Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-186

Artigos

Education and civics in Uberaba/MG during the Vargas Era (1930-1945): perceptions from the newspaper Lavoura e Comércio1

1Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (Brasil). anelise.oliveira@uftm.edu.br

2Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (Brasil). ilana.peliciari@uftm.edu.br

3Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (Brasil). sandra.mara.dantas@uftm.edu.br

This text aims to understand the educational scenario in the city of Uberaba, Minas Gerais, during the Vargas Era (1930-1945), and, more specifically, during the period of the Estado Novo (1937-1945). This temporal cut occurred because it was a period in which Brazil experienced Getúlio Vargas' state-regime regime, characterized by a centralizing, authoritarian and nationalist policy. To this end, it has the Lavoura e Comércio newspaper, the main uberabense periodical in circulation at the time as its source. The results indicate that the articles contained in Lavoura e Comércio are in line with the perception of education in the state government, in which that constituted an important instrument in the propagation of values based on the feeling of national unity, civic spirit, and, cult of physical exercises, both at school and outside, through the idealization of a society considered healthy from a physical and moral point of view.

Keywords: Education and civics; Vargas Era (1930-1945); Uberaba

Este texto objetiva compreender o cenário educacional na cidade de Uberaba, Minas Gerais, durante o período da Era Vargas (1930-145), e, de forma mais específica, durante o período do o Estado Novo (1937-1945). Tal recorte temporal ocorreu por ser um período no qual o Brasil vivenciou o regime estadonovista de Getúlio Vargas, caracterizado por uma política centralizadora, autoritária e nacionalista. Para tanto, possui como fonte o jornal Lavoura e Comércio, principal periódico uberabense em circulação na época. Os resultados indicam que as matérias contidas no Lavoura e Comércio vão ao encontro da percepção que se tinha de educação no governo estadonovista, no qual aquela constituía importante instrumento na propagação de valores pautados no sentimento de unidade nacional, civismo, e, culto aos exercícios físicos, tanto na escola quanto fora dela, por meio da idealização de uma sociedade considerada saudável do ponto de vista físico e moral.

Palavras-Chave: Educação e civismo; Era Vargas (1930-1945); Uberaba

Este texto tiene como objetivo comprender el escenario educativo en la ciudad de Uberaba, Minas Gerais, durante la Era Vargas (1930-1945), y, más especificamente, durante el período del Estado Novo (1937-1945). Este corte temporal se produjo porque fue un período en el que Brasil vivió el régimen de estado-régimen de Getúlio Vargas, caracterizado por una política centralizadora, autoritaria y nacionalista. Para ello, tiene como fuente el diario Lavoura e Comércio, principal periódico uberabense en circulación en ese momento. Los resultados indican que los artículos contenidos en Lavoura e Comércio están en línea con la percepción de que hubo una educación en el gobierno del estado, en la que constituía un instrumento importante en la propagación de valores basados en el sentimiento de unidad nacional, el civismo. y, el culto al ejercicio físico, tanto en la escuela como fuera, a través de la idealización de una sociedad considerada saludable desde el punto de vista físico y moral.

Palabras clave: Educación y civismo; Era Vargas (1930-1945); Uberaba

Introduction

During the first decades of the Brazilian Republic (1889), debates regarding education highlighted the need for a “modernization” of teaching, in line with projects that proposed ways of restructuring society and aimed to respond to urban social problems, such as housing a hygiene.

In the 1920s, such debates were part of the reformist speech of the Escola Nova (New School) movement that defined new ways for the running of educational institutions, whose pedagogical discourse was based on a standardizing way of teaching, compatible with the interests of certain segments of society. The escolanovista model subsidized a series of educational projects, which had the purpose of adjusting the popular social layer to the habits of life and work designed by the ruling authorities and by the intellectual elite at the time. Mate (2002, p. 41) points out a close relationship “between the intended construction of a harmonious, orderly and productive social body and the movement of building a schooling system that had in the appropriation of escolanovistas’ ideas its main form of expression and in the reforms its realization.”

In the perspective of the construction of new concepts about education and its role in society, the most systematic development of the Brazilian national education system began to take shape in the 1930s. Indeed, the institutionalization of the Ministry of Education and Health Affairs, in 1930, during the government of Getúlio Vargas (1930-1945) (1951-1954)2, is an example of how education would become the scene of increasingly intense interventions by the Executive Power. Said government was initiated by an armed coup that put an end to the oligarchic system of the First Republic (1889-1930), and, in a broader sphere, has been characterized, among other factors, by the decline of regional oligarchies, by the development of the capitalist industrialization and urbanization process, and by the centralization of political power.

