Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensino em Re-Vista

versão On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.28 Uberlândia 2021 Epub 29-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v28a2021-38

ARTIGOS DE DEMANDA CONTÍNUA

Didactic sequence of formal oral genres in the final years of elementary school: the oral presentation in focus1

2Master of Arts. Municipal University of São Caetano do Sul. (USCS). São Caetano do Sul, São Paulo, Brazil. E-mail: karen.ringis@prof.uscs.edu.br

3Doctor of Education. Municipal University of São Caetano do Sul. (USCS). São Caetano do Sul, São Paulo, Brazil. E-mail: anaparicio@uol.com.br.

The objective of this research was to investigate the process of collaborative construction of a didactic sequence of oral exposition genre, in Portuguese language classes of 7th grade from a São Paulo state school. The carried-out research follows the qualitative approach, of a collaborative interventionist nature, considering a partnership between the researcher and the collaborating teacher. The theoretical basis of the research is based essentially on the contributions of studies related to the teaching of the mother language, of the Didactics of the Mother Language group at the University of Geneva. The results show that oral exposure is a genre that students do not master and, in view of that, didactic interventions are necessary to allow reflection on the relevance in associating linguistic, prosodic and kinetic resources with multisemiotic elements that interact and integrate in the development of oral presentations in formal public contexts.

KEYWORDS: Oral exposure; Formal oral genres; Following teaching

O objetivo deste trabalho foi investigar o processo de construção colaborativa de uma sequência didática do gênero exposição oral em aulas de Língua Portuguesa do 7º ano de uma escola estadual paulista. A investigação segue a abordagem qualitativa, de cunho colaborativo intervencionista, considerando a parceria entre a pesquisadora e a professora colaboradora. A fundamentação teórica da pesquisa está embasada, sobretudo, nas contribuições dos estudos sobre ensino da língua materna do grupo de Didática da Língua Materna da Universidade de Genebra. Os resultados evidenciam que a exposição oral é um gênero que os alunos não dominam e, em vista disso, são necessárias intervenções didáticas que permitam reflexão acerca da relevância em associar os recursos linguísticos, prosódicos e cinésicos aos elementos multissemióticos que interagem e se integralizam no desenvolvimento das exposições orais em contextos formais públicos.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Exposição oral; Gêneros orais formais; Sequência didática

El objetivo de esta investigación fue investigar el proceso de construcción colaborativa de una secuencia didáctica del género exposición oral en el aula de Lengua portuguesa a estudiantes de séptimo grado de una escuela estatal de São Paulo. La investigación realizada sigue el enfoque cualitativo, de carácter intervencionista colaborativo, considerando una asociación entre el investigador y el profesor colaborador. La base teórica de la investigación se basa, essencialmente, en las contribuciones de los estudios relacionados con la enseñanza de la lengua materna, del grupo Didáctica de la Lengua Materna en la Universidad de Ginebra. Los resultados muestran que la exposición oral es un género que los estudiantes no dominan y, en vista de eso, son necesarias intervenciones didácticas para permitir la reflexión sobre la relevancia en asociando recursos lingüísticos, prosódicos y cinéticos con elementos multisemióticos que interactúan e integran en el desarrollo de exposiciones orales en contextos públicos formales.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Exposición oral; Géneros orales formales; Secuencia didáctica

Introduction

One of the aspects that has drawn the attention of educators in the last few years, particularly Portuguese Language teachers, refers to issues related to the practice of orality, since many difficulties arise in more formal situations that require oral exposure.

Since the school is also a place to learn orality, it is necessary to make oral exposure a natural and even pleasurable activity for students, because one is required to be a good communicator in this century. So, how to teach students to articulate themselves orally, in a coherent way, in order to clearly convey their ideas?

It is worth mentioning that, in school environment, oral text genres, when they are worked on, almost always have the learning of writing as target. Reading aloud, for example, is the most frequent oral activity in the classroom, however, it is not an oral text, but, as stated by Dolz; Schneuwly; Haller (2004, p.167), an “oralized writing”. The authors defend this is a reflection of the overvaluation of writing to the detriment of orality not only at school, but also outside it.

Since the National Curriculum Parameters (PCN) - Portuguese Language, Final Years of Elementary Education, and more recently with the Common National Curriculum Base (BNCC), the guidelines established for teaching Portuguese Language point to the need to work with oral language, since students, as they are able to adapt or not to the different oral genre modalities, will be accepted or discriminated in various situations where they act as citizens in their social contexts.

In this sense, from specific oral production contexts, it is possible to develop in students the ability to express themselves orally according to the public oral circumstances. To this end, we argue that the Didactic Sequence device (hereinafter, DS), idealized by researchers in the field of Didactics of Mother Language at the University of Geneva (SCHNEUWLY; DOLZ, 2004), is a valuable instrument.

