disrupting both ‘eye’ and ‘i’ in ‘seeing’

In our paper we disrupt both the human ‘eye’ and ‘I’ in ‘seeing’ when observing children in early childhood educational research. Educators are trained to regard preschools as places of learning for human development and achievement. Educational relationality is theorised as someone teaching somebody else in something, and that they learn it for the benefit of human purposes only. But fairly recently a paradigm shift has taken place, not only in education, but in fields as diverse as environmental humanities, the performative arts, cultural theory, organisational studies, critical geography, architecture, anthropology, political theory, literary and literacy studies, and childhood studies. In this paper, we explore the implications of the transdisciplinary disruption of human subjectivity - the so-called ‘ontological turn’ - and explore the implications for early childhood education. With its emphasis on a moving away from the dominant role of human vision (knowing and seeing) in educational research we explain how critical posthumanism makes us think differently in practice about knowledge and educational relationality (between humans as well as between humans and the more-than-human).

The philosophical shift in subjectivity builds on, and is entangled with, poststructuralism and phenomenology and, in this paper, we read diffractively through one another the theories of Finish architect Juhani Pallasmaa and feminist posthumanists Karen Barad and Rosi Braidotti. These theorists argue against the dominance of human vision - the eye - in determining what is real, and posthumanists also show the damaging effects of regarding the human body as an individualised human ‘I’ (e.g., with attributes, properties and an ‘inner’ and an ‘outer’). The natural and social sciences are built on this basic dualist structure of an ‘I’ (‘culture’) at an ontological distance from the world (‘nature’) they are perceiving with the human eye. Barad and Braidotti unsettle agency as not something subjects ‘have’ and invite us to reconfigure who and what the ‘I’ is, as well as its relationship with/in ‘the’ world.

We explore the implications of this recent philosophical shift for knowledge practices when joining preschool children on an outing to a park as part of a research project in inner-city Johannesburg. We engage posthuman(e)ly with how the videoing and photographing work as an apparatus in analysing the data. We are struck by children’s seeing with the ‘eyes of their skin’ (Pallasmaa) and ‘seeing’ with/in the world (posthumanism) as their obvious distress is felt when a small tree sapling has been mowed down. We analyse the event with the help of a variation on Deleuze’s notion of ‘becoming-child’: ‘becoming-little’, and Anna Tsing’s ‘the arts of noticing’. Being closer to the earth’s surface than ours, the eyes (and skins) of children are drawn to details that are trivial or unimportant to others. Tsing inspires us to ‘see’ what tends to be regarded as ‘trivial’, but in fact points at the ‘little’ things in encounters that matter when we are in touch with/in the world we are a part of and care for. ‘Becoming-little’ as a methodology disrupts the adult/child binary that positions ‘little’, younger humans as inferior to their ‘bigger’ fully human counterparts. We exemplify ‘becoming-little’ through 4 and 5 year-olds’ learning with the little tree and adopt Barad’s temporal diffraction to ‘see’ what is in/visible in the park: the extractive, exploitative, colonising mining practices of White settlers who are still part of the land on which the park was created and implicated in the current realities of the humans and ‘others’ who share it, but are in/visible beneath the ‘skin’ of the earth. We conclude that visual posthuman research practices are an important move towards early years education that is concerned about multispecies survival in the Anthropocene.

the dominance of human vision in deciding what is real

Diffracting is an affirmative methodology developed by Barad (2003, 2007, 2014, 2017) that sees theories as always entangled and porous, not distinct bodies of knowledge with distinct boundaries. This posthuman methodology and pedagogy offers creative opportunities to do justice to the theories and practices we inherit as researchers - as opposed to the dominant academic practice of ‘critique’ (Murris & Bozalek 2019). In a footnote, Barad (2014:187 ftn 63) explains that diffractive analysis and critique differ in their ontology and temporality: the latter (critique) “operating in a mode of disclosure, exposure and demystification” (destruction), while diffraction is “a form of affirmative engagement” creating new “patterns of understanding-becoming” (construction and deconstruction).

