improvising inquiry in the community: the teacher’s profile2

What does talk of improvisation have to do with inquiry? The link lies in that improvising like philosophizing, satisfies an appetite for discovery and creativity that is a natural part of being human. It is connected to the intimate desire to create and generate and discover the sense and meaning in what surrounds us; and it invites us to become completely involved in the act of making (Bailey, 1992). Whether we use a noun-product (improvisation), a verb-process (to improvise), or an adjective-procedure (improvising), we are speaking of a very complex concept.

There is arguably also another more ‘institutional’ reason for sustaining the relevance of reflecting on this concept, and that because contemporary society is characterized by uncertainty and the need to be open to change, to unforeseen events. The Introduction to the White Paper “A new impetus for European Youth” (EU, 2001) makes the point that, despite today’s more complex social and economic context, everyone - especially the young - must learn to be flexible, creative, a participant in their own life, and in society. Educational institutions are thus assigned a new educational mission that goes beyond knowledge transmission and the learning process. Their mission embraces both the learning process and the life skills needed to be in the world. Schools, in particular, have a duty to provide pupils with an education that will enable them to adapt to an increasingly diversified and complex environment, in which creativity, the ability to innovate, entrepreneurship and a commitment to continued learning are just as important as knowledge of a specific subject (EU, 2008). The European Union also asks schools and teachers to serve as an example and model of these competences: they should be creative, dynamic, open to change, cooperation and partnership, constantly capable of identifying opportunities for innovation and improvement. From this perspective, improvisation can be a very significant and inspiring phenomenon to explore (McKnight, Scruggs, 2008; Santi, 2010; Sawyer, 2011), and it may be useful to rethink the teacher’s profile to deal with their contemporary educational mission.

Improvising is a process that involves being in a relationship, confronting the unknown, the unexpected, the unplanned. This process invites us to explore, seek, dare and provoke because the outcome is originating (Santi, 2017) co-constructed, enriching for all concerned. To reflect further on what brings together improvisation and inquiry, however, we must first remove from the equation certain misunderstandings stemming from how the terms are frequently used to mean everything from the commonly-held idea that improvisation is a spontaneous and naive behavior to its consideration as one of the highest forms of technical expertise.

When we talk about improvisation in the pedagogical-educational field, we mean expert improvisation, rooted in knowledge, technique, preparation, experience (Hall, 1992) - a form of tacit, embedded, technical knowledge (Johnson-Laird, 2002; Ingold, 2007; Santi, 2010). Improvising in this sphere is not just about the extemporaneous aspects of improvisation processes (such as interpretations or variations), although it is important to recognize this spontaneous element. It is also a fundamental aspect of the educational relationship, when at least two different othernesses meet authentically each other (Zorzi, Camedda, Santi, 2019).

Improving oscillates between technique and spontaneity (Santi, 2010), embracing this oscillation between the known and the unknown. It does not stop at the evanescence of the extemporaneous, while it retains its own features. Improvising is a generative action process born of the relationship that develops in the here and now, as a form of exploration, research, and discovery.

Improvisation takes shape in a set of emerging actions, based on a high level of readiness that enables us to grasp whatever happens, a kind of conscious alertness (Sparti, 2005). This "readiness" is not just a "disposition": we have to be willing to grasp the extemporaneous, but in order to improvise we need to say "yes", opening up to the action (Lipman, Gazzard, 1988; Tomlinson, 1995; Barrett, 2012).

Because it is a process generated in a relationship, improvisation necessarily involves a plurality of individuals, voices, actions, and thoughts. It relies on all participants adopting attitudes and dispositions that make them welcoming towards what happens.

How is this discourse on improvisation, and a disposition to improvise in the community related to inquiry? What kind of reasoning can be developed? This paper aims to reflect on two different perspectives: the feasibility of improvising inquiry in the community; and the intrinsic improvisational dimension of inquiry that takes shape in philosophical dialogue in the community.

To develop these two educational and formative perspectives, participants - students and particularly teachers - must first acquire a “readiness” for improvisation which is a sort of complex attitude. Teachers who improvise suddenly open a window on events happening in the community, serving as an example for the class, which is invited to do the same.

