Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de História da Educação

versão On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-185

Artigos

Under the bell towers of Candelária: schooling in an urban parish of the Brazilian capital (1870)1

1Universidade Federal da Paraíba (Brasil). alinedemoraislimeira@gmail.com

2Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil). alinemachado07@yahoo.com.br

This study, whose theoretical-methodological resource is centered on the scale variations perspective, with a specific geographical clipping and investment in the analysis of local singularities, intends to analyze aspects related to the process of schooling in the Brazilian capital in the 19th century. For this, it selected as object of analysis some sources and documental traces from the 1870's, referring to the experiences, subjects, institutions and statistical data of the History of Education of an urban parish of the Imperial Court, whose name is Candelária. This way, it apprehended important reflections about what can be considered unique or similar in relation to the parish of Candelária and the other urban and rural parishes of the Imperial Court, regarding the issues of Instruction.

Keywords: Schooling; Parish of Candelária; History of Education

Este estudo, cujo recurso teórico-metodológico está centrado na perspectiva das variações de escala, com recorte geográfico específico e investimento na análise de singularidades locais, pretende analisar aspectos relacionados ao processo de escolarização da capital brasileira no século XIX. Para isso, selecionou como objeto de análise algumas fontes e vestígios documentais da década de 1870, referentes às experiências, sujeitos, instituições e dados estatísticos da História da Educação de uma freguesia urbana da Corte Imperial, cujo nome é Candelária. Desta feita, apreendeu importantes reflexões acerca do que pode ser considerado ímpar ou similar em relação à freguesia da Candelária e das demais freguesias urbanas e rurais da Corte Imperial, no que concerne aos assuntos da Instrução.

Palavras chaves: Escolarização; Freguesia da Candelária; História da Educação

Este estudio, cuyo recurso teórico-metodológico se centra en la perspectiva de variaciones de escala, con corte geográfico específico e inversión en el análisis de las singularidades locales, pretende analizar aspectos relacionados con el proceso de escolarización de la capital brasileña en el siglo XIX. Para ello, seleccionó como fuentes de análisis algunas fuentes documentales y rastros de la década de 1870, haciendo referencia a las vivencias, sujetos, instituciones y datos estadísticos de la Historia de la Educación de una parroquia urbana de la Corte Imperial, cuyo nombre es Candelária. En esta ocasión aprehendió importantes reflexiones sobre lo que puede considerarse extraño o similar en relación con la parroquia de Candelária y las demás parroquias urbanas y rurales de la Corte Imperial, en lo que concierne a las materias de la Instrucción.

Palabras clave: Escolaridad; Parroquia de Candelária; Historia de la Educación

Introduction

In this study, we will discuss one of the most important concepts of microhistory, the variation of scale, whose referential is constituted mainly by Jacques Revel. For him, "what is at stake in the microhistorical approach is the conviction that the choice of a particular scale of observation is associated with specific knowledge effects and that such choice can be put at the service of knowledge strategies" (REVEL, 2010, p.438). Thus, it interests us here to inquire about the processes of schooling from specific plots, less general, more local, without, however, losing sight of a broader analysis at various times. As José Gondra pointed out, the scale results from a choice that functions as a compass that guides the research and establishes parameters regarding what will be seen by the researcher. Therefore, the definition of a scale inevitably participates in the fabrication of research problems and the possibilities of making them intelligible (GONDRA, 2012, p.86). In this sense, the investment developed here is inscribed in the movement that has been marking more recently the field of History of Education, from researches that explore increasingly specific geographical clippings, with the intention of investigating singularities and local experiences.

We intend to emphasize the importance of noticing the great diversity formed by the urban and rural parishes of the capital city of Brazil Empire and the heterogeneity found in the subdivisions of these regions, an increasingly advantageous problematization about the breadth and complexity of the educational actions developed in the Brazilian Eighteenth Century. Searching evidence about the ways of organizing education in the past, we know that the investigative possibilities are almost infinite: teaching initiatives (public and private institutions, the instruction that took place in the family environment, in religious manifestations, parties, conversations, and the initiative of associations, churches, associations, newspapers, magazines, etc.), the subjects involved (State, Catholic Church, philanthropic institutions, intellectuals, teachers, students, etc.), the knowledge taught, architecture, furniture, legislation, among others. We chose, however, to analyze the actions of the imperial government and the enterprises of the private sector in primary schooling in a specific region of the Province of Rio de Janeiro, located in the urban sector of the Imperial Court, the parish of Candelária.

The region, which was the second one created in the Brazilian capital still in 1634, was located in an urban, central and commercial area, being of great importance in the import and export relations of several kinds of goods, and was home to important buildings such as the General Post Office, the Imperial Palace, the Amortization Fund and also Praça do Comércio. However, even presenting such relevance we almost didn't find studies in the historiography of education that approached an analysis about the parish21. In this sense, we dialogued, throughout this article, with researches such as those by Lopes (2006), Schueler (2005), Santos (2020), Pasche (2014), Limeira and Gondra (2022) and Fridman (2017).

In this way, we decided to reflect on some questions. How was the schooling process constituted in the parish of Candelária? What forces, subjects and institutions were involved in this kind of initiative? What were the relations between educational supply and demand in this parish in the final decades of the Empire? How was the primary schooling organized in the parish of Candelária, comparatively to other urban and rural parishes of the Imperial Court? What were the actions of the government in public education in that region? How was the public and private network constituted, comparatively, in that locality? Were there in the Parishes of Candelária private schools with subsidies from the Imperial Government, educational experiences maintained by teachers and associations that acted in favor of Education or other educational actions maintained by the civil society?

For this task, we appropriated the analysis of official sources such as the Reports of the Minister of Business of the Empire, advertisements and information from printed materials (Almanak Laemmert, A Escola: Revista Brasileira de Educação e Ensino, Jornal do Commercio and Jornal A Reforma), Recenseamento do Brazil (IHGB, 1872) and handwritten documents under the custody of the Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro (salaries and appointments of school employees, school buildings, teachers, examinations of teacher competitions, dispatches on the economy of public instruction, teaching and enrollment maps, requests, letters and reports dedicated to private instruction and correspondence of the delegates of instruction of the Candelária district).

In this way, we built the study based on two specific moments. In the first, we seek to discuss about a relational analysis of the Empire's Capital and the parish of Candelária, presenting aspects of its geographical, cultural, religious and political constitution. In the second moment, we seek to inquire data about public and private instruction, approaching primary and secondary education in the parish of Candelária (focusing on traces about the development of the actions of the public power, the institutions, the statistical data and the subjects, students and teachers).

The urban parish of Candelaria

From midnight until 2 o'clock in the morning yesterday, the clock in Candelaria Church rang consecutively for hours, which, as should be well understood, were not hours, but the ballads on the bell that usually gives them. This caused the neighborhood to be astonished, and in the morning the comments about the case gave it a mysterious supernatural air, very much in accordance with popular beliefs (Gazeta de Noticia (RJ), 1876, year 2, nº160).3

In the news above we have announced the ringing coming from a bell tower in Candelária, coordinating the life of nearby inhabitants. It is not a recent fact that one of the most beautiful churches in Rio de Janeiro occupies a place of relevance in the city, not only as a sign of historicity, of affection for the faithful of the Catholic creed, or of monumental beauty, the church of Nossa Senhora da Candelária was a constitutive mark in the creation and functioning of the city.

