Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensino em Re-Vista

versão On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.28 Uberlândia 2021 Epub 29-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v28a2021-41

ARTIGOS DE DEMANDA CONTÍNUA

Subsidies for the Construction of a Primer on the need to include People with Dwarfism1

2Master in Diversity and Inclusion from Universidade Federal Fluminense Universit, Niterói, RJ, Brazil. E-mail: faria.andreamoreira@gmail.com.

3PhD in Ecology and Natural Resources from the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, SP, Brazil. E-mail: rejane_lima@id.uff.br.

4PhD in Ecology and Natural Resources from the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, SP, Brazil. E-mail: rejane_lima@id.uff.br.

Dwarfism is a genetic condition that involves abnormal skeletal growth, causing short stature compared to the average population. Our objective was to raise awareness and contextualize the need for inclusion of people with dwarfism, by applying a questionnaire with 31 questions that would serve as a basis to produce a booklet on the proposed theme. The questionnaire was sent through Google Forms to 400 people, including CMPDI members, college classmates, and the United Dwarves group. The 76 responses obtained revealed that there is superficial knowledge on the subject, precariousness in relation to accessibility, in addition to humiliation and prejudice. Thus, to reverse this scenario, was created: “Dwarfism in Debate: Pedagogical Primer for Social Inclusion” which will be launched by the Brazilian Association of Diversity and Inclusion.

KEYWORDS: Accessibility; Human Rights; Inclusion; Preconception

O nanismo é uma condição genética que envolve um crescimento esquelético anormal, desencadeando numa estatura inferior se comparada à média populacional. O presente estudo teve como objetivo conscientizar e contextualizar sobre a necessidade de inclusão da pessoa com nanismo através da aplicação de um questionário com 31 perguntas que serviu como base para a construção de uma cartilha sobre o tema proposto. O questionário foi enviado através do Google Forms para 400 pessoas, incluindo componentes do CMPDI, colegas da faculdade e o grupo Anões Unidos. As 76 respostas obtidas (validação e teste) revelaram que há conhecimento superficial sobre o tema, precariedade em relação à acessibilidade, além de humilhação e preconceito. Desse modo, visando reverter esse cenário criou-se: “Nanismo em Debate: Cartilha Pedagógica para a Inclusão Social” que será divulgada através da Associação Brasileira de Diversidade e Inclusão em breve.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Acessibilidade; Direitos Humanos; Inclusão; Preconceito

El enanismo es una condición genética que implica un crecimiento esquelético anormal, lo que desencadena una estatura más baja en comparación con el promedio de la población. Lo nuestro objetivo crear conciencia y contextualizar la necesidad de incluir a las personas con enanismo a través de la aplicación de un cuestionario con 31 preguntas que sirvieron de base para construir un folleto sobre el tema propuesto. El cuestionario se envió a través de formularios de Google a 400 personas, incluidos miembros del CMPDI, universitarios y el grupo Anões Unidos. Las 76 respuestas obtenidas (validación y test) revelaron que existe un conocimiento superficial sobre el tema, precariedad en relación con la accesibilidad, además de humillación y prejuicio. Por lo tanto, para revertir este escenario, se creó lo siguiente: “Enanismo en el debate: Manual pedagógico para la inclusión social” que se difundirá a través de la Asociación Brasileña de Diversidad e Inclusión.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Accesibilidad; Derechos Humanos; Inclusión; Prejuicio

Introduction

We are here tracing an excerpt from the master’s dissertation in Diversity and Inclusion at the Biology Institute of the Federal Fluminense University that directly reflects the maturity and personal and professional evolution of the first researcher who authored the present study. The researcher in question has achondroplasty dwarfism, a genetic syndrome that affects around 250 thousand people worldwide and may be of hereditary origin or due to a genetic mutation (PRADO et al., 2004; ADELSON, 2005; WANG et al., 2013; ORNITZA and MARIE, 2019; FARIA, 2020).

For years, this person with dwarfism showed resistance to talk about the topic. The process of acceptance of this condition was delayed, understandable when the history of prejudice and stigmatization experienced by those with physical disabilities, especially dwarfism, is considered (MOURA, 2015). Throughout her life, she experienced episodes of bullying, that is, social discrimination and intentional rejection (PEARCE and THOMPSON, 1998; LOPES, 2013; LOPES NETO, 2005).

Thus, it was planned to prepare a document that would serve as a didactic tool for scientific dissemination to raise awareness among the Brazilian population about the theme of dwarfism. This topic still commands little space for discussion in universities and research centers and is still the target of ignorance resulting in prejudices, taboos and relationship difficulties related to this physical condition (FARIA et al., 2019; FARIA, 2020; FARIA and LIMA, 2020a, b; FARIA, MARIANI and LIMA, 2020).

The recurring characteristics of this type of approach are the focus on the interpretation of the objective; relevance as to the context of the study and the approximation of the researcher in relation to the phenomenon to be studied (SILVEIRA and CÓRDOVA, 2009).

What is Dwarfism?

Stunting in humans can be defined as a pathological condition or genetic trait that results in short stature which is 20% smaller compared to the average height of the population. Thus, in adult humans, a person with dwarfism is considered to have a height of less than 1.40m for men and less than 1.35m for women. This condition results from a metabolic-hormonal disorder or genetic alteration (mutation) characterized by difficulty and/or disharmony of the bone growth process (PRADO et al., 2004; ADELSON, 2005; WANG et al., 2013; ORNITZA and MARIE, 2019). In addition, malnutrition, lack of vitamin B and anemia are also factoring that can trigger this physical condition (HABERER, 2010).

