Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-190

Artigos

Domestic child labor and teaching and learning to read in Brazil in late 19th and early 20th centuries1

1Universidade Federal de Pelotas (Brasil). eteperes@gmail.com

This article analyzes newspaper ads collected in the digital magazine and newspaper archive of the Brazilian National Library in the period between the last decades of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century in which children are requested or offered to work, especially to domestic labor, and in which the possibility to learn how to read or to “finish learning how to read” is referred to. In a context of several changes in Brazil, the demands of reading, writing and counting grew expressively. The main argument developed is that work in the aforementioned period, notably domestic labor, was a space in which a portion of the Brazilian childhood learned how to read and write. The necessity for working and learning a craft, urban growth, lack of schools, the life conditions of children born after 1871 and the post-abolition period are among the reasons explaining this reality.

Keywords: Domestic labor; Child labor; Infancy; Reading; Writing

Este artigo analisa anúncios de jornais, coletados na Hemeroteca Digital da Biblioteca Nacional, do período entre as últimas décadas do século XIX e a primeira do século XX, em que crianças são solicitadas ou oferecidas ao trabalho, em especial ao trabalho doméstico, e nos quais é referido a possibilidade de que pudessem aprender a ler ou “terminar de aprender a ler”. Em um contexto de diversas mudanças no Brasil, as demandas do ler, escrever e contar cresceram expressivamente. O principal argumento desenvolvido é que, no período mencionado, o trabalho, notadamente o doméstico, foi um espaço no qual uma parcela da infância brasileira aprendeu a ler e a escrever. A necessidade de trabalho e de aprendizado de um ofício, o crescimento urbano, a insuficiência de escolas, as condições de vida das crianças nascidas livres a partir de 1871 e o pós-abolição estão entre as razões que explicam essa realidade.

Palavras-chaves: Trabalho doméstico; Trabalho infantil; Infância; Leitura; Escrita

Este artículo analiza anuncios de periódicos, colectados desde la Hemeroteca Digital de la Biblioteca Nacional, del periodo entre las últimas décadas del siglo XIX y la primera del siglo XX, en que niños son requeridos u ofrecidos al trabajo, especialmente al trabajo doméstico, y en los que se refiere a la posibilidad de que aprendieran a leer o a “terminar de aprender a leer”. En un contexto de diversos cambios en Brasil, las demandas por leer, escribir y contar crecieron expresivamente. El principal argumento propuesto para ello es que, en dicho periodo, el trabajo, visiblemente el doméstico, fue un espacio en el cual una parte de la infancia brasileña aprendió a leer y a escribir. La necesidad de trabajo y de aprendizaje de un oficio, el crecimiento urbano, la insuficiencia de escuelas, las condiciones de vida de los niños nacidos libres a partir de 1871 y el periodo post abolición son algunas de las razones que explican esta realidad.

Palabras clave: Trabajo doméstico; Trabajo infantil; Infancia; Lectura; Escritura

Introduction

Brazil has a long history of exploiting child labor. Impoverished children have always been put to work. For whom? For their owners, when they were enslaved during colonial and empire times, for the ‘capitalists’ in the early days of industry, as was the case of orphaned, abandoned, or helpless children from the 19th Century; for large land-owners as farmhands; at agricultural or artesian production facilities; at family homes; and finally on the streets, to maintain themselves and their own families. (RIZZINI, 2000, p. 376).

History of Education has a long-standing tradition of producing studies on childhood2. There is still much to study on that matter, however. This paper seeks to contribute to the History of childhood, particularly to the History of child labor, in its relationship to the History of early teaching and learning of reading and writing skills at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th Century.

We have set as our main goal to analyze the relationship between offer and demand of children for domestic services and their learning of reading skills. The main argument we seek to propose is that during the period mentioned above, there was growing concern for learning to read and, sometimes, to write. Additionally, many boys, but also some girls, were requested or offered for domestic services under the condition that they learn to read or “finish learning to read”.

Some of the factors that explain the practice of employing underaged children as apprentices, particularly in private homes, were insufficient schools, the need for labor and for acquiring skills relevant to specific trades, urban growth, increase in services offered in cities, living conditions, and the destiny of children, especially those who were born free under the 1871 Law of Free Birth, but who were themselves the sons and daughters of enslaved people, and the post-abolition context. As Soares (2017, p. 25) concludes, “during the post-abolition period, requests for child labor significantly increased compared to the enslavement era”.

