Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensino em Re-Vista

versão On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.29 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 08-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v29a2022-7

DOSSIÊ 1: A EXPERIÊNCIA DA PESQUISA COLABORATIVA EM REDE

Critical Collaborative Research: Portuguese language teaching planned with deaf students for deaf students1

2Doctor of Sciences. Professor at the Federal Institute of São Paulo. E-mail: malymfreitas@ifsp.edu.br.

3Doctor of Applied Linguistics and Language Studies. Professor at the Federal University of São Paulo. E-mail: ssfidalgo@unifesp.br.

4Doctor of Education. Professor at the Federal University of the ABC Region. E-mail: claudia.vieira@ufabc.edu.br.

This study, part of a completed doctoral research, aimed to understand the teaching-learning possibilities of grammatical aspects of the Portuguese language for deaf people who already have experience with this language. It was supported by the Historical-Cultural theory (VYGOTSKY 1924 - 1934), and by authors who discuss the teaching and learning of Portuguese for the deaf (PEREIRA, 2009; LODI, et. All., 2015; and VIEIRA, 2014 and 2017). It is inserted in the Critical Collaboration Research - PCCol (MAGALHÃES, 2006; FIDALGO, 2006, MAGALHÃES and FIDALGO, 2019) because it is based on the negotiation of meanings, allowing reflection and transformation of the participants. The data were produced in a virtual course where the participants, when they concluded, were able to expose their impressions and suggestions about the course. The analyzes revealed that the possibilities of teaching and learning Portuguese for the deaf go through visual teaching strategies that include Libras as a mediating language in all stages of teaching and learning.

KEYWORDS: Deaf; Portuguese for the deaf; Education of the deaf; Historical-Cultural Theory; Critical collaborative research

Este estudo, recorte de uma pesquisa de doutorado finalizada, objetivou compreender as possibilidades de ensino-aprendizagem de aspectos gramaticais da língua portuguesa para surdos que já tenham experiência com essa língua. Apoiou-se na teoria Histórico-Cultural (VYGOTSKY 1924 - 1934), e em autores que discutem o ensino-aprendizagem do português para surdos (PEREIRA, 2009; LODI, et al., 2015; VIEIRA, 2014; 2017). Está inserido na Pesquisa Crítica de Colaboração - PCCol (MAGALHÃES, 2006; FIDALGO, 2006, MAGALHÃES; FIDALGO, 2019) porque se baseia na negociação de sentidos e significados, possibilitando reflexão e transformação dos participantes. Os dados foram produzidos em um curso à distancia onde os participantes, ao concluírem, puderam expor suas impressões e sugestões sobre o curso. As análises revelaram que as possibilidades de ensino-aprendizagem do português para surdos perpassam por estratégias visuais de ensino que contemplem a Libras como língua mediadora em todas as etapas do ensino-aprendizagem.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Surdos; Português para surdos; Educação de surdos; Teoria Histórico-Cultural; Pesquisa Crítica de Colaboração

Este estudio, que forma parte de una investigación doctoral finalizada, tuvo como objetivo comprender las posibilidades de enseñanza-aprendizaje de los aspectos gramaticales de la lengua portuguesa para las personas sordas que ya tienen experiencia con esta lengua. Fue apoyado por la teoría Histórico-Cultural (VYGOTSKY 1924 - 1934), y por autores que discuten la enseñanza y el aprendizaje del portugués para sordos (PEREIRA, 2009; LODI, et al., 2015; VIEIRA, 2014; 2017). Se inserta en la Investigación de Colaboración Crítica - PCCol (MAGALHÃES, 2006; FIDALGO, 2006, MAGALHÃES; FIDALGO, 2019) porque se basa en la negociación de significados, permitiendo la reflexión y transformación de los participantes. Los datos se produjeron en un curso a distancia donde los participantes, al finalizar, pudieron exponer sus impresiones y sugerencias sobre el curso. Los análisis revelaron que las posibilidades de enseñar y aprender portugués para sordos pasan por estrategias de enseñanza visual que incluyen a Libras como lengua mediadora en todas las etapas de la enseñanza y el aprendizaje.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Sordo; Portugués para sordos; Educación de sordos; Teoría Histórico-Cultural; Investigación Colaborativa Crítica

Introduction

Discussing issues that involve reading and writing teaching-learning for Brazilian deaf people, considering the language conceptions that support teaching methodologies in the country, is important in order to understand the current practices in deaf literacy. It is also essential that we understand how literacty practices took place in the past because the teaching-learning processes - of Portuguese for the deaf in this study - of the past bear strong influence in current processes.

