Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensaio Pesquisa em Educação em Ciências

versão impressa ISSN 1415-2150versão On-line ISSN 1983-2117

Ens. Pesqui. Educ. Ciênc. vol.24 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 05-Abr-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21172022240109

Article

FROM THE FORMATION DIARY TO THE SYSTEMATIZATION OF EXPERIENCE: THE PROCESS OF (SELF)FORMATION OF SCIENCE TEACHERS

1Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Programa de Pós-graduação em Ensino de Ciências e Educação Matemática, Londrina, PR, Brasil.

2Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul, Programa de Pós-graduação em Ensino de Ciências, Chapecó, SC, Brasil.

In this article we seek to understand how the self-training process of Science Teachers takes place and how this process is related to the Formation Diary, the writing of reflective narratives and the Systematization of Experiences, mechanisms triggered by the Research-Formation-Action. We carried out a qualitative approach research based on 15 Formation Diary of Science Teachers in continued education, analyzed on the light of Textual and Discursive Analysis. The results point to the understanding of the Formation Diary as a Space for Systematization and Resignification of Experiences, evidence was found that the process of teacher education is brought about through the reflective advance on practices and on their own formation, and this investigation is made possible by the process of Systematization of Experiences. We defend the relevance of the Research-Formation-Action in collectives for the formation of Science Teachers, with the Formation Diary and the Systematization of Experiences being potentiating elements for the development of critical reflection and teacher self-formation.

Keywords: Research professors; Science teaching; Action research

No presente artigo buscamos compreender como ocorre o processo de autoformação de Professores de Ciências e como este processo está relacionado com o Diário de Formação, a escrita de narrativas reflexivas e com a Sistematização de Experiências, mecanismos desencadeados pela Investigação-Formação-Ação. Realizamos uma pesquisa de abordagem qualitativa com base em 15 Diários de Formação de Professores de Ciências em formação continuada, analisados à luz da Análise Textual e Discursiva. Os resultados apontam para a compreensão do Diário de Formação como Espaço de Sistematização e Ressignificação das Experiências, foram encontrados indícios de que o processo de formação de professores é ocasionado por meio do avanço reflexivo sobre as práticas e sobre a própria formação, sendo essa investigação possibilitada pelo processo de Sistematização de Experiências. Defendemos a relevância da Investigação-Formação-Ação em coletivos de formação de Professores de Ciências, sendo o Diário de Formação e a Sistematização de Experiências elementos potencializadores do desenvolvimento da reflexão crítica e autoformação docente.

Palavras-chave: Professores investigadores; Ensino de Ciências; Investigação-Ação

En este artículo buscamos entender cómo se da el proceso de autoformación de los Docentes de Ciencias y cómo este proceso se relaciona con el Diario de Formación, la escritura de narrativas reflexivas y la Sistematización de Experiencias, mecanismos desencadenados por la Investigación-Formación-Acción. Realizamos una investigación de enfoque cualitativo a partir de 15 Diarios de Formación de Docentes de Ciencias en formación continua, analizados a la luz del Análisis Textual y Discursivo. Los resultados llevan a la comprensión del Diario de Formación como un Espacio de Sistematización y Resignificación de Experiencias, se encontraron evidencias de que el proceso de formación docente se produce a través del avance reflexivo acerca de las prácticas y acerca de su propia formación, y esta investigación es posible gracias al proceso de Sistematización de Experiencias. Defendemos la relevancia de la Investigación-Formación-Acción en los colectivos para la formación de Profesores de Ciencias, siendo el Diario de Formación y la Sistematización de Experiencias elementos potenciadores del desarrollo de la reflexión crítica y la autoformación docente.

Palabras clave: Docentes investigadores; Enseñanza de las ciencias; Investigación-Acción

INTRODUCTION: INVESTIGATING THE EXPERIENCE

Over the last decades, the fields of education and teaching have recognized the importance of narratives as a research methodology for teachers’ personal and professional development (Radetzke, Güllich & Emmel, 2020). The advocacy for teacher education processes with emphasis on the development of researchers of their own practice has been advocated for more than three decades (Porlán & Martín, 2001; Alarcão, 2010). As a result, teacher education courses are turning to the training of professionals with a habit of reflection and self-reflection (Nóvoa, 2009). Moreover, written records of professional practices and individual experiences are being seen as essential for teachers to acquire greater awareness of their work and identity as teachers (Nóvoa, 2009; Alarcão, 2010).

In these training courses, the Action-Research process has been used as a model that favors the development of teachers’ reflection skills (Imbernón, 2010; Kierepka & Güllich, 2016). This model is based on practical knowledge through reflective processes, showing itself as an alternative to teacher training centered on technical rationalist thinking, in which lectures, workshops, and short courses focusing on training, improvement, recycling, and only conceptual review stand out (Carr; Kemmis, 1988; Domingues, 2007; Imbernón, 2010; Kierepka & Güllich, 2016). This Action Research model can be categorized by cyclical movements, which, in the logic of a self-reflective spiral, go through steps such as: observation, problematization, planning and action, which are always permeated by reflection processes (Alarcão, 2010). We also advocate the possibility of two other stages to stand out during the self-reflective spiral: the evaluation and the modification - which indicate the beginning of new self-reflective spirals, since they occur through the redefinition of the practice (Radetzke, Güllich, & Emmel, 2020). We consider these steps as crucial to the Action-Research model, as they imply a reflective observation in, on, and for teaching action (Alarcão, 2010).

However, Action-Research is not only a method or model, but a possibility for reflection-action and decision-making, as this process leads the teacher to rethink their own practices, with the aim of (re)meaning the educational work through critical reflection (Domingues, 2007). Thus, this investigation, which is supported by critical reflection, is being built through the narratives, and becomes formative to the investigating teacher.1 Therefore, in view of the process of teacher training and professional development, the concept of investigating teaching action is extended to Research-Training-Action of the teacher who writes/investigates his conceptions and practices (Alarcão, 2010; Güllich, 2013).

Regarding the process of investigation of one’s own pedagogical practice, which occurs through reflection on teaching action, the development of reflective narratives has been attributed as a tool for teacher formation/constitution (Ibiapina, 2008). Imbernón (2010), in line with Nóvoa’s (2009) ideas, reveals the concept of teacher identity as a space for the construction of ways of being and being in the teaching profession, a process that requires time. Thus, the teacher identity is constituted by the actions of each teacher, therefore, it is relevant to encourage the development and adherence to the process of writing reflective narratives in continuing education collectives. A process that we can also call shared reflective writing (Dattein, 2016) as we are narrating our experiences collaboratively, from the training collectives.

According to Güllich (2013), it is through reflective writing that teachers reflect, develop, and investigate their practice. Thus, regarding Research-Training-Action, the Training Diaries add formative potential to the professional development process, from the perspective of teacher constitution. The Training Diary is the methodological resource that can guide the process of investigating practice, because its recurrent use allows the teacher to reflect, in an individual way, about his or her conceptions and reference paradigms, his or her methodology in the classroom, and provides the formation of the reflective habit, constituent of being a teacher (Porlán; Martín, 2001; Alarcão, 2010; Güllich, 2013).

As Zabalza (2004, p. 27) points out: “class diaries [...] constitute valuable resources of action research capable of establishing the curriculum of improvement of our activities as teachers”. As teachers reflect on their practices and contextualize them by trying to understand them from a theoretical point of view, the Training Diary also favors the connection between the knowledge acquired in theory and practice (Porlán & Martín, 2001). Also, Boszko (2019), after a theoretical and practical study on diaries, presents and conceptualizes the perspective of the learning diary, having a fundamental meaning by becoming “a narrative space of the subject’s thinking about the learning process in which he is immersed” (Boszko, 2019, p. 30), as a way to unite the processes of concept formation and teacher-investigator training.

