Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensino em Re-Vista

versão On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.30 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 01-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v30a2023-11

Articles

Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê and Theo against certainties: towards the Itinerant Curriculum Theory1 2

3Master’s in Contemporary Art. Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. E-mail: lukaspachecobrum@yahoo.com.

4Master’s in Law. Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. E-mail: nataliafdacunha@gmail.com.

5PhD in Education. Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. E-mail: mclleite@gmail.com.

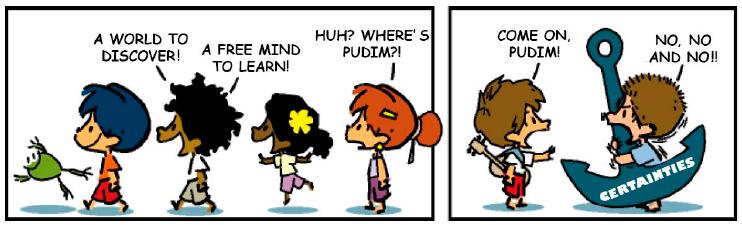

This paper discusses the conception of the Itinerant Curriculum Theory (ICT) by Professor João Paraskeva, based on the analysis of an image that occupies a central place in school culture. The image is a comic strip, whose main characters are: Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê, Theo and Pudim, created by the artist Alexandre Beck, which addresses us to the cultural practices of the gaze, builds and influences our ways of seeing, thinking, teaching and curriculum making, to the pedagogical practices and school contents. Thus, this text is inserted in the theoretical fields of Visual Culture Studies and Contemporary Curriculum Studies. We sought an analysis of the comic strip generated by the conceptual tool of the itinerant curriculum, that helps us to understand Beck’s images as a possibility that escapes the established guidelines of the school and of the hegemonic knowledge legitimized by the curriculum.

KEYWORDS: Itinerant Curriculum; Comic Strip; Education; Images

Este artigo problematiza a concepção da Teoria do Currículo Itinerante de autoria do professor João Paraskeva, a partir da análise de uma imagem que ocupa lugar central na cultura escolar. A imagem é uma tirinha, protagonizada pelos personagens Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê, Theo e Pudim, produzida pelo artista Alexandre Beck, a qual nos endereça às práticas culturais do olhar, que constroem e influenciam nossos modos de ver, pensar, ensinar e fazer o currículo, às práticas pedagógicas e aos conteúdos escolares. Assim, esse texto encontra-se inserido nos campos de teorização dos Estudos da Cultura Visual e dos Estudos Curriculares Contemporâneos. Busca-se uma análise da tirinha acionada pela ferramenta conceitual do currículo itinerante, que nos auxilia a compreender as imagens de Beck como uma possibilidade que escapa às ordens estabelecidas pela escola e pelo conhecimento hegemônico legitimado pelo currículo.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Currículo Itinerante; Tira; Educação; Imagens

Este artículo discute la concepción de la Teoría del Currículo Itinerante, del profesor João Paraskeva, a partir del análisis de una imagen que ocupa un lugar central en la cultura escolar. La imagen es una tira, protagonizada por los personajes Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê, Theo y Pudim, producida por el artista Alexandre Beck, que nos remite a las prácticas culturales de la mirada, que construyen e influyen en nuestras formas de ver, pensar, enseñar y hacer el currículo, las prácticas pedagógicas y los contenidos escolares. Así, este texto se inserta en los campos teorizantes de los Estudios de la Cultura Visual y los Estudios Curriculares Contemporáneos. Se busca un análisis de la franja desencadenada por la herramienta conceptual del currículo itinerante, que nos ayude a comprender las imágenes de Beck como una posibilidad que escapa a los órdenes establecidos por la escuela y por los saberes hegemónicos legitimados por el currículo.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Currículo Itinerante; Banda; Educación; Imágenes

Introduction

We live and coexist with different types of images and visual objects, which invade our homes, school practices, work environments and places we visit on a daily basis. In different materialities, whether printed, digital or in motion, “they behave like viruses that spread and mutate faster than our immune systems can evolve in order to fight them” (MITCHELL, 2012, p. 27). They flood our lives, steal our attention, establishing ways of being and existing in culture, governing our bodies, thoughts, attitudes, imaginations and behavior.

The speed and volume of images that besiege and challenge us on a daily basis constitute a kind of avalanche that drags us down, bewilders and fragments us without having time to reflect, analyze or make any kind of criticism about them. (MARTINS, 2010a, p. 21).

In this sense, we can understand that culture, and the ways in which we interpret it and act in it, is increasingly visual and polysemic, and that the images and cultural artifacts produced by it determine a large part of social relations, exchanges of meanings, of cultural productions, identities and subjectivities of the individuals. As a result, contemporary life has developed under the regime of images and cultural artifacts “in an imaginary spiral, in which seeing is more important than believing. It is not a mere part of everyday life, but everyday life itself” (MIRZOEFF, 2003, p. 3).

However, education, school curricula, pedagogical practices, tastes and interests of children, adolescents and young people are also targets of seductive cultural images and artifacts that attract and repel. In this way, for example, many of the representations that are manufactured by culture are addressed and operationalized in educational contexts, with the purpose of teaching, forging and questioning the current practices and conceptions of education, placing under suspicion the school curricula, the statization of school contents, the ways of teaching, what is taught and the conduct of teachers in the face of new orders in contemporary spheres.

In this direction, the strips created by the artist and illustrator born in the state of Santa Catarina (SC), Brazil, Alexandre Beck - father of the character Armandinho -, understood here as images, assume an important role within culture, and mainly in education, as their productions act as “carriers and mediators of meanings and discursive positions that contribute to thinking about the world and ourselves as subjects” (HERNÁNDEZ, 2011, p. 33). This means considering that the images, that is, the artist’s comics, are discourses permeated by power and knowledge relations that fall within the field of Visual Culture Studies (BRUM and LEITE, 2023; HERNÁNDEZ, 2007, 2011, 2013,; MITCHELL, 2012; MIRZOEFF, 2003; MARTINS, 2007, 2010a, 2010b; TOURINHO and MARTINS, 2011, 2012, 2013; TOURINHO, 2011), claim and question the ways of being and doing education, and, above all, the school contents and curricula. Beck’s strips, thus, put meanings into circulation that often seek, in a creative and humorous way, to question the power systems that cross school contexts and curricula, destabilizing and giving rise to new ways of thinking, acting and seeing with/and in the curriculum.

