Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensino em Re-Vista

versão On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.28 Uberlândia 2021 Epub 29-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v28a2021-4

DOSSIÊ 1 - FORMAÇÃO DO PROFESSOR PARA O ATENDIMENTO EM AMBIENTE HOSPITALAR

The history of Education at the Litle Prince Hospital and the continuing training/education of teachers1

2Doctor in Education at UFPR, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. E-mail: anavenancio2704@gmail.com.

3Doctorate student in Literature and Linguistics at UFPR, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. E-mail: itamarapeters@gmail.com.

4Master in Education at PUC - PR, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. E-mail: marianasw@uol.com.br.

This study describes the historical aspects of the education of hospitalized children and adolescents, discussing how this right has been organized and the challenges of teacher training faced in order for the legal exercise to take place and be effective. This is a descriptive qualitative research, which lists by sampling the practices developed and how the right to education of hospitalized children are guaranteed by a philanthropic institution in Curitiba. The research described highlights the aspects of the training of teachers and educators of the Pequeno Príncipe Hospital based on the studies developed during the elaboration of the political pedagogical project of the Education and Culture Sector of the aforementioned hospital and its implementation.

KEYWORDS: Right to Hospital Education; Teacher training/education; Challenges for Brazil

O presente estudo descreve os aspectos históricos da educação de crianças e adolescentes hospitalizados, debatendo o modo como esse direito vem sendo organizado e os desafios de formação docente enfrentados para que o exercício legal se concretize e se efetive. Trata-se de uma pesquisa de caráter qualitativo descritivo, que elenca por amostragem as práticas desenvolvidas e o modo como o direito à educação da criança hospitalizada são garantidos por uma instituição filantrópica de Curitiba. A pesquisa descrita evidencia os aspectos da formação de docentes e educadores do Hospital Pequeno Príncipe tomando como base os estudos desenvolvidos durante a elaboração do projeto político pedagógico do Setor de Educação e Cultura do referido hospital e sua implementação.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Direito à Educação Hospitalar; Formação docente; Desafios para o Brasil

Este estudio describe los aspectos históricos de la educación de los niños y adolescentes hospitalizados, discutiendo cómo se ha organizado este derecho y los desafíos de la formación del profesorado a los que se enfrenta para que el ejercicio legal se lleve a cabo y sea efemo. Se trata de una investigación cualitativa descriptiva, que enumera mediante el muestreo de las prácticas desarrolladas y cómo el derecho a la educación de los niños hospitalizados está garantizado por una institución filantrópica en Curitiba. La investigación descrita destaca los aspectos de la formación de profesores y educadores del Hospital Litlle Prince a partir de los estudios desarrollados durante la elaboración del proyecto pedagógico político del Sector de Educación y Cultura del mencionado hospital y su implementación.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Derecho a la educación hospitalaria; Formación del profesorado; Desafíos para Brasil

Introduction

The present text seeks to present how the organization of education and culture happens in Pequeno Príncipe Hospital, in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil through the bias of the formation of the team of educators. The hospital brings the realization of educational projects considering the access to the education process as an indisputable right of children and young people in health treatment. The educational proposal of the Education and Culture Department of the Hospital has been organized throughout the existence of the department.

It is understood that the pedagogical project of the department is defined as an “open work”, that is, the pedagogical process is created and recreated according to the educational demands that are presented to it, however, this process takes place considering certain educational principles that aim at referencing the pedagogical practice developed in the institution.

It is also argued that this articulation of Education and Culture also occurs between health and education, in a multidisciplinary approach shared between teams, which allows subjects to experience the rights to health and education in an integrated way, as determined by the legislation. Thus, the planning and operationalization of individualized actions, possible through the construction of a work plan based on the contextual and learning needs of singular subjects5 allows not only the continuity of studies, but the coexistence and social participation necessary for human development and learning and the experience of a real citizenship and not only in the ideal plan.

Research methodology

This is a qualitative research that involves a case study (focused on the context of action) of an ethnographic nature (it aims to describe a particular mode of organization, bringing the practice of the subjects in their locus of action), that is, it investigates how the teachers education takes place in their and for their context of action, in this case teaching in hospital schooling programs.

A century-old history

The history of the Pequeno Príncipe Hospital completed in 2019, a century of existence.

It is a story of motivation and concern for the well-being of others, the hospital was born from the careful and attentive gaze of a group of women from Curitiba who were touched by the facts of the First World War and by movements to create the Red Cross, the international network of health care for the disadvantaged, mobilized to create a health care for the low-income population in the city of Curitiba, especially the care for children.

Such mobilization gained strength and success culminating in the first children's outpatient clinic with a fixed address, opened in May 1919, in which children were treated free of charge and also received their medicines.

After the inauguration of the outpatient clinic, still in 1919, the Institute of Child Hygiene and Childcare was launched. It was opened on October 26 of the same year and, already in its initial phase, became a reference for mothers both in the care of babies and in the teaching of childhood care, being called The Children's Post. It is from this proposal that the Pequeno Príncipe Hospital was born, combining names, stories of childhood care and research.

