Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Práxis Educacional

versão On-line ISSN 2178-2679

Práx. Educ. vol.18 no.49 Vitória da Conquista 2022 Epub 04-Jul-2023

https://doi.org/10.22481/praxisedu.v18i49.11095

ARTICLE

CRITICAL READING OF INTERNET MEMES IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE CLASSES

1Universidade Federal de Sergipe - São Cristóvão, Sergipe, Brasil; jeffcarmo@academico.ufs.br

2Universidade Federal de Sergipe- São Cristóvão, Sergipe, Brasil; pauloboasorte@academico.ufs.br

3Universidade Federal de Sergipe - São Cristóvão, Sergipe, Brasil; manusnb@academico.ufs.br

Memes can be defined as small units of meaning transmitted and transformed from person to person in processes of copy and imitation (DÍAZ, 2013; DAWKINS, 1976). As time went by, the theories about memes were reviewed due to contemporary issues regarding technologies in society (SHIFMAN, 2014). In face of these aspects, we present and analyze documentary research (LAVILLE; DIONNE, 1999; FLICK, 2009) characterized as a data collection of memes and a didactic sequence in the context of English language classes. Our analyses were based on the perspective of critical reading and social justice (JORDÃO, 2017). As a result, we point out memes as potential resources for the establishment of critique in classroom since they can portray diverse realities.

Keywords: critical reading; language; internet memes

Memes podem ser definidos como pequenas unidades de sentido transmitidas e transformadas de pessoa para pessoa em processos de cópia e imitação (DÍAZ, 2013; DAWKINS, 1976). Com o passar do tempo, as teorias sobre memes foram revisitadas devido a questões contemporâneas envolvendo tecnologias na sociedade (SHIFMAN, 2014). Com base nesses aspectos, apresentamos e analisamos uma pesquisa documental (LAVILLE; DIONNE, 1999; FLICK, 2009) caracterizada pelo levantamento de memes da internet e uma proposta de sequência didática no contexto de aulas de língua inglesa. As análises foram fundamentadas na perspectiva da leitura crítica e da justiça social (JORDÃO, 2017). Como resultado, apontamos os memes como recursos potencializadores para o estabelecimento da crítica social em sala de aula, uma vez que eles podem retratar realidades diversas.

Palavras-chave: leitura crítica; linguagem; memes da internet

Los memes pueden ser definidos como pequeñas unidades de significado transmitidas y transformadas de persona a persona en procesos de copia e imitación (DÍAZ, 2013; DAWKINS, 1976). Con el tiempo, las teorías sobre los memes se han revisado debido a problemas contemporáneos relacionados con las tecnologías en la sociedad (SHIFMAN, 2014). A partir de estos aspectos, presentamos y analizamos una investigación documental (LAVILLE; DIONNE, 1999; FLICK, 2009) caracterizada por la encuesta de memes en Internet y una propuesta de secuencia didáctica en el contexto de las clases de lengua inglesa. Los análisis se basaron en la perspectiva de la lectura crítica y la justicia social (JORDÃO, 2017). En consecuencia, señalamos a los memes como recursos potencializadores para el establecimiento de la crítica social en el aula, ya que pueden retratar diferentes realidades.

Palabras clave: lectura crítica; lenguaje; memes de internet

Opening remarks

The Internet has been integrated into human life in the Twenty-First Century. In Brazil, according to the 2019 ICT Households survey (CETIC-BR, 2020a), about 74% of the Brazilian population access the Internet. Most of the users are young people, who share messages with their friends and relatives, interact via video calls and access social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tik Tok and streaming services as YouTube, Netflix and Spotify. Not only do those users consume, but they also produce content in the convergence culture context (JENKINS, 2009), in which traditional and alternative media are influenced by voices of both professional and common people, who seek for attention, engagement and participatory spaces.

According to the 2019 ICT Education survey (CETIC-BR, 2020b), students constantly interact through their smartphones in schools, regardless of being inside or outside the classroom. Moreover, the survey revealed that 98% of students from urban areas access the Internet through those devices, and 58% use them to do school activities, even in situations with no Internet connection. In general, they take pictures of whiteboards and textbooks, take notes through text processors and audio recorders, search for words in offline dictionaries, play videogames and they share those contents with their classmates. Nowadays, some of the most widespread contents interchanged by young people are memes, the object of this article.

Memes can be defined as small units of meaning transmitted and transformed from person to person in processes of copy and imitation (DÍAZ, 2013; DAWKINS, 1976). This article aims to present and analyze documentary research on Internet memes along with a proposal of a didactic sequence in the context of English language classes. We understand didactic sequence as a language teaching and learning procedure whose focus is on written as well as oral texts in a genre-based concept - which is in line with Dolz and Schneuwly’s perspective (DENARDI, 2017).