With this in mind, in this article, we discuss the results of a master’s research that investigated contributions of using the DS device of textual genres to develop students’ formal oral language skills, in Portuguese Language classes, in the final years of Elementary School. More specifically, we focus on the process of collaborative construction of DS by the Portuguese Language teacher and the researcher.

First, we present the theoretical framework that supported the research; next, we explain the methodological pathway; then, we discuss the results, based on data gathered from the development of DS.

The formal oral genres

All daily activities involving language, from the simplest, as a greeting, to the most complex, in any labor or science field, are supported by various discursive, oral or written genres. Consequently, all speeches, whether every day or formal, are structured around discourse genres, defined by Bakhtin (2006), as relatively stable forms of utterance, which are molded to certain communicational situations.

According to Marcuschi (2007, p.17), “orality and writing are practices and uses of the language with their own characteristics, but not sufficiently opposed”. Speech and writing are not a dichotomy, because writing does not consist of a representation of speech. It is a continuum. In relation to orality, in contexts of formal public communication, some issues influence not only oral expression but also writing, like: linguistic variation, communicational situation, context, subjectivity. This is clear when it is noticed that, even unconsciously, language users knowing they must behave, both in speech and writing, in a certain way relative to the counterpart they are interacting with. Such situations demand specific linguistic and social attitudes, which are defined based on criteria of formality or informality, and it is the role of the school to systematize them. As Marcuschi (2007, p.25) points out,

Formality or informality in writing and orality are not random, but adapt to social situations. This notion is of great importance to realize that both speech and writing have several stylistic achievements with varying degrees of formality. It is not right, therefore, to say that speech is informal and writing is formal.

Dolz and Scheneuwly (2004) state that formal oral genres assume different characteristics in their functioning and the degree of formality of each one is totally dependent on where the communication takes place. Examples of formal oral genres are: oral exposure, professional interview, debate, homily, lecture, among many others.

In this sense, Dolz, Scheneuwly and Haller (2004) sustain the introduction of orality as an object of teaching at school, and propose working with phenomena of oral textuality in line with real communication situations, considering different levels of language activity, thus making teaching more meaningful.

Oral genres at school

The National Curriculum Parameters (BRASIL, 1998) already recommended working with orality in the classroom, prioritizing more formal uses, including as an instrument to provide citizenship. According to the document, only at school will students have the possibility to learn the appropriate procedures for speaking and listening, in public contexts, if the school takes on the task of promoting it. More recently, BNCC (BRAZIL, 2017) takes up PCN guidelines and defines oral practice, reading/listening, production (writing and multisemiotics) and linguistic/semiotic analysis as the axes of Portuguese Language teaching.

However, clearly defining which oral language should be developed at school becomes a difficult task for the teacher. Sometimes, this poses several questions: “How to make the oral genres teachable? What oral genres to take as a reference for teaching? How to make it accessible to students? Which dimensions to choose to facilitate learning?” (SCHNEUWLY; DOLZ, 2004, p. 151).

Researchers from the Geneva group such as Schneuwly and Dolz (2004) and also many Brazilians such as Goulart (2005, 2017), Magalhães (2006), Guimarães; Souza (2018), among others, concerned with teaching language in a way that allows students to develop oral language skills and to make competent use of the language in the most diverse public formal communication situations, argue DS can be a valuable instrument.

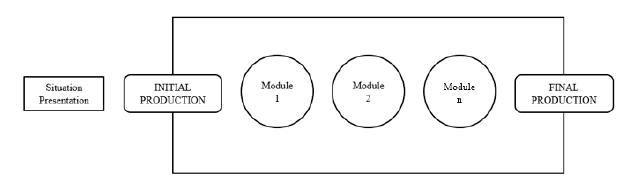

DS represents a set of activities planned and organized around a specific oral or written textual genre, with the purpose of developing language skills in students during the learning process (SCHNEUWLY; DOLZ, 2004).

In the first stage of the DS, called “presentation of the situation”, the teacher will describe in detail the production task, oral or written, that the students must perform. Then, in the “initial production”, they will elaborate the first activity, and will explain to themselves and the teacher the notions they have of this task. The teacher will diagnose the difficulties presented by the students, through a formative evaluation and the verified problems will be addressed in the activities of the “modules”. Therefore, the modules compose a sequence of workshops with clear objectives, aiming to work on the difficulties presented by the students in the first production. After, DS ends with the “final production”, when students will put into practice the knowledge acquired in modules (APARÍCIO; ANDRADE, 2016).

Thus, DS is considered an important tool for language teaching, by using different textual genres of social circulation, as it allows students to know, understand, master and use these genres in effective communicative situations. It also contributes for the teacher to follow more effectively the students’ language skills development. (DOLZ, GAGNON; DECÂNDIO, 2010).

With this in mind, in our research we adopted the DS procedure to work with the oral exposure genre in a 7th grade class of a state public school in the ABC Region of Greater São Paulo.

