introduction: open-mindedness, a key concept in philosophy for children

One day, an eight-year-old boy, Alexandru, said to me: "When we do philosophy, we enrich our minds thanks to the ideas of others because we are living in an infinite ocean of philosophy. To cross this ocean, it is better to be with others; it is too hard to do it alone.” 1

Another morning, Mattéa, nine-years-old, declared: “Philosophy is something that helps us to think, to think together in order to acquire new ideas about the world”2

It was by observing that children perceived philosophical discussions as a time for mutual intellectual support and collaborative thinking that I chose to study for my doctoral thesis3 the issue of open-mindedness in philosophical practice. This choice was also motivated by the fact that the concept of open-mindedness is omnipresent. In everyday life, we often prise an openminded person and criticize the absence of that quality. In our civic life, we are constantly confronted with this question: should we be openminded towards every ideological stance? Can a political debate be fruitful if participants never truly consider what their opponents propose? Open-mindedness is a crucial question in political life and citizenship. If we aim to develop political skills that will enable children to be citizen agents, it seems they should be able to convey their points of view and convictions, but without becoming totally impervious to pluralism and diversity. It is one of the most crucial challenges in being a citizen agent: finding the equilibrium between defending political views in which we truly believe in and staying open to alterity and alternative. In the educational field, not only do teachers and educators constantly refer to open-mindedness as a value but they also invite their students to endorse that attitude. In the micro-society of school, it seems to be an essential ethical posture in order to foster ethical relationships between students. But how can children grasp what it means? I believe that open-mindedness cannot be imposed through injunction: it is a way of being that one acquires through experience and exercise. Philosophical workshops could be one of the ways of experiencing it.

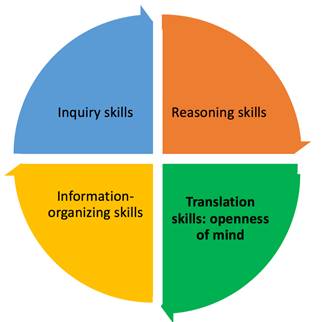

Furthermore, all methods for Philosophy for Children claim that this practice fosters the development of an open mind. Matthew Lipman, the founding father, considered that this is one of the four thinking skills necessary to philosophise (Lipman, 2003: 172-179). Alongside reasoning skills, inquiry skills and information-organizing skills, he defends translation skills: these encompass the ability of listening, of respecting one another, of welcoming, of accepting criticism. As Lipman himself implied, these translation skills all entail, as we will see, a process of open-mindedness. This state of mind is thus paramount for the realisation of the community of philosophical inquiry.

In the French method of “Discussion à Visée Démocratique et Philosophique” (Discussion for Philosophical and Democratic Purposes, Tozzi, 2001, 2002), dialogue is defined as a democratic activity that consists in “encouraging a certain open-mindedness in children, reasoning and common research” (Trovato, 2004: 27). Here, the philosophical discussion is organized in a democratic fashion: equal distribution of speech, assignment of responsibilities (journalist, synthesizer, reformulator, chairman, observer). The finality of this democratic setting is to change the power dynamics between students in order to encourage everyone to create philosophical ideas and to pay attention to all existential hypothesis.

Some even consider that the practice of philosophy with children could develop open-mindedness as a cognitive habit, a way of being or even a human quality. Robert Fisher, for instance, declares that “philosophical inquiry with children can be a way through with qualities such as open-mindedness (…) can be integrated to human character” (Fisher, 2008). Philosophy for children would try to instigate a certain way of being with others.

