the polylogical process model of (elementary-)philosophical education: an interdisciplinary framework that embeds P4wC into the constructivist theory of conceptual change/growth

p4wc discourse

A significant number of international studies show the positive effects of P4wC on the cognitive, social and emotional development of children (Lipman, Bierman, 1980a; Haas, 1980; Williams, 1993; Sasserville, 1994; Fields, 1995; Sigurborsdottir, 1998; Trickey, Topping, 2004; Trickey, 2007; Fair, Johnson, Haas, Price, 2015; Helzel, 2018; Karadag, Demirtas, 2018).

UNESCO points out four key competences P4wC provides for children: first, the practice of independent thinking; second, knowledge of citizenship; third, the linguistic competences of speech and debate; and finally, the general positive effects on children’s personality development. Thus, P4wC can also be viewed as a democratic model of elementary education (n.d., p. 36).

Nonetheless, critics often point out that the academic foundation of P4wC is in need of further development, as seen in Stephan Englhart (1997) and Michael Niewiem (2001). In my opinion, an interdisciplinary approach is necessary to achieve a broader academic foundation, and I agree with Englhart who demands an interdisciplinary theory based on psychological and pedagogical concepts.

My PPEE model aims at meeting this demand by creating an interdisciplinary approach to implement philosophizing with children and teenagers. Such a concept would add some impulses both in terms of the practical implementation of P4wC as well as in facilitating the comparison of research results in an international context.

The idea to provide an interdisciplinary approach goes back to Englhart’s recommendation that P4wC concepts should be extended in the light of pedagogical and psychological findings. Following empirical research could prove the success of P4wC in a broader context (1997, pp. 175-178). Englhart concludes that one of the biggest problems of children’s philosophy is the missing interdisciplinary exchange (1997, p. 189).

Ever since Englhart’s claims, some interdisciplinary projects on P4wC have already been worked on. However, as far as I know, none of them has tried to synthesize philosophical, psychological and pedagogical findings in a single framework that also includes the main criticisms of P4wC.

The main problem is that, internationally, the comparability of scientific studies on the issue is complicated by the diversity of various P4wC approaches, as can be seen in Englhart (1997, p. 185-186), Maughn Gregory (2017, p. 210) and Kerstin Michalik (2018, p. 27). This multitude of P4wC concepts makes a well-grounded academic criticism extremely difficult, which is why Gregory underlines the importance of using Lipman’s original concept:

[...] this diversity presents several challenges to the P4C movement, perhaps the most important of which is the difficulty of comparing the relative merits of different approaches. (2017, p. 210)

In consideration of Gregory’s idea, I suggest to combine Lipman’s original P4C approach with my PPEE model. This would support Lipman’s P4C concept while strengthening it with new philosophical, psychological and pedagogical considerations.

If future P4C and PwC approaches follow this lead in connection with the conceptual change/growth theory, it would make international studies more comparable in terms of the interdisciplinary thoughts I offer in this article. This, in turn would help to simplify and clarify this multi-faceted discussion.

One other issue that Englhart points out and which remains unresolved is the refusal of some critics to acknowledge the diversity of the P4wC movement (1997, p. 185-186). Caroline Heinrich (2017, 2020a, 2020b), for example, does not point out which specific P4wC approach she criticizes. As there is a wide range of P4wC modifications, my suggestion is to give them a linking element (the PPEE model) which offers better comparability for international studies and would give critics the tool to be more precise.

In order to build an appropriate interdisciplinary foundation, I would consider the ideas of constructivism, especially the conceptual change/growth theory of Stella Vosniadou and William Brewer (1992). Constructivist ideas already have an interdisciplinary focus, as they combine the fields of pedagogy, psychology, philosophy, and sociology, as Kersten Reich (2006, p. 83) points out. The natural connection between the constructivist learning theory and its practical implementation is one of the main reasons why I suggest combining P4wC with the constructivist approach.

My interdisciplinary PPEE model tries to give some initial ideas for such a course. It has been developed along three major research areas: First, the question of whether philosophizing with children can actually be called philosophy. Second, the question of whether children do really have the cognitive abilities to engage in philosophical discourse. Third, the question about which scientific pedagogical considerations could be added.

can philosophizing with children actually be called philosophy?

