Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensino em Re-Vista

versão On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.30 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 01-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v30a2023-10

Articles

Pedagogical coordination and teachers in the early years of elementary school: challenges and possibilities1

2Ph.D. in Educational Psychology from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC), full professor at the Faculty of Education (undergraduate and graduate) of the Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU), Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: mirene@ufu.br.

3Master's degree in Education from the Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU). Professor and Pedagogical Analyst at the Municipal Department of Education of Uberlândia, Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: ped24580@sme.udi.br.

This text presents an excerpt from a master's research carried out in the Graduate Program in Education at the Federal University of Uberlândia (PPGED/UFU) whose object of investigation was the role of pedagogical coordination with teachers in the early years of elementary school in municipal schools in Uberlândia. The objectives of the study consisted of analyzing: the performance of the pedagogical coordination with teachers of the 1st and 2nd years of Elementary School; and the challenges that emerge from the interaction between the pedagogical coordination and teachers in the early years of Elementary School and that reverberate in the teaching and learning processes. Methodologically, the work is grounded on the principles of qualitative research, specifically a case study approach. The Focus Group (FG) with the coordinators and the Semi-structured Interview (SSI) with the teachers were used as research instruments. The analysis highlights that coordinators and teachers are key players in the teaching and learning processes, particularly during the literacy period. Thus, they need to establish partnerships and promote collective work to address the challenges and contradictions that pervade the school context.

KEYWORDS: Pedagogical coordination; Teaching; Early years of Elementary School

Este texto apresenta um recorte de uma pesquisa de mestrado realizada no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (PPGED/UFU), cujo objeto de investigação foi a atuação da coordenação pedagógica junto às professoras dos anos iniciais do Ensino Fundamental em escolas municipais de Uberlândia. Os objetivos do estudo consistiram em analisar: a atuação da coordenação pedagógica junto a professoras do 1º e 2º anos do Ensino Fundamental; e os desafios que emergem da interação entre a coordenação pedagógica e professoras dos anos iniciais do Ensino Fundamental e que reverberam nos processos de ensino e aprendizagem. Metodologicamente o trabalho está fundamentado nos princípios da pesquisa qualitativa, do tipo estudo de caso. Foram utilizados como instrumentos de pesquisa o Grupo Focal (GF) com as coordenadoras e Entrevista Semiestruturada (ES) com as professoras. A análise evidencia que as coordenadoras e professoras são protagonistas nos processos de ensino e aprendizagem, em especial no período de alfabetização. Dessa forma, necessitam construir parcerias e efetivar o trabalho coletivo para enfrentamento dos desafios e contradições que permeiam o contexto escolar.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Coordenação pedagógica; Docência; Anos iniciais do Ensino Fundamental

Este texto presenta un extracto de una investigación de maestría realizada en el Programa de Posgrado en Educación de la Universidad Federal de Uberlândia (PPGED/UFU) cuyo objeto de investigación fue el papel de la coordinación pedagógica con las profesoras en los primeros años de la Escuela Primaria en las escuelas municipales de Uberlândia. Los objetivos del estudio consistieron en analizar: el desempeño de la coordinación pedagógica con docentes de 1° y 2° años de la Escola Primaria; y los desafíos que surgen de la interacción entre la coordinación pedagógica y los docentes en los primeros años de la escuela primaria y que repercuten en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Metodológicamente, el trabajo se basa en los principios de la investigación cualitativa, del tipo estudio de caso. Se utilizaron como instrumentos de investigación el Grupo Focal (GF) con las coordinadoras y la Entrevista Semiestructurada (ES) con las docentes. El análisis evidencia que las coordinadores y docentes son protagonistas en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje, especialmente en el período de alfabetización. Por lo tanto, necesitan construir alianzas y realizar un trabajo colectivo para enfrentar los desafíos y contradicciones que permean el contexto escolar.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Coordinación pedagógica; Enseñanza; Primeros años de la Escuela Primaria

Introduction: presentation of the research object

The presented work results from the investigative practice of a master's degree conducted in the field of Education by the Federal University of Uberlândia (Universidade Federal de Uberlândia - UFU), focusing on the study of the pedagogical coordination's role alongside teachers in the early years of Elementary School in municipal schools of Uberlândia. The research emerged from the researcher's experiences and professional development, which sparked inquiries and intentions to deepen the understanding of actions and relationships that occur within the school context.

