philosophical inquiry with indigenous children: an attempt to integrate indigenous forms of knowledge in philosophy for/with children

introduction

Philosophy for/with Children (hereafter P4wC) is increasingly becoming well-known as a child-centered educational program that has been appropriated in both formal and informal settings in the different parts of the world. To date, there are about sixty (60) countries where P4wC program is applied, researched and practiced.1 A number of these countries, roughly eleven (11), belong to the Asian continent. The 24th World Congress of Philosophy held in Beijing last 2018 had witnessed the meeting of a number of P4wC scholars and practitioners from various countries and cultures, notably from Asian countries like Iran, China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines. Interestingly, amidst the vibrant exchanges of insights and challenges stemming from different experiences worldwide, one theme that stood out is the ongoing work and initiatives of several scholars in appropriating P4wC in the variegated eastern cultures and traditions. Indeed, a meaningful dialogue between Eastern and the Western philosophies and practices took place. That conference underscored the viability of interfacing oriental epistemologies and knowledge systems with the mainstream P4wC theory and practice.

Notwithstanding the significance of the innovative works of these scholars in localizing the tenets of P4wC in non-western classrooms, it may be argued, however, that little attention has been given to the integration of indigenous forms of knowledge in the theoretical assumptions of the program. Coming from an Asian context with a huge population of indigenous peoples and communities, my assumption is that indigenous ways of thinking is undoubtedly a rich source of wisdom that can substantially contribute, and perhaps improve, in the expanding (and still emerging) theory and practices of P4wC. This is the claim that I hope to substantiate in this article.

I propose the possibility of integrating some epistemological patterns common in indigenous forms of knowledge within the conceptual parameters of P4wC. Such integration is important for at least three (3) reasons: First, recognizing indigenous ways of thinking and seeing the world informs us of other non-dominant forms of knowledge, methods to produce knowledge and criteria to determine knowledge. Second, the dominance of western standards of producing and determining knowledge, especially in non-western societies, needs to be reduced, balanced and informed by local knowledge and experiences. And third, indigenous forms of knowledge reinforce a culturally responsive P4wC practice that responds to the challenges in multicultural and ethnically diverse classrooms.

It must be emphasized that this article is just a preliminary work of a possible prolonged dialogue between indigenous forms of knowledge and P4wC. I acknowledge that whatever I may achieve in this article is a mere scratch on the surface. Thus, this article does not pretend to give a full account of the vast range of indigenous knowledge, or a detailed analysis of its possible connections to both the original (i.e., Lipman-Sharp) and other emerging conceptualizations of P4wC offered by a host of scholars after Lipman.

my context

Between June 2018 and April 2019, I have been facilitating philosophical dialogues with 5th and 6th grade students in two (2) elementary schools in a rural region in the Southern Philippines. I describe these as “schools in the peripheries” not only because of their distant location relative to the nearest city where I live, but also because of the marginalizing conditions the students in these schools continuously experience. Some students come from two (2) indigenous tribes in Mindanao, namely, the Obo Manobo and the Matigsalug communities. These are among the few ethnic groups that compose the local tribes in Mindanao that are increasingly becoming more minoritized and marginalized. Since they live in a remote location, it is not surprising that the conditions surrounding their educational setting do not satisfactorily meet the basic standards required to have a good educational experience. For instance, due to the lack of adequate classrooms, two grade levels, namely grades 5 and 6, are merged in one classroom, leaving the assigned teachers in an almost impossible task in managing their behavior, attention and time. Moreover, they are marginalized insofar as their curriculum does not take cognizance of the particularities of their culture, language, traditions and practices.

