Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Ensino em Re-Vista

versión On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.29 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 08-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v29a2022-39

DEMANDA CONTÍNUA

Empathy in the educational context: reports from young adult and adult students1

2PhD. Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, Brazil. E-mail: gtavares33@gmail.com.

3MSc.Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, Brazil. E-mail: rozanaquintanilhags@gmail.com.

This article discusses the importance of valuing empathy in the educational context, particularly in Youth and Adult Education. It seeks to investigate how empathy, or the lack of it in the teacher-student relationship, can interfere in the teaching and learning process. Therefore, a questionnaire was applied to a class of young and adult students at the Federal Fluminense Institute. The questionnaire was created based on Carl Rogers' theory of the multidimensional construct of empathy, which includes three components: cognitive, affective, and behavioral. The data obtained reveal that in an environment that is not conducive to empathy, students seek, through their own initiatives, strategies to create empathic relationships with teachers in order to remain in the school.

KEYWORDS: Empathy; Youth and Adult Education; Teacher-student relationship; Teaching and learning process

Este artigo discorre sobre a importância de valorizar a empatia no contexto educacional e, particularmente, na Educação de Jovens e Adultos. Como objetivo, pretende-se investigar como a empatia ou a falta dela na relação professor-aluno pode interferir no processo de ensino e aprendizagem. Para tanto, aplicou-se um questionário a uma turma de estudantes jovens e adultos de um campus do Instituto Federal Fluminense, que foi elaborado com base na teoria de Carl Rogers sobre o construto multidimensional da empatia, no qual inclui três componentes: cognitivo, afetivo e comportamental. Os dados obtidos revelam que, em meio a um ambiente não propício à empatia, os alunos buscam, por iniciativa própria, estratégias para criar relações empáticas com os professores para continuarem vinculados à escola.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Empatia; Educação de Jovens e Adultos; Relação professor-aluno; Processo de ensino e aprendizagem

Este artículo discurre sobre la importancia de valorar la empatía en el contexto educativo y, en particular, en la Educación de Jóvenes y Adultos. Como objetivo, se pretende investigar cómo la empatía o la falta de ella en la relación profesor-alumno puede interferir en el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Por tanto, se aplicó un cuestionario a un grupo de estudiantes de jóvenes y adultos de un campus del Instituto Federal Fluminense, el cual fue elaborado a partir de la teoría de Carl Rogers sobre el constructo multidimensional de la empatía, que incluye tres componentes: cognitivo, afectivo y conductual. Los datos obtenidos revelan que, en un entorno poco propicio para la empatía, los estudiantes buscan, por iniciativa propia, estrategias para crear relaciones empáticas con los profesores para mantenerse vinculados a la escuela.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Empatía; Educación de jóvenes y adultos; Relación profesor-alumno; Proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje

Introdution

The well-known Arab proverb He who does not understand a look will not understand a long explanation suggests that empathy within interpersonal relations strengthens the capacity to feel and act, stimulates self-knowledge, and comprises a foundation for human skills. From this perspective, because empathetic relations between the teacher and student can help shape the social, psychological, and academic features of the individual, empathy´s role in education is a significant one.

The National Curriculum Parameters for Secondary School (PCN), for example, highlight the importance of upholding empathy in the educational context, requiring that teachers and other professionals “exercise didactic competency, the capacity to communicate, empathy, and respect for others´ identity” (BRASIL, 2000, p. 128, our translation). With the intention of contributing to the construction of a more democratic and solidary society, the National Curricular Guidelines for Basic Education (DCN) also emphasizes the importance of “developing empathy and respect for others, for what is different from us, and for students in all their diversity” (BRASIL, 2013, p. 115, our translation).

CNE/CEB Ruling 11 (BRASIL, 2000), which covers the National Curricular Guidelines for Youth and Adult Education, while asserting that in addition to possessing teacher training, including “training for EJA” (BRASIL, 2000, p. 56, our translation), the “teaching professional should be prepared for the empathetic interaction with such students and the establishment of the exercise of dialog” (BRASIL, 2000, p. 56, our translation). In addition, it states that without empathy, “a teacher who is not well-trained or is merely motivated by well-meaning voluntary idealism” (BRASIL, 2000, p. 56, our translation) will not successfully meet the specific teaching requirements demanded by EJA.

Such guidelines are grounded in the perspective by which the school environment is one that is open to dialog encompassing diverse viewpoints, one which induces individuals to move out of their comfort zones and to place themselves “in others´ shoes” in order to learn about the structural foundations and prejudice that produce inequality and to employ this knowledge in shaping their own attitudes. Empathy can thus promote an appropriate emotional school environment, one that is capable of fostering relationships that are conducive to healthy social and academic interaction.

