Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Ensino em Re-Vista

versión On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.28 Uberlândia 2021 Epub 29-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v28a2021-56

DOSSIÊ 3 - MUDANÇAS NO SISTEMA EDUCIONAL: DO QUE SENTIMOS FALTA?

Brazil between the past and the future: what we have and what we want

1She has a postdoctoral degree in Education. Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), University Camus of Araguaia (CUA), Barra do Garças, Mato Grosso, Brazil. E-mail: e.denez@yahoo.com.br.

2He has a postdoctoral degree in Education. Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), University Camus of Araguaia (CUA), Barra do Garças, Mato Grosso, Brazil. E-mail: kikoptbg@gmail.com.

3He has a doctorate in education. University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), University Camus of Araguaia (CUA), Barra do Garças, Mato Grosso, Brazil. E-mail: warleycarlos@yahoo.com.br.

This article aims to discuss what we miss about the changes in the Brazilian educational system, taking into account the data existing in the last governments (Bolsonaro, Dilma and Lula), specifically about Basic and Higher Education. Methodologically, it is a theoretical essay (bibliographical and documentary research) with a critical analysis approach. The justification for this study is the policies promoted by the current government that provoke, at national and international level, a wide debate in the media and in the scientific communities. In addition to the possibility of reflecting on the context of the pandemic and the insecurities generated by the absence of government actions. The survey identifies that there is no national system that coordinates the responsibilities for Brazilian education. In addition, there is extreme confusion in the current government, lack of public investment, dispute over a political-ideological project, among other factors that make democratic education management in the country impossible.

KEYWORDS: Brazilian educational system; Public policy; Organization and management of education

Este artigo objetiva discutir o que sentimos falta com relação às mudanças no sistema educacional brasileiro, levando em conta os dados existentes nos últimos governos (Bolsonaro, Dilma e Lula), especificamente sobre a Educação Básica e Superior. Metodologidamente, é um ensaio teórico (pesquisa bibliográfica e documental) com abordagem de análise crítica. A justificativa para esse estudo são as políticas promovidas pelo governo atual que provocam, em nível nacional e internacional, um amplo debate na mídia e nas comunidades científicas. Além de uma possibilidade de refletir sobre o contexto da pandemia e as inseguranças geradas pela ausência de ações governamentais. O levantamento identifica que não há um sistema nacional que coordene as responsabilidades pela educação brasileira. Além disso, há extrema confusão no atual governo, falta investimento público, disputa de um projeto político-ideológico, entre outros fatores que impossibilitam a gestão da educação no país de forma democrática.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Sistema educacional brasileiro; Políticas públicas; Organização e gestão da educação

Este artículo tiene como objetivo discutir lo que extrañamos de los cambios en el sistema educativo brasileño, teniendo en cuenta los datos existentes en los últimos gobiernos (Bolsonaro, Dilma y Lula), específicamente sobre Educación Básica y Superior. Metodológicamente, es un ensayo teórico (investigación bibliográfica y documental) con enfoque de análisis crítico. La justificación de este estudio son las políticas impulsadas por el actual gobierno que provocan, a nivel nacional e internacional, un amplio debate en los medios de comunicación y en las comunidades científicas. Además de la posibilidad de reflexionar sobre el contexto de la pandemia y las inseguridades que genera la ausencia de acciones gubernamentales. La encuesta identifica que no existe un sistema nacional que coordine las responsabilidades de la educación brasileña. Además, existe extrema confusión en el actual gobierno, falta de inversión pública, disputa por un proyecto político-ideológico, entre otros factores que imposibilitan la gestión democrática de la educación en el país.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Sistema educativo brasileño; Políticas públicas; Organización y gestión de la educación

Introduction

Brazil is a country that encompasses a multitude of geographic, social and cultural characteristics. But all this diversity makes it difficult, in a way, to develop an equitable4 education. This becomes a great challenge, especially without the construction of a national system that articulates the different realities. In the general context, the country presents inequalities both in the resources available to educational institutions and in learning outcomes.

Although the term "system" is commonly used in different contexts, giving the impression that it is something previously conceived that can be identified externally, it must be kept in mind that it is not a natural fact, on the contrary, it is a product of human action . Systematizing is, giving unity to multiplicity. And the result obtained is what is called “system”. According to Saviani (2008, p. 3), it is characterized as a “unit of several elements intentionally brought together in order to form a coherent and operative set”.

Currently, there is no national system that coordinates responsibilities for Brazilian education, but this does not mean that there is no legal order for this (TODOS PELA EDUCAÇÃO, 2020). Among them, the Federal Constitution (CF) of 1988 provides for a complementary law to guarantee the establishment of this system (BRASIL, 1988).

