philosophy of childhood and children's political participation: poli(s)phonic challenges

Research is not about enumerating situations, but making researchers lose sleep.4

This text stems from the communication made at the 20th International Council of Philosophical Inquiry with Children (ICPIC), Tokyo, Japan, under the theme: Philosophy in and beyond the classroom: P4wC across cultural, social, and political differences. This world forum dedicated to research on Philosophy with/for Children brings together experts5, people who have a special relationship with the idea of bringing children and philosophy together.

Our article is a part of a wider research project called escuto.te: childhood voices between philosophy and politics. The project name “escuto.te” means “I listen to you” and started from the disrupting discomfort that we as educators feel about the places that children's voices occupy, about their participation in a variety of contexts within the polis, and whether or not these voices are heard and taken seriously. We aim to reflect on the importance of the real voices that inhabit the public spaces of childhood.

What challenges does the political participation of children pose to the Philosophy of Childhood (Matthews, 1994; Kennedy, Bahler, 2017)? What challenges does the Philosophy of Childhood pose to children's political participation? The text we share is inspired by the idea that “research is not about enumerating situations, but making researchers lose sleep”.

The text is divided into two distinct parts. In the first, we introduce the theoretical framework that underpins our research group and our work with children in the philosophical research community. We are concerned about the widespread absence of children's voices in the political spaces of childhood in general and in school in particular. We will attempt to establish a link between listening to children's voices, the conditions of listening, and the location of their political participation in public spaces.

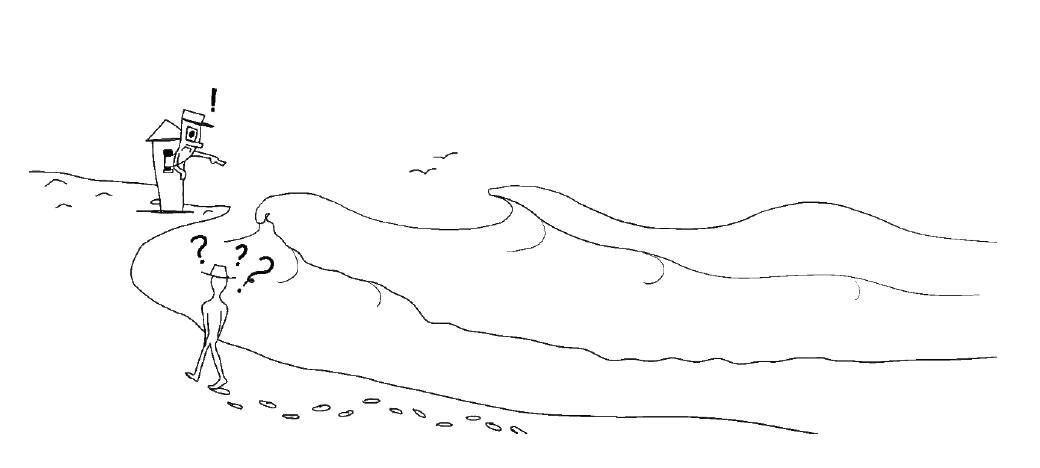

The second part is a creative illustrated narrative in the form of a dialogue. From the coast of what could be called the territory of political participation, two characters - Sentinel and Wanderer - discuss the waves of children that crash onto the territory6. Can political participation be understood as a territory framed by legal and other boundaries that fence in or restrict access to all human groups? What sentinels do we find guarding access to such a territory? What sorts of wanderings challenge the polis when it allows itself to be crossed by new and different polyphonies?

the issue of listening to children's voices

The Convention on the Rights of the Child7 (United Nations, 1989) establishes in article 12.1 the right of children to freely express their opinions on issues that concern them. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, in the General Comment Nº. 12 of the CRC: The right of the child to be heard. (United Nations, 2009)8 argues that this right is crucial to participatory processes and aims to promote “an intense exchange between children and adults on the development of policies, programs, and measures in all relevant contexts of children's lives” (CRC/C/GC/12, p. 7). Article 12 maintains that the child has rights of participation, and not only rights of protection, which originate with his or her vulnerability, and rights of provision, which stem from his or her dependence on adults (CRC/C/GC/12 §18). This innovative character of the CRC, fruit of a long process toward respecting the opinion of children in matters pertaining to them constitutes one of its fundamental values.