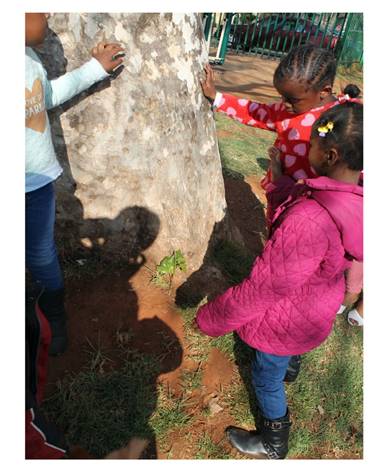

Phenomenologist Juhani Pallasmaa argues against the prevalent bias towards vision in the arts and architecture. The dominant visual mode works at the expense of the other senses and Pallasmaa controversially proposes that humans see by their skin. The tactile sense is ontologically prior to all the other senses, including vision. Drawing on Montagu, Pallasmaa (2005:11) claims that as humans we are literally in touch with the world through the sense of touch. Even the sense of sight puts us in indirect contact with our environment via the layer of skin that overlays the transparent cornea of the eye. His influential ideas on experiencing, designing and teaching architecture disrupt the dominance of human vision since Ancient Greek philosophy and science. Vision, visibility and ocular metaphors (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980) structure what humans have decided as real and counts as truth and certain knowledge (a metaphysics of ‘presence’). See, for example, Descartes’ (1968) proposition that knowledge should be ‘clear and distinct’. In contrast, Pallasmaa (2005:11) writes that “[t]ouch is the sensory mode that integrates our experience of the world with that of ourselves”. Not vision, he claims, but my body is the “navel of my world” and “remembers who I am and where I am located” (Pallasmaa, 2005:11).

Like Pallasmaa, Barad also argues against the dominance of human vision - the eye - in determining what is real, but also shows the damaging effects of regarding the human body as an individualised human ‘I’ (e.g., with attributes, properties and an ‘inner’ and an ‘outer’). The natural and social sciences are built on this basic dualist structure of an ‘I’ (‘culture’) at an ontological distance of the world (‘nature’) they are perceiving with the human eye. For Barad (2007:155) and from a quantum physicist point of view (so not using the human eye as a paradigm for knowing), there is an “inherent ambiguity of bodily boundaries”, so it is impossible to say that this or that has, or does not have, agency. This unsettling of agency as not something subjects ‘have’ invites us to reconfigure who and what the ‘I’ is, as well as its relationship to ‘the’ world. For Barad the production of bodily boundaries is not a matter of someone’s individual, subjective experiences, or about how we know the world, but the way the world is put together ontologically. Barad is not just making the point that it is an empirical fact that there are ‘clear boundaries’ only for the human eye (therefore subjective), and that this is not the case from a physical optics point of view. Matter, she claims, is an “active participant in the world’s becoming” (Barad, 2007:136). With ‘matter’, Barad (2014) does not mean inert, passive substances that need something else (e.g., electricity) to bring them alive or to have agency. She ruptures the animate/inanimate binary altogether. The distinction between the two is learned, and not given. Matter is not a thing, ‘in’ time and space, but it materialises and unfolds in different temporalities.

researching as worlding-with-technologies

For posthumanists, nature cannot be reduced to a mere object of human knowledge. Nature does not exist ‘out there’, passively, to be discovered by humans’ thinking about or experimenting on ‘it’. For Barad it is impossible to separate or isolate practices of knowing and being: “they are mutually implicated” (Barad, 2007:185). All knowledge-making practices, including the use of technological apparatuses such as photography and video are “material enactments that contribute to, and are a part of, the phenomenon we describe” (Barad, 2007:32). In other words, when recording and documenting our observations of children in early years research, we do not simply record objectively what is happening, because the distinction between objective and subjective is dissolved. Barad’s diffractive reading of queer theory and Niels Bohr’s quantum physics gives experimental evidence that subject and object are inseparable non-dualistic wholes. Knowledge is constructed through “direct material engagement with the world” and not by “standing at a distance and representing” the world (Barad, 2007:49). An educational researcher must perform in order to see; we learn to ‘see’ through the apparatuses that measure by doing not seeing (Barad, 2007:51). These performative practices are not only material, but also discursive and are always entangled with our figurations of child and childhood. And here, posthuman researchers in childhood studies (e.g., Lenz Taguchi, 2010; Murris, 2016; Giorza, 2018) have something new to offer the field of critical posthumanism, with the latter’s exclusive focus on the adult human and the more-than-human.

