Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Acta Scientiarum. Education

Print version ISSN 2178-5198On-line version ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.44 Maringá 2022 Epub Aug 01, 2022

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v44i1.61857

HISTÓRY AND PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION

Mapping the debate on the teaching of sociology in Brazil: an analysis of the themes and agents present in the Eneseb WGs (2013-2021)

1Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Rua Eng. Agronômico Andrei Cristian Ferreira, s/n, 88040-900, Trindade, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brasil.

The National Meeting on Teaching Sociology in Basic Education, an organized by the Teaching Commission of the Brazilian Society of Sociology, has been established as the main event in the field of Teaching Sociology in Brazil, bringing together researchers and teachers. In this work, I seek to analyze the main themes and agents (Working Groups coordinators) in this academic event, mapping this debate from the Working Groups (2013-2021). The data point to the existence of a research agenda that has been consolidated, showing relative autonomy about the broader field of Sociology, and also the existence of agents who tend to lead the debate, with such agents being found mainly in peripheral institutions in the field of Brazilian Sociology. Both in the analysis of the themes and of the agents, we can observe that the field of Teaching Sociology in Brazil is becoming autonomous.

Keywords: teaching sociology; Eneseb; Brazilian Society of Sociology

O Encontro Nacional de Ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica, organizado pela Comissão de Ensino da Sociedade Brasileira de Sociologia, tem se constituído como o principal evento na área de Ensino de Sociologia no Brasil, agregando pesquisadores e professores. Neste trabalho, buscou-se analisar as principais temáticas e agentes (coordenadores de Grupos de Trabalhos) nesse evento acadêmico, mapeando o debate a partir dos Grupos de Trabalho (2013-2021). Os dados apontaram para a existência de uma agenda de pesquisa que tem se consolidado, apresentando uma relativa autonomia em relação ao campo mais amplo da Sociologia, e também para a existência de agentes que tendem a capitanear o debate, encontrados principalmente em instituições periféricas no campo da Sociologia brasileira. Tanto na análise das temáticas quanto na análise dos agentes foi possível observar que o campo do Ensino de Sociologia no Brasil está em processo de autonomização.

Palavras-chave: ensino de Sociologia; Eneseb; Sociedade Brasileira de Sociologia

El Encuentro Nacional de Enseñanza de la Sociología en la Educación Básica, organizado por la Comisión de Enseñanza de la Sociedad Brasileña de Sociología, se ha convertido en el principal evento en el campo de la Enseñanza de la Sociología en Brasil, reuniendo a investigadores y docentes. En este trabajo buscamos analizar los principales temas y agentes (Coordinadores de Grupos de Trabajo) en este evento académico, mapeando el debate desde los Grupos de Trabajo (2013-2021). Los datos apuntaron a la existencia de una agenda de investigación que se ha consolidado, presentando una relativa autonomía en relación al campo más amplio de la Sociología, y también a la existencia de agentes que tienden a conducir el debate, que se encuentran principalmente en instituciones periféricas en el campo. de Sociología Brasileña. Tanto en el análisis de los temas como en el análisis de los agentes, fue posible observar que el campo de la Enseñanza de la Sociología en Brasil está en proceso de autonomía.

Palabras clave: enseñanza de la sociología; Eneseb; Sociedad Brasileña de Sociología

Introduction

The debate on Sociology teaching in Brazil has been consolidated as a research topic on the Brazilian Social Sciences agenda. However, it remains a relatively peripheral place in this field and can be interpreted as a subfield or even a field in a growing process of autonomization. In this scenario, one of the main spaces for legitimizing this debate has been the National Meetings on the Teaching of Sociology in Basic Education (Encontro Nacional de Ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica - Eneseb), promoted by the Brazilian Society of Sociology (Sociedade Brasileira de Sociologia - SBS) biannually since 2009.

We understand that there are also other spaces of legitimation in this field, which permeate the Working Group (WG) on Teaching Sociology, present at the Brazilian Congress of Sociology (Congresso Brasileiro de Sociologia - CBS) and the SBS teaching commission. The Brazilian Association for the Teaching of Social Sciences (Associação Brasileira de Ensino de Ciências Sociais - ABECS)12, which also promotes its national meetings, and other events in the area of Education and Social Sciences, can be added to this list13. However, given the strong link with the primary national scientific association in the field of Sociology, we can say that Eneseb constitutes a central locus for understanding the dynamics inherent to the national debate on the subject.

To contribute to this debate, in this article, we will assess the discussions held at Eneseb, using the themes of the WGs as a guideline. This activity became part of the event’s programming from the third edition onwards. We will seek to observe which agents are involved in elaborating this agenda - with a focus on the coordinators of the WGs - and the changes and permanence of the debate over the last editions. To carry out this analysis, we will mainly use the collections published in Eneseb editions (Gonçalves, 2015; Gonçalves, Mocellin, Meirelles, 2016; Caruso & Santos, 2019; Oliveira, Engerroffo, Greinert, & Cigales, 2021), in which the balances of the WGs carried out by the coordinators are included, in addition to the 7th Eneseb’s schedule, considering that there is still no publication referring to this edition of the event.

To better contextualize the reader, we will organize the article into three sections: a) in the first, we will present how the debate on the Sociology teaching has been placed within the CBS, including the formation of the WG dedicated to this theme; b) in the second, we will make a brief presentation of Eneseb, contextualizing the editions carried out so far; c) finally, we will map the agents and the debates that have been promoted in this space.