It is important to clarify that the National Education System (SNE) is not the same thing as an educational system. While an educational system concerns the organization of education in the country (content, stages of training, among other elements), the national system organizes responsibilities for education throughout the country. In other words, it organizes and distributes functions among municipalities, states and the union, and how these three spheres of government must work collectively (TODOS PELA EDUCAÇÃO, 2020).

For Saviani (1999) the system is a unit of gathered elements, which narrows the relationship between the education system and the education plan. Thus, the SNE must establish the levels of collaboration, which can adjust and facilitate the treatment of existing inequalities in Brazilian education. In addition to the FC, the main documents to characterize a system are the Law of Guidelines and Bases of Education (LDB) No. 9.394/1996; and the National Education Plan (PNE) 2014-2024, which contribute to establishing goals that must be met during the effective period (BRASIL, 2014).

Along with these laws, several bodies are responsible for the functioning of the Brazilian educational system. At the federal level: the Ministry of Education (MEC) and the National Education Council (CNE). At the state level, the State Education Secretariats (SEE) and the State Education Councils (CEE). And, in the municipality, they are the Municipal Education Secretariats (SME) and the Municipal Education Councils (CME).

The purpose of this text is to present what we miss regarding changes in the Brazilian educational system, taking into account the data existing in recent governments (Bolsonaro, Dilma and Lula), specifically with regard to Basic and Higher Education. For this, the methodological procedure used was a bibliographical and documental research with a critical-reflective analysis approach. This discussion is justified because the policies promoted by the current government provoke, at national and international level, a wide debate in the media and scientific associations.

This study addresses data related to the last three elected presidents, in order to understand the constitutive processes of a “Brazilian educational system”. The governments of Lula and Dilma built from 2003 to 2016, the assumption that education is a public good, "a subjective right of every citizen, a public policy under the responsibility of the State, strategic and essential for the new project of development of the nation" (MERCADANTE and ZERO, 2018. p. 24). Bolsonaro is based on common sense, basing Brazilian education on strategies developed in other countries, without recognizing national identity.

To understand these elements and build a robust reflection, the text was divided into five parts, with the introduction and final considerations. In the part that follows, we present some data related to what we have in Basic Education; in the third part of the article, the focus of light is on Higher Education; part four considers the propositions to think about what we need for a system that works in the Brazilian reality.

Brazil: what we have in Basic Education

Lula's and Dilma's governments invested in education like never before in recent history and reached all stages of education. In the conception of these presidents, education is a fundamental human right and one of the main means of access to culture, in addition to being an instrument of economic and social development. For this reason, they prioritized investments in education, from daycare to postgraduate courses, through the adoption of a series of integrated and articulated public policies (PARTIDO DOS TRABALHADORES, 2020).

The bibliographic and documental survey carried out showed that for Early Childhood Education, the first stage in childhood and of extreme relevance for the development of children, the Lula government resumed collaboration with municipalities to increase quality day care places, in addition to strengthening policies geared towards preschool (PARTIDO DOS TRABALHADORES, 2020).

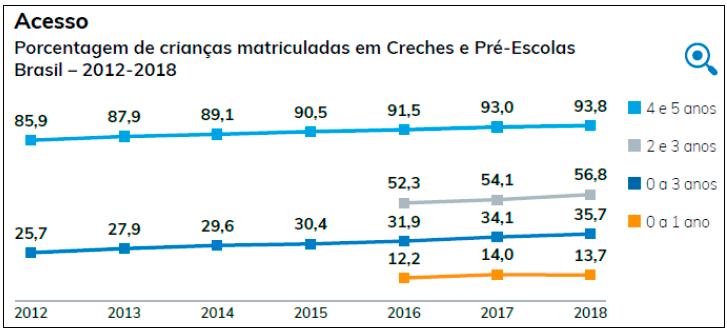

Enrollments in day care centers5 jumped from 1.23 million enrollments in 2003 to more than 3.04 million in 2015, and access to preschool was practically universalized. About enrollments in Early Childhood Education, see information in the following chart:

The data show that enrollment in Early Childhood Education grew 84.7% between 2008 and 2016. It is noteworthy that in 2012, President Dilma launched the Brasil Carinhoso program to support existing day care centers and the construction of new ones with architectural and pedagogical. 2,940 units were completed and delivered by 2015; left in progress, with budget resources assured, another 2,093; 3,167 new day care centers were agreed with the city halls. The government that took over temporarily in 2016 ended the program and abandoned the policy to support Early Childhood Education (MERCADANTE, and ZERO, 2018).

According to the analysis of Todos pela Educação in 2019, already in Bolsonaro's government, Brazil had 1,085 construction work for crèches and pre-schools that were not completed and the smallest transfer of funds since 2009.

