Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de História da Educação

versão On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-166

Artigos

Gabriela Mistral and her “counter-bomb”: educative messages for peace1

1Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana (Brasil). carola.vasquez@unila.edu.br

Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957) was a Chilean teacher, writer and intellectual. She was counsuless for Chile in Brazil from 1940 to 1945. Marked by contexts of war and dictatorships, locally and externally, she a number of pedagogical messages which I interprete through the image of the counterbomb, a concept she creates to discuss a peace born out of the most intimate essences of being and which allows a reading of herself as an author writing from inside a trench. Through the use of images and metaphors and a resource to think reality in distinct ways, she made invitations for the creation of different readings of the world, and by using narratives, she counted livid reports and stories of experiences and lessons she taught of the difficult times in place. Through the analysis of some of her report, a genuine Mistralean genre, I attempt understand the pedagogical meaning of her work and analyze the lessons she gave her imagined community of fellow Americans, transmiting experiences in hope of bringing Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking Americans closer to one another and, through writing, struggle for peace.

Keywords: Gabriela Mistral; Educative messages; Reports

Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957), professora, escritora e intelectual chilena atuou como consulesa do Chile no Brasil entre os anos 1940 e 1945. Nesse período, marcada pelos contextos de guerra e ditadura que se viviam no País e no mundo, elaborou uma série de mensagens educativas, que interpretaremos a partir da imagem de contrabomba, conceito elaborado por ela para pensar a paz edificada desde as essências mais íntimas do ser e que permite como figura metafórica ler a autora desde uma trincheira, como ela mesma se sentia como escritora. Utilizando imagens e metáforas como recurso para pensar a realidade de uma outra forma, enviou convites para a criação de leituras do mundo e, por meio da narração, transmitiu relatos e contos vivos que continham suas experiências e ensinamentos para refletir, nos difíceis momentos que se viviam. Por meio da análise de alguns de seus Recados, gênero de escrita mistraliana, tentaremos compreendê-la como professora e analisar as mensagens que enviou a sua comunidade imaginada de americanos (as), transmitindo experiências para aproximar culturalmente os países da América Hispânica e Lusófona e lutando, por meio de sua escrita, para conseguir a paz.

Palavras-chave: Gabriela Mistral; Mensagens educativas; Recados

Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957), profesora, escritora e intelectual chilena se desempeñó como cónsul de Chile en Brasil entre los años 1940 y 1945. En ese período, marcada por los contextos de guerra y dictadura que se vivían en el país y en el mundo, elaboró una serie de mensajes educativos, que interpretaremos a partir de la imagen de contrabomba, concepto elaborado por ella para pensar la paz edificada desde las esencias más íntimas del ser y que permite como figura metafórica leer a la autora desde una trinchera, como ella misma se sentía como escritora. Utilizando imágenes y metáforas como recurso para pensar la realidad de otra forma, envió invitaciones para la creación de lecturas del mundo y, por medio de la narración, transmitió relatos y cuentos vivos que contenían sus experiencias y enseñanzas para reflexionar en los difíciles momentos que se vivían. Por medio del análisis del algunos de sus Recados, género de escritura mistraliana, intentaremos comprenderla como profesora y analizar los mensajes que envió a su comunidad imaginada de americanos (as), transmitiendo experiencias para aproximar culturalmente a los países de la América hispana y lusófona y luchando, por medio de su escritura, para conseguir la paz.

Palabras clave: Gabriela Mistral; Mensajes educativos; Recados

Multiplicity of identities in Mistral: Introductory notes

Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957) was a Chilean professor, writer and scholar who worked as the Consul of Chile in Brazil, from 1940 to 1945. Although she worked in countless areas throughout her life, Mistral combined her different skills towards education and pedagogy. In such activities, her discourse and actions can be recognized as rhizomatic, as they account for a multiplicity of interests, possible references, and commitments. The rhizomatic form might

be biographically suggestive since it has some methodological implications that involve multiplicity of identity. Any point of a rhizome can be connected to any other, which induces a predominance of the principles of heterogeneity and connection (DOSSE, 2009, p. 407).

According to Ana Pizarro (2005, p. 19-20), during her stay in Brazil, Mistral's speeches demonstrated her intention to link the Portuguese-American domain with her own Hispanic-American domain. At that time, as well as being new, this was essential for her and enriched her discourse. Also according to Pizarro, for Mistral, this idea of bond is related to the notion of representation, which would meet the need for validation of her discourse at a time when it was not easy for a woman to be a scholar (p. 20).