Currently the Pequeno Príncipe Complex is a center of reference and health care, teaching and research that assists children and young people from the region and other states, bringing together The Pequeno Príncipe Hospital, The Pequeno Príncipe Colleges and the Pelé Pequeno Príncipe Research Institute, with the sponsor of the Hospital Association for Child Protection Dr. Raul Carneiro.

Throughout history, the Hospital has become an educational space. Since its foundation, there has been a concern with the act of educating and humanizing that is also revealed in the scope of the training of professionals to assist children and the education of care for children. According to Carreira (2016, p.24) “for the hospital staff, access to information and education expands the possibilities for people to take better care of their own health”, as well as the health of children and adolescents. "Educating for health became one of the transversal axes of the institution”.

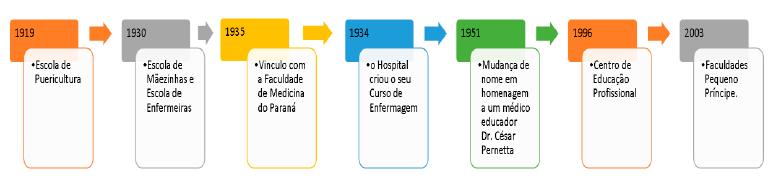

From the beginning, the institution turns its gaze to the care and humanized attention to its public: children, adolescents and mothers, training professionals in various areas as shown in the Figure 1 below.

The educational actions of the hospital expand and the teaching process goes beyond the medical professions. In this perspective, there is the understanding that the relationship of care involves the triad teaching, research and assistance, so that the institution would be able to offer full and qualified assistance to those who need it.

In 1967, with the new mobilization of the Curitiba society, the construction of a new building started in the back of the César Pernetta Children's Hospital, on a donated land. The new unit, inaugurated in 1971, was named Pequeno Príncipe Hospital, and was specially designed for the public who it would assist. It was incorporated into the oldest building by a tunnel that contemplates the timeline of the hospital and thus the two units began to compose a single hospital.

In this care process, the institution invested in a pioneering way in other services such as psychology, humanization, social assistance, participating family, volunteering and education and culture, creating departments responsible for each of these services. "The Pequeno Príncipe is an educational hospital because it conceives and exercises the practice of democratization of knowledge in every possible way for the population." (CARREIRA, 2016, p. 33).

Based on this premise, the hospital and its professionals also care about the educational process of children who are removed from schooling due to health treatment. With this concern and the actions aimed at its public, the hospital opens doors to a new proposal: education in the hospital space.

From the educational hospital to the right to education and culture

The actions of an educator Hospital led to the creation of the “Juvenile Project for School-based Hospitalization” in 1987, developed by the then social worker Margarida M. T. F. Muggiati. The project begins with the objective of minimizing the problems arising from the long hospitalization of children and adolescents: the stress caused by hospitalization, depression, family separation and interruption of school trajectory, among others. Initially the project had only professionals from the hospital, but the great demand for assistance required the search for a support network.

The support network was formed from agreements established with the State Education Secretariats (1988) and Municipality (1990), the program “School-Based Hospitalization” was the milestone of the creation of the Education and Culture Department, which was officially established in 2002, with the purpose of expanding and strengthening the school follow-up of hospitalized children and adolescents.

Since the beginning of its activities, the Education and Culture Department has been concerned with formal education and with the expansion of linguistic, historical, cultural, artistic repertoires, among others; both of children and adolescents, as well as their families and hospital employees.

The extension of services constitutes a large network of interconnected actions. In it are the activities of reading and storytelling, the workshops of art, music, theater, photography, among others, and games, which complement the educational process developed by teachers.

In order to further formalize its actions, the department begins to create a system of registration of the activities developed. Each child is accompanied with an individual record in which all the school and cultural activities that they participated during the period of hospitalization are described; at the end of the visits, teachers and educators prepare a descriptive opinion and organize a portfolio of activities that are sent to the child's home school. This organization aims to fully guarantee access to education and the return of this process to the school where the Child / Adolescent is enrolled, so that the continuity of schooling, even in defiance of the illness, is guaranteed and possible.

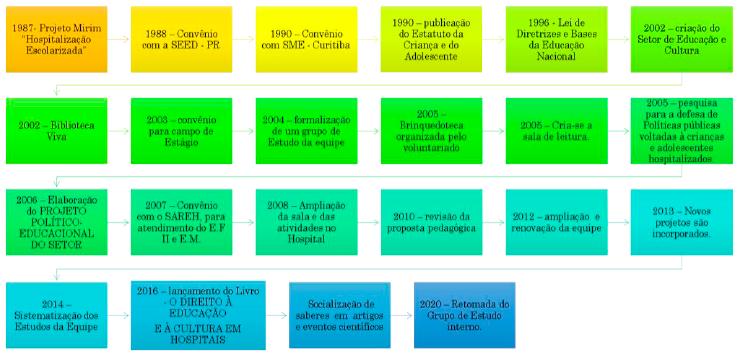

The investment of the Hospital and of the professionals in favor of education in the hospital space can be seen more clearly in the Figure 2 below. It shows the timeline of the actions developed in order to guarantee the right to education of children and adolescents who attend the Hospital to treat their health, but who also have the possibility of having access to education and culture in a systematic, planned and thought-out way for them.

