Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Ensino em Re-Vista

versión On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.28 Uberlândia 2021 Epub 29-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v28a2021-15

ARTIGOS DE DEMANDA CONTÍNUA

The funeral as a socio-educational space for the Rikbaktsa people1

2Doutorado em Educ. Matemática. Unesp-Rio Claro/SP- Brasil. E-mail: adailtonalves5@uol.com.br.

3Mestrado em Ensino de Ciências e Matemática. PPGECM - Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso. Campus de Barra do Bugres/MT - Brasil. E-mail: elani_lobato@hotmail.com.

This article is an excerpt from the research for the writing of the Master's Dissertation and focuses on the Rikbaktsa people, with the objective of identifying and understanding the socio-educational processes (generation, systematization and diffusion) of the group from the funeral events celebrated in the space of the village. The methodological approach was anchored in the Ethnomathematics perspective, under the perspectives of D’Ambrosio (2005, 2016 and 2017) and Vergani (2007). The investigation was of an ethnographic character, with a qualitative approach, using observation. As a result, we obtained an understanding of the traditional knowledge disseminated by the elderly to the youngest, which can contribute to highlight the knowledge and practices of the youngest.

KEYWORDS: Ethnomathematics; Original knowledge; Traditional crafts

O presente artigo é um recorte da pesquisa para a escrita da Dissertação de Mestrado e traz em foco o povo Rikbaktsa, com objetivo de identificar e compreender os processos socioeducativos (geração, sistematização e difusão) do grupo a partir dos eventos fúnebres celebrados no espaço da aldeia. A abordagem metodológica ancorou-se na perspectiva Etnomatemática, sob as perspectivas de D’Ambrosio (2005, 2016 e 2017) e de Vergani (2007) . A investigação foi de caráter etnográfico, com uma abordagem qualitativa, utilizando-se da observação. Como resultado obtivemos a compreensão dos conhecimentos tradicionais difundidos pelos mais velhos aos mais novos que podem contribuir para evidenciar os saberes e fazeres dos mais jovens.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Etnomatemática; Saberes originais; Fazeres tradicionais

Este artículo es un extracto de la investigación para la redacción de la Tesis de Maestría y se centra en el pueblo Rikbaktsa, con el objetivo de identificar y comprender los procesos socioeducativos (generación, sistematización y difusión) del grupo a partir de los actos funerarios celebrados en el espacio del pueblo. El enfoque metodológico estuvo anclado en la perspectiva de la Etnomatemática, bajo las perspectivas de D’Ambrosio (2005, 2016 y 2017) y Vergani (2007). La investigación fue de carácter etnográfico, con enfoque cualitativo, mediante la observación. Como resultado, obtuvimos una comprensión de los conocimientos tradicionales que los adultos mayores difunden a los más jóvenes, lo que puede contribuir a resaltar los conocimientos y prácticas de los más jóvenes.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Etnomatemáticas; Conocimiento original; Artesanía tradicional

The lack of a predetermined trail is not a problem.

On the contrary: it frees us from dogmatic views.

However, it requires greater clarity about where we want to go.

Alberto Acosta

Introduction

The Rikbaktsa people within their specificities, in their natural / social environment, were called by the rubber tappers as a canoe people for having great skill in handling canoes, living in the northwest region of the state of Mato Grosso, along the high courses of the rivers Juruena, Sangue and Arinos.

The population of this group is currently distributed in 36 villages that make up its three areas called Indigenous Lands: Erikpaktsá, Japuíra and Escondido on the banks of the flow of the aforementioned rivers, occupying today only 401,382 hectares, which were part of an area of 50,000 km2, before contact with non-indigenous people (DORNSTAUDER, 1975; ARRUDA, 1992).

The research focused on the Rikbaktsa that inhabit the Beira Rio, Segunda Cachoeira, Segurança and Primavera villages, all in the Erikpaktsá TI. With these subjects, we aim to understand and identify the processes of production, systematization and diffusion of the people's knowledge and practices, based on funeral events celebrated in the different spaces of the villages, and their articulation with the Indigenous School Education inserted in the communities.