Taking those aspects into account, this study is grounded on a critical and qualitative perspective (JORDÃO; FIGUEIREDO; MARTINEZ, 2020). We have divided this article into seven sections: in the first section, we present our proposal; in the second section, we present an overview on the current research about memes; in the third section, we illustrate the way we have organized this research; in the fourth section, we provide an overview on theories concerning memes, critical reading and social justice; the fifth section focuses on the analysis of four categories of memes [race, gender, social class and political orientation] and; the sixth section presents possibilities of pedagogical activities through the analysis of a didactic sequence. Finally, we bring a summary by providing some remarks.

Current research on memes

In order to provide an overview on the current academic scenario of Internet memes with regards to language teaching, we have selected some papers which proposed classroom practices through different types of memes. The articles presented in the following paragraphs addressed the notion of memes as means of fostering creative and critical practices in Education. Moreover, some of the authors emphasized the entertaining and fun possibilities of memes. We are aware, though, that this brief summary does not cover all the diverse perspectives towards the inclusion of memes in educational contexts.

To begin with, Matias (2020) suggests that Internet memes are meaningful resources for developing critical thinking skills in classroom-based scenarios. He conceptualizes critical thinking as a way of analyzing content and explaining concepts as well as a means of searching for different perspectives of reading and thinking about social issues. Reddy, Singh, Kapoor and Churi (2020) defend that the integration of Internet memes in Education is a way of covering up students’ preferences and identities with regards to out-of-school practices. Thus, by including such texts in classroom routine, teachers could be linked to what students commonly interact with in daily life.

Dongqiang, Serio, Malakhov and Matys (2020) discuss the potential of Internet memes in different contexts of language Education like English, Italian, Russian and Chinese classes. They present memes as useful resources for dealing with ideology and for developing creative practices with students. They also emphasize the use of resignified memes on the subject of remote classes demanded by the covid-19 pandemic. Kayali and Altuntas (2021), on the other hand, propose the use of memes for the teaching of vocabulary in English language classes. They assert that memes provide students with joy and innovation concerning the idea of including memes for reviewing vocabulary. They mention that students normally tend to be creative in terms of language when they get in contact with memes in the classroom.

Hartman, Berg, Fulton and Schuler (2021) discuss the use of memes in the study of Literature through artistic response. They define artistic response as the practice of creating/developing connection with literary works via varied perspectives of art. In this case, students were motivated to explore the concepts and meanings materialized in Literature through the practice of drawing meaning-related memes. Alternatively, Silva and Nunes (2021) report the results of field research developed with pre-service English teachers concerning the immersion in the use of Internet memes. The authors conclude that the participants paid little attention to visual modalities of the memes they dealt with, and they also had difficulty implementing critical analyses.

The papers summarized in the previous paragraphs represent the potential of Internet memes as sources for developing school and varied educational scenarios in which students feel linked to classroom knowledge. Through diversified standpoints, the foregoing academic works help us illustrate and reinforce the relevance of Internet memes as means of contemplating students’ social identities and practices. The aspect we emphasize in this article, though, is that Internet memes are not neutral texts. They portray ideologies, and they serve the interests of different agendas; then, they have to be included and used in classroom-based contexts through critical frame of reference.

Methodology

This article is characterized as documentary research, through the collection of Internet memes, and as a critical analysis of a didactic sequence concerned with the concepts of critical reading and social justice in the context of English Language classes (JORDÃO, 2017). Similar to other kinds of texts, memes communicate and report pieces of information which are, according to Laville and Dionne (1999), one of the key aspects of those documents, once they can be seen as anything that produce meaning. Furthermore, documentary research deals with various formats, which go from audiovisual to print documents, and provide researchers with relevant insights. Flick (2009) asserts that the use of documents in research should take into account the subjects who produce them, the target aims and the public they are addressed to. Thus, in this research, memes were selected, codified, categorized and analyzed in the light of theories concerning Internet memes, critical reading and social justice.

