Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Acta Scientiarum. Education

versión impresa ISSN 2178-5198versión On-line ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.43 Maringá 2021 Epub 01-Sep-2021

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v43i1.48270

HISTÓRY AND PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION

Pedagogical efficiency and the Brazilian development project: fundamentals of ‘neo-teaching’ in secondary education

1Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul, ERS-135, Km 72, 200, Cx. Postal 764, 99700-970, Erechim, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.

This article discusses the relation between the developmental project, designed for the country in the 1950s and 1960s, and the high school, based on the ideology of modernization oriented to social and economic progress, which emphasizes teaching as an element able of making possible the intended changes, according to the precepts of the theory of Human Capital. For this, the methodology used involved documental analysis, according to the assumptions of Cellard (2008), having as methodological-interpretative principles Popkewitz’s (1997) theorizations, involving ‘social epistemology’. Based on these notes, three printed materials intended for secondary school teachers were analyzed: the Escola Secundária Magazine, published between 1958 and 1963, and the books Manual do Professor Secundário, by Theobaldo Miranda Santos, published in 1961 and Escola Secundária Moderna, by Lauro de Oliveira Lima, published in 1962. The research results indicate the emergence of new rationales for teaching secondary education in Brazil, which we call ‘neo-teaching’, based on the imperatives of economic development, following the corporate molds of performativity, competitiveness, and permanent innovation. Such configurations, derived from the neoliberal economicist perspective, position the teacher as a facilitator of learning, based on the ideal of modernization and renewal of teaching, oriented towards pedagogical efficiency.

Keywords: high school; teaching; modernization; efficiency

Este artigo problematiza a relação entre o projeto desenvolvimentista brasileiro, dimensionado para o país nas décadas de 1950 e 1960, e o ensino secundário, a partir do ideário de modernização orientado para o progresso social e econômico, com ênfase na escola e na docência como elementos capazes de viabilizar as mudanças pretendidas, conforme os preceitos da teoria do Capital Humano. Para isto, a metodologia utilizada envolveu a análise documental, de acordo com os pressupostos de Cellard (2008), tendo como princípios metodológico-interpretativos as teorizações de Popkewitz (1997), envolvendo a ‘epistemologia social’. Com base nestes apontamentos, foram analisados três materiais impressos destinados aos docentes do ensino secundário: revista ‘Escola Secundária’, publicada entre 1958 e 1963, e os livros ‘Manual do professor Secundário’, de Theobaldo Miranda Santos, publicado em 1961 e ‘Escola Secundária Moderna’, de Lauro de Oliveira Lima, publicado em 1962. Os resultados da pesquisa indicam a emergência de novas racionalidades para a docência do ensino secundário no Brasil, denominadas de ‘neodocência’, pautadas pelos imperativos de desenvolvimento econômico, seguindo os moldes empresariais de performatividade, competitividade e inovação permanente. Tais configurações, derivadas da perspectiva economicista neoliberal, posicionam o professor como facilitador da aprendizagem, com base no ideal de modernização e renovação do ensino, orientado para a eficiência pedagógica.

Palavras-chave: ensino secundário; docência; modernização; eficiência

Este artículo problematiza la relación entre el proyecto de desarrollo brasileño, diseñado para el país en las décadas de 1950 y 1960, y la educación secundaria, basada en la ideología de la modernización orientada al progreso social y económico, con énfasis en la escuela y la enseñanza como elementos capaces de posibilitar los cambios previstos, de acuerdo con los preceptos de la teoría del Capital Humano. La metodología empleada implicó el análisis de documentos, según Cellard (2008), teniendo como principios metodológico-interpretativos las teorizaciones de Popkewitz (1997), sobre la 'epistemología social'. A partir de estas notas, se analizaron tres materiales impresos destinados a profesores de secundaria: la revista 'Escola Secundária', publicada entre 1958 y 1963, y los libros 'Manual del profesor Secundário', de Theobaldo Miranda Santos, publicado en 1961 y 'Escola Secundária Moderna ', de Lauro de Oliveira Lima, publicado en 1962. Los resultados de la investigación indican el surgimiento de nuevos fundamentos para la enseñanza de la educación secundaria en Brasil, que llamamos' neo-enseñanza ', guiados por los imperativos del desarrollo económico, siguiendo los modelos de desempeño, competitividad e innovación permanente. Configuraciones, derivadas de la perspectiva economista neoliberal, que posicionan al docente como un facilitador del aprendizaje, basado en el ideal de modernización y renovación de la enseñanza, orientado a la eficiencia pedagógica.

Palabras-clave: enseñanza secundaria; docencia; modernización; eficiencia

Introduction

This article presents the investigative results regarding the relationship between the developmental project, designed for the country in the 1950s and 1960s, and the production of certain specificities for teaching in secondary education, made visible in pedagogical forms, to contribute to the realization of intended social and economic changes. In this sense, it is important to mention that such analytic is positioned in the direction of producing new perspectives for the understanding of teaching in contemporaneity, given the project of society configured by neoliberalism, considering what Dardot and Laval (2016, p. 402) present when claiming that “[...] it is up to us to allow a new sense of the possible to open the way”.

The outlined investigative path involved document analysis, according to Cellard’s (2008) assumptions, having Popkewitz’s (1997) theorizations as methodological-interpretative principles, involving ‘social epistemology’ through a non-linear historical perception, which considers the wide range of relationships of the research object with the context in which it was produced. For this, it is important to position the different conceptions of teaching produced from the second half of the 20th century, according to the main characteristics of our time, marked by the emphasis on individual efficiency, where the broad transformations of a social, economic, and cultural order accentuate the processes of social exclusion and, at the same time, revitalize competitiveness and investment in human capital (Krawczyk, 2011; Dardot & Laval, 2016).

Contemporary schooling processes configured at the heart of a knowledge society, a mark of contemporary capitalism, are based on the rationality of maximizing the learning required by a market economy, guided by flexibility and marked by insecurity, in which “[…] knowledge economies are stimulated and driven by creativity and inventiveness” (Hargreaves, 2004, p. 17). A context that marks the emergence of new rationalities from which school and teaching are positioned as essential elements for the formation of certain characteristics in subjects, which correspond to market needs, from which efficiency becomes a central concept.

In these terms, it is important to elucidate how economic rationalities were consolidated in the educational field, configuring pedagogical efficiency as an important presupposition concerning the production of ‘neo-teaching’, from the second half of the 20th century, in the direction that it conquers higher levels of economic development, following the developmental project envisaged for the country.

The text is divided into three sections. The first presents some specificities of the context in which the country’s developmental project was created, from the 1950s onwards. The second deepens the relationship between education and development and, finally, the third analyzes the assumptions of teaching in this scenario, signaling the production of a ‘neo-teaching’, considering the pedagogical forms intended for secondary school teachers in their approximations between economics and education.

Modernization and education: developmental principles

The Brazilian developmental project set up in the 1950s involved the “[…] conviction that accelerated industrialization would be the only solution for the country’s economic and social progress” (Ianni, 1989, p. 187). Based on this assumption, the developmental policy was consolidated and influenced the most diverse segments of society, including schooling (Vieira, 1983; Chaves, 2006). Thus, the 1950s and early 1960s characterized

A troubled historical moment, in which the ideals of progress and modernization gained new breath, and the discourses of the time advocated - in addition to issues related to industrialization, as well as the infrastructure that this would require, such as transport, energy, labor, and others - issues related to education, with a special focus on the expansion and democratization of access to the public education system (Silva & Souza, 2009, p. 788).