For over a hundred years, Sign Languages were forbidden in schools worldwide; and the same holds true for Brazil: oral modality Portuguese language teaching was prioritized aiming to draw deaf people the closest to the listener normality standard. This approach is called oralism. In the oralist approach, Portuguese language reading and writing teaching is based on traditional methods and language is seen merely as a code. In this view, language is taught by means of the memorization of phrasal structures, that range from simple to more complex grammar constructions - as was common practice in the past for the teaching of foreign and second languages (and is still common practice in some places). One example that comes to mind is the audiolingual approach. Classrooms that use such approaches strongly base their pedagogical practices on repetition, copies, reproduction of a model, mechanic and decontextualized exercises. Before being able to write a text, the student must learn the units that compose the language: letters and their pronunciation psattern, syllables, words, phrases, and text, following an ascending order of a conventional complexity degree. However, due to the lack of context in which these language elements are aught, the practice showed that this makes learning too hard for students - regardless of whether they are deaf or not. Some students simply have a hard time going from small units to full texts. There are also difficulties in reading, since the texts are adapted by the teachers so as to suit what they believe to be a student’s linguistic level. These are, therefore, short, yet very complex texts because teachers end up removing signs (or signposts) that usually help the reader to understand the text, such as repetitions by umbrella terms or other types of synonymy hints, for example.

In the specific case of deaf students, in Brazil, up to the mid Twentieth Century, several oralist approaches/methods were used, most resulting from the Fitzgerald5 key principle (even though this name was not used).

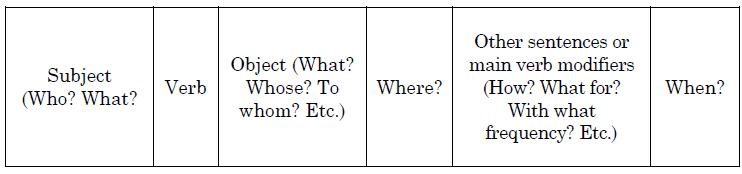

The key, as shown in the chart above, has six columns with questions referring to sentence units, “starting from the ones related to the subject, then the verb and, when students master subject and verb structures, complements are introduced one by one” (PEREIRA, 2009, p.15). In other words, students must learn the lexical and grammatical units to reach text unity.

Therefore, students were supposed to organize their sentences according to the grammatical structure given in the chart, memorizing and using it in other linguistic and discursive contexts. According to this logic, students would merely have to replace one element for another in a sentence, repeating the structure, in order to succeed in reading, writing, and communicating.

Even though some deaf students were able to reach the expected objectives for language use, most of them failed, as stated by Pereira (2014 - 2019, p. 2)

As a result of the language view and speaking emphasis, although some students were able to reach a good level of the Portuguese language usage, most of them only showed fragmented structures of the language. There were no connective elements (prepositions and conjunctions), verbs were not inflected, and the words did not follow the language phrasal order. (our translation)

Due to the failure of the oralist education and its serious consequences to the development of deaf people who could not reach the expected learning level, as well as the social movements of deaf communities for freedom to use the Brazilian Sign Language (Libras), the total communication approach began to enter classrooms in Brazil, around the 1980s. Thus, the simultaneous use of any other communication means - such as sign language, miming and manual alphabet - started to be accepted, along with oralization. In Brazil, we mainly used the Signalized Portuguese (PS)6, i.e., the Sign Language lexical and/or the signs created within the Portuguese language grammatical structure.

However, in this approach only Sign Language fragments were used, while the language’s structure and grammar were not taken into account. The aim was to teach the Portuguese language for the deaf and make communication between deaf and hearing interlocutors easier.

Libras signs and other space-visual resources were inserted in the communication, teaching, and learning contexts, but the teaching methods remained those that held language as a mere code, i.e., what we sometimes refer to as traditional methods. Deaf people remained at the margin of the educational process and failed to master reading and writing in Portuguese, which meant that the educational failure reached with the oralist method remained with the inclusion of other space-visual resources as part of total communication.

Abroad, as consequence of the above, as well as the results of Willian Stokoe’s research, in the 1960s, indicating Sign Languages as real languages, a movement for deaf bilingual education7 was initiated. Thus, Sign Languages began to be considered essential for the development of deaf people, and stated to be disclosed in social media. However, research8 shows that school teachers of deaf students still find difficulties in learning and using it with fluency, especially due to lack of appropriate teacher education. According to Giordani (2015, p. 144), schools pretend to use Libras in school as students’s first language, because the fact is that teachers have little knowledge of it, and end up simplifying its use; other school employees either do not or have no access to Libras. This history, evidently, had and still has direct impact on the pedagogical practices used for teaching the deaf.

Along these lines, the number of investigations about literacy also increased and we began to discuss the concept of language not as a code but in its interactional and dialogical9 perspective. This is follows an understanding that the syllables and letters are no longer the school units. The texts become the focus. The text is then understood as source of discursive practice, and grammar, according to this model, should be learned through the use of text genres, i.e., within a context.

We have also intensified research in deaf education, several of which were in Portuguese as a second language teaching-learning processes. This happened mainly after the recognition of Libras as the language of the deaf community, by means of bill nº 10.436/2002 (BRASIL, 2002) and its regulation through Decree nº 5626/2005 (BRASIL, 2005). With this legislation, Libras went into a period of promotion, of visibility in society in general, and it has become mandatory at schools at least when there are deaf students in the school. So, even though this is still a rather narrow view of Libras inclusion in schools, it represents the beginning.

