Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Acta Scientiarum. Education

versão impressa ISSN 2178-5198versão On-line ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.44 Maringá 2022 Epub 10-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v44i1.62306

TEACHERS' FORMATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

Teaching techniques and cultural resistance: Contribution to Sociology teaching practices

1Departamento de Sociologia e Antropologia, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Av. Hygino Muzzi Filho, 737, 17525-900, Marília, São Paulo, Brasil.

The aim of this article is to present the results of research conducted at a school in a peripheral neighborhood of the municipality of Marília (São Paulo state, Brazil). The research started from the assumption that the cultural process must be observed from a micro- and a macro-sociological outlook on the basis of Paul Willis’ analyses. The latter stresses that cultural processes may be absorbed and reformulated in a dialectical fashion, remodeling and creating a process of cultural resistance based on the choices made by the very working class in question, which the author termed a school counterculture. Based on this reference, we observe the need to know the school reality to approximate scientific knowledge and students’ cultural horizons through a didactic transposition. Hence, starting off from a pedagogical sequence with the premise of getting to know students’ reality, it was possible to adapt sociological knowledge to these students’ realities by teaching techniques and producing teaching materials. This enabled acquiring a greater amount of content from the subject of Sociology by the students, thus constituting new forms of teaching-learning and building more solid training for teachers in the field of Sociology.

Keywords: schoolcounterculture; sociologyteaching.

O objetivo deste artigo é apresentar os resultados da pesquisa realizada em uma escola da periferia de Marília. Partindo do pressuposto de que o processo cultural deve ser observado dentro de uma visão micro e macrossociológica, tendo como base as análises de Paul Willis, o qual destaca que os processos culturais podem ser absorvidos e reelaborados de uma forma dialética, remodelando e criando um processo de resistência cultural a partir das escolhas feitas pela própria classe operária em questão, que o autor denominou de uma contracultura escolar. A partir dessa referência, observamos a necessidade do conhecimento da realidade escolar para aproximar os conhecimentos científicos ao horizonte cultural dos estudantes através de uma transposição didática. Assim, a partir de uma sequência pedagógica que tinha por premissa conhecer a realidade dos estudantes foi possível adaptar os conhecimentos sociológicos à realidade desses estudantes, através de técnicas de ensino e produção de material didático possibilitando uma maior aquisição dos conteúdos da disciplina de sociologia por parte dos estudantes, constituindo novas formas de ensino-aprendizagem e construindo uma formação de professores na área de sociologia mais sólida.

Palavras-chave: contracultura escolar; ensino de sociologia

El objetivo de este artículo es presentar los resultados de la investigación realizada en una escuela de la periferia del municipio de Marília, en el estado de São Paulo. Tomando como punto de partida el supuesto de que el proceso cultural debe observarse desde una perspectiva micro y macrosociológica, basada en los análisis de Paul Willis, quien resalta que los procesos culturales pueden ser absorbidos y reelaborados de una manera dialéctica, remodelando y creando un proceso de resistencia cultural con base en las decisiones tomadas por la propia clase obrera en cuestión, que el autor denominó contracultura escolar. Con base en esta referencia, observamos la necesidad de conocer la realidad escolar para acercar los conocimientos científicos al horizonte cultural de los estudiantes mediante una transposición didáctica. Así pues, con base en una secuencia pedagógica que tenía la premisa de conocer la realidad de los estudiantes, fue posible adaptar los conocimientos sociológicos a la realidad de dichos estudiantes, mediante técnicas de enseñanza y producción de material didáctico, de manera que permitiera una mayor adquisición de los contenidos de la asignatura de sociología por parte de los estudiantes, constituyendo nuevas formas de enseñanza-aprendizaje y desarrollando una formación docente más sólida en el ámbito de la sociología.

Palabras clave: contra la cultura escolar; enseñanza de la sociologia

Introduction10

The epigraph above is an excerpt from the award-winning book by Itamar Vieira Junior, Torto Arado (2021). In this excerpt, the author narrates the relationship of the character Belonísia with the school, long anticipated by the community and by her father; but the school did not attract her interest, she was the victim of a domestic accident with a knife that mutilated her tongue and part of her sister’s tongue, Bibiana. The school teacher, D. Lourdes, a refined white woman, even knowing Belonísia’s disability, taught her the lyrics of the national anthem to sing, along with the younger children who struggled to read words and phrases that mixed with the local accent, which Professor Lourdes interrupted every two words, insisting on the correct pronunciation pattern of the cultured norm.

