Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Ensino em Re-Vista

versión On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.29 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 08-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v29a2022-55

DOSSIÊ 3 - A ESCOLA NOS DIAS ATUAIS: E AGORA?

Reflections and reticence: statements about Remote Teaching in times of pandemic1

2Doctor in Science Education. Federal University of Rio Grande, Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. E-mail: keppspeterson@gmail.com.

3Doctor in Science Education. Federal University of Rio Grande, Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. E-mail: laviniasch@gmail.com.

4Master in Mathematics Education. Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. E-mail: melany_feliz@yahoo.com.br.

The work presents an investigation about the enunciations that students have said about remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic period. To produce the data, we applied a questionnaire to elementary school students from a public school located in Rio Grande do Sul. We identified that most access activities at home, and connect to the internet via wi-fi. Most do not approve of remote learning; few consider it quiet. In this group it is possible to observe that there is a social and psychological structure supporting them. Students point out difficulties in understanding to carry out the activities, mentioning five subjects. From the analysis, we constructed two statements: 1) remote learning is not approved by those students with a lack of physical structure and/or assistance from guardians; and 2) remote learning is a viable alternative in the pandemic period.

KEYWORDS: Elementary School; COVID-19; Remote Teaching; Basic Education

O trabalho apresenta uma investigação acerca das enunciações que os estudantes têm dito sobre o ensino remoto no período de pandemia do COVID-19. Para produzir os dados, aplicamos um questionário para alunos do Ensino Fundamental de uma escola pública situada no Rio Grande do Sul. Identificamos que a maioria acessam as atividades em casa, e se conectam a internet via wi-fi. A maioria não aprova o ensino remoto; poucos consideram tranquilo. Nesse grupo é possível observar que existe uma estrutura social e psicológica os amparando. Os estudantes apontam dificuldades de entendimento para a realização das atividades, mencionando cinco disciplinas. Da análise construímos dois enunciados: 1) o ensino remoto não é aprovado por aqueles estudantes com falta de estrutura física e/ou auxílio de responsáveis; e 2) o ensino remoto é uma alternativa viável no período de pandemia.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Ensino Fundamental; COVID-19; Ensino Remoto; Educação Básica

El trabajo presenta una investigación sobre los enunciados que los estudiantes han dicho sobre el aprendizaje remoto durante el período pandémico del COVID-19. Para producir los datos, aplicamos un cuestionario a estudiantes de primaria de una escuela pública ubicada en Rio Grande do Sul. Identificamos que la mayoría accede a las actividades en casa, y se conecta a internet vía wi-fi. La mayoría no aprueba el aprendizaje a distancia; pocos lo consideran tranquilo. En este grupo es posible observar que existe una estructura social y psicológica que los sustenta. Los estudiantes señalan dificultades de comprensión para la realización de las actividades, mencionando cinco temas. A partir del análisis, construimos dos afirmaciones: 1) la enseñanza remota no es aprobada por aquellos estudiantes con falta de estructura física y/o asistencia de tutores; y 2) el aprendizaje a distancia es una alternativa viable en el período pandémico.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Enseñanza Fundamental; COVID-19; Enseñanza a Distancia; Educación Básica

Introduction

In late 2019 and early 2020, the world faced an increasing number of reports of the new coronavirus. As the news expanded coverage of the spread of a previously little-known virus, we also saw the number of cases of people with the disease increase. Thus, a chaotic scenario began to emerge. Field hospitals were prepared, there was misinformation and relativization of a virus that could be lethal for many who contracted it.

Doors began to close: commerce, physiotherapy centers, gyms, bars, restaurants, parties, schools and all places with movement of people are some examples that foreshadowed the profound changes we would have to face. Among all these places, the transformations occurring in the school become the object of our attention, especially in the municipal educational network in which we work.

If we trace a brief timeline in this municipality, we start with a decree issued by the prefecture suspending classes in the municipal network for 30 days, starting March 20, 2020 according to Municipio (2020). Weeks passed and the number of cases of the disease continued to increase, just when projections indicated that Brazil had not yet reached the peak of the disease according to Costa (2020).

