Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Acta Scientiarum. Education

versión impresa ISSN 2178-5198versión On-line ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.43 Maringá 2021 Epub 01-Sep-2021

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v43i0.51342

TEACHERS' FORMATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

The cycles of human development with study complexes of the Itinerant School of Paraná

1Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Avenida Colombo, 5790, 8700-900, Maringá, Paraná, Brasil..

²Universidade Estadual do Paraná, Paranavai, Paraná, Brasil.

This text addresses the curricular organization of study complexes such as the development project for itinerant schools in Paraná. It contextualizes the need for the schooling of children from peasant families who experience different processes of expropriation and exclusion and who collectively organize themselves in the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST) to achieve the Agrarian Reform and citizen rights. Through bibliographic and documentary research, it highlights the relevance of education for the MST and makes a history of the development of the curriculum organization by Human Development Cycles with Study Complexes aiming at the humanization process in school formation. It concluded that, in times of systematic attacks on social rights and public education by the capitalist system, the curricular organization of the MST at work in the Itinerant Schools of Paraná contributes to constitute pillars of resistance and compose the debate overcoming the standardization of the curriculum.

Keywords: curriculum; field education; itinerant school; paraná

O presente texto aborda a organização curricular por complexos de estudo como projeto formativo para escolas itinerantes no Paraná. Contextualiza a necessidade de escolarização das crianças provenientes de famílias de camponeses que vivenciam diferentes processos de expropriação e de exclusão e que se organizam, coletivamente, no Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST) para a conquista da reforma agrária e dos direitos de cidadania. Por meio de pesquisa bibliográfica e documental, evidencia a relevância da educação para o MST e faz um histórico do desenvolvimento da organização curricular por Ciclos de Formação Humana com Complexos de Estudo visando ao processo de humanização na formação escolar. Conclui que, em tempos de ataques sistemáticos aos direitos sociais e à educação pública, pelo sistema capitalista, a organização curricular do MST em exercício nas Escolas Itinerantes do Paraná contribui para a constituição de pilares de resistência e composição do debate em superação da estandardização curricular.

Palavras-chave: currículo; educação do campo; escola itinerante; Paraná

El texto discute la organización curricular por complejos de estudio como un proyecto de capacitación para escuelas itinerantes en la província del Paraná. Contextualiza la necesidad de escolarizar a los niños de familias campesinas que experimentan diferentes procesos de expropiación y exclusión y que se organizan colectivamente en el Movimiento de Trabajadores Rurales sin Tierra (MST) para lograr la reforma agraria y los derechos de ciudadanía. Com investigación bibliográfica y documental, destaca la relevancia de la educación para el MST y hace una historia del desarrollo de la organización del currículo por los ciclos de formación humana con complejos de estudio que apuntan al proceso de humanización en la formación escolar. Llega a la conclusión de que, en tiempos de ataques sistemáticos contra los derechos sociales y la educación pública por parte del sistema capitalista, la organización curricular del MST en el trabajo en las escuelas itinerantes de Paraná, contribuye a constituir pilares de resistencia y componer el debate sobre la superación del plan de estudios de estandarización.

Palabras clave: currículum; educacion del campo; escuela itinerante; Paraná

Introduction

This text aims to discuss the development of the curricular organization by Cycles of Human Formation with Study Complexes in the Itinerant School of the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST) of Paraná, in its connection with the formative challenges of the struggle for Popular Agrarian Reform. The study was carried out through bibliographical and documentary research with sources that deal with education in the MST and the development of the curricular organization of the Itinerant School in Paraná.

The text addresses, first, elements of the contextualization and struggle for the Itinerant School in land occupations in Paraná. Next, it presents an analysis of the embryos of the curricular dimensions that, since the late 1980s, have been developing in the struggle for MST education, involving issues of didactics, teaching, and curricular dimensions of a structuring amplitude of the curriculum.

We explain the curricular organization by Cycles of Human Formation with Study Complexes in the context of Itinerant Schools of Paraná, presenting the fundamentals and curricular dimensions that integrate the collective work of transforming the form and content of the school curriculum, so that it articulates the educational work in schools with the humanization process and the social changes that the MST's struggle assists in constructing.

In this constant, the Itinerant School has highlighted the possibility of building the school against the hegemonic by reaffirming that this is a “[…] task of the working class in the present. If we don't make this school now, it won't exist tomorrow. It is a school of contradiction, daring, the construction of the real, the possible and the impossible within capitalism” (Grein, 2019, p. 11). This school aims, permanently, to respond to the educational aspirations of the working class and, even in the most adverse conditions, it seeks to educate in the contradictions and act in the formation of ‘fighters’ of the present and ‘builders’ of embryos of socialist society (Sapelli, Leite & Bahniuk, 2019).

We highlight the innovation of the Itinerant School in terms of school organization and the overcoming of conventional curricular forms restricted to the dimension of teaching. We highlight the challenges of developing curricular practices that aim to raise the level of knowledge of students concerning labor and its contradictions through the use of concepts, categories, and procedures of the different sciences and arts that are the object of study, in conjunction with the whole from the curricular dimensions that transcend bookish and verbal teaching, through socially necessary work practices, the self-organization of students and the linking of knowledge to portions of reality.

Contextualization of the Itinerant School of Paraná

The land tenure situation in the country, with large tracts of land occupied by monoculture and farms with mechanized production, expropriated, and still expropriates, thousands of families who now make up a Landless contingent, without work, without access to food, drinking water, housing, and schooling. The Landless Rural Workers Movement originated from the organization of families in support of struggles for human rights, with education as one of the central issues. According to Ianni (1984), democracy in Brazil never reached the countryside. The little that has been done, in terms of public policies, has been and continues to be the result of peasant and indigenous struggles.

In 1990, the World Conference on Education for All, held by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Jomtiem, made public that more than 100 million children in the world, mostly girls, did not have access to school, literacy, and basic education and that more than 960 million adults, mostly women, were illiterate. During the 2000s, the Map of Illiteracy in Brazil (INEP, 2000) showed that the greatest exclusion was among rural populations where the illiteracy rate was twice the national average.

