedicated to the training of teachers since they would be the intermediaries of republican values to the students and their families.

It was in this scenario that Virgílio Cardoso - a Bahian, lawyer, fervent republican, in his early 30s and newly settled in Pará - took on the top position of public education in Pará. In this role, he created the Revista A Escola, intending to inform teachers about the programs and teaching reforms in progress. He proposed the creation of a pedagogical center that would constitute an "association to which only members of the teaching staff and people dedicated to public instruction, by acts or published works, should belong, creating a special library for the purposes of the institution” (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1899, p. 17) and he was directly responsible for structuring the Pedagogical Congress of Pará 10.

Ahead of the pedagogical renovation of the state, Virgílio Cardoso relativized some symbols of modernity and the opulence of the main cities in the country, in the name of what he considered to be the true signs of national modernity:

In the budgets, before taking care of embellishments, luxurious buildings, etc., etc., a large quota should be set aside for the diffusion, by all means, of the instruction of the people, who will benefit more from having an enlightened spirit than beautiful panoramas to delight their eyes. What advances can be applied to the Republic, to its aggrandizement and prestige, if we flaunt to foreign eyes our well-groomed capitals, luxuriously built, brilliantly illuminated, but the people lying in the blindest ignorance of the system of government that rules them, of their most rudimentary political duties and rights? How can we dispute in South America the place of honor that nature has destined for us, the hegemony that the United States has already conquered in North America if our Republic does not flow from the pages of the Constitution and the laws to the conscience of the people if they do not know how to understand its sovereignty? (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1898, p. 27).

Modernity for Virgílio Cardoso was based on public instruction, an essential factor for overcoming ignorance, reputed by him as a striking feature of the monarchic period. In this context, the issue of the education of the people and the success of the republican cause are presented as inseparable aspects, as we can see in this manifestation:

Instruction, gentlemen, has occupied my public life for a decade, a large part of my soul! (...) A convinced republican, I turned to the instruction of the people, the throbbing element of the Republic life, which I cherished in my young dreams, the only political ideal that uninterruptedly moved my life as a citizen (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1900-A, p. 10).

In this excerpt, it is clear his adherence to Montesquieu's idea that the “republican government is, of all political regimes, the one in which the issue of education is placed most seriously” (MONTESQUIEU, quoted by VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1898, p. 20). Nevertheless, the republican educational project did not develop without conflicts. In the case of Pará, this was boosted by the economic strength of the state, which was experiencing, in the period between centuries, the height of the rubber cycle. Many resources always generate fierce disputes and, thus, Virgílio Cardoso's rise in public service, in a strategic area such as education, was marked by strong struggles between the main republican state leaders. Among Virgílio Cardoso's main allies we can identify Antonio Lemos, leader of the Republican Party of Pará and Intendant of Belém, and José Paes de Carvalho, Governor of the State. In opposition Lauro Sodré, leader of the Federal Republican Party. Lemistas and Lauristas, as the groups in the confrontation were called, held strong positions in the press, making it one of the main stages of disputes11. Common at the time, each of these groups and parties had their own organs for the dissemination of ideas, programs, and proposals, therefore, understanding their connections is essential to comprehend the messages addressed to or related to Virgílio Cardoso, especially when he was ahead of the General Directorate of Public Instruction.

Virgílio Cardoso, aware of the climate of antagonism, warned, in his inaugural speech at the Presidency of the Superior Council for Public Instruction, that “the disorderly scream, which, for many days after my investiture in this position, tied my obscure name to the black pole of evil insinuations, may have, in some way, warned your spirit” (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1899, p. 9) and continues alleging that “it is not for me, therefore, that I fear; it is for you, to the detriment of instruction; for you, so that you can place me in a circle of distrust, of ill will, of inertia, of withdrawal, harming the good progress of the business of instruction. (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1899, p. 9).

The oppositionists' criticism was harsh and relentless and focused mainly on two issues: the civic conferences promoted by the management of the Director General of Public Instruction and the way this leader related to the capital's primary teachers. The Civic Conferences, created by Virgílio Cardoso, were aimed at children and consisted of a series of lectures given in schools by people considered to have notorious knowledge. These had strong civic-patriotic content and aimed to convey the feeling of nationality.