For this work, the first Vargas government (1930-1945) is of interest, especially the dictatorial period called Estado Novo (New State) (1937-1945), when a growing centralization of the educational apparatus in the hands of the State is observed, in which the imposition of a formal patriotism shall become constant in everyday social practices, both inside and outside the school space. Thus, the aim of the present work is to understand how the educational process took place in the city of Uberaba, during that period, having as a source the Lavoura e Comércio newspaper, the main local periodical in circulation at that time. It is understood that the periodical press can be an important instrument of analysis, “since its peculiarity is to reveal the movement of history (be it educational, social, commercial, industrial, political, literary, economic, cultural, etc.) in its daily dynamics, as seen by those who decide what to report” (ARAÚJO; INÁCIO FILHO, 2005, p. 177).

The newspaper Lavoura e Comércio was founded in 1899, by “the biggest farmers and traders” of Uberaba (MENDONÇA, 1974, p.79), being one of the main newspapers in circulation during the first half of the 20th century in the region of Central Brazil3. The periodical was characterized by being “of a conservative tendency, which reported events according to an elitist-Christian conception, represented in Uberaba by the farmers and the large catholic merchants” (OLIVEIRA, 2017, p. 26). Not by chance, the director of the newspaper in the researched period, Quintiliano Jardim, would support the armed coup of 1930, which initiated the Vargas government, and later, the Estado Novo (New State).

Inside the Lavoura e Comércio newspaper: education and civility in Uberaba

The Estado Novo (1937-1945), as an authoritarian regime, resulted from a political “self-coup” led by Vargas, which began with the implementation of the Nazi-fascist-inspired Constitution of 1937. With the implementation of the Estado Novo, and with the support of the Armed Forces, Vargas instituted a series of centralizing measures, such as the dissolution of the Parliament, the extinction of political parties, the suspension of civil liberties, and the prohibition of the right to strike. In order to “forge a strong sense of national identity, an essential condition for the strengthening of the national state,” the regime began to gradually invest in the cultural and educational fields (PANOLFI, 1999, p. 10).

In the cultural sphere, the government’s interference was notorious through prior censorship of the media, and a political propaganda that could legitimize the actions in force. The organization of the organs that produced Vargas’ political propaganda was inspired by Nazi-fascist propaganda, in terms of a simple language that could reach the masses. Characteristics such as “promises of unification and national strengthening”, ideological unity, “promises of material benefits to the people” (employment and salary raises, for example), and “emotional appeal” were present in both Nazi-fascist and Vargas’ propaganda (CAPELATO, 1999, p. 167-168).

In 1939, the Department of Press and Propaganda (DIP) was created with the purpose of monopolizing the media and disseminating the authoritarian guidelines of the regime, which occurred mainly through the radio and the press. The DIP operated “as an omnipresent organism” in all spheres of society, covering “from children’s primers to national newspapers, through theater, music, cinema and even in carnival” (VELLOSO, 2010 p. 169). In this context, the DIP advertised the parties of civic-patriotic nature that took place in Brazilian cities.

The media all over the country were compelled to reproduce the official speeches and to report in favor of the government, and about 60% of the articles published in these information vehicles we provided by the official bodies (CAPELATO, 1999).

In Uberaba, the Lavoura e Comércio newspaper gave broad support to the measures proposed by Vargas, and publicized the speeches he made on commemorative dates, inaugurations and visits. Such oral presentations were the basic content of the political propaganda. Thus, the periodical published articles referring to civic festivals and official speeches, related to symbolic dates from the point of view of patriotism and national unity, such as, for example, the implementation of the Estado Novo, the Homeland Week (celebrated during the week of September 7th, Brazilian Independence Day), Flag Day, and Christmas dates, due to the birthday of the president or the people in the government. The publications were not restricted to official speeches, since the journal’s editors, columnists, and guest writers also wrote for the benefit of the state.

In the publication of November 12th, 1941, the Lavoura e Comércio newspaper published Vargas' official speech in commemoration of the fourth anniversary of the Estado Novo. The explanation took up the entire first page of the newspaper plus part of the third page, from a total of six pages, ending like so: "Generations go by, men die, but the Homeland lives on, eternal and imperishable, in the love of its children, in the heroism of its soldiers. I raise my glass - for the glory of our Army, for the happiness of our hard-working and good people, for the indestructible unity of the Homeland" (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 11/12/1941, p. 3). The excerpt from the speech refers to a maternal feeling of nationality, in which conflicts are supplanted by the harmonious conception of society. The population, in this sense, appears as passive and in conformity with the transformations promoted by the government, and especially by the Armed Forces.