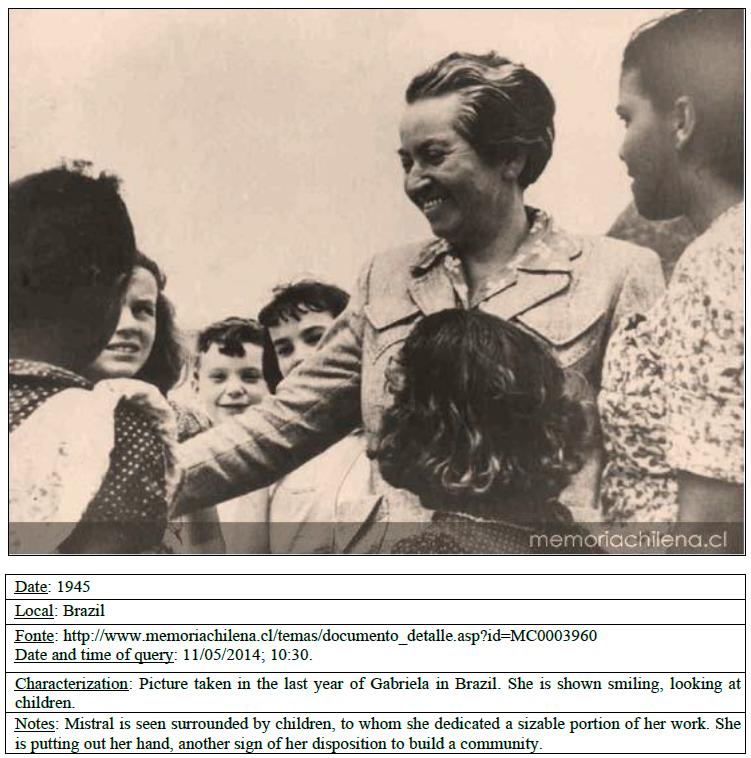

According to Clarice Nunes (2009, p. 107): "Such prose made Gabriela into a writer committed to the world in which she lived, to places she visited, people she met, the languages in which she expressed herself". This is clear in Mistral's Nobel Prize acceptance speech, in 1945, while living in Brazil2. At that time, she declared that she felt the direct voice of the poets of her own race and the indirect voice of Hispanic and Portuguese poets.

Por una venturanza que me sobrepasa, soy en este momento la voz directa de los poetas de mi raza y la indirecta de las muy nobles lenguas española y portuguesa. Ambas se alegran de haber sido invitadas al convivio de la vida nórdica, toda ella asistida por su folklore y su poesía milenarias (MISTRAL, 1945).

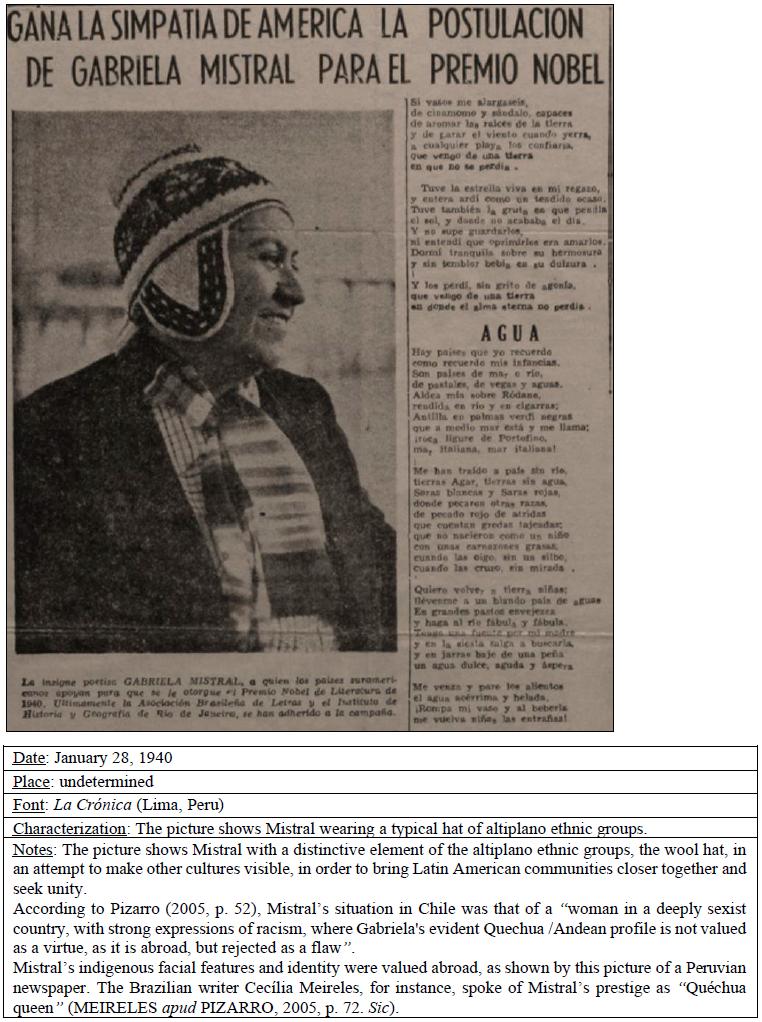

On the other hand, Mistral's work during her stay in Brazil gained visibility through the "investiture" of authority she received from the movement in support of her nomination for the Nobel Prize for literature. At a time of crisis, due to the war which devastated Europe and the world, and the dictatorship in Brazil, many American countries, through their scholars, governments, and Academies of Literature, recognized the author and disseminated her speeches.

For Ana Pizarro, one of Gabriela Mistral's concerns regarding Brazil was to contribute to making Hispano-America known. For this reason, she established pedagogical relationships with the Ministry of Chile4: "conveying lines of behavior, and attitudes for a modern cultural policy" (PIZARRO, 2005, p. 30), which also extended to her writing addressed to her imagined community of Americans (ANDERSON, 2008).

The idea of an imagined community, developed by Anderson, allows us to understand how Mistral viewed Latin America and wrote as if she viewed Americanity as the Americans themselves. The objective was to unite this imagined community by means of the Recados (Messages). Sending such texts would be a way to educate, viewed within a relationship between her own trajectory and the projects with which she dialogued (NUNES, 2009, p. 8). At the same time, following the understanding of Pizarro (2005), in her analysis of the pedagogical relationship of Mistral with the Chilean Ministry, it is possible to observe that the relationship that Mistral established with her readers, as an imagined community, was also pedagogical, as she conveyed experiences, behavior trends, attitudes and values through her Recados, to bring Spanish and Portuguese-speaking American countries culturally closer, promoting other ways for reading the world and building a culture of peace.

Messages and experiences conveyed

With her Recados Gabriela Mistral developed a particular type of writing; texts both in prose and verse published between 1919 and 1952, entitled: Commitments, Messages, Notes, Comments, Calls, Words, Speeches; or simply beginning with phrases such as: Something about..., About..., Response to ..., Letter to... In her Recados, Mistral criticizes, congratulates, warns, and assigns tasks to readers, always with an intimate tone, full of emotion, familiar, complimentary, sometimes even reproaching (GRANDÓN, 2009).