The field of Visual Culture emphasizes not only the images that surround culture, but seeks to focus on the visual experiences that subjects manufacture and engender with what is seen and the ways in which they are seen in culture. In this understanding, “the relevant pedagogies of visual culture are not the objects, but the relationships we maintain with them” (HERNÁNDEZ, 2013, p. 83). In other words, it is about social mediations and visual experiences that we establish with images, which are imbued with meanings that form, educate and establish our conceptions of education and curriculum.

Marked by this bias, given the way in which we relate, live together, interact and are forged, especially with educational images, this work is originated from debates held at the “Laboratório Imagens da Justiça” [Justice Images Laboratory], at the Federal University of Pelotas - UFPel6 (BRUM; CUNHA and LEITE, 2021; BRUM and LEITE, 2023), studies and analysis that the authors have been developing in their research. Among the various research interests that the Laboratory concentrates, one of its tentacles is the problematization between images and curriculum, analyzing and examining what the images say, utter, claim and question about the curricula and the elements that make it up, seeking to understand images as pedagogies, from the post-structuralist perspective in education.

To this end, the text is structured as follows: in the first part we present the creator of Armandinho’s strips, the character himself and give a brief explanation of the concept of strips. In the second part, we make some notes on the theoretical perspective of the “itinerant curriculum” by João Paraskeva (2010, 2016, 2021) and how the author epistemologically structures this curriculum theorization. In this sense, the itinerant curriculum is used here as a conceptual tool to help understand Beck’s images as a possibility that escapes the orders established by the school and by the hegemonic knowledge legitimized by the curriculum. In the last part of the text, we expose the analysis carried out of a strip, starring Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê, Theo and Pudim, which addresses us to the cultural practices of the gaze, which build and influence our ways of seeing, thinking, teaching and curriculum making, to the pedagogical practices and school contents.

The productions of Armandinho strips by the illustrator Alexandre Beck

As previously mentioned, Alexandre Beck is an artist from Santa Catarina, author, creator and the father of the character Armandinho. The little boy with blue hair, smart, challenging, questioning, insightful, curious and good-natured, is a phenomenon on social media on the internet - with more than a million fans and followers on Facebook and Instagram, thousands of likes, shares and comments. The character stars in the strips along with his inseparable pet frog and, sometimes, with his other friends. The group of friends is always involved in social, environmental, political, educational and public health issues. The strips are often involved in polemics that are circumscribed in contemporary society, with the intention of provoking and expanding reflections and discussions on important subjects, such as: prejudice, appreciation of fundamental rights and guarantees, structural racism, feminism, homophobia, gender, preservation of the environment, politics, among others.

According to Alexandre Beck, the character Armandinho was born in a hurry, on October 9, 2009, at the request of a friend who needed an illustration for a report on the economy about parents and children, which would be published the very next day in the newspaper Diário Catarinense, from Santa Catarina7, where Beck also worked publishing the comic strip República, since 2000.

[In] a short term, Beck reused some scribbles from another work of his own, draw some pairs of legs that would symbolize the child’s parents. This way, the boy with blue hair and a gentle and challenging personality appeared. (RODRIGUES, 2019, p. 49).

The character Armandinho won permanent space in the newspaper from Santa Catarina due to the popularity achieved among the newspaper’s readers through his stories, narratives and adventures, being published since May 17, 20108. To name him, the newspaper’s editorial staff held a contest - the winning proposal was that of a teacher, with the justification that the boy was always “armando” [being up to] something in his comic strips. That’s how the curious, questioning, blue-haired boy got the name Armandinho (SAYURY, 2019).

Armandinho’s strips, with their narratives, consequently also began to be printed in other daily newspapers, such as Zero Hora (state of Rio Grande do Sul) and Folha de São Paulo (state of São Paulo), among others. In 2011, the character also started to be published regularly on a Facebook9 page and on Instagram and won eight printed collections, published independently, between 2013 and 2018. On the pages of digital social networks, called “Tiras Armandinho” [Armandinho’s strips], different strips that the author frequently posts, can be found. From publications in newspapers with wide circulation, the character gained prominence throughout Brazil, and also outside the national territory, through internet networks. The popularity and reach of the character’s strips were so great - and still are -, that they started to be licensed for reproduction in textbooks.

On the concept of strips, Silva and Vieira (2018), based on Paulo Ramos (2009) explain that

[...] the comic strip genre has a variable nomenclature, being known as: tirinha [little strip], tira cômica [comic strip], tira de jornal [newspaper strip], tira de quadrinhos [comic strip panels], tira em quadrinhos [strip in panels], tira diária [daily strip], tirinha em quadrinhos [little strip in panels], tira de humor [humor strip], tira humorística [humoristc strip], tira jornalística [journalistic strip]. (SILVA and VIEIRA, 2018, p. 206).

Also popularly known as comics, this is a textual genre, with three or more panels aligned horizontally, in order to tell a story that usually presents everyday themes of a humorous, satirical and political nature, making criticisms to social values.

The characters of the strips “can be permanent or not and, in most strips, there is a tendency to create an unexpected ending [...] and through the use of dialogues a complete story is told, bringing the climax in the last panel” (RODRIGUES, 2019, p. 47). These visual sources/means are usually published regularly in print and digital media, exploring “various resources, both verbal and non-verbal” (SILVA and VIEIRA, 2018, p. 206), “characterized by their ironic statements and their critical approach to certain subjects” (RODRIGUES, 2019, p. 47). Therefore, we can define the strips as

[...] a critical representation of everyday life that, using a humorous or satirical view, conveys a message of an opinative nature and through its verbal and non-verbal language. It is capable of overcoming censorship and establishing itself as a journalistic genre with the same properties as chronicles, cartoons, opinion articles or editorials. (NICOLAU, 2011, p. 10).

