introduction

This agenda-setting paper aims to encourage scholars in the Philosophy for Children (P4C) camp to take consensus into account. P4C focuses on the process of deepening children’s understanding of philosophical questions through reason-exchange and reciprocal listening. In this inquiry process, consensus-making is normally regarded as something that should not be established as a primary purpose (CASSIDY, et al., 2018; DUNLOP, 2017). Just as existing democratic education is criticized in the same manner (e.g. LO, 2017; RUITENBURG, 2009), P4C scholars believe that consensus-making would neglect the diversity of students’ perspectives and facilitate exclusion of minority voices.

This paper counteracts such an assumption. It argues that anti-consensus assumptions stand upon a narrow conceptualization of consensus, or, more specifically, a “universal” account of consensus. While this paper agrees that universal consensus-making is not a primary purpose of P4C, it contends that the authentic process of philosophical inquiry demands non-universal consensus-making moments. The community of philosophical inquiry is grounded in what Golding (2009) calls “philosophical progress,” a process of iteration between problem-solving and problem identification. Importantly, philosophical progress requires children to achieve a non-universal consensus (e.g., consensus on the reasonableness of the suggested solution, consensus on dissensus); otherwise, inquiry ends in merely conversation or antagonistic disputes (GARDNER, 1996; TSUCHIYA, 2018). Put differently, given that philosophical progress is the core of the authentic community of philosophical inquiry, consensus-making should also be taken into account as a core part of P4C.

To rethink the role of consensus-making in P4C, this paper focuses on what Simon Niemeyer and John Dryzek (2007) call meta-consensus. The core idea of meta-consensus is that even people who disagree with each other can nonetheless achieve a consensus on the degree to which they can accept opponents’ perspectives. For example, even if people have a conflicting normative view about a philosophical question (e.g. pro-life versus pro-choice), collaborative inquiry can allow them to make consensus on the value of the other side’s opinion and thereby to listen together. As such, the idea of meta-consensus offers insight into the way in which non-universal forms of consensus-making allow people in conflict to collaborate by engaging in a constructive dialogue. On the basis of the idea of meta-consensus, this paper makes a case for how meta-consensus can function as an enabler of philosophical progress in the community of philosophical inquiry by drawing on the findings of a case from Japan.

This paper is divided into four parts. The first section outlines how P4C and consensus-making are seen as strange bedfellows. The second section focuses on Golding’s idea of “philosophical progress” as a core element of philosophical inquiry and then argues that philosophical progress entails non-universal consensus-making moments. The third section introduces the idea of “meta-consensus” in order to reconsider the meaning of consensus in P4C. To understand how meta-consensus occurs in P4C, the fourth section draws on the case of a philosophical inquiry conducted with Japanese students.

philosophy for children as democratic education and consensus-making

Philosophy for Children (P4C) was initially pioneered by Matthew Lipman in the 1970s (see LIPMAN, 2003) as an educational practice for critical thinking. To date, P4C is introduced in many classrooms and schools as a form of democratic education, or what Makaiau (2016) calls “deliberative pedagogy.” P4C is expected to cultivate students’ democratic communication capacities, especially reason-exchange, justification of one’s position, listening, reflective thinking, and creation of a moral community (see also BURGH et al., 2006; ŠIMENC, 2009). P4C is also expected to facilitate students’ mutual understanding across difference (MAKAIAU, 2016). As Burgh (2014) rightly points out, P4C is not just education for future democracy but is itself democracy in practice.

In recent years, democratic education scholars have engaged in great controversy over the relationship between democratic education and consensus-making. According to the literature, existing democratic education tends to focus too much on “rational” deliberation that attempts to reach “harmonious” and “universal” consequences, such as consensus-making, and ignores the pluralistic as well as conflictual conditions of human existence. Drawing on Mouffe and Rancière’s argument against consensus in deliberative democracy, Ruitenburg argues:

[…] the currently dominant framework of deliberative democracy does not sufficiently recognise the constitutive nature of disagreement. The deliberative conception of democracy and democratic citizenship emphasizes rational deliberation leading to political consensus. For Mouffe and Rancière, however, consensus means erasing the contestatory, conflictual nature of the very givens of common life. (RUITENBURG, 2010, p. 44)

Echoing Ruitenburg’s arguments, democratic education scholars have problematized the meaning of consensus-making in democratic education and, instead, contended a need for a shift “from harmony to agonism” (TODD, 2010), “from universal to plural” (LO, 2017), or “from consensus to dissensus” (BIESTA, 2011).