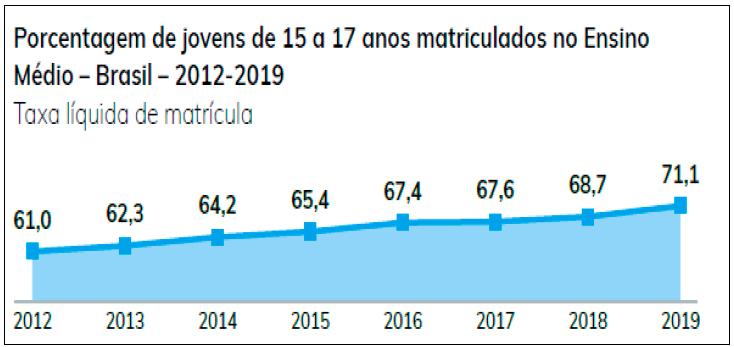

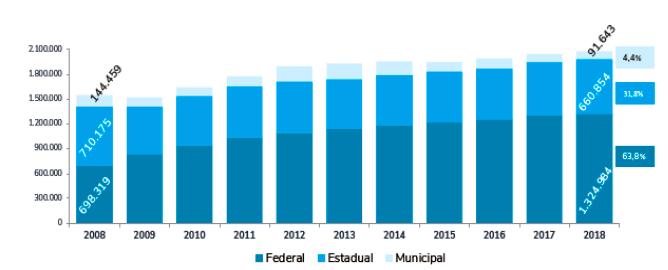

Regarding Elementary and High School, specifically regarding the attendance rate, see the data that follow in graphs 2 and 3.

Source: All for Education Yearbook (2020).

Graph 2 Number of children and young people enrolled in Elementary School

Lula demonstrated, through his government, commitment to all stages and modalities of education. In the country, the number of young people who entered Elementary School and completed High School increased, access to Higher Education increased and teachers gained the institution of a basic salary6.

In addition, there was an emphasis on the National Teacher Training Program (PARFOR), where teachers enroll in courses corresponding to the subjects they teach. Investments in full-time schools and in the More Education Program (MERCADANTE and ZERO, 2018) are also noteworthy.

An important initiative was the democratic process of construction, discussion and implementation of a new Common National Curriculum Base (BNCC), at the beginning of Dilma's second term, seeking a flexible curriculum. Aguiar and Tuttman (2020, p. 71) state that:

Examining the trajectory of construction of the Common National Curriculum Base (BNCC) in the governments of Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016) and Michel Temer (2016-2018) requires a recovery of the context, disputed projects, discussions and related government initiatives to the field of curriculum in the previous administrations of presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC - 1995-2003) and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2011).

As can be seen in Graph 3, in Secondary Education, enrollments in the 15 to 17 age group have grown, which means that 84.6% of the population attend school. Among the poorest 20% of the Brazilian population (in 2002), only 31.6% were in the expected series; and, in 2015, 60.2% were in this condition. Among the poorest 5%, the number of teenagers who accessed school at the right age increased by four times.

Mercadante and Zero (2018) report that the National Program for Access to Technical Education and Employment (PRONATEC), implemented by Dilma, as of 2011, was one of the largest Technical and Vocational Education program in the country's history. It offered 9.4 million vacancies, in order to stimulate productive inclusion and open up new possibilities in the job market, generating professional qualification.

In general terms, the president made explicit in his government plan and during his first year in office, an emphasis on training Basic Education students to carry out large-scale assessments and a high school aimed at training work through professional training courses.

Bolsonaro announced in late September that he will cut resources from areas such as education, health, and others. The financing of services to the needy population is carried out with part of the resources of entities in the S System. The cut will promote a drop in the average rate, which would go from 2.5% to 1.5%. The National Service for Industrial Learning (SENAI) operates through professional training courses and the Social Service for Commerce (SESC) has schools, theaters, health services, sports clubs, cultural incentive awards and artistic and cultural events. This government action tends to harm the population7.

Brazil: what we have in Higher Education

The social, economic, political and cultural transformations were extensive in these popular governments, so much so that Brazil did not even have many conditions to extract consistent analyzes and projections after the “hurried” and “induced” departure of Dilma from the presidency of the republic. Sader and Garcia (2010) reveal that the country was one of the most unfair in the world and was taken to a category of lesser inequalities, projecting it, at the time, to become the fifth largest economy on the planet.