Thus, the strips produce narratives in opinative, critical and even mocking ways, involving various aspects and issues that are posed in society. The illustrator’s creations, starring Armandinho and his friends, have raised deep reflections, questions and resistance on countless subjects and themes that surround contemporary times in a critical, intelligent and transgressive way. Alexandre Beck states in a lecture given in March 2018 at the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP): “I don’t want my work to be seen as entertainment, because the strips are not an end. They are a means to make people aware of issues that matter” (BECK, 2018)10.

In the author’s words, his strips have a political and awareness-raising function on issues that matter. This means considering that images are not just illustrations at the service of entertainment, but that they articulate relations of power and knowledge, which produce our identities, thoughts and subjectivities, and above all what we think about education, the school curriculum, democratization of education, as well as what we do in our pedagogical practices. Thus, Beck’s productions go beyond their aesthetic, illustrative and decorative value, they are based on the recognition of the image through the understanding of its role in social, political and cultural life.

Notes on the Itinerant Curriculum

In this part of the text we propose to present the Itinerant Curriculum Theory as a possibility of thinking about the school curriculum from a theorization that challenges the traditional field of scientificity. The idea of proposing a theory of an itinerant curriculum, according to João Paraskeva (2010), stemmed from concerns and reflections that emerged from the Curriculum Work Group at the meeting of the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Education (ANPEd) , in 2007. According to Paraskeva (2010), the participants of the Curriculum Work Group were not satisfied with the paths that the theme of the curriculum and its theories were going through. Thus, the proposal to think about a curriculum that challenges the “determining form of power instituted over the field” arose (PARASKEVA, 2010, p. 53).

The proposal of an Itinerant Curriculum Theory (ICT) is a challenge to historically hegemonic and counter-hegemonic curriculum studies. In this sense, the author seeks in the studies developed by Boaventura de Sousa Santos, especially from the concept of epistemicide, to present a non-abyssal and non-territorial theory. In other words, to propose and think about a curriculum for the “now”. “A theory of non-places and non-times is, in essence, a theory of all places and all times” (PARASKEVA, 2016, p. 126).

Before presenting what the ICT is, it is necessary to understand some issues that are fundamental to it. Thus, it is important to present the epistemological paths that Paraskeva sought for the conception of ICT, since this theorization seeks to break with modern critical studies. However, it is important, initially, to point to modern thinking, in order to observe how the production of knowledge was historically constituted.

Scientific knowledge from modernity onwards was transformed, and the new episteme has as its central point a universal science of order and measure. “In place of a truth revealed by faith, it instituted human reason as a principle for building knowledge and as a promise of better conduction of human life” (PEREIRA, 2014, p. 3). The purpose of modernity, therefore, was to oppose the medieval world, breaking with the past based on religiosity and the relationship of men with their cosmos.

Modernity marks itself with the rupture of the medieval state and has, with regard to the production of knowledge, the outstanding characteristic of rationality as (re)cognition of the truth. Knowledge was presented as a general science of order and measure, which sought in mathematics the new standard of rationality. Thus, “mathematics is the source of analysis and investigation of the production of knowledge where scientific rigor is assessed by the rigor of measurements, since knowing means quantifying” (SANTOS, 2011, p. 63).

The model of rationality that characterizes the Modern Age, constituted in the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, also reflected in the relations between subjects and the production of knowledge. Modernity brought man to the center of attention of knowledge, as a being endowed with reason. The construction of knowledge rooted in rational logic, of verification, imposes on the subjects the certainty of their domain, given that the model that follows the paths of order offers the certainty of the scientific result. Instead of the truth declared by religious bias, as in the Medieval Era, in the Modern Age, human rationality is the principle of construction of truth. Thus, this new way of conceiving knowledge took root and was consolidated in the experimental method that developed the rationalist conception as a determining element of scientific production.

What is verified, in this sense, is that modernity has solid foundations, which create the paradigm with promises of equality from the centralization of the individual. However, what can be seen is that these foundations focused on rationality sedimented values that were forged by modernity itself. The progressive idea presented from the order gave way to a model in which the central individual did not represent the majority of the individuals. This progressive idea represents a dialectical process that, according to Bittar (2008, p. 138), “is the same that feeds the processes of accelerated destruction of the natural world and exhaustion of the physical environment on which the very survival of humanity rests”. And it is from this progress that humanity is threatened with human degradation. About that, Bittar (2008) still argues that

modern discourse has promoted sky-high the idea that there would be a victory for civilization, but what we are experiencing is the beginning of the end of barbarism, the exploitation of man by man, which can only be operated through natural barbarism itself. (BITTAR, 2008, p. 140).

In the same sense, Santos (2011) argues that:

The promise of perpetual peace, based on trade, the scientific rationalization of decision-making processes and institutions, led to the technological development of war and the unprecedented increase of its destructive power. The promise of a fairer and free society, based on the creation of wealth made possible by the conversion of science into a productive force, led to the spoliation of the so-called Third World. (SANTOS, 2011, p. 56).

Rationalist models, based on the centrality of reason, and simplistic models, which intended progress without seeing the whole, do not seem appropriate in a contemporary society where it is necessary to think of the human being from a set of social relations and economic, social transformations and policies. The individualist model has its origins in the modern state, which, culminating in capitalism, provokes the individualist feelings perceived in society today.

The perspective presented from the construction of knowledge recognized by modernity raises, therefore, questions that cross curricular theories. Thus, in the face of conditions imposed as scientific and legitimized truths, the curricular field is impacted and reflects the “certainties” attributed by historically instituted curricula. It is in the face of this tangle of truths, certainties and reliable knowledge that the ICT invites us to think of the curriculum field as a process of cultural and epistemological struggles, proposing an “other” curriculum, which impels us to reflect from “processes related to identity, difference and the subjective” (PARASKEVA, 2010, p. 57).