Teaching Sociology at CBS

The CBS took place for the first time in 1954, in São Paulo, chaired by Fernando de Azevedo (1894-1974), and with the theme ‘Teaching and sociological research; social organization; social change’. This theme points to the relevance of the discussion about teaching at that moment. Because Sociology had been absent from school curricula since 194214 and Social Science courses were still being consolidated, there were only 11 undergraduate courses in Social Sciences (Liedke Filho, 2005). Therefore, we can infer that the more general objective of this event’s theme would be to discuss the challenges of teaching Sociology in higher education.

It is also important to mention that in this period, there was an intensification of the debate in the field of Social Sciences in Latin America as a whole, which also unfolded in a discussion about the formation of sociologists and their teaching. A year before CBS, Brazil had hosted the Latin American Sociological Congress, which took place in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo and was chaired by Manuel Diegues Júnior (1912-1991). Still within the scope of Social Sciences, also in 1953, in Rio de Janeiro, the 1st Brazilian Meeting of Anthropology (RBA) took place.

In 1956, the I South American Seminar for the University Teaching of Social Sciences took place in Rio de Janeiro, followed by the foundation, in 1957, also in Rio de Janeiro, of the Latin American Center for Research in the Social Sciences and the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences, in Santiago, Chile. Such institutions constituted privileged spaces for the training and circulation of researchers in Latin America, being significant milestones for the institutionalization of Social Sciences in the region (Beigel, 2009; Lippe Oliveira, 2005).

We observe that, far from representing a specific action, the CBS was inserted into a broader spectrum of the institutionalization process of Brazilian Social Sciences. In this sense, attention is drawn to the fact that one of the central themes at that time was the Sociology teaching. There were 12 general thematic lines at that congress, in which communications and exhibitions were organized, structured as follows:

I - Teaching and sociological research. 1 - The teaching of sociology and related disciplines in the different cultural centers of the country; 2 - Sociological and anthropological research in Brazil; 3 - The national statistical system - its use as a source of sociological data; 4 - The contribution of Sociology for solving social problems. II - Social organization. 1 - Structure of the Indigenous community (Indigenous, rural, urban, rural-urban); 2 - General and specific systems (family and kinship, economic, political, legal, pedagogical, etc.); 3 - Ethnic relations. III - Social change. 1 - Internal and foreign migratory flows; 2 - The impact of economic development on the social structure of less developed countries; 3 - Technical transformations and social changes; 4 - Effects of urbanization and stratification on Brazil’s social stratification; 5 - Social changes and problems (Brazilian Society of Sociology, 1955, p. 13).

Far from appearing as a secondary concern, Teaching was a central axis in the debate of the first Brazilian congresses of Sociology. Amid this discussion, Florestan Fernandes (1920-1995) presented his communication, The Sociology Teaching in Brazilian Secondary Schools, which not only indicated the potential of the Sociology teaching but also pointed out some obstacles to its effectiveness (Fernandes, 1980).

It is essential to realize that effectively the discussions in the first CBS, even in those carried out in the period after the re-democratization, were more focused on Sociology Teaching in higher education in the context of sociologist training. Therefore, we can understand that the Sociology teaching was interpreted as relevant in the institutionalization of Sociology in higher education. Still, in primary education, it remained a secondary issue. In part, it reflected the fact that Sociology as a subject was not present in the school curriculum at that time and that, strictly speaking, degrees in Social Sciences predominantly formed teachers who taught other school subjects, such as History, Geography, and, from the 1960s, Brazilian Social and Political Organization (Organização Social e Política do Brasil - OSPB).

Effectively, there has been a change in this area since the 2000s, a period in which we can observe an acceleration of the gradual reintroduction of Sociology in state curricula (Bodart, Azevero, & Tavares, 2020). The direct reflection of this movement at the academic level was the creation, in 2005, of a WG focused on the debate on Sociology Teaching together with the CBS - this group became one of the main spaces for articulation of researchers dedicated to the topic in Brazilian Sociology15. One of the leading articulators of this group since its foundation was Amaury Cesar de Moraes, a professor at the University of São Paulo (Universidade de São Paulo - USP), who coordinated it between 2005 and 2013. Other researchers also played a prominent role in coordinating, such as professors Ileizi Silva from the State University of Londrina (Universidade Estadual de Londrina - UEL), Anita Handfas from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Universidade Federeal do Ripo de Janeiro - UFRJ), and Danyelle Ninlin Gonçalves from the Federal University of Ceará (Universidade Fedederal do Ceará - UFC). Concurrent with the WG creation, the Sociology Teaching Commission was also founded, initially coordinated by Professor Heloísa Martins, also from USP.

While these actions took place within the scope of the SBS, there were several other initiatives whose main stage was curriculum disputes. In 2006, the Curriculum Guidelines for High School were published, written by Amaury Cesar de Moraes, Nelson Tomazi, professor at UEL, and Elizabeth Guimarães, professor at the Federal University of Uberlândia (Universidade Federal de Uberlândia - UFU). This document played a decisive role in the disciplinary delimitation of Sociology in the school curriculum. In the same year, Opinion CNE/CBE No. 38/2006 was approved on the mandatory inclusion of Sociology and Philosophy subjects in high school. And in 2008, Law No. 11,684 (2008) was approved, which made teaching Sociology and Philosophy mandatory in all high school grades16.

This summary about the path of Sociology in the school curriculum and the SBS aims to situate the reader about some transformations that occurred both in the field of Sociology and in other fields and that directly impacted the process of constitution and empowerment of the subfield of Sociology Teaching. This process framed the emergence of Eneseb, which is consolidated today as the main academic event in the field of Sociology Teaching.

