1. introduction

For decades, philosophical dialogues with children have been included in well-established practices such as Philosophy for Children, P4C, community of inquiry and Philosophy with Children. While these practices have some differences regarding their origins, aims and approaches, they are united in engaging children in collaborative inquiries in emotionally safe environments to support critical and creative thinking. Proponents of Philosophy with Children have always advocated for and demonstrated children’s abilities to engage in philosophy as well as to think and voice their opinions (e.g. Martens, 1979; Lipman et al., 1980; Matthews, 1980; Jespersen, 1988), and theoretical and empirical research in the field has often included reports on children’s ideas on and contributions to philosophical dialogues. However, research on philosophical dialogues with children rarely examines children’s perceptions of what it is like to participate in a dialogue. Therefore, we suggest that children’s accounts and experiences should play a more important role in research.

philosophical dialogue in educational research on dialogic teaching

In recent years, Philosophy with Children has been attracting the interest of empirical researchers, with studies being performed on Philosophy with Children as such and on dialogic teaching approaches based on an intervention design inspired by facilitation techniques from Philosophy with Children. Among other things, the latter studies have examined the impact that such approaches have on classroom discourse. For instance, educational researchers have described how questioning and answering tools from philosophical dialogues with children can increase student participation and engagement (e.g. Reznitskaya & Glina, 2013; Wilkinson et al., 2017). Empirical research has resulted in new knowledge on the impact that Philosophy with Children has on children’s cognitive skills. Several studies with experimental designs have argued that Philosophy with Children improves children’s skills in mathematics, language and thinking in general (e.g. Topping & Trickey, 2007; Millett & Tapper, 2012, pp. 8-10; Fair et al., 2015; Säre et al., 2016; Worley & Worley, 2019).

In addition to quantitatively oriented impact studies on cognitive benefits, other studies have argued that philosophical dialogues with children can also benefit the participants’ personal and social skills. Some discussions of such benefits have been largely theoretical (e.g. Splitter & Sharp, 1995 pp. 202-204; Fisher, 2013, pp. 42-45; Sharp, 2007; Barrow, 2010) or anecdotal (e.g. Haynes, 2007; McCall, 2009, p. 175), but there are also empirical findings that suggest that community of inquiry methods can positively affect interpersonal relationship skills (e.g. Hedayati & Ghaedi, 2009; Millett & Tapper, 2012, pp. 10-12; Siddiqui et al., 2019) and can make children better at, for instance, team work and communication.

research on children’s experiences of philosophical dialogues

Compared to the increasing amount of empirical research on philosophical dialogues with children, relatively little attention has been paid to children’s experiences. Even major handbooks in the field lack chapters on children’s own voices and perspectives (e.g. Gregory et al., 2017; Naji & Hashim, 2017). This is a problem because children’s experiences are not just of instrumental value but are part of the raison d’etre of philosophical dialogues with children, which are meant to function as an appreciative and empowering practice (e.g. Lipman et al., 1980, pp. 8-9; Splitter & Sharp, 1995, pp. 118-119; Murris, 2008, p. 672; Lone, 2012b, pp. 20-21). Considering the prominent role that children’s thinking, voices and perspectives have in practice of Philosophy with Children, surprisingly little systematic research has been conducted to investigate children’s experiences of philosophical dialogues.

There is thus a need for more research on children’s perspectives. Educational research on dialogic teaching has resulted in knowledge on classroom dialogues, teacher behaviours and teacher beliefs (e.g. Nystrand, 1997; Alexander, 2018b; Reznitskaya & Wilkinson, 2015), and some researchers have studied school children’s behaviours (e.g. Segal et al., 2017; Lefstein et al., 2020), but few comprehensive studies have been carried out on children’s experiences of dialogic teaching (see, e.g., Crosskey & Vance, 2011; Reznitskaya & Glina, 2013; García-Carrión, 2015). Similarly, researchers have studied how philosophical dialogues impact children’s cognitive and other skills (as mentioned earlier), but relatively few have systematically investigated how children experience participation in philosophical dialogues and similar activities (Jackson, 1993; Reznitskaya & Glina, 2013; Barrow, 2015; Santos & Carvalho, 2017; Siddiqui et al., 2017). Studying children’s experiences is obviously important and is being increasingly encouraged in cultural studies research (see, e.g., Greene & Hogan, 2005; Greig et al., 2017), but this development has been less pronounced in educational studies on dialogic teaching and Philosophy with Children. Our study aims to address the need for children’s perspectives on philosophical dialogues.

our study of children’s experience of philosophical dialogues

To examine children’s perspectives, our study investigated 58 online dialogues. In the rest of the article, we first describe the study design: the dialogues and their setting, the survey that we used and our analysis of the answers. Then, we present our findings regarding the children’s perspectives before discussing the ways in which our findings are important for children, for philosophical dialogues with children and for future research.

2. materials, study design and analysis

The philosophical dialogues for school children examined in this study were organised in collaboration between the research project Philosophy in Schools (University of Southern Denmark), the organisation CoC Playful Minds (Billund, Denmark) and the National Institute of Public Health (University of Southern Denmark). The dialogues were conducted online via the communication platform Teams in February 2021, when schools in Denmark were closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Children from two schools (six classes in total) participated in five dialogues with their classmates each day for a week as part of the Billund Builds initiative 2021. Billund Builds is a week-long project with a common theme that takes place across Billund municipality’s schools and day care institutions each year. Schools signed up to participate in our week of philosophical dialogues after an open call, which means that our study’s population was based on convenience sampling. However, none of the classes had previous experiences with philosophical dialogues for children.

a week of online dialogues

We conducted 58 online dialogues, with each class receiving sessions with a new theme each day for five days. A total of 117 students from third to sixth grades participated in the dialogue sessions. Although the sessions had a different theme every day, all classes went through the same session on the same day. For the most part, the classroom was divided into two groups of approximately equal size for practical reasons. There were only a few occasions when, due to logistical difficulties or staff shortage, the dialogues were carried out with the entire class at the same time (i.e. without dividing the class in two). All dialogues were run by five experienced facilitators with certifications from the Philosophy in Schools project.