In an article published in the República newspaper, Virgílio Cardoso is asked about the project: “why [Virgílio Cardoso] didn’t invite a teacher [...] in the respectable body of primary teachers of this State, there is not just one able to present a good pedagogy conference” (REPUBLICA, 09/01/1900, p. 1). In this same newspaper, in its issue of September 9, a column entitled Mosaicos, by an unidentified author, makes ironic criticisms of the conference given by Elyseu Cezar, one of the guests invited by Virgílio Cardoso, stating that

due to the drowsiness that the conference provoked, the kids were not very excited. Taken ‘forciori’ to attend didactics lectures, taken from their childhood games, dragged from the holy coexistence of their family to hear something they do not understand nor want to understand”. Finally, the author asks for mercy and recommends that “if you have to go back to the conferences again, pity these poor little children who are not to blame for making Mr. Virgílio Cardoso the director of instruction. (REPUBLICA, 09/09/1900, p. 2).

The criticism to the Director of Instruction is not limited to the conferences promoted, they also insist on the lack of attention to primary teachers:

because Mr. Dr. Virgílio does not surround himself with primary teachers of this capital, who are intelligent and prepared in their absolute majority? For what reason the primary teacher is not called to prepare the regulations for public instruction? The only one in the conditions of adapting them to our environment and extirpating the shameful errors making them finally feasible. It doesn't happen, however; Mr. Dr. Virgílio treats teachers as if they were regulars in his department, even barring them from entering their secretariat (REPUBLICA, 09/01/1900, p.1).

On September 1st, 1900, the Republica published a note, whose title was Chaos in the instruction, signed with the pseudonym Justice. The author of the note claimed that the state of the education of the people was unsatisfactory and argued that Virgílio Cardoso wanted to

raise his name to the high regions [and] dreaming of his future triumphs, invents, reforms and details every day a novelty in the general directory of public education, without having the slightest practice [...] to Mr. Dr. Virgílio it will not lack illustration, however, he lacks the most necessary thing, which is circumspection and common sense (REPUBLICA, 09/01/1900, p. 1).

On the other hand, political allies also manifested themselves. The newspaper O Pará, of September 11, 1900, published on the front page a column called Despeitados, in which it characterized the opponents of the ideas of the leader of public instruction as disloyal opponents and blinded by partisan passion, arguing that the “active illustrious man who directs public instruction [is] the target of the hatred and contempt by federals, who refuse to expose these detestable feelings to public commiseration [...] to tarnish the good name of this land” (O PARÁ, 09/11/1900, p. 1). 12 Trying to clarify the causes of contempt, the author of the journalistic article states that Virgílio Cardoso “has taken some patriotic measures, in order to awake in childhood the love of study, of transmitting to him from now the first rudiments of civic education that forms the character of the citizen” (O PARÁ, 11/09/1900, p. 1).

Virgílio Cardoso's polemics were not limited to the regional conflict, between Laurists and Lemistas, his ideas confronted the directions of the republican educational project. Ahead of the Superior Council of Public Instruction, in his first speech as its President, in addition to accusing the Monarchy of having deliberately spread ignorance for its own benefit, he also criticizes the Republic, which failed to do what should have been done in regarding its tasks for the consolidation of what would be the greatest weapon in the fight against ignorance.

In his view “the school was forgotten as one of the main factors of national character, because it is there, in this environment, that the citizen prepare must begin” (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1898, p. 13). On another occasion, comparing the instruction to light, he states that

A people without light is a people without life; a machinery that unfolds unconscious of itself and of the outside world, moved only by material needs, without ambitions, without energies, without incentives, which are indispensable for the progress of social life. This, under the Republic, is a danger for it and for the people themselves (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1900-A, p. 10).

