introduction

When Mathew Lipman first introduced Philosophy for Children (P4C) to the world, his goal was not to sneak a little academic philosophy into the typical school curriculum, as one might expect from the titles of his first books: Philosophy in the Classroom (Lipman et al., 1980) and Philosophy Goes to School (Lipman, 1988). His goal, rather, was to create a paradigm shift in the field of education itself: to turn common educational practices upside down. Common educational practices can be variously described as “the sage on the stage,” “the banking model” (Freire, 2018), or even as practices of oppressors (Kohan, 2011). Though obviously such practices vary widely throughout the world, the common theme is the assumption that it is the teacher’s responsibility to transplant what is in her head into the heads of her students

Philosophy for Children eschews this model. While the teacher is still considered important (though now under the new title of “facilitator”), under this model s/he is important not for what s/he can give to the students, but for what she can solicit from the students. S/he is important insofar as s/he is able to create Communities of Philosophical Inquiry (CPI’s) whereby students come together and inquire with one another about the best possible answer to questions that are genuinely relevant to the students’ own lives. As a facilitator, her job is to create “meeting”-a space whereby s/he and all the participants prod one another to consider the assumptions that underlie their claims, to consider counterexamples to positions that they hold, and to recognize implications of what they say. It is in this sense that facilitators can be described as meeting participants in CPI’s “where they are at.”

Various scholars have focused on the myriad of potential benefits that might accrue to students from engaging in this upside-down or non-hierarchical educational process, which include empathy (Schertz, 2007), caring for others (Sharp, 2004/2018), a passion for truth (Gardner, 2015), and the evolution of selves (Kennedy, 2006). Here, though, the focus will be on exploring, in more detail, what precisely is required for an educator to justifiably make the claim not only that her approach is indeed non-hierarchical, but, more importantly, that it has the advantage of avoiding the often invisible disadvantages of a more hierarchical model. Specifically, it will be argued that in order to make this claim, the educator needs to ensure that her strategy avoids the disadvantages of a top-down because it :

1 nourishes agency; 2. Embraces the process rather than the results; 3. Encourages learning to flow with mistakes; 4. Includes a large dose of fun; 5. Has a method whereby effectiveness can be insightfully evaluated; and 6. Offers insightful self-evaluation of the educator.

In what is to follow, we will begin with a cursory overview of the advantages of a “through and through” top-down educative hierarchical model. Clearly, if an argument against this model is to be convincing at all, it is critical that it begins with an acknowledgment of its most obvious advantages. We will then outline, how a hierarchical model falls short on the six factors mentioned above. From there we will explore two examples, one in a P4C summer camp and one in a soccer coaching setting, to demonstrate how an educator can estimate the degree to which she has avoided the often invisible disadvantages of a top-down model. We will conclude by suggesting that keeping in mind the six disadvantages of a hierarchical educative model outlined here might assist those in the P4C world to be aware of the potential that, in becoming wide-spread and traditional, the CPI model might itself be morphing into a top-down force.

advantages of top-down interactions

While for some, the tendency to engage in a through-and-through top-down educative model may seem egoistic and nefarious on the surface, we suggest that quite the contrary is true, which is why it is so hard to stem. Let us explore briefly why this model is so entrenched in school, in soccer coaching, and in parenting.

in school

Gardner and Wolf in their paper “Thinking and Knowledge, the Past and the Future: An Energized Mesh,” (under consideration) note that “while the world-wide arms-race may be at a stalemate, the knowledge-race is just ramping up, and any tribe who falls behind will simply be extinguished.” Given this knowledge race and given the vicious competition for knowledge-based jobs that quite literally knows no borders, surely it would be irresponsible for educators not to try to stuff as much knowledge as is humanly possible into young citizens. Echoing this sentiment, Thomas Friedman, in his book The World is Flat, gives this advice to his daughters:

Girls, when I was growing up, my parents used to say to me, ‘Tom, finish your dinner-people in China and India are starving.’ My advice to you is: Girls, finish your homework-people in China and India are starving for your jobs. (p. 237)