In the locus of the research, the context of everyday occurrences of the Rikbaktsa people was observed. In this process, we also observed the organization of daily activities, the division of labor and the internal relationships perceived by direct contact with the people, which led us to experience what Barros and Junqueira (2011) advocate when they state:

What human beings perceive when observing the world is, therefore, the product of a very complex operation, in which the subject-observer, the observed object, the interpretive schemes used by the observer and the context in which such observation takes place are involved and acquires or finds meaning (BARROS; JUNQUEIRA, 2011, p. 34).

The data produced by the insertion in the daily context of the villages were analyzed from the perspective of Ethnomathematics Education, anchored in the thoughts of D’Ambrosio (2005, 2016, 2017) and Vergani (2007).

Ethnomathematics Education presents itself as a posture of socially contextualized holistic education that questions reality as a starting point that different human groups have successively applied to mathematical activities, giving rise to an intense load of human meaning, which emerged in the form of symbolic social aspects. that serve as the basis for a research program related to the generation, intellectual organization, social organization and dissemination of knowledge (VERGANI, 2007); (GERDES, 2012) and (D’AMBROSIO, 2005, 2016, 2017).

Mathematical Education experienced as a practice of freedom in an Ethnomathematics perspective promotes mutual knowledge between man and men, in a dynamic in which “freedom is conceived as the way of being the destiny of Man, but for this very reason it can only have meaning in history that men live” (FREIRE, 2011, p. 6).

In the proper way of being and perceiving themselves in the world, there are many and not limited the socio-educational spaces of the Rikbaktsa people, but we will focus specifically on the place practiced at the funeral, due to the set of symbols and the global way that this ritual covers a series specificity of the people in question.

In the cosmological view of the Rikbaktsa people there is an exchange of "souls" between beings in the physical world. They believe that there is continuity after death and the fate of the dead is subject to what he did during his life here on Earth. According to the people, some Rikbaktsa return incarnated as human beings, indigenous and non-indigenous, or incarnate animals as "night monkeys". Those Rikbaktsa who were bad, perverse people who did bad things come back as dangerous spirits to men, like the jaguar or poisonous snakes. (ARRUDA, 1992).

The Rikbaktsa funeral is a ritual composed of myths, rites and ceremonies elaborated based on the social organization of the people, which from which the funeral celebration dies takes on distinct characteristics that are structured from the announcement of the death, to the preparation of the ritual that includes the rite of lamentation (crying), permeates the burial and determines the behavior of relatives after the death of the loved one.

In this configuration, there is a whole mathematical system that characterizes the actions of the people who are involved in the funeral ritual, which highlights the people's ethnomathematics. Perception that was built during the research, during the production of data for the writing of the Dissertation that gave rise to the present work.

Aspects inherent to the Rikbaktsa people

When referring to the nature of the name of their people, the Rikbaktsa always translate it as a warrior people and speak of it with great emphasis on the meaning of the name. This tonic is unanimous and present in all the speeches of the leaders when they meet, either in ordinary meetings with the community or in confrontation meetings in the most varied spaces that propose to proclaim the defense of the rights of indigenous peoples and the freedom of be as they are, inhabiting their original spaces (PAIMY, 2018). As Zapemy Mykpezazi Rikbakta, elder leader of the Rikbaktsa people reports, when declaring:

Rikbaktsa did not have a single place, we were not stuck anywhere and at the same time we were from everywhere. We walked everywhere, and nothing stopped us, if the enemy tried, we already got them out of our way. We were free to go where we wanted. We went up the Tapajós, took the Teles Pires, there on the Rio Norte arm, went to the South arm, went to the head of that river to get taquara in Rio Grande. Many moons walked, arrived at Sete Quedas, several moons passed, we arrived at the Peixoto River, we returned to the North arm, we went again to the South arm to get more taquara. There, there was conflict with Indians with the “beiços” made of wood, they did not want to let taquara be removed. We used to go to Serra do Cachimbo, before we passed through the cerrado. We walked through Amazonas, Pará, Mato Grosso, Rondônia. These names were given by the white, for us it was all about walking, looking for food, looking for material for our weapons, looking for medicine, looking for material for our ornaments. Place for us to live, but white people arrive and set limits, put names, tell us how far we can go (Text produced from the personal testimony of ZAPEMY MYKPEZAZI RIKBAKTA, 1997).