I would like to emphasize that in relation to the context of my P4wC experience, I am an outsider. Thus, part of the intent of writing this article is to understand the identity of my students, and by extension, understand my positionality as an educator.

the importance of context in p4wc practice

As P4wC expands to non-western societies, one immediate challenge is how to contextualize both its theory and practice in order to make it relevant, meaningful and useful to both practitioners and students. Despite its western epistemological origins, P4wC has proven to work in other cultural contexts by adjusting some of its “technology” (i.e., instructional materials, texts, language, approach, classroom configuration) and by building on local practices or traditions analogous to it. This process of contextualization entails fine-tuning some of P4wC’s aspects that do not fit the given context and associating it with local practices that could lend a framework to accommodate its aims. After all, any seed originating from a foreign soil needs to adapt to the particularities of a new ground, otherwise it eventually withers, or worse, becomes damaging to the new habitat. Part of contextualization is to design culturally responsive approaches that are sensitive to the differences arising from culture, history, language and ethnicity. One example that has concretely done this is the Philosophy for Children Hawai’i (p4cHi), an innovation from the standard Lipman-Sharp approach, which “evolved in response to the tensions that arose while doing P4wC in a multicultural community context” (MAKAIAU, 2017, p. 99). Through its critical practices, such as establishing intellectually safe communities of inquiry, p4cHi becomes a culturally responsive pedagogy that adapts diverse cultural backgrounds and experiences. Using this approach, Rebecca Odierna astutely reflects on her experiences in molding the program in Kenya. She notes,

My p4c experience in Kenya was first and foremost a learning process. I quickly came to realize that p4c works in different contexts, and that the same approaches I had used in the U.S. were not always viable in Kenya. This is why the term “p4c Kenyan Style” has so much meaning to me. p4c literally had to be molded and adapted to work in the Kenyan context. The fact that p4c was able to adapt to its unique setting conveys the beauty in its remarkable flexibility. It underscores the fact that there is no right or best way to do p4c-its functions and approaches are relevant to the particular community (ODIERNA, 2012, p. 44).

The importance of finding its relevance in the community and background culture cannot be understated. Jessica Chingze-Wang appropriates p4cHi using Mattice’s Metaphor and Metaphilosophy, which she thinks is more “congenial to Chinese cultural sensibilities and philosophical outlooks, and thus holds more promise for grounding p4c in [Taiwan’s] cultural soil” (CHING-SZE WANG, 2015-16, p. 27). She observes that an intellectually safe community of inquiry provides an avenue whereby students get to encounter themselves and others, which “enables [them] to take ownership of their ideas and to exist as unique beings in the world” (Ibid., p. 27). For her, the transformative potential of P4wC is maximized especially when its appropriation takes careful attention to the cultural sensibilities and philosophical assumptions emanating from her country’s unique traditions.

Moreover, P4wC becomes an empowering tool especially when practitioners are deeply aware where the students come from and how their communities influence their understanding of the world and the interpretation of their own experiences. In what Amy Reed-Sandoval describes as “place-based P4C”, crucial in the teachers’ role is the capacity to be discerning of the ways whereby the broader cultural dimensions influence the learning experience in the community of inquiry (REED-SANDOVAL, 2014, p. 9). She asserts that the “sociopolitical and philosophical context can impact the sorts of questions and discussions generated by children” (Ibid.). Students, most particularly indigenous children who have been subjected to various forms of discrimination, become empowered to bring into the philosophical dialogue their own experiences of marginalization especially when their unique contexts are acknowledged and respected. In her cross-cultural P4wC experiences in an Oaxacan community, she recalls that there is

[…] a great interest in talking about Oaxacan indigenous philosophies. We have had lengthy philosophical discussions about the aesthetics of Oaxacan indigenous handicrafts, the intricate significance of Triqui and Zapotec words that cannot easily be translated into Spanish, and the philosophical underpinnings of traditional Oaxacan poems, phrases, and songs that students share in class (REED-SANDOVAL, 2014, p. 10).

The above passage goes to show how P4wC, especially through the COI, can make room for indigenous forms of knowledge as points of departure for a philosophical dialogue. However, it makes me wonder if it was possible to treat them not only as “topics” or “points of entry” for a philosophical dialogue but as presuppositions of the philosophical activity itself. What if these indigenous philosophies, which Reed-Sandoval mentioned, constitute (not totally but at least partly) the very notion of “Philosophy” in P4wC?