This image of a school in the corners of Brazil that is unattractive, not at all inclusive, distant from the sociocultural reality of its students is not something isolated, but it seems to be the keynote of a structural problem that permeates the educational reality in Brazil. Such a situation also occurred in the sociology discipline, Alberto Guerreiro Ramos11, in the 1950s, and made harsh criticisms of the so-called sociology textbooks which were tainted with foreignness and had no connection with the reality experienced by students. This detachment from concrete reality led to unusual situations, such as those of a teacher who carried out an experiment with a frog to demonstrate Pflüger’s laws of elementary reflexes by following the steps of the textbook; the teacher carried out the experiment once, twice and the frog’s reaction was not like the one described in the book, so the professor disregarded such an experience as if to say: the animal was wrong (Ramos, 1995). Soon after, it was discovered that the frog’s reaction was the same as that which will take place in the teacher’s experiment when taken out of its natural habitat. There were countless examples of chemistry teachers comparing a certain chemical reaction to a cherry or a certain geographical shape to a pear, which we can agree is something very distant from a child in the interior of Bahia at that time. This example is substantial from one of the great apexes of the debates around the introduction of sociology in the curriculum of secondary education carried out by two famous sociologists, Alberto Guerreiro Ramos and Florestan Fernandes, inside the 1st Brazilian Congress of Sociology in 1954.

The introduction of the discipline of sociology as mandatory in high school in 2008 had an important characteristic, which was the intense work on the part of sociology researchers and professors to develop materials and didactic sequences for better use of the discipline in the classroom. Despite this effort and the huge volume accumulated in just over a decade, the discipline still lacks accumulated experience in terms of school work, the methodological issue, didactic resources and the way and how to teach sociology12 and studies around the cultural issue about students, their options, and desires, which are very little understood, nor do we try to give voice to these students, treat them as subjects and participants in the educational process.

Thus, the research we carried out in a school on the outskirts of the city of Marília sought to make this movement, to know and understand the cultural horizons of these students, the reality to which they are inserted and how the school is configured in this process. Their lack of motivation with school, denial of school authority and lack of interest in studies, the prevalence and desire to enter the job market were the questions which guided the research. Based on these questions raised with the students, we chose to read the classic work by Paul Willis, Learning to labor, given the possible similarities between the results of the ethnography carried out in the late 1970s and the peripheral culture of the working students of the Marília school. We followed the classroom for a period of one year, where it was possible to observe the culture, lifestyles and motivations of these students, and we were also able to work with activities which lead to better understanding of the contents of sociology teaching.

From these elements, it was possible to observe that much of the lack of interest in the school and its contents stems from two fundamental aspects: distancing the school itself and its contents from the sociocultural reality of the students, and then by denying these contents, the students consciously choose other alternatives. This is equivalent to saying that there is the creation of a kind of counterculture within the school itself, a denial, but by choice and by the loss of practical concreteness of school contents.

Furthermore, based on this understanding, we sought to create forms, models and especially teaching techniques which sought to adapt the sociology discipline contents to the sociocultural reality of the students. As is well known, sociology is a theoretical discipline that is difficult to understand; it works with varied and complex concepts that seek to understand humans, their socialization processes and their social relationships.

The formation of sociology and sociological studies in education

The constitution of sociology and social sciences in Brazil had different characteristics from the construction of this discipline in countries with developed capitalism. While the social sciences in developed countries are developed outside the University and find their vocation in civil society and in social movements, in Brazil “[...] they arise from the intellectual project of a conservative elite, such as that of São Paulo, with the university existence before finding expression in social life” (Werneck Vianna, 1997, p. 173).

Before this period reported by Werneck Vianna, the Social Sciences in Brazil had an essayistic type characteristic based on generic, abstract concepts, without a clear definition of the object: “[...] , strongly influenced by European sociological literature” (Werneck Vianna, 1997, p. 181). For Fernandes (1958), it is possible to identify three versions of ‘extra-scientific’ studies, with the first being the most generalized and simple and which makes any systematic reflection on social problems in the country a sociological reflection; the second converts sociology into an ideological polarization, while the third would be the maturity of sociological studies with autonomy and scientific standard.

The characteristics in the educational field were identical, and the educational issue was dealt with in a generic way without conceptual density. In this case, it is important to point out that the authors did not treat education in a familiar way, since most of them were jurists, journalists and pointed to education within the broader field of social thought.

When analyzing this period of sociological thought, Florestan Fernandes highlights it as being strictly linked “[...] to our proverbial intellectualist and aristocratic education, which gave rise to a well-defined tendency to the over-evaluation of theoretical work, represented as pure manipulation of abstract ideas” (Fernandes, 1958, p. 221). The traditionalist teaching of exclusively intellectualist and verbalist training, with its core being the training of the engineer and the law degree, corroborated to perpetuate the ‘extra-scientific’ pattern.