Virgílio Cardoso did not spare the Republic with his criticisms of the government's negligence concerning education, getting to the point of comparing it to the Monarchy. For him, "the people, who watched 'bestialized', in the phrase of Aristides Lobo, the proclamation of the Republic, continued in the same criminal ignorance, which the monarchy bequeathed to us” (VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1898, p. 13). He continues with the argument and insists on the thesis that “the federal and state governments have not been properly convinced, it must be said, that the most appropriate weapon, the one necessary even for the consolidation of the Republic, the true Republic, is the instruction” ( VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, 1898, p. 14).

It is remarkable in his speech a tension between devotion to the republican form of government and dismay concerning republican governments due to the lack of initiatives or the slowness in the implementation of structural reforms in popular education. Although, in the first republican decade, the Federal District and some cities, usually state capitals, advanced in terms of expanding the public education network, the reality of the interior of the country remained unchanged compared to the times of the Monarchy. Resistance to the expansion and qualification of public education did not come from the monarchist opposition, which was already quite weakened in this period, but from the republican political and economic elites themselves, which remained insensitive to the demands of the population, especially from the most economically and socially vulnerable sectors.

This ambiguous feeling of Virgílio Cardoso can be seen in his opening speech to the first ordinary session of the Pedagogical Congress, in January 1901, in which he - as Director General of Public Instruction and President of the event - demonstrates his dissatisfaction with the resistance to his projects:

So, the idea was launched again, supported only by my obscure individuality, in a frank struggle with the indifference of some and the ill will of others, finding at every step a word of discouragement, of dismay; overwhelmed, finally, by the responsibility of the attempt on such a far-reaching issue, there must be no small satisfaction in my soul at this moment, sitting in the chair of the presidency of this Congress, already officially installed, in a solemn and memorable session. Therefore, my thorny mission is accomplished (A ESCOLA, 1901, p. 241-242).

It is important to highlight that this group of republicans dissatisfied with the direction of the Republic did not adopt the strategy of mobilizing the population or the social movement in the sense of vocalizing their demands for the expansion of education and, by extension, for the inclusion of the population in politics and civic life. These radicals - marked by their wealthy social origins, their close contact with the economic and political elites, and, above all, by their adherence to positivist theses that relativized democracy - vocalized the popular feeling for more education, but kept their horizons of expectations focused on the action of the State. They understood that their vehement rhetoric should have the State and the government as interlocutors so that the intended social reform continued as a possibility associated with the effective action of the State, which would reorganize society based on the formation of the people.

Final considerations

In this article, we set out to analyze the trajectory of Virgílio Cardoso, with emphasis on his ideas and the institutional spaces where he circulated and acted as an intellectual engaged in the defense of the education of the Brazilian people. As a guiding concept for the analysis, we adopted the perspective presented by Vieira (2011), which aims at defining the public behavior of Brazilian intellectuals, directly associated with the educational field, between the last quarter of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. This definition brings together four main aspects: adherence to the identity of the group of intellectuals, political engagement, the discourse on the relation between investments in education and the rise of the country to the select group of developed and modern countries, and the belief in the action of the State as a political agent capable of carrying out the desired reforms.

We believe that the analysis carried out brings Virgílio Cardoso closer to this set of characteristics that, without disregarding the singularities of the intellectuals involved in the formation of the intellectual and educational fields in Brazil, allows articulating a common behavior, allowing a degree of generalization in the understanding of this elite holder of social prestige and political influence.

We present as a hypothesis the position of Virgílio Cardoso in a more radical fringe of republicanism that, in addition to defending the republican form of government, defended a broader social agenda, including, especially, the issue of popular education. These theses led Virgílio Cardoso and many republicans to confront the political directions of republican governments, since the Brazilian social scenario, after a decade of republican power, continued without major changes, especially concerning the formation of the people. Composing this group we can mention some names: Júlio Mesquita and Caetano de Campos, in São Paulo; Afrânio Peixoto, in Bahia; Dario Vellozo, in Paraná; José Veríssimo, in Pará; Silvio Romero and Manoel Bomfim, in Sergipe; and Benjamin Constant himself, in Rio de Janeiro.

