Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Acta Scientiarum. Education

Print version ISSN 2178-5198On-line version ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.41 Maringá Jan. 2019 Epub Oct 01, 2019

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v41i1.48175

HISTÓRIA E FILOSOFIA DA EDUCAÇÃO

Feeding the body and the soul in the middle ages: devouring and nourishing the Visio Tnugdali

1Departamento de História e Geografia, Universidade Estadual do Maranhão, s/n, 65055-970, São Luís, Maranhão, Brasil.

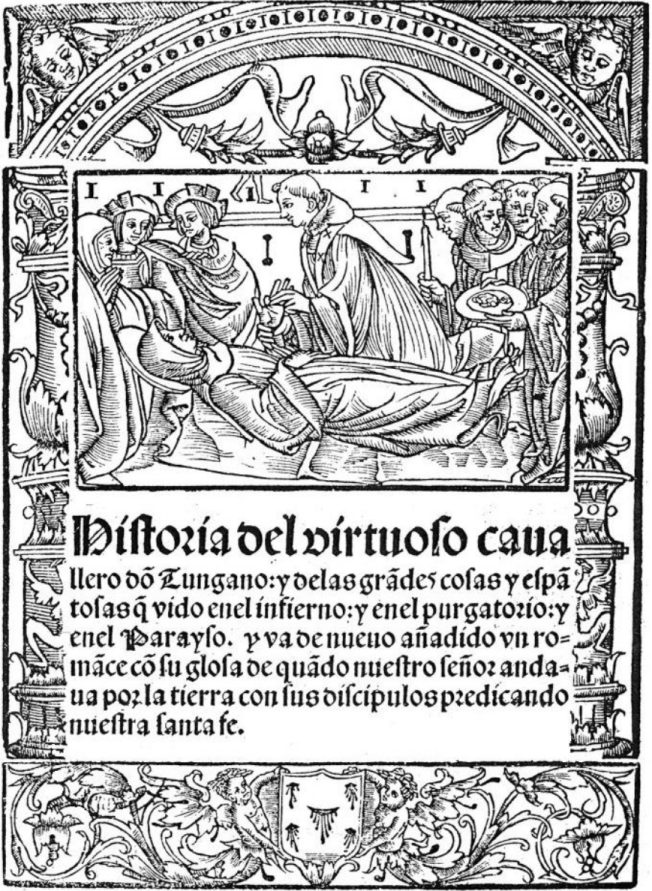

The purpose of this paper is to present the role of the food act in the images related to the work Visio Tnugdali, mainly the illuminated manuscript Getty Tondal (1475) in comparison to the Latin version by Marcus. These images are also compared with some woodcuts from the printed version in Germany, Ed. Speyer of the fifteenth century (De raptu animae Tundali et eius visione, 1483). The central theme of the narrative is the journey to beyond by a knight called Tundal, who undergoes a near-death experience and goes to the spaces of Purgatory, Hell and Paradise, accompanied by an angel, in order to make him aware of his sins. For this reason, he suffers during the journey some feathers, as well as, knows some delights of Paradise. The images and the narrative emphasize that punishment of humans is linked to the act of devouring, related to the education of humans for salvation. Humans suffer as if they were in a kitchen being cut, stuck, crumpled, melted, mass-transformed, and suffer again. The punishments are mainly related to the sins of lust and gluttony and could be suffered by clerics and laymen. The narrative also presents positive nutritional elements, for example, the host that the knight eats after his purification in the Beyond, represented on the front page of the Vision of Don Túngano (História del virtuoso cavaleiro Dõ Túngano, Toledo, 1526). Other positive food elements are related to Paradise, such as the tree of life and the source of living water, described in the Bible. Visual and mental food images related to kitchen space (referring to infernal places) and Biblical Eden are close to medieval everyday life, because the narrative sought to educate Christians for post-mortem salvation.

Keywords: food; education; salvation; knight Tundal

O objetivo deste artigo é apresentar o papel do ato da alimentação nas imagens relacionadas à obra Visio Tnugdali, principalmente o manuscrito iluminado Getty Tondal (1475), em comparação com a versão latina de Marcus. Essas imagens também são comparadas com algumas xilogravuras da versão impressa na Alemanha, ed. Speyer do século XV (De raptu animae Tundali et eius visione, 1483). O tema central da narrativa é a viagem ao Além de um cavaleiro chamado Tundal, que passa por uma experiência de quase-morte e vai aos espaços do Purgatório, Inferno e Paraíso, acompanhado por um anjo, visando conscientizá-lo de seus pecados. Por este motivo, sofre, durante a jornada, algumas penas, bem como conhece algumas delícias do Paraíso. As imagens e a narrativa enfatizam o fato dos castigos aos humanos estarem vinculados ao ato da devoração, relacionada à educação dos humanos para a salvação. Os seres humanos sofrem como se estivessem numa cozinha sendo cortados, espetados, amassados, derretidos, transformados em massa e voltam a sofrer continuamente. As punições estão relacionadas principalmente aos pecados da luxúria e gula, e poderiam ser sofridas por clérigos e leigos. A narrativa também apresenta elementos nutricionais positivos, como, por exemplo, a hóstia que o cavaleiro ingere depois da sua purificação no Além, representada no frontispício da Vision de Don Túngano (História del virtuoso cavaleiro Dõ Túngano, Toledo, 1526). Outros elementos alimentares positivos estão relacionados ao Paraíso, como a árvore da vida e a fonte de água viva, descritos na Bíblia (1995). As imagens alimentares visuais e mentais relacionadas ao espaço da cozinha (referente aos lugares infernais) e ao Éden bíblico estão próximas do cotidiano medieval, pois a narrativa buscava educar os cristãos para a salvação no post-mortem.

Palavras-chave: alimentação; educação; salvação; cavaleiro Tundal

El objetivo de este artículo es presentar el papel del acto de la alimentación en las imágenes relacionadas con la obra Visio Tnugdali, principalmente el manuscrito iluminado Getty Tondal (1475) en comparación con la versión latina de Marcus. Estas imágenes también se comparan con algunas xilograbaciones de la versión impresa en Alemania, Ed. Speyer del siglo XV (De raptu animae Tundali et eius visione, 1483). El tema central de la narrativa es el viaje al más allá de un caballero llamado Tundal que pasa por una experiencia de casi muerte y va a los espacios del Purgatorio, Inferno y Paraíso, acompañado por un ángel, con el fin de concientizarse de sus pecados. Por este motivo, sufre, durante la jornada, algunas plumas, así como, conoce algunas delicias del Paraíso. Las imágenes y la narrativa enfatizan el hecho de que los castigos a los humanos están vinculados al acto de la devoración, relacionada a la educación de los humanos para la salvación. Los seres humanos sufren como si estuvieran en una cocina siendo cortados, espetados, amasados, derretidos, transformados en masa y vuelven a sufrir continuamente. Las sanciones se refieren principalmente a los pecados de la lujuria y gula y podrían ser sufridos por clérigos y laicos. La narración también presenta elementos nutricionales positivos, como, por ejemplo, la hostia que el caballero ingiere después de su purificación en el Más Allá, representada en el frontispicio de la Visión de Don Túngano (História del virtuoso cavaleiro Dõ Túngano, Toledo, 1526). Otros elementos alimenticios positivos están relacionados con el Paraíso, como el árbol de la vida y la fuente de agua viva, descritos en la Biblia. Las imágenes alimenticias visuales y mentales relacionadas con el espacio de la cocina (referente a los lugares infernales) y al Edén bíblico están cerca del cotidiano medieval, pues la narrativa buscaba educar a los cristianos para la salvación en el post mortem.