Zapemy Mykpezazi Rikbakta's narrative shows his understanding of himself as a free being to come and go, as well as his conception of place in the world. Her report also reveals her understanding of being indigenous, in her natural / social / cultural environment.

His speech discusses his perception of space, diverging from the concept of non-indigenous man. The analysis that the elderly does, is against the limits that the non-indigenous society determines for the indigenous, who understand their spaces of experiences under a finite dimension. However, the elder considers the territory as an infinite space in which any and all places where the indigenous person wishes to go do not prescribe limits or obstacles.

This conception of territory is based on the elder's world reading and on his specific needs for living and survival, together with an action of freedom in which, the indigenous person is the one who determines his space and place in the world, in line with the thought of Melià on indigenous freedom, declaring that “the indigenous person does what he wants, with freedom sometimes almost bordering on anarchy, since each Indian is himself. Alterity, after all, is the freedom to be oneself” (MELIÀ, 1999, p. 12).

The Rikbaktsa people are constituted as a society organized by the division of two exogamic halves, whose initial configuration is formed by a social unit linked to a common ancestor by ties of descent. Fact that for Hahn (1976), it is a Patrilineal (agnatic) descent relationship, that is, the mother does not consist of a link, but only the parents give rise to parental formatting which in the case of this group can be included in the description of Castro (1986) that says:

[...] in a restricted way, dualist organizations or societies organized in moieties, i.e., societies that classify all or part of their members (when men in general part) into two complementary halves. These halves may have the function of regulating matrimonial exchanges (exogamous halves, which in certain cases are subdivided into clans and lineages), economic exchanges, the distribution and performance of ceremonial roles, the functions of political authority and various other aspects of social life. In many cases, the halves share the universe in elements related to each one (CASTRO, 1986, p. 373).

Castro's description (1986) converges to the organization of the social unit Rikbaktsa which is structured by two halves complemented by clans and their lineages. We present this organization from the halves, distributed in clans, configured by the reports of the elders: Mapõ, Tubui, Pentsa and Aikdou Rikbakta from the villages Segunda and Segurança, in the Indigenous Land Erikpaktsa, in the municipality of Brasnorte in Mato Grosso, in one of the organized meetings for data production in September 2019.

In the specific case of the Rikbaktsa this is formatted as follows: Makwaratsa ‘yellow macaw’ (Ara ararauna) and Harobiktsa ‘head macaw’ (Ara chloroptera). These two halves are, in turn, made up of several clans, designated by the name of the main clan (ATHILA, 2006), which is formed: sometimes by an animal, sometimes by a vegetable, maintaining a simple link with these elements of the kingdoms animal and vegetable, indispensable marks of the Amazon rainforest, effective housing for the people of Mato Grosso.

In this perspective, what constitutes the clan division incisively are the halves that are visibly distinct in cultural festivals by the paintings of each, signaling structuring roles both in festive events and in events such as the funeral ritual. These events are basically structured by the organization of these halves that can be identified by the graphic reasons, showing that

[...] the halves and their respective clans are associated with certain graphic reasons to which each individual recognizes himself as a person and a social subject. The paintings are not used in everyday life, appearing only during the time of ritual ceremonies, when each one is painted, body and face, by someone from his own patri-clan, especially by a brother (SANTOS, 2002, p. 10 ).

In the specific case for performing rituals, whether they are of any nature, the halves are essential in the configuration that determines the roles of each one. In these cases, painting is a determining part of identifying key elements within each ceremonial.