From the beginning of the Juvenile Project until the institutionalization of the Education and Culture Department at the Pequeno Príncipe Hospital, there has been a great investment by the teams that have been forming this department, as well as by the institution itself in training its professionals and in the search for excellence in educational proposals.

Theoretical principles

The hospital is constituted as an environment in which social significance is linked to the representation of health care only. However, there are schools in hospitals and, increasingly, there are teachers who work with students in inpatient or outpatient treatment seeking to guarantee their combined rights: health and education.

Although hospital education as a modality is still little discussed academically, which is still under theoretical and practical construction on Brazilian soil, there are laws that guarantee the right of students to have the continuity of studies, regardless of health conditions. Namely (Federal Constitution /88, art.205; Decree Law n. 1044/69, art. 1º, which provides for exceptional treatment for students with conditions; Law n. 8.069/90; resolution n. 41/95; Law n. 9.394/96; resolution N. 02/01 - CNE/CEB; document entitled hospital class and home pedagogical care: strategies and orientations, edited by MEC, in 2002. National Policy of Special Education in The Inclusive Education Perspective, 2008.

Amendment of Law No. 9,394 / 96 by the text of Law No. 13,716, of September 24, 2018). These legal guidelines point to the necessary attention that those who are deprived, by chronic or prolonged health treatment deserve, to have guaranteed basic rights, especially the right to education, understanding education as a possibility of social and political participation that incites the emancipation of subjects.

It can be seen, therefore, that in addition to the various issues that complexify the formal school environment, in the different teaching environments there are identical challenges and others that are configured from the uniqueness of these new environments that are structured, in general, through the militancy of those who act in them.

We seek to know the context of life, current situation and collect data on schooling that allow us to understand the trajectory of the one who will be assisted by us. At that moment, we welcome the family, invite them to be our partners, and the student to immerse him/herself in schooling in an active yet differentiated way, we gather their interests, curiosities and their previous knowledge as material that will model the work plan to be developed, even if we follow the guidelines of the school team regarding the curriculum to be experienced.

We maintain close contact with the schools of origin, we welcome the teams, often it is us, teachers of the hospital, who present the student to the teacher and his class, because often the student has never been to school or is absent for a long time. In this way, we create or tighten bonds between teachers, students and learning, demonstrating the pleasure of learning through the construction of dialogical relationships where the meaning of teaching and learning weave networks of affection, hope and love that culminate in deepening knowledge and redefining practices in use, expanding repertoires (both of students and professionals who work with them).

In this path, we act in an interprofessional way, establishing partnership with teachers, pedagogues, school management, but also and necessarily, with the health teams that assist the child/adolescent. This is because the routine in the hospital is absolutely different from the classroom. We depend on an articulation between professionals that culminates in the promotion of the quality of life of those who are assisted.

All the work is based on the singularization of the lesson plans and provides for curricular flexibility. The action involves the entire health care team and families to establish the dialogue and partnership in favor of the assisted student, as well as the team of the school of origin and other professionals who assist the student in the hospital and at home.

By proposing a close relationship between health, education and culture, we are willing to bring knowledge closer, resuming a necessary relationship in the integral care of the subjects. It articulates an exchange of knowledge that emerges from the context and the recognition that the two areas can contribute to each other with knowledge that adds value to the relationship between health and education, considering, in this path, the human, political and didactic plans of this relationship.

We remind that education has the role of seeking different languages, resources and ways to achieve goals that aim at changes in social behavior. Thus, combining health knowledge in search of common goals becomes a task that contemplates the two areas in the mission of consolidating a posture aimed at early intervention and the development of better results in this action of identification, stimulation and monitoring of health processes. The justification for this articulation lies in the fact that "education and health constitute an epistemic field of significant relevance for the quality of human and social life."(RANGEL, 2009, p. 59).

We defend the premise that articulating education and health can constitute a measure to enhance related practices in order to improve quality of life of those who need integrated care, under the understanding that:

Pedagogy is a theoretical field that brings together the foundations and subsidies of the sciences applied to education. Education, therefore, is the subject and object of pedagogical studies, observing, in particular, that its essence, its substance is found in the values of human and social formation. [...] It is in this perspective of values that health is understood as an educational theme, human and social formation, in the interest that it can also be understood and claimed as a fundamental right of citizen life and an essential part of human dignity. (RANGEL, 2009, p. 60/61).

The human dimension of the interrelationship between health and education refers to the purpose of the epistemic process of production of knowledge and relationships instituted in this movement, which is understood within an essentially humanizing proposal “(...) both in the perspective of its social application, in the interest of quality of life, as in the perspective of humanizing values that will guide the practice of these professionals.” (RANGEL, 2009, p. 61). The Human plan should therefore be present in the training of health and education professionals, favoring the development of sensitivity, attention and reception, factors that have the potential to sustain a dialogical posture that generates and encourages attitudes of collaboration, encouragement and inclusion, providing a better organization of environments and a practice based on ethical principles of welcoming and loving-kindness.