Are we prepared to hear the voices of children? What conditions will make that possible? UNESCO (2007, p. 3) recognizes the relevance of the practice of Philosophy for Children for the community of philosophical inquiry model, establishing a relationship between this practice and articles 12, 13, 14, and 3 of the CRC. Thus, in the context of our research, we ask ourselves: what contributions can the Philosophy of Childhood bring to listening to children's voices? And, regarding this listening, what specific questions does the Philosophy of Childhood bring to the table?

the condition of listening to children's voices

From a variety of critical perspectives on childhood (Matthews, 1994; Kohan, 2014; Murris, 2016; Kennedy, Brahler, 2017), we return to the concepts of adultism and ageism as biases that accentuate intergenerational injustices, denying political involvement to certain individuals based on their chronological age and excluding them from the privilege of having a voice and exercising effective participation in their environment (Nishiyama, 2017; Rollo, 2020). Furthermore, we reject a formalist, developmental and futuristic perspective of early childhood education in which philosophy is often instrumentalised as a tool to refine certain social and cognitive skills.

We believe that philosophy - and in particular the Philosophy of Childhood - needs to be placed alongside the unpredictable experience of children as subjects and citizens who are present (Haynes, Murris, 2009). Valuing the contributions of children to today's society on the basis of who they already are provides us with a truer understanding of “participation” (Lundy, 2015). Therefore, the challenges are primarily political. Could this situation be mitigated if political spaces themselves were reconfigured to accommodate different ways of speaking? What relationships can be established between listening to children and political participation?

the place of children's political participation in public space

It seems odd to us that, in childhood contexts, especially in some educational, ethical or even religious environments, we accept that children have a voice, but we do not easily understand them as subjects of competent political action.

In fact, very early on children are held accountable for their ethical actions, expected to conform to societal norms that dictate who is considered a person with good character, via either positive reinforcement, punishment or surveillance. The same is true even when children are considered to be spiritual or religious subjects and granted access to initiation rites that introduce them from an early age to such experiences. But for now, we will set this aside to consider the child as a political subject: either by barring them from the exercise of basic rights such as choosing their representatives through voting, or by excluding them from discussions and debates in which they could express their voice and construct their own positions. Is the political participation of children desirable? What do we do with what children tell us, express, reveal, suggest, demand?

We return to the epigraph of our text. “Research is not about enumerating situations, but making researchers lose sleep”: are we prepared to listen to children's voices? Is it possible to listen to what children say to us without our own thinking taking over? Can political participation be a threshold upon which children can only stand, but never cross, as was once the case for Black people, Indigenous people, and women? How are the arguments that leave children on the fringes of political participation similar to those that have been employed for other human diasporas (women, Indigenous people, workers)?

The main ICPIC meeting was in 2022 in Japan. Japan and (name to be completed after the blind review process) have, at least, one thing in common: they are archipelagos. These geographic locations inspire us to use the image of the sea, the beach and the waves in our reflection. Could a coastline be a metaphor for children's political participation?

we invite you to read a creative illustrated9 narrative to keep you awake

Let us imagine the “territory of political participation” as being guarded by a sentry in a watchtower on the coast. A wanderer strolls along the beach, at times approaching the sea, at times retreating from it. The two of them have a chat10.

Wanderer - What are you doing on top of that tower? Where are you looking? What are you watching?

Sentry - I am charged with the illustrious task of preventing certain waves from intruding upon the territory of participation. I am the keeper of one of the borders of political participation.

Wanderer - Borders of political participation? Why does participation have boundaries? Whose interests are served by the creation and maintenance of such borders?

Sentry - Every territory has borders, a dividing line between inside and outside. A territory is not a space intended for freedom of movement and neither is political participation. There are those who can and those who cannot, for various reasons and motives, based on criteria that determine who can legitimately do so.