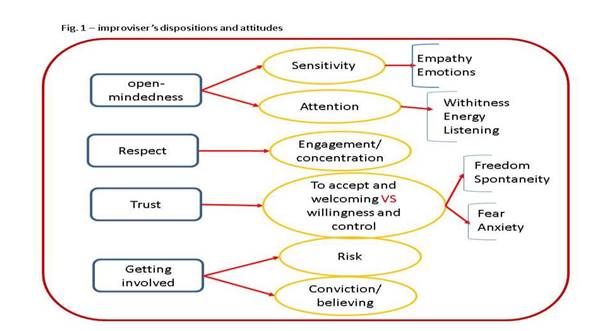

To be able to improvise, participants must have a complex and specific kind of disposition, which can be represented as in Figure 1, and described as follows3: a constantly open mind that is able to grasp what happens immediately; a profound respect for, and engagement in what is happening; a trust in the ability of the process, others and oneself to explore and provoke; a personal involvement and willingness to risk taking new paths, accepting change, because everyone is interested in developing and improving the discovery process, and the quality of the improvisation (Bailey, 1992).

Open-mindedness:(which includes sensitivity, attention).As Barrett said (2010), if improvising involves wading into the unknown with no guarantee of outcome, abandoning well-learned routines and habits, the activity seems perilous. Improvisers employ a positive mindset to create spontaneous utterances when conditions are very unclear. They assume that every utterance, no matter how challenging or difficult, can lead in a positive direction. Noticing the opportunities rather than the obstacles to be faced demands an affirmative mindset, and the assumption that there is a latent, positive chance of being noticed and valued. Improvisers are sensitive to contexts, participants, and needs. They are empathetic because they catch other people’s emotions and difficulties. Improvising demands that participants be not only aware of what happens in the process, but also - and more importantly, that they be there, in the present, within the extemporaneous process (Kounin, 1977; Sousa, Tomlinson, 2011). Improvisers can listen and be receptive without being intrusive. They can fade out, withdrawing their support and intervention when there is no need for them.

Keep your eyes open, don’t get lost inside your head. Look for opportunities to support your partner, move in underneath them. Don’t give or take weight without listening for the agreement of your partner’s body. Let each move evolve from mutual agreement, rather than having an image in your mind dictate what happens next. Mutual trust is based on uncompromised attention, so stay in the present moment. (Curtis, 2003; p.15).

Respect: (which involves engagement and concentration). Respect for improvisation means being able to validate the activity and the process, even if they are extemporaneous. Improvisers attribute dignity and value to what they do, and to the immediate results, and this requires engagement and concentration. Respecting what is becoming involved in an improvisation process, in all its facets, is an essential attitude to ensure that improvisation is awarded dignity and value it deserves. This demands concentration and engagement on the part of participants, so that stories and meanings can breathe and find their way (Formenti, 2006), because they are not thought of or decided before the process is underway.

Trust (which involves being able to accept what happens and, most of all, to accept that responsibility for what happens is not individual, but collective, shared by the community). Improvisers need to trust the process, abandoning any effort to control the paths and decide the results. Participants trust what they are, their preparation and ability, but they trust the process at the same time. Instead of trying to play the music all the time, you sometimes have to let it play you, and you need to be relaxed enough to let it happen. Gaining the confidence to do this can be an important turning point in an improviser’s learning curve (Berliner, 1994; p.219). This trust has to do with the fundamental capacity to welcome and accept what happens, staying in the process. It means being open to the moment and letting it happen, trusting that something good will come of it, even if it is impossible to foresee and to fully control. Trust also involves sharing responsibility with other participants, and this shared responsibility can rid everyone of their anxiety about making mistakes, making them more and more spontaneous.