The Recados published while Mistral lived in Brazil will be the sources analyzed in the present work. They will be considered "educational messages", in the pedagogical relationship she built with her imagined community.

According to Benjamin's interpretation (1994, p. 200), the Recados are understood as advice, in the sense that "to advise is not to answer a question but rather to make a suggestion about the continuation of a story being narrated". At a time of crisis produced by the dictatorship in Brazil, and the Second World War, which affected the world, I consider that Mistral thought that her narrations might be useful in the Benjaminian sense, as they represented moral teaching, practical suggestions, proverbs, or rules for life (BENJAMIN, 1994, p. 200). Therefore the Recados would also serve to keep the reader company, for "whoever hears a story is in the company of the narrator; even those who read it, enjoy their company" (p. 213).

Considering Mistral as a narrator is equivalent to saying that she is able to give advice, in many cases, as a mentor,

as they can use experience gathered throughout an entire life (a life that includes not only their own experiences, but largely, the experiences of others. The narrator assimilates onto they most intimate substance what they know through hearsay). Their gift is to be able to narrate their life; their dignity, to tell it wholeheartedly. The narrator is the person who lets the faint light of their narration completely consume the flame of their life. Hence the incomparable atmosphere that surrounds the narrator (BENJAMIN, 1994, p. 221, original emphasis).

Revisiting this idea of an atmosphere that surrounds the narrator, Mistral's efforts to build educational messages through her activities as a narrator are notable, in which: "The soul, the eyes and hands are thus inscribed in the same realm. By interacting, they define a praxis" (BENJAMIN, 1994, p. 220) and, concomitantly, by disseminating her writings in newspapers, the author simultaneously established a relationship with her readers, simultaneously hoping that the messages would be read by others. Therefore, reaffirming the idea of imagined community (ANDERSON, 2008), and hoping that, by means of the pedagogical relationship that was established, the experiences would foster transformations in the behavior, attitudes, and values of readers, striving for peace.

For authors such as Adolfo Castañón (2010, p. XLII), Mistral is "a herald, an author of articles and letters, messages and impressions that she publishes in newspapers similarly to someone sharpening their sword in public before giving themselves over to the most secret and intimate battles of poetry”. However, Mistral's works of prose are not poetry essays; they are a distinct record, in which the author takes a stance, thus, presenting her resistance, because

se trata de un proceso de transformación de territorios donde el desplazamiento del cuerpo fuera de las fronteras “nacionales” de la tierra impulsa un movimiento que tiene como resultado final un artefacto público (los libros se “publican”) con valor político y de mercado. De la circulación material privada (si se entiende el cuerpo en este contexto como el espacio más privado que se posee) se transita, finalmente, a una circulación pública y monetaria (abierta a todo aquel que tenga lo único necesario para participar en ella: dinero). El sentido de lo privado se desterritorializa así para territorializar espacios públicos y a través de éstos al lector. Dentro de este proceso fluctual de territorializaciones y desterritorializaciones puesto en marcha a partir del desplazamiento, la única huella concreta es el texto: territorialización/desterritorialización de una tierra imaginaria llamada Chile (FALABELLA, 1997, p. 87, original emphasis).

This territorialization / deterritorialization process would not only take place in Chile, but also in Latin America as a whole, both understood by the author as lands imagined. Mistral's contribution to newspapers was significant, as it enabled the dissemination of her work and represented a subversive exercise, since, to convey her experience, which had signs of orality, ancient and traditional, the author occupied a space considered as one of the main instruments of advanced capitalism.

Throughout her life, Gabriela Mistral wrote for many newspapers and periodicals, as these were the spaces for socializing and promoting culture to the interior of Latin America. According to Nunes (2011, p. 163), it was also a space that allowed some women to assert themselves as academics, as "it was within the environment of journalism that some teachers took their first steps to become literary women".

Many of the newspapers for which Mistral wrote contemplated the theme of "Americanity"; among which: Pensamento de América (Brazil), Revista de América (Colombia), Repertorio americano (Costa Rica), Cuadernos americanos (Colombia), Palabra americana (Peru) and Revista Sur (Argentina). In Chile, Mistral published most of her texts in El Mercurio, a conservative newspaper founded in Santiago in 1900. That newspaper has represented an important center of power throughout its history5.

Mistral contributed to El Mercurio for many years and established a very close bond with it; she even referred to it as my newspaper. She also dedicated one of her Recados (MISTRAL, 1940) to honor Carlos Silva Vildósola6, one of its directors, whom she considered an master of journalism in the country. About the publication of her Recados in that newspaper, Mistral took it as a special request, through which she expressed her commitments to her people: "I ask my newspaper to allow me [to write], every fortnight, this sort of letter to many... harsh and tender assignments for my people: hard because of the impetus to be heard and tender because of the love for them” (MISTRAL apud PÉREZ, 2005, p. 11-12, my emphasis).

It is worth pointing out how Mistral spoke about the different emotions that Recados embody, the harshness and sweetness, understood in view of her impulse to make herself heard, and by her love of her people, in the context of the pedagogical relationship she established with her readers.

The significant participation of Mistral in wide-circulation newspapers is part of her commitment to establishing a pedagogical relationship with her imagined community, as a way of educating for a culture of peace, in times of totalitarianism and war. According to Said's analysis of north American newspapers, it can be said that her writing also resonated as a result of the authority and legitimacy of the newspapers in which her texts were published. According to Said (2005, p. 40):

In the United States, the greater the penetration and power of a newspaper, the more authoritative its repercussion will be, and the more closely it will identify itself with a broader sense of community rather than a mere group of professional writers and readers. The difference between a tabloid and the New York Times is that the New York Times aspires to be (and is generally considered) the most accepted newspaper, whose editorials reflect not only the views of a small group of people, but also, supposedly, the perceived truth of and for an entire nation. On the other hand, the role of a tabloid is to attract immediate attention through sensationalistic articles and flashy headlines. Any New York Times article brings a somber authority, suggesting vast research, careful meditation, and thoughtful judgment. For sure, the editorial use of "we" refers directly to the editors themselves, but at the same time it suggests a collective national identity: "we, the people of the United States."