The church gave its name to the old parish and this was of great importance, especially after the arrival of the Portuguese royal family in 1808. According to some analyzed records, the founders of Nossa Senhora da Candelária Church were Antonio Martins da Palma and his wife Leonor Gonçalves, in fulfillment of the promise made amidst the strong storm that affected the ship where they were on the way from India to Ilha da Palma. The couple's first port of call was Rio de Janeiro, and in the early decades of the 17th century they fulfilled their promise to build a church in gratitude. Some historians, such as Vieira Fazenda in Antiquities and Memories of Rio de Janeiro (2011), report another version for the emergence of Candelaria Church. According to the author, the hermitage or also known as the church of Várzea was built in the place where a ship of the same name washed ashore, whose timbers were used. However, the illustration on the ceiling of the current temple of Candelária defends the version of the origin of the church from the fulfillment of the promise of the Palma couple.

There are also divergences as to the period of establishment of the Candelaria Church and its first location. Generally speaking, it is the decade of 1630. Well known books about the early times of Rio de Janeiro, such as those by Vivaldo Coaracy (1988), Noronha Santos (1981), João da Costa Ferreira (1933), give notes on the subject. The fact is that the building of Parish of Candelária, as announced by many historians, took place in 1634. Its genesis is related to the construction of its small temple, the third of the municipality, dedicated to the Virgin Mother of God. Both, the parish and the church are woven together in the loom of one of the most imposing lay associations that remains until today as participants in the urban life of Rio de Janeiro, Irmandade do Santíssimo Sacramento da Candelária.

We can observe then, that the church was an important place since the early times of what is now the City of Rio de Janeiro, helping in the delimitation of the city and organization of its inhabitants.

The parish was also constituted from the wide influence of Irmandade do Santíssimo Sacramento da Candelária (ISSSC) that, in some way, conducted the life of that part of the city. And recent studies already point out aspects of the relationship between local religiosity and the social, educational, political and cultural life of the region (SANTOS, 2020). Irmandade da Candelária was not the result of a large urban center, but is intertwined with the very emergence of the Perish of Candelária and its urban character. Inspired by Boschi (1986) we can risk saying that the solidification and maintenance of the urban life of that parish were also a result of the confraternity organization. According to this interpretation guideline, the confraternity that occupied itself with actions that met the social needs of the population, constituted a political and social organization of the region, and was still responsible for urban improvements around the temple. The ISSSC exercised its power in the Parish of Candelária not only in terms of social confluence, but also by the ideological force that it wielded in relation to the region's inhabitants.

The current administrative divisions in Rio de Janeiro have their origins in remote times, when the territorial organization encompassed religious, police, and juridical aspects that sometimes mixed and diverged, called parishes. At first, the Imperial Court was segmented following only an ecclesiastical aspect, based on the scope of territorial administration that the parishes erected little by little. The division based on the parishioners served spiritually by a parish priest gradually acquired official perspectives by the government. In the imperial period, the promulgation of the Additional Act in 1834, which provided additions and changes to the Constitution of 1832, was characterized, above all, by the imposition of the centralizing political model, responsible for an important geographical change. With the Additional Act (August 12, 1834) the city of Rio de Janeiro was detached from the Province, constituting the Court or Neutral Municipality. This marked the differentiation of Rio de Janeiro in relation to the other municipalities, and as capital of the nation, its direct administration and subordination to the central government (SANTOS, 1965).

The Parish of Candelária was the second created in colonial Rio de Janeiro and the first created to occupy the region of the floodplain, i.e., down the Castle Hill where it was established by Salvador Correia de Sá the Freguesia de São Sebastião in 1569 (FRIDMAN, 2017). Due to the population increase and territorial expansion there was a need for the creation of other rural and urban parishes throughout the 14th and 17th centuries: Irajá (1644), Jacarepaguá (1661), Campo Grande (1673), Ilha do Governador (1710), Santa Rita (1721), Inhaúma (1749), São José (1753), Guaratiba (1755), Engenho Velho (1762), Ilha de Paquetá (1769), Lagoa (1809), Santana (1814), Sacramento (1826) replacing the former freguesia of São Sebastião, Santa Cruz (1833), Glória (1834), Santo Antônio (1854), São Cristóvão (1856), Espirito Santo (1865), Engenho Novo (1873) and Gávea (1873). By the end of the monarchy there were a total of twenty-one parishes in the Empire's capital.

The so-called urban parishes were those in the central axis of the city, expanding southward and westward. Keeping the differences between them, we can say that the common point was the typical activities of an administrative center, such as commerce and services (sewage, tree planting, lighting, medical care provided by the Santa Casa de Misericórdia). There were 13 parishes in this group: Candelária, São José, Santa Rita, Sacramento, Glória, Santana, Santo Antônio, Espírito Santo, Engenho Velho, Lagoa, São Cristóvão, Gávea and Engenho Novo. The rural or "outlying" parishes had as similarities the large territorial extensions, and the activities mostly related to agriculture. As the name indicates, they were outside the urban axis. This set comprised 8 parishes: Irajá, Jacarepaguá, Inhaúma, Guaratiba, Campo Grande, Santa Cruz, Ilha do Governador and Ilha de Paquetá.

The parishes (boroughs) of Candelária, Santa Rita and São José together with the parish of Sacramento (created in 1826 to replace the freguesia of São Sebastião), constituted the commercial part of the country's capital. The region of the parish of Sacramento, near the limits with Candelária, had great import and export commerce. The buildings of the School of Fine Arts (1906), the National Institute of Music (1833), the Portuguese Reading Cabinet (1837). It was a region characterized by the headquarters of associations such as the Association of Commercial Employees of Rio de Janeiro (1900), the Institute of the Brazilian Bar Association (1843), the Portuguese Gymnasium (1868), etc. There were also in this parish about four theaters and 7 churches, most of them linked to brotherhoods and third orders (SANTOS, 1965).

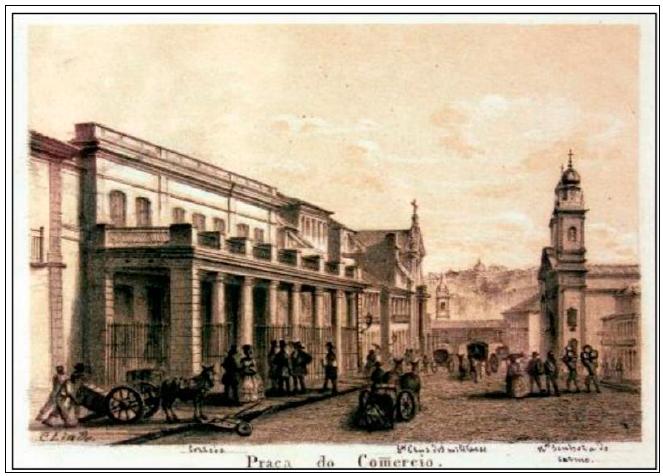

In the parish of Candelária, "place of import stores, commissary houses, workshops, consulates, banks and offices" (SCHOLAR, 2005, p.166) were still important buildings of public functions as the Post Office (1663) in the old Rua Direita, the Amortization Fund (1827), the General Office of Telegraphs (1743), the Navy Arsenal (1764) and offices dependent on the Ministry of Navy (created between 1810 and 1814). There were also several national and foreign private banks, shipping companies, insurance companies offices, consulate of several countries, joint-stock companies, headquarters of railroad companies, the headquarters of the English telegraph, consignment houses and photo houses are also in this region (SANTOS, 1965). Praça do Comércio (1834) is also worth mentioning in this parish. Its origin goes back to the small stands selling vegetables, fish and flour that used to be located by the sea:

Source:. Brasiliana Iconográfica. Available at: https://www.brasilianaiconografica.art.br/obras/18555/praca-do-comercio.