Two major publications on pathological conditions in hominid fossils found in the Romito cave (in Italian: Grotta del Romito) revealed cases of chondrodystrophic dwarfism in the late Italian Upper Paleolithic (also called the Upper Stone Age - between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago). The skeletons of two young men found in excavations carried out in the Lao Valley of Pollino National Park, in Calabria, in southern Italy. The specimens named Romito 1 and Romito 2, provide the first known case of dwarfism in the human skeletal record approximately 10,000 years ago (FRAYER et al., 1987; 1988).

So far, at least 434 types of dwarfism have been described, which are divided into two major groups: (i) the proportional group, which is marked by hormonal changes; (ii) rhizomatic group, resulting from genetic mutations (CERVAN et al., 2008). The most common type of dwarfism is skeletal dysplasia called achondroplasia. In humans, it is caused by a genetic mutation that occurs in the short arm of chromosome four (an autosomal), involving the gene that is responsible for the synthesis of the Fibroblast Growth Factor Type 3 receptor (FGFR3).

This mutation involves the replacement of the amino acid by a glycine amino acid link an arginine in the domain of the protein that makes up this receptor (ROUSSEAU, BONAVENTURE, LEGEAI, 1994; WYNN et al., 2007; CERVAN et al., 2008). However, although achondroplasia is a rare characteristic worldwide, it has an expression rate of 100%, with between 80-90% of cases due to mutation in the FGFR3 gene and 10-20% are of hereditary origin (WANG et al., 2013; ORNITZA and MARIE, 2019).

Currently, there are about 250,000 people in the world expressing achondroplasia. Technically, this is characterized as a disorder that affects endochondral ossification, causing limb shortening, due to insufficient growth of long bones, and can cause a reduction in life expectancy (WYNN et al., 2007; CERVAN et al., 2008; FARIA, 2020). There is evidence that one in every 25,000 children who are born, or 0.004%, has such a physiological change due to a mutation that alters the functioning of the FGFR3 receptors.

Physical Disability and Rights

In Brazil, the condition of a person with dwarfism is recognized as a physical disability according to art. 4 of Decree 3,298/1999 (BRASIL, 1999). Several factors, including cultural and social issues throughout history, have determined classifications and treatments for people with physical disabilities (LOPES et al., 2008). Several historical records show that between the years 1200 to 1940 people with physical disabilities were subjected to various procedures that, in many cases, led to exclusion and consensual death (Table 1).

However, there are indications that people with dwarfism were positively evaluated in Ancient Egypt (from 3200 BC to 32 BC) since they resembled Satyr. The Satyr was a Greek deity who inhabited fields and forests and had horns and legs of a goat, being half-human and half-goat creatures that symbolized the free paths of nature, equivalent to the Faun or Silvano of Roman mythology (DASEN, 1988).

Table 1 Classification and treatments for people with physical disabilities between the 13th and mid-20th centuries.

| Periods | Social Perspectives | Treatments adopted |

|---|---|---|

| 1200 to 1799 | They were possessed by demons. | They were tortured, burned alive. |

| 1800 to 1929 | They were inferior beings with a genetic defect. | They were a freak. |

| 1930 to 1940 | They were beings with a genetic defect. | They were sterilized, exterminated. |

Source: Modified from Lopes, 2013.

In the 1960s, the movement for the vindication of rights, the fight against oppression and the role of people said to be those with special needs, resulted in the Social Model of Disability, as opposed to the merely biological model (PRADO et al., 2004; DINIZ, 2012).

In Brazil, the reality that people with dwarfism still face is still far from ideal for their full inclusion, as these individuals, even today, deal with attitudes of social discrimination, lack of accessible architecture and the absence of adequate services to their needs. These, together with frequent ignorance of their biological characteristics, deprive them of fundamental freedom and autonomy (ADELSON, 2005; PRITCHARD, 2017; SANTIAGO, 2018, FARIA, 2020; FARIA et al., 2020), rights that are guaranteed in international treaties and specific laws for the disabled public (BRASIL, 2001; 2004; 2009; 2017).

The International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (BRASIL, 1996; 2009; CAIADO, 2009) guarantees rights such as life (art. 10); equality before the law (art. 12); life and inclusion in the community (art. 19); education (art. 24); health (art. 25); work and employment (art. 27), among others. Such measures aim to combat discrimination, prejudice, and other harmful practices towards people with disabilities. Through Legislative Decree 198, of June 13, 2001, this Convention was approved by the National Congress and entered into force in Brazil (CAIADO, 2009). For this convention, disability can be a permanent or transitory restriction, of a physical, mental or sensory nature, which limits the ability to perform essential activities of daily living, caused or aggravated by the economic or social environment (DIÁRIO DO SENADO FEDERAL, 2001).

Materials and methods

The research is exploratory, as it aims to bring greater familiarity to the problem studied. The developed research has a qualitative methodological approach, in which, as described by Gerhardt and Silveira (2009), the concern of the study is to deepen the understanding and explanation of social relations, placing the researcher in a position of subject and object of his study (SILVEIRA and CÓRDOVA, 2009). According to Gil (2008, p. 27), the aim is “to develop, clarify and modify concepts and ideas, with a view to formulating more precise problems or researchable hypotheses for further studies.”

As for the methodological resources, a questionnaire with 31 questions was used, two of which were closed, 13 semi-open and 16 open, which was constructed through the free online Google Forms platform, aiming to verify and interpret the understanding of the volunteer participants (with and without dwarfism) on the proposed theme.

The questionnaire was applied in two stages. The first was for validation and the second for complementary data collection. In the validation phase, responses were obtained from 27 participants out of the 60 participants consulted. After validation, textual adjustments were made to three questions to facilitate interpretation and obtain answers. The second questionnaire was applied to groups of people other than the first participants when 49 responses were obtained from the 340 participants consulted.