Wanderer - What reasons and motives can you offer that justify this hindrance to political participation? Is it even possible to talk about political participation if it is not a space of free movement, with no exclusionary criteria? Would there be sentries if borders did not exist? Would there be borders if there were no sentries? Or, do borders exist because sentries exist?

Sentry - Of course there are preconditions for political participation. There have always been, and over time, some have been changed. But political participation is not intended for everyone. It is necessary to meet certain conditions that vary according to space, time, age, maturity, gender, ethnicity, income and merit: a sort of passport, or visas, that open borders to voice.

Wanderer - What does it mean to be outside or inside the territory of political participation? Is it possible that political participation is not, in fact, a territory? As though political participation were a space, a plane where borders are redefined and, with them, the movement of deterritorialization and territorialization. On this plane, we reconfigure who can or cannot have an active voice that intervenes. Who is within or outside the borders, and in what ways one can be within or outside. Is it possible that rather than existing as a clearly marked area that someone owns, it is actually a territory without frontiers? And can there be territory without constant deterritorialization and reterritorialization (Deleuze & Guattari, 1992)?

Sentry - Attention Wanderer, I see big waves approaching the territory of political participation. We need to make sure they have permission to enter, to participate.

Wanderer - Is it possible to stop a wave? How? Are all not accepted in the territory of political participation? Why not? What is the point of letting some in and keeping others out? Who decides?

Sentry - Wait! I see C.H.I.L.D.R.E.N!!! Danger. They will definitely have to stay on the beach; they cannot enter the territory.

Wanderer - Danger?! Why? We were all kids once! And what happened when we were kids? What memories do we have from our childhood? Did we have freedom of expression? Did we feel welcomed? Were our voices taken into account?

Sentry - We were children; you said it well. A developmental stage, a journey towards becoming adults. Now that stage has passed… fortunately!

Wanderer - Fortunately??? Do we lose our childhood when we are no longer children? Will there be room for childhood in adulthood? Could it be that when we welcome the voices of children, we welcome and are also welcomed?

Sentry - Welcoming why and to what purpose? It is adults who have the duty to protect children, not the other way around.

Wanderer - To what extent can listening to children's voices be a way to protect children? Can the political participation of children open the doors to our own childhood? And give origin to new forms of polis?

Sentry - Creating new forms of polis with children's participation? They are still minors. Only people who have reached the age majority may enter the territory of political participation.

Wanderer - Why? What happens at the instant we reach the age of majority? Which border is that? Why are we afraid to let children in? What is it about children's participation that makes others tremble?

Sentry - Why consider what they say if age tends to go hand in hand with maturity? They are not up to this challenge.

Wanderer - And does maturity necessarily go hand in hand with age for adults? Are adults a model of maturity?

Sentry - Not necessarily, but children, due to their immaturity, inexperience, innocence, to name only a few11, are a very easy target for manipulation, and we must remain alert to this. I believe this is what paragraph 1 of article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child is saying: "Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child"12.

Wanderer - Is this the only way to interpret article 12? Can we not see it as a requirement placed upon adults? In other words, article 12 demands that we listen and pay attention to children's voices and assign value to the polyphony of their voices at any age. Valuing the contributions of all ages cultivates intergenerational justice! One cannot "sacrifice the present potential of children"13.

To what extent can the Convention on the Rights of the Child not serve as a sort of sentry? Could it be a window to protect children from the arbitrariness and authoritarianism of adults? Not a new form of territorialization, but a space to guarantee freedom, dignity! Are adults up to the challenge of promoting and safeguarding children's rights?

Sentry - It is necessary to protect the territory from the political participation of those who are neither knowledgeable nor mature, such as children. Requirements are necessary: information, rationality, reasonableness, critical spirit. Imagine, Wanderer, what if children could vote or choose our rulers? Imagine if this participation for children were to become a widespread trend. It would be like a tsunami! It could be the end of the world as we know it. Giving a children a say in things? Where has this ever been done before?