Picture 1 Praça do Comércio in 1856, by Carlos Linde

As Schueller (2005) observes, the Fish Market, the Customs and its warehouses, near Largo do Paço (Imperial Palace) and Praça de D. Pedro II (now Praça XV de Novembro), gave uniqueness to the parish of Candelária (SCHUELER, 2005, p.161). The territory, where 9 Catholic institutions were located, an unusual reality compared to other urban or rural parishes of the capital of Brazil, also had its Royalty status, because the king's family and the "most faithful subjects" arrived there in 1808. The old Carmo Palace, which with improvements was renamed Paço Real (Royal Palace), was also home to D. Pedro I. At the time of D. Pedro II's Empire began to be used only for gala ceremonies and political actions. Within the limits of Candelária there was also Praça D. Pedro II (SANTOS, 1965).

From the 1870s on, the Court would experience more intensely the separation of the uses of its parishes by social classes, mainly due to two factors. First, the Improvement Committee established in 1875 a series of interventions in the central parishes that consisted in the widening and straightening of streets, opening of squares and improvement of hygienic conditions, in order to help the circulation of people, ventilation of houses, drainage of rainwater and beautification of the region. Changes for the sake of modernization that could not coexist with the population contingent, especially the poor. Second, the intensification of investment in streetcars and trains provided greater mobility and physical growth throughout the Court. In 1858, the first stretch of D. Pedro II railroad was inaugurated, which caused the occupation of the crossed areas. The trains also became the locomotion to the central region of the Court used by the working population that lived in the rural parishes (ABREU, 2013).

The urban and rural parishes of the Court changed. The wealthier people began to leave the tumultuous commercial axis of the capital of the country and to inhabit the parishes southward, which suffered constant urban improvements resulting from foreign capital. The poor and working population gradually occupied the rural parishes, with regular use of the railroad for their daily traffic. These regions experienced a population growth and the modification of the characteristics dedicated to agriculture with the implantation of some textile industries. In the parish of Candelária there was a territorial decrease and a population emptying, and little by little the attributes of a commercial area came to the fore. The parishes of Santana, Santo Antônio, São José, Santa Rita and Espírito Santo began to be inhabited mostly by the poor population, free and slaves of gain due to the proximity of the workplaces; even if their stay there was not well seen and actions against their characteristic residences, the tenements, occurred vehemently (ABREU, 2013). Therefore, the last decades of the 1800s changed the occupation pattern of the parishes of the Imperial Court, and such data will constitute an important element for the reflections about their schooling experiences.

Aspects of school experiences: institutions and subjects

Despite the emphasis on the real estate and commercial issue in the tiny Parish of Candelária, there was also a resident population there. The end of the Paraguayan War led to the perception of the even greater need for a general census, so that information about the territorial extension and population of the Empire could be made known to all. The relevance of knowing the population contingent was also justified because of the political discussions related to the gradual granting of freedom to slaves, and the need to know their entire population, especially after the promulgation of the free-birth law in 1871.

Statistics was also, in the discourse of progress and modernization, the scientific mechanism par excellence, necessary to apprehend the needs and possibilities of action in the country (SENRA, 2009). Moreover, the need for statistics was in Brazil to firm an international commitment by assuming reliable standards and valued procedures, as well as to reaffirm the interest of civilization (GIL, 2009). In this sense, the census of the Empire, dated 1872, released tables with information on the number of inhabitants by gender, marital status, "races", creed, nationality and who could read and write, for the whole Empire. Other tables with information for each province and the Neutral Municipality had detailed references about the urban and rural parishes. About the parish of Candelária, we have:

| Free Population by gender and marital status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Silgle | Married | Widowed | Total population |

| Men | 5762 | 1003 | 142 | 6907 |

| Women | 783 | 365 | 107 | 1255 |

| Free population by race and gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Whites | Browns | Blacks | Mixed Races |

| Men | 6494 | 149 | 260 | 4 |

| Women | 1010 | 127 | 117 | 1 |

That is, considering the free population (not enslaved), we can see that Candelária was a region inhabited mostly by men, most of whom were single4. In relation to the "races" designated in the census (only whites, browns, blacks, and mixed races, not including common denominations in the 19th century such as goat, Creole, among others), whites were the largest number. Due to a great influence or not of the Irmandade do Santíssimo Sacramento da Freguesia da Candelária the majority of the population was Catholic. And, curiously, it was a parish whose population had more foreigners than Brazilians. This type of grouping, free men and foreigners, as a characteristic of the parish of Candelária population, is understandable when we observe that, in general, the Neutral Municipality had a large number of foreigners, free men who were engaged in industrial and commercial activities. Numerically, 589 were considered to be manufacturers and fabricators, while 17,038 were engaged in the professions of merchants, clerks, and bookkeepers. A total of 1,843 slaves lived in the parish of Candelária, according to the 1872 census, of which 1,224 were men and 619 women. And the people with disabilities totaled 23 (considering men and women, free and slaves, in the categories of blind, deaf-mute, crippled, insane and alienated, according to the document).

Within the general picture of the urban parishes, Candelária was not the most populous. This position was occupied by the parish of Santana with a total population of 33,746 free inhabitants. Especially, after the interventions in the urban mesh, the Parish of Candelária underwent changes and, according to Abreu (2013), its population had a decrease in the 1870s. Between 1838 and 1870, the number of inhabitants of Candelária decreased by 9%, and from 1872 to 1890, it reduced by another 3%.

This tiny free population residing in the parish of Candelária (8,162 inhabitants), could enjoy the rights of citizens, and among them was that of free education.

| Free population: Illiterate inhabitants who are unable to read and write | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||

| Able to read and white | Illiterate | Able to read and write | Illiterate |

| 6276 | 631 | 735 | 520 |

The number of residents who knew the rudiments of reading and writing was higher than the illiterate ones. The number of school-age children was 1,074, and they constituted the school-age public according to Couto Ferraz Reform, which was the educational legislation in force, indicating children between 6 and 15 years old as potential public to attend elementary school. Of this total of potential students, only 110 attended formal school, that is, they were the public effectively enrolled in school. This represents about 10% of attendance of a possible school demand in formal institutions (public or private). These numbers can also represent a possible entry of these other children (90% or 964 boys and girls) in informal experiences and practices (separate classes, primary education in associations, religious brotherhoods, societies, associations, etc.).

Comparatively, Candelária's educational demand, that is, its public of school age, was not as great as those of the other urban parishes. Limeira and Gender (2022) state that Parish of Santana had the expressive number of 6 thousand children of school age. While the parish of Santo Antônio had the school demand of almost 5 thousand children. On the other hand, without considering the Parish of Candelária, the places with smaller population and little schooling quantity are São Cristóvão, Lagoa, Espírito Santo and Engenho Velho.

Observing the data from the study, we conclude that the total population of Candelária was small in relation to the others and that its educational demand was also reasonably smaller. With similar numbers, only the Parish of São Cristóvão was included. However, leaving the macro comparison, with the other urban parishes, and looking at Candelária more specifically, we see that there was a percentage that was not educated. We observe that 110 individuals attended public schools and private schools (educated population) while 964 was the total of children who formed the public who could be educated, but with no record of formal attendance in Candelária, which means to understand as well as possible their attendance in neighboring parishes. Thus, in view of the numbers for the year 1872, we also wonder about the possibility that these children did not meet the necessary requirements to attend schools (such as being vaccinated and not having contagious diseases, Couto Ferraz, 1854). The information from the 1872 census still opens the possibility to think about the existence of a demand met by informal initiatives, since among the total population (8,162) those who could not read and write were only 1,151 inhabitants while those who had such skills represented 7,011 people (SANTOS, 2020).

These numbers with high literacy rates may be indications even that the school demand in Candelária was not met in the locality itself, but in neighboring parishes, or that children learned to read and write (basic skills of primary education) in informal classes, or that other youth and adults came to live in Candelária already in possession of such skills or learned them in evening courses or informal practices.