Similar arguments are also found in the P4C community, as P4C is one form of democratic education. Scholars in P4C, in their criticism of consensus, ground their rationale in agonistic thought, arguing that consensus may neglect differences between students and prevents free inquiry. Consensus is usually described as an opposite of P4C’s ideal or something that is not a primary goal, as exemplified by the following two excerpts: “It [P4C] prioritises their [students’] thinking, and it is recognised that the community many not reach a consensus view.” (DUNLOP, 2017, p. 76)

[…] there is no search for consensus or a conclusion. It is these features, amongst others, that suggest CoPI [Community of Philosophical Inquiry] might be an appropriate practice in supporting the participation of children with emotional-behavioural and/or communication needs. (CASSIDY et al., 2018, p. 5)

As such, P4C scholars tend to pay limited attention to consensus-making processes. Consensus is regarded as a “bad” outcome of philosophical inquiry, as it potentially oppresses minority views and instead facilitates domination.

philosophical progress without consensus?

While P4C scholars tend to situate consensus as opposed to philosophical inquiry, this article problematizes such a view. More specifically, this article asks: is the community of inquiry possible without consensus? This question should be taken into consideration seriously, because the community of inquiry is anchored in what Golding calls philosophical progress, which inevitably entails a consensus-making moment, albeit not a “universal” one.

Philosophical progress is a widely shared view in the P4C community, the core claim of which is that inquiry becomes philosophical if it opens up a new intellectual navigation. The underlying presupposition here is that the community of philosophical inquiry is different from conversation. This view is shared by many P4C scholars. According to Gardner, for example, a conversational, not philosophical, inquiry would be a “boring” activity. She argues:

If students believe that they can say whatever comes into their heads without having to show how this is important or relevant with respect to the topic under discussion, without having to engage in conceptual analysis, without having to back their claims with reasons, without having to worry about being consistent, they may tend to say whatever comes into their heads. (GARDNER, 1996, p. 106)

By Gardner’s account, conversation and philosophical inquiry are different activities because, while the former encourages students to say whatever comes into their minds, the latter values the process by which students make an effort to deepen their understanding of the philosophical question through conceptual analysis, reflective reason-exchange, and listening. This inquiry process provides students with various intellectual avenue through which they can clarify new aspect of the problem, recognize counterclaims, and develop their ideas. As a result, students can get clearer conceptual as well as philosophical understanding of the question. Golding (2009, p. 245) conceptualizes this process where students update their perspectives on the philosophical question as “philosophical progress.” He argues that the core of philosophical progress in the community of philosophical inquiry is the iteration between problem solving and problem identification. More specifically:

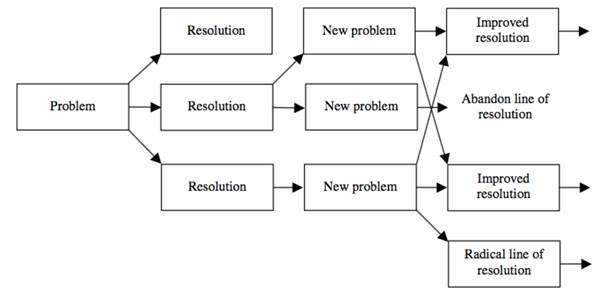

We make progress through successive iterations of resolving problems, where every resolution becomes the source of a new problem to be resolved. The original problem arises as an incongruous, inadequate conception and we develop a more congruous and adequate conception to resolve this problem. However, more advanced problems arise, which might be previously unnoticed problems, more subtle variations of previous problems, or even new information that shows the resolution to be problematic. In response we might develop yet more congruous and adequate versions of the resolution. Alternatively, we might abandon a line of resolution that we judge to be fundamentally in error, or develop radical resolutions that were not previously available. (GOLDING, 2009, p. 245).