The social policy aimed at economic development, adopted by the country, legitimated by a populist democracy16, became more evident especially in the government of Juscelino Kubitschek, against the backdrop of the influence of the United States, in terms of the affirmation of capitalism and the diffusion of the values of liberal democracy (Vieira, 1983; Hidalgo & Mikolaiczyk, 2015). In these terms, the developmental character, marked by the ideals of modernization, assumed better-defined characteristics through the Targets Program, implemented after the election of Juscelino Kubitschek, in 1956. This program was characterized by “[…] large investments in sectors of energy, transport, food, basic industries and incentives to the automobile industry […]”, through which economic development would be achieved, allowing for “[…] fifty years [of progress] in five” (Waschinewski & Rabelo, 2017, p. 536).

In relation to that program, Target 30, which addresses the training of technical personnel, reaffirms the objective of “[…] providing the country with an industrial infrastructure and superstructure and modifying its economic situation […]” (Brazil, 1958, p. 95), defining that “[…] the economic infrastructure must be accompanied by an educational and, therefore, social infrastructure […]” (Brasil, 1958, p. 95), configuring the assumptions that guided an education project for development, which envisaged

[...] the physical equipping of schools and the technical-pedagogical improvement of the human factor, especially in industrial and agricultural education. Construction of new schools and their equipment, expansion of existing schools […] Concession, for secondary education, of 56,068 scholarships for students of the Junior High School; 9,106 to students of the Collegiate Course; 36,534 to the Commercial; 13,498 to Industrial; 14,492 to Normal and 11,308 to Agricultural Courses. Total medium degree scholarships: 141,006 (Brasil, 1958, p. 96).

In these terms, the pedagogical forms analyzed also seem to reflect the link between development and education, through the large investment in secondary education, by showing that,

One of the most characteristic facts of the moment we are living in is the new awareness, which Brazilian society is acquiring, of the ‘role that education must play in national life, supporting economic development, enabling technological progress and ensuring the basic conditions of democratic life’ (Escola Secundária nº 16, March 1961, p. 3, emphasis added).

Analytics in which it is also important to mention that the national developmental influence, according to what is presented in the research by Ide and Rotta Júnior (2013, p. 135), founded a project of “[…] development based on the Theory of Human Capital, as a principle for the actions of the State and the market […]”, in which education assumes centrality, as a determining factor for the country's economic and social development.

The ‘time we are living in is characterized by its absorbing concern with economic development’ […] in the dynamization of this living framework, ‘education in general and, in a special way, secondary education is called to play an essential’ and decisive role for the destinies of our country. […] It will, however, depend on the vision, inventiveness, and capacity of the educators (Escola Secundária nº 14, September 1960, p. 3-4, emphasis added).

In this sense, from an economic perspective, human capital was configured as a “[…] stock of economically valuable knowledge incorporated into individuals” (Laval, 2004, p. 25). Its theories were widely disseminated, especially from the beginnings of the Chicago School, in the 1960s, with Theodore Schultz as one of its main representatives. He defended a “[…] proposition according to which people value their abilities, both as producers and as consumers, through self-investment, and that education is the greatest investment in human capital” (Schultz, 1987, p. 13).

Brazilian society, ‘with the spectacular upswing of the progress we are currently experiencing, under the sign of an accelerated and almost tumultuous economic development’, is developing an acute sensitivity to the ‘values that education can and should represent in our future social plan’. Both under the prism of our economic and technological development and under the prism of our progressive integration into the ideals and molds of democratic life, education is and will increasingly be the great catalyst for our possibilities as a free and prosperous people, aware of their destinies (Escola Secundária nº 9, June 1959, p. 3, emphasis added).

During this period, the Higher Institute of Brazilian Studies (Iseb) was responsible, according to the theories of Hidalgo and Mikolaiczyk (2015, p. 104), for “[…] ideologically guiding Brazilian developmental policies […]”, from the “[…] economic thinking of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) […]” and other international organizations, which also influenced the educational actions developed by the Ministry of Education, in the direction of “[…] principles of efficiency and merit” (Chaves, 2006, p. 716). Thus, it is important to note that

[...] these values co-substantiated the fundamental principles of liberal political discourses and guided the organization of social institutions in countries aligned with the USA in the 1950s, as well as the political-pedagogical proposals for education systems, expressed in Brazil, above all, by the Escola Nova [New School] movement. (Hidalgo & Mikolaiczyk, 2015, p. 102).

In addition to the New School influence, it is also important to mention that the developmental perspective was also permeated by the assumptions of the Human Capital theory, by linking education with social and economic development. Thus, it is important to point out, as presented by Hidalgo and Mikolaiczyk (2015, p. 101), that the period between the 1950s and 1960s, in educational terms, “[…] corresponded to a significant impulse towards the modernization of the country’s education systems […]”, especially through investments in the “[…] elaboration of instructional material and teacher training projects”. In this sense, based on the context presented, the next section introduces perspectives in relation to teaching, expressed both in the pages of the Escola Secundária magazine and in two important works aimed at secondary school teachers - Manual do Professor Secundário, by Theobaldo Miranda Santos, published in 1961; and Escola Secundária Moderna, by Lauro de Oliveira Lima, published in 1962.

Secondary education and teaching: fabrications of a modernization project

Based on the country’s social, political, and economic configurations in the 1950s and 1960s, presented in the previous section, the year 1953 is marked, in the educational field, by the creation of the National Campaign for the Dissemination and Improvement of Secondary Education - Cades, by the Board of Directors of Secondary Education linked to the Ministry of Education, in a movement that aimed to train teachers to act at this stage of schooling, emphasizing the New School principles in favor of a modernization of education (Fonseca, 2006; Rosa & Dallabrida, 2016). This movement boosted the publication of several books, didactic manuals, and periodicals about secondary education, in order to disseminate modern teaching concepts, such as the works Manual do Professor Secundário, by Theobaldo Miranda Santos, published in 1961; Escola Secundária Moderna, by Lauro de Oliveira Lima, published in 1962; and from the Escola Secundária17 magazine, published between 1957 and 1963, which aimed to offer, in the words of Rosa and Dallabrida (2016, p. 261), a “[…] more adequate training of the modern secondary school teacher and, for this, had the organization of its editions aimed at the area of didactics”.

These authors argue that the Escola Secundária magazine aimed to “[…] form a new teaching mentality […]” through the “[…] pedagogical renewal of secondary education” (Rosa and Dallabrida, 2016, p. 262). This perspective is evidenced in the editorial of the first issue of the publication, written by professor Gildásio Amado who, at the time, was in charge of the Secondary Education Board, when presenting that

ESCOLA SECUNDÁRIA is intended to provide information, clarification, suggestions, and technical assistance to these 40,000 secondary teachers who, spread across all parts of our territory, work in the arduous seeding of education and national culture. It also aims to serve as a vehicle for exchange between Brazilian professors, in the exchange of ideas, suggestions, and experiences, favoring the ‘formation of a new, more progressive mentality, more conducive to objective observation, renovating experimentation’ and critical review of postulates, purposes, curricula, and methods on which the entire educational activity of our magisterium is based (Escola Secundária nº 1, June 1957, p. 8, emphasis added).

The assimilation of business rules by teaching makes it understood as “[…] a factor whose production conditions must be fully submitted to economic logic” (Laval, 2004, p. 20). The production of ‘neo-teaching’, guided by the principle of efficiency, in terms of the search for excellence in results, is based on permanent innovation and the ability to adapt to constant changes.