In common among these intellectuals, in addition to belonging to the so-called generation of 1870, republicanism and enthusiasm for education, in the expression made famous by Jorge Nagle, in Educação e sociedade na primeira república. They also shared, to some extent, the dismay concerning the place occupied by education in successive republican governments. José Veríssimo, whom Virgílio Cardoso succeeded as Director General of Public Instruction of Pará, in his 1892 work A Educação Nacional, which brought together articles published in Jornal do Brasil, argues that republican education, despite some advances, maintained, more than changed, the education scenario in the country. Veríssimo's harshest criticism was concerning the exaggerations of the implemented federalism, greatly aggravating the situation of the primary school, relegated to state and municipal initiatives.

The first years of the Republic did not correspond to the horizon of expectations of its most devout militants:

Proclaimed by the military, the Republic was marked by constant instability, civil wars, financial crisis, and a lack of order and progress. From 1889 to 1897, there were two military presidents and one civilian. The first soldier was forced to resign. The second one faced two civil wars, one in the South, and the other in the capital. The civilian, Prudente de Morais, had a government disturbed by conflicts with the Party and Congress, by military and popular uprisings, and suffered an assassination attempt. The country was on the brink of financial bankruptcy (CARVALHO, 2011, p.155-6).

The trinomial republic-democracy-federalism, explained in the Republican Manifesto of 1870, was restricted to the republic-federalism pair. The first Republican Constitution established that everyone was equal before the law, did not admit birth privileges, ignored nobility forums, and extinguished the existing honorary orders, as well as all their prerogatives and privileges, formally characterizing a given concept of citizenship linked to the notion of right, moving away from the oligarchic and absolutist conception of benefit and privilege for the few. However, it also ended up excluding the poor, the illiterate, and women from the exercise of universal suffrage. Silva Jardim himself, the republican leader to whom Virgílio Cardoso declared loyalty, was not noted by the defense of democracy. The latter, on the contrary, defended a sociocratic republican dictatorship, in which the State - as opposed to the people, who remained trapped in the theological mentality - would play the role of a civilizing force.

In this way, republican citizenship in Brazil was consummated from a foundation of inequality and exclusion, not doing justice to the meaning of res publica and denying its seminal prerogative of belonging “to the people” and of being “of all”. In the expression of Carvalho (2011), we had a Republic without a people, in which only 5% of the population exercised the right to vote and to be voted on.

Thus, we identified a lack of harmony between the origins of the movement and the republican government, which Carvalho (2011) problematized, asserting that

the transformation of liberal radicalism into republicanism represented a setback or, at least, a halt in the struggle for political and social reforms. The fact was due to the concentration of the debate, operated after the Republican Manifesto of 1870, around the form of government, monarchy or republic, to the detriment of other themes of equal or greater relevance (p.142).

The people's education program, based on civic and patriotic formation, and assumed by Virgílio Cardoso and other intellectuals, aimed to produce direct impacts on the distribution of political power since literacy was a condition for the inclusion of individuals in the universe of voters. However, despite advances in the process of popular schooling, in the period between centuries, these were concentrated in the most important cities, which already had a physical structure and staff of teachers trained in normal schools. The desired social reforms, which marked the formation of the republican discourse until the advent of the proclamation, the period of formation of the young Virgílio Cardoso in the School of Recife, were being passed over in the name of a discussion that privileged the republican-federalist form of government.

In practical terms, in the first decade of the republican government, very little was done in terms of public education and, above all, expansion and qualification of the primary school. In the 1891 Constitution, the federal government was responsible for administering public instruction only in the Federal District, at the time located in the city of Rio de Janeiro, so the federative principle decentralized educational actions. In São Paulo, for example, changes were felt in the dynamization and organization of school groups and the new Normal Schools. Other capitals, such as the prosperous Belém, also showed progress, but at a lesser pace and extent. However, in the interior of the country and the poorest states of the federation, teaching conditions did not change significantly during the times of the Monarchy.