Through such interactions between problem-solving and problem-identification, students analyze and develop problems and concepts. Even if they reach one resolution, this resolution should be examined from different angles, which would help students identify new problems and conceptual findings. Figure 1 below, suggested by Golding, illustrates what philosophical progress looks like.

Golding’s argument on philosophical progress is important for rethinking the role of consensus in P4C, because his argument implies that students need to achieve a specific consensus at each stage of dialogue to move the dialogue forward. The term “consensus” here does not imply a harmony-oriented activity that unites different opinions and perspectives into a unanimous agreement. Nor is it a practice that seeks universal solutions or definitions of philosophical problems. The term “consensus” here means, for example:

Participants recognize the multilayered and complex character of the issue in question.

Participants agree on whether the question is solvable or worth solving.

Participants agree on how they recognize and interpret the question.

Participants agree on whether to abandon the suggested resolution.

Participants recognize whether the new solution is important or not.

Without these consensuses, it would be almost impossible for students to go to the next stage of the inquiry.

The implications of this argument are twofold. First, consensus-making is one of the essential parts of the philosophical progress. Without achieving consensus in a process of dialogue, the value of the suggested solutions, and a recognition of various solutions, philosophical inquiry may end in merely conversation or antagonistic dispute. Secondly, even if consensus-making is important for philosophical progress, the meaning of consensus should not be understood narrowly. Consensus practiced in philosophical inquiry is something that is different from a harmonious, universal, and exclusive activity that is criticized by agonistic democracy scholars. So, what kind of consensus is it?

from universal consensus to meta-consensus

In responding to this question, this paper suggests that the idea of “meta-consensus” originally suggested by Niemeyer and Dryzek (2007) would offer valuable insights. Focusing on meta-consensus would be a good starting point because this idea provides a model of non-universal consensus and allows us to understand how norms of P4C (e.g. inclusiveness, diversity) and consensus-making are compatible. Put differently, the idea of meta-consensus would help us rethink how consensus-making and philosophical progress happen without neglecting inclusiveness and diversity of views.

The idea of meta-consensus emerged from deliberative democracy studies. Inspired by Rawls (1996) and Harbermas (1984), early deliberative democrats argued that one of the key aims of deliberation is to achieve a consensus through rational, authentic, and reciprocal communication among citizens (see COHEN, 1998). For example, Niemeyer and Dryzek (2007, p. 503) classify three types of consensus that often happen during deliberation: normative consensus, epistemic consensus, and preference consensus.

Normative consensus is an agreement on the values that should predominate deliberation. For example, Niemeyer and Dryzek draw on the case of public deliberation about the road-building in Bloomfield, Australia, and show three different types of normative view (the needs of the community are most important; the needs of the environment are most important; both are equally important). When people make an agreement about these normative views, we can say that a normative consensus has been achieved.

Epistemic consensus refers to an agreement on people’s beliefs regarding the impact of the consequences of deliberation. In the road-building case, there are also three conflicting epistemic views (the road will benefit the community; the road will negatively impact the environment; the road will benefit the environment). If participants reconcile these views, we can say there is an epistemic consensus.

Preference consensus is about “the degree of agreement about what should be done” (NIEMEYER & DRYZEK, 2007, p. 505). In the road-building case, there are two possible consequences (keep the road; close the road). When participants rank their expressed preference and there is an agreement on what is the most agreeable consequence (or most non-agreeable consequence), we can say a preference consensus is made.

Niemeyer and Dryzek acknowledge that it is hard to realize these three forms of consensus, especially when the topic is highly contested, or deliberation is conducted in a deeply divided society. Nevertheless, they argue that, even though people fail to make these consensuses, a well-functioning deliberation can help them make consensus at a meta level, which is what we call meta-consensus (2007, pp. 503-506).

In normative meta-consensus, participants do not need to have normative uniformity at the substantive level; instead, they can agree that opponents have legitimate normative values about the issue in question. In the case of road-building, for example, participants disagree with each other as they privilege the value of community over environment and vice versa. Yet they can achieve normative meta-consensus when they understand that the others have legitimate values that are worth considering.

