An open-ended story of some hidden sides of listening or (what) are we really (doing) with childhood?

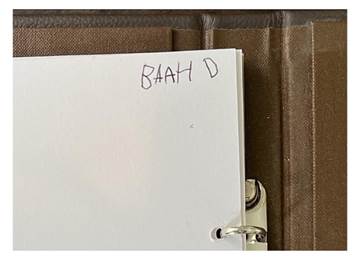

BAAH D

unknown creator

Going back to listening

Our writing-together springs from a discovery that turned into a story. A story that grew from an anecdote shared in a corridor about how Magda bumped into a small fragment of writing in her hotel room, some marks on paper that we imagined to be letters of a word made by a child. It is the story of an unexpected encounter with that written materiality, but also with our assumptions about it, and the waves of questions it provoked. The questions, all to do with listening and childhood, arose from the moment of this encounter and are still flowing as we write. It is our hope that readings of this paper continue to embrace this (self)questioning movement.

How do marks become writing? Is the very concept of writing already an adult one? Is the imperative to write recognisable words a way of colonizing the mark-making activities of children? When little children draw something, why do adults have an urgent need to name it? And how about us, researchers of childhood? Have we also fallen into that trap? Why do we, adult educators and researchers, in constant movements of translation, persist in asking “what is it?” about everything that a child draws or builds or says? Does it always have to be something? Does it have to be a word or at least something that can be translated into words? It is usual to take these translations for granted and discount them, or believe that the labels remain faithful to, or can closely represent, an “original” made by the child. But is it a matter of the drawing having a caption, a name, a meaning? Is it about us, adults, knowing what it is? Or is it about our discomfort with not knowing? Are “the imperatives of clarity and transparency” a hindrance to really listen to others (Tamboukou, 2020), especially when it comes to children? And how does this urge to translate reflect in our research practices? How does it affect our capacity to listen, both as educators and researchers? In Philosophy for/with Children research, where we both work, as with much qualitative research in Education, classroom dialogue with children is sometimes recorded, transcribed with a transcription apparatus and a computer, producing clear lines of text, to be later interpreted, organised and analysed. Are these listening practices also distorted by the adult need to label the unknown?

There seem to be many hidden cracks in the above mentioned examples: either in a classroom where a small child is questioned by her teacher about the drawings she has just made; or in the methodological choices educational researchers make to deal with the empirical data of their projects on childhood; either in a conference hotel where two researchers don’t hesitate to name as “writing” the childlike materiality they encountered, and take ownership of what they found to self-justify their attention to listening practices. We now find in all these situations many assumptions about children and childhood, as well as about what it is to listen in education and in childhood research. Epistemological and political assumptions regarding the way children’s contributions need to be validated outside themselves: by the adults that set the plot, do the research and tell the story, by the cultural structures of language that sort and exclude.

In the experience of the encounter that triggered our thinking and writing we were led to our own starting point: the hidden sides of listening to children. In our writing about the experience, one question first emerged: is the first of these hidden sides the fact that we did not even stop to consider that we knew nothing about the found object? And that just by naming it “a tentative word” or “a set of letters” we were already on the same practice of not listening? Of not recognizing how much we did not know? And in what way this that we do not know may be epistemologically and politically contagious? Are we also trapped in a form of knowledge that, just like Gemma Fiumara claims, “has lost its potential for listening” (Fiumara, 1990, p. 33)? Are we fascinated over what children have to say, or by our own skills as listeners? The rush of discovering, naming, owning, showing, sharing... are these obstacles to listening, or rather inevitable movements that come with the research?

Driven by these questions, our writing folds and unfolds different layers about listening to children and we return over and over to the authors. Like Maria Tamboukou, who interviewed refugee women sometimes speaking in languages that she, the researcher, did not understand, Viktor Johansson also wrote about listening in a context where the hearer is not always fully aware of the speaker's linguistic codes and contexts. In his experiences in research that he conducted with the Sami Children, in the North part of Finland (an indigenous community), Johansson often didn’t understand the language the children were speaking, the meaning and translation of the words that they used to communicate with him. And, for this reason, in his writing we find a strong sense of what it might be like to listen when we are researching with children. Viktor Johansson refers to listening as “walking alongside” children’s thoughts and he suggests:

It requires more than pedagogical listening as a didactic approach, common in early childhood education practices. Walking with the children’s thoughts is also a matter of listening philosophically, letting their thinking challenge us existentially. (Johansson, 2021, p. 13-14)

But how might the listening itself be more than a didactic approach, in the sense of being philosophically relevant? What does philosophy, as a certain relation to knowledge (Kohan, 2015), have to say about the importance of listening? Or how can listening be a philosophical experience on its own (and not just a derivative concession of speaking)? Gemma Fiumara also challenges us to listen rigorously, not as an abrupt cut or an upheaval of thinking, but in terms of a rationality that frees itself from the bellicose paradigm of what she calls a frontal attack. The Italian thinker’s words seem to talk directly to our experience with the materiality of the found paper in the hotel room and to the possibility of some previous exclusionist frames in our relation to it:

The thing experienced itself becomes capable of utterance insofar as the interlocutor adheres to a rationality which is capable not only of saying, but above all of listening, and insofar as the interlocutor opens himself to the strength of thought springing to life in the other, free from the cognitive claims provided by his own interpretative parameters. (Fiumara, 1990, p. 144)

When is someone really capable of listening to an experience? Is it when that person has the experience of listening? Or is the experience of listening nothing but the listening as an experience, in the sense of what happens to us and transforms us (Larrosa, 2014)? What happened to us, to our listening, in the encounter that we had with the “thing experienced”, being the mark-making activities of a child? Was our relation to that inscription already colonized by cultural and philosophical frames that we silently carried with us? Were we free from what Bronwyn Davies calls listening-as-usual (Davies, 2014) or not? Are we now free from it or can this piece of writing still be held a captive of biased listening? Could it have been a tokenist practice (Lundy, 2018)? And how about you, dear reader, where does your listening stand?

Today much research has been carried out about listening, and specifically about listening to children (Cook-Sather, 2006; Davies, 2014; Lundy, 2007; Taylor & Robinson, 2009; Spyrou, 2016). All that was said and claimed supports our sense that it is one of the most relevant topics to bear in mind when we are in any educational encounter: either as educators, or as researchers. But our claim is that - for educators and researchers - it may not be enough to review the literature, since the most important and interesting way to relate to what we do is to be attentive to how some of our practices demand that we keep returning to ourselves in order to explore our own assumptions. As David Kennedy puts it, this exploring of assumptions implies that educators - and also researchers of childhood, we might now add - practice themselves a philosophy of childhood in the sense of a permanent exercise of recognising, deconstructing and reconstructing beliefs about children and childhood (Kennedy, 2015).

If schools are, in our society, a privileged place for dialogue between children and adults, we then stand for the position that philosophy’s place in schools has to do with a practice of listening that first and foremost invites educators and researchers to re-question themselves: when we say we are listening, (what) are we really (doing) with childhood?

Taking philosophy to schools or (just) listening to what is already there?

The encounter that brought listening into question for us, and that made us re-question our own experiences of listening to children, happened through the story that we are writing in this paper. It arose between the scribbling and the scrabbling, interrupting our everyday-life as two researchers preparing for a conference presentation in another country. This was a conference that concerned philosophy in schools, focusing on why we (adults, educators) should take philosophy to children. We had been challenged by the organizers to think about philosophy’s future as an educational project.

We both had been involved with the Philosophy for/with Children movement (Vansieleghem; Kennedy, 2011) for many years, working with philosophy in schools, and other educational environments. From our previous work and conversations together4, we had little doubt as to the need to keep bringing children and philosophy together. However, our idea for the conference presentation was not preparing a lecture focused on the apology for philosophy’s benefits for children (Gregory, 2002; Scholl, Nichols & Burgh, 2009) or even to anchor our reflections on the goals of this practice (Anderson, 2020). As much as we consider those to be important topics, we decided we should look for a different approach: not the laudatory speech of someone that is absolutely sure of her beliefs and claims, but - as we have said - a position of self-questioning as a re/turning to our own practices. Yes, of course we want philosophy to be in the schools. But while we are busy putting a case for this claim - we thought - what grey areas and blind spots are we leaving unattended? And what do these blind spots say about the way philosophy may (not) be listening to children (even when it claims to be doing so)?