People with dwarfism were contacted through the group “Somos todos Gigantes” (https://somostodosgigantes.com.br/), located on a social network. As for people with no expression of dwarfism, the invitation to answer the questionnaire was made via e-mail and social networks of the researchers. The survey was briefly presented to all participants and the link to access the form was made available online. From the beginning, the participants were aware that they would not be identified, preserving the anonymity of each one. As the questionnaire was also sent to people with dwarfism, there were questions that sought to know aspects about their experience. People who did not have this condition were obviously exempt from answering such questions. The answers were analyzed by exploratory statistics through graphics produced using Excel. The open questions were evaluated through the Word Art program (https://wordart.com/) that generates a word cloud revealing the most frequent responses.

Results

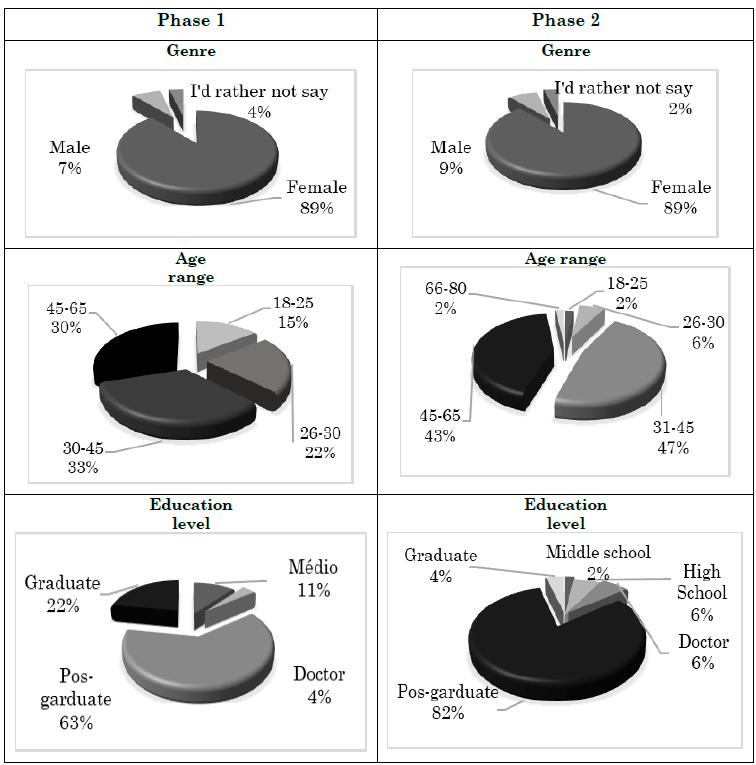

In total, 76 people answered the questionnaires applied (n = 27, Phase 1 for validation: n = 49, Phase 2), and in the latter, only five of these people with stunting participated in the survey, participating in Phase 2. It was found that most of the public that participated in the research was female (89% for both the first (n = 27) and the second (n = 49) Phases (Figure 1).

Most people belonged to the age group between 30 and 65 years, constituting (66% of Phase 1 and 90% of Phase 2), are graduate (63% of Phase 1 and 82% of Phase 2), and are educational workers (63% of Phase 1 and 82% of Phase 2 (Figure 1).

The question "Have you ever experienced situations of discrimination due to disability?" it was not well interpreted, as it was not clear that the deficiency referred to was stunting. Of these, although only five of the participants were people with dwarfism, most replied that they had suffered discrimination, especially in Phase 2 (Table 1). Most of the answers obtained for Phase 2 (63.3%, n = 49) rated the life of people with dwarfism in Brazil as “very difficult”. The lack of inclusion was also an extremely pointed factor.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

FIGURE 1: Responses of the participants of the questionnaires that were applied in October and November 2018 in two phases: first questionnaire (Phase 1: n = 27, for validation) and second questionnaire (Phase 2: n = 49).

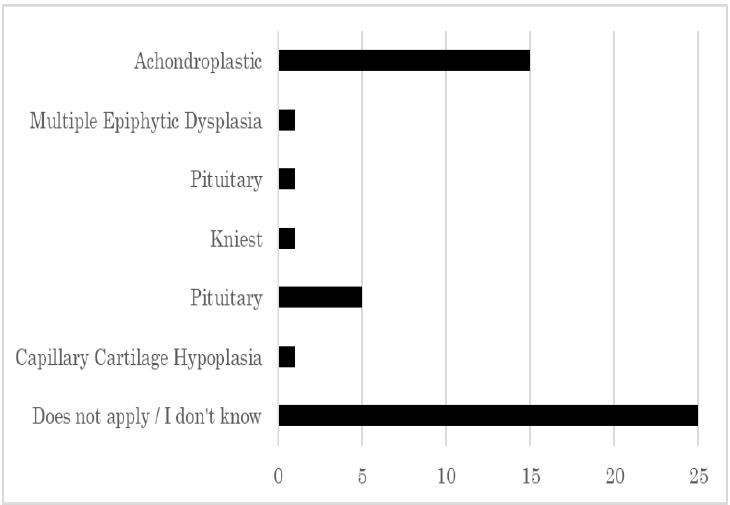

For the question "What kind of dwarfism do you / your family member / friend have?" that was applied in Phase 2, the majority (51.0%) was unaware of such classification (Figure 2 and Table 1). The type of achondroplasty dwarfism was only mentioned by 30.6% participants.