Eneseb and the consolidation of the theme of Sociology Teaching

As observed in the previous section, a set of academic actions within the scope of educational policies enabled the consolidation of Sociology Teaching as an object of reflection in the Social Sciences. Several assessments carried out in recent years, mainly involving the production of theses and dissertations, as well as the publication of articles in specialized journals, have confirmed this trend (Bodart & Cigales, 2017; Bodart & Souza, 2017; Brunetta & Cigales, 2018; Caregnato & Cordeiro, 2014; Handfas, 2011; Handfas & Carvalho, 2019; Handfas & Maçaira, 2012), although we can also say that this theme has not been consolidated as central in the field of Sociology, as we can see from the absence of specific lines of research in postgraduate programs in the area. Amid this consolidation process, Eneseb has constituted an essential space for legitimizing the theme and solidifying a subfield in the process of becoming autonomous.

It is essential to realize that several institutional factors made its existence possible when the first edition of Eneseb took place in 2009. On the one hand, within the scope of educational policies, legislation that made the Sociology Teaching mandatory in all Brazilian secondary education had been approved; on the other hand, in the academic field, the creation of the WG and the Commission at the SBS, focused explicitly on this debate, legitimized the existence of an academic discussion within the scope of Brazilian Sociology on this topic.

The SBS Teaching Committee is the official event organizer and tends to hold it on the days before the CBS, generally in the same city17. We also observed that the event concentrated most of its activities on weekends, making it more inclusive, especially for primary education teachers, who can participate in the event even if they do not have the release of teaching activities from their respective jobs18.

The first edition of Eneseb took place in Rio de Janeiro, based at the Faculty of Education at UFRJ. The event featured an opening conference, given by French sociologist François Dubet, as well as two round tables, five Discussion Groups (DG), and four pedagogical workshops.

It is essential to mention that in 2008 the State Meeting of Sociology Teaching (Encontro Estadual de Ensino de Sociologia - Ensoc) of the state of Rio de Janeiro took place, thus enabling an accumulation of experience in organizing and articulating a specific event focused on the Teaching of Sociology. Regarding the realization of this first edition, Handfas (2021, p. 28) indicates the following:

The holding of the 1st Eneseb attested to the importance of creating a space for discussions and practices on teaching Sociology in primary education. The more expressive and active presence of teachers of primary education, in addition to undergraduates and researchers, significantly boosted the debates and enabled the exchange of pedagogical experiences. The themes of the roundtables, the DGs, and the pedagogical workshops that took place at the event allowed us to locate the state of the art of knowledge on the topic that we had accumulated until that moment, which, as we see, was strongly marked by the problem of didactic mediation of sociological knowledge and the training of sociology teachers.

We note that in addition to the existence of conferences and roundtables, Eneseb has two activities that do not exist at CBS: DGs and pedagogical workshops. DGs differ from WGs in that their organization into thematic axes occurs after the approval of the works, unlike the WGs, which receive works based on a specific theme; Eneseb organized the oral communications received in DGs until its second edition. Pedagogical workshops, on the other hand, are designed for teaching practice in Sociology, focusing mainly on teachers who are working in the classroom and in training.

The second edition of Eneseb took place in 2011 in Curitiba, based at the Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná (Pontificia Universidade Católica do Paraná - PUC-PR), while the CBS was based at the Federal University of Paraná (Universidade Federal do Paraná - UFPR). The event took advantage of the structure present in the previous event, with the opening lecture given by Professor Heloísa Dupas Penteado (USP).

The 3rd Eneseb took place in 2013, in Fortaleza, headquartered at the Federal University of Ceará. This was the first time the event took place in a city other than CBS, which was hosted at the Federal University of Bahia (Universidade Federal da Bahia - UFBA) in Salvador that year. The two events also took place with a greater temporal distance, as Eneseb took place between May 31 and June 3 and CBS between September 10 and 13. In this edition of Eneseb, the opening lecture was given by Bernard Lahire. He could not attend due to a personal unforeseen, having sent his text for reading, which was later published. This edition was especially significant as far as two changes took place: a) the works presented began to be organized around WGs, with a public call for proposals by the groups and, only then, for the submission of works in the approved groups; b) a tradition of organizing a collection resulting from the event was inaugurated, in which the coordinators of the WGs carry out a balance of the discussions that took place in their groups.

The 4th Eneseb took place in São Leopoldo, at the University of Vale do Rio dos Sinos (Universidade do Vale dos Sinos - Unisinos), while the CBS took place in Porto Alegre, at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul - UFRGS). The opening lecture was given by Luiza Helena Pereira (UFRGS), maintaining the structure of the previous event. The fifth edition of Eneseb took place at the University of Brasília, the same institution that hosted the CBS, with an opening lecture by professor Ileizi Fiorelli Silva (UEL).

Despite a basic structure practically unchanged since the 3rd Eneseb, at the 6th Eneseb, held at the Federal University of Santa Catarina (Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina - UFSC) - the same institution as the CBS headquarters -, it was decided to hold an opening table instead of a conference, counting with a higher education teacher, a primary education teacher, and a degree student, respectively: Haydée Caruso (Universidade de Brasília - University of Brasília), Ana Carolina Torres (Secretary of Education of the State of Ceará/Professional Master’s in Sociology in the National Network, ProfSocio), and Naomi Neri (UFSC).