Mytyk: from the funeral ritual to the Rikbaktsa cemetery

For the Rikbaktsa, the funeral ritual is a rich source of the teaching and learning process. The space of the ceremony is made up of those who die, paying attention to the half that belongs to the dead within the organization of the clans.

All ritualistic steps are linked to the formatting of the event that must be followed to the letter so as not to bring bad omen to those who are alive or to prevent the steps of those who follow to another dimension. Considering the perspective that:

[...] from sleeping on waking up, the “body” is exposed to risks, either through the relationships involved in the village sociality, body postures, mental attitudes and food, whether in dreams or in what they foreshadow. As long as you have a "body", you must seek obedience to a multitude of recommendations, an individual ethic with the aim of "maintaining life". Surviving indicates the success of Rikbaktsa body building, despite this being a process that is never completed (ATHILA, 2006, p.6).

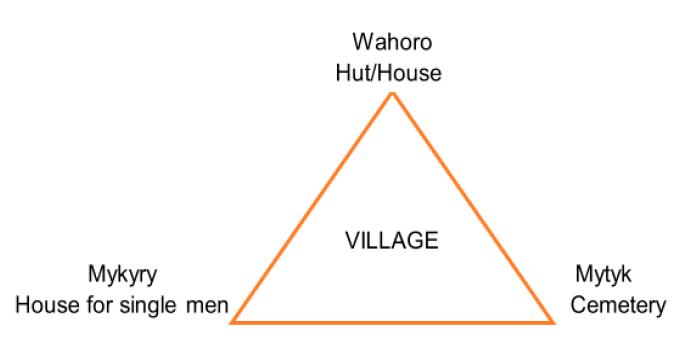

The relationship between surviving and transcending is intertwined in the daily practices in the socio-educational spaces constituted from the house, the men's house and the cemetery, determining behavior, implying choices. According to the elder Tsikbaktsamy, in the village space there were only three buildings in the past: the house (wahoro), the men's learning house (mykyry) and the cemetery (mytyk) which determined the spatial organization of the village, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 took this format from the narrative of the elder who made the following description, according to the textualization of his narrative below.

Our village was neither too big nor too small, but it had everything in the others: wahoro, mykyry and mytyk. Wahoro was higher, on that side was mykyry, (points with his lip to the left elbow from where he located wahoro with his hand) and mytyk was on that side. (Points with his lip to the right elbow from where he located wahoro with his hand). (Testimony from TSIKBAKTSAMY, 2019, Aldeia Segurança).

The elder made gestures with the use of some parts of the body and signaled the location of the three buildings, which were determined according to the elder Tubui, from Aldeia Segunda, taking the sun as a reference for the definition of the house, the mykyry and mainly the mytyk which should be located on the side where the sun rises, in the village space, as shown by the elder in Figure 2.

Although other groups of indigenous Brazilians organize the space of their villages in a circular format, Tsikbaktsamy delineates the space of the Rikbaktsa village in a triangular configuration, when using the body itself to describe its natural environment from the house (wahoro), having as a reference the sunrise (haramwe).

The elder Tsikbaktsamy exposes several elements related to the mytyk, presenting the cemetery as a circular space, describing in great detail how the people arranged the dead to bury him, revealing the funeral algorithms that constituted the funeral ritual, which can be observed in your testimonial below:

When I was young, this size (measuring height between 50 to 60 cm) the name they gave me was not that (Tsikbaktsamy), it was Aikdou, I lived in the hut with my parents, my brothers and my grandparents, we all lived together . When we were in the village, mothers and young children were in wahoro, men in mykyry and our dead in mytyk. The mytyk was not like today, square and with the dead lying in a box. Before mytyk was round (the shape is streaked on the floor). It was done on the side where the sun rises. We didn't bury our dead lying down like they do today. The dead were buried sitting, so the holes were round and not “square” like today, this happened after they returned from the priests who started to bury our lying dead, placed in a box and with a cross outside in the part of the head. Before when one of our people died, we measured from here downwards (pointing with the hand on the waist to the feet of the deceased, then a bachelor from the other clan dug the round hole, the size of the dead man's measurement. That was the bottom measurement and from the mouth of the hole. While he dug, we prepared the dead. We sat the dead with our hands on the knee, the knee close to the body, the head turned down, tied everything around with embira, put the net of the dead and broke the his weapons if he were a man and we put them in the hole. We would cry the dead and the widow for many days, the children and relatives would cut their hair, take off necklaces and other ornaments so that the spirit of the dead would not recognize them when he returned to another's village This is because Rikbaktsa is affectionate with his children and his wife and touches them and knows who they are, so that the dead man's house was burned and was built elsewhere to mislead, the other man's things were also burned. All this for why he doesn't want to stay here. Here the mytyk was man's last place. It started at the house, passed through mykyry and ended at mytyk. Now he could go back to the place he came from in the beginning, before he lived among us. Here as a man it ended. It's time for him to leave, but it's time to start again somewhere else, but not with this body (TESTIMONIAL FROM TSIKBAKTSAMY RIKBAKTA, Aldeia Segurança, 2019).

In the elder's account, two periods related to the modus operandi related to the burial of bodies, according to the Rikbaktsas, are explicit: the first linked to traditional making, the fruit of the people's original knowledge, before contact with non-indigenous people. In the initial procedure, the body was buried in the fetal position and in the other, after the return from the Utiariti boarding school, the product of the cultural interference of the white man, the bodies started to be buried in a “square and with the dead lying down, kept in a box.,” As reported by Tsikbaktsamy, (2019).

For Mediavilla:

The first to speak of funerary rituals performed by a species other than Homo sapiens were the brothers Jean and Amédée Bouyssonie, two Catholic priests who in 1908 discovered the remains of a 50,000-year-old Neanderthal in the La Chapelle-aux-Saints grave in France. According to the Bouyssonies, the fetal position of the body and the tools that accompanied it in the ditch where they found it indicated an intentional burial. Speculating, they suggested that the authors of that ritual had symbolic capacity and believed in a life after death (MEDIAVILLA, 2018, p. 1).

The Rikbaktsa, in their understanding of the organization of their cosmos, reveal to us, through Tsikbaktsamy's narrative, intrinsic aspects of the original behavior of the people by sharing ethnomathematical details as they did the cemetery and buried their dead, using their own bodies to demonstrate a reality lived in their time and in their living space, experienced with their peers, and transforming space into place of context (LOBATO, 2020).

The fetal position illustrated in figure 3, presented by the elder, brings to our knowledge this perception of the world, by signaling a specific way of being and doing, facts that singularize the Rikbaktsa, as the only indigenous group that until then describes the burial of their dead in that position, as shown in figure 3:

The way of being and doing Rikbaktsa, in their spaces of occurrences, configures these environments as places of meanings and symbols that are organized within a practice, which is based on a logic legitimized by the existing collective that experienced what happened and can detail why the subject was present in his place of experiences and coexistence, dynamizing his culture as it is the result of his work, the creative and recreational effort, the result of the transcendental sense of his relationships in which this culture of survival occurs as an acquisition system of human experience, as a critical and creative incorporation and not as a juxtaposition of donated reports or prescriptions (D'AMBROSIO, 2005; FREIRE, 2005, 2011; SILVA, 2013).

The testimony also signals other peculiarities of the Rikbaktsa people that articulate the layout of buildings with the life cycle of the Rikbaktsa man, by revealing that this Rikbakta man was inserted in a temporal cycle as he occupied these spaces, transforming them into places of meanings built by human experience (TUAN, 1983; JESUS, 2011; SILVA, 2013). Perceived in Tsikbaktsamy's narrative revealing the triad: beginning, middle and end of Rikbaktsa's existence according to the excerpt of his narrative: [...] the mytyk was man's last place. It started at the house, passed through mykyry and ended at mytyk.

The narrative shows what is perceived, the fruit of man's experience in space. According to Tuan, “man's perception of space depends on the quality of his senses and also on his mentality, on the mind's ability to extrapolate beyond the perceived data” (TUAN, 1983, p.3).