The aforementioned Philosophy for/with Children movement was born out of a certain need, and an aspiration, to change the way children are considered in today's society's educational settings (Sharp, 1987; Lipman, 2003). Thus, people who have been part of the movement - even if in diverse ways - have seen philosophy as a way to open up to different ways of relating to thinking, to childhood or to school (Gregory; Haynes & Murris, 2017). And, as we know, those are, indeed, very complex settings and relations. School as a social and political institution has been both praised (for example, Masschelein; Simons, 2013) and strongly criticised (for example, famously by Illich, 1972) over the last decades, and it has maintained an important role in (almost) all children’s lives. This conference that we were preparing for assumed the social and political importance of school, proposing to the invited speakers to consider philosophy's contribution to it.

We had an interest in common: to (re)think one dimension of what we were doing in school that seemed all at once crucial, talked about a lot and yet almost forgotten, this is, the issue of listening to the children. As we stated previously, listening is far from being a new subject in educational and childhood studies and has been considered from many different approaches (Lundy, 2007; Taylor, Robinson, 2009; Davies, 2014). Philosophy for/with Children is not an exception and inside the movement listening has received some attention (Haynes, 2007, 2008; 2009; Haynes & Murris, 2009; Johansson, 2013; Johansson, 2022; Costa Carvalho, 2022). Listening is maybe the beginning of any educational encounter but, whereas many people tend to worry with technical dispositions and skills (Gardner, 1996), there is one author that has written extensively on the subject from the standpoint of the person who facilitates philosophy activities in schools. The already quoted David Kennedy calls that person “the facilitator” (Kennedy, 2004) and states that listening is both a capacity and motivation needed in the context of this person’s role:

[…] there is one particular basic disposition that is indispensable [to be a successful facilitator of communities of philosophical enquiry], and that is the capacity for and the motivation to actively listen, whether to children or adults. In the case of children, the capacity to listen is influenced by the fact that many adults carry around with them a set of beliefs and assumptions about children and childhood that they project onto real children, which can dramatically affect how seriously or accurately they listen to them, if at all. (Kennedy, 2015, p. 28)

Just as both Johannson and Fiumara claimed, and as we indicated above, once again we find the idea that listening seems to have hidden sides, since its practice triggers beliefs and assumptions regarding the very nature of what we are doing when we sit - or walk or stand - to think philosophically with children. We stay with David Kennedy’s idea and add that, in the school setting, listening is also framed in particular ways, as educators - through the curriculum and other social goals of schooling - are often drawn into listening for particular (right) answers or (suitable) behaviours, rather than listening to children from a position of genuine curiosity and belief in reciprocal intergenerational social and political learning. And in research the same seems to happen, since what children say is often instrumentalized for the sake of specific arguments or the proof of some claims. In this sense, it is not a concern that belongs only to the facilitator of a community of philosophical enquiry or even only to teachers and researchers in general. But one that has to do with whomever encounters a child. We could even go further and state, with Haynes and Kohan, that even the terms chosen to speak about who is involved in philosophy in the school setting - one person that is a facilitator and many other that are facilitated - could be an undercover model of distance and hierarchy between adult and children (Haynes & Kohan, 2018), hence not an attitude of listening.

Tracing back our story with all these enquiries and concerns, we recall that we were invited to participate in a conference about philosophy in schools and that we decided to explore the hidden sides of philosophical listening practices. When we arrived in the city of the conference, we had already chosen the theme of our presentation: the hidden sides of listening to children, with a particular emphasis in the community of enquiry setting. We had been exploring the problem that when we speak of listening-to-children, so much is already taken for granted. But what does it mean to truly listen to? Even between children, who are the ones that are indeed listened to? Who is left on the margins of school’s sonorities and receives no attention from the ears that belong to the people that usually make the decisions? Who is silenced or left outside the community of enquiry sounds and tunes? Which sonorities are the ones that are truly listen to? And when we sit at a university conference to think about if and how we should bring philosophy to schools, is it possible that we are already disregarding listening to children?

This last enquiry was puzzling us since we were troubled by the very question of why we (educators and researchers of childhood) should bring philosophy to school. Isn’t this implying that philosophy isn’t already happening there: in the different spaces where children meet, are moved, play and interact with each other and with the more-than-human, every day of the week? In the toilets, corners of the playground, corridors, by the gates? Places where adults are not always or so intensely present and directing things. Or places where adults only listen to children with a heavy set of beliefs and assumptions.