The ICT is based on the epistemological field that concerns the fight against epistemicide11. Paraskeva, like Boaventura Santos, proposes that the production of knowledge - and here considering curricular theories - overcomes the hegemonic Eurocentric perspective, with a content of truths, and considers, in addition, “other ways of thinking, theorizing, doing education and curriculum alternatively” (PARASKEVA, 2021, p. 24). For ICT, it is necessary to consider the ignored and neglected epistemologies of the South12 in this field of knowledge.

The proposal presented by Paraskeva (2010), therefore, is based on and committed to an emancipatory ecology of knowledge, which aims to promote the democratization of knowledge. The curriculum, therefore, needs to fight against curricular epistemicides, from the encounter with social practices and with the realities that surround the subjects.

We need a curriculum theory and practice that reflects equating its own territorialities, perfectly aware that a new order and counter-order must be contemplated from the new scope of power relations. (PARASKEVA, 2016, p. 123).

It is in this sense that the author proposes an intrinsically itinerant theory: “[...] it is important to fight for a theory and curricular practices that move away from the current territory [that] move away from the spaces regulated by the dominant systems” (PARASKEVA, 2010, p. 58).

It should also be noted that, like Paraskeva’s theory proposal, the epistemological field of curriculum studies also presents other theoretical perspectives, which debate, problematize and contribute with their theorizations to counter-hegemonic curriculum policies and practices, placing under suspicion the conceptions of traditional and critical curriculum theories, such as post-critical theories (SILVA, 2020; LOPES and MACEDO, 2014; LOPES, 2013), post-colonial theories (SANTOS and SILVA, 2020; FERREIRA and SILVA, 2013), post -modern (SILVA, 2006; SILVA, 1993), post-structuralist (OLIVEIRA, 2018; PARAÍSO, 2010, 2019; CORAZZA and SILVA, 2003) and cultural studies (SILVA, 1995, 1999, 2020), among others.

These different lines and theoretical approaches, which have their origins, non-immobilized specificities, directly or indirectly intersect, penetrate, move and help with their conceptual scopes and theorizations. Some of them are more directed towards knowledge derived from everyday life, cultures, experiences of subjects or hidden knowledge, and others towards rejected, subordinated or marginalized knowledge. In addition, other theoretical strands are focused on power and knowledge relations, curricular resistances and subjectivation processes within the curriculum, as well as the debate and theorizations on the concepts of ideologies, hegemonies, social justice, emancipation, class, gender, race and so many other social markers.

A parenthesis is opened to say that not all these multiple lines of theorization culminate in the same direction, in the sense of being related to curricular or education policies, but contribute to a heterogeneous and uneven discussion to think, problematize in the field of practice and theory practices or curricular conceptions that still privilege traditional and critical perspectives.

Thus, there are other perspectives of counter-hegemonic theories, which somehow also dialogue with the ICT, proposed by João Paraskeva. According to the author, his theory is a struggle for (re)knowledge that is completely itinerant, since he proposes to think of a curriculum for the “now”, deterritorialized, anchored in local cultures and experiences, which recognizes other types of knowledge. “The itinerant curriculum theory is an exercise in citizenship and solidarity, and above all an act of social justice” (PARASKEVA, 2016, p. 127). It is in this exercise of citizenship and social justice that we begin to present the analysis of a strip by Alexandre Beck, aligned under this curricular perspective, together with the thoughts of other authors who are added to this process.

Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê and Theo against certainties: towards the Itinerant Curriculum Theory

Source: Adapted from: <https://www.facebook.com/tirasarmandinho>. Accessed on Sept. 15, 2021.

FIGURE 1: Armandinho strip - Alexandre Beck

Fê, in the first panel, when looking ahead and seeing his friends Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene and not locating Pudim, asks “Huh? Where’s Pudim?!”. Pudim, in the last panel, is clinging to an anchor with two hooks, made of iron or metal, whose purpose is to retain ships and large maritime transport, holding them to the bottom layer of a body of water to prevent the vessel from deviating due to wind or current. Clinging tightly to the anchor, Pudim shouts to his friend Theo “No, No and No!!”, when Theo exclaims, calling him “Come on, Pudim!” when seeing that the friend is standing still, not following the rest of the group. What everything indicates is that Theo is waiting for his friend to go together in the same direction, as shown in the first panel.

The negative sentence uttered by Pudim, his position on the anchor and the boy’s reaction of not wanting to go along with his friends Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê and the frog, leads us to a problematization about curricula and school knowledge which are often crystallized, didactic and recontextualized (LOPES and MACEDO, 2011) as “certainties”, being regulated by dominant and hegemonic systems (PARASKEVA, 2010), functioning as sources of unique and unquestionable truths - as appears in the last panel.

According to Lopes and Macedo (2011), school knowledge means not only the teaching contents that are recontextualized in textbooks, but a set of norms and values that constitute the curricula. Although today we have significant advances in curriculum theories (SILVA, 1995, 2020; LOPES, 2013; LOPES and MACEDO, 2011; MOREIRA and SILVA, 2001; MOREIRA, 1990, 1999), it is still possible we find in pedagogical practices, in the classrooms of Brazilian schools, contents, discourses and teaching proposals, that is, what is taught, often rooted in certainties and truths that favor curricular epistemicides (PARASKEVA, 2010, 2016, 2021).

In this regard, Moraes (2010) argues that the curriculum can no longer continue to consist of pre-programmed truths and neither can the school context as “the ‘locus of absolute certainties’, since uncertainty is inalienable to the process and the meaning of something is socially constructed” (MORAES, 2010, p. 8). We understand, therefore, that the school and the curriculum should subvert this process, no longer validating and reaffirming certainties and truths as curricular epistemicides, but placing them under doubt and distrust, questioning and inquiring the students about the certainties of the school contents that make up the curricular epistemic matrices of schools.