With these transformations in language perspective, including the recognition of sign language as a language, the definition of Libras as the official Brazilian for the deaf community, the insertion of this language in educational and social spaces etc., we would except a better result in the quality of deaf education. However, that is not what investigations showed. Rather, they have shown that we still base our Portuguese teaching practices in a concept of language as a code, in traditional teaching methods, especially valuing the systemic knowledge, i.e., a belief that vocabulary and grammar teaching-learning can guarantee that the student will read and write well. Besides that, reading is still seen as a representation of oral production: for the listener, the relation phoneme/grapheme; for the deaf, the relation letter /manual alphabet.

The manual alphabet is a representation of the Portuguese letters10; When it comes to vocabulary, we try to equate Portuguese words and its letters with a Libras sign, believing, in both cases, that a biunivocal relation between the two languages is possible. That means that we still stumble on practices based on total communication, especially with Signalized Portuguese both in communication and in reading and writing strategies. We ought to clarify that Signalized Portuguese (PS) is characterized by

[...] the use of LIBRAS signs inserted in the Portuguese language, which is the language of the majority group. Since Sign Language lacks some components of the phrasal structure (prepositions, conjunctions etc.) found in Portuguese, signs are created to express them. Besides that, time, number and gender markers are used to describe the Portuguese language through signs (DORZIAT, 1997, p. 305).

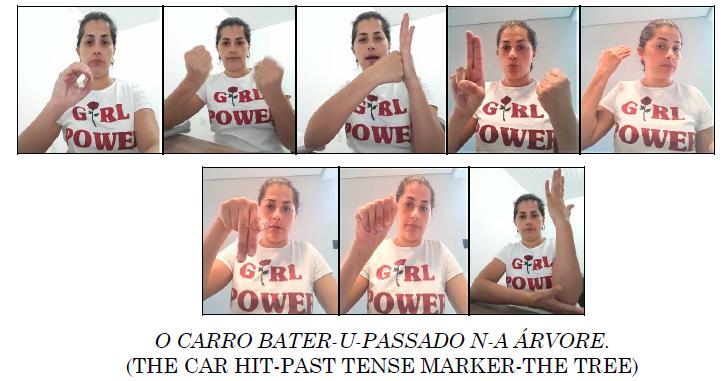

This was widely used in Total Communication (CT) as a communication facilitator. However, Signalized Portuguese (PS) or “the signalized oral systems, as we know them, do not correspond to the Sign Languages: they bear the oral language superstructure whilst the lexical items are borrowed from the Sign Language of the country in a more or less systematic manner” (SOUZA, 2003, p. 338), i.e., the oral language overlaps the special-visual language in a way. Besides that, Signalized Portuguese does not contemplate the visuality - here understood not as synonymous to what can be seen, because it would be possible for both Signalized and written Portuguese, but as part of the Libras grammar, i.e., the visuality that composes the utterance in a given communication episode, - since it carries the Portuguese Language grammatical structure, which is an audio-oral language. An example is the translation of the sentence in Portuguese O carro bate una árvore [The car hit the tree]. In Signalized Portuguese, we would have the following structure:

For every word in Portuguese there is a respective sign but this still follows the oral language grammar structure. Thus, even though we “see” the signs, the Portuguese language structure does not allow for the simultaneity which is typical of the Sign Languages, favouring the meaning construction by means of the utterance visuality. Also, according to Vieira (2017):

This practice was called Bimodal Bilingualism, because there are two modalities of different languages, in this specific case, oral and visual, and leads speakers to believe that there is a match between sign and word, mischaracterizing the Sign language as a language, i.e., considering it as a mere representation of the major language (VIEIRA, 2017, p.64).

Signalized Portuguese has not been developed by the community that used it (i.e., deaf people) in a collaborative manner and in accordance to their necessities as is the case with all languages. It was based on some beliefs and meaning dear to the deaf community, but not the totality existing in a language with signs, arbitrarily and collectively built.

In Libras, the above sentence example could be expressed thus:

In the Libras structure, we have a sign for car, a classifier11 (CL) for car and the tree sign, simultaneously, and the car moving towards the tree until collision, with facial and body expressions showing the resulting damage. We can see here the statement visuality, which is inherent of this linguistic modality.

It is important to highlight that even though this is still a reality in most schools, we must recognize that there is some initiative of change in practice by some teachers who are seeking bilingual education12.

Thus, we consider it important to investigate what are the main difficulties found by deaf people in some aspects of Portuguese language teaching-learning.

Methodology

This study is methodologically based on Critical Collaborative Research (PCCol13) because the reflection about teaching-learning instruments, teaching methodology, content and pedagogical resources were carried out by everyone involved in the investigation - the deaf participants and the researcher - with a view to transforming practices and reality. In the collaborative investigation, everybody is a participant, researcher included, in knowledge production, and this involves supporting each other, probing into words with a view to promoting reflection, and collective reinterpretation of actions. According to Fidalgo (2006, p. XVIII; 2018, p.37),

This new way of producing knowledge implies listening each other [...] to build knowledge together, considering, throughout the work, among other aspects, ‘the kind of knowledge produced, the context of production, social responsibility and reflection’.