With no scheduled date for the return of face-to-face activities, the Municipal Secretariat of Education and Sports (SMED) determined (as of May) that schools should maintain a link with students through social networks and socioemotional activities. These work proposals for students, according to SMED, were to be "enjoyable, playful, interdisciplinary, resolved autonomously by the students and/or in collaboration with the family, without causing an overload of work, especially at this atypical time of social isolation" (TORRE, 2020, p. 1).

Without its own digital platform or even indicated by SMED, using the individual social networks (Facebook and whatsapp) of the teachers, without any news informing of its subsidy with equipment such as computers/tablets for the preparation of classes, the municipality council of the investigated municipality establishes remote teaching - which was maintained until the end of the 2020 school year.

With respect to the students, as education professionals, we had to (re)construct strategies to better develop teaching and attend, even in a very limited way, to their doubts, anxieties and problems. Along with this, it became increasingly necessary to establish contact and maintain it between us, teachers and students, so that the outdoors of this pandemic scenario would not undermine our bonds and make the teaching and learning process unfeasible.

We know that, for the students, this would not be an easy task, it would require from each one of them commitment and dedication to their studies, in a more solitary way at home, something that did not happen before the pandemic, since they had the help of teachers and classmates. It was a period of much adaptation, successes and mistakes, in which each one lived a different reality. We, as basic education teachers, thought of some ways to approach and learn about the experiences they had during this period.

Authors who discuss teaching practice from internships, such as Tardiff (2014), Pimenta and Lima (2004) have reinforced the idea that the teaching and learning process involves more than the transmission of curricular content and knowledge. Moreover, the process involves a close relationship between teachers and students. In the context of the pandemic, these relationships were modified and, therefore, we began to ask ourselves: what do students say and think about remote teaching? That is, what statements do they make about this form of teaching?

From this initial inquiry, we propose in this paper to analyze the enunciative plots that are constituted on teaching remote in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodological approaches

To achieve our objectives, we developed a questionnaire constructed through Google Form-a virtual tool for data production that can be accessed by computer, cell phones, and tablets-with 11 questions (multiple-choice and essay) related to remote teaching in this pandemic period. The questions were applied to students.

In this specific work, we will only address 7 questions, which were grouped by us in two blocks, namely:

TABLE 1: Questions in the questionnaire made available to physical education students in a public school in the RS municipal network.

| Access and execution of tasks | 1. How do you access the Internet? |

| 2. Do you do the activities alone or with the help of someone? | |

| Questions on remote learning and teaching | 3. Do you have comprehension difficulties in carrying out the activities requested by the teachers? If so, which ones? |

| 4. Which of the following approaches do you think are good options for effective learning during online or remote teaching (content texts; question and answer exercises; games; crossword puzzles; seven errors; quiz; logical reasoning; other)? | |

| 5. What has it been like for you to be out of the school routine and do online activities? | |

| 6. Do you prefer remote teaching/online teaching or face-to-face classes in school? | |

| 7. Would you like to return to face-to-face classes without COVID-19 vaccine? Why? |

Source: Authors, 2020.

The questionnaire was applied to all 6th to 9th grade classes of the Elementary School (EF) of a public school in a city of Rio Grande do Sul; and was available between September 21 and December 1, 2020. We had 88 students who responded to the questionnaire.

The pedagogical coordination and the center's management team signed an informed consent form indicating that neither the center's nor the students' personal data, nor any other information that could identify them, would be disclosed and that it would be used only for academic purposes. In addition, in the description of the form, students were asked to consent to the use of the data for research purposes and were also informed that it was intended to map their positions and understandings about online/remote learning.

As the SMED of the municipality investigated did not offer any educational platform for remote teaching, the school we investigated taught its classes through groups on the social network Facebook throughout 2020. And, it was in this environment that we disseminated the questionnaires. In addition, two authors of this work are teachers at the center, which facilitated dissemination and contact with the coordination and management team. For this reason, the results and discussions that we will present were also shared with the school's management and pedagogical team.