The theme of empathy in the school setting is related to many discussions involving situations characterized by physical aggression, homophobia, bullying, the disabled, and ethnic, regional, and social diversity. Our interest in the present work, however, has been stimulated by the question of empathy within the context of Youth and Adult Education, an area composed of a highly stigmatized social group.

In order to explore this theme, this work investigates how empathy between teachers and youth and adult students, or a lack thereof, can interfere in the teaching-learning process. To do so, it collected reports from students of a Professional Education class for youths and adults and sought evidence of the existence of empathy networks developed within a school context that contributed toward human and academic development.

Empathy: a historical-conceptual approach

In order to investigate empathy in the teacher-student relationship, it is useful to employ the methodological precept proposed by German philosopher Gadamer (1986) concerning the necessity of comprehending the historicity implied by the concepts used. According to this author, it is not possible to “undertake anything without a historical-conceptual reckoning” (GADAMER, 1986, p. 88, our translation). This is because comprehension is neither exempt nor parcial; what orients observation and the construction of the research object is its context of production, which cannot be comprehended separately from the subject and the spatial-temporal circumstances of the act of the very production of knowledge. Thus, research into empathy in the educational context will possess a preliminary stage that will need to reconstruct the empirical process that has taken place by presenting a sample of the conceptual path of empathy in order to think about this object as a field of study aimed at understanding what guides or can guide interpersonal relationships in the teaching and learning process.

Adam Smith (1759), who is considered an important theoretician of modern economics, contributed to the perspective examining the construction of the concept of empathy based on the defense of the subjectivity of the subject, the fulfillment of private interests, and an explanation of the social order of the market in his theory of morality. In the work The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith (1759) examined the capacity of the individual to form moral conscience, whose judgement will take place by means of an impartial observer, that person who imagines herself in the place of the other to achieve consciousness both of herself and the morality of her own behavior. Smith calls this mechanism of human nature, which orients and defines every and all moral phenomena, “sympathy,” a term used at the time to refer to what today is meant by empathy. Sympathy (or empathy) refers not only to the consonance or the contagion of feelings, but describes a correspondence of feelings through which the subjective perception of the other is reached by putting oneself in their place through use of the imagination. In this way, Smith (1759, p. 11) made his thoughts on this matter clear by asserting:

As we have no immediate experience of what other men feel, we can form no idea of the manner in which they are affected, but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation. [...] They never did, and never can, carry us beyond our own person, and it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations.

However, it was the German philosopher of the psychological vein, Theodor Lipps, who would first write about the precursor of empathy. Lipps developed the first scientific theory of Einfülung (feel inside, feel within), in which he coined the concept of empathy for referring to an esthetic experience, understood as a relation between the artist and the spectator who projects herself into the work of art. Lipps (1906) believed human beings had a tendency to learn and comprehend the sentiments of other beings, whether animate or inanimate, of esthetic objects or even phenomena, when they contemplated them. In other words, he described a kind of enchantment felt by spectators as a kind of automatic and unthinking imitation of sentiments related to that which was observed.

Thus arose the German word Einfühlung, referring to a mechanism of perceptions developed by humans to contemplate works of art. Einfühlung is a form of capturing subjective observer properties whereby the observer projects herself into the object of art (CURTIS, 2009).

Based on the studies carried out by Lipps (1906), because the approach refers to intersubjective and interpersonal relations as well as esthetic experiences, empathy was not merely conceived of as an esthetic concept, but as a category of psychological and sociological nature, thus presupposing a mobilization of the self toward the other.

During the first decade of the 20th Century, Einfülung captured the attention of Wilhelm Wundt (1904) and Edward Titchener (1909), founders of structural psychology whose object of investigation was the structure of the mind. They were the first authors to deeply investigate Einfülung, and whose theory served as the basis for experiments on consciousness through introspection and as a parameter for the new science of psychology.

By the 1940s, few studies had contributed towards an improved elucidation of the concept of empathy. At the beginning of the 1950s, however, empathy began to be studied more in depth and applied to the field of psychology by Carl Rogers (1975; 1976), the American psychologist and developer of the Person-centered Approach. Rogers believed empathy was a human faculty that surpassed the expression of a reaction resulting from others´ behavior, comprising abilities developed from ties with others, defined as a multidimensional construct including three components: a cognitive one (perceiving the emotions of others), an affective one (experiencing the feelings of others), and a behavioral one (making others feel understood).

In keeping with this understanding that empathy makes the subject more sensitive to the perspectives and sentiments of others, Rogers (1975; 1976) promoted it as a strategy for first re-establishing the communication of the patient that had been interrupted with himself and then by re-establishing the patient´s communication with others, which had been harmed by this rupture. Thus, the author asserts that the ability to perceive, comprehend, and validate the feeling of others translates into a connection between the psychotherapist and the patient resulting in improved adherence to treatment protocols without relinquishing the objectivity that psychotherapy requires. In this way, empathy can represent a resource for use in psychoanalysis.