Although this division is classical, it is not a consensus among scholars of the history of Brazilian Social Sciences. Wanderley Guilherme dos Santos (2002) analyzed the development of Social Sciences by examining historical and social events in Brazilian political life and the methodological advances of the discipline within this historical and social context. By intertwining the development of Social Sciences with the political/social history of the country, the author highlights the insertion of Brazil in world history as a colonial condition (1500-1822), and after Independence in 1822 a new stage in the history of political life of the country began with ramifications for political and social thought, which would be “[...] depending on the organizational evolution of scientific activity, which exhibited an implicit judgment on the social sciences and on their relevance to the structure of the new country” (Santos, 2002, p. 23).

Wanderley Guilherme observed the development of the Social Sciences in a broader way as a social political thought, as the political and social reflections within the literature and law and social organization analyzes are part of what he calls Brazilian political-social thought. The author criticizes what he calls the institutional matrix, which conceives the development of Brazilian social thought from organizational and institutional frameworks.

If, on the one hand, we observe divergences in the analysis of the development of the Social Sciences, on the other hand, a renovating educational movement13 in its bases sought a scientific standard incorporated in American pragmatism and in the French sociological school:

The great essayism had incorporated Sociology as a rational foundation for the action of a State that would build the nation, leading it to civilizing ideals. In an opposite moment, among the intellectuals of education, sociology is interpreted as an analytical resource that legitimizes the social promotion of individuals through the action of the school. Not coincidentally, the references of this Sociology of Educators became preferentially American - the case of Anísio Teixeira is exemplary - and its background theme consists of the relations between the State and the nation; and yes, centrally in social inequalities and the role of education for egalitarian citizenship in terms of life opportunities (Werneck Vianna, 1997, p. 183).

The historical landmark of the intellectual education movement to which Werneck Vianna refers was the Manifesto of New Education Pioneers of 1932. The 1932 Manifesto, as it became conventionally known, traces an analytical framework of Brazilian education that avoids generic-abstract speculations when dealing with educational problems in a conceptual way and proposing educational policies for the reconstruction of the nation. We can identify that the relationship between a sociology that scientifically thinks about educational problems first occurs in the Manifesto of New Education Pioneers (Cunha & Totti, 2004).

The creation of the School of Sociology and Politics in 1933 and of the University of São Paulo in 1934 corroborates this process, enabling the first steps towards an institutionalization project, which had one of its main exponents in the figure of Fernando de Azevedo, including works such as the Principles of Sociology and Educational Sociology as part of the constitution of a theoretical corpus of a discipline still in formation, and the book Brazilian Culture advances in the analysis of the Brazilian structure, intertwining the relations between culture, education and society and envisioning education as a transmission factor cultural. This was an affirmation moment of the University and of Sociology in the academic environment, as the University was considered by its creators as a new cultural modality, of reflection and concern about the facts of social life: “[...] the transmission of content generates the effort to systematize systems of thought expressed in great syntheses, often supported by long discourses on the method” (Arruda, 1995, p. 116). According to Arruda, the idea was to create a symbolic environment in which he endorsed the quality of his analyzes and productions: “[...] the academic activity implied, for all of it, in a rationalization process of knowledge production, when defining and reordering the different areas and establishing its own domain” (Arruda, 1995, p. 119).

Sociology, in this conception, had as a goal to emancipate itself as a science, which would engender a remodeling of techniques and theories, the concern with the theoretical field when seeking an identity for the Social Sciences, as a specific field of a science with: “[ ...] the discussion of techniques, methods, interpretations consistent with the level of rigor practiced in more advanced centers” (Lahuerta, 1999, p. 35).

Methodological concerns were the keynote of the development of sociology, “[...] the Social Sciences in Brazil emerged and have developed under the influence of two processes: the form of absorption and internal diffusion of the methodological and substantive advances generated in cultural centers abroad” (Santos, 2002, p. 19). Santos points out two important factors in the development of Social Sciences, namely the incorporation of theoretical trends from abroad and the rigor of methodological production.

The emphasis on methodological work is linked to the institutional factor, the University creates a space for producing ideas and knowledge, and this knowledge produced must be guided by the academic requirements of scientificity. The boundaries of scientificity of an academic work are measured by the degree of rigor and rules of analysis and study determined by the research object.

Therefore, the emergence of the university would be incomprehensible without the presence of favorable social conditions, and at the same time instituting new models of intellectual production, meaning the constitution of academic staff transformed the criteria for knowledge production from which group identities emerge, now backed by training and a professional principle endowed with a certain unity (Arruda, 1995). The principle of academic legitimacy is located in institutionality; the paradigms and social problems must be absorbed by the scientist who, in addition to giving a rational treatment to them, produces a specific discourse for this audience, and the Social Sciences developed in university frameworks redirect themselves for making criteria and norms to elaborate scientific work. The oppositions within the intellectual system will be punctuated by the differences between reflections considered rigorous and scientific and those seen as impressionistic and arbitrary (Arruda, 1995).