The dialogue theme was presented using a very brief narrative. The themes of the dialogues were inspired by the UN Sustainable Development Goals and were based on previously developed materials for physical dialogue settings (Schaffalitzky de Muckadell & Nielsen, 2021). The children were not informed about the purpose of the dialogues or the children’s own role. The dialogues simply started with with the facilitator saying something like “I’d like to start by telling you something” as a lead-up to the first question for discussion (for a similar approach to facilitation, see, e.g., Worley, 2011). For instance, the dialogue on Sustainable Development Goal 12 regarding responsible consumption began with questions of whether various kinds of food (such as strawberries in December, curled cucumbers, candy or insects) could be said to be “natural food items.” The children then shared their opinions, provided reasons, listened to one another and discussed various ideas in the ensuing facilitated dialogue. The dialogues were approximately 40 minutes each and were overseen by the students’ teachers and, in some cases, also by a project member who observed the dialogue. Both the observers and the teachers were instructed to have their cameras turned off and to refrain from intervening in the dialogue.

data collection via anonymous surveys

We collected the children’s perspectives using two kinds of anonymous surveys: a daily survey conducted immediately after each philosophical dialogue and an elaborate post-survey completed on Monday or Tuesday of the following week. The children were encouraged to participate in the survey, and time was allocated for its completion during school hours. Both surveys were designed as online questionnaires using SurveyXact by Ramboll for collecting quantitative and qualitative data. We designed the surveys to capture the children’s perspectives in various ways. We were interested in overall experiences and impressions as well as specific aspects, such as the children’s perceptions of the learning environment, their sense of participating in a community of inquiry and their views on sharing opinions.

Our surveys contained combinations of multiple-choice questions, open-ended questions and Likert-scale items with no neutral option. Two of the choices that we made regarding general survey design deserve special consideration. By choosing to employ a four-point Likert scale, we did not allow the children to respond neutrally about the dialogues. We chose this option because we wanted to prompt the children to form non-neutral opinions about the dialogues. It can be argued that the use of such forced opinion scales may distort the results because it forces the children to choose an option even when they do not have clear opinions. However, as neutral options would have allowed the children to move quickly through the survey without giving each question careful attention, we decided that the four-point scale was preferable. Second, we included many open-ended questions in the post-survey to allow for descriptions of the children’s complex experiences that could not be detected with the four-point Likert scale. This enabled us to achieve qualitative insights into the children’s experiences in their own words.

To report the results of our study, we translated the questions and responses from Danish into English. In some cases, we prioritised semantic equivalence over direct translation, aiming to capture the everyday language that we used in the survey. For instance, we used “fun” to translate “sjov,” even though “sjov” denotes a somewhat lower level of “excitedness” than “fun” does.

3. the children’s experiences

In educational research on dialogic teaching, scholars have described dialogical approaches as collective, reciprocal, supportive, cumulative and purposeful (Alexander, 2018b, p. 28). Dialogic teaching is expected to provide learning environments that support students’ speaking, listening and thinking as well as students’ ownership of the conversation (for an overview of the various approaches to dialogic pedagogy, see, e.g., Nystrand et al., 2003, pp. 138-139; Skidmore, 2016; Alexander, 2018a, pp. 562-563). Whether a learning environment is collective, reciprocal and supportive arguably depends, at least in part, on the environment being experienced as such. Therefore, participants’ behaviours can provide clues as to whether these quality criteria are being met, and reports on what it is like to participate in a dialogue are an important source of knowledge.

The following sections contain the results of our analyses of the daily and final surveys. We have organised our results into the following four categories, which also constitute the focal points of our study: (1) the children’s overall impressions, (2) the children’s experiences of meaning, (3) the children’s experiences of community and having a voice and (4) the children’s perceptions of the facilitators.

overall impressions and engagement

As our overarching aim was to gain insights into the children’s general impressions of what it was like to participate in the philosophical dialogues, the questions in the daily surveys and the post-survey were meant to address this focal point. First, we asked the children to choose three words to describe the dialogues. Then, we asked the children what they thought of the dialogues and whether they found each day’s dialogue fun and interesting and provided the children with the opportunity to describe, in their own words, what they liked and disliked about the dialogues. This section reports the main trends in the children’s answers regarding the questions on overall impressions.

three words to describe the dialogue

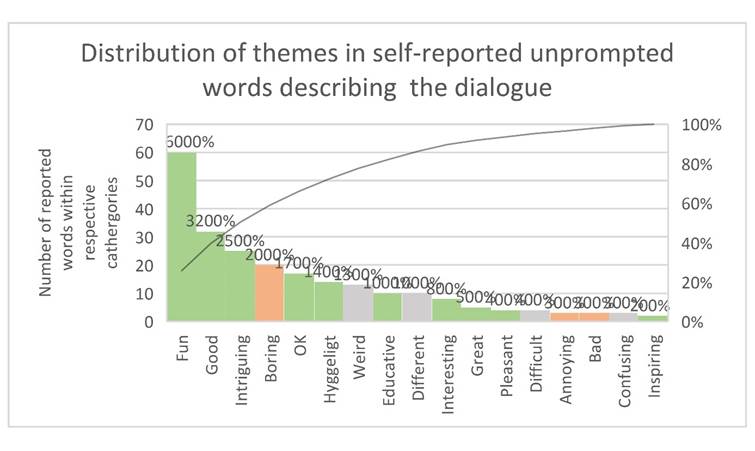

To get a sense of the children’s unprompted, general impressions of the philosophical dialogues, we asked the children to write three words to describe their experiences of the dialogues. Skipping the question was not an option due to the survey design. Eight children entered no text and were removed from the dataset (N = 8, 24 words), which left us with a total of 306 words from a total of 102 respondents. Figure 1 shows the distribution and the choice of words. Some children wrote the same word in more than one field (18 duplicated words in total); in such cases, we only counted the word once, which left us with 288 words. We also removed nine cases of unclear content (such as single-letter values or question marks) and semantically indefinable words (such as “nich”), which left us with a total of 279 unique answers from 99 unique respondents (n = 99).

The children also wrote words that did not describe their experiences of the dialogues, and we did not include them in Figure 1. For instance, we omitted seven words describing the contents of the dialogues (such as “Food, Artificial and Natural”) and sixteen words describing the dialogic teaching approach (such as “discussion,” “question” or “Make a choice”).

In our qualitative analysis of the words describing the children’s experiences, we grouped semantically corresponding words. For instance, the words “weird” and “strange” were grouped together. The qualitative groupings showed that many of the surveyed children had generally positive impressions of the philosophical dialogues: many children chose words such as “fun,” “good,” “hyggeligt” or “intriguing.” However, some chosen words were also explicitly negative descriptions, such as “boring,” “bad” or “annoying,” and some words were neither clearly positive nor negative (e.g. “weird,” “different” and “educative”). Certain words only occurred once and could not be grouped with similar words. Some of these words were exceptionally positive, such as “marvellous,” “imaginative,” “creative” and “game-like,” and a few the words were exceptionally negative, such as “pointless” and “performance anxiety.”