As a theoretical-methodological perspective, we take the concept of discourse as a set of statements and the Foucauldian-oriented discourse analysis according to Foucault (2013) and Foucault (2014). Thus, we will treat the students' responses as statements, we will pay attention to the formation of possible statements that allow us to understand the constitution of the remote teaching discourse in the pandemic. Furthermore, by way of identification, throughout the text, we will present the statements in quotation marks, in addition to informing that they have only undergone grammatical changes that do not compromise the meaning of the sentence/expression.

Foucault (2009) takes the statement as the thing written or said; and the utterance is the one constructed by the researcher through the analysis of these statements. All this enunciative plot composes the discourses on education and remote teaching in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic in the analyzed school space. In this framework, discourses are like the practices that form the objects of which Foucault (2013) speaks. Thus, we will seek to understand the discourse of EF students on remote teaching during the pandemic, presented through the statements of the responses to the questionnaires.

Regarding the way in which we structure the results of this article, in a first moment, we present general information answered by the students, such as the possibility of accessing the Internet; and the assistance of those responsible for carrying out the tasks. In a second moment, we will present the two statements created from the statements that express the position of the students in relation to remote teaching. These statements are like elements that assemble a certain discourse according to Foucault (2013) forming a discursive network that represents what the students think about remote teaching in the municipality. Namely, the statements that support this discourse are: 1) remote teaching is not approved by those students who lack physical structure and/or help from tutors; and 2) remote teaching is a viable alternative during the pandemic period.

Results and discussions

Regarding the first question in Table 1, " 1. How do you access the Internet?", we were interested in Internet access, since we were asking whether the students needed to leave home to access school material or not. Thus, we found that 92% of the students accessed it at home; 5.7% at another place (not specified); and 2.3% at the home of family or friends.

This data is very dear to consider that, in this research, we did not cover the countless students who did not have access to the Internet and, consequently, to this first movement of school organization in the period of the pandemic. These students were only able to have contact later, when the delivery of printed material was released by the SMED in a municipality of the RS. This scenario is explained by the fact that the context in which the analyzed school is inserted is one of social vulnerability, serving many low-income students who do not have access to the internet or equipment such as computers, tablets or even cell phones.

The reality of the students has been solitary when carrying out the activities proposed by the teachers. Most of them (53.4%), in response to the second question "Do you do the activities alone or with the help of someone?", stated that they have developed their work individually. We are aware of the limitations imposed by remote teaching, among which is the lack of interaction among students, and we also know how important it is for the teaching and learning process to provide opportunities to share, exchange, contact and communicate among subjects as Tardiff (2013) and Larrosa (2003) put to us. In particular, when it comes to Primary Education, even in its second stage, we work with children, with young people who are entering adolescence and are still in the process of building their subjectivity and autonomy.

Larrosa (2003) emphasizes that discourses permeate us, reach us and cross us, and thus, in some way, construct us, subjectivize us and form us as subjects. In this specific case, the focus is on the students and how they are constituted in the face of a teaching marked by the coronavirus pandemic. According to the aforementioned author: "Formation is nothing more than the result of a certain type of relationship with a certain type of word: a constitutive, configuring relationship, in which the word has the power to form or transform the sensibility and character of the reader" (LARROSA, 2003, p.46). Thus, the formation of today's students has been permeated by this form of teaching and the new adaptations that reality sometimes imposes.

In this sense, we find the other part of these data, which reveals that 30.7% of the students receive help from the mother figure to carry out their work. As for help from the father figure, the figure does not reach 1%. The remaining amounts are distributed among other subjects, such as siblings (4.5%), grandparents (1.1%) and aunts and uncles (1.1%). In presenting these figures, we do not intend to criticize the families and/or guardians of the students. We are aware of the difficulties that afflict our society and many of the students in public schools. Thus, to illustrate, we can pay attention to the low level of education in the country - which may make it impossible to help in the performance of work - or even the time they have to be absent to be at work according to IBGE Educa (2021).

There are many variants that may surround such results, so it is worth highlighting these figures here to contextualize where the students' statements come from; to present this reality to the academic community (even if it is specific to a school); and also, to reaffirm to the competent bodies the need for support of the most diverse orders to these families.