On the counter-bomb and the search for peace

During her stay in Brazil, Mistral spoke about the war and the resulting divide in which the world was immersed. She tried to attract the attention of Americans to that issue by means of her Recados as educational messages, which we will interpret based on the image of the counter-bomb, a concept she developed to contemplate peace, built from the most intimate essence of the soul, and which allows us to metaphorically view the author on a trench, as she herself felt as a writer.

Using images and metaphors as a resource to contemplate reality in a different light, the author sent invitations for the creation of worldviews, and, through narration, she conveyed live reports and tales that contained her experiences and teachings, to foster reflection and educate within a culture of peace.

Methodologically, the use of images and metaphors represents a possibility to look beyond traditional views, uncovering interpretative keys in Mistral’s own work. About the metaphors, Elsie Rockwell (2018, p. 455) wondered:

¿Qué encontraremos si viajamos con estas metáforas hacia rumbos desconocidos? Seguramente muchas más contradicciones y tensiones que cuando se presuponen formas sistémicas y estructuradas para organizar la evidencia del pasado. Encontraríamos situaciones que desbaratan la consistencia de muchas historias oficiales de la educación.

According to Rockwell’s reflections, metaphors are a key to interpret the past, as they allow people to break from the consistency of many instances of official history, identifying contradictions and tensions. In the case of Mistral, they would allow, for example, new fertile readings that would go beyond the official interpretation of her work, so rhizomatic as the multiplicity of identities presented at the start of this text.

In one of her texts, dedicated to Luisa Luisi, a Uruguayan modernist poet, pedagogue, and literary critic, Mistral expresses her concern and affliction for the times they were living and the situation of America. While, using the image of symbolic motherhood she portrayed Luisi as a protector, with the intent of sensitizing and leading to reflection:

Acaso le ha ahorrado también el Dios Padre vigilante ver a los criollos locos acarrear hacia la América, ¡con qué diligencia! la operación carnicera del Viejo Mundo y de ello no verá sangrientas las arenas del Sur y no oirá los discursos embusteros con los cuales quieren convencer al pueblo inocente y grandullón los demagogos de los dos frentes, para echarlo de bruces a la entrega monda y oronda de todo lo nuestro: costumbre, instituciones y dulzura de vivir.

El incendio de Europa que camina con lenguas de fuego por sobre la marea atlántica, me enrojece mis ojos sobre la página que escribo y me arden los lagrimales a esta hora, cuando deberían sólo llorar a Luisa muerta. Ella recibió la gracia de morir a tiempo de irse entera y limpia, antes de la división en que vamos a entrar por gracia de Caribdis y Scilla, y en el cual los hermanos ya no querrán reconocer a la madre una, a la América Raquel de la que venimos y que es nuestro único deber.

Vele, ella la gran desvelada, la gran señora alerta, y suelte sobre nosotros alguna de sus anchas instituciones, a fin de atajarnos. Al cabo está en el reino de la Unidad y ya sabe, para siempre, lo que nosotros, embriagados de pluralidad, no queremos aprender, duros de cerviz y turbios de confusión.

La que fue hermana, seános ahora un poco madre y nos haga mirarnos cara a cara y en silencio, un momento antes de que echemos en la pelea. Un rato, nada más, de los ojos puestos en los ojos, una pausa de mirada fija, y el nombre de ella en la boca. Hagamos esto, amigos míos, ustedes, desde allá; yo desde Brasil, hagámoslo en gracia del amor de Luisa Luisi (MISTRAL, 1999a, p. 268-269).

In 1941, Mistral also spoke about how Europe perceived America, and how America was viewed as divided:

La Europa que hizo todas las conquistas, que removió siempre el mar y la tierra, antes buscando las materias “preciosas” y hoy las materias tout court, hoy no habla de nosotros como pueblo sino como de meras “fuentes” o de cornucopias llenas a rebosar. Aunque Europa nos dirija “todavía” discursos liberales con mira a sosegarnos, la zalema sólo retarda un poco su avidez de fuego. Para el continente padre del racimo no tenemos nosotros semblante racial, honorable, y tampoco espinazo uno del león; somos razas quebradizas por aisladas (MISTRAL, 2002a, p. 174, original emphasis).

In this context, Mistral’s Recados communicate optimistic messages, in which the author conveyed hope, focusing on the future, and children, to engender a path out of conflict. These feelings can be observed when she speaks to Fedor Ganz:

Su inteligencia - de las más afiladas entre las que conozco - le estorba para salvarse con los únicos goces de esta hora, que tal vez sean los míos: escarbar unos metros de tierra, sembrar, regar y expurgar de insectos los tallitos que suben en mi jardín; quiero decir, hacer jardín y pensar en los niños que nacen, poniendo en ellos unas migajas de esperanzas (MISTRAL, 2002a, p. 196-197).

For Mistral, children represented hope, a magical element that would enable the achievement of unity among countries. In one of her texts, she points out:

divididos como nunca lo estuvimos antes, tajados en dos orillas que se miran sin oírse, tal vez sólo nos quede esta isla salubre y limpia de nuestra infancia. Es la tierra de la reconciliación inmediata y el acallamiento de nuestra discusión impenitente. La concordia puede hacerse en este punto mágico donde se crea cualquier violencia. La infancia pudiese unificarnos las banderías y convertirnos a lo concreto, poniéndonos a un trabajo realista y libre del fraude criollo (MISTRAL, 2002b, p.174).