The performance of the Board of Secondary Education of MEC, by itself and by CADES, is becoming a powerful ferment to activate, update, and improve our secondary education, better preparing and guiding its teachers, stimulating their improvement by creating and disseminating literature useful and accessible didactics, providing assistance and guidance to schools, ‘promoting, at last, the formation of a new mentality’ through symposia, seminars, study weeks, vacation courses, annual competitions for didactic works, magazines, leaflets, and publications (Escola Secundária nº 6, September 1958, p. 4, emphasis added).

It is also important to emphasize that the ideals of modernization of teaching and schooling were based on the modernization of society, aiming to adapt the subjects to the new reality configured by developmental principles where, considering the New School assumptions and the financial assistance of Unesco, throughout from the 1950s and 1960s, indications of changes in secondary education are incorporated to transform it into, in the words of Nunes (2000, p. 35), a “[…] more modern, practical, dynamic and appropriate to economic requirements of the moment […]”, where some of these directives, such as autonomy and diversification, have also been expressed in the Law of Guidelines and Bases of Education of 1961 (Nunes, 2000).

New pedagogical ideas, ‘social and economic transformations in the modern world, and the development of science applied to education changed the structure and functions of secondary schools. The progress of democracy’ has destroyed class or race privileges in education, making secondary school, at least theoretically, accessible to all members of the community (Manual do Professor Secundário, 1961, p. 41, emphasis added).

From such recurrences evidenced in the research material, it is important to point out that the New School movement18, in Brazil, considers “[…] new education as a movement of ideas, influenced by North American and European thinkers, whose defining feature was the fact of opposing pedagogical practices and the traditionalist educational spirit” (Cunha, 1996, p. 6).

From this conception emerges a methodological perspective centered on the form of pragmatism19, proposed by John Dewey who, in the words of Chaves (2006, p. 706), “[…] contributed to the production of a type of educational thought in Brazil, in the 1950s, consistent with the new economic and social demands of the at the time, driven by a developmental policy”.

Considering that the industrialization process and the assumptions of American liberal democracy formed the foundations of Dewey’s thought, school and education served as primary instruments in the preparation of the subject, according to the new configurations of society (Schmidt, 2009). Based on Dewey’s theories, it is also important to highlight the influence of William Kilpatrick’s considerations, especially through the repercussion, in the Brazilian educational field, of the work ‘Education for a Changing Civilization’, prepared in 1926, having as its axis the democratic society and scientific advances, positioned education as a fundamental element to adapt individuals to the constant process of social development, to ensure the “[…] progress of population and production” (Kilpatrick, 1964, p. 13). Thus, the next section deepens the contours that teaching in secondary education assumed from the project of modernization of Brazilian schooling.

Pedagogical efficiency and the modernization of teaching

Anísio Teixeira can be considered one of the main representatives of Deweyan pragmatism in Brazil, positioning education not only as “[…] a process of training and improvement of man, but an economic process of developing the human capital of society” (Teixeira, 1957, p. 28). This perspective, according to Biesta’s theories (2016), marks the constitution of an educational process where schooling is reduced to the formation of skills and transmission of moral and civic values, characteristic of modern democratic societies. In this sense, teaching assumes centrality, where the search for efficiency tends to work as a guarantee of the dimensioning of the ongoing modernization ideals, in which “[…] advanced movements on the path of human progress only become possible when supported by correct and ‘efficient' teaching’” (Escola Secundária No. 4, March 1958, p. 16, emphasis added). In this sense,

It is increasingly evident that economic development, technological progress, and the realization of democratic ideals - this triptych that dramatically polarizes all attention and condenses all the current aspirations of the Brazilian people - will only become feasible if they have the support of an educational system that is solidly structured, healthy, up-to-date and endowed with duly qualified buildings, equipment and teaching staff to 'perform their tasks with the desired degree of efficiency'; without it, the nation will be running in search of mirages (Escola Secundária nº 16, March 1961, p. 3, emphasis added).

The fetish of progress that involves contemporary pedagogical discourses, a product of a specific time and space, was produced with well-defined objectives by the project of modernity that was intended to be put into practice, and strongly linked to the perspective of teaching as an effective way to produce changes desired. Thus, from a historical perspective, “[…] society needed and massively endowed itself with an institution, the school, and a profession, the masters, who were entrusted with this task: modernization, leading the new generations to a new society” (Enguita, 2016, p. 16, our translation)20.

In this context, the school and teaching are driven to meet these assumptions through a new characterization of education, which increasingly “[…] tends to be considered as a commodity” (Charlot, 2007, p. 135). From this perspective, new challenges for the teaching work are evident, considering that, in the words of Sibilia (2012, p. 43), the institutionalization process of schooling would be linked to the need to train “[…] subjects equipped to function efficiently within the historic project of industrial capitalism”.

In valuing instruction, the germ of the current emphasis on technical training to be successful in the labor market seems to reside - a type of ‘teaching’ that is now often ‘named using sports terms such as training or coaching, which imply exercising or drilling’ (Sibilia, 2012, p. 139, emphasis added).

In this regard, Pacheco and Pestana (2014, p. 27) show that the nuances of globalization and neoliberalism, by positioning the “[…] market as a matrix of educational solutions to economic problems […]”, produce new configurations for teaching, linking it to “[…] meritocracy as an engine of educational competitiveness” (Pacheco & Pestana, 2014, p. 27). Thus, in this context, the authors consider that terms such as “[…] quality, effectiveness, efficiency, performance, and competence […]” (Pacheco & Pestana, 2014, p. 25) reveal assumptions of a ‘market rationality’, which represents an important characteristic of ‘neo-teaching’, by understanding “[…] teaching work as a result-oriented activity” (Pacheco & Pestana, 2014, p. 27). Therefore, efficiency can be considered an economic criterion of an instrumental character, “[…] which reveals the administrative capacity to produce maximum results with minimum resources, energy, and time” (Sander, 1995, p. 43). The emphasis on the perspective of pedagogical efficiency is also manifested in the subjectivity of the teacher, as highlighted in the research material.

It is useless to apply scientific education processes without being animated by the teacher’s personality. Enthusiasm and joy at work, naturalness and delicacy in manners, skill and precision in explanations, clarity and vivacity in presentations, language adaptation to the students’ mentality, voice adequacy (in terms of pitch and speed) to the nature of the lessons, discretion, modesty, patience, kindness, energy, serenity, impartiality, and justice, ‘are attitudes that the teacher must assume for greater efficiency in their educational action’ (Manual do Professor Secundário - Santos, 1961, p. 246, emphasis added).

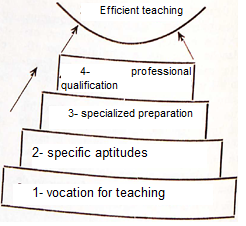

Considering education as a foundation for development, under the influence of the Theory of Human Capital, the links between economy and education are narrowed in the perspective of the existence of a “[…] individual and social rate of return to what is invested in worker training” (Silva & Souza, 2009, p. 788). Such perspective configures the fabrication of a type of teaching based on instrumental and technical rationality, subordinated to the logic of “[…] effectiveness and efficiency” (Afonso, 2003, p. 39). This dimension can be seen in the excerpt below, illustrated by Figure 1.

Four basic conditions must compete in authentic teachers, namely: a) an authentic vocation to the magisterium; b) specific skills for teaching; c) specialized preparation in the subjects they will teach; d) professional qualification in teaching work techniques (Escola Secundária nº 4, March 1958, p. 25).

The emphasis on pedagogical efficiency positions the teacher as an element responsible for promoting the intended changes, developing “[…] the human skills and capabilities that will enable individuals and organizations to survive and succeed in the knowledge society” (Hargreaves, 2004, p. 26).

The ‘economy was placed’, more than ever, ‘at the center of individual and collective life’, the only legitimate ‘social values’ being those of ‘productive efficiency’, individual, mental and affective mobility, and personal success. This cannot leave unscathed the whole of a society’s normative system and its education system (Laval, 2004, p. 15, emphasis added).

Figure 1 Conditions for efficient teaching. Source: Ensino Secundário Magazine nº 4, March 1958, p. 25.

Faced with a reality that positions school, according to Laval's theories (2004, p. 11), as a “[…] quasi-company […]”, in which the teaching performance should be oriented towards maximum performance, requiring from the educator a performance capable of ensuring the best results, ‘neo-teaching’ configures itself linked to a utilitarian knowledge, capable of preparing subjects for life, in order to “[…] contribute to the modernization of society and overall efficiency of the economy” (Laval, 2004, p. 11). Therefore, it is immersed in the logic of the market and in the assumptions of competitiveness, in which pedagogical efficiency is considered a fundamental element.

It is useless to apply scientific education processes without being animated by the teacher’s personality. Enthusiasm and joy at work, naturalness and delicacy in manners, skill and precision in explanations, clarity and vivacity in presentations, language adaptation to the students’ mentality, voice adequacy (in terms of pitch and speed) to the nature of the lessons, discretion, modesty, patience, kindness, energy, serenity, impartiality, and justice, ‘are attitudes that the teacher must assume for greater efficiency in their educational action’ (Manual do Professor Secundário - Santos, 1961, p. 246, emphasis added).

Considering what the excerpts present, the vocational emphasis that founded the teaching practice in the 1950s and 1960s seems to have been marked by the idea of training “[…] super teachers who quotidianly needed to live the overcoming and develop altruistic ways of living, giving themselves fully to the vocation” (Fabris, 2018, p. 212).

In these terms, pedagogical efficiency is inscribed in a “[…] redemptive narrative of the teacher” (Popkewitz, 2015, p. 442), oriented towards human progress, permeating educational reform agendas21 elaborated for the Brazilian high school. A table that denotes important conceptual traits to characterize ‘neo-teaching’, from a practical perspective, focused on the formation of an ideal teacher, evidencing a set of dispositions that refer to the formation of habits and attitudes that “[…] have for objective to order the conduct of the soul” (Popkewitz, 2015, p. 442).

[...] The teacher must act intentionally by setting goals, investing in students, planning deliberately, executing effectively, continually increasing effectiveness, and working relentlessly. ‘The psychological qualities of being determined, effective, and working tirelessly’ go hand in hand with acting accurately in following the teaching material, being balanced, and self-supervised. The qualities are also linked to the attitudes of the teacher’s beliefs, relationships with others, gratitude and optimism, and managing times and attitudes, non-verbal language, and ‘making memorable lessons’ (Popkewitz, 2015, p. 442, our translation, emphasis added)22.

Considering these arguments, Fabris and Dal'Igna (2013) show that the present has as brand the development of an entrepreneurial culture, configuring a rationality based on neoliberal principles, characterized by the intensification of investments in the production of innovative teaching, pushing the teacher to become an entrepreneur of him- or herself. Characterization whose contours can be seen in the following excerpt, when defining that

The ‘efficiency of the teacher depends on the whole, on the total of possibilities and gifts’ that make up his or her personality, on a global structure and not on isolated factors. Intelligence and general, special, pedagogical culture, feelings, action, convictions, ideas, appearances, realities come together (Escola Secundária nº 12, March 1960, p. 22, emphasis added).

Rationality permeated by the business dimension that marks “[...] the subject of contemporary society who needs to be prepared for the high performances imposed on him or her as goals to be achieved more quickly, in an increasingly shorter time” (Fabris & Dal' Igna, 2013, p. 57). In these terms, neoliberal rationality converts

[...] the teacher in an employee of the system whose activity can be evaluated/measured like that of any other operator based on its effectiveness and the student in an oversized key product or human capital for the development of the national economy […] Efficientism pedagogical and human capital theory were found in the conceptual development of education. Both thoughts walked from their origin along parallel paths (Díaz-Barriga, 2014, p. 14, our translation)23.

In a mercantile society, the economic value of education and teaching translates into their ability to implement training mechanisms capable of leading to “[…] productive efficiency and professional insertion” (Laval, 2004, p. 19). A question that directly affects Brazilian high school teaching, configuring a new “[…] pedagogical ideal […]” (Laval, 2004, p. 3), related to the production of ‘neo-teaching’, aimed at training of flexible and autonomous subjects, oriented towards competitiveness, in a context that requires “[…] learning throughout life […]” (Laval, 2004, p. 3), valuing useful knowledge and with practical applicability.

In this dimension, in order to achieve the desired efficiency, the modern teaching configurations aimed at secondary education proposed the method as the foundation for achieving the expected results. “For that to happen, it will be necessary for the modern teacher, in addition to knowledge in their specialized field of culture, to have a ‘didactically well-oriented teaching technique’ and of proven ‘effectiveness’” (Escola Secundária nº 9, June 1959, p. 4, emphasis added).

“The teacher must be constantly ‘concerned with teaching techniques’ that offer better results and that best fit the reality of their students” (Escola Secundária nº 7, December 1958, p. 10, emphasis added).

In this regard, Pacheco and Pestana (2014, p. 27) show that the nuances of globalization and neoliberalism, by positioning the “[…] market as a matrix of educational solutions to economic problems […]”, have in the standardization of learning results, produced through large-scale assessments, a configuration that evokes the “[…] establishment of meritocracy as a motor of educational competitiveness”. In this context, the authors consider that terms such as “[…] quality, effectiveness, efficiency, performance, and competence […]” (Pacheco & Pestana, 2014, p. 25) reveal assumptions of a ‘market rationality’, which reflect on the perspective of teaching, by configuring “[…] teaching work as a result-oriented activity” (Pacheco & Pestana, 2014, p. 27). Since teaching is immersed in a process of accountability, evaluation takes on the character of “[…] accountability for the work performed by the teacher […]” (Pacheco & Pestana, 2014, p. 27), following productivist criteria.

In this scenario, the school is driven to meet these assumptions through a new characterization of education that, increasingly, “[…] tends to be considered as a commodity” (Charlot, 2007, p. 135). These assumptions show new challenges for teaching, considering that, in the words of Sibilia (2012, p. 43), from another theoretical perspective, the institutionalization process of schooling would be linked to the need to train “[…] subjects equipped to function efficiently within the historic project of industrial capitalism”.

In valuing instruction, the germ of the current emphasis on technical training to be successful in the labor market seems to reside - a type of teaching that is now often named using sports terms such as training or coaching, which imply exercising or drilling (Sibilia, 2012, p. 139).

The problematization of the centrality of the economic dimension in the knowledge society, where individual interests seem to overlap with the principles of collectivity, represents one of the nuances of the process of commodification of education and is accentuated in a contemporary society marked by neoliberal principles (Lima, 2012; Lenoir, 2016). In this scenario, characterized by the radicalization of individualism, the utilitarian perspective of knowledge is evidenced, in Lenoir’s view (2016, p. 161), especially through words such as efficiency, effectiveness, productivity, competitiveness, performance, and flexibility, which denote “[…] an entrepreneurial thought that invaded western educational systems”. In this way, in the author's view, “[…] the current education systems are managed as service companies, of the commodification of knowledge, which must function following the economic rules of the market” (Lenoir, 2016, p. 163).

Considering the effects of economic rationality in the educational field, we approach the theories of Díaz-Barriga (2014), when presenting that, from this context, productivist words arise in the education scenario, such as quality, performance evaluation, results, and competencies, likening the educational activities to a relationship between customer and product.

The new order in force, then, incorporates the school and education in the business culture, where the logic of individualization is also manifested in the accountability of each teacher for the results obtained, generating effects of competitiveness, in which efficiency and effectiveness become the main goals to be achieved.

In this perspective, the ‘pedagogical progressiveness’ that marks the educational thought of Anísio Teixeira, according to Silva (2017, p. 12), is also dimensioned according to “[…] a curriculum that expands training experiences based on interests of the individual who learns […]”, so that the school is re-signified to offer students the useful and necessary knowledge for life, according to the demands that emerge from the new configurations of society. This perspective is also analyzed by Biesta (2016, p. 20) when this author problematizes teaching centered on efficiency and on the search for better learning results, aimed at training the “[…] efficient student who will learn throughout his or her life”.

Braghini (2008, p. 3), expresses that, “[...] from the mid-1950s onwards, the main concern of researchers was to make secondary school more practical, to merge with the economicist appeals that, at that time, mingled with educational determinations”. Therefore, the New School intellectuals sought curricular changes that were adequate to the new concept of secondary education, and that would lead them to a modern, active, and more popular education (Braguini, 2008).

Unlike traditional forms of teaching, New Pedagogy “[…] removed the teacher as a fundamental figure and placed him or her as the organizer of learning conditions, with the student as the center of the process […]” (Schmidt, 2009, p. 154), in a context where the teacher is, at the same time, configured as “[…] an essential element of the student’s learning situation, as his or her role is, precisely, to orient, guide and stimulate the activity through the paths of knowledge and experience already conquered by the adult” (Schmidt, 2009, p. 150-151). “‘The teacher does not teach, but helps the student to learn’” (Lima, 1962, p. 90, 96, 100, 109, 114, 129, 136, 150, 165, 198, 245, 253, 260, 297, 328, 332, emphasis added).

Similarly, Escola Secundária Magazine also manifests a shift concerning the centrality of educational practice, which is now occupied by the student, presenting several recurrences that position the teacher as a promoter or guide of learning.

Instead of being an exponent and researcher of the subject, ‘[the teacher] is only the disseminator’ of its principles, its essential data, and its practical applications, having to reduce the subject to the understanding of his or her young students and make it functional in the face of the vital - non-specialized - needs of them (Escola Secundária nº 4, March 1958, p. 28, emphasis added).

Thus, the research materials reinforce that the “[…] secondary teacher is not a subject specialist, but, above all, a ‘disseminator of essential, certain and useful knowledge’” (Escola Secundária nº 4, March 1958, p. 28, emphasis added).

When the masters are convinced that their function is not to fill the minds with Physics, History or Chemistry students, but to ‘teach how to learn’, they will begin to behave more like ‘technicians’ than like ‘stars’ […] The ‘good teacher’, then, will no longer be the specialist who demonstrates his or her competence in each class, either through a stilted and high-sounding ‘speech’, or through his or her skill as prestidigitator [demonstration classes…], but will behave like a simple and solicitous ‘student learning guide’. The modern class is a workshop and not an auditorium. It is a place where one work under the guidance of a master (Lima, 1962, p. 118, emphasis added).

In this sense, the 20th century can be characterized by a significant change in the way of understanding the teaching-learning process, considering the transformation of a “[…] teaching centered on the transmission of contents and procedures to a teaching centered on active learning and significant on the part of the student” (Biesta, 2016, p. 10). Such transformation, according to the author, by evoking new methods and renovating practices, also made the student become the central figure in the learning process, reducing the teacher’s role to a facilitator, “[…] responsible for preparing the didactic resources and the educational setting, control of space and time in the classroom” (Biesta, 2016, p. 10). In this way,

[...] by conceiving education in these terms, we run the risk of eliminating what I consider essential for education, which is the presence of the teacher, not only as another colleague or facilitator of learning but as someone who, more generally, has something to add to the educational situation that was not there before (Biesta, 2016, p. 24, our translation)24.

Based on the recurrences that evidenced the teacher’s perspective, as a facilitator of learning, it is also important to highlight the centrality that teaching assumed within the developmental project that marked the 1950s and 1960s, as shown in the following excerpt. “The ‘teacher is arguably the most decisive factor’ in any secondary education plan. Curricula, programs, organization, and equipment, as important as they are, ‘mean little or nothing unless vitalized by the dynamic personality of the teacher’” (Escola Secundária nº 4, March 1958, p. 16, emphasis added).

In this perspective, while the teacher is no longer at the center of the educational process, in favor of the student’s activity, his or her importance is highlighted as a fundamental element in the implementation of the intended changes concerning secondary education and, consequently, concerning the new project of society, which was configured from the molds of industrialization. In this sense, Biesta (2016) elaborates an incisive critique of teaching perspectives reduced to a process that aims to facilitate the development of competencies, to guarantee previously established goals and results, defending a teaching configuration as a mechanism for empowerment and emancipation (Biesta, 2016).

Based on the principles of modern teaching, evoked for Brazilian secondary education in the 1950s and 1960s, it is possible to see that the specificities of the developmental project, based on a neoliberal economic rationality, contributed to the production of a ‘neo-teaching’ for this stage of schooling, which positions the teacher as a learning facilitator, built on the ideal of modernization and based on ‘pedagogical efficiency’. Under these conditions, teaching presents itself as an effective way to guide individual skills to the needs of modern life. In this regard, the production of a ‘neo-teaching’ that emerges from the period in question seems to represent, according to the analytical assumptions of Díaz-Barriga (2014, p. 14), the relationship between “[…] efficiency pedagogy and the theory of human capital […]”, in the context of economic development.

In this way, education, “[…] becomes a kind of economic transaction, where the teacher is a service provider and the learner (formerly a student) is a user” (Noguera-Ramírez & Parra, 2015, p. 77, our translation)25. Consequently, the research material investigated shows that the production of a ‘neo-teaching’ for secondary education was based on school-centered practices.

[...] ‘in efficiency and effectiveness (technologization), the replacement of teaching by therapeutics that addresses well-being and motivation to learn (psychologization)’, and the continuous infantilization produced by methods that counteract boredom - such as entertainment programs - but do not encourage study and effort (Noguera-Ramírez & Parra, 2015, p. 73, emphasis added, our translation)26.

Such analysis is linked to the idea that teaching must operate through a logic focused on individual performances capable of guaranteeing excellent results in large-scale assessments (Leite & Fernandes, 2010). A position that shows, “[…] under the conditions of neoliberal capitalism, in its different versions, an emphasis on training strategies that reinforce the effectiveness and productivity of individuals at their different levels of performance” (Silva, 2018, p. 183).

In these terms, contemporaneity implies that “[…] the source of efficacy is in the individual: it can no longer come from an external authority” (Dardot & Laval, 2016, p. 345). Thus, according to the authors, “[…] economic and financial correction turns into self-correction and self-blame, since we are the only ones responsible for what happens to us” (Dardot & Laval, 2016, p. 345).

Conceptual traits that indicate that the production of ‘neo-teaching’ was processed in a context of control exercised through a “[…] accounting subjectivation […]” of oneself (Dardot & Laval, 2016, p. 350), in which “[…] all domains of existence are within the competence of management itself […]” (Dardot & Laval, 2016, p. 345), and in which “[…] everyone feels threatened that one day they will become ineffective and useless” (Dardot & Laval, 2016, p. 350). Arguments that allow us to understand, in terms of the production of a ‘neo-teaching’, the ways in which the “[…] extension of mercantile rationality to all spheres of human existence is configured and that make neoliberal reason a true world-reason” (Dardot & Laval, 2016, p. 379).

Faced with a training perspective oriented towards profitability, in a business dimension, contemporary teaching faces a fundamental challenge, as it is committed to teaching that involves a “[…] set of values, dispositions, and senses of global responsibility that go beyond the limits of the knowledge economy” (Hargreaves, 2004, p. 21).

Final considerations

When considering the production of a ‘neo-teaching’ for Brazilian High School, throughout the second half of the 20th century, forged from a developmental project based on the amplification of the economy, guided by neoliberal molds, the search for pedagogical efficiency seems to have configured an essential mechanism to guide the teacher’s work, representing, according to the analytical assumptions of Díaz-Barriga (2014, p. 14), the relationship between “[…] pedagogical efficiency and the theory of human capital”.

Based on the discussions presented, it is possible to position pedagogical efficiency as an important rationale in the production of ‘neo-teaching’, from which specificities derive which materialize in the form of principles that signal the idea of an excellent teaching, capable of being translated into good results in large-scale evaluations. They are manifested in the teacher’s action in the classroom, through performative and innovative teaching, impelled to be increasingly competitive, individualized, and oriented towards the search for results. A dimension that results in practical guidelines for teaching work, manifested both in didactic and methodological terms and in relation to the organization of planning and teaching objectives. Orientations that end up becoming a ‘spectacle teaching’, based on playfulness, as a mechanism capable of capturing students’ attention and ensuring that the intended results are obtained.

At the same time, the emphasis expressed by the analyzed pedagogical forms, around pedagogical efficiency, denotes the expansion of teacher accountability and blaming for the results obtained, evoking the need for a process of renovation of secondary education, which took shape in the second half of the century XX, whose analysis is presented in the next section. Given this situation, it is important to warn about the importance of revitalizing teaching, in the sense of “[…] keeping teaching firmly connected to education as a democratic and progressive project, and not as a machine for the effective production of ‘results of learning’” (Biesta, 2016, p. 22).

It is important to point out that the problematizations of this article do not aim “[…] to affirm that the school institution must renounce its effectiveness” (Meirieu, 2009, p. 40), but to problematize the foundations of this perspective forged in a marked scenario by the intensification of neoliberal contours, which extend market specificities to the most diverse fields of society, including school and teaching. Thus, they configure a framework for the expansion of social pressures exerted on the school and on the teacher’s work. In these terms, what needs to be questioned are the effects of the search for pedagogical efficiency at any cost, because “[…] the omnipotent and fully effective didactic revokes the pedagogical event, in favor of conditioning […]” (Meirieu, 2009, p. 42), making the teaching activity something superficial and mechanical, capable of “[…] making the teacher dispensable” (Meirieu, 2009, p. 42).

Based on the analyses presented, it is possible to consider that “[…] the renewal of pedagogical rationality cannot be an individual or technical project, as it involves rethinking school work within the framework of the construction of a democratic and pluralist society” (Krawczyk, 2011, p. 767). Therefore, it is essential to question the true political and ethical dimension of educational systems, so that the teaching conceptions that appear in these spaces, move away from mere pedagogical instrumentalism that only contributes to accentuate, increasingly, contemporary social dilemmas.

Therefore, resuming ‘educational virtuosity'’ in the sense presented by Biesta (2016, p. 27), where the teacher has in his or her hands the authority to think and be able to choose the educational paths he/she considers most appropriate, translates into a truly committed teaching concept with the “[…] wonderful risk of educating”.

REFERENCES

Afonso, A. J. (2003). A educação superior na economia do conhecimento, a subalternização das ciências sociais e humanas e a formação de professores. Avaliação, 20(2), 269-291. DOI: https://doi.org/10.590/S1414-40772015000200002 [ Links ]

Ando, L. M. (2015). Lauro de Oliveira Lima e a Escola Secundária: um estudo de sua produção intelectual ao longo de sua trajetória profissional (1945-1964) (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Guarulhos. [ Links ]

Biesta, G. (2016). Devolver la enseñanza a la educación. Una respuesta a la desaparición del maestro. Pedagogía y Saberes, 1(44), 119-129. DOI: http://doi.org/10.17227/01212494.44pys119.129 [ Links ]

Braghini, K. M. Z. (2008). Democracia industrial: uma discussão sobre o fim do bacharelismo no ensino secundário. Educação, 33(2), 293-304. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5902/19846444 [ Links ]

Brasil. (1958). Programa de metas do Presidente JK: Estado do Plano de Desenvolvimento Econômico em 30 de junho de 1958. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Departamento de Imprensa. [ Links ]

Calixto, J. A., & Neto, A. Q. (2015). O educador. Revista Profissão Docente, 15(32), 140-155. [ Links ]

Campanha Nacional de Difusão e Aperfeiçoamento do Ensino Secundário [CADES]. (1957, junho). Escola Secundária, (1), 8. [ Links ]

Campanha Nacional de Difusão e Aperfeiçoamento do Ensino Secundário [CADES]. (1958, março). Escola Secundária , (4), 16-28. [ Links ]

Campanha Nacional de Difusão e Aperfeiçoamento do Ensino Secundário [CADES]. (1958, setembro). Escola Secundária , (6), 4. [ Links ]

Campanha Nacional de Difusão e Aperfeiçoamento do Ensino Secundário [CADES]. (1958, dezembro). Escola Secundária , (7), 10. [ Links ]

Campanha Nacional de Difusão e Aperfeiçoamento do Ensino Secundário [CADES]. (1959, junho). Escola Secundária , (9), 3-4. [ Links ]

Campanha Nacional de Difusão e Aperfeiçoamento do Ensino Secundário [CADES]. (1960, março). Escola Secundária , (12), 22. [ Links ]

Campanha Nacional de Difusão e Aperfeiçoamento do Ensino Secundário [CADES]. (1960, setembro). Escola Secundária , (14), 3-4. [ Links ]

Campanha Nacional de Difusão e Aperfeiçoamento do Ensino Secundário [CADES]. (1961, março). Escola Secundária , (16), 3. [ Links ]

Cellard, A. (2008). A análise documental. In J. Poupart, J.P. Deslauriers, L.H. Groulx, A. Laperriere, R. Mayer, & Á. Pires (Eds.), A pesquisa qualitativa: enfoques epistemológicos e metodológicos (p. 295-315). Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Charlot, B. (2007). Educação e globalização: uma tentativa de colocar ordem no debate. Sísifo - Revista de Ciências da Educação , 4, 129-136. [ Links ]

Chaves, M. W. (2006). Desenvolvimentismo e pragmatismo: o ideário do MEC nos anos 1950. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 36(129), 705-725. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742006000300010 [ Links ]

Cunha, M. V. (1996). Dewey e Piaget no Brasil dos anos trinta. Cadernos de Pesquisa , 97, 5-12. [ Links ]

Dale, R. (2004). Globalização e educação: demonstrando a existência de uma “cultura educacional mundial comum” ou localizando uma “agenda globalmente estruturada para a educação”? Educação e Sociedade, 25(87), 423-460. [ Links ]

Dardot, P., & Laval, C. (2016). A nova razão do mundo: ensaio sobre a sociedade neoliberal. São Paulo, SP: Boitempo. [ Links ]

Díaz-Barriga, Á. (2014). Competencias: tensión entre programa político y proyecto educativo. Propuesta Educativa, 2(42), 9-27. [ Links ]

Enguita, M. F. (2016). La educación en la encrucijada. Madrid, ES: Fundación Santillhana. [ Links ]

Fabris, E. T. H. (2018). A pedagogia do herói sob as performances das políticas públicas contemporâneas. Roteiro, 43(1), 205-224. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18593/r.v43i1.13097 [ Links ]

Fabris, E. T. H., & Dal’Igna, M. C. (2013). Processos de fabricação da docência inovadora em um programa de formação inicial brasileiro. Pedagogía y Saberes , 39, 49-60. [ Links ]

Fonseca, T. N. L. (2006). História & ensino de história. Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Hargreaves, A. (2004). O ensino na sociedade do conhecimento: educação na era da insegurança. Porto, PT: Porto Editora. [ Links ]

Hidalgo, A. M., & Mikolaiczyk, F. A. (2015). Os organismos internacionais e o projeto nacional-desenvolvimentista: o INEP e o projeto de modernização e democratização do país. Educação em Foco, 18(25), 99-123. DOI: http://doi.org/10.24934/eef.v18i25.336 [ Links ]

Ianni, O. (1989). Estado e planejamento econômico no Brasil. São Paulo, SP: Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Ide, M. H. S., & Rotta Júnior, C. (2013). Educação para o Desenvolvimento: a Teoria do Capital Humano no Brasil nas décadas de 1950 e 1960. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Jurídicos, 8(2), 125-144. [ Links ]

Kilpatrick, W. H. (1964). Educação para uma civilização em mudança. São Paulo, SP: Melhoramentos. [ Links ]

Krawczyk, N. (2011). Reflexão sobre alguns desafios do ensino médio no Brasil hoje. Cadernos de Pesquisa , 41(144), 752-769. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742011000300006 [ Links ]

Lafer, C. (2002). JK e o programa de metas, 1956-1961: processo de planejamento e sistema político no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: FGV. [ Links ]

Laval, C. (2004). A escola não é uma empresa: o neoliberalismo em ataque ao ensino público. Londrina, PR: Planta. [ Links ]

Leite, C., & Fernandes, P. (2010). Desafios aos professores na construção de mudanças educacionais e curriculares: que possibilidades e que constrangimentos? Educação , 33(3), 198-204. [ Links ]

Lenoir, Y. (2016). O utilitarismo de assalto às ciências da educação. Educar em Revista, 61, 159-167. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.47109 [ Links ]

Lima, L. O. (1962). A escola secundária moderna. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Fundo de Cultura. [ Links ]

Lima, L. (2012). Aprender para ganhar, conhecer para competir: sobre a subordinação da educação na “sociedade da aprendizagem”. São Paulo, SP: Cortez. [ Links ]

Meirieu, P. (2009). Carta a um jovem professor. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. [ Links ]

Noguera-Ramírez, C. E., & Parra, G. A. (2015). Pedagogización de la sociedad y crisis de la educación. Elementos para una crítica de la(s) crítica(s). Pedagogía y Saberes , 43, 69-78. [ Links ]

Nunes, C. (2000). O “velho” e “bom” ensino secundário: momentos decisivos. Revista Brasileira de Educação , 14, 35-60. [ Links ]

Pacheco, J. A., & Pestana, T. (2014). Globalização, aprendizagem e trabalho docente: análise das culturas de performatividade. Educação , 37(1), 24-32. DOI: http://doi.org/10.15448/1981-2582.2014.1.15013 [ Links ]

Popkewitz, T. S. (1997). Reforma educacional: uma política sociológica-poder e conhecimento em educação. Porto Alegre, RS: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Popkewitz, T. S. (2015). La práctica como teoría del cambio: investigación sobre profesores y su formación. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 19(3), 428-453. [ Links ]

Rosa, F. T., & Dallabrida, N. (2016). Circulação de ideias sobre a renovação do ensino secundário na revista escola secundária (1957-1961). História da Educação , 20(50), 259-274. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/61595 [ Links ]

Sander, B. (1995). Gestão da educação na América Latina: construção e reconstrução do conhecimento. Campinas, SP: Autores Associados. [ Links ]

Santos, T. M. (1961). Manual do professor secundário. São Paulo, SP: Companhia Editora Nacional. [ Links ]

Schmidt, I. A. (2009). John Dewey e a educação para uma sociedade democrática. Contexto e Educação , 24(82), 135-154. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21527/2179-1309.2009.82.135-154 [ Links ]

Schultz, T. W. (1987). Investindo no povo: o segredo econômico da qualidade da população. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Forense Universitária. [ Links ]

Sibilia, P. (2012). Redes ou paredes: a escola em tempos de dispersão. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Contraponto. [ Links ]

Silva, M. V., & Souza, S. A. (2009). Educação e responsabilidade empresarial: “novas” modalidades de atuação da esfera privada na oferta educacional. Educação & Sociedade, 30(108), 779-798. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302009000300008 [ Links ]

Silva, R. R. D. (2017). Especificidades da emergência da contemporaneidade pedagógica no Brasil: apontamentos para uma história do currículo escolar. In Anais da 38ª Reunião Nacional da ANPEd (p. 1-16). São Luís, MA. [ Links ]

Silva, R. R. D. (2018). Estetização pedagógica, aprendizagens ativas e práticas curriculares no Brasil. Educação & Realidade, 43(2), 551-568. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623667743 [ Links ]

Teixeira, A. (1957). Bases para uma programação da educação primária no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, 27(65), 28-46. [ Links ]

Vieira, E. (1983). Estado e miséria social no Brasil de Getúlio a Geisel. São Paulo, SP: Cortez . [ Links ]

Waschinewski, S. C., & Rabelo, G. (2017). A escola agora é outra: o Programa de Assistência Brasileiro Americana ao Ensino Elementar - PABAEE (1956 a 1964). Educação , 42(3), 535-554. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5902/1984644428089 [ Links ]

Period between two extremely authoritarian moments in Brazil: Vargas’ Estado Novo and the military dictatorship established in 1964 (Vieira, 1983).

Eighteen issues were published quarterly, between 1957 and 1963, with around twenty-one articles per issue (Rosa & Dallabrida, 2016).

In this study, we highlight, in the construction of the foundations of the ‘new school’, especially the influence of John Dewey (1958), when addressing the link between school and social development, based on the principles of democracy; Claparéde (1973), when proposing a tailor-made school, considering individual specificities, placing the student at the center of the educational process; and Ferrière (1934), whose work focused on promoting a new way of teaching for a new school, based on genetic psychology.

It emerges from the theories of Francis Bacon, being taken up in the 19th century by Charles Pierce and inserted in the educational field, in the 20th century, by John Dewey (Chaves, 2006).

In the original: “[…] la sociedad precisó y se dotó masivamente de una institución, la escuela, y una profesión, los maestros, a las que encomendar esa tarea: la modernización, conducir a las nuevas generaciones a una nueva sociedad”.

Popkewitz (2015) analisa tais pressupostos sobre a caracterização de um novo docente a partir das orientações do programa ‘Teach for America’, que propõe um conjunto de estratégias formativas aos professores iniciantes, orientadas para a excelência profissional. Em termos de agendas educativas, é importante assinalar que as políticas educacionais propostas para o Ensino Médio brasileiro inscrevem-se em um quadro caracterizado por Dale (2004) como agenda globalmente estruturada para a educação.

In the original: “El profesor debe actuar intencionadamente por medio de el establecimiento de objetivos, invirtiendo en estudiantes, planificando deliberadamente, ejecutando de manera efectiva, incrementando de manera continuada la efectividad, y trabajando inexorablemente. Las cualidades psicológicas de ser determinado, efectivo, y trabajar sin descanso van de la mano con actuar con exactitud en seguir el material docente, siendo equilibrado y auto supervisado. Las cualidades están vinculadas además con las actitudes de las creencias del profesor, relaciones con otros, gratitud y optimismo, y manejo de tiempos y actitudes, lenguaje no verbal, y realizar lecciones memorables”.

In the original: “[...] el docente en un empleado del sistema cuya actividad puede ser evaluada/medida como la de cualquier otro operario en función de su efectividad, y al alumno en un producto o capital humano clave sobredimensionado para el desarrollo de la economía nacional [...] Eficientismo pedagógico y teoría del capital humano se encontraron en el desarrollo conceptual de lo educativo. Ambos pensamientos caminaron desde su origen por caminos paralelos”.

In the original: [...] al concebir la educación en estos términos, corremos el riesgo de eliminar lo que considero esencial para la educación, que es la presencia de un profesor, no solo como otro compañero o facilitador del aprendizaje, si no como alguien que, en términos más generales, tiene algo que aportar a la situación educativa que no estaba allí antes”.

In the original: "[...] se torna en una especie de transacción económica, donde el maestro es un proveedor de servicios y el aprendiente (antes estudiante) es un usuario”.

In the original: "[...] en la eficiencia y la eficacia (tecnologización), la sustitución de la enseñanza por una terapéutica que se ocupa del bienestar y la motivación para aprender (psicologización), y la infantilización continua producida por métodos que contrarrestan el aburrimiento - como los programas de entretenimiento - pero no fomentan el estudio y el esfuerzo”.

The authors were responsible for designing, analyzing, and interpreting the data; writing and critical review of the manuscript content, and approval of the final version to be published.

O pensamento desenvolvimentista situa-se no âmbito da economia política e ancora-se nas ideias de Keynes, responsabilizando o Estado pela orientação e crescimento econômico (Chaves, 2006).

Período entre dois momentos extremamente autoritários no Brasil: o Estado Novo de Vargas e a ditadura militar implantada em 1964 (Vieira, 1983).

O Programa ou Plano de Metas, como é mencionado por diversos autores, foi um dos maiores projetos de desenvolvimento econômico envolvendo o Estado, como propulsor e idealizador do processo de aceleração industrial, pró-desenvolvimento econômico do país. Por meio do reaparelhamento e fomento econômico na esfera federal, o Plano de Metas, visava o aumento contínuo da capacidade de investimentos no país, mediante a conjugação de esforços do capital privado (nacional e estrangeiro) com assistência do setor público, suplementando esforços e produzindo incentivos para o capital estrangeiro (Lafer, 2002). Ao lado do Plano de Metas, o período em questão também teve o Plano Salte (1949-1954) e o Plano Trienal (1963-1965) (Ianni, 1989).

Intelectual fluminense ligado ao campo da Educação Católica, de base escolanovista, atuou como Diretor Técnico Profissional, Diretor da Educação Primária e Diretor geral do departamento da Educação Básica. Concomitante com estas funções, lecionou Filosofia, História da Educação e Pedagogia, cujas obras totalizam aproximadamente 130 volumes (Calixto & Neto, 2015).

Professor cearense, cujos pressupostos centraram-se em favor do desenvolvimento do método psicogenético na educação, segundo as teorizações de Piaget. Foi autor de mais de trinta obras relacionadas à educação (Ando, 2015).

Foram dezoito números publicados trimestralmente, entre 1957 e 1963, apresentando em torno de vinte e um artigos por edição (Rosa & Dallabrida, 2016).

Para fins deste estudo, destacamos, na construção dos fundamentos da ‘escola nova’, especialmente a influência de John Dewey (1958), ao abordar a vinculação da escola ao desenvolvimento social, a partir dos princípios da democracia; Claparéde (1973), ao propor uma escola sob medida, ao considerar as especificidades individuais, posicionando o aluno no centro do processo educativo; e Ferrière (1934), cujos trabalhos centravam-se na promoção de uma nova docência para uma nova escola, a partir da psicologia genética.

Emerge a partir das teorizações de Francis Bacon, sendo retomado no século XIX por Charles Pierce e inserido no campo educacional, no século XX, por John Dewey (Chaves, 2006).

No original: “[…] la sociedad precisó y se dotó masivamente de una institución, la escuela, y una profesión, los maestros, a las que encomendar esa tarea: la modernización, conducir a las nuevas generaciones a una nueva sociedad”.

Popkewitz (2015) analisa tais pressupostos sobre a caracterização de um novo docente a partir das orientações do programa ‘Teach for America’, que propõe um conjunto de estratégias formativas aos professores iniciantes, orientadas para a excelência profissional. Em termos de agendas educativas, é importante assinalar que as políticas educacionais propostas para o Ensino Médio brasileiro inscrevem-se em um quadro caracterizado por Dale (2004) como agenda globalmente estruturada para a educação.

No original: “El profesor debe actuar intencionadamente por medio de el establecimiento de objetivos, invirtiendo en estudiantes, planificando deliberadamente, ejecutando de manera efectiva, incrementando de manera continuada la efectividad, y trabajando inexorablemente. Las cualidades psicológicas de ser determinado, efectivo, y trabajar sin descanso van de la mano con actuar con exactitud en seguir el material docente, siendo equilibrado y auto supervisado. Las cualidades están vinculadas además con las actitudes de las creencias del profesor, relaciones con otros, gratitud y optimismo, y manejo de tiempos y actitudes, lenguaje no verbal, y realizar lecciones memorables”.

No original: “[...] el docente en un empleado del sistema cuya actividad puede ser evaluada/medida como la de cualquier otro operario en función de su efectividad, y al alumno en un producto o capital humano clave sobredimensionado para el desarrollo de la economía nacional [...] Eficientismo pedagógico y teoría del capital humano se encontraron en el desarrollo conceptual de lo educativo. Ambos pensamientos caminaron desde su origen por caminos paralelos”.

No original: [...] al concebir la educación en estos términos, corremos el riesgo de eliminar lo que considero esencial para la educación, que es la presencia de un profesor, no solo como otro compañero o facilitador del aprendizaje, si no como alguien que, en términos más generales, tiene algo que aportar a la situación educativa que no estaba allí antes”.

No original: "[...] se torna en una especie de transacción económica, donde el maestro es un proveedor de servicios y el aprendiente (antes estudiante) es un usuario”.

No original: "[...] en la eficiencia y la eficacia (tecnologización), la sustitución de la enseñanza por una terapéutica que se ocupa del bienestar y la motivación para aprender (psicologización), y la infantilización continua producida por métodos que contrarrestan el aburrimiento - como los programas de entretenimiento - pero no fomentan el estudio y el esfuerzo”.

Received: June 09, 2019; Accepted: May 26, 2020

![El Derecho Civil en ‘Rosaura, a enjeitada’ de Bernardo Guimarães: “[…] problema eterno e insoluble [...]”](/img/es/prev.gif)

texto en

texto en