The General Teaching Law of 1827 ordered the creation of primary schools in all the towns, cities and the most populous places in the Empire, with girls' schools established only where the presidents of the Council deemed them necessary. The Couto Ferraz Reform, in 1854, established in Article 51 that in each parish there should be at least one elementary school for each sex. And in the Decree of Leôncio de Carvalho, in 1879, Article 8 enabled the government to alter, according to educational needs, the distribution of schools among the six districts of the Court. In this sense, we consider that public schools during the Empire were not distributed homogeneously throughout the territorial division of the Court, as the following table also shows:

| Distribution of public elementary school by parishes of the Imperial Court 1870-1879 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years: | 1870 | 1871 | 1872 | 1873 | 1874 | 1875 | 1876 | 1877 | 1878 | 1879 |

| Urban Parishes: | ||||||||||

| Glória | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Candelária | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| São José | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |||

| Santa Rita | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Sacramento | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Santana | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 | |||

| Santo Antônio | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |||

| Lagoa | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||

| Engenho Velho | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Espírito Santo | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |||

| São Cristóvão | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Engenho Novo | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| Gávea | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Rural Parishes: | ||||||||||

| Inhaúma | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Irajá | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Jacarepaguá | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Campo Grande | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Santa Cruz | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Guaratiba | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | |||

| Ilha do Governador | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Ilha de Paquetá | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Total: | 58 | 67 | 67 | 76 | 75 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 90 | |

It is evident that between the year 1870 and 1879, about 37 public elementary school were established, even considering that not all establishments were in operation immediately after their creation due to the lack of teachers, furniture and teaching materials. It is also interesting to note the permanence throughout the decade of the quantity of schools in some parishes such as Candelária, Inhaúma, Irajá, Santa Cruz and Paquetá. While others showed a growing change as the parishes of Glória, Santa Rita, Santo Antônio, Lagoa, Espírito Santo, Engenho Novo, Gávea and Campo Grande. And other parishes showed growth with a relative fall, especially in 1873, and then growth again in the number of schools. This is the case of the parishes of Sacramento, Santana, Engenho Velho, São Cristóvão and Jacarepaguá. Although the year 1879 ended with a fall, compared to the growth achieved with 95 schools in the years 1876, 1877 and 1878, it is undeniable the educational development in the capital of Brazil throughout the 1870s.

The parish of Candelária during the whole period from 1870 to 1889 had only the minimum quantity of schools instituted by the educational decrees, that is, one for each sex. In other words, from 1883 on, in the reports of the Minister of Business of the Empire, there was only one public elementary school for the region. This was due to the removal of the boys' school from the parish of Candelária on August 17, 1880. As consisted in the decree of Leôncio de Carvalho (1879) the government could alter according to the needs of education the distribution of schools by the parishes of the capital. According to Decree No. 7792 - of August 17, 1880, the act of removing the boys' school of the Parish of Candelária was justified by the lack of attendance of students being the establishment closed, while there was a fair petition for schools forwarded by residents of the neighborhoods of Pedregulho, Benfica and São Francisco Xavier, in the Parish of Engenho Novo, and to this was added the lack of funds for the creation of new schools in that period.

Comparing the parish of Candelária with the others, especially those that composed the group of urban parishes, we observe that besides having few schools, the conditions of the educational establishments were considered very poor, according to the sources. The two schools in the parish of Candelária, like most of the schools established in the Court, both in urban and rural parishes, functioned in rented houses, despite Article 55 of the Couto Ferraz Reform in 1854 already decreed that the schools would be established in their own buildings. The only two public schools in Candelária functioned in rented houses and had the typical commercial movement of the parish as a big problem for the functioning of the classes and the learning of the students. In the case of the boys' school (located at 77 Theophilo Ottonni Street), the noise made it difficult to follow the "school process", making it hard to distinguish the sound of the street and of the students. The problem in this school was further increased by the small size of the classroom, the heat produced by the geographical position that caused constant sun from morning to afternoon, and the latrines adjacent to the classroom causing unbearable stench. For the girls' school, which was located at 136 Ourives street, the lack of space to hold the number of students is stressed along with the noise from a workshop that operated downstairs, disturbing the school work. But the main issue was the location, which made it close to the school of the same sex in Santa Rita parish. They diagnosed, therefore, that it would be better to remove it to a more central location in the parish, bringing more benefit to the population (Report of the Minister of Business of the Empire, year 1873, Annex 3, p.13).

The reality of the two existing schools in the Parish of Candelária was far from what the government proposed as ideal. The schools were to have a waiting room for students to keep their capes and hats, also serving as a reception for people who went to talk to the teacher or to pick up the students. A classroom was to have enough space for each student to occupy 1 square meter of surface area and 4 cubic meters of air, as well as sinks to serve them. A smaller room for writing and sewing properly furnished; a hall for recreation, meals and gymnastic exercises; a room with latrines far away so as not to exhale bad smells from the rooms, and if possible a garden for the teacher and students to rest. It was possible for this outline to be adapted according to the conditions of each parish (Report of the Minister of Business of the Empire, year 1873, Annex 3) page 13.

Another important element, regarding the physical spaces and location of the schools in the parish, refers to the constant changes of addresses, which, sometimes, caused logistical problems regarding the attendance of the quantity of students. In 1879, the delegate of instruction of the parish of Candelária and acting of the parish of Santa Rita, sent to the Inspector General of Public Instruction a letter warning about the transfer of the 2nd male school of Santa Rita and the female school of Candelária. For the delegate, with the transfer of the 2nd male school to Largo de Santa Rita, poor children living in the areas from Rua da Saúde to Gamboa and Sacco de Alferes would be left without educational services.

The transfer of the girls' school from the Parish of Candelária to Largo de Santa Rita would mean that there would be no school for girls within the limits of the Parish of Candelária. The suggestion of the Delegate of Instruction was the establishment of a second girls' school in Candelária, located in the center of the district. But the data indicate that the delegate's proposition was not heeded, since until the end of the Empire the Parish of Candelária had only one girls' school.

In general, during the period analyzed, it was possible to ascertain in the reports of the Minister of Business of the Empire and in codices of the AGCRJ different locations occupied by the feminine and masculine schools of Candelária. We observed that while the boys' school had a certain stability, occupying addresses mostly on Theophilo Ottoni street, the girls' school was more mobile. We have to consider that the girls' school functioned for a longer period of time and possibly because it had a larger number of students it needed buildings with larger rooms. The girls' school occupied six addresses in different streets of the Parish of Candelária (SANTOS, 2020).

In 1871, the Candelária Boys' School, whose teacher was Antonio José Marques, had submitted 5 students to the public elementary school exam. The names of these boys are: Carlos Augusto Moreira da Silva (enrolled at age 11 on February 23, 1869), Vicente Corrêa de Azevedo (age 10, enrolled on August 10, 1870), Eduardo Teixeira Leite (enrolled on March 2, 1869, 6 years old and completely illiterate), Alfredo Manoel de Oliveira (enrolled January 8, 1866, age 7), and José Antonio da Rocha (enrolled January 14, 1870, age 10). ). In the girls' class, directed by the teacher Catharina Lopes Coruja, 3 girls were examined in the same year, namely: Idalina Vieira Lima (enrolled on April 12, 1865, at age 7), Glyceria Bibiana de Gouvêa (enrolled on January 12, 1863, at age 7 and completely illiterate), and Marcolina Rosa Baptista (enrolled on February 4, 1867).

The names of these pupils are very fragile traces, and may make little sense if taken in isolation, not allowing us to gather more information about them, their families, and their school experiences. It would be necessary to cross-reference many other sources, given the scarcity of information available. However, a survey in the Reports of the Minister of Business of the Empire, associated with the studies of Borges (2014), made it possible to ascertain important facts involving some of these students of the public schools of the Parish of Candelária.

