Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensino em Re-Vista

versão On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.30 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 01-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v30a2023-3

Articles

Teachers' beliefs about Economic Literacy: challenges and perspectives in the context of Early Childhood Education

1Mestre em Educação, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém, Pará, Brasil. E-mail: nso.olyveira@gmail.com.

2Doutora em Psicologia, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém, Pará, Brasil. E-mail: iranilauer@gmail.com.

3Mestre em Educação, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém, Pará, Brasil. E-mail: madaniela_w1202@hotmail.com.

Beliefs guide teaching practices, including in the context of economic literacy. This study aimed to understand the beliefs and practices of teachers working in early childhood education on economic literacy - AE, its acronym in Portuguese. Two teachers, who teach children between 4 and 5 years old at a Municipal Child Education Unit in Santarém - Pará, participated in the research. A semi-structured interview script was used and analyzed using the method of the Discourse of the Collective Subject - DCS. The results indicated an incipient knowledge about AE, because the beliefs expressed about AE were limited to common sense; practices limited to dialogue without intentional and systematized actions were evidenced. It was concluded that the insertion of the theme is necessary into the school curriculum; it is needed to invest in teacher training, in order that beliefs can be built for the mission of economic literacy, not only pertaining to the family, but that they assert the professional responsibility of an integrated curriculum, contributing to the integral development of children.

KEYWORDS: Economic literacy; Education; Beliefs

As crenças guiam as práticas docentes, inclusive no âmbito da alfabetização econômica. Este estudo objetivou compreender as crenças e práticas de docentes atuantes na educação infantil sobre alfabetização econômica-AE. Participaram duas docentes, que atendem crianças de 4 a 5 anos de um Centro Municipal de Educação Infantil, em Santarém - Pará. Utilizou-se roteiro de entrevista semiestruturada e analisou-se mediante a técnica do Discurso do Sujeito Coletivo - DSC. Os resultados apontaram para um incipiente conhecimento sobre AE, pois, as crenças manifestadas sobre AE limitaram-se ao senso comum; evidenciaram-se práticas que se limitam ao diálogo sem ações intencionais e sistematizadas. Infere-se que uma das premissas do presente estudo reside na importância da inserção da temática AE no currículo escolar, contribuindo na ampla exploração das crenças e práticas docentes. Para tanto, o investimento na formação docente seria necessário, contribuindo, portanto, no desenvolvimento integral da criança.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Alfabetização econômica; Educação; Crenças

Las creencias guían las prácticas de enseñanza, incluso en el contexto de la alfabetización económica. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo comprender las creencias y prácticas de los docentes que trabajan en educación infantil en alfabetización económica-AE. Participaron dos maestros, que atienden a niños de entre 4 y 5 años en un Centro Municipal de Educación Infantil en Santarém - Pará. Se utilizó un guión de entrevista semiestructurado y se analizó mediante la técnica Discurso del sujeto colectivo - DSC. Los resultados apuntaban a un conocimiento incipiente sobre AE, porque las creencias expresadas sobre SE se limitaban ao sentido común; Se evidenciaron prácticas que se limitan al diálogo sin acciones intencionales y sistematizadas. Se concluye que la inserción del tema es necesaria en el currículo escolar; Es necesario invertir en la formación del profesorado, para que se construyan creencias para la tarea de la alfabetización económica, no solo pertenecientes a la familia, sino que reclamen sobre sí mismos la responsabilidad del trabajo integrado en el currículo, contribuyendo al desarrollo integral de la educación de los niños.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Alfabetización económica; Educación; Creencias

Introduction

The school has as its primary social function to prepare students to act objectively on reality, providing them with a citizenship education enough to make them intervene actively in the social environment where they live. The school environment is configured as a place conducive to the manifestation of a complex set of interpersonal relationships, in which each of its players carries a wide spectrum of representations, theories, beliefs, and values that directly influence the achievement of actions, planned or not, that occur in this environment.

In the present study, teachers' beliefs are the central point of reflection. Discussing teachers' beliefs and the implications for the teaching-learning process, Paiva and Del Prette (2009 p.76) defined them as "... ideas and convictions about issues related to education that reveal themselves, consciously or not, in teachers' actions. According to these authors:

Beliefs influence the teaching-learning process by mediating pedagogical decisions and the interactions that teachers establish with their students, acting as a filter that leads them to interpret, value, and react in different ways to the progress and difficulties of their students, and may even induce the actual behavior of these students toward their expectations (PAIVA; DEL PRETTE, 2009, p.76).

Teachers' beliefs, that is to say, the ideas and convictions that teachers have about some issue, have great importance in their practices and these, therefore, intervene heavily in the education and development of students. In this sense, studying them in a systematic and targeted way to the teaching activity becomes essential for the promotion of actions that aim at the citizenship and integral formation of the audience.