Various researchers used Carl Rogers´ theory to conduct more in-depth studies on empathy and developed a variety of methodological theories to aid in psychotherapeutic treatment. During the 1960s, Feshbach and Roe (1968) developed a test to assess empathy in children of six and seven years of age, the Feshbach Affective Situation Test for Empathy (FASTE), which remains widely used today. The test uses a response scale based on attributes ranging from more empathy to less empathy in which children were asked if they recognize and feel the emotions of others and whether age similarity or sex affected empathy levels.

Then, during the 1970s and 1980s, researchers set forth other scales designed to measure empathy. Davis (1980), for example, created an empathy scale called A Multidimensional Approach to Individual Differences in Empathy that assessed the cognitive, affective, and behavioral empathy of adults.

Empathy took on the character of gratuitousness in the action of human solidarity during the 1990s. The development of the empathy-altruism hypothesis, according to which the subject, motivated by concern for fellow well-being and compassion, mobilizes herself in the direction of others set forth by Batson (1991) is representative of this perspective. The empathy-altruism hypothesis posits that human behavior is not motivated by selfishness; on the contrary, relations are established by demonstrating a personal and genuine interest in the well-being of others. Thus, the subject sees others not as sources of information, stimuli, gratifications, rewards, and well-being in and of itself, but as a form of respecting and appreciating others.

The study of empathy also received contributions from Vigotski (1999), who made use of the term in the psychology of art to refer to a type of transfer of states of spirit from the observer into shapes, objects, and phenomena. He also used it within the field of literary theory to refer to the symbolic universe obtained by literature and the connection between the reader and literary characters, or even as the reader in the role of co-author when reading a text.

Since the decades of the 1980s and 1990s the concept of empathy has taken a new direction, one related to interpersonal intelligence, a concept derived from Howard Gardner´s Theory of Multiple Intelligences. In this theory Gardner (1995) developed the concept of intelligence no longer as synonymous with merely logical and mathematical ability, but as comprising multiple factors, including interpersonal intelligence, posited as the capacity to identify and understand the desires, emotions, and intentions of others, aimed at allowing more comprehensive adaptation to the social world and for effective social interactions. Studies into empathy making use of this perspective have enhanced understanding of the concept of interpersonal intelligence, a field of knowledge that recognizes empathy as a mobilizer of cognitive communication that captures and decodes information concerning social relations to formulate behavioral strategies according to the ends sought.

According to Daniel Goleman (1995), a brain and behavioral sciences researcher, having empathy is “actually hearing the feelings behind what is said” (GOLEMAN, 1995, p. 145, emphasis in original), as a type of social radar. He describes empathy as a human ability used to explore the minds of others and to capture feelings and thoughts through facial expression, tone of voice, and speed of speech, as well as pauses and other cues that help to infer what goes on in the minds of others. Goleman adds that this phenomenon requires two people to approach each other and results in unconscious cerebral activity causing them to speak and synchronize movements and postures. According to Goleman (2011), when this approach movement, which he refers to as a subtle dance, does not take place, people feel uncomfortable.

Thus, since its appearance in the context of art philosophy, the concept of empathy has been expanded into the fields of psychology, sociology, education, the neurosciences, and economics, among other areas. Current research also reflects this trend, embracing the concept on a broad level focusing on the formation of the individual and integral education. In keeping with the aims of the present work, the focus of interest concerning the potential of empathy is placed within the field of education. An investigation of this phenomenon with respect to the relationship between the student, the teacher, and knowledge will be discussed below.

Empathy in the Education of Youths and Adults

Interest in the theme of empathy as an attribute necessary for education professionals has arisen not only because of the significant relevance born by it; the concept has also received increased attention in the context of a segment of the population carrying the stigma of failure. Placing oneself in the position of others is not an easy task, and for some it is a practically impossible one. This task can become more difficult still when the “other” happens to be someone associated with a context of exclusion, as in the case of Youth and Adult Education (EJA) students.

Although empathy is specifically promoted in EJA in the DCN as a means for learning about the values and beliefs of “groups that curricula have failed to recognize for a hundred years or so under the mantle of formal equality” (BRASIL, 2013, p. 115, our translation), it is important to consider that this recommendation also represents a kind of a social utopia guided by the rights of all, in their diversity, and seeking to overcome social inequalities.