In the path of the reforms of 1890 proposed by Constant, there were subtle changes in secondary and higher education, aimed at the elites. However, the Enlightenment and, later, the democratic-republican project of massification of popular education, which gained momentum in Europe and the United States throughout the 19th century, did not succeed in Brazil in the first republican phase. The controversial creation of the Ministry of Instruction, Mail, and Telegraphs, in 1891, when it was extinguished the following year, relegated public instruction to a department in the Ministry of Justice, as it was in the Empire. The democratic ideals, which articulated horizons of expectations in tune with the dissemination of the school and the expansion of the cultural level of the people, were blocked by the victory of federalism and the reconquest of power by the state oligarchies in the last years of the 19th century. In the so-called Politics of the Governors, the formation of the people lost importance, returning to prominence only in the 1920s, in the context of the crisis of the Old Republic13.

Virgílio Cardoso was situated in this space of experience and, as a result, had his horizons of expectations frustrated. However, as a man of politics, he knew how to occupy spaces and carry on with his banners, even facing resistance to his projects related to public instruction. The criticisms from part of the republican press to Virgílio Cardoso's administration, which we showed earlier in this study, reinforce the idea of politics as a field of bloody disputes, in which opponents are not spared and arguments, as a rule, are constituted by disqualifying logics, having irony as a fundamental piece in the production of these rhetoric. However, Virgílio Cardoso resisted the attacks, since he was well positioned in the game of state forces. It is also noticeable that the critics took certain precautions not to go beyond the limits of the believable and plausible, in order to not attack the republican fidelity, the formation, and intellectual qualification of the Director General. Thus, his condition as a republican politician and prestigious intellectual remained untouched, reducing criticism of the regional quarrels of the Lemistas and Lauristas groups, so that the memory of his management at the head of public instruction remained untouched.

Virgílio Cardoso revealed in his trajectory of traveling intellectual, great competence to promote himself and be noticed, because, despite not being from Pará by birth, he enjoyed the trust of the Governor of Pará and the Intendant of Belém. The Bahian intellectual had a life intensely dedicated to education in the states of Amazonas and, especially, Pará, assuming prominent public positions and writing works that impacted the region and gained national notoriety. His capital work, called A Patria brazileira, still reverberates in recent works such as that of the Brazilianist Thomas Skidmore (2012) and the researchers Lajolo and Zilberman (2019).

Virgílio Cardoso's speech and language were marked by a peculiar language game, typical of this group of republicans engaged in the educational cause. By analyzing his book O Instituto Civico-Jurídico, from 1898, we identified the core of the normative concepts that governed this language game practiced by Virgílio Cardoso and his peers. These concepts form the structure of the main group of meanings in circulation and dispute in this language game. The normative concepts,

in contrast to ordinary terms, form a group of words shared and valued as essential to express the way of thinking and speaking of a particular social, professional, political, or religious group. These concepts allow, on the one hand, the perception and interpretation of the space of experience and, on the other hand, the elaboration of projects and horizons of expectation of those who enunciate them (VIEIRA, 2021, p.18) 14.

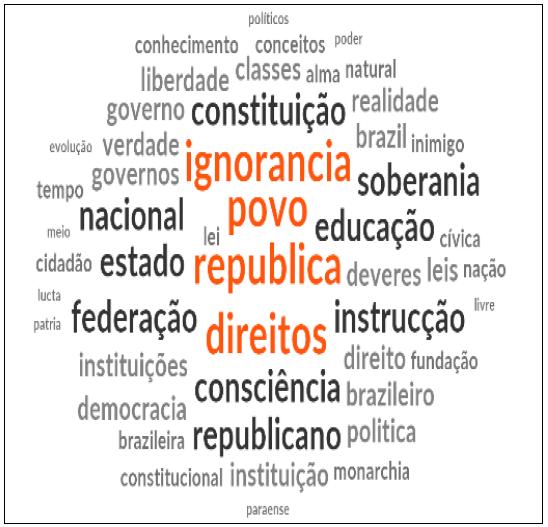

Analyzing Virgílio Cardoso's vocabulary, we identified a language game typical of the political field, which associated terms from republican, civic, nationalist, and educational discourses.

Source: O Instituto Civico-Juridico, created by the authors, using the NVivo software 15.