In Paraná, in 2003, there were numerous families in camps, with many children of school age, and the schools surrounding the camps did not have enough structure to house them. Faced with the movement’s struggle and demand, the government of Paraná, through the State Council of Education - CEE, recognized and authorized, through Opinion No. 1012/2003, the functioning of the ‘Traveling School in the context in which Landless workers are in a situation of encampments, which can change place at any time’.

It has been 15 years since the right to school education was achieved in land occupations in Paraná. A school that was born from the struggle for access and guarantee of school education for the encamped populations. Since its origin, with legal recognition in Rio Grande do Sul in 1996, the Itinerant School assumes the political-pedagogical posture of walking together, carrying out the itinerancy, following the territorial movement of the encamped families, whether in cases of evictions, in mobilizations, in marches or in occupations, aiming to ensure the right to schooling for children, youth, and adults living in the camps.

People had the opportunity to access schooling in the place where they live, which has contributed to creating, in students, greater longing for school, study, and work, collaborating with the socialization and appropriation of knowledge and the development of communities. Currently, there are ten Itinerant Schools that guarantee access to schooling for approximately 1,500 students in eight municipalities. The existence of these schools expresses the conquest and the constant struggle for the right to education. On the other hand, this existence evidences the slowness and moroseness in Paraná of the necessary and urgent agrarian reform. There are cases, such as the one in the camp where the Paulo Freire Itinerant School is located, which, since 2003, has been subject to provisional, excluding conditions and to the inclement weather of nature (Sapelli et al., 2019).

Not unlike the history of struggle and achievements of other schools in the MST, the Itinerant School is the result of many conflicts, as the State must fulfill the right to education for all, it is its duty to create structural conditions and access. As a counterpoint to the precariousness of access to education for all by the Brazilian State, the encamped communities act to guarantee the school with the construction of alternative structures for its functioning, concomitantly with the struggle for the right to finance and maintain this school as a duty of the State.

Amid the temporary life of the camp, the school collectives in Itinerant Schools have taken on the challenge of exercising political and curricular autonomy to enable access and appropriation of the bases of science and art to scientifically know and interpret the reality, so that students learn to study, work and live collectively and to be subjects of social changes in their historical time. The Itinerant School is an organic part of the camp, as there is an understanding that it should not only be located in the camp, but also be part of it, to be integrated into its struggle, to be permeated by the political and pedagogical content of the struggles, mobilizations, and discussions present in the communities. It means learning and teaching while fighting for human rights.

It was the link with the concrete life of the Landless families that allowed the MST to develop a concept of its own education. This conception goes beyond the school and aims to acquire pedagogical intention through the school curriculum. The MST, since its origins in the work with school education, has faced the need for a curricular organization that increases the pedagogical intention of the school in relation to the struggles, collective organization, work, culture, and contradictions that make up social life. Thus, it is assumed that the challenge of constituting a school curriculum that provides the links between knowledge while being open to new educational processes, encompassing the social struggle, has a political and organizational character of the subjects involved with the Itinerant School.

The educational practice of the MST and the development of an engaged curriculum organization

Since the creation of the MST in the 1980s, embryos of the curricular design and prescription have been identified that progressively developed in the struggle for education, encompassing issues beyond didactics or teaching, but contemplating curricular dimensions with structuring scope of the curriculum. These embryos have their historical roots in the first Landless camps, constituting the stage for the first educational experiences, especially the Landless families, camped at the crossroads of Natalino, Rio Grande do Sul (1981), who sought ways to explain to children why they were camped. The concern at that time was not schooling, “[…] but taking care of the children, preventing them from being too exposed to the dangers of living on the side of the road and discussing with them the struggle in which they were necessarily participating” (MST, 2005, p. 12).

The entry of education into MST’s agenda occurred through childhood. The encamped families soon perceived childhood education as a great and necessary challenge (Kolling, Vargas, & Caldart, 2012). This becomes visible when, in the first camps, there are many children camped with their families and the question of what to do with them is presented, since they were frequently out of school and without access to it, especially in times when the camps were evicted and families were forced to move to another location, often far away, or when the schools themselves discriminated against the camped children because they didn't have a home, a fixed address.

This exclusion spurred the organization and struggle, in the MST, for public schools in camps and settlements, as part of the Agrarian Reform project. “Almost at the same time it began to fight for land, the MST, through the camped and later settled families, began to fight for access to school” (Kolling, Vargas, & Caldart, 2012, p. 503). Although the families prioritized the conquest of land, an understanding was developed that this was not enough.

If the land represented the possibility of working, producing, and living with dignity, they lacked a fundamental instrument for the fighting community. Continuing the struggle required knowledge both to deal with practical matters and to understand the economic and social-political situation. A double-targeting weapon for the Landless, education became a priority for the Movement. (Morissawa, 2001, p. 239)

Since then, education has been guided by the political struggle of this movement. The first achievement of the right to school for all occurred with the Rio Grande do Sul Department of Education, at the Nova Ronda Alta Rumo à Terra Prometida camp. In May 1982, there were 180 children of school age, but this right was fully legalized in April 1984, in the Nova Ronda Alta settlement (MST, 2005). Then, in 1985, in Sarandi/RS, the second experience of school in camp was developed (MST, 2005). The MST understands that the process of emancipation of the working class requires the appropriation, in essence, of the real factors that subordinate life to the interests of capital. It is an essential condition for effective social transformation, a condition that permeates training and education for understanding the role of each individual in human history (MST, 2006). Therefore, the MST itself, in its struggle and organization, becomes profoundly educational.

Initially,

[…] the concern was for the future of the many children in camp; then, the achievement of the legal school; and, right after, the type of teaching to be developed in that school, which had to be necessarily different given the circumstances and the type of students (Morissawa, 2001, p. 239-240).

The preoccupation with the type of teaching, by the MST, concerns the necessary curricular changes to help respond to the formative challenges that the struggle for Agrarian Reform requires.