So, each one has the same opportunities to show their opinions and points of view about the reality in which they are inserted and choose themes or “problems” to be discussed. In this kind of research, the hierarchy between the participants (inevitable though it may be, since there will always be a researcher who, among other aspects, is the one responsible for the final report) is given less importance and it minimized as much as possible, being replaced by the view that that everyone has potential to collaborate in discussions with their knowledge, opinions, beliefs, values, experiences etc.

Following this methodological matrix, this investigation was carried out collaboratively, since participants: researcher and deaf participants, were actively searching for answers to the concerns that originated this study. Also according to Fidalgo (2006, p.25) discussing Magalhães (1994, p.72), we should remember that:

[...] this kind of investigation takes the other as part of the investigative process and object for data analysis; it seeks to negotiate with participants which instruments, data production practices, whenever possible, what would have been found, thus avoiding one-sided conclusions.

That does not mean that the collaborative process admits only similar ideas and agreeing arguments. Instead, collaborating is only possible with conflicts, idea confrontation, questioning and tension. It is important to remember that every time an interlocutor does not comprehend what is being said and asks a question, a conflict is established (and everyone should pitch in trying to build an answer to solve this conflict). In this kind of study, the term conflict is not, therefore, negative. It is what allows for participants to rethink their speeches and negotiate meanings so that new knowledge is built.

Besides that, among the participants, there are different life stories, beliefs, values, culture and this diverse experience and world vision can bring to light idea confrontation, which causes both interpersonal and intrapersonal conflicts (i.e., questioning). Conflicts are always part of learning, moreover, they are what actually allows for learning to take place. Schön (1992) states that there is no learning without conflict. So, idea confrontation and interpersonal and intrapersonal conflicts favor the learning, and allow knowledge to be built because they trigger negotiation and resignification. Thus, the interpretation of all participants about the discussed theme (pedagogical action or even teaching-learning theories) is debated.

For data production, the researcher developed an online course about some grammatical aspects of the Portuguese language as per the orthographic agreement between Portugal and Brazil. This course was delivered via the Moodle platform. Four deaf people with higher education level participated in the research, besides the teacher-researcher. The first model offered (stage 1), presented the course divided in 4 modules about following subjects: diaresis mark, graphic accents, the use of hyphen, the crasis accent, and the use of why and because - which in Portuguese are reduced to the same expression, but sometimes written together (porque) and others, separately (por que), with or without graphic accent, depending on the position and function. Each module had a video class explaining the Portuguese orthographic rules in Libras and supplying examples, activities and Discussion Forum (FD), where the participants could ask questions and assess the course reporting their difficulties and providing suggestions to solve them. We also had virtual meetings which were called Reflective Talks14 (CR in Portuguese), where participants and researcher could further reflect upon what had been posted on the forum (FD). From this conversation, the crasis accent module was reformulated (stage 2) considering participants’ suggestions, then they retook the course and reassessed it.

Data analysis was carried out using thematic content (BRONCKART, 1999) and signification (VYGOTSKY, [1934] 2001). Thematic content, according to Bronckart (1999, p. 97), is the set of information explicitly showed in the text and that was built by participants through knowledge originated in the formal worlds15. Thematic content analysis is based on the Reflective Talks and students’ participation in the Forum. The thematic content charts are divided in three columns. Following Fidalgo (2006), the first column includes the theme - in nominalized form created from the research question. The second column shows an interpretation (or signification as per the understanding of the researcher of the participant’s speech), and the last column brings the participant’s speeches per se16. Even though Vygotsky ([1934] 2001) has used the terms sense and meaning, current readings of the author’s work indicate that these terms, split like this, can lead to a dichotomic vision - which was not adopted in his work. Fro this reason, we use the signification concept as discussed by Aguiar and Ozella (2006,2013). According to Vygostky ([1934]2001) meaning is built collectively, while senses are individual internalized and produced. To him, “a word acquires its sense in the context where it emerged. Meaning remains stable throughout all changes undergone by the senses.” (p.125).

Discussion and data analysis

Signalized Portuguese is not Libras

One difficulty pointed by participants regarding the first course offered was the fact that explanations were made in Signalized Portuguese (PS), which made content comprehension harder. This difficulty happens because, as explained before, the Signalized Portuguese is not composed by visual aspects like Libras. This difficulty can be noticed in the chart below, taken from the reflective conversation with Mariana17:

Chart 2 Difficulties raised during CR about the first course model

| Theme | Signification | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty type | Signalized Portuguese does not promote comprehension | P29: I LIBRAS CLEAR-NOT YOU EXPLAIN BETTER UNDERSTAND ME HOW LIBRAS IMPROVE DEVELOP “int” M29: WHY YOU I NOTICE YOU FOLLOW PORTUGUESE EXAMPLE SLIDES EQUAL SIGNS EQUAL EXAMPLE DRIVE WAY UNDERSTAND-NOT CLEAR-NOT UNDERSTAND ¨int¨ P30: [...] EXAMPLE CLASS HAS EXAMPLE SENTENCE HOW USE ACCENTS EXAMPLE SLIDES I FOLLOW PORTUGUESE EXAMPLE OPINION YOU SHOW OPINION SENTENCES LIBRAS DIFFERENT “int” M30: I THINK BETTER DIFFERENT BECAUSE LIBRAS INHERENT LIBRAS EXPLAIN LIBRAS SHOW PORTUGUESE DEAF CAN UNDERSTAND LIBRAS IF FOLLOW PORTUGUESE HEAVY HOW UNDERSTAND-NO SEQUENCE // |

Source: Freitas (2020, p. 113)

Mariana explains that the teacher was not communicating in Libras when giving examples and because of that she had problems to understand the meaning of that sentence. She said she noticed the signalization sequence was identical to the one in the slides in Portuguese. She concludes saying that following the Portuguese, or using Signalized Portuguese makes content heavier and comprehension harder.

This happens because the Signalized Portuguese, as said before, is not a natural language, but a communication system. According to São Paulo city Portuguese education program for the deaf (SÃO PAULO, 2019), communication systems are not natural languages, but tools created to enable communication between people, which cannot be linguistically analyzed as they do not have natural languages structures. Therefore, Signalized Portuguese does not have the necessary linguistic structure to explain a language.

Mariana completes her answer at the discussion forum (FD), as follows:

Chart 3 Difficulties raised at the FD about the first course model

| Theme | Signification | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty type | Libras cannot be replaced by PS | Mariana: “It’s impossible to replace Libras... Libras follows Portuguese, I could not understand...” |

Source: Freitas (2020, p. 114)

When she states that “it’s impossible to replace Libras”, we understand that she means every language has its own grammatical structure; Therefore, when simply replacing every word for a sign, we automatically prioritize the major language structure - in this case, the oral language. This means Signalized Portuguese “does not use Libras as a language, but its signs as a tool” (VIEIRA, 2017, p.69). This way the comprehension is impaired. That is why Mariana (M30) and Bruna (B2) suggest that Libras is used to explain the Portuguese language, as follows:

Chart 4 Suggestions pointed during CR about the first course model

| Theme | Signification | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Methodology that creates Portuguese language learning space by deaf students | Use of Libras to explain Portuguese. Deaf people understand Libras. |

P30: [...] SENTENCES SLIDES I FOLLOW PORTUGUESE EXAMPLE OPINION YOUR SHOW OPINION SENTENCES LIBRAS DIFFERENT “int” M30: I THINK BETTER DIFFERENT BECAUSE LIBRAS INHERENT LIBRAS EXPLAIN LIBRAS SHOW PORTUGUESE DEAF CAN UNDERSTAND LIBRAS P2: [...] YOU OPINION NEED SIGN CORRECT “int” WHY “int” B2: [...] BUT TIME EXPLAIN NEED LIBRAS AFTER TIME CLASS PORTUGUESE 3 THINGS THIS IDEA LIBRAS buoy 1, THIS SPELLING PORTUGUESE buoy 2, THIS SIGN OR IMAGE buoy 3// [...] |

Source: Freitas (2020, p. 116)

Mariana and Bruna stated that deaf people can understand better when explanations are made in Libras. Mariana yet complements that “Libras show Portuguese”, which means that through Libras the deaf can visualize Portuguese with clarity.

Moura (2015) researched her own teaching-learning practice of Portuguese reading at a school of São Paulo that receives deaf Students of Preschool and Elementary School levels and counted on students from 4th year of Cycle I and the teacher-researcher as participants. The analysis was carried out during a Portuguese reading class as L2 and, as a result, the author states the importance of using Libras as L1, without which there is no way to teach the target language - in this case, Portuguese in written modality. She also brings to discussion of Libras as a mediator of Portuguese language teaching-learning. As examples of data analysis, the researcher assessed a text extract reading by two students. While reading, one of the students asked her about the meaning of a certain word in the text. She oriented them to try to infer the word meaning from inside the text, which means in context and not to hold to only one word. In the end, students completed the proposed reading and found that context is important to understand what is being read.

In case of deaf people, this occurs when reading can disconnect from the direct match word-sign and when the sign language is used as a mediator in negotiating senses and meanings (MOURA, 2015, p. 104).

Bruna, just as Mariana, also suggests doing the explanations in Libras, and the use of Libras + spelling + image when exemplifying the rules. This way the deaf person has more chances to understand for having more possibilities to access information. This suggestion is corroborated by Sofiato and Leão (2014) when stated that,

It is noticed that the resources hybridization18 can subserve the concept comprehension process by deaf students and provide new experiences from their contextualization (SOFIATO; LEÃO, 2014 p.03097).

Thus, when authors state that the resource hybridization can facilitate learning by deaf students, that means the more ways with different resources, mainly visual ones, are offered to the deaf, bigger are the learning possibilities.