The 7th Eneseb took place online due to the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as CBS, both organized by the Federal University of Pará. Luiz Henrique Eloy Amado Terena gave the opening lecture, a Terena Indigenous from Aldeia Ipegue (MS) who, at that time, was doing a post-doctoral internship in Anthropology at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris.

It is important to note that in addition to the national meetings, numerous state and regional meetings have focused on the debate on the Sociology teaching. In addition to Ensoc, already mentioned, we can highlight as examples the meeting of the Institutional Scholarship Program for Teaching Initiation (Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação à Docência - Pibid) of Social Sciences of the Southern Region, the Symposium for the Training of Teachers of Sociology of Paraná, the Regional Meeting of Education in Minas Gerais of Social Sciences, among others.

In the evaluations carried out on the event, its relevance in socialization and sharing pedagogical experiences among teachers from different parts of the country is reaffirmed. As Gonçalves (2015, p. 314) highlights:

During these years, the meeting brought professionals from primary education, higher education, and undergraduate students from all regions of the country into more excellent contact. As it is a national event, it has already been held in the Southeast on one occasion (Rio de Janeiro, in 2009), in the South, on two occasions (in 2011, in Paraná and Rio Grande do Sul, in 2015) in the Northeast ( in 2013), the next being in the Midwest (in the DF, in 2017). Although participants from the North are the minority in these events, all regions have already been represented in the editions. Likewise, it is characterized by the plurality of participants (graduate students, primary education, and higher education professionals are the majority), with the participation of these three groups being encouraged at all stages of the event: from its conception and preparation to its realization, in addition to the proposition of pedagogical workshops.

We can thus understand that Eneseb occupies a space not only for consolidating the academic debate around a particular theme but also for continuing education for primary training teachers and for exchanging experiences. In the same direction, it plays a relevant role in complementing the pedagogical and academic training of students studying Social Sciences degrees. As Raizer, Mocelin, and Meirelles (2016) highlight when assessing the IV Eneseb, the event also constitutes a space for socialization and political organization, citing the mobilization with the Ministry of Education (MEC) so that members of the teaching committee of the SBS to integrate the group that was preparing the National Common Curricular Base (Base Nacional Comum Curricular - BNCC).

Throughout its existence as an academic congress, Eneseb also accompanied the increase of a set of institutional devices that reinforced the place of Sociology in high schools, such as the introduction of this discipline in the National Textbook Program (Programa Nacional do Livro Didático - PNLD), in 2011 and the creation of the first professional master’s degree focused on the teaching of Social Sciences, in 201319. Likewise, it followed some setbacks in the field of educational policies, such as the loss of the obligation of Sociology with the 2017 High School Reform and the publication of the final version of the BNCC, which emptied the disciplinary meaning of Sociology in the school curriculum.

Themes of the Eneseb WGs: continuities and ruptures

As we have already indicated, the first two editions of Eneseb did not have WGs, but rather DGs, which had a different organizational structure. However, it is symptomatic that since the first edition, organizational axes have reflected the debate. According to Handfas (2021), in the first edition of Eneseb, there were five DGs: syllabus and teaching methodologies; textbooks and teaching materials; didactic resources: from classic texts to new technologies; teacher training: curricular organization and supervised internship; research: object and instrument of knowledge in elementary school.

At this moment, we are interested, on the one hand, in mapping the themes explored throughout the different editions of Eneseb; on the other hand, we also map the agents who proposed the WGs. At a methodological level, it is essential to emphasize that our analysis is based mainly on publications and not on the proceedings resulting from this event, given the unavailability of consultation. Therefore, our analysis is limited to the WGs that carried out the balance of their activities, which may not include the totality of those that took place in that edition of the event. We will present below four tables that summarize the WGs promoted in each edition (Table 1).

Table 1 WGs at Eneseb (2013-2021).

| WGs III Eneseb | WGs IV Eneseb | WGs V Eneseb | WGs VI Eneseb | WGs VII Eneseb |

| Media, education, and language: new spaces for socialization | Pibid and teacher training in Social Sciences | Current teaching work in Sociology teaching | Youth cultures at school | Teaching Social Sciences/Sociology in the digital world: teaching methodologies in Social Sciences in primary education |

| Social Science Teacher Training | Teaching methodologies and practices in Social Sciences | Perceptions, representations, and situations of violence in the school environment and its social environment | Sociology Teaching and gender and sexuality issues in primary education: practices, reflections, and strategies | Afro-Americanity in Sociology teaching: contributions and crossings in pedagogical practices |

| Teaching knowledge and professional training of the Sociology teacher in primary education | Sociology textbooks | Youth cultures at School | Sociology Teaching in different teaching modalities | Youth cultures at school |

| Sociology Teaching and social intervention | Social Science teacher Training | The teaching of diversity in high school Sociology: strategies for gender education and ethnic-racial relations at school | History of Sociology teaching in Brazil | Curriculum and educational policies: the Sociology teaching against the BNCC |

| Education for diversity: local knowledge and youth protagonism in Sociology teaching | History of Sociology teaching in Brazil | The Sociology teaching in technical schools in Brazil | Sociology textbooks: What do we know so far? State-of-the-art, balances, and comparisons of experiences | Dialogue with the Human Sciences: practical experiences of teacher training and interdisciplinarity |

| For a didactic transposition of Social Science theories: theorizing on teaching practices in Social Sciences | School, youth cultures, and sociability | Social Sciences/Sociology teachers in the digital world: teaching methodologies in Social Sciences in primary education | Sociology teaching and educational policies | Dialogues of traditional, popular, and sociological knowledge in primary education |