Finish your homework: how tedious! Still, given the mountains of information and skills that are essential for future citizens to compete with any hope of success, and given the stamina and hard work that will be required in any future job, it can at least be argued that we will not be doing our students any favors if we try to sugar coat what is required of them for future success by trying to make the process more palatable now.

in soccer

In soccer, there has been a proven method of producing the highest quality players through the top-down model. At the youngest ages especially, repetition of key fundamental techniques will improve the players’ ability on the soccer field. Strict technical executions that must be made when passing, dribbling, shooting, or even bio-mechanic techniques for sprinting, stopping, changing direction need constant repetition if they are to be elicited, without thought, in the chaos of an actual game. Just as the time for carpenters to learn how to wield their tools is not when they are on scaffolding fourteen stories above ground, and just as it is imperative that surgeons learn to prefect their suturing skills on pig’s eyes in a lab long before being required to suture a detached retina of one of their patients, so too in soccer, it is essential that players have sufficient practice before execution.

Further, it has been shown that players recovering from injury, or very young athletes who are completely new to the game can benefit from isolating decision making and the execution of a decision (technique) from one another. So, a player returning from injury can still train without opponents or their teammates to ensure they are not injured - but still be able to train. A very young player who has never kicked a ball will not find success in a game scenario, especially against skilled opponents, without first learning some basic comfort in controlling the ball isolated from a game context.

in life

Adults, who have managed to lead lives that are not solely ones of quiet desperation1 (Thoreau 1910), often believe that they have figured out ways to avoid being crushed by life, and they earnestly hope that they can pass this wisdom on to the youngsters for whom they care. Who among us does not remember how stupid we were when we were younger, and who of us does not wish earnestly that we knew then what we know now?

Reinforcing this tendency of adults to refrain from attempting to meet youngsters “where they are at” is the assumption that there is no “at” there to meet. If there is no rising dough within, adults have to put it there and then sculpt in light of an ideal. Many adults, in other words, assume that youngsters are tabula rasa, blank slates or empty vessels. Kohan (2011) describes the situation as follows:

In the Republic, it is someone external-the educator, the philosopher, the legislator of the polis-who will give form to another who in himself has no form, and who is not considered capable of finding it by himself. To give someone a form; to inform her: education is understood here toute simple as the formation of childhood. In this approach, education is normative, adjusting what is to what ought to be. (p. 340)

Yet another reason why adults so often fail to meet youngsters “where they are at” is because meeting youngsters “where they are at” is such hard work! Gardner (2011) recognizes the importance of this issue in her article “What Would Socrates Say to Mrs Smith?” when she has Mrs. Smith responding to Socrates’ recommendation that she reason with Johnny about going to bed, that “this seems like a lot of trouble to go to when all I need to do is march in there and switch off the TV” (p. 26).

summary

A hierarchical educational model thus, at least on the face of it, has distinct advantages. As a schooling practice, this model seems necessary for countries and its citizens to effectively compete in the knowledge economy; in the sports arena, this model ensures that coaches can effectively train isolated moves that, hopefully, will then be elicited automatically within the chaos of an actual game; in life, this model opens up an avenue for adults to most easily and effectively pass on to those they care about the hard-earned knowledge that they deem essential for living a good life. Thus, given that, in all these situations, an educative hierarchical model seems to have distinct advantages, it is imperative that we attempt to outline, in a digestible form, what shortcomings are inherent in this model. It is to that task that we will now turn.

shortcomings of top-down interactions

1. hierarchical education fails to excite agency.

In their paper “Authenticity: It Should and Can Be Nurtured” (2015), Gardner and Anderson argue that an intentional concerted effort must be undertaken in order to create an educational strategy that nurtures agency, or what they refer to as “authenticity.” Though outlining specifics is beyond the scope of this paper, suffice it is to say that giving youngsters facts to memorize and telling youngsters what to do and when to do it, if successful, will foster dependent replication, rather than agents confident about taking the reins.

This pressure to replicate undermines the hope that lies in what Hannah Arendt (1958/2013) refers to as “natality" or the "miracle of beginning"; the continual arrival of the new that has the potential to create action that will alter the state of affairs brought about by previous actions.