becoming human

Unlike phenomenologists, posthuman researchers are disrupting human-centred conceptualisations of the subject (anthropocentrism) and human exceptionalism: perspectives that locate knowledge, intelligence and meaning-making in the individualised subject, and in the human subject only. They see the dominant and historically implicated legacy of particular Humanist epistemologies as the source of all present struggles with respect to race, gender, class and the environmental problems characterising the controversially termed geological period of the Anthropocene in which we now live. Unlike some other strands of posthumanism (e.g., Object Orientated Ontology) critical posthumanists are not anti-human, nor do they reject humanist strivings for social justice, equity, and human rights, but they warn against essentialising the human at the expense of lesser, ‘subhuman’ others (e.g., black people, womxn) and the more-than-human (e.g., animals and matter). Hence, the ‘human’ is clearly a political category and the critical posthumanist project is to redefine the ‘human’ and its relation to life and the world. Rosi Braidotti (2013) explains how the mature, white, able-bodied, heterosexual man of humanism has been the yardstick in Western knowledge practices of what counts as “normal.” The ‘I’ is the root cause of structural exploitation, dehumanisation (of womxn, sexualised, racialised and naturalised ‘others’) and asymmetrical violence (Snaza and Weaver, 2015). The western ‘I’ - Man - as universal, essentialising signifier has created identity through difference, that is, the human/other (subhuman and nonhuman) dichotomy. Western metaphysics, reinforced by religious humanist mythology, has spawned an ontology and epistemology that move on binary logic, power relations of inequality and ‘otherising’ notions of identity. A posthuman ethics recognises the inseparability of western knowledge systems and the colonising, extractive and exploitative moves toward ‘progress’ and ‘development’.

In this paper, we propose that children are treated as members of the ‘subhuman’ category and excluded though discriminatory humanist practices. A concern about unjust discrimination should include how ‘natural’ child development is measured, with children at the lowest level of the patriarchal hierarchy. However, although the more recent decolonising agendas of the sciences and humanities are not silent about gender or race as categories of exclusion, yet within them, child (childism or ageism) is still invisible (Murris, 2013; 2016) - even for posthumanists (see, for example, the omission of childhood studies as a minoritarian academic subject in Braidotti, 2018). The identity prejudices involved in the concepts child, children, and childhood work in unexamined ways in all phases of education, even though for decades now, scholars in childhood studies and early childhood education have argued that the normative knowing subject is assumed to be of a particular age (i.e., adult). Children tend not to be listened to and taken seriously as knowers, because of their very being a child and therefore (it is claimed) being unable to make claims to knowledge (Murris, 2013). It is assumed they are (still) developing, innocent, fragile, immature, irrational, and so forth. Predominantly positioned as a knowledge consumer, not producer, child is denied epistemically on the basis of a certain ontology. Entangled connections have been made among colonialism, imperialism, the institutionalization of childhood, capitalist discourses of progression, and ‘natural’ development. Linear notions of progress and reason have colonized education through its curriculum construction that positions children as simple, concrete, immature thinkers who need age-appropriate interventions to mature into autonomous, rational, ‘fully human’ beings1.

Since Ancient Greece, Western education has been regarded as the formation of childhood, assuming the ‘natural’ and ‘normal’ development of child as becoming-adult. Diffracting through mainstream critical posthumanism with our foregrounding of age as category of exclusion, we can expose how particular ways of thinking about the human and relationality have shaped these unequal adult-child relationships. In what follows, we show through theorised practice (theory and practice are not separated in posthumanism) the difference critical posthumanism can make in ‘seeing’ children. Through an example from researching early years practice in a South African preschool setting, we argue for a reconfiguration of child-adult-more-than-human relationality. What is urgently needed for justice is a reconfiguration of subjectivity, a new ontological starting place for observing children in early years pedagogical and research settings.