Following the discussions on learning in remote teaching, we understand that the absence of family members in carrying out the work and the lack of contact with other classmates are factors that may be imbricated in the difficulties presented by the students. We affirm this because 77.9% of them indicate that they have difficulties in carrying out the proposed activities. Of course, the teacher has a leading role in this process, however, we cannot lose sight of the fact that the educational context is not only built in the teacher-student verticality, the process is much broader, other figures and contexts converge in it, such as those already mentioned: classmates, structure and also other professionals in the school.

In the midst of this context of difficulties faced by students, we posed the question "What has it been like for you to not have the school routine and do online activities?". In the words of most of the researched, the routine outside the physical space of the school has been "bad", "boring", "difficult", "horrible" and "complicated". Students say that they are not able to learn, that they are often distracted and that they miss school, as we can see in this statement: "It is very bad, because our parents have to explain it to us. It's not the same. I really miss all the teachers and being present at school with you teaching the subjects properly."

By means of this empirical material, taking the above statement as an example, we were able to perceive the learning difficulties of the students and, through this, we arrived at the elaboration of the following statement: remote teaching is not approved by the students with lack of physical structure and/or or help from those in charge. In this sense, we can say that the students point out the learning difficulties and denounce the lack of structural organization and, therefore, do not approve of remote teaching. We believe that, for many researchers in the field of education and basic education teachers like us, this statement would be expected, given the reality that the country and public schools live, especially those located in neighborhoods and communities. Therefore, it is important to pay attention here to what students point out as factors that hinder the realization of this process.

Following the analysis of the statements that compose it, part of this difficulty comes from the interaction engaged with the teacher. In the specific case of the municipality surveyed, in 2020 we did not have a specific digital platform such as Classroom, for example, which was adopted by the Rio Grande do Sul state government as a virtual environment for students in state schools to carry out activities according to Rio Grande do Sul (2020). This is not to say that only a digital platform is enough, that it is the solution to the problem of school education in the context of the pandemic or even that it is sufficient to solve learning problems. We can consider it as an environment that facilitates this interaction stated by students and contributes to the organization of studies for some.

We noticed this desire for organization in the students when they express that they are "struggling" to "find themselves in the lost subject" or that they are not "finding themselves" as they have lost the "explanations of some topics" amidst the postings made by the teachers in the class Facebook group.

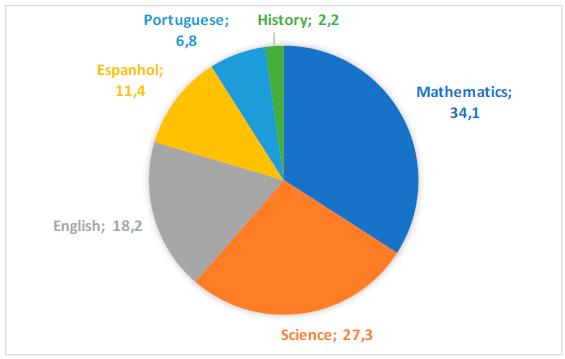

Still with respect to the question addressed to the difficulty of comprehension in carrying out the activities requested by the teachers, we present the following results: 20.6% of the students said they had no difficulties, 77.9% indicated having some kind of difficulty, and 1.5% did not answer. Regarding the difficulties, we identified five subjects among the most mentioned by them, which are:

Source: Authors, 2020.

GRAPHIC 1: Subjects with which the investigated students have difficulties during remote teaching.

Among the students who pointed out their difficulties in general, we highlight here some statements: "I have difficulties in understanding some things to do"; "I have difficulties in almost all subjects, because it is not the same to do them on the Internet"; "I have difficulties in online activities. I prefer the help of teachers"; "I don't understand some activities". Given this, the students' difficulties are evident and, as some describe, it would be better to develop them in the classroom with the teacher's explanation.