Based on the assumption that pedagogical coordination influences teaching praxis, the research object was delimited through the following problematizing questions: what is the role of pedagogical coordination in relation to teachers in the 1st and 2nd grades of Elementary School? Do the actions of pedagogical coordination support the work of teachers in their role of teaching literacy to children in the 1st and 2nd grades of Elementary School? How? What are the challenges that arise from the interaction between pedagogical coordination and teachers and how do they impact the processes of teaching and learning?

In line with the problematizing questions, the objectives consisted of analyzing: the role of pedagogical coordination alongside teachers in the 1st and 2nd grades of Elementary School; and the challenges that emerge from the interaction between pedagogical coordination and teachers in the early years of Elementary School, which have an impact on the processes of teaching and learning. Considering the objectives, methodologically, the work was based on the principles of qualitative research, specifically a case study.

For the presentation of the research, the text was organized as follows: firstly, the research trajectory was addressed, elucidating the research field, participants, and data collection instruments. Next, the data analysis and the categories formed to address the problematization and objectives of the study were presented. Finally, provisional conclusions were presented, considering that knowledge is historical and dynamic, thus each statement opens up new questions.

The study aimed to contribute to the understanding of the role of pedagogical coordination alongside teachers in the early years of Elementary School and to support the overcoming of challenges in the processes of teaching and learning.

Paths taken in the research

Engaging in educational research implies finding paths that, at times, may appear uncertain but, with relevant and conscious choices, lead to discoveries about previously unknown aspects that require clarification and answers.

When considering that research seeks answers, it is necessary to define the paths to be taken. In this sense, the choice was made for a qualitative research perspective.

Qualitative research approaches are based on a perspective that views knowledge as a socially constructed process by individuals in their everyday interactions, as they act in and transform reality, while also being transformed by it. Thus, the individual's world, the meanings they attribute to their daily experiences, their language, cultural productions, and forms of social interaction constitute the central concerns of researchers. If the view of reality is constructed by individuals in the social interactions they experience in their work, leisure, and family environments, it becomes essential for the researcher to approach these situations. (ANDRÉ, 2013, p. 97)

Embracing qualitative research means understanding the underlying assumptions in the approach and, at the same time, appropriating the methodological process ethically and responsibly, as the act of researching involves understanding reality and its subjects. Regarding the production of knowledge, in this perspective, González Rey (2005) states:

Qualitative Epistemology defends the constructive and interpretative nature of knowledge, which implies understanding knowledge as a production rather than a linear appropriation of the reality presented to us. Reality is an infinite domain of interrelated fields independent of our practices. However, when we approach this complex system through our practices, which, in this case, involve scientific research, we create a new field of reality in which practices are inseparable from the sensitive aspects of this reality. It is precisely these aspects that can be given meaning in our research. It is impossible to think that we have unlimited and direct access to the system of reality; therefore, such access is always partial and limited by our own practices. (GONZÁLEZ REY, 2005, p. 5)

When addressing the educational context, it is necessary to understand the relationships established in the field of Education and the different actors involved in pedagogical practices; in other words, it requires proximity and understanding of the conceptions present in everyday school life.

In this sense, approaching reality cannot be done through "guesswork" or "superficiality" in the analysis of people and objects. It is important to consider what is intrinsic and can only be seen through deeper approaches, in other words, in a dense manner.

Brandão (2003) considers the researcher as an individual who creates and constructs procedures and results beyond mere observation and recording. From this perspective, engaging in scientific research is not merely about having a method and strictly adhering to it; it demands reflection from researchers regarding their own conceptions and what constitutes them as historical, political, psychological, physical, and social beings.