For the educator to act with a commitment to breaking the cycle of structural duality at hand and meet the emotional needs of students, they must adjust their behavior to the demands of a society in constant transformation. Such adjustment in teaching practices includes, among other actions, the use of dialog with students with respect to planned actions and modifying those plans according to the dialog; conceiving of curricular documents as orientation instruments that should be questioned and adapted to the students´ reality; and seeing the classroom as a space conducive to a plurality of values and knowledge sets. However, if there is no empathetic relationship, a lack of awareness of the other or understanding of the historicity of that subject, not only as an individual, but as an integral part of a circumstantial system, few of such actions will take place.

In the meantime, empathy can contribute toward overcoming the prejudice related to seeing the youth or adult student as a student of lesser value and prestige. That view creates a vicious circle interrupting the bond between teachers and students, and may cause teachers to see EJA classes as something to be avoided or merely as a means for fulfilling workload requirements.

Empathy is thus a central element in the educational process, one that should be cultivated and exercised both for teachers and students. For Goleman (2011), empathy can, in fact, be developed, for even people and animals that grow up with no social contacts possess the empathy mechanism, though they may not know how to use it due to never living with others and being given the chance to develop the capacity to learn and discern the signs of emotion that may surround them.

Methodological trajectory

To achieve the ends outlined above, a quali-quantitative field research study with descriptive aims was carried out through the application of a questionnaire among third year students of a Youth and Adult Education class of the Professional Education program at an Instituto Federal Fluminense campus. Only third year students were interviewed because by this phase in their educational journey the students have gotten to know most, if not all, of the teachers in the program, and thus have more significant insight concerning processes of empathy in this context.

The questionnaire was developed based on Carl Rogers´ theory on empathy as a multidimensional construct which includes cognitive, affective, and behavioral components. Recognizing that these three components interact in a reciprocal fashion, five closed and two open questions were included in the questionnaire.

The application of the questionnaire was preceded by two distinct steps. First, a message with a brief explanation about the applicability of the tool, along with one emphasizing the importance of responding truthfully to the questionnaire, was sent to the class´s WhatsApp group. Then, a link to the questionnaire was sent to the same WhatsApp group.

The questionnaire itself was composed of three sections. In the first section, respondents were asked to provide personal information such as name, email address, and telephone number. In the second section they were asked to sign a Free and Informed Consent Form (TCLE) that stated that all responses and personal information would remain anonymous, including the periods in which respondents were registered for study. Students also answered the closed questions in the second section; these involved a variety of circumstances related to a process of empathy between the teacher and student. In the third and final section, the students were asked to respond to the open questions dealing with specific situations in which a teacher´s behavior may have facilitated and/or compromised the learning of the respondent or a classmate.

The research subjects had been informed of a set deadline for completing the questionnaire and were asked to do so individually so that there would be no interference or influence on the issues addressed and to ensure the legitimacy of the results obtained.

Student reports

As mentioned, the respondents were final year students of a youth and adult education course. Because the institution used a class year grouping system, there were 59 students registered during the first year of study, 17 in the second year (a reduction of 71%), and only 9 in the third year (a further reduction of 47% between the second and third years). Thus, based on the initial number of registered students, a maximum of 15% of the original class would conclude the course and when the questionnaire was applied 85% had dropped out. These numbers had fallen significantly over the three years of the course, a fact that confirms the history of exclusion pertaining to this modality of students.

While this research sample, composed of 9 subjects, was small in relation to the quantity of students registered at the beginning of the course, it is intriguing and, indeed, representative of these students, who could be characterized as survivors. This is because these students submitted reports documenting the strategies they encountered for conducting interpersonal relations in the school setting when empathy aided in the creation of ties that could help students continue their studies until the conclusion of the course.

One can discern that the drop in the percentage of students registered was highly representative of the first year of study, a period considered “critical” by Vincent Tinto (2012, p. 5), for it is a time when “student success is still so much in question and still malleable to institutional intervention.” According to the author, the first year of study is particularly important because students need a significant level of support to maintain expectations and, above all, fulfill them (TINTO, 2012).

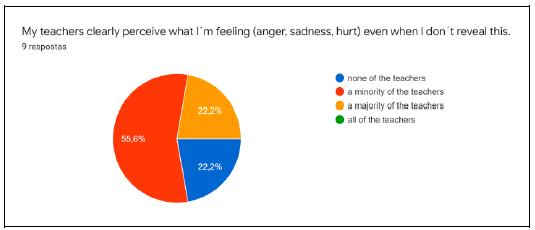

We will now analyze the results and student responses obtained through the application of the questionnaire. The second section of the questionnaire asked students if their teachers clearly noticed what they were feeling (anger, sadness, hurt, etc), even if they did not vocally express it, thus seeking to verify the first communicative dimension of empathy - the cognitive one -, in order to reveal whether teachers demonstrated the capacity to perceive what students felt.