Since philosophy is usually associated with extremely complex thought processes that can only be accomplished by adults, the debate about whether philosophizing with children can actually be called philosophy is still to be found in the literature.

Heinrich (2017, 2020a, 2020b) for example argues that P4wC is “an assault on philosophy and an assault on children” because children have the right not to understand certain things (2017, p. 163). She concludes that adults try to see children’s statements in a philosophical way and this satisfy their own need for reflection through children. Therefore, P4wC is “an imposed concept from adults on children” (“Übergestültptes Konzept von Erwachsenen auf Kinder”) which she strictly refuses to call philosophy (2020a, p. 35).

Going back to Lipman's original P4C concept, I suggest that he understood it as an encouragement for children/teens to think for themselves. Heinrich’s positioning on P4wC could be contradicted by following Lipman’s argumentation. He criticized the US school system of the 1970s for declassing children as objects of knowledge transfer. An imposed teaching concept as Heinrich ascribes, was not Lipman’s intention: “What the teacher must certainly abstain from is any effort to abort the children’s thinking before they have had a chance to see where their own ideas might lead” (1980b, p. 45). Lipman states: “The conception of the educated child as a knowledgeable child will have to give way to one in which the educated child is conceived of as knowing, understanding, reasonable and judicious”(1994, p. 66).

The question “But is it Philosophy?” is one the international philosophy café also deals with. Michael Picard (2015), who claims to have no P4wC background, points out that some P4wC concepts still have to clarify more accurately why they can relate their specific concept to the field of philosophy. He also praises the Vancouver Institute of Philosophy for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children as a good model because they developed a five-step program to legitimate P4wC as an assignment in philosophy. Picard however, indicates that other P4wC concepts still have to focus on this question more closely (2015, p. 166-167).

In recent decades, there have been several positions concerning the question of whether P4wC can be placed in the field of philosophy. Barbara Weber and Susan Gardner (2009), for instance, argue that by philosophizing with children we use the Socratic method which was developed by Socrates who clearly was a philosopher (2009, p. 26).

Other main positions state that P4wC can be called philosophy because of 1) its philosophical topics, 2) its philosophical methods, and 3) its philosophical questions that, in turn, need philosophical considerations. This includes the demarcation from other forms of discussion.

Furthermore, it is necessary to specify the distinction between the term ‘philosophy’ and the term ‘philosophizing.’

Let me start with (1) its philosophical topics: P4wC distinguishes itself by the topics that have been discussed throughout the history of philosophy, such as justice, happiness, obligation, freedom, and responsibility. Lipman et al. underline this by referring to the philosophical discourses on the unsolved existential questions that have been discussed since ancient times (1980b, p. 25). According to Lipman et al., philosophical questions asked by children are generally related to the disciplines of Logic, Metaphysics, or Ethics (1980b, p. 36).

Let me now move to (2) its philosophical methods: yy practicing P4wC, children use philosophical methods. Lipman, Sharp and Oscanyan name, e.g., thought experiments (1980b, p. 65).

Next (3), we have to distinguish between philosophical and non-philosophical questions and discussion: As we all know, Lipman wrote that “Children begin to think philosophically when they begin to ask why” (1978, p. 35). Englhart (1997, p. 66) and UNESCO (n.d., p. 37) counter that this does not suffice to call it philosophy. But if you read Lipman, Sharp and Oscanyan closely, their argumentation goes on by saying that there are two forms of why-questions. One that asks for causal explanation, children want to know explanations of phenomena, e.g., why fire burns. On the other hand, there are why-questions that want to determine a purpose, e.g., why do we have bridges over a river. Some why-questions can be seen as “wondering at the world” and as starting points of philosophical considerations (1980b, p. 58-59). Lipman, Sharp and Oscanyan also argue that one can only talk of a philosophical discussion when it leaves the personal and moves on to the general, abstract level. Lipman et al. stress here that a personal issue can be a starting point for a philosophical discussion (1980b, p. 17), but they warn against turning it into a therapeutic conversation. Instead, topics should be discussed on a meta-level (1980b, p. 90-91).