Despite the omnipresence of this notion, I could not find any analysis or precise descriptions concerning it. What is open-mindedness? Is it a blind acceptation of others? Is it a way of welcoming every idea and person and falling into non-rigorous relativism? Facing this vagueness, I decided to propose the following idea: open-mindedness is a process in which we welcome an idea, a fact or a person, without subduing to it, we extend our thinking towards exteriority in order to encounter it in its wholeness. More precisely, it can be defined firstly by a cognitive sense (as an intellectual disposition favourable to a gradual broadening of thought) and secondly by an ethical sense (as the availability of an individual which fosters an understanding and acceptance of otherness). In the context of both facets, open-mindedness involves a process of intellectual empathy, as was notably defined by Robert Fisher (Fisher, 2008): this is distinctive from emotional empathy because it does not consist in putting yourself in the place of another in order to experience their emotions and gain access to their emotional state, but to enter their mind in order to gain an intellectual understanding of them and think along the same lines. Open-mindedness seems to be a form of intellectual empathy that leads us to experience an ethical posture: the willingness to truly connect to alterity.

Consequently, we reach the following research hypothesis: philosophical for children, as it has been imagined for some forty years, is defined as an intellectual exercise of collective discussion with commits children to a process of open-mindedness. How can a philosophical discussion offer an opportunity to experience and develop this crucial civic attitude: open-mindedness?

1. method: observation of philosophical discussions with children, a context favourable to open-mindedness

1.1 the introduction of a research action: the "philo pour tous” (philo for all) project in romainville, france (93 230).

In order to explore my research hypothesis, I chose to carry out a theoretical and experimental survey and research action4, from 2011 to 2016, based on practice in the field and centred on the organisation of philosophy workshops with children aged from 5 to 14 years in educational establishments in Romainville (Seine Saint-Denis, France): schools, social centers, libraries, cinemas. Every group participates to 20 workshops during the year in order to establish a regular practice, dedicated to the development of cognitive and behavioural habits, to the familiarisation with philosophical concepts and questions and to the understanding of the principals of the community of inquiry. Leading, observing and transcribing these workshops were expected to provide some responses in order to target the phenomenon of open-mindedness, of intellectual empathy. The methodology was simple: to create spaces for reflection where the children, sitting in a circle, could address their philosophical questions during a discussion facilitated by an adult steering the group towards thinking skills (such as conceptualizing, reasoning, organizing information, inquiring and translating), in order to encourage the emergence of ideas, theories and hypothesis. My method aims to build a community of inquiry, in a lipmanian manner, but I don’t specifically use the traditional texts as I chose to stimulate their thoughts using specific pedagogic tools such as children’s books, films, games and drawing. That being said, these media always convey an existential wondering, and the discussion is always built upon a question proposed and voted by the group.

1.2 identification of elements favourable to the development of open-mindedness during philosophical discussions with children

With the aim of ensuring the optimum conditions necessary for the appearance of open-mindedness, we established three methodological conditions which were also specific to philosophical activities and thus a particularly appropriate springboard to demonstrate this phenomenon.

First of all, we felt it was essential to base the discussion on the philosophical questions posed by the children. Indeed, empathy requires the development of a link between the children involved. In this respect, philosophy provides an excellent substrate: the universal issues of human and childhood existence federate the group around a common question through which the children can become aware of the fact that they are all members of a human community that is bigger than all of them. Our experiments showed that some of the questions raised by the children were agreed on by the entire group, who were all nagged by the same worries. “What was there when there was nothing?”5 (Sofiane, 9 years); “Why does everyone want liberty?”6 (Samantha, 8 years); “Why do we like the feeling of love?”7(Sev-Dinh, 8 years); “Are we all really different?”8(Iris, 8 years); “Why do we not have the right to be immortal?”9 (Nihed, 10 years); “Why are wars so terrible?”10 (Waffa, 7 years); “Do we exist because we have a mission?”11 (Pearline, 9 years); “Do animals also have pets?”12 (Soraya, 10 years); “Does the end of the world exist?”13 (Brahim, 7 years). These existential enigmas unify the children in a community of thought, triggering an awareness that breaks down individualities and establishes a space for an intellectual encounter.