Internet memes, critical reading, and social justice

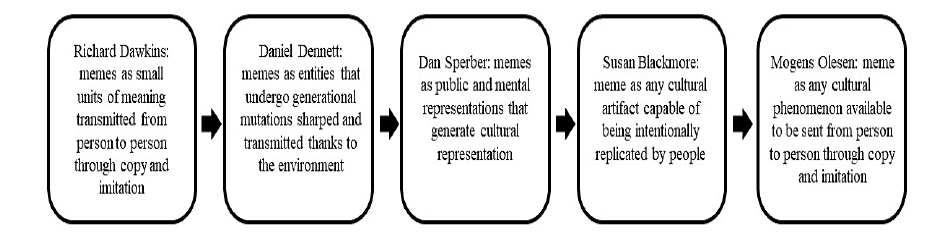

The origin of the term meme precedes the current context of global Internet. In fact, the first mention of that expression occurred in the book entitled “The Selfish Gene”, which was written in 1976 by the British Biologist Richard Dawkins. Briefly speaking, memes can be defined as small units of meaning transmitted from person to person through copy and imitation. As Dawkins (1976) stated, memes are like genes because they undergo mutations during the selective and transmission processes. Despite being the great pioneer to address the meme issue, the British Biologist was not the only one to provide contributions to this theoretical field. According to Díaz (2013), researchers from other backgrounds, such as Neurology and Psychology, also contributed to the development of concepts concerning memes, as illustrated below in Picture 1:

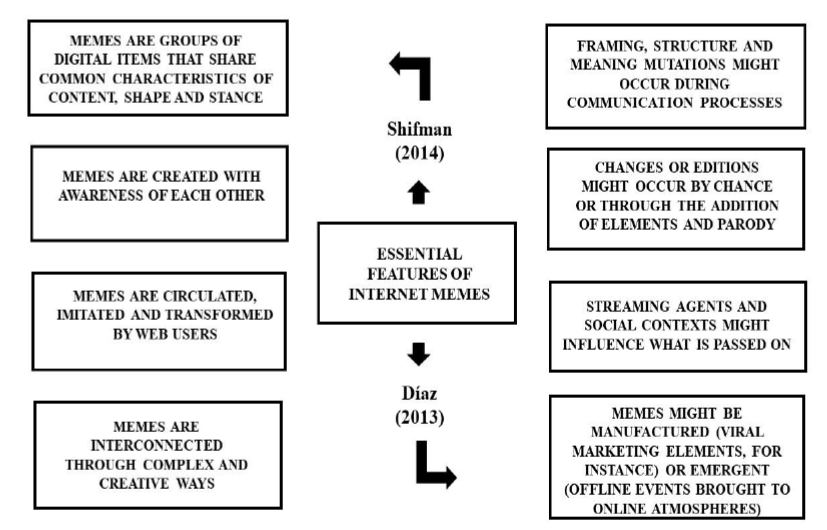

Knobel and Lankshear (2007, p. 199) defined memes as patterns of cultural information passed from person to person and which ended up generating, developing and reflecting thoughts and behaviors of social groups. They assert that the Internet has transformed memes into a very popular way of describing how ideologies can be quickly spread and assimilated on the Internet. Therefore, those definitions proposed by Lankshear and Knobel (2007) are similar to those introduced in Picture 1. According to Shifman (2014), memes can be expressed through jokes, rumors, videos, or websites that are shared through copy or imitation, covering micro and macro proportions. Internet memes have become essential communication tools in everyday life due to many aspects: ease of production, consumption or sharing, the possibility of adding references, representing groups, or expressing personal emotions, as shown in the following picture:

By examining the aspects illustrated in Picture 2, we can see that memes are always socially situated, and the impacts of their spread might diverge drastically depending on cultural contexts. Thus, people react differently when they interact with Internet memes because life backgrounds are not equal and consensual. Moreover, we should take a doubting attitude while using memes to perform our social practices once texts and actions are not neutral (MENEZES DE SOUZA; MONTE MÓR, 2018). We should wonder how the use of Internet memes may affect other people in different ways: am I corroborating with social ostracism by sharing a certain meme? Am I contributing to reinforce social brutalism while having fun with a situation used in a meme? Does this meme influence other people to marginalize cultures and social groups?

Those questions are not recipes or models to be followed, but they help us to illustrate how memes can be understood as legitimate texts and how they can be approached through critical stances in Education. Considering that memes can impact people’s life in diverse ways, we should consider that memes have the power of helping social groups to be heard as well as destructing social reputations and reinforcing ostracism (BOA SORTE; VICENTINI, 2020). By taking these issues into consideration, we defend that the uses of memes in Education are potentialized when they are grounded on social critical perspectives, which tend to consider texts embedded in contexts and as vehicles of meaning-making.