Research methodological procedures

This research followed the assumptions of a collaborative interventionist qualitative research, with intentionally planned interventions carried out collaboratively by the teacher and researcher in the classroom, with the purpose of further advancing the study subject and the professional development of teachers (Damiani, 2012) .

While designing the research, both researcher and collaborating teacher partnered to plan and develop the DS. The data for this stage were obtained through video recordings of interactions in the classroom: teacher-student, student-student, in addition to records in a field diary. Video recordings of classroom activities were made with the researcher’s cell phone, in order to capture speeches and movements of students during oral presentations, to avoid students from being intimidated by filming them. Finally, all material collected in this process was carefully analyzed in light of the research theoretical framework.

The research was developed in a public school in the state of São Paulo, located in the city of Ribeirão Pires, in the Greater ABC Region of São Paulo, over three months of the first semester of 2019, with the participation of a Portuguese Language teacher (collaborating teacher) and a 7th grade class of 32 students, aged 11 to 13 years old.

Construction of the didactic model of the oral exposure genre

It is important to point out that, to work with DS, Dolz and Schneuwly (2004) propose to create a didactic model providing a set of teachable dimensions of the genre, which will allow the teacher to carry out a survey of what can be taught in the genre and guide while designing the DS. The goal is to guide the teacher in practices of teaching the language and help to follow the development of students’ language skills.

According to Aparício and Andrade (2016), it is a complex task, which precedes and guides the construction of the DS, and requires the teacher to master the contents to be taught and carry out the screening of features of the genre to be worked on to their best, by adapting to learning situations and according to the students’ abilities. The authors emphasize the importance of the teacher to deepen in the studies of the genre to be worked on, for example, seeking: theoretical knowledge about it; social practices of reference, how to use of the gender, emerging from different actual circumstances of communication; typical contents of the genre and different ways of mobilizing them; style (linguistic features and their effects); students’ language skills to be developed; educational practices, teaching/learning situations experienced with the study of genres; official document guidelines, among others.

During our studies to make the didactic model of the genre, we found that “oral exposure” is a highly demanded genre in school activities, also called “seminars”, but barely worked in order to develop oral skills related to formal situations of speech, which require planning.

For Gomes-Santos (2012, p.15), “the presentation is a joint action, which implies the skills of negotiating roles, focused attention, taking and maintaining speech, among others”. According to this author, presenting by the speaker’s speech encompasses several semiosis and also combines several semiotic resources, among them: paralinguistic resources, such as voice quality, speech speed and rhythm, pause, intonation etc., and kinetic resources (gestures, facial and body expressions). In the oral presentation, these resources are complementary, that is, they maintain an interdependent relationship. It is the articulation of these resources that promotes the audience understanding of the presentation.

In oral exposure, facial expression, including the look, is also an important resource which supports the speaker’s utterance. Gesture is another very relevant resource in oral presentation, since it interacts with elements of the presentation environment (places, lighting, seating arrangements etc.), how the speakers stand in space and in relation to the audience (occupancy of places, personal space, distances, physical contact etc.), and also the increasingly technological accessories the speaker uses when presenting (slides in data show, internet videos, images etc.).

Based on Goulart (2005; 2017), we highlight some characteristics of the oral exposure genre:

- thematic content: involves broad topics, generally linked to teaching issues, anticipated in the curriculum, and on which the speakers should dive in to build knowledge to later explain to an audience;

- verbal style: relates to elements of linguistic surface linked to the dissertation kind, such as: verbs in the present tense or in the past perfect tense, declarative sentences, discursive articulators, first person speech, structuring markers, structural and temporal organizers, marks of deictics;

- socio-communicative function: aims to explain, inform or lead the audience to reflect on a certain thematic content produced during the work of reading and researching the topic under study;

- production conditions: it is a genre widely used in the school environment, especially in seminar presentation activities, or in academic events, such as in congresses, workshops, lectures, symposia, but it can also be found in other scopes of language use, depending on the socio-discursive environment where such gender is used and the activity through which it will be configured. The objective is to expand the knowledge on a certain topic and expose to the audience (public) what has been learned on that topic.

Another essential aspect in the construction of the didactic model of the genre is the elaboration of an analysis grid that provides clearer and more precise procedures for evaluating students’ productions. Its purpose is to verify the difficulties and previous knowledge of the students in order to carry out interventions, to subsequently plan the development of DS and also outline the teachable dimensions of the genre. With this in mind, based on Dolz, Gagnon and Decândio (2010), we elaborated the following Table.