Tsikbaktsamy's narrative suggests that the three spaces are connected and closely linked in the formation of the Rikbakta man. It completes its circle of life by passing through the three places. Each represents a stage of action in the trajectory that is culturally defined, giving the being Rikbaktsa the ability to rise to transcendence. In that regard, D’Ambrosio states:

The integrality of surviving and transcending, which is essential and specific to the species homo sapiens, results from the individual processing of information captured (individually) from reality, and manifests itself as behaviors identified as belonging to a culture (D'AMBROSIO, 2016, p .74).

The theme of the meeting that dealt with the mytyk space expands to understand the new configuration that, from the organization of space to the way of burying the dead in this event, differ from what was narrated by Tsikbaktsamy of the contemporary model, according to other statements shared in the meeting.. In a dynamic that “goes from the mystical, present in the origin of knowledge, to the mystified, which is how that same knowledge presents itself when dressing in a system of codes” (D’AMBROSIO, 2016, p.69).

The funeral context space when burying their dead reaffirms behaviors that,

reflecting on the nature of knowledge, it is recognized that each individual acts in the present due to a mixture of ethos and acquiescence that complement each other to define behavior. Ethos and acquiescence synthesize the past [history] and the future [prospective] (D’AMBRÓSIO, 2016, p.75).

There arises, then, the need to verify other aspects related to this socio-educational space of the Rikbaktsa people, but this time, from the perspective of the current way, resignified from the reinterpretations of the world experienced by other Rikbaktsa, in an intercultural interaction, structured by dialogicity between yesterday and today, materialized in contemporary practices in the spaces of the villages that become places of meaning, by burying their dead.

With this intention, some aspects were addressed in the narratives of the elders: Ateata, Abui and Ariktsou, which we will share through Chart 1 to better visualize the information:

TABLE 1: Rikbaktsa funeral ritual configuration

| Who prepares the dead? | Person of the other clan and never of the same clan of the deceased |

| Who warns of death? | Person of the other clan and never of the same clan of the deceased |

| Who participates in the ritual? | All but the men must come together, painted, with ornaments and their weapons: bow, arrows, machete and club. The most experienced man in the other clan is expected to come forward. |

| How does the ritual take place? | They all lament and the male visitors arrive with cries of regret for the loss of their loved one (bursts). That present cry loudly in a strong lament. Everyone stands around the coffin to mourn. The men swing their bodies, gesturing sideways with a simple dance, without moving, with their weapons in their hands. |

| Who mourns the dead? | All the relatives, but the crying starts with the male relative of the same clan, repeats the lament three times, then the women continue |

| Crying man | Ota Bai - spoken by the man in the case of the father's death. |

| Crying woman who lost her husband | Kastê zo - spoken by the woman in the event of the death of her husband, father of her daughters. |

| What does the man cry? | Ota Bai, hum, Ota Bai hum, Ota Bai hum, hum, hum, hum. |

| What does the woman cry? | He, he, he, hum, Kastê zo, hum. He, he, he, hum, Kaokaha, hum... |

| Who digs the hole? | Single person from the other clan and never from the same clan as the deceased |

| Who stands beside the dead man? | The woman on the right near the dead man's head and all the children, brothers and first-degree relatives. |

| Dead position | With the head facing the side of the rising sun and the feet facing the west. |

| Arrival to attend the funeral | Always from the head of the deceased, on the right side, surrounds on the right and stops on the head. |

| Who serves chicha? | A single girl from the other clan who is not on the side of the dead, serves chicha to all the arriving visitors, but always has to start with whoever is in front. |

| Gripping time | Do people from the other clan hold close relatives and charge the living why they did not visit the deceased when he was alive? Why didn't you take care of him? Why didn't he make him happy? It is a time of collection and also of settling accounts. It can occur with the deceased's relatives or with other people from the other clan. |

| Burial | Everyone goes along with the lament and people from the other clan who carry the coffin. All the dead man's things are buried with him, mainly his weapons and his ornaments: headdress, armband, rattle and everything he used, including the net. |

| Burial place | Usually in the village where he lives, close to his family, in a place that is positioned towards the rising of the sun. |

| Closing of the ritual | The dead man's house is broken up, burned and built elsewhere. Some widows and children cut their hair, but this is very rare these days. |

Source: Elders from the villages involved in the research, 2019.