While in Brazil, Mistral defended Americanism7, understood as a possibility to reflect on the violence and death which was ravaging the world. According to Trabucco Valenzuela (2016, p. 261), “the entirety of Mistral’s reasoning in favor of Americanism is linked to political and social movements that were increasingly gaining terrain in the first decades of the 20th century”. The author further ponders that Americanism represents "a struggle for citizenship, a struggle made through love of one's neighbor, of a markedly Christian character; love, respect, and fidelity to America" (1998, p. 55).

In this sense, an element that characterized Gabriela Mistral's work was her association with Latin American women's networks and leagues, which was also an expression of the rhizomatic construction of her work. In line with Ana Pizarro, and revisiting the concept of invisible college developed by the author, we can recognize that these women were part of:

un grupo articulado virtualmente en diálogo de lecturas, mudo, escrito y también realizado a través de encuentros. Un grupo disperso por el continente que tiene una postura común, en la diversidad de sus discursos frente al espacio de la mujer escritora y frente a la sensibilidad estética de los primeros decenios del siglo en América Latina. Este grupo-o red- condiciona internamente la potenciación de los discursos individuales y marca en su conjunto un momento primero, pero definitivo a nivel latinoamericano, del discurso de la mujer intelectual (PIZARRO, 2004, p. 175-176).

In Brazil, Mistral engaged with different writers, both men and women. Among the women, Cecilia Meireles and Henriqueta Lisboa stand out as "names that undoubtedly converge onto Mistral's poetry, both in formal and thematic aspects" (TRABUCCO VALENZUELA, 2001, p. 145). This relationship can be observed in a text written by Mistral to address the female literary scene in Brazil, recognizing Brazilian women writers as moral reserves, talking about peace, proposing the image of a counter-bomb to contemplate peace:

Forgive me if, at the moment of the atomic bomb, I extensively praise our women. In spite of the “phenomenal” time that distracts so many people or leaves them in elated “catharsis;” it seems to me that we must start contemplating... the “counter-bomb,” i.e., peace built from the crux of our souls.

The atomic bomb, the panic bomb, will not cure us from hate, greed, or homicidal madness.

One should note the elevation and pervasion of humanity that lies in the works of the women mentioned. I believe they constitute considerable moral reserves of paramount value to Brazil. They can provide many other benefits as well. It is worth adding our faint hope to these forces, and with them, to appease a little the pessimism and alarm, which the Iberian race experiments right now (MISTRAL apud BENEVIDES, 1945, my emphasis. Sic).

This image of the counter-bomb as peace built from the crux of the soul is germane to Mistral’s view on education and pedagogy, marked by Americanism, which foster cultural convergence among Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries as a metaphor of the resistance she promoted, which would be acquired by means of mutual knowledge, for example:

As far as the formation of a common culture is concerned, I believe the future of the Pacific and Andean unity is assured. The mission still at hand, which must be conducted immediately, is the one we have already dealt with: book trade and the expansion of the two South American languages (MISTRAL, 1941b, p. 11).

As the previous quote indicates, some of the strategies that Mistral considered significant to achieve the union of cultures in America were the exchange of books and the expansion of the two languages. She even spoke of the need to make the study of both languages (Spanish and Portuguese) compulsory; and for conferences and for the propagation of aspects of regional life through the press (MISTRAL, 1941b).

In an interview given in 1941, a journalist from Revista Diretrizes asked Mistral what she had done to bring the cultures together. Her answer was:

Any charge I may receive to help solve our Latin American problem will be an immense pleasure for me. Not long ago, I started to send you some Notas brasileiras (Brazilian Notes) every fortnight. They are published in daily newspapers in Chile, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela, which you will read later. They are a modest and somewhat sparse sample of an enormous Brazil that no one can claim to cover.

I send passages on geography, flora and fauna, education news and, sometimes, a poem or a text in prose by a Brazilian writer. As you can see, I have taken my place in the trenches with great eagerness and no other pretension than that of an ordinary intellectual worker who takes her place and wishes to fulfill her obligation (MISTRAL, 1941b, my emphasis).