This message, in turn, is echoed by Friedman (2005) who makes a compelling case for the fact that, since the world is changing so rapidly and is now so integrated, no one can be shielded from the need for innovation fueled by excellence. This, of course, is true also of non-human entities. Under pressure of the abnormally rapidly changing biosphere, it is evident that germs, capable of lightening-speed innovation, will end up being the superstars.2 And that is Friedman’s point: we, as a species should be like germs. We must innovate or lose. Even sports are not immune to this pressure, as was evident in the recent discussions within the German Football Association with respect to their national identity and player development models. The national team sporting director for the German FA, Oliver Bierhoff, stated in a recent interview that “the country needs a reform similar to the reform the country underwent following the exit of the Euro 2000” citing a lack of individual creativity in solving problems as the reason.

From our point of view, fostering agency is even more important for the wellbeing of youngsters. The true wonder of creating meeting for youngsters is that youngsters then participate in their own development and thus have the opportunity to enthusiastically embrace the responsibility for who it is that they are becoming. The true wonder lies in youngsters’ own wondrous surprise at witnessing their own potential becoming actual. Wow! Look at me! Who knew that I could do this? And who knows what I might yet be able to do? It doesn’t get any better than that.

2. hierarchical education teaches an over-evaluation of the result, rather than a love of the process.

It is not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game. Who hasn’t heard that mantra? However, in light of the pressure to get good marks, to win the game, to be the offspring of whom parents can boast, who has ever believed that?

This is not to suggest that results are unimportant. Without an eye on results, the process would have no value. It is only to suggest, rather, that the tilt should be in favour of the process rather than the result. It should never occur to a youngster, in other words, that cheating is a smart strategy even if s/he can get away with it, or that it is natural to be smug about winning a game or crestfallen about losing, or that lying to parents about making the wrong decision is justified in order not to disappoint. For all such youngsters, it is evident that what is important is the result-a viewpoint that they have introjected from the educators in their lives.

The goal should be, by contrast, for young people to courageously tackle the situations which they face on the assumption that criterion for both self and other-evaluation is a function of the vigor and effort put into the process, not on whether their efforts were successful. Which brings us to the next point.

3. hierarchical education precludes opportunities for “oops.”

Given ever-changing circumstances which we all face in all the endeavors we undertake, there will inevitably be failure, no matter how enthusiastically the process has been adopted and honed. It is thus absolutely crucial that students have the opportunity to learn how to experience failure as an “oops”: as an opportunity for learning and growth, rather than as definitional of who they are. In his book, How We Decide (2010), Jonah Lehrer argues that neuroscience has shown that the dopamine that is released with the shock of making a mistake is ultimately how we best learn. He says that “unless you experience the unpleasant symptoms of being wrong, your brain will never revise its models. Before your neurons can succeed, they must repeatedly fail. There is no shortcut for this painstaking process” (p. 54). As a result, he says that “kids will never learn how to learn if they think that mistakes are a sign of stupidity rather than the building blocks of knowledge” (p. 52).

Robert A. Burton in his book On Being Certain (2005) makes a similar case when he says that teaching for correct answers and the right way of doing things reinforces a tendency toward embracing certainty which, he argues, is mental flexibility’s worst enemy (p. 101). Thus, he says

I cannot help wondering if an educational system that promotes black or white and yes or no answers might be affecting how reward systems develop in our youth. If the fundamental thrust of education is “being correct” rather than acquiring a thoughtful awareness of ambiguities, inconsistencies, and underlying paradoxes, it is easy to see how the brain reward systems might be molded to prefer certainty over open-mindedness. To the extent that doubt is less emphasized, there will be far more risk in asking tough questions. Conversely, we, like rats rewarded for pressing the bar, will stick with the tried-and-true responses. (p. 99)

4. hierarchical education is no fun!

No kidding! Sitting in a classroom, trying to keep one’s eyelids propped open, as the teacher drones boringly on about a topic that seems to have absolutely no relevance to one’s life can be torture. So too can a drill in which one is forced to acquire a technique through boring repetition on pain of being forced to do suicide laps if no improvement becomes evident. And how about trying to figure out what demeanor ought to be adopted while being lectured at by a parent over one’s shortcomings?