Data from this research, which was collected from newspapers available at the digital magazine and newspaper archive of the Brazilian National Library, corroborate that reality. We came across requests, news stories, advertisements published in different newspapers and magazines, especially in Rio de Janeiro, which was then the capital of Brazil, offering or demanding children for work at homes under the conditions mentioned above. This study encompasses the second half of the 19th and the early years of the 20th Century, up to the late 1920s.

“Pet children”: child labor and learning how to read

After Law n. 2.040 of 28 September 1871, the so-called Law of Free Birth, was enacted, sons and daughters of enslaved women were born free and remained, by force of the legislation, under the guardianship of their parents’ owners, who should raise them and care for them, until the age of eight. According to the Law, when the child of the enslaved woman reached that age, the mother’s owner could choose to receive 600$000 as compensation from the state or employ the child’s services until they were 21 (BRAZIL, 1871). Alongside other measures and events, this Law started to change labor relationships in Brazil, culminating with the abolishment of slavery - at least legally - in the country, in 1888.

As we can see from the legislation, starting in 1871, even if they were born free, boys and girls remained under the care of their mother’s owners until they reached the age of eight. After that, salve-owners either handed them to the state or continued to employ them. According to Soares (2017, p. 50), the legislation from 1871 established that “underage children would be handed to the government, who would appoint tutors for them. This shows a clear interest in pleasing slave-owners, who had an effective and lawful way of employing child labor in a relationship of servitude”. According to Perussatto (2021, p. 65), even though the institute of tutorship already existed before 1871, this new Law completely redefined it, creating a widely used legal concept that was, in fact, “an instrument for slave-owners to exploit children born free”.

The figure of a tutor, thus, existed prior to 1871, dating back to the “judges of orphans” when Brazil was still a colony. Azevedo (2007, p. 2) points out that they were instituted by “Book I of the Ordinances issued by King Philip, a code of laws compiled in 1603 that is considered the backbone of Portuguese law”. The author, however, highlights the following:

By the first decades of the 19th Century, we note that those judges were mostly concerned with rich children. Beginning in the first decades of the 19th Century, however, the scope of those judges’ actions gradually changed. Even though they continue to care for matters involving rich children, several laws were enacted with the goal of providing legal bases for those judges to mediate labor matters (AZEVEDO, 2007, p.3).

The author mentions that a set of legislation from the 19th Century - including one that abolished the need of financial guarantees for those interested in tutoring a minor - made the number of requests for tutorship increase considerably. As we can see, then, tutorship goes beyond - both prior and after - the Law of Free Birth. In the context of the Law however, it acquired a specific meaning, as it accompanied the transition from enslaved labor to free labor: “From the middle of the 19th Century to the first decades of the 20th Century, tutorship changed, from being used in accordance with the principle of protecting the child to becoming a broad mechanism to employ child labor” (AZEVEDO, 2007, p. 4).

As it was an instrument used to exploit child labor, tutorship, even after slavery was abolished, continued to be a common practice that grew during the early 20th Century. This meant that even free, many underaged children lived under a servitude regime - not legally, but de facto. This means they worked since they were quite young, did not receive salaries, and faced poor conditions of living. As we have highlighted above, Soares (2017, p. 39) explains that there was a significant increase in the number of requests for tutorship of underage children, especially in 1888. According to her, “this ‘business’ was made viable due to the possibility of establishing an employment relationship” (SOARES, 2017, p. 39).

The “pedagogy of the master” in labor was an inheritance left by the slave system and found other ways to come to be after it was legally abolished (GÓES; FLORENTINO, 2000). According to Rizzini (2000, p. 377), “the experience of slavery had shown that children and young laborers were a more docile workforce, cheaper, and the most adaptable to work”.

Stories of children who lived and worked in poor conditions, who were subject to violence, who did not attend school, who were not taught how to read and to write were abundant in newspapers of the time.

Diário do Maranhão, for example, published in 1890 an Affidavit issued by Police Officer Francisco de Carvalho Serra and signed by the Chief of Police, Dr. Julio de Mello Filho, as well as by Raimundo Nonnato dos Santos, who represented two women - a mother and a grandmother - who denounced a case of abuse of tutorship. Mr. Santos signed the Affidavit because the women presenting the complaint did not know how to read and to write.