The interest in teachers' beliefs has aroused researchers to understand human development from the perspective of beliefs and practices and their relevance to the integral formation of the student in their social, emotional, cultural, and even economic aspects. Thus, there is a need for a conception of the human being that considers the cultural, psychological, and practical aspects of the agents involved in the child development process, once the child will get direct influence to the constitution of their own formation and identity.

The understanding of teachers' beliefs and practices was discussed and studied, taking into account the educational domain. In recent years research on beliefs has been taken as relevant in studies about teachers' paradigms (SOARES; BEJARANO, 2008).

Rockeach (1981), suggests that the number of beliefs an adult owns is absolutely innumerable. There are thousands of related beliefs, for instance, to what is true or false, beautiful or ugly, good or bad with respect to the social and physical world in which the person is. For the author, beliefs are organized into systems within human mind and have descriptive and measurable structural properties, being observable by human behavior, and thus cannot exist outside a belief system.

Rockeach (1981) understands that beliefs can be both conscious or not and that they cannot be observed directly, however it is possible to infer them from what people speak or do. They may also be acquired directly or indirectly. The author points out that all beliefs necessarily consist of three components: cognitive, since it evaluates knowledge as true or not; affective, because they have the ability to evoke effects of various intensities since beliefs predispose specific responses. They can be considered to be propositional representations of the world.

Soares and Bejarano (2008, p. 55) believe that "knowing, discussing and understanding beliefs helps to broaden discussions in the field of education". These authors point out that research has found a relationship between school failure and low expectations of the teacher regarding the academic performance of their students, especially when they are from less favored social classes. However, research into the economic literacy of children and the beliefs of teachers is still under way.

According to Webley (1999) there is a large body of literature on children’s understanding of the world of economics. Nonetheless, the vast majority of these studies are based on a cognitive interpretation of development, which predicts what stages children must go through in order to reach a certain level of economic thinking.

According to Lauer-Leite (2009), the study of these themes has been focus of interest both in the areas of developmental psychology (BERTI, 1992); and more recently in the field of economic psychology (BONN; WEBLEY, 2000; FURNHAM, 1999; PUGH; WEBLEY, 2000; WEBLEY, 1999)

Within the broader concept of economic socialization, the term "economic literacy" is defined as "a set of concepts, skills and attitudes that allow the individual to understand their local and global economic environment, and that lead them to make efficient decisions, according to their financial resources" (DENEGRI et al., 2005).

According to Denegri et al. (2005), economic literacy can be understood as a potential tool that aims to provide broad public participation in the debate and consolidation of economics, promoting political alternatives and stimulating community actions. It is in this aspect that the study of themes like this, in addition to strengthening the idea, is configured as an important argument in favor of the implementation of this theme in schools.

As Araújo (2009) points out, it is essential to draw strategies that provide, from an early age, the construction of more conscious economic relations. According to the author it is important to understand that the improvement in people’s living conditions happens through social inclusion, political and financial awareness, as well as through reflective actions that stimulate greater social participation.

It is not easy to understand the world in its economic and social systems. In a society marked and based on the foundations of capitalist logic, in which the discrepancy between human wealth and poverty that characterizes the life of a large part of the population reaches extreme and even unbearable levels, understanding and acting on this conjecture constitute an arduous mission in its most distinct aspects.

Yet, in order to understand the world of economics, it is important that the individual develops a systemic view of the economic social model in which they are part of, along with the need to develop skills, attitudes, habits, and behaviors of rational and efficient consumption, as stated by Denegri et al. (2005).

For Ortiz (2009 p. 107), "working with economic education represents an important theoretical opening that is foreseen as something very fertile in the formation of the citizen, which will benefit not only the subject, but the society as a whole". She also argues that, for the proper implementation of an economics education in schools, educational interventions are necessary to expand and disseminate economic knowledge in children, aiming at the acquisition of new skills to learn how to deal with money, becoming conscious and prepared adults to manage their own resources.

It is possible to find in some studies (DE CASTRO; DE CASTRO, 2021; SILVA; POWELL, 2015) the terminologies "economic education" and "financial education" as synonyms, with no conceptual distinction between them. On the other hand, the terms are shown separately in some studies and organizations such as the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2005).

The term financial literacy is used by the OECD (2005) and is defined as:

[...] the process by which consumers and investors improve their understanding of financial concepts and products and, through objective information, instruction and/or advice, develop the skills and confidence to better understand financial risks and opportunities, and so make informed decisions that contribute to improving their financial well-being (OCDE, 2005, p.13).

Also, according to the OECD, financial education is responsible for helping consumers to manage their income, save and invest, avoiding victims of fraud. Financial education can be explained as learning to take care of money.

Regarding economic education, Aragão and Lautert (2021) remind that it refers to:

[…] an educational action that aims to develop in children and young people the basic notions of economics and consumption in order to help develop awareness, criticality, responsibility and solidarity when it comes to economic situations. Its assumption is that from the teaching of these basics, students can build strategies for making relevant decisions that help them build a position in the consumer society as conscious, critical, responsible and sympathetic people (ARAGÃO; LAUTERT, 2021, p.5).