Beyond the writing of reflective narratives, the processes of continuing education, which are experience-based, are enhanced by triggering a triple dialogue. Which, in the words of Alarcão (2010), consists of “a dialogue with oneself, a dialogue with others, including those who before us built knowledge that is a reference, and the dialogue with the situation itself, a situation that speaks to us” (Alarcão, 2010, p. 49), thus favoring the training of the investigating teacher. Thus, the writing of reflective narratives should be articulated to processes of dialogue and shared reflection, since the collective reflection on the narratives provides an opportunity for awareness about other perspectives in relation to our teaching.

Therefore, for the Inquiry-Training-Action to occur in teacher education collectives, the subjects need to be willing to analyze their own teaching practice (Marcelo, 1992), making use of the Training Diary as a tool for the development of reflective narratives, and to be open to a triple dialogue. The active participants of an Action-Research are led to mobilization, searching for new planning, actions and reflections arising from the research questions/problem that each one presents in the training/investigation/action collective (Rosa & Schnetzler, 2003). The investigation of one’s own practice, through reflection, ends up triggering the production of teaching knowledge in relation to the teacher’s action, as it allows a constant (re)construction of identities (Kierepka & Güllich, 2016).

In view of this, we emphasize in relation to training processes, that these should be focused on linking training and teacher professional development in a practical context, thus producing the teaching profession. They should be articulated to curriculum development to produce the school, having reflection as the learning principle and goal of training processes (Güllich & Zanon, 2020). Research-Training-Action becomes effective and is configured as it succeeds in transforming pedagogical practices, conceptions, school contexts, curricula, and even social practices (Carr & Kemmis, 1988; Güllich, 2013).

We also advocate, with emphasis on collectives and training processes, the potential of Systematization of Experiences. Although there is little consensus regarding the concept of Systematization of Experiences, most authors agree that Systematization of Experiences is a collective modality of knowledge production about practices of intervention and educational action (Falkembach, 1991; Jara, 2013), like Research-Training-Action. One of the objectives of the Systematization of Experiences is the production of knowledge that can expand the frameworks of action and understandings about the practices and can therefore consider systematization to obtain knowledge from real experiences (Morgan & Monreal, 1991).

Thus, the Systematization of Experiences is an element that enhances the Research-Training-Action, because it allows the socialization of the teaching knowledge, through the communication of experiences in groups of teacher training, making the other’s experience serve as learning for others (Falkembach, 1991). In the encounter with the other’s dialog, moments of awareness are allowed. In the process of reflection, it is possible to see what changes are needed in relation to our practice (Güllich, 2013). Thus, new teaching knowledge originates in the reflection on experiences, which, when externalized during the process of Systematization of Experiences, become collective. Thus, they allow the critical reflection, triggered on the practice, during the Systematization of Experiences, to enhance the practice itself (Falkembach, 1991; Jara, 2013). This teaching knowledge, which we seek in the process of Systematization of Experiences, needs to be public/shared, which presupposes the “dissemination of teaching knowledge through the publication and circulation of reports of experiences produced by teachers” (Suárez, 2014, p. 778).

In previous research, it has been found that, in Formative Cycles in Science Teaching (the situated context of our analysis), the process of Systematization of Experiences is able to trigger several elements considered formative, one of them being the writing of reflective narratives in the Formative Journal (Person, Bremm & Güllich, 2019). The knowledges that are analyzed during the Systematization of Experiences start from the reflective writing in the Training Diary, are put under analysis in the Experience Reports, follow through the dialogue among peers during the Systematization of Experiences, and return to the Experience Report in a more elaborate form (Bremm & Güllich, 2020a). Due to this reflective movement that the process of Systematization of Experiences triggers, we defend the concept of Systematization of Experiences as a macroprocess central to the triggering of Research-Training-Action in Science, because, from theoretical deepening, it is clear that the process of Systematization of Experiences in addition to triggering critical reflection develops the autonomy of the teacher, who starts to act in the search for improvements / transformations, giving new meaning to their teaching practice, contributing to the Research-Training-Action to be fully triggered (Bremm & Güllich, 2020b).

Knowing the importance of narrative writings for the reflective advancement of the investigating teacher and the relevance of the Training Diary as a methodological resource for the process of investigating practice, we developed this research with the aim of understanding how the process of (self)training (Inquiry-Training-Action) of science teachers occurs and how this process is related to the Training Diary - the writing of reflective narratives - and to the Systematization of Experiences - mechanisms triggered by the Inquiry-Training-Action, assumed in this text as Critical Inquiry-Training-Action in Science - considering that the situated context is also central in the analysis. Understanding that the phenomenological dimension is greater than the objectification, we present, as a focus of the problematic, to understand and interpret by the emerging argumentation: what is shown in the Training Diaries of Science teachers who are researchers during a process of Systematization of Experiences that is supported by the Critical Inquiry-Training-Action in Science?

METHODOLOGY: BUILDING AN INVESTIGATIVE PROCESS TO UNDERSTAND THE PHENOMENON

The Federal University of the South Border (Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul -UFFS), through the Group of Studies and Research in Science and Mathematics Teaching (GSRSMT), develops the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching as an Extension Program and as a continuing education action. This

as a teacher education model and follows the principle of the interactive triad (Zanon, 2003) that enables a collaborative and shared education. Participating in the training meetings are teachers in initial training, teachers of Basic Education and teacher educators from the university, all of whom make use of the Training Diary as a space for reflection and investigation of their practice.

In addition to training meetings with pedagogical themes, conceptual updates in science, moments that prioritize the development of the Systematization of Experiences are also held. In 2019, the Systematization of Experiences occurred in small groups that were separated into rooms according to similarities in the theme of their Experience Reports, to allow greater interaction among the research teachers. Of these groups, we chose one that was dedicated to the themes: first lesson developed and experimentation. This group was named “Blue Room” to do the analysis of the Training Diaries. In this work, we analyzed, preliminarily, 15 Training Diaries of the teachers’ investigators of the Blue Room, composing our research corpus.

Textual and Discourse Analysis was developed by Moraes (1991) through the encounter between phenomenology, naturalistic research, existentialism, and existential hermeneutics. Phenomenology is a form of research that is characterized by the direct approach to phenomena, it studies how phenomena present themselves to consciousness, valuing subjectivity as a way to reach the essence of the phenomenon (Moraes, 1991). “Reaching the essences or ideas of phenomena is associated with eidetic reduction and phenomenological reduction, through which we can leave the reality of facts and reach the reality of ideas” (Moraes, 1991, p. 21). To reach the essence is to reach understanding, which is never definitive, but is in the process of becoming (Moraes, 1991).

Phenomenology considers the experiences of the investigating teacher as the origin of all knowledge, in which language has a significant role. For phenomenology, “realities are constructed according to the different points of view and questionings of the subjects” (Moraes, 1991, p. 22) and, thus, language has a relevant role not only for teacher-investigators to express their different points of view, but it is intrinsically linked to the construction of the reality of these teacher-investigators (Moraes, 1991). Therefore, phenomenology seeks the essence of the phenomena from people’s experiences, which are ordered by language. In this way, the investigation must start from the oral or written manifestation of the investigating teachers (Moraes, 1991). This hermeneutic circle of investigation “propitiates the gradual and progressive unveiling of new veiled layers, leading to an increasingly deeper understanding of the phenomenon” (Moraes, 1991, p. 24).

