introduction

In the last two decades, some authors in the philosophy for children movement have theorized that the community of philosophical inquiry can be a form of spiritual practice, of the care of the self, or a wisdom practice (De Marzio, 2009; Gregory, 2009, 2013, 2014; Gregory & Laverty, 2009). In their article Philosophy for/with Children, Religious Education and Education for Spirituality (2018), Maughn R. Gregory and Stefano Oliverio present how the idea of spirituality was portrayed in the texts they consulted for their literature review on the relationship between philosophy for children and religion:

[T]he phrase ‘education for spirituality’ in the literature we have examined points to a broad range of phenomena, including a) the opening onto existential questions concerning the meaning of (human) existence or of one’s own life; b) consideration of what is sometimes captured with the notion of ‘soul’ as a sort of core of the personality that is not unrelated to the cognitive, cogitative and ethical dimensions of human existence but somehow exceeds them through a relation to the Whole, however that expression is understood; and/or c) a set of contemplative or ‘spiritual’ practices for self-work conducive to a radical transformation of our relation with the world of experience and of personality itself (see Hadot, 2001). (2018: 283)

Yet, it is unclear if philosophy for children is, by itself, a form of spiritual education, or if it requires some sorts of modification to be one. And, if it is or can be a form of spiritual education, we can interrogate in what ways and to what extent is it one. It is these questions that this text aims to explore. To do so, we will first clarify the meaning of spiritual education through the presentation of two authors who have explicitly written on that topic. The first is Parker J. Palmer, who has developed a perspective on what it means to reclaim the spiritual roots of education, derived from his study and practice of Quaker spirituality.1 The second is Pierre Hadot, who has explored how the practice of philosophy in Western antiquity was a form of spiritual exercise. From our presentation of these two authors will emerge a particular perspective of what spiritual education means. In the last section of the text we will use this presentation to examine in what ways philosophy for children can be a form of spiritual education and if it requires adaptations to be one. However, to achieve the goal of this paper, it is necessary to give a broad overview of philosophy for children, which will be the task of the following section.2

what is philosophy for children?

Philosophy for children is a movement that has Matthew Lipman (1923-2010), Ann Margaret Sharp (1942-2010), and Gareth B. Matthews (1929-2011) as its founding figures.3 Its main aim is to bring children to do philosophy. This movement has developed in different ways over the last decades since its creation in the late 1960s (see Vansielghem and Kennedy, 2011). There remain, however, certain elements that we think are fundamental to the philosophy for children community. One is that the community of philosophical inquiry is the central pedagogy to be used to do philosophy for children. According to Gregory, though the necessary role of a community to scientific and philosophical inquiry was first articulated by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914) the precise phrase ‘community of inquiry’-which does not occur in Peirce’s writings-was coined in 1978 by Lipman and Sharp, who were also the first to adapt the idea to an educational program, namely, philosophy for children (see Gregory, 2022). The community of philosophical inquiry became “The most lasting and far-reaching legacy of Lipman and Sharp’s collaboration was the protocol they developed for children’s philosophical practice” (Gregory, 2021: 158). The community of philosophical inquiry is a process through which a group of people pass from an experience that creates philosophical perplexity (as reading a text), to the formulation of a shared discussion question, through a process of collaborative inquiry, to a satisfying answer. The exchange of reasons and perspectives used in this process makes it likely that the concluding judgments will be more reasonable than unreflective opinions about the matter.

The process usually follows certain steps or stages, articulated by Lipman (2003): 1) give a text or a different form of stimulus that will raise philosophical perplexities in the students, 2) ask the students to formulate questions for inquiry, 3) invite them to choose through a vote the question they will like to discuss first, 4) inquire on the question selected with the help of a teacher whose role is to lead the inquiry by scaffolding their critical, creative, and caring thinking, and 5) ask the students to evaluate the quality of the inquiry. These steps may be modified or moved, and other steps could be also be added: for example, some participants could be given roles for the sessions or a time could be added to categorize or clarify questions; participants could be invited to note in their philosophical notebook what they have learned during the session. But these steps present a certain structure that we are most likely to find in a community philosophical inquiry in the Lipman/Sharp tradition, as can be seen in the following books that have been published over the years on that method: Philosophy for children: Practitioner Handbook (2008), Penser Ensemble à l’École: Des Outils pour l’Observation d’une Communauté de Recherche Philosophique (2020), Pourquoi et Comment Philosopher avec les Enfants (2018), A Teacher Guide to Philosophy for children (2019), Philosopher par le dialogue: Quatre méthodes (2020), and Filosofía para Niños (2004).