Carlos Augusto Moreira da Silva in 1872, in the very next year when he took the public elementary school exams and finished them, he was appointed as an Adjunct Teacher, which referred to a system of training by practice, considered by Minister Couto Ferraz as effective and low-cost, although it was quite debated among the teachers. The training by practice, located in the elementary school environment itself, through the figure of the adjuncts, a kind of trainee, reaffirmed traditional practices of reproduction of the teaching profession, preserving on a professional group, and often a family one, the monopoly of the knowledge of that craft. The category of assistant teacher was regulated by the Couto Ferraz Reform (1854), which determined the age of 12 years old as necessary to receive authorization to exercise, that candidates should come from the public elementary school, having succeeded in the annual exams and had shown propensity for teaching, besides indicating preference to the children of public teachers. The student Carlos Augusto then applied for the position without taking a new exam, based on the conditions of this Article 35 of the Couto Ferraz Reform. In 1879 he still remained in office as adjunct professor. In 1883 he was interim teacher (substituting the head teacher) at the 3rd Boys' School in Santa Rita and the following year at the 2nd Boys' School in Glória.

The former student of the School for Girls of the parish of Candelária, Idalina Vieira Lima, as well as Carlos Augusto, followed the teaching career being nominated in 1872 under the same circumstances, as an adjunct, having remained in the following years, until 1874 when there is still some record. Glyceria Bibiana de Gouvêa was also a teacher, and in 1872 was named interim adjunct teacher until a vacancy arose in a school at the Court. In 1874 she was named permanent adjunct, remaining there until 1879, with no further data about her.

We can understand the little and incomplete information about the former students of Candelária as important traces about the trajectory of a very large and heterogeneous student body. After completing elementary school, a large part of this public may have gone on to practice activities related to commerce, very common in the Candelária region. Some, very few, as we have seen, followed a career in teaching, from a paid experience classified in levels over 3 years. It may even be that some of them qualified as public primary school teachers at the Court. The sources accessed still say little for as much as we would like to know.

As far as teachers are concerned, we have collected the names of those who taught in the public elementary school of the Parish of Candelária between 1870 and 1889:

| Public primary teachers in the Parish of Candelária 1870-1889 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Years | Boy’s school | Girl’s school |

| 1870 | João da Matta Araújo | Catharina Lopes Coruja |

| 1871 | Antonio José Marques | Catharina Lopes Coruja |

| 1872 | Antonio José Marques | Catharina Lopes Coruja |

| 1873 | Antonio José Marques | Guilhermina Azambuja Neves |

| 1874 | Antonio José Marques | Guilhermina Azambuja Neves |

| 1875 | We did not get any information | Guilhermina Azambuja Neves |

| 1876 | José Antonio de Campos Lima | Guilhermina Azambuja Neves |

| 1877 | We did not get any information | Guilhermina Azambuja Neves |

| 1879 | José Antonio de Campos Lima | Guilhermina Azambuja Neves |

| 1881 | Extinct school | Guilhermina Azambuja Neves |

| 1882 | Extinct school | Adelaide Augusta da Costa (After Adelaide Augusta da Costa e Silva) |

| 1883 | Extinct school | Adelaide Augusta da Costa |

| 1884 | Extinct school | Amélia Augusta Fernandes or Amélia Fernandes da Costa |

| 1886 | Extinct school | Amélia Augusta Fernandes or Amélia Fernandes da Costa |

| 1887 | Extinct school | Theresa Carolina de Mirandella |

| 1888 | Extinct school | Amélia Augusta Fernandes or Amélia Fernandes da Costa until June 6th |

| 1889 | Extinct school | Amélia Augusta Fernandes or Amélia Fernandes da Costa |

Source: Reports of the Ministry of Business of the Empire from 1870 to 1889, Arquivo Nacional, Codex I E 4 25, - Education Series.

Antonio José Marques appears in the records with a long teaching career, between the 1860s and 1880s. He was the one who governed the public chair of the Candelária School for the longest time, teaching for 6 years (considering the studied cut). He was a bachelor and has his first appearance in the official records in 1862, when he was nominated interim teacher of the 1º Escola de Meninos da Freguesia de Santana. In 1866, he is listed as adjunct teacher with three years of service. In 1871, for having fulfilled the requirements, he was named teacher of the Candelária boys' school. In 1875, he taught arithmetic at the Escola Normal da Corte, a sign of career progression. The following year he was removed from the Candelária school and assigned to the Lagoa boys' school. In 1880 and 1881 he is listed as a teacher at the Santa Rita Boys' School, where he is also listed as a teacher in 1887. In 1873, at the Pedagogical Conference, Antonio José Marques makes the final exposition of his work on the decimal metric system. About the career of this teacher Borges (2014) reports that this teacher was engaged in issues of industrial and technological development of the country. While working at the school of Parish of Lagoa he ran a Night Course of Trades, even without receiving remuneration, because he had not obtained official authorization for the classes. Antonio José Marques was also a teacher at Liceu Artístico e Industrial and secretary of the Associação Protetora do Liceu Artístico e Industrial. Besides, he offered services to the Associação promotora da Instrução. It is said that his retirement took place only in January 1888.

Professor José Antonio de Campos Lima taught for two years at Parish of Candelária. He was assistant teacher to Candido Matheus de Faria Pardal, in the first male school of the Parish of Santa Rita in 1860, where he remained until 1865. In 1867 he was named assistant teacher of the boys' school of the Parish of Ilha de Paquetá. And between 1869 and 1875 he is an effective teacher at the 2nd Boys School of the Parish of Lagoa. In 1879 he receives a bonus for 10 years of teaching. Finally, in 1880 he is removed from the Parish of Candelária, due to the extinction of the school, and occupies the teaching in the 1st boys school of the Parish of Sacramento where he still appears as a teacher in 1886. In addition, according to Borges (2014), he was a member of the jury of the Court and jubilated from public teaching in May 1886.

João da Matta Araujo, a teacher in the public and private sphere, was also a member of the Sociedade Bahiana de Beneficência, a kind of mutual aid society (BORGES, 2014). He qualified for private primary teaching in the year 1858, when it is also noted his appointment to the 1st boys' school of Santa Cruz Parish. In 1860 he obtained a license to teach Latin in private classes. Two years later he was removed from the public school of Santa Cruz and appointed to the first school of the parish of Ilha do Governador, where he taught for only one year. In the reports from 1864 to 1870 he appears as a teacher in the Parish of Candelária, and in 1871 he starts teaching in another municipality. In 1872 he returns to Corte and teaches at the second boys' school at Parish of Glória. In 1875 he assumes the chair of sacred history at the Normal School, together with Monsignor Jose Joaquim Pereira da Silva. In the same year, his name appears on the list to receive a bonus for 20 years of teaching. In his long and successful teaching career, there are indications that he has also performed other actions. As in 1873, together with the teachers Antônio Cypriano and Fonseca Jordão, he developed a work to improve the plan and program of the 3rd year adjuncts' exam (BORGES, 2014). According to Teixeira (2008) in 1887 the teacher publishes the book Lições Práticas de Ortografia and the book for Dictated in Primary Schools. According to information from the Report of the Minister of Business of the Empire, both works were adopted as a compendium for the elementary school of the Court. In addition, Teixeira (2008) also cites the authorship of the teacher João da Matta Araújo in the book intended for reading, writing and grammar entitled Collecção de Cartas para o Estudo da Leitura. According to Borges (2014) João da Matta Araujo was a founding member in 1874 of a private Normal School in the Court, a member of the Court jury in 1885, and retired from the public teaching profession in June 1886.