Bearing in mind the understandings, already situated, we arrive at the proposition of Textual and Discourse Analysis (Moraes, 2003; Moraes, Galiazzi & Ramos 2004; Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011), which is characterized by a methodological action that seeks to detach itself from the epistemic reductionism characteristic of the Natural Sciences (Moraes, 2003). Therefore, Textual and Discourse Analysis can be characterized as a qualitative data analysis methodology, but more than that, a theoretical-conceptual and methodological contribution that seeks the understanding of phenomena in contents and discourses. Based on the analysis of reflective narratives written in the Training Diaries of the research teachers, participants of the Training Cycles in Science Teaching, we seek to understand the phenomenon: what is shown in the Training Diaries of science teachers who are researchers in the midst of a process of Systematization of Experiences that is supported by the Critical Inquiry-Training-Action in Science?

Thus, the analysis undertaken in this research was the Textual and Discourse Analysis, described by Moraes and Galiazzi (2011) as research of three stages, being them: the Impregnation or Unitarization, the Self-Organization or Categorization and the Exploration of meanings or Production of Metatext (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011). The first stage of Unitarization consisted of deconstructing/fragmenting the reflective narratives found in the Training Diaries until they formed several Meaning Units. With this first step, we intended: “to be able to perceive the meanings of the texts in different limits of their details, although it is known that a final and absolute limit is never reached” (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011, p. 18).

The Unitarization step depends on the goal of the researcher who will select Meaning Units that are able “to produce valid and representative results in relation to the investigated phenomena” (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011, p. 17). Thus, we searched for evidence that pointed to the importance of the Training Diary as a space for individual training and its relationship with the triggering of the writing/elaboration of the Experience Reports, also verifying the relevance of the Training Diary as a space for reflection and Systematization of Experiences.

The second step is the Categorization, in which we search for relations among the Meaning Units to combine them by similarity and categorize them. This process occurred through readings and re-readings of the Units of Meaning, thus forming initial categories that are again grouped into intermediate categories until reaching the final categories, being this an intense interpretive/hermeneutic work of search for the emergence of categories, in which a Unit of Meaning can compose more than one category (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011). From then on, it was possible to start the final stage of the cycle which is the Production of Metatext, which is characterized in an effort undertaken by the researcher to present the new understandings that were produced as a result of the previous steps, i.e., “the set of categories constitute the elements of organization of the metatext that one intends to write. It is from them, that the descriptions and interpretations that will compose the exercise of expressing the new understandings made possible by the analysis will be produced” (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011, p. 23).

We emphasize that, according to Elliott (1998), Action-Research can be presented in two forms, being the first-order Action-Research the one performed by teachers who reflect on their practice, while the second-order Action-Research is performed by the academic researcher who analyzes the first. Therefore, the teachers, when writing reflective narratives in their Training Diaries, are performing an Action-Research process on their own practice (first order) and we, the authors of this text, when analyzing the content of these Training Diaries, are performing a second order Action-Research process. In view of this, the participants of this research were considered by us as teacher-investigators, since this designation refers to the practice that is conducted by teachers.

In relation to the Training Diaries analyzed, ten belonged to teachers in initial training, among these, nine were undergraduate students in Biological Sciences who were attending between the fifth and the seventh phase of the course, most of them in the fifth phase. One undergraduate student was studying Chemistry and was in the third phase. Regarding the teachers who work in Basic Education schools, four Training Diaries were analyzed, three of these teachers had a degree in Biological Sciences and one in Chemistry. Of the four Basic Education teachers, two had post-graduate degrees, one a Master’s in Science Education and the other a specialization in Interdisciplinarity. The teacher trainer, whose Training Diary was analyzed, holds a bachelor’s degree in Biological Sciences, a master’s degree, and a PhD in Science Education.

Regarding the time of participation in the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching, the teachers who were still in initial training had between six months and three years of participation, most of them for one year. The Basic Education teachers had six to nine years of participation in the continuing education project, and the teacher trainer also had nine years of participation, and this was the maximum time possible, since the project began in the year 2010 and the process of systematization of the Experience Reports, as well as the collection of the Training Diaries occurred in 2019.

The teacher researchers participating in the Systematization of Experiences, which took place in the blue room, delivered the writings contained in their Training Diaries and freely agreed to participate in the research, authorizing the collection and analysis of their narratives, by signing the Informed Consent Form. Following the research ethical precepts, their names were replaced by the expression “TDTT” for the Training Diaries of teacher trainers, “TDBE” for the Training Diaries of Basic Education teachers, and “TDTIT” for the Training Diaries of teachers in initial training, followed by an identification number, to preserve their identities.

LIVED DIARIES, OPEN DIARIES AND EXPERIENCED DIARIES

From these understandings and our interpretations of the experiences emerges our metaphor of support to expand the dialogue in a path of comings and goings from practice to theory and vice versa, expressed here as: diaries lived, open diaries and experienced diaries, which portray marks, movements and times of training and teaching. We will now explain the elements of the metaphor that we developed and that will allow us, throughout the analysis, to expand the interpretation, the argumentation, the comprehension and the dialogue in relation to the Systematization of Experiences and the Training Diaries: i) Lived Training Diaries: we use this denomination for the excerpts in which we find elements linked to the idea that the Training Diary is a space of description directly linked to the practice, having as its role that of originating the Experience Reports, being, therefore, the birthplace of this investigation of the practice and, consequently, of the Systematization of Experiences process; ii) Open Training Diaries: represent the excerpts in which we can identify the sharing of the practice through the reading of the Training Diary or the Experience Report during the Systematization of Experiences (in the context investigated here: the blue room), in which the individual reflection contained in the Training Diary is reflected collectively and, subsequently, returns to the Training Diary or Experience Report through their rewriting; iii) Experienced Training Diaries: represented by the excerpts in which it is verified what the process of Systematization of Experiences, through the reading of the Training Diary or Experience Report, makes possible in terms of research on practice: present collective knowledges, learnings that are arising from the Systematization of Experiences and contribute to the teaching constitution, to the curriculum development and to the teaching professional development of the research teachers.

The production of the final category represents the new understandings arising from the analysis in an argumentation process in which the emerging defenses and propositions are presented (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011). Thus, the final category: Training Diary as a Space for Systematization and Resignification of Experiences , allowed us to develop a central synthesis (metatext), which is our first argumentation/formulation, that is, the presentation of the defense: The process of teacher training through writing in the Training Diary is expanded by reflecting on the practices and training, on which the process of Systematization of Experiences is central. Since, in the Training Diaries, the investigating teachers use the theories and conceptions that involve their training to be able to overcome problems and achieve goals in relation to their practices. Moreover, the importance attributed to the Training Diary for the construction of the Experience Report presupposes the intentionality of sharing and collective reflection, indicating the relevance of the Experiences Systematization movement for the re-signification of practice.