Wanderer - “Requirements”, you say… Are these requirements guaranteed to be met in adulthood? Do all adults meet them? Perhaps it would provide us with an opportunity for freshness, new ideas, beginnings and new beginnings. By welcoming their worlds, we would encounter new worlds, unimaginable worlds!

Sentry - What if these waves destroy what we have built? Isn’t this path certain to lead us into a swamp or some kind of whirlpool that would turn everything upside down? These rather romanticized ideas have a touch of poetry and beauty. They sound very nice, but…

Wanderer - What have we built? Spaces that are far from being truly child-friendly? Spaces where their voices tend not to be considered in many or almost all matters that concern them? Spaces with innumerable barriers to their participation? An "intensive exchange between children and adults on the development of policies, programmes and measures in all relevant contexts of children's lives"14 is urgently needed.

Meanwhile, the waves of children spread, oblivious to the conversation between Sentry and Wanderer. As if riding on a wave, children's voices invade the seafront where the conversation is taking place. They stay there. They spread. Some people hear them from afar, others from nearby. Some with condescending smiles, others in silence. Some are attracted by the magnet of childhood, others retreat from the fatigue of joy and play.

The beach is like the border of the territory and the more-or-less forced meeting place with the waves. In a way, the stronger the waves, the stronger the resistance, the greater the fear of their impact. But the beach is also for stretching out, diving, swimming in the waves. Can the beach be the frontier of listening? Can it be on the edge of listening? Can it be the eavesdropper on the shore?

Sentry - Look, Wanderer, there are children building sandcastles. Some adults are with them. Why build sandcastles? The waves will destroy them: no sooner are they built than they disappear. And then it's time to start over, a game of beginnings, as if there were neither yesterday nor tomorrow, only now. It's a waste of time!

Wanderer - Maybe this time will not be wasted, maybe this is the time needed to territorialize and deterritorialize the political space itself. Otherwise, what do we do with the children? With their voices? With what they have to tell us? Are we not going to let them into the territory of political participation? It doesn't seem possible, let alone desirable, to leave out the children! This is also their space! It's a common space! It's the space of humanity! We cannot deny them access!

Sentry - So let's create spaces for children. Let's create castles where children can live. They will be safe places, places that fit their abilities. They cannot participate in everything because it would not be safe for them. This way we will be able to create safe spaces for children to make themselves heard: school, legal frameworks, leisure time, children's and youth associations, philosophy in every classroom. Under the protection and guidance of adults.

Wanderer - Very well, that's something. But is this the way we really listen to children? How can we say that these spaces created by adults aren’t still ways of confining children's voices? Are they not still ways of co-opting and silencing them (Kohan, 1999, pp. 69-70)? Are these spaces a territorialization and colonization of children within the territory of participation? What about the study and research groups on children that don’t include any children? What about adult conversations about children without any children? Will new sentinels be needed? Let’s create more and more polyphonic spaces for dialogue with children and between children, spaces to think philosophically about existence, spaces and times to be more human!

Sentry - Utopias! This is more of a utopia.

Wanderer - Who knows? Utopia, like the non-place, makes possible the discomfort inherent to the construction of something new. Utopia as a future for an emergent space and time that is collectively composed, regardless of conditions. The non-place as a real presence and not as a wait (Levitas, 2013, p. 214). Is this the challenge and fear that the waves of children cast upon us? The non-place is the possibility of all places. It is only impossible until it becomes possible.

The Wanderer approaches the children to welcome them. In a space and time of listening, everyone is immersed in the living and life-giving dynamics of the dialogues; in polyphonic movements of self-knowledge and construction of new forms of polis: poli(s)phonies.

How does childhood philosophy challenge itself in creating poli(s)phonies, where children's participation sets the tone?

In what ways does the Philosophy of Childhood challenge us to create poli(s)phonies?