There is an important initiative within this paradigm by Emilio Willems and Romano Roberto who created the Sociologia: Revista Didática e Científica journal in 1939, whose initial aim was to disseminate teaching techniques and improve the didactics of the young discipline of Sociology in Brazil. Willems makes an enormous contribution within the journal, linking the theoretical issues of the discipline, its authors and methods with field research works, seeking elements in concrete social practice which are in line with the references described by sociological theories. There were many possibilities for research placed by Willems in the first issues of the journal, with research on the daily practice of the city of São Paulo such as: the prohibition of yellow immigration in the United States of America and how this would reverberate in Brazil, confronting with the theories of acculturation, such research would involve fieldwork in the Liberdade neighborhood. Other issues such as social control and the daily practice of skipping the lines to get on the bus at its stops, interviews with criminals to assess the possible causes of their arrest were also part of the list of pedagogical proposals for the Sociology discipline practices. However, this dynamic in the journal was losing strength for a few reasons, one of which is that the initial idea of using contributions and didactic experiences of sociology professors from numerous locations was not successful and the very development and maturation of the discipline in the academic and institutional environment made it change the name and guidelines of the magazine itself, as explained by Limongi (2015, p. 161): “[...] the subtitle of the Sociologia journal is changed and changes from a Didactic and Scientific Journal to a Journal dedicated to theory and research in Social Sciences. In fact, the didactic theme is abandoned in favor of research, since, according to the new directors, the situation of Brazilian Social Science was already different”. This new phase of research began in 1949 and marks a new stage of research and studies on the Brazilian reality.

In this new stage of Social Sciences and Brazilian Sociology, Florestan Fernandes and Roger Bastide were fundamental in changing the style of Social Sciences, printing a new model of social science guided by rigorous methodological criteria, establishing the professionalization of the social scientist as essential, which included an arduous work of discipline based on extensive readings and notes, debates and analyses, rigorously seeking the conceptual definition.

This work sought to distance itself from common sense, creating a split between lay and scientific thinking; language acquires a dimension where it is permeated with ordered concepts, guided by values and ideals of scientific knowledge, “[...] The sociologist’s writing conveys to the reader the impression that he is in a torturous dialogue with himself” (Arruda, 1995, p. 142). The language was related to searching to identity the concept, making the thought more rigorous. In addition to language, the choice of object, theory and the cut which were made of reality, privilege the disciplinary method of data collection.

Thus, modification occurs in the way ideas are exposed, the text must be the conscious expression of the author who writes it, they must have full mastery of the theory on display, which are minimum necessary conditions for a safe verification analysis. Criticism starts to focus on the essay, seen as a foreign form to the rules of the game of science and organized theory. The essay style rejects the notion of method and systematic ordering of the exhibition. Therefore, the essay derives its impulse from the departure from scientific canons, or because it intends to elaborate a radical critique of the principles of science (Arruda, 1995).

The themes take another impulse towards scientific discourse, with projects on national formation and the State as a herald of development which are not part of the intellectual horizon of USP sociologists. In this case, by creating a scientific standard in the field of Social Sciences, Florestan becomes a landmark and consolidates an interpretation of sociology development.

Linked to this development of Social Sciences, we have the creation of the Brazilian Center for Educational Research and the Regional Center in São Paulo in the 1950s, boosting research and dialogue between Social Sciences and Education with the launch of a journal of the same name. The creation of the Sociedade Brasileira de Sociologia in 1954, and the debates transcribed in the annals of its 1st Congress between Florestan Fernandes and Alberto Guerreiro Ramos about the teaching of sociology show how important the educational debate meant for that generation.

From this, we had a generation of intellectuals with numerous studies on the various problems involving education such as The student and the transformation of Brazilian society by Marialice Foracchi, author of an organization jointly with Luiz Pereira Education and Society, Education and society in Brazil by Florestan Fernandes and later the classic work by Luiz Pereira The school in a metropolitan area.

As can be seen in this quick itinerary of a history of the Social Sciences and its studies linked to education, we realize that sociology was born institutionally with a close relationship with educational themes and maintained this exchange until the end of the 1960s, a period in which there was a detachment due to the university reform of 1968; furthermore, the dismantling of the CBPE and the end of economic resources for research, the withdrawal of sociology from secondary education and even the perpetuation of the reproductive paradigm contributed to the disinterest of social scientists in education.

However, research in this area was resumed with the reintroduction of sociology in the high school curriculum, the creation of the ‘sociology teaching’ working group at the Brazilian Society of Sociology and, albeit timidly, the Graduate Programs in Sociology and Sciences Social programs sought to integrate a list of research lines linked to education, such as: sociology of education and teaching sociology. Funding agencies begin to direct resources and encourage programs with these characteristics, as in the case of PIBID/Capes, thereby enabling a greater range of research in this knowledge area.