They sought the local authorities to denounce to the Chief of Police a case of “continued enslavement”, as they called it, of four underage boys and girls - who were their children and grandchildren - at the Lençois Farm, in Pedreiras, Maranhão. Furthermore, they sought the State Police Department to request the tutorship of Major Joaquim Pinto Saldanha over the four children to be revoked.

Juliana Rosa Martins, the grandmother, and Febronia Rosa Martins, the mother of Theophilo, Izabel, Julia, and Filomena, declared to the Chief of Police and to all those present that the children suffered abuse from their tutor, were not properly fed, did not receive adequate clothing or shoes, did not attend school to learn how to read and to write nor any workshop to learn a trade. According to them, this amounted to continued enslavement, as the four children worked day and night in domestic and farm services, as if they were slaves. They argued that Major Saldanha sought to be named tutor of the children only to keep them in a regime of forced labor and used his position and rank to refuse to waive his tutorship rights. They urged, thus, for the police to intervene. This is only one of the examples of tutors abusing children who were impoverished, mostly black, the children or grandchildren of people who had been enslaved.

Tutored children and so-called “fostered children” became commonplace in Brazil and led to a nefarious idea that they were “treated as members of the family”, when in fact they were exploited mainly in day-to-day home life, in commerce, and in the provision of small services. Regarding that matter, let us examine the following advertisement:

One girl aged 10 to 12 wanted for small services at a family home. She will be considered a member of the family, no preference for race, but preferably orphaned. At Rua de São Claudio n. 6, Rio Comprido (Jornal do Commercio, 1893, p. 8).

This is the “family equality” myth, as identified by Jean Baptiste Debret when he traveled through Brazil (GÓES; FLORENTINO, 2000). It is also an inheritance from the times of the slavery system, when captive children, the sons and daughters of enslaved people, lived - sometimes side by side - with the children of slave-owners. The beliefs originated in that context did not account for the fact that young, enslaved people were, since an early age, exploited, humiliated, and used in benefit of the whims of free children.

“In the past, all families had their pet children. They were either a mixed-race girl, a black girl, or a young boy” (Pedro II, 1889, p. 2). This is how a long story entitled “Outr’Ora” [Back in the Day] begins. It was written by França Junior and published in 1889 in the newspaper Jornal Pedro II, Órgão Conservador de Fortaleza. One year after slavery was abolished, the story adopts a sorrowful tone, lamenting it was not possible to keep “pet children” anymore.

The story then states that the “young boy” was usually the son of an enslaved woman who had breast-fed “her young master with all care and received honors equivalent to enfranchisement”. Furthermore, “those children had the same privileges and benefits” as the other children in the house: clothing, food, education, and “even bore the name of the family”. When they were babies, the story goes on to say, “they were publicly paraded, especially in front of visitors”. When they grew older, they were “tasked with the most important missions”, i.e., serving the owners of the house - working. “Sadly”, according to the author, those “young boys gradually disappeared with time” (Pedro II, 1889, p. 2).

If “pet children” from “back in the day” disappeared, for the despair of slave-owning families, those families found other ways of exploiting children to their benefit. Advertisements as the one below were frequent in newspapers and magazines:

[Attention: Whomever has a child and wishes to hand them to be raised, please visit Rua de S. Martinho, n. 8C].

Figure 1 Advertisement (Gazeta de Notícias, 1893, p.4)

It is hard to pinpoint what were the true reasons behind advertisements such as this, requesting “a child […] to be raised”. Judging by the data collected, most of them were wanted for domestic services, i.e., to work at the household while “being considered a member of the family”, which meant paying them a salary was out of the question.

Furthermore, children could render services in commercial facilities or for other trades. Generally, services were exchanged for food, clothing, and/or accommodation. Let us examine the following advertisement, in which work would be exchanged for home, food, and learning a trade, with no salary paid. We cannot help but notice the racial matter as well: “White, Brazilian boy wanted for services at a dental office. We will teach him the trade and provide food and shelter, with no compensation. Please visit Rua do Cattete n. 219” (Jornal do Brasil, 1901, p. 6).

As Soares (2017, pp.102-103) points out, “apprentices were one of the most exploited categories in the world of child labor. Their labor was employed under a logic of learning a trade, development, and progress as future urban citizens”. We add that this idea also included the need for learning to read, write, and, sometimes, count (learning how to add, subtract, and perform other operations).