Palabras-clave: alimentación; educación; salvación; caballero Tundal

Introduction26

Truly I say to you,

He who has faith in me has eternal life.

I am the bread of life [...]

I am the living bread which has come from heaven:

if any man takes this bread for food he will have life for ever. (Jo 6, 47-51).

The Visio Tnugdali is part of a set of texts composed primarily by monks for the purpose of contributing to the evangelization of Christians, showing to the faithful what the post-mortem sites would look like, the joys of the elect in Paradise and the punishments of sinners in Hell. The twelfth century was the apogee of these visions, their “[...] century of gold” (Delumeau, 2003, p. 80). The Visio Tnugdali is the best known of them (Wieck, 1990; Dinzelbacher, 1992) and one of the accounts that later gave rise to Dante’s Comedy.

The Visio was very popular as the protagonist, a sinful knight, goes to the Beyond and suffers various penalties in his body due to his sins, even seeing the figure of Lucifer in Hell. It also shows, in more detail than other accounts, what would be the Paradise spaces (Delumeau, 2003), divided into Walls, with edenic aspects, and also of a city, as we can see in the description of the Paradise in the Book of Revelation. In the representations of Paradise by various artists in the fifteenth century, such as Fra Angelico in The Last Judgment (1432-1435), in the detail referring to the place of the righteous, the Walled Paradise is identified with a fortress from which light emanates27.

The manuscript was composed of an Irish monk from Cashell (Seymour, 1926), who was in Regensburg in southern Germany. It is dedicated to Gisela, abbess of the monastery of Saint Paul, he being of the monastery of Saint Jacques. The fact that Mark is so far from his hometown expresses the desire of many monks, who considered self-exile from their homeland as a penitential movement in pursuit of purification (Pontfarcy, 2010a). His congregation was part of the Schottenkloster (installation of Irish and Scottish monasteries in Germany). Marcus favored the Gregorian or Papal Reform movement, which at the time was resisted by the Irish church (Pontfarcy, 2010a).

In this period, the twelfth century, visionary accounts were considered true, many of them of popular origin, and later reinterpreted by a religious authority (Le Goff, 1994). The truth is that many visions circulated which had mainly men as protagonists: religious, knights (such as Tundal and Owein), peasants (Turkill) (Dinzelbacher, 1986, 1992; Nogueira, 2015).

The Visio Tnugdali had over one hundred and fifty copies (Palmer, 1982), and in the Latin language alone, fourteen lost manuscripts28 (Wieck, 1990), with great circulation in vernacular languages, having been translated into fifteen languages (Cavagna, 2008)29, and was among the first printed books. At the beginning of the work Marcus makes a prologue with a long description of Ireland and mentions its administrative structure, based on archbishops. In his text, the emphasis is on correcting sins. For this reason, the first chapters, referring to the space of the ‘superior hell’, mention the punishments of sinners, with titles such as ‘The first penalty for murderers’ (De prima pena homicidarum), ‘The penalty for the insidious and perfidious’ (De pena insidiatorum et perfidorum), ‘The misers and their penalty’, (De avaris et pena eorum), ‘The penalty for gluttons and fornicators’ (De pena glutonum et fornicantium). In Marcus’s account, therefore, the emphasis is on punishments of murderers, perfidious, avaricious, gluttonous and fornicators, among others (Wagner, 1882).

Due to its popularity, the narrative was disseminated without the Latin prologue in the account of the Cistercian Hélinand de Froidmont still in the twelfth century. It was then inserted into the Speculum historiale (Mirror of History) from the Dominican Vincent de Beauvais (c. 1250). In these versions there is an emphasis on sins and punishments. Hélinand’s Latin version of Froidmont, later incorporated by Vincent de Beauvais, was called De raptu animae Tundali et eius visione (1483) (The abduction of Tundalo’s soul and his vision), being inserted in book 28 (or 27 in some versions) of the Speculum historiale30.

This version was translated into French in the fourteenth century, under the title of Miroir historial by Jean de Vignay (2008) (from the Order of Hospitallers), and dedicated to Joan, wife of the King of France, Philip VI of Valois (1328-1350) (Cavagna, 2008). The chapter titles referring to the Visio Tnugdali, compared to the same chapters of Marcus quoted above are, in archaic French, the following: De la valee horrible e du pont estroit, De la beste monstreuse et horrible e Du four plain de flambe31 (The horrible valley and the narrow bridge, The monstrous and horrible beast, The oven full of fire). Thus, it is possible to perceive two different emphases in these versions in relation to the infernal spaces: in Marcus, the emphasis is on sins and their correction, and in Vincent de Beauvais/Hélinand de Froidmont, translated in French as Miroir Historial, the emphasis is on the spaces and monsters (Cavagna, 2008).

As a way of approaching the report mainly to the listeners, since it was mainly heard by the population through preaching, and also, in some cases, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, served as private devotion of the nobles, it was important to bring the universe of postmortem as close as possible to people. In this sense, there was the appeal to the sensations of the five sense organs in the narrative (sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell). Imagining the sensations helped each one to materialize what the punishments to the knight were like.

It is important the mention of known elements in the Beyond, such as everyday actions, especially related to the kitchen. For Dias (2015), the condemned, in the reports about ‘hell’, are as if exposed in a butcher shop, devoured and excreted, in a recurrent and dysfunctional digestion, representing an alimentary dystopia.

In the early versions of the Visio Tnugdali, composed in the twelfth century, the places of the Beyond are divided into Upper Hell (for those not yet condemned) and Lower Hell (for those who have not repented of their sins and will be tormented forever) (Wagner, 1882). In later versions of the narrative, inspired by Marcus and composed in the fifteenth century, the ancient Upper Hell is called Purgatory. This is the case of the Duchess of York’s manuscript, entitled Les visions du chevalier Tondal (The visions of the knight Tondal), of the Portuguese version of codex 244, Visão de túndalo, both composed in the fifteenth century, and of the Visión do caballero don Túngano, text printed in Toledo in the sixteenth century.

Punishments are linked to sufferings that alternate fire and ice, darkness, smell of sulfur, gnashing of teeth. The infernal spaces in the Visio are described with objects such as frying pans, cauldrons, burning houses, ovens, iron forges, among others. And we have verbs like cut, stick, skin, crack, melt, knead, dismember, strain. Some objects used to punish are knives, cleavers, harpoons, hammers, scythes, among others (Esteves Pereira, 1985).

Sinners are tortured on the basis of the Ten Commandments (e.g. thieves, murderers) and also the seven deadly sins (Pontfarcy, 2013; Baschet, 2014). The sin of lust is associated with eating, so one of the punishments, of “gluttons and fornicators” in Fristin’s House (an oven), is to be roasted. These images appear both in the Latin text originally written by Marcus in the twelfth century and in other versions of the narrative.

In the fifteenth century, the Visio also contributed to private devotion, with the presence of text and image (with twenty illuminations) in a manuscript commissioned by Duchess Margaret of York (1446-1503), which aimed to stimulate the religiosity of her husband, Duke Charles the Bold. In this respect, this version seeks to bring the universe of Tundal closer to that of the duke, emphasizing the fact that the former is a great lord. It is interesting that the manuscripts composed to the duchess had her emblem ‘bien en aviegne’, with floral border (see margin of Figures 1, 4 e 5).