Pedagogical didactic sequence

With the introduction of sociology in high school through resolution of the National Education Council 04/2006 and Federal law 11,684/2008 (Mendonça, 2017), the government of the State of São Paulo decided to produce support material for teachers and students called São Paulo Faz Escola, according to the authors of the material (Pimenta & Schrijnemaekers, 2011). The idea was not to bring the knowledge of the bachelor’s degree in Social Sciences to high school or even less to train sociologists, it was about promoting a look at the place where they live and at Brazilian society through the lens of sociology in high school students, focusing on the interdisciplinarity between the three areas of Social Sciences: Anthropology, Politics and Sociology together with other areas of the humanities, providing students with:

[...] formation and development of the student ‘as a human being’. It is therefore ‘sensitivity’ and not ‘reasoning’, as sociological ‘reasoning’ must be developed in college by those who will become sociologists and study society scientifically. However, sociological ‘sensitivity’ forms part of basic education and has been advocated since the 1980s by educators and social scientists. It therefore remains to be put it into practice (Pimenta & Schrijnemaekers, 2011, p. 409, author’s emphasis).

Such concepts would be in accordance with the National Curriculum Guidelines for secondary education regarding Sociology teaching, “[...] through two principles: that of denaturalization and estrangement” (Pimenta & Schrijnemaekers, 2011, p. 410). Through these principles, São Paulo faz Escola would provide students with a look of detachment and criticism of the object of reality, with it not appearing to them that such social phenomena sounded like something natural, inherent to common sense. “It is therefore about building an attitude or sensitivity with the students which allows them to always seek an explanation of how and why social phenomena occur, always refusing the explanations that things have always been like this or should be like this” (Pimenta & Schrijnemaekers, 2011, p. 410). Following the authors’ explanation, such sociological sensitivity is supported by Émile Durkheim’s methodological principles that social facts must be treated as things, and that the researcher must remove preconceptions when analyzing such facts. This element would be at the beginning and constitution of sociology as a science and would provide young students with the possibility of building a sociological sensitivity capable of an independent interpretation of the social reality in which they live.

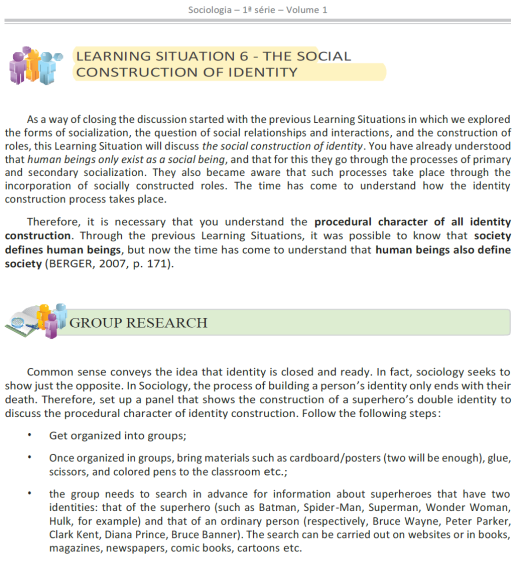

In spite of possible theoretical-methodological differences with the authors to which the authors of the material are supported, as well as the criticisms from numerous researchers14 who have focused on material across the State of São Paulo (Souza, 2019; Vellei, 2020), we did a preliminary analysis to apply it in the classroom and we observed that the material was far from the reality of the students in some learning situations. The examples did not reflect the reality of youth living on the outskirts of São Paulo cities, which distances the material from the sociocultural reality of the students, creating obstacles to the objectives of the material itself, which would enable sociological sensitivity in high school students. As an example, we put Figure 1 with the learning situation number 6, from the Sociology notebook of the 1st year of high school.

Source: Secretary of Education of the State of São Paulo (2014).

Figure 1. Learning situation number 6.

When analyzing the learning situation above, we observed that the approach to the concept of identity is worked on in a procedural way, which is in line with a classic and multidimensional approach “[...] of social complexity” (Cuche, 2002, p. 192), and that no individual or group is unidimensional, relating the concept of identity to culture and cultural diversity. Such a conceptual approach seems to us to be quite suitable for secondary education, given the characteristics of diversity in Brazilian society and the breadth of possibilities that youth culture makes possible. However, when proposing that students use cardboard, colored pens and other materials not available to the school, there is a certain lack of knowledge of the structural reality of most schools in São Paulo, with many of them lacking in basic structural points. Regarding the didactic character, such lack of knowledge is evident when relating the activity to Marvel superheroes, without connection with the daily reality of students and alien to the reality of Brazilian society..

Still referring to the learning situation, the absence of the so-called youth protagonism and of a more in-depth reflection does not become viable in its development, since an active and effective participation of the students during the activity is not envisaged. Thus, “[...] critical analysis of the activity is also not encouraged, as students could develop their own questions for the panel in order to diversify the debate” (Souza, 2019, p. 116). Thus, we carried out a thorough analysis of the material from São Paulo faz Escola and observed that the exemplification of the described learning situation was the keynote of all the didactic material, and had content which was distant from the sociocultural reality of the students. Given this finding, we sought to prepare a didactic sequence that took into account effective learning and enabled bringing the sociological content of high school closer to the reality of students by performing a didactic transposition.