The available literature of P4wC has plenty of examples in which its main tenets have been appropriated and localized in cultures outside the United States. However, I would like to note that in almost all of these cases, western philosophy, albeit implicitly, still remains the main point of reference and the source of much of its assumptions. What this obviously means is that, the understanding of “Philosophy” in the “Philosophy for/with Children” is still framed within western philosophical models and perspectives. While there is nothing wrong with this insofar as Philosophy (φιλοσοφία) emanated from a western culture, particularly the Greeks, there is a lacuna in the existing P4wC literature, in which indigenous forms of knowledge are integrated in the key assumptions of the program, either to reinforce its claims, expand or challenge them.

The argument here is that from localizing P4wC, the next logical step should be the integration of some relevant indigenous forms of knowledge within P4wC itself. But how can this integration be carried out? And what does this integration generally mean to P4wC? The subsequent sections will attempt to address these questions.

an important caution

There are at least four (4) “traps” that we need to be aware of in this attempt to integrate indigenous forms of knowledge in the conceptualization of P4wC. First, it is necessary to be wary of the inclination to treat indigenous philosophy as a homogenous subject. As Semali and Kincheloe assert, it is important to avoid the “essentialistic tendency to lump together all indigenous cultures as one” (SEMALI & KINCHELOE, 1999, p. 16). There are thousands of diverse indigenous communities all over the world which are characterized by their distinct belief systems and traditions. Accordingly, the richness of cultural diversity is always presupposed whenever “indigenous forms of knowledge” is mentioned in this article. Second, attempts to appropriate or relate indigenous knowledge within contexts that are not organically part of its background may result to an uncritical dislocation, a de-contextualization of an otherwise holistic knowledge systems. In this attempt of integration, one presupposition we acknowledge is epistemological contingency, which avoids the tendency to universalize, de-historicize or put forward claims that are grounded on a transcultural objectivity. Third, when talking of indigenous cultures and knowledge, there is a tendency to romanticize them as if they belong to a “pure precolonial cosmos” (Ibid., p. 22). We avoid this by acknowledging that all cultures, not exempting indigenous ones, are dynamic and constantly changing. Thus, the epistemological patterns of indigenous knowledge that will be discussed below are not understood as cultural artefacts or fixed theoretical positions. Lastly, the tendency to use indigenous forms of knowledge merely as complementary, or as “add-ons that provide diversity and ‘spice’ to western academic institutions”, should be critically avoided (Ibid., p. 37). To deny attention and recognition of the equally substantial knowledge of the indigenous peoples alongside other prominent forms of knowledge, and to treat them simply as nothing more than folklores and songs, only perpetuate a form of cultural colonialism.2 It is but proper for a true lover of wisdom to recognize, or at least respect, the truths of indigenous wisdom in order to enrich philosophical thinking across cultures and spaces.

common epistemological patterns in indigenous knowledges

When speaking of indigenous forms of knowledge, it must be noted that we are referring to knowledge systems of a vast number of communities, across an extensive geographical space, consisting of millions of peoples with different languages, historical experiences and beliefs. In 2018, there are about 370 million indigenous peoples in 90 countries representing 5,000 different cultures. They make up less than 5 per cent of the world's population.3 Obviously, it is difficult, in fact impossible, to condense such wealth of knowledge and belief systems in just one section of an article. Thus, I cannot avoid engaging in this topic in broad strokes and generalizations.

Generally, indigenous forms of knowledge refer to the unique, traditional, local ideas, beliefs and practices existing within and developed around the specific conditions of women and men indigenous to a particular geographic area (See GRENIER, 1998). Due to the diversity of indigenous cultures and beliefs across the globe, there are no beliefs and traditions that can be said to be embraced by all indigenous peoples. In fact, indigenous knowledge is not a monolithic epistemological concept insofar as indigenous cultural experience is not the same for everybody (SEMALI & KINCHELOE, p. 24). However, there are some epistemological patterns in their ways of thinking, doing and being that may be said to be common to many of them. In this section, we look into some of these patterns of indigenous knowledge that have been found general despite the variety of indigenous cultures.