In this process, the classroom teacher sees herself as a facilitator. Her role is not to give an answer to the question discussed, but to ensure that the principles of the inquiry are respected, which means, foremost, to bring students to use and develop their thinking and social skills. In the philosophy for children movement, these skills are often divided into three large dimensions: critical, creative, and caring thinking (Blond-Rzewuski et al., 2018; Lipman, 2003; Topping et al., 2019). The inquiry can then be seen as an having the trajectory of an “arc”, as participants move collaboratively from a puzzling question to a reasonable judgment (Gregory, 2007).

parker palmer and the spiritual dimension of education

The first author we will analyze to explore the meaning of spiritual education is Parker J. Palmer. His intention to reclaim and promote the spiritual roots of education can be seen in the title of his books: To Know as We Are Known: Education as a Spiritual Journey (1993) and The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life (2007). Although Palmer develops theoretical and philosophical arguments, he inscribes himself in the Christian tradition, and more specifically to The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) (Palmer, 2003). Yet, his ideas are not meant to convert the reader to his religious point of view, nor do we need to accept particular religious tenets to understand them (see for example Gould, 2010; William Aylor, 2008). Rather, drawing on his specific perspective, Palmer aims to illuminate deeper dimensions of teaching and learning that we may all understand beyond our own religious beliefs.

For Palmer, one of the main starting points of the spiritual endeavor is pain: a sense of disconnection, brokenness or suffering is a signal that something is going wrong in our life and a call to engage in a spiritual endeavor. The important point is the way that we relate to our own suffering: not to see it as something that makes us wrong or defective, but as an alert indicating that we should reconnect with neglected but important dimensions of our existence. “When suffering becomes intense, we are forced to examine the deeper dimension of our condition” (Palmer, 1993: x). This point also appears in the diagnosis that Palmer makes regarding education, and, more specifically, about educators: “I call the pain that permeates education ‘the pain of disconnectedness’. Everywhere I go, I meet faculty who feel disconnected from their colleagues, from their students, and from their own hearts” (1993: x). Therefore, the spiritual path will be one of reconnection: with our students, our colleagues, ourselves, and also the subject we research and teach, that used to animate us.

It is important to note at this point that Palmer is not talking about how to teach students, but rather about the teacher, about her identity. In this perspective, the “I” of the teacher is the entrance to the spiritual path and, to some extent, its object. We say the point of entrance, because the “I” indicates the need of engaging in a certain process. It is not an abstract “I”, but a concrete “I”, with a particular history, passions, hopes and fears. It is the object, because the goal is the transformation of oneself. In that sense, we can say that Palmer inscribes himself in a certain trend of modern education which puts teachers’ identity and their quest for meaning and fulfillment as among the first means of good education, more fundamental, even, than the possession of knowledge and teaching techniques.4

How can this process happen? The first steps appears to be to pay attention to oneself; to move our gaze from what we are doing or what is going on around us to who we are. As Palmer states, “Attention to the inner life is not romanticism [...] and it is what is desperately needed in so many sectors of [...] education” (1999: 16). It also requires that we be in a certain state, as to be able to listen and to obey. This invitation to obey may sound odd to our ears, but here is how Palmer explains the link between listening and obedience: “The word ‘obedience’ does not mean slavish, uncritical adherence; it comes from the Latin root audire, which means ‘to listen’” (1993: 43). It is this relationship between openness, listening and obedience that is summarized in the following passage discussing the link between truth and spirituality: “Authentic spirituality wants to open us to truth-whatever truth may be, whenever truth may take us. Such a spirituality does not dictate where we must go, but trusts that any path walked with integrity will take us to a place of knowledge” (1993: xi). The search for truth is defined by the authenticity and the integrity of the searcher in the journey as well as of her capacity to be vulnerable, to be ready to change in front of what we find. The spiritual path is then the creation of an inner space to “listen,” which, in turn, puts the person in a relationship with a subject-be that inner wisdom and/or one’s academic subject.