***

Convidamos à leitura de uma narrativa criativa ilustrada15para não adormecer

Imaginemos o “território da participação política” guardado por uma sentinela que se encontra numa torre de vigia na orla costeira. Por ali passeia-se um andante na praia, ora aproximando-se do mar ora correndo a afastar-se dele. Os dois conversam16.

Andante - O que fazes no alto dessa torre? Para onde olhas? Que vigias?

Sentinela - A mim cabe-me a ilustre tarefa de impedir que certas ondas possam invadir o território da participação. Sou o guardador de uma das fronteiras da participação política.

Andante - Fronteiras da participação política? Porque existem fronteiras à participação? A quem interessa a criação e manutenção de tais fronteiras?

Sentinela - Todo o território tem fronteiras, limites entre o dentro e o fora. Um território não é um espaço de livre circulação e a participação política também o não é. Há os que podem e os que não podem. E podem-no ou não por diferentes razões e motivos. Essas razões são mantidas com base em critérios legitimadores.

Andante - Que razões e motivos se podem aduzir para impedir a participação política? É possível falar-se em participação política se esta não for um espaço de livre circulação, sem exclusões? Sem fronteiras não haveria sentinelas, ou sem sentinelas não haveria fronteiras? Ou há fronteiras porque há sentinelas?

Sentinela - É claro que há condições de participação política. Sempre as houve. Algumas foram sendo mudadas. Mas a participação política não é para todos. Há que verificar a existência de certas condições que variam com o espaço, com o tempo, com a idade, com a maturidade, com o género, com a etnia, com rendimento económico, com o mérito: uma espécie de passaportes e vistos que abrem as fronteiras à voz.

Andante - Quais os sentidos de ficar fora ou dentro do território da participação política? Seria possível que a participação política não fosse um território? Como se a participação política fosse um espaço, um plano onde as fronteiras se redefinem e, com elas, o movimento de desterritorialização e territorialização. Neste plano, vai-se reconfigurando quem pode ou não ter uma voz ativa, interventiva. Quem está dentro ou fora das fronteiras e de que modos se pode estar dentro ou fora. Será possível que não se configure enquanto área delimitada na posse de alguém, mas seja antes um lugar aberto, sem fronteiras? E haverá território sem desterritorialização e reterritorialização constantes (Deleuze & Guattari, 1992, p. 58)?

Sentinela - Atenção Andante, vejo grandes ondas a aproximarem-se do território da participação política. É preciso assegurarmo-nos que têm a permissão para entrar, para participar.

Andante - É possível parar uma onda? Como? Nem todas as pessoas são aceites no território da participação política? Porquê? Qual o sentido de umas entrarem e outras não? Quem decide quem participa?

Sentinela - Espera são C.R.I.A.N.Ç.A.S!!! Perigo. Estas, definitivamente, terão de ficar na praia, não podem adentrar no território.

Andante - Perigo! Porquê? Já todos fomos crianças! E o que aconteceu quando éramos crianças? Que memórias temos da nossa infância? Tínhamos liberdade de expressão? Sentimo-nos acolhidos? Eram as nossas vozes tidas em conta?

Sentinela - Fomos crianças, disseste bem. Uma fase de desenvolvimento, um trânsito para chegarmos a adultos. Agora essa fase já passou… felizmente!

Andante - Felizmente??? Será que quando já não somos crianças, perdemos a nossa infância? Haverá lugar para a infância na idade adulta? Será que ao acolhermos as vozes das crianças, também nos acolhemos e somos acolhidos?

Sentinela - Sermos acolhidos? Porquê e para quê? São os adultos que têm o dever da proteção das crianças e não o inverso.

Andante - Em que medida a escuta das vozes infantis pode ser uma forma de proteção das crianças? Pode a participação política das crianças abrir as portas da nossa infância? E originar novas formas de polis?

Sentinela - Criação de novas formas de polis com a participação das crianças? Elas ainda são menores de idade. No território da participação política só entram pessoas com maioridade.

Andante - Porquê? O que acontece no instante em que se atinge a maioridade? Que fronteira é esta a da maioridade? O que tememos com a entrada das crianças? O que faz tremer a participação das crianças?