Table 1: Analysis grid of the oral exposure genre

| Production context |

|---|

| a) Was the production site suitable for the presentation? |

| b) Did the 7th grade students achieve the objectives related to the presentation? |

| c) Did the speakers consider the target audience of the presentation (the public)? |

| d) Was the presentation produced in a form and language appropriate to the receivers? |

| Thematic content |

| a) How were the topics selected? |

| b) Is the information on the topic of the presentation relevant and appropriate to the target audience? |

| c) Is the form of organization of the information, in the oral presentation, adequate? Was there a hierarchy of ideas? |

| d) Does the presentation have adequate development of ideas? |

| e) Was there a decomposition and re-composition of the body of information in a procedural and continuous way? |

| f) The sources consulted for research were reliable and of different supports and languages, such as videos, newspaper texts, internet, interviews, graphics etc. |

| Compositional structure of the presentation |

| a) Was there an introduction to start the presentation? |

| b) Was the introduction to the topic designed to instigate the listener? |

| c) Has the progression of the thematic script been developed satisfactorily? |

| d) Was the recapitulation and synthesis phase properly presented? |

| e) Was there a closure to end the presentation? |

| f) Were varied resources used for the presentation (images, videos, posters, slides etc.)? |

| g) Was there autonomy for the speakers, in the presentation, and not just reading? |

| h) Was there anticipation of the listeners’ difficulties in understanding and the use of reformulation in the form of paraphrase or definition? |

| Textualization mechanisms (linguistic-discursive capabilities) |

| a) Did the students use formal conversational mechanisms appropriate to the genre? Which ones? What kind? |

| b) Did you notice, in the presentation, characteristics of the spoken text, such as flaws of speech (not adequate)? |

| c) Were appropriate linguistic forms used by speakers when addressing listeners? |

| d) Was cohesion present during the presentation? |

| e) How did the speakers interact with the audience? |

| Non-linguistic aspects |

| Paralinguistic means |

| a) Is the speaker’s voice audible? |

| b) Do speakers demonstrate pauses, breathing and utterance? |

| c) Is the presentation pace adequate? |

| Kinetic means |

| a) Do students demonstrate appropriate posture and movement when carrying out the presentation? |

| b) Do they use gestures, exchanges of looks and facial expressions together with speech, to establish interaction between speakers in the group and between speakers and listeners? |

| c) How do the speakers physically position themselves at the moment of presentation? |

| d) How do they alternate lines? |

Source: Prepared by the authors

So based on the body of information gathered from studies on the genre and its teaching, we started to develop the DS in classroom, as described below.

Development of the didactic sequence of the oral exposure genre

Following the DS scheme proposed by (SCHNEUWLY; DOLZ, 2004), we started by Presenting the situation. At this stage, we started with a round of conversation with the students, asking them about how we could work with orality in the classroom. They proposed various forms, such as theater, interview, debate, oral presentation, until, unanimously, it was agreed that we would work on the oral presentation. Then, there was a discussion to select the listeners, that is, who would be the auditorium, the target audience of the presentation. The students initially thought about introducing themselves to the teachers, coordination, then to the parents and, finally, also in consensus and always mediated by the teacher, they decided that the audience would be the 6th grade students. Soon after, they divided the class into 6 groups of 5-6 participants each, also organized by the students themselves.

The definition of the topics they would like to expose was also carried out by the class, in view of what they considered to be of interest to the target audience, the 6th grade students. Then, 6 topics were chosen, one per group, namely: Bullying, The use of technology, Racism, The importance of physical exercises, Recycling and Coexistence. Then, the teacher asked the groups to organize an oral presentation on the topic, for the following week, in the way that each group thought it would be. Intentionally, in order to follow the purposes of the DS, the students did not receive any instructions to prepare their presentations, that is, they worked mobilizing only their previous knowledge regarding what would be an oral presentation of the chosen topics, for the target audience established by them.

In the following week, as agreed, the groups presented the First production of the oral presentation. The location of the first production was the classroom itself, with classmates as an audience. Although it was not the real place of the proposed communicative situation, it was adequate for students to have a sense of the role of enunciators to a receiving audience. Everyone knew that this would be a first production and that, after analyzing this first presentation, they would carry out a sequence of activities to expand their knowledge about this oral genre and, then, they would carry out the final production presenting to the target audience, the 6th grade class.

In order to carry out the analysis of the first production, we considered the communicative situation proposed to the students and the analysis grid (Table 1). It is worth mentioning here that, for the analysis, we considered the data from two representative groups of the set. In the analysis of the first production of the two groups, we observed that students had many difficulties in organizing the oral presentation.

As for the presentation objectives, all students had difficulties to achieve them. For example: they read the content with a copy in hand; the topics were explored in a superficial way; there was little interaction between the group members; the students did not show any mastery of content. The groups performed without taking into account the audience. Many, when speaking, looked only at the floor. The exchanges of speech between colleagues occurred in a very informal way, full of slang and, on some occasions, bad language.

Regarding the thematic content, the selected information on the topics was very superficial, not showing the relevance to the listeners. They did not consult several sources to collect the information. The students did not bother to organize the ideas for the presentation and, thus, did not hierarchize the information, making it incomplete and loose, making it difficult for the audience to understand it. In addition, they inserted topics that were not completed, causing a flow of mismatched information. The groups presented content that was almost literally copied from just one source, with no evidence of work to organize a body of information.