learning as worlding in a park in inner-city johannesburg

There are many different ways of relating to the world, of which ‘human’ ways only constitute a small subset. Moreover, there are semiotic systems other than human language, which also help to transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries such as between the arts, and the natural and the social sciences. If the knowing subject is part of the world and not separate from it, the challenge is to find other, more tacit ways of experiencing the world that also account for more-than-human experiences, and also include Pallasmaa’s ‘eyes of the skin’ as method. As humans, we are of the world, with the world and not in the world (in the sense of bodies in Newtonian space and time containers); a mode of being-in-the-world akin to child’s playful form of life (Murris and Borcherds, 2019). This material-discursive ontological shift in subjectivity challenges educators to reimagine education as a human and more-than-human endeavour that dissolves the teacher/learner binary and instead proposes learning as a process of world-making (‘worlding’). Without absolute ‘insides’ or ‘outsides’ and having instead porous boundaries, teacher and learners participate in the always ongoing re/configuring of the world. Barad (2007: 91) explains that learning is not “about making facts but about making worlds, or rather, it is about making specific worldly configurations - not in the sense of making them up ex nihilo, or out of language, beliefs, or ideas, but in the sense of materially engaging as part of the world in giving it specific material form”. It involves playful experimentation (‘becoming-little’) by paying attention to how human and nonhuman bodies affect one’s own being as part of the world. Living without bodily boundaries opens up spaces for imaginative, speculative, philosophical enquiries that rupture, unsettle, animate, reverberate, enliven, reimagine and disrupt power producing adult/child binaries. The agency of both teacher and learner are characterised in terms of intensity, potentiality and flow and of a doing justice to the in/determinate agency of the material world in learning. So, what would this look like in practice? What does it mean to ‘see’ a child in educational research?

barad and the ‘skin’ of the earth

An a/r/tographic2 research project carried out with children in an inner city preschool in Johannesburg, South Africa, provides a story of learning-as-worlding and re-positions Life Skills (the third area of content that teachers are required to teach alongside literacy and numeracy in the early years or ‘Foundation Phase’ curriculum) as life-strategies for living together on a damaged planet. The research site is a small not-for-profit day care centre in an inner-city suburb of Johannesburg that was historically a designated ‘white’ area under Apartheid and since its establishment in the late 1800s, has always been a place of arrival for immigrants. In recent times it has become a diverse ‘pan-African’ community. A class of reception-year children with diverse languages and backgrounds, but predominantly from Indigenous South African and neighbouring African national communities, are co-researchers with their teacher and Theresa, co-author of this chapter. The research forms part of her doctoral dissertation, the focus of which was an investigation of children’s intra-active learning with their environment. The notion of the ‘environment as third teacher’ comes from Reggio Emilia and has been put to work in different ways. Ours is a posthumanist take on this concept (Murris, 2016) in which we position ourselves as humans (humanimals?) alongside and among the other living and non-living beings, objects and forces that co-create our realities.

An assemblage of “lifeways” (Tsing, 2015: 23) that connect children and trees makes visible new and more complex patterns of multi-species engagement that challenge accepted and progressive narratives that envisage schools and parks as enabling environments for ‘healthy’, ‘normal’, ‘appropriate development’, learning and ‘improvement’. The unilinear temporality applied in such notions is disrupted in our analysis of a visit to the nearby park as part of the research project.