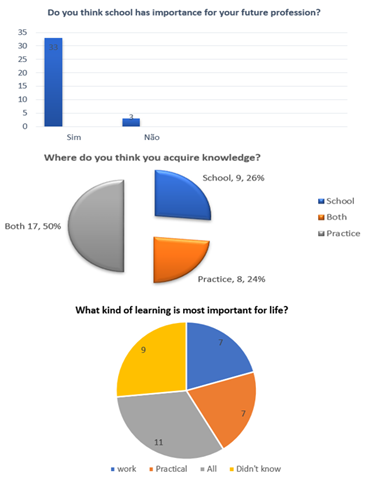

Leading students to understand the sociological content is not the easiest task given the complexity and subjectivity of some subjects in the discipline. Thus, we carried out a didactic sequence on the social function of the school through such difficulties, trying to understand the meaning and significance that the school has for these students. The didactic sequence had the participation of the sociology professor and students from Pibid15 (Institutional Program for Initiation to Teaching Scholarships) and from the teaching nucleus of Unesp, in which we developed some steps to evaluate the students’ prior knowledge about the topic, development, discussion and conversation circles, films, text and final activity to assess the learning level and meaning that the school has for those students. The sequence was developed with 2nd year high school students from a school in the west of Marília. First, we modified the classroom environment, creating spaces with groups and subgroups that occupied the classroom in a questioning and critical way, seeking to give voice to students and understand their relationship with the school environment. Below are the steps of the didactic sequence:

- We applied a questionnaire to the 2nd year high school class to identify the students’ prior knowledge of the school space. The questionnaire contained 3 questions, which are: ‘Do you think school will be important for your future profession?’, ‘Where do you think you acquire more knowledge?’ and ‘What kind of learning is most important for life?’16. In addition to the closed questionnaire, students could write about their understanding of the social function of the school. This step is important to guide the subsequent sequences.

- After the results of the questionnaires, we organized a debate circle between the students, the teacher and the PIBID scholarship holders to discuss the importance of the school in the social construction of the students’ lives and we held some theoretical classes on the social function of the school using sociological concepts .

- Following the activity, we used an audiovisual resource, an excerpt from the film ‘Pro Dia Nascer Feliz’, which portrays the situation of different public and private schools that serve different social classes, and we problematize the social function theme of the school to the different social classes.

In another class, we read an excerpt from the article ‘The crisis of senses and meanings in school: the contribution of the sociological gaze’ and after reading the text below, a debate circle was formed with the students to discuss the social function from school.

The bourgeois school represented an advance in society by placing knowledge transmission to all citizens as fundamental, but it also created an educational process that revolved around the principle of alienation and training for hardworking labor, a school model aimed at most basic activities of knowledge (reading, writing and counting), thereby destining a more general, classical and scientific school only to the elites (Mendonça, 2011, p. 344-345).

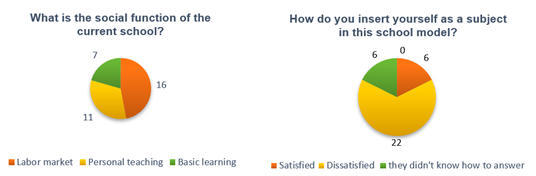

- After all this process, we applied a second questionnaire to compare if there was any change in the students’ opinion and learning after applying the didactic sequence. The questions were as follows: ‘What is the social function of the current school?’ and ‘How do you insert yourself as a subject in this school model?’. In addition to closed answers, students could write about the social function of the school and issue their evaluations after the activities were applied. Below we show the sequence of answers in Figures 2 and 3 before and after application of activities with excerpts from students’ writing.

Results of the questionnaires before application of the didactic sequence

Excerpts from student questionnaires:

It depends on the circumstance, I believe that learning from school should not be discarded, because through it we have access to many things, but many things that are transmitted to us we do not use, and what we really need to have learned is revealed to us outside of it. (I.C.S- 2º C).

For sure (sic) it is very important. Today school is practically everything in a person’s life. Due to the fact that today those who have education go far, and those who don’t simply stay at the bottom. I think this is wrong because it happens that not everyone who doesn’t have an education is because they didn’t want to study. There are cases of people who did not study because they preferred to start working early so as not to let the family go hungry. And that interferes a lot in getting a good job. Those who are educated today have a better profession than those who don’t.

Results of the questionnaires and excerpts after application of the didactic sequence

At first the social function of the school was to form capable and knowledgeable citizens. However, what has happened is more and more lay and uneducated students are leaving school, because that is exactly what governments want, people without training to be another employee in the job market.