In addition, Lipman, Sharp and Oscanyan remind us that one must distinguish between scientific, religious, and philosophical discussions, clarifying that by saying that “from an educational point of view, scientific discussion and religious discussion are separate things and should not be confused with philosophical discussion” (1980b, p. 108).

Topics of the natural sciences are based on facts and can be empirically proven. Religious beliefs usually remain unquestioned. A philosophical discussion is usually based on a reflection of personal assumptions (1980b, p. 106-107). Therefore, according to Lipman, philosophical discussion takes over where natural scientific and religious discussions leave something open, (Lipman et al., 1980b, p. 104).

Let us now turn to the next point, which deals with the distinction between ‘philosophy’ and ‘philosophizing’. A differentiation of both terms is necessary according to Karen Murris (2000) and Niewiem (2001). In the German discourse, this debate was already started in the 1980s by Barbara Brüning (1985, p. 8-30), and it was later taken up by the American discourse of children´s philosophy as well. To quote Murris:

The debate continues but is often complicated by the confusion between “doing” philosophy as a subject - that is, studying the ideas of the world’s great thinkers since the Greeks - and “philosophizing”, thinking about any question in a philosophical way. The debate is complicated further by disagreement over what the term “philosophy” means. (2000, p. 261).

Therefore, UNESCO recommends establishing an appropriate term concerning philosophy with children based on their level of development and even demands a new definition of the term philosophy (n.d., p. 37). For this demand Lipman (1984) already suggested that we think of philosophizing with children in terms of a broader definition of philosophy. Lipman talked about various philosophical styles, and one is specifically tailored to children (1984, p. 3-4). Ekkehard Martens (2017), e.g., compares it to the different levels in sports. We have people who practice sports on an amateur level and others who do it as professionals. This can be transferred and compared with non-professional philosophers and professional academic philosophers (2017, p. 23).

Let me now give you my position on the question of whether P4wC can be placed in the field of philosophy: from my point of view, P4wC can be considered a model of early encouragement to philosophize on an elementary level and a kind of “proto philosophy” that prepares young learners for a future engagement with academic philosophy or just simply for life.

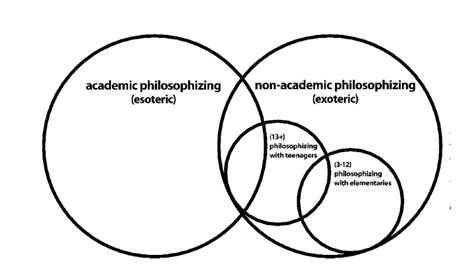

Englhart (1997, p. 190) and Murris (2000, p. 267) also see P4wC as an early form of doing philosophy and a bridge to adult philosophy. Even Richard Kitchener (1990) who criticizes P4wC partly approves of this idea, but he asks for a more precise wording (1990, p. 75), since, according to him, critical thinking does not necessarily equal philosophizing (1990, p. 68). Kitchener recommends the classification of P4wC as a preform of concrete philosophizing that must be distinguished from academic philosophizing. Brüning also distinguishes between academic (esoteric) philosophy and non-academic (exoteric) philosophy and places P4wC in the non-academic field (1985, p. 3). Kitchener goes on by saying that these two fields show some family resemblance, which is why he approves of calling it philosophizing (1990, p. 74).

With regard to Kitchners’ “family resemblance” I would like to refer to Ludwig Wittgenstein (2006 [original 1953]), who was a member of the “Viennese circle” (“Wiener Kreis”). In his linguistic-philosophical approach, he states that our thoughts are determined by language, which can lead to confusion, if terms are unclear. As an example, he mentions the word for “games”: there are board games, card games, and battle games, which are all types of games but have few apparent similarities (2003, p. 247-248). I believe that philosophizing with children can be understood in a way similar to Wittgenstein’s concept of “family resemblance” (“Familienähnlichkeiten”): certain points are already comparable to academic philosophizing and others need to mature and be further developed first.