However, this does not mean, nor are we refuting, that scientific knowledge historically constructed, selected, validated and recontextualized as school content is not taught and worked on in pedagogical practices. On the contrary, we understand that they can be the subject of discussions, positions of divergent ideas, understanding the times and spaces in which they were manufactured in convergence with the “now”, as Paraskeva (2010, 2016, 2021) proposes in the itinerant curriculum.

For this to happen, schools and the professionals who work in them can propose the creation of spaces for discussions and reflections in which the voices of students can be heard in relation to what they think, hear, visualize and already know about school content. The curriculum, thus, starts to “take into account the local and everyday knowledge that students bring to school”, understanding that “this knowledge can never be a basis for the curriculum” (YOUNG, 2007, p. 1299), but that it is fundamental for an educational practice and an itinerant curricular perspective, which unties and releases curricular anchors, placing students as proposing agents of the curriculum and learning. Considering a proposal for an itinerant curriculum in this direction, which disarms the anchors, is nothing more than fighting against curricular epistemicides, in Paraskeva’s perspective, seeking to deterritorialize the certainties rooted in critical curricular theory.

According to João Paraskeva, critical curriculum theory no longer produces “strangeness”, it is no longer a “strange” thing produced by “strangers”; it became “predictable” (PARASKEVA, 2021, p. 42). The “becoming predictable” that the author refers to is allowing other knowledge not legitimized by the curricular canon to be possible to learn, deconstructing the hegemony of a curriculum that is imbricated in certainties and veracity. It is in this sense that the central idea of the ICT proposes to think of a new curriculum theorization. Armandinho and his friends, therefore, seem to share this perspective, as it is explicit in the speech in the strip when Camilo says that we have “A world to discover!”

The anchor, an emblematic object present in the image, operates as a metaphor, considering that school contents and teachers’ attitudes are often trapped and attached to a closed and anachronistic curricular structure. This structure produces the fragmentation of knowledge and a concept of a linear, rigid, pasteurized and homogenized curriculum of “‘one size fits all’ that serves everyone” (MORAES, 2010, p. 3), eliminating the needs, desires, willings of the students and teachers for the desire to learn, impoverishes the collective and collaborative work, weakens the positions of ideas and divergent thoughts.

A curricular architecture, in this conception, reinforces and leverages the legitimacy and recontextualization of certainties, truths, ideologies and convictions that, consequently, standardize and regulate what must be learned, what must be taught and what needs to be discussed, without often presenting other references, other ways of how knowledge is socially constructed, so that students can critically question and put under suspicion, as Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê and Theo invite us to do in the first panel. In this way, the characters who star in the strip question and put into operation in the educational context the discourse that “[...] there is not a single form of valid knowledge. There are many forms of knowledge, as many as the social practices that generate and sustain them” (SANTOS, 1999, p. 283).

Thus, school contents and knowledge that are imbued with a certain amount of certainties and truths, and the ways in which they are presented in school practices, regulate and operate on bodies, thoughts, imaginaries, attitudes, opinions, conceptions of the students’ world, and above all about their subjectivation processes. School contents and discourses, built and anchored as certainties and truths, form students, not only with regard to school education, but as existing beings.

In this understanding, the curriculum becomes a social relationship that produces effects on those involved, in which the construction of knowledge takes place in the relationship between people. Silva (1995) explains that it is

important to see the curriculum not just as being costructed of “doing things”, but also as “doing things to people”. The curriculum is what we, teachers and students, do with things, but it is also what the things we do do to us. (SILVA, 1995, p. 194).

Given this, “the curriculum is not an innocent and neutral element” of construction “disinterested of social knowledge. The curriculum is implicated in power relations, the curriculum conveys particular and interested social views, the curriculum produces particular individual and social identities” (SILVA and MOREIRA, 2004, p. 8).

In this way, everything we teach our students, the choices we make for certain knowledge, the ideological positions we believe in and the theoretical and epistemological approaches we make to compose our pedagogical practices and the curriculum, all of this “makes us to be what we are” (SILVA, 1995, p. 196). In this sense, when we produce the curriculum from our choices, preferences and selections, if

we are also produced, it is because we can be produced in very particular and specific ways. And these forms depend on specific power relations. Catching and identifying them, thus, constitutes a fundamentally political action. (SILVA, 1995, p. 194).

Therefore, we can say that the school contents that act as an anchor, rooted in certainties and veracity, evoke perspectives of a curriculum that is stuck and tied, that does not let flow, that does not let walk along unknown paths and venture itself into the discoveries that may happen in the learning course of an itinerant curriculum, focused on the now, in the face of the world’s knowledge ecology. This idea of an anchor curriculum, in a way, allows the security and reliability, both for those who teach and prepare the curriculum, and for those who learn, that the contents will be taught following a linear and chronological sequence, without spaces, openings, gaps and cracks for the unforeseen and the unthinkable within pedagogical practices.

In the same way, a curriculum in this conception goes against what is expected from the perspective of the itinerant curriculum, as it minimizes and limits the movements and displacements of a meaningful, autonomous, critical, creative learning, based on the discoveries of the students, proponents of their own learning and also of their own curriculum, as the image in the comic strip shows us.

Thus, Pudim, when standing still, immobilized and located in the same place/space embraced in the anchor with his certainties, refuses to go along with his friends who have open minds to learn the new and the unknown. Better saying, for what Paraskeva calls the “itinerant curriculum”, to know the unknown, to learn what has not been learned, seen, visualized, heard, thought and experienced (PARASKEVA, 2016). In other words, it is an itinerant curriculum with possibilities or that allows students, as Camilo says: “A world to discover!”, free from social ties, certainties, convictions, safeties and epistemicides. In this way, the author, when proposing a theory that goes against the grain of epistemic certainties, suggests a curriculum that considers the ecology of knowledge, as defined by Santos (2020, p. 59), and that consists of “the identification of the main sets of knowledge which, when brought up for discussion in a given social struggle, may highlight important dimensions of a struggle or resistance”.