| Sociology textbook | Different modalities of Sociology teaching | History of Sociology teaching in Brazil | Sociology teaching and professional and technological education | Sociology Teaching and amazonian studies |

| Sociology teaching and educational policies | Policy in Sociology Teaching: didactic and formative challenge | The Social Sciences textbook: advances and challenges | The digital universe in the space of teaching methodologies of Social Sciences/Sociology in primary education: experiences, gaps, and perspectives | Sociology Teaching in different teaching modalities |

| Youth cultures at school | Sociology teaching and the work category | Sociology Teaching in different teaching modalities | Perceptions, representations, and situations of violence in the school environment and its social environment | Training of teachers and ProfSocio: production of knowledge and teaching practices of Sociology in primary education |

| Sociology in high school: teaching, methodologies, and research | Gender and sexuality: what the Sociology/Social Sciences teaching in primary education have to do with it? | Social Science teacher Training | Public policies and teacher training in Social Sciences: limits and possibilities | History of Sociology teaching in Brazil |

| Pibid and teacher training in Social Sciences: limits and possibilities | The environmental dimension in the Sociology teaching and interdisciplinary experiences | Pibid and teacher education in science: limits and possibilities | Afro-Indigenous relations and the teaching of social sciences in Brazil | Sociology textbooks |

| Contributions of Sociology to research in education | Theories and methods for research on sociology teaching | Relations between curriculum and assessment in Sociology teaching in primary education | The curriculum of Sociology in primary education | |

| The place of research in Sociology teaching | Knowledge of politics in Sociology discipline in high school: contents, methodologies, and teaching resources | Theories and methods in research on sociology teaching | Sociology teaching and scientific practice: research as a didactic tool | |

| Sociology teaching in primary education and active modalities in learning | ||||

| Public policies and teacher training in Social Sciences: limits and possibilities | ||||

| Relations between curriculum and assessment in Sociology teaching in primary education | ||||

| Theories and methods: how to make Sociology teaching a field of research? | ||||

| The teaching of difference in Sociology - how to think about gender and other categories of articulation in the classroom? |

Source: Prepared by the author (2021).

The first fact that stands out is the existence of a relatively stable number of groups throughout the editions (13, 11, 13, 13, 18), with a slight increase in the seventh meeting, which can be partly explained by the fact that it is an online congress, thus enabling broader participation of researchers from different regions of the country.

We could group the most recurrent themes into six categories: a) teacher training; b) teaching resources; c) teaching methodologies; d) research on Sociology teaching; e) curriculum; f) teaching Sociology and diversity. Obviously, this classification has limitations since there are topics that could fall under more than one of these themes.

Some WGs have lasted in all Eneseb editions that have taken place so far. They are: ‘Youth cultures at school’ and ‘Sociology/Social Sciences textbook.’ On the other hand, other WGs are present in at least four editions of the event: ‘History of Sociology teaching in Brazil’ and ‘Sociology Teaching in different teaching modalities.’ In at least three editions, we find a WG on theories and methods for research in the Sociology teaching and the Sociology teaching in the digital world. However, there may be some minor changes in the group’s nomenclature. We observed that the debate on teacher training gains centrality in the event, with recurrently more than one WG focused on this topic, whether in a more generic way or more specifically focused on some educational policy of initial and continuing training, such as Pibid and the ProfSocio. Likewise, the curriculum is highlighted in the debate, with three WGs on the topic throughout the editions, one focused exclusively on the debate on the BNCC.

Also reflecting the expansion of the research agenda on gender and race, as well as on Afro-Indigenous perspectives, there have been, at least since the IV Eneseb, WG that articulated these issues with the Sociology teaching. This movement seems to reflect, at the same time, the consolidation of these debates in the Social Sciences field (Barreto, Rio, Neves, & Santos, 2021; Franch & Nascimento, 2020) and also the emergence of an increasingly plural perspective of Sociology, which begins to perceive the existence of canons beyond the Eurocentric perspective (Connell, 2019).

Thus, a relatively stable agenda is observed, in which the topics discussed in the first DGs of the 1st Eneseb continue to have space while new topics emerge. We can also infer that, despite the lack of specific lines of research aimed at the teaching of Sociology in stricto sensu graduate programs in Brazil20, the diversity of research lines existing in the programs in Social Sciences/Sociology and also in Education - the leading training spaces for researchers in the area - tends to focus on the Sociology teaching agenda, by guiding debates in the Social Sciences field.

Eneseb agents: a periphery in the Brazilian Sociology field?

Although the rules for proposing WGs at Eneseb have changed over the years, the fact that groups are coordinated by more than one researcher and result from a public call remains a more general rule. Unlike what happens at CBS, whose WGs are organized by the SBS board, at Eneseb a call is opened for the proposition of WGs at each edition. These groups are analyzed by the scientific committee/organizer of the event. As the WGs are approved, registrations are opened to submit communications at the events.

Also, as a distinction concerning what happens at CBS, although Eneseb is an event organized by SBS, it is not necessary to be affiliated with this entity to organize WGs, propose workshops or participate in roundtables. This flexibility is essential for the event to be quite inclusive, especially concerning primary education teachers and students studying for a degree in Social Sciences.

As in other academic events, WGs coordination usually is the responsibility of researchers who have led the debate in a given area of knowledge. Considering that the community of researchers dedicated to Sociology teaching is still consolidating, we can also observe the consolidation of leadership in this debate from the WGs.