In terms of the phases of the oral presentation, students did not introduce themselves, nor did they greet the audience, they announced the topic in a very timid way. In fact, they did not assume the role of speakers, nor did they create an interaction with their colleagues, who assumed the role of auditorium. The introduction to the topic was carried out, by every group, in a very simple way, for example: “The topic of our work is…”, that is, the presenters did not announce the topics in order to justify their relevance.

There was no logical progression of the presentation due to the fact that the groups did not elaborate a script. Most of the students read a copy in hand, without resuming topics that had already been mentioned; few have mastered the content and developed it with minimal autonomy and resourcefulness. Therefore, in the initial production, there was no stage in which the speaker summarizes the set of contents presented. Students only read and did not use visual aids, such as posters, slides, among others. The end of the presentation was not announced, and there was no thanks to the auditorium.

Regarding conversational mechanisms, students did not use, for example, more formal temporal organizers: “Now let’s talk about…”, “in this sense”, “then…”, “next…”, “first…”; of introducing examples: “for example”, “to exemplify…”; of reformulations: “that is”; “in other words”; “I mean…”.

Students used conversational markers characteristic of informal spoken texts, such as: “well”, “like”, “so”, “then”. In addition, expressions that indicate hesitation have been used repeatedly, for example: “yeah” and “right”, which are traces of the speech production process in informal everyday contexts. There was also no thematic cohesion, as students did not differentiate between main and secondary information, no sign to announce the conclusion was used, such as “therefore”, “anyway” etc.

Regarding the paralinguistic means, we identified that the students’ voice tone was practically inaudible and did not show confidence when exposing, on the contrary, they were quite uncomfortable. There was no monitoring of speeches and important details were not brought to the presentation, impairing the clarity and coherence of the content as a whole. The pace was fast, making it difficult for the audience to understand, since the lines were not spaced, as they were reading or had memorized the text, making the presentation of the content monotonous.

Finally, with regard to kinetic means, students did not assume an erect body posture, there was no gestural movement in order to emphasize what was being enunciated. A student even covered her face with her hands. Their look was almost never directed at the auditorium, that is, there was almost no interaction, compromising the socialization of information with the audience.

The students remained next to each other, leaning against the blackboard, practically immobile, and did not stand out when speaking. The exchange of speeches did not occur naturally. Some students needed to be warned that they would be the next to speak, which demonstrated that they were not engaged in the presentation, even going to disagreement when speaking.

In summary, the analysis of initial productions, as we predicted, showed that students have scarce knowledge about what is expected in the production of a formal oral genre, such as oral presentation. This result confirms our initial reflections that the school has not been working with these genres, but, on the other hand, they were essential to the elaboration of DS modules.

Starting from this result of the analysis of the students’ first production, we started the process of planning and developing the modules. Therefore, it was necessary to develop activities that dealt with problems at different levels and that helped students to reflect on the particularities of the production situation and also on the different characteristic aspects of the oral presentation genre.

In summary, the modules were composed of various activities and exercises, which allowed students to learn about important resources in the domain of the “oral presentation” genre, enabling advances relative to the difficulties noted in initial productions. Below we explain the activities worked on in each of the 6 modules that made up the DS.

In module 1, the groups worked on decomposing of the body of information. This happened as follows: in a previous class, each group had received 3 texts, related to the presentation’s topics, obtained from different sources, that is, magazine, newspaper and blog. At this stage, students, in their groups, initially worked on the skills related to reading the texts, and the collaborating teacher instructed the students to confront the texts they had in hand in order to make the selection of the information contained in the collection, seeking to identify more recurrent data, as well as pertinence or continence relationships between the information.

In module 2, groups, always assisted by the collaborating teacher, were instructed to work on recomposing the information that was decomposed from the collection. According to Gomes-Santos (2012, p.70), it is not enough to just identify and select the contents of the collection, it is necessary to give them a new treatment, “a configuration different from that which appears in collected texts”.

Therefore, the chosen contents were summarized. This is when students ask themselves: “What to do with the body of selected information? How to give them a more synthetic version and closer to what is actually intended to be exposed?” (GOMES-SANTOS, 2012, p. 70). So, re-composition is made on parts of the text with varying lengths and configured in the synthesis or reduction of these parts, it is also possible to perceive another action, which is adaptation, “by which a new portion of the text is condensed into a new syntactic structure” (GOMES-SANTOS, 2012, p.73).

Consequently, it is noted that within the activity of recomposing the contents, the task of summarizing is in fact quite relevant to the planning of the presentation, since it is the moment when the student will demonstrate how the collected information were interpreted and, in addition, it can be considered a device the student can use in many other school activities with text studying.