As shown in Figure 1, 22.2% of the respondents asserted that none of their teachers noticed what they felt and that for 55.6% only a minority of the teachers did. These two percentages together, shown in Figure 1, amount to a total of 78%. This result indicates that a majority of the teachers did not establish an empathetic relationship with their students, as 78% of the teachers did not attain the first stage of the multidimensional construct of empathy. This stage corresponds to perceiving the feelings of the other (cognitive dimension), which precedes the act of experiencing the sentiment of the other (affective dimension), which, in turn, precedes that which makes the other feel understood (behavioral dimension).

According to Goleman (1995), in order to exercise empathy, the subject must establish rapport, i.e., increasing the capacity for becoming involved in an interactive relationship and, above all else, become detached from their own emotional programming in order to pick up on the other's signals.

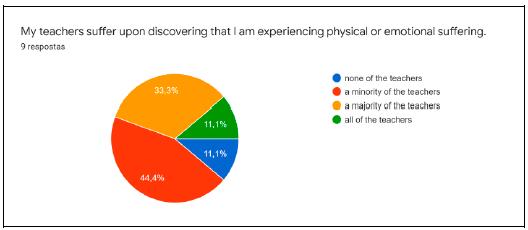

Figure 2 deals with the second communicative dimension of empathy - the affective one. By asking the students if their teachers suffer upon learning that the students are experiencing physical or emotional suffering, it sought to verify whether the teachers were sensitive to the problems faced by the students.

As Figure 2 illustrates, the total of the responses indicating that “none of the teachers” and “a minority of the teachers” were sensitive to the problems faced by students was 56%. Therefore, the results indicate that a majority of the teachers was not sensitive to the problems faced by their students.

Goleman (1995) asserts that the fact that everyone possesses an empathy mechanism does not mean that we all know how to use it. In other words, although this mechanism is understood as an unconscious and automatic circuit, because they did not have a high level of self-perception or self-knowledge, which are considered fundamental social abilities in the exercise of empathy, few teachers demonstrated the aptitude to use it. The same author adds that when such abilities are not displayed, that is, when a teacher does not recognize the importance and value of a student, it not only obstructs the creation of a connection between them, but also causes discomfort in the teacher-subject with respect to the student.

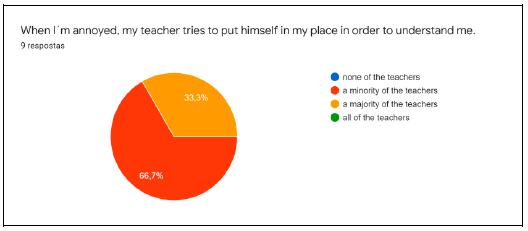

As the components of the multidimensional construct of empathy are mutually mobilized, Figures 3, 4, and 5 illustrate the behavioral dimension, which is preceded by the cognitive and affective components, and thus represents the very definition of an empathetic attitude

According to the results represented in Figure 3, 66.7% of the respondents stated that a minority of teachers tried to put themselves in the place of and understand the students. This shows that the majority of teachers do not understand their students, because there was also no active interest about what bothered them.

Given the importance of the presence of a teacher who takes an active and genuine interest in what happens to their students, it is useful to contemplate just what having empathy means. Empathy should not be confused with compassion or pity, even though these meanings share the common idea of displacing the subject from his or her comfort zone. A potentially distorted understanding of what empathy is may make the teacher try to satisfy a student´s emotional needs, for one reason or other, unrelated to the requirements of the given empathic situation. This is due to the fact that having empathy is different from having pity or being overly concerned for someone or even seeing that person as someone of lower value. When a student notices such a situation, it can lead to the deterioration of a teacher-student tie, when one exists, or impede the creation of one, when it does not. Empathy must be accompanied by balance, moderation, and integrity, and if this is not the case, the teacher-student relationship will generate distrust, or rather, artificial empathy (GOLEMAN, 1995).

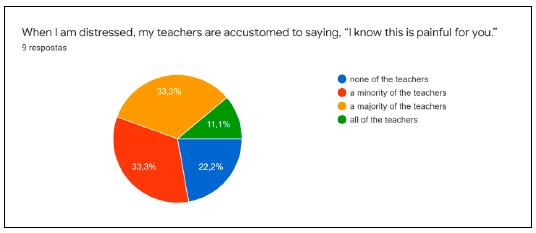

When students were asked if their teachers were accustomed to saying I know this is painful for you during moments of distress, the data represented in Figure 4 resulted.

One can observe that 22.2% of the respondents affirmed that no teachers were accustomed to expressing that sentence or one of a similar sentiment and that for 33.3%, only a minority of their teachers did so. When added together, these percentages represented in Figure 4 total 56%.