Another date intensely highlighted by the periodical was the birthday of Getúlio Vargas, April 19th. In 1943, on that day, almost half of the edition was dedicated to the chairman. It’s timely to say that, in the article, the official discourse was accompanied by an amount of photographs which depicted Vargas in daily situations, which were followed by the captions: “During his rest, HE also appreciates the photographic art”, “HE having some coffee”, “The president receiving from a native the friendship trophy”, “HE during a walk with the children” (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 04/19/1943, p.1-3). Although the photos are not shown here, one can see in the subtitles an attempt to bring the statesman closer to the population, humanizing him, based on “real life snapshots” that are common to all people, regardless of their social position, such as drinking coffee. In this perspective, Vargas’ image is sustained through symbologies and affectivities that collaborate to instill in the population a feeling of identification. More specifically, the last two captions - “The president receiving from a native the friendship trophy”, and “HE during a walk with the children” - are representative because they address, respectively, the idea of integration and racial harmony (characterized by the native) and the conception of youth as the future and progress of the nation (portrayed by the children).

Vargas’ birthday was widely celebrated in Uberaba, with parades, sports games and several other tributes, both from public and private institutions. Among the solemnities, the newspaper highlighted the one held by Grupo Escolar Brasil, one of the city's main schools. The event brought together hundreds of students “in the inner courtyard of the model school”, with the presence of the school principal, teachers and the municipal school inspector. The celebration included the reciting of poems by two students, the playing of the national anthem and the speech of the official orator, a teacher from the school, who “outlined in rapid strokes, the profile of President Vargas, giving a summary of his remarkable achievements, as the greatest statesman that Brazil has seen at the head of its destiny” (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 04/20/1941, p. 4). The words used reveal the school environment as a vehicle for dissemination and praise of the estadonovista regime, and the cult of the president. In this sense, through schooling, values and ideologies were transmitted to children and young people in order to legitimize the power.

In the educational field, the reforms developed by the Ministers of Education and Health, Francisco Campos (1930-1932) and Gustavo Capanema (1934-1945), from Minas Gerais, portrayed a new way of conceiving the role of schooling in the country, through an education meant for the elites and a moral and disciplinary formation.

Following largely the projects initiated by Campos, Capanema established a "conservative modernization" in education during his 11 years as head of the Ministry of Education and Health:

Modernization manifested itself in the desire of creating a strong and comprehensive educational system and in the constant concern with cultural and artistic activity. The conservative side manifested itself in many different ways: by the concentration of power, which did not allow the organization of free and autonomous educational and cultural institutions outside of ministerial tutelage; by the basically statist, if not utilitarian, conception of culture and the arts (SCHWARTZMAN, 1985, p. 171).

As pointed out earlier, the newspaper Lavoura e Comércio gave broad support to the measures proposed by Getúlio Vargas, and therefore to the men who made up his government, among whom was Gustavo Capanema. In the edition of August 08th, 1936, the periodical brought a publication celebrating the minister's birthday:

In the Ministry of Education and Public Health, to which he was elevated as a result of his merits and his fair culture, Mr. Gustavo Capanema has been one of the factors in the formation of the new Brazilian mentality, trying to endow the country with an educational apparatus at the height of its greatness and its importance in the concert of the nations of this continent. "Lavoura e Comércio", which is ranked among the admirers of the young Minister of Education, sends him, on the occasion of his birthday, its sincere congratulations, wishing for his happy and peaceful longevity. (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 08/08/1936, p. 1, newspaper highlights).

The previous passage extols Capanema as an important figure in the consolidation of the educational ideology. By referring to the minister as "one of the factors of formation of the new Brazilian mentality," the periodical probably makes mention of the elite intellectuals who participated in the elaboration of the policies in the country, which had been proposing, since the 1920s, transformations in the cultural and educational spheres from "a pedagogical proposal based on concepts of progress and development that would influence the uniform formation of mentalities" (MATE, 2002, p. 137). The “Ministério Capanema”, also called "Ministério dos Modernistas" (“Modernists’ Ministry”, in literal translation), included names such as Anísio Teixeira, Lourenço Filho, Mário de Andrade and Carlos Drummond de Andrade, elite intellectuals who elaborated documents and projects to explain and spread the Brazilianness (brasilidade) and the Brazilian identity based on cultural values considered legitimate to be appropriated by society, in an authoritarian and standardized way.

It should be noted that Capanema took notice of the congratulation published by Lavoura e Comércio, and issued a thank-you note to the periodical, stating "being very grateful to this brilliant newspaper for the kind expressions with which it distinguished me on the occasion of my birthday" (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 08/21/1936, p. 3). The type of language used suggests a certain closeness of the newspaper to the minister, implying the existence of friendly relations between the two at times prior to the publications cited.

In the educational reforms undertaken, in particular the Organic Law of Secondary Education, Capanema emphasized the "formation of a patriotic conscience," stressing the importance of preparing a portion of the population - the elite youth - for the management of the country, since they should "assume the major responsibilities within society and the nation" (BRASIL, 1942a).