In face of this approach, we understand reading as a social practice. Reading has been taken through different perspectives throughout the years. Traditional theories advocate that readers play a neutral role while getting in contact with texts and that reading means recognizing linguistic codes. On the other hand, contemporary theories, such as the Freirean one, argue that reading is a social practice embedded in world concerns and ideologies (REIS, 2021). Freire provided another look at what was called as alphabetization and proposed that we should read the words and the world. That was the first generation of critical perspectives towards reading, when reading practices started to be seen as literacy, which means that it is concerned with identifying ideologies and social structures implicated in texts.

As time went by, other critical approaches were developed based on the Freire’s literacy theory. Kalantzis and Cope (2020) argued that language is imbricated in various literacies, which was coined as multiliteracies. Moreover, the meaning of being critical was expanded once reading was then seen as a meaning-making practice. The first generation of literacy, broadly known as Critical Pedagogy, was geared towards the idea that readers should be taught strategies to uncover the ideologies implied by the original authors. On the other hand, the second generation, named as Critical Literacy, is based on the conception that our life experiences influence the way we read texts and the meanings we make of them.

Social issues through Internet memes

We searched for images by using the expression “memes about” combined with the following terms: capitalism, social classes, democracy, social inequality, right-wingers, whitening, leftists, homophobia, Islamophobia, Latinos, gender roles, conservative people, politics, racism, sexism, socialism, and transphobia. In general terms, we chose memes which reproduced or criticized traditional stereotypes regarding the social issues previously mentioned. Moreover, we aimed to base our web search on memes portrayed in mainstream media and pop culture. The Critical Literacy perspective was also considered once we are dealing with social changes, cultural diversity, social equality, and political emancipation (KALANTZIS; COPE, 2020).

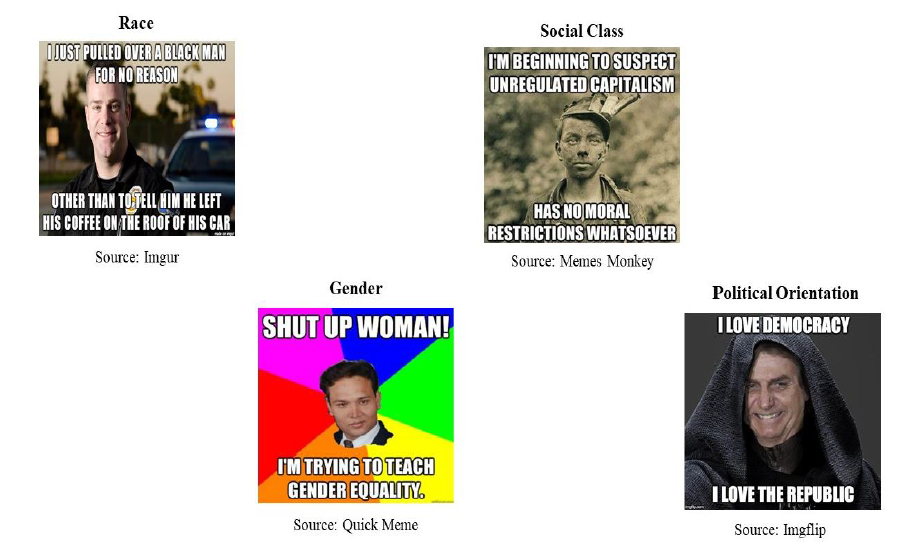

Based on the studies of social justice in a critical literacy perspective, we divided the selected memes into four groups: (a) race, (b) gender, (c) social class, (d) political orientation. These categories concern with what Collins and Bilge (2016) named as intersection. According to the authors, intersectionality is a tool for understanding and analyzing the world by considering how social divisions, both in individual and collective level as well as in local and global domain, promote scenarios of privilege and oppression. The term intersectionality emerged, as explained by Romero (2018), through the struggles for civil rights of American black feminists.

The intersectional approach represents the fact that those women faced oppression not only due to one social identity, such as, being a woman, a black woman or a poor woman, for instance. In an intersectional perspective, those women faced oppressive treatment in a crossing way, when all the identities are impacted by oppression. As Collins and Bilge (2016) explain, it is not about creating hierarchies of social identities but realizing that people are formed by many of them, an aspect that ends up influencing how they are positioned in the world. Although it is not possible, within the scope of this paper, to incorporate all the factors mentioned in the intersectionality studies, our intention is geared towards the analysis of how social identification change depending on the way people are represented.