These results indicate that more than half of the teachers have difficulty establishing dialog, listening attentively, and personalizing interactions with their students, because this requires the teacher´s self-knowledge and self-acceptance. Because of this, dialog may require more effort by the teacher in the sense of being able to reveal themselves when they do not fully understand themselves. On this point, Olmos (2016, p. 28) asserts that “being in a relationship with the students engenders the need for the educator to know himself and to become aware of his capacity for self-transformation and empathy” (our translation). The author warns that “engaging in dialog requires an attitude of receptivity to the other and their thinking, not for transformation into something equal, but rather to achieve full knowledge of the other” (OLMOS, 2016, p. 28, our translation).

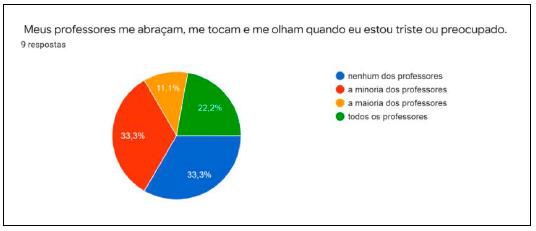

Starting from the observation that words cannot express as much as a look does and how empathy is impregnated with corporeality, Figure 5 illustrates the importance of body expression for comprehending the behavioral communicative dimension of empathy.

When students were asked if they were hugged, looked at, and if physical contact with their teachers was made when they were sad, 33,3% responded that no teachers displayed such behavior. These percentages totalled 67%. This data indicates that a majority of the teachers was not empathetic, because the body can demonstrate things that, at times, not even the subject is clearly aware of.

The teacher, as a professional that interacts with students on a daily basis, should establish a form of contact that transcends technical protocols as a means of establishing empathetic relations. Empathy can be expressed by the teacher in various ways, but physical contact provides comfort, human warmth, and proximity to the student. Physical contact allows the teacher to perceive the reactions that occur in her students and, in addition to being able to reflect on them, it alters the quality of the relationship between them and their level of empathy (GOLEMAN, 1995).

In order to further the objectives of our investigation into empathy, we will now turn our attention to an analysis of the responses associated with the open questions. The first open question asked the students to cite an instance in which a teacher´s attitude facilitated the learning of that student or that of a classmate. A review of the responses shows that only one student failed to report such a situation.

When a certain teacher used two types of explanations so that we could understand our chemistry subject matter (report 1).

Never giving up on a student (report 2).

When a teacher encourages us (report 3).

The teacher came near me to teach me (report 4).

The teacher explained the material various times so that we could learn (report 5).

Repeating what was said during class in a way that the student can understand (report 6)

Motivational utterances were always very important (report 7).

The teacher [...] suggested videos and went to the students´ desks whenever there was a question (report 8).

A review of the collected data reveals reports concerning alternative methodologies aimed at explaining course content, the teacher´s encouragement of and motivating students, interest in their learning, and physical approach of the teacher to the students. These situations reported in the first open question, without exception, were associated with empathy and thus provided evidence of fundamental behavior on the teacher´s part that facilitated student learning.

In the second open question students were asked to report a situation in which the teacher´s behavior may have caused a negative effect on the learning of the respondent or that of a classmate. The responses reveal, once again, that only one respondent failed to cite such a situation.

A teacher yelled at a classmate during class because she had answered the questions written on the board incorrectly, intimidating the class from participating in such activities (report 1).

Saying that a student isn´t capable (report 2).

When they don´t care when students have failed to understand the subject matter (report 3).

She asked the class to study all of the content, but gave the same test again (report 4).

The teacher asked about content on the test that wasn´t covered in class (report 5).

Ignoring when a student asks a question about the class (report 6).

During the first year a teacher incorrectly recorded my official grades and ever since neither the coordinators nor the teacher have been able to correct the record. I still have a low grade without really having received one (report 7).

A lack of interest in giving class, saying “I come here to give class, but if you don´t learn, it´s not my fault. I have to continue following the curriculum and you all have YouTube at home” (report 8).

Based on these results, one can observe situations in which there are: a) a demonstration of a lack of confidence, commitment, and respect on the teacher´s part concerning the planning and performance of testing, as well as the recording of grades; b) teacher attitudes that lower student motivation; c) demonstration of a lack of motivation by the teacher himself to teach; d) demonstration of a lack of interest on the teacher´s part concerning student learning; e) disrespect and intimidation on the teacher´s part designed to inhibit students from asking questions about the subject matter; and f) teacher attitudes that blame students and demonstrate a lack of responsibility for student learning. These reports in response to the second question, without exception, were associated with a lack of empathy and thus provided evidence that a lack of empathy in teacher-student relations harmed the teaching and learning process.