The text Les visions de Tondal reminds us all the time of the protagonist’s knighthood, and the work is a kind of mirror of princes, with the didactic function of extolling knightly values, such as the knight’s power, bravery and courage, that should be subjected to divine mercy (Cavagna, 2008). The work follows Marcus’s account, but with some minor modifications, and became known to contemporaneity as The Visions of the Knight Tondal or Getty Tondal, and is currently deposited at the Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, USA (ms. 30).

There were also printed versions of the Visio Tnugdali, the first incunabula, inspired by the Vincent de Beauvais version32, which circulated mainly in Latin and German between the late 15th and early 16th centuries, also with twenty or twenty-one woodcuts33, depending on the Speyer edition (see Wieck, 1992, p. 127, nt. 16).

In this article we will analyze images of the Duchess of York’s manuscript (The Visions of the knight Tondal, 1475), compared to some woodcuts of the account in print, in one of the incunabula that circulated in Germany in Latin, De raptu animae tundali et eius visione (The abduction of Tundal’s soul and his vision) (De raptu animae Tundali et eius visione, 1483), that emphasize the act of eating and/or being devoured. Devouring encompasses the action of greedy, uncontrollable, uncivilized eating. In the Visio, this action occurs through fierce animals and the ‘devil’ against sinful humans. Positive food elements related to ‘paradise’ and Christ will also be analyzed, such as the host34, the source of living water and the tree of life, which also appear in the account and the images.

Food, sin and salvation in the Visio tnugdali

The images in the medieval could be mental and visual images. The latter provided the viewer with the ability to transfer, through his or her gaze, to the universe of the image, starting from the visible world and going to the invisible, God-bound world (Schmitt, 2002b; 2007). As the story was commissioned by Duchess Margaret of York, there are elements in the image that made the duchess and her neighbors identify with the scenes. Thus, in Figure 1, the hostess appears dressed in a pointy hat, worn at the time, and which Margaret of York herself also wore in paintings depicting her, such as an anonymous portrait of 1468, which is currently in the Museum of Louvre in Paris.

About the Duchess Margaret of York, her brothers were kings of England (Edward IV, king between 1461 and 1483 and Richard III, 1483-1485) and the marriage (1468) took place in the context of the Hundred Years War, being the Duke Charles the Bold, her husband, in conflict with the King of France, Louis XI (1461-1483). Margaret was Charles’s third wife, who already had a daughter from her first marriage. Because she was unable to give birth to an heir, the duchess was neglected by her husband and saw him only a few times a year (Blockmans, 1992). The Visio’s commission was to encourage Charles to be more connected with spiritual things than with earthly things. Two years after the composition of the work, however, the duke died in battle against the king of France, Louis XI.

The text was compiled by David Aubert35, with illuminations by Simon Marmion (Aubert & Marmion, 1990), already known in his day “[...] by Jean Lemaire of Belges as prince of illuminators” for the quality of his work (Pontfarcy, 2010a, p. XX, emphasis added). Both David Aubert’s letters and Marmion’s illuminations (Pontfarcy, 2010a) were much appreciated at the time of writing.

After the prologue, about the cities of Ireland, maintained in the French version of the duchess, the narrative, following the Latin text of Marcus, begins with a scene involving a dinner. Tundal36 inteds to collect the debt of a friend who owed him three horses (trium equorum debit erat), and could not yet repay the debt, which makes the first annoyed, at which time the host invites him for a meal before departure. This trait of hospitality, a medieval element of the nobility, also appears in courtly novels (Busby, 2012).

At this moment, when Tundal was going to reach for the food, he felt bad and cannot, since “[...] divine pity acted and could not return to the mouth the hand that he had extended [...]” (Set pietas hunc appetitum cita qua occasione percussus manum, quam extenderat, replicare non poterat ad os suum (Wagner, 1882, p. 8) (Figure 1).

According to Marmion’s (1990a) interpretation of the image of the dinner:

The copyist, David Aubert writes in the first lines of the red-lettered manuscript38: ‘Here begins the book of a knight and great lord of Ireland’ (Figure 1). The images always represent more than a mere illustration of the text, reinterpreting it and broadening its meaning. It can be observed that Tundal is the main character of the scene. Looking at Figure 1, the knight is in the center of the table and our gaze goes to him as we contemplate it. Extending the data of history by adding details that are not in the text of the Visions of the Knight Tondal, written by David Aubert to Margaret of York, in Marmion’s illumination (1990a) there is a rectangular table, which reinforces the medieval hierarchies. Tundal’s friend, the host, is at the head of the table, his wife by his side and other guests around him, as well as two servants preparing the food, separated from the table by an open counter (by which we can identify that the latter are in the kitchen space), another young man serving and a squire in front of the table.

Tundal reaches out to pick up the food, according to the text, but fails and falls (Figure 2). At the scene, when the knight feels bad, and according to the manuscript, he asks the host’s wife to take care of his ax. According to the twelfth-century Latin text in which David Aubert was inspired: “Take care of my ax because I die” (custodi, inquiens, meam seccurim, nam ego morior) (Wagner, 1882, p. 8). In Marmion’s scene (1990a, Figure 1), this object is leaning against the wall behind the hostess39. It is noteworthy that, already in the period of composition of the Visio by Marcus (12th century), the sword was considered a ‘nobler’ weapon than the ax. This element may emphasize the knight’s appearance as a sinner.

The next scene of this work dedicated to Duchess Margaret shows Tundal on the ground, surrounded by various people, men and women (f. 11) (Aubert & Marmion, 1990). It is important to highlight the presence of the worried women contemplating Tundal, one of whom, kneeling near the knight’s fallen body with prayer-like hands, is the same as in Figure 1, in a costume similar to that of Margaret de York (pointy hat). Behind her, another lady wears the same kind of hat. The concern of those present seems to indicate the importance of the knight and his affection for him.

Another representation of the scene appears in one of the incunabula printed in Germany in the 15th century, in a version circulated in Latin:

In the woodcut (Figure 2), there is no female image, only men. The table is set, with a plate of meat-like food, and Tundal is falling, which can be seen from his open arms and his head turned to the floor. A window can also be seen, from which comes an arm in the sleeve of probably a tunic (which we do not see) and a hand, a possible allusion to the divine role in this episode, mentioned in Marcus’s text with the expression “[...] divine piety” (Wagner, 1882, p. 8).

The food in the images seems to be meat. In the Vision de Tyndal, the fifteenth-century version of the narrative produced in Languedoc, it is mentioned that the knight could not put food or meat (vianda) in his mouth ([...] non poc portar la vianda em sa boca) (Jeanroy & Vignaux, 1903, p. 59 ). In the narrative about Tundal contained in the Miroir historial, from the fourteenth century, translation of the Speculum historiale, by Vincent de Beauvais, it is explicitly mentioned that the food the knight cannot eat is meat: “[...] et fu a la main qu’il avoit estudendue la viande” (and it was the hand that he had stretched out to the meat) (Vignay, 2008, p. 66).

Meat is a food that gives strength and sustenance, linked to warriors, nobles, the only ones in feudal society who could perform hunting in rural properties, which would have occurred around the ninth-tenth centuries (Guerreau, 2002). Peasants who performed this practice were punished. Meat was the quintessential food intake of the aristocracy, while peasants mainly ate bread and vegetables, especially from the central Middle Ages (Montanari, 2002). In the medieval period, it was associated with pleasure, as it guaranteed warmth and was therefore considered aphrodisiac. It was linked to the sin of gluttony and so, according to the monastic ideology that valued humility, it was recommended not to be consumed by the monks.