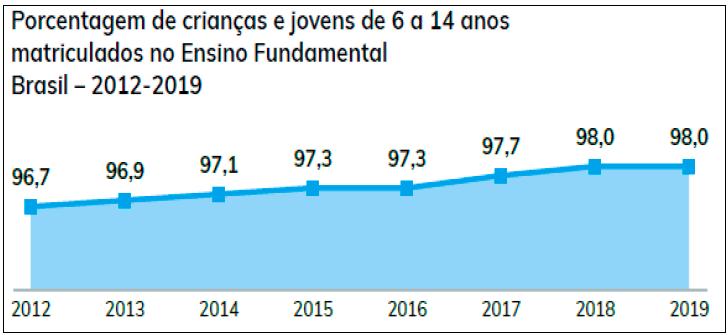

Regarding the network of federal universities in the Workers' Party (PT) governments, there was the greatest expansion in its history. In 2002, it was made up of 45 universities with 148 campuses, and in 2015 reached 65 universities with 327 campuses. Mercadante and Zero (2018) report that a total of 18 universities, 173 campuses and hundreds of units of the Federal Institutes of Education (IFES) were created under Lula and Dilma.

At the end of Dilma's government, there were 38 IFES distributed in 600 campuses. Enrollments doubled, from 558,000 students in 2002 to more than 1 million in 2015. All this expansion promoted the inclusion of a portion of the population that had been historically excluded. Access occurred with greater emphasis through the National Secondary Education Examination (ENEM) in 2009 under the Lula government (BRASIL, 2019).

In order to expand access to Higher Education, several actions were taken during this period, including: maintenance of the Support Program for Restructuring and Expansion Plans at Federal Universities (REUNI); restructuring of the University for All Program (PROUNI) and the Student Financing Program (Fies)8.

The Quotas Law (No. 12,711/2012) also increased the democratization of Higher Education, facing social inequality and racial discrimination, seeking to ensure access policies for low-income, black and indigenous public school students. Higher Education financing policies strengthened the expansion of opportunities, the Unified Selection System (SISU) included and expanded the opportunity of millions of young people (BRASIL, 2019).

From this set of measures, it is possible to infer that 35% of graduates who took the National Student Performance Examination (ENADE) in 2015 were the first in their families to graduate. Mercadante and Zero (2018) confirm the presence of young black people in this process. With regard to teacher training, the Open University of Brazil (UaB) offered free distance education to the network's teachers and the Institutional Program for Initiation to Teaching Scholarships (PIBID) was created9.

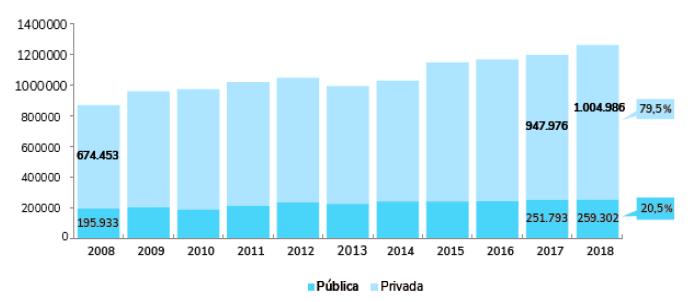

In the graphs that follow, it is possible to observe the advance in enrollments in the last 10 years, by administrative category (federal, state and municipal universities) and the data of the graduates that allow a reflection on the emphasis given to Higher Education in the Lula and Dilma administrations.

Source: Census of Higher Education (2018).

Graph 4 Enrollments in undergraduate course in the public network (2008/2018)

Source: Census of Higher Education (2018).

Graph 4 Enrollments in undergraduate course in the public network (2008/2018)

It is noteworthy in this context that the Science without Borders Program created at the beginning of the Dilma government, acted as an advance in international student mobility and in the promotion of internationalization, taking around 100,000 Brazilian students and researchers to universities and research centers in 54 countries. Investments in education, science, technology and innovation also grew significantly in the PT governments (MERCADANTE and ZERO, 2018).

Another program proposed by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), in 2017, was Mais Ciência Mais Desenvolvimento, which aimed to integrate actions related to the internationalization of graduate programs, however, it had a short duration. Soon after, in the same year, it was replaced by the Institutional Internationalization Program (PRInt), which sought to foster the construction, implementation and consolidation of strategic plans for the internationalization of HEIs in the prioritized areas of knowledge (NEZ and MOROSINI, 2020).

In the current president's government, because of the unrestrained advance of the coronavirus, CAPES officially informed that all PrInt mobility actions scheduled for 2020 would be suspended. In this context, it was impossible to carry out the actions. Countries limited the internal mobility of citizens, which impacted teachers who were already outside Brazil. These were disoriented due to a brutal change in behavior in the face of the pandemic, immobilized in the target countries and unable to carry out the planning. The academic semesters were overstated and the inability to implement the projects and research missions that should be developed was installed (NEZ and MOROSINI, 2020).