These reports illustrate a curious situation, one that was reported twice by different students, albeit in response to different questions. One narrative was elicited by the question about situations in which a teacher attitude may have harmed the learning of the student or a classmate, which will be referred to here as narrative A; the other was a report concerning situations in which a teacher attitude may have facilitated the learning of the student or a classmate, referred to here as narrative B. Thus, the same occurrence containing the same content served to illustrate both a positive and a negative attitude.

The segment from narrative A was a certain teacher, on the first day of class, started using his catchphrases: nothing is so difficult that I can´t make it worse. If you were at the edge of a cliff, I´d be there to give you a push. This report provides evidence of a teacher´s threatening, physically aggressive tone that was considered negative by the respondent. The same content in narrative B, however, read He frightened some students with his tough manner, but I had a good opinion of him and knew that below that spiny outward appearance there was an incredible human being. This report reveals that the respondent not only did not disapprove of the teacher for his tough manner, but, on the contrary, deliberately sought to diminish the negative effect of his spiny outward appearance upon asserting that it was only an appearance and that, in reality, he was an incredible human being. Thus, when analyzing the object-teacher, the subject-respondents characterized him based on their own subjectivities which, in turn, were influenced by their personal ideologies and beliefs.

Another narrative A passage was he said that if you had no way of exercising a determined activity or task that others carried out, maybe you could be successful in life in other ways and cited people that had won in life without using mathematics or literacy. Here one can see that the teacher did not believe in the potential of his students for studies and academic education, nor that they could succeed in life with a job that was not subordinate, that was focused on education that prepared or qualified them for work. In other words, according to this student-respondent´s perspective, the teacher´s narrative revealed prejudice against the youth and adult students as a group. He had internalized the perspective that the educational system reproduces spaces of social struggle in which while the ruling class is educated to continue as rulers, the lower classes will continue as such, and that because nothing could be done to change that, people should simply accept it.

Another segment from narrative B reads, he said that because many students did not have sufficient commitment, not even half of the class would make it to the end of the course and that he was able to see and perceive which students seriously wanted something from the course, and I agree with him. This passage reveals that this student-respondent, as in the case of many others, did not fault the teachers for student failure and instead attributed it to a lack of commitment on the part of their classmates. For this student, recognizing that the teacher was wrong and that failure was not due to a lack of commitment of his classmates would be like admitting that the school is undemocratic and indeed is a tool of oppression. It would be an admission that the school is no place for him. Furthermore, assuming one´s place at the side of the oppressed is an admission that one is like that person; it is easier to stand beside the oppressor because then you will not be victimized by him and will not have to deal with this oppression. This passage thus illustrates the dialectic nature of subjective perspectives, as well as how one´s self-awareness can interfere with interpretations of reality.

Another narrative A passage reports as the number of students in the class shrank considerably, he guaranteed that the survivors would not receive failing grades, and that is what happened; no one had to take extra classes or retake tests; we all passed even without understanding the material. Thus, the fact that the teacher gave all of the students passing grades did not translate into a positive opinion for him, since from his perspective students were being passed without deserving it. The act of passing the entire group, which might have been considered positive under other circumstances, created distrust and the suspicion it was accompanied by manipulation, as well as a certain degree of indignation that the passing grade was unjustified due to many students´ failure to develop an adequate grasp of the material.

However, in the narrative B passage in addition to teaching, he recommended videos and went to the students´ desks whenever there was a question, the student-respondent is clearly stating that the teacher fulfilled his role as an educator. There was clearly learning taking place in this case due to the teacher´s having taught, recommended supplementary study videos and, above all else, gone to student desks to provide individual explanations and answer questions, demonstrating dedication to his students.

The differences in perspective between the two narratives are more understandable when the two types of relations established between the actors involved are analyzed. It is evident that the empathetic communication established by the student respondent of narrative B resulted in greater understanding and acceptance, on his part, of the manner in which this teacher developed his teaching activities. This is in contrast to the teacher of the student who reported narrative A, who did not establish such empathetic communication, and therefore did not benefit from the same acceptance and understanding as the one referred to in narrative B.

An analysis of these narratives shows that the empathy observed in narrative B and the lack of empathy in narrative A was fundamental for understanding the fact that these narratives were elicited by different questions. These narratives also revealed that when an empathetic relationship is established, as in the situation reported by narrative B, the interpersonal relations between teacher and student not only preserve the humanity of that relationship, but contribute towards learning.

In general, the establishment of empathy ends up being one more task to be performed by the teacher, as he is the one who must communicate to the students that their emotions and feelings are understood. However, these reports show that questions involving empathy can point in different directions. In this case, the student took the initiative in establishing empathy, as he was the one who communicated to the teacher that the latter´s emotions and feelings were understood, thus showing that despite the teacher's lack of empathy, students themselves seek ways, through empathy, to remain in school.