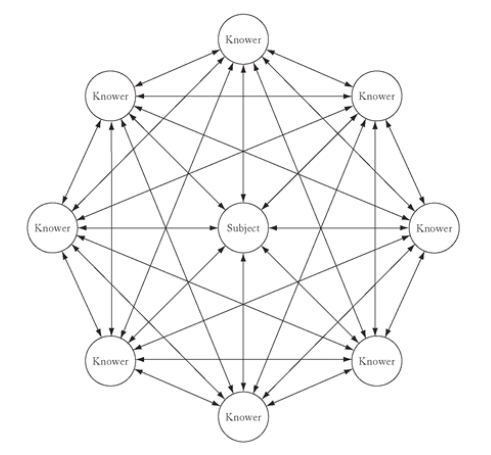

If spirituality is about self-transformation, it is for Palmer particularly suited to be done with others. In the previous paragraphs, we have presented how the teacher may embark on a spiritual path, but Palmer also delineates a form of spiritual pedagogy that could be implemented in a classroom. He summarizes his view of teaching in the following sentence: “to teach is to create a space in which the community of truth is practiced” (2007: 91, italics original). To teach is to create an environment in which individuals will be in a relationship with a specific subject matter as well as with themselves and with each other. In that sense, what Palmer calls “the community of truth” is close to the community of inquiry in the philosophy for children movement. The following figure that Palmer uses to explain the community of truth shows how the two are similar in nature.

Learning happens when individuals come into a relationship with the subject that is the center of the inquiry and with each other. This means that learners must not endeavor to put away their own subjectivity. Indeed, one of the principles of the pedagogy that Palmer puts forward is to connect the large ideas and issues of a discipline with the little stories of the learners.

Furthermore, the big ideas and issues of the disciplines-what Palmer calls the “great ideas” (2007: 89)-can never be fully captured. This why they remain open to inquiry. It is not that there are no advances in each discipline, but it would be a mistake to believe that we have arrived at the ultimate answer to any of the fundamental questions that structure them. We have to approach the great things as beyond ourselves, and beyond our current understanding of it. Thus, for Palmer, “if we could recover a sense of the sacred in knowing, teaching, and learning, we could recover our sense of [...] the precious otherness of the things of the world” (1999: 23). In studying a subject, we find that the subject has, in some way, a life of its own, and we have to remain open to what this subject has to tell us, to be able to listen. “We will experience the power of great things only when we grant them a life of their own-an inwardness, identity, and integrity that make them more than objects, a quality of being and agency that does not rely on us and our thoughts about them” (2007: 109).

Palmer’s view of the “great things” as something that we cannot fully capture or master through our intellectual tools makes doubt and mystery inseparable from the learning process. This can be seen in the value that Palmer places on paradox, as indicated in this quote he attributes to the Danish physicist Niels Bohr: “‘The opposite of a true statement is a false statement, but the opposite of a profound truth can be another profound truth.’ With a few well-chosen words, Bohr defines a concept that is essential to thinking the world together-the concept of paradox” (2007: 62).5 In other words, it is likely that we will be unable to find a single, definitive answer to a profound question, that we will have to accept that there are two or more divergent answers to it.

Regarding how to engage with the paradoxical nature of truth, Palmer cites the well-known admonition of the poet Maria Rainer Rilke to learn to live with questions:

Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves […]. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer. (Rilke, 1993: 35, cited in Palmer, 2007: 86, italics by Palmer)

To love and live the questions does not mean to stop seeking answers to them, but to accept that the seeking, and the doubt attached to it, may never end, and that there is something precious in sustaining a wondering, questioning stance toward the subject. This can only be done if we “love” the question and not look at it as something that has to be overcome.