In the cadre of the female public magisterium at Candelária, we find five teachers. The teacher Catharina Lopes Coruja was married to the teacher Antônio Pereira Coruja (public and private teacher, provincial deputy of Rio Grande do Sul, founder and director of the Lyceu de Minerva, treasurer of the IHGB, president of the Imperial Society Lover of Instruction, author of several books for teaching) of whom she was previously a student (LIMEIRA, 2010). According to Bastos (2006), she founded a private school for girls at 88 Assembléia street, that closed its activities in 1849. She was appointed as a public teacher in the city of Rio Grande in 1834, three years later she took part in a contest for the chair of São José parish and only in 1843 she was appointed as an effective teacher. In the years 1844 to 1869 she already appears as a public teacher in the Parish of Candelária. Catharina Lopes had other activities in the field of education, for example, in 1857 she was one of the evaluators of the contest for public teachers; in 1859 together with other teachers, she composed a work about the internal regulation of the feminine schools, and in the following year she was part of the commission which evaluated a grammar for the public schools in substitution of Cyrillo Dilermano da Silveira's grammar. The evidence indicates that he retired in 1874 from public teaching, and died in the early 1880s (BASTOS, 2006).

The teacher Guilhermina Azambuja Neves was an active teacher in the educational and political context of the time. She was born in Rio de Janeiro and started her teaching career at Parish of Candelária in 1866. She was married to Arthur Frnaklin de Azambuja Neves, an amanuensis of the Inspectorate of Primary and Secondary Instruction of the Court, and Delegate of Instruction in the parish of Lagoa. She was also the niece of an elementary school teacher at Corte, Anna Euqueria Lopes Alvares (Girls’ school from Parish of Lagoa), to whom she dedicated one of her books, recording that her aunt and her aforementioned husband had raised her, since she had become an orphan. She was a supporter of the intuitive teaching methodologies, having published the following books, with authorization to be used in schools, in the 1870s and 1880s: Methodo brasileiro para o ensino da escripta: collection of notebooks, containing rules and exercises (1881); Methodo intuitivo para ensinar a contar, containing models, tables, rules, explanations, exercises and problems about the four operations (1882) and Entretenimento sobre os deveres de civilidade, collecionados para uso da puerícia brazileira de ambos os sexos (1875, second edition in 1883) (SCHUELER, TEIXEIRA, 2008; TEXEIRA, 2008).

During the period of her performance, in 1877, the teacher Guilhermina, in search of modern educational practices, publishes in the journal A Escola a request for the donation of books to compose the library of didactic works of primary instruction that she was organizing (Revista A Escola, year 1877, v.34, n.2, p.67). Among his many projects was the organization of a school library (FERREIRA, SOARES, 2019). The press sometimes reported information about that library: "The teacher Guilhermina de Azambuja Neves has received more for the library that she is organizing in the public school under her teaching" (A Reforma, 1878)5. Or even "(...) offer the lady public teacher of the parish of Candelária, D. Guilhermina de Azambuja Neves, an important donation (...) for the library she is organizing in this school (...)" (A Reforma, 1880). Such information leads to the conclusion that the library was located in the public school for girls in the parish of Candelária6. The acceptance of Guilhermina's library, the recognition of her teaching activity at Court, and the network of subjects she activated can be understood when, in 1878, the teacher receives 66 books from several people at Court, such as 22 copies donated by Councilor José Bento da Cunha Figueiredo. In that year, the library had a collection of 600 books and was praised as an "excellent idea that has deserved, and we hope to continue to deserve the coadjuvation of the public." In the same year the principal of Abilio College, Dr. Epiphanio José dos reis, donated 813 books from 30 different works. Of these copies, the teacher exchanged the repeated works with the publisher and book dealer Serafim José Alves, thus increasing the collection of her school library (SANTOS, 2020).

Also in the 1870s and 1880s, Guilhermina Azambuja Neves founded and directed the Collegio Azambuja Neves for girls in Parish of Engenho Velho, a situation that was not uncommon at the time, as shown by Borges (2008), several teachers who worked in public education were also teachers, directors and owners of establishments in private education. In 1882, he exchanges the chair of the Candelária feminine school with Adelaide Augusta da Costa who taught at the 4th feminine school of São Cristóvão. The following year, there is information of her death in June 1883.

The teacher Adelaide Augusta da Costa e Silva (before 1884 Adelaide Augusta da Costa) appears as an adjunct in 1873, being named a full professor in 1877, that is, after 4 years of training by practice. She succeeded teacher Guilhermina de Azambuja Neves in 1882 in the parish of Candelária; as mentioned, they exchanged the chairs they taught. The Ordinance of July 7, 1883 declares the lifetime service of the teacher in the Parish of Candelária, for having exercised the teaching profession for more than five years. According to Borges (2014), she probably died between 1884 and 1885.

Amélia Augusta Fernandes (Amélia Fernandes da Costa, post-marital name, probably) is listed as an adjunct teacher in the report of the Minister of Business of the Empire in 1873. In 1883 she temporarily governed the first girls' school in Parish of Sacramento due to the death of the previous teacher, and in the same year she was named teacher of the first girls' school in Guaratiba. In 1884 she provisionally governed the first girls' school in Santo Antonio and was later transferred to the first girls' school in São Cristóvão and finally removed to Candelária. In 1888 she had been exonerated from the chair of the parish of Candelária at the same time that she received the title of effective adjunct. The problem was solved when the teacher passed the exams of the Escola Normal da Corte, receiving the necessary qualification and the effective assignment to the public elementary school of Candelária in 1889.

This general picture, based on still incomplete and provisional data, shows us interesting information about the teachers of that locality. First, that the teachers not only taught in public schools, but also acted in several other spaces, whether in private initiative, in the Escola Normal da Corte, writing in the pedagogical press and, sometimes, integrated family networks inscribed in the field of education from different functions (delegate, inspector, writer, teacher, counselor). In the same way, they performed other functions in the educational field as members of evaluation commissions and proponents of improvement plans in education. Others were present in the discussions promoted by the Pedagogical Conferences, especially Professor Antonio José Marques, with his actions related to the mathematical field. They also participated in the production and dispute of knowledge that involved the 19th century school, writing and having approved books and works for teaching. Besides being aware of the new teaching apparatuses, such as the institution of school libraries.

We can also see the mobility that teachers had between the schools of the parishes of the Imperial Court, staying in some for a short time, as the teacher José Antonio de Campos Lima who taught in the male school of Candelária for 2 years. Or having a long tenure, like the teachers Catharina Lopes Coruja (9 years) and Guilhermina Azambuja Neves (7 years). Appropriating the reflections of Schueler and Texeira (2009) we can affirm that the teachers of the Parish of Candelária, as well as other teachers of the Court, when producing works, books, compendia, articles for specialized magazines or papers for the Pedagogical Conferences, and when participating in political activities and public functions, contributed to the conformation of an ideology of the nation, emphasizing the being Brazilian and the construction of nationality through the school, the knowledge and the compendia and, of course, their own intellectual responsibility as educators. Therefore, the teachers not only fulfilled the function of educating, but also constituted themselves as intellectuals of Brazil Empire. Through their diverse actions in the political and educational context they disputed and conformed knowledge for the construction of the nation.