In the same way, these issues are defined by their complexity and immensity- which is why they continue to resist our analysis - and therefore require mutual efforts to explore them. They create a cognitive imbalance, a doubt, so that their difficulty encourages each person to call on others to find a meaning together. During the workshop, children, facing a difficult question, will often experience moments where their pairs will offer an idea that will enrich them. By perceiving the usefulness of discovering the different answers possible, they will start to listen more carefully, to take a moment to understand the idea of their peers and will begin to open their mind to others. Thus, the children will take the path of a specific epistemic approach: the suspension of judgements and prejudice, the épochè of the conscience - a state of mind which, according to Sarah Davey Chesters (Davey Chesters, 2012), constitutes a condition for the possibility of authentic dialogue. This cognitive behaviour is also conducive to the development of caring thinking, as they learn to silence their individual stream of thought in order to truly make place for the ideas of their peer, in all its singularity:

“(The theme of caring( reveals itself in the continuity of dialogue in which the children continually discuss issues of mutual importance while retaining respect for one another’s points of view. (…) As the children discover one another’s perspectives and share in one another’s experiences, they come to care about one another’s values and appreciate each other’s uniqueness” (Lipman, Oscanyan, Sharp, 1990: 199).

Philosophy, as a field characterised by the effort to tackle difficulty, is a perfect field to engage children in open-mindedness: the difficulty leads us to mutual aid and to the act of suspending our thoughts in order to be attentive to one another’s ideas.

Finally, these universal questions give rise to many possible, plural and divergent responses, so that philosophical reflection is intrinsically an open, pluralistic and collective activity. Thus, in the third place, it encourages open-mindedness as a space for sharing and exchange: philosophical thought can only be built collectively, for which reason Lipman states that caring thinking is a necessary condition for rational thinking(Lipman, 2003). During a philosophy workshop, the children find themselves in a relational environment where interactions are governed by the laws of reason (and not of power) and those of benevolence: the aim is to listen to the ideas of others and take account of them in order to react.

1.3 the observation of philosophical discussions, a collective practice of open-mindedness

The aim of our research was therefore to observe the signs of open-mindedness, clues revealing the fact that the participants had grasped the ideas of others, understood them and assimilated them. These actions could manifest themselves through different cognitive actions: if a child translated the ideas of another, if a child proposed an idea that completed that of another, if a child embellished the proposition of a comrade with an example, if a child reinforced it using an argument, if another revealed the assumptions or consequences of a hypothesis, if a child proposed an image or metaphor to explain a theory, and many other further examples. All these acts of thought revealed the fact that intellectual empathy opens the mind of children to the ins and outs of the ideas of others, and thus could construct a true philosophical dialogue based on the intersubjectivity and reciprocal interpenetration of intelligence (Daniel, 2005). But these cognitive acts are not only intellectual, as they lead to an ethical posture: by opening their mind cognitively, children end up opening themselves up ethically.

2. results: a few markers of open-mindedness

Among all these clues, we chose to analyse three markers of open-mindedness in more detail. These markers correspond to thinking skills that are developed in philosophical thinking, as well as philosophical thinking relies on them. They will be substantiated thanks to extracts of philosophy workshops that took place during my doctoral experimentation.

2.1 a first marker of open-mindedness: the complementarity of ideas

Philosophy can be conceived as an effort to develop ideas in order to build a conceptual system that will inform the world. From this perspective, the first marker of open-mindedness is the complementarity of interventions. This way of interacting in a constructive manner is a significant practice for citizenship: far from debating through competitive and aggressive rhetoric, openminded discussions enables children to truly build a collective reflection, assembling all pieces together. For example, according to Lipman’s pragmatist method, inherited notably from Charles S. Peirce (Peirce, 2002), collective reflection aims to build one’s ideas according to different contributions classified in several types: hypotheses, counter-hypotheses, analysis of hypotheses, arguments, counter-arguments and examples. This reflexive co-construction formulates intersubjective work and is indicative of the breaking down of barriers between minds, as can be seen from this extract:

“(Facilitator(: So what is the possible?” - (Child 1: hypothesis( It is something that one is able to do. - (Child 2: counter-hypothesis( The possible is also something that can happen. - (Child 3: analysis of the first hypothesis( But sometimes, it is possible for someone to do something, but not everyone is capable of doing it. - (Child 4: example( If someone cannot reach the top of the shelves, but someone else can do so. OK, so this thing, is it possible or impossible ? - (Child 5: argument( It is possible because there is someone else who can do it. - (Child 6: counter-argument( Yes, but if you can climb on a chair to do it, then the impossible becomes possible (…). - (Child 7: hypothesis( Well, sometimes it is a question of courage… there is always a fear in the background that you will not be able to do it. If someone tells you it is not possible, it is up to you to choose whether you agree or disagree. - (Child 4: counter-hypothesis( But no, you can just decide that something is possible. Can we have everything we wish? Is everything possible? - (Child 7: argument( Perhaps if our dreams exist, we can live them. If they do not exist, we cannot live them. - (Child 3: hypothesis( Well, that depends on the dreams… you can dream about impossible things. - (Child 13: example( Yes, like flying. Are there things that are impossible in real life? - (Child 1 : hypothesis( There are people who say “Nothing is impossible”, but there are things that are impossible. - (Child 5: example( You cannot stop time. - (Child 2: example( For example, you eat a cake, and once you have eaten it, it is impossible to eat it again. - (Child 12: argument( Not everything is possible: for example, you cannot bring the dead back to life, they are dead. - (Child 3: counter-hypothesis( For the moment it is impossible. For the moment it is impossible, but in the future might it be possible? Are there things which seem impossible but which then happen in real life? - (Child 2: hypothesis( Well, yes. There are impossible things that you can do. But if you can do them, why are they impossible? - (Child 7: example( For example, if someone wants to resuscitate someone else, even though they know it is impossible, one day they might decide to invent something that can resuscitate people. If he tries, if he believes, then perhaps he will succeed. - (Child 12: hypothesis( Sometimes you believe you have limits, but our limits can also go quite a long way. - (Child 14: analysis( In our minds, anything may be possible. The question of invention is interesting. When you push back the limits of the possible, when you invent, does that mean that with your mind you can make impossible things possible? Is it impossible to become possible? (…) - (All-child 1( Yes! The impossible can become possible! With inventions! You create something new that no-one else has imagined. - (Child 15: counter-hypothesis( I don’t agree: what is impossible will always be impossible. - (Child 6: example( No, the impossible can become possible. For the moment, it is impossible to live on Mars, but perhaps in future years it will be possible (…). - ( Child 11: argument( Yes, because they can create something, invent a system. So if you invent something to go and live on Mars, does the impossible become possible? - ( Child 4: counter-argument( Yes, but there are some things where you can do nothing, and they will remain impossible for ever. (…) - ( Child 2: hypothesis( There has to be a limit: if everything were possible, life would be much too simple. - ( Child 1: analysis( You cannot put off the impossible and give yourself challenges! - ( Child 12: argument( We need limits because otherwise it would be a disaster! It is because of or thanks to Nature that we are alive, so she has made laws to prevent us from doing things. - (Child 1: counter-hypothesis( Or otherwise it would be a wonderful life. - (Child 8: hypothesis( It is normal that life is not completely perfect !”14

All through this discussion, children show their ability to think collectively, to collaborate and debate by constantly interacting. For example, at the beginning of the text, the child 3 says that “sometimes, it is possible to do it for someone else, but not everyone is capable of doing it” and just afterwards, the child 4 complete that hypotheses with example: “reaching a shelf”. Just afterwards, the child 7 proposes a hypothesis regarding the variations in capabilities between people: “Well, sometimes it is a question of courage… there is always a fear in the background that you will not be able to do it. If someone tells you it is not possible, it is up to you to choose whether you agree or disagree.” To that the child 4 responds by expressing his disagreement but most importantly, by reformulating the hypothesis: “But no, you can just decide that something is possible”. At the end of the abstract, the child 1 declares: “The impossible can become possible! With inventions! You create something new that no-one else has imagined.” But his classmate, child 15, immediately reacts to his exclamation with a counter-hypothesis: “I don’t agree: what is impossible will always be impossible”. All these moments show the presence of dialogue and intellectual collaboration. One can imagine how this ability could be translated in a public debate, as citizen agents. They have acquired the capacity to think collectively, to cooperate in the elaboration of a debate: open-mindedness enables them to intervene in complementary to the collective path.