Based on these assumptions, the chosen methodological approach for this study was a case study, which is a qualitative research modality that encompasses fundamental aspects that allow for the understanding of a particular phenomenon while considering different contexts and dimensions to explore situations in depth and contribute to the advancement of knowledge and theory production.

Regarding case studies in the educational context, André (2013) suggests that:

If the interest is to investigate educational phenomena in the natural context in which they occur, case studies can be valuable tools. The direct and prolonged contact of the researcher with the events and situations being investigated allows for the description of actions and behaviors, capturing meanings, analyzing interactions, understanding and interpreting languages, and studying representations without disconnecting them from the context and specific circumstances in which they manifest. Thus, case studies enable us to comprehend not only how these phenomena arise and develop but also how they evolve over a given period of time. (ANDRÉ, 2013, p. 97)

The choice of qualitative case study was made based on the objectives and problematizations that emerged, as well as the understanding that this research modality possesses the scientific rigor necessary to construct fundamental knowledge in the field of education, while also facilitating a clear and detailed elucidation of the steps followed during the investigation.

In this research, the context of the case study was the Municipal Education Network of Uberlândia, where the work of the pedagogical coordination is carried out. To gather the data, four schools were selected, located in different regions of the city, each with a history of experiences related to the research object.

To preserve their identities, the participating institutions were named as Paulo Freire (School 1), Rubem Alves (School 2), Cecília Meireles (School 3), and Demerval Saviani (School 4). The choice of these names was made out of admiration and recognition for these remarkable scholars who have deeply thought about and contributed to Education in Brazil. Each of them had unique ways of experiencing the educational landscape and struggles, serving as an inspiration to many other educators.

Regarding the research participants, the following chart summarizes the quantitative distribution by school.

CHART 1: Research participants

| Schools | Teachers | Pedagogic Coordinators |

|---|---|---|

| Paulo Freire | PA1 | CP1 |

| PA2 | CP2 | |

| CP3 | ||

| Rubem Alves | PA3 | CP4 |

| PA4 | CP5 | |

| CP6 | ||

| Cecília Meireles | PA5 | CP7 |

| PA6 | ||

| Demerval Saviani | PA7 | CP8 |

| PA8 |

Source: the researchers.

The data was revealed through two methodological instruments: the Focus Group (FG) with the pedagogical coordinators (Coordenadoras Pedagógicas - CP) and the Semi-Structured Interview (SSI) with the literacy teachers (Professoras Alfabetizadoras - PA). Both moments were crucial for the investigation regarding the relationship between the pedagogical coordinators and the teachers working in the early stages of Elementary School. They were also important for providing the experience of listening to professionals who work in the daily life of schools, facing challenges and difficulties, and seeking to contribute to the students' learning process.

Regarding the research context, it is relevant to highlight that the data collection process took place during the period of social distancing caused by the Covid-19 pandemic4. Schools were closed for face-to-face classes and transitioned to remote teaching5.

Given the current situation, the FG and the SSI were conducted remotely through digital tools that allowed for the necessary interactions and connections with the research subjects.

Regarding the Focus Group, it consisted of coordinators from four schools in the Municipal Network, two from urban areas and two from rural areas, totaling eight coordinators who constituted a heterogeneous group in terms of their professional and personal characteristics. According to Gatti (2005), the Focus Group is suitable for groups in which questions are raised and discussed. During the dialogues, the coordinators' statements encompass the dimension of training, the ideological principles upheld, the norms and legal actions that govern the role and school practices, and the various elements that make up the professional daily life of these individuals.