As for the political plan of education and health practices, which is situated in the commitment, “that is of governments and educators, with the knowledge to be guaranteed in the education process, understanding it as the right of students and essence of the training courses, as it is in the social and political understanding of health” (RANGEL, 2009, p.62). The expansion of the concept of quality of life, associated with this commitment, is one of the pillars of contemporary research and is based on the State's duty to “guarantee the right the conditions and resources necessary for this quality” (RANGEL, 2009, p.62).

The didactic dimension refers to the act of teaching and learning, a practice that is effective in the relationship between teachers and students, as well as in the relationship between the health professional and the people they assist.

Didactics has, as its object, the teaching-learning process. This process, which incorporates objectives, means, contents and context, in which knowledge is understood, elaborated, applied, also requires motivation and willingness of the subjects who practice it. (RANGEL, 2009, p. 62).

The classes are, therefore, moments of encounter between subjects who deepen their knowledge through a posture of research and analysis of reality, in a dialogical and respectful way. Our theoretical principles are based on a list of progressive educators who take education as an open, dialogical and collectively constructed process. We consider that teacher and students are subjects of the act of knowledge and should actively participate in it. As a result, we work with the dialogical method based essentially on the studies of Paulo Freire.

Freire, in his various works, expresses his understanding of popular education linked to actions with the oppressed, proposes a methodology that facilitates the process of emancipation of the individual and society, in the hope of overcoming oppression, exploitation and social inequality. In this perspective, Freire (2000, p.43) situates that one of the primary tasks of radical liberating (popular) critical education “is to work on the legitimacy of the ethical-political dream of overcoming unjust reality”. Thus, the popular education advocated by the author is one that pursues the dream of building a just, equitable society. And it is from these considerations that the way of teaching has been discussed.

[...] reinventing oneself always with a new understanding of power, going through a new understanding of production, a society in which we enjoy living, dreaming, dating, loving and cherishing. This education has to be courageous, curious, curiosity arousing and maintaining. (FREIRE, 2001, p. 101).

Thinking about education, and especially about education in a differentiated environment, in which there are numerous factors combined that give it uniqueness and its own structure and functioning. It requires an educational conception that goes beyond the domains and walls of the school, especially the school of traditional bases, still present and active even in the face of socio-historical cultural changes that signal the urgency of new educational models. Through this perspective of education, this text proposes to think of an educational practice that promotes the subjects’ protagonism, teaching them to have a voice, making them partners in the construction of knowledge and in the continuous movement of its reinvention.

For Paulo Freire, education is based on dialogue and interaction between teacher and student, and it is in this perspective that we understand and act in Hospital Education. Thus, the educator has a prominent role as a mediator between the world of knowledge and the students themselves, it is up to the educator to be an agent of social transformation, articulating theory and practice, enabling a reflection of the action taken and, consequently, the reflection of the developments of this action. Thus, the "dialogical relationship” proposed by Freire (1996) is established in the hospital as a new form of relationship that includes the child and the adolescent in health treatment in a “systematized knowledge/cultural context” establishing a process of access, experience and development of critical consciousness during their hospitalization experience.

Dialogue is a determining issue for the meeting of the voices of the educator and the student, that is, a condition of teaching, learning and constituting identities. In hospital education, we take dialogue as the center of all educational actions and leave it for the development of teaching proposals based on the specific needs of each subject involved in this proposal. We understand that it is necessary to recognize and respect the different timings of the subjects, seeking to establish relationships necessary for the construction of knowledge and values. This is achieved through interaction related to the self-another present in mediation qualitatively committed to a critical, liberating learning.

The act of learning is directly related to the social function that the subject exercises and to individual experiences, closely related to the mode of thought that the subject possesses, therefore, learning is not “repeating the lesson” memorized mechanically, it goes much further. (FREIRE, 1994, p. 33).

Thinking about this, Freire also stated that the historical-social aspects and the individual differences of the students should be considered, since he is a historical being and is built in relations with other men and with the world, starting from the assumption that each subject has a unique configuration of vivified experiences. Since education only happens through social relations established with the community lived, we believe in hospital education emancipated from school, which has its own identity and that has a theoretical-methodological framework that gives it the basis and credibility of action. It is clear that this does not mean denying the school, but rather recognizing new spaces for the systematization of knowledge and that these spaces can represent a differentiated way of treating knowledge and advancing both in terms of methodologies and didactics as well as theories about educational processes. In parallel, the current need to reinvent the formal school spaces is emphasized, considering the goal of promoting an education for all and by all, the need to contemplate the technological advances and the understanding of the new relations with the information built in a world where the technological apparatus gains prominence.

It is also understood that, in addition to dialogue and reflection, the work of the teacher/educator is to be committed to the diversification of methodologies and to a planning based on the personalization of the teaching provided. Therefore, the planning and execution of classes should be thought in the sense of being able to create them through a contract with the subjects of the dialogue, without imposing it as a way of doing, as an instrument of power. In other words, education cannot be a hierarchical relationship, but a horizontal, dialogical and loving relationship of encounter between subjects.