When we were preparing our talk before the trip began, we thought it would be valuable to call up our own childhood memories, and find out about the childhoods of others too, to remember what school was like, how it smelled, tasted, sounded and felt. The physical journeys to and from school. The places of childhood when adults were not present. Laughter, fear, curiosity, confusion, astonishment, tears. Our smaller bodies, things in our bags, bugs kept in jars, heavy backpacks, our shoes, complicated shoelaces, clothes that we did not like, friends that we did like, the pencils, abuses, tasty and disgusting food, hunger, lost pencil sharpeners, and chairs. What memories come to us at this point? What sounds do those memories provoke in us - while we write - and in you - while you read? And what can this exercise say about our modes of listening, now that we become adults? Why do we presume that, unless there is an adult present, in none of those mentioned situations we could have philosophically relevant events or enquiries happening? Why do we assume that there is only something philosophically worth listening to in settings where adults are in charge? What kind of philosophy is that? And to what point does that philosophy truly listen to children?

As researchers preparing for our conference, we were struck by what looked like a very troubled position: alongside the claim that children are naturally philosophical (Matthews, 1980), we keep reproducing the idea that schools are a kind of philosophy-free zone without the interventions of educators. How can that setting promote listening? Aren’t we saying that if adults in the schools do not import philosophy, in the form of lessons or even communities of enquiry, the children will be deprived of it? That they will not grow as philosophers? That they will not become what they could and should become, in order to be better persons and citizens?

This troubled idea hit us hard particularly given what the movement of Philosophy for/with Children professes about children’s tendencies to pose questions and to philosophise (Matthews, 1980), about how they are already inclined to explore (Haynes, 2014), and about philosophy as a childlike practice (Kohan, 2011). We felt that we did have a difficulty if, on the one hand, we believe young children have something to say and think of them as already able (Haynes, 2014), children whose thinking takes us somewhere new and unexpected and, on the other hand, see ourselves adults as the principal instigators, shapers and monitors of philosophical enquiry. Hence, in our talk, we decided to explore the theme of what remains hidden, asking ourselves where and how philosophy and philosophising might already be everywhere where there are children, especially in schools, but we educators (even in Philosophy for/with Children) somehow do not notice it since we are not listening. Or, at least we are not listening to everything.

And, we were daring to ask, if we followed this idea, where would we stand regarding the community of philosophical enquiry itself, about our place in it (as promoters and/or researchers of it)? We asked ourselves if - in conferences like the one we were preparing to - we do not speak enough of what lies behind how adults and philosophers learn to listen and to what they pay attention to in public spaces such as schools and universities.

listening to the ways we listen

Thinking again about what it means to philosophise with and listen to children in schools and what we might have been missing, maybe it is time to tell more of the story, giving you, dear reader, more details of what happened. The decision to write this paper started with the events that we are about to tell you, in the context of a conference on the future of philosophy in schools. But the story itself - or its philosophical implications - did not happen before (or outside) the writing, since it has been unfolded by the narrative and by the experiences this narrative also triggered.

We had made a plan for what our presentation could look like, Joanna in England and Magda in the Azores. It turned out that, when we met in person to prepare further for the Conference, the smooth plan we had of what to present was disturbed by a thing that found us. A small thing between the scribbling and the scrabbling. More than that, this encounter happened outside of what was expected. Thus, thinking about the hidden sides of listening became something of a quest with ourselves: our ideas on children, on childhood, on thinking, writing and, most of all, on listening to children. What was hidden in all of that? What was searched for? Where were we looking? What found us? At that point of the events, we still did not know. And at this point of the story, of the writing and reading, we wonder how much we are still ignorant of.

But let us return to what happened. We were trying to figure out what was important in listening to children, and how we would come to know it. “Important” is a concept that we should cautiously bear in mind when we tell this story since the finding of the object occurred precisely when one of us - very sure of herself as a serious researcher engaged with her work - realized that the first thing one should do when getting to the hotel room on a working trip is to focus on the importance of being connected to the internet, to sending and receiving messages, to listen to the world. This being so, the first thing she did was to rummage through the hotel room to look for the most crucial thing: the wifi password.