To conduct the Focus Group, it is necessary to pay attention to the relevant procedures. According to Gatti (2005), it is important to prepare for the meeting in advance. The researcher needs to: develop a script; organize the environment so that everything can run smoothly; ensure that the discussions stay focused; and encourage the participants to feel included and motivated to cooperate with the work being done. Therefore, in the research, the guiding script for the Focus Group with the coordinators was developed based on the problematization and desired objectives. The first part of the FG was dedicated to presenting the research, its objectives, and clarifications, as well as individual introductions by the pedagogical coordinators who formed the group and brought their reflections and knowledge to the dialogue. After this introduction, the mediator of the FG presented the guiding questions and the correlations between them, as well as highlighted the need and importance of everyone's input. According to the preferences of each coordinator, the participants took turns speaking in an attempt to contribute to the achievement of the research objectives.

During the interviews, the participating teachers brought forth the dimension of the teaching and learning process, the factors that support and guide their conduct and teaching practices within the school context. The opportunity to listen to the teachers working in the early years of Elementary School allowed for the attribution of meanings and significance to the research. Each shared story and practice revealed the richness of educational actions and guided the data according to the research objectives. In this sense, discussing the relationship between coordinators and teachers became important as they constitute two sides that are not opposed but complementary. The interviewed teachers shared their perspectives, knowledge, and aspirations when faced with the challenge of teaching children who are in the period of discoveries, curiosity, fears, and playfulness.

After the interviews and the Focus Group, facing the gathered information, we reached one of the most demanding moments of the research: data analysis.

Data analysis: the construction of new knowledge

Analyzing the data entails organizing and reflecting on the information obtained, based on the objectives, problematization, and theoretical framework that guided the research.

According to Bardin (2011), data analysis is also an analysis of meanings, as it involves an objective, organized, and evaluative explanation of the content derived from the interactions and their interpretation.

The author asserts that the research method has fundamental stages for its realization. In her studies, she highlights three phases to be followed by the researcher in conducting content analysis, which are: 1) pre-analysis; 2) material exploration; and 3) treatment, inference, and interpretation of the results.

During the material exploration, the data is coded, ordered, and organized, giving rise to units of records that share common characteristics and serve as points of articulation for the information.

Based on the categorization criteria proposed by Bardin (2011), the categories of analysis for this study emerged, aiming to address the problematization and the proposed objectives. Thus, categorization consists of organizing the information, attributing meaning and significance to it based on inferences.

In this study, three categories of analysis were defined: 1) the roles of the pedagogical coordinator and their professional constitution; 2) teachers and pedagogical coordinators: “being together”; and 3) challenges and contradictions in coordination practice. As previously mentioned, the organization and analysis of the data aimed to address the research problematics according to the categories outlined below.

The roles of the pedagogical coordinator and their professional constitution

Given the research proposal to analyze the relationship between teachers and coordinators in the process of literacy, it was necessary to address the roles of pedagogical coordinators in school settings.

During the Focus Group with the pedagogical coordinators, similarities in their perception of the role assumed in school settings were identified. The coordinators expressed that they "enjoy their profession", "enjoy what they do", "love education", and recognize the "importance of the position of pedagogical coordinator" for the development of educational activities. In this sense, the following statements illustrate their perspectives:

I love what I do. (CP8)

I enjoy my profession as a coordinator and working in literacy. (CP3)

I’ve found myself and I’m happy. (CP5)

I consider the profession of coordinator as an enriching experience. (CP4)

I am happy to share, to be together with people who bring experiences. Anything related to education attracts me. (CP7)

This subjective and affective aspect became essential in an educational context marked by adversities in carrying out their work, as well as the unfortunate social devaluation that still affects education professionals. Thus, the fact that coordinators recognize their role and also enjoy what they do should not be disregarded when analyzing the context of the study.

The professional constitution of the pedagogical coordinator encompasses the subjective process, even though the responsibilities are objectively common. However, according to Franco (2016), other aspects need to be considered.