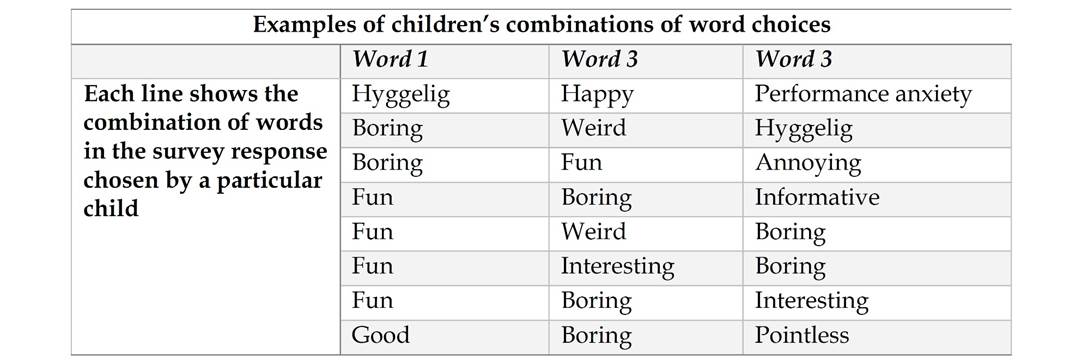

An interesting finding was that many of the children offered notable combinations of words. For instance, the child who chose the word “performance anxiety” also chose the words “hyggelig” and “happy” to describe the dialogues. While this may seem like a combination of semantically contradictory words, it may be the case that the combination, in fact, matches the child’s complex experience. Similar cases of notable combinations are shown in Table 1.

how did the children evaluate the dialogues?

The words the children chose to describe the philosophical dialogues corresponded with the satisfaction levels that they indicated in the post-survey question about their experiences. We asked the children the following question: “What do you think about what you did in the dialogue room?” We found that the children were generally quite happy with the philosophical dialogues. Of the respondents, 89 children (87.25%) stated that they had positive experiences with the dialogues (“very good” [26.47%] or “it’s fine” [60.78%]), and only 13 children (12.75%) reported dissatisfaction with the philosophical dialogues (“not so good” [11.76%] or “very bad” [0.98%]). This satisfaction distribution is similar to the findings of a previous study, in which students were asked whether they agreed that they had enjoyed engaging with philosophy in class (Jackson, 1993, p. 40).

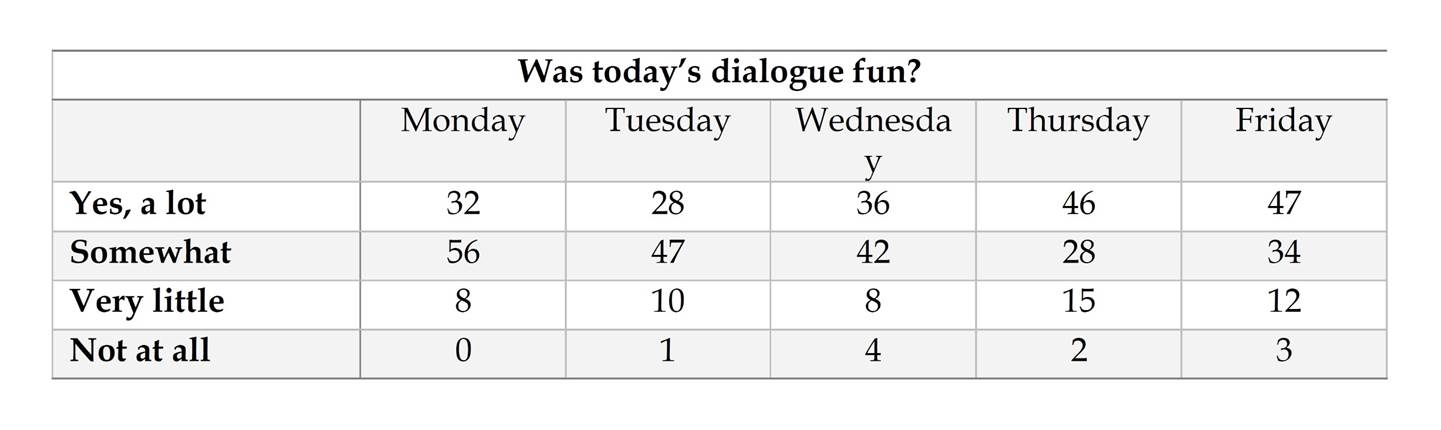

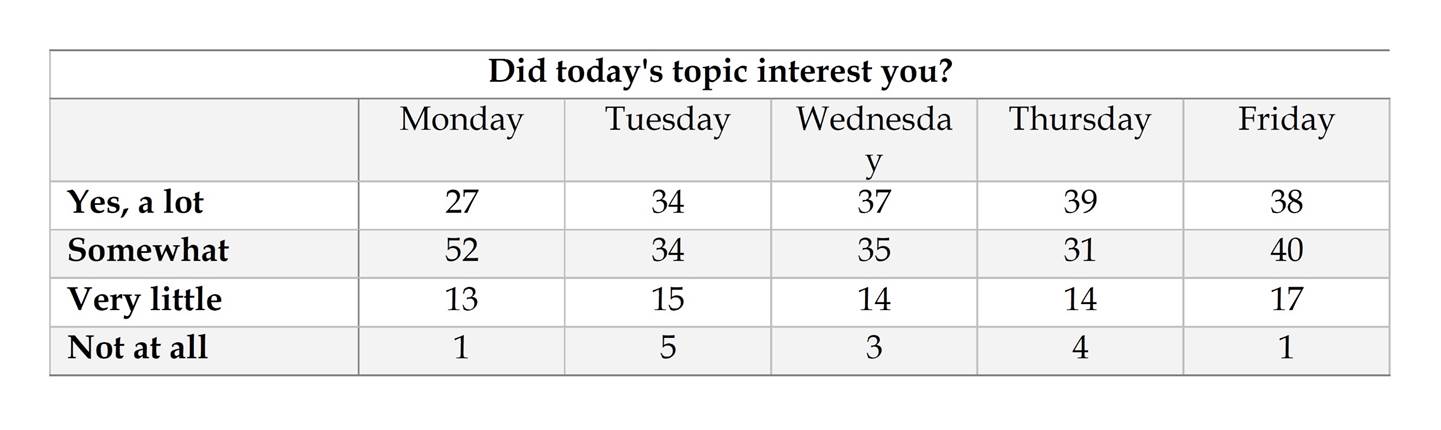

The level of satisfaction indicated in our study’s post-survey mirrors the answers in the daily surveys, in which we asked the children the following questions: “Was today’s dialogue fun?” and “Did today’s topic interest you?” We found that throughout the week, the vast majority of the children considered the dialogue very fun or somewhat fun (answering “Yes, a lot” or “Somewhat”). A small minority of the children indicated that they thought the dialogue was not fun (answering “Very little”) and a minor fraction indicated that the dialogue was not fun at all (answering “Not at all”) (see Table 2). The children’s responses to whether they found the topic of the day interesting matched their answers regarding fun (see Table 3).

what were the experiences that shaped the children’s answers?