It is in this process of resistance of non-legitimized knowledge that we make it possible for students produced by a certain curriculum to explore “A world to discover!”. It is based on the struggles that we allow to reveal the power of the diversity of knowledge existing in the culture of the students and in the world, which must intensify the practices within the itinerant curriculum. A curriculum, from this perspective, that considers the ecology of knowledge is in line with the itinerant curriculum, which favors the processes of investigation, creation and storytelling within pedagogical practices, amalgamated with the vicissitudes of contemporary societies and the emerging social and cultural problems of the “now” in which students are inserted.

A curricular conception, in this sense, “requires an encounter with the practices and realities that surround us” (PARASKEVA, 2016, p. 123). That is why we, teachers, need to leave aside the anchors of the curricular epistemic contents that tie and imprison us and “commit ourselves to the development of a learning that truly guarantees competence and citizenship formation”; that “favors through the improvement of our capacity for reflection and greater awareness of the problems that surround us, from a discussion connected with the great challenges that contemporaneity presents to us” (MORAES, 2010, p. 2).

Camilo, still in the first panel, directs us to a speech about the fact that we and our students must have “A free mind to learn!”. The character’s speech calls into question the need to build a meaningful teaching and learning process, which is free and uncovered by certainties and reductionisms. However, in addition to free minds to learn, it is necessary that teachers, in their pedagogical practices, enable alternatives that empower students as thinking and autonomous subjects, thus stimulating that free minds build other knowledge, those that the itinerant curriculum advocates as an ecology of knowledge. Therefore, contrary to producing minds full of certainties and truths, it is necessary to allow possibilities for critical learning, connected with the various social demands that cross the subjects.

The French philosopher Edgar Morin (2004), about this, helps us to reflect on Camilo’s argument, explaining this idea that a “well-made head” is better than a “well-filled head”. According to the author, the meaning of a “well-made head” is not associated with a head where knowledge is simply grouped and accumulated, but rather organized to make it interconnected and connected, seeking to give meaning to the knowledge already built together with the uncertainties of the contemporary world. From Morin’s (2004) perspective we can consider that a “well-filled head” produces difficulties and obstacles for “A mind free to learn!”. On the other hand, a “well-made head”, from the point of view of the itinerant curriculum, allows subjects to build knowledge in view of the different types of knowledge and the cultural diversity that constitutes them, without being grounded in the certainties of the hegemonic curricula.

In this sense, we align our thoughts and concepts of curriculum with the curriculum theory elaborated by João Paraskeva, as we believe that a curriculum should promote free minds to learn and well-made heads, instead of well-filled heads. Only in this way will we be able to let go of the curricular anchors that are rooted in certainties and epistemicides, enhancing and exploring the wide range of knowledge ecology that is daily part of the cultural contexts of our students. Better saying, we have a world of knowledge ecology to discover and explore. Armandinho, Camilo, Etiene, Fê and Theo, therefore, are engaged in questioning and showing us new horizons, new routes and curricular compositions.

Conclusion

Not satisfied with current curricular and educational issues, the characters in Alexandre Beck’s productions are in close relations of power and knowledge, which produce and question our conceptions of education, curriculum, school knowledge and the ways in which we act in our pedagogical practices. This means that images are visual representations that function as a system of meanings, assuming a symbolic function in which information, knowledge, entertainment and communication circulate (TOURINHO, 2011), influencing, directing, changing and transforming the senses, experiences and the meanings of subjects, students and teachers.

Finally, throughout this text, we sought to analyze a strip produced by the artist Alexandre Beck, based on the conceptual tool of João Paraskeva’s (2010, 2016, 2021) Itinerant Curriculum Theory. We sought, therefore, to conceive the image as a discourse, through Visual Culture Studies, understanding what the images say, operate and question within education and the school curriculum. It should also be noted that we consider that this text does not end here, on the contrary, it starts here. From the comic strip, some reflections were made that could give rise to new readings, thoughts, meanings, observations and analyses. And this is what we hope for. We invite, in this sense, the readers to look at the images that are addressed to education and reflect what they have to tell us based on the experiences of the present, of the now, alternatively to what is set.

REFERENCES

BECK, A. Tiras do Armandinho. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/tirasarmandinho. Accessed on: Jul. 2, 2021. [ Links ]

BECK, A. Palestra Proferida de Alexandre Beck. Universidade Estadual de Campinas - UNICAMP, 2018. Available at: https://www.unicamp.br/unicamp/noticias/2018/03/22/alexandre-beck-criador-do-armandinho-fala-sobre-sua-arte-e-direitos-humanos. Accessed on: Jul. 2, 2021. [ Links ]

BITTAR, E. C. B. O direito na pós-modernidade. Revista Sequência, Florianópolis, n. 57, p. 131-152, dez. 2008. Accessed on: Jul. 2, 2021. DOI:https://doi.org/10.5007/2177-7055.2008v29n57p131. [ Links ]

BRUM, L. P.; CUNHA, N. F.; LEITE, M. C. Imagens e currículos: o que dizem as tiras de Armandinho sobre os currículos escolares? Revista Espaço do Currículo, João Pessoa, v. 14, n. 3, p. 1-14, set./dez. 2021. Accessed on: Jul. 1, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15687/rec.v14i3.59105. [ Links ]

BRUM, L. P.; LEITE, M. C. Caminhos, direções e emergências nos estudos da Cultura Visual no século XXI. Educação em Foco, Belo Horizonte, v. 26, n. 48, p. 1-23, jan./abr. 2023. Accessed on: May 1, 2023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.36704/eef.v26i48.7046. [ Links ]

CORAZZA, S.; SILVA, T. T da. Composições. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2003. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, M. G.; SILVA, J. F. da. Perspectiva pós-colonial das relações étnico-raciais nas práticas curriculares: conteúdos selecionados e silenciados. Revista Teias, Rio de Janeiro, v. 14, n. 33, p. 25-43, 2013. Available at: https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/revistateias/article/view/24363. Accessed on: Mar. 10, 2023. [ Links ]