In some developing countries, kids are risking violence, even death, in search of education, while, in the developed world, kids hope longingly for a snow-day in order to skip school, to say nothing of the fact that many drop out altogether. How can this be? Surely there should be an intrinsic reward for feeling and believing that one is better able to tackle the world in which one finds oneself. If this is the case, then the fact that education is not fun suggests that there is a serious problem.

5. hierarchical education often misevaluates effectiveness.

French is one of the official languages of Canada; and the primary language in the province of Quebec. Yet one of the authors, who grew up in Quebec, who had 12 years of French education, and who consistently placed at the top of her class for marks, speaks little to no French. But if a consistent A does not indicate that the student has mastered the subject, what does it indicate? Many might suggest that it indicates simply a proficiency in writing exams. However, since the mark wasn’t for a course entitled “exam writing,” there is surely something wrong with this method of evaluation.

The mirror image of getting misevaluated A’s, is getting a failing grade as a novice in any discipline. This is particularly true of mathematics, which is a source of great anxiety and even phobia for many students. The most common cause of math phobia3 is the crushing fear of time-limited tests in which specific answers are required, and which, if not forthcoming, will have unimaginable negative consequences. Exams in this situation destroy, rather than enhance, learning.

None of this is to suggest that exams are always inappropriate. Most of us would like those in life-altering professions to be required to show that they can operate on patients, fly planes, and build bridges. Exams may also be appropriate for streaming in various parts of the educational system. However, all educators ought also to have, as part of their arsenal, other methods of evaluation that more closely mirror the hoped-for outcome, and which are less intimidating to those being evaluated.

6. hierarchical educators often misevaluate themselves.

Those of us who have had the privilege of being a sage on the stage know how exhilarating it can be to create what seems like a blockbuster lecture. It is also a relatively risk-free enterprise, as everything that needs to be covered is preplanned, so one anticipates that there will be few surprises. One also, of course, foresees the glow of being admired for one’s enormous sagacity

And those of us who have had the privilege of coaching a sports team also know the sense of smug satisfaction that accrues from putting young athletes through a gruelling set of intricate drills that is a spectacularly wondrous spectacle for parents who are paying the bills. Indeed, some coaches become world famous, even rich, by putting on coaching top-down seminars in which novice coaches are put through various tortuous experiences, e.g., Raymond Verheijen of the World Football Academy.4

Though such top-down educators “see” how good they are, the fact that the evaluation is restricted to the top alone, suggests a problem, namely that the value accruing from such experiences may be disproportionately piling on at the top and that, therefore, a self-evaluation ought to at least consider the flow between the top and the bottom.

summary

In summary, then, although a top-down educative approach has many advantages, it also has distinct disadvantages that, we suggest, ought to be kept in mind by all educators, professional or otherwise. These disadvantages are that a top-down educative strategy (1) risks forestalling the growth of agency and its innovative power; (2) risks sending the message that only results count and in so doing, under-values the importance of embracing the process regardless of the result; (3) risks inadvertently sending the message that mistakes are bad, rather than a wondrous opportunity for learning and growth; (4) risks creating an atmosphere which is patently aversive, and in so doing losing the cooperative attention necessary for any learning to transpire; (5) risks seducing the educator into using short-cut evaluative processes that evaluate only that which is easy to evaluate; and finally, (6) risks fooling the educator into evaluating the learning process solely by focusing on the educator’s own performance.

In light of these disadvantages, which are often invisibly imbedded within the hierarchical model, we will now explore how these disadvantages can be avoided within a non-hierarchical educative framework. We suggest that, given the distinct advantages of the hierarchical model, educators who embraces a non-hierarchical strategy must ensure that they, too, do not inadvertently fall prey to these disadvantages on pain of losing any credibility that their method is superior.