Finally, it is necessary to remember that the role of the public university in the face of Constitutional Amendment 95 (EC 95) approved by the Temer government (2016), which instituted a New Fiscal Regime (NRF) in the country with the spending freeze, had already made the educational public policies in both Basic and Higher Education, putting the university and the existence of research at risk (BORSSOI and NEZ, 2019). The research model defended by the Bolsonaro government is applied research, as it considers that the field of science and knowledge should never be sterile. It also prioritizes some areas over others and has been intensifying partnerships with the private sector and the tendency to tighten up the ideological control of students and teachers.

Bolsonaro is based on common sense, disregards numerous researches and statistics, guides Brazilian education in the strategies developed in Japan, Taiwan and South Korea. However, after twenty months of government, nothing has been articulated for Education, only its financial dismantling. What was implemented during this initial period of government instigates intolerance to Marxism, Paulo Freire, the discussion of gender at school and other controversial elements.

Brazil: what we want

The structuring of contemporary education is manifested in a dialectical relationship, namely, it now moves towards utopia, with the potential to transform the reality of providing human education to everyone regardless of social class, color, gender and sex.

On the other hand, the same education manifests itself with disenchantment, due to the distance from human formation and its impotence in dealing with the objective reality of the data presented throughout this study. Systematized education is characterized by a contradiction, as there are those who defend the logic of the highest social strata (owners of capital); these, in turn, defend the training of labor that serves the market and, thus, offer education based on technique.

In the opposite direction, there are those who defend that what is produced in society and by society belongs to everyone, thus, the technique aimed at the labor market would be just one of the different lines of action of the school. In this way, it would not only teach the “dead letter”, but how life is produced through literature, in the different manifestations of art, not to mention the basics, which is the teaching of science.

Based on education as a fundamental human right and one of the main means of access to culture, the subject going through school should be able to read the world in different perspectives, which represents the possibility of understanding the ways of feeling, thinking and act in the world.

The birth of a child represents the clear need to build a new world, with other possibilities to reinvent feeling, thinking and acting on reality. However, when an eminently technical education is insisted on, without any social transformation, a legion of cultural illiterates is generated.

This fact generates prejudices, prejudices, due to groups that believe that their culture is superior to others, this guarantees the support of the different manifestations of violence. Therefore, it is understood that investment in education is much greater than financial investment, it must be in human training for students and teachers.

This proves that human formation is summarily passed by smell, motricity, vision, although these dimensions are characteristic of the species from a biological point of view, it is argued that they are developed in and by culture and not only by the neurophysiological dimension, as a vision points out. technical education. Therefore, the school to have social quality needs to be organized to present these dimensions to students and teachers.

Therefore, the human formation of social quality, defended and announced here, presupposes not only a technical formation, here understood as bureaucratic courses that teach/train teachers to use the bureaucratic machine of the state. But, on the other hand, that this formation underlies the erudition of the faculty in the direction of introducing the student to the erudite world. This issue is clarified by Souza (2017):

As the stimuli to reading and imagination are less, the poor almost always have enormous difficulties in concentrating at school. Many report in interviews that they stared at the blackboard for hours without being able to learn the content. The ability to concentrate is therefore not a natural fact like having two ears and one mouth, but rather an ability and disposition for behavior learned only when properly stimulated (p. 98).

Therefore, one is not born ready to learn, on the contrary, an adult/teacher is essential to teach concentration, to interact with the organized and systematized knowledge in the educational institution. This means to say that there is no point in having a quantitative percentage of children and young people enrolled in Elementary and High School if there is no such relationship between the student and the teacher. Ensuring access is important, however, permanence must be guaranteed with an emphasis on policies and programs that aim to guarantee this quality social education in public schools.

In the last two decades, public policies, resulting from the indicated governments and the correlation of forces, whose demands in/from civil society and social movements are highlighted, there was a process of democratization of the right of access to Basic Education.

As Souza (2017) expose, there are those who receive it from the “cradle” and become privileged.

This is how typically middle-class privileges are formed so that their monopoly on valued knowledge is maintained across generations. For the adult child, with a job and well paid and with social prestige, everything is perceived as if it were a miracle of individual merit (SOUZA, 2017, p. 98).

Objectively, the university should not expect a “miracle” in the training of teachers from different degrees; and, in turn, when academics become responsible for a classroom, they cannot expect a “miracle” from the educational system; both should make it possible to do the prodigy. Thus, continuing education is:

[...] a complex and multi-determined process, which gains materiality in multiple spaces/activities, not restricted to courses and/or training, and which favors the appropriation of knowledge, stimulates the search for other knowledge and introduces a fertile continuous restlessness with the already known, motivating to live teaching in all its imponderability, surprise, creation and dialectic with the new (PLACCO and SILVA, 2009, p. 27).