Thus, it was believed that avoiding meat was a way of maintaining chastity (Montanari, 2016). Instead, religious should feed on bread, salt and water, occasionally adding fruits and vegetables. In the case of the Benedictine monks, they could have two meals a day with two plates of cooked food. Hermits, on the other hand, often consumed raw, that is, uncooked food, which has become fashionable today among certain groups (Adamson, 2004).

“Food was not just the main material concern of the medieval people; eating practices - fasting and feasting - were at the heart of the Christian tradition” (Bynum, 1985, p. 139). Meat consumption was approved in the case of patients, exactly to restore their health and at certain festive times, such as Christmas, when stimulated by Saint Francis, for example (Montanari, 2016).

For many medieval people, gluttony was the cause of original sin, for Eve was tempted by the serpent to eat the forbidden fruit to gain knowledge. After eating it, Adam and Eve realized they were naked, which emphasizes the link with sexuality. Most medieval theologians and philosophers, with the exception of Peter Abelard and his disciples, would argue that “[...] original sin is linked to sexual sin through concupiscence” (Le Goff & Truong, 2006, p. 52).

Moreover, unlike the abundant food they had in Eden, the Creator, in expelling them, explains that from then on the woman would give birth in pain, and the man would only get food from the sweat on his face: “I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children. [...] By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread [...]” (Gen 3: 17-19, emphasis added). This statement highlights the difficulty of obtaining food in the biblical conception.

On the sin of gluttony, St. Jerome (4th century) stated that a stomach full of food and wine would lead to laziness. Already Isidore of Seville (6th century) made a connection between gluttony and laziness as a consequence of the proximity of the stomach to the sexual organs (Adamson, 2004). Gluttony is still associated with the throat/mouth; Similarly, carnal sins related to gluttony and sexuality are also related to drunkenness (Le Goff & Truong, 2006; Schmitt, 2005). For this reason, Christian authors encouraged fasting as a way of nourishing the spirit, leaving the body clear and light to receive divine truth. Hence the need for fasting in the forty days of Lent before Easter, according to the Christian calendar40. Classical medicine also said that food intake should be moderate, as in the chapters of diet and personal hygiene of Galen and Hippocrates (Adamson, 2004).

Bynum (1985) mentions the importance of the feminine and its relation to the symbolic value of food; through food, the woman acted upon herself and society. Some mystics in this period, seeking closeness with God, refused to feed themselves, living almost all the time fasting, and are now known as ‘anorexic saints’. An example is Catherine of Siena (m. 1380), who chewed raw vegetables or fruits, which soon after she spat or vomited (Lawers,1994; Soares, 2008)41. Her relationship with nutrition brought her closer to the divine, for in eating the host she received the blood of Christ in her mouth (Bynum, 1985). These women transformed their body into food, a kind of imitatio Christi, for “[...] from the body of the holy women, from their mouth, from their chest, from their fingers, blood escaped, but also, miraculously, perfumes, oil and milk” (Lawers, 1994, p. 223). In this way, the deprivation of fleshly food strengthened the saints’ faith and mystical experience with the divine, turning themselves into a food vessel.

The relationship between body and soul in medieval times is often represented in the opposition between the terrestrial foods, for the body, and the spiritual foods, the deep prayers or thoughts, which are served at the so-called banquet of the soul (Schmitt, 2002a). In a sixteenth-century play by Gil Vicente, Auto da Alma (1987), Christ’s sufferings are shown on a table to the soul after it has managed to deviate from the temptations offered by the Devil and has attained the way of salvation with the angel’s help. On the table are the objects that represent the martyrdom of Christ (the crown of thorns, the crucifix).

The flesh that Tundal cannot take (Figure 1) is therefore associated with two capital sins, gluttony and lust, and it is no coincidence that one of the punishments in the narrative is directed at the sins of ‘gluttons and fornicators’, This shows how these two faults were interconnected in the medieval imagination. The monasteries sought to control their appetite through silence, sobriety in the cafeterias and the consumption of lighter foods such as fish, cheese, eggs, and the practice of fasting was recommended, as it purified the body and approached the divine things, thus calming the tendency to carnal sin.

In Medieval and Modern times, manuals were made of the correct ways of behaving at the table, which contributed to the control of the aggressiveness of the nobility over time and also their distinction from other social groups, such as peasants, who did not know these rules (Montanari, 2008; Elias, 1994).

Tundal cannot eat during dinner, possibly because he is a sinner, hitherto linked to an incorrect type of food, and had to go through a purification process. That is why, after his journey to the Beyond, narrated also at the beginning of the account, the first thing he asks for is the body of Christ, spiritual nourishment, which guarantees immortality, which he consumes with wine, representing the blood of the Savior, related to the sacrament of the Eucharist, the body and blood of Christ symbolically purifying Christians.

Interestingly, the narrative of Tundal tells that he feels bad at dinner. Then there is an explanation of the time when he experienced near death, that is, the account explains that he was unconscious for three days, from Wednesday to Saturday, not being buried by the heat in his left chest (Carozzi, 1994), despite presenting the signs of death: “[...] the hair whitened, the forehead was hard, the eyes were wandering, the lips paled [...] the limbs of the body became rigid” ([...] crines candent, frons obduratur, errant occuli, nasus acuitur, pallescunt labia [....] corpora membra rigescunt” (Wagner, 1882, p. 8).

At this point the account anticipates the story, that is, it shows that the knight returned saved, regenerated, and was now asking for the host, which he received, and took with the wine, and thanking the divine mercy, to recount after that in detail the episodes passed by the soul in the infernal and paradisiacal places.

We see the presence of the host in the following image of a version of the Visio printed in Toledo in 1526:

The Figure 3 contained in the sixteenth century woodcut is on the frontispiece of the printed edition in Toledo. In addition to the image, there is an initial text that synthesizes the narrative. In larger letters: Historia del Virtuoso Cava [...], and then the word ‘knight’ continues. And the rest of the text in smaller letters: “History of the knight Don Túngano and the great and amazing things he saw in hell and Purgatory and Paradise [...]” (Pontfarcy, 2013, p. 1), showing a scene dating back so much to the beginning of the narrative, when the knight falls to the ground in a kind of coma after trying to approach the food on the table42 as to the end of the narrative, when, shortly after ‘waking up’ from his out-of-body journey, he asks to take the body of Christ.

In the image, a religious man holds his hand and possibly approaches him to hear his confession. The knight, with a hood on his head, a reference to penance, is surrounded by well-dressed (noble) women and ecclesiastical men, for the latter wear religious robes and are tonsured. One holds a plate with the host. You can see here the contrast between the first images, Figures 1 and 2 (when Tundal would approach material food, related to flesh-matter and flesh-body) and Figure 3. In this representation, after returning regenerated from his journey to the afterlife, after suffering for his faults, being convinced by the angel’s arguments and visiting paradisical places, the knight asks to consume spiritual food and make confession, an important action recommended by the Church. Moreover, as proof of his regeneration, he gives his goods to the poor:

And then this knight Túngano apportioned [his goods] and made alms of all that he had, and gave them to the poor, and mended his life, which well admonished and astonished came from the pains which he had suffered and seen. And very great taste, pleasure and joy he had from the great goods, treats and things he had seen in the Glory (La Visión de Túnano, 2012, p. 1, emphasis added)43.

The text highlights the alms granted by Tundal after his return from the Beyond, and the fact that he gave goods to the poor by virtue of the delights he had lived, not mentioning the punishments in this passage of history, which, however, were crucial as well as pedagogical means for the rider’s conversion through penalties often linked to devouring. It can be said that on this educational path, upon his return, Tundal now wears the cross in his garments, proving that he had become an exemplary Christian (Pontfarcy, 2010b).