Final considerations

The reflections on empathy in an educational context based on reports by Youth and Adult Education students indicate the existence of relational and behavioral problems that should neither be ignored nor considered isolated occurrences. Developing and enriching empathetic relations in school, establishing them as the right upheld by the PCN and DCN, and translating them into effective actions must lie at the core of the educational process.

The student reports in this study have provided evidence that within an environment that does not foster empathy, students seek new avenues of dialog in order to establish empathetic relations and remain in the school even though such avenues require that the teachers, and not themselves, become the center of the educational process. The results indicate that empathy, or a lack thereof, interfered in the development of more positive or negative attitudes in relation to themselves and, consequently, in relation to learning. Finally, student initiatives to create empathetic ties point to new avenues of empathetic communication in which students themselves become active agents of transformation for their own lives and territories.

REFERENCES

BATSON, Charles Daniel. The altruism question: toward a Social Psychological Answer. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum, 1991. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Média e Tecnológica. Parâmetros curriculares nacionais do Ensino Médio - Linguagens, Códigos e suas Tecnologias. Brasília, 2000. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/linguagens02.pdf. Acesso em: 12 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Fundamental. Diretrizes curriculares nacionais da educação básica. Brasília: MEC, SEB, DICEI, 2013. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=15548-d-c-n-educacao-basica-nova-pdf&Itemid=30192. Acesso em: 12 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Parecer CNE/CEB 11/2000 - Homologado Diário Oficial da União de 19/7/2000, Seção 1, p. 14. Brasília, 2000. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/secad/arquivos/pdf/eja/legislacao/parecer_11_2000.pdf. Acesso em: 12 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

CURTIS, Scott. Einfuhlung und die fruhe Deutsche Filmtheorie. Traduzido por Francisca Kast e Joseph Imorde. In: CURTIS, Robin; KOCH, Gertrud. Einfuhlung. Zu Geschichte und Gegenwart eines asthetischen Konzepts. Munich: Wilhelm Fink, p. 79-104, 2009. [ Links ]

DAVIS, Mark. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, The University of Texas, Austin, v. 10, p. 85-104, 1980. [ Links ]

FESHBACH, Norma Deitch; ROE, Kiki. Empathy in six-and sevenyear-olds. Child Development, University of California, Los Angeles, v. 39, p. 133-145, 1968. [ Links ]

GADAMER, Hans-Georg. Verdade e método: traços fundamentais de uma hermenêutica filosófica. Tradução de Flávio Paulo Meurer. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2008 [1986]. [ Links ]

GARDNER, Howard. Inteligências múltiplas: A teoria na prática. Tradução de Maria Adriana Veríssimo Veronese. Porto Alegre, RS: Artes Médicas, 1995. [ Links ]

GOLEMAN, Daniel. Inteligência emocional: a teoria revolucionária que redefine o que é ser inteligente. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 1995. [ Links ]

GOLEMAN, Daniel. Inteligência social: o poder das relações humanas. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2011. [ Links ]

LIPPS, Theodor. Empathy and its development. Edited by Nancy Eisenberg e Janey Strayer. Cambridge: Cambridge Studies in Social e Emotional Development, 1987 [1906]. [ Links ]

OLMOS, Ana. Empatia: algumas reflexões. In: YIRULA, Carolina Prestes (org.). A importância da empatia na educação. São Paulo: Instituto Alana, p. 22-29, 2016. Disponível em: https://escolastransformadoras.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Empatia-na-educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o-Escolas-Transformadoras-Brasil.pdf. Acesso em: 12 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

ROGERS, Carl Ransom. A terapia centrada no cliente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1975. [ Links ]

ROGERS, Carl Ransom. Tornar-se pessoa. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1976. [ Links ]

SMITH, Adam. Teoria dos Sentimentos Morais. Tradução de Lya Luft. Revisão Eunice Ostrensky. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2002 [1759]. [ Links ]

TINTO, Vincent. Enhancing student success: taking the classroom success seriously. The international journal of the first year in higher education, Syracuse University, New York, United States of America, v. 3, n. 1, p. 1-8, 2012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v2i1.119. [ Links ]

TITCHENER, Edward Bradford. Lectures on the Experimental Psychology of the Thought Processes. New York: The Macmillan & Co, 1909. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev Semenovich. Psicologia da arte. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1999. [ Links ]

WUNDT, Wilhelm. Principles of physiological psychology. Translated from the fifth German edition by E. B. Titchener. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co, 1904. [ Links ]

Received: June 01, 2021; Accepted: May 01, 2022

texto en

texto en