Students were very engaged and actively participated in proposed activity, becoming researchers in the body of information on the subject they would present, thus exercising skills related to reading and textual understanding.

The activities worked on in module 3 focused on aspects related to other semiosis, considering bodily, kinetic, paralinguistic and prosodic dimensions. Thus, students participated in a workshop and carried out activities related to disinhibition, posture correction when presenting themselves, imposing speech, unlocking shyness, among others.

Several times, as Gomes-Santos (2012) points out, what is intended to be explained as inhibition or shyness of many students who feel uncomfortable when speaking in public may be related to the complexity that speech assumes at the time of oral presentation, since the multisemiotic nature of the speaker’s utterance requires the combination of different capacities and skills.

In the activities of this module we had the participation of a professional in the area of communication, who engaged the class in his workshop. He started the process by calling a student volunteer at the front of the classroom and asked him to introduce himself naturally, without any intervention, in order to observe his level of oratory. Then he started a conversation with the group about people who are afraid to speak in public, pointing out that, most of the time, they have three characteristics: the first is not moving, the second is not facing the audience, the vision is back to the floor or any object in the room, and this is due to the insecurity of not being able to express an idea clearly. The third characteristic, which is also very common, is deficient gesticulation. Hands in pockets, holding an object or even squeezing it are signs of insecurity and discomfort with the situation.

After this discussion, together with the class, the performance of the students was analyzed. The next step was to guide and present tools to work on each of the characteristics mentioned above. The first intervention was relative to movement, where the student was asked to walk from side to side, with the torso slightly curved towards the audience, an immediate result was noted. Another also effective applied was asking the student to synchronize the speed of their steps to speech, leading speakers to follow the subject.

Then, visual activities were developed with the students, because in an oral presentation facing the audience is paramount. The “eye to eye” imparts credibility to the audience and, as seen in the first production, many students, when presenting, did not look at their listeners, even looking at the floor during their speech. The guidance for this moment was to hold a direct look at people in strategic points of the room. The criterion used in this choice was to find listeners who were receptive to the subject, agreeing with him by nodding his head “yes”, that is, people with a gentle face when following the subject.

Finally, gesticulation was worked on. Here the intervention was simple: just leave one arm relaxed, parallel to the torso. This way, the other arm is free to gesture, avoiding the meeting of the hands, squeezing them, or even carrying them in the pocket.

We found that this intervention was fundamental in the course of DS, as these tools do not act separately in oral production, that is, they have interdependent relationships and students do not absorb these techniques alone. It is required to train them so these resources become useful to the speaker.

In summary, we observed that there was real engagement by the class in this opportunity to experience new ways of presenting in public, expand the means of communication and overcome the conception of oral communication as an obstacle.

In module 4, the main objective was to work on reading genres that involve the perception of other semiosis, that is, they articulate verbal and non-verbal language, focusing on the visual aspects of texts, such as cartoons and infographics. At first, the groups were instructed by the collaborating teacher to search the Internet for materials referring to the topics they were developing in the DS.

This time the students themselves searched, selected and discussed the contents in the classroom. Always mediated by the collaborating teacher, students, in groups, analyzed, compared the materials, selected the most significant information, planned and produced content, and later started a debate in which all groups presented their research and were able to share ideas about the subjects. At that moment, the students held the debate, exchanging ideas and sharing information about the topics.

In module 5, the groups were involved in planning and elaborating a very significant part of the oral presentation: the script. According to Gomes-Santos (2012, p. 75), scripting aims to “regroup the set of selected and summarized information, placing it in a scheme that will serve as a guide for the presentation”. When preparing the presentation script, the speaker can proceed in two ways: hierarchize the information, establishing subordination relationships between main and secondary information, or distribute the information in the order in which they wish to present them to the audience.

Along the course of learning the presentation, according to Gomes-Santos (2012), the student will internalize increasingly efficient methods of formulating the presentation script and, consequently, having greater mastery on how to do this task. Therefore, we worked on the following script model with the students: 1) Topic; 2) Location; 3) Date/Duration; 4) Audience; 5) Purpose; 6) Subject; 7) Sequence: a) Presentation of the group, b) Why they chose the topic, c) Description of the subject; 8) Resources: slides, posters etc.; 9) Conclusion of the topic; 10) Interaction with the audience and 11) Farewell/thanks.

The first item of the script is the topic, that is, the subject to be presented by the group, which had already been decided, jointly, as described in the presentation of the communication situation. The second is the location, the presentations would take place in a room, close to the schoolyard, the date was previously defined and the presentations would last approximately 10 minutes per group. The public defined as an audience was the 6th grade students, as mentioned before. Then, the objective was resumed with the group, discussing what the intentions were on presenting a certain topic to the target audience.

On discussed subjects, it had already been agreed with the students that each group would work with three different texts, within each subject addressed, as mentioned above, by decomposing and recomposing the body of information.