Coordinating pedagogical tasks is not an easy task. It is very complex because it involves clarity of political, pedagogical, personal, and administrative positions. Like any pedagogical action, it is a political, ethical, and committed action that can only bear fruit in an environment collectively engaged with the assumed pedagogical assumptions. (FRANCO, 2016, p. 23)

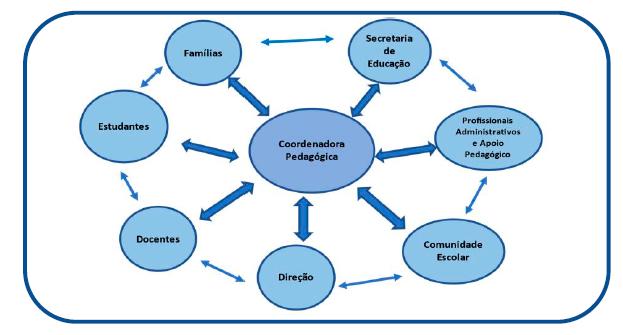

Pedagogical coordinators recognize themselves as part of the process with their specificities, along with other professionals who are equally important in educational practices. Figure 1 illustrates how the practice of pedagogical coordination permeates the relationships between the individuals who make up the schools and, at the same time, how coordinators articulate their actions with teaching work and mediate relationships with parents, students, principals, and other professionals and educational institutions.

Source: the researchers.

FIGURE 1: Articulation of pedagogical coordination with other school actors

When analyzing the work of pedagogical coordination in the Municipal Network of Uberlândia, the responsibilities reveal the articulations and relationships established in the daily practices of professionals.

In fulfilling their responsibilities, the coordinators positioned themselves as learners and emphasized the importance of formative and professional experiences, as well as their relationship with other professionals in shaping their role in pedagogical coordination. For CP3: "practices in coordination are enriched through diverse experiences". CP7 states: "My foundation began in the classroom". This statement denotes the dimension of teaching work and the Pedagogy course for the identity formation of professionals working in the school context. Experiencing the joys and challenges of the classroom provides not only practical training but also a prism through which to view the act of education, which is essential.

In this vein, CP3's statement is revealing: "I learn every day, with my professional partners, with the teachers, with the children, with the families. I am happy in what I do". Therefore, it can be considered that the role of pedagogical coordination enables the connection of individuals involved in the processes of teaching and learning, and in doing so, establishes healthy interpersonal relationships.

This perspective highlights the importance of pedagogical knowledge for the realization of pedagogical coordination as a collective practice that presupposes support and partnerships. In this sense, the next category of analysis addresses "being together" or the knowledge and practices that bring together teachers in the early years of Elementary School and pedagogical coordinators.

Teachers and pedagogical coordinators: "being together"

During the Focus Group, the coordinators often mentioned the need to "be together" with the teachers, engaging in a partnership and "being together to try to help the teachers in their difficulties and raise awareness" (CP1).

The perspective of "being together" also aligns with the expectations of the teachers:

A good pedagogical coordinator has to work together with the teacher, have knowledge of teaching methods, have knowledge of projects, and be an ally of the teacher. It's a collaborative effort. So, the coordinator needs to be there, side by side with the teacher, knowing everything that is happening inside the classroom, also knowing the children because they provide support to the children as well. So, for me, the coordinator is the key piece of the school, of the pedagogical aspect. Can we manage without them? We can, as teachers, manage without them, but we really need them. They also facilitate the connection between teachers because we have to interact with each other, exchange experiences, right? So, the coordinator also has the function of mediating conflicts because the team has conflicts since everyone thinks differently, right? And they mediate conflicts to achieve what is central to the school, which is the pedagogical aspect. (PA5)

"Being together" refers to the need to know the reality of each classroom, monitor the students' development, their abilities, and difficulties, be aware of the curriculum plan, and engage in dialogue with teachers about the methodological possibilities related to the stages of literacy.

One possibility to promote this closeness, according to CP7, is to make good use of Module II6 and have moments of classroom observation.