Let us compare that to early mathematical or musical education. It is obvious that children are not professional musicians, nor are they mathematicians, but we can give them early encouragement by teaching them the appropriate basic skills. To quote Murris: “After all, primary school children do not ‘do‛, for example, mathematics or history as capably as professional mathematicians or historians. Does it, therefore, follow that either they do not engage in ‘real‛ mathematics or ‘real‛ history, or that they should not do those subjects?” (2000, p. 263)

All those considerations have given me the idea of placing P4wC in an overlapping structure between academic (esoteric) philosophizing, as seen in the left circle, and early educational (exoteric) philosophizing, as seen in the right circle.

Figure 1: positioning philosophizing with elementary students and teenagers in the field of non-academic and academic philosophizing

Academic philosophizing is placed in the left circle and philosophizing outside academia is placed in the right circle. P4wC is generally centered in the field of non-academic philosophy. In addition, I suggest distinguishing between philosophizing with elementary students (3-12 years of age) and philosophizing with teenagers (from 13 years of age and up). As you can see, there are overlapping areas. The older learners become, the more overlapping with academic philosophizing can be found since the thought processes of teenagers become more and more complex, and texts of “great philosophers” can be part of their philosophical discussions.

This age differentiation should not be seen too strictly; it is meant to be taken as a guideline. To be clear, my suggested age differentiations do not ignore the fact that some young children can already reach a high intellectual maturity. In fact, it also depends on the quality of P4wC discussions that children and teens have already experienced or whether they have had a chance to be part of a P4wC discussion at all. Factors of socialization seem to play an important role in the cognitive development of children, as the next part of this article tries to show.

do children have the cognitive abilities to engage in philosophical discourse?

For a long time, critics of P4wC used Piaget’s theorem to show that children are not able to engage in philosophical discourse and this argumentation can still be found.

Kitchener (1990) can be named as one major critic in the past, and Heinrich (2017, 2020a, 2020b) is more recent. Both used Piaget to argue that children under the age of 12 are not able to philosophize.

Heinrich classifies P4wC as an ”ignorance concerning children’s thinking, questioning and play” (2017, p. 163-170; 2020b, p. 111-119). Piaget’s own critical positions concerning children and philosophy can be read in Heinrich’s anthology. It is highly interesting that Piaget himself also mentions that children around five years of age do already ask existential questions such as - “Who created the sun, earth and the air?” “Where does thunder come from?” (Piaget, 2020, p. 49 [original 1931]).

Concerning Gareth B. Matthews (1991, 1993) counter-arguments on Piaget’s theory, Heinrich argues that Matthews is not able to criticize Piaget and she blames Matthews disinterest in children’s thinking (Heinrich, 2020a, p. 32).

I firmly believe that the question whether children have the cognitive abilities to engage in philosophical discourse is an important one. But it must be discussed under the consideration of current psychological findings. Until now Piaget’s theory has almost been negated in the P4wC discourse, as Englhart (1997, p. 188) and Heinrich (2020b, p. 113) state. Therefore, I think that there is insufficient academic dispute concerning Piaget’s findings to come to a qualified academic conclusion on the topic.

I strongly believe that Piaget’s theorem with regard to P4wC must be analyzed with caution because his theory has been criticized and disproved by many. I would like to highlight the following critics: Let me begin with Beate Sodian (2012) who sums up that the cognitive performance of children cannot be displayed by using cognitive stages correlating with their ages because there is a bigger variability than Piaget claims. Furthermore, Sodian says that Piaget highly underestimates the cognitive performance of babies, toddlers, and children (2012, p. 390).

Let me now move on to the second critic, John Favell et al. (1977), who refute Piaget’s theory of children’s egocentrism. Favell et al. showed in various studies that four to five year-old children can put themselves in someone else’s position (in Sodian, 2012, p. 391-392).

Next, I would like to refer to David Cohen (2018) who shows that the ability to change perspectives can even be achieved by children who are about three years old (2018, p. 270). Instead of talking about stages, he suggests looking at cognitive development as overlapping waves (2018, p. 47-48). Marie-France Daniel and Mathieu Gagnon (2005) also demonstrated that children from an age of four can extend their abilities to think from an egocentric perspective to dialogical-critical thinking (2005, p. 77).