HERNÁNDEZ, F. A Cultura Visual como um convite à deslocalização do olhar e ao reposicionamento do sujeito. In: MARTINS, R.; TOURINHO, I. (org.). Educação da Cultura Visual: conceitos e contextos. Santa Maria: Ed. da UFSM, 2011. p. 31-49. [ Links ]

HERNÁNDEZ, F. Pesquisar com imagens, pesquisar sobre imagens: revelar aquilo que permanece invisível nas pedagogias da cultura visual. In: MARTINS, R.; TOURINHO, I. (org.). Processos e práticas de pesquisa em cultura visual e educação. Santa Maria: Ed. da UFSM, 2013. p. 77-113. [ Links ]

HERNÁNDEZ, F. Catadores da Cultura Visual: proposta para uma nova narrativa educativa. Tradução: Ana Duarte. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2007. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C. Teorias pós-críticas, política e currículo. Educação, Sociedade & Culturas, Porto: CIIE, n. 39, p. 7-23, 2013. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C.; MACEDO, E. Teorias de Currículo. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C.; MACEDO, E. The curriculum field in Brazil since the 1990’s. In: PINAR, W. (org.). International handbook of curriculum studies. New York: Routledge, 2014. p. 86-10. [ Links ]

MARTINS, R. Hipervisualização e territorialização: questões da Cultura Visual. Educação & Linguagem, São Paulo, v. 13, n. 22, 19-31, jul./dez. 2010a. Available at: https://www.metodista.br/revistas/revistasims/index.php/EL/article/view/2437/2391. Accessed on: Aug. 23, 2022. [ Links ]

MARTINS, R. Pensando com imagens para compreender criticamente a experiência visual. In: ASSIS, H. L.; RODRIGUES, E. B. T. (org.). Educação das artes visuais na perspectiva da cultura visual: conceituações, problematizações e experiências. Goiânia: 2010b. p. 19-38. [ Links ]

MARTINS, R. A cultura visual e a construção social da arte, da imagem e das práticas do ver. In: OLIVEIRA, M. (org.). Arte, educação e cultura. Santa Maria: UFSM, 2007. p. 19-40. [ Links ]

MIRZOEFF, N. Una introdución a la cultura visual. Barcelona: Editora Paidós Ibérica, 2003. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, W. J. T. O futuro da imagem: a estrada não trilhada de Rancière. In: MARTINS, R.; TOURINHO, I. (org.). Cultura das Imagens: desafios para arte e para a educação. Santa Maria: Ed. da UFSM, 2012. p. 19-35. [ Links ]

MORAES, M. C. Complexidade e currículo: por uma nova relação. Polis Revista Latinoamericana, Santiago, p. 1-20, 2010. Available at: https://journals.openedition.org/polis/573. Accessed on: Aug. 28, 2022. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, A. F. B. Currículos e Programas no Brasil. Campinas: Papirus, 1990. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, A. F. B. (org). Currículo: Políticas e práticas. Campinas: Papirus, 1999. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, A. F. B.; SILVA, T. T da. Currículo, Cultura e Sociedade. 9. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2001. [ Links ]

MORIN, E. A cabeça bem-feita: repensar a reforma, reformar o pensamento. 9. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2004. [ Links ]

NICOLAU, V. F. A reconfiguração das tiras nas mídias digitais: de como os blogs estão transformando este gênero dos quadrinhos. 2011. 103 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Comunicação) - Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, 2011. Available at: https://repositorio.ufpb.br/jspui/handle/tede/4464. Accessed on: Nov. 2, 2021. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, M.B. de. Pós-estruturalismo e teoria do discurso: perspectivas teóricas para pesquisas sobre políticas de currículo. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 23, p. 1-18, dez. 2018. Accessed on: May 7, 2023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782018230081. [ Links ]

PARAÍSO, M. A. O currículo entre o que fizeram e o que queremos fazer de nós mesmos: efeitos das disputas entre conhecimentos e opiniões. Revista e-Curriculum, São Paulo, v. 17, n.4, p. 1414-1435, out./dez. 2019. Accessed on: Mar. 5, 2023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.23925/1809-3876.2019v17i4p1414-1435. [ Links ]

PARAÍSO, M. A. Diferença no currículo. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 40, n. 140, p. 587-604, maio/ago. 2010. Available at: https://publicacoes.fcc.org.br/cp/article/view/178. Accessed on: May 2, 2023. [ Links ]

PARASKEVA, J. M. Nova Teoria Curricular. Mangualde; Ramada: Edições Pedago. 2010. [ Links ]

PARASKEVA, J. M. Desterritorializar: Hacia a una Teoría Curricular Itinerante. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, Murcia, v. 85, n. 30.1, p 121-134, 2016. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/274/27446519012.pdf. Accessed on: Jun. 12, 2022. [ Links ]

PARASKEVA, J. M. Covid-19! Quem ‘descobriu quem? Rumo a uma teoria curricular itinerante dos povos. Momento - Diálogos em Educação, Rio Grande, v. 30, n. 2, p. 24-49, maio/ago. 2021.. Accessed on: Jun. 25, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14295/momento.v30i02.13296. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, E. M. A. A construção do conhecimento na modernidade e na pós-modernidade: implicações para a universidade. Revista Ensino Superior UNICAMP, Campinas, n. 14 jul./set. 2014. Available at: https://www.revistaensinosuperior.gr.unicamp.br/artigos/a-construcao-do-conhecimento-na-modernidade-e-na-pos-modernidade-implicacoes-para-a-universidade. Accessed on: Jun. 12, 2022. [ Links ]

RAMOS, P. Humos nos quadrinhos. In: VERGUEIRO, W.; RAMOS, P. (org.). Quadrinhos na educação: da rejeição à prática. São Paulo: Contexto, 2009. p. 185-218. [ Links ]