In epistemic meta-consensus, participants are not required to agree on one another’s beliefs about the impact of the consequences of deliberation. Yet they can achieve meta-consensus when they agree on the credibility of such beliefs. Even if the other side has “irrelevant” beliefs, participants can acknowledge that the beliefs are reasonable to hold. When the issue is highly complex, people sometimes have “wrong” beliefs grounded in misinformation or biased information. But by facilitating participants’ mutual listening and communication, deliberation enables participants to have an opportunity to express why and how they believe what they do about the issue and thereby to understand why the others have their own beliefs. This belief-sharing experience can provide a first step toward accommodating different perspectives and allowing participants to collaborate together.

In preference meta-consensus, participants do not need to reach a universal agreement on the possible consequence and decision, but instead to agree on the degree to which they accept alternatives. In the road-building case, for example, participants are divided into “close the road” and “road construction.” But if they share the view that the degree of access is the most important dimension of the issue, they may agree on alternative preferences (e.g., the road will be constructed but used only for four-wheel cars) or make an effort to find a point of agreement.

These three forms of meta-consensus offer insight into the way in which we understand the relationship between philosophical progress and consensus-making. This is because these three forms of meta-consensus enable us to explain how different students contribute to progress inquiry philosophically by recognizing the value of different (or sometimes opposing) views, examining different solutions to philosophical problems, and making decisions about whether the suggested solution is worthy of investigation.

For example, in an authentic community of philosophical inquiry, students may disagree with each other about their normative values (e.g., utilitarian values versus deontological values), yet in order to advance their inquiry, they have to recognize that the other side has a legitimate normative value (normative meta-consensus). Otherwise, their inquiry ends in merely a quarrel with no reciprocal listening. In addition, when a student proposes possible solutions, the other students need to provide that student with an opportunity to explain why the solution is worth considering, so that everyone can share underlying experiences, knowledge, and/or assumptions of the expressed belief (epistemic meta-consensus). Without epistemic meta-consensus, they may lose an opportunity to examine whether the expressed belief is reasonable and credible. Also, if resolutions have been suggested in order to move the inquiry forward, they need to examine the degree to which the suggested resolution is acceptable (preference meta-consensus). Otherwise, it would be hard for them to consider a new philosophical problem, abandon the resolution, or develop a radical line of resolution. In a nutshell, students’ efforts to achieve normative, epistemic, and preference meta-consensus would help philosophical progress.

In addition to these three forms of (meta-)consensus in philosophical inquiry, this paper also suggests that there is (meta-)consensus on communication norms, which is a key to realizing what Lipman (2003) calls the “self-correction” capacity of philosophical inquiry. As indicated in the previous section, philosophical inquiry is anchored by normative views on rational communication, such as active listening, reason-exchange without interruption, reflective and critical thinking, respecting different views, and so forth (see LIPMAN, 2003, pp. 95-100). In the real world, however, it would be rare for students to engage in all of these ideal communications in one practice. Instead, as Golding (2013, p. 15) indicates, in a successful philosophical inquiry, students make an agreement about whether the inquiry is practiced in a relevant manner, asking and checking whether they engage in good communication and what sort of communication they have to engage in to move their inquiry forward. In other words, even if not all students achieve a universal consensus on normative communicative behavior during an inquiry (e.g., some students may behave in a disruptive manner), they can achieve meta-consensus on communication norms by modifying irrelevant communications.

meta-consensus in the community of philosophical inquiry

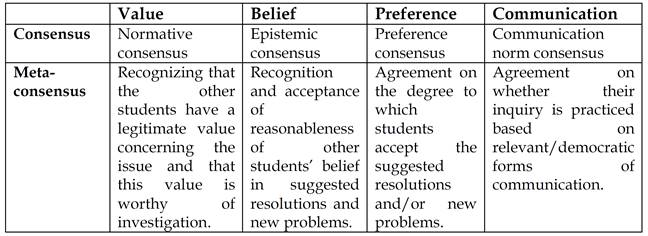

So far, we have seen four types of meta-consensus that can be practiced in an authentic community of philosophical inquiry. Table 1 below is a visual summary of the above argument (see also NIEMEYER & DRYZEK, 2007).