We will now turn to Hadot, who explains how the practice of philosophy was a form of spiritual exercise in its birth in Western antiquity. We find it significant that while Palmer’s understanding of the spiritual dimension of education derives from an overtly religious tradition, and Hadot’s understanding derives from ancient Greek and Roman pagan philosophical schools, the two scholars share important insights.

pierre hadot and the practice of philosophy

For Hadot, Western philosophy has fundamentally changed since its birth in antiquity and this change has led to a loss in the meaning of doing philosophy. The central element of his thesis is that philosophy was, in ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, a way of life-a commitment, that is, to (attempting to) live a certain kind of life-and that since then it has become mostly an intellectual activity. In the universities, for instance, students and professors can be specialists of certain philosophers or develop impressive theoretical arguments, but there is no expectation or need for them to be living philosophically. We bring this perspective to our reading of ancient philosophers, whom we study today as if they had each invented “a new construction, systematic and abstract, intended somehow or other to explain the universe” (Hadot, 2002b: 2.) This theoretical dominance was alien to the meaning of philosophy in antiquity, when it could not be dissociated from the ways of life of individuals and of philosophical schools.

Hadot’s thesis is that we cannot understand ancient philosophy or ancient philosophical texts if we disconnect them from the ways of life they were related to. For one thing, it has to be remembered that ancient texts, though written, were created in a time of orality, and that they were meant to be spoken, or at least to record and replicate the nature of the spoken word. They were not intended to present a systematic overview of a philosopher’s theories, but rather to give a particular kind of experience to a specific audience. “In antiquity, philosophy was essentially dialogue, rather a lived relationship between individuals, than abstract connections to ideas. It aims to form rather than inform, to retake the excellent formula of Victor Goldschmidt, who employed it for Plato’s dialogues” (Hadot, 2002a: 97, our translation). Plato’s dialogues, as other ancient texts, were intended to put individuals in a certain “disposition” (Hadot, 2002b: 104) and to give to the members of his school “a method to orient themselves in thought as well as in life” (Hadot, 2002a: 148), rather than to transfer a body of knowledge to the reader. As Martha Nussbaum observed:

[W]e can see, if we look at these dialogues as the startling stylistic innovations they were (the first dramatic works of philosophy and also the first prose works of theatre) that Plato has used the resources of theatrical writing to create real dialectical searching in a written text. He has produced a book that does not preach or claim to know, but that searches and criticizes. In its open-mindedness it sets up a similarly dialectical activity with the reader, who is invited to enter critically and actively into the give and take.[...] We can add that by connecting the different positions on an issue with concretely characterized persons, the dialogue, like a tragic drama, can make many subtle suggestions about the connections between belief and action, between an intellectual position and a way of life. This aspect of the dialogue form urges us as readers to assess our own individual relationship to the dialogue's issues and arguments. (1985:14)6

One point that stands out in Hadot’s presentation of ancient philosophy is the paradoxical nature of the search for truth and wisdom. On the one hand, it seems that each philosophical school arrived at certain truths that structured the life of its members and the functioning of the school. On the other hand, each school also kept open an inquiry into the nature of those same truths. That paradox appears most clearly in the life of Socrates, the founding figure of the western philosophical tradition. Socrates exemplifies Hadot’s point that Ancient philosophy was a way of living. As Hadot asked, can “Socrates’ discourse be separated from the life and death of Socrates?” (2002b: 6). Socrates does not seek what others seek, such as reputation or wealth, and gives himself the mission to awaken his fellow citizens to the fact that they are ignorant regarding the most important questions-those regarding what it means to live a worthwhile human life. He will finally die in accordance with the principles he gave himself, by doing what he thinks is good, which includes, in part, to follow the laws of his city.

Socrates is a paradoxical figure because he appears as one thing and is actually something else: the most important thing he knows is that he is ignorant, and he teaches while having no doctrine to teach. Socrates initiates the paradigm of the philosopher precisely because is not a possessor, but a lover of wisdom. His life indicates that we should always privilege the search for wisdom-the inquiry-above the tentative conclusions we may reach. As Hadot explained, Socrates gives the “program of philosophy” in Antiquity:

With the Symposium, the etymology of the word philosophia-“the love or the desire for wisdom”-thus becomes the very program of philosophy. We can say that with the Socrates of the Symposium, philosophy takes on a definite historical tonality which is ironic and tragic at the same time. It is ironic, in that the true philosopher will always be the person who knows that he is not a sage, and is therefore neither sage nor nonsage. He is not at home in either the world of senseless people or the world of the sage […]. Philosophy’s tonality is also tragic, because the bizarre being called the ‘philosopher’ is tortured and torn by the desire to attain wisdom which escapes him, yet which he loves (2002b: 46-47).