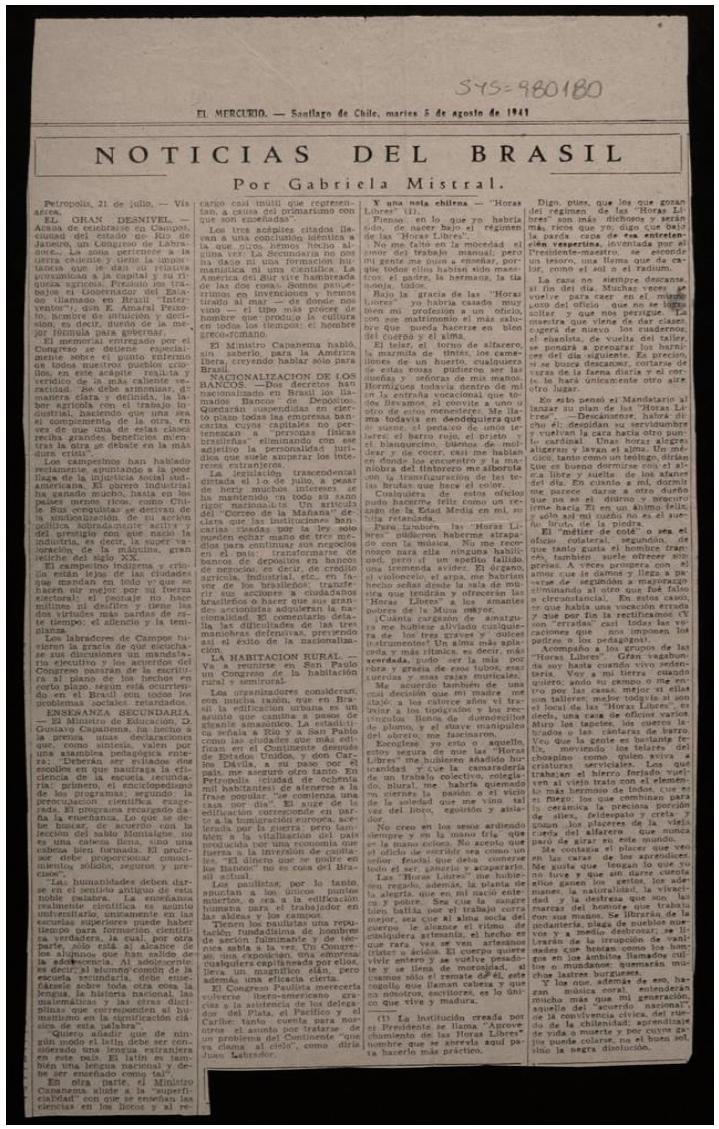

In this excerpt, when using the image of a trench, the author views herself as a fighter; as a committed intellectual worker. We also see that she understands her literary work as a service that disseminates information that contains experiences, in the Benjaminian sense, which in the present text are understood as educational messages. An example of this are her “Notas brasileiras,” “Notícias brasileiras” ou “Noticias del Brasil,” in which she spoke about education, rural housing, and peasant life, among other things.

Font: El Mercurio, Santiago, August 5, 1941a

Picture 2: “Noticias del Brasil” - Gabriela Mistral in the Chilean press

While living in Brasil, Mistral published several texts about the bond among cultures and stressed the importance of the elements already mentioned herein, to achieve proximity. Among such titles, are: “Coincidencias y disidencias entre las Américas,” “El divorcio lingüístico de nuestra América,” “La amistad interamericana por el libro,” “Dos culturas: Brasil y América,” among others.

Accomplishing this unity was a mission for Gabriela Mistral. She believed that this concern was not hers alone, but also a concern of her fellow writers:

Los escritores, digo, somos los hispanoamericanos en función cotidiana de unidad. Vemos mejor que los otros el absurdo de la secesión y es que nunca abandonamos, a causa del propio oficio, la vida continental, y de que la heterodoxia nunca valió para nuestra familia. Y es también que cada libro que se lee en nuestro país, tanto como en los otros, nos hace presente la comunidad y nos remece fuertemente con ella (MISTRAL, 1999b, p. 149).

At that time, contemplating unity, Mistral sent out invitations for a collective singing (canto)8, expecting that the sound would unite different American voices to achieve peace at a time of war:

La época es harto propicia a una protección subida de la música colectiva. La individualista está de baja y en poco más parecerá un vicio de droga o un aperitivo burgués. El pueblo está tomando posesión del aire y quiere un reparto frecuente de pan musical (MISTRAL, 2004b, p. 122).

About pedagogy and narration

As previously indicated, Mistral developed a concept of education whose purpose was to achieve peace, which she also related to pedagogy, an activity that always occupied a prominent place in her concerns and was connected to her other work, indicating the multiplicity of identities already described. Pedagogy was one of her first crafts, which she had practiced since childhood in her native Chile. In her own words: “The first craft, even when abandoned, intrudes onto the next, creeps into conversation, and even sneaks up on your sleep and asserts it rights, and we must give into nostalgic cordiality” (MISTRAL, 1945, p. 69).

As formerly mentioned, Mistral devised some strategies to achieve union among American cultures and therefore achieve peace. Some of these strategies consisted of the exchange of books, expansion of both languages, lectures, and press publications regarding aspects of regional life. On the other hand, the author also referred to the work of teachers, educational practices, and the need to delight children in learning the geography of their country and their continent:

Los profesores sudamericanos que deben enseñar a los niños a ver y sentir el cuerpo patrio cuando escriben manuales piensan tanto en su aprobación por el ilustre Consejo, que no hay modo de que se atrevan como usted a escribir metafóricamente y a entregar un país que aparezca tan vivo como un hermoso animal; el que usted atrapó en sus ojos, alienta y quema de vivo… (MISTRAL, 2004a, p. 61).

As the author highlights in the previous quote, to achieve continental proximity, South American teachers have the collective duty of showing living countries. It is also interesting to observe how the author comments on the writing process of teachers, who, in an effort to obtain approval for publication, do not dare write metaphorically, thereby erasing the life that countries embody. As previously stated, metaphor as resource and wealth represents an interpretive key to Mistral’s work.

With this objective, one of the elements that Mistral considered important in educational practice was narration, which would produce enchantment and magic, and which constituted part of her tradition as a narrator (BENJAMIN, 1994). In a 1929 text, Mistral recognized the importance of narration when she criticized the condition of pedagogical practices:

Poco toman en cuenta en las Normales para la valorización de un maestro, poco se la estiman si la tiene y menos se la exigen si le falta, esta virtud de buen contar que es cosa mayorazga en la escuela. Lo mismo pasa con las condiciones felices del maestro para hacer jugar a los niños, que constituye una vocación rara y sencillamente preciosa. Lo mismo ocurre con el lote entero de la gracia, dentro del negocio pedagógico. (El filisteísmo vive cómodo en todas partes; pero muy especialmente se ha sentado como patrón en el gremio pedagógico dirigente).

Sin embargo, contar es la mitad de las lecciones; contar es medio horario y medio manejo de los niños, cuando, como en adagio, contar es encantar, con lo cual entra en la magia (MISTRAL, 2017, p. 59, my emphasis).