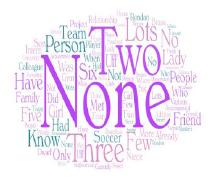

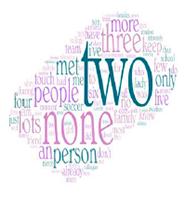

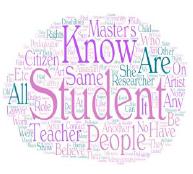

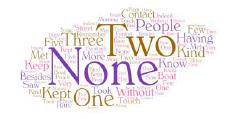

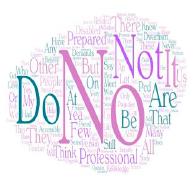

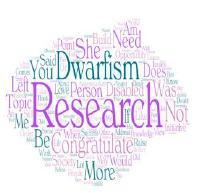

Table 1: Presentation of the word clouds formed with the answers resulting from the application of the questionnaires (Phase 1 - validation; Phase 2. The word clouds obtained with the validation of the questionnaire (n = 27, Phase 1) and the application of the questionnaire (n = 49, Phase 2) are presented. For common or similar questions between the two questionnaires the answers were combined - Phase 1 (n = 27) + Phase 2 (n = 49) totaling 76 responses.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 2: Number of answers to the question: "What type of stunting do you / your family member / friend have?" (n = 47).

All the participants (100%, n = 27; 73.5%, n = 49) did not belong to any group on social networks and / or are members of some association of people with dwarfism and all do not consider the statement that "People with dwarfism have social inclusion as a reality in life" (Table 1).

The comments were that there is still a lack of understanding, adaptation of physical environments, clothing and adequate infrastructure, warnings of inequality and disrespect for people with dwarfism, victims of physical and social barriers. Among the 79 people who answered, only one of them studied at a special school and, therefore, there was no description of possible difficulties experienced (Table 1).

Approximately 85% of participants (n= 79) stated that access by people with dwarfism to universities does not occur in a fair and equal manner and the majority (66.7%, n= 27; 67.3%, n= 49) believed that the labor market is not ready to receive professionals with dwarfism (Table 1). Finally, the great majority answered that they felt good or happy when answering the questionnaires and assigned a score of ten (10.0) for the relevance of the study (Table 1).

The question about the conditions of accessibility in the workplace indicated that many of these spaces, despite the legal obligation, are not prepared to receive and employ professionals with disabilities such as stunting. Participants consider this accessibility to be poor or bad in 51.7% (n= 27) and in 85.7% in (n= 49) (Figure 3). Research participants reported absence of architectural adaptations, lack of adequate furniture, inaccessible bathrooms, elevators with inaccessible buttons, ramp, and type of floor.

For most participants (88.9% of n= 27 / 63.3% of n= 49), there was no understanding on the part of society about who are people with dwarfism and what their specific needs are (Table 1). In addition, in both versions of the questionnaire, most survey participants (63%, from n= 27 / 57.1% to n= 49) considered that there is no representation of people with dwarfism in the Brazilian media. Most participants (85.2% of n= 27 / 67.5% of n= 49) stated that there is not enough information in the Brazilian literature and research on stunting (Table 1).

A large part of the participants believed that respect for the laws protecting the rights of people with dwarfism were not satisfactory and duly fulfilled, that the Brazilian government does not develop public policies for the inclusion of people with dwarfism and consider that professionals, such as teachers, doctors, lawyers are not prepared to meet the demands of people with dwarfism.

We found that fifty-four participants did not answer the question “Do you want to add something more to this survey? Feel free! ”. However, those who responded (n= 25) asked relevant questions and opinions and took the opportunity to express their doubts and positive considerations regarding the research carried out (Table 2).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 3: Quantitative answers to the question "How would you rate the accessibility conditions of your workplace?" (n= 27, black bar; n= 49, gray bar).

Based on the results obtained with the questionnaire (Phase 1 + Phase 2) and on the available bibliographic information, a booklet was created: “Dwarfism in Debate: Pedagogical Booklet for Social Inclusion” containing 26 pages dealing with the concept, types, laws, and rights people with dwarfism.

Table 2: Twenty-five answers obtained for the question “Do you want to add something more to this research? Feel free!”.

| Phase 1 (n= 27) |

|---|

| 1. "Some questions left me in doubt." |

| 2. "Thank you for the opportunity to build knowledge and reflect other points of view." |

| 3. "I believe that with social networks, it is possible to achieve the necessary changes more quickly and effectively." |

| 4. "Brazil still needs many resources to deal with disability in general." |

| 5. “When I was eight, I saw the first person with dwarfism in my life in the elevator. I asked my aunt if she was a child or an adult, she did not respond, apologized and when we left, she said she was ashamed of me. ” |

| 6. “I am a master's researcher on people with disabilities and tourism. Any research that can contribute to inclusion and accessibility has my support! ” |

| 7. “This topic needs to be researched continuously.” |

| 8. “I just wanted to congratulate the initiative, because as I said, information is everything!” |

| 9. “The initiative to research the universe of people with dwarfism is very important, to investigate their reality and point out ways, with the endorsement of academic research with a scientific nature.” |

| 10. “Honestly, I am part of a prejudiced and excluded society and I confess that I need more knowledge in relation to the topic. I also need to do more research.” |

| 11. "A country that does not respect, does not create job opportunities, does not build fair laws for people with physical disabilities." |

| 12. “I wish you much success and success! Gratitude for the researcher's generosity. Congratulations! Extremely relevant topic.” |

| 13. “Congratulations on the research. All luck on the walk. Kisses!" |

| Phase 2 (n= 49) |

| 1. “I congratulate you on the proposal and wish you success for the benefit of all people with dwarfism and the advancement of inclusion in our society.” |

| 2. “The fight is for everyone who believes in a more equal education, instructing people without disabilities to respect and provide a more inclusive environment for all. together we can think about it, without division, just with the awareness that we all have the same rights, and we need to work so that everyone can exercise them.” |

| 3. “Congratulations on the theme.” |

| 5. "Research success." |

| 5. “Always be the representation we need! Good luck!" |

| 6. "Some questions are very similar and thus become repetitive." |

| 7. “I think it is great that this subject will be researched and studied within a university with the aim of expanding knowledge so that segregation decreases, and inclusion really happens.” |

| 8. "May it be a research that comes to address issues of dwarfism in order to raise awareness in society." |

| 9. “Congratulations on the job!” |

| 10. "I would like to know more about Dwarfism and its causes." |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The booklet contains the following items: (1) What is Dwarfism? (2) Main types and phenotypic characteristics of dwarfism; (3) Important Health Considerations for People with Dwarfism; (4) Rights of People with Dwarfism: (5) Relevant Legislation; (6) Stunting, Education, and Inclusion; (7) Sources of Information on Dwarfism; (8) Materials consulted (Table 3).