As for the sequence, first, the order of presentation of the group’s components was defined. Then it was time to plan what to report to listeners about why they chose that specific topic, what messages they intended to convey to 6th graders. Finally, they proceeded to the description of the subject, that is, students planned and listed the items that would be presented to the audience, hierarchizing and ordering the information.

Following the script composition, always guided by the teacher, students discussed the resources they would use to complement the presentation: slides, posters, pamphlets, among others.

The next item in the script is the conclusion, at which point the group discussed the finalization of the presentation, by means of a synthesis to start the next stage, which is interaction with the audience. In this part, students simulated questions that could be asked to the audience and answers that could be given to the questions asked by the audience. Finally, the outcome of the presentation was reached, in which students were able to share and exercise formal resources of farewell and thanks for the attention received from the audience.

Thus, based on the work produced with all these items, each group developed its own script for the oral presentation. After this activity, the groups already demonstrated greater mastery of skills related to the use of verbal and non-verbal language for the production of oral presentation.

Finally, module 6 had as main objective to make the students present to their own class, as a rehearsal for the final production. The collaborating teacher mediated the groups’ rehearsal, she made some interventions during the presentations, guiding the students as to the speeches, if contents brought by the groups were relevant to presentation, if there was a sequence in contents, internal cohesion in groups, how the speech exchanges occurred, among others. So students could carry out the final production with greater mastery of the genre, suitable for the actual communicative situation proposed.

After completing the 6 modules, the groups worked up the final production. This is a time to check if they could demonstrate progress with the difficulties presented in the first production. According to Dolz, Noverraz and Schneuwly (2004, p.90), this is the “possibility of putting into practice the notions and instruments elaborated separately in the modules”.

In this last stage of the DS, the groups presented in a room with a TV and computer, making it possible to show the slides for the 6th grade students, i.e. the audience. As in the first production, the presentations were recorded and later transcribed and analyzed, showing that not only the representation of phonic materiality was considered significant, but also the performance of non-verbal semiosis, such as: body movements, looks, gestures, including the context in which the students’ presentations took place, related to social and language practices.

In the final production, after the didactic interventions in modules, it was clear that students’ performance had evolved. Actually, they incorporated the role of speaker, reevaluated their posture, their interaction with each other, articulating verbal, non-verbal and prosodic resources, including engaging the audience with questions.

Based on the same analysis grid (Table 1), it was possible to notice advances relative to the countless difficulties presented by the groups during the presentation of the first production. For example, the groups gave more importance to the audience, started to face them, questioned if there were doubts, attempted to reformulate more complex elements. Speech exchanges between colleagues took place in a more formal manner. About the language, students started to use more formal resources, avoiding slang, increased their tone of voice, speaking slowly, used slides and posters as visual resources.

Regarding the thematic content approach, the topics chosen by the students themselves could arise the interest of target audience, leading them to think on issues related to their daily lives and thus meeting the objectives of the oral presentation.

With the mobilization of materials from various sources, the groups were able to better structure the content exposed, by separating main and secondary ideas, and using examples. The information was articulated as a flowing chain of ideas and consequently they became comprehensible to the audience.

In terms of the compositional structure of the presentation, students assumed the role of speakers as they introduced themselves, saluted the audience and announced the topic of the presentation, creating interaction with 6th grade students, who assumed the role of audience. When the presentations started, the groups began to view the audience differently, that is, as their interlocutor audience. Markers of opening and introduction phases of the topic were used, for example: “Good morning, guys”; “We are going to start”; “These are the members of our group”; “Our research is about…”; “Now I’m going to talk about…”.

Thus, the introduction to the topic was carried out in order to capture the audience’s attention, justifying its relevance. The speakers asked the audience questions related to the topic, leading them to reflect on certain issues.

The groups planned a script and followed their steps during the presentation, presenting the ideas sequentially. Speakers bothered to summarize the set of contents exposed. The groups announced the end of the presentation, thanked the audience, and asked if there were any questions. Speakers anticipated the audience’s difficulties and reformulated the most complex parts, explaining or paraphrasing them. The students articulated verbal and non-verbal language, using visual aids, such as posters and slides. At last, all students started to master the content, developing it with autonomy and resourcefulness, no longer bearing copies on hand for reading. There was also a relationship between the speakers and the audience. They were concerned with the audience comprehension, opened space for questioning and resumed subjects already discussed.

Referring to the paralinguistic aspects, it was of note that students’ tone of voice became audible, as they started to present with improved confidence, demonstrating to feel much more comfortable and safer during the presentation. Prosodic resources were observed, speech monitoring and important particularities were brought to the presentation, such as pauses and variation in the tone of voice, giving clarity and coherence to the content as a whole. The more articulated presentation normalized the rhythm of speeches, since they were more spaced, which contributed to a much more natural and progressive content on the presentation.