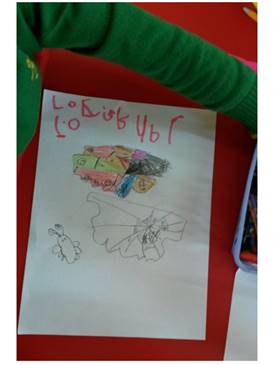

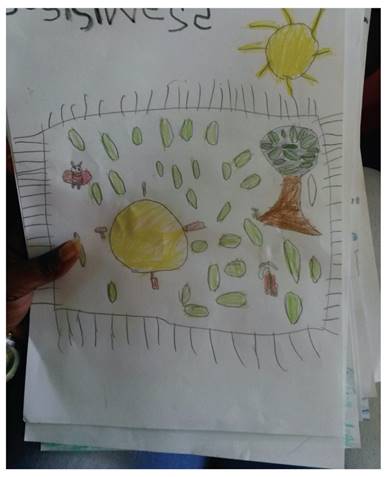

On the visit made to the park to find the new spring leaves, the Grade R group discovered a small tree sapling growing at the base of a large plane tree. The trope of babies and small creatures is strong for the children who immediately identified this tree as small like them and deserving of love and attention. “We love it!” they said. They wanted their picture taken with it and posed alongside it. The small tree appeared in a number of children’s drawings (see for example Figure 1). On a subsequent visit, we discovered that the small tree had been cut; mown down in the routine grass-cutting done by the park’s management. There was disappointment and sadness in the air. These are not simply ‘internal’ emotions the children ‘have’ individually and subjectively but are shared responses that flow energetically in between and amongst the company of children. They are a disruption of the close connection the children have with the little tree and its membership of the community of the park, the children, their drawings, the grass, the clover, the ants, the soil, that Theresa’s camera had recorded. They all have mutual distributed agency and are all active participants “in the world’s becoming”, materialising and unfolding in different temporalities (Barad, 2007: 136). The temporal dimension of this event we explore further below, but first we turn in our analysis to the politics of matters of scale.

The small tree is not a mere passive object of human knowledge, to be discovered by the children, talking and thinking about or experimenting on ‘it’. The children are part of the world - a natureculture reality they are moving through and are one with, ontologically. They are ‘seeing’ with the eyes of their skin, Pallasmaa (2005) would say and are affected by the violent removal of this small tree sapling. This park, while offering experiences of the organic and ecological (including creatures such as bees, ants, caterpillars and rats, see below), is managed and controlled as part of a system of city parks with particular notions of order, control, beauty and functionality, foregrounding certain stories and erasing others. The insistent colonial presence of the lawn has a long and vibrant history on the highveld (Cane, 2019). This space is not a food garden, nor is it a muti3garden; it is a recreational facility where the gymnastic equipment and running, rolling, somersault-inviting smoothness of an alien lawn variety co-constitute modern urban children-in-parks. Indigenous forms of clover creep in unannounced and unwelcome. Ants are too small to fence out and can go too deep to poison completely. The perfection of the colonial park is constantly, consistently, always, already un-made. It is in the in-between of the ‘tidying’ of the park by the local authority and the unruly nature of weeds, sproutings, messiness and disorder that a different rhythm emerges.

Grass, clover and ants. The ‘surface’ draws attention to the ‘underneath’ - entangled multiple temporalities.

The children posed for pictures with the truncated sapling as well. They expressed disappointment, and perhaps some (already) resignation, as they are not used to being included in decisions about things that matter in school or the wider community.

When diffracting through the images, a close connection is created and becomes visible in-between the children and the park although they have no part to play in the day-to-day up-keep or care of the space. Diffraction is an alternative to reflection, a metaphor which depicts sameness or mirroring (Barad, 2017, 2014). Reflection is an inner mental activity, where a researcher supposedly takes a step back, distancing herself from the data or whatever is being contemplated. Reflection assumes a dualist ontology between subject (self, culture etc.) and object (the world, nature etc.). In contrast, diffraction assumes a self that is positioned ontologically as part of the world: a relational ontology that takes relationality as its starting point, rather than individual units in space and time as the ‘furniture of the world’. Therefore, instead of looking for similarities and themes (which would assume that things are separately existing entities in the world that can be compared and contrasted), diffracting data involves considering human and nonhuman bodies as inseparable and entangled. Theresa was diffracting through the video, photographs and field notes and did not regard the data as ‘out there’, finished - as bounded units prior to the researcher engaging with it. She remains open to the surprises, the unexpected and the new produced (a diffraction pattern) through the “unpredictable encounters at the center of things” (Tsing, 2015: 20). Anna Tsing (2015: 20) wonders “What if precarity, indeterminacy, and what we imagine as trivial are the center of the systematicity we seek”? Precarity, she writes, “is the condition of being vulnerable to others. Unpredictable encounters transform us; we are not in control, even of ourselves” (Tsing, 2015: 20). If only without the “driving beat” of progress, we might notice the ‘little’ things and other “temporal patterns” (Tsing, 2015: 21).