The booklet was produced in an e-book (“Dwarfism in debate: pedagogical booklet for social inclusion”, FARIA; LIMA, 2020a) was the basis for the production of a spoken book (“Talking about Dwarfism and Social Inclusion”, FARIA; LIMA, 2020b), to assist people with visual impairments (blind or low vision). Finally, the booklet was translated into Brazilian Sign Language in video format, containing the interpretation of the text (“Dwarfism in Libras”, FARIA; VASCONCELOS; LIMA, 2020).

Table 3 Content of the first page of the master's product in question: “Dwarfism in Debate: Pedagogical Primer for Social Inclusion”.

| Presentation - This material is the product of a master's degree elaborated by Faria (2020), master by the Professional Master Course in Diversity and Inclusion (www.cmpdi.uff.br) at Federal Fluminense University, supervised by Professor Dr. N.R.W. Lima. We intend, through this booklet, a didactic tool for scientific dissemination, to raise the awareness of the Brazilian population about the theme dwarfism, still subject to much prejudice, taboo, ignorance, and exclusion, and with little space for discussion in universities and research centers. To this end, we will address issues such as conceptual definition of stunting; brief explanation of what causes this condition; laws relevant to that audience; accessibilities necessary for their inclusion in the country. |

| Justification - The scarcity of informative content on the subject led us to create this booklet, to minimize the attitudinal barriers faced by citizens with dwarfism. In the current Brazilian context, there is already a discussion about the importance of including people with disabilities, however, many times, those who have dwarfism are omitted and still face the exclusion scenario. |

| Objective - Provides, through a didactic and accessible language and free of charge, (in) formative content about dwarfism and its specificities, aiming to make society aware of the need for inclusion and active participation of people with dwarfism. |

Source: FARIA; LIMA, 2020a.

Discussion

Regarding the path to the concrete inclusion of people with dwarfism, most participants in the research carried out highlighted the importance of information, requesting that there be a wide dissemination by the media that addressed the real need to comply with the inclusion laws and the creation of new public policies, as well as accessibility in public and private environments for people with physical disabilities (BRASIL, 2001; 2004; 2009; 2017).

It is important to include people with physical disabilities in the formal labor market. Opinion research involving disabled people revealed that:

“1) if it were not a legal obligation, it would be difficult for people with disabilities to be hired; 2) making the presence of people with disabilities an obligation reduces prejudices towards this group, giving them the chance to show their skills and abilities; and 3) despite the legal apparatus and changes in behavior in relation to disability, employees with some type of limitation / impediment continue to be “chosen” to perform functions of less complexity, responsibility and / or remuneration.” (CARDOSO, 2016, p. 60).

Asked about the path for inclusion of people with dwarfism, the participants highlighted the importance of information, a broad approach in the media, compliance with the inclusion laws and the creation of new public policies, accessibility in public and private environments, that is, that the laws were complied with (BRASIL, 2001; 2004; 2009; 2017).

We found that research participants' impressions of people with dwarfism can be made through healthy representation or negative images that create or reinforce a cultural stereotype - people who work in the entertainment industry, often to ensure their livelihood and who they are often seen as great shows, reinforcing the idea that they are objects of entertainment. Thus, a person with dwarfism may be intellectually inferior, be scorned and not be considered as a citizen who is self-sufficient or not mature, as reported by some research participants who express dwarfism (FARIA, 2020; FARIA, MARIANI and LIMA, 2020).

People with dwarfism realize, from an exceedingly early age, that other people see them and treat them not only as physically different people, but as people of inferior status or social identity, deviating from a pattern and often marginalized (ARREGUI, 2009; FARIA, 2020).

Thus, these people are often excluded in the school context due to the physical issue. This behavior ends up leading to the isolation of the child with dwarfism that is perceived in the condition of social vulnerability and is threatened in his need to belong to a social group (PEARCE and THOMPSON, 1998; LOPES NETO, 2005). Thus, it is considered, however, that “individuals with physical disabilities should be educated in a normal, welcoming environment, being offered material resources and environments close to other students, thus avoiding segregation” (CHAGAS and MIRANDA, 2007).

When a stigmatizing condition threatens the inclusion of people in social groups, it causes psychosocial effects on people (ARREGUI, 2009). The effects that stand out are apathy, lack of motivation and emotional block, with damage to the well-being and the psychological aspect of the person with dwarfism (GOLLUST et al., 2003; CERVAN et al., 2008; ARREGUI, 2009; LIMA, 2019). There are cases in which the fear of exposure occurs in social contexts that can potentially produce more rejection and exclusion (FARIA, 2020).

Our research reaffirmed that people with dwarfism still face the lack of accessibility in the environments, which is a fundamental condition for the democratization of spaces and the right of people to come and go, as emphasized by some participants in our research.

Some of them reinforced in their responses that a person with dwarfism has to face enormous barriers throughout their life, often due not only to their physical limitations, but, above all, to the limitations resulting from the devaluation of their identity as a person deficient as exemplified by the participants who answered the questionnaires and which is also found in the literature (ALVES and ROMANO, 2015; TAVARES et al., 2016; ALCANTARA; SILVA and SOARES, 2017; BALLEN et al., 2019).

People with dwarfism realize, from a very early age, that other people see them and treat them not only as physically different people, but as people of inferior status or social identity, deviating from a standard and often marginalized (ARREGUI, 2009; FARIA, 2020) .