I realize that everything we think is natural is actually imposed on us, capitalist society only wants us to work and not to think, so education does not have the necessary investment. And that we must not accept what is imposed on us, we must criticize it.

We noticed a big change in the students’ responses when evaluating the second questionnaire. Although the vast majority of students understand that the school is a place to acquire knowledge, most of the answers to the first questionnaire focus on the practical nature of learning (practical is understood as something connected to everyday life) and/or they did not know how to answer, while the school as a place of knowledge acquisition had a response rate of less than 1/3, and the open questions also corroborated this view.

After applying and developing the activity, a change was not only observed in the answers, but in the students’ critical behavior, and in improved reading and writing that they performed in the classroom. The answers to the question about the social function of the school, identifying the largest number of answers in the labor market, denotes the concern of these students being working class children with real and immediate needs of their social conditions. The role of non-belonging and dissatisfaction within the school environment is a result of the school reality experienced by them, the teaching/learning relationship and how the school views youth. The environmental changes in the classroom, the construction of dialogue with the students and mainly giving these students a voice were preponderant factors to achieve involvement in the activities and in discussing related topics. By bringing the problem closer to their reality and realizing that they are an integral part of the school process, such protagonism modified traditional relationships and enabled opening new windows and perspectives, not only of the school, but also of the very experience in society, enabling the denaturalization of social relationships.

The counter-school culture

The project was developed in a peripheral school on the west side of the city of Marília. Most of the students were workers who divided their time between studies and work. Seeking theoretical support to understand this reality, we focus on the ethnographic study of Paul Willis, in Birmingham, England. In this book Learning to labor: How working class kids get working class jobs, Paul Willis demonstrates a set of concerns related to the concept of ‘work force’ and the way it is prepared in our society to be applied to manual work. The author’s argument is based on the fact that relations in capitalist society are not passive and that the capitalist ideology permeated by the ruling class is not assimilated in a schematic way. Contrary to the structuralist theses very much in vogue in the 1970s, Willis questions the merely assimilative character of ideology in social structures that conceive the subject of the working class as a recipient of the dominant ideology; for Willis, such a process does not occur without disputes and these disputes are located in the production and reproduction of social relations in the social structures themselves, leading to the permanent dynamics of conflict and a dialectical analysis of capitalist relations in liberal democracies.

The author then more precisely and conceptually performs an interpretation of the ethnography described in the first part of the book in the second part of his book called analysis. For Willis, the intrinsic meaning of the rationality and dynamics of the cultural processes experienced by working-class youth, above all, the ways in which these cultural processes experienced by them generally contribute to the working class, and in another way (according to him), which unexpectedly prepare them to maintain and reproduce the social order. When the author highlights the importance of building a class identity, he argues that this issue is not truly reproduced until it is recreated in the context of what appears to be a personal and collective choice.

The workforce is an important element of this process, as it is the main mode of active connection with the world: the form par excellence of articulation between the self and the self through the concrete world. Once that basic link to the future has been made, everything else can pass for common sense (Willis, 1991, p. 13).

Paul Willis supports his hypothesis that a certain subjective idea of manual labor and an objective decision to apply it to manual labor are produced in a specific place, in the ‘Working counter-school culture’; according to Maia, Fresche, Santos, and Gomes (2000), it is in this environment that working-class themes are mediated, even individuals and groups in their own specific context that working-class youth creatively develop, transform, and finally end up reproducing aspects of the broader culture in its own praxis. The British sociologist interprets this in the light of the concepts of the work Symbolic Power and educational inequalities by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1983), that ideological power relations are developed among these young people, determined by the social structure in which they are inserted, sometimes unconscious and subliminal in the form of symbolic power, at other times clearly identified, such as formal and impersonal power.

In both approaches, in fact, the class is expressed through the school experience. In Willis, the counterculture of working-class youth consists of a collective practice that produces experiences and meanings penetrated by its structural conditions; in Bourdieu and Passeron, the school experience of university students is marked by the habitus and cultural capital that they owe to the class condition of their homes of origin. In other words, the cultural dimension of class condition is a fundamental measure in the reproduction of educational inequalities, promoting some and excluding others17. (Saraví, 2013, p. 86 - our translation).

Thus, Bourdieu highlights that positions in social spaces and class conditions are directly intertwined with the practices and properties that constitute a systematic expression of the conditions of existence and lifestyles. Such conditions condition and express behaviors, tastes and choices that give them a habitus of cultural styles and tastes that are legitimately accepted, creating a lifestyle from social structures which is socially accepted and demarcates the distinction and inequality between classes that can be seen in consumption, in the arts and in the modus operandi.