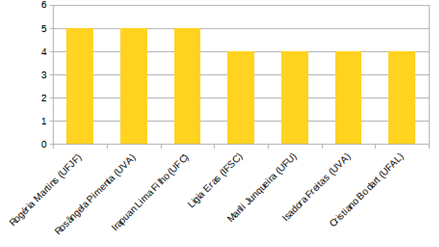

It is important to note that over the seven editions, there were 99 coordinators of the 68 WGs, of which 29 coordinated WGs on more than one occasion. Fifteen researchers coordinated WGs in two editions, seven coordinated in three editions, four coordinated in four editions, and three researchers coordinated groups in five editions. This scenario tends to point to a consolidation of academic leaders who have debated Sociology teaching in Brazil. It is noteworthy that during the 6th Eneseb, only two WGs were coordinated by researchers who were not present in other editions of the event. In Figure 1, we indicate the researchers who worked in the most significant number of editions of Eneseb as coordinators.

Source: The Author (2021).

Figure 1 Researchers who coordinated WGs in a more significant number of Eneseb editions.

We can observe with this graph that the researchers with the most significant participation in the coordination of WGs at Eneseb, consequently those who have significant symbolic capital in the area, belong predominantly to peripheral institutions in the academic field of Brazilian Sociology, being linked to institutions without stricto sensu postgraduate degrees in the area or even that are not at the top of the evaluation hierarchy of the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes), courses grade 6 and 7. This data is relevant insofar as it also demonstrates the relevance of peripheral institutions in the academic system in this debate and the existence of other criteria for legitimizing these researchers.

Another relevant data regarding the profile of these researchers is that, unlike the profile of CBS participants whose professional identity is constituted from the postgraduate course, as Dwyer, Barbosa, and Braga (2013, p. 156-157) rightly indicate:

In the case of SBS members, only 73.0% of respondents have a degree in Social Sciences. This is because what characterizes this group is the possession of a postgraduate degree in Social Sciences. [...] in our discipline, it is in postgraduate studies that the perspective of one of the possible professional identities takes hold.

In the case of the 99 coordinators of Eneseb’s WGs, only eight graduated in other areas of knowledge. Therefore, initial training in the field of Social Sciences predominates. In the case of postgraduate training, 47 of them have the highest degree in the area of Social Sciences. We could interpret this data from the hypothesis that the debate on the Sociology Teaching is linked to questions elaborated from graduation associated with the performance of social scientists in the educational field.

We should also highlight the presence of researchers whose research objective was the Sociology Teaching in their postgraduate work at the master’s and/or doctoral level. Therefore, we can see that the formation of staff of researchers focused on this theme has unfolded in the development of academic leaders in this debate, who tend to be inserted in different institutional spaces. We emphasize that, in addition to postgraduate training in Social Sciences, that in Education is also profoundly relevant to this field, considering that many WG coordinators have PhDs in Education, although predominantly graduated in Social Sciences, which reflects their own transits, that are common in this interface between Social Sciences and Education.

It is still important to realize that only a minority of researchers are linked to graduate studies. Among the coordinators, 24 are members of academic postgraduate programs, 16 of which work in Sociology/Social Sciences programs, five in Education, two in Teaching, and one interdisciplinary. We observed, however, that most are researchers linked to programs that can be considered peripheral or even ‘off the axis’ (Barreira, Cortês, & Lima, 2018) since only two coordinators are linked to Sociology programs with grades 6 or 7 (UFRGS, Unb)21. Likewise, only two researchers who coordinated WGs at this event were CNPq research productivity fellows - linked to UFSC and Unb - one of the most central distinct elements in the Brazilian academic field (Oliveira, Melo, Pequeno, & Rodrigues, 2022).

This point leads us to the hypothesis about the relevance of the periphery to innovation in the field since the institutions at the top of the academic hierarchy in Brazilian Sociology have a more consolidated research agenda. In a similar way to what Bastos (2002, p. 201, emphasis added), indicating that “[...] the analysis from the periphery allows us to inquire about the principles that articulate the system [...]” when reflecting on the São Paulo school, we can understand that from the periphery of the field of Brazilian Sociology it is possible to capture the dynamics of Sociology teaching better.

The data briefly presented here allow the perception of the specific more general characteristics of the coordinators of Eneseb’s WGs, which at the same time also reveals essential aspects of the field of Sociology teaching itself. This does not mean that the community of researchers dedicated to Sociology teaching necessarily shares the same characteristics. However, this survey gives us interesting clues to think about the morphology of this field from its agents.

Final Considerations

In this short work, we seek to examine the dynamics of Eneseb since its inception, starting from the WGs as analytical units, considering both their themes and the profile of their researchers. It is important to reaffirm, however, that the community of researchers is not limited to the coordinators of these groups, nor to Eneseb itself, considering the existence of other institutional spaces in which agents dedicated to this theme circulate. We sought to make visible the existence of specific agendas and central agents in this debate articulated from this event, which has consolidated itself as the leading national forum for discussion on the Sociology teaching in Brazil.

As can be seen, some themes explored in the WGs have specific stability over the different editions of Eneseb while also incorporating new discussions, which have gained prominence in the field of Social Sciences in general, such as those related to race and gender. This demonstrates that, despite being a field impacted by the Social Sciences agenda in a more general way, it has relative autonomy, which allows the emergence of its own debates. In other words, we can indicate from these data that there is an indication that the Sociology teaching is a field in the process of becoming autonomous.