Thus, these people are often excluded in the school context due to physical issues. This behavior ends up leading to the isolation of the child with dwarfism that is perceived in the condition of social vulnerability and is threatened in his need to belong to a social group (PEARCE and THOMPSON, 1998; LOPES NETO, 2005).

When a stigmatizing condition threatens the inclusion of people in social groups, it causes psychosocial effects on people (ARREGUI, 2009). There are cases in which the fear of exposure occurs in social contexts that can potentially produce more rejection and exclusion (FARIA, 2020).

Our research reaffirmed that people with dwarfism still face the lack of accessibility in environments, which is a fundamental condition for the democratization of spaces and the right to come and go of people, as emphasized by some participants in our research.

Some of them reinforced in their responses that a person with dwarfism has to face enormous barriers throughout their life, often due not only to their physical limitations, but, above all, to the limitations resulting from the devaluation of their identity as a person with disabilities as exemplified by the participants who answered the questionnaires and which is also found in the literature (TOMÉ, 2014; ALVES and ROMANO, 2015; TAVARES et al., 2016; ALCANTARA, SILVA and SOARES, 2017; BALLEN et al., 2019;, FARIA, 2020).

It is verified, constantly, that the infrastructure and architecture of many physical environments are still thought having as standard the average height, the result of a lack of knowledge about the disability. There is a lack of recognition that individuals with dwarfism are citizens of duties and rights, on an equal basis with others. The lack of accessibility in products and services contributes significantly to the maintenance of prejudice and social exclusion, contrary to what is provided by law (BRASIL, 1996, 2001; 2017; CAIADO, 2009).

Some of them reinforced in their responses that a person with dwarfism has to face enormous barriers throughout their life, often due not only to their physical limitations, but, above all, to the limitations resulting from the devaluation of their identity as a person with disabilities as exemplified by the participants who answered the questionnaires and which is also found in the literature (ALVES and ROMANO, 2015; TAVARES et al., 2016; ALCANTARA, SILVA and SOARES, 2017; BALLEN et al., 2019).

It is verified, constantly, that the infrastructure and architecture of many physical environments are still thought having as standard the average height, the result of a lack of knowledge about the disability. Although medical complications and physical barriers are very important problems for people with dwarfism, without a doubt, what most concerns these people are the difficulties that arise from the social stigmatization of their physical condition (PRADO et al., 2004; LIMA, 2019) that it was also pointed out by most of the research participants. Such stigmatization is directly related to the lack of knowledge about the genetic and physiological characteristics of people with dwarfism.

Despite the political and social efforts for inclusion, it is still a challenge to overcome the social barrier, due to the long historical period of rejection of people with physical deformities, left on the sidelines for having their bodies judged as abnormal by society (MENDES, 2016; LIMA, 2019). The forces that led them to be ridiculed are still in evidence - facts that were reported by some participants in the survey conducted by us.

People with dwarfism often suffer from problems related to self-perception and social adjustment, facing difficulties, as our research revealed. A solution found to combat discrimination has been the active participation of these groups, socially inferior, and in associative movements, where they help in different sectors of the subject's life, such as social, professional and family relationships.

Such movements favor social interaction between people with dwarfism, allowing them to find social support and encouragement to live from each other's life experiences (FARIA, 2020). Thus, through the dissemination of knowledge, the publication of laws and the promotion of inclusion can change the reality of people with dwarfism. As Ablon (1981) emphasized,

it is suggested that a cognitive restructuring of the self-image occurs through the process of forced objective perception of other people who share a similar physical condition. This acceptance of self-identity and the physical identification of dwarfism allow people to lead their lives happier and more effectively. (ABLON, 1981, p. 25).

Through the questionnaires it was evident that people with dwarfism, despite being classified as physically disabled, still face the lack of accessibility in public spaces and public transport, having thus subtracted their right to autonomy (ABLON, 1981; FARIA, 2020). Even with the so-called advent of inclusion, especially in the field of education, it was observed that stunting is still a condition unknown to a considerable portion of the population and, thus, fully justifies the realization of the present study (FARIA, 2020; FARIA, MARIANI and LIMA, 2020).

Such occurrence is due to the lack of information and scientific productions of a social and educational nature that can clarify this type of disability and the needs presented by people who have such a physical condition, in addition to the medical condition (FARIA, 2020; FARIA; MARIANI; LIMA, 2020). All this conduct of discrimination, experienced by those who have dwarfism, results from a lack of understanding about the condition, in addition to the lack of knowledge that this characteristic is not an impediment to a socially active life (MENDES, 2016).

It was exactly from these concerns present in the day-to-day life of a person with dwarfism that gave rise to and justify the present study, leading to what the anthropologist Roberto Augusto Da Matta calls the strangeness of the family, where the researcher's challenge is the observation of reality itself, finding strangeness in which everyday life crystallizes, having to disconnect emotionally (DA MATTA, 1978).

Thus, there are still circumstances in our society that impose numerous barriers and difficulties on people with dwarfism when they need to dress, get around, communicate, work, and have leisure outside the home (ALVES and ROMANO, 2015; BRUNO; BERALDO, 2016; TAVARES et al., 2016; ALCANTARA, SILVA and SOARES, 2017; BALLEN et al., 2018; FARIA, 2020).

It is hoped that the present study will contribute to the clarification about dwarfism and that it will provoke interest in new research on the subject and positive changes in society, based on the understanding that the main impediment barrier for inclusion to be effective is the proper human behavior. Understanding the differences, it is possible to change practices and, in this way, build a society where everyone can live with dignity in conditions of equity.

Conclusion

The research carried out showed that knowledge about stunting is still scarce, especially in Brazil where there is a lack of adequate dissemination tools capable of making society aware of inclusion and, thus, breaking the social and architectural barriers that harm the person's quality of life with dwarfism. For this reason, we intend to make the produced booklet - “Dwarfism in Debate: Pedagogical Booklet for Social Inclusion” - free and online, in the form of an e-book, and its variants in the forms of Spoken Book and Video interpreted in Libras, aiming to convey information about this theme in a didactic and reflective way.