2.2 a second marker of open-mindedness: nuances and influences in the philosophical thinking of children

During this work on the collective construction of reflection, open-mindedness was revealed during the interventions of different participants, thanks to the nuances and influences incorporated by the children in their ideas in light of those of their comrades. This is an example of a discussion during which one pupil, Ornella, changed her ideas as a function of the collective development of thoughts with her comrades:

(Facilitator( Do we need other people to live? - (Child 1( Well yes, because if you are alone, you will be bored and you won’t be able to communicate. - (Child 2: Ornella( We need other people. It is as if: I am going to make something to eat, I will need others to make the food and to eat it. (…) - (Child 3( Yes: we need others if we become sick. (Facilitator( So we need others to help us, to look after us? - (Child 3( We need them, yes and no. That depends. Yes, for example if you are sad, your friends will reassure you. And as Ornella said, to cook for you. But there are other things you can do alone. - (Child 4( We need others to share our feelings. (Facilitator( Could we live if we felt nothing? What would life be like without feelings? - (Child 4( Well, we would not be happy. Because if we have no feelings, you cannot live all alone, all the time, without anything to love. - ( Child 5( We need other people. For example, we need farmers because we don’t know how to produce food, and without them we cannot eat. - (Child 6( A life without feelings is not a real life. Because if you have no feelings, you cannot feel things. You have no friendship, you cannot really feel friendship. - ( Child 7( You could not be happy or sad. - ( Child 8( If we had no feelings, we would not be able to feel that others need help. - ( Child 2: Ornella( So I will change what I said: we need others to eat, but above all we need them to live with feeling, to be happy”15

In this short extract, we can see that Ornella starts with a utilitarian view of others (they help us to eat) and the listens to her pairs and incorporated some new ideas: the idea of living with feelings (expressed by Child 4 and Child 6) and experiencing happiness (expressed by Child 4 and 7). Ornella then blends her initial view with the alternative ones, demonstrating intellectual empathy, the attention given to others, without losing herself. She is still the agent of her ideas, but also shows the ethical capacity to nuance her view by truly take into account the ideas that appear in the dialog. This idea can be contested, it is linked to the vision of autonomy defended by Lipman: according to the American philosopher, an autonomous thinker is not an agent that thinks alone, it can be an agent that thinks with others. “It is not uncommon to confound thinking by oneself with thinking for oneself and to be under the mistaken impression that solitary thinking is equivalent to independent thinking. Nevertheless, we are never so moved to think for ourselves as when we find ourselves engaged in shared inquiry with others. The way to protect children from uncritical thinking in the presence of others is not to compel them to think silently and alone but to invite them to think openly and critically about contestable issues.” (Lipman,1988: 156). Autonomous thinking is not conquered against others, but in a close interaction with them.

2.3 a third marker of open-mindedness: the search to reformulate and explain the ideas of others

It is when apprentice philosophers hear what is not said explicitly that they reveal their true open-mindedness towards the words of others. Thus, when they manage to reveal what is implicit or provide informative reformulations, they are making a significant intellectual gesture: that of grasping the idea of another to the point where they understand the sub-text. Not only are they open to what is said, they are searching for the unsaid: this is true intellectual empathy. The search to reformulate and explain the ideas of here is, therefore, a third marker of open-mindedness. Here are a few examples of this phenomenon where the children tried to grasp what lay between the lines, was implied and implicit in the thoughts of others:

«(Facilitator( So in your opinion, what is the use of living?

- (Child 1: Ingrid( Life serves to spend good times and be happy in your life

- (Child 2: Kevin: explanation( Life is when you are born and you are a baby, and you live good and not so good times. You live.

- (Child 1: Ingrid: reformulation( Life is times of happiness and times of sadness

- (Child 3: Sira: explanation( I think - in my opinion this is what Ingrid and Kevin think too - that life is like a sort of test that happens between good times and bad times.

- (Child 4: Maxence: reformulation( I agree with Kevin’s idea: why are we born and why do we die at the end? Why can our existence not continue for ever?