PIBID is one of those moments that can provoke reflections in undergraduates and changes in the school reality. Gatti et al (2014, p. 5) explains that undergraduate students perform activities in public schools of Basic Education, “[...] contributing to the integration between theory and practice, to bring the University and schools closer together and to improve quality of Brazilian education”.

It is evident that this proposition needs to break with the model of training students and teachers, the school needs learning that provides the appropriation of the world in a human way. Thus, PIBID and, later, Residência Pedagógica, as teacher training programs, corroborate the dialogue between the university and the school. Responding to the main objective of this study, there is a lack, then, of policies for the continuity of these actions that constitute the systematization of a state policy that has a permanent character.

Still on what is absent or non-existent in the Brazilian educational system, it is worth reflecting on the meanings of democracy in school relations. Democracy cannot be for simple contemplation, it must be thought of in an active and responsible way in an intrinsic relationship between man and nature, denying the hyper individualism proclaimed in the current historical moment. From this, it is only possible to think about education in a collective way,

In any case, private property is only the sensible expression of the fact that man becomes objective for himself and, at the same time, becomes better a strange and inhuman object, the fact that his vital exteriorization is his vital alienation, its realization is its de-realization, a strange reality, the overcoming of private property, that is, sensible appropriation by and by man of the essence and sense of immediate, exclusive enjoyment, in the sense of possession, of having. Man appropriates his universal essence in a universal way, that is, as a total man. Each of your human relationships with the world (seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, feeling, thinking, observing, perceiving, desiring, acting, loving), in short, all the organs of your individuality, such as the organs that are immediately community in their form, they are, in their objective behavior, in their behavior from the object, the appropriation of it. The appropriation of human reality, its behavior from the object, is the affirmation of human reality, it is human efficacy and human suffering, because suffering, humanly understood, is a enjoyment of man himself (MARX and ENGEL, 2004, p. 41).

For this reason, the Brazilian educational system must be organized to guarantee that the human being develops humanly, and this only occurs in the presence of equal rights. Thus, school knowledge cannot deprive students and teachers of their humanity.

Education is the opportunity to share the world, so it is the opportunity to deny a project of society that makes an apology to hegemonic modernity and that sustains itself in individuality to carry out an education proposal based on the public, on the universal and on a democracy that can release.

For Santos (1999), the project of society of a hegemonic modernity makes it seem that the political world has come to its end, everything seems to indicate that, in fact, with the loss of human rights, the subject of rights entered a crisis, which leads to untamed individualism. This privatizes human relations, which gives formal education another model that summarily excludes the most fragile, the vast majority of the population.

The subjectivation of rights and, as a consequence, in human formation (education), removes from the center of these relationships the concrete man, who aims to be replaced by an abstract being, who gives his own meaning to the construction of his humanity. As a result, we have:

The intellectual obliteration of adolescents, artificially produced by transforming them into simple machines for producing surplus value, is quite different from that natural ignorance in which the spirit, although uncultured, does not lose its capacity for development, its natural fertility (MARX and ENGEL , 2004, p.69).

This leads to the reflection that, for the realization of a human-centered education project, there must necessarily be a State that administers with and for the population and, not that at times the government thinks of the upper stratum of the social pyramid, of the owners of the capital. And that at other times, there is a government that manages for the lower stratum, the worker, this polarized relationship tensions social relations that sometimes tend to one side, sometimes to the other. In Higher Education, the FIES, the SISU, the quota law, among other actions, is the demonstration that the government manages for the worker. On the other hand, there are other situations that make the propositions clear only for the owners of means of production.

As a consequence, the weakest in society are not protected from this destructive relationship, such protection can only be given with the maintenance of a strong State that guarantees effective human formation for all. Definitely, this is what is missed when thinking about programs and policies for the implementation of the educational system. On the other hand, in the current government there is a lack of funding, absence of policies, among other factors that impede any type of training.

Conclusion

Taking into account the objective proposed in this theoretical essay, it is possible to see that the Brazilian educational system is a hybrid of advances and setbacks. Setbacks have historically distorted the capacity of responsible bodies at municipal, state and federal levels to produce State policies and not just government policies.

The data collected show that from 2003 to 2016, significant advances were made, however, with the media juridical coup, which overthrew the government of Rousseff, which brought to power an indigestible mixture of a Nazi-fascism that put the “round earth” in a trance.

This study sought to think about what is missed in relation to changes in the Brazilian educational system. There is an absence of the SNE that was stated in goal 20 of the PNE, in its strategy 20.9, which should articulate the national system of education in a collaborative regime. However, after almost four years, what is left are setbacks.