[…] the MST was consolidating its conviction that the school should be treated as a place of human formation, and that a proposal for a school linked to the movement cannot be restricted to issues of education, but should address all the dimensions that constitute its educational environment. (Kolling et al., 2012, p. 508).

The collective dedication to the formulation of a concept of school education gained strength as the first settlements and schools were carried out in 1985/1986, culminating in the 1st National Seminar on Education in Settlements in 1987, held in the State of Espírito Santo and which resulted in the first national guidelines of the MST in the context of school education. The period between 1979 and 1991 is characterized as the constitution of the school issue in the MST in which the need to have a school curriculum in tune with the struggle became present (Dalmagro, 2010), ranging from the need for education to essays for alternative solutions in the curriculum. (MST, 2017).

Understanding the need to combine the struggle for access to school education with the struggle against the State’s pedagogical and curricular policy protection challenged the MST to work towards the construction of a school curriculum based on the principles and objectives of the movement itself. This vision propelled the incorporation of the MST’s formative objectives to project transformations in the ‘form and content of the school curriculum’. Such transformations placed school educational work at the service of the development of society that the struggle for equal rights aims to help in the construction. In the context of education, this work assumes the objective of forming fighters for and builders of a new social order (MST, 2013). The task of modifying the social order requires human beings with mastery of knowledges that contribute to the conduct of social and productive processes. People, therefore, who know how to work and live collectively, having as reference the socialist project of sociability.

The first documents produced by the MST contain consistent indications of the pillars of the formulation of its own curricular organization, which, throughout the MST’s educational proposal, acquired new methodological arrangements, based on ‘work as an educational principle’.

An expression still under development appears in the Sem Terra newspaper from April 1989, where at least three principles of its education proposal stand out (MST, 1989, p. 4): the need to establish a relationship between the educational and organizational process, seeking to build “[…] education in organized action and for organized action […]”; the integral formation of the subjects; and the unity between theory and practice, proposing social practice as a starting point and considering three tasks in relation to universal knowledge: appropriating it, criticizing it, and producing new knowledge (Sapelli, Leite, & Bahniuk, 2019).

In the production entitled Caderno de Formação n.º 18 do MST for the settlement schools, work is made explicit as an educational principle in the guiding pedagogical principles: ‘Fundamental educational value of work and collective organization’;

In the settlement schools, an emphasis on the issue of work is essential: at the same time starting from the practical experience of the settlement production and providing a scientific and technological preparation that helps in the advancement of productive and organizational practice (MST, 1991, p. 6).

The 1991 text Educação no Documento Básico do MST reaffirms the need to “[…] have work and collective organization as fundamental educational values”. We highlight, among the principles presented, the “[…] methodology based on the dialectical conception of knowledge” and the need for the school to “[…] produce the bases of the minimum scientific knowledge necessary for the advancement of production and organization in the settlements […]” (MST, 2005, p. 29).

Dated July 1991, the document O que queremos com as escolas dos assentamentos indicates that all teaching should start from practice, work experience, organization of social relations, having as the cyclical principle of the educational process the practice-theory-practice, proposing that “[…] teaching should always start from the reality experienced by the child. The theory, the contents […] that serve to help reflect on reality […] must help transform reality and our lives” (MST, 2005, p. 34). The document presents objectives and principles for MST schools, with fruitful indications of curriculum construction aimed at changing scholastic form and content:

1) Teach how to read, write, and calculate reality; 2) teach by doing, that is, through practice; 3) build the new; 4) prepare equally for manual and intellectual work; 5) teach local and general reality; 6) generate subjects of history; 7) preoccupy about the whole person (MST, 2005, p. 34).

And it brings as pedagogical principles: 1) everyone to work; 2) everyone getting organized; 3) everyone participating; 4) every settlement in the school and every school in the settlement; 5) all teaching starting from practice; 6) every teacher is a militant; 7) all educating themselves for the new.

The accumulation built with the formulations and curricular practices that preceded the year 1996 allowed the formulation present in the July 1996 Education Booklet n. 08 - Princípios da Educação do MST, understood as fundamental foundations of MST Education (Dalmagro, 2010), which evolved into new dimensions, synthesizing a concept of education that emphasized the link with the political and societal project (MST, 2005).

The principles are divided into ‘philosophical and pedagogical’; the first concern the worldview, general conceptions in relation to the human being, society and the understanding of education; education for work and cooperation stand out by stating that educational practices should consider “[…] the issue of the struggle for agrarian reform and the challenges it poses for the implementation of new relations of production in the countryside and in city” (MST, 2005, p. 163). These principles are part of a conception of education as an omnilateral human formation process, which should contribute to developing different human dimensions: affective, intellectual, political, ethical, bodily, aesthetic, social and organizational, among others. Drawing “[…] attention to the fact that a revolutionary educational praxis should be able to reintegrate the different spheres of human life that the capitalist way excels in separating” (MST, 2005, p. 163).

‘Pedagogical principles’ refer to the way of doing and thinking about education in order to materialize philosophical principles, such as the relationship between theory and practice; combination of teaching and training processes; reality as the basis for knowledge production; socially useful formative contents; education for work and through work; organic links between educational and political processes, between educational and economic processes; organic link between education and culture; democratic management; students’ self-organization; creation of pedagogical groups and ongoing training of educators; attitude and research skills; forging in the fight (MST, 2005).

The principle ‘reality as the basis of knowledge production’, which is not limited to the encampment/settlement and its surroundings, but to the global reality, guides the need for appropriation and methodological development that provides “[…] constantly [links] from the particular to the general and from the general to the particular” (MST, 2005, p. 168). The methodological principle of teaching through generative themes is proposed, which contributes to the qualification and organization of teaching processes in interface with reality, as a way to overcome bookish teaching and inert contents (MST, 2005). The training contents must be socially useful, observing the need for school work to promote equal access to knowledge produced by humanity.