Above, Mistral talks about Escolas Normais (Teacher-training Vocational Schools). She perceives such environment as responsible for teacher education and points out how what was transmitted to both future teachers and students was defined, by means of inclusion/exclusion games. In this regard, she added: “If I were the principal of one such schools, I would implement a general and regional folklore professorship. In addition - I insist - I would not give the title of teacher to those who did not narrate with agility, joy, freshness and even with some fascination. (MISTRAL, 2017, p. 62, my emphasis). She also highlights the importance of the school board in these curriculum and training definitions.

About narration, Mistral (2017, p. 61) used to say, “We cannot know this by asking a fables technician, that is, a writer, but by remembering who told us, in our childhood, the formidable "happenings" that have floated in our memory for thirty years”. For Trabucco Valenzuela (2001, p. 140), “for Gabriela, the narrator, either in the countryside or in urban centers, is vividly present as a cultural agent, spreading folklore, defined by her as pure beauty, ‘classic above all classics’”. That can be observed in Mistral (2017, 62), when she states that folklore would be the best and most beautiful form of narration, in which the narrator: “must untangle the cluster of fables that has been forming, those with a warm relationship with their environment: everyday fruit, tree, beast or landscape”.

This is what Mistral did as narrator of her land, with her Recados, transmitting the value of regional and local aspects, and advocating their inclusion in teacher education. The presence of folklore and story-telling as a requirement of pedagogical practice, would serve to show the beauty of the American landscape, develop mutual knowledge, and build a culture of peace. An example of that was her concern for geography lessons, a discipline constantly cited in her writing and which she herself taught:

La plaga de autores de textos de geografía no sabe contar por la boca propia ni tiene la hidalguía de citar con largueza las páginas magistrales de los clásicos con que cuenta su ramo. De donde viene ese pueblo feo y monótono que forman los textos de una ciencia que es genuinamente bella, como que es la dueña misma del panorama.

El paisaje americano es una fuente todavía intacta del bello describir y el bello narrar. Ha comenzado hace unos pocos años la tarea Alfonso Reyes con La Visión de Anáhuac, y ese largo trozo, de una maestría de laca china en la descripción, ha de servir como modelo a cada escritor indoamericano. Nuestra obligación primogénita de escritores es entregar a los extraños el paisaje nativo íntegramente y, además, dignamente (MISTRAL, 2017, p. 60).

Some reflections

The time that Gabriela Mistral spent in Brazil was marked by the scenario of war and totalitarianism in which the country and the world were immersed. During that period, she developed a series of educational messages with the marks of Americanism, addressed to her imagined community of Americans, transmitting experiences, and bringing the cultures of Spanish and Portuguese speaking countries in America closer.

Reflecting about her educational messages, in which she used the image of a counter-bomb, a concept she developed to contemplate peace built from the most intimate essence of the soul, allows us to see the resistance she developed to position herself against the violence that was a hallmark of that time. At the same time, viewing a counter-bomb as a metaphorical figure to read Mistral's educational messages is envisioning her in a trench; she saw herself as a writer, as an intellectual worker with the mission of unification, which she also understood as a daily task. Using images and metaphors as resources to contemplate reality differently, the author sent invitations for the creation of perceptions of the world, and, through narration, she transmitted live accounts and tales that contained her experiences and teachings to reflect and educate within a culture of peace.

In the case of Mistral, through her multiplicity of identities, she intended to work for the unification of America and education for peace, disseminating distinct cultural aspects of each country, thus enabling shared knowledge, and the creation of the idea of community through which Americans could think collectively. It is worth pointing out Mistral's use of images and metaphors as a resource to view reality in a different light, as well as an invitation to sensitivity and creativity. She approached narration, transmitting live accounts and tales that contained, at the same time, her experiences, and teachings to reflect upon times of war and authoritarianism and build a culture of peace.

Therefore, Mistral saw women and their work as images of moral reserves and, childhood as the realm of immediate reconciliation, surely to lend prominence to other subjects, other stories, and possibilities of conceiving the much desired peace. The counter-bomb was also a calling to look at ways of connecting that had been excluded and forgotten, but which, in the author's Americanist narrations, begged to be revived.

Recognizing the struggles undertaken by Mistral through her writing also represents a way of reclaiming individuals who conceived a different world in times of conflict. Reading the educational messages of a woman who resisted violence, shared her experiences, and sent us invitations to raise awareness and build unity and a culture of peace can be a possibility to question many of the representations about education and democracy we currently have in our convulsed Latin America. Even today it is possible to recognize the validity of her Recados and reflect about the significance of Gabriela Mistral's counter-bomb.

REFERENCES

ANDERSON, Benedict. Comunidades imaginadas. Reflexões sobre a origem e a difusão do nacionalismo. São Paulo: Cia. das Letras, 2008. [ Links ]

BENEVIDES VIANNA, Solena. O panorama literário feminino no Brasil visto por Gabriela Mistral. Jornal A manhã, Pensamento de América, Rio de Janeiro, 26 de agosto de 1945. [ Links ]

BENJAMIN, Walter. O narrador. In: BENJAMIN, Walter. Magia e técnica, arte e política. Obras Escolhidas. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1994. p. 197-221. [ Links ]

CASTAÑÓN, Adolfo. Semejanzas de Gabriela en voces de Mistral. In: REAL ACADEMIA ESPAÑOLA. Gabriela Mistral en verso y prosa. Antología. Lima: Santillana Ediciones Generales, 2010. [ Links ]

DOSSE, François. O desafio biográfico: escrever uma vida. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2009. [ Links ]

FALABELLA, Soledad. Desierto: territorio, desplazamiento y nostalgia en Poema de Chile de Gabriela Mistral. Revista Chilena de Literatura, Santiago, n. 50, p. 79-96, abr. 1997. [ Links ]