These anxieties presented by the students, sometimes, they face them alone, or with the help of research on the Internet: "from time to time I have difficulties, but I try to solve it in my own way"; "I have some difficulties, but then I research and understand". It is necessary to reflect on how demanding this period is for students, so that they have organization in their studies, so that they make an effort to understand the contents, however, this effort is not always enough. Some resort to internet resources, such as videos, to try to better understand the contents and activities proposed by teachers. Throughout 2020, students did not have synchronous classes, where they could talk to teachers since, with the school's use of Facebook, contact was basically through comments on posts.

In addition to the difficulty in learning and the absence of face-to-face explanations by the teacher, most of the students emphasized, as we have seen, not approving of remote teaching. Statements such as the following express it "very boring, I prefer 100% normal classes"; "very annoying, I understand almost nothing. I prefer face-to-face classes"; "horrible, I don't like the online class".

Regarding the percentage of this question on the students' preference for face-to-face or distance teaching, the answers show us that the majority of students (77.3%) prefer face-to-face classes, and only 15.9% say they prefer remote teaching. Although in this question the students did not express the specific reason why they disapprove of remote teaching, we can agree with this position with the statements in the previous questions. As we have seen, the students have difficulties in carrying out the activities proposed by the teachers and, an expressive number, end up developing them without help from family members. These factors (in addition to others that are beyond the scope of this research), seem to us to be interrelated with the disapproval of remote teaching.

Disturbances in remote teaching are revealed in addition to Internet access and learning difficulties, statements show that a portion of students have problems viewing activities on mobile due to formatting and file incompatibility, for example. "Lack of motivation", "easy distraction at home" and "lack of peers and teachers" are other recurring factors. In this sense, the idea that school is a productive environment for interaction between subjects is reinforced. Students mention the lack of peers and teachers, not in terms of learning content, but with the prerogative of encounter, dialogue, exchange of experiences and socialization that this relationship can provide. This is not a new discussion in the context of school education. Dayrell (1996), in the 1990s, already stated that students are sociocultural subjects and many understood school classes as a means of socialization with colleagues.

The need for remote teaching

On the other hand, following the discussions, although to a lesser extent (25%), a part of the statements is oriented towards the ease provided by remote teaching. From the statements, we identified three groups: the first group describes this form of teaching as "normal", "calm", "good" and as "something different". They prefer school, but agree with this form of teaching. A second group responds that they are enjoying this period, but emphasizes that "in my case it became easier because I have internet"; "I think I am doing well, but it must be taken into account that I am doing online therapy"; or even "on the one hand, I am happy, because I have help from my mother at home to do the activities".

Regarding this support and help from the aforementioned relatives, we highlight the following statements: "in the subjects I have doubts, I study more, I ask my aunt for help and I can do the activities and learn"; "I know how to do some activities and my mother helps me a lot". However, not everyone has this structure and responsible people to help in the education of the students, as we indicated in the previous data of this research already commented. Furthermore, we understand that the role of the teacher is of utmost importance to develop the teaching and learning process; therefore, we cannot project on the responsible persons, fathers, mothers, uncles, aunts, uncles and/or grandparents, the teaching work that, in this period, was drastically compromised.

Finally, the last set of student statements is in line with the remote teaching model for safety with respect to COVID-19, as seen in the examples "at the moment my grandparents and I prefer it, we think it is safer" and "a little strange, but at the moment it is fine".

Part of these statements led us to produce, then, the second utterance of this research: remote teaching is a viable alternative in the pandemic period. Following in the wake of Foucault (2014), we consider this statement as a dispersion effect in the discourse on remote teaching, since all the above statements bring with them (for different reasons) the disapproval of this form of teaching. In the midst of this scenario, it is important to note that in the statements that facilitate the experience of remote teaching, we find subjects who have the help of their parents, who have satisfactory access to the Internet or who do online therapy. However, taking into account the total number of respondents, these students represent a small number (25%), besides expressing positions different from those of a large part of the enunciative framework that constitutes the remote teaching discourse.

We believe that these data can express what, in a way, we could already imagine. That is, the ills facing Brazilian public education are in the recent history of the country, there is nothing new. And it is also important to remember that we are not dealing here with numbers and percentages or with a fragment of history, but with lives, students, subjects. The statements express the position of these students, open up their needs (and the facilities of a few) and put us as teachers and researchers in an attentive and critical position in front of this whole context.