We understand and agree with the role of the teacher as a social agent as defined by Imbernón (2011, p.46) “teachers can be true social agents, capable of planning and managing teaching-learning, as well as intervening in the complex systems that constitute the social and professional structure”. It is in this sense that the way of acting and teaching is reflected, seeking the bases of teaching and learning to then define work methodology in a differentiated environment in which the teacher action plan is mobile, destabilized and susceptible to multiple changes.

We understand, according to Freire (1994), that education cannot be seen as anything other than human doing. Doing that occurs in time and space, between people, in their dynamic relationship with each other. And it is from this idea that hospital education is based and seeks what to do. However, one “what to do” that goes beyond the obvious and the traditional schooling, taking as its basis the theoretical assumptions of Freire:

There can be no pedagogical theory, which implies in ends and means of educational action, that is exempt from a concept of human and the world. In this sense, there is no neutral education. If, for some, the human is a being of adaptation to the world (taking the world not only in a natural sense, but in a structural, historical-cultural sense), his educational action, his methods, his goals, will suit this conception. If, for others, the human is a being of transformation of the world, his educational doing follows another path. If we see it as a" thing", our educational action is processed in mechanistic terms, which results in an ever greater domestication of the human being. If we see him as a person, what we do will be more and more liberating. (FREIRE, 1997, p. 07).

In hospital education, Paulo Freire's proposal is concrete insofar as the entire educational process contemplates dialogue and the baggage of knowledge that the student already presents to us. Because the dynamics of learning occurs through mutual interactions, in which students and teachers establish social and affective relationships, as the “class” is the environment in which these relationships solidify and move towards the significant development of cognitive skills and socio-affective aspects.

Aspects of the group formation

Observing the trajectory of research and development of the Education and Culture Department, we analyze the educational process of its professionals, collecting information from twelve (12) educators who work in different spheres in the department in order to compare whether the theoretical and historical affirmations match the teaching reality in this process of collective in-service education and of an Educational Hospital.

The questionnaire presented to the group brought five (5) closed questions with answers of ( ) yes or () no and four (4) open questions that allowed to discuss and argue about the proposed question. The answers given to the questions asked, organize what was mentioned earlier and confirm the role of the Hospital as an educational space in every way.

The results bring us an overview of the pre-service and in-service education of these professionals, confirming the premise of building knowledge and the search for personal and professional improvement.

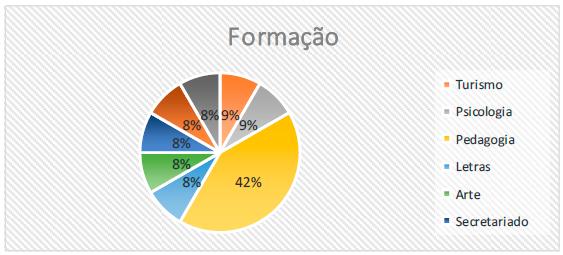

The initial education of the group takes place in different areas of knowledge, evidencing the multiplicity of knowledge that combine in the same space with a common goal, as the following graph points out:

Turism; Psychology; Pedagogy; Literature and Linguistics; Fine Arts; Secretary.

Source: the authors, 2020.

Chart 1: Pre-service teacher education

Analyzing the aspects of pre-service education, we observe a relationship between the bachelor's degree, teaching, and pedagogy. The largest percentage of professionals are from different areas, generating a heterogeneous group that covers different fields of knowledge. In this case, the field of pedagogy prevails quantitatively, but the number of professionals from other areas working in the department is significant and is computed together.

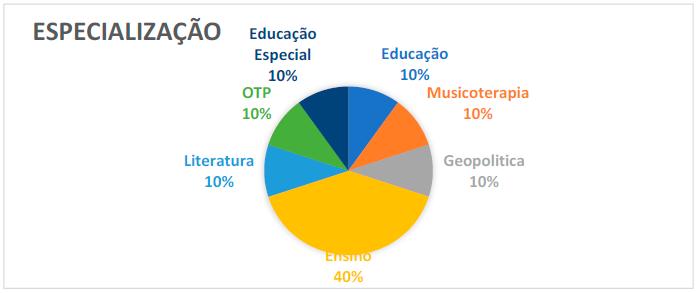

In another analysis, we can observe the vertical growth of the group of educators involved in the hospital educational field. When asked about specialization the percentage is quite significant.

The graph shows that 69% of educators working in the Education and Culture Department have a specialization, indicating that the group is very concerned about their qualification.

In addition, the training takes place in different areas, following the trend detected in the pre-service education.

SPECIALIZATION: Special Education 10%, Education 10%, Music therapy 10%, Geopolitics 10%, Teaching 40%, Literature 10%, Organization of Pedagogical Work (OTP) 10%.

Source: the authors, 2020.

Chart 3: Areas of specialization

Graph 3, of the area of specialization, shows how this training takes place, there are varied trainings, 10% in different areas, and 40% that focus on the teaching process, pointing to the purposes of the teaching action in the specific context dealt with in this study. That is, the focus on the ways of teaching and the reflections on this process are marked in the percentage of specialization of teachers.