We are also covered by decree nº 5626/2005 (BRASIL, 2005), regulation of law nº 10.436/2002 (BRASIL, 2002), that besides recognizing Libras as the deaf Community language, states in article 22, clauses I and II, paragraph 1st, that Libras and written Portuguese are the instruction languages of deaf education. Therefore, according to the next chart, the suggestion to use Libras to explain and exemplify when remodeling the course was accepted and the Signalized Portuguese was removed from it.

Chart 5 CR about the reviewed course

| Theme | Signification | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Methodologies, resources, and instruments that can be used to solve such difficulties | Explanations made in Libras, the visuality and presentation of several examples make content more understandable | P1: BEFORE EXPLAIN CONTEXT IMAGE GRAVE ACCENT REMEMBER ASK WHAT BEFORE DIFFICUL NEW HOW “int” M1: BEFORE LIBRAS FOLLOW A LOT PORTUGUESE FOLLOW CAN NOT UNDERSTAND NOW NEW CHANGE LIBRAS CAN UNDERSTAND ALSO BETTER VISUAL SQUARE LIBRAS (CL) ALSO A LOT SHOW EXAMPLES SEQUENCE EXAMPLES + OTHER UNDERSTAND BEFORE EXAMPLE FEW NOW MORE EXAMPLES COMPARE DIFFERENT IMPROVE. P27: EXAMPLE RULE AFTER EXAMPLES WORD ++ IMAGE WORD IMAGE (CL table) HELP “int” [...] J29: YES SOMETIMES USE LIBRAS SUPPORT TEACH PORTUGUESE UNDERSTAND “int” #is not# MOM ALWAYS WORD + SHOW HAVE-NO #did not have# IMAGE BEAUSE SOMETIMES EXAMPLE WORD MANGO SOMETIMES SHOW IMAGE FRUIT OR SHIRT ONLY HELP SUPPORT BUT AFTER SENTENCE I NEED REALIZE CONCEPT FRUIT OR SHIRT P2.1: On the second video there is no Signalized Portuguese, only Libras. P2.2: Your opinion better Libras then? S2: Yes Libras, but I believe it is important to compare language structures, because notice the different between the structure of Libras and Portuguese it becomes easier to relate the different situations in which the grave accent occurs. |

Source: Freitas (2020, p. 119)

Mariana, João and Sérgio agree that the course remodeling made it more comprehensive with the exclusion of Signalized Portuguese and the use of Libras to explain and exemplify19 the module content (grave accent). Thus, I agree with Vieira (2017) when stating that,

We know, however, that the deaf have total condition to learn, but to achieve it they need to live experiences in L1, in this case Libras. It will mediate learning L2 - Portuguese language because Libras will structure the thought and then make contents significantly understood and ‘translated’ (VIEIRA, 2017, p. 96, our bold).

With this understanding, the Signalized Portuguese does not have condition to explain or exemplify Portuguese language in writing and reading situations. The only language that can accomplish this objective for Brazilian deaf people is Libras.

The reviewed and remodeled course uses Libras to explain and exemplify, following Mariana and Bruna’s suggestions. The translation of examples is done with subtitles in Portuguese, showing the differences between the two languages.

Considering the deaf communicate with Sign Language, the treatment of grammatical elements could be built based in contrastive and discursive language grammar, through which teachers relate aspects concerning both languages (PINHEIRO, 2020, p.380).

This way, considering the deaf linguistic specificity, as well as relating the languages in question, comparing and pointing their similarities and differences - being L1 metalinguistic conscious and the one that will provide comprehension about L2’s use and functioning - showed to be a possible way for Portuguese teaching-learning also in virtual environment, the same way it has shown on in-person teaching-learning, even when the subject studied is an L2 specificity, commonly arid and of difficult comprehension even for listeners.

Final considerations

In general, the difficulties pointed out by the participants are in the first course model and they are more related to methodology and strategies used which, in a way, will influence the content. They all reported, among other things, difficulties due to the use of Signalized Portuguese. Studies about this aspect indicate a false feeling that the use Signalized Portuguese as a language will cover and fulfill the visual strategy field. When inserting visual resources allied to the use of Libras in the remodeled course, participants reported a better comprehension of concepts for them being followed by examples that gathered Libras + image + subtitles in Portuguese.

The use of Signalized Portuguese revealed that, even though studies and research about Libras in education remain as teaching-learning practices - grounded on structural differences and modality between languages - that Sign Language is considered insufficient to explain Portuguese language. Research showed the right opposite. Signalized Portuguese, for representing Portuguese language with signs, many times “randomly”, does not have conditions to explain or exemplify neither the use nor the form of Portuguese language, which is as complex as Libras. Signalized Portuguese cannot replace any language, neither Libras nor Portuguese Language; therefore, it can be excluded as a communication option and as a mediator between the deaf person and the Portuguese language.