It can be reiterated that this is not a reality for most of those researched and gives us space to remember that the COVID-19 pandemic has shown the human fragility and chaotic situation in which we find ourselves. We are afraid of what is happening, fear and many uncertainties, and we know that teaching and school practices will not be the same after this pandemic. But in the face of all this scenario, we understand, as Saraiva, Traversini and Lockman (2020, p. 2) did, that "educating (not) is necessary". Despite the initial strangeness that this expression of the authors may cause, we understand it both in the sense that "it is necessary" to educate and we have to face this challenge and continue educating; and in the sense that "it is not necessary", since it is necessary to follow the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO), remaining in quarantine and adapting school materials. So, as teachers, we are faced with the need to have tools that provide students with material (internet access), social (help from those in charge) and psychological support to continue their studies as pointed out by Koeppe, Ferreira and Calabro (2020).

Also in this sense, we asked ourselves if the students would want to return to the face-to-face classes without the COVID-19 vaccine, and we found discourses that have health care, safety and the vaccine as basic elements. The vast majority of students, 85.9%, do not want to return without the vaccine, 12.8% believe they do, and 1.3% did not answer whether they wanted to return or not. And the statements that exemplify this attitude bring words such as: "Because I am very afraid of catching COVID-19 and continuing to infect others"; "Schools closed, lives preserved. I don't want to get sick and I don't want my teachers to get sick too"; "Because not everyone would take the same measures and I think online is better because we avoid getting infected"; and "Studying is very important to me, but my life matters more".

Other student responses also support the statement remote teaching is a viable alternative in the pandemic period, as they articulate, in the same statement, the preservation of life to the way learning and classes have been taking place in remote teaching. Some examples were, "In person at school only when the pandemic is over and all is well"; "In person, but only when the vaccine has been taken"; "In the period we are in, I prefer online, but it is easier to understand the material in person"; "Classes in person, but only after this covid, I have no interest in going back in this quarantine"; "In the pandemic, I prefer online because I know it is safer. When the pandemic is over, I prefer in person" and "I would rather be in school studying than, online classes, however, as long as there is danger of coronavirus contamination, I don't want to risk it".

On the other hand, we know of the existence of denialist statements about the COVID-19 pandemic that are against social isolation, vaccination, the use of masks, or even the use of unproven preventive treatments indicated by science. However, students who were in favor of returning to classes in person did not demonstrate positions that we could align with this science-denying discourse. Their expressions permeate other feelings, issues such as homesickness, learning difficulties and tiredness, as can be seen: "I think so... because it would be much easier to understand the subjects"; "Yes, because I miss school"; "Yes, because I am tired of staying at home, it is not the same to do it in the classroom than on the Internet"; "Yes, I have difficulties with online activities"; "Yes, I miss my friends and teachers".

In view of the statements just presented, we can see that many students understand that, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, classes have to be distance/online, both to protect themselves from possible contamination and to risk contaminating others. Certainly, many emphasize that they do not like remote/online teaching, preferring face-to-face teaching, but understand that this is a health safety reason.

If we observe, from the empirical material, we find statements that make up a recurrent discourse also in communication vehicles: if you can, stay at home. In general, this discourse circulated and continues to circulate in the largest communication vehicles in Brazil, such as O Globo, Extra, Estadão, Folha and UOL. We cannot say that it was through the aforementioned media that the speeches in favor of care, safety and vaccination against COVID-19 reached the students. Or even by the teachers' sayings through activities and distance classes. However, we can say that these discourses circulate in the social network and, in some way, have questioned them. That is, when we pay attention to statements such as "In person at school only when the pandemic is over and everything is fine"; "In person, but only when the vaccine has been taken"; "In the pandemic, I prefer online because I know it is safer" we find the reverberation of this discourse on COVID-19 in the students' discourses and we see the statements that constitute them emerge.

Conclusion

Taking into account everything already presented, the present study provided an analysis of how students access distance activities and what they have said about this period in the face of COVID-19. It is a very sensitive time and it is necessary to listen and reflect on the students' positions.