Figure 5: The 50 most frequent words in the brochure Instituto Civico-Juridico

This language voiced the beliefs and projects of intellectuals in different Brazilian states who, like Virgílio Cardoso, approached and connected concepts such as republic, nation, sovereignty, state, federation, constitution, people, rights, ignorance, instruction, and education. The combination of these concepts produced a discourse that highlighted the centrality of citizens' education as a way of fighting ignorance and forging national awareness. This belief in the power of education represents a phenomenon, still very present among us, called by Smeyers and Depaepe (2008), educationalization, which magnetized the discourses on the formation of modern nation states in different continents and was inserted peculiarly in the context part of the republican movement in Brazil.

The traveling intellectual Virgílio Cardoso, after his experience in Belém, still held public functions in Minas Gerais, where he was State Attorney until he returned to Salvador, where he died at the age of 66, on December 9, 1935. His trajectory, speech, and language are exemplary of a generation of Brazilian intellectuals, engaged in the causes of the Republic and the instruction of the people, who were not known for original and innovative works, but for their perseverance in spreading values dear to the movements and groups to which they belonged. In this aspect, it is worth revisiting Gramsci's notion of intellectual, who asserts that

creating a new culture is not just about making individual 'original' discoveries; it also means, and above all, critically disseminating already discovered truths, 'socializing' them, so to speak; transforming them, therefore, into the basis of vital actions, into an element of coordination and of an intellectual and moral order (1999, p. 95-96).

In summary, we can conclude that Virgílio Cardoso represented an important position within republican discourse and practice, even though his power to transform the country's educational reality was limited, by resistance, both explicit and implicit, in making the Republic a democratic project, capable of promoting political inclusion and social justice.

REFERENCES

AMAZONAS [ Links ]

DIARIO DE MANÁOS [ Links ]

O PARÁ [ Links ]

REPUBLICA [ Links ]

BAHIA ILLUSTRADA [ Links ]

REFERENCES

AMAZONAS. Diario Official. Manáos, de 1894 a 1899. [ Links ]

PARÁ. A instrucção publica na administração do Exmo. Sr. Dr. José Paes de Carvalho, Governador do Estado. Pará / Milano. J. Chiatti & C. Editores, 1900. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, Virgílio Cardoso de. O Instituto Cívico-Juridico. Artigos publicados na Província do Pará. Pará: Typ. e Encad. de Pinto Barbosa & C., 1898. [ Links ]

VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, Virgílio Cardoso de. Discurso - Programma. Pronunciado pelo Director Geral da Instrucção Publica, Dr Virgílio Cardoso de Virgílio Cardoso, perante o Conselho Superior na reunião ordinaria de 30 de setembro de 1899. In: Revista A Escola, anno I, num 1, 3 de maio de 1900-A. [ Links ]

VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, Virgílio Cardoso de. Leitura Civica: Apontamentos históricos e notícia sobre a Constituição Federal destinados às escolas publicas. 2ª ed. Belém: Livraria Moderna, 1900-B. [ Links ]

VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, Virgílio Cardoso de. A Patria Brazileira: Leitura escolar illustrada com 260 gravuras. Bruxellas: Constant Gouweloos & Cia., 1903. [ Links ]

VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, Virgílio Cardoso de. Nossa Patria: Pequena Encyclopedia Nacional para uso das escólas brazileiras. 3ª ed. (Da antiga “A Pátria Brasileira” inteiramente refundida e ampliada. Paris/Lisboa: Typographia Aillaud, 1908. [ Links ]

VIRGÍLIO CARDOSO, Virgílio Cardoso de. Meu Lar. Belém: Livraria Escolar, 1931. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

BLAKE, Augusto Victorino Alves Sacramento. Diccionario Bibliographico Brazileiro. v.2 e v.7. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1893 [ Links ]

RELATÓRIO apresentado à Congregação do Instituto Civico-Juridico “Paes de CarvalhoIn: CARDOSO, Virgílio. Leitura Civica. Apontamentos historicos e noticia sobre a Constituição Federal destinados às escolas publicas. 2. Ed. Livraria Moderna, 1900. [ Links ]

FUNDAÇÃO GETÚLIO VARGAS. JARDIM, Silva. Líder Republicano. CPDOC. Disponível em: https://cpdoc.fgv.br/sites/default/files/verbetes/primeira-republica/JARDIM,%20Silva.pdf. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