Specifically, primary education was subdivided into elementary education, lasting four years, and supplementary education, lasting one year. Secondary education was divided horizontally into secondary and technical-vocational. Secondary education, whose curriculum was characterized by an emphasis on encyclopedic knowledge, was structured in two cycles. The first, the junior secondary, lasted four years, and the second included two parallel courses: the classical and the scientific, lasting three years each.

Since 1931, entrance exams for junior high school were mandatory in schools that offered secondary education and had to be offered in two periods: one in December and the other in February. These exams reinforced the exclusionary nature of education, insofar as they selected the students who would attend high school and imposed barriers to access for those who were considered to be ineligible4. Saviani (2007, p. 269) points out the centralizing and selective character of educational measures:

From the point of view of conception, the set of reforms had a centralist character, strongly bureaucratized; dualist, separating secondary education, intended for the driving elites, from professional education, intended for the driven people and granting only the secondary branch the prerogative of access to any higher level career; corporatist, as it closely linked each branch or type of education to the professions and trades required by the social organization.

Thus, the Brazilian educational system did not present itself in an egalitarian way for all citizens, and its access was directly associated with the social stratum to which they belonged. While the elite were provided with an "intellectual" preparatory education aimed at higher education, which had as its aim the reproduction of a Catholic citizen, the valorization of the classical humanistic culture and military discipline, the lower social classes were provided with an industrial, commercial and agricultural education, aimed at market production. This can also be seen in the 1940 edition of the Uberaba periodical, when it emphasized that secondary education "provides the passcode that will allow young people to enter the future professions they aspire to. It is this which provides the youth of the country with the baggage of knowledge indispensable for the acquisition of future and more specialized knowledge" (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 06/13/1940, p. 2).

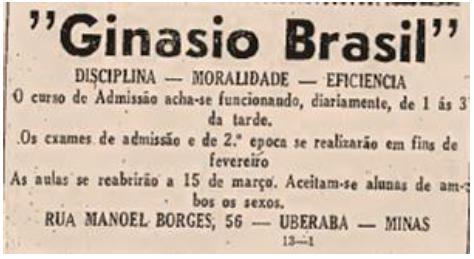

Students were expected to develop skills in line with the assumptions of the estadonovista ideological policy, that is, a formation focused on the sense of responsibility, the cultivation of moral and civic values and service to the homeland. This ideological policy is noted in the advertisement of the school "Ginásio Brasil", published in Lavoura e Comércio on January 17th, 1940, which made use of three nouns to assertively qualify the teaching procedures to which it was destined:

Source: Codiub Lavoura e Comércio collection. Available: http://www.codiub.com.br/lavouraecomercio/pages/main.xhtml. Accessed: 10 mar. 2021.

Picture 1 Advertisement "Ginásio Brasil" (Lavoura e Comércio, 17/01/1940).

The previous advertisement shows the kind of behavior that the school expected from its students, adjusting and preparing them for the society that was intended to exist, in the specific context of the authoritarian regime. The idea that schooling could solve the country's political and social problems was recurrent during the Vargas government. An example of this was the creation of the National Crusade of Education, in 1932, a movement that extended itself into Estado Novo and had as its purpose the reduction of the illiteracy rate and the creation of schools, since one should "erase the shameful stain of illiteracy that degrades and vilifies Brazil" (PAIVA, 2003, p. 131).

With an excluding and prejudiced bias in relation to the illiterate, aiming to raise the cultural level of the poorest layers of the population in accordance with the elitist assumptions, the National Crusade for Education had as main collaborators the Armed Forces and the conservative sectors of industry, commerce and private individuals (PAIVA, 2003). Through these collaborators, also called partners, funds were collected for the diffusion of education and for the installation of schools, based on propaganda (printed newspaper and radio, mainly). The movement was characterized by the voluntary work of the sectors that promoted it. In this context, students from wealthy social classes that attended school were also called to participate in the literacy campaigns, and it was up to them to "adopt" children of low social status, thus evidencing a stereotypical welfarism, as it appears in the pages of Lavoura e Comércio:

The most exciting and moving aspect of this patriotic and holy crusade is in the most efficient and affectionate action developed by wealthy students of both sexes, from all schools and colleges, public and private, as sponsors of poor students or disadvantaged children, so that, with the help that they need, they can be properly educated and reach the level of education compatible with their social position [...] (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 05/21/1937, p. 1).