We understand that the categories listed below intersect, cross and, ultimately, compete in individual and collective levels, although they are defined through the different contexts from which they originate. Through data collection, we selected eight memes for each category, which resulted in 32 files. In quantitative terms, this number does not represent the plethora of memes available online. However, given the qualitative domain of this research, our attention was geared towards the relevance of memes in English Language classes when they are used to analyze social issues through critical reading. In the following paragraphs, we provide an overview regarding how the memes that we selected through web search represent social issues:

(a) Race: in the memes selected, Chinese people were generally represented as being all the same, Muslims portrayed as terrorists, Mexicans as drug dealers and police officers using physical force against black people. Sentences as “I am not racist because I have black friends” and “racism is not a problem because it is a widely discussed topic” were commonly used. Examples of white people talking about racism and black men committing domestic violence were presented in the web search as well. Most representations referred to stereotypes addressed at marginalized minorities, such as blacks and immigrants;

(b) Gender: in this category, we selected memes in which men were aiming to teach gender equality to women; cisgender people were feeling persecuted by transgenders; women portrayed as those who cook and men as those who build; girls being taught not to accept gender inequalities; pictures in which boys wear blue clothes and girls wear pink ones; baby gender reveal party as a crime; and cisgenders defining transphobia. Most representations question gender roles and inequalities that are taken for granted by the society. In addition, cisgender's understandings of transgenderities are questioned;

(c) Social class: we selected memes which portray the divergence between how much consumers pay and how much workers receive for their jobs; the disillusionment of young people with capitalism; people’s resistance to accept and adopt social policies once they are considered to be socialists; the effects of capitalism on workers’ daily routine and life quality, resistance geared towards capitalist practices; the commodification of critical discourses about capitalism; social justice taken as a product; criticisms on the privileges of determined social classes throughout history. Most representations criticize the effects of capitalism on the most disadvantaged social classes, focusing specifically on the improvement of different socio-economic policies regarding proletarian work force;

(d) Political orientation: we selected memes that represented the combination of several prejudice practices by conservative people; memes illustrating young people getting to voting age but having only bad options; countries being considered as a democracy only because the president said it was one; memes satirizing the practice of not teaching people's rights in schools to make it easier for political leaders to deceive them; young people stereotyped as those who do not care about politics; comparisons between fictional and real political scenarios; memes satirizing political personalities known for their non-democratic actions as those who love democracy. In the picture below, we bring examples of memes selected in the four categories:

Above, in Picture 3, we are introduced to some of the memes selected via web search. The first category, named race, shows a meme in which a white police officer is depicted smiling towards a situation involving a black man. This first sentence causes certain expectations, especially when it comes to black people, once police aggressive approaches to them are common in society. As the justification comes, there is a break of expectation regarding racism, given that the police officer justifies that he warned the black man that he had left his coffee on the roof of his car. This example shows how the police violence against black people ends up being naturalized and becomes the first expectation in various contexts.

The second category, gender, displays a man demanding no disruption of his talk because he feels legitimized to teach gender equality to women. This example might be understood as a critique of a commonplace perspective of dismissing women’s authority to talk about their experiences. The ironic perspective is illustrated when it is said that the man was trying to explain about gender equality by taking over women’s voice. Therefore, in addition to putting up an authority speech towards women, the man is trying to teach gender equality to those who suffer the effects of a patriarchal society in everyday life.

The third category, named social class, exposes a picture taken by the sociologist and photographer Lewis Hine in which he illustrates the exploitation of children work force in American factories early in the Twentieth Century. The quote “I’m beginning to suspect unregulated capitalism has no moral restrictions whatsoever” shows that children had no time to realize that they were exploited at that time. The situation portrayed in the meme might be analyzed through a historical perspective once children have gotten laws that guarantee their rights to education and health care. However, even though History has shown us the existence of children exploitation, we have observed conceptions that dismiss children’s rights. Taking those aspects into account, teachers might illustrate that social class issues are still managed through predatory lines.

The fourth category, political orientation, brings a meme in which reality and fiction are mixed. The appearance of a Star Wars character, the self-proclaimed emperor Palpatine - known for being the last chancellor of the Galactic Republic, Lord of the Siths, and the most murderous and authoritarian ruler - was mixed with the image of the current president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro. The edition was geared towards the conception that Bolsonaro has been considered the most unpopular president at the end of the first year of government since the re-democratization movement, especially because of its constant authoritarian impulses. By comparing Palpatine to Bolsonaro, the photo edition aims to assert that both might have similar conceptions concerning democracy and republic.

Next section, we provide and discuss a didactic sequence based on a critical literacy perspective, which deals with the work on anti-racism attitudes using Internet memes in the classroom. Moreover, we aimed to propose activities focused on an expanded view of memes, taking into consideration the work with video remixes understood as examples of memes.