Valuing the modules because they allow for proximity with the teacher. Using these moments to analyze together, tabulate data, and see the progress made by the children. What to do to make the child progress. The power to go to the classroom, being together. My observation helps me a lot. Simple things to carry out the work. (CP7)

Pedagogical actions with teachers involve collective work, considering the particularities, expectations, proposals, and objectives to be achieved.

The coordinator is just one of the actors within the school collective. To coordinate, directing their actions towards transformation, they need to be aware that their work does not happen in isolation but within this collective, through the articulation of different school actors, aiming to build a transformative pedagogical project. (ORSOLON, 2001, p. 19)

In other words, pedagogical work is based on collective actions that articulate the different knowledge of teachers and coordinators.

Pedagogical work is at the core of educational institutions as its nucleus is the work with knowledge (in terms of critical, creative, meaningful, and lasting appropriation), which, in turn, is the specificity of the school, constituting the main purpose of educational praxis, along with full human development and critical joy. It implies both the teacher's and the student's activity, as learning, although occurring in a social context, depends primarily on the student's action; furthermore, the recognition of the student's activity comes from adopting a line of developing autonomy and constructing a life project. (VASCONCELLOS, 2019, p. 19)

The pedagogical action of the coordinator enables successful exchanges of experiences among the group of teachers in the early years of Elementary School, proposing innovative practices. To do so, it is necessary to listen to and consider the knowledge and methodological choices of the teachers, favoring the construction of an environment in which all actors are responsible for the work. Therefore, “being together” contributes to facing the inherent challenges in pedagogical work.

The next category of analysis refers to these challenges, as well as the actions of teachers and coordinators, which highlight some contradictions.

Challenges and contradictions in coordination practice

The field of Education is stimulating and challenging, so being a professional and reflecting on educational actions becomes provocative in various aspects. Coordinating the pedagogical process in the school context requires direct contact with classrooms, students, teachers, and the community.

Based on the analyzed data, it was possible to infer that pedagogical coordinators are faced with several challenges in their daily lives, as it is necessary to manage the institution's environment alongside other professionals in the school.

The relationships established within the school's leadership team are discordant in some aspects. As presented by some pedagogical coordinators, at certain times, the relationship is characterized by competition and assertions about who holds "power". Such professional relationships need to be redefined in the school management process, as stated by CP7:

Respect is key in relationships and spaces between principals and coordinators. Sometimes the principal gets jealous and wants to be the star. When they realize that the group is highly involved with the pedagogue. It has happened to me before. It seems like they want to intervene in some way. (CP7)

In line with this, one of the pedagogical coordinators brought the following statement to the dialogue in the Focus Group:

We have the pillars, learning to be, learning to do (...). We live in constant change, sometimes we progress, sometimes we regress. There needs to be a pedagogical atmosphere within the school. The atmosphere cannot be political-party-oriented; it has to be pedagogical. Everyone focused on the same interest in advancing and feeling, there is no need for someone from outside to dictate the minimum grade of external evaluations. We can feel when the school is doing well. Everyone can perceive that. Then the criticisms decrease. (CP6)

In addition to the previous idea, another coordinator contributed:

Our role within the school institution is essential. The function goes beyond being an analyst. I reaffirm that we are not ready. No one here is ready. We are constructing ourselves as professionals, as pedagogues. I want to leave my mark. To see our professional category in this movement and make our contribution. (CP8)

The coordinators' accounts reveal that the relationships within school spaces are not always harmonious; there are conflicts of ideas, thoughts, and opinions. However, there is also an emphasis on the pedagogical aspect and the actions of the coordinators, who are in constant process of development.

Another challenge in the relationship between pedagogical coordinators and teachers is related to student discipline. Paradoxically, in many cases, it is expected that the coordinator "correct" or "handle" the lack of discipline of some students. Therefore, it is common for students to be removed from the classroom and sent to the Coordinator's office. At this moment, coordinators complain about the volume of demands and state that indiscipline is a challenge for both coordination and teachers, considering that the school is a collective space.