This “program” will influence the schools that will appear after Socrates. Philosophy is from then on, for a time, at least, a constant desire and effort to seek something that can’t be fully attained: knowledge or wisdom-an impossible endeavor that the philosopher is aware of as such. Of course, the life of Socrates also demonstrates that the practice of philosophy is not futile. In spite of not delivering wisdom in any final or complete sense, the practice brings the philosopher near to it in some ways. It reveals certain ways of living to be unworthy, ultimately unsatisfying, and others to be full of consolation.

Furthermore, the quest for wisdom is not a solitary process, as Socrates is fundamentally involved in his city. He speaks to specific individuals and not to an abstract audience. Indeed, his philosophical practice is thoroughly dialogical. He sees himself as a midwife helping others to find the truth by themselves, in themselves (see Matthews, 2022). Socrates is without question a teacher-not a teacher who will tell his interlocutors what to think, but rather one who will bring them to discover certain truths by questioning themselves. Again, philosophy here is more an activity than an answer. It is, in fact, an educational process that begins when the individual awakens to their own state of ignorance-an awakening that is not prompted by explanation but by the experience of dialogue with one who is already awake. “Like a ‘gadfly’, Socrates harasses his interlocutors with questions which place them in question, and obliges them to pay attention to themselves and to take care of themselves” (Hadot, 2002b: 28). The act of awakening is fundamental to the act of philosophizing. And it is spiritual in nature. “Doing philosophy no longer meant, as the Sophists had it, acquiring knowledge, know-how, or sophia; it meant questioning ourselves, because we have the feeling we are not what we ought to be” (Hadot, 2002b: 29); “in all schools, the beginning of philosophy means becoming aware of the state of alienation, dispersion, and unhappiness in which we find ourselves before we convert to philosophy” (Hadot, 2002b: 198).

Socratic spiritual awakening starts with a conversational dialogue, which leads to the possibility of philosophical dialogue. Hence, after being questioned in a way that makes them question themselves, Socrates’ interlocutors can begin to engage in the search for truth-which will also be done through a process of careful, thoughtful dialogue. “In order for a dialogue to be established which [...] can lead the individual to give an account of himself and of his life, the person who talks with Socrates must submit, along with Socrates, to the demand of the rational discourse-that is, to the demand of reason” (Hadot, 2002b: 32). This kind of dialogue does not involve knowledge being poured from one person to another; in fact, it limits the very possibility of transmitting knowledge. Here is how Hadot describes it:

The task of dialogue consists even essentially to show the limits of language, the impossibility for language to communicate moral and existential experience. But the dialogue itself as an event, as a spiritual activity, has already been a moral and existential experience. Socratic philosophy is not the solitary elaboration of a system, but awakening of consciousness to a new level of being that can only be realized in a relationship of a person to another person. (2002a: 129, our translation)

Hadot came to see this dialogical experience as a “spiritual exercise” (2002a: 41), not merely because of what might be said, but because of the existential nature of the questions being asked, the willingness of the participants to put themselves, their ways of life and their deepest commitments into question, and their willingness, as well, to make themselves vulnerable to the constraints of reason and to the justness of other people’s insights.

After the death of Socrates, there will be some philosophers who will embrace more clearly the importance of doubt, as the ones following Pyrrho and the members of the skeptic schools. Yet, even in the dogmatic schools (Platonic, Aristotelean, Epicurean and Stoic), the importance of inquiry will remain central. For example, Platonic discourse, as mentioned above, would have the same objective:

The sense of these exercises is obvious in what we call the Socratic discourse, but which is also finally the Platonic discourse, in which the questions and answers are meant to provoke in the individual a doubt, even an emotion, a bite, as Plato says. This type of dialogue is an asceticism; you have to submit to the laws of discussion, which means firstly to recognize for the other the right to speak; secondly, to recognize that if there is evidence, we have to rally to this evidence, which is often difficult when we discover that we are wrong; and then, thirdly, to recognize the norm that the Greeks call the logos; an objective discourse, that searches at least to be objective. (Hadot, Carlier, & Davidson, 2001: 147, our translation)

As we mentioned, Plato’s dialogues aimed to form and not to inform those who read them. Furthermore, the followers of Plato in the Academy will have different views on different subjects, but they all share a common form of a way of life in which dialogue and inquiry are central components.