- (Child 5: Amélia: reformulation( I think the same thing, I think that life is as if we enter the world and then a few years later we die.

(Facilitator( So for you, the definition of life should be “what happens between birth and death”

- (Child 6: Karim( Life is when you will grow up to have a good career or… I don’t know.

- (Child 7: Kenza: reformulation( I think that life is …. If you do bad things, you will go to hell, if you do not do bad things, you will go to paradise

- (Child 8: Roxane: explanation( that depends on the religion. When you don’t believe in God, you think…

- (Child 10: Mohamed : explanation( Karim, I think he wants to say that life is not just being born and dying, it is to try and do great things

(Facilitator( Could you try and express this in your way?

- (Child 10: Mohamed : reformulation( Life is being born, living times that may be good or bad, and after that you die.

- (Child 12: Inès( Life is a bit like a reward, except for wicked people.

- (Child 6: Karim: reformulation( We have an incredible chance to live, and thanks to life we can have unforgettable times. I agree with Mohamed but it is mainly the good times that are important; there are bad times but that is not the purpose of life.

- (Child 14: Nihed: reformulation( Sometimes, you have incredible experiences that you could not have imagined, and then you say that it is great to be alive, it is like a gift.”16

In this extract, children not only deliver reformulations and explanations of one another’s ideas, that also reveal their willingness to be collaborative and to truly understand their pairs: “in my opinion this is what Ingrid and Kevin think too…”, “I agree with Kevin’s idea”, “Karim, I think he wants to say…”, “I agree with Mohamed…”. These words explicit their engagement in the community of philosophical inquiry: indeed, they try to construct their interventions in an intricate intellectual proximity to their peers. These movements of reformulation and explanation can be seen as a utilisation of translation skills: these children translate the words of their philosophical collaborators into their own words. And by doing that, they can be changed: in this regard, translation skills are linked to creative thinking. By translating the ideas of others and being open to them, one can evolve and create new ideas. We can see here an original conception of creativity: indeed, it can be fostered by collective dialogue and not only solipsistic research. Ultimately, open-mindedness is a gateway to philosophical creativity.

3. discussions about the ethical significance of open-mindedness in philosophy.

It is the ethical consequences of practicing philosophy that are at the heart of the discussion, particularly since this pedagogic innovation appears to have a significant effect on the moral education of children.

3.1 the ethical significance of philosophical education and open-mindedness

It is evident that the open-mindedness is not devoid of ethical challenges: indeed, once children become involved in these intellectual approaches to the co-construction of reflection, it goes without saying that they will place themselves in the position of listening to, attending to and understanding others and thus adopt an empathetic attitude. It seems that the intellectual positioning of philosophy spontaneously draws children towards an ethical positioning: reasoning, reflection and conceptual progress require the adoption of ethical positions by interlocutors, so that an inevitable shift occurs between the intellectual form of the exercise and its ethical significance.

The intrinsically ethical and social dimensions of philosophical debate have a well-known consequence: that the philosophical method itself contains a civic value and - if I may say - a ethical value. But much debate has focused on the role of philosophy for children in their ethical and civic education, and in this respect, we feel that philosophy for children can in some way be content with the ethical nature of its processes and should not constantly restrict itself to addressing moral issues so that philosophical education will have an ethical significance. We feel that this confusion is damaging, insofar as it restricts discovery of the world of ideas to the frontiers of moral philosophy. On the contrary, we feel that if philosophical debate becomes a true discussion, it has an ethical and political force independently of the theme being addressed: for example, if the children manage to debate in a respectful, constructive, good tempered and open manner regarding the question of joy, this workshop will have a moral content comparable to that of a workshop focused on good and evil. A philosophical discussion between children, as a place of open-mindedness, of collaborative thinking, of mutual aid, is, in itself, by this method, a civic and ethical practice.