There are several advertisements similar to that, and “most of those children at whom the advertisements were aimed came from poor families and needed to work to complement their income” (SOARES, 2017, p. 56). They also might have wanted to learn a trade, guarantee they had shelter and food, and learn how to read and to write.

All advertisements below request boys and girls for household services and mention the possibility of learning to read and to write, which is the focus of this study:

A young boy around 15 to 16 years of age is wanted for small services, with enough time to learn how to read and to write. We prefer those from the outskirts of town. More information at the store at Rua de D. Manuel n. 30 (Gazeta de Notícias, 1892, p.5).

A young girl aged 10 to 15 is wanted at a family home to take care of children. We provide clothing, shoes, and some pay. She can learn how to read, to write, and needlework. She will be treated well. At Rua do Santos Rodrigues, n. 133 (Jornal do Commercio, 1895, p.13).

Young girl wanted for small household and family services. She can learn how to read, write, and count. At the two-story house at Rua do Lavradio, n. 115 (Jornal do Commercio, 1895, p.9).

Whoever has an 8- to 12-year-old boy and wishes to hand him to a family to learn how to read, write, and count, in exchange for him providing some services, please visit Rua Silva Guimarães, n. 28, Fábrica das Chitas district, as he will be treated as a member of the family (Jornal do Commercio, 1898, p.11).

Boy aged 10 to 12 wanted for courier services. We prefer a boy of color, provide food, clothing, and teach him how to read. At Rua da Paz, n. 31, Rio Comprido district (Jornal do Brasil, 1903, p.5).

As we can apprehend from the advertisements, children were wanted for “small services”, to be employed as couriers, to keep company to other children. They could either be paid or not, but lack of payment was commonplace at the time. Working in exchange for shelter, food, clothing, and learning how to read and to write was, therefore, the reality for part of the Brazilian children, especially after slavery was abolished and during the first couple of decades of the 20th Century.

As we highlighted, all advertisements above share references to young workers being able to learn how to read, to write and, sometimes, to count (make simple operations) in a context of domestic work. Families who requested children were certainly aware of the relevance reading skills were acquiring at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th Century. Therefore, they used them as a bargaining chip: labor or “small services”, a generic term that lacks precision, in exchange for learning how to read.

This gives weight to the argument already raised by other authors, such as Faria Filho (1999) and Demartini (2001), that we cannot understand teaching and learning how to read and to write at that time by adopting a perspective focused exclusively on schools.

In her study of biographies portraying children from the turn of the Century, Demartini (2001, p. 122) concluded that many children became literate “outside of a school system, in relationships that encompassed different groups”. Furthermore, the researcher identified children as protagonists at the time: In some cases, they taught one another. Reading and writing were also seen positively among families and children themselves, even in places where there was no school. Later, we will see how those who were responsible for children also offered them to render services in exchange of them learning how to read.

For the advertisements studied here, it is interesting to note that learning to read and to write was a requirement and was one of the things offered for working children. This means there was someone at those families’ households that was able to teach: were women, daughters and sons, or even another employee responsible for teaching? Were they individual classes or young laborers learned alongside the other children at the house? Which supplies were available for teaching (books, notebooks, pencils, blackboard, etc.)? At what times did that teaching take place, and for how long? Unfortunately, it is impossible to reconstitute practices and their materials. We can consider, however, that someone who was able to teach and some supplies were available to allow for learning in a household space.

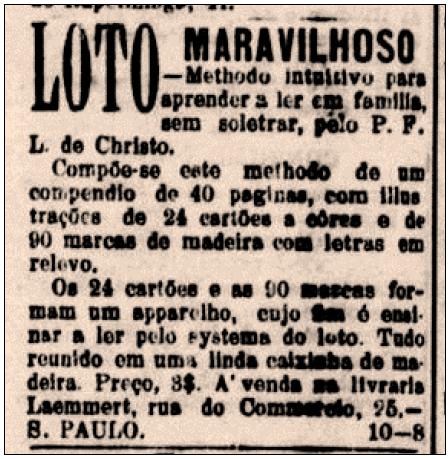

We cannot assume that families who requested boys and girls for domestic services invested significant amounts in teaching them how to read and to write, nor to pinpoint how that teaching took place, as we indicated above. What we can ponder, however, is that there was a set of supplies available for circulation at the time. Advertisements for them are frequent in newspapers we researched. Let us examine below an example of an advertisement for a lotto game. It comprised a compendium, illustrated cards, and wooden pieces with embossed letters. They allowed families to learn how to read with no spelling, via an intuitive method:

[LOTTO - Wonderful, intuitive method for the family to learn how to read with no spelling, by P.F.L de Christo. This method comprises a 40-page compendium, 24 illustrated cards in color, and 90 wooden pieces with embossed letters. Those 24 cards and 90 pieces form a set whose goal is to teach via the lotto method. Everything is stored in a beautiful wooden box. Price: $3. For sale at Laemmert bookstore, at Rua do Commercio, 25 - SÃO PAULO.]

Figure 2 Advertisement (O Commercio de São Paulo, 1895, p.3)

While compendiums, cards with the ABCs, lotto, illustrated alphabets were sold and acquired by families, there was also material made specifically for teaching how to read distributed for free by stores and industries. This reveals an effort by the community to increase literacy levels, especially among the poorest. An advertisement for the drugstore Pharmacia e Drogaria Ramos & Irmãos, located in Vitória, state of Espírito Santo, is a prime example of that:

[Standard Letter - Drugstore Pharmacia e Drogaria Ramos & Irmãos printed for free distribution a standard letter that teaches how to read. It also includes a full repository of drugs they have for sale. Through their publicity, Mr. Ramos and his brother provide a valuable service, aimed at educating the poor. We thank them for the copy they sent us.]

Figure 3 Advertisement (Cachoeirano, 1908, p.1)

With those few examples we seek to raise questions and hypotheses on teaching and learning to read in domestic settings. During the late 19th and the early 20th Centuries, there was a latent concern for teaching methods and significant production and sale of supplies to support teaching and learning those skills in public and private schools, making up a rich and diverse scholarly material culture. What we want to highlight, however, is that at the same time, there was also an instructional material culture, which we have identified in another study (PERES, 2021), made up of supplies aimed at teaching reading and writing in spaces outside schools, as the examples mentioned above show.

The instructional material culture is comprised, thus, of supplies that were socially available and not aimed specifically at schools: Magazines, almanacs, prayer books, games, pamphlets, signs, letters, cards, printed matter and manuscripts that circulated freely and were used in religious, commercial, industrial, political, and other settings. People who taught took ownership of that material and used it to teach reading and writing at home. We do recognize, however, that material produced for schools was also used in domestic settings, forming an intricate and complex net of relationships between daily lives and scholarly culture. Next, we highlight that advertisements offering children for domestic services under the condition they learned or finished learning how to read were also frequent, as we can see in the examples below:

Young one for rent for small services, wants to learn how to read, does not request payment. At Rua Theophilo Ottoni, 183, two-story house (Jornal do Brazil, 1915, p.5).

A 10-year-old boy is offered for chores and to finish learning how to read and write. We will pay whoever takes care of him. At Rua Marquez de Pombal 98, pub (Jornal do Brazil, 1911, p.2).

We offer a young Portuguese boy for a teacher who will take him to school to learn how to read or for a family who has a young boy of their own to make him company. We provide for food and clothing. He is 10. At Rua Francisco Eugênio 328, house n. 7, speak to the father (Jornal do Brazil, 1913, p.17).

We notice that in the second and third advertisements, those offering the children also offer to pay for their care: We will pay whoever takes care of him; We provide for food and clothing. There is explicit mention made to payment in one case, and, in the other, a guarantee that food and clothing would be provided for by those “offering” the young Portuguese boy. There were different ways, thus, that children were offered for domestic work. This means there were different relationships arising due to characteristics both of the original family and of the families requesting those children.

In her study, Soares (2017) analyzed the significant increase in requests for working children after slavery ended. Also using advertisements looking for child labor as a source for her research, she analyzed material published between 1888, when slavery was legally abolished, to 1927, when the Brazilian Underage Children Act was enacted, creating measures to assist and protect children. The researcher sought to “understand the context in which freedom, poverty, and the labor market interacted in the early years of the Republic” (SOARES, 2017, p. 19). She concluded that:

Lack of resources to educate and feed children and fear of seeing them lose their way were also motivations behind fathers and mothers wanting to offer their children to a tutor or boss, removing them from the family. In that context, poverty led young boys and girls to join the workforce (SOARES, 2017, p.16).