Another point of advance, but which tends to become a setback over time, is the approval, in August 2020, of the National Fund for Development of Basic Education (Fundeb). It is an important milestone, considering that it was an unprecedented defeat in republican history in which the government did not intend to have the fund approved as law. The new Fundeb is the main financing mechanism for public Basic Education in Brazil. The great challenge for not falling into oblivion and non-existence will be to draw up a complementary law to regulate the fund.

From the point of view of governance, at this historic, pandemic moment, there has been more setbacks than advances. From the point of view of the structuring of Basic and Higher Education, the dialectical relationship, a space of utopia, with the potential to transform human formation to everyone regardless of social class, color, gender, sex, is aggravated by the lack of sensitivity to the most elementary respect for the social contract of coexistence - respect for the other. The image below summarizes the concerns regarding the Brazilian educational system.

Finally, what do you miss about the changes in the Brazilian educational system? It is necessary to invest in public policies that institutionalize concrete acts in favor of those below the poverty line. These need to generate income, employment, greater participation of the less favored in the labor market, short, medium and long-term actions that increase the education of the less favored at all levels.

It is necessary to recover the path of public policies that generate social inclusion, itineraries that plan, deliberate and create a set of activities aimed at the social and educational development of needy families. More than ever, reality shows the “naked eyes” process of invisibility imposed on those living below the poverty line.

The most visible scenario for auditing the reflected reality seems to be education, as it is the inalienable right that best serves the population on a daily basis. Every day more than 50 million children and young people are served in schools.

What, then, is the hope? Interacting, connecting, dialoguing, proposing, making human formation think in a committed way in a non-alienated way, saying no to neoliberalism, fascism and any form of extremism.

Moving into the future thinking that the “new abnormality” provided by COVID-19 makes government leaders more humane. It is essential to have hope that nurtures dreams, realities of another time, of a new announcement of autonomy and resilience.

This text not only shows the legacy received from the past and the transformations carried out, but also points out the path to take to make this a truly democratic, solidary and sovereign country. Therefore, one must advance in this giant Brazil.

REFERENCES

AGUIAR, M. A. da S.; TUTTMAN, M. T. Políticas educacionais no Brasil e a Base Nacional Comum Curricular: disputas de projetos. Em Aberto, Brasília, v. 33, n. 107, p. 69-94, jan./abr. 2020. Disponível em: file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/4556-Texto%20do%20artigo-5322-1-10-20200730.pdf. Acesso em: 04 out. 2020. [ Links ]

ANUÁRIO todos pela educação. Disponível em: https://www.todospelaeducacao.org.br/conteudo/anuario-2020-Todos-Pela-Educacao-e-Editora-Moderna-lancam-publicacao-com-dados-fundamentais-para-monitorar-o-ensino-brasileiro/. Acesso em: 01 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BORSSOI, B. L.; NEZ, E. A universidade pública e a emenda constitucional 95/2016: qual será o futuro da pesquisa? In: Política e Gestão da Educação Superior. Brasília: Anpae, 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição da república federativa do Brasil 1988. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2007. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação (PNE). Brasília. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2014/Lei/L13005.htm. Acesso em: 01 jun. 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 9.394 de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Leis/L9394.htm. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2009. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Programa ciência sem fronteiras. Disponível em: http://www.cienciasemfronteiras.gov.br/web/csf. Acesso em: 26 set. 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. 2003 a 2010: biblioteca da presidência - planalto. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/planalto/pt-br/conheca-a-presidencia/acervo/biblioteca-da-presidencia. Acesso em: 10 dez. 2019. [ Links ]

CENSO da Educação Superior 2018. Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/web/guest/educacao-superior. Acesso em: 8 maio 2020. [ Links ]

DICIONÁRIO de significados. Disponível em: https://www.significados.com.br/equanime/#:~:text=O%20que%20%C3%A9%20Equ%C3%A2nime%3A,igual%2C%20anime%20%2D%20%C3%A2nimo. Acesso em: 21 set. 2020. [ Links ]

FIES. Disponível em: http://sisfiesportal.mec.gov.br/?pagina=fies. Acesso em: 05 ou. 2020. [ Links ]

GATTI, B. A.; et al. Um estudo avaliativo do programa institucional de bolsa de iniciação à docência (PIBID). São Paulo: FCC/SEP, 2014. Governo quer reduzir os recursos do Sistema S. Disponível em: https://www.bancariosbahia.org.br/noticia/29737,governo-quer-reduzir-os-recursos-do-sistema-s.html. Acesso em: 05 out. 2020. [ Links ]

CENSO da Educação Superior. 2018. Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/web/guest/educacao-superior. Acesso em: 8 mai. 2020. [ Links ]