a non-hierarchical educative enterprise

The best way to explore a non-hierarchical educative enterprise, and in particular, how it can avoid the disadvantages outlines above, is by example, two of which are forthcoming. In general terms, though, it is important first to stress, that while a non-hierarchical educative enterprise is not top-down, it nonetheless requires enormous effort, energy, input and understanding at the top in order to, not just make room for a lot from the bottom, but to solicit it. The implicit assumption of all education, after all, is that those who are to be educated have a potential which the educative encounter is supposed to help bring to fruition-a potential of which even the individual herself may be unaware. The hierarchical educator hopes that stuffing new facts and skills and ways of being into an individual will nudge growth. The non-hierarchical educator believes that a more sustained and deeper growth results when responses are first elicited from challenging, constantly evolving, ingenious goal-oriented contexts, which then affords the possibility of meeting in order to prompt reflection on the adequacy of responses. It is in this sense that non-hierarchical educators can be described as “meeting-makers”: they meet their charges where “they are at,” and create meeting between them, after having solicited responses from goal-oriented contexts.

Given that such meeting-making has the disadvantages of being hard work and requiring huge ingenuity, while lacking the easy positive self-evaluation open to top-down educators, we suggest that, in order to make the case that this model is indeed superior, meeting-makers must be sure that they succeed where hierarchical models tend to fail by keeping the following questions in mind:

in a summer p4c camp

The Thinking Playground (TTP) is a P4C summer camp put on by the Vancouver Institute of Philosophy for Children (VIP4C) and the University of the Fraser Valley (UFV) in Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada. Every summer, it offers 2 weeks of 8-hour-day summer camps that focus on varying themes. The goals of these camps is to create activities that are so engaging and so much fun for the youngsters (ages 6 to 13) that they rarely notice how much they are learning5. The following example of a recent activity helps underscore how the disadvantages of a top-down educative model are avoided.

activity

A group of 15 campers was divided into 5 groups. Each group of campers was asked to place three photos on a scale drawn on the floor that ranged from “1: I think it would be terrible if this entity went extinct” to “10: it doesn’t really matter if this entity goes extinct.” A set of photos was given to each group that might include, for instance, a photo of small bee, a photo of a tiger, and a photo of a human. Once the photos were placed, the groups got together and engaged in a Community of Philosophical Inquiry (CPI) to discuss why they placed the photos where they did, as well as to dialogue about any discrepancies. They were then given the option of changing their placings. Evaluating this activity using the 6 criteria above, yields the following results.

1. agency.

What is important to note about this activity is that unique viewpoints about both animal extinction and potential human extinction were solicited from the campers that, absent such an environment, may never have found life. What was also important is that the facilitators, both of the individual groups and the combined groups, continuously challenged campers and nudged them to challenge each other for why they gave the reasons that they did, and to continuously judge the adequacy of their own positions relative to other positions articulated.

2. process rather than results orientation.

It is of note that this activity did not set out to teach the campers that animal extinction is a bad thing. Nor was the goal simply to create an activity to enhance reasoning skills. The goal was very specific, namely to offer campers the experience of being able to think together, effectively and deeply, about this particular issue and to recognize that such thinking is filled with such complexity and doubt, that no obviously right answer is available, even though it become evident that some positions seemed better than others.

3. the “oops” factor.

There were all kinds of “oops’s” throughout this activity-oops’s that tended to generate laughter rather self-denunciation. There was an “oops,” for instance, when it became evident to the group who rated bees low in importance that that might seriously diminish pollination and hence food for the humans whom they had rated as highly important. A similar “oops” was solicited when it was noted that worms are critical for the health of soil. There was even an oops when the idea was floated that maybe there was something problematic about putting humans at the top of the scale, since humans seemed to be the cause of the problem of animal extinction in the first place.

4. the fun factor.

Camp is fun. Part of the reason for the joy-filled atmosphere is that campers spend 8 hours per day together for 1 - 2 weeks, and so all communities of inquiry are bracketed by hilarious games, fun-filled crazy competitions, and working together to produce artistic creations. As well, the fact that counsellors are university-aged young people, who themselves are still filled with the joie de vivre of youth, whose job it is to get kids addicted to thinking by showing how much fun it is, and who are volunteers primarily because it is fun, contributes enormously to the wonderfully good time that is had by all.