What she found was a smartly covered folder with the hotel logo on the front: the folder with all the information regarding the hotel services (laundry, wake up, breakfast…). A folder that, however, did not contain the most important thing so far for a researcher and conference speaker: the wifi password for the hotel. So, almost assured of the uselessness of the gesture, she leafed through the sheets of the folder until the very last page. It was supposed to be a blank page. But it wasn’t. Another unexpected event. The last page bore an inscription: BAAH D. Five small letters written in the upper corner of the sheet, just like little things, small and forgotten. And little things matter so much, just like we learn with Tanu Biswas (2020). Maybe it was five small and hidden little things. Perhaps waiting to be found, to be noticed. Perhaps just laying there, for no reason. Perhaps attracting useless gestures.

Not long after our arrival at the hotel, when we looked at it together, with a kind of astonishment, the inscription seemed to us to have been written by the shaky hand of a child, perhaps one that was starting to learn how to draw the letters or hold different kinds of writing/drawing tools… perhaps waiting or playing and finding something to do on a blank page of paper that was there in the hotel room, while the adults were distracted doing important things6… like looking for the wifi password.

The discovery of this writing - better said, what we supposed to be a discovery of what we assumed to be a writing piece - coincided with our sense of discovery of the foreign city we had just arrived in, with ‘coming across’ the things we were looking for but also what we were not expecting. The park square across the road from the hotel: a historical site of political resistance, struggle and death, now a haven for wildlife. A museum of literature next door, with a beautiful garden behind, meeting with cherished fellow delegates we had not seen in a long time, to catch up and share food. Conversations with international students, from Brazil and other places, working as waiting staff and serving us breakfast so carefully in the hotel dining room. Finding out their hidden expectations of studying literature and arts. The location of the bus stop and the humour of the bus driver. And, in that sequence, the discovery of the scribbling on the last page of the hotel information folder.

The question that we did not make at the time was if all of these findings were of the same sort. When Magda showed Joanna the last page of the folder found in the hotel room, we suggested to each other that we should start our presentation with that same folder. We celebrated the way through which listening to children had become an existential part of our own story in the Conference, for it seemed to us that listening had to do precisely with what had happened to us: being available to notice the inscriptions, the small resistances, a childlike way of being in the world insidiously and silently affirmative. Most of all, we celebrated our own capacities of listening, slightly inebriated with our accomplishment in finding the object.

When we started to imagine meanings and to assign possibilities to the folder, when we built the story that we would present orally the next day at the University, we did not even consider the possibility that we could be doing exactly the opposite of what we were talking about. That we could precisely be dealing with a hidden side of listening, that we could be performing it. When we were celebrating the finding of the supposed writing of a child, we were asking a lot of questions: was it an inscription or mere random marks? Would it have been made by a child trying to defy the implicit norms of where one can and where one cannot write? Was s/he resisting those norms? Was s/he trying to write 'bad'? Were we the ones that read "bad" because we have this need to give words and meanings (our meanings) to what children say and do?... Or was s/he just trying out a new pen? Was it the attraction of a blank piece of paper? Could it be an artwork? An act of resistance or mere boredom?

But the questions that remained hidden when we were celebrating this finding (one that at this point indeed seemed to fit so “perfectly” with the theme of our talk) were also hidden. Probably questions that could not have emerged at that point, questions that needed to wait for the writing, latent questions; the kind of questions that put the questioners into question: what was exactly this finding for us, two researchers at a conference? Was it a kind of trophy? Did we seize on it, were we stealing or colonizing it? Were we not listening after all? Should we have looked deeper into the unexpected? Or was it a question of listening more attentively? What gives meaning to the listening: the way we perform it or what is done with what is listened to?

While Viktor Johansson (2021) draws our attention to other places we might be philosophising with children , we want to bring his questions back into the place of school, to the issue that children’s philosophy is already there and to what we did with the found object at the Conference. Building on this movement, we then invite the readers to ask what philosophy might this be, why it remains hidden and whether it is our place as adults to try to listen to it. Listening in the sense of being aware of it, but also listening as a practice of disclosure and revelation. And also, to question: if we do not reveal the contributions of children, what might be lost? But if we reveal it, when might this become intrusive, instrumentalizer, even a kind of surveillance or exploitation of all children’s thoughts?