It is noted that both the definition of financial education and economic education are focused on learning how to spend, invest money, in short, to know how the world works according to its resources, the availability of these resources and the interaction of the available resources. In this sense, the conceptual limit between economic and financial education according to the definitions of ODCE (2005) and Aragão and Lautert (2021) seems vague.

Reference researchers in the area of Economic Literacy (ARAÚJO, 2009; CARVALHO, 2016; DENEGRI C. M., 2010; AMAR, A. J. et al., 2002; LAUER-LEITE et al., 2010; ORTIZ, 2009) have been interested in understanding how children learn about economic concept, stages of development of economic thinking, how money can affect the behavior of the child and also identify and understand the existence of models that come to explain the experiences that the human being establishes with economic issues. It can be noted that the discussion that has most interested researchers in the field covers aspects of economic literacy and that definitions of the terminology "economic education" and "financial education" have not received attention.

Under such complexity, studies that discuss not only the role of the school in the perspective of economic and/or financial education, but also that discuss concepts and definitions of the terms economic education and financial education become essential.

Regarding the term economic education, it is noted that economic psychology uses it, in contrast, the term financial education appears to be used by institutions and official documents such as the Common Core Curriculum, World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The lack of agreement and conceptual imprecision regarding the use of terms, may generate conceptual misunderstandings, affecting the exercise. Thus, the present study aimed to characterize the beliefs and practices of early childhood education teachers about economic literacy.

Methodological path

This qualitative and descriptive study was carried out with teachers of early childhood education in the city of Santarém-Pará in a Municipal Children's Educational Units that assists children with socioeconomic vulnerabilities. The objective of this study was to respond to the economic literacy practices of early childhood education about economic literacy teachers.

To this end, the problem to be investigated was to know teachers' beliefs and practices. The general objective was to characterize the beliefs and practices of teachers of early childhood education about economic literacy and specifically to know what teachers think about the term: economic literacy and identify teaching practices aimed at economic literacy.

Based on the literature in the area and according to the aims of this study, for data collection, an interview script was created and named: beliefs and practices of Economic Literacy consisting of 6 questions. The interviews were completed individually and the scenario questions were used as a guide for the interview and are presented below:

1: - What comes to your mind when you speak about economic literacy? What do you understand when talking about this term? 2 - For you, the term economic literacy encompasses what aspects related to financial issues? 3 - What do you think about children being educated about economic issues such as money, savings? Why? 4 - In your opinion, who should take on the task of economic guidance of children? Why? 5 - Tell us what you think about working with themes related to economic literacy in the classroom, 6 - In what way do you think this theme can contribute to the personal and socioeconomic development of your students?

The data collection material was analyzed using the Discourse of the Collective Subject - DSC technique, which is a proposal of "organization and tabulation and organization of qualitative data of verbal nature, obtained from statements...", developed by Lefrève and Lefrève (2005, p. 15-16). The choice for this technique was made because it is a technique that analyzes a specific professional group, describing both beliefs and practices, aiming at the apprehension of the participants' thoughts as our object of investigation.

The DSC is made of the use of methodological figures that separate the speeches into key expressions (KE), which are pieces, excerpts or literal transcriptions of the speech, which reveal the essence of the statement, and then into central ideas (CI). They reveal and describe in a synthetic, precise and reliable way, the meaning of each speech analyzed and each homogeneous set of CEH. According to the creators of this analysis technique, the collective thought is seen as a set of speeches about a given theme, and the DSC is the beacon that illuminates the set of semantic individualities that make up the expression of the social imaginary present in the speech, that is, it is some form or an expedient intended to get the community to speak directly (LEFÈVRE; LEFÈVRE, 2005, p. 16)

Results and Discussion

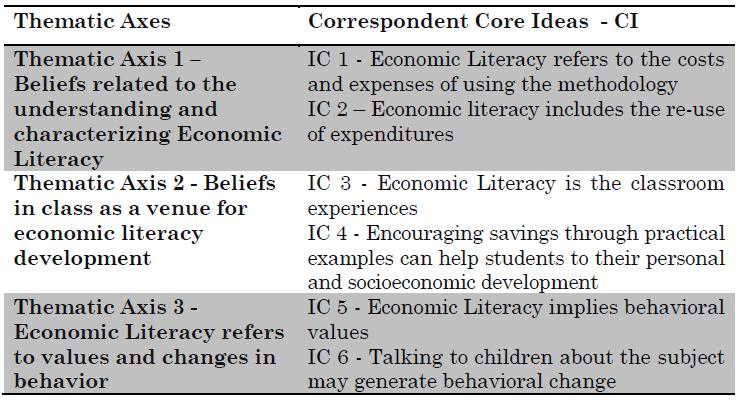

The Central Ideas that emerged from the analysis of the interviews showed points of convergence, since the questions used in the script presented some intersection points or even some connection between them, which led to the production of answers with similar semantic contexts, that is, similar answers on the same theme. Through the DSC 6 core insights were generated.