The principle ‘education for work and through work’ is divided into two complementary dimensions: 1) education linked to the world of labor, whose understanding is that the pedagogical processes of the school “[…] cannot ignore the demands of increasingly complex production processes, whether in society in general or in settlements in particular” (MST, 2005, p. 169); and 2) work as a pedagogical method, concerning the relationship between study and labor, fundamental in the development of the dimensions of the MST’s education proposal.

In the movement’s educational principles, the need for school education to work from a historical perspective in connection with the historical challenges of its time is emphasized. “It means an education that organizes itself, that selects content, that creates methods from the perspective of building the hegemony of the political project of the working class” (MST, 2005, p. 161). With this understanding and philosophical and pedagogical basis, oriented from the ‘Pedagogia do Movimento’ (Pedagogy of Movement), the Education Sector of the MST has sought to establish in some Brazilian states a curriculum proposal that articulates school content and form, based on work as an educational principle. The aim is to preserve educational work based on science, art, culture, and technologies engendered by human beings throughout history (Antonio & Rodrigues, 2014).

In the course of the development of the MST school project, since the first formulations in the 1980s, the ‘Educação Popular’ (Pedagogy of the Oppressed), the ‘Escola Única do Trabalho’ (Soviet Socialist Pedagogy), and the theoretical and practical development of the ‘Pedagogia do Movimento’ itself (Caldart, 2012) were present as the matrix of the educational and curricular work of the MST schools. In the school context of ‘Educação Popular’, there is an understanding of education as essentially political and the incorporation of generating themes as a methodological option to materialize, in curricular practice, the link between teaching, work and reality; of the ‘Escola Única do Trabalho’, there is essentially the incorporation of work as a fundamental principle and the dimension of students' self-organization.

Until 2009, there was only the work Fundamentos da Escola do Trabalho (1981) by Pistrak, published in Brazil on the subject. In 2009, Professor Luiz Carlos de Freitas translates the original in Russian, organizes and publishes, through the Expressão Popular publisher, the book Escola-Comuna, which consists of a detailed report of the work carried out at the Lepeshinnskiy school (Sapelli et al., 2019).

Since then, based on the partnership between the Education Sector of the MST and Luiz Carlos de Freitas (Unicamp), as part of this process of pedagogical and curricular (re)formulation, the MST in Paraná has planned a long collective work, from 2010 to 2013, which allowed the analysis and appropriation of the curriculum dimensions accumulated by the experience of the Escola Única do Trabalho with the Study Complexes, post-Russian revolution, between 1917 and 1929. This process had as its starting point the critical reading and the limits of the Soviet experience, systematized by Pistrak in his self-criticism in the work Escola-Comuna (2009), plus a critical rereading developed by the collective of educators - curriculum specialists, specialists in various areas of knowledge, the MST’s collective of education and professionals who worked with the issue of pedagogical theory, integrating education workers from various state and federal universities (Sapelli et al., 2019).

Initially, the process of formulating a new curricular matrix aimed to sieve the practice in the Itinerant Schools of Paraná, by understanding that, even though they are part of the Paraná State Education Network, these schools represent a favorable space for experimenting a new school form that raises the cultural level of the encamped population, bearing in mind that its management and organization are communitarian and, thus, have greater decision-making autonomy vis-à-vis the state bureaucracy.

The various steps that constituted the process are described as follows:

Study moments on the Soviet and MST proposal; evaluation of the MST proposal forged since the 1980s; elaboration of inventories of the reality in which schools are inserted; exercises for the development of contents and objectives (training and teaching), for the relationship between objectives and portions of reality/categories of practice; systematization of the Study Plan; continued training of school collectives [educators and camped community]; definition of pedagogical matrices; discussions about school form (Sapelli, 2017, p. 620).

As a result of this work, in early 2013, the first version of the result of the curriculum development by Study Complexes was published in the document entitled Plano de Estudos da Escola Itinerante (MST, 2013), which reached schools as the starting point for the Study Complexes experiment in communities. Although many curricular dimensions were already in place, such as the use of formative objectives in planning, constitution of sectoral nuclei, construction of the reality inventory, definition of portions of reality and qualification of collective planning (Sapelli, 2017), the process has expanded and strengthened.

In order to qualify the appropriation of theoretical foundations and the logic of Study Complexes, a new ‘Training Program for Educators of the Itinerant School of Paraná’ was organized in 2013, covering different subjects involved in school work: educators, students and community. This formative and continued strategy was organized in different stages and formats, from the formation of the state pedagogical collective, the collective of educators at the school, interface with the community and students, to the holding of state meetings involving these different subjects. In this process, the MST education sector, in partnership with universities, integrated the initial training courses of MST educators at a higher level with postgraduate subjects to deepen and research their own experience. With this, the curriculum proposal has been the object of technical, curricular and pedagogical attention to curriculum development, understood as a process of decision-making and curriculum construction, which necessarily involves the conception, implementation, and procedural evaluation (Antonio & Rodrigues, 2014).

Therefore, this process of curricular organization did not simply focus on the instructional purposes or formal dimensions of the curriculum, such as the teaching objectives, but contemplated “[…] several aspects of its practice, including the means, the political purposes and pedagogical aspects of school education” (Antonio & Rodrigues, 2014, p. 800).

Based on the memory records of the process of elaborating the Study Complexes, we observed the lucidity on the part of the collective in the coordination and formulation of the curricular organization, not aiming at a curricular transposition (of both the advances and limitations) of the Escola Única do Trabalho from the period 1917-1931, including due to the many differences in conjunctures between semi-feudal Russia at the beginning of the 20th century and present day with the scientific-technological development of the western world and Brazil. In this sense, Ciavatta (2014) corroborates by pointing out that, in the case of education, there is no transposition from one system to another, but there are lessons to be extracted that explain the accumulated experiences and starting points of the process. With regard to socialist pedagogy, the author basically lists three learnings:

[…] first, the relationship between labor and education will continue to be the object of fierce dispute in the capitalist system where we live; second, knowledge of socialist pedagogy preserves memory and builds the history of education for humanization, and not just half-education for exploitation in the service of the market; third, the struggles for a new relationship between labor and education must advance pari passu with other social struggles for the improvement of life for the entire population. (Ciavatta, 2014, p. 191).