This condition guarantees members of the wealthy classes certain living conditions and cultural heritage capable of distinguishing what is socially legitimate in cultural terms; such a prerogative is denied to the subaltern classes, since the conditions of production, knowledge and ability to identify a work of art or playing a piano depend on years of studies and socioeconomic conditions which are not within the reach of the popular classes.

According to Magali de Castro (1998), Bourdieu approaches this question of power from the notion of a ‘field’, considering the field of power as a ‘field of forces’ defined in its structure by the state of relationship of forces between different power forms or species of capital. It is a field of struggles for power between holders of different powers; a game space, where agents and institutions have in common the fact that they have a specific amount of sufficient capital (economic or cultural in particular) to occupy dominant positions within their respective fields, face each other in strategies aimed at conserving or transforming this relationship of forces (Bourdieu, 1983, p. 375). According to him, the power exercised in the Education System is symbolic power.

For Bourdieu (1983), the field is a complex universe of objective relations of interdependence between subfields, at the same time autonomous and united by the organic solidarity of a true division of domination work, to a set of agents susceptible of being subjected to real partitions and linked by real and directly observable interactions or links. The field is a universe that has its own specificity and dynamics. As society advances, it differentiates into separate universes: the fields. Thus, for him, this power is almost magical, insofar as it allows him to obtain the equivalent of what is obtained by force thanks to the specific effect of mobilization.

It is at the heart of this power struggle that Paul Willis’ counter-school culture operates. The counter-school culture as a symbolic power is necessarily an act of confrontation and resistance to the constituted authority; it hides the correlation of force because it carries in itself elements of the ‘shop floor’, and is only exercised if it is recognized in the cultural environment experienced by the working-class youth, which, contrary to what many educators and the media in general classify as an undisciplined, rebellious and violent attitude. Counter-school culture is a form of identity that focuses on manual labor and the material relations arising from work that oppose “[...] conventional dominant ideology - particularly as mediated by the school - which are crushed, inverted or simply defeated by the counter-school culture” (Willis, 1991, p. 194).

It is evident that Willis’ thinking is not naive and it is not a matter of glorifying the working-class culture of manual work as a source of resistance to the dominant ideology within school, since we understand the appropriation of literate culture and knowledge historically accumulated to the group as fundamentally being of the working class. However, the author also highlights the limitations as well as the dominant ideology penetrations in the working class culture, namely individualism, the absence of a political organization capable of culturally organizing youth and the mediation of social relations as examples of this limiting process. Thus, the study carried out by Paul Willis allowed us to conclude that symbolic power is experienced in the day-to-day of schools and the counter-school culture practiced by students, having the dispute for authentic power in opposition to school authorities as its main characteristic, which as a group is also opposed to the formal arrangement offered by the school. Finally, the opposition present in the working class culture is towards informal, expressing itself in a peculiar way, precisely beyond the reach of the norm and the rule.

Final considerations

As a result of the work we developed with the PIBID group and the teaching center of Unesp having the work Learning to labor: How working class kids get working class jobs by Paul Willis as the theoretical reference, we sought to understand the disinterest and denial that occurs on the part of students in school education through sociological analysis, participant observation and constant dialogue with students via conducted activities, as inscribed in what Willis calls a practice of counter-school culture. We observed that the counter-school culture manifested by the students has resistance as a component of denial; it is manifested in different ways as neglect towards the teacher by ignoring them and demonstrating to have autonomy in searching for information on their telephones, information that many times was not related to the content taught, but which interested them momentarily. This situation implied inattention, intellectual lack of commitment, making reflection, dialogue and participation in activities unfeasible. We tried to understand and go deeper in understanding this resistance, and we were able to observe that much of it partly refers to the content taught being distant from the sociocultural reality of these students, a lack of involvement of many of them in the activities and the absence of youth protagonism itself. Many of these students are workers and live in a cultural horizon far from school content; for them, the school contents sound abstract and subjective, without connection to their daily lives, or concerned with the material situation and the pragmatic possibilities that the school can offer them; all of which was found in the questionnaires applied, in the group discussions and in the proposed activities.

As mentioned in the course of this article, we resorted to the theses of Pierre Bourdieu and Paul Willis in order to better understand the situation, as they have thematic affinities and have decisively contributed to reflect on the classroom space, the curriculum and school practices. Through ethnography, Paul Willis interpreted data collected in the light of Bourdieu’s concepts, the propensity of working class students to reinforce their condition of origin through the counter-school culture in order to deny the transmission of ‘formal knowledge’ that school offers them, which to a certain extent results in maintaining the dominant social order.

Contrary to a consistent curriculum capable of training young students leading them to a denaturalization process of social reality, the didactic material of the São Paulo government São Paulo faz Escola takes the opposite path and can be considered material which is explicitly distant from the sociocultural reality of the students. The material deals with concepts in little depth, the learning situations cannot carry out the didactic transposition, with examples detached from the reality of the students, being little elucidated and stereotyped, as is the case of