Our journey in the foreign lands of listening to children took us to the Gordian knot of the issue. Tracing the hidden sides of listening has to do with a quest to what must be revealed in the content and the exercise of listening? Should the BAAH D in that sheet be made public as the opening performance of the keynote talk of a university conference? Or is there sometimes also a risk that in our fervour to honour children’s philosophical thinking, and to draw the attention of others to children’s capacities to philosophise, we fall back into a trap of extracting their ideas, using them out of context, to further our projects, to present talks at conferences and write papers that draw on our voyeurism and eavesdropping? How can we strike any kind of balance between promoting children’s voices in philosophy and colonizing or intruding in their lives and worlds?

Perhaps this is a new project, a project connected to the slippery concept of “childism” (even as a contestable concept, Rollo, 2018a, p. 16, n. 2), that is now emerging in the field of childhood studies and beyond and which requires us all to go back to the beginning of childhood, education and philosophy. The beginning of our story, the beginning of our writing but, especially, the beginning of our listening practices. Not only Joanna and Magda, but the listening practices of our dear readers, of anyone who sits, eats, or walks with children. The listening practices of whoever has the privilege of listening to childhood.

Writing about this recent shift towards what he calls “childism” (in the sense of the empowerment of children, as a group that has been oppressed due to a chronological movement of exclusion), John Wall writes:

Social understandings and practices have historically been dominated by adults and adult points of view, leaving the entire edifice of human societies, cultures, language, rights, law, relationships, narratives, and norms built upon a powerful bedrock of adultism. It is this broader and more systemic problem to which childism makes a response. (Wall, 2019, p. 4)

Wall connects the nature of existing structures and systems that historically occupy an exclusively adult world view and everyday perspective (also called adultism) with the oppression, exploitation and exclusion of children. Wall uses the term ‘childism’ similarly to feminism, to convey the transformative sense of recognition of children’s historical exclusion and the need to re-create social systems in the light of children’s ways of doing and being. Drawing closely on Wall’s work, Biswas (2020, p. 1) describes childism as “the effort to reimagine and practice child-inclusive social processes and structures […] it aims at treating children as scholarly and democratic subjects, as far as this is possible”.

But the concept of childism had been previously used in the sense of misopedy or a prejudice that puts the needs and considerations of adults over those of children (just because they are not adults) (Young-Bruehl, 2012). In his analysis of the centrality of the concept of child to conceptions of race and the association of “degraded childhood and Blackness”, Toby Rollo argues that challenging anti-Black racism requires an interrogation of anti-child ageism. He refers to this paradigm of childhood “as a site of naturalized discipline, violence and criminality as misopedy,” denoting both the objectification and fetishization of child (Rollo, 2018b, p. 310).

It is important to note these two very different ways in which the concept of childism has been deployed in childhood studies literature, on the one hand to signify a kind of hatred of child, also tied into patriarchal and colonial systems of oppression and violation, held by western belief systems; and, on the other hand, to signal the possibility of social and political transformation through child inclusion and emancipation.

Inside the Philosophy for/with Children movement these discourses are being taken up and the concept of childism is beginning to be explored. It has been used, for some time, in more than one way by authors in the field, for example, Murris (2016, p. 43 ftn 22) has described childism as “a particular form of ageism”, and ageism being a “form of epistemological, aesthetic, ethical, social and political exclusion” (Kohan, 1999, p. 66), a prejudice and discrimination toward a person on the basis of her age (in this case, her young age). This meaning of the concept may be traced back to the exposure of “epistemological egocentrism” as “a view from one privileged epistemic location” (Kennedy, 1995, p. 42). But it has been consensually referred to as “adultism” (Kennedy, 2006, p. 70), an attitude based on the deficit model of children. Not listening to children would be the most obvious manifestation of an adultist stand but, just like J. Wall warns us, adultism is a powerful bedrock and, like any form of power, it not only represses, but it also produces (Foucault, 1975).

Telling the story of the found folder took us back to the beginning: our production as educators, as listeners of children, our own gestures as researchers of childhood. Is it possible that in the least suspected place - a conference about the need to listen to children, promoted and carried out by people involved with the emancipatory role of philosophy in treasuring childhood - practices of disregard for children could still emerge? Could those be adultist listening practices? In addition to the assumption we have talked about on the part of adults that philosophy is not already there and that adults are the only ones able to bring it in (in the space, time and shape of classrooms), does the identification of adultism requires us to return to the question of what counts as philosophy in schools? Or simply what counts as philosophy? Are these the questions that we need to ask ourselves in the movement of returning to the beginning?