While in the post-survey and the daily surveys the children mainly responded to the closed questions on a 4-point Likert scale, we also inquired about the children’s experiences via open-ended questions by asking them to complete the following sentence: “I think the best thing about the dialogue was that …” Many of the answers suggest that the children generally enjoyed the fact that everyone was given the opportunity to participate and speak their mind. Several respondents finished the sentence as follows: “[…] you did not have to answer something specific, you could choose for yourself”; “[…] you could speak your mind”; or “[…] we were allowed to say what we wanted to say.” Many children also liked the fact that there seemed to be no right answers to the questions: “[…] there were no right or wrong answers” or “[…] there was no single right answer.” Moreover, several children pointed out that they appreciated peer interaction and cooperation - for example, one child wrote that the best thing about the dialogue was that “[…] we could collaborate more than we usually do.” These experiences are similar to the findings of previous studies on experiences of sharing ideas in philosophical dialogues (Reznitskaya & Glina, 2013; Barrow, 2015; Siddiqui et al., 2017).

We also gave the children the opportunity to complete the sentence “I didn’t think it was fun to …” Some children stated that they were unhappy with having to “[…] talk all the time” or “[…] talk for so long.” Some children also replied that they did not like that “[…] they [the facilitators] kept coming up with the same question,” “[…] they asked the same question several times” or “[…] they asked about the same things all the time, but they just asked several times to get us to elaborate.” A child also criticised the fact that “[…] there was no single answer to the questions. I like when there is an answer.” Another child stated that “[…] the adults were absent.” These answers may reflect frustration with the slowness and the communal character of the dialogues and with the adults adopting the facilitator role instead of the traditional teacher role, which functions as an authority figure. Several children pointed out their frustrations with peer interactions, mentioning interruptions or the feeling of not being listened to: “[…] there were some who interrupted,” “[…] people did not listen” or “[…] we did not let each other speak out ... and just interrupted.” These experiences of boredom and problems with group participation are also similar to the findings of previous studies on experiences of philosophical dialogues (Reznitskaya & Glina, 2013; Siddiqui et al., 2017).

Finally, some children were unhappy with having to interact with one another via an online platform and noted that it was not fun that “[…] it was online” or that “[…] we just had to sit behind a screen and not be together.” Such negative experiences of online emergency teaching are consistent with previous findings (both in Denmark and around the world) on students’ school satisfaction during the pandemic (see, e.g., Qvortrup et al., 2020; Ewing & Cooper, 2021; Fiş Erümit, 2020).

perception of meaning

Another focal point in our study was whether the children perceived the philosophical dialogues as meaningful activities and, if so, what they considered the meaning to be. In the daily surveys, we asked the children whether they could make sense of each day’s dialogue and whether they felt that they had learnt something. In the post-survey, we were especially interested in whether the children thought that there were predefined answers that they had to find. This section reports the main trends in the children’s responses regarding these themes.

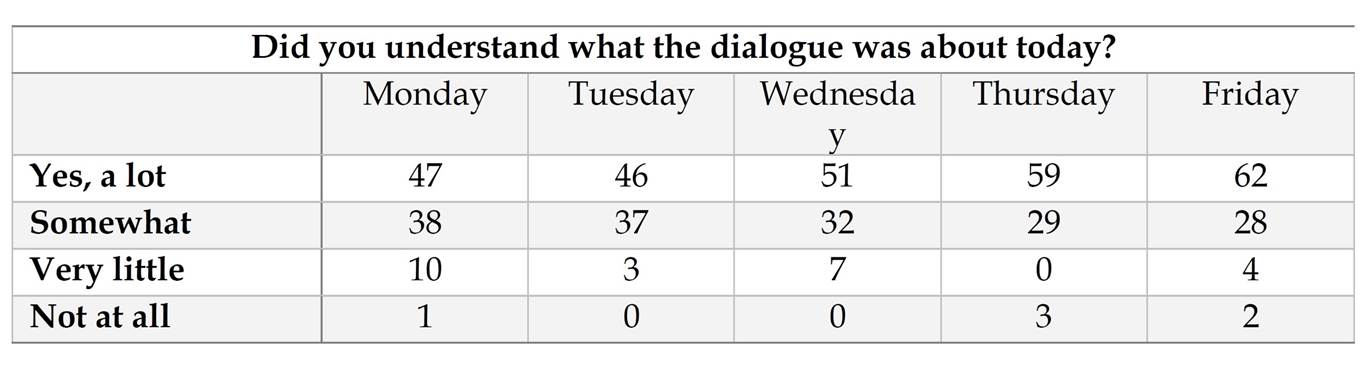

In the daily surveys, we asked the children the following question: “Did you understand what the dialogue was about today?” A very high percentage of the children answered that they did. Only a small proportion of the children replied that they did not understand what the dialogues were about, as illustrated in Table 4.

In addition to the quantitative question on the comprehension of the dialogues’ meaning, we asked the children to express their thoughts on the point of conducting the dialogue by completing the following sentence: “I think it was moastly about …”. The children’s qualitative answers revealed the general view that a key point was to collaborate and to discuss the dialogue themes: “[…] having a good conversation and that there could well be several different right answers,” “[…] to think, answer and listen,” “[…] to talk more together” or “[…] to cooperate and concentrate.” Some children believed that the point of the dialogues was the possibility to freely provide one’s opinion about the theme of the day: “[…] giving answers and not having them [the facilitators] give us an answer” or “[…] saying your opinion on things.” It should be restated here that the children were not given any instructions regarding the purpose of the dialogues or the importance of voicing their opinions.

A more specific point that we were interested in had to do with whether the children understood that the dialogues did not have predefined answers and that they were invited to share and provide reasons for their opinions without being corrected. To examine this point, we included the following trick question in the post-survey: “Do you think you found the right answers to the questions?” Instead of giving the children a closed yes/no option, we allowed for open-ended answers to the question by providing the children with a blank text field, as we hoped to capture potential non-standard or non-binary answers that would indicate whether some children understood that the “right answer” did not exist. It should be noted that we were not interested in answers such as “yes” og “no” to this question, as it would be impossible to determine why the children thought that they had found the “right” answer to the question.