This is how one can explain the number of advertisements - probably by the guardians of the children - with the expressions for rent, offered etc. What we point out, however, are references to the requirements and demands that children would learn how to read and to write or “finish” learning, revealing that they did not attend school regularly and that there was a need for mastering those skills.

Another news story, shown below, also reveals the relevance of learning how to read in the second half of the 19th Century. Even though it is from a period before the Law of Free Birth and before slavery was abolished, and unrelated to domestic labor, this piece reinforces our argument of how fundamental learning to read and to write was for boys and girls during that period, at a time of new labor relationships, urban growth, new services offered, while rhetoric appealed to progress, modernity, development, and the fight against crime and vagrancy.

In 1866, the newspaper Jornal do Recife published the story of the suicide of Seraphim Rodrigues Lopes, a trader from the town of Caxias, state of Maranhão. According to the article, he was a honorable and reputable businessman who left the following note before taking his own life:

I hereby declare I am of sane mind. If I kill myself is only not to drag on this life that is so heavy on me.

I further declare that this house’s trading activities belong to my brother José Rodrigues Lopes, and that I have nothing.

I ask my brother that, from the good of his heart, he takes care of my son: have him finish to learn how to read, then have someone teach him a trade that he likes best.

I have nothing else to add.

Goodbye to those who left, see you on judgment day.

Caxias, 19 April 1866

Seraphim Rodrigues Lopes (Jornal do Recife, 1866, p.4).

By analyzing the note, we can observe its author’s two main concerns: to declare that his business was left to his brother, José Rodrigues Lopes, and to guarantee his son was taken care of. Lopes left two requests regarding the latter: that the boy finished learning how to read and that he learned a trade. This content allows us to identify, among others, how relevant it was to learn how to read for certain social groups in the 19th Century. One of the last wishes of Seraphim Lopes, who probably knew how to read and to write himself due to his trade as a businessman, was for his son to be taken care of after his death. That meant learning how to read, possibly doing it well, and learning a trade that would ensure his professional future.

Demands for working in commerce and in urban services in general grew significantly during the early 20th Century, and requests for child labor in those areas were common in advertisements as well. Once again, however, we highlight - as it is the purpose of this study - the requirement that those boys knew how to read, in some cases to read and to write, and in other cases, to read, to write, and to count (make simple operations):

Boy needed at this typography workshop to learn the trade. He must know how to read well, to write, and maintain good behavior (O Vigilante, 1900, p.2).

Boy 15 years old or younger, clean, who knows how to read and to write needed for work at a homeopathy drugstore. Must have good references. At Rua da Quitanda, n.23 (Jornal do Commercio, 1902, p.7).

Boy 12 to 15 who knows how to read needed to deliver parcels door to door. At Travessa das Bellas Arte, n.7 (Jornal do Brasil, 1905, p.7).

Pharmacy Pedreira needs a well-behaved boy who knows how to read, write, and count and who wants to work there (Jornal de Caxias, 1904, p.5).

Outside of domestic labor3, boys had more opportunities compared to girls when it came to public spaces: they were more often offered services on the streets - as couriers or making deliveries - as well as in commerce, in the press, and in healthcare. As we have mentioned, however, they did not always receive compensation.

As for activities performed by girls, Soares (2017, p.96) concludes in her study that those were “mostly restricted to domestic environments”. They worked as dry nurses, took care of children, washed, pressed, and starched clothes, cooked, cleaned the house, kept childless couples, elderly ladies, and children company, and performed other activities at home.

Both boys and girls, however, were subject to arduous work from early ages. We cannot tell whether in fact they managed to learn how to read and to write while working. Nor can we tell whether they had other opportunities to improve their lives while learning. There is no question, however, that these advertisements reveal a positive image of reading and writing, as well as a growing need in a society that was starting to value written culture and in which learning also occurred outside of school settings.

Final remarks

Children under tutorship, children handed and taken in “to be taken care of”, children employed with no pay or for modest pay and with no protection from the law. They worked in public and private spaces in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th Century, following a long-standing tradition in Brazil of exploiting child labor, as Rizzini (2000) points out in the excerpt used as an epigraph to this paper. As Soares (2017, p. 56) stated, “within the universe of working childhood, there were children with no direct support from their parents, orphans, those who roamed the streets, ‘abandoned’, immigrants, former slaves, and impoverished white people”.