In the decade of 1871, many teachers worked in the public sector and, many times, concomitantly, in the private sector as well. But, unlike the other urban parishes, the parish of Candelária had the highest number of enrollments in public schools: about 80% of the population under 14 years of age attended public schools. Only 20% occupied the seats of private educational establishments. We need to consider that there were only two public schools (during the whole period analyzed), one for each sex, and from 1880, only the girls' school, and that the population of Candelária was smaller compared to other parishes. Consequently, it had a reduced number of potential population to attend elementary school according to the educational legislation. In 1848, in the Jornal do Commercio, there was an ad for Girls’ School in 59 Candelária street which, as a differential, informed that it also taught female slaves:

The principal of the girls' school in 59 Candelaria street, communicates to the respectable public and to the parents, that it opens its establishment on January 10 of this year, where it continues to receive external and internal girls, and to teach reading, writing, counting, national and French grammar, Christian doctrine, etc., drawing, music, dancing, sewing, embroidery of all qualities and of gold, marking of all qualities, tapestries, etc. (JORNAL DO COMMERCIO, Ano XXIII, nº4, January 4, 1848)

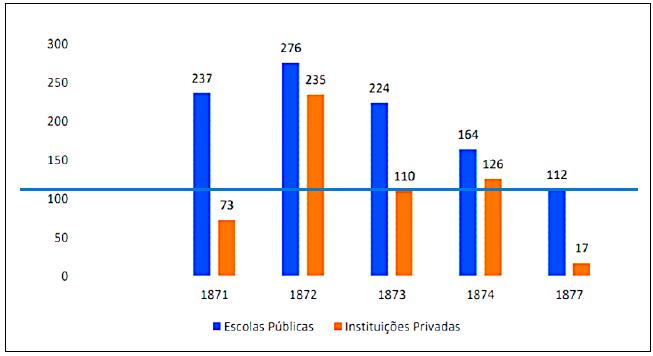

The advertisement indicates that the educational legislation that forbade the slaves to attend school was being circumvented. It was probably an education for certain interests of the slave owners, and, as it says, the practice was for "all teaching" and not only the primary education offered at the school. This may be an indication of the diversity of the private network in the place and in all the capital of Brazil in that period. In general, the Parish of Candelária, in 1870, had 3 private educational institutions, decreasing in the following year to 1, having its peak in the years 1872 with 6 establishments and 1873, with 7 establishments and ending in 1877 with only 1. This way, school enrollment data can be systematized:

Candelária had few private schools, if compared to some urban parishes of the Court, like Glória or Santa Rita. The number of private schools was closer to the Freguesia do Engenho Velho, even surpassing it, as in the years 1872 and 1873. We believe that the same reasons reported as problems for the maintenance of public schools (low population density, lack of space, influence of commerce, high rents, mobility of people, etc.), were those that affected the private schools and their permanence in the region. Most of the private schools were primary schools, and there was only the record of one secondary school for girls in the sources, maintained by the teacher Emília Cabral in the year 1871 (AGCRJ, 1872, codice-12.4.15 p. 13,14 and 15).

Regarding the students of this private school, the data brought by the delegate Dr. João Carlos da Silva Maya, referring to the year 1871, are very superficial, addressing age, nationality, religion and gender, for example. According to him, there were 8 boys in a primary school (one was younger than 7 years old and the others younger than 14), of these, 6 students were Brazilians, two foreigners and all claimed to be Catholics. Of the 35 boys attending the school in Rua do Rosário, 33 were over 14 years old and two under 7 years old, all declared Catholic, and only 2 were foreigners. The primary and secondary school for girls had 21 students. Regarding nationalities, only two were foreigners and nineteen were Catholics and two were non-Catholics (AGCRJ, 1872, codice-12.4.15 p. 13, 14 and 15). Part of the educational demand for boys in the parish was met by private initiative, since the lack of students in the public school was the justification for the closing of the institution and the number of private schools for boys was larger than the public schools. The presence of foreigners in all classes corroborates the parish's characteristic, where there was a considerable number of people from other countries.

Part of the private network of the parish of Candelária established formal ties with the public sector through the practice of subvention, very common throughout the 19th century in Brazil. The subsidy consisted of public funding of tuition fees for poor pupils in private primary schools (LIMEIRA, 2010). In the Parish of Candelária in the year 1878, we identified that two private teachers received public subsidies for the maintenance of their private schools, for boys and for girls. These were Luiz Thomaz de Oliveira and Catharina Lopes Coruja (PASCHE, 2014). Catharina also appeared in the list of public teachers of the Court, which may indicate an accumulation of the functions of public and private teacher.

Final considerations

In face of a provisional arrangement, supported by the theoretical-methodological operation of micro-history, through the selection of specific sources, it was possible to make reflections about the process of schooling in the capital of Brazil, making the data very specific about a locality (urban, commercial and central). In this sense, the investment developed here is part of the movement that has been marking more recently the field of History of Education, from researches that explore more and more specific geographical clippings, with the intention of investigating singularities and local experiences. We emphasize here the importance of noticing the great diversity formed by the urban and rural parishes of the capital of Brazil's Empire and the heterogeneity found in the subdivisions of these regions, a problematization that indicates the amplitude and complexity of the educational actions developed in the Brazilian Eighteenth Century.

Based on this investment we can consider that the school demand in the Parish of Candelária was well attended, remaining stable throughout some years of the 1870s, which did not prevent the private initiative to act. It is necessary to consider, in the specific case of Candelária, the hypothesis that some of its residents could attend classes in other parishes, such as Santa Rita (which had the Girls' School very close to the girls' school of Candelária). Thus, this public would enter into the statistical data of potential school public in Candelária, but not into their respective enrollment rates, let alone constitute incentive public for local private establishments. Based on this assumption, we understand that not necessarily the population under 14 years of age of Candelária was attended in its 2 public schools or in the few private establishments that existed there (SANTOS, 2020, p.179).

The enrollment of girls remained higher than boys, a fact that influenced in the 1880s the end of the public school for boys. Such disparity between the sexes, in the concept of enrollment, could be due to the frequency of boys in schools in other regions, or in private schools, or in informal classes, or even in the so-called school palaces which were in the adjacencies? These boys existed as a school demand located in Candelária, as the numbers, including the 1872 census, point out, but they did not attend classes there. Maybe were they dedicated to the typical commercial activities of the region as clerks, delivery boys, shoeshine boys, etc?

As far as the teaching staff of the public school is concerned, we noticed the presence and performance of 8 teachers throughout these decades, some of them remaining teaching for a long period. At the same time, we saw that these teachers had a diversified performance at Court through the publication of manuals/books for use in elementary school, defending their convictions in the pedagogical press, working in private schools and in the Normal School, also as members of evaluation commissions and proposers of improvement plans in education, others were present in the discussions promoted by the Pedagogical Conferences.

Regarding the religious presence in the region, we initially believe that it could have generated formal schooling actions, as there were in several other locations in the Imperial Court, as indicated by the studies of Pasche (2014). The existence of private colleges maintained by Catholics was something quite common, such as the Collegio Imaculada Conceição that was created in 1854 and operates until today and others such as Collegio do Mosteiro de São Bento, Collegio do Padre Guedes or the Collegio Episcopal São Pedro da Alcântara. But the religious initiative of Candelária promoted school attendance only through the creation of an Asylo da Infância Desvalida da Candelária, which was proposed in 1881 and finalized only in 1900, but whose location was established in the neighboring parish of São Cristóvão and not in the locality itself (SANTOS, 2020).

More broadly, throughout the Empire, especially in the 1870s and 1880s, education became an incisive agenda of governmental actions and discussions in society in general. The reason for several solutions, in order to educate and discipline a heterogeneous population that constituted the Brazilian nation. The task of education was related to the construction of Brazil itself, through the unification of the territory and the people, inspired by international experiences in some European and American countries. The wider dissemination of education would form the urban and civilized man, ready for the actions arising from capitalism and solution to the productivity problems arising from the abolitionist laws. Such actions would elevate the then newly independent nation into the hall of modern and civilized countries. And as a result of the educational actions that were already being expanded from the second half of the 19th century on, the elementary school was elected as one of the fundamental elements for Brazil to progress. Thus, the complexity, heterogeneity, and inequality of the school fabric of the Imperial Court was being spun together with the urban culture itself, which was set to the projects of modernity. Actions that sought solutions to the traditional ways of life, to the population growth of a free, mestizo, immigrant, and poor layer, and the structural problems of the society, such as the worsening of the abolitionist and republican forces, besides the sanitation issues (yellow fever, the housing crisis, etc.), that marked the last decades of the monarchy (GONDRA; SCHUELER, 2008).