Finally, I would like to present the perspective of Ernst von Glaserfeld (2015, p. 83) and Cohen (2018, p. 422-423). They criticize Piaget’s model of stages, which was almost exclusively based on the results of research done on his own three children. They found that when testing larger groups or children of different cultures, Piaget’s assumptions could not be verified. Their main conclusion is that factors of socialization can either positively or negatively influence the cognitive development of children.

In my opinion, we also should not forget that Piaget’s children had no philosophical experience whatsoever before being researched. A lot of international studies done in the past 50 years show that children’s cognitive abilities rise in a measurable way by philosophizing. Steven Trickey (2007), e.g., showed that a person’s IQ rises because of early philosophizing about 6 points and has an enormous impact on developing children´s skills, especially when it comes to children who have no access to proper schooling (2007, p. 285). Furthermore, children benefit from the practice of philosophizing in many ways, even if they only had a one-year course in philosophy, as Trickey points out (2007, p. 260).

Thus, it is clear that the research on P4wC projects supports the argument that children younger than 12 do have the preconditions to philosophize. One ability needed is to put oneself in someone else’s position.

I believe we should consider the constructivist conceptual change/growth theory of Vosniadou and Brewer (1992), which addresses certain shortcomings of Piaget’s theory. Embedding the conceptual change/growth theory into the P4wC-Piaget-discussion could help to discuss this topic in light of more recent cognitive psychological findings. It gives us new perspectives as to why and how children can engage in philosophical discourse. My PPEE model presented here is based on the conceptual change model. Vosniadou and Brewer came to their conclusions by asking children how they perceived the world: Their data show that young children offered their intuitive conceptions, e.g., that the world was flat. Older and/or more educated children offered hybrid ideas - “synthetic models” - of the world consisting of a ball and a surface. Even older children recognized the world as what it is (1992, p. 549-575).

This model was named conceptual change/growth and was confirmed by further research. This theory became extremely successful in the field of natural science education. But even if its fundamental role for learning and children’s cognitive development has been discussed primarily in the context of (natural) science education, there is increasing interest coming from other disciplines as well, e.g., for the teaching of psychology see Maria Tulis (2020, p. 162-175).

Similar considerations to those of Vosniadou & Brewer (1992) can also be found in the humanities, e.g., in connection with Johannes Rohbeck’s “Proto-Philosophy” (2016) or with Hans-Georg Gadamer’s work: “Fusion of horizons” (“Horizontverschmelzung”, 2010).

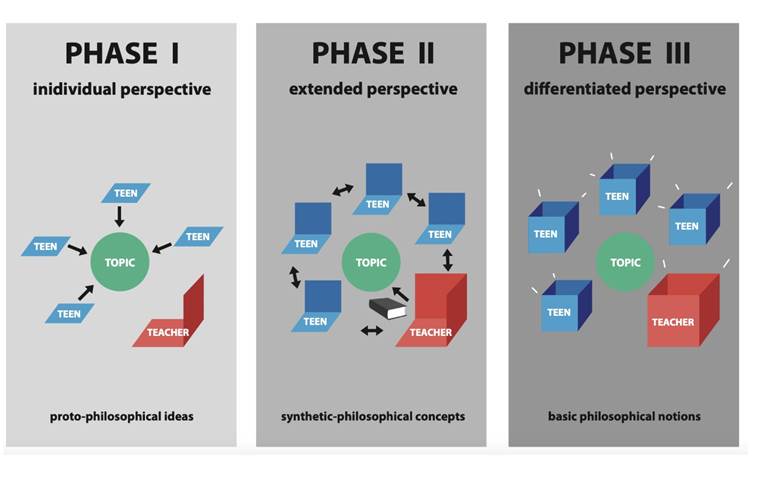

Synthesizing all those findings allows me to distinguish three distinct phases in my PPEE model: In phase I (individual perspective), children’s proto-philosophical ideas are presented. In phase II (extended perspective), these early ideas develop into synthetic-philosophical concepts due to their argumentative discussions. In phase III (differentiated perspective), those concepts finally lead to basic philosophical notions.

Contrary to natural sciences, where the aim is to reach a “state of the art” knowledge, philosophizing with children and teens aims to extend their individual perspectives in relation to a philosophical topic. This process is presented in Figure 2.