It seemed that many of the children did, in fact, understand the premise of the dialogue, namely that there were no single “right” answers. Many children emphasised this by writing, for instance, “there are no right answers,” “Yes, but I was nevertheless in doubt because there were no right answers,” “I do not think there is a right answer to the questions” or “I do not think there were any right answers.” Some children even stated that opinions are closely involved in determining right or wrong answers: “I don’t think that there are any right answers. Everyone has different opinions”; “I think I found the right answers because that was my very own opinion”; or “I do not think there were any right or wrong answers, there are just different opinions.”

Therefore, the trick question revealed the children’s rather sophisticated understandings of the dialogues. After this question, we explicitly asked the children whether they thought that there were “right” answers: “Did you experience that you had to find a ‘right’ answer to the questions?” Again, the children had to answer in blank text fields; we coded the answers and removed a few answers with no clear meaning. A large majority of the children actually reported that they did not experience having to find specific “right” answers to the questions. A total of 56 children (58.33%) replied with variations of “no,” specifying, for instance, that “no, they thought that all answers were good :)”; “No, you just had to use your imagination sometimes”; or “no, you just had to say your opinion.” A total of 26 children (27.08%) replied with variations of “yes,” specifying, for instance, that “Yes, we had to constantly come up with more, and I got really confused in the end”; or “YES, and it was complicated to answer sometimes because a lot of questions were asked.” The remaining 14 children (14.58%) replied either “I don’t know” (n = 2, 2.08%) or “to a lesser extent” (n = 12, 12.5%).

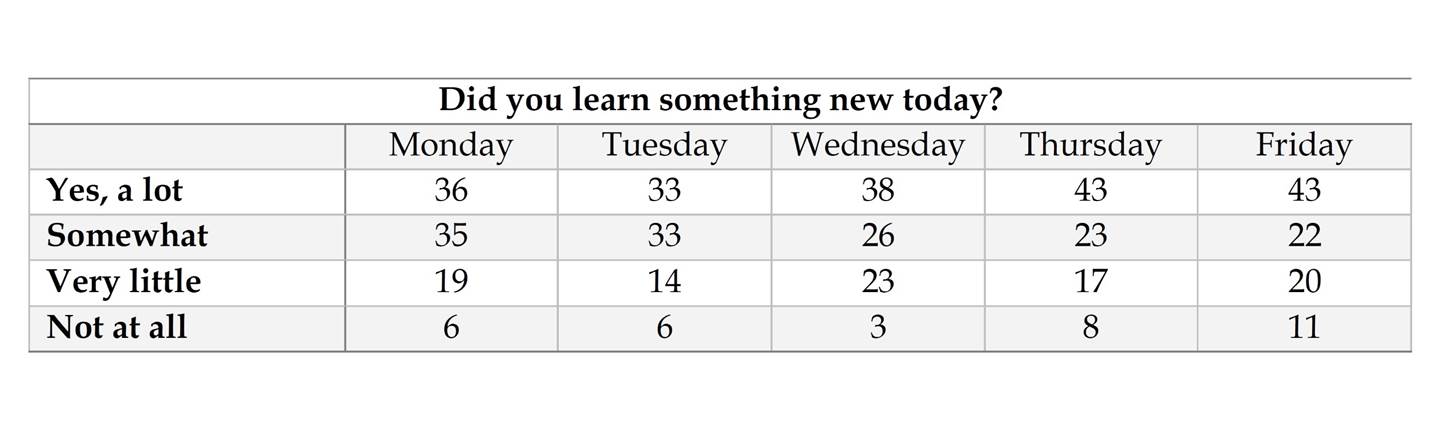

Not only did the children appear to understand the meaning and character of the dialogues, they also reported that they thought that they had learnt something new during the dialogues. In the daily surveys, we asked the children the following question: “Did you learn something new today?” The vast majority answered that they had, in fact, learnt something new (see Table 4).

sense of community and having a voice

The third focal point of our study was to examine the extent to which the children experienced being part of a supportive community during the philosophical dialogues and whether they felt they could share their thoughts and opinions. In the daily surveys, we asked the children if they felt that they could say what they wanted, how they felt about speaking, whether the others listened and whether they listened to the others. In the post-survey, we also invited the children to share if there was anything that they thought the group was good at.

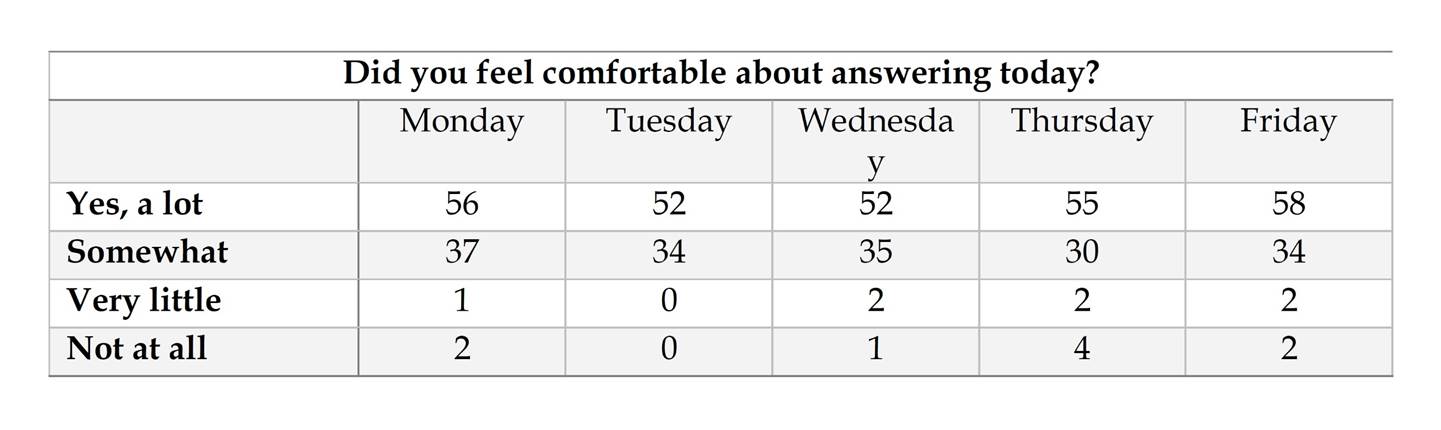

Traditional teaching often involves a strong focus on learning goals and teacher questions related to specific content, and it has been argued that this form of teaching can make school children worried about getting things wrong, which means that children “devise strategies to cope and ‘get by’ rather than engage” (Alexander, 2018b, p. 15; see also, e.g., Hargreaves, 2015; Galton, 2007, pp. 111-118). Philosophical dialogues and other kinds of dialogic teaching differ from traditional teaching in that the focus is not on providing correct answers but on creating a secure learning environment characterised by the collective process of exploring ideas. In our study, we asked the children the following question: “Did you feel comfortable about answering today?” Remarkably few children felt uncomfortable answering and participating in the dialogues during the week (see Table 6).