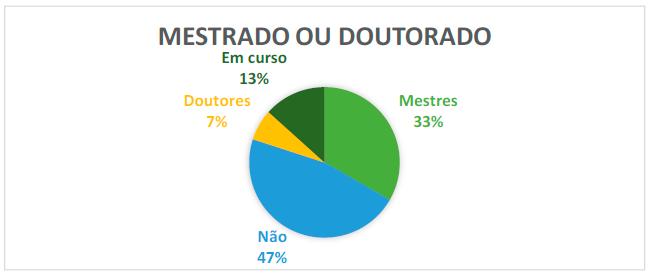

When dealing with the vertical levels of education, the following chart is composed:

Master's or Doctorate Ongoing 13%, Masters 33%, No 47%, Doctors 7%.

Source: the authors, 2020.

Chart 4: Graduate School

Graph 4 shows a percentage of professionals who are not in this level of education, but also brings a high percentage of professionals who have invested in research and turn their focus also to the academic environment. Of the percentage of Masters, 33% presents yet another interesting fact: the dissertations and research are directly related to the field of action, that is, they are researches that aim to bring theoretical support to the area of activity of the teachers involved.

Thus, the space of action is identified as a locus of action and research or research and teaching action.

The second stage of the questionnaire was based on open questions that originated the charts that will be presented in the sequence of the text. There were four questions that allowed the educators to explain the reasons for their choice and their training processes.

In the first table, we bring the counterpoint between pre-service and in-service education, showing that the group sought their training/education when entering the Education and Culture Department thinking about their action in this space.

Table 1: aspects of teachers’ education

| Educator | Before entering the Hospital | After entering the Hospital |

|---|---|---|

| Educator 1 | Specialization | Courses offered by the secretariats, extension course in Educational Assistance in Hospital and Home Environment (UFMS) |

| Educator 2 | Specialist in Children's literature | Bachelor of Performing Arts. Nonviolent communication and reading mediation |

| Educator 3 | Psychology | Master's in Education |

| Educator 4 | Pedagogy | Hospital Pedagogy Specialization and Seminars |

| Educator 5 | Secretarial | Theater |

| Educator 6 | Teacher | Hospital Education Seminars, Extension Course in Educational Care in Hospital and Home Environment (UFMS), BNCC and special and inclusive education. |

| Educator 7 | Specialization | Participated in training related to function. |

| Educator 8 | Degree | Specialization in music therapy, Training of facilitators. |

| Educator 9 | Bachelor’s Degree | Specialization in History and Teaching of the Arts, courses from the secretariats in Hospital Education. |

| Educator 10 | Degree and Specialization | Masters in Letters, participation in a research group and courses related to the area. |

| Educator 11 | Master in Education and training courses in specific areas | PhD in Education, Participation in research groups, UFMS extension course, participation in seminars and congresses. |

| Educator 12 | UFMG - Educational Service in Hospital and Home Environment |

Source: the authors, 2020.

Table 1 emphasizes that all educators invested in their training/education after entering the Education and Culture Department. In addition, the variation of paths taken indicates a plurality of choices that converge to educational assistance in a hospital environment.

When asked about what motivated the search for training/education, the answers always involve the context of action as a motivating element for the search for knowledge. Table 2 presents the synthesis of the answers given to this question, emphasizing the reason for the search for training/education.

Table 2: search for training/education

| Educator | What motivated the search for training/education? |

|---|---|

| Educator 1 | Studying, sharing particularities and identity of the hospital and home environment. Expand the possibilities of educational practices of students in health care. |

| Educator 2 | The possibility of expanding and improving knowledge in the specific areas in which I work in the hospital. |

| Educator 3 | I want to better understand aspects of my work. |

| Educator 4 | Expansion of knowledge for the management of pedagogical practice in the hospital environment. |

| Educator 5 | Love for the profession and professional and personal growth. |

| Educator 6 | Improvement to better serve students and interpersonal relationships. |

| Educator 7 | For the opportunity to become a little more instrumental, have access to new content, increase the repertoire for care with families. |

| Educator 8 | The work done in humanization and the work done with music. |

| Educator 9 | Improvement in professional performance both in the attendance of hospital education and in the performance in the classroom in the discipline of sociology. |

| Educator 10 | What drives the training process is the passion for the context of action (hospital), the search for new teaching alternatives and the belief that teacher training combined with good practices is capable of generating a more efficient and effective education that is aimed at for the subject's needs. |

| Educator 11 | The improvement and diversification of teaching practice in view of the diversity in the hospital, diversity that concerns not only organic issues, but also ethnic, cultural, linguistic, among others. |

| Educator 12 | To guarantee the right to education for hospitalized children and young people. Bring the information to families that, even when hospitalized, children and young people have the guaranteed right to study. |

Source: the authors, 2020.

Analyzing Table 2, we observed a recurrence of mention to the space of action, all subjects emphasize the work with children and the adolescents in health treatment as a motivating element for their search for training/education and knowledge in the area of activity. There is a very strong bond between the subjects and the study and their workplace.