Memes in classroom practices

Entitled I have a dream, the following didactic sequence is prepared to be used during 10 classes that last 50 minutes each. The proposed activities are mediated through the reading of written texts and the production of memes and video remixes. The aim is to problematize some racist representations spread in the mainstream media through pedagogical activities that provide critical analysis of social issues. From classes 1 to 5, students are presented to texts that address issues of racism and anti-racism in society; and from classes 6 to 10, they are required to develop texts concerning those topics:

Table 1 I have a dream

| Class 1 | 1) The teacher exhibits eight advertisements spread regarding social issues;

2) Students get into groups to discuss the following questions: (a) How do you feel about the video? (b) Is there anything in the video that bother you? What is that? (c) Would the video influence you to buy the product or not? Why? (d) Do different identities influence the way people interpret those advertisements? |

| Class 2 | 1) Students share their answers on the questions proposed last class;

2) Students read the text entitled “Being Antiracist” and discuss it based on the following questions: (a) Are there relations between the videos and this text? (b) What are the relations among them? (c) What do they have in common? (d) Have you already heard about these different types of racism mentioned in the text? (e) What are the differences between them? (f) Do you consider important to understand the differences between them? Why? 4) Students read the text entitled “Anti-Racism Defined” in groups and answer the following questions: (a) Have you ever heard the term anti-racism? (b) What is the difference between racism and anti-racism? 5) In groups, students work on the production of video remixes that problematize racist advertisements based on an antiracist approach. |

| Class 3 | 1) Students present a proposal of a video remix, and the teacher makes comments and

suggestions on it. Students are asked to hand in a plan in class 5;

2) Each group receives eight memes and some questions: (a) Are these (anti)racist memes? Why? Why not? (b) How can we identify when a text is (anti)racist? 3) Students are asked to produce a draft of an antiracist meme based on the texts used in the previous class. |

| Class 4 | 1) Students present the draft produced in the previous class and the teacher asks for a

revised version due class 6;

2) The teacher might ask some questions: (a) As citizens, what can we do to fight against racism? (b) Why is it so important for all of us to take the responsibility of fighting against racism? (c) What should we learn with anti-racist activists? 3) The teacher proposes a group reading of the text entitled “What does it mean to be an anti-racist human rights defender?” and then presents the following questions: (a) Is there any risk to people who fight against racism? (b) How can we help people who are attacked by racists? (c) How can we help people who are racist to realize it? |

| Class 5 | 1) Students hand in an action plan to develop the production of a video remix based on the

teacher’s advisement. 2) The teacher could ask the students the following questions: (a) What do you know about doing interviews? (b) What strategies would you apply to do it? (c) What responsibilities should we take when interviewing someone? 3) Students read and discuss the text entitled “The Difference Between Structured, Unstructured & Semi-Structured Interviews” (POLLOCK, 2019). In groups, students are asked to create an interview plan concerning experiences of racism to be applied to relatives or friends. The interview should be developed in Portuguese, recorded and transcribe to next class. |

| Class 6 | 1) Students hand in a reviewed version of the interview plan and the teacher asks for a

preliminary version of the video remix; 2) Discuss the preliminary version of the memes; 3) Students work in groups to translate the transcribed interviews into English and prepare a presentation of the highlighted stretches. |

| Class 7 | 1) In groups, students present the highlighted points of the interviews and offer

the opportunity for their classmates to make comments on their productions;

2) In the following class, students will return the transcribed version of the interviews. |

| Class 8 | 1) Present the preliminary versions of the videos. The teacher and the classmates make

suggestions and comment on the productions;

2) Students should hand in the transcribed interviews; 3) Set the groups to present their production next class to students from other classrooms. Organize the groups for final advisement in class 9. |

| Class 9 | 1) Final discussions and preparation for the class presentation; |

| Class 10 | 1) The groups comment briefly on their production processes and exhibit

their videos and memes to other students;

3) The teacher hands in a piece of paper with questions for the students to evaluate classmates’ production and comment on classmates’ presentations. |

Source: elaborated by the authors

The activities proposed in Table 1 are not recipes to be followed once educational realities vary according to the social positions students and teachers occupy in the world. On the other hand, what we intend to present in this text is the exercise of questioning and doubting conceptions, readings, and thoughts. That exercise, based on a critical literacy perspective (MENEZES DE SOUZA, 2019; LUKE, 2012), provides teachers and students with the opportunity to review social issues they take for granted. Thus, according to this approach, students are encouraged to analyze their own realities before taking others’ realities into account.