Among the torments felt by the soul in the narrative, it is possible to notice that the punishments are very close to the act of eating, that is, Tundal and other souls are devoured and their bodies go through the digestive process of the monsters, as well as being treated as food to be eaten, prepared to be consumed. The purpose of the narrative is that, at the end of this process, of which devouring is an important element, the former sinner knight ‘dies’, that is, his sins be eradicated and he is reborn as a new man, thus saving him and other Christians to whom the report was transmitted.

In this sense, purification in the afterlife is obtained through suffering in the infernal spaces, suffering related to fire and the decomposition of souls so that the repentance of old faults and a new birth could occur, as they do with the knight Tundal. He wakes up from his experience after three days in the hereafter (an analogy to the resurrection of Christ). Hence the souls are cut, skewered, among other actions.

The medieval conception woven since the Middle Ages is in the existence of two judgments. One, right after death, the Individual Judgment, and the Collective Judgment, after Christ’s Second Return (Parusia), definitively separating the saved and the damned (Le Goff, 1993). Therefore, after death, the soul is able to feel as if bodily.

In this sense, those who suffered in their living bodies (such as martyrs and saints) will have rewards in the other world, while those who did not care for the body and did not abstained from the pleasures, nor did the penances indicated by the clerics through confessions (made compulsory since the 4th Lateran Council in 1215) will suffer corporal punishment for a certain period in Purgatory or eternally in Hell. Time spent in Purgatory could be minimized by the action of the living through donations and masses for the soul of the deceased (Le Goff, 1993).

On the character of fire in infernal spaces, according to theologians, this would be much more intense than the worldly, which gave a pale impression of the potency of this postmortem punishing element. In addition, it was characterized by a negative aspect, so it prevented brightness but maintained darkness, which increased the fear of punishment (Baschet, 2014).

Tundal, thanks to divine action, has the opportunity, through experience in the Beyond, to feel the penalties to be able to repent of them and to “[...] mend his sins and his wickedness,” as one manuscript points out which circulated in Portugal (Esteves Pereira, 1895, p. 101).

The process of transformation of souls by punishment occurs both by devouring and by the action of fire. Even when the soul leaves the body, the demons that filled the streets and squares and wanted to take it to Hell claim that it was “[...] food for unquenchable fire” (cibis ignis inextinguibilis) (Wagner, 1882, p. 10). In the Portuguese version, demons surround the soul when it comes out of the body after the knight had felt bad (during dinner, referring to Figure 1 44), and ask him, among other things: “Where are [...] ‘your eating and drinking’ [...] that gave little to the poor?” (Esteves Pereira, 1895, p. 102, emphasis added).

Flames transform raw foods to be digested; the same happens to sinners who change their behavior after suffering, being eaten by monsters and being modified, melted by fire, a punishment that aids education for salvation.

The transformation that souls undergo in their bodies also approximates the punishments of the organ of touch, as the bodies are dismembered. Through physical trial, sinners are cut, spiked, baked, strained, and made into a pulp. In addition, all these actions are close to the medieval daily life and kitchen space, which was known to the entire population. To the medieval, open spaces were associated with Hell (like the mouth) (Baschet, 1985) and closed to Paradise (like the walls of Gold, Silver, and Gems that Tundal sees in this place).

We can observe the relation of the spaces of the Beyond in the Visio Tnugdali with the devouring and nourishing in Table 1.

Table 1 Devouring and nourishing in the infernal and paradisiacal spaces of the Visio Tnugdali

| Spaces | Devouring or nourishing |

| Purgatory | Tundal and other sinners are ingested by monsters and tortured with torture objects which liken humans to food to be prepared: they are cut, mashed, strained, boiled, baked. |

| Hell | Lucifer eats, crushes humans like grape berries and spits them to various places in hell. Lucifer is also roasted on the iron grill. |

| Pre-paradise (a kind of Limbo) | Divided into two parts: 1. the ‘not too bad’ suffer wind, rain, hunger and thirst: food and water deprivation 2. the ‘not very good’: presence of the fountain of the water of life |

| Paradise | Divided into 3 walls: silver, gold and precious stones according to the purity of its inhabitants - on the golden wall: tree - association with the Catholic Church and the tree of life. Nutrition is carried out materially or spiritually through the fruits of this vegetable. |

Source: Author

It is important to highlight that the protagonist suffers almost all the penalties, being spared from the initial three (aimed at the murderers, the perfidious and the proud) (Pontfarcy, 2010b)45. For example, in the punishment of the murderers, to whom, according to the angel, Tundal should be subjected but is not suffering as he merely observes the scene, the condemned are placed in a valley with a round iron covering full of burning coals (Pontfarcy, 2010b). From this valley came a very smelly odor and the souls were thrown and burned, melting, because “[...] petty souls [...] burned, boiled as the oil boils in the sartan” (frying pan) (Esteves Pereira, 1895, p. 103), according to the fifteenth century Portuguese version.

They were also percolated like wax through a cloth and then revived and everything started over. In the penalty for the proud, they should pass over a bridge. The angel takes Tundal over this bridge and so he is free from punishment (f. 15v) (Aubert & Marmion, 1990). In a number of other descriptions, souls are eaten by monsters, ground, oven-baked, strained, mashed into a pulp, as Table 1 points out, with regard to the places of Purgatory and Hell.

As mentioned, in Purgatory humans are tortured with kitchen tools and digested by demons and monsters (Baschet, 2014). Tundal himself suffers, due to his sins, the punishments aimed at thieves, avers, gluttons, and fornicators and lustful (Wagner, 1882; Pontfarcy, 2010b).

In the sin of gluttons and fornicators, souls and Tundal himself suffer in a place called Fristin’s House, which is actually an oven: “[...] the great open house” (grant mainsion ouverte) (Pontfarcy, 2010b, p. 60), it was “[...]like a very high mountain and all round like an oven” (aussi comme une bien haulte montagne et estoit toute reonde comme ung four) (Pontfarcy, 2010b, p. 60-62). Marcus’s Latin text mentions that flames could never quench gluttony (vero vastum condebatur incendium, aviditas cinexplebilis semper inerat cibi, nec tamem satiari poterat nimietas gule) (Wagner, 1882, p. 24). Tundal is dismembered by demons, who have in their hands iron forges and other instruments to torture and torment souls, and is dragged towards the fire. (Pontfarcy, 2010b).

“What can we say about the occupants of this terrible house?” (Pontfarcy, 2010b, p. 64), questions the Visio. It mentions that the men and women in this place had worm-infested sexual organs, for “[...] the worst torment these souls suffered in this place was the atrocious sufferings in their sexual organs, which were full of and teeming with worms.” (le plus grant tourment que icelles ames souffroient ne que leans fuist estoit em leur membre de nature quy leur estoit pourry et plainde vers) (Pontfarcy, 2010b, p. 64)

The text of the Duchess of York, following the Latin, stresses that among these souls were secular and religious men and women (hommes et femmes seculiers et de religion) and were attacked by snakes, serpents, and frogs, which made their suffering unbearable (Pontfarcy, 2010b). In addition, those who

[...] wore the habit of religion pretending to lead a holy life, the latter were in particular - the religious men and women who had committed the sin of lust, who endured the worst sufferings’ (porte habit de religion en semblant de sainte vye; certes iceulz estoient les plus fort tourmentez et quy plus de meschifiefs enduroient) (Pontfarcy, 2010b, p. 66, emphasis added)

The Visio points out that the oratores, men and women who had incurred the lust, as well as being attacked by animals (snakes, serpents, and frogs), would be those who “endured the worst sufferings”. It is therefore interesting to note that the Visio Tnugdali is concerned with educating not only the laity for salvation, but also criticizes the religious themselves, who could deviate from the proper path, incurring the sin of fornication associated with gluttony, and that in the report are harshly punished with worms that ‘eat’ their sexual organs, and these sinners suffer from the action of purifying fire.

Table 1 points to the fact that in Hell souls are devoured by Lucifer, who inhales them and then spits them to various places in the underworld (Pontfarcy, 2010b). Souls were cooked in the horrible pit of Hell, from which a terribly fetid flame welled up into the sky (Pontfarcy, 2010b). Lucifer himself also “bakes” on a grill in Hell, which is stoked by demons (Pontfarcy, 2010b).

Devouring is the action performed by monsters and demons on humans. On the other hand, nourishing is the possibility of humans to nurture themselves in the spaces of the Beyond. After passing through the infernal spaces, Tundal and the angel go to an intermediate place, a kind of Pre-Paradise or Limbo, where souls are no longer devoured.

Regarding the spaces of the Antechamber of Paradise, according to Table 1, the not too bad are those who, according to the narrative, “[...] did not share the goods with the poor as they should and could” (Esteves Pereira, 1895, p. 112). For Emerson, sins are mainly related to touch and taste. In infernal spaces, souls are eaten by monsters. Then they move on to the first phase of the middle stage, a place that the text classifies as ‘not too bad’, where the inhabitants are not tortured or devoured, but suffer wind and rain, as well as hunger and thirst, these latter linked to nutrition. In this sense, the deprivation of water and food by the people who inhabit this place indicates the continuation of the purgation process.

There is a second intermediate space before Paradise. According to the Portuguese version of the narrative: “[...] there dwell the not very good ones who are freed and taken from the pen of Hell and do not yet deserve to be taken to the company of the saints” (Esteves Pereira, 1895, p. 112). Hence the confirmation that it is still an intermediate space, where the inhabitants do not suffer the infernal tortures, but neither are they in the company of the saints nor of God. There are two Irish kings who were once enemies and reconciled, Concobre46 and Donato, the latter, before dying, gave his goods to the poor (Pontfarcy, 2010b). We can now see the presence of these kings and their connection with a positive space, with the presence of trees.

As we can see in Figure 4, Tundal and the angel approach the two kings, who are dressed in white garments and crowns on their heads, as shown, which would bring them closer to Paradise. The picture shows a small piece of text written in red: ‘here speaks of two kings’. Moreover, for those who observe the image, it seems to be about that space of happiness, Paradise. The landscape presents edenic aspects through the brightness, the color and the presence of grass and trees.

When entering this space, according to the text, Tundal and the angel pass through a door and find a very green and alluring field, with beautiful trees, with a soft perfume and planted with many flowers, which gave a good odor (Pontfarcy, 2010b). This element fits the description of the word ‘Paradise’, which comes from the Persian and means ‘fenced garden’ (Delumeau, 1994), place of the blessed righteous, which must be situated in the heavenly world (Bauer, 1988). One of the characteristics of this place, according to the Bible, is that of fullness, with human beings enjoying total happiness and access to the divine presence, elements that do not yet occur in this intermediate space, which, according to Table 1, can be identified with a antechamber of Paradise or even a kind of Limbo, as some of its inhabitants still suffer, according to the report.

In the Duchess of York’s manuscript there is a second representation of the place of the ‘not very good’ where we can view a fountain (Figure 5).

In Figure 5, Tundal and the angel are separated from a beautiful space by a portal. Inside are several people dressed in white, close to the water of life, a very important element quoted in the Bible, and which is related to soul nourishment. This source is mentioned in Genesis: “[...] a river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and there it divided and became four rivers” (Gen 2: 10) (Bible, 1995). The water of life represents abundance and is associated with the four rivers of Earthly Paradise, the Gihon, Pishon, Tiger, and Euphrates (Gen 2: 11-14) (Bible 1995).

These four rivers in the Bible start from the center, that is, from the foot of the tree of life, also described in Genesis (Bible, 1995), separated by the four directions marked by the cardinal points (Cirlot, 1984). Thus, they depart from the center and from the same direction. “The source is the fons juventius, whose waters may be associated with the drink of immortality” [...] (Cirlot, 1984, p. 261, emphasis in the original). In the Bible, Jesus says: “[…] but whoever drinks of the water that I will give him will never be thirsty again. The water that I will give him will become in him a spring of water welling up to eternal life” (Jn 4:14). In the medieval account of a land of abundance, the country of Cocanha, whoever drank from the fountain would always be thirty-two years old (Franco Jr, 1998)47, which meets the notion of eternity in the biblical account.

In the work The visions of the knight Tondal it is mentioned that in this very space where there is the fountain, place of the not very good ones, King Donato, one of the kings we saw in white and crowned garments in Figure 4, suffers in this place daily. He is tortured by fire on his stomach each day for three hours for his sins, such as killing a man in front of St. Patrick’s tomb, and committing adultery (Pontfarcy, 2010b). In the other twenty-one hours he lives in joy and has servants. The illuminations of Margaret of York’s version do not portray the suffering of this king48, but in the printed versions that circulated in Germany in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries there is an image of a crowned king being burned. This is the case of the Speyer edition. (De raptu animae Tundali et eius visione, 1483).

It is possible to realize then that, although the space of Pre-Paradise or Limbo presents some positive characteristics that we observe in the text and the images, as the Edenic environment, with the presence of the green and the abundant vegetation, and also having a biblical element, the source of living water, which characterizes Paradise and the nourishment of the soul, the space is still a place of purgation.

Therefore there is a contradiction in this locality since Marcus’s early version of the Latin manuscript, and even more so in Simon Marmion’s fifteenth-century images, which omits the punishing aspects of the place of the ‘not very good’. On one hand, this place is still tormented, and on the other, it guarantees the presence of Paradise through the source of living water mentioned in the biblical Genesis. The artist, possibly so that readers would not confuse Pre-Paradise with Purgatory, omits from the images the suffering of King Donato, and the images seem to indicate the intermediate space already as Paradise.

Finally, the angel and Tundal reach Paradise and find themselves within a wall. On the first wall they find, the Silver Wall, are married couples who have not committed adultery (f. 37) (Aubert & Marmion, 1990, p. 56). In the second wall of Paradise, the Golden Wall, intended for those who sacrificed their bodies for the strengthening of the Church, the elect have gold and ivory cells in a tree, identified with the Catholic Church. This tree is also associated with the tree of life, described in both Genesis (Gen 2: 9) and the Book of Revelation (Rev 22: 2). The duchess version does not specifically show the image of this tree. However, according to the Speyer incunabulum (De raptu animae Tundali et eius visione, 1483) of the Visio Tnugdali, the tree of life associated with the Church is depicted in Figure 6.

We see in Figure 6 Tundal and the angel inside the Golden Wall. Two characters are crowned in separate rooms facing each other, a man (represented by the beard) and a woman. Near them and the wall is the tree, which in the text is associated with the Church, and from above, after the leaves, two birds fly, one to either side of the image.

Representing life in perpetual evolution and ascending to heaven, this plant has the symbolism of verticality, fecundity and immortality. It unites the earthly and heavenly worlds, for its root lies within the earth, and the branches and crown point to the sky, uniting microcosm, associated with the human being, and macrocosm, with God (Chevalier & Gheerbrant, 1995). Its verticality is also associated with the notion of the world axis and has analogy in Christianity with the crucifixion of Christ to save humans. According to Cirlot (1984, p. 99): “[...] the tree coincides with the cross of Redemption; and in Christian iconography the cross is often represented as the tree of life. Similarly, the tree of the confessors49 at the Golden Wall is intended for those who sacrificed themselves for the strengthening of the Christian faith.

For Emerson (2000), in Paradise itself, the elect may still see, hear, smell, speak, and sing, but they neither eat nor procreate. Procreation is a negative element of infernal spaces, where the senses are perverted. Souls are devoured and digested in this place. The text emphasizes the importance of music, the soft sounds of bird singing, the musical instruments that play alone in this space, which reinforces the aspects of harmony in Paradise (Emerson, 2000; Delumeau, 2003). Marmion produced in the Visions of the knight Tundal an illumination which shows a musical instrument, an organ, played by an angel, who is observed by other celestial beings inside a tent at the Golden Wall (f. 39v) (Aubert & Marmion, 1990, p. 58). Such representation reinforces the musicality and perfection that exist in the Celestial Kingdom50.

The presence of the source of living water in the antechamber of Paradise and the tree of life in the Golden Wall seems to indicate that they are there to satiate the elect in physical or spiritual form, since in Paradise they will lack nothing and may contemplate God directly. In the ultimate space of Paradise, the Wall of Precious Stones, destined for the nine orders of angels, the virgins and the saints, such as St. Patrick (who converted Ireland to Christianity), we realize that the elect have the possibility to contemplate God, which is forbidden to the knight. This space, however, does not mention any aspect related to nutrition, either in the text or in the images of the Visio, probably because there the elect are fed with the divine presence. Recalling the words of Jesus contained in the Gospel according to St.John (6, 48-51), which begin this article: “I am the bread of life [...]/whoever eats this bread will live forever.” Or even in the Book of Revelation about the elect of the Celestial Kingdom: these “[...] never again will they hunger; never again will they thirst [...]” (Ap 7:16).

Concluding remarks

As noted in this article, diet in the Middle Ages could be related to the salvation and damnation of souls, as these souls could feel bodily. Medieval food was often associated with sin, hence the fact that the religious sought to adopt in the monasteries a more “frugal” diet and there were examples of feminine mystics who performed almost absolute fasting, seeking the purification and imitation of Christ.

Specifically in the Visio Tnugdali, the sin of gluttony is often also associated with that of lust, hence there is a punishment for ‘gluttons and fornicators’, who could be religious, showing that the sin of the flesh was likely to happen to anyone and therefore there was a need for the believer’s own vigilance over his actions, with the help of the Church, that he might obtain the salvation of the soul.

In the infernal spaces, in general, souls are devoured by monsters and cannot feed, or consume only disgusting things, such as sulfur. The Visio Tngudali places sinners suffering in kitchen-like spaces, by the presence of fire and the fact that bodies are turned into food, both through the swallowing of monsters and the Devil, and the fact that their bodies are prepared as food, through torture, being baked, fried in a frying pan, sliced, skewered, mashed into a pulp, quartered, among other actions.

In the antechamber of the Celestial Kingdom, we perceive edenic elements in the Visio that give satiety and plenitude, such as the source of the water of life associated with the four rivers of Earthly Paradise. Finally, in Heavenly Paradise proper is the presence of the tree of life, described in Genesis and Book of Revelation, which has an invigorating and comforting aspect. At the Wall of Precious Stones, the best part of Paradise, the elect are fed and invigorated with the divine presence, being in complete plenitude.

The presence of dietary aspects in an account of travel to the Beyond made it closer to the daily lives of medieval men and women. Hell’s spaces have characteristics of the kitchen space, such as fire and cooking and cutting tools, utensils such as knives, frying pans, ovens, with which souls who did not repent of their sins in life and who had not made their own due penances are punished.

The Paradise elements, linked to the tree of life and the source of living water, described in the Bible (1995), contribute to bring more joy and satisfaction to the elect, which are crowned with the presence of God in this place. Therefore, the eating and devouring aspects of the Visio Tnugdali help the medieval people better understand the spaces of the afterlife, helping them seek the nourishment of their souls to reach Paradise in the afterlife..

REFERENCES

Adamson, M. W. (2004). Food in middle ages. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Aubert, D., Marmion, S. (1990). The visions of Tondal text and miniatures. In T. Kren, & R. Wieck (Eds.), The Visions of Tondal from the library of Margaret de York (p. 37-59) Los Angeles, CA: Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Baschet, J. (1985). La conception de l’enfer en France au XIVe siècle: imaginaire et pouvoir. Annales. Économies. Sociétés, Civilisations, 40(1), 185-207. [ Links ]

Baschet, J. (2014). Les justices de l’au-dela. les representations de l’enfer en France et Italie (XII et Xve siècle). Rome, IT: École Française de Rome. [ Links ]

Bauer, J. (1988). Dicionário de teologia bíblica. São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Bíblia de Jerusalém. (1995). São Paulo, SP: Paulus. [ Links ]

Blockmans, W. (1992). The devotion of a lonely duchess. In T. Kren (Ed.), Margaret of York, Simon Marmion and the visions of Tondal (p. 29-46). Malibu, CA: The Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Busby, K. (2012). Text and image in the ‘Getty Tundale’. In M. Wright, N. Lacy, & R. Pickens (Eds.), ‘Moult a sans et vallour’: Studies in medieval french literature in honor of William W. Kibler. Amsterdam, NL: Rodopi. [ Links ]

Bynum, C. W. (1985). Fast, feast, and flesh: the religious significance of food to medieval women. Representations, 1(11), 1-25. [ Links ]

Carozzi, C. (1994). Le voyage de l’âme dans l’au-dela d’apres la litterature latine (V-XIIIéme siecle). Paris, FR: École Française de Rome. [ Links ]

Cavagna, M. (2008). Introduction. In Aubert, D., La vision de Tondale (p. 121-160). Paris, FR: Honoré Champion. [ Links ]

Chevalier, J., & Gheerbrant, A. (1995). Dicionário de símbolos. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: José Olympio. [ Links ]

Cirlot, J-E. (1984). Dicionário de símbolos. Barcelona, ES: Moraes. [ Links ]

De raptu animae Tundali et eius visione. (1483). (Veröffentlichungsangabe: Johan Speyer e Konrad Hist). München, DE: [s/l]. [ Links ]

Delumeau, J. (2003). O que sobrou do paraíso? São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Dias, P. B. (2015). A grande refeição: metáforas alimentares na descrição do religioso transcendente na cultura ocidental. In C. Ribeiro, & C. Soares (Coords.), Odisseia de sabores da lusofonia (p. 21-40). Coimbra, PT: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. [ Links ]

Dinzelbacher, P. (1986). The way to the other world in medieval literature and art. Folklore, 97(1), 70-87. Recuperado em 20 maio de 2019 de Recuperado em 20 maio de 2019 de http://www.jstor.org/stable/1260523 [ Links ]

Dinzelbacher, P. (1992). The latin Visio Tnugdali and its french translations. In T. Kren (Ed.), Margaret of York, Simon Marmion and the visions of Tondal (p. 111-118). Malibu, CA: The Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Elias, N. (1994). O processo civilizador (Vol. 1, 2a, ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Jorge Zahar. [ Links ]

Emerson, J. S. (2000). Harmony, hierarchy and senses in the Vision of Tundal. In J. S. Emerson, & H. Feiss (Eds.), Imagining heaven in middle ages (p. 3-46). New York, NY: Garland. [ Links ]

Esteves Pereira, F. M. (Ed.) (1895). Visão de Túndalo. Revista Lusitana, 3(1), 97-120. [ Links ]

Fra Angelico. (1432-1435). O Juízo Final. Recuperado em 20 de setembro de 2019 em Recuperado em 20 de setembro de 2019 em http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/a/angelico/index.html [ Links ]

Franco JR., H. (1998). Cocanha. A história de um país imaginário. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Guerreau, A. (2002). Caça. In J. Le Goff, J-C. Schmitt (Coords.), Dicionário temático do ocidente medieval (Vol. 1, p. 139-151). São Paulo, SP: EDUSC/Imprensa Oficial do Estado. [ Links ]

Toledo. (1526). História del virtuoso caballero don Túngano. Recuperado em 20 de set 2019 de Recuperado em 20 de set 2019 de https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Historia_del_virtuoso_caballero_don_T%C3%BAngano_Toledo,_1526.jpg [ Links ]

Jeanroy, A., & Vignaux, A. (1903). Vision de Tindal. In A. Jeanroy, & A. Vignaux, Voyage de Raimon Perellos au purgatoire de Saint Patrice: visions de Tindal et de Saint Paul (p. 57-119, Textes languedocienes du XV siècle). Tolouse, FR: E. Privat. [ Links ]

La Vision de Tondale. (2008). (Les versions françaises de Jean de Vignay, David Aubert, Regnaud de Queux. Editées par Matia Cavagna). Paris, FR: Honoré Champion. [ Links ]

La Visión de Túngano. (2012). Recuperado em 27 de setembro de 2019 de Recuperado em 27 de setembro de 2019 de http://archive.is/20121230013227/slt.telam.com.ar/la-vision-de-tungano/c13 [ Links ]

Lawers, M. (1994). Santas e anoréxicas: o misticismo em questão. In J. Berlioz (Org.), Monges e religiosos na idade média (p. 219-223). Lisboa, PT: Terramar. [ Links ]

Le Goff, J. (1993). O Nascimento do purgatório. Lisboa, PT: Editorial. Estampa. [ Links ]

Le Goff, J. (1994). O imaginário medieval. Lisboa, PT: Editorial Estampa. [ Links ]

Le Goff, J., & Truong, N. (2006). Uma história do corpo na idade média. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira [ Links ]

Marmion, S. (1990a). The visions of the knight Tondal, 1475, f. 7. In T. Kren, & R. Wieck (Eds.), The visions of Tondal from the library of Margaret de York (p. 39 ). Los Angeles, CA: Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Marmion, S. (1990b). Os reis Concobre e Donato, 1475, f. 35. In T. Kren, & R. Wieck (Eds.), The visions of Tondal from the library of Margaret de York (p. 55). Los Angeles, CA: Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Marmion, S. (1990c). Os não muito bons. Visions of the Knight Tondal, 1475, f. 34v. In T. Kren, & R. Wieck (Eds.), The visions of Tondal from the library of Margaret de York (p. 54). Los Angeles, CA: Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Montanari, M. (2002). Alimentação. In J. Le Goff (Org.), Dicionário temático do ocidente medieval (Vol. 1, p. 35-55). São Paulo, SP: Edusc/Imprensa Oficial do Estado. [ Links ]

Montanari, M. (2008). Comida como cultura. São Paulo, SP: Senac. [ Links ]

Montanari, M. (2016). Histórias da mesa. São Paulo, SP: Estação Liberdade. [ Links ]

Nogueira, P. (2015). O imaginário do além-mundo na apocalíptica e na literatura visionária medieval. São Bernardo do Campo, SP: Umesp. [ Links ]

Palmer, N. (1982). ‘Visio Tnugdali’. The german and dutch translations and their circulation in the later middle ages. Munich, DE: Artemis Verlag. [ Links ]

Palmer, N. (1992). Illustrated printed editions of the Visions of Tondal from the late fifteenth centuries and early sixteenth centuries. In T. Kren (Ed.), Margaret of York, Simon Marmion and the visions of Tondal (p. 157-170). Malibu, CA: The Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Pontfarcy, Y. (2010a). Introduction. In Y. Pontfarcy, L’au dela au moyen age. ‘Les visions du Chevalier Tondal’ de David Aubert et sa source la ‘Visio Tundali’, de Marcus (p. XI-XLVII). Berne, CH: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Pontfarcy, Y. (2010b). Les visions du Chevalier Tondal. In Y. de Pontfarcy (Ed.), L’au dela au moyen age. Les visions du Chevalier Tondal de David Aubert et sa source la ‘Visio Tundali’, de Marcus (p. 2-205). Berne, CH: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Pontfarcy, Y. (2013). Justice humaine et justice divine dans la ‘Visio Tnugdali’ et le ‘Tractatus de purgatorio Sancti Patricii’. Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes, 1(26), 199-210. DOI :10.4000/crm.13406 [ Links ]

Schmitt, J.-C. (2016). Les rythmes au moyen âge. Paris, FR: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Schmitt, J-C. (2002a) Corpo e alma. In J. Le Goff, & J-C. Schmitt (Coords.), Dicionário temático do ocidente medieval (Vol. 1, p. 253-269). São Paulo, SP: Imprensa Oficial/EDUSC. [ Links ]

Schmitt, J-C. (2002b). Imagem. In J. Le Goff, & J-C. Schmitt (Coords.), Dicionário temático do ocidente medieval (Vol. 1, p. 591-605). São Paulo, SP: Imprensa Oficial/EDUSC. [ Links ]

Schmitt, J-C. (2005). O corpo e o gesto na civilização medieval. In A. I. Buescu, J. S. Sousa, & M. A. Miranda (Coords.), O corpo e o gesto na civilização medieval (p. 15-36). Lisboa, PT: Colibri. [ Links ]

Schmitt, J-C. (2007). O corpo das imagens. São Paulo, SP: Edusc. [ Links ]

Seymour, St. J. D. (1926). Studies in the Vision of Tundal. In Proceedings of the 4ª Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature (Vol. 37, p. 87-106), Dublin, IR. [ Links ]

Soares, M. V. (2008). Santidade, Jejum e anorexia na história. História em Reflexão, 2(3), 1-11. [ Links ]

Vicente, G. (1987). Auto da alma. Porto, PT: Porto Editora. [ Links ]

Vignay, J. (2008). La vision de Tondale. Mirroir historial (MH). In M. Cavagna (Ed.), La vision de Tondale (p. 65-119, Les versions françaises de Jean de Vignay, David Aubert, Regnaud de Queux). Paris, FR: Honoré Champion. [ Links ]

Wagner, A. (1882). Visio Tnugdali. Lateinische und altdeutsch. Erlangen, DE: A. Deichert, 1882. [ Links ]

Wieck, R. (1990). The Visions of Tondal and the visionary tradition in the middle ages. In T. Kren, & R. Wieck (Eds.), The visions of Tondal from the library of Margaret de York (p. 3-7). Malibu, LA: Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Wieck, R. (1992). Margaret of York’s Visions of Tondal relationship of the miniatures to a text transformed by translator and iluminator. In T. Kren (Ed.), Margaret of York, Simon Marmion and the Visions of Tondal (p. 119-128). Malibu, CA: The Paul Getty Museum. [ Links ]

Zierer, A. (2017). Visio Tnugdali e sua Circulação nas Idades Média e Moderna (S. XII-XVI). Notandum, 1( 43), 37-54. DOI: 10.4025/notandum.43.3 [ Links ]

Received: May 31, 2019; Accepted: October 01, 2019

text in

text in