Perhaps this movement begins with asking what we think school is. Maybe a classroom full of chairs, tables, children sitting on those chairs, facing the teacher, who is standing and probably passing them some knowledge… or even working as a community of enquiry, sitting in a circle, with a teacher facilitating the dialogue and children following the rules of enquiry. But this is only one idea of and part of what schools are and if we asked the same question to some children who are in school right now, we might have different images. Maybe from places other than classrooms, places where serious play, play things and friends are what matter the most, places where important and decisive conversations take place, places that have meanings beyond intentional learning outcomes. Are those places (like school playgrounds, toilets, sheds, corridors, the entrances, neglected corners) places where the adults are not always present, and when they are they have a disciplinary role? And does discipline turn any space into a space of invisibility and inaudibility? How do we build ourselves as educators and researchers in school places that are not mainly populated by adults? What do we make of school when we disregard those spaces, when we classify them as not important? And what are our claims about what philosophy is when we assume that it cannot emerge in those places? How do we build ourselves as listeners of children when the listening exercise is, first of all, one of exclusions?

Or how to avoid being seen or heard in the classroom?

noticing: childhood as a political locus

Perhaps, we wondered, schools are somehow spaces without ears or only ears listening for specific sounds, sounds of words or gestures, specific words and specific gestures, words and gestures that imply what is considered a wrong-doing or not desirable thing. This made us think about what are mostly considered the desirable kinds of noises to make in school. From school as a listening place to school as a sonic place. What does it mean to say that there are desirable and undesirable sounds (in schools)? What counts as a desirable sound? What turns a sound into an uninvited sound? What can we tell about a school only by its soundscape (Schafer, 1994)?

A different logic for the school sounds may be possible: not a logic of tuning, but a logic of dissonance (Johansson, 2013). Not a trained exercise of domesticating children’s voices, emptying it from its immanent strength, but “a school capable of listening to the world in its noises, moans, whispers, babbles, cries, stammering, screams, grunts, in short, with possibilities of sound and with the most varied tones” (Roseiro et al, 2019, p. 16).

Elsewhere we have made reference to the sonority of children’s voices and the uniqueness of each voicesound (Costa Carvalho, 2022), following Adriana Cavarero’s work (2005). Adults generally prefer that any noise children make be in the form of words, and these spoken carefully; there is so much hushing that goes on in school. Is it only when the right words are written or enunciated clearly, in turn, that they can properly exist and be philosophised about, or acted upon?

Adults listen in order to re-present children’s perspectives to show that they are interested in and know how children think. It is true that adults can also be interested in children’s constructions, playing, figurations and drawings. Early childhood education philosophy inclines us to follow and respond to children’s ideas and activities (Doddington & Hilton, 2007) and, to do this, usually we want children to tell us more, to tell us what it is about? What it re-presents. Just like what happened with us before our Conference talk.

In our finding of the fragment of writing in the hotel room, we thought we had a clue to unlock something about the author, her/his thoughts, her/his understanding and feelings, her/his sense of what the hotel folder was for and of what hotels are for. And that this in turn would illuminate a childlike world and perspective to help us figure out what to say to educators and researchers at the conference about the hidden sides of listening and how to philosophise with children in school. But maybe what we did was to turn a place and time where adults are not invited in (the last page of the folder, where it was not supposed to have information, a margin of what is important in the world) into a place where adults are again in control of the meanings.

These days too, when it comes to listening at school, there is greater vigilance if the telling includes a disclosure of wrong-doing towards the child, and the term safe-guarding is adopted. Adults listen in order to guard. And when an adult says to a child "listen!", it usually means “stop what you are doing!” or "obey!". When it comes to noises not in words, educators tend to be disturbed by the silence of mutism, shouting or crying out, children’s quiet or loud expressions of anger and frustration, or playful so-called silly noises. So when we talk of listening to children’s voices, we have already jumped ahead to assume many such qualifications of what voice can be in a classroom. And yet silence or raw and sometimes dissonant noise are often the only forms of expression left when school becomes unbearable, as it sometimes does. When persistent, such unwanted noise from children in school is called a meltdown or a dis/order, and met with a long process of psychological diagnosis, a diagnosis of behavioural disturbance or non-conformity to what is called neuro-typicality7.