BOURDIEU, P. A ilusão biográfica. In: FERREIRA, M. (Org.). Usos e abusos da história oral. Rio de Janeiro: Editora da Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 1996. p. 183‑91. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. O poder simbólico. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand do Brasil, 1998. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, J.M. Radicalismo e republicanismo. In: CARVALHO, José Murilo de e NEVES, Lúcia Maria Bastos Pereira das. (orgs.) Repensando o Brasil do Oitocentos: cidadania, política e liberdade. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2009, p.19-48. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, J.M. República, democracia e federalismo Brasil, 1870-1891. Varia Historia, Belo Horizonte, v.27, n.45, p.141-157, jan/jun. 2011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-87752011000100007 [ Links ]

COSTA, M.B.C; MENEZES NETO, G.M. Livros escolares e provas de “portuguez”: formação civilizadora na instrução pública do Pará (1898-1912). Revista Latino-Americana de História, v.5, n.15, p.69-90, jul. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4013/rlah.v5i15.722 [ Links ]

GRAMSCI, A. Cadernos do cárcere. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1999. [ Links ]

KOSELLECK, R. Futuro passado: contribuições à semântica dos tempos históricos. Contraponto/PUC-Rio, 2006. [ Links ]

LAJOLO, M.; ZILBERMAN, R. A formação da leitura no Brasil. São Paulo: Ed. UNESP, 2019. [ Links ]

MOURÃO, L. Memórias da indústria Paraense. Anais do XII Congresso Brasileiro de História Econômica & 13ª Conferência Internacional de História de Empresas. Associação Brasileira de Pesquisadores em História Econômica. Niterói, agosto de 2017. Acessível em: http://www.abphe.org.br/uploads/ABPHE%202017/10%20Mem%C3%B3rias%20da%20ind%C3%BAstria%20Paraense.pdf. Acesso em: 27 maio. 2022. [ Links ]

NAGLE, J. Educação e sociedade na primeira república. São Paulo: EPU, 1974. [ Links ]

SCHUELER, A.F.M.; MAGALDI, A.M.B.M. Educação escolar na Primeira República: memória, história e perspectivas de pesquisa. Tempo, v.13, n.26, p.32-55. 2009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-77042009000100003. [ Links ]

SKIDMORE, T.E. Preto no branco: raça e nacionalidade no pensamento brasileiro (1870-1930). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2012. [ Links ]

SMEYERS, P.; DEPAEPE, M. Educational Research: the educationalization of social problems. Dordrecht, Holanda: Springer, 2008. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9724-9. [ Links ]

SOUZA, M. Amazônia e modernidade. Estudos Avançados. v.16, n.45. 2002. Disponível em em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/ea/v16n45/v16n45a03.pdf. Acesso em: 20 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, C.E. Contextualismo linguístico: contexto histórico, pressupostos teóricos e contribuições para a escrita da História da Educação. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v.17, p.31-55, 2017. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v17n3.922. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, C.E. Erasmo Pilotto: identidade, engajamento político e crenças dos intelectuais vinculados ao campo educacional no Brasil. In: LEITE, J.L.; ALVES, C. (Org.), Intelectuais e História da Educação no Brasil: Poder, Cultura e Políticas. Vitória: EDUFES, 2011. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, C.E. Independência, democracia e formação no discurso da Associação Brasileira de Educação: 1927-1945. Revista História da Educação, v.25, p.106-131, 2021. Disponível em: https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/asphe/article/view/106131. Acesso em: 27 maio. 2022. [ Links ]

2We understand the intellectual trajectory as formulated by Bourdieu, in the classic argument about biographical illusion. Illusory biographies for they impose an arbitrary rationalization on what was lived, in order to produce a unique, coherent being, who is moved, in an unshakable way, by a purpose of life. According to Bourdieu, the trajectory must be understood as a “series of positions successively occupied by the same agent (or the same group) in a space [..] subject to incessant transformations” (BOURDIEU, 1996, p.189).

3We chose to refer to our character as Virgílio Cardoso because that was how he became known in the political and educational circles of the period.