It was only when the image of the little tree appeared repeatedly in the images generated by the children that Theresa began to see how much it mattered and how devastating its removal must have been. The removal of the small tree was one visible and painful effect of the exclusion of the children from the right to care for and make choices about their learning space. In figure 3.2 the artist has included an image of the person who sweeps the park. ‘People who help us’ is a theme covered in the Life Skills curriculum for Grade R, and here, the custodians of the park have been found wanting. The people who help us seem not to know us and what this ‘help’ might mean. The segregation of the classroom and the park excludes children from the life of the city. The park constructs them in particular ways. They are the child-playing or the child swing assemblage. They are part of the city and the community, but not regarded as fully citizens (yet). They are kept in the confines of schooling so that their presence in the materiality of the world is minimal.

Feminist philosophies of care4 and environmental notions of custodianship converged in new sproutings and diffractive shafts of meaning. Deleuzian ideas of thought as a multiplying and multi-directional rhizome rather than logically bifurcating branches led to new ways of considering pedagogy (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987). Pedagogy and the school separates children from their worlds and their relationships: something that Loris Malaguzzi’s metaphor of “the hundred languages” works to undermine (Rinaldi, 2006: 121). The work of the Reggio Emilia municipal system is part of a long established and ongoing political project in which issues of equality and direct democracy are at the centre of their conception of what education for their youngest citizens means. Their commitments to decentralisation and flexibility are not the privileged products of a financially stable local government but rather hard won and fiercely defended strategic, ethical and political choices about knowledge, and the cultural, social and political status of ‘child’ (Dahlberg and Moss, 2005: 137).

Barad invites us to consider that “(e)vents and things do not occupy particular positions in space and time; rather, space, time, and matter are iteratively produced and performed” (Barad, 2007: 393). The future already threaded through the now: parks are planned with a conception of citizen. The future of this park will be affected by all the possible presents and the possibilities for what will come to matter.

The children point out things, ask questions, and become much more physically animated while they are in the open space of the park: running, rolling, cartwheeling. They collect seeds and small objects that they take back to the classroom and sort and count and examine. Their close attention to and bodily connection with the ground draws Theresa’s attention to the surface of the ground and she photographs selections of ground surface. These images draw her in and her skin responds to the skin of the earth. What is on the surface suggests what is underneath. What is visible makes the invisible present, and what we can ‘see’ are entangled multiple temporalities. The ants that are able to burrow down into the earth below are part of that invisible reality, as are the beginnings of new shoots at the foot of the big tree. All the roots of the trees, the homes of the ants are important parts of this world of the park. If we went ‘deeper’, troubling matters of scale (Barad, 2007) we can pay attention to the extensive shafts and tunnels of the mining activity going on unseen to the human eye below.

violent his(s)tories of extraction

This city has its beginnings in the discovery of gold on a highveld farm in 1886. Within a year this highland plateau was turned into a swarming concentration of (colonising) human activity setting in motion reverberations across space and time. Global trade in minerals led modernist development and Johannesburg became a ‘boom town’. Parks were laid out for the purposes of re-creating a European lifestyle for the colonies established through a tentacular expansion of nineteenth century urbanism. The parks prevail although their shade and air sustain a new community. An incommensurability governs the troubled relationships between city parks and the park users. Modernist urban notions of how urban space should be used conflict with demands made by current realities and ‘stakeholders’. Informal taxi operators look for spaces and water sources for washing their taxis, homeless people look for places to sleep and spend their days. How are children expected to engage with parks? What kind of children are imagined in the design, creation and management of these spaces?

The (violent) His(s)tories of extraction and intrusion are there and not there at the same time, troubling a metaphysics as presence (through a different optics as explained above). This ‘optics’ is a diffractive one. Surface and concealment, substance and thought, the idea of being small and vulnerable carries meaning that is not only discursive, but also material. The visual meaning here resonates with experience; the experience of relative smallness, vulnerability and violence in the multispecies encounter. In an empathetic response to the tree, the children share their sense of the tree’s entangled subjectivity. Not human, but living, and like them, managed in a controlled setting with human purposes/agendas of ‘progress’, like their school has. Their place in school and the tree’s place in the park. Always at risk of being swept aside in the more important grand scheme of progress and development.