In this direction, the exercise that the MST built was to systematically resort to socialist pedagogy in its form of the Escola Única do Trabalho to support reflections, analyzes and curriculum production, seeking to advance the link between labor and education, a fundamental pillar of the practical development of ‘Escola do Trabalho na luta pela terra’ since the end of the 1980s, having as reference the construction of the ‘Pedagogia do Movimento’ in these 35 years.

Thus, there was a deepening of studies about authors of socialist pedagogy and the Marxist conception of education, which allowed the potentialization of dimensions already existing in the MST proposal, in a more integrated and articulated way, such as the construction of teaching planning in connection with life; the exercise of self-organization practices by students seeking horizontality in human relations at school; the conception of education as a process of human formation and as an instrument of struggle; education through work and for work, especially considering socially necessary work (Sapelliet al., 2019).

The cycles of human formation with study complexes in the Itinerant Schools of Paraná

The dimensions of the curriculum organization by Study Complexes precedes the organization by Cycles of Human Formation, which was elaborated in 2005 by the state collective of MST educators of itinerant schools which, after a long process, was authorized to be implemented as an experiment for five years, through the Opinion of the CEE/PR n. 117 of February 11, 2010, and the Resolution n. 3,922/2010 (Sapelli, 2017).

The curriculum organization by Cycles of Human Formation aims to change the spaces, times, relationships, and evaluation processes at school (Paraná, 2009; 2013), challenging to overcome the linearity and fragmentation of knowledge present in the serialization. In this proposition, the Human Formation Cycles are based on the philosophical and pedagogical principles of MST education, sharing a conception of education understood as an omnilateral human formation process, contributing to the development of different human dimensions: affective, intellectual, political, ethics, body, aesthetic, social and organizational, among others (Paraná, 2013).

As a result of this conception of education, the proposal of Human Formation Cycles (Gehrke, 2010; Hammel, & Borges, 2014) already contemplated central curricular dimensions based on the principles of education of the MST, which acquired greater completeness with the incorporation of Study Complexes. The Human Formation Cycles with Study Complexes as a curricular organization reached an elaboration that allowed the systematic conception of the methodological articulation between knowledge, current affairs, self-organization, work and socially necessary work (Sapelli, Leite & Bahniuk, 2019).

The version of the document entitled Study Plan of the Itinerant School Paraná (MST, 2013), the school curriculum, contains the set of didactic-pedagogical-curricular guidelines that orient the educational work in itinerant education, unified in terms of conception and in the organization’s conduction level of school and teaching. It establishes the relationships of knowledge from different subjects with work, social and natural life in a manner consistent with the formative and teaching objectives corresponding to human development in each age group of students (MST, 2013). This document understood that “[…] the clear specification of the contents, its objectives and the successes we expect from our children is a necessary antidote to the tendency to trivialize theory when we get closer to everyday life” (MST, 2013, p. 32).

It is about the curriculum as a nuclear and global reference of the school as a cultural institution (Sacristán, 2000; Antonio & Rodrigues, 2014) that relocates the organization of educational work, in an articulated way, arranged to the conception of education, human development, society. The pedagogical matrices, the educational times, the goals of education, the specific methods and times, the bases of science and art (teaching goals) and training, contemplating the collective organization with students' self-organization, aspects of reality, socially necessary work and educational sources (MST, 2013).

The Study Plan is not exclusively about methodological guidelines for the educator, but announces and indicates the necessary change in the content and form of the school, “[…] a new form of organization of school work that allows the development of students with capacity of self-organization, aware of their time, aware of their commitments in an increasingly complex world” (MST, 2013, p. 09). In this perspective, it assumes, as a fundamental formative matrix, the necessary relationship and bond between school and life.

The linking of educational work with the complex world of labor acquires pedagogical intentionality through the connection with the pedagogical matrices of the ‘Pedagogia do Movimento’.

This pedagogy grounds and reaffirms a conception of education, of human formation, which is not hegemonic in the history of thought or theories about education, and which is also not at the basis of the constitution of the school institution: it is a historically-based conception, materialist and dialectic, for which it is necessary to consider centrally the conditions of social existence in which each human being is formed […]. (MST, 2013, p. 12).

Thus, the key to the link between school and life are the pedagogical matrices - of work, social struggle, collective organization, history, and culture (MST, 2013) -, which does not mean restricting educational work circumscribed to immediate life. Having pedagogical matrices as the basis of educational work means taking them as an organizing reference of the educational environment in relation to universal culture, having labor, assumed as an ontological and ethical-political presupposition of human sociability, as a fundamental educational principle of this curricular orientation.

Therefore, the Itinerant School curriculum faces the challenge of making itself, of materializing curricular practices that seek to understand and train the human in its entirety. The Study Complexes, as a curricular unit, preserve the specificity of work with knowledge. As stated, the curriculum is integrated by a complexity that triggers the need for the use and appropriation of concepts, categories, and procedures from the various sciences and arts to expose the contradictions in social practice (MST, 2013). “It is the stage for a theoretical-practical exercise that requires the student to have the conceptual bases for their understanding, allowing the creation of situations for the practical exercise of these bases, full of meaning and challenges […]” (MST, 2013, p. 31).

This proposition has as its philosophical and pedagogical basis the historical-dialectical materialism, and aims to provide students with the opportunity to progressively appropriate this worldview. It incorporates this method focused on the investigation of human work in its relations with the social totality. The study complex articulates,

[…] always, in the same proposition, material work as a general method (sometimes as a link with productive work, sometimes as a broader social practice - but always as socially useful work), the bases of science and arts (classically called teaching content, or the knowledge historically accumulated by humanity that can be addressed in that grade and age of the child, in the form of teaching content and objectives), the development processes of self-organization inserted in its training objectives, as well as the specific methods of domain of the disciplines involved in the complex, which make use of numerous educational sources in the environment where the student lives (MST, 2013, p. 32).