Thus, categorizing the CIs in Thematic Axes was chosen, enabling a better discussion and analysis of the speeches. To that effect, three (3) thematic axes will be presented and discussed, as shown in Figure 1.

Source: self-elaboration (2019).

Figure 1: A core set of thematic ideas around economic illiteracy beliefs

Thematic axis 1 - beliefs about the understanding and characterization of economic literacy, as shown in the table above, after the analysis of the material through the DSC technique, pointed out two (2) central ideas that had complementary speeches, reflecting the teachers' beliefs about what the term Economic Literacy means, as follows:

KEY IDEA 1: "Economic literacy refers to the costs and expenses to work on the methodology. It is about cost, about what to work on, what to bring to the classroom that can be beneficial to the children, because when I hear 'economic', in my opinion, it is about money, about what is going to be spent, but it is the part of the money that will give to work the methodology. It is investment in what I am going do.

This speech demonstrates the belief of teachers on economic literacy and resembles the propositions of Fermiano and Cantelli (2012), which underline that the process of economic literacy must encompass the most basic and different economic and financial concepts that exist in society, like consumption, spending, saving, laws of supply and demand, the value of money and interest, concepts that allow us to understand the economic world and interpret the events that affect it directly or indirectly, enabling us to make rational decisions and have control over its economic future, that is, such concepts are basic premises in understanding world of economics.

Based on the considerations of Fermiano and Cantelli(2012), it is verified that CI 1 it demonstrates an understanding of some of the assumptions suggested by the authors, since it highlights a certain concern with the expenses that must be carried out simply for the fulfillment of the task of educating, using innovative methodology and with varied resources that need to be acquired for such purpose, as it turns out in the following excerpt: "because when I hear economic 'in my opinion, it is about money, about what will be spent, but it is the part of the money that will give to work the methodology. It is a matter of investing in what I’m going to work on " (our emphasis).

It is worth noticing that from CI 1, it is still possible to infer the existence of a belief that Economic Literacy is related to the teaching methodologies used in the classroom. As a result, it appears that the participants' belief in economic literacy has diverged from the economic literacy process mentioned by Fermiano and Cantelli (2012).

The speeches about what teachers of early childhood education think about economic literacy have shown to be typical of knowledge that is based only on common sense, with no coherent approach to the theoretical-scientific precepts related to the theme studied here.

Within this way of thinking, it is verified that CI 2 demonstrates an intrinsic relationship with Central Idea 1: CENTRAL IDEA 1: "The term economic literacy encompasses the reuse of expenses" When I have my methodology, sometimes it is not necessary to spend so much, I can reuse that part that I spent and invest in something else that I can enjoy.

The emphasis in CIs 1 and 2 demonstrates that, according to the participants' understanding, Economic Literacy coverss the use of their own financial resources to be applied in the development of the teaching practice, the acquisition of material resources for the development of the class, as well as the reuse of these materials and/or educational resources in different times of teaching practice and in various activities. By saying "when I have my methodology", the participant refers to the practice of teaching, and its teaching strategies that, in a traditional conception of education, is understood as a standardized set of procedures designed to transmit universal and systematized knowledge (MANFREDI, 1993).

In this sense, it is important to highlight the propositions of Anastasiou (1997, p. 95), when referring that the act of teaching encompasses "a task that includes an intentional use (something that someone is intended to do, therefore, with explicit goal) and a successful use (successful result of action)".

Accordingly, for the accomplishment of teaching, it is important that this act also includes a set of efforts and practical decisions that are reflected in proposed paths, that is, in the methodological options that are adopted by teachers throughout their professional performance.

Denegri et al. (2005, p. 89) teaches us that economic socialization is a "learning process of interaction with the economic world through the internalization of knowledge, skills, strategies, behavior patterns and attitudes about the use of money and its value in society.

In a broader sense, as in the case of economic socialization, one can infer a timid relation of the discourses that emerged within this axis with the concept interposed by Denegri et al. (2005) Since it is manifested in them a certain concern with the use of money and its application in the activities to be carried out in the classroom, this moment is verified the attribution of a social value to money as a useful mechanism in the implementation of the teaching practice.

Hence, it is perceived that there is a closer approach of these discourses with aspects related to the process of Economic Literacy. Also, it is important to realize that the belief present in the discourses that emerged is basically focused on the teaching revealing, a priori, an understanding of the subject that places the child in a secondary and random environment within the process of Economic Literacy, being therefore affected somewhat indirectly in this process.

In an interventional study that aimed at describing the differences in levels of understanding of economic literacy in a sample of 167 students in the pedagogy course, Silva (2008) found significant differences following educational economic intervention with participants, demonstrate the effectiveness of this type of intervention, as it had resulted significant changes in the literacy levels of theses student, their consumption habits and behavior and their attitudes towards indebtedness, in addition to having contributed to a process of becoming aware of the economic knowledge with which they relate every day.