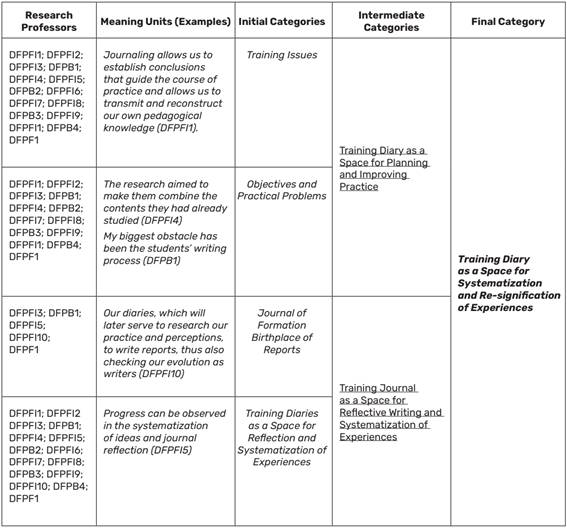

The production of the results, from a phenomenological perspective, following the principles of Textual Discourse Analysis, began with the fragmentation/deconstruction of the research corpus, originating 128 Meaning Units, which were selected in the search for understanding the process of (self) training of Science teachers and how this process is related to the Training Diary, to the writing of reflective narratives and to the Systematization of Experiences, which was developed in a context of Research-Training-Critical Action in Science. To build the categories, we considered the most recurrent indications found in the Meaning Units, at which point we rescued the understanding that the categories comprise “options and constructions of the researcher, valuing certain aspects over others” (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011, p. 139). From these Meaning Units, four initial categories emerged that were grouped into two intermediate categories, later regrouped into a final category.

The metatext is a movement of theorization that seeks to validate the emerging categories (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2011). Therefore, it is based on all categories that were formed throughout the analysis process and come together to form the new conceptions arising from the initial fragmentation process. In the construction of the metatext, we present the agglutinating arguments that allowed the formation of categories, which are organized around the central theme of the research and denote important aspects emerging from the analysis process. The Meaning Units, which are part of the research corpus, point to the Systematization of Experiences and the production of reflective narratives in the Training Diaries as ways to develop the Research-Training-Action, because the Systematization of Experiences “gives individuals the possibility to articulate, through the narratives they produce about themselves, the reference experiences they went through, giving meaning to their own professional trajectory” (Passeggi, Souza & Vicentini, 2011, p. 378).

The analysis of the lived, open, and experienced Training Diaries allows “to perceive, ascertain, make explicit, incorporate and better understand contradictions, resistances and changes in the teachers’ stance from the discourse that expresses their teaching practice” (Radetzke, Güllich & Emmel, 2020, p.70). To facilitate the reader’s understanding regarding the movement of category construction, we present below Box 1, in which we can verify the identification of the research teachers, the initial, intermediate, and final categories, as well as examples of the Meaning Units that formed each category.

The intermediate category, entitled Training Diary as a Space for Planning and Improvement of Practice , is composed of 81 Meaning Units, and was elaborated by grouping the initial categories: Training Issues; Objectives and Practice Problems. As an agglutinating argument for these two initial categories, we emphasize the possibility of taking a latest look by building the intermediate category of Planning and Improving Practice. With this, we argue that: teacher-investigators need to use the facts that involved their training and that broadened their conceptions and theories to continue training, so that they can overcome their problems in relation to practice and reach the goals that have not yet been achieved.

The possibility of agglutination between the two initial categories will become more evident in the following dialog between the initial categories and the theoretical framework. The initial category, entitled Training Issues , is composed of 56 Meaning Units. In it, teachers describe aspects of their training in relation to the pedagogical practices analyzed in the Training Diary: “practical classes facilitate the student’s understanding [...] but of course we can’t think that the student only learns in practice [... ] for a good understanding it is always possible to combine the two: theory and practice” (DFPFI1),2which is also visible in: “the knowledge and learning that the classroom brings to an educator is always indispensable in training and necessary for one to understand, diagnose and improve or contribute to advances in educational processes” (DFPB3). In the analysis of the Meaning Units, it is evident the investigative teachers’ dwelling on their actions, understanding the construction of knowledge beyond technical rationality (EMMEL, 2019). The investigation of one’s own practice is conducive to teachers’ awareness that, during this process of investigation, it will be possible to outline improvements and transformations in relation to teaching practice (Carr & Kemmis, 1988; Porlán & Martín, 2001; Autor2, 2013).

This category (Training Issues) was found in all the Training Diaries analyzed. The fact that teachers refer to aspects of their training during the writing of narratives in their Training Diaries already points to the aspect that this instrument is not only a space for describing events, but a space for reflection and teacher constitution (Porlán & Martín, 2001; Domingues, 2007; Reis, 2008). This brings up again the reference to the lived Training Diary since the Meaning Units denote the Training Diary as a space for reflection and a path for the beginning of the investigation of practice. These excerpts point to indications of the importance of the investigation of pedagogical practice and the reflection processes involved in this investigation for the movement of teacher-researcher constitution, in which “the diary is a great instrument in our training” (DFPFI1). The Research-Training-Action, when allied to the teaching action, ends up becoming mediator of these formative processes, instigates us to share our own practice, to research about it and improve it (Alarcão, 2010; Güllich, 2013). This happens through reflection on the action, in retrospective character, in the action and to improve the action, in prospective character (Alarcão, 2010). By re-signifying and broadening the understandings about the problems of practice, this awareness, as we see in the following excerpts, allows the ascertainment of viable solutions and reference models (Porlán & Martín, 2001; Person, Bremm & Güllich, 2019).

As pointed out earlier, for teacher education to occur, according to the assumptions of the Research-Training-Critical Action in Science model and culminate in the transformation/resignification of teaching practice, teachers in formation need to be willing to investigate their own practice, becoming teacher researchers (Marcelo, 1992). These teachers, by proposing to participate in the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching, demonstrate this willingness to change, through the writing of the Formative Journal and the analysis of the practice, developing an investigation based on their own and other teachers’ research.

Being willing to investigate one’s own practice denotes the beginning of a Research-Training-Action process, as it is the first stage of the self-reflective spiral. The achievement of the other stages happens throughout the investigation and the process of writing reflective narratives (Radetzke, Güllich & Emmel, 2020). The challenge of the Research-Training-Action process is to reach the modification stage, since it represents a complete turn in the self-reflective spiral of the investigating teacher, which, as a result, implies the re-signification of the practice and the proposition of new cycles, triggering new problematizations and understandings that serve as a guide for the next experiences (Radetzke, Güllich & Emmel, 2020).

The intermediate category Training Diary as a Space for Planning and Improving Practice also comprises the initial category, entitled: Objectives and Practice Problems , which portrays 25 Meaning Units. In this category, teachers are able to guide the goal or the practical problem of the activity described in the Training Diary: “form citizens capable of questioning and knowing how important is the flora and fauna, that environmental education goes far beyond knowing how to separate the trash” (DFPFI7), or even the goal of the Experience Report: “this experience report aims to present and discuss the experience of developing a lesson plan” (DFPFI3). This category is formed by Meaning Units that were found in 13 of the 15 Training Diaries analyzed and demarcate focuses about the importance of the Training Diaries as a guide for the planning and organization of the practical activity, culminating in its improvement (Porlán & Martín, 2001). Many of these Meaning Units had the characteristic of being focused on the methodology of the investigated practice: “during the video, we asked the students to pay a lot of attention to things in their daily lives” (DFPFI2). Moment in which, once again, we find the perspective of the lived Training Diaries, since the Meaning Units present the Training Diary as a space of more direct description of the action, centered on the methodology of practice. However, this does not diminish these reflective narratives, since they can be considered as a practical way of being a teacher, putting into discussion the action itself (Radetzke, Güllich & Emmel, 2020). Through the Research-Training-Action process of teacher researchers, the written experiences are analyzed and conceptualized, becoming a guide for new experiences (Güllich, 2013).