Child labor was thus a feature of Brazilian society at the time. The end of slavery, social, political, cultural, and commercial changes, as well as new forms of work relations explain that reality. As it was not possible for families to maintain “pet children” - either those who were enslaved or those who were born free - the alternative was to tutor them, “take care of them as if they were family”, or employ them under the conditions revealed above. It was those children - or at least some of them - who learned to read and to write in work environments, specially at households.

The main conclusion that can be drawn from this study, therefore, seems evident: during the period in question, impoverished boys and girls learned to read at the environments where they did domestic work, which indicates a direct relationship between working and learning reading - and sometimes writing and counting - skills.

We can however still draw further conclusions: First, this study reinforces the hypothesis of the relevance of teaching and learning to read in private settings at the time. This indicates that those practices - alongside schools, which were the main bodies of the state with the goal of teaching those skills - contributed to part of the population being literate. Second, far from trying to praise those experiences of teaching to read, to write, and to count in the context of child labor, our goal here was to explain and understand this reality. This led us to once again conclude that the History of education in Brazil was built on inequality and injustice: just like nowadays, some children could attend schools, and for them childhood was a time to learn and to play; others, however, had to work and/or remain under the guardianship of families that were not their own, certainly due to need for survival and to learn a trade.

Unfortunately, in Brazil, learning to read, write, and count at school and being able to even attend it have historically been the privilege of only part of the population.

REFERENCES

AZEVEDO, Gislane Campos. Os juízes de órfãos e a institucionalização do trabalho infantil no século XIX. História. Revista on line do Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo. Ano 3, N. 27, Novembro, 2007. Disponível em http://www.historica.arquivoestado.sp.gov.br. Acesso 02 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

BRAZIL. LEI Nº 2.040, DE 28 DE SETEMBRO DE 1871. Disponível em https://blogdabn.wordpress.com/2016/09/28/fbn-i-historia-28-de-setembro-de-1871-promulgada-a-lei-do-ventre-livre/. Acesso 01 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

CACHOEIRANO, Anno XXXI, N. 19, Cachoeiro do Itapemirim (ES), 7 de maio de 1908, p. 1. [ Links ]

DEMARTINI, Zeila de Brito Fabri. Crianças como agentes do processo de alfabetização no final do século XIX e início do XX. In: MONARCHA, Carlos (org.). Educação da infância brasileira (1875-1983). Campinas/SP: Autores Associados, 2001. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO DO MARANHÃO, Anno XXI, n. 5182, Maranhão, Sexta feira, 26 de dezembro de 1890. [ Links ]

FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes. Representações de escola e do analfabetismo no século XIX. In: BATISTA, Antônio Augusto G.; GALVÃO, Ana Maria de Oliveira. Leitura: práticas, impressos, letramentos. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 1999. [ Links ]

FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes; ARAÚJO, Vania Carvalho de (org.) História da Educação e da Assistência à Infância no Brasil. Vitória: Edufes, 2016. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Marcos Cezar (org). História Social da Infância no Brasil. 3 ed. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2001. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Marcos Cezar; KUHLMANN, JR., Moysés (org.). Os intelectuais na história da infância. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2002. [ Links ]

GAZETA DE NOTICIAS. Anno XIX, N. 110, Rio de Janeiro, Sexta feira, 21 de abril de 1893, p. 4. [ Links ]

GAZETA DE NOTICIAS. Anno XVIII, N. 190, Rio de Janeiro, Sabbado, 9 de julho de 1892, p. 5. [ Links ]

GÓES, José Roberto; FLORENTINO, Manolo. Crianças escravas, Crianças dos escravos. In: Del PRIORE, Mary (org.) História das crianças no Brasil. 2. Ed. São Paulo: Editora Contexto, 2000. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO BRAZIL. Anno XI, N. 272, Rio de Janeiro, Domingo, 29 de setembro de 1901, p. 6. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO BRAZIL, Anno XIII, N. 157, Rio de Janeiro, Sabbado, 6 de junho de 1903, p. 5. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO BRAZIL, Anno XV, N. 252, Rio de Janeiro, Sabbado, 9 de setembro de 1905, p. 7. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO BRAZIL. Anno XXI, N. 248, Rio de Janeiro, Terça feira, 5 de setembro de 1911, p. 2. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO BRAZIL. Anno XXIII, N. 16, Rio de Janeiro, Quinta feira, 16 de janeiro de 1913, p. 17. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO BRAZIL. Anno XXV, N. 145. Rio de Janeiro, Terça feira, 25 de maio de 1915, p. 5. [ Links ]