We also increase the fun factor by encouraging counsellors to facilitate in pairs, which often results in hilarious banter between the two. As well, we encourage all the counsellors in the room (there is never a ratio below 1:5) to participate as ordinary members of CPI’s. This increases the number of antennae on the lookout for “boring,” as well as the number of minds attempting to craft creative ways to keep the inquiry buoyed.

5. evaluation of the effectiveness.

Evaluation of the possibility of success of camp is a function of the degree to which the richness and complexity of the curriculum supports the assumption that the activities will solicit diverse and deeply reflective responses. The evaluation of actual success is the degree to which such responses are actually solicited. Effectiveness is also measured by the enthusiasm that is maintained throughout the process. One of the advantages of the camp setting is that, if boredom appears to rear its ugly head, the session can be brought quickly to a close by moving onto the next activity in the curriculum. Just as we expect our campers to get comfortable with the “oops” factor, so we expect our counsellors to do likewise. Throughout the year, prior to the camp, counsellors meet together to create the best possible experiences for our campers, but they know beforehand that these activities may or may not succeed. They know that if facilitating becomes hard work, or if they themselves get bored, it is time to move on.

6. self-evaluation of the educator.

Given that this is a non-hierarchical educative process, counsellors have two independent factors by which to evaluate how they themselves are doing as counsellors. The first factor is the degree to which they actually bond with the campers, which is not simply knowing campers’ names and ensuring inclusion. This is, rather, a function of being able to understand the strengths and weaknesses of individual campers, and so altering circumstances so that each camper feels that they are surrounded by friends, both of their own age and those who are older. Knowing individual strengths and weaknesses also helps the facilitator problematize the CPI, or engage in digging deeper with specific individuals. The second factor is the degree to which the educative activity was in fact educative. While counsellors have signs for knowing when an activity flops, on the flip side, they are encouraged to estimate the quality of their success by the degree to which they found themselves challenged in precisely the same context which the campers found themselves in (Wolf and Gardner 2018). This was supposed to be, after all, a meeting place.

summary

Putting on P4C summer camps with an all-volunteer army of counsellors and directors requires an enormous amount of ingenuity and effort. It is precisely by knowing that we avoid the pitfalls that often adhere to the easier route of a top-down educative strategy that our enthusiasm for creating an “educative meeting place” is sustained.

in a soccer setting.

Having witnessed the advantage of creating meeting, one of the authors of this paper who is a counsellor for The Thinking Playground, tried to implement a similar strategy in his role as a soccer coach.

activity.

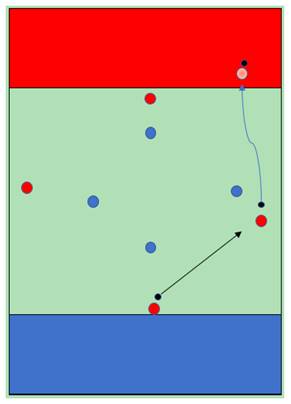

The practice was designed with groups of 4v4 (see Figure1). Players on team red were required to match and defend only ONE player on team blue (and it must be the same player throughout the game), and vice versa. The rules of this practice are as follows: the players who have possession of the ball attempt dribble the ball into the end zone to score points. This context ensures that players get a lot of practice dribbling, a lot of practice defending, and a lot of practice dealing with being defended. This practice can be described as more non-hierarchical than top-down by reviewing how it avoids the disadvantages typical of the latter.

1. agency.

What is important about this approach is that it contrasts vividly with a drills-based approach in which a drill-coach would require players practice dribbling around cones, or practice defending, with the coach constantly calling out explicit moves. In the “meeting approach,” players’ responses are their responses that fit in with their intuitions, their comfort level, and their strengths, as well as their movement solutions that they acquired through the history of their movement up to the point of the training session. As well, in post practice-game sessions, they will have the opportunity to dialogue with the coach and team-mates about what worked best under varying circumstances. Further, since they will have had an opportunity to reflect on solutions that did or did not work, this may enhance their own practice when they have an opportunity to train on their own time.

2. process rather than results orientation.