Such aspects highlighted by the teacher-researchers in their Training Diaries give us indications that they teach Science so that their students have another way of interpreting the world, and that they are already leaving a little aside the idea that one teaches Science to give the student knowledge of the world or to improve the way this student conceives it:

It is these codes that we need to make accessible to the new generations so that they do not become blind consumers of the technological goods produced by science, but, understanding its mechanisms of domination and persuasion, can reject them when they contradict their ethical, aesthetic, and political values (Chaves, 2007, p. 18).

The Training Diary allows the perception of the advances in the training process while it becomes a guide for the practice of reflection. This occurs through the process of (re)reading of practice that the narrative writing process of a class allows. As the teacher-researcher-in-training narrates his lesson, he is led, little by little, to begin a process of explanation and reflection on the narrative of this lesson, going beyond the simple description and analyzing the causes and consequences linked to the content, context, and methodology of the lesson (Porlán & Martín, 2001). This is emphasized by the Basic Education teacher in the following excerpt: “reflective diaries can serve as a guide for practice and especially for training, what I got right and what I got wrong [...] so action research is a possibility, investigate one’s own practice, improve it and also dialogue with references” (DFPB1). Which demonstrates that the writing of the Training Diary can be taken as a formative movement, characterized by the practice of authentic Research-Training-Action, and the research of one’s own practice/first-order action-research (Elliott, 1998; Güllich, 2013). In addition to being a formative process, the analysis of practice problems is pointed out by teacher researchers as a process of teacher constitution “a personal investment on one’s own constitution” (DFPB1).

The second intermediate category, entitled Training Diary as a Space for Reflective Writing and Systematization of Experiences , comprises 47 Meaning Units. This category was elaborated by grouping the initial categories, Training Diary as the Birthplace of Reports and Training Diary as a Space for Reflective Writing and Systematization of Experiences. As an agglutinating argument for these two initial categories we point out that they allowed us to take a new look, building the intermediate category of Training Diary as a Space for Reflective Writing and Systematization of Experiences, we point to the defense that: the teacher researchers, by expressing in their reflective narratives the importance of the Training Diary for the construction of the Experience Reports, are already indicating a subsequent movement of Systematization of Experiences in the collective, since, the construction of an Experience Report presupposes the purpose of sharing and collective reflection, enabling the movement of rewriting of the reflective narratives.

In the argumentation process, we can see this defense in the presentation and discussion of the Meaning Units and the initial categories. The initial category Training Diary, the origin of the Reports, comprises 12 Meaning Units and was present in five of the 15 training diaries analyzed, and three of these five were from teachers in initial training, a fact that confirms the importance of the other and of the continuous training process they participate in. This initial category comprises Meaning Units that account for the importance of the Training Diary as a space for describing practical activities, serving as a starting point for the construction of the Experience Reports, perceptible in: “from the diary to the report, the investigation persists” (DFPB1). The Training Diary also allows to return to the memories and the description developed about a certain pedagogical activity carried out, about the own training in the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching, about the participation in the group, in the discussions and even in the readings in the area, triggering a reflective cycle proper of who writes (Güllich, 2013), as we can observe in: “I consider the logbook essential for teachers, when writing down their teaching methodologies, it will enable him [referring to the Training Diary] to go back and redo them, point out his results and then reread, being able to improve and [even] publish as a report” (DFPFI3). In these Meaning Units, we again find the reference to the Experienced Training Diary, since the Training Diary, through the reflective narratives, ends up originating the Experience Report, which contributes to the investigation of the practice and the Experience Systematization process.

For Alarcão (2010), writing is an encounter with us and the world around us, and narratives become richer as we can record more significant elements of our practice. Therefore, the Training Diary “allows the development of a deeper level of description” (DFPFI9), which is visible in: “at the beginning my writings about the classes were merely descriptive, which as the course went on became more reflective and critical. I realized this by comparing my writings from the beginning of the degree until now, through the logbooks” (DFPFI9).

As a result, the Training Diary becomes a tool for the birth of reflection/action research. As can be verified in the excerpt of the teacher in initial training: “in my report, I try to reflect on my certain evolution in writing and I bring as my main focus the use of logbook, because it is this material that has helped me in writing and from that I see the importance of reflection of reading and writing” (DFPFI10). The teacher in question is able to perceive the importance of the Training Diary as a tool for research, reflective evolution and narrative writing, and the Training Diary is her contribution to the writing process of her Experience Report, a space in which she does not only analyze her practice, not only her practice, but her evolution as a teacher and the way the Training Diary constituted her over time.

Other researches conducted with teacher researchers participating in the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching already pointed to the importance of the Training Diary in the process of writing the Experience Reports (Bremm & Güllich, 2020a). This reflective movement that occurs in the Training Diary allows the teacher to take back to himself the formative dialogue developed in the training group, reflecting on his action, that is, taking ownership of his training process. Due to the possibility of reminiscing, which facilitates the elaboration of the Reports of Experience, a second moment of individual reflection occurs that tends to be more critical and can already be understood as Research-Training-Action of the teacher (Güllich, 2013; Bremm & Güllich, 2020a).

We can also notice that teachers, who consider the Training Diary as the cradle for the construction of their Experience Reports, point to the investigative process occurred during this movement: “in the diaries, we produce our experience reports, which are the most authentic means of investigating one’s own practice, of investigation-training-action” (DFPB1). Teacher researchers, by writing reflective narratives, can advance in their Research-Training-Action process, bringing during their reflections the idea of investigation of one’s own practice as a practical/reflective process (Carr & Kemmis, 1988). The Training Diary allows the development of reflective narratives, becoming a space of investigation of practices and conceptions, being part of their teaching constitution (Güllich, 2013). This can be perceived in this teacher’s writing: “the diary shows us how to analyze memories to progress and write accounts” (DFPFI5), “thus also conferring our evolution as writers” (DFPFI10).

The intermediate category Training Diary as a Space for Reflective Writing and Systematization of Experiences also comprises the initial category, entitled: Training Diary as a Space for Reflection and Systematization of Experiences , which comprises 41 Meaning Units, which were found in 12 analyzed Training Diaries. This category comprises Meaning Units in which teachers denote that over time that: “the diary ceases to be only a written record and becomes an organizer of a reflective inquiry” (DFPFI1) which meets Kierepka and Güllich’s (2017) advocacy on the relationship of the levels of reflection described by Porlán and Martín (2001) with the advancement of conceptions and Critical Inquiry-Training-Action in Science. In addition to being a space for reflection, the Training Diary is also presented as an instrument for training and systematization of knowledge, as it is exposed in: “the logbook is likely to build the teacher subject, because in it we learn, reflect on practices and systematize knowledge” (DFPFI4).

The Training Diary is a space for reflection and research on one’s own practice and training (Research-Training-Action), since “the reflective writing in the diary helps to improve our insertion practices in schools as well as the teacher training itself” (DFPFI2). Therefore, the Training Diary is an “instrument that assists in the research process [...] it is a guide for reflection on pedagogical practice [and] we can consider the diary as the precursor instrument of classroom research and reflection of practice” (DFPFI10). Through reflective writing, the teacher plans his/her practice, thinking about its goals and problems, revisiting it in a second moment of reflection for the construction of Experience Reports, which culminates in the improvement/ re-signification of practice. This second reflection tends to be more critical and can be understood as an investigation of the teacher who writes, and this investigation is made possible by the Systematization of Experiences and the knowledge developed during the writing of reflective narratives in the Training Diary. Therefore, “one of the constitutive elements of continuing education is the systematization of our practices” (DFPB2).