Getting involved(which involves risk-taking, conviction, believing). Improvisation demands that people get involved, discovering themselves in the process, offering the best and utmost of themselves. Getting involved also means taking a risk, learning not to be defensive, and such collective risk-taking and discovering generates a strong cohesion among participants. They can encounter mistakes, face them together, and reveal their authentic selves, strong in the conviction that the process will lead their shared reasoning in new directions. Risks are an inherent feature of improvisation (as in the educational relationship): wherever there is improvisation, there are risks because its unknown elements bring with them a certain amount of unpredictability. During the process, it is essential to be convinced that there are no recipes for a good-quality improvisation, no right things and wrong things to do, no certainties to offer or receive. Improvisers simply have to be convinced about themselves at all times (Braida, 2006).

Knowing how to improvise means to get involved in a moment because that moment, which captures the unrepeatable instant of the creation of an attitude, questions a qualitative interpretation of time, in which the improvisational moment is experienced as an opportunity, as a revelation of the sense of an existential situation. (Serra, 2006, p. 81).

By nurturing this complex disposition, participants develop a kind of awkward inquiry that enables them to go looking for accidents, for “oddities”, because it is in these strangenesses that they can arrive at the active listening that real knowledge requires (Formenti, 2006; Sclavi, 2003). In improvisation, listening is more important than being in a pre-view, and sensitivity and trust are fundamentally more important than the person’s will. Improvisers have to get closer and closer to the necessary “emptiness” to make the best of every opportunity for generating meaning and possibility (Cappa, 2006). When a lot of will or preparation goes into the immediate action, then interaction with what happens is no longer unforeseen. It becomes planned, calculated, and this means that participants are not present and alert within the educational relationship (Alterhaug, 2010).

Having delineated the type of disposition needed to grasp when there is an opportunity , we can go on to reflect on the dual perspective of the relationship between improvising and inquiry.

improvising inquiry in the community

Focusing on the verb “to improvise” leads us to consider how every educational or formative moment can hide an improvisational window that can be transformed into an opportunity for inquiry, in the sense of a deeper investigation, knowledge co-construction, discussion and negotiation of meanings. Improvising inquiry means welcoming the chance for the research to have an extemporaneous aspect, serving as a starting point. Then the research may lead, and be led in unexpected and unplanned directions, and towards horizons that are not necessarily resolute, clear, solved. To take such a perspective, the community needs to be familiar with this practice, and to have an inquiring and improvising habitus (Bourdieu, 1992). It is a way of looking at the unforeseen that implies the ability to decide on the spot that something warrants collective thinking, that an unscheduled suggestion deserves to be the focus of an inquiry, to be investigated, explored, discussed, and further clarified.

To pave the way to improvising inquiry in the classroom, the teacher must be able to plan lessons or teaching units that can make room for the unforeseen. Such an approach involves using laboratories, discussions, group activities, in which a minimal structure assures participants the utmost freedom (Barrett, 2010), even to propose “oddities” as the starting point of their research. All these activities can also make it possible to promote occasions for participation and emancipation by leaving “empty” spaces, that can be sounded and filled by students’ thoughts or questions.

Teachers taking this perspective become capable directors and designers. When an opportunity arises, they are willing to accept it and ready to transform it - together with the community - giving new meaning and scope to a spontaneous occurrence. They are teachers who focus the teaching-learning processes around enabling philosophical inquiry to happen even in an unforeseen way. They construct a shared, collective thinking that is also reflective, significant and connected. Improvising inquiry in the community means collectively and gradually developing the capability to give meaning and value to what happens in the here and now, and maybe also to the “impromptu” itself. “What is the meaning of this utterance?” “What value can we attribute to what is happening?” “Can we connect this opportunity to what we know or what we are exploring?” Improvisation is a process in which participants are asked to connect what is happening with what has gone before and/or with what will follow, to find a sense, lend a value to the whole. Inflexibility prevents improvisational processes from developing and becoming an attitude and disposition spreading through the whole community, so flexibility needs to be nurtured to enable improvising inquiry in the classroom.