The production of videos and memes - the main aspects of this didactic sequence proposal - can be developed through the principles of remixing to, according to Glăveanu, Saint-Laurent and Literat (2018), subvert images from the mainstream media. Burwell (2018) asserts that these remix practices make people rethink narratives and characters, which require the ability to read between the lines and propose modifications that differ from the original work. Furthermore, teachers can use the principles of the critical literacy once memes enable the re-appropriation and re-signification of speeches.

Luke (2012, p. 5) states that the critical literacy tends “[…] to analyze, critique and transform the norms, rule systems, and practices governing the social fields of everyday life […]". Thus, through the activities proposed in this article, we address the practice of reading critically by analyzing our own attitudes as well as those of other people. As Menezes de Souza (2019) argues, reading critically means to analyze our ideas and conceptions, that is, the understanding of reading as a process of meaning-making.

Final remarks

In this article, we presented an overview on theories concerning memes and Internet memes. Then, we discussed general conceptions of critical reading and social justice and how those issues could be covered in English Language Education using Internet memes. After that, we presented and analyzed documentary research in which we selected and organized Internet memes into four categories: race, gender, social class, and political orientation. Finally, we described and analyzed a didactic sequence, entitled I have a dream, in which we proposed activities for using Internet memes in English Language classes aimed to promote critical analyses.

While gathering papers for identifying how memes have been covered in Language Education, we found out that memes have not been consensus in terms of classroom environment. We consider that to be a relevant aspect nowadays, especially because meanings are made based on social issues that vary according to different realities. Taking those varied perspectives projected by the authors to classroom scenarios, we ponder that school teachers tend to plan the use of memes by considering their target aims as well as the concepts they create and/or accept regarding what language means.

Grounded on that notion of contextualized learning and teaching of language, we defend that classroom proposals, like this one we present in this article, have to be considered and analyzed based on the objectives the authors pointed out. Thus, we aimed at gathering perspectives that differ from one another in order to assert that depending on where we stand in the world we will understand language, learning and teaching in divergent ways. That is why asking students to participate in the classroom process is legit and necessary in this current period of collaborative, multimodal and participative cultures.

This idea of implementing “difference” as a concept be put into practice in the classroom is a mechanism of helping to break injustice. Our top aim, then, was to present memes as means of criticizing and revealing social issues that have been uncovered thanks to critical perspectives that started perceiving Education as an arena of ideologies. Thus, once teachers, students and people in general are not neutral beings, we should analyze which mechanisms and audiences we have been legitimating in society, and if that legitimacy validates the rise of social justice. By doing so, we help to guarantee Education as a vehicle of fostering equity in the world.

We ponder, once again, that we did not mean to offer recipes or models of learning and teaching language. Our plan was to propose classroom activities through memes that could make teachers consider whether their language classes are serving any mechanism of social justice or not. Our analyses pointed out that Internet memes are potential resources for developing critical awareness in Education, especially when languages are seen as vehicles of meaning-making. Moreover, Internet memes might be created and edited through multiple modes, which reinforces their potential of portraying different identities and diverse social realities. Based on what emerged during the analysis process, we believe that Internet memes might help teachers to explore social issues once they are seen as resources for meaning-making and critique.

Referências

BOA SORTE, Paulo; VICENTINI, Cristiane. Educating for social justice in a post-digital era. Práxis Educacional, S. l., v. 16, n. 39, p. 199-216, 2020. [ Links ]

BURWELL, Catherine. The Routledge Companion to media education, copyright, and fair use. USA: Routledge, 2018. [ Links ]

CETIC-BR. Tic Domicílios 2019: principais resultados. São Paulo: Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil, 2020a - Disponível em: Disponível em: https://cetic.br/media/analises/tic_domicilios_2019_coletiva_imprensa.pdf . Acesso em: 20 jan. 2022. [ Links ]

CETIC-BR. Tic Educação 2019: coletiva de imprensa. São Paulo: Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil , 2020b - Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.cetic.br/media/analises/tic_educacao_2019_coletiva_imprensa.pdf . Acesso em: 20 jan. 2022. [ Links ]

COLLINS, Patricia Hill; BILGE, Sirma. Intersectionality. Malden: Polity Press, 2016. [ Links ]

DAWKINS, Richard. The selfish gene. Londres: Oxford University Press, 1976. [ Links ]

DENARDI, Didiê Ana Ceni. Didactic sequence: a dialectic mechanism for language teaching and learning. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada. Belo Horizonte, v. 17, n. 1, p. 163-184, mar. 2017. [ Links ]

DÍAZ, Carlos Mauricio. Defining and characterizing the concept of Internet Meme. Revista CES Psicología, v. 2, 82-104, 2013. [ Links ]