The previous passage corroborates the assistentialist, philanthropic and humanitarian character of the National Crusade for Education. Right at the beginning of the passage, one can see the analogy of the movement, called "holy crusade", to the military conflicts organized by Catholics during the Middle Ages, which aimed to reconquer sacred places and propagate Christianity in societies considered heretical. In other words, one can say that the National Crusade of Education had the purpose of bringing progress and civilization where there was backwardness and barbarism. It is also evident the intervention of the elite, more precisely "the affluent students of both sexes" designated here as technically prepared for educational construction. The lower social strata was not destined to receive just any instruction, but an instruction inherent to their position in the structural hierarchy of society, according to their "natural aptitude". The movement, in this sense, focused on the interests of the higher social stratifications, and did not constitute a tool to modify the educational reality of the country.

In the same publication, the newspaper cited the political specificity of the National Crusade for Education, pointing out that the approximation of distinct social classes collaborated to "the political aspect, for the perfect unification of the spirit and of the national feeling, primordial factor for the understanding of the democratic ideal and for the security and stability of the regime" (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 05/21/1937, p. 1). One notices the valorization of a moral and civic education based on the appeal to patriotism, and in the molds of what is intended to form in terms of a citizen. The previous fragment shows that this education should contribute to national security against possible enemies of the government, a subject that will be dealt with later. It is noteworthy that the newspaper refers to the authoritarian period as democratic.

During the Estado Novo, pre-military education appeared as an important tool in the diffusion of an authoritarian and disciplinarian policy. Compulsory for male students enrolled in the first cycle of secondary school, pre-military instruction was implemented under the influence of Brazil's entry into World War II (1939-1945). It comprised notions concerning “the organization and military life, the elementary instruction of united order without weapon and initiation in the technique of shooting.” (BRASIL, 1942b). According to the same document, all educational establishments with more than fifty students should maintain a pre-military instruction center, whose instructors would be designated by the Commander of the Military Region in which the school was inserted. Despite the obligation imposed by law, pre-military education was never fully implemented, being withdrawn in 1946 by General Dutra, then president of Brazil. Its extinction, according to Horta (2012), occurred not due to "democratic winds", but because it became unnecessary to the Army, which already controlled scholar Physical Education in the country.

In fact, since 1937, the referred curricular component was organized and directed by the military, through the Physical Education Division, which was subordinated to the Ministry of Education and Health. Parallel to that division, the National School of Physical Education and Sports was created, responsible for training teachers specialized in the area, in order to act "on the collectivities, instilling in them the spirit of order and discipline" (DUTRA, 1941, apud HORTA, 2012, p. 77).

The presence of the Armed Forces in the schools evidenced the concern with a supposedly “healthy” formation from the physical and moral point of view of the students. However, beyond the school sphere, Physical Education was also present in the daily social practices of the period, as observed in the column “Nota do Dia” (“Note of the Day” in literal translation), from Lavoura e Comércio:

The world is living at this time the supreme moment of the strong man of body and spirit. [This is the age of physical education, allied to the formation of the spirit, one as a complement of the other. [...] We are transforming silly poets into muscular athletes, platonic patriotism of civic speeches into the patent reality of a strong and respected nation (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 08/30/1941, p. 6).

The previous excerpt indicates Physical Education as a tool for moral and spiritual improvement of the individual, in order to implement, in the society, disciplinary actions that would contribute to the formation of a productive and physically prepared population against possible threats to the State. One can even observe in the excerpt some pejorative language when dealing with the poet as a person who needed to be concerned with the perfection of the body, and not only the intellect.

Horta (2012, p. 31), when discussing the Army's national mobilization measures, clarifies: "it is undeniable that the idea of national security, conceived not only as external defense, but also as defense against internal enemies, occupied an important place in defining the role to be played by the Brazilian military in this period. The internal enemies, of which the author speaks, encompassed all those contrary to the state ideology in force; for example, people identified as communist sympathizers. This fact can be verified in the publication of April 3rd, 1936 of Lavoura e Comércio, which brings the exoneration of five higher education professors, "for exercising subversive extremist activities", besides "several doctors, professors, and other employees accused of co-participation in the communist movement" (p. 3).

Also in relation to the column “Nota do dia”, mentioned above, it was stated that the attention given to Physical Education occurred not only in the country's capitals, but also in the countryside cities, where the "renovating appeal of nationality was promptly answered by the city halls, which built sports squares and distributed gym teachers to the schools" (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 08/30/1941, p. 6). Here, when emphasizing the construction of proper places for the practice of physical exercises, the periodical is probably referring to a specific place in the city of Uberaba, the Physical Culture Center. Founded in 1936, the place with a suggestive name had as its objective "to be the favorite center of the local youth, and also, the true factor of health of this new generation that is there, full of civism and full of love for this great piece of land of Minas Gerais" (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 01/11/1936, p. 1).