From the teachers' perspective, the work of coordination cannot be hindered by discipline issues:

Large schools have a lot of discipline problems. And it ends up that the pedagogue often deals with discipline issues, right? And it ends up that the teacher, the support to the teacher, the participation in the classroom, sometimes leaves something to be desired. I'm not saying that discipline has nothing to do with the pedagogical aspect. It does. Because sometimes children are undisciplined because something in the pedagogical aspect inside the classroom is wrong. So, it is very difficult for the pedagogue to work with these issues and still deal with the pedagogical aspect. (PA5)

Discipline issues require the attention of both coordination and teachers, as removing the student from the classroom and passing the responsibility to coordination with a few minutes of conversation is a contradictory practice that needs to be rethought.

The time between the pedagogical coordinator and the teachers should be dedicated to planning successful practices that aim to address all school demands, including those related to discipline.

This third category of analysis highlighted some challenges and contradictions that involve demands related to monitoring teaching and learning processes, providing guidance to teachers and other professionals to propose enjoyable lessons in line with reality, and building partnerships to maintain focus on what is essential to the work of coordination: the school's pedagogical process.

Lastly, the accounts provided by the research participants prompted reflections on the reality of school institutions, highlighting demands as well as possibilities for thinking and acting.

Through the study, it can be inferred that both coordinators and teachers are equally responsible for student learning, especially in the early years of Elementary School. Therefore, there is a need for a partnership that breaks away from individualistic school practices that do not respect the student as a protagonist and knowledge builder; in other words, a partnership committed to the development of each and every individual.

Preliminary conclusions

The development of the investigative process led to several discoveries through the dialogues established with the research participants, including teachers and pedagogical coordinators, who shared their knowledge, aspirations, and commitment to contribute to the field of education.

The research provided insights into the main actions of pedagogical coordination that support the work of teachers: mediating the relationship with families through dialogue and providing necessary guidance for children's learning; guiding the planning of literacy teaching and learning processes; seeking ways to work collectively; aligning legislation and curricula with the reality of students; and providing ongoing professional development within the school's professional group.

The research participants highlighted the daily challenges that permeate the school context, particularly in terms of interpersonal relationships and the need for support in the demands inherent to the literacy process. In summary, the main challenges include: carrying out the role of pedagogical coordination without “falling into the traps” of bureaucratic activities and focusing on the pedagogical demands that involve teachers and students, with sensitivity to the teachers' requests. Therefore, teachers and coordinators emphasize the importance of partnership and collective work, in other words, "being together".

Related to the challenges, the research revealed some contradictions characterized by a polarization of understanding regarding the roles of pedagogical coordinators. Some school professionals expect coordinators to independently resolve certain daily school issues, such as discipline. However, within the same context, some teachers believe that by addressing these issues, the coordinator falls short of fulfilling their true role: the pedagogical process. This not only pedagogical but also bureaucratic perspective of pedagogical coordination is reaffirmed by the Municipal Department of Education (Secretaria Municipal de Educação - SME), which promotes an education with more conservative principles, where the role of the pedagogical coordinator includes even overseeing and controlling the work of teachers. According to the SME, the Pedagogical Analyst, the term used for pedagogical coordination, is expected to analyze, investigate, and ascertain, which differs from coordinating, suggesting, and mediating the pedagogical proposal. As a result, there is resistance from coordinators who aspire to better working conditions and recognition of the importance of their role in schools.

Returning to the research objectives, it is evident that the different practices involved in coordinating a school team require knowledge of various areas of education, as well as the development of mediation skills, analysis, and monitoring of teaching work, and the flexibility to deal with differences, whether they are professional, methodological, or related to learning. In this aspect, it is crucial for the coordinator to continuously seek their own professional development to overcome academic challenges in all their dimensions. The pursuit of knowledge is necessary for all who dare to teach. In other words, both coordinators and teachers are unfinished beings, constantly in the process of becoming. In this regard, Freire (2004, p. 58) states: "It is in the inconclusiveness of being, recognizing oneself as such, that education as a permanent process is founded. Men and women become educable to the extent that they recognize themselves as unfinished".