DONGQIANG, Xie; SERIO, Ludovico de; MALAKHOV, Alexander; MATYS, Olga. Memes and Education: opportunities, approaches and perspectives. Geopolitical, Social Security and Freedom Journal, v. 3, n. 2, 2020. [ Links ]

FLICK, Uwe. Introdução à pesquisa qualitativa. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2009. [ Links ]

GLĂVEANU, Vlad Petre; SAINT-LAURENT, Constance; LITERAT, Ioana. Making sense of refugees online: Perspective taking, political imagination, and Internet memes. American Behavioral Scientist, v. 62, n. 4, p. 440-457, 2018. [ Links ]

HARTMAN, Pamela; BERG, Jessica; FULTON, Hannah; SCHULER, Brandon. Memes as Means: using popular culture to enhance the study of Literature. The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning, v. 26, p. 65-82, 2021. [ Links ]

JENKINS, Henry. Cultura da convergência. Tradução de Susana Alexandria. São Paulo: Aleph, 2009. [ Links ]

JORDÃO, Clarissa Menezes. Birds of different feathers: algumas diferenças entre letramento crítico, pedagogia crítica e abordagem comunicativa. In: TAKAKI, Nara Hiroko; MACIEL, Ruberval Franco (org.). Letramentos em terra de Paulo Freire. Campinas, SP: Pontes, 2017. [ Links ]

JORDÃO, Clarissa Menezes.; FIGUEIREDO, Eduardo Henrique Diniz de; MARTINEZ, Juliana Zeggio. Trapacear a linguística aplicada com Pennycook e Makoni: transglobalizando norte e sul. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, Campinas, SP, v. 59, n. 1, p. 834-843, 2020. [ Links ]

KALANTZIS, Mary; COPE, Bill. Adding sense: context and interest in a grammar of multimodal meaning. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020. [ Links ]

KAYALI, Nurda Karadeniz; ALTUNTAS, Ash. Using memes in language classroom. Shanlax International Journal of Education, v. 9, n. 3, p. 155-160, 2021. [ Links ]

KNOBEL, Michele; LANKSHEAR, Colin. Online memes, affinities, and cultural production. In: KNOBEL, Michele; LANKSHEAR, Colin (org.). A New Literacies Sampler. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2007, p. 199-227. [ Links ]

LAVILLE, Christian; DIONNE, Jean. A construção do saber: manual de metodologia da pesquisa em ciências humanas. Tradução de Heloísa Monteiro e Francisco Settineri. Porto Alegre: Artmed , 1999. [ Links ]

LUKE, Allan. Critical literacy: Foundational notes. Theory into practice, v. 51, n. 1, p. 4-11, 2012. [ Links ]

MATIAS, Keno Ivan. Integration of internet memes in teaching social studies and its relation to the development of critical thinking skills: a literature review. Global Scientific Journals, v. 8, n. 2, dez. 2020. [ Links ]

MENEZES DE SOUZA, Lynn Mário Trindade. Glocal languages, coloniality and globalization from below. In: GUILHERME, Manuela; MENEZES DE SOUZA, Lynn Mário Trindade (org.). Glocal languages and critical intercultural awareness: The south answers back. New York: Routledge, 2019, p. 17-41. [ Links ]

MENEZES DE SOUZA, Lynn Mário Trindade; MONTE MÓR, Walkyria. Still Critique? Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada , v. 18, n. 2, p. 445-450, 2018. [ Links ]

POLLOCK, Tom. The difference between structured, unstructured and semi-structured interviews (2019). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.oliverparks.com/blog-news/the-difference-between-structured-unstructured-amp-semi-structured-interviews . Acesso em: 25 jan. 2022. [ Links ]

REDDY, Rishabh; SINGH, Rishabh; KAPOOR, Vidhi; CHURI, Prathamesh. Joy of learning through internet memes. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy, v. 10, n. 5, p. 116-133, 2020. [ Links ]

REIS, Sônia Maria Alves de Oliveira. Paulo Freire: 100 anos de práxis libertadora. Práxis Educacional ,S. l., v. 17, n. 47, p. 238-258, 2021. [ Links ]

ROMERO, Mary. Introducing Intersectionality. Malden: Polity Press , 2018. [ Links ]

SHIFMAN, Limor. Memes in digital culture. USA: The MIT Press, 2014. [ Links ]

SILVA, Nayara Stefanie Mandarino; NUNES, Thainná Melo. Memes na formação inicial de professores de inglês. EntrePalavras, Fortaleza, v. 11, n. 1, p. 1-23, jan./abril 2021. [ Links ]

Received: July 18, 2022; Accepted: September 29, 2022

texto em

texto em