Barad invites us to consider that “(e)vents and things do not occupy particular positions in space and time; rather, space, time, and matter are iteratively produced and performed” (Barad, 2007: 393), expressed in her concept ‘spacetimemattering’. The future is always already threaded through the now: parks are planned with a conception of citizen. The future of this park will be affected by all the possible presents and the possibilities for what will come to matter.

After over a hundred years of colonial and Apartheid rule, South Africa became a democratic republic in 1994. Current migration patterns are due to disruptions of various kinds on the continent and elsewhere. Amongst those arriving in the country are people from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe and Somalia, all of which have witnessed decades of war and/or economic crisis. The inner city of Johannesburg is a gathering place for African migrants and refugees from more than twenty different countries many of whom have harrowing tales of hazardous journeys and divided families.

For the first time in the history of the planet, more than half of the world’s population now live in cities. In this city of migrants, both from other parts of South Africa and from further afield, we are experiencing this statistic. Of the twenty-seven children registered in the Grade R year, twelve have surnames and languages that connect them to countries other than South Africa. Increasing levels of inequality on a global and local scale are also a factor in this area - the levels of unemployment in inner city Johannesburg are way above the national average which is pegged around thirty percent. With an increased urban population come a population of urban children.

The histories of the inner-city spaces mentioned above focus on human histories. What of the geological realities beneath the surface of the ground? They are unseen but no less relevant to the story that is unfolding. They are entangled with the surface, the park, the trees and the humans. Johannesburg sits on a ridge formed by the impact of a meteorite that hit the earth over 2,000 million years ago. This collision liquidized the rock and earth at the centre of the impact, broke up the earth’s crust and tipped the Witwatersrand basin, which had held an inland sea and considerably rich ore-containing conglomerates. The circular ridge that formed around the point of impact folded the gold-bearing conglomerates deep into the earth’s surface - in some places, kilometres deep - protecting the gold from being washed away by erosion. The discovery and exploitation of this immense volume of gold followed the already established patterns of inequality and extractive accumulation operating in the worlds claimed by colonial empires. The carving up and sharing out of Africa by the European powers at the Berlin Treaty of 1885 was part of this system. Questions about access to land and resources remain unanswered in South Africa today even though our constitution upholds the right of every citizen to socio-economic provision. To look at children and their relation to a public park without paying attention to the wider entanglements that create this reality plays into dominant paradigms that leave these questions unasked. Open public spaces are valuable learning spaces for children, and for public expression of common ownership and care for a shared earth. A seemingly insignificant or ‘trivial’ incident involving a mower and a sapling invites an enquiry into the systems that govern the ‘commons’ in our city.

the video playing with time and space

Noticing and sensing rather than looking and seeing give credit to the ‘eyes’ of the body and the skin. Multimodal ‘pedagogical documentation’ is an intra-action that creates and re-creates our story with, among and in-between time, space and matter. Video plays with time and memory and allows the forward and backward re-working of events always producing new experience with each re-playing. Still images are cut from selected moments in the sequenced recording. Photoshop ‘handles’ the video clips, allowing us to move in and out, back and forth. Moments are selected, transformed into images and printed onto paper.