The theoretical foundation in which this study is anchored provided reflection over the strategies used, and many teachers still use in the classroom: L1 and L2 teaching-learning for deaf students based on outdated language conceptions, L2/LE teaching methodologies that, even though in a not conscious/not reflected way, have strong influence in classroom practices. It has also confirmed that the essential of teaching-learning is recognizing the need of the one who is searching for knowledge. In other words, it does not matter how well elaborate the teacher believes their course is if it does not make sense for the student. If it causes difficulties, we must replan. And it is necessary for the deaf to have the same right at school to negotiate senses and significations and the paths that will lead them to build knowledge.

REFERENCES

AGUIAR, W. M. J.; OZELLA, S. Núcleos de significação como instrumento para apreensão da constituição de sentidos. Psicologia: Ciência e profissão. Brasília, v.26, n.2, p. 222-245, jun. 2006. Disponivel em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-98932006000200006. Acesso em 15 de janeiro de 2019. [ Links ]

AGUIAR, W. M. J.; OZELLA, S. Apreensão de sentidos: aprimorando a proposta dos núcleos de significação. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos. Brasília, v. 94, n.236, p. 299-322, jan./abr. 2013. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbeped/a/Y7jvCHjksZMXBrNJkqq4zjP/abstract/?lang=pt#. Acesso em 22 de novembro de 2018. [ Links ]

ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DOS SURDOS. Revista do I.N.S.M. Rio de Janeiro: I.N.S.M., n. 2, 1949. Disponível em: http://repositorio.ines.gov.br/ilustra/handle/123456789/378. Acesso em 14 maio 2020. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, M. Estética da criação verbal. São Paulo, Martins Fontes: [1953] 1992. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto 5626, de 22 de setembro de 2005. Regulamenta a Lei 10.436, de 24 de abril de 2002, que dispõe sobre a Língua Brasileira de Sinais e o art. 18 da Lei 10.098, de 19 de dezembro de 2000. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília, 2005. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2005/decreto/d5626.htm. Acesso em: 1 maio 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei 10.436 de 24 de abril de 2002. Dispõe sobre a Língua Brasileira de Sinais. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília, 2002. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2002/l10436.htm. Acesso em: 1 maio 2017. [ Links ]

BRONCKART, J. P. Atividade de linguagem, texto e discursos: por um interacionismo sócio-discursivo. São Paulo: EDUC, 1999. [ Links ]

DORZIAT, A. Metodologias específicas ao ensino de surdos. Programa de Capacitação de Recursos Humanos do Ensino Fundamental Deficiência Auditiva, Brasília, v. I, n.4, p. 299-308, 1997. [ Links ]

FELIPE, T. A. Libras em contexto curso básico: Livro do Estudante. 8ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Walprint gráfica e Editora, 2007. [ Links ]

FIDALGO, S. S. A linguagem da inclusão/exclusão-Escolar na história, nas leis e na prática educacional. Tese (Doutorado em Linguística Aplicada e Estudos da Linguagem) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica - PUC/SP, São Paulo, 2006. [ Links ]

FIDALGO, S. S. A Linguagem da Exclusão e da Inclusão Social na Escola. São Paulo: Editora Unifesp, 2018. [ Links ]

FREITAS, M. M. Ensino-aprendizagem de aspectos da língua portuguesa para surdos com experiência acadêmica: um estudo à luz da pesquisa crítica de colaboração. Orientadora: Sueli Salles Fidalgo. 2020. 218 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação e Saúde na Infancia e na Adolescencia) Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Guarulhos, 2020. [ Links ]

GIORDANI, L. F. Encontros e desencontros da língua escrita. In: LODI, A. C. B.; MÉLO, A. D. B.; FERNANDES, E. Letramento, Bilinguismo e Educação de Surdos. Porto Alegre: Editora Mediação, 2015, p. 135 - 152. [ Links ]

GÓES, M. C. R. Linguagem, surdez e educação. Campinas: Autores Associados, 1996. [ Links ]

KOCH, I. G. V. Desvendando os segredos do Texto. 7ª ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

LODI, A. C. B.; MELO, A. D. B.; FERNANDES, E. Letramento, bilinguismo e educação de surdos. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2015. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, M. C. C. Etnografia colaborativa e desenvolvimento do professor. In: Trabalhos de Linguística Aplicada. Campinas, n. 23, p. 71-78, jan/ jun 1994. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, M. C. C. Por uma Prática Crítica de Formação Contínua de Educadores. In: FIDALGO, S. S.; SHIMOURA, A. S. Pesquisa crítica de colaboração: Um percurso na formação docente. São Paulo: Ductor, 2006. p. 94-103. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, M. C. C.; FIDALGO, S. S. Reviewing Critical Research Methodologies for Teacher Education in Applied Linguistics. Delta, V. 35, n. 3, 2019. [ Links ]

MOURA, D. R. Libras e Leitura de Língua Portuguesa para Surdos. Curitiba: Appris, 2015. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, M. C. C. Leitura, escrita e surdez. 2. ed. São Paulo: FDE, 2009. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, M. C. C. Ensino da Língua Portuguesa para Surdos. Acervo Digital da Unesp. [entre 2014 e 2019] Disponível em: https://acervodigital.unesp.br/bitstream/unesp/252175/1/unesp-nead_reei1_ee_d11_da_texto1.pdf. Acesso em: 20 abr. 2019. [ Links ]