A drills-based coach tends to focus on teaching what has worked before; let’s try and reproduce results that have been successful in the past. The meeting-coach, by contrast, encourages players to immerse themselves in the process and see what comes out. Ironically, understanding the value of opening a space for the possibility of unique personal responses is well understood in soccer, as is evidenced by the fact one soccer move that is almost always included in a drill-curriculum is “the Cruyff turn.”6 This move was originally solicited completely spontaneously from Johann Cruyff, of The Netherlands in their World Cup Game against Sweden, in 1974. What is perhaps tragic is that the lesson learned from the emergence of this unique move, was not how valuable such spontaneous emergence is, but rather that the product itself is valuable. This interestingly mirrors Dewey’s criticism of education in general, as Matthew Lipman (1991) notes:

John Dewey was convinced that education had failed because it was guilty of a stupendous category mistake: It confused the refined, finished end products of inquiry with the raw crude subject matter of inquiry and tried to get students to learn solutions rather than investigate the problem and engage in inquiry for themselves (p. 15).

3. the “oops” factor.

The activity described above is designed to elicit the natural responses of the athletes to the sorts of challenges they will face in real-game situations. The “oops’s” that inevitably transpire, in turn, prompt the emergence of strategies for searching, discovering, and exploiting opportunities as they arise. As a result, a culture whereby “oops’s” are perceived as genuine opportunities for leaning and growth is fostered.

For this message to be truly anchored, however, it is critical that, on a macro level, in the actual game situation, the placement of players also opens up spaces for “oops.” A coach who is focused on winning, for example, might put a player who is a long kicker as a defender (at the back) and the fast runner as a forward (at the front) so as to increase the chance of the getting the ball and scoring goals. This sends the message loud and clear that scoring is the priority and that therefore “oops’s” are frowned upon. By contrast, if the season is planned out in advance so that players will have an opportunity to play in various positions, it will be evident that what is important is personal growth and that, since all players will not excel in all positions, “oops’s” are expected.

4. the fun factor.

All young people love to play, and to explore. Thus, it is hardly surprising that learning skills in the context of an exhilarating game-practice (see above) rather than in a gruelling closely-monitored drill session is bound to be more fun by comparison. As well, even more fun can be added by engaging the players in the process of designing training sessions, setting up a season plan, or deciding who is captain. This meeting approach also offers more opportunities for genuine bonds to be formed between the coach and the players, as it is evident that the coach cares for them as individuals, rather than primarily focused on winning games.

Ultimately, though, how important the fun factor in soccer coaching is depends on the goal. If the goal is to imbue youngsters with a love of the sport, with the love of physical exercise, and with the love of engaging in a cooperative enterprise, then the fun factor is critical in maintaining youngsters’ enthusiasm to consistently come to practice and games, despite their busy schedules. It is of note that more than 70% of young athletes quit sport at approximately 14, with many citing lack of fun as a reason (Merkel, 2013).

5. evaluation of the effectiveness.

Evaluation of effectiveness for a meeting-coach is focused primarily on individual growth rather than on team success. Thus, if it becomes evident that a player is having difficulty recognizing when to dribble as opposed to when to pass because her head is constantly down, if, after discussion, she improves, that would be a win. As well, retention of players is also an important measure of success.

On the level of the season as a whole, evaluation is usually done cooperatively between the coach and the players through before and after video analysis, as well as discussions about the ways in which, over the season, individuals and the team have improved.

6. self-evaluation of the educator.

A meeting coach is constantly self-evaluating as he/she creates and re-creates varying contexts with the hope of eliciting the best out of each player, as well as the team as a whole. Was the context successful in eliciting the intended skill practice? Was there evidence of improvement or increased insight? Was it fun, both for the players and the coach? During games, is there evidence of improvement in cooperation? Are the games themselves fun, regardless of the outcome? Do the players show grace whether they win of lose? And ultimately, at least for this educator, the smile factor in practice and in games is the biggest reward.

ensuring that p4c is, in fact, non-hierarchical

Clearly Philosophy for/with Children (P4C), anchored in its pedagogical center by the community of philosophical inquiry (CPI), is meant to be a non-hierarchical educative enterprise. The very point of creating a CPI is to solicit agent responses and to focus on process that may lead to an unanticipated result. On the other hand, the very success of P4C may lead to an intimidating top-down message (similar to the math mantra) that there is a correct and incorrect way of doing a CPI, and that facilitators had better beware.