improvising inquiry in the community

The other dimension of this reflection turns to improvising as a feature of inquiry in the community, where “improvising” is meant as an adjective describing the research effort. An improvising inquiry is a type of research that wanders along, without necessarily knowing in advance where it is heading. Its improvisational nature lends value to aspects relating to opportunities and openings - something to which Philosophy for Children (P4C) has always given priority in community philosophical inquiry. Any discussion can stem from a specific solicitation or text4, or it can develop, become clear, unravel and become entangled around new suggestions and questions emerging from the discussion itself. This improvisational opening is intrinsic in the P4C way of promoting inquiry in the community. Different perspectives, interpretations and reasonings are accepted, received and relaunched, with a good chance of deconstructing what the facilitator had “prepared”, or “previously thought”. This improvising aspect of research has to be explained and sustained during a facilitator’s training, so that everyone can be aware and ready for it when it is expressed within the dialogue.

Recognizing, interpreting and promoting the improvisational perspective in community philosophical inquiry help to protect its dialogical and democratic nature by opposing the need to obtain preconceived results (Echeverria, Hannam, 2017). Improvisation intrinsically defends that aspect of creative and functioning serendipity (Gould, Vrba, 1982; Testa, 2010) which is sometimes fundamental to discoveries and explorations, relating to being ready and willing to discover the unforeseen and the unexpected, to grasp what happens and see potential openings, even if they are not immediate solutions to some issue. We need to be capable of acting, exploring and provoking, pushing our reasoning in unknown, absurd, unconventional, imaginary directions, letting even apparently meaningless and pointless variations happen. Fostering creativity in inquiry (Santi, 2017) means more than just promoting “innovation”. Creativity has less to do with what is original, and more to do with what is originating, emerging from an authentic generativity (Ingold, 2014). It is a human expression of a disposition to wonder and to respond to novelty.

An important consequence of being open to new ideas is that a conclusion is never foregone or decided at the outset (Echeverria, Hannam, 2017). In other words, community philosophical inquiry has genuinely democratic educational purposes inasmuch as the precise outcomes are never predetermined, and this means the inquiry is intrinsically improvisational.

In community philosophical inquiry, the teacher is a co-inquirer (Echeverria, Hannam, 2017) and has particular responsibilities. At the start, at least, the teacher demonstrates how to keep the inquiry space as a place where every participant becomes interested in others who differ from themselves. It is a place where attention and listening are directed not just towards what has already been thought, but especially towards what has yet to be invented, and can only be imagined precisely during the research. Through a discussion consisting of full and empty spaces, facilitators become improvisers, aware and sensitive, who merge elements of a jazz-pedagogy (Santi, 2017; 2016a; 2016b) with roles that they fashion during the inquiry. In particular:

- facilitators need to be provocative within the inquiry, encouraging participants to go deeper into the proposed hypotheses, even countering them or offering new suggestions and perspectives; they help participants to retain an inquiring disposition during the discussion; they embody the jazzing (enlivening) dimension. Improvising philosophy with children means surrounding the experience of thinking with the vitality and animation of childhood, and always with an enthusiastically shared enjoyment. Jazzing also conveys the idea of creatively playing around, chaotically rearranging or harmoniously disrupting (Barrett, 2010), which is exactly what transforms the activity of children’s thinking into philosophical reasoning. Jazzing is the attitude that seeks to create order in chaos, disorder in harmony, deviation from melody, travelling new paths;

- facilitators are liberators, sustaining the fusion of the free dimension of jazz with pedagogy and philosophizing; they promote experimentation outside the comfort zone of predictable success and the exploration of other spaces in a “safely creative environment” (Weinstein, 2016). Facilitators encourage participants to be free and spontaneous, to recognize mistakes as potential new paths to explore, while assuring the community that the inquiry space is a safe place to wander in;

- as promoters of communication, facilitators allow for the circularity of ideas and their justification; they are sensitive to the community atmosphere, they can touch and sustain the groove, working on fluidity and dynamics. A groove is a shared flow, and finding the groove means finding a shared direction, a mutual intention/intension “to be” rather than “to do” or “to have” - a sort of “weak” inten(t/s)ionality not oriented towards the retention of content, information, skills, or relationships, but driven primordially by participants’ attention. Finding the groove is a positive feeling. It involves listening with emotion, empathy and a caring attitude, and it accompanies the achievement of a shared satisfaction without softening the tension of the dialectic;