3.2 the empathy movement of open-mindedness and its relativist limitations

The second controversial point concerning the desire to make philosophy a radically open practice is to engage thought in a relativist idiosyncrasy: indeed, some detractors consider that such an opportunity to think governed by empathy towards others may encourage children to accept all ideas without considering their value, foundations or veracity. This preference deserves to be channelled but without condemning the principle of empathy: indeed, an empathetic approach does not prevent the evaluation of an idea or its critical analysis. Nor does it prevent the expression of discord or incompleteness. On the contrary: it is only by opening one’s mind to the ideas of others that one can truly criticise them, once they have been fully grasped and understood. We therefore feel that far from committing children to a relativist practice, philosophy enables a better application of a critical mind because its empathetic dimension will ultimately permit them to understand the ideas of others from the inside. I would as far to say that open-mindedness is a condition for the possibility of critical thinking, as a way of approaching and encountering the idea one wants to criticize.

3.3 the conceptual interventionism of open-mindedness versus tolerance.

When practising philosophy, children are encouraged to take hold of the ideas of others so that they can apply their own thoughts to them. Thus, the process of open-mindedness, of intellectual empathy, leads to a handling and juggling of ideas, insofar as philosophy for children encourages even the youngest to become involved; the aim is always to intervene on the ideas of others and their own. When an assumption is revealed, we can inform a blind spot; when an argument is put forward, we can give additional force to an idea; when we give an example, we can transform that idea into a concrete and imagined situation. All these collective acts will mould the idea and do not leave it in its original state. This approach to the openness of a philosophical mind is radically opposed to promoting tolerance and is therefore debatable. Indeed, the ethical model of tolerance seeks more to ensure the remote and distant acceptance of others and is defined by non-intervention: according to Susan Mendus, “it consists in abstaining from intervention in the actions or opinions of other, even if one has the power to do so and even if one disapproves of or does not appreciate the action or opinion in question.” (Mendus, 2004: 1969). Tolerating others means leaving them free to be what they are, without seeking to discover any more. On the contrary, the defence of intellectual empathy, as it manifests in open-mindedness, is that it can break down this relationship of exteriority to allow otherness to enter the mind, thanks to a form of conceptual interventionism. Through philosophical discussion, children experience a true encounter with the intellectual, metaphysical, political, ethical and aesthetic worlds of their comrades and by these means open their young minds to the pluralistic and diverse wealth of the world of philosophy.

conclusion: the discovery of radical otherness

In short, philosophy for children offers us a key to understanding the cognitive functioning of the very young. While child psychology, as notably advocated by Piaget (Piaget, Inhelder, 1966), has long considered that childhood thoughts were restricted to a form of egocentrism which places the mind in a situation of introversion, philosophy for children is based on a socio-constructivist concept of cognitive development17. It is this facet of children’s intellect - open to exteriority and otherness - that is evidenced by philosophical discussions. We position ourselves in parallel with egocentric confinement and as from the age of five years gamble on the collective deployment of socialised thought through philosophical dialogue. And in fact, when children place themselves in a situation of truly listening, when they are ready to fully welcome the ideas of others and to try and embrace them for what they are, one might consider that they are demonstrating their intellectual empathy: by opening their minds, they have started to think with others.

Furthermore, the framework of philosophical discussion - governed by reason and goodwill - enables a relaxed encounter between divergent individualities. Indeed, such discussions often give rise to the emergence of personal, social, religious or political variations. Differences appear, creating a substrate for philosophical reflection, but they must be defended by rational, universal and reasonable arguments in the context of benevolent communication. Thus, these distinctive singularities are both revealed and channelled by the philosophical method: above all, they are opened up to all. Dialogue exists through the verbal confrontation of "diverse rationalities" (Pettier, 2004) but survives through the inclusive, open, empathetic and respectful nature of this confrontation. Without the management of differences, dialogue disappears: it can evolve towards dispute, hatred, silence and the assumption of power. In a word, the actual existence of philosophical discussion is tributary to the intellectual empathy movement realized in open-mindedness, which is therefore central to its achievement. This true unveiling of plurality and diversity is not only stimulated by philosophical discussions: it engages children to accomplish a crucial civic act: opening a door in the mind to welcome, with curiosity and precaution, the idea of a fellow citizen about our shared existence.