That there are correct and incorrect ways to facilitate a CPI is not an unimportant message, particularly with regard to incorrect ways of facilitating that might shut down agent responses, or that focus on the result rather than the process. A facilitator implicitly or explicitly leading the group toward a specific conclusion, e.g., that bullying is wrong, can do more harm than good by trying to fake “meeting.” And certainly facilitators can learn a lot about how to successfully run a CPI, both theoretically and practically, from those who have gone before. Having said that, though, there is nonetheless a case to be made for loosening the grip of a model that may be becoming overly fixated on the assumption that there is a “best way” to run a CPI. Such a message inevitably shuts down the agent responses of budding facilitators, and hence the possibility of their unique contributions both to the inquiries of which they are a part, as well as to the model itself.

One way to loosen the grip of this top down messaging is to reenergize the importance of the “fun factor”-something that requires ingenuity outside of the sort of sustained communal interaction that is afforded by camps, teams, and even conferences. One way to do this is to tackle topics that are uncomfortably close the lived lives of the participants. There can be huge exhilaration in wading into issues that participants tend to view as verboten.

The “oops” factor ought also to be embraced. Worldwide P4C successes, and much of the literature suggests that just creating a community for inquiry, and doing very little else but gate-keeping, will result in success. This is not the case. As in all non-hierarchical educative encounters, the ingenuity of the context will ultimately determine if genuine inquiry is the outcome. That context includes the facilitator’s demeanor, the facilitator’s relationship with the participants, the ingenuity by which the question for inquiry is decided, the degree to which participants perceive that this question is sufficiently relevant and important to justify the hard work of communal enquiry, and so on. Given all the “i’s” that need to be dotted for success to result, all facilitators ought to be warned that the CPI can flop, and flop utterly, and that therefore, having an escape hatch, such as an alternate question in mind is always a good idea.

All in all, though, we suggest that, as with other non-hierarchical educative enterprises, P4C facilitators ought to ask themselves the following questions before embarking on what hopefully will be a wondrous journey.

Will the context solicit agent-relevant responses?

Will it focus on the process rather than the result?

Will it offer “oops” opportunities, both for participants and facilitators?

Will the encounter be fun?

Is there an insightful way to evaluate effectiveness?

Is there an insightful way for the educator to evaluate herself?

conclusion

In her article, “What Would Socrates say to Mrs. Smith?” Gardner (2011) makes an impassioned plea to parents to avoid, on the one hand, the stifling effects of authoritarian parenting, while on the other, avoid the absentee but friend-like parenting of anything goes.

This, in essence, is the case that is being made here for all adult-child interactions, namely, that it is the adult’s responsibility to bring the wealth of all of her experience, knowledge and imagination to the task of creating a myriad of contexts that will effectively solicit personal responses from youngsters that, absent an implicit agenda, may very well solicit utterly unique ways of being in the world.

This suggestion closely mirrors Kohan’s position (2011) when he says:

Rather, we work to establish a context for thinking, and a pedagogical relationship in which the student realises that the teacher does not want to transfer, bestow, or engineer the appearance of anything to or in the student, but is confident in the potential of her thinking, and in her capacity to share a thinking process with others. (p. 352)

Our position, though, is somewhat at odds with Kohan (2011) when he says that “We do not know and we do not want to know or anticipate what a student may be learning” (p. 352). By contrast, we believe that it is essential that, in creating contexts, adults have particular goals in mind; goals such as helping youngsters to become confident in thinking through what might be the appropriate responses to such important topics as animal extinction; Or goals in soccer such as being able to confidently play one-on-one against an opponent or dribbling in a high-stakes environment. It is precisely by having such goals in mind that educators have some criteria whereby the educative process can be evaluated. This sub-point, in turn, reinforces the central message of the argument being presented here, namely, that simply adopting the appearance of a non-hierarchical educative strategy does not, in of itself, make the case that this approach is superior to the more traditional top-down models. The onus lies with non-hierarchical educators to demonstrate that their approach is superior precisely because it avoids the often invisible disadvantages of a top-down model. We offer such a demonstration here.