In summary: in phase one, children picture their individual points of view concerning a philosophical topic. In the next step, phase two, the teacher guides through a polylog by asking impulse questions and summarizing points of their perspectives. The children exchange their views, and then question and discuss them.

In the course of the PPEE model, there is an argumentative process where children develop extended and differentiated positions concerning a philosophical topic by using philosophical methods. This finally leads into phase three where the children present their basic philosophical notions.

Based on the work of Eva Zoller-Morf (2011), Thomas Jackson and Ashby Burnor (2017), I suggest negotiating conversation rules with children or teens before starting the philosophical discussion and evaluating the rules at the end of each discussion with the learners.

Let me clarify some terms used in the PPEE model. I would like to start with the term polylog. I use this term in the meaning of Franz Martin Wimmer (2003). He invented this term in his conception of intercultural philosophy by practicing a polylog as a concept of equal discussions between different cultures. For me, the term fits in my PPEE model for two reasons. First, children often have different cultural backgrounds and so P4wC can be seen as an intercultural exchange. Second, P4wC is generally understood as a discussion setting that gives each speaker equal rights to talk.

Let us now take a look at the term proto-philosophy which goes back to Johannes Rohbeck’s (2017) idea of giving learners a starting point to philosophy by incorporating their personal ideas and experiences about a topic before reading and discussing ideas of philosophers (2017, p. 105-106). However, proto-philosophy should not be confused with “not yet philosophy”. It only stresses the constructivist idea of learning that children’s and teenager’s preconceptions should be included to successfully connect with new knowledge. Rohbeck’s constructivist teaching ideas seem to be appropriate concerning my constructivist PPEE model.

pedagogical considerations

Let us now turn to the following question: Which scientific pedagogical considerations could extend the P4wC concept related to the ideas of the PPEE model?

Gerd Schäfer (2011, p. 83-86) and Silke Pfeiffer (2013, p. 23) demand learning settings for children that provide learning possibilities with no restrictions (“möglichkeitsoffene Lernsettings”). Therefore, Pfeiffer recommends doing P4wC already at around 5 years of age.

To reach this goal - “open learning space” -, I suggest the recent considerations of the constructivist learning theory, whose precursors are John Dewey, Piaget, and Lev Vygotsky. Those pedagogical references should broaden the pedagogical approach to doing P4wC. It must be said that constructivist ideas have always been part of Lipman´s P4C concept. Here I want to stress some of the current constructivist deliberations presented by Vosniadou (2001), to connect them with P4wC through my PPEE model. Those considerations could be a starting point for the PPEE framework to compare future international studies in the field of P4wC.

The first idea is to integrate new knowledge into an already existing structural framework. Prior knowledge is essential in both the area of constructivist learning and also in the field of philosophizing with children, as Lipman et al. (1980b), Englhart (1997), Käte Meyer-Drawe (1996), Martens (2007) and Pfeiffer (2013) point out. At the beginning, the teacher can ask the students about their individual points of view - as can be seen in my PPEE model “phase I” - and during the discussion - “phase II” - they broaden their conceptions about a philosophical topic. This leads to the second point which demands that prior knowledge should be reconstructed. Through this constructivist process, students can reflect on their intuitive ideas about a certain topic. Therefore, they must be given enough time to reconstruct their preconceptions. Both considerations go along with the third point of engaging in self-regulation and being reflective.

Furthermore, learning should involve strategic learning. During this process, the teacher can be a role model for, e.g., how to form hypotheses or how to form logical argumentations, which can happen directly by giving comparisons and examples or indirectly by asking critical questions. This is especially important for beginners, but there is a fine line between guidance and giving children/teens the time and chance to think for themselves.

Next, memorizing is not as important as understanding the content. P4wC discussions are based on talking about points of view, explaining reasons, giving examples and counter-examples, or developing analogies.

In addition, context should be transferred into real-life situations which should happen by taking time to practice. Here, for example, we could walk out of a P4wC discussion and connect with “real life” (ask others about their definition of freedom) and discuss this later at school within the constructivist process of the PPEE model.