In this context, the goal was to question the way from which the schooling process was constituted in the parish of Candelária between the 1870s and 1880s. We can say that it was constituted between the bells of the Church of Nossa Senhora da Candelária and the sounds of commercial transactions that dictated the order of that region. The parish presented a public and private education process crossed by its small territorial extension, low population density, the consequences of the characteristics of a commercial area and the modernizing and progressive interventions of the final decades of the Empire. Therefore, the research developed explored a region of the city little mentioned in historical studies and presented scattered aspects of what is configured as the complex process of schooling in Brazil of the 1800s. Other times, other ways of experiencing school, but that say a lot about the ways we still deal with it today and with this phenomenon that marks each one of us, education.

REFERENCES

ABREU, Mauricio de. Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Pereira Passos, 2013. [ Links ]

BASTOS, Maria Helena Camara. Reminiscências de um tempo escolar. Memórias do professor Coruja. Revista Educação em Questão, Natal, v.25, n.11, p.157-189, jan./abr. 2006. [ Links ]

BORGES, Angélica. Ordem no ensino: A inspeção de professores primários na Capital do Império brasileiro (1854-1865). 2008. 288f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2008. [ Links ]

BORGES, Angélica. A urdidura do magistério primário na Corte Imperial: um professor na trama de relações e agências. 2014. 415f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2014. [ Links ]

BOSCHI, Caio César. Os leigos e o poder: irmandades leigas e política colonizadora em Minas Gerais. São Paulo: Editora Ática,1986. [ Links ]

COARACY, Vivaldo. Memórias da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. São Paulo: Itatiaia, 1988. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, João da Costa. A cidade do Rio de Janeiro e o seu Termo: ensaio urbanológico. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1933. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Maria Isadora Caldas; SOARES, Flávia dos Santos. O lugar da mulher na produção de material escolar: análise de impressões jornalísticas do século XIX sobre livros didáticos de Guilhermina de Azambuja Neves. In: 2º Encontro Nacional História e Parcerias, 2, 2019, Rio de Janeiro. Anais..., Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Veiga de Almeida, 2019. [ Links ]

FRIDMAN, Fania. Donos do Rio em Nome do Rei. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, 2017. [ Links ]

GIL, Natália de Lacerda. A produção dos números escolares (1871-1931): contribuições para uma abordagem crítica das fontes estatísticas em História da Educação. Revista Brasileira de História. São Paulo, v.29, n.58, p.341-358, 2009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-01882009000200005 [ Links ]

GONDRA, José Gonçalves; SCHUELER, Alessandra Frota Martinez de. Educação, poder e sociedade no Império Brasileiro. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

GONDRA, José Gonçalves. Telescópio, microscópio, incertezas: Jacques Revel na história e na história da educação. In: LOPES, Eliane Marta Teixeira e FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes de (Orgs.). Pensadores Sociais e História da Educação, volume 2, Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2012. [ Links ]

LIMEIRA, Aline de Morais. O comércio da instrução no século XIX: colégios particulares, propagandas e subvenções públicas. 2010. 282f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação), Faculdade de Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2010. [ Links ]

LIMEIRA, Aline de Morais; GONDRA, José Gonçalves. Nas escolas da capital brasileira: matrículas nas freguesias urbanas e rurais (1870). In: LIMA, Alexandra, LIMEIRA, Aline, LEONARDI, Paula. Um mar de escolas: instituições e pesquisas na História da Educação. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Appris, 2022 [ Links ]

REVEL, Jacques (org.). Jogos de Escala: a experiência da microanálise. Tradução Dora Rocha. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 1998. [ Links ]

REVEL, Jacques. Micro-História, macro-história: o que as variações de escala ajudam a pensar em um mundo globalizado. In: Revista Brasileira de Educação, v.15 n.45 set./dez. 2010. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782010000300003 [ Links ]

SANTOS, Aline Machado dos. Entre o soar do sino e as transações comerciais: as escolas primárias da Freguesia Urbana da Candelária (Capital Brasileira, 1870-1889). 2020. 284f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2020. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Francisco Agenor Noronha. As Freguesias do Rio Antigo: vistas por Noronha Santos. Rio de Janeiro: Edições O Cruzeiro, 1965. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Francisco Agenor Noronha. Crônicas da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Padrão livraria e Editora,1981. [ Links ]

SENRA, Nelson. Uma breve história das estatísticas brasileiras (1822-2002). Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2009. [ Links ]

SCHUELER, Alessandra Frota Martinez de. Entre escolas domésticas e palácios: culturas escolares e processos de institucionalização da instrução primária na cidade do Rio de Janeiro (1870-1890). Revista Educação em Questão, Rio Grande do Norte, v.23, n.9, p.160-184, maio/ago, 2005. [ Links ]

SCHUELER, Alessandra Frota M. de; TEIXEIRA Giselle Baptista. Civilizar a infância: moral em lições no livro escolar de Guilhermina de Azambuja Neves (Corte imperial, 1883). Revista de Educação Pública, Cuiabá, v.17, n.35, p.563-577, set.-dez. 2008. [ Links ]

SCHUELER, Alessandra; TEIXEIRA, Gisele. Livros para a escola primária carioca no século XIX: produção e circulação e adoção de textos escolares de professores. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v.9, n.20, 137-164, 2009. [ Links ]

PASCHE, Aline de Morais Limeira. Entre o trono e o altar: sujeitos, instituições e saberes escolares na capital do império brasileiro (1860 a 1880). Tese. (Doutorado em Educação) Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2014. [ Links ]

TEIXEIRA, Gisele. O Grande Mestre da Escola: Os livros de leitura para a Escola Primária da Capital do Império Brasileiro. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. 2008. [ Links ]

2We conducted a survey in three recognized journals in the area: Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Revista História da Educação and the journal Cadernos de História da Educação, as well as in the CAPES theses and dissertations database and in the Scielo database. There is the recent study by SANTOS, Aline Machado. Between the ringing of the bell and the commercial transactions: the elementary school of the urban parish of Candelária (Brazilian capital, 1870-1880). Master's Dissertation. College of Education, University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, 2020. In the survey, we located tangential studies, which do not address Education, but are important, such as: LOPES, Janaina Christina Perrayon. Marriages of slaves in the Parishes of Candelária, São Francisco Xavier and Jacarepaguá: a contribution to the patterns of matrimonial sociability in Rio de Janeiro (1800 - 1850). Master's Dissertation. College of History, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2006.

4The right to citizenship in the Empire of Brazil, since the Constitution of 1824, was established on a census basis, and divided the citizens (people born in Brazil and naturalized foreigners), according to their incomes, into three categories: citizens who could neither vote nor run for office, because they did not have the minimum income required to do so; citizens who could only vote (because they earned the minimum required) and citizens who could vote and run for office. The "naive" (born in Brazil), according to income requirements, could move up the three positions in the hierarchy of Brazilian citizenship, but the freedmen (with the exception of Africans) could only be, voters. That is, former slaves were politically restricted. And the children of Africans born in Brazil ("Creole" slaves), could become "forros", and with this, enter the base of the pyramid of citizenship in the Brazilian empire. Free individuals, however, lacking the other fundamental attribute for the full exercise of citizenship in that society (property), were considered non-active citizens within the limits of civil rights, and were denied political participation. See CARVALHO, José Murilo de and CAMPOS, Adriana Pereira (Orgs). Perspectivas da cidadania no Brasil Império. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2011; CARVALHO, José Murilo de. I- A Construção da Ordem. A Elite Política Imperial. II- Teatro das Sombras. A política Imperial. 2nd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2006; MATTOS, Ilmar Rolhou. The Saquarema Time. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2004.

Received: August 20, 2022; Accepted: November 28, 2022

texto em

texto em