Regarding the agents, there are indications of a stable community of researchers dedicated to the subject, inserted in different institutions in the country, especially in relatively peripheral institutions in the academic field of Social Sciences. This data reinforces our hypothesis presented in the previous paragraph that this is a field in the process of becoming autonomous, as agents located in central institutions in the field of Sociology do not necessarily occupy a dominant position.

The elements brought here allow us to glimpse a specific morphology of the field of Sociology Teaching in Brazil, although the discussion about the fact that the Sociology teaching constitutes a field or a subfield in Brazil is still open (Rêgo Ferreira & Oliveira, 2015; Bodart & Souza, 2017)22. It is necessary to advance the agenda, considering other spaces of circulation of agents that integrate this field and other spaces of distinction and academic dispute.

REFERENCES

Azevedo, G. C. (2014). Sociologia no Ensino Médio: uma trajetória político-institucional (1982-2008) (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói. [ Links ]

Barreira, I., Côrtes, S., & Lima, J. C. (2018). A sociologia fora do eixo: diversidades regionais e campo da pós-graduação no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Sociologia, 6(13), 76-103. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20336/rbs.259 [ Links ]

Barreto, P. C. S., Rio, F., Neves, P. S. C., & Santos, D. B. R. (2021). A produção das Ciências Sociais sobre as relações raciais no Brasil entre 2012 e 2019. BIB - Revista Brasileira de Informações Bibliográficas em Ciências Sociais, 94, 1-35. [ Links ]

Bastos, É. R. (2002). Pensamento social da escola sociológica paulista. In S. Miceli (Org.), O que ler na ciência social brasileira: Sociologia (p. 183-232). São Paulo, SP: Sumaré-Anpocs. [ Links ]

Beigel, F. (2009). La Flacso chilena y la regionalización de las ciencias sociales en América Latina (1957-1973). Revista Mexicana de Sociologia, 71(2), 319-349. [ Links ]

Bodart, C. N., & Cigales, M. (2017). Ensino de Sociologia no Brasil (1993-2015): um estado da arte na pós-graduação. Revista de Ciências Sociais, 48(2), 256-281. [ Links ]

Bodart, C. N., & Souza, E. D. (2017). Configurações do ensino de Sociologia como um subcampo de pesquisa: análise dos dossiês publicados em periódicos acadêmicos. Ciências Sociais Unisinos, 53(3), 543-557. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4013/csu.2017.53.3.14 [ Links ]

Bodart, C. N., Azevedo, G. C., & Tavares, C. S. (2020). Ensino de Sociologia: processo de reintrodução no ensino médio brasileiro e os cursos de Ciências Sociais/Sociologia (1984-2008). Debates em Educação, 12(27), 214-235. DOI: https://doi.org/10.28998/2175-6600.2020v12n27p214-235 [ Links ]

Brunetta, A. A., & Cigales, M. P. (2018). Dossiês sobre o ensino de Sociologia no Brasil (2007-2015): temáticas e autores. Latitude, 12(1), 148-171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.28998/lte.2018.n.1.7416 [ Links ]

Caregnato, C. E., & Cordeiro, V. C. (2014). Campo científico-acadêmico e a disciplina de sociologia na escola. Educação & Realidade, 39(1), 39-57. [ Links ]

Caruso, H., & Santos, M. B. (2019). Rumos da Sociologia na educação básica: ENESEB 2017, reformas, resistências e experiências de ensino. Porto Alegre, RS: Editora Cirkula. [ Links ]

Connell, R. (2019). Canons and colonies: the global trajectory of sociology. Estudos Históricos, 32(67), 349-367. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S2178-14942019000200002 [ Links ]

Decreto n.º 16.782-A de 13 de janeiro de 1925. (1925). Estabelece o concurso da União para a difusão do ensino primário, organiza o departamento nacional do ensino, reforma o ensino secundário e o superior e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Decreto n.º 21.241 de 4 de abril de 1932. (1932). Consolida as disposições sobre a organização do ensino secundário e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Dwyer, T., Barbosa, M. L. O., & Braga, E. (2013) Esboço de uma morfologia da sociologia brasileira: perfil, recrutamento, produção e ideologia. Revista Brasileira de Sociologia, 1(2), 147-178. [ Links ]

Fernandes, F. (1980). A Sociologia no Brasil: contribuição para o estudo de sua formação e desenvolvimento. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Franch, M., & Nascimento, S. (2020). A produção antropológica em gênero e sexualidades no Brasil na última década (2008-2018). BIB - Revista Brasileira de Informações Bibliográficas em Ciências Sociais, 92, 1-29. [ Links ]

Gonçalves, D. N. (2015). A sociologia e a escola em debate nos Encontros Nacionais sobre o Ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica. Ciências Sociais Unisinos, 51(3), 309-315. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4013/csu.2015.51.3.08 [ Links ]

Gonçalves, D. N., Moelin, D., & Meirelles, M. (Orgs.), (2016). Rumos da sociologia o ensino médio: ENESEB 2015, formação de professores, PIBID e experiências de ensino. Porto Alegre, RS: Cirkula. [ Links ]

Handfas, A. (2011). O Estado da Arte do ensino de sociologia na educação básica: um levantamento preliminar da produção acadêmica. Inter-Legere, 1(9), 386-400. [ Links ]

Handfas, A. (2021). Memórias do I Encontro Nacional de Ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica. In A. Oliveira, A. M. B. Engerroff, D. Greinert, & M. Cigales (Orgs.), Conquistas e resistências do ensino de sociologia: ENESEB 2019 (p. 27-30). Maceió, AL: Café com Sociologia. [ Links ]