Currently the Rikbaktsa still keep the sun as a reference to define the location of the cemetery, as well as to bury the dead, maintaining the connection with the solar star by positioning the head of the dead towards the rising of the sun and the feet towards the setting, even if have reinterpreted the burial of their dead, no longer in the fetal position.

In the wake ritual we highlight relevant aspects which characterize the rite as one of the peculiarities of the Rikbaktsa who see in the event's procedures the factual exercise of the passage of a being who will no longer be here, however he will continue another journey, so he cannot stay and everyone needs to collaborate so that it goes to the other place of meanings and senses. In this perspective, the old woman declares, and the others agree with her statement that states:

This is the way of our people to care, to make the funeral, the lamentation of our deceased. And we have to do everything right so as not to fall over, nor let the spirit of the dead stay here. This is not good. He has to go to continue, whoever lives here after he dies, scares and nobody is safe, that's not good. You have to go to complete the other part (Statement by ARIKTSOU RIKBAKTATSA, Aldeia Beira Rio, 2019).

Ariktsou's narrative makes clear the fact that the life cycle of Rikbaktsa is completed by passing through the three spaces that constitute it as being legitimate for the group in which it is inserted, however it does not end here in this extension.

Elder Tsikbaktsamy previously and Elder Ariktsou claim that the mytyk space is not the end, but the beginning of a new stage in man's life. Both make it clear that life does not end with death, but that there is a continuity beyond this dimension that denotes “a cosmic reality, leading it to transcend space and time and existence itself, seeking explanations and historicity” (D ' AMBRÓSIO, 2016, p. 62).

The teachings contained in Chart 1, provide guidelines on how to proceed in the face of the fact that death is faced. Once again, the clans bring out their functions in the face of these circumstances, showing that the roles are already predetermined for the realization of the socio-cultural rules, in which each one linked to his group of origin carries out his assignment precisely (ATHILA, 2006).

In this sense, it is essential that each and every one knows precisely the specifics of his clan and the functions that are attributed to the subjects of the group, as well as it is essential that the new generations take ownership of these specificities so that the peculiarities of the group remain in evidence. cultural process that makes them unique.

However, this choice is always of the future generation that has the decision to preserve, even though the natural dynamics of life leads to other reinterpretations and reinterpretations of the culture itself, but that does not detract from the essence of being Rikbaktsa, because this is a natural their experiences in their original context.

Conclusion

The funeral ritual, as well as all the Rikbaktsa socio-educational spaces, have in their core particularities that typify their own, complex and organized by a singular logic orchestrated by a series of cultural elements.

The accumulation of knowledge resulting from original knowledge and traditional practices sedimented a series of mechanisms that produced skills and competences capable of explaining the complexity of the social organization of these people, whose material and spiritual needs are met as the collective manifests unity in the cultural essence of the subject Rikbaktsa.

The Rikbaktsa like all men tirelessly seek survival and transcendence. According to this indigenous group, what one does, how one lives and proceeds with others, here in this dimension is what determines where one goes after death and what form one will take in this transition to transcendence. In this case, death and otherness go together.

The act of burying the dead person's things with him comes from the perception that there is continuity after life and therefore, the belongings are burned so that the deceased is not among the living. As well as the uncertainty that the spirit of the dead person is gone, it justifies the fact that the relatives close to the dead person, cut their hair, remove the effects, burn the house and change places, so that the spirit of the dead does not recognize his relatives and want to stay with them.