reality and interconnectedness

One area where different indigenous cultures share a common approach is about the nature of reality. The Hodenosaunee, a member of the group of Native American peoples, has a teaching which states that “we are all a part of the land beneath us, the sky above us, and all that surrounds us” (STYRES, 2011, p. 718). Such belief maintains that every entity in the earth, both animate and inanimate, are all parts of a greater Being, a Reality from which everything emanated. This is a common assumption about the world found in almost all indigenous beliefs. Indigenous peoples do not adhere to a dualistic conception of reality where things and concepts are placed in conceptual categories and hierarchies. This non-dualistic view does not make any unnecessary distinctions between the mind and the body, between the good and bad, or between human beings and the world. Rather, it embraces the complexity immanent in the universe and believes that all beings proceed from the same source. It likewise affirms the intrinsic interconnectedness among all beings, while at the same time celebrating differences and individuality. The seeming oppositions among diverse beings and things are not denied but are balanced and oriented towards harmony. Such worldview, therefore, sees reality in “a spectrum, rather than being made up of absolute wholes” (VAN DER VELDEN, 2018). This kind of epistemology is characterized as a circularity representing “wholeness and interconnectedness that brings all of creation together in a circle of interdependent relationships grounded in land and under the Great Mystery” (STYRES, p. 718). Seen as a creative life force, this Great Mystery4, she adds, “finds expression through land in all of its abstractedness, concrete connection to place, fluidity and interrelatedness” (Ibid.).

What underlies such indigenous view is an epistemological assumption of relationality. In contrast to the notion of “individual” or “private” knowledge, indigenous epistemology presupposes the inherent relationality of knowledge, not only with other thinking individuals, but with the bigger reality including everything in the ecosystem and within the cosmos. Martin notes that “we must recognize that within an indigenous worldview, all ‘things’ have agency and are interconnected through a system of relationality” (MARTIN, 2017, p. 1). Knowledge, therefore, is not only essentially shared, but also possesses a form of (non-human) agency. Further, it is not something that one takes by virtue of some right, but rather something that one receives (See WHITT, 2009).

An implication to this presupposition of relationality is the manner of “acquiring” knowledge. One cannot separate the knower from the object of knowledge, and from the other knowers within the entire knowledge community. It necessitates the lived and grounded ways of obtaining knowledge which carefully take into account the positionality of the knower and its relationship with the bigger community. On this note, indigenous peoples' knowledges, according to Sam and Ktunaxa, are informed by their “processes of witnessing and living within their local context and place, and within their relationship to others” (SAM & KTUNAXA, 2011, p. 317). This method, therefore, avoids an “imaginary relationship” between the knower towards the object of knowledge (MARTIN, p. 4). Both the method and the knowledge-content are intimately linked; thus, epistemology is inseparable from ontology. In what they call “Indigegogy”, Hill and Wilkinson point that “indigenous knowledge is garnered through examining the relationships within the natural world and the web of connections of which we are inherently a part”, a manner that is at variance with the positivist methods of research and with some western analytic ways of thinking (HILL & WILKINSON, 2014, p. 178).

b. ecology and identity

Being indigenous is essentially about one’s connection to the land.5 The very identity of indigenous peoples are intimately woven into the geographic space where they inhabit. This means that their culture, distinct ways of thinking, spirituality, and their very reasons for existence have something to do with their view of ecology. The value they place on their lands does not only signify their means for survival, but more importantly the sustainability and preservation of their identities, communities and the future generations. This is why their “language, culture, stories, epistemology, as well as their relationships to each other and to land are profoundly and intimately connected” (STYRES, p. 719).

Macli-ing Dulag, an indigenous leader in the Province of Cordillera6 who was murdered because of his resistance against the government’s plan to build a dam in his region, gives us an idea of how indigenous peoples understand their relationship with the land. He makes this point directly:

You ask if we own the land and mock us saying, “Where is your title?” When we ask the meaning of your words you answer with taunting arrogance, “Where are the documents to prove that you own the land?” Titles? Documents? Proof of ownership? Such arrogance to speak of owning the land when we instead are owned by it. How can you own that which will outlive you? Only the race owns the land because the race lives forever (DOYO, 2015).