JAPIASSU, H.; MARCONDES, D. Dicionário básico de filosofia. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 2001. [ Links ]

MARX, K.; ENGELS, F. Textos sobre educação e ensino. Trad. Rubens Eduardo Frias. São Paulo: Centauro, 2004. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/reuni-sp-93318841. Acesso em: 05 out. 2020. [ Links ]

MERCADANTE, A.; ZERO, M. (orgs.). Governos do PT: Um legado para o futuro. São Paulo: Fundação Perseu Abramo, 2018. [ Links ]

NEZ, E. de.; MOROSINI, M. C. Programa institucional de internacionalização (PRINT): análises frente a uma pandemia. Debates em educação, v. 12, p. 77 - 94, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.28998/2175-6600.2020v12n28p77-94. [ Links ]

O NACIONAL. 2016. Disponível em: https://www.onacional.com.br/politica,8/2020/07/24/temer-assume-presidencia-em-def,72297. Acesso em: 29 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

PARTIDO DOS TRABALHADORES (PT). Os governos do PT fizeram uma verdadeira revolução na educação do Brasil. Disponível em: https://lula.com.br/os-governos-do-pt-fizeram-uma-verdadeira-revolucao-na-educacao-do-brasil/. Acesso em: 15 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

PLACCO, V. M. N. S.; SILVA, Sylvia Helena Souza da. A formação do professor: reflexões, desafios, perspectivas. In: BRUNO, Eliane Bambini; ALMEIDA, Laurinda Ramalho; CHRISTOV, Luíza Helena da Silva (org). O coordenador pedagógico e a formação docente. São Paulo: Edições Loyola, 2009. [ Links ]

PROUNI. Disponível em: http://prouniportal.mec.gov.br/. Acesso em: 05 out. 2020. [ Links ]

SADER, E.; GARCIA, M. A. Brasil entre o passado e o futuro. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2010. [ Links ]

SANTOS. L. G. dos. Tecnologia, perda do humano e crise do sujeito do direito. In: OLIVEIRA, F. de ; PAOLI, M. C. Os sentidos da democracia: politicas do dissenso e hegemonia global. Petrópolis: Vozes: 1999. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D. Educação brasileira: estrutura e sistema. 10. ed. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2008. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D. Sistema de ensino e planos de educação: o âmbito dos municípios. Educação e sociedade, a. XX, n. 69, dez. 1999. [ Links ]

SOUZA, J. A elite do atraso da escravidão a lavo jato. Rio de Janeiro: Leya, 2017. [ Links ]

SOUZA, W. C.; NEZ, E. Diálogos entre universidade e educação básica: o PIBID como interlocução na formação de professores. Educação, cultura e sociedade. Sinop, v. 10, n. 1, p. 66-79, jan./jun.2020. [ Links ]

TODOS PELA EDUCAÇÃO. Disponível em: https://www.todospelaeducacao.org.br/conteudo/O-que-e-um-sistema-nacional-de-Educacao. Acesso em: 21 set. 2020. [ Links ]

4From the Latin aequanimus (aequi - equal, anime - spirit) it means impartiality and equality. It is what has or demonstrates moderation, justice, it is the willingness to equally recognize the right of each one (DICIONÁRIO, 2020).

5The concept of day care has undergone numerous changes over the years, reaching a legal definition in LDB 9.394/96: "Childhood Education, the first stage of Basic Education, aims at the integral development of children up to six years of age, in their physical, psychological, intellectual and social aspects, complementing the action of the family and the community” (Article 29). In this way, crèche and pre-school are definitively inserted in the educational sphere.

6Implemented by Lula, it allowed a real growth of salaries in Basic Education of approximately 49%, between 2009 and 2015. Investments in initial and continuing teacher training carried out through the creation of the National Pact for Literacy in the Right Age (2012), by the government Dilma secured a scholarship and a special training program for around 300,000 literacy teachers (TODOS PELA EDUCAÇÃO, 2020 and MERCADANTE and ZERO, 2018).

7Available at: https://www.bancariosbahia.org.br/noticia/29737,governo-quer-redutor-os-recursos-do-sistema-s.html. Accessed on: 05 oct. 2020.

8MEC program designed to finance the graduation of students enrolled in non-free higher education courses in accordance with Law No. 10,260/2001 (FIES, 2020).

9One of the actions of the National Policy for Teacher Training of MEC that aims to provide students in the first half of undergraduate courses, an approximation with the daily life of Basic Education schools. At the end of 2017, already under the Temer Government, the Pedagogical Residency Program and a restructuring of PIBID are under way, which begins to be implemented in 2018 (SOUZA and NEZ, 2020).

Received: October 01, 2020; Accepted: February 01, 2021

texto en

texto en