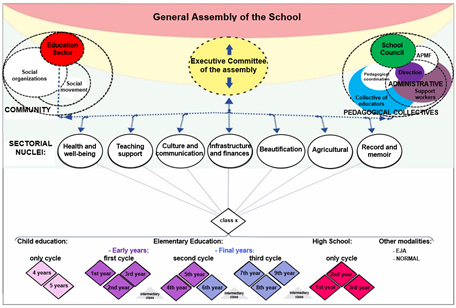

The outline of the curricular dimensions that integrate the new organization of the political-pedagogical proposal, based on this process, explained in Leite & Sapelli (2019), presents curricular dimensions of the Human Formation Cycle with Study Complexes. The circular scheme brings together the set of elements that make up the Human Formation Cycles with Study Complexes, organized into a common part and a differentiated part, the common part comprising the objectives with education in the whole of school work.

The differentiated part represents the Study Complexes as multifaceted curricular units, integrated by the intentional articulation of the bases of science and arts with their specific methods for the study and development of social work and the self-organization of students who move from a given portion of reality (MST, 2013). “Each of these curricular units brings elements from different disciplines, therefore, the proposal preserves the specificity of their field of study, but also proposes a methodology to break with the fragmentation of knowledge, based on understanding of reality” (Sapelli, 2013, p. 246).

Differently from the curricular orientation by generating themes that guide the learning of the contents, initially through questions related to the problems of reality, in this proposition it is the school contents, the teaching objectives and the training objectives, defined in the Study Plan, that guide the educational work and engage with the portion of reality. In the curricular unit, knowledge and educational times are moved and articulated by the portion of reality that integrates the complex, whether by the dimension of study, work, school management and its relationship with self-organization (MST, 2013). The portions of reality are defined from ethnographic research, carried out collectively by the school, organized in the process of inventorying reality with surveys and records of material or immaterial aspects of a given reality.

By portion of reality, also called the category of practice, it is understood aspects of social practice - expression of work in society and nature - that, to some extent, determine social life, becoming full of meaning to exercise knowledge in the relationship with ‘human work’ and to raise students' understanding of the world based on the different dimensions of educational work. They are dimensions of social practice that express multiple determinations/unit of the diverse and that require integrative approaches from the various disciplines to provide students with an understanding of the totality of the relationships that determine it, with their proper nexuses, with universal culture (Leite, 2017), moving interdisciplinarity through social practice (study of human work expressed through the portion of reality) (MST, 2013).

The curricular dimension of the ‘Political organization of the school’, which integrates democratic management, indicates the change in the logic of power in the school through horizontal relations between the different subjects of the school, understanding that the school is a set of relationships (Shulgin, 2013), in such a way that students can intentionally insert themselves in these relationships, experience decision-making and opinions concerning school life, consider the norms, laws, and provisions in force, favoring the exercise of the organizational condition through real accountability processes, shared between different segments of the school (school administration, community, and students) (MST, 2013).

In this way, the different pedagogical matrices are set in motion in articulation in this school form, working on the different dimensions of human formation, whose organicity can thus be evidenced in the Figure 1.

From the illustration (Figure 1), we observe that, from top to bottom, there is the first higher instance of the school: the School Assembly, precisely because it is composed of all the subjects of the school, and which, necessarily, meets at the beginning and end of every semester. This management environment must be understood as the highest level, as it brings together

[…] the participation of everyone involved with the school, and that includes the entire community. Therefore, the organization and execution of the assembly must be preceded by specific principles and rules for the moment, and preceded by its preparation by the executive committee (MST, 2013, p. 24).

Below, the second instance is the executive committee of the assembly, which is made up of leaders from the different segments of the school: students (sector nuclei), school administration (educators, management), and the community. The third instance is composed of sectoral nuclei, defined by schools, based on the aspects and dimensions that social life directs, while relevant to constitute itself as an object of study and work at spe

Figure 1 Outline of the proposal of students’ self-organization in the political organization of the Itinerant School (MST, 2013, p. 25).

cific times, a factor that requires expansion of school time as elucidated by the Study Plan (MST, 2013).

The compositions of the sectorial nuclei are carried out by different age groups, as indicated in the illustration at the bottom, however the definition of these compositions is intrinsic to the strategies constituted by each school. The need to appreciate the rotation of leaders of the cores periodically/biyearly is highlighted to allow a greater number of students to participate in the experience of being led and also leading the semiannual rotation of students in different sectoral nuclei to exercise responsibilities for through different forms of work and appropriating greater knowledge related to the nature of the work object of each nucleus (MST, 2013).

This organization aims to trigger dimensions of student education in at least three aspects: first, it concerns democratic management and systematic insertion in the political participation of school life, contributing to decision-making and the direction of the school; second, the environment in which collective organization is exercised based on the specific work object of the sectorial nucleus; and third, the appropriation of the scientific foundations of the work object exercised or to be exercised, which may be related to the school contents of the age group or beyond, depending on the demands of the work developed by the sectorial nucleus.

The curricular dimension of ‘Socially Necessary Work - TSN’ (Shulgin, 2013) must necessarily be linked to the dimension of knowledge and self-organization of students, materializing the school’s bonds with social practice in the struggle for land and in the production of life, through organizational, political, economic and cultural processes. Fundamentally, the TSN needs to achieve social impact, intervention in improving the quality of life in its different spheres (it takes place outside the school, but it is intentionally based on it) and undoubtedly must contain its pedagogical value for elevation in the domain of the foundations of science and of art and in the constitution of new relationships, therefore, in line with the students’ physical strengths (Shulgin, 2013; Sapelli, Leite & Bahniuk, 2019).

Thus, it is not restricted to school work, nor is it just a matter of defending the unification between work and education, but how, in struggle, it will favor the youth in their midst, to intervene, in a novel and creative way, in the situations experienced, because it is not enough to be physically present in the fight, it is essential to understand the determinations that involve it nowadays and to know how to act in the contradictions (Pistrak, 2009; Shulgin, 2013; MST, 2013).