In addition to being constitutive of teacher education, the Systematization of Experiences requires collective dialogues. dialogues that are considered by teacher researchers as “unique, that when not recorded [can be considered as] empty experiences, not reflected, not kept” (DFPB1), which is in line with Güllich’s (2013) thought. In this sense, teacher researchers demonstrate that they recognize “the importance of reporting experiences, of learning about [their] practice and also about their colleague’s practice” (DFPB1). Through the formative dialogues triggered by the Experience Report during processes of Systematization of Experiences, the research of one’s own practice “enables the re-signification and a critical and reflective action” (DFPB1). Thus, gradually “the writing of the journal may establish a new way of teaching” (DFPFI5), transforming and re-signifying not only the practices, but also the teacher-researcher constitution. In these Meaning Units, we found references to open Training Diaries and to experienced Training Diaries, since we perceived that the sharing of practice allows learning during the reflection processes on our practice and with the practice of the fellow teacher, as mentioned in DFPB1. Thus, the individual reflection, contained in the Training Diary, after being systematized and reflected in the collective, returns to the Training Diary or Experience Report through its rewriting. It is during this process that “systematization becomes an instrument capable of contributing to the broader perception of the reality experienced and the implications that individual and collective actions have” (Lottermann, 2012, p. 93).

Thus, we also noticed, in the Meaning Units already presented, that, regarding the Experienced Training Diaries: the process of Systematization of Experiences of the reflective narratives of the Training Diaries or Experience Reports enables the investigation on the practice, the construction of knowledge about the practice in the collective through reflection and dialogue about the narratives read, as we can see in: “[. ...] this makes us understand that perspective we heard about the hidden curriculum” (DFPFI10) and “the practical knowledge that has been built has been positively surprising me” (DFPFI10). It is evident that the Systematization of Experiences makes use of “the experiential knowledge capable of proposing reflections on the actions that occur in the workplace, considering the problems that arise from the teacher’s practice, from their work, in the reflection for exits from the pedagogical intercurrences” (Rosa, 2016, p. 50).

Therefore, the learnings that are arising from the Systematization of Experiences contribute to the teaching constitution, to the curriculum development and to the teaching professional development of the research teachers, since “[...] the discussions are being both formative for the teaching development and also for the construction of knowledge [...] in a collaborative way we advance” (DFPB1). In this sense of diary: the experienced Training Diaries are, in turn, contained in the lived Training Diaries and the open Training Diaries, since the latter are collected in the former, just as the initial categories in the intermediate ones and the latter in the final category. Thus, we can perceive the capacity of the Systematization of Experiences in

transform the experience into an object of reflection and study, where the participation of those involved in the process allows enriching the reflections and the information about the object of study through discussions and collective learning from the singular experiences (Cirino, 2008, p. 3).

There are diverse ways in which teachers learn and, more especially, learn to teach, considering the different contexts in which they are embedded, since the heart of teaching lies in the teacher’s ability to be intelligent and flexible (Shulman & Shulman, 2016). In view of this, it is essential that the teacher learns to adapt from practical experience. In this sense, “critical analysis of one’s own practice and critical examination of how well students have responded to that practice are central elements of any teaching model. At the heart of such learning is the process of critical reflection” (Shulman & Shulman, 2016, p. 129).

When the investigating teacher sets out and is willing to learn from experience, through reflection, they become more aware of their actions, knowledge, practices, and dispositions (Shulman & Shulman, 2016). Thus, we argue that in both initial and continuing education, it is incumbent upon teacher educators to create environments that (re)signify members’ understandings, views, motivations, practice, and reflections, considering the importance and interdependence of reflection at the individual and collective levels (Shulman & Shulman, 2016). It is noted that teachers can evolve in their reflections individually, but still need the impetus of a reflective community, which will make it possible to evaluate their conceptions collectively and will instigate the transformation of their practice into praxis (self-aware and critical) (Shulman & Shulman, 2016).

We agree with Lee Shulman and Judith Shulman when the authors state that “reflection is key to teacher learning and development” (Shulman & Shulman, 2016, p. 130). Since, throughout the analysis of the Training Diaries, it was possible to verify that the teacher researchers who had participated for longer in the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching, are more used to making use of the Training Diary as a tool for writing reflective narratives, they are the teachers who advanced the most during this reflection and scored the importance of the Training Diary as a space for teacher constitution (DFPF1 nine years; DFPB2 and DFPB3 six years; DFPFI4 three years; DFPFI10 two years) We can also notice, in general, that these were the teachers who wrote the most, that is, they had the habit of writing reflective narratives and, therefore, they have more Meaning Units collected.

However, we noticed some teachers who have been in the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching for a long time and who do not have the habit of writing reflective narratives in their Formative Diaries, presenting more simplistic reflections, characterized by descriptions of the practice in methodological terms (DFPB4 nine years) (Porlán & Martín, 2001). On the other hand, it was possible to identify teachers who have not been in the training group for so long and use the Training Diary, but who have already acquired the reflective habit and present more critical reflections (DFPFI1; DFPFI3; DFPFI5; DFPFI9). In these Meaning Units, we verify that “[...]practical and conceptual dilemmas about the issues that most [concern] as incidents, evaluations and interpretations are differentiated, the problem cores are forming” (Porlán & Martín, 2001, p. 31). Which demonstrates that reflective advancement depends on the constant habit of writing and (re)writing reflective narratives, and being so, is subject to advances and setbacks (Bremm & Güllich, 2018).

Therefore, taking into account the evidence of the importance of the writing of reflective narratives and the formative dialogue for the process of Research-Training-Action, the Systematization of Experiences is presented as a macroprocess that triggers the reflective narratives and the formative dialogue, therefore the Research-Training-Action (Bremm & Güllich, 2020a; Bremm & Güllich, 2020b). Since the exchange of experiences requires that the reflective narratives are externalized to the collective, triggering the processes of (re)signification of practice (Bremm & Güllich, 2020a). “When the process of inquiry is reflected upon and mediated, it becomes cyclical and developmental, allowing for the (re)signification of concepts and of pedagogical practice itself” (Radetzke, Güllich & Emmel, 2020, p.75).

Thus, the defense and proposition of the final category that represents the new understandings arising from the argumentation process is resumed: Training Diary as a Space for Systematization and Resignification of Experiences . Our agglutinating argument that allows the formation of this final category from the intermediary ones - which emerge from the initial ones previously presented -, resides in the fact that, throughout the analysis, in the production of results, we invested in the guiding question: what is shown in the Training Diaries of researcher science teachers in the midst of a process of Systematization of Experiences that is supported by the Research-Training-Action in Science? In this question, evidence is found that: the process of teacher education, in relation to the writing of reflective narratives in the Training Diary, is caused by means of reflective advance on the practices and on the training itself, and for this investigation to occur, the process of Systematization of Experiences in a situated context is central. Since the planning and consequent improvement of the practice, which are pointed out by the investigating teachers in their Training Diaries, are consequences of the writing process of reflective narratives and the Systematization of Experiences.

We can observe in relation to the co-created metaphor, that the initial categories: Training Issues; Objectives and Practice Problems; Training Diary Birthplace of the Reports present, in general, more excerpts of definition of the Training Diaries lived, since issues of the training of teacher researchers, problems and objectives are pointed out in relation to the practice that is being investigated. The Training Diary is presented as the birthplace of the writing that makes up the Experience Report of some of the teacher researchers participating in the research. The definitions of open Training Diary and experienced/public Training Diary are found in excerpts of the Meaning Units of the initial category Training Diary as a Space for Reflection and Systematization of Experiences, which presents “the writing of the experience made by several hands” (Lottermann, 2012, p. 19), made possible by the process of Systematization of Experiences in its triggered movements of reflection and (re)writing.