4The main references for the analysis of linguistic contextualism and the history of concepts are the works and ideas of Quentin Skinner and Reinhard Koselleck respectively.

5Some of his works are: “Ligeiros traços” and “Leitura amena”, from 1892; “O Instituto cívico-juridico: artigos publicados n’A Província do Pará”, from 1898; “Os próprios nacionaes: justificação constitucional do direito que aos estados assiste sobre os antigos proprios nacionaes”, from 1898; “Discurso. 2ª Conferência Cívica”, from 1900; “Affonso Celso contra Affonso Celso: contradicta historia ao oito annos de parlamento”, 1902; “Apontamentos históricos e notícia sobre a Constituição Federal destinados ás escolas publicas”, from 1902 (?); “A Patria Brazileira: Leitura escolar illustrada com 260 gravuras”, from 1903; “A Terra Brasileira: Chorografia dos Estados Unidos do Brazil para uso das escolas primarias brazilairas”, from 1907; “A terra: Curso primário de Geographia e Cosmographia Ornado de 14 mappas e 59 gravuras”, from 1908; “Nossa Pátria: Pequena Encyclopedia Nacional para uso das escolas brasileiras”, de 1908; e “Meu lar: narrativa romântica, poético - ilustrada, voltada a fins cívicopiedosos”, undated.

6In the Diccionario Bibliographico Brazileiro, by Augusto Blake (1893), one reads that Climerio Cardoso de Oliveira was born in 1854, in Bahia and was “doctor of medicine by the faculty of his province, and professor of the obstetric clinic chair” (p. 126). He also wrote works such as technical books and literature.

7Silva Jardim was seen as an unmoderated politician and because of his stance considered inflexible, he was marginalized even within the Republican Party to the point that, when the Republic was installed, he was gradually removed from the government. According to Silva Jardim, as stated in his memoirs, the Minister of War explained him that he was not informed of the conspiracy against the monarchy because [the Minister of War] had information that classified him as a 'bloodthirsty republican', and the movement was intended to be peaceful (FGV/CPDOC, nd., np).

8Pierre Bourdieu's concept of field does not constitute a central heuristic apparatus in this analysis, however, when we use the expression we are supported by the Bourdeusian idea that defines the field as a social space of relations, where the criteria for naming, classification and social distinction are established/imposed. Bourdieu emphasizes the relations between the fields but also sustains the relative autonomy of these spaces. For an analysis of Bourdieu's main concepts, see O poder simbólico.

9On the concepts of space of experience and horizon of expectations, see Reinhard Koselleck, Futuro passado: contribuições à semântica dos tempos históricos, especially the chapter: Espaço de experiência e horizonte e de expectativa: duas categorias históricas, p.305-329.

10The refered Congress was created in Belém by Decree 874, of 07/11/1900, which “Establishes in this capital a ‘Pedagogical Congress’ and approves its Rules of Procedure”.

11Among the newspapers in circulation at the time, we highlight: Folha do Norte, O Estado do Pará and A República, linked to the Laurista group; and Província do Pará and O Jornal, linked to the Lemistas.

13In the 1920s, the most evident sign of the strengthening of the educational movement was the creation of the Association of Brazilian Education, in 1924. This association brought together the Brazilian intellectual elite and enjoyed great prestige before society and the State. The same dismay, felt by Virgílio Cardoso concerning the ineffectiveness of republication governments, was revived by the generation of 1920 in the movement entitled "republicanization of the republic”, which had as one of its exponents Vicente Licínio Cardoso, organizer of the collection, À margem da história da republic, which aimed to voice the criticism about the paths adopted by republican politics.

14Language games, according to the appropriation of linguistic contextualism, of the theory of the so-called second Wittgenstein, are situations of contextualized communication, in time and space, and registered in empirical sources, capable of being treated historically.

15NVivo is qualitative data analysis software produced by QSR International. NVivo helps researchers organize and analyze unstructured or qualitative data such as interviews, open survey responses, journal articles, social media, and web content where deep levels of analysis are needed on small or large volumes of data.

Received: June 13, 2022; Accepted: August 20, 2022

texto en

texto en