The Center for Physical Culture had a square and a swimming pool, and was frequented by the ruling class upon payment of a tax5 and a fee called “joia” (registration fee to compete in competitions). In this space sports such as swimming, volleyball, soccer and skating were practiced, which had the purpose not only of recreation, but also of competition, which happened in municipal and state level. In a 1940 edition, the newspaper regrets that the place "did not meet the expectations of its founders", since its main audience, the elite young people from Uberaba, in their leisure time preferred to attend "night clubs, which degrade morale and damage health" (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 06/07/1940, p. 5).

If the editors of Lavoura e Comércio were wary of the habits of the local youth, what would the Vargas regime say, which instituted educational mobilization projects whose intent was to adjust the youth to the State's guidelines. In this context, the most successful mobilization project was the civic movement Brazilian Youth, created by Decree-Law no. 2072 of 1940 and aimed at children and young people between the ages of 7 and 18, which had the direct participation of the Minister of Education and Health, Gustavo Capanema. Two years earlier, an organizational project had been created that intended to militarily regiment youth in the mold of fascist militia organizations, led by Francisco Campos, then Minister of Justice. Due to political dissidences, mainly from segments of the Army, which saw in this organization a loss of autonomy from its own field of action, the project was not only changed from ministerial portfolio, but also modified in its essence - the exclusively military formation of the youth gave way to a formation based on the ennoblement of civic values, described in Decree-Law no. 2.072 of 1940.

The Brazilian Youth movement aimed to "enforce the duties to the homeland", and to pay "constant worship to the National Flag" (BRASIL, 1940). The decree-law also systematized the "obligation of civic, moral and physical education of children and youth", through the praise of dates and national symbols. With regard to civic education, in the same document, the social roles of children and young people were separated by gender, based on stigmatized views: the male sex was responsible for a more "militarized" formation, focused on the battlefield, through the development of "love for military duty, awareness of the soldier's responsibilities and elementary knowledge of military affairs"; the female sex was responsible for a more "caring" formation, focused on the home, from the "learning of matters that, like nursing, enable them to cooperate, when necessary, in national defense" (BRASIL, 1940). In the document, one can observe the intention to prepare the children and youth for battles against possible enemies of the regime.

The Brazilian Youth activities took place in commemoration of civic events, both inside and outside the schools. Usually, students and employees of the schools, such as teachers and principals, participated in the activities. In 1940 the Youth Parade was instituted and started to take place during the Homeland Week in several cities around the country. These parades were mainly composed of events with the playing of the national anthem, the raising of the flag and military-style marches. The activities in which the Brazilian Youth participated were reported by the press in a praising way, leading to the understanding that the whole society shared the same values, with no thoughts contrary to those conceptions. It is worth mentioning that the participation of students and school employees in these events was mandatory.

In an article from 1942, Lavoura e Comércio described the Youth Parade during the Homeland Week in Uberaba in a very positive way. According to the periodical, despite unfavorable weather conditions, the event occurred with "great brilliance. The Youth Parade had the participation of most of the city's educational establishments: "elementary schools, gymnasiums, and technical teaching establishments, each of them wearing their badges and uniforms. The students, along with teachers and principals, "marched" to Rui Barbosa Square, in front of City Hall, where "high civil and military authorities" were present. Then the flag was raised and the National Anthem played by the police battalion band. After this first part of the ceremony, the city's mayor, Whady José Nassif, "made a patriotic and eloquent exhortation to the youth of our land in this difficult time for Brazil, and when the great dates of the Homeland Week are being celebrated. After the mayor's pronouncement, described as a "vibrant prayer, which was warmly applauded", the students "marched through the main streets of the city" (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 09/05/1942, p. 3).

The previous excerpt allows us to understand that the actions adopted by the mayor of Uberaba, Whady José Nassif, were aligned with the policies of the Estado Novo. The fragment also meets the assumptions of Decree-Law no. 2.072 of 1940, with regard to the purpose of the Brazilian Youth movement, and especially the Youth Parade, to glorify civic dates and worship the homeland. The event mentioned in the newspaper highlights the mobilization project aimed at children and young people, through symbols and rituals that valued the New State. The body regulation, present in the marches and in the use of school uniforms, reveals the standardization that was desired from the students.

In the newspaper, the article about the Youth Parade was accompanied by an image, which can be seen in Picture 2.

Source: Codiub Lavoura e Comércio collection. Available: http://www.codiub.com.br/lavouraecomercio/pages/main.xhtml. Accessed: March 11th, 2021.

Picture 2: Varguista propaganda aimed at children and young people (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 09/05/1942).

The image portrayed in the newspaper was taken from "A Juventude no Estado Novo" (Youth in the New State), an educational material aimed at children and teenagers. Produced by the Department of Press and Propaganda (DIP), the material was used in Brazilian schools and contained excerpts of Vargas' official speeches.