The search for training/education is highlighted as a factor linked to the quality of the work carried out with hospitalized children and adolescents, their families and even hospital employees. There is on the part of all members a concern about the quality of the information and the educational service that is developed. The performance in the hospital space appears in the discourse of educators as a motivating element for the search for knowledge and technical and personal improvement. According to Imbernón (2011, P. 36) “the professionalization of the teacher is directly linked to the exercise of their professional practice" corroborating what the report of the educators indicates. Still on this aspect, the author points out that:

If practice is a constant process of study, reflection, discussion, experimentation, jointly and dialectically with the group of teachers, it will approach the emancipatory, critical tendency, assuming a certain degree of power that reverberates in the domain of themselves. (IMBERNÓN, 2011, p. 36).

Another important point that carries the significance of the context and the baggage of knowledge and bond of the subjects with the area of activity refers to the aspects that they consider important in training/education for acting in this context. Table 3 clearly demonstrates what educators point out as relevant aspects of in-service teacher education.

Table 3: in-service teacher education

| Educator | What aspects do you think are important in the education of the Educator - Teacher at the hospital? |

|---|---|

| Educator 1 | One of the important aspects in teacher education is being open to discover ways to improve their performance with students. Questioning their practice, sharing actions, participating in the work of the multidisciplinary team in order to further contribute to the well-being and development of students and patients. |

| Educator 2 | Regarding my work, I consider all practices / courses that I am in contact important, because in addition to my work as an educator, I also develop a job as a facilitator in the Humanization Center, so the courses related to art and communication enable me to new tools both to work in the workshops with the children (cultural part) and with the collaborators. Art and culture are undoubtedly a very important aspect of my work. |

| Educator 3 | That the professional has knowledge of various topics from different areas of knowledge and not just the specialty that he is graduated in. That he is curious and knows how to share his curiosity. |

| Educator 4 | Commitment to care: the student's right to education; with the continuity of the studies and with the preparation of the student's classes. |

| Educator 5 | The opportunity for the child / adolescent to continue their studies and to be able to see the study with a different perspective (also helping to choose their future professions). |

| Educator 6 | Updating and expanding the professional vision to better meet the specific needs of students. |

| Educator 7 | I believe that the educator in the hospital context, in addition to being aware of some technical procedures, needs a different attitude to relate to the student / patient. You need to be able to deal with the specifics of each student, have ability, flexibility and sensitivity to deal with each special situation that you face. |

| Educator 8 | Bond with the patient, didactic creativity, family involvement, being analogical versus technological, artistic expression. |

| Educator 9 | I think it is important to provide moments where the teacher can explore (in a group) the dialogical possibilities with a wide variety of materials that the Education and Culture Sector provides. |

| Educator 10 | Critical awareness, creativity, proactivity, ethical sense of responsibility, ability to adjust to the needs of the context and the subjects he serves, competence to adapt and adapt the actions to the space of performance. |

| Educator 11 | Personalized training in view of the needs of the students served, hence the need for courses in the various areas of knowledge, but with the exploration of resources and materials suitable for use in the hospital with its hygiene requirement. More than themes, we seek training that allows the curricular, evaluative and methodological flexibility that hospital practice requires in order to fulfill the objective of guaranteeing the continuity of studies. In this way, I emphasize the importance of training with the working group itself, since each hospital makes up a single locus of work. |

| Educator 12 | The importance of training teachers to work in the hospital environment, must be focused on humanization. Professionals who know how to look at their students as a whole and who work in an interdisciplinary way, I emphasize what Silva (2003) presents about the role of the educator in the hospital, where the professional must provide different significant learning situations that contribute to the rehabilitation process and, consequently, to the development of patients. Professionals who work with this audience need to provide moments of learning to learn. |

Source: the authors, 2020.

By pointing out the relevant aspects in the training/education of the hospital educator, the subjects indicate a set of factors listed in Table 3; bring to light what each individual values in this collective construct of teacher education. It is a pedagogical knowledge that has been reconstructed and resignified in the context of performance and training/education among peers. The teachers point out important and interesting aspects that involve categories of human, technical, theoretical development that extrapolate the academic knowledge of the initial areas of education.

When we carefully analyze the answers to the question: “What aspects do you think are important in the education of the Educator - Teacher at the hospital?”, we identify, in the list of answers, aspects that complete and add to points of convergence with what states Imbernón (2011) on the lines of permanent training/education:

Practical-theoretical reflection on the practice itself through analysis; understanding, interpretation and intervention on reality. The ability of the teacher to generate pedagogical knowledge through educational practice.

The exchange of experience between peers to make it possible to update in all fields of educational intervention and increase communication between teachers.

The union of training/education with a work project.

Training as a critical stimulus to professional practices such as hierarchy, sexism, proletarization, individualism, low prestige, etc., and social practices such as exclusion, intolerance, etc.

The professional development of the educational institution through joint work to transform this practice. (IMBERNÓN, 2011, p. 50).