The kinetic means became present. Students were attentive to body posture, adopted arm and head movements in order to emphasize what was being enunciated, directed the look to the audience, that is, groups were concerned with creating interaction with listeners. Stage control was observed as the students stood side by side, but they moved and stood out at the time of their speeches.

The exchanges and resumes of speeches took place in an articulated manner, as the students dominated the content as a whole and knew the precise moment to make their statement. There was also complementarity between the statements, promoting the construction of text meaning.

In short, considering the results of the analysis of the final production, we verify that there was an advance in the students’ language abilities in the production of a formal oral genre - the oral exposition. Thus, it is clear that the DS device really contributed to such advances.

Conclusion

As mentioned in the Introduction, in this paper, our intention was to point out contributions from using the DS device of textual genres to the development of students’ formal oral language skills in the final years of elementary school.

By describing the collaborative design process between researcher teacher and collaborative teacher, we seek to highlight the students’ progress in the final production of oral presentation, compared to the first production, which helped us to diagnose what the students needed to learn.

Initially, it was possible to perceive students’ difficulties with formal oral textual genres, due to the fact that it is something new for them or because they did not have the opportunity to be protagonists of the teaching and learning process, with autonomy to select texts about the topics to be addressed, to organize and present information to a real audience, in an authentic, real communicative situation.

The analysis of both productions, before and after the realization of the modules showed that, in the process of designing the DS, students are considered protagonists of the teaching and learning process; the engagement of students in real production contexts enables them to learn better; the construction of pedagogical knowledge of the content by teachers, in/about classroom practice, contributes to their professional development and gives more authorship to the teaching work.

Finally, we conclude that considering formal oral genres as a goal of teaching Portuguese Language, in Basic Education, in addition to valuing the oral language, makes classes more significant, expands students’ oral language skills, while preparing them to participate effectively in various communication scopes in our society.

REFERENCES

APARÍCIO, A. S. M. e ANDRADE, M. F. R. de A construção colaborativa de sequências didáticas de gêneros textuais: uma estratégia inovadora de formação docente. In: Marli André (org.) Práticas Inovadoras na Formação de Professores, Campinas. SP: Papirus, 2016, p.71. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, M. Os gêneros do discurso. Estética da criação verbal. v. 4, p. 261-306, 2006. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Fundamental. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais: Língua Portuguesa/Secretaria de Educação Fundamental. Brasília: Ministério da Educação, 1998. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Básica. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília: Ministério da Educação,2017. [ Links ]

DAMIANI, M. F. Sobre pesquisas do tipo intervenção. In: XVI Encontro Nacional de Didática e Prática de Ensino, 2012, Campinas. Anais do XVI Encontro Nacional de Didática e Prática de Ensino. Campinas: UNICAMP, 2012. p. 1-9. [ Links ]

DOLZ, J.; NOVERRAZ, M.; SCHNEUWLY, B. Sequências didáticas para o oral e a escrita: apresentação de um procedimento. In: SCHNEUWLY, B.; DOLZ, J. Gêneros orais e escritos na escola. In: Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2004. [ Links ]

DOLZ, J.; SCHNEUWLY, B.; HALLER, S. O oral como texto: como construir um objeto de ensino. In: SCHNEUWLY,B.; DOLZ, J. Gêneros orais e escritos na escola. In: Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2004, p.125-155. [ Links ]

DOLZ, J.; GAGNON, R.; DECÂNDIO, F. Produção escrita e dificuldades de aprendizagem. Campinas. SP: Mercado de Letras, 2010. [ Links ]

GOMES-SANTOS, S. N. A exposição oral: nos anos iniciais do ensino fundamental. São Paulo: Cortez, 2012. [ Links ]

GOULART, C. As práticas orais na escola: o seminário como objeto de ensino. 2005. 210f. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP) - Campinas, 2005. [ Links ]

GOULART, C. A caracterização do gênero exposição oral no contexto das práticas de linguagem na escola. Olhares & Trilhas. Uberlândia, vol. 19, n. 2, jul./dez. 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14393/OT2017v19.n.2.230-258. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, A. M. de M.; SOUZA, J. de. Pela necessidade de trabalhar a oralidade na sala de aula. Diálogo das Letras, Pau dos Ferros, v. 7, n. 2, p. 81 - 100, maio/ago. 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22297/dl.v7i2.3207. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, T. G. Oralidade na sala de aula: alguém “fala” sobre isso? Revista Instrumento: Revista de Estudo e Pesquisa em Educação. EDUFJF, v. 7/8, 2005/2006. [ Links ]

MARCUSCHI, L.A.. Da fala para a escrita: atividades de retextualização. São Paulo: Cortez, 2007. [ Links ]

SCHNEUWLY,B; DOLZ, J. Gêneros orais e escritos na escola. Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras, 2004. [ Links ]

Received: February 03, 2020; Accepted: October 01, 2020

texto em

texto em