Does philosophy have a place among these noises? How do we listen to such unsteadying voices in a philosophical way? As Johansson puts it when he audaciously writes philosophically about tantrums, “The tantrum becomes a way to keep the question alive; a way to show that there are other possibilities that the decisive certainty of adult knowledge does not recognize” (2022, p. 7). In his exploration of children’s philosophy and adults’ role in it, beyond school, beyond what is planned, in unexpected places and forms, Viktor Johansson turns to sources of literature that speak of particular childhood experiences, experiences on the margins of what is usually considered philosophical. He draws our attention to examples of children’s philosophical thought manifested in tantrums and silences, and he explains that:

This focus has grown out of an interest in philosophizing that comes alive in practice, that is intensified in children’s encounters with the world, with others, with language, in play. Namely, this is a philosophizing that happens outside and in addition to planned philosophical discussions and the kinds of classes that are common in the philosophy for and with children movements. (Johansson, 2022)

We find the idea of philosophy coming alive in practice and intensified through encounters in the world is so pertinent, so urgent and so serious. Adults are often doubtful when children express political views. They are ambivalent about children being involved in political action for example. Curiously, this does not happen when children are seen as subjects with an ethical or even a religious agency. It is a common belief that, from a very young age, children are capable of distinguishing right from wrong, good from bad. And it is common for children to be introduced to religious practices from an early age. But when it comes to recognizing children’s agency and rights to political participation, the scenario is totally different. They might be brainwashed, or manipulated, it is thought. They might miss out on education. They are too young to understand.

And yet, at the time of our writing we have been inspired and moved by creative photographs made by brave schoolgirls inside their school classrooms in Iran, that are also non-conformist, in themselves expressions of their embodied and materialised political philosophy, showing their straight backs, in this moment choosing to show their very long hair, newly shaken out from its covering, and their defiant hand gestures towards portraits of rulers whose policies and actions make the bodies of women and girls into sites for state intervention and repression. Much remains hidden, the individual identities of the girls, what they have secretly taught themselves about the world, as they have waited, quietly, for the moment to make noises and gestures and raise questions about their freedom. The photographs show them standing very closely together, their sides touching, sometimes with their arms linked, human chains of protesting bodies, now refusing the control of head coverings. Bodies gracefully woven together. Many Iranian children have already been arrested, taken to so-called mental health facilities or even killed for their thinking and action. There is so much to learn from these childhoods, cloaked in secrecy, screaming to be listened to. Are these not also places of childhood? Are these not also spaces for philosophical listening? Loci of political standings? On what grounds is this listening being made? Who is giving these sound meanings? Is listening also a matter of noticing (Mason, 2002)?

Johansson’s work echoes our interests in re/membering childhoods, not only our own, but those many different accounts to be found in literature, historical documents, photographs and art, and what these can add to our understanding of listening to children’s philosophy, the questions raised when we put them alongside contemporary practice that has become normalised, naturalised and taken for granted as how it should be; ways of thinking that completely fill us up and leave no room for other questions. It connects with our preoccupation, in this paper, with what is hidden and might, or should be discounted, when we are so busy with the immediacy of how to import philosophy to the classroom or with the technicalities of facilitating dialogue. For us, it is towards the transformative idea and associated practices that we wish to turn, stepping away from adultism (or childism, if understood in the negative sense of repression and exclusion); unearthing and dismantling its systems and turning towards childism as a path to find new ways to become available through radical forms of listening, noticing and (self)questioning. While we are busy thinking about how to do philosophy in the classroom, what to say in a keynote conference talk and why children need us to bring philosophy there, are we likely to miss what is right under our noses (Haynes & Murris, 2020)?

We want to end by suggesting that this question of listening to children is far from being answered, that it is not even supposed to be answered in the sense of giving it closure. It is a question that needs coming back, re-turning, re-questioning, self-questioning, so that it can open new directions of thinking. It sometimes seems like a very tired and overworked topic, but we contend that we are just at its very beginning, and that it is a topic for an endless beginning. Because it is not “just a topic” but the driving-force of what we do as educators and researchers of childhood, having much less to do with what children do or how they live, than with the adult structures and dispositions; and because listening has to be practiced as a beginning: meaning that it should always takes us back to the start, to ourselves, and that we should be in the listening just like we are in the beginning of something… looking for the important things, but being attracted by the useless, the marginal, the not listened-to-yet, the inaudible, the baah d.