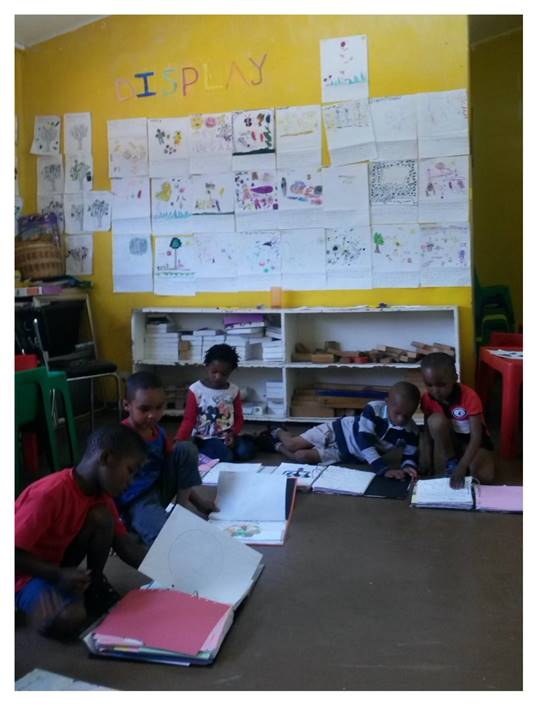

We follow concepts through the visual and through touching the tangible prints, re-membering the park, our visits, the trees, the big tree and small tree. The children work with images through looking, touching, feeling, filing in their portfolios, seeing with skin, hands, in relation. Seeing is acting in relation. Seeing is a ‘doing’ that has impact on the seer and the seen. Children, teacher, researcher are all co-researchers with and among the intra-connecting human and non-human worlding.

The concept of ‘becoming-little’ offers new possibilities for ‘seeing’ with/in the world. Becoming-little is a playful adaptation of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of ‘becoming-child’, which has little to do with age, or a particular subject, but more to do with a flux or intensity of the unbounded body that continuously affects and is affected. Walter Kohan explains that it is not the case that a given subject becomes a child or transforms herself into a child, nor is even childlike, but becoming-child escapes from the system, escapes from history: ‘a revolutionary space of transformation’ (Kohan, 2015: 57). In other words, the concept ‘child’ does not express an object in the world, but a particular experience of time, something all of us can have. The implicit goal of all Enlightenment ‘coming-of-age’ is autonomy, but with the disruption of the adult/child binary the decolonising conception of autonomy is beyond individuality, for “a singular, immanent life is no longer child or adult, but becoming-child” (Kennedy and Bahler, 2017: xiv).

The teacher becomes ‘smaller’, by giving up her control over the children’s files. The children manage their pedagogical products and live skin-to-skin with the growing record of their year in the class. This lively intra-action of spacetimemattering sets off new reverberations. The events in the park have produced a story of a little tree that may be misread as a charming and endearing allegory of childhood, but which has implications for how we carry on as humans in relation with our shared worlds. True stories of precarity and destruction haunt our every moment and demand a new ethics of engagement.

a reconfiguration of child-adult-more-than-human relationality

This research offers a set of practices for seeing differently and becoming-little. Trivial events and things, that may be overlooked in the purposeful business of everyday city living and dismissive notions of child, perform energetically in relation and as part of our intra-connected and changing worlds. They become more-than-visible in their tangible and somatic connection with an alert and haptically aware community of children and a camera-wielding maker/researcher. Efforts at maintaining an established order in inherited colonial systems produce new realities and layers of emergent practices, performativities and precarious economies. For Tsing, this is “third nature” (Tsing, 2015: viii). We cannot return to a pure nature (the idea that a nature existed prior to ‘culture’ and human intervention), nor to a pre-colonial nature in which the trope of industry and progress holds no sway. Everything (climates, water, and food) is affected by ever expanding and overlapping ripples of anthropogenic impact. Third nature then, is “what manages to live despite capitalism” (Tsing, 2015: viii). In the messy and unintended “offstage” realities of late capitalism new relations and emergent ecologies are becoming or can be noticed. Children meeting trees at the “unruly edges” (Tsing, 2015: 20) of a park management system draw attention to questions about care and response-ability.

Our diffractive reading through the data moves away from deficit notions of child development, disrupts psychologising tendencies to explain learning as something that happens (or does not happen) in the child as mental states, and does not use the western rational white adult as normative ideal of a ‘natural’ maturation process children are supposed to be scaffolded into through education. By reading the event in the park through multiple temporalities, the violent, colonising and extractive past of the land as always already entangled with child-teacher-bodies playing in the park is articulated. By disrupting nature/culture binaries the notion of agency has shifted ontologically to ageless transindividual agency that includes the more-than-human - a different intra-actional relationality and a non-human centred notion of performativity that is urgently needed in the Anthropocene.