These answers indicate that the children were very comfortable with participating in and actively sharing their thoughts during the dialogues. As our study was descriptive rather than experimental, we could not establish a causal explanation for the children’s experiences and behaviours. However, previous studies allow us to hypothesise that the openness and the feeling of belonging to a peer community may have positively impacted the children’s confidence and participation. Moreover, we found that the children, besides feeling comfortable their thoughts over the week, also thought that they participated in the dialogues to the extent that they desired.

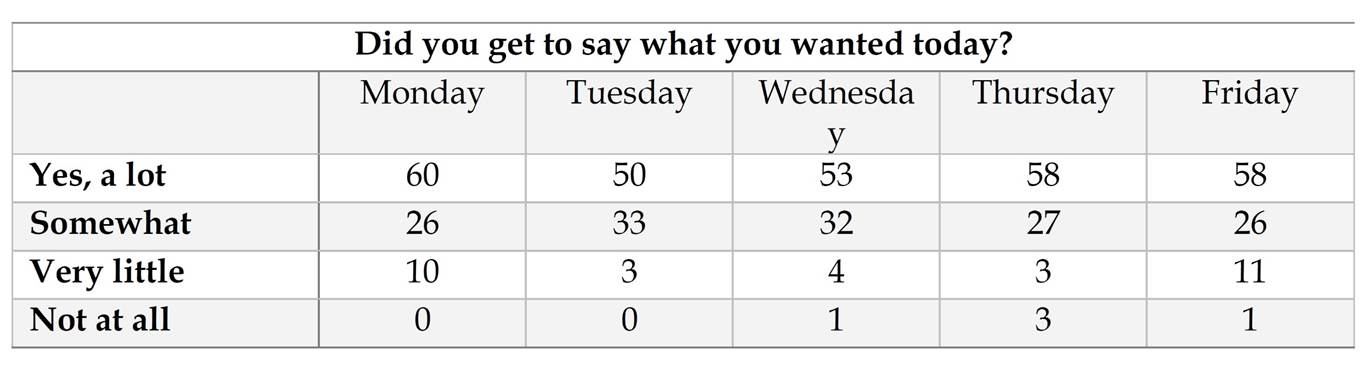

When asked “Did you get to say what you wanted today?” in the daily surveys, very few children answered that they did not get the chance to say what they wanted to or that they did so to a smaller degree than they would have wished. Throughout the five days, the children consistently reported that they participated to the extent they wanted to (see Table 7).

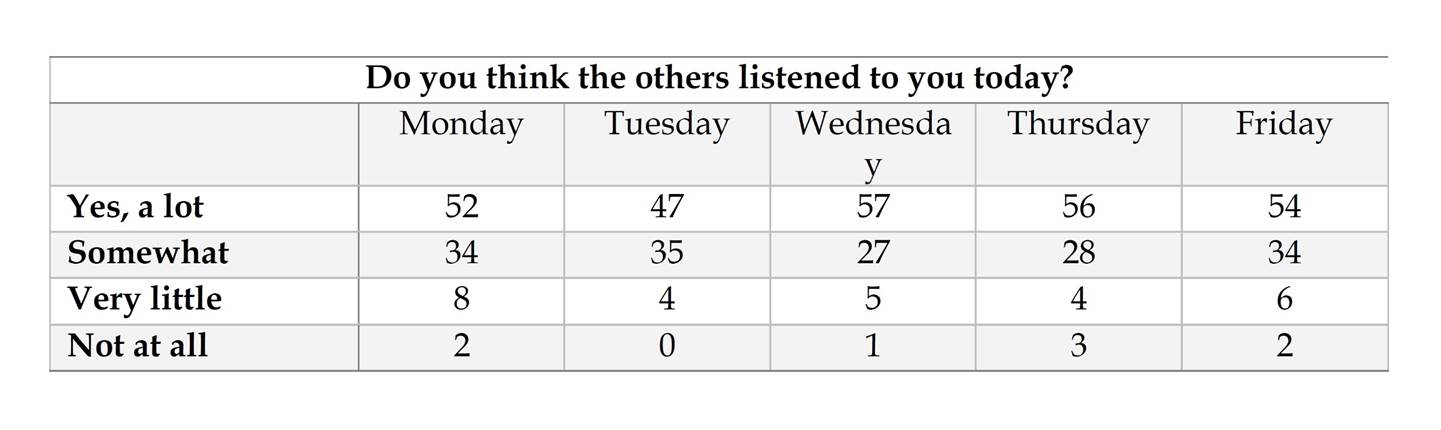

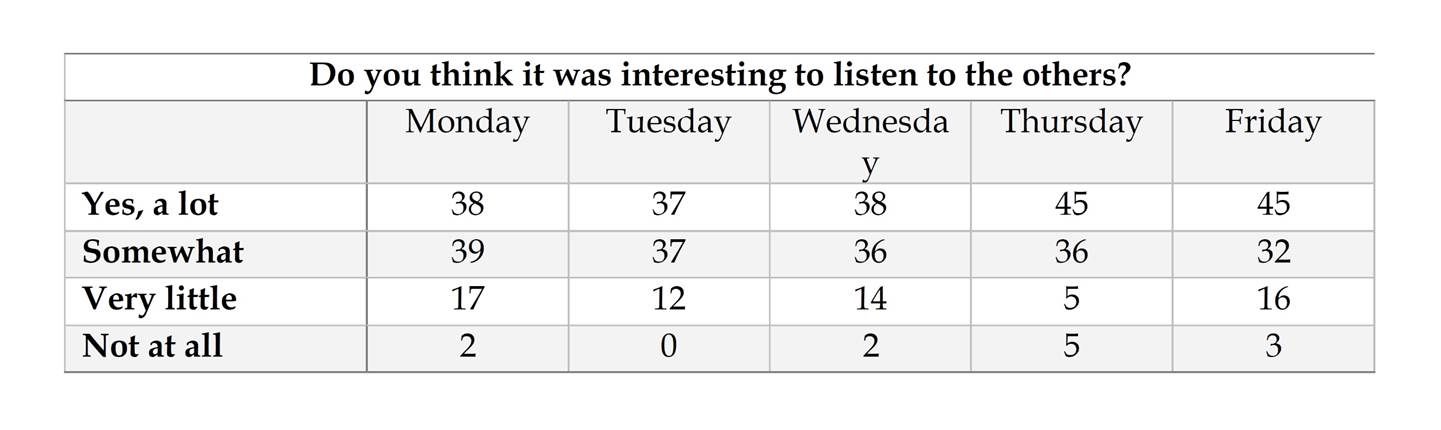

In addition to the fact that the children were generally comfortable sharing their thoughts and reported that they actually said what they wanted to, we found that the children thought that the other children listened to them and that it was interesting to listen to the others. We asked the children the following question: “Do you think the others listened to you today?” The children generally answered that they felt that the others listened to them (see Table 7).