Sentinela - Para quê ouvi-las e ter em consideração o que dizem, se a idade tende a andar de mãos dadas com a sua maturidade? Não estão aptas para esse desafio.

Andante - E andará a maturidade, necessariamente, de mãos dadas com a idade no caso dos adultos? Serão os adultos um modelo de maturidade?

Sentinela - Não necessariamente, mas as crianças, pela sua imaturidade, inexperiência, inocência, só para mencionar algumas17, são até um alvo muito fácil de manipulação ao qual devemos estar alerta. Julgo ser esta uma das intenções do n.º 1 do artigo 12º da Convenção sobre os Direitos da Criança: “Os Estados Partes garantem à criança com capacidade de discernimento o direito de exprimir livremente a sua opinião sobre as questões que lhe respeitem, sendo devidamente tomadas em consideração as opiniões da criança, de acordo com a sua idade e maturidade”18.

Andante: Será esta a única forma de olhar para o artigo 12.º? Não poderemos pensar que se trata de uma exigência para os adultos? Dito de outra forma, o artigo 12.º exige que escutemos e atendamos as vozes das crianças e valorizemos a importância da polifonia das vozes infantis em qualquer idade. Ao valorizar os contributos de todas as idades cultiva-se uma justiça entre gerações! Não se pode “sacrificar o potencial presente das crianças”19.

Em que medida a Convenção sobre os Direitos da Criança não será uma espécie de sentinela? Poderá ser uma janela para proteger as crianças da arbitrariedade e autoritarismo dos adultos e não uma nova forma de territorialização, mas sim um espaço de garantia de liberdade, de dignidade! Estarão os adultos aptos para o desafio de promoção e salvaguarda dos direitos das crianças?

Sentinela - É necessário proteger o território da participação política daqueles que não têm conhecimento nem maturidade, como é o caso das crianças. São necessários requisitos: informação, racionalidade, razoabilidade, espírito crítico. Imagina, Andante, o que seria se as crianças pudessem votar ou escolher os governantes? Imagina que pegava a moda da participação das crianças. Seria como um tsunami. Poderia ser o fim do que estamos habituados. Onde já se viu, crianças a terem voto na matéria.

Andante - “Requisitos”, dizes tu… Esses requisitos estão garantidos na idade adulta? Todos os adultos os cumprem? Talvez fosse uma oportunidade de frescura, novas ideias, de inícios e recomeços. Ao acolhermos os seus mundos, conheceríamos novos mundos, mundos inimagináveis!

Sentinela - E se essas ondas vierem destruir o que construímos? Caminho seguro para cairmos num pântano ou, então, uma espécie de redemoinho que voltaria tudo de pernas para o ar. Ideias mais ou menos romantizadas que têm um quê de poesia e beleza. Isso é tudo muito bonito, mas…

Andante - O que construímos? Espaços que estão longe de serem verdadeiros amigos das crianças? Espaços onde as suas vozes tendem a não ser levadas em consideração em muitos ou em quase todos os assuntos que lhes dizem respeito? Espaços com inúmeras barreiras à sua participação? É necessário um “intenso intercâmbio entre crianças e adultos sobre o desenvolvimento de políticas, programas e medidas em todos os contextos relevantes da vida das crianças”20.

Entretanto, a onda de crianças espraia-se alheia à conversa entre Sentinela e Andante. As vozes infantis invadem, como que em onda, a orla marítima onde decorre a conversa. Ficam por ali. Espalham-se. Algumas pessoas ouvem-nas de longe, outras de mais perto. Umas com sorrisos de condescendência, outras em silêncio. Algumas aproximam-se atraídas pelo íman da infância, outras afastam-se da canseira da alegria e da brincadeira.

A praia é como a fronteira do território e o espaço de encontro, mais ou menos forçado, com a onda. De certa forma, quanto maior a força da onda, maior a força da resistência à onda, maior o medo do impacto. Mas a praia é, também, o espraiar-se, o mergulhar-se, o banhar-se na onda. Pode a praia ser a fronteira da escuta? Ser a margem da escuta? Ser a escuta na margem?