Crying in mourning is directly linked to kinship with the dead and must be performed according to the place it occupies in the family and the clan it belongs to. Thus, the funeral is consolidated as a learning space for the future generation that, when participating in the event, highlights its cultural identity, guaranteeing its preservation, maintenance and enhancement.

REFERENCES

ACOSTA, A. O Bem Viver: uma oportunidade para imaginar outros mundos. Tradução de Tadeu Breda. São Paulo: Au¬tonomia Literária/Elefante, 2016. 264 p. [ Links ]

ARRUDA, R. S. V. Os Rikbaktsa: Mudança e Tradição. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências Sociais) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica (PUC) de São Paulo, 1992. [ Links ]

ATHILA, A. R. “Arriscando corpos.” Permeabilidade, alteridade e as formas de socialidade entre os Rikbaktsa (Macro-Jê) do sudoeste Amazônico. 2006. 509f. Tese (Doutorado em Sociologia e Antropologia). Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Sociais, da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

BARROS, A. T.; JUNQUEIRA, R. D. A elaboração do projeto de pesquisa. In: DUARTE, J.; BARROS, A. T. (org.). Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa em comunicação. São Paulo, Atlas, 2011 [ Links ]

CASTRO, E. V. Araweté: Os Deuses Canibais. 1986. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar/ANPOCS, 744 pp. [ Links ]

D’AMBROSIO, U. Etnomatemática: Elo entre as tradições e a modernidade. 5ª ed.; 2. Reimp. Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica Editora, 2017. [ Links ]

D’AMBROSIO, U. Educação para uma sociedade em transição. 3ª ed. São Paulo: Livraria da Física, 2016 [ Links ]

D’AMBROSIO, U. Sociedade, cultura, matemática e seu ensino. Revista Educação e Pesquisa, v. 31, n. 14, p.99-120, 2005. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. Educação como prática da liberdade. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2011. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. Pedagogia do Oprimido. Rio de Janeiro. Paz e terra, 42 eds. 2005. [ Links ]

GERDES, P. Etnomatemática - Cultura, Matemática, Educação: Colectânea de Textos 1979-1991. Reedição: Instituto Superior de Tecnologias e Gestão (ISTEG), Belo Horizonte, Boane, Moçambique, 2012. [ Links ]

HAHN, R. A. Categorias Rikbaktsa de Relações Sociais: uma análise epidemiológica. 1976. Tese (Doutorado em filosofia), 1976b. Tradução para o português de autor desconhecido e publicação autônoma. [ Links ]

JESUS, E. A. O lugar e o espaço na construção do ser kalunga. 2011. 218 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Matemática) - Instituto de Geociências e Ciências Exatas, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, 2011. [ Links ]

LOBATO, E. A. A etnomatemática como elo entre a pedagogia Rikbaktsa e o espaço escolar. 2020, 181 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ensino de Ciências e Matemática) - Faculdade de Ciências Exatas e Tecnologia, Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso, Barra do Bugres, 2020. [ Links ]

MEDIAVILLA, D. Quando os humanos começaram a realizar funerais? In: Jornal El País, 08 de abril de 2018. [ Links ]

MELIÀ, B. Educação indígena na escola. Cadernos Cedes, v. 19, n. 49, p.11-17, 1999. [ Links ]

SANTOS, B. P. A etnomatemática e suas possibilidades pedagógicas: algumas indicações. 2002. Tese (Mestrado - SANTOS (2002) - defendida em novembro de 2002, na Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

SILVA, A. A. Os artefatos e mentefatos nos ritos e cerimônias do Danhono: por dentro do Octógono Sociocultural A’uwẽ/Xavante. 2013. 346f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Estadual Paulista “Julho de Mesquita Filho”. Rio Claro - SP. [ Links ]

TUAN, Y. F. Espaço e lugar: a perspectiva da experiência. São Paulo: Difel, 1983. [ Links ]

VERGANI, T. Educação Etnomatemática: o que é? Ed. Flecha do Tempo. Natal, 2007. [ Links ]

Received: April 01, 2020; Accepted: October 01, 2020

texto en

texto en