PINHEIRO, L. M. A “inclusão” escolar de alunos surdos: colaborações para pensar as adaptações curriculares. Curitiba: Appris, 2020. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Secretaria Municipal de Educação. Coordenadoria Pedagógica. Currículo da cidade: Educação especial: Língua Portuguesa para surdos. São Paulo: SME / COPED, 2019. [ Links ]

SCHÖN, D. A. Formar professores como profissionais reflexivos. In: NÓVOA, A. Os professores e sua formação. Lisboa: Dom Quixote, 1992. [ Links ]

SKLIAR, C. (org.). Atualidade da educação bilíngue para surdos. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 1999. [ Links ]

SMYTH, J. Teachers Work and the Politics of Reflection. American Educational Research Journal Summer, [S. l]. v. 29, n. 2, p. 267-300, 1992. [ Links ]

SOFIATO, C. G.; LEÃO, G. B. O. S. O uso da Iconografia/imagem na educação de surdos: diálogos possíveis. XVII Endipe - Encontro Nacional de Didática e Prática de Ensino. Universidade Estadual do Ceará - Publicado no EdUEce, Livro 3, 2014. [ Links ]

SOUZA, R. M. Intuições “Linguísticas” sobre a Língua de Sinais nos séculos XVIII e XIX, a partir da compreensão de dois escritores surdos da época. Revista D.E.L.T.A., São Paulo, v. 19, n.2, p. 329-344, 2003. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, C. R. Bilinguismo e Inclusão: Problematizando a questão. Curitiba: Appris, 2014. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, C. R. Educação bilíngue para surdos: Reflexões a partir de uma Experiência Pedagógica. Orientadora: Karina Soledad Maldonado Molina Pagnez. 2017. 236 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2017. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, L. S. A formação social da mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, [1930] 1998. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, L. S. A construção do pensamento e da linguagem. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, [1934] 2001 (Tradução de Paulo Bezerra). [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, L. S.; LURIA, A. R.; LEONTIEV, A. N. Linguagem, desenvolvimento e Aprendizagem. São Paulo: Ícone, [1933] 1998. [ Links ]

7To know more about deaf bilingual education, see Skliar (1999) and Lodi, Melo and Fernandes (2015).

9Based on Bakhtin (1953), Koch (2011, p. 17) discuss that, in interactional and dialogical language conception, the subjects are noticed as social builders, the text is the interaction place and interlocutors are active subjects who build and are built in it. In this conception, according to the author, “text meaning is, therefore, built in the text-subjects interaction (or co-enunciators-text) and not something that pre-exists this interaction”.

10In November 30th 1949, the National Deaf Association published in the Deaf National Institute magazine a statement that “The digital alphabet is really air writing or spelling” (no page number). The date stated is Nov 3rd, 1949, but this could be a graphic error. At that time, the alphabet was perceived as a representation of written Portuguese. Availabel at: http://repositorio.ines.gov.br/ilustra/handle/123456789/378. Accessed on May14th, 2020.

11Classifiers in Libras, according to Felipe (2007, p. 172), “are hand configurations or dispositions that are related to the object, person, animal or vehicle, and that work as agreement markers. In Libras, the classifiers are forms that, replacing names that preceed them, can be tied to the verbal root so as to classify the subject or object connected to the verb action. Thus, Libras classifiers are gender agreement markers”.

12In Brazil, there is a multiplicity of comprehensions about what bilinguism for the deaf is, and this impacts directly in teaching practices. There is no consense, and maybe this is not craved, once schools are composed by diferente cultures, histories, experiences and conceptions.

13In Portuguese, the Critical Collaborative Research that we follow is called, PCCol, i.e., Pesquisa Crítica de Colaboração, developed by Magalhães since 1990, and by her with collaborators in the last twenty years approximately.

14We call it Reflective Talk because the discussion did not follow exactly all steps of a Reflective Session (MAGALHÃES, 2006, P.101) or the Reflection Cycle poposted by Smyth (1992).

15Acording to the author, there are three formal worlds: the physical world, related to objective actions; the social world, related to rules and regulations which participants criticize or to which they are subjected; and the subjective world, related to what is internalized, to what only the participant has access, for being related to their subjectivity.

16The transcription of participants answers from Libras to Portuguese follow transcription norms developed by Felipe (2007) reviewed and adapted by the research groups Linguistic Inclusion in Scenarios of Educational Activities (ILCAE) and Social Educational Inclusion and Teacher Education (ISEF), as well as the study group: Deaf Identity and Culture (GEICS) - all in meetings at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). The underlined answer refers to the speech extract that gives meaning to what is in the second column called signification.

18Resource hybridization can be understood as “[...] versatility of pictorial support in relation to the presentation forms, interdisciplinarity and different possibilities of contribution to the teaching learning process [...] .” (SOFIATO; LEÃO, 2014 p.03097)

Received: March 01, 2021; Accepted: November 01, 2021

texto em

texto em