Western notions of property and ownership proceed from the assumption that human rationality and agency have primacy over the earth. In this perspective, humans conquer, possess and dominate lands, not the other way around. The indigenous ecological thinking, on the other hand, preserves the primacy of the land insofar as it determines and sustains their very identities. Humans only inhabit the earth - this Mother Earth that has lived millions of years longer than the first human beings who ever walked on it. Pierotti notes that in contrast to the Western way of seeing the world, indigenous peoples tend to “view themselves not as dominant over, but as connected to and part of, the natural world” (PIEROTTI, 2011, p. 1). Accordingly, the assumption that humans are essentially part of the world, not above it, precludes any claim of domination over nature on the basis of human rationality, agency and power. Human identity, in this sense, is one that emanates from one’s connection with the proximate community and the world in general.

As to how these epistemological patterns of indigenous forms of knowledge be integrated into the conceptual foundations of P4wC, there are several intersections where a possible integration may be considered. I will turn to this topic in the following section.

an attempt to integrate indigenous forms of knowledge in p4wc

What does this integration mean? This integration hopes to open a dialogue between indigenous forms of knowledge and the underlying assumptions in P4wC theory and practice. My claim here is that it is possible to treat indigenous knowledge, particularly their epistemological patterns, not only as topics for philosophical dialogue with children but as presuppositions of the philosophical activity itself. In other words, it asks whether it is viable to welcome indigenous perspectives as constitutive elements to the conceptual foundations of P4wC. My intent is nothing more than to contribute to possibly enriching the theoretical bases of the program and refining its practice, particularly in the context where I am situated.

There are two (2) possible intersections where such integration may take place. These are in the areas of: a) Epistemology and, b) Pedagogy. The first area addresses the question: what counts as knowledge, and how is knowledge produced? The second area, which also offers a concrete example of this integration, addresses the question: how is knowledge learned and taught?

what counts as knowledge in p4wc?

For the purpose of this article, I limit my scope only within Lipman’s works within which, I think, an integration of indigenous knowledge with P4wC theory could be established. P4wC proceeds from the fundamental assumption that children are naturally curious. Lipman observes that “at every moment of a child’s life, events impinge upon that child that are perplexing or enigmatic” (LIPMAN, SHARP & OSCANYAN, 1980, p. 31). Such natural propensity of children to wonder, ask questions and grapple with abstract ideas underscores their being “newcomers” to the world. It is presupposed that when children asks questions, not only do they solicit literal or symbolic meanings, they are most likely asking philosophical questions, which may fall under the domains of metaphysics, logic or ethics. These questions are actually invitations to engage with children philosophically. P4wC as an educative program rests precisely on the assumption that a proper way of introducing and teaching Philosophy to children generates and improves philosophical thinking.

What does this philosophical thinking consist of? Lipman explains that it involves “appreciation of ideas, logical arguments, and conceptual systems” and also “a manifest facility in manipulating philosophical concepts” (Ibid., p. 41). Children’s natural ability to work with ideas, a competency that is unfortunately absent in the tradition style of education, is what is addressed, acknowledged and developed in philosophical dialogues. With the intent to help children learn how to think for themselves, P4wC aspires to enable children to

[…] work out one’s own beliefs and discover good reasons for their justification; to figure out what follows from one’s own assumptions; to hammer out in one’s mind one’s own perspective on the world; and to be clear about one’s own values, one’s own distinctive ways of interpreting one’s experience (Ibid., p. 42).

Through the method of Community of Inquiry, children are treated as seekers of knowledge who engage in collaborative deliberation on particular questions, issues or any topic that touches their interests. They reason together in the hope of finding answers - no matter how tentative - not as individual but as a community. Lipman claims that this process is “not an attempt to substitute reasoning for science, but an effort to complement scientific inquiry” (LIPMAN, 2003, p. 111). Thus, the reasoning that takes place in the COI makes use of logical inferences to extend knowledge, applies reasons and arguments to defend knowledge, and employs critical analysis to coordinate knowledge (Ibid.). It is rather clear that the criteria utilized to determine what counts as knowledge proceeds from the presuppositions of analytic-logical philosophical tradition - or at least a “slice” of it - and from the assumptions of scientific inquiry (KOHAN & KENNEDY, 2017, p. 500).7