In this way, there is evidence of a reflexive process of the subjects about their practice when we analyze the set of concepts and educational trajectories of a relatively significant group that aims to bring to their work context a different practice, which is reflected and re-signified by proposing a way of teaching and learning that is different from the traditional molds.

Final considerations

The text presented here brought the discussion of aspects of teacher education in a multiple and complex context, schooling in hospitals. We emphasize that such education is plural and turns to the needs that the work in hospitals requires. We understand that, far beyond specialists in hospital education, what we present is a human, humanistic, humanizing and dialogical training/education that focuses its lens on the specifics of the development of the capacity to deal with and welcome the other, in this case, children, adolescents, family members, health team and educators with whom we interact daily.

We point out that, in this context much more than in any other, the educational process reveals and develops knowledge and skills, requiring a dynamic, creative teacher, open to multiple possibilities of action and interaction. Thus, we understand that the teachers must be the inspirers of learning. To this end, they must research, innovate and increase its pedagogical knowledge, expand their general culture and seek to know and develop new teaching techniques. In the hospital, diversity concerns aspects that distinguish care and require a sensitive gaze from teachers to welcome differences without giving space to discrimination of any order, we also emphasize that each ward configures its own culture, and requires joint action between the field of education and health, interconnected fields in the hospital environment, where the “school” reinvents itself. Teacher training/education is a design that allows curricular, methodological and evaluative flexibility to meet unique needs and guarantee the right to education, under the understanding that affectivity, respect and ethics permeate the entire educational act.

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Decreto Lei n.1044/69, art. 1º, que dispõe sobre tratamento excepcional para alunos portadores de afecções. Brasília, 1969. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição Federal. Brasília, Senado Federal, 1988. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Lei n. 9.394/96. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Brasília. 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990. Dispõe sobre o Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente e dá outras providências. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Conselho Nacional de Direitos da Criança e do Adolescente. Resolução N° 41, de 13 de outubro de 1995. DOU, Seção 1, de 17/10/1995. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Classe hospitalar e atendimento pedagógico domiciliar: estratégias e orientações. Secretaria de Educação Especial. Brasília: MEC; SEESP, 2002. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. MEC, 2008. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Alteração da Lei n. 9.394/96 pelo texto da Lei nº 13.716, de 24 de setembro de 2018. [ Links ]

CARREIRA, Denise. O direito à educação e à cultura em hospitais: caminhos e aprendizagens do Pequeno Príncipe. Curitiba [Paraná]: Associação Hospitalar de Proteção à Infância Dr. Raul Carneiro, 2016. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Política e Educação. São Paulo, Cortez, 1993. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Professora Sim, Tia Não - cartas a quem ousa ensinar, 4ª ed. São Paulo: Olho d’Água, 1994. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da Autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. São Paulo, Paz e Terra, 1996. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da esperança: um reencontro com a pedagogia da autonomia. Rio de Janeiro, Paz e Terra. 1998. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Papel da educação na humanização. In: Rev. da FAEEBA, Salvador, nº 7, jan. / junho, 1997. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da indignação: cartas pedagógicas e outros escritos. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2000b. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Educação e Mudança. 34ª ed. -São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2011. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo, FAUNDEZ Antônio. Por uma pedagogia da pergunta. 7ª ed. -São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2011. [ Links ]

IMBERNÓN, Francisco. Formação docente e profissional: formar-se par a mudança e a incerteza. 9ª ed. - São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

RANGEL, Mary. Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 32, n. 1, p. 59-64, jan./abr. 2009. [ Links ]

5Children and adolescents under health treatment, enrolled or not in public or private schools all over the country, who have not yet concluded Elementary School.

61919 - Childcare school; 1930 - School for mommies and school for nurses; 1935 - Link to the Medical School of Paraná; 1934 - The Hospital created its nursing course; 1951 - Name change in honor of a medical educator, Dr. César Pernetta; 1996 - Professional Education Center; 2003 - Pequeno Príncipe College.

71987 - Juvenile Project for School-Based Hospitalization; 1988 - Agreement with SEED-PR; 1990 - Agreement with SME-Curitiba; 1990 - Publication of the Child and Adolescent Statute; 1996 - National Education Guidelines and Framework Law; 2002 - Creation of the Education and Culture Department; 2002 - Alive Library; 2003 - Agreement for the Internship field; 2004 - Formalization of study group for the tea; 2005 - Playroom organized by the volunteers; 2005 - Creation of Reading Room; 2005 - Research to defend public policies aimed at hospitalized children and adolescents; 2006 - Elaboration of the political-educational project of the department; 2007 - Agreement with SAREH to serve E.F II and E.M; 2008 - Expansion of the room and activities in the hospital; 2010 - Revision of the pedagogical proposal; 2012 - Expansion and renewal of the tea; 2013 - New projects are incorporated; 2014 - Systematization of team studies. 2016 - Release of the book: “O DIREITO À EDUCAÇÃO E À CULTURA EM HOSPITAIS” (“The right to education and culture in hospitals”) (sem data) - Socialization of knowledge in scientific articles and events. 2020 - Resumption of the internal study group

Received: March 01, 2020; Accepted: September 01, 2020

texto em

texto em