Deepening the understanding of the phenomenon, it is possible to realize that the open Training Diaries and the experienced Training Diaries are at the center. Because, from the reflective narratives written in the excerpts that characterize the Training Diaries lived, the movement of Systematization of Experiences and the collective reflection on the practice are initiated, thus developing a formative dialogue capable of giving new meaning to the practice, characterizing an open and/or experienced Training Diary. With this, advances are perceived in relation to teachers’ professional development, in relation to teachers’ knowledge and to the development of the curriculum, which in the reflection on, from, to, and in practice becomes a curriculum in action. Thus, we can think that both in the Training Diaries and in the teacher training process the experience is more practical, the public moment is more open, and the experience is more comprehensive and capable of transforming the teacher researchers.

Training processes (initial and continuing) that instigate the development of reflective narratives and moments of Systematization of Experiences, based on assumptions of Research-Training-Action/Investigation-Critical Training-Action in Science, enable reflective advancement and the redefinition of practices, culminating in improvements not only in the practices, but also in relation to the curricular and professional development of teachers.

SYSTEMATIZING: FROM DIARIES TO EXPERIENCES

The study presented here involves an analysis with a continuing education collective that makes use of the Research-Training-Action as a model of teacher education: Formative Cycles in Science Teaching. This collective, through Critical Inquiry-Training-Action in Science, reaches its formative dimension by instigating reflection processes in, about and for the formation/constitution of teachers with a view to (re)signification. The discussions contemplate the understanding of Research-Training-Action as necessary in science training collectives, in which the Training Diary presents itself as an instrument for the development of the reflective habit and for the advancement of this reflection, with the capacity to make it increasingly critical.

The analysis of the reflective writings produced in the Training Diaries by the research teachers participating in the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching in the Systematization Room “blue room”, allowed us to understand how the formation process of Science teachers occurs and how this process is related to the Training Diary, to the writing of reflective narratives and to the Systematization of Experiences, mechanisms triggered by Research-Training-Action.

The reflective narratives of the teacher researchers point to the Training Diary as a Space for Systematization and Resignification of Experiences. The intermediate categories could be agglutinated in this final category, since, in the intermediate category Space for Planning and Improving Practice (Training Issues; Goals and Practice Problems), issues of teacher training are pointed out in relation to the pedagogical practices analyzed, demonstrating the importance of the Training Diary as a space for knowledge construction and self-awareness about the teaching constitution, a space for investigation and self-training. When teacher researchers are willing to investigate their own practice, they are initiating their Research-Training-Action process. The achievement of the other stages of the self-reflective spiral of Research-Training-Action happens throughout the investigation and writing process of the reflective narratives. However, it is worth mentioning that the Training Diary is the space that allows the initial kick-off for the triggering of the Inquiry-Training-Action, because it allows the development and the habit of writing reflective narratives. Besides the training issues, the Training Diary is also pointed out as a space to analyze goals and problems in relation to the practice, demarcating focuses about the importance of the Training Diary as a guide for the planning and organization of the practical activity, culminating in its improvement, so it refers to a lived Training Diary.

These characteristics are related to those of the intermediate category Training Diary as a Space for Reflective Writing and Systematization of Experiences (Training Diary as the Birthplace of Reports; Training Diary as a Space for Reflection and Systematization of Experiences), in which we verify that the reflective narratives account that the Training Diary is very important for the birth of the Experience Reports, since it, as we saw in the previous category, is a space for the description of practical activities, serving as a starting point for the construction of the Experience Reports. This space allows us to return to the memories and to the description developed about a particular pedagogical activity conducted, about the training itself, triggering a reflective cycle proper to the writer. Besides being a space for reflection, it is also presented as an instrument of systematization of knowledge, which, in the Training Diary, occurs, at first, individually, characterized by being a written Systematization of Experience, which through dialogue in the collective is transformed into a shared Systematization of Experience, culminating in the construction of knowledge/teaching identities, in the professional development and curriculum, as this refers to and allows the understanding from the metaphor of being open Training Diaries and experienced Training Diaries. Our agglutinating argument for the two intermediate categories lies in the fact that planning turns to the consequent improvement of practice, which is pointed out by the investigating teachers in their Training Diaries, and which are consequences of the process of writing reflective narratives and the Systematization of Experiences.

Another relevant aspect of the research is situated in the fact that teachers who have been participating in the meetings of the Training Cycles in Science Teaching for the longest time, were the ones who most advanced in their reflective narratives and pointed out the importance of the Training Diary as a space of teacher constitution, having the writing of reflective narratives as a habit, giving rise to better understanding of what the open Training Diaries and experienced Training Diaries are. The teacher researchers who do not have the habit of writing reflective narratives in their Training Diaries, presented simpler reflections, descriptive and practical, being more like lived Training Diaries. Another point to be highlighted is the fact that the training group brings together teacher trainers, undergraduate students, and teachers from three courses: Biological Sciences, Physics and Chemistry. However, regarding the thematic room of Systematization of Experiences, called blue room, of the 23 participants, only two were from the Physics course, and, unfortunately, they did not provide their Training Diaries for the research.

We can infer that the process of action research and teacher education in science goes through the writing of reflective narratives in the Training Diaries. In a first moment, the investigating teachers describe their practice considering aspects of their training and begin a reflection process that is amplified during the writing of Experience Reports. Thus, we argue, based on the data in the literature of the area, on the research and training experience with the context of Formative Cycles in Science Teaching and based on the analysis presented here that it is the role of the Training Diaries is to serve as a space of systematization and re-signification of experiences.

Thus, we emphasize the importance of Research-Training-Action as a model of training in science teacher training collectives, because, by reflecting on one’s own practice and producing narratives, it becomes possible to evolve in terms of understanding about one’s own constitution and teacher training, and, through reflection and investigation, other possibilities take shape. We also emphasize that the Training Diary and the Systematization of Experiences are essential tools when the intention is to train investigative teachers through critical thinking, which seeks the best way to teach for the best way to learn. In this sense, the Training Diary allows the investigation of one’s own lived practice, the curricular development and the teachers’ self-training/professional development, and this self-training is made possible by the Systematization of Experiences written in the form of reflective narratives and by the developed/(re)meant knowledge, which become guides for new experiences, increasingly open and more experienced.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

CECIMIG would like to thank Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and Research Support Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) for the funding for editing this article.