What can be inferred from the study above and its approach to the data present in the discourses presented as DSC 1 and 2, is that there is a need to include in the curriculum of teacher training courses the basic premises about economic literacy, contributing to their own personal training and in vocational training and future practices as education professionals, since the lack of more formal and systematic knowledge in relation to the subject became noticeable from the present study, as seen in the Discourses presented here.

In this matter, it is important to consider that it is crucial to implement in pedagogy courses the precepts of Economic Education, which according to Araújo (2009), aims to provide children and young people with the basic notions of economy and consumption, showing them strategies that will contribute to their direction in a range of daily situations, so that they can position themselves in a consciously, critically, responsible in face of the dilemmas and challenges that permeate the different nuances of the postmodern way of life. Hereupon, it is from a formation focused on the promotion of economic education in future educators that one can broaden the perspectives about the dissemination of these concepts among the children who will pass through the lives of these professionals.

To conclude discussions about this thematic axis, it is important to mention that it was noticeable the existence of a considerable superficial understanding regarding the use of the term "economic literacy" by the participants of this study. Consequently, Denegri et al. (2005) defines economic literacy as a collection of concepts, skills and attitudes that help people understand their economic environment, both locally and globally, and whose set of information will lead them to make assertive decisions regarding their needs, according to the financial resources available to them. As a result, based on this definition, participants may not fully understand what economic literacy actually is.

The second Thematic Axis - Beliefs about the classroom as a space for the development of Economic Literacy, synthesized the understanding that the classroom is a space conducive to the development of the theme, through "classroom experiences" and the "encouragement of saving through practical examples", as shown in the CIs presented in the sequence and their respective CSDs:

Also, as part of the thematic axis 2, the second central idea was: "Economic literacy is the experiences in the classroom", which can be illustrated by the following speech: "Economic Literacy is the experience that we work day by day in the classroom, and often even do not know if I am doing".

The Discourse reveals that Economic Literacy is understood as the very experience in the classroom, which is still materialized intuitively and unpretentiously by teachers, as you can see in the speech "and often even do not know if I’m doing".

Faced with this understanding it is valid to resort to the propositions of Sadalla; Saretta and Escher (2002), when they state that teachers' beliefs have a direct influence on several aspects of the teaching-learning process. They also state that each and every act of teaching results from a decision that the teacher makes analyzing the available elements in his or her training and performance, whether this decision is conscious. According to (Sadalla et al., 2005), it is worth noting that it is based on individual values and personal and professional beliefs that teachers make the necessary changes in the way they teach, that is, they include or exclude elements of their practice based on demands that arise during the teaching process itself. The author also argues that teachers' values and beliefs represent important factors in the teaching-learning process, since they influence the selection of contents to be taught, teachers' decisions regarding students' learning, and how to assess this learning or not.

As a result, we can deduce from the discourse that there is a predisposition to a closer understanding of the theory of economic literacy, since it was evident through the speech, even if unintentionally, that of the activities developed in the classroom experience there is a practical manifestation of working on topics inherent to the theme, as can be seen from the second central idea of this axis: "The encouragement of saving through practical examples can contribute to the personal and socioeconomic development of students," according to the CSD below:

"In the classroom, unplanned situations may happen, so I invent a situation, and then I make up my lesson plan, so I change what I had written in the notebook, and I make up another one, in light of what was discussed, what was developed. I use the example of the jars, which for me is very good, because any coin they don't throw anymore, they put it in the safe, they are encouraged to save”.

It is christal clear that this speech shows that there is a concern on the part of the participating teachers in relation to the socioeconomic development of the children, since through the unplanned situations that occur in the classroom, often arising from the interaction between children, the teacher takes advantage of such situations to modify what was scheduled in her lesson plan and take advantage of the event to teach children encouraging them to save money.

Additionally, with regard to the social and educational skills of these teachers, Del Prette and Del Prette (2014) highlight some skills considered relevant in conducting the teaching-learning process that maintain a direct relationship with the results shown in the discourse. Among these skills, these authors emphasize: the teacher's creativity in promoting diverse situations of educational interactions, the very modification of practices as a result of the students' performance, the observant and analytical look, always attentive to the progress achieved, in addition to acting as an anchor in the search for solutions to problems as well as in the presentation of new challenges to their students.

It is verified that teachers use didactic-pedagogical resources as an invention of stories that involve the act of saving, and even through situations of the child’s own family routine, since the teacher reports encouraging her students to keep their pennies in the pots received free of charge in the purchases of cooking gas made by the families, as extracted from the transcript of the interview, highlighted below: "Here in the classroom, I invent a situation, I say that my son, my daughter they have a piggy bank, like this from... "Who ordered the cooking gas and it was given a small pot so it is to put a penny? ".

For that reason, starting from a routine situation that occurs in the homes of most Brazilian families (buying cooking gas), she reports the creation of hypothetical situations that help children understand the importance of saving money, demonstrating creativity in the process of conducting situations that provide a favorable environment for the children's development.