SAYURY, J. Alexandre Beck, o pai do Armandinho. Revista Trip, 2019. Available at: https://revistatrip.uol.com.br/trip/webstories/alexandre-beck-o-pai-do-armandinho. Accessed on: Jul. 5, 2021. [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, C. K. A. A Intertextualidade como característica essencial para o humor, crítica social e compreensão das tirinhas da Mafalda e Armandinho. Revista Ininga, Teresina, v. 6, n. 1, p. 43-61, 2019. Available at: https://revistas.ufpi.br/index.php/ininga/article/view/10118/7205. Accessed on: Jun. 12, 2022. [ Links ]

SANTOS, B. S. Pela mão de Alice: o social e o político na pós-modernidade. 7. ed. Edições Afrontamento, 1999. [ Links ]

SANTOS, B. S. Para um novo senso comum: a ciência, o direito e a política na transição paradigmática. In: ______. (org.). A crítica da razão indolente: contra o desperdício da experiência. 8. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. p. 15-37. [ Links ]

SANTOS, B. S. O fim do império cognitivo: a afirmação das epistemologias do Sul. 1. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2020. [ Links ]

SANTOS, A. R dos; SILVA, J. F da. Currículo pós-colonial e práticas docentes descoloniais: caminhos possíveis. Debates em Educação, Maceió, v. 12, p. 387-407, set./out. 2020. Accessed on: Jul. 1, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.28998/2175-6600.2020v12nEspp387-407. [ Links ]

SILVA, J. A. P da; VIEIRA, M. S. P. Tiras cômicas e charges: Potencialidades para promover o letramento multimodal. Revista Práticas de Linguagem, Juiz de Fora, v. 8, n. 2, p. 195-211, 2018. Accessed on: Mar. 12, 2022. DOI:https://doi.org/10.34019/2236-7268.2018.v8.28324. [ Links ]

SILVA, M. A da. Currículo para além da pós-modernidade. In: REUNIÃO ANUAL DA ANPED, 29., 2006, Caxambu. Anais [...]. Caxambu: ANPEd, 2006. Available at: https://www.anped.org.br/biblioteca/item/curriculo-para-alem-da-pos-modernidade. Accessed on: Jun. 3, 2023. [ Links ]

SILVA, T. T da. Documentos de identidade: uma introdução às teorias do currículo. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2020. [ Links ]

SILVA, T. T da. Currículo e identidade social: territórios contestados. In: SILVA, T. T da. (org.). Alienígenas na sala de aula: uma introdução aos Estudos Culturais em Educação. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1995, p. 190-207. [ Links ]

SILVA, T. T da. (org.). O que é afinal estudos culturais?. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 1999. [ Links ]

SILVA, T. T da. (org.). Teoria educacional crítica em tempos pós-modernos. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1993. [ Links ]

SILVA, T. T da; MOREIRA, A. F. (org.). Territórios contestados: o currículo e os novos mapas políticos e culturais. 6. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2004. [ Links ]

TOURINHO, I. Imagem, identidade e escola. Salto para o futuro: Cultura Visual e Escola, ano XXI, Boletim 9, p. 9-14, ago. 2011. [ Links ]

TOURINHO, I.; MARTINS, R. Reflexividade e pesquisa empírica nos infiltráveis caminhos da Cultura Visual. In: MARTINS, R.; TOURINHO, I. (org.). Processos e práticas de pesquisa em cultura visual e educação. Santa Maria: Ed. da UFSM, 2013. p. 61-76. [ Links ]

TOURINHO, I.; MARTINS, R. Entrevidas das imagens na arte e na educação. In: MARTINS, R.; TOURINHO, I. (org.). Cultura das Imagens. Santa Maria: Ed. da UFSM, 2012. p. 9-13. [ Links ]

TOURINHO, I.; MARTINS, R. Circunstâncias e ingerências da Cultura Visual. In: MARTINS, R.; TOURINHO, I. (org.). Educação da Cultura Visual: conceitos e contextos. Santa Maria: Ed. da UFSM, 2011. p. 51-68. [ Links ]

YOUNG, M. Para que servem as escolas? Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 28, n. 101, p. 1287-1302, set./dez. 2007. Available at: https://edisciplinas.usp.br/mod/resource/view.php?id=3220459&forceview=1. Accessed on: Mar. 10, 2022. [ Links ]

1This work was carried out with the support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Funding Code 001.

2English version by Janete Bridon, E-mail: deolhonotexto@gmail.com and Louise Potter, E-mail: louise.potter@yahoo.co.uk.

6Available at: Laboratório Imagens da Justiça (ufpel.edu.br). Accessed on: Dec. 6, 2021. This article is linked to the research project “Images of Justice, Curriculum Representations and Legal Pedagogy: a comparative study”, funded by The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq (Process nº 423497/2021-9).

8It should be noted that in the Diário Catarinense newspaper, from Santa Catarina state, the last strips by Armandinho were published in 2019.

9Available at: < https://m.facebook.com/tirasarmandinho/?locale2=pt_BR >. Accessed on: Jul. 5, 2021.

10Speech retrieved from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) website, where the illustrator gave a lecture on March 20, 2020. Available at: https://www.unicamp.br/unicamp/noticias/2018/03/22/alexandre-beck-criador-do-armandinho-fala-sobre-sua-arte-e-direitos-humanos. Accessed on: Jun. 11, 2021.

11It is a concept attributed to Boaventura de Sousa Santos that deals with the destruction of knowledge, knowledge and cultures not considered valid by the Eurocentric culture.

12According to Boaventura Santos (2020, pp. 26 - 27), “the epistemologies of the South affirm and value this way the differences that remain after the elimination of power hierarchies. The epistemologies of the South intend to show that what the dominant criteria of valid knowledge in Western modernity are, by failing to recognize as valid other types of knowledge beyond those produced by modern science, gave rise to a massive epistemicide, that is, of an immense variety of knowledge that prevails, especially on the other side of the abyssal line - in societies and colonial societies”.

Received: December 01, 2022; Accepted: May 01, 2023

texto em

texto em