GRANDÓN, Olga. Gabriela Mistral: identidades sexuales, etno-raciales y utópicas. Atenea, Concepción, n.500, p.91-101, 2. sem. 2009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-04622009000200007 [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Carlos Silva Vildósola maestro del periodismo chileno. El Mercurio, Santiago, 10 de novembro de 1940. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Noticias del Brasil. El Mercurio, Santiago, 5 de agosto de 1941, 1941a. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Povo brasileiro é o povo mais agudamente latino do continente, Entrevista com Gabriela Mistral. Revista Diretrizes, Rio de Janeiro, 27 de julho de 1941, 1941b. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Recado sobre un imaginista. In: SCARPA, Roque Esteban (Comp.). Grandeza de los oficios. Santiago: Editorial Andrés Bello, 1979. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Discurso de Gabriela Mistral ante la Academia Sueca al recibir el Premio Nobel de Literatura, el 10 de diciembre de 1945. Disponível em: http://www.uchile.cl/portal/presentacion/historia/grandesfiguras/premiosnobel/8962/discurso-de-gabriela-mistral. Acesso em: 06 out. 2018. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Mensaje sobre Luisa Luisi. In: ZEGERS, Pedro Pablo (Selec.). Gabriela Mistral. Pensamiento feminista. Mujeres y oficios. La tierra tiene la actitud de una mujer. Santiago: RIL Editores, 1999a. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Palabras de la Recolectora. In: VARGAS, Luis (Comp.). Recados para hoy y mañana. Textos inéditos. Santiago: Editorial Sudamericana, 1999b. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Carta prólogo a Fedor Ganz. In: MORALES BENITEZ, Otto (Comp.). Gabriela Mistral. Su prosa y poesía en Colombia. Tomo I. Santafé de Bogotá: Convenio Andrés Bello, 2002a. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Recado sobre el herodismo criollo. In: MORALES BENITEZ, Otto (Comp.). Gabriela Mistral. Su prosa y poesía en Colombia. Tomo I, Santafé de Bogotá: Convenio Andrés Bello, 2002b. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Contadores de patrias: Benjamin Subercaseaux y su libro ‘Chile o una loca geografía’. In: QUEZADA, Jaime (Comp.). Gabriela Mistral. Pensando a Chile. Una tentativa contra lo imposible. Santiago: Publicaciones del Bicentenario, 2004a. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. La música americana de los ‘cuatro huasos’. In: QUEZADA, Jaime (Comp.). Gabriela Mistral. Pensando a Chile. Una tentativa contra lo imposible. Santiago: Publicaciones del Bicentenario, 2004b. [ Links ]

MISTRAL, Gabriela. Contar. In: MISTRAL, Gabriela. Gabriela Mistral. Pasión de enseñar (Pensamiento pedagógico). Valparaíso: Editorial de la Universidad de Valparaíso, 2017. [ Links ]

NUNES, Clarice. (Des) encantos da modernidade pedagógica: uma releitura das trajetórias e da obra de Cecília Meireles (1901-1964) e Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957). Relatório de pesquisa. Niterói, 2009. [ Links ]

NUNES, Clarice. Letras femininas: missão intelectual de professoras jornalistas na imprensa brasileira. In: LEITE, Juçara Luzia; ALVES, Claudia (Orgs.). Intelectuais e história da educação no Brasil: poder, cultura e políticas. Vitória: EDUFES, 2011. [ Links ]

PÉREZ, Floridor (Selección, prólogo y notas). Gabriela Mistral. 50 prosas en El Mercurio 1921-1956. Santiago de Chile: Aguilar Chilena de Ediciones, 2005. [ Links ]

PIZARRO, Ana. El ‘invisible college’. Mujeres escritoras en la primera mitad del siglo XX. Cuadernos de América sin nombre, Alicante, n. 10, p. 163-176, 2004. [ Links ]

PIZARRO, Ana. Gabriela Mistral: El proyecto de Lucila. Santiago: LOM Ediciones; Embajada de Brasil en Chile, 2005. [ Links ]

ROCKWELL, Elsie. Metáforas para encontrar historias inesperadas. In: ARATA, Nicolás et al (Comp.). Vivir entre escuelas: relatos y presencias. Antología esencial. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2018. [ Links ]

SAID, Edward. Representações do intelectual. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2005. [ Links ]

TRABUCCO VALENZUELA, Sandra. Gabriela Mistral e Poema de Chile. 1998. Tese (Doutorado em Letras). Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

TRABUCCO VALENZUELA, Sandra. Gabriela Mistral: A formação da literatura infantil na América Hispânica. Língua e Literatura, São Paulo, n. 27, p. 123-147, 2001-03. DOI: https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2594-5963.lilit.2003.105443 [ Links ]

TRABUCCO VALENZUELA, Sandra. Identidade e nacionalidade: conceitos, desenvolvimento e história. Literartes, São Paulo, n.5, p. 249-269, 2016. [ Links ]

VON SIMSON, Olga. A construção de narrativas orais sugeridas e incentivadas pela visualidade. A conjugação de depoimentos orais e fotografias históricas em pesquisas que visam reconstruir a história do tempo presente. (Texto gentilmente cedido pela autora). [ Links ]

3The photos included herein were analyzed following the model proposed by Professor Olga Von Simson, however with some adaptations in order to suit the needs of this text (VON SIMSON, Olga. The construction of oral narratives suggested and encouraged by visuality. The combination of oral statements and historical photographs in research aimed at reconstructing the history of present time. (Text kindly provided by the author).

5The history of El Mercurio has been quite controversial, due to its influence in different governments and historical events. For example, its participation in the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990) has been widely discussed.

7In this article we understand the concept of americanism and Indoamericanism in Mistral following the view proposed by Trabucco Valenzuela (2016, p. 259) to read the concepts of Latin Americanism, Indigenism and Indo Spanishism of that author. She reveals that they are used “with no fixed criteria, extracting from each of them the ideas that she considers convenient according to the context.”

Received: July 20, 2022; Accepted: August 21, 2022

texto em

texto em