In this regard, such discourses meet the propositions of Araújo (2009), by indicating that economic literacy includes the interpretation of situations that can directly or indirectly affect the financial life of people, as well as can assist families in financial decisions that are made daily, affecting their lives and those around them, and in this regard, children also receive influences that can benefit or contribute negatively to the development of their economic thinking.

For this reason, it seems reasonable to state that teachers are playing the role of influencers in the socioeconomic development of children, contributing directly to their personal growth, although in an incipient and still volatile manner. Such understanding may be summarized according to the propositions of Laroca (2002, p.42), when he states that the work field in which teachers operate is full of dynamism and heterogeneity, and because of this their methodological strategies cannot be stable, on the contrary, they need to be constantly in a movement of creation and recreation, even if in the form of timid or desperate rehearsals and attempts before a very complex reality, which often not even the teacher himself can clearly grasp, but that are ahead of him waiting for decisions on which he must take full responsibility for his professional.

It is noticeable in the author's positioning a strong sensitivity to the challenge that teachers face when facing the demands that arise daily in their routine, and about which they need to be aware to act according to the needs that present themselves in the context in which they work, taking into consideration that their role is always crucial in the development of those they have assumed as subjects of their professional choice and with whom they directly influence in their behavior, as will be discussed in the following thematic axis.l performance.

Thematic Axis 3 - Economic Literacy covers values and behavioral changes organized values and behavioral changes for personal and socioeconomic development. Thus, speeches emerged that demonstrate a fairly close understanding of the precepts referring to the theme, according to CI 1 and 2.

The first central idea of this axis was: "Economic literacy involves behavioral values", inferred from the following CSD:

"What economic education covers are values, is to teach the student, not the financial value, of money itself, but the value of behavior, of being a good person, of being a nice person, and also to know how much it costs what their father do to make a living, what kind of work do they get, how do they provide food, shoes, clothes, how was their day, it is about the child being able to value and understand, it is about teaching children these values, the limit to where I can get and where I cannot get. "

It is verified in the excerpt highlighted in the speech above, that in the understanding of the participants the economic literacy encompasses "the values, is to teach the student, not the financial value, the money itself, but the value of behavior" (our emphasis). It can be inferred from this speech that the teachers' beliefs about Economic Literacy meet the premises brought by Araújo (2009, p. 67) when he postulates that economic literacy includes "a set of skills, attitudes and values that allow those who pass through it to understand the economic world closer and its relationships with more global events established by it.

The idea expressed through this speech is that the teaching of economic issues to students goes beyond the simple act of a financial education that is based only on the transmission of quantitative content to students, making room for a qualitative interpretation that involves the apprehension of knowledge aimed at the acquisition of behavioral values that allow children a perception of reality closer to their context, and in which teachers seek to "pass on to the children these values, of the limit to where I can get or not", according to the words expressed by themselves (our emphasis).

The second core idea of this axis has shown that: "Talking to children about the topic can generate behavior change, as demonstrated in the speech that follows: "I'm going to speak as a teacher: from the moment we talk to the student, explain the situation, tell a story of your experience, that you've been through, the student begins to understand that everything you have at home, that you eat, it´s valuable. The child, starting at age 5, begins to have character formation, to know what is right, what is wrong, what I can and cannot do. So, making the child understand what the parents go through to make ends meet, how the parent earns the living, generates the behavior change."

Accordingly, Laroca (2002, p. 39-40) emphasizes an interesting aspect concerning the practice of a teacher, which cannot be deduced only from isolated pedagogical acts that refer only to the teaching-learning process. According to her, there are several perspectives that constitute a teacher's practice, among which we can highlight the very political stance of this professional in society, their commitment to the work they do at school and for the school, their constant search for professional qualification, and other aspects that go beyond the four walls of a classroom.

While contrasting the reflections pointed out by Laroca (2002) with the impressions brought up by the discussion of Thematic Axis 3 and their respective speeches, it is possible to state that their beliefs reflect a strong personal position about the importance given to the financial resources that serve to support the families, and that the teachers try to convey to the children in the most diverse situations that arise in the classroom, and that may be seen as one of the many edges raised by the author, when she teaches us that the teaching practice comprises several aspects that are located beyond the walls of the classroom.

Final considerations

The results obtained in this study, in general, showed that 1) the teachers' knowledge on Economic Literacy is still quite vague, and the beliefs expressed regarding the theme were limited to approximations arising from common sense; 2) practices were evidenced that are limited to a dialogue between teachers and children about some topics that are close to the concepts of EE, yet without intentional, effective and systematized actions in the preschool context; 3) the teachers' beliefs about EE are limited to shallow conceptions and devoid of theoretical foundation, showing that they are not clear about the concepts related to the theme.

Thus, it was not possible to establish a broad network of relationships between the constructs, since there is not yet a more accurate understanding of the precepts of EE. In view of such a finding, recognizing its indispensability in terms of the implementation of a school culture focused on the integral development of the human being as he/she becomes a member of society, the insertion of economic education into the formal educational system can be understood as an option that is urgent and necessary.