The practice of dialogue and inquiry will remain in the philosophical schools that will appear afterward in Antiquity, although to different extents.7 Each school will then develop a variety of exercises that will have for their purpose to facilitate self-transformation toward a wiser self, as that was understood in each school.

philosophy for children as a form of spiritual education

Our aim in this paper is to see if philosophy for children is intrinsically a form of spiritual education, or if it requires some adaptations to be one. To this end, we have first offered a general presentation of philosophy for children in the Lipman/Sharp tradition. We have posited that the community of inquiry is a central component in that movement, as the main pedagogy to be used to do philosophy with children and youth. We defined it as a structured process of different steps to pass from a question to reasonable judgments. This process is done in a group, through dialogue, the practice of thinking skills and the help of a facilitator whose function is to structure the inquiry and not to attempt to teach their own answer to the question discussed. We have acknowledged that this picture was limited regarding the overall movement that has become philosophy for children worldwide, but we have proposed it because we think that it still informs its implementation in the different parts of the world. We have then used two authors who address the notion of spirituality directly in their writing to clarify the meaning of a spiritual education: Parker Palmer who presents the spiritual dimension of education and Pierre Hadot who details how the practice of philosophy in antiquity was a form of spiritual experience.

Before turning to the relationships between Palmer and Hadot, we have first to note that there are some differences between them, attributable to the different traditions within which they work. The most important difference is about the kind of “I” that is transformed in the spiritual experience. For Palmer, it seems that each individual has a particular essence. It is to this essence that we have to reconnect in the spiritual path or that we have to take into consideration in the inquiry. However, Hadot, in his study of ancient philosophy, does not talk about a similar form of subjectivity. The “know thyself” of Socrates may in fact point toward a form of essence that is not particular to an individual, but to the essence of human beings in general. In that sense, Palmer inscribes himself in Modern thought and the ideal of authenticity: that each individual has an essence that can be found by herself and transformed by herself-a principle that was foreign to the antique thinkers Hadot was studying (see Taylor, 1992; Taylor & Gutmann, 1994).

Beyond this major difference, we can see similarities regarding the nature of the spiritual dimension as portrayed by Palmer and Hadot. Both point out that the spiritual experience starts with the individual realizing that her life is not satisfying. This in turn opens the possibility to look for a better life. Thus, spiritual endeavor is foremost a process of self-transformation, a search toward the good life. Yet, for both authors, this experience is particularly practiced with others, through dialogue or the creation of a community. Neither wisdom nor knowledge can be poured from one individual to another; each can only be created by individuals in relationship with others. Therefore, the practice of the community of truth of Palmer and the ancient practice of philosophy as presented by Hadot both aim to create a communal space where the individual can change. The two authors also point out the limits of language and of our knowledge to capture deep subjects. We have to accept that we won’t be able, ultimately, to fully capture them intellectually. Palmer writes of the “great things” that remain ultimately beyond our understanding. Hadot, similarly, points out that “the program” of philosophy as depicted in the Symposium is the search for wisdom by those who love it but do not possess it.

What does this presentation tell us about the link between spiritual education and philosophy for children? First, it is apparent that there are common points between our presentation of the spiritual experience and our presentation of the core elements of philosophy for children. We saw that the children’s inquiry starts with a kind of puzzlement framed as a question, which can be put into relation with the idea that spiritual experience starts with a form of awakening to one’s own ignorance. The creation of doubt or perplexity is one of the essential functions of the artifact used at the beginning of a philosophy session, as it aims to bring participants to contemplate and reflect on one or a number of philosophical perplexities. We contend that to problematize some part of our lives-particularly in their ethical, political, aesthetic, or metaphysical dimensions-to articulate a philosophical question we recognize as significant in meaning and to realize that neither we, nor perhaps our teacher or our community has a satisfying answer to hand, is an important spiritual experience.