Figure 2 refers to a moment of civic celebration. In the center of the image, we can see a student holding the Brazilian flag and in the lower left corner some students also holding the Brazilian flag, all of them in uniform. The fact that a male student is in the center of the image, possibly leading the female students, makes it possible to think about the representation of masculinity itself in leading the actions considered most important within society. One can also notice the smiling countenance of the student, who seems to approve and be in agreement with such practices. The image accompanies the following Varguista discourse:

Brazilians: as the head of the nation, I rejoice and feel the faith I have always had in the future of Brazil strengthened. The great national virtue at this historic moment must be a military virtue - discipline: circumstances impose on our conduct the attribute of strong peoples - tenacity. The nation, disciplined and tenacious, will achieve its high goals of progress, under the protection of the green and yellow flag, symbol of the unity and greatness of Brazil (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 09/05/1942, p. 3).

It is clear that the intent of the previous discourse is to call on children and young people to value patriotism and the country. The fragment dialogues with the existing guidelines in the decree-law that institutionalizes the Brazilian Youth movement, by emphasizing the relevance of developing military values for the progress of the nation (BRASIL, 1940). In this aspect, the elite youth appear as the main public for this, since they could be led to acquire certain types of behavior and thinking. This idealized conception of the young is also in agreement with the document Exposição de Motivos (BRASIL, 1942a), proposed by Capanema as a result of secondary education, in which the youth should be prepared for the management of the country, as seen above.

Final considerations

In line with the Nazifascist ideals of countries like Italy and Germany, the Estado Novo (1937-1945) was characterized by a centralizing, authoritarian, and nationalist policy (BONEMY, 1999; SCHWARCZ; STARLING, 2018), from the concentration of state power in all spheres of action, and especially in the educational sphere.

In Uberaba, one of the main cities of the Central Brazil region in the period, the state interference in the educational field could be observed through the articles published in the Lavoura e Comércio newspaper, which highlighted the propagation of the estadonovist ideology. Such propagation was in accordance with the Department of Press and Propaganda (DIP), whose objective was to control the existing means of communication in the country, in order to monopolize information in favor of the Vargas regime. The control was exercised through what the periodicals published, in terms of the government's official speeches, and in terms of what Lavoura e Comércio itself produced.

Thus, the publications of Lavoura e Comércio, analyzed in this text, showed that the periodical was aligned to the Estado Novo educational policy, with respect to values, guidelines and practices based on the feeling of national unity, love for the homeland, and the cult of physical exercises - both in school and outside of it. It is important to stress that not only the main newspaper in circulation in the city, but also the mayor of Uberaba, Whady José Nassif, followed the assumptions imposed by the Estado Novo.

Specifically, the study of the periodical's publications showed the concern of the Vargas government regarding a specific part of the population: children and young people of school age, especially the elite, who should be molded to meet the government's expectations, aiming at the "progress" of the nation. This was especially noticeable with the Organic Law of Secondary Education, with the valorization of the subject of Physical Education, from a strictly military bias, and with the Brazilian Youth and National Crusade of Education movements. In the city of Uberaba, the editions of Lavoura e Comércio revealed that the mobilization plans and projects aimed at the children, and youth public were more evident in specific periods, for example, on symbolic dates from the point of view of patriotism (implantation of the Estado Novo, Homeland Week) and on Christmas dates (Vargas' birthday).

The analysis of the news contained in Lavoura e Comércio also allowed us to verify that no record was found of any manifestation contrary to the estadonovista directives, or even any report on people who might disagree with the civic solemnities that were taking place at the time. In fact, the articles analyzed showed that the population of Uberaba appeared to passively accept the imposed guidelines, which is not surprising, given the repression of any demonstration that questioned the prevailing order and the government.

REFERENCES

ARAÚJO, José Carlos Souza Araujo; INÁCIO FILHO, Geraldo. Inventário e interpretação sobre a produção histórico-educacional na região do Triângulo Mineiro e Alto Paranaíba. In: GATTI JÚNIOR, Décio; INÁCIO FILHO, Geraldo (orgs.). História da educação em perspectiva: ensino, pesquisa, produção e novas investigações. Campinas: Autores Associados; Uberlândia: Edufu, 2005. [ Links ]

BOMENY, Helena Maria. Três decretos e um ministério: a propósito da educação no Estado Novo. In: PANOLFI, Dulce (org.). Repensando o Estado Novo. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 1999. [ Links ]

CAPELATO, Maria Helena. Propaganda política e controle dos meios de comunicação. In: PANOLFI, Dulce (org.). Repensando o Estado Novo. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 1999. [ Links ]

FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes de. O processo de escolarização em Minas Gerais: questões teórico-metodológicas e perspectivas de pesquisa. In: VEIGA, Cynthia Greive e FONSECA, Thais Nívea de Lima e (orgs). História e historiografia da educação no Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2003. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Jorge. A democracia no Brasil (1945-1964). São Paulo: Atual, 2006. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Jorge; DELGADO, Lucília de Almeida Neves. O tempo do nacional-estatismo do início da década de 1930 ao apogeu do Estado Novo. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasiliense, 2010. [ Links ]

HORTA, José Silvério. O hino, o sermão e a ordem do dia. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2012. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA (IBGE). Estatísticas do século XX. Rio de Janeiro, 2006. Disponível em: https://seculoxx.ibge.gov.br/images/seculoxx/seculoxx.pdf. Acesso em: 23 fev. 21. [ Links ]

MATE, Cecília Hanna. Tempos modernos na escola: os anos 30 e a racionalização da educação brasileira. Bauru: EDUSC; Brasília: INEP, 2002. [ Links ]

MENDONÇA, José. História de Uberaba. Uberaba: Academia de letras do Triângulo Mineiro. Bolsa de publicações do Município de Uberaba, 1974. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Anelise Martinelli Borges. Leituras, valores e comportamentos: práticas escolares no Colégio Tiradentes da Polícia Militar de Uberaba. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Universidade Estadual Paulista, Marília, 2017. 143p. [ Links ]

PAIVA, Vanilda. Educação popular e educação de adultos. 6. ed. São Paulo: Loyola, 2003. [ Links ]

PANOLFI, Dulce. Apresentação. In: PANOLFI, Dulce (org.). Repensando o Estado Novo. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 1999. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Dermeval. História das ideias pedagógicas no Brasil. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2007. [ Links ]

SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz; STARLING, Heloisa Murgel. Brasil: uma autobiografia. 2. ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2018. [ Links ]

SCHWARTZMAN, Simon. Gustavo Capanema e a educação brasileira: uma interpretação Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, 66 (153), 165-72, maio/ago 1985. Disponível em: http://www.schwartzman.org.br/simon/capanema_interpretacao.htm. Acesso em: 11 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

VELLOSO, Monica Pimenta. Os intelectuais e a política do Estado Novo. In FERREIRA, Jorge; DELGADO, Lucília de Almeida Neves. O tempo do nacional-estatismo do início da década de 1930 ao apogeu do Estado Novo. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasiliense, 2010. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Decreto-Lei nº 2.072, de 8 de março de 1940. Dispõe sobre a obrigatoriedade da educação cívica, moral e física da infância e da juventude, fixa as suas bases, e para ministrá-la organiza uma instituição nacional denominada Juventude Brasileira. Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/declei/1940-1949/decreto-lei-2072-8-marco-1940-412103-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL a. Exposição de Motivos. Decreto-Lei n. 4.244, de 9 de abril de 1942. Lei Orgânica do Ensino Secundário. Disponível em: http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/declei/1940-1949/decreto-lei-4244-9-abril-1942-414155-133712-pe.html. Acesso em: 09. Mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL b. Decreto-Lei n. 4. 642, de 2 de setembro de 1942. Dispõe sobre as bases da organização da instrução pré-militar. Disponível em: http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/declei/1940-1949/decreto-lei-4642-2-setembro-1942-414557-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html. Acesso em: 13 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 11/01/1936. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 08/08/1936. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 21/08/1936. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 21/05/1937. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 13/06/1940. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 06/07/1940. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 20/04/1941. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 30/08/1941. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 12/11/1941. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 19/04/1943. [ Links ]

LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, Uberaba, 07/07/1945. [ Links ]

2On the government of Getúlio Vargas, see: FERREIA, Jorge; DELGADO, Lucilia de Almeida das Neves. O tempo do nacional-estatismo: do início da decada de 1930 ao apogeu do Estado Novo. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2010 and FERREIRA, Jorge. A democracia no Brasil (1945-1964). São Paulo: Atual, 2006.

3The Lavoura e Comércio newspaper remained with uninterrupted activities until 2003, when it ended its publications.

4The gymnasium entrance exam lasted until 1971, when compulsory primary school education was introduced.

5It is inferred that a large part of the visitors of the place was composed of the wealthier social stratum due to the amount to be paid for the monthly fees. Converted to today's currency, a male member would have to pay R$ 125.00 a month, while "children and girls" would pay the equivalent to R$ 62.50 (LAVOURA E COMÉRCIO, 07/07/1945, p. 5). Such values are not small, taking into consideration that the Brazilian minimum wage in the first half of the 1940s was approximately R$ 1,200.00 (information taken from: https://seculoxx.ibge.gov.br/images/seculoxx/seculoxx.pdf. Accessed on: 23 Feb. 21).

Received: September 05, 2022; Accepted: December 20, 2022

texto en

texto en