The urgency lies in the complexity of living fully in the modern world, which requires the individual to manage his resources responsibly. It is essential to devise strategies that promote, from an early age, the construction of economic relations, understanding that the improvement in people's living conditions happens through social inclusion, political and financial awareness, as well as through reflective actions that encourage greater social participation.

Finally, the present study looked at a very important facet of the current social-economic situation in the local context in which it is inserted, and, at the same time, shed light on aspects related to the teachers' knowledge about issues that are so important for the integral formation of the individual in its different dimensions.

Regarding the main contributions since study, it can be mentioned the expansion of knowledge about teaching beliefs and practices, focusing on teachers who work in early childhood education. It is still possible to study themes of different ramifications, from an interdisciplinary proposal that envisions the analysis of possible relationships and mutual influences between them, for the development of teaching work.

In the academic and social spheres, this study brought contributions in the sense of providing subsidies to the elaboration of educational policies that aim to create practical mechanisms for the implementation of economic literacy actions in day-care centers and preschools in the municipality. The results found here can also corroborate the planning of training and continuing education actions for teachers, whether in early childhood education or even in the subsequent levels of basic education.

In the academic and social scope, this study brought contributions in order to provide subsidies to the elaboration of educational policies that have as objective the creation of practical mechanisms for the implementation of actions of economic literacy in the daycare centers and preschools of the municipality. The results found here can also corroborate for the planning of training actions and continuing education for teachers, whether they are early childhood education or even the subsequent levels of basic education.

Based on the conclusions and inferences produced here, goals and directions for actions can be drawn, so that one can reflect on the possible contents to be worked on in these trainings, which can also be expanded and directed to other audiences, such as parents and even focused directly to the children themselves.

It follows, then, that the results of this research can expand the didactic and pedagogical possibilities related to the theme evidenced here, which can provide subsidies to make the school space an exciting and motivating environment, contributing to assessments of educational practice and behavior, both of teachers and students, since it was detected little exploration in the literature on studies regarding the reflection around the theoretical triad: Economic Literacy - Beliefs and Teaching Practices - Educational Social Skills.

Referências:

AMAR, J. A. et al. Pensamiento económico de los niños colombianos: análisis comparativa en la región. Barranquilla, Colombia: Uninorte, 2002. Disponível em: https://manglar.uninorte.edu.co/calamari/handle/10738/98#page=1. Acesso em: 10 out. 2018. [ Links ]

ARAGÃO, A. B. B. L.; LAUTERT, S. L. Níveis de alfabetização econômica de estudantes dos anos finais do ensino fundamental. Em Teia - Revista de educação matemática e Tecnológica Iberoamericana, v. 12, n. 2, p. 1-22, 2021. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/emteia/article/view/250245. Acesso em: 05 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

ARAÚJO, R. M. B. DE. Alfabetização Econômica: Compromisso Social da Educação das Crianças. 1. ed. São Bernardo do Campo: Universidade Metodista de São Paulo, 2009. [ Links ]

BERTI, A. E. Acquisition of the profit concept by third-grade children. Contemporary Educational Psychology, v. 17, n. 3, p. 293-299, jul. 1992. [ Links ]

BONN, M.; WEBLEY, P. South African children’s understanding of money and banking. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, v. 18, n. 2, p. 269-278, jun. 2000. Disponível em: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1348/026151000165689. Acesso em: 10 out. 2018. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, R. A. Comportamento econômico de crianças e adolescentes: um estudo com alunos do Ensino Fundamental. Pedro Leopoldo: Pedro Leopoldo, 2016. Disponível em: https://www.fpl.edu.br/2018/media/pdfs/mestrado/dissertacoes_2016/dissertacao_renata_aparecida_carvalho_2016.pdf. Acesso em: 10 out. 2018. [ Links ]

DE CASTRO, A. B. C.; DE CASTRO, S. A. Educação Econômica e Financeira: Proposta de diretrizes pedagógicas para o ensino superior tecnológico / Economic and Financial Education: Proposed pedagogical guidelines for technological higher education. Brazilian Journal of Development, v. 7, n. 9, p. 90691-90706, 18 set. 2021. Disponível em: https://www.brazilianjournals.com/index.php/BRJD/article/view/36099. Acesso em: 12 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

DEL PRETTE, Z. A. P.; DEL PRETTE, A. Psicologia das relações interpessoais: Vivências para o trabalho em grupo. 11. ed. Petrópoles, RJ: Vozes, 2014. [ Links ]

DENEGRI C. M. Introducción a la psicología económica. Bogotá: Psicom editores, 2010. Disponível em: http://cepec.ufro.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Introduccion_a_la_Psicologia_Economica.pdf. Acesso em: 15 maio 2019. [ Links ]