I acknowledge that the above claims have spurred debates in the field, which have been tackled at length by several P4wC scholars. Theoretical issues such as these have been addressed by the recent literature on the field and to mention all of them here is beyond the scope of this article.8

Given the above points, it may be assumed that the understanding of knowledge in P4wC - in so far as Lipman is concerned - is largely determined by the quality of reasoning and analysis that is devoted to it in the thinking process. Thus, any proposition that lacks logical coherence, sound reasoning and multidimensional thinking has to be subjected to further questioning and dialogical inquiry, albeit through the help of the other members in the COI. In this sense, it may not be far-fetched to suppose that, for Lipman, among the philosophical traditions that P4wC adheres to, one is a form of representational epistemology - an idea that maintains that truth is obtained through a reasoned representation of the world. Knowledge then is about the world, which can be represented by thoughts and ideas. Accordingly, this search for truth is executed and achieved through discursive reasoning and rational construction of ideas. It follows that thinking and inquiry skills, such as those described by Lipman, and the dialogical process that takes place in the COI are indispensable in this pursuit. If we were to accept the claim that part of P4wC’s assumptions is bent towards the analytic-representational tradition, it may be argued that indigenous forms of knowledge may be integrated through its adherence to a “presentational epistemology”. In this sense, the integration of indigenous forms of knowledge within P4wC theory provides a “counter-weight” to Lipman’s adherence to representational logic.

indigenous epistemology in p4wc

Indigenous forms of knowledge of the world is essentially presentational (See WHITT, p. 37-38). This means that the conditions for the possibility of indigenous knowledge rest on the presence of the natural world and on the rich and varied experiences it offers. According to Whitt “knowledge is located in the world as much as it is located in a people or a person; it is part of what relates the human and nonhuman” (Ibid., p. 55). In representational knowing, when knowledge is “grasped”, it is understood that something happened in the subject’s consciousness, that is, the knower experiences something that involves his being conscious of the object. In a presentational knowing, on the other hand, the knower does not “grasp” a phenomenon. Rather, she is grasped by it. Nature, phenomenon or the world go beyond the rational restrictions set by the knower. In other words, it transcends the constructed, constituted object. Thus, presentational knowing allows nature to manifest itself according to its own conditions of possibility.

Integrating indigenous epistemology in P4wC means foregrounding relationality between the knower and nature or the world, and within her immediate community of inquiry. It assumes that knowledge carries the fingerprints of a communally, culturally and historically situated knower. Knowledge, in this sense, is essentially linked and, in fact, inextricably bound up with the identities and interconnectedness of the children and educators involved in the process. Consequently, integrating presentational epistemology in P4wC entails incorporating relationality and situatedness as criteria for philosophizing within the COI.

This integration also means that meaning-making in P4wC proceeds not only discursively, but also intuitively through one’s direct experiences of the actual presence of nature and culture. This presentational knowing positions the child within the world, rather than outside of it, and avoids the objectivist tendency to look at it from a decontextualized space. Thus, in the act of knowing, the child discovers that agency does not solely proceed from her or tied to her, but shared to her and the community. Attributing agency to knowledge changes the positivist assumption of the world as an inert repository of knowledge that is discovered and conquered intellectually.

An intuitive presentational knowing is characterized by the mental move of representing wholes, instead of parts. It aims at seeing things from a “bigger picture”, and situating things or concepts as always emerging from a context. In a COI, for instance, indigenous ways of thinking manifest through a collaborative effort to see reality along a spectrum rather than in conceptual hierarchies or categories. Rather than breaking a concept into its atomic parts, thinking is directed towards gathering seemingly disparate ideas and orienting them towards a possible balance and harmony. Accordingly, the wholeness of reality and the interdependent relationships between things and ideas are always presupposed in the philosophical dialogue.