REFERENCES

ABLON, J. Dwarfism and social identity: self-help group participation. Social Science e Medicine, v. 15b, p. 25-30, 1981. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7987(81)90006-5. [ Links ]

ADELSON, B. M. Dwarfs: The changing lives of archetypal 'curiosities' and echoes of the past. Disability Studies Quarterly. v. 25, n. 3, 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v25i3.576. [ Links ]

ALCANTARA, A. C.; SILVA, A.; SOARES, A. A moda e os portadores de acondroplasia: um estudo comparativo através da modelagem de calça. 5º. Congresso Científico Têxtil e Moda. Centro Universitário FEI, Campus São Paulo. Anais... 2017. [ Links ]

ALVES, C. S.; ROMANO, F. V. Design e tecnologia assistiva: produto para público com nanismo. Fourth International Conference on Integration of Design, Engineering and Management for innovation. Florianópolis, SC. Anais .... 2015. [ Links ]

ARREGUI, S. F. El estigma social del enanismo óseo: consecuencias y estrategias de afrontamiento. Tese (Doctorado em Psicologia Social), Departamento de Psicología Social y de las Organizaciones, Facultad de Psicología, Madrid, ESP, 2009. [ Links ]

BALLEN, C. F.; GONÇALVES, G. O.; POFFO, C.; RIBEIRO, M. S.; G.; DICKIE, I. B. Nanismo - a moda aliada a ergonomia como fator de inclusão In: 13º Congresso Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design. São Paulo: Blucher, Anais... 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5151/ped2018-4.3_aco_35. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Justiça. Secretaria dos Direitos da Cidadania. Coordenadoria Nacional para Integração da Pessoa Deficiente. Mídia e deficiência: manual de estilo. 3.ed. Brasília 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 3.298, de 20 de dezembro de 1999. 1999. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Congresso Nacional. Decreto nº 3.956 de 8 de outubro de 2001. Promulga a Convenção Interamericana para a Eliminação de Todas as Formas de Discriminação contra as Pessoas Portadoras de Deficiência. 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Congresso Nacional. Decreto nº 5.296 de 2 de dezembro de 2004. 2004. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto Nº 6.949, de 25 de agosto de 2009. 2009. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.472, de 31 de julho de 2017. 2017. [ Links ]

BRUNO, A. P.; BERALDO, I. P. Aplicação do design universal em produto de moda para pessoas com acondroplasia. 12º Colóquio de Moda - 9ª Edição Internacional 3º Congresso de Iniciação Científica em Design e Moda, Fortaleza, Anais ... 2016. [ Links ]

CAIADO, K. R. M. Convenção Internacional sobre os direitos das pessoas com deficiências: destaques para o debate sobre a educação. Revista Educação Especial, v. 22, n. 35, p. 329-338, 2009. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, L. M. G. Pessoas com deficiência e inclusão no mercado de trabalho um estudo sobre lei de cotas, conflitos e cont(r)atos. Dissertação (Pós-graduação em Ciência Política). Universidade de Brasília, DF. 2016. [ Links ]

CHAGAS, R. S. C.; MIRANDA, A. A. B. A inclusão escolar na universidade: concepções de coordenadores e discentes. Ensino em Re-Vista, v. 14, n. 1, p. 57-72, 2007. [ Links ]

CERVAN, M. P.; SILVA, M. C. P.; LIMA, OLIVEIRA, R. L.; COSTA, R. F. Estudo comparativo do nível de qualidade de vida entre sujeitos acondroplásicos e não acondroplásicos. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, v. 57, n. 2, p. 105-111, 2008. [ Links ]

DASEN, V. Dwarfism in Egypt and classical antiquity: Iconography and medical history. Medical History, v. 32, p. 253-276, 1988. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025727300048237. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO DO SENADO FEDERAL. Decreto Legislativo Nº 198, de 2001. 10/3/2001, p. 2742. [ Links ]

DINIZ, D. O que é deficiência. São Paulo, SP: Editora Brasiliense, 2012. [ Links ]

FARIA, A. N. M. Cartilha esclarecedora sobre a necessidade de compreender e incluir socialmente as pessoas com nanismo. Dissertação. (Curso de Mestrado Profissional em Diversidade e Inclusão). Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, RJ, 2020. [ Links ]

FARIA, A. N.; FIGUEIREDO, D.; PINHEIRO, R.; LIMA, N. R. W. A educação como ferramenta de inclusão social de pessoas com deficiência física superdotadas: uma discussão necessária In: LIMA, N. R. W., PERDIGÃO, L. T. E DELOU, C. M. C. Pontos de vista em diversidade e inclusão, v. 6, ABDIn/PERSE, 1ª. ed, Niterói, RJ, p. 54-61, 2019. [ Links ]

FARIA, A. N.; LIMA, N. R. W. Nanismo em debate: cartilha pedagógica para inclusão social. E-Book, 1. ed. Niterói, RJ. CMPDI, v. 1. 26p., 2020a. [ Links ]

FARIA, A. N.; LIMA, N. R. W. Falando sobre o nanismo e a inclusão social - Livro Falado. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro, RJ, IBC, v. 1, 2020b. [ Links ]

FARIA, A. N. M; MARIANI, R; LIMA, N. R.W. Cartilha pedagógica para a inclusão social de pessoas com nanismo: para que serve? Revista Eletrônica Científica Ensino Interdisciplinar, v. 6, n. 18, p. 580-596, 2020. [ Links ]

FARIA, A. N.; VASCONCELOS, J. P. S.; LIMA, N. R. W. Nanismo em Libras. Vídeo, 1. ed. Niterói: Jvasconcelos Tradução e Interpretação, São Gonçalo, RJ, v. 1, 2020. [ Links ]