We also asked them the following question: “Do you think it was interesting to listen to the others?” Many children indicated that it was. However, throughout the week, there were also groups of children (ranging from five to 17) who reported that it was not very interesting to listen to the others (see Table 8).

the children’s perceptions of the facilitator

The final focal point of our study was the children’s perceptions of the facilitator of the philosophical dialogues. The philosophical facilitator’s role differs from the traditional teacher’s role of being the authority figure (e.g. Lone, 2012b, p. 20), which is why we included questions in the post-survey on what the children liked and disliked about the facilitators.

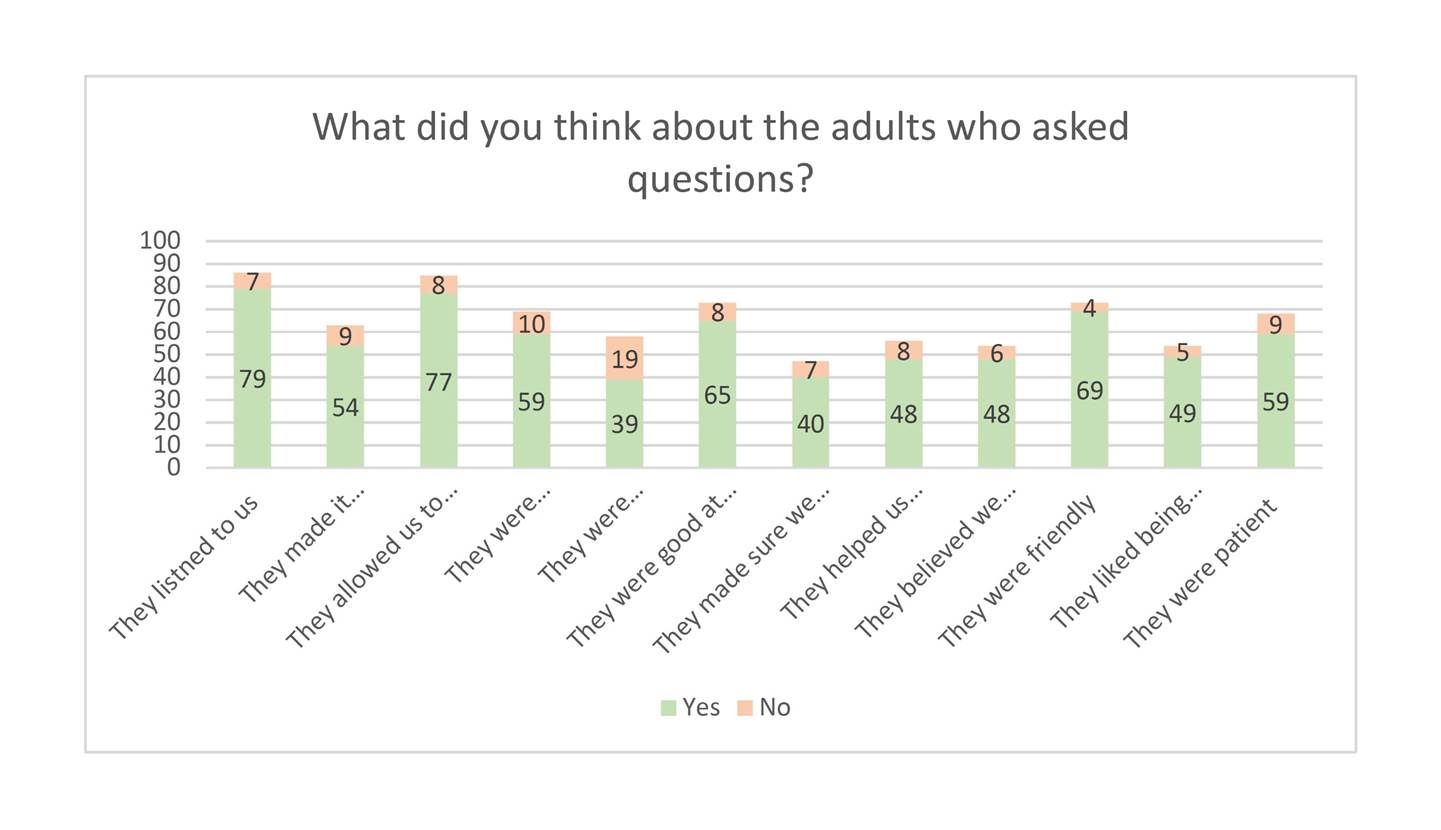

We gave the children the opportunity to report their experiences with the adult facilitators by presenting the children with two mirrored 12-item multiple-choice questions about “the adults who asked questions”. First, they were presented with the “positive” version of the question: “What things did you particularly like about the way they were?” Then, they were presented with the mirrored “negative” version: “What things did you dislike about the way they were?” We asked the children to tick all the predefined boxes that they agreed with. In general, the children reported very positive experiences with the facilitators (see Figure 2).

In addition to the predefined multiple-choice tick boxes, we gave the children the opportunity to provide additional free-text answers to the two sets of mirrored questions. Only a few (a total of 14) additional responses were provided. Some children further highlighted their already positive experiences with the facilitators: “They were SO sweet” or “They were nice all the time.” Others described negative experiences: “I did not think they were patient. And they interrupted us a lot”; or “They were just annoying.” In addition, some of the elaborate answers emphasised the fact that the facilitators were either boring or kept asking the same question. One child responded as follows: “It was as if they were not there. as if they were playing a computer game.”

Some of the traits that figured in the survey’s tick boxes (such as listening, inviting the participants to share their ideas and supporting peer cooperation) match the key points associated with the facilitator role compared to the classical teacher role (e.g. Lipman et al., 1980, pp. 82-101; Worley, 2016). By contrast, other traits (such as being good at telling stories) are not necessarily relevant to facilitation, and some traits (such as being patient or believing in the abilities of the participants) are only indirectly relevant. The trait of being interesting to listen to is irrelevant to the facilitator role in our approach. The facilitators should support the peer dialogue rather than offering interesting contributions of their own; moreover, besides asking questions to facilitate the dialogue, the facilitator should be noticed as little as possible (Worley, 2016).