The inquiry that follows in the wake of the question is sometimes characterized in terms of play, of wrestling or contending, of exploration and discovery, or of forensic or scientific investigation. In any case, the inquiry is essentially communal, as the participants in the community of inquiry must think, feel, and create together to try to answer the question. Nor is this inquiry conducted in a transmission model, in which the teacher transmits knowledge or beliefs to students, or more advanced students to those less advanced. Rather, the community of philosophical inquiry is a space in which each member seeks the answers for themselves through collaboration with others. And as with all kinds of skillful play, contention, exploration, and investigation, philosophical inquiry both requires careful coordination among the participants and draws out of each of them a higher level of individual skill than they are otherwise capable of.

The integration of philosophy in the school curriculum also aims to bring self-correction in the students, as it is hoped that those who regularly practice that pedagogy will develop certain intellectual, social, and moral skills and dispositions. It is also hoped that reflection on philosophical matters such as the nature of personhood, friendship, beauty, and justice will help young people develop a deeper appreciation of the meaning of their lives, their relationships, and their choices and actions. However, while for Palmer and Hadot, spiritual self-transformation has to be understood in a deep sense, as a change that will influence all parts of one’s life, it is not obvious that the transformations effected by philosophy for children are of that character. In addition, spiritual self-transformation cannot be produced or imposed, but must come from the individual herself. In a school setting with mandatory school subjects, all that can be hoped for is to create a space where engagement in personal transformation is made possible. This appeared clearly in the ancient schools portrayed by Hadot, as the individuals who entered in a particular school had first to make a decision to change and to engage in the lifestyle of that school. Perhaps the most that can be claimed for philosophy for children, is that it is well suited, through its pedagogy and the philosophical subjects discussed during the philosophical sessions, to effect personal transformation in the deeper sense, as it creates a space and a method for participants to reflect deeply on many of the most important concepts relevant to their lives.

In sum, it is certainly possible to draw clear parallels between the traditional view of the community of inquiry and education as a spiritual practice as presented by Palmer and Hadot. The community of philosophical inquiry can be seen as a form of spiritual education and it does not require any kind of specific modification to be considered as one.

philosophy and spiritual growth

However, we also think that the two authors we presented give us the opportunity to see the practice of philosophy for children differently. They first invite us to displace our gaze from the process of the community of inquiry and what students are learning to the facilitator-not of what she is doing to animate a session of philosophy, but to whom she is as a person. Palmer, for instance, addresses the teacher, her identity and her experience as a teacher, not teaching techniques or learning objectives. The most important element for a teacher is not the pedagogy she uses, but the sense that her teaching is rooted in who she is. Similarly, Hadot indicates the first characteristic of the philosopher is that he engages in a certain form of life, and that this form of life is intrinsically related to an honest pursue of wisdom. On the contrary, the person who only teaches about virtues without practicing virtue is merely a sophist. Therefore, instead of focusing on what should be done inside the community of inquiry, as the steps to follow or the skills to be learned, Palmer and Hadot invite the facilitator to pay attention to herself: How does she feel? What gives meaning to her in bringing philosophy to her classroom? Does she feel any sense of disconnection? In other words, is the teacher herself spiritually engaged? Does she understand her teaching practice as a calling to transform herself? It would be indeed illogical, from the perspective developed in this text, to try to teach philosophy or facilitate a community of philosophical inquiry without at the same time engaging in a philosophical life.

Palmer and Hadot also underline the fact that we are unable to completely grasp the deepest subjects through our knowledge and language. For Palmer, we may increase our knowledge of the “great things”, but they will remain full of mystery for us. Hadot emphasized the fact the philosopher is one who (still) looks for wisdom, precisely because he does not fully possesses it. We can then see that these two authors invite us to refocus our attention on the subject and questions that are discussed inside the community of inquiry rather than the conclusions or judgments that should be reached in specific sessions. The traditional view of philosophy for children emphasized that philosophical concepts are “central to our lives […] Common to most people’s experience”, and, what is more important for us, that they are “contestable, or puzzling” (Gregory, 2008: 2). As we presented, the goal of the community of inquiry, its very essence, is to move from puzzlement to a reasonable judgment. Yet, we believe these two authors lead us to not forget that the subject we tackle in a session of philosophy will inevitably remain open to inquiry. This does not mean that there cannot be advancement in our reflection on a philosophical subject: we may arrive at certain judgments that are eminently reasonable. It prompts us, however, to be humble in front of philosophical subjects that are discussed: to see our progress as limited and temporary; to be ready to tackle these subjects again and again, in the search for increasingly adequate understandings; and to find purpose in frequenting them rather than aiming at closing them once and for all.8