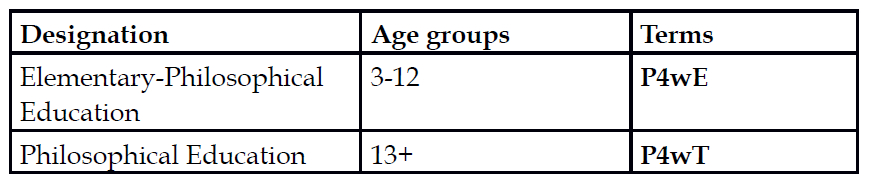

Furthermore, as I already suggested, age-appropriate considerations are needed but are often hard to find in the literature, as Englhart (1997, p. 18, p. 33, p. 188), Niewiem (2001, p. 87), Brüning (2008, p. 44) and Heinrich (2020a, p. 152) indicate. To get well-grounded age differentiations, I suggest making the terminology more precise: We have Elementary-Philosophical Education with children from around 3-12 years of age (figure 2) called Philosophy for/with Elementary (P4wE) and we have Philosophical Education with teenagers (figure 4) called Philosophy for/with Teenagers (P4wT) from around 13 years of age upwards.

Elementary-Philosophical Education and Philosophical Education bridge the divide to adult philosophy, similar to other fields like education in natural sciences, early sport or music education.

Transmitting philosophical content through philosophical novels, as Lipman and his team suggest, makes sense for both children and teenagers. My suggestion here is to incorporate quotes and texts of “great philosophers” by philosophizing with teenagers. Teenagers are more experienced with P4wC (if they had the chance to get such an education) and do in general have a broader understanding of the world, so perspectives of “great philosophers” could nurture their philosophical dialogs. That’s why you can see the book in phase two in figure 4. In addition, they get used to the language of ancient philosophers which will help them to read and understand their writings. Let us compare that to other fields teenagers become familiar with. For example, the evolutionary theory. Teenagers learn that it was developed by Charles Darwin. Teachers’ quoting some of Darwin’s important theses or text passages and are revering to some of his findings. Lipman, Sharp and Oscanyan do not stress this idea of referring to “great philosophers” too much. They only recommend incorporating ideas of philosophers if this contributes to children’s/teenager’s increased understanding of the concepts (1980b, p. 83-84).

Let me now talk about the two relevant approaches concerning my suggested age differentiation. As Lipman and others have suggested, the topics chosen must be closely related to children’s and teens' personal experiences. From my point of view, this can happen in two ways: either the topics can be proposed to the children or are given through the curriculum, or “real life” situations can be used as the basis for philosophical discussions. I would call the last idea a “situational approach” (“Situationsansatz”). Let me give you an example: It is Monday morning, and every Monday each child can bring a personal toy to their kindergarten group. The teacher observes that one child does not want to share their toy and therefore a conflict starts. As a professional, you check if the children can solve the conflict on their own. If not, the teacher intervenes in a supportive way. Later this conflict situation can be used in a discussion from a philosophical point of view concerning the topic of justice. The question that could be asked: Must we share personal belongings? The older children get the more they get involved, e.g., by choosing the topics, and even teenagers, as I already mentioned, can furthermore be confronted with texts of philosophers.

conclusion

By applying the PPEE model, which unites the findings of various fields, my approach opens up perspectives to create a broader interdisciplinary scientific foundation of the P4wC movement.

Therefore, the PPEE model must be understood as a framework to link different P4wC approaches with the goal of providing them with a broader interdisciplinary and constructivist basis that includes philosophical, psychological, and pedagogical findings. Implementing this interdisciplinary approach could facilitate the comparability of international studies which are based on diverse P4wC concepts. This comparability could be achieved on an international level by connecting the philosophical, psychological, and pedagogical perspectives through the implementation of the PPEE framework I have presented in this article. It is my hope that this will advance the field of P4wC studies by leading to the clarification of certain points of contention and paving the way for more constructive criticism in the long run.

Considerations of the third P4wC generation, as Viktor Johansson (2018) describes it, were to include gender, race, class, and cultural context by philosophizing with children and teens. My article may give initial ideas for a possible fourth wave of the P4wC movement that includes the ideas of the conceptual change/growth theory as a uniting framework and recent ideas of the constructivist philosophy of education.