DENEGRI, M. C. et al. Socialização econômica em famílias chilenas de classe média: educando cidadãos ou consumidores? Psicologia & Sociedade, v. 17, n. 2, p. 88-98, maio 2005. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/psoc/a/vmpSD6skxJCqBvnKm58YccR/abstract/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 18 out. 2019. [ Links ]

FERMIANO, M. A. B.; CANTELLI, V. C. B. Consumo e a educação e crianças e da família. Anais. Encontro Nacional De Professores do Proepre - 2012 - Águas de Lindóia. São Paulo: 2012. Disponível em: https://rebrinc.com.br/site/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Consumo-e-a-Educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o-de-Crian%C3%A7as-e-da-Fam%C3%ADlia.pdf. Acesso em: 19 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

FURNHAM, A. The saving and spending habits of young people. Journal of Economic Psychology, v. 20, n. 6, p. 677-697, dez. 1999. Disponível em: http://directory.umm.ac.id/Data%20Elmu/jurnal/J-a/Journal%20of%20Economic%20Psychology/Vol20.Issue6.Dec1999/727.pdf. Acesso em: 18 set. 2019. [ Links ]

LAROCA, P. Problematizando os contínuos desafios da psicologia na formação docente. In: AZZI, R. G.; SADALLA, A. M. F. DE A. (Eds.). Psicologia e Formação Docente: Desafios e Conversas. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2002. [ Links ]

LAUER-LEITE, IANI D. Correlatos valorativos do significado do dinheiro para crianças. Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará, 2009. Disponível em: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1roIvGCHmvYjNXjiWAr39kOR1JmCQ6GZT/view. Acesso em: 19 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

LAUER-LEITE, I. D. et al. Socialização econômica: conhecendo o mundo econômico das crianças. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), v. 15, n. 2, p. 144-152, ago. 2010. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/epsic/a/CnbS74KFFRkwJLG7hPbD47g/?lang=pt&format=pdf. Acesso em: 19 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

LEFÈVRE, F.; LEFÈVRE, A. M. C. Discurso do Sujeito Coletivo: um novo enfoque em pesquisa qualitativa (desdobramentos). ed. rev. e ampl ed. Caxias do Sul: EDUCS, 2005. [ Links ]

MANFREDI, S. M. Metodologia do ensino: diferentes concepções. Campinas: FE, 1993. [ Links ]

OCDE. Recommendation on Principles and Good Practices For Financial Education and Awareness. Recommendation of The Council. jul. 2005. Disponível em: https://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-education/35108560.pdf. Acesso em: 05 mar. 2020. [ Links ]

ORTIZ, M. F. A. Educação Para o Consumo: diagnóstico da compreensão do mundo econômico do aluno da educação de jovens e adultos. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2009. [ Links ]

PAIVA, M. L. M. F.; DEL PRETTE, Z. A. P. Crenças docentes e implicações para o processo de ensino-aprendizagem. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, v. 13, n. 1, p. 75-85, jun. 2009. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-85572009000100009. Acesso em: 25 fev. 2020. [ Links ]

PUGH, P.; WEBLEY, P. Adolescent participation in the U.K. National Lottery Games. Journal of Adolescence, v. 23, n. 1, p. 1-11, fev. 2000. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10700367/. Acesso em: 15 maio 2019. [ Links ]

ROCKEACH, M. Crenças, Atitudes e valores: uma teoria de organização e mudança. [s.l.] Interciência, 1981. [ Links ]

SADALLA, A. M. F. DE A. et al. Psicologia e Licenciatura: crenças, dilemas e contribuições. Pro-Posições, v. 16, n. 1, p. 241-257, abr. 2005. [ Links ]

SADALLA, A. M. F. DE A.; SARETTA, P.; ESCHER, C. DE A. Análise de Crenças e suas implicações para a Educação. In: AZZI, R. G.; SADALLA, A. M. F. DE A. (Eds.). Psicologia e Formação Docente: Desafios e Conversas. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2002. [ Links ]

SILVA, B. DA C. N. Alfabetização econômica, hábitos de consumo e atitudes em direção ao endividamento de estudantes de pedagogia. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 12 dez. 2008. [ Links ]

SILVA, A. M. DA; POWELL, A. B. Educação financeira na escola: a perspectiva da organização para cooperação e desenvolvimento econômico. Boletim GEPEM, n. 66, p. 3-19, 2015. Disponível em: https://doi.editoracubo.com.br/10.4322/gepem.2015.024. Acesso em: 18 set. 2019. [ Links ]

SOARES, I. M. F.; BEJARANO, N. R. R. Crenças dos professores e formação docente. Revista Faced, n. 14, p. 55-71, jul. 2008. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufba.br/bitstream/ri/1184/1/2654.pdf. Acesso em: 25 fev. 2020. [ Links ]

WEBLEY, P. The economic psychology of everyday life: becoming an economic adult. University of Exeter ed. England: Exeter, 1999. [ Links ]

Received: November 01, 2021; Accepted: June 01, 2022

texto em

texto em