Three important points emerge from this last consideration. First, while children may productively philosophize about mundane intellectual puzzles, philosophy as a form of spiritual education invites children to explore the central, existential philosophical issues they confront in their lives. This, in fact, harkens back to Lipman and Sharp’s pragmatist-oriented understanding of philosophy:

[Philosophy] takes on significance only when children begin to manifest the capacity to think for themselves and to figure out their own answers about life’s important issues. As philosophy opens up alternative possibilities for individuals' leading qualitatively better lives-richer and more meaningful lives-it gains a growing place in the school curriculum. (1980: 83-84)

Second, facilitators should be conscious that while the community will likely not reach any kind of definite answer to such questions, other kinds of progress in the inquiry are equally valuable, including tentative answers, personal insights, and a deeper understanding of the question itself. The benefit of doing philosophy is therefore not in attaining a definite answer to one of the “big” questions, but in the experience of visiting and revisiting them. Third, therefore, we may be led to see aporia (doubt, perplexity, even confusion) as something positive and productive. This position may be more easily adopted by seasoned philosophers and philosophy for children practitioners, who know the enthusiasm of entering into an inquiry without the expectation of reaching an outcome that is ultimately satisfying. However, it may be more difficult to make this kind of ambiguity appealing for younger persons learning to practice philosophy. As Gareth Matthews points out at the end of his book Socratic perplexity: The nature of philosophy, “There is, of course, the danger that, when philosophy gives us no answers, only questions and perplexities, we will become cynical and nihilistic, not gentle and modest” (1999: 127). One way to ameliorate this risk is to mark many kinds of progress made by a community of inquiry, as proposed by Gregory (2007) and Clinton Golding (2017). Yet, it remains to be studied how young philosophers can make sense of the paradoxical nature of philosophical inquiry as a process that can advance and, at the same time, remain ultimately open to further inquiry.

We have indicated that we see an important difference between Palmer and Hadot’s views of the individual: that Palmer belongs to the era of modernity and its value of authenticity, which calls on individuals to discover or to create their own particular identity-a value foreign to the ancient philosophers treated by Hadot. Palmer’s principle that teaching should lead individuals to connect to their unique inner lives, as well as to the objects of their study, indicates a particular practice of the community of inquiry. It invites us to emphasize the connection between the participants’ lives and the topic of their philosophical inquiry. Of course, this connection already exists in philosophy for children to an extent, but traditionally, the inquiry is meant to move away from characters and situations in the philosophical novels, and from the personal experiences of the participants, toward a more general, shared, and even impersonal understanding of the question discussed or the subject studied. Personal examples are welcome, but treated as generic cases to be considered as potential planks for argument building.9 Palmer invites us to always put ourselves in question when we philosophize; to consider what meaning the question has for us, how we might apply the concept in our own life, or how our life permits to illuminate or challenge that concept. He recommends that we make room for our “little” or personal stories in our study of “the big stories of the disciplines” (Palmer 2017: 76). An interesting technique for doing this is to integrate ‘story circles’ into the philosophy community, as proposed by Fletcher et al. (2021).

In conclusion, there are good reasons both to see philosophy for children as a form of spiritual education, and to inform our understanding of the potential meaning of philosophical practice by a study of spiritual education, including such scholars as we Parker Palmer and Pierre Hadot. Foremost, philosophy for children may be one of the rare spaces in schools where children and teenagers can pause to reflect by themselves, rationally and communally, on the meaning of the most important questions and concepts in life, such as those concerning happiness, friendship, justice, and death. It does not follow from what precedes that there should be major changes in the pedagogy of the community of philosophical inquiry to be considered a form of spiritual education, but it appears that a spiritual perspective could bring a different view on how we practice this pedagogy.