Although the facilitator role is a very important feature of philosophical dialogues and dialogic teaching in general, the children in our study were not given any information on the pedagogical approach or the facilitator role associated with the dialogues. Therefore, it is interesting that the traits the children most often appreciated in the facilitators were actually aligned with the dialogic facilitator ideals. We have not found previous research on children’s perceptions of the dialogue facilitators (except for a report in which the children indicated that they liked it when the facilitators visited the school, Jackson, 1993, p. 40).

4. discussion

Our study outlines children’s perceptions of what it was like to participate in online philosophical dialogues. Despite not being instructed on the learning goals, the dialogic teaching approach or the facilitation ideals, the children’s answers reflected that they, in fact, experienced a number of characteristics essential to philosophical dialogues:

The children reported that they enjoyed the dialogues and experienced them as a supportive learning environment in which they could share their ideas freely. The prevalence of unprompted positive words associated with the dialogues was high, and throughout the week the vast majority of the children thought that the dialogues were fun and contained themes that they found interesting.

The majority of the children, though not all, found the activities valuable and meaningful. They indicated that they understood the contents of the dialogues, and many of them also showed that they understood the educational principles of the dialogues - for instance, that providing a correct answer was not a central goal.

The children generally experienced being part of a reciprocal community of inquiry: the children were comfortable participating in dialogues with their peers, they got to say what they wanted, and they experienced that the other children listened to them.

More often than not, the children thought that the adults behaved in ways that are essential to the facilitator role. Regarding important traits (such as listening to the children and allowing them to articulate their opinions), the vast majority of the children indicated that the facilitators did, in fact, possess such traits, while for non-relevant traits (such as storytelling or being interesting to listen to), fewer children indicated that the facilitators exhibited such traits.

why are these findings important?

It is beyond the scope of this article to explain or interpret the findings in detail, but they do offer us useful insights into children’s impressions of philosophical dialogues. First, our findings are interesting because they show that it is possible to translate the practice of philosophical dialogues from the physical to the online learning environment. Second, it is interesting that, to a large extent, our findings confirm the common experience of practitioners in Philosophy with Children (e.g. Martens, 2009; Haynes, 2007, pp. 229-230; Fisher, 2013, p. 6; Meir & McCann, 2017, pp. 90-91) - namely, that children generally enjoy participating in philosophical dialogues. It is important to document the children’s perspectives based not only on the facilitators’ or the spectators’ perspectives but also on the children’s own accounts of their experiences.

Finally, the children’s experiences indicate that the studied dialogue week exhibited essential features of dialogic teaching (e.g. Alexander, 2018b, p. 28): the dialogues were collective, reciprocal and supportive. The children even discerned important elements of the learning goals, even though the goals had not been introduced explicitly. It is not possible to determine from the children’s experiences whether the dialogues were also cumulative (i.e. whether the participants translated the ideas into “coherent lines of thinking and enquiry”; see Alexander, 2018b, p. 28), as this would require analysing the contents of the dialogues. Overall, while some children believed that they had learnt something, examining this element would require a further, different kind of study.

attention to children’s experiences

Although it has been difficult to establish a clear relation between student well-being and academic achievement, student well-being is often considered a prerequisite for academic achievement (e.g. Lei et al., 2018; Amholt et al., 2020), and many countries monitor school children’s well-being (e.g. Roberts et al., 2009). Similarly, learning outcomes have been evaluated in terms of educational or curricula outcomes using standardised tests, such as ACT, SAT and PISA. Educational research on test results has provided valuable quantifiable contributions to our understanding of what good education is. However, such approaches have rarely incorporated children’s thoughts and preferences with respect to learning (e.g. Gentilucci, 2004, p. 133). In general, while quantitative approaches can help determine school effectiveness in promoting children’s abilities to read and to solve math problems, such approaches are less effective in, for instance, understanding how we may encourage children to participate in classroom discussions with their peers. Children are important co-determinants of the learning that takes place in classrooms. Accordingly, understanding how children respond to various didactic or pedagogical methods is fundamental for increasing the impact of schooling (e.g. Gentilucci, 2004, p. 134; Hargreaves, 2017), which one reason why it is important to pay attention to children’s experiences of learning environments.

However, while the concern for effective schooling is important, it should not overshadow the fact that children are more than just students and that their well-being, autonomy and integrity are intrinsic values regardless of these traits’ additional potential to advance academic achievement (e.g. Hargreaves, 2017). We believe that the less freedom children have in schools and the longer that they stay there, the greater the responsibilities of the schools to protect these intrinsic values. In a similar vein, Philosophy with Children has consistently championed children’s voices (e.g. Lipman et al., 1980; Splitter & Sharp, 1995, pp. 167-171; Matthews, 1979; Lone, 2012a; Kohan, 2014), which obliges researchers from the field to pay continuous attention to children’s experiences to help ensure that these and other intrinsic values are realised. At the same time, while many studies describe how children think and talk during philosophical dialogues, few studies have examined how children think and talk about philosophical dialogues.

Inviting children to reflect and comment on philosophical dialogues not only gives them an opportunity to voice their opinions but also provides the chance to see the dialogues from the children’s perspectives. Of course, the adult is always an outsider to the children’s perspectives, but answers such as the ones we received in our study can, nevertheless, help us achieve a partial understanding of children’s experiences. Our study demonstrates the need for further attention to children’s experiences: the children in our study had many different views and described various experiences; in fact, in several cases, they had highly complex experiences that could appear contradictory without further investigation.

concluding remarks

The aim of our study was to examine children’s perspectives on 58 online philosophical dialogues conducted during emergency teaching at the time of the COVID-19 lockdown in Denmark. Similar studies on children’s experiences of philosophical dialogues are scarce and have all been conducted in physical environments; therefore, it is important to be cautious when making comparisons. Nevertheless, the limited empirical evidence that exists seems to reveal a common direction - namely, that children generally enjoy philosophical dialogues and provide similar reasons for their appreciations and reservations, regardless of whether the dialogues occur online or in the physical environment. Still, the online and physical learning environments are arguably very different, and further studies on the advantages and disadvantages of the two environments are needed. Conducting studies similar to ours but in physical settings would be a good start, as philosophical dialogues are usually held in physical spaces.

More generally, we believe that it is important for future research to systematically compare children’s experiences of philosophical dialogues with their experiences of traditional forms of teaching. These studies could be more sophisticated than our simple survey design. For instance, stronger research designs could add interviews and observations to validate survey findings, or they could use experimental designs to compare variables and counter biases. However, given the current state of the literature, any opportunity to examine children’s experiences of physical dialogues (using a method similar to ours) would provide new insights that could help improve our knowledge of children’s perspectives, which could benefit both practice and theory in Philosophy with Children and in dialogic teaching more broadly.