Moreover, in the Lipman-Sharp approach, making hypotheses is a discursive tool that expands and tests the limits of a claim or proposition (LIPMAN, 2003, p. 122). However, in integrating presentational epistemology in P4wC practice, the teacher avoids the tendency to lead the philosophical dialogue towards the positing of imaginary relationships between the children and the chosen topic, either by speculating hypothetical scenarios or by teasing them with imaginary dilemmas. Rather, children should be prompted to look inward and examine their own relationships with the idea or thing (no matter how scarce) and locate themselves in the web of conceptual or ontological connections of which they are inherently a part.

Ultimately, integrating indigenous forms of knowledge in P4wC involves receptiveness to other epistemologies, not only representational or presentational, but to alternative ways of knowing the world. It avoids any form of reductive scientism, or the conviction that science is the only possible way of knowing, to permeate in the philosophical dialogues. What is salient here is the idea that such integration embraces a non-anthropocentric epistemological pluralism that affirms the rich and diverse forms of knowledge which are not exclusive only to human beings, but also to non-humans.

How do these abovementioned conceptualizations arising from an integration of indigenous epistemology in P4wC manifest in the practice of doing philosophical work with children? I will attempt to describe this in the next section.

indigenous p4wc pedagogy

It may be well to remind the reader that the intention to integrate indigenous epistemology in P4wC is addressed primarily to researchers and practitioners who are working with indigenous children.

On the most basic level, the integration of indigenous forms of knowledge in P4wC entails utilization of all forms of myth, fable, allegory or drama that are relevant to the members of the community. The key idea here is that “philosophical stories” are not limited to those that are considered “standard literature”. Ideally, the stories emanating from their own culture should be preferred. However, the stories from other indigenous communities and cultures are equally important since these provide the members perspectives of the wider community of indigenous peoples in the world. In this kind of COI, the members read and discuss a story, and most importantly acknowledge themselves to be already part of an ongoing story of their culture, community and the world.

Moreover, the interrelatedness of the indigenous view of the land and their identities teaches a relevant insight on P4wC pedagogy and the role of the educator. The indigenous understanding of “land” transcends the actual physical geographical space one lives in as it also signifies the “discourses, ideologies and philosophies embedded in land in the form of ancient knowledges” (STYRES, p. 722). In most indigenous communities, the act of story-telling is a common educative tool. In what she terms “storying”, Styres points to the underlying importance and implications of stories in the educative process. She explains,

Storying is a discovery and creation of self in relationship; it is a process embedded in an examination of past experiences in relation to present and future actions. If in fact we teach what we know in relation to who we are, then it follows that we must know our stories. In order to know our stories we must highlight the role of ongoing and reflexive inquiry into self and context in relation to land…Teaching is a storied act. To teach is to develop a living text (STYRES, p. 719).

Interestingly, the COI shares many assumptions with this storytelling method. Its circular configuration symbolically affirms the relationality of knowledge, knowers and the world who are all connected within the circle or the community. Meaning-making, therefore, is a process that develops only within and among fellow seekers and inquirers. One cannot expect to obtain meaning, much less the truth, in isolation.

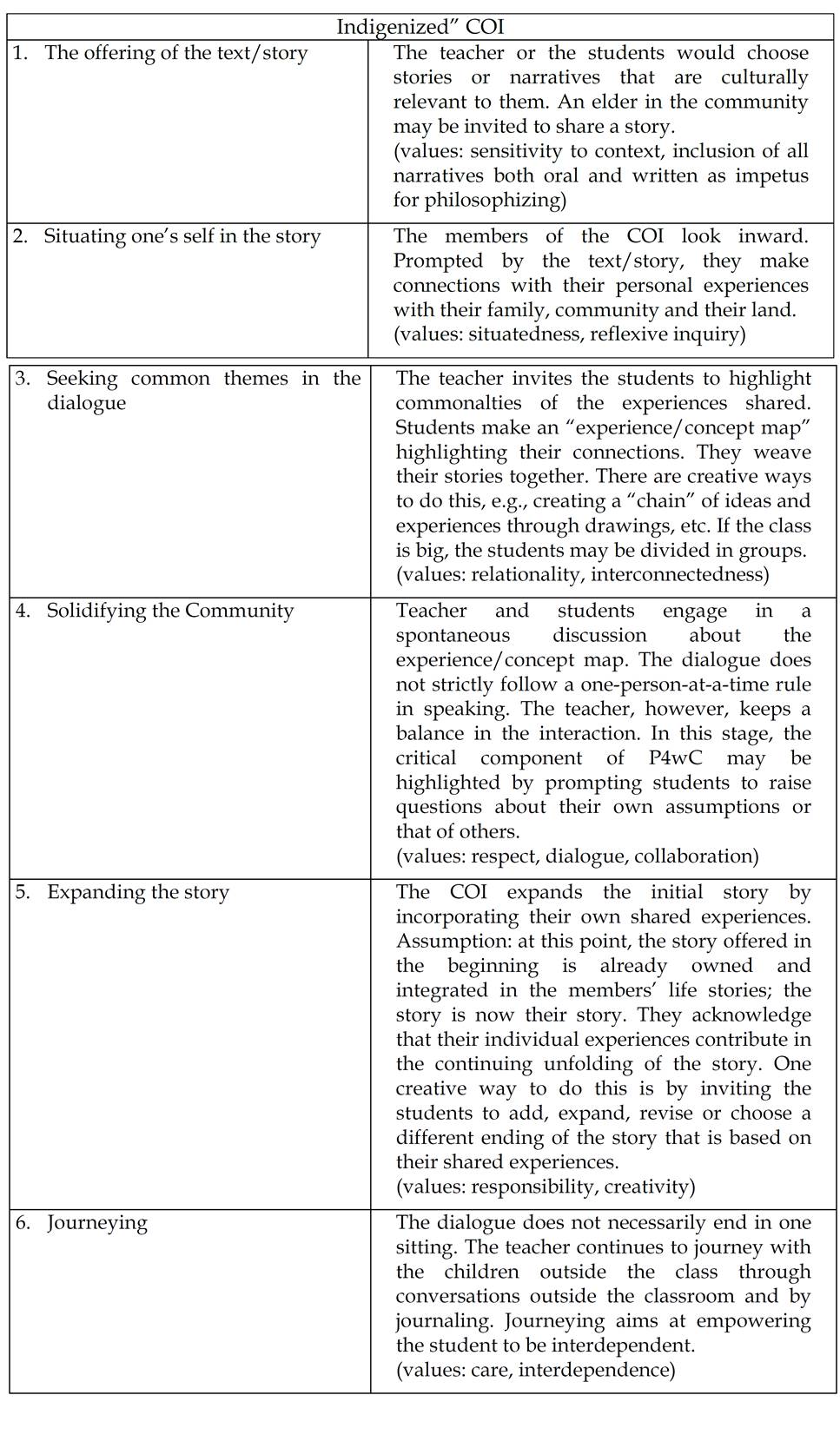

Below is a rough outline of the COI that integrates some indigenous ways of thinking and relating with others. One can observe that the “indigenized COI” is not so different from the standard flow of COI, except during the “construction of the agenda” in which students (in the standard COI) are invited to raise questions prompted by the text. What is unique in this indigenized flow is the lesser emphasis placed on the act of questioning and the setting up of a learning agenda. While questioning and other thinking skills are welcome in the process, these serve only as tools that help achieve the more important values of interconnectedness, situatedness and relationality.

concluding remarks

I have attempted to show that some indigenous epistemological patterns tend to create a conceptual and practical space that allows for a possible integration of indigenous forms of knowledge within the assumptions of P4wC. I acknowledge, however, that this article has only touched the surface of a sustained dialogue between the Western and Eastern philosophical traditions, especially where P4wC and indigenous philosophies overlap. Also, I have tried to show that presentational epistemology, which underlies most indigenous forms of knowledge could provide a counter weight to the analytical bent of P4wC, especially as originally conceived by Lipman. The deployment of presentational epistemology, however, does not cancel out the importance of discursive reasoning and the development of thinking skills. Rather, it proposes a different way of thinking and seeing the world, one that cannot be simply brushed aside as non-objective or non-philosophical. Lastly, I would like to emphasize that the article recognizes its epistemological contingency within local indigenous cultures, and thus avoids the tendency to universalize its claims.