We now turn to look at one example of a community of philosophical inquiry practiced with Japanese students (aged 13-14). The data was gained on 11 November 2016 from a P4C classroom in one private school in Saitama prefecture, Japan. The author conducted ethnographical fieldwork between September to December in 2016, which included participatory observation (N = 39), in-depth interviews with teachers and students (N = 19), and action research (see also NISHIYAMA, 2018). The data is analyzed through a “qualitative thematic analysis”-a systematic classification of the data based on the coding-based on the four coding themes: normative (meta)consensus, epistemic (meta)consensus, preference (meta)consensus, and communication norm (meta)consensus.

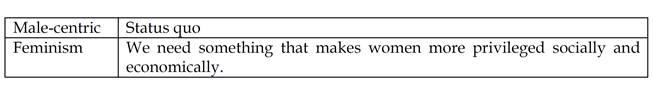

The topic of inquiry was “gender inequality in Japan.” The main question was “Are Japanese women less privileged than men?” During the dialogue, students analyzed the concept of “gender,” “inequality,” and “power” in order to deepen their understanding of gender inequality. This paper draws on this case because it shows that while the inquiry was seemingly just a quarrel, in which students were divided into “male-centric” and “feminism” groups and there seemed no room for philosophical progress, they made an effort to achieve meta-consensus at the normative, epistemic, and communication norm levels, thereby making philosophical progress possible, although they failed to achieve preference (meta)consensus.

normative (meta-)consensus

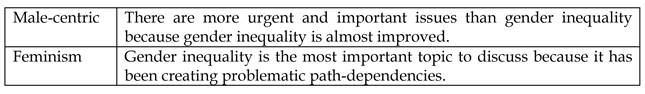

In the inquiry, students had two opposite normative views on gender inequality in Japan. On the one hand, a group of female students problematized gender inequality as one of the crucial problems in Japanese society. On the other hand, a group of male students argued that gender inequality is not an urgent issue that ought to be resolved immediately, because they thought that gender inequality is almost resolved. For example, one male student indicated that “in Japanese politics, more and more female politicians are elected, such as Yuriko Koike, the first female governor of Tokyo, and thus I think the current status of women in Japan is dramatically improved” (Student 6, male). Table 2 below summarizes the disputed normative values concerning gender inequality in Japan.

If the two sides remain as far apart as ever, there may be no philosophical progress either. Even if students can engage in a quarrel, they may fail to find a way of developing, sophisticating, and elaborating their understanding of gender inequality.

On the face of it, students were polarized. However, when seen from a different angle, it is possible to say that they made several normative meta-consensuses, despite their disagreement on the normative value. For example, after one male student (Student 15) compared gender inequality in Japan to that in other countries, another male student (Student 6) accepted part of the female students’ claim. He argues,

I still think women already play an active role in Japan. But, as Student 15 said, Japan ranked at 120 among developed countries, according to the UN statistics on gender equality. So, compared with other countries, hmm, yes, I agree that Japan is a male-centric society.

While he argued at the beginning of the inquiry that gender inequality is already improved in Japanese society, he acknowledged that Japan is a male-centric society when he compared Japan with other developed countries, which enabled him to accept part of the female students’ claim as legitimate. Even if students were still divided regarding their normative consensus on gender inequality in Japan, they made normative meta-consensus by sharing the view that gender inequality is a legitimate topic to be explored through inquiry.

epistemic (meta-)consensus

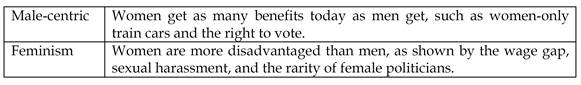

Each group explained their various beliefs about why they thought gender inequality is already resolved (or not). As Table 3 illustrates, the male student pointed out examples of women-only train cars and women’s right to vote, and concluded that women, as well as men, benefit from society. On the other hand, the female students criticized this view, arguing that women are still disadvantaged, as typically found in the example of sexual harassment, the wage gap between men and women, and the small number of female politicians.