From this perspective, the search for effective links between science and production in the Itinerant School, within its limits, has challenged school groups to exercise and make the camp a stage for initiatives that place the relationship with more complex forms of work on the horizon. Among the initiatives, we highlight: construction of mandala gardens; preservation of mines and water sources; water reuse process; management of ornamental mandala of medicinal plants, spices and flowers, aromatics and condiments; construction of orchard-forest; agroforestry; soil recovery; ecosystem management; orchard; production of seedlings and others, as recorded in the Diário de Campo of May 31, 2016, during the Training of Educators at the MST-PR Itinerant Schools, Quedas do Iguaçu, Paraná.

In the curriculum guidance of the Study Plan, school times are distributed by Tempos Educativos that aim to organize the educational environment beyond the classroom, with spaces, times, and relationships in the entirety of the school, in interaction with reality, with its challenges and the contradictions of its historical time. They provide opportunities to move the different dimensions of the human being to enhance the appropriation of knowledge and elevate the human condition through workshops, social work, in addition to individual and collective organization, the experience of mysticism, the taste for literature and art (MST, 2013).

The ‘Graduation Time’ corresponds to the initial moment of the school shift, involves all the subjects of the school, when mystics and reports are made; ‘Labor Time’, established through a social division of labor, aims to meet the demands of the school community, but with a pedagogical function; ‘Reading Time’ is intended for reading different discursive genres with the intention of contributing to the development of taste and reading habits; ‘Written Reflection Time’, daily time aimed at producing a small reflection on what is experienced during the school day; ‘Culture Time’, a moment aimed at cultivating diverse cultural expressions, such as, for example, a movie session, theater presentations, among others; ‘Class Time’, intended for the development, by school subjects, of their contents, establishing the link with life, through complexes; ‘Study Time’, aimed at the students’ studies, individually or collectively, to carry out research and other work from the disciplines, sectorial nuclei, also includes ethnographic studies on the region; ‘Workshop Time’, corresponds to activities aimed at the apprehension of cooperation, of manual, cognitive, cultural skills; ‘News Time’, aimed at following up on news and debates on information obtained, organized by the sectorial nucleus of communication; ‘Sectorial Nuclei Time’, intended for the organization and planning of the nuclei as well as the carrying out of activities competent to them; ‘Educators’ Time’, a space for the study, assessment, and planning of educators, seeking collective ways of experiencing this space (MST, 2013).

Final considerations

The expropriation of land, the concentration of the means of production and the expulsion of thousands of people from the countryside, who were left without basic living conditions, led to the organization of the Landless Rural Workers Movement, the MST, through which communities and families organize themselves to search for survival spaces - with the Agrarian Reform - where they can produce sustainability, express their knowledge about the cultivation of the land and the production of healthy foods, as well as reproduce and disseminate humanized ways of preserving the environment and life in society. In this organization, the school, access to knowledge, and learning for all plays a central role.

In times of expansion of the capital’s offensive on social rights, the regression in relation to the hard conquests of the working class is aggravated, with an ongoing systematic attack on public education by business organizations that materialize setbacks in educational policy characterized by the emptying of scientific content, by conservatism and intolerance with the antagonistic views of the world expressed by neoliberal curricular policies such as the current proposal for High School, the Escola Sem Partido Project (Frigotto, 2017) and the Common National Curriculum Basis.

The curricular organization of the MST, in exercise in the Itinerant Schools of Paraná, contributes to constitute pillars of resistance and compose the curricular debate in overcoming standardization. The way of organizing the school by Cycles of Human Formation with Study Complexes values local knowledge, contributes to the production of sustainability in the field, strengthens autonomy, questions and attempts to overcome the fragmentation of human formation imposed by conventional and hegemonic forms of curriculum linked to the logic of market society.

The constitution of educational times, in addition to the classically known class between four walls, challenges education to provide an increase in the level of knowledge of students in relation to labor and its contradictions through the use of concepts, categories, and procedures of the different sciences and arts that are the object of study, in conjunction with the set of curricular dimensions, effecting scopes of structuring amplitude for curricular practice that transcend bookish and verbal teaching, for example, through socially necessary work practices, students’ self-organization and the connection of knowledge to portions of reality.

Equally, in a continuous effort, the Itinerant School puts itself in the exercise of materializing the Human Formation Cycles with Study Complexes, offering conditions to students, as well as to the community in which they belong, so that they effectively constitute themselves as subjects in their learning and driving process. The link between school and life stands out as a primordial formative matrix, which, in connection with other pedagogical matrices, offers materiality to the ‘Pedagogia do Movimento’ (MST, 2013).

In the confrontations with a view to the production of curricular practices against hegemonic ones, the need to develop processes of continuing education of educators is evident, which, with actions consistent with the fundamentals of the assumed school practice, trigger the formation of educator-subjects with the condition to think and make an educational process coherent with what is intended.

That in the experiences, proposals, and challenges of a school built on itinerancy and struggle for land, this school continues to reaffirm the commitment to be one that overcomes, or at least confronts, the order given in a hegemonic way, questioning and opposing effectively the crystallization of the serialization as the founding basis of the contemporary school.

Since the origin of the Itinerant School, the MST and its families have ensured its continuity, through demands, negotiations, mobilizations in the Jornadas de Lutas that encourage the state government to create conditions for the maintenance of this school, knowing that the struggle for humanization permeates the access to scientific knowledge and is a condition for building the Popular Agrarian Reform.

The Itinerant School has highlighted the possibility of building the school against hegemonic working class within the current contradictions, reaffirming that this is a task of the working class in the present (Grein, 2019). It is a school in the midst of contradictions that aims to permanently respond to the educational aspirations of the working class in the formation of fighters of the present and builders of values and embryos of the socialist society.