Sentinela - Olha, Andante, lá estão as crianças a construir castelos na areia e alguns adultos com elas. Para quê construir castelos na areia? As ondas destruí-los-ão: construir para logo desaparecer. E toca a recomeçar, uma brincadeira de inícios, como se não houvesse nem ontem, nem amanhã, somente agora. É uma perda de tempo!

Andante - Talvez não se perca esse tempo, talvez esse seja o tempo necessário da territorialização e desterritorialização do próprio plano político. Senão, o que fazemos com as crianças? Com a sua voz? com o que nos têm para dizer? Não as deixamos entrar no território da participação política? Não me parece possível e, muito menos, desejável, deixar de fora as crianças! Este também é o seu espaço! É um espaço comum! É o espaço da humanidade! Não podemos vedar-lhes o acesso!

Sentinela - Criemos, então, espaços próprios para as crianças. Criemos castelos onde as crianças possam habitar. Serão lugares seguros e próprios para as suas capacidades. Elas não podem participar em tudo porque não seria seguro para elas. Assim, poderemos criar espaços seguros para as crianças se fazerem ouvir: escola, quadros legais, ocupação de tempos livres, associações infanto-juvenis, filosofia em todas as salas de aula. Sob a proteção e orientação dos adultos.

Andante - Muito bem, já é alguma coisa. Mas será esta a forma de realmente escutarmos as crianças? De que modos estes espaços criados por adultos não são modos de confinamento das suas vozes? Não são ainda formas de as cooptarmos e silenciarmos (Kohan, 1999, pp. 69-70)? Serão estes espaços uma territorialização e colonização das crianças dentro do território da participação? E os grupos de estudo e de pesquisa sobre as crianças e sem as crianças, e os colóquios de adultos sobre as crianças e sem as crianças? Serão necessárias novas sentinelas? Sejam, sim, criados mais e mais espaços polifónicos de diálogo com crianças e entre crianças, espaços para pensar filosoficamente a existência, espaços e tempos para se ser mais humano!

Sentinela - Utopias! Isso é mais uma utopia.

Andante - Quem sabe? A utopia, como o não-lugar, possibilita o desconforto próprio da construção de algo novo. Utopia como um futuro de espaço e tempo emergentes que se compõe coletivamente, independentemente das condições. O não-lugar enquanto presença real e não como uma espera (Levitas, 2013, p. 214). Será esse o desafio e o medo que a onda das crianças nos lançam? O não-lugar é a possibilidade de todos os lugares. Só é impossível até se tornar possível.

O Andante aproxima-se das crianças acolhendo-as. Num espaço e num tempo de escuta, todos emergem nas dinâmicas vivas e vivificantes dos diálogos, em movimentos polifónicos de autoconhecimento e construção de novas formas de polis: poli(s)fonias.

***

The Greek term polis is well known and commonly translated as city-state. The Greek city-state is a place where a multiplicity of people are located within a closed space: a delimited territory. According to Aristotle, the human being is a naturally political animal, and the polis would be his natural space, a community space where he is constituted as a citizen. The citizen human being is distinguished from other animals not only because he has a voice, but because he has a voice that is capable of creating meaning through speech. According to Aristotle, the logos puts the human being in the position of an animal that creates meaning for everything it perceives (Aristotle, 1252a27). So, it is precisely discourse that allows human beings to assume the role of political beings.

The Aristotelian polis demands criteria of participation, criteria of citizenship. These criteria build a certain identity among citizens and, in this way, throw those who do not fit them onto the margins. This means that the polis is constituted as a territory of political participation, where some voices are considered and others are not. There are voices that have power - like those of free, adult, male human beings, sons or daughters of an Athenian father or mother - and others voices are silenced or not listened to, as if the failure to listen were a fence, a border, an impediment to participation.