Handfas, A., & Carvalho, I. (2019). Ensino de sociologia: a constituição de um subcampo de pesquisa. Em Tese, 16(1), 214-230. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5007/1806-5023.2019v16n1p214 [ Links ]

Handfas, A., & Maçaira, J. P. (2012). O estado da arte da produção científica sobre o ensino de sociologia na educação básica. BIB - Revista Brasileira de Informação Bibliográfica em Ciências Sociais, 74, 43-59. [ Links ]

Lei nº 11.684, de 2 de junho de 2008. (2008, 2 junho). Altera o art. 36 da Lei no 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, para incluir a Filosofia e a Sociologia como disciplinas obrigatórias nos currículos do ensino médio. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

Liedke Filho, E. D. (2005). A sociologia no Brasil: história, teorias e desafios. Sociologias, 14, 376-437. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-45222005000200014 [ Links ]

Lippe Oliveira, L. (2005). Diálogos intermitentes: relações entre Brasil e América Latina. Sociologias, 14, 110-129. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-45222005000200006 [ Links ]

Moraes, L. B. P. D. (2016). Representando disputas, disputando representações: cientistas sociais e campo acadêmico no ensino de sociologia (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A., Engerroff, A. M. B., Greinert, D., & Cigales, M. (Orgs.), (2021). Conquistas e resistências do ensino de sociologia: ENESEB 2019. Maceió, AL: Café com Sociologia. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A., Melo, M. F., Pequeno, M., & Rodrigues, Q. B. (2022). O perfil dos bolsistas de produtividade em pesquisa do CNPq em Sociologia. Sociologias, 24(59), 170-198. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/15174522-106022 [ Links ]

Raizer, L., Mocelin, D., & Meirelles, M. (2016). Balanço do ENESEB 2015: conquistas, desafios e agenda para as próximas edições. In D. N. Gonçalves, D. Mocelin, & M. Meirelles (Orgs.), Rumos da Sociologia o Ensino Médio: ENESEB 2015, formação de professores, PIBID e experiências de ensino (p. 189-213). Porto Alegre, SC: Cirkula. [ Links ]

Rêgo Ferreira, V., & Oliveira, A. (2015). O Ensino de sociologia como um campo (ou subcampo) científico. Acta Scientiarum. Human and Social Sciences, 37(1), 31-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4025/actascihumansoc.v37i1.25623 [ Links ]

Röwer, J. E. (2016). Estado da arte. Dez anos de Grupos de Trabalho (GTs) sobre ensino de Sociologia no Congresso Brasileiro de Sociologia (2005-2015). Civitas, 16(3), 126-147. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15448/1984-7289.2016.3.24754 [ Links ]

Sociedade Brasileira de Sociologia. (1955). Anais do 1º Congresso Brasileiro de Sociologia, 1954. São Paulo, SP: SBS. [ Links ]

12As Moraes (2016) indicates, ABECS also emerged to bring together primary education teachers around a scientific association focused on the discussion about the teaching of social sciences, something that did not exist in the SBS at that time. Currently, the SBS allows the affiliation of primary education teachers, even if they do not have a minimum master’s degree (as is required of the other members).

13It is essential to mention that other scientific associations in the field of Social Sciences have incorporated discussions on teaching, such as the Brazilian Association of Anthropology (ABA), the Brazilian Political Science Association (ABCP), and the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Social Sciences(Anpocs).

14Sociology as a school subject in Brazil began to be introduced at the end of the 19th century, through some specific experiences. As of the Rocha Vaz (Decree No. 16,782-A of January 13, 1925) and Campos (Decree No. 21,241 of April 4, 1932) reforms, it became part of the preparatory courses. With the Capanema Reform (1942), preparatory courses were extinct, and, as a consequence, sociology disappeared from the school curriculum during that period. However, it remained an integral subject of the curriculum of traditional schools, which were secondary courses for teacher training.

15For a more careful examination of the SBS Sociology Teaching WG, see Röwer (2016).

16For examining the trajectory of Law No. 11,684 (2008) in the National Congress, see Azevedo (2014).

172009, 2017, 2019, and 2021 editions, CBS and Eneseb, took place at the same institution, while the 2011 and 2015 editions took place in the same city/metropolitan region but in different institutions. The 2013 edition was the only one in which CBS and Eneseb took place in different states, and with a significant time gap between the two events, with the CBS taking place in Salvador, with headquarters at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), and the Eneseb in Fortaleza, based at the UFC.

18It is essential to mention that the organizing committees of the different editions of Eneseb have sought to dialogue mainly with the state education departments, aiming at releasing teachers to participate in the activities of the event, which usually starts on Friday, as well as the validation of the activities developed at the event for the career progression of teachers, understanding that this is a space for continuing training.

19It is the professional master’s degree in Social Sciences for Secondary Education of the Joaquim Nabuco Foundation (Fundaj). Later, this institution joined, with eight other universities, the Professional Master’s Degree in Sociology in the National Network (ProfSocio), whose first classes entered 2018, currently coordinated by the Federal University of Ceará.

20The graduate program in sociology at the State University of Londrina (UEL) had a research line in Sociology Teaching that was suppressed in the process of reconfiguring the program.

21Programs of excellence are those rated with grades 6 and 7 on Capes. Both the Graduate Program in Sociology at UFRGS and UnB are currently rated with the maximum grade (7).

22In this article, we assume the interpretation that the Sociology teaching constitutes a field in the process of autonomization.

Received: December 14, 2021; Accepted: July 25, 2022

text in

text in