From the answers to the questionnaires, it was possible to identify two statements that support the discourse on remote teaching in the pandemic period: 1) remote teaching is not approved by students who lack physical structure and/or help from tutors; and 2) remote teaching is a viable alternative during the pandemic period. We realize, therefore, that most do not approve of remote teaching, noting various difficulties in understanding how to carry out the activities, despite understanding that it is essential for the preservation of life. Unfortunately, this new teaching has not covered everyone, and has increasingly shown the human, scholastic and structural fragility and social inequality of the country.

With this research, we not only point out the conclusions about remote teaching in this municipality from the students' statements, but we mobilize ourselves and hope that you, reader too, can think for whom remote teaching is viable and which subjects can have access to schooled education. during this pandemic period. We were able to see and answer these questions in the microcosm we operated in the municipality analyzed, but it is necessary to pay attention to these questions; and, as teachers and researchers, to seek to minimize these disparities, calling attention to the process of exclusion in which we are increasingly immersed.

REFERENCES

COSTA, G. B. Esperamos que agosto seja o pico da covid-19 nas Américas, diz Opas. Disponível em: https://noticias.uol.com.br/saude/ultimas-noticias/estado/2020/08/04/esperamos-que-agosto-seja-o-pico-da-covid-19-nas-americas-diz-opas.htm. Acesso em: 10 out. 2020. [ Links ]

DAYRELL, J. A escola como espaço sócio-cultural. In: Múltiplos olhares sobre a educação e cultura. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 1996. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, M. Arqueologia do saber. (8a ed.) Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Forense Universitária, 2013. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, M. A ordem do discurso: aula Inaugural no Collège de France, pronunciada em 2 de dezembro de 1970. São Paulo: Loyola, 2014, 74. [ Links ]

IBGE EDUCA. Conheça o Brasil - População Educação. Disponível em: https://educa.ibge.gov.br/jovens/conheca-o-brasil/populacao/18317-educacao.html. Acesso em: 18 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

KOEPPE, C. H. B.; FERREIRA, S. R.; CALABRO, L. Saúde em jogo: Ensino de Ciências e prevenção à contaminação viral para os anos iniciais do Ensino Fundamental. Revista Thema. v.18, p.170-183, ago. 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15536/thema.V18.Especial.2020.170-183.1845. [ Links ]

LARROSA, J. Pedagogia Profana: Danças, Piruetas e Mascaradas. 4. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2003. [ Links ]

MUNICIPIO. Decreto nº 6.249, de 17 de março de 2020. Dispõe acerda de medidas temporárias a serem adotadas pela Administração Pública Municipal, objetivando a prevenção ao contágio, o enfrentamento da propagação do agente patógeno denominado coronavírus (COVID-19). Disponível em: http://pelotas.rs.gov.br/noticia/prefeitura-apresenta-medidas-para-prevencao-contra-o-novo-coronavirus. Acesso em: 10 outubro 2020. [ Links ]

PARECER. Parecer 56 CEED Regras da Educação Especial. Disponível em: http://www.faders.rs.gov.br/legislacao/5/403. Acesso em: 10 outubro 2020. [ Links ]

RIO GRANDE DO SUL. Começa implantação das Aulas Remotas na Rede Estadual de Ensino. Disponível em: https://educacao.rs.gov.br/comeca-implantacao-das-aulas-remotas-na-rede-estadual-de-ensino. Acesso em: 8 out. 2020. [ Links ]

SARAIVA, K.; TRAVERSINI, C.; LOCKMANN, K. A educação em tempos de COVID-19: ensino remoto e exaustão docente. Práxis Educativa, v. 15, p. 1-24, ago. 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5212/PraxEduc.v.15.16289.094. [ Links ]

TORRE, T. D. L. Escolas municipais contam com as redes sociais para manter vínculos com alunos. Disponível em: http://www.pelotas.com.br/noticia/escolas-municipais-contam-com-as-redes-sociais-para-manter-vinculos-com-alunos. Acesso em: 8 out. 2020. [ Links ]

Received: August 01, 2021; Accepted: January 01, 2022

texto en

texto en