REFERENCES

Alarcão, I. (2010). Professores reflexivos em uma escola reflexiva. 7. ed. São Paulo: Corteza. [ Links ]

Boszko, C. (2019). Diários de Aprendizagem e os Processos Metacognitivos: estudo envolvendo Professores de Física em Formação Inicial. (Dissertação Mestrado). Universidade de Passo Fundo, Passo Fundo. [ Links ]

Bremm, D. & Güllich, R. (2018). Processos de investigação-formação-ação decorrentes de narrativas em Ciências de professores em formação inicial: com a palavra o PIBID. Revista de Ensino de Ciências e Matemática, 9(4), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.26843/rencima.v9i4.1544 [ Links ]

Bremm, D. & Güllich, R. (2020a) O papel da Sistematização da Experiência na Formação de Professores de Ciências e Biologia. Revista Práxis Educacional, 16(41), 319-342. https://doi.org/10.22481/praxisedu.v16i41.6313 [ Links ]

Bremm, D. & Güllich, R. (2020b). Sistematização de experiências: conceito e referências para formação de professores de ciências. Rede Amazônica de Educação em Ciências e Matemática, 8(3), 553-573. https://doi.org/10.26571/reamec.v8i3.10788 [ Links ]

Carr, W. & Kemmis, S. (1988). Teoria crítica de la enseñanza: investigación-acción en la formación del profesorado. Barcelona: Martinez Roca. [ Links ]

Cirino, F. O. (2008). Sistematização participativa de cursos de capacitação em solos para professores da educação básica. (Dissertação Mestrado). Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa. [ Links ]

Chaves, S. (2007). Por que Ensinar Ciências para as Novas Gerações? Uma Questão Central para a Formação Docente. Contexto & Educação, 22(77), 11-24. [ Links ]

Dattein, R. (2016). A mediação de Escritas Reflexivas Compartilhadas na Formação em Ciências no Contexto de um Processo de Iniciação à Docência. (Dissertação Mestrado). Universidade Regional do Noroeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Ijuí. [ Links ]

Domingues, G. (2007). Concepções de investigação-ação na formação inicial de professores. (Dissertação Mestrado). Universidade Metodista de Piracicaba, Piracicaba. [ Links ]

Elliott, J. (1998). Recolocando a Pesquisa-ação em seu lugar original e próprio. In C. Geraldi, D. Fiorentini, & E. Pereira (Org.). Cartografias do trabalho docente: professor(a) pesquisador(a). (pp. 137-152). Campinas: Mercado de letras. [ Links ]

Emmel, R. (2019). Currículo e livro didático da educação básica: contribuições para a formação do licenciando em ciências biológicas. Curitiba: Appris. [ Links ]

Falkembach, E. (1991). Sistematização. Ijuí: Editora Unijuí. [ Links ]

Güllich, R. (2013). Investigação-formação-ação em ciências: um caminho para reconstruir a relação entre livro didático, o professor e o ensino. Curitiba: Prismas. [ Links ]

Güllich, R. & Zanon, L. (2020). Investigação-formação-ação: a reflexão crítica como mediadora da formação de professores de ciências [Comunicação oral]. XXIEncontro Nacional de Educação, Ijuí. [ Links ]

Ibiapina, I. (2008). Pesquisa colaborativa: investigação, formação e produção de conhecimentos. Brasília: Líber Livro Editora. [ Links ]

Imbernón, F. (2010). Formação continuada de professores. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Jara, O. (2013). A sistematização de experiências, prática e teoria para outros mundos possíveis. Brasília: Contag. [ Links ]

Kierepka, J. & Güllich, R. (2016). Investigação em Ciências: a transformação da prática em um processo de investigação-ação. In E. Hermel, R. Güllich, & I. Gioveli, (Orgs.). Ciclos de pesquisa: Ciências e Matemática em Investigação. Chapecó: Ed. UFFS. [ Links ]

Kierepka, J. & Gullich, R. (2017). O desencadeamento do diálogo formativo pelo compartilhamento de narrativas em um contexto colaborativo de formação de professores de Ciências e Biologia. Revista Electrónica de Investigación en Educación en Ciencias, 12(1), 55-68. [ Links ]

Lottermann, O. (2012). O currículo integrado na educação de jovens e adultos. (Dissertação Mestrado). Universidade Regional do Noroeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Ijuí. [ Links ]

Marcelo, C. (1992). A formação de professores: centro de atenção e pedra-de-toque. In A. Nóvoa, (Org.). Os professores e a sua formação. 2. ed. Lisboa: Dom Quixote. [ Links ]

Martinic, S. (1998). El objeto de la sistematización y sus relaciones com a evaluation y la investigación. Santiago do Chile: Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó- CEAAL. [ Links ]

Moraes, R. (1991). A educação de professores de ciências: uma investigação da trajetória de profissionalização de bons professores. (Tese Doutorado). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. [ Links ]

Moraes, R. (2003). Uma tempestade de luz: a compreensão possibilitada pela análise textual discursiva. Ciência & Educação, 9(2), 191-211. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-73132003000200004 [ Links ]

Moraes, R. & Galiazzi, M. (2011). Análise Textual Discursiva. 2. ed. Ijuí: Unijuí. [ Links ]

Moraes, R., Ramos, M. & Galiazzi, M. (2004). A epistemologia do aprender no educar pela pesquisa em ciências: alguns pressupostos teóricos. In R. MORAES, & R. MANCUSO, (Org.). Educação em ciências: produção de currículos e formação de professores Ijuí: Ed. Unijuí. pp. 85-108. [ Links ]

Morgan, M. & Monrea, M.(1991). Una propuesta de lineamentos orientadores para la sisntematización de experiencias en trabajo social. In M. Morgan, & M. Monrea, (Org.). Sistematización, propuesta metodológica y dos experiencias: Perú y Colombia. Lima: Celats. [ Links ]

Nóvoa, A. (2009). Professores: Imagens do Futuro Presente. EDUCA, Lisboa. [ Links ]

Passeggui, M., Souza, E. & Vicentini, P. (2011). Entre a vida e a formação: pesquisa (auto)biográfica, docência e profissionalização. Educação em Revista, 27(1), 369-386. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-46982011000100017 [ Links ]

Person, V., Bremm, D. & Güllich, R. (2019). A formação continuada de professores de ciências: elementos constitutivos do processo. Revista Brasileira de Extensão Universitária, 10(3), 141-147. https://doi.org/10.24317/2358-0399.2019v10i3.10840 [ Links ]

Porlán, R. & Martín, J. (2001). El diario del profesor: un recurso para investigación en el aula. Sevilla, Díada. [ Links ]

Radetzke, F., Güllich, R. & Emmel, R. (2020). A constituição docente e as espirais autorreflexivas: investigação-formação-ação em ciências, Vitruvian Cogitationes, 1(1), 65-83. [ Links ]

Reis, P. (2008). As narrativas na formação de professores e na investigação em educação. Nuances, 15(16), 17-34. https://doi.org/10.14572/nuances.v15i16.174 [ Links ]

Rosa, D. (2016). A sistematização dos saberes docentes na formação inicial de professores de química na Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo. (Dissertação Mestrado). Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Espírito Santo. [ Links ]

Rosa, M. & Schnetzler, R. (2003). A investigação-ação na formação continuada de professores de ciências. Ciência e Educação, 9(1), 27-39. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-73132003000100003 [ Links ]

Shulman, L. & Shulman, J. (2016). Como e o que os professores aprendem: uma perspectiva em transformação. Cadernos Cenpec, 6(1), 120-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.18676/cadernoscenpec.v6i1.353 [ Links ]

Suárez, D. (2014). Espacio (auto)biográfico, investigación educativa y formación docente en Argentina: Un mapa imperfecto de un territorio en expansión. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 9(62), 763-786. [ Links ]

Zabalza, M. (2004). Diários de aula: um instrumento de pesquisa e desenvolvimento profissional. Porto Alegre: Artmed . [ Links ]

Zanon, L. (2003). Interações de licenciandos, formadores e professores na elaboração conceitual de prática docente: módulos triádicos na licenciatura de Química. (Tese Doutorado). Universidade Metodista de Piracicaba, Piracicaba. [ Links ]

1This is the designation we use to refer to the participants of this research. They are considered, by us, as teacher-investigators, since we refer to the practice of active participation that is performed by teachers during their training in the meetings of the Formative Cycles in Science Teaching.

Received: October 04, 2021; Accepted: March 03, 2022

texto em

texto em