JORNAL DE CAXIAS (MA). Anno IX, N. 419, Caxias, 30 de Janeiro de 1904, p. 5. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO COMMERCIO. Anno 71, N. 348, Rio de Janeiro, Sabbado, 16 de dezembro de 1893, p. 8. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO COMMERCIO. Anno 78, N. 263, Rio de Janeiro, Sabbado, 21 de setembro de 1895, p. 9. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO COMMERCIO. Anno [?], N. 97, Rio de Janeiro, Domingo, 7 de abril de 1895, p. 13. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO COMMERCIO. Anno 78, N. 300. Rio de Janeiro, Sexta feira, 28 de outubro de 1898, p. 11. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO COMMERCIO. Anno 82, N. 3, Rio de Janeiro, Sexta feira, 3 de janeiro de 1902, p. 7. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO RECIFE. Anno VIII, N. 105, Recife, Segunda feira, 7 de maio de 1866, p. 4. [ Links ]

KUHLMANN, JR., Moysés. Infância e educação infantil: uma abordagem histórica. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 1998. [ Links ]

MONARCHA, Carlos (org.). Educação da infância brasileira (1875-1983). Campinas/SP: Autores Associados, 2001. [ Links ]

O COMMERCIO DE SÃO PAULO, Anno III, N. 713, Quarta feira, 24 de julho de 1895, p. 3. [ Links ]

O VIGILANTE. Anno XV, N. 198, Pilar, Alagoas, Domingo 18 de novembro de 1900, p. 2. [ Links ]

PEDRO II. Orgão Conservador. Anno 49, N. 66, Fortaleza, Domingo, 16 de junho de 1889. [ Links ]

PERES, Eliane. Cultura material escolar e cultura material instrucional no ensino e aprendizado escolar e doméstico da leitura e da escrita (Memórias de Aprendizes, Século XX). In: CORDEIRO, Andréa Bezerra et. al. (Org.). A Teia das Coisas: cultura material escolar e pesquisa em rede. 1ed.Curitiba/PR: NEPIE/UFPR, 2021, v. 1, p. 145-167. https://nepie.ufpr.br/e-book-a-teia-das-coisas-cultura-material-escolar-e-pesquisa-em-rede/ [ Links ]

PERUSSATTO, Melina K. O futuro da nação: instrução, educação e racialização da infância (Porto Alegre, RS, c. 1871-1910). Revista Brasileira de História & Ciências Sociais, 13(25), pp. 60-90, 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14295/rbhcs.v13i25.11995. [ Links ]

SOARES, Aline Mendes. Precisa-se de um pequeno: O trabalho infantil no pós-abolição no Rio de Janeiro 1888-1927. Dissertação (Mestrado em História Social) - Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, UNIRIO, Centro de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Social Rio de Janeiro - PPGH, 2017. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Gizele de. Educar na infância: perspectivas histórico-sociais. São Paulo: Editora Contexto, 2010. [ Links ]

RIZZINI, Irma. Pequenos trabalhadores do Brasil. In: Del PRIORE, Mary (org.) História das crianças no Brasil. 2. Ed. São Paulo: Contexto, 2000. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Cynthia Greive; FARIA, Luciano Mendes. Infância no sótão. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 1999. [ Links ]

1Title and abstract translated by Luca Igansi. Paper translated by Leonardo A. Peres, professional translator with a Post-Graduate Diploma in Translation Studies from the Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS), Brazil. E-mail: leonardo@lptrad.com.

2See, for example, the landmark studies by Kuhlmann Jr. (1998); Veiga; Faria (1999); Monarcha (2001); Freitas (2001); Freitas; Kuhlmann Jr. (2002); Souza (2010); Faria Filho; Araújo (2016).

3According to the study by Soares (2017, p. 94), who analyzed 1,223 advertisements from Jornal do Commercio, RJ, published between 1888 and 1926, “domestic work requested the most labor (58%, or 706 of all advertisements), followed by commerce (31%, or 382, requests), factories (1%, or 13 requests), while other advertisements (10%, or 122 requests) did not specify the area of work”.

Received: September 26, 2022; Accepted: December 13, 2022

texto en

texto en