FRAYER, D. W.; HORTON, W. A.; MACCHIARELLI, R.; MUSSI, M. Dwarfism in an adolescent from the Italian late Upper Palaeolithic. Nature, v, 330, n. 6143, p.60-62, 1987. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/330060a0. [ Links ]

FRAYER, D. W.; MACCHIARELLI, R.; MUSSI, M. A Case of chondrodystrophic dwarfism in the Italian late upper paleolithic. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, v. 75, p. 549-565, 1988. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330750412. [ Links ]

GERHARDT, T. E.; SILVEIRA, D. T. Método de Pesquisa. Planejamento e Gestão para o Desenvolvimento Rural da SEAD/UFRGS, Porto Alegre, RS: Editora da UFRGS, 2009. [ Links ]

GIL, A. C. Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social - 6. ed. - São Paulo: Atlas, 2008. [ Links ]

GOLLUST, S. E.; THOMPSON, Richard E.; GOODING, H. C.; BIESECKER, B. B. Living with achondroplasia in an average-sized world: An assessment of quality of life. American Journal of Medical Genetics, v. 120A, n. 4, p. 447-58, 2003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.20127. [ Links ]

HABERER, J. The little difference. Dwarfism and the media. GRIN Verlag: Munich, 2010. [ Links ]

LIMA, M. P. Compreensão psicossocial da vida de trabalho para pessoas com nanismo: entre a estigmatização e o reconhecimento. Tese (Doutorado em Psicologia Social, Instituto de Psicologia). Universidade de São Paulo, SP. 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.11606/t.47.2019.tde-18112019-182200. [ Links ]

LOPES NETO, A. A. Bullying - aggressive behavior among students. Jornal de Pediatria, v. 81(5 Suppl.), p. S164-S17, 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2223/jped.1403. [ Links ]

LOPES, G. C. O preconceito contra o deficiente ao longo da história. EFDeportes.com, Revista Digital, Año 17, nº 176, 2013. https://www.efdeportes.com/efd176/o-deficiente-ao-longo-da-historia.htm [ Links ]

LOPES, R. SILVA, M. C. P.; CERVAN, M. P.; COSTA R. F. Acondroplasia: revisão sobre as características da doença. Arquivos Sanny de Pesquisa em Saúde, v. 1, n. 1, p. 83-89, 2008. [ Links ]

MENDES, M. S. Deficiência física e promoção da saúde: o lugar do sujeito. Tese (Doutorado em Saúde Coletiva, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas) Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP. 2016. [ Links ]

MOURA, D. L. Corrigindo o estigma através do espetáculo: o caso da equipe de futebol de anões. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, v. 37, n. 4, p. 341-347, 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbce.2015.08.002. [ Links ]

ORNITZA, M.; P., MARIE, J. Fibroblast growth factors in skeletal development. Chapter Eight. Current Topics in Developmental Biology, v. 133, p. 195-234, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.11.020. [ Links ]

PEARCE, J. B.; THOMPSON, A. E. Practical approaches to reduce the impact of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, v. 79, p. 528-53, 1998. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.79.6.528. [ Links ]

PRADO, A. G. B.; GERASSI, C. D.; CATUNDA, C. T.; ARAUJO, C. B. S.; TINOCO, D. R.; GIMENA, R. N. P.; SILVA, V. M.; SHOLL-FRANCO, A. A influência da baixa estatura sobre as representações psicossociais. Ciências e Cognição, v. 2, p. 50-60, 2004. [ Links ]

PRITCHARD, E. Cultural Representations of dwarfs and their disabling effects on dwarfs in society. Considering Disability Journal, v. 1, 2017. [ Links ]

ROUSSEAU, F.; BONAVENTURE, J.; LEGEAI, M. L. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature, v. 371, p. 252-254, 1994. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/371252a0. [ Links ]

SANTIAGO, J. F. Educação e direitos humanos: educando para a conscientização, para a inclusão e para a humanização. Revista de Educação, v. 44, n. 157, p. 46-61, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22560/reanec.v44i157.157. [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, D. T.; CÓRDOVA F. P. A pesquisa científica. In: Métodos de pesquisa. Tatiana Engel Gerhardt e Denise Tolfo Silveira (orgs.). Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS, 2009. [ Links ]

TAVARES, A. S.; CARDOSO, R. L. S. A.; SANTOS, J. F.; SAMPAIO, G. Y. H. Acessibilidade para pessoas com deficiência: algumas dificuldades em projetar para indivíduos com nanismo, p. 609-620. VI Encontro Nacional de Ergonomia do Ambiente Construído. Anais... Blucher Design Proceedings, v. 2 n. 7, 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5151/despro-eneac2016-ace07-4. [ Links ]

TOMÉ, R. J. M. Deficiência, nanismo e mercado de trabalho - dinâmicas de inclusão e exclusão. Dissertação. (Mestrado em Ciências do Trabalho e Relações Laborais) 2014. ISCTE, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisboa. PT. [ Links ]

WANG; Y.; LIU, Z.; LIU, Z.; Heng ZHAO, H.; Xiaoyan ZHOU, X.; CUI, Y.; HAN, J. Advances in research on and diagnosis and treatment of achondroplasia in China. Intractable ana Rare Diseases Research, v. 2, n. 2, p. 45-50, 2013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5582/irdr.2013.v2.2.45. [ Links ]

WYNN, J. KING, T. M.; GAMBELLO, M. J.; WALLER, D. K.; HECHT, J. T. Mortality in achondroplasia study: A 42‐year follow‐up. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A, v. 143A, n. 21 p. 2502-2511, 2007. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.31919. [ Links ]

Received: June 01, 2020; Accepted: February 01, 2021

texto em

texto em