REFERENCES

Antônio, C. A., & Rodrigues, C. L. S. (2014). Complexos de Estudos: experimento de currículo nas escolas do MST no Paraná, Brasil. In Anais do XI Colóquio sobre Questões Curriculares (p. 798-802). Braga, PT: Universidade do Minho. [ Links ]

Caldart, R. S. (2012). Pedagogia do Movimento. In R. S. Caldart, I. B. Pereira, P. Alentejano & G. Frigotto (Orgs), Dicionário da Educação do Campo (p. 546-555). São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular. [ Links ]

Ciavatta, M. (2014). O ensino integrado, a politecnia e a educação omnilateral. Por que lutamos? Trabalho & Educação, 23(1), 187-205. [ Links ]

Dalmagro, S. L. (2010). A escola no contexto das lutas do MST (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis. [ Links ]

Frigotto, G. (2017). Escola “sem” partido: esfinge que ameaça a educação e a sociedade brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: UERJ, LPP. [ Links ]

Gehrke, M. (2010). Escola itinerante e a organicidade nos ciclos de formação humana. Analecta, 11(1), 99-113. Recuperado de https://revistas.unicentro.br/index.php/analecta/article/view/2296 [ Links ]

Grein, M. I. (2019). Prefácio. In M. L. S. Sapelli, V. J. Leite, & C. Bahniuk, ensaios da escola do trabalho na luta pela terra: 15 anos da Escola Itinerante no Paraná. São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular . [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira [INEP]. (2000). Mapa do Analfabetismo no Brasil. Recuperado de http://portal.inep.gov.br/informacao-da-publicacao/-/asset_publisher/6JYIsGMAMkW1/document/id/6978610 [ Links ]

Hammel, A. C., & Borges, L. F. (2014). Ciclos de formação humana no Colégio Estadual do Campo Iraci Salete Strozak. Revista HISTEDBR, 14(59), 251-271. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20396/rho.v14i59.8640361 [ Links ]

Ianni, O. (1984). Origens agrárias do Estado brasileiro. São Paulo, SP: Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Kolling, E., Vargas, M. C., & Caldart, R. S. (2012). MST e Educação. In R. S. Caldart, I. B. Pereira, P. Alentejano & G. Frigotto (Org.), Dicionário da Educação do Campo (p. 500-508) São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular . [ Links ]

Leite, V. J. (2017). Educação do campo e ensaios da escola do trabalho: a materialização do trabalho como princípio educativo na escola itinerante do MST Paraná (Dissertação Mestrado). Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná, Cascavel. [ Links ]

Leite, V. J., & Sapelli, M. S. (2019). Complexos de estudo. In C. Bahniuk & R. S. Caldart (Org.), Dicionário Agroecologia e Educação. São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular . [ Links ]

Morissawa, M. (2001). A História da luta pela terra e o MST. São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular . [ Links ]

MST. (1989). Memória. Jornal Sem Terra, Ano IX, n. 82, abril, p. 20. [ Links ]

MST. (1991). O que queremos com as escolas dos assentamentos (Caderno de Formação, nº 18). São Paulo, SP. [ Links ]

MST. (2005). Dossiê MST Escola: Documentos e Estudos 1990-2001. Veranópolis, RS: ITERRA. [ Links ]

MST. (2006). Educação básica de nível médio nas áreas de reforma agrária (Boletim da Educação, nº 11). São Paulo, SP: ITERRA [ Links ]

MST. (2013). Plano de Estudos da Escola Itinerante. Cascavel, PR: Editora Unioeste. [ Links ]

MST. (2017). Educação no MST e memória - Documentos 1987-2015 (Caderno de Educação, nº 14). São Paulo, SP: Editora Expressão Popular. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. (2013). Projeto Político-Pedagógico do Colégio Estadual do Campo Iraci Salete Strozak e das Escolas Itinerantes. Rio Bonito do Iguaçu, PR: CECISS. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. (2009). Projeto Político-Pedagógico do Colégio Estadual do Campo Iraci Salete Strozak e das Escolas Itinerantes . Rio Bonito do Iguaçu, PR: CECISS . [ Links ]

PARANÁ. (2010). Parecer CEE/CEB nº 117/10 - 11 de fevereiro de 2010. Pedido de implantação de Proposta Pedagógica do Ciclo de Formação Humana para o Ensino Fundamental e Médio, com acompanhamento de classes intermediárias na Escola Base das Escolas Itinerantes. Recuperado em 10 jan. 2019 de http://www.educadores.diaadia.pr.gov.br/modules/conteudo/conteudo.php?conteudo=564 [ Links ]

PARANÁ. (2010). Resolução SEED-PR nº 3922/10 - 13 de setembro de 2010. Autoriza a implantação da Proposta Pedagógica do Ciclo de Formação Humana. Diário Oficial, n. 8331 de 26 de Outubro de 2010. Recuperado em 10 jan. 2019 de https://www.legislacao.pr.gov.br/legislacao/pesquisarAto.do?action=exibir&codAto=69381&indice=1&totalRegistros=1 [ Links ]

Pistrak, M. (2009). A Escola Comuna. São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular . [ Links ]

Sacristán, J. G. (2000). O currículo: uma reflexão sobre a prática. Porto Alegre, RS: ArtMed. [ Links ]

Sapelli, M. L. S. (2013). Escola do campo - espaço de disputa e de contradição: analise da proposta pedagógica das escolas itinerantes do Paraná e do Colégio Imperatriz Dona Leopoldina (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis. [ Links ]

Sapelli, M. L. S. (2017). Ciclos de formação humana com complexos de estudo nas escolas itinerantes do Paraná. Educação & Sociedad, 38, 611-629. [ Links ]

Sapelli, M. L. S., Leite, V. J., & Bahniuk, C. (2019). ensaios da escola do trabalho na luta pela terra: 15 anos da Escola Itinerante no Paraná . São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular . [ Links ]

Shulgin, V. (2013). Rumo ao politecnismo. São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular . [ Links ]

8Note: Valter de Jesus Leite: conception, survey of empirical data, planning, and writing. Rosângela Célia Faustino: conception, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing, approval of the final version to be published; Maria Simone Jacomini Novak: writing and critical review of the content, approval of the final version to be published;

Received: December 10, 2019; Accepted: April 27, 2020

texto en

texto en