- as modulators, facilitators articulate the different phases of the process, fostering the cohesion of ideas and guiding the thinking in a generative direction; facilitators should sustain the merging of different positions, encourage active listening, and give the community feedback on their observations, always in a process of fusion, that implies: abandoning the desire for “purity” and opening up to contamination and promiscuity; and leaving the “comfort zone” to live in a carnival, a melting pot were the end product is more than the sum of its parts;

- serving as monitors in a discussion means checking that participants’ shared reasoning is appropriate and consistent, helping the community to explore the meaning of the whole. It means keeping a cool distance so that the experience remains open to a horizon of possibilities. Cool teachers are a light, or “weak” presence, distinctive not for what they add to the cumulative knowledge in the educational exchange, but for how they can interpret it, making room for understanding. Being cool demands a good dose of silence, just as teaching demands a good dose of ignorance (Kohan, Santi, Wozniak, 2017) when philosophizing with children;

- as scaffold-builders, facilitators sustain the community temporarily and dynamically, providing the conditions for mutually supporting the cognitive, creative and caring operations involved in the inquiry and the collaborative process; they swing between being there and fading out. The dynamics of coming and going belong to jazz and philosophical dialogue, and they are essentially playful and full of fun;

- as care-givers, facilitators look after the community’s environment and comfort zone; it is fundamentally important in community philosophical inquiry for all thinking, be it convergent, divergent, alternative, or absurd, to be welcome in the shared reasoning. A caring attitude allows participants to trust themselves, the process and the facilitator. Soul philosophizing expresses the spiritual nature of intimacy in playing together. It is not a concept or an idea, but rather an insight and intuition, a common will to share authenticity;

- ultimately, facilitators cover and discover improvisers’ dispositions and attitudes as a whole. In order to improvise, individuals must be open to wonder, and a sense of wonder is the condition but also the aim of improvisation: wonder at what is happening in the world as a given, and wonder at what we are trying to achieve by inventing a possible world, even when it emerges all of a sudden, impromptu.

This improvisational nature of teaching and facilitating was clearly recognized by Lipman, who considers philosophical activity in the classroom like an artist painting freely on a canvas (Lipman, 1996). The freedom of philosophizing is guaranteed by the improvisational nature of dialogue and inquiry, which transforms the monologue of traditional teaching into an ex improvise polyphony that emerges unplanned, and does not contain the direction and meaning of the action in advance (Santi, 2017).

To develop or elicit different perspectives (to improvise inquiry in the community, and nurture improvising inquiry in the community), teachers need to embrace the complex dispositions and attitudes characteristic of the improviser outlined at the beginning of this article. This is not easy to achieve, and a good deal depends on a natural human inclination that not everyone possesses. At the beginning of a “facilitator’s life”, the structure and plan of a session is always strong and systematic, but - with experience - facilitators become more and more prepared to be unprepared, and become authentic improvisers. But there is something that facilitators cannot escape even in their first community philosophical inquiry, and that is the intrinsic improvising nature of research and dialogue. This dimension needs to be embraced, leaving a good deal of responsibility and control to the process and to the community. To take these approaches, teachers must facilitate learning processes, improvise, ignore the known, invent and explore routes and paths that philosophical inquiry and reasoning can shape even in their extemporaneous expression.

Being a teacher-cum-improvising-philosopher means composing a way of thinking in the moment, being sensitive to difference, and supporting it, and being a teacher in process. Teachers improvise not only in their ways of practicing philosophy with others, but also in their ways of being teachers (Kohan, Santi, Wozniak, 2017). Teachers who co-inquire with the community can foster an open-minded, respectful, trusting and committed disposition that contaminates the whole of a community’s complex thinking.

So, why not start from the beginning, with just a first step, leaving the rein, trusting the improvising inquiry process, and the community? Why not think of ourselves, from the beginning, as “ignorant” facilitators who can explain the sense of wonder we feel when faced with the unknown, inviting the community to embark on a wandering and improvising inquiry?