The professional development of teachers and coordinators necessitates the need for working conditions and dedicated time for continuous education, providing space and time for the construction of new knowledge, considering that ongoing training is not solely the responsibility of individual professionals, but also of the education systems.

If teachers and pedagogical coordinators face challenges in their daily school life, they also find alternatives to fulfill their roles. Therefore, it is essential to establish dialogue and collaboration to ensure support and collective work. In this perspective, there is a need for a willingness to attentively and respectfully listen to others, acknowledging their individuality. The relationship between coordinators and teachers is complementary, as the knowledge of teaching, built upon the Pedagogy course, underpins actions in the classroom and the school as a whole.

Finally, conducting the research has addressed the initially proposed questions while also raising new ones that justify further studies, as knowledge is never exhausted and the pursuit of knowledge is constant, involving the dialectic of learning and teaching.

REFERENCES

ANDRÉ, Marli. O que é um estudo de caso qualitativo em educação? Revista da Faeeba Educação e Contemporaneidade, Salvador, v. 22, n. 40, p. 95-103, jun. 2013. Semestral. Disponível em: http://www.mnemos.unir.br/uploads/13131313/arquivos/Marli_Andr__O_que___um_Estudo_de_Caso_417601789.pdf. Acesso em: 16 fev. 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21879/faeeba2358-0194.v22.n40.753. [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70, 2011. [ Links ]

BRANDÃO, Carlos Rodrigues. A pergunta a várias mãos: a experiência da pesquisa no trabalho do educador. São Paulo: Cortes, 2003. [ Links ]

FRANCO, Maria Amélia do Rosário Santoro. Da Pedagogia à coordenação pedagógica: um caminho a ser re-desenhado. In: CAMPOS, Elisabete Ferreira Esteves; FRANCO, Maria Amélia do Rosário Santoro (org.). A coordenação do trabalho pedagógico na escola: Processos e Práticas. Santos): Universitária Leopoldianum, 2016. p. 17-31. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da autonomia: Saberes Necessários à prática educativa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2004. [ Links ]

GATTI, Bernadete Angelina. Grupo focal na pesquisa em ciências sociais e humanas. Brasília: Líber Livro, 2005. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ REY, Fernando. Pesquisa Qualitativa e Subjetividade: Os processos de construção da informação. São Paulo: Pioneira Thomson, 2005. [ Links ]

ORSOLON, Luzia Angelina Marino. O coordenador/formador como um dos agentes de transformação da/na escola. In: ALMEIRA, Laurinda Ramalho de; PLACCO, Vera Maria Nigro de (org.). O coordenador pedagógico e o espaço da mudança. 3. ed. São Paulo: Loyola, 2001. p. 17-34. [ Links ]

PAULA, Daniela Silva de. Atuação da coordenação pedagógica junto as professoras alfabetizadoras de escolas municipais de Uberlândia/MG: contribuições, desafios e possibilidades. 2021. 148 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, 2021. DOI: http://doi.org/10.14393/ufu.di.2022.5003. [ Links ]

VASCONCELLOS, Celso dos S. Coordenação do trabalho Pedagógico: do projeto político pedagógico ao cotidiano da sala de aula. 16. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2019. [ Links ]

4COVID-19 is a disease caused by the Coronavirus. The first cases were identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. The manifestation of the disease ranges from flu-like symptoms to more severe pneumonia. Due to the high rate of contagion, the absence of vaccines, and the complications in the clinical condition of some infected individuals, social distancing was recommended to reduce the number of cases.

5Remote teaching emerged in an attempt to enable the continuity of educational activities through digital resources such as email, WhatsApp, video lessons, platforms, among others. The goal was to mitigate the impact on the learning of children and young people who had to stay away from school.

Received: January 01, 2023; Accepted: June 01, 2023

texto em

texto em