If on the one hand, logos is a condition and criterion of aggregation, on the other it is a condition of exclusion. The political nature of the logos is thus an attribute that belongs only to certain human beings through the possibility of belonging to the polis. Thus, the logos is held in common, but it does not give rise to an authentic and comprehensive political community. The polis is, in a way, a community of relations of discourses, of meanings, a phone semantik where what matters will be the meanings of what is spoken within a rational structure organized according to certain logical principles (Cavarero, 2005, p. 188). The human being is not political because he speaks, but because he creates discourses, that is, he narrates through language. This logoic dimension of speech is perhaps the main characteristic of the human being of the polis, since it creates the community and is a natural state, according to the Aristotelian perspective. The commonality of the polis among free and equal individuals is precisely a communicative rationality of a language that binds them to procedural norms. In this way, a linguistic community of the most suitable is created, of course. Women, foreigners and slaves, for Aristotle, were not considered citizens of the polis. Nor were children.

Echoing a cultural reality and question - "Is childhood disappearing?" - David Kennedy (Kennedy, 2020), argues for a new adult-child political relational paradigm, listing some vicissitudes of historical dialectics that present the child as a marginalized subject, as property, as economically deprived, as ontological other, as epistemically incomplete, as excluded from culture, as a special case of the marginalized other. In light of this, the author calls for a needed historical change, although he recognises that this will not be linear.

In addition, Karin Murris21, questioning certain representations of childhood, denounces prejudices such as adultism and idadism, structured in dichotomies (body/mind; nature/culture) and typical of Western humanist ontology and educational theories that view childhood as a lesser stage of human development and sustain unequal power relations between adults and children through a logic of children’s subordination and discrimination. Murris argues that the theory and practice of Philosophy for Children, and the Philosophy of Childhood can make a decisive contribution to the epistemological and ontological valorisation of children and, inherently, their voice in a participatory understanding of democracy.

David Kennedy (Kennedy, 2020) also contends that philosophical questioning and common dialogue between children and adults can hold the concrete hope for social reconstruction through the dialectical reconstruction of the adult-child relationship. Along these lines, our dialogue between Sentinel and Wanderer served as a metaphor through which to think about the space where children's voices can exercise political participation. The borders and the sentinels that guard them do not negate the existence of these voices, but only relegate them to a marginal space, a space imagined as non-political.

Today, the issue of children's voices is on the agenda and can be found in all sorts of contemporary conversations. Article 12 of the CRC is one example of this. On the one hand, voice has become the object of a variety of studies employing a nearly unlimited number of interpretative perspectives. On the other hand, the specificity or uniqueness of voices has received far less attention (Cavarero, 2005, p.8). Why do we so resist children's political participation in the public sphere? For example, we should listen to the voices that Greta Thunberg mobilized and what they say22. Waves of political participation and activism that certain adult voices try to silence with arguments citing their supposed immaturity, innocence, unpreparedness, or special educational needs23. What is so dangerous about Greta Thunberg's movement? Why does it generate so much resistance? Waves approaching and breaking on beaches defended by sentinels? How can a wave be stopped? Perhaps this is Thunberg was invited to testify before the European Commission when it was drafting a bill whose goal was to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, within the framework of the European Green Agreement. It was an attempt to frame, maybe even capture, the wave of political participation that Greta Thunberg embodies24.

What we propose through our writing exercise is to reflect on what political contribution these infantile polyphonies that already inhabit the world we live in will have and what other forms of polis might follow from this. We call this a construction of poly(s)phonies.

What is the role of children's voices in these poly(s)phonies? The leap from a silenced, but not silent, presence of children's polyphonies to the recognition of their political role is at the heart of the dialogue between Sentinel and Wanderer.

What challenges does the political participation of children pose for the philosophy of childhood? And what challenges can the philosophy of childhood pose to the political participation of children? To what extent can a space and a time for listening to children open up polyphonic movements and make possible the construction of new forms of polis: poly(s)phonies? In what ways does the philosophy of childhood challenge itself through the creation of poly(s)phonies where children's participation sets the tone? In what ways does the Philosophy of Childhood challenge us to create poly(s)phonies?