The arguments made by both sides are more or less biased or based on misinformation. For example, there is a women-only train car not because society privileges them, but because women face a higher risk of being sexually assaulted than men do. On the other hand, men as well as women are subjected to sexual harassment. This implies that the participants in the inquiry may not be able to move their inquiry forward if they fail to recognize that their belief is grounded in biased information, and they have biased assumptions about gender. So students asked questions in order to clarify whether the expressed belief is grounded in reasonable assumptions and information. For example,

Student 1 (female): In sports, I often feel that audiences tend to focus on men’s games rather than women’s. Student 2 (male): Oh, I don’t think so. Recently the women’s soccer game receives great attention. Student 1 (female): But they are called “women’s” soccer. We usually do not say “men’s” soccer. Women’s soccer receives attention because it is rare and played by women. Student 3 (female): Yeah. True. Men are more advantaged, although this is not visible. Student 10 (male): People pay special attention to women because women are in a relatively low status. Women are still in a weak position.

While Student 2 offered counterexamples to criticize Student 1’s claim, Student 1 gave evidence regarding women’s soccer to justify her position. As a result, other students recognized that Student 1’s belief is acceptable because they believed that it is based on a reasonable assumption. As such, while they disagreed with each other in terms of their epistemic beliefs, they achieved epistemic meta-consensus.

preference (meta-)consensus

In the inquiry, students failed to establish both preference consensus and preference meta-consensus. Students attempted to progress their inquiry by providing several resolutions, yet they disagreed with each other about the degree to which they could accept the resolution. As Table 4 illustrates, students expressed two opposite preferences for how to deal with gender inequality: status quo (the male group) and privileging women (the female group). Although, as we have seen, students achieved normative meta-consensus about the significance of discussing gender inequality in Japan, they persisted in their positions and their opposite views were not reconciled throughout the inquiry.

communication norm (meta-)consensus

Lipman’s normative view (2003) indicates that philosophical inquiry needs to be inclusive and care-based activity in order to enable free and equal inquiry. In the case of Japanese students’ dialogue, students are announced the significance of such inclusiveness and caring, yet in reality they often fail to practice it. For example, during the inquiry, male students talked over 40 times, whereas female students talked only 11 times. Since philosophical progress requires a variety of perspectives, ensuring equal opportunity to voice opinions would be the key normative mission in P4C.

Although students failed to engage in normative forms of dialogue, some male students attempted to check whether their communication was inclusive. For example, when male students dominated the inquiry without providing female students with opportunities to voice their opinions, some male students cautioned their peers in following manner:

Student 3 (male): I think the girls may have something to say. We need to ask them. Student 4 (male): The girls did not speak yet. In addition, when a male student rejected a female student’s belief, several male students cautioned: Students (males): No, you shouldn’t deny it [her opinion]. This is not a debate. We have to do dialogue without rejection.

Although the overall process of dialogue was male-centric, some students attempted to check the inclusiveness of their dialogue and to share what good dialogue ought to be. As such, their effort contributed to enhancing the self-critical, or what Lipman (2003) calls “self-correction,” capacity of community of philosophical inquiry.

conclusion

In this paper, we have seen that the community of philosophical inquiry in P4C and consensus-making are not strange bedfellows. Although P4C does not require a universal account of consensus-making, it requires other forms of consensus-making to make philosophical progress possible. Drawing on the concepts of normative, epistemic, preference and communication norm meta-consensus, this paper demonstrates that meta-consensus-making would be beneficial in facilitating philosophical progress in a different manner, not by uniting different views into a single box, but by respecting such differences.

From a practitioner’s point of view, the idea of meta-consensus offers the insight into how we can assess the quality of philosophical inquiry. Even if students fail to engage in “good” inquiry on the face of it, meta-consensus enables practitioners to interpret the quality of inquiry from meta-angles. For example, in the case of Japan, students fail to achieve normative, epistemic, preference, and communication norm consensuses throughout the inquiry. Quite often, such inquiry is evaluated as “low quality.” Yet, as this paper shows, students achieve normative, epistemic, and communication norm consensus at a meta-level, although they failed to achieve preference meta-consensus because they attached their preference to the given dichotomy (status quo versus change) without listening to the other side. Hence, the idea of meta-consensus tells us not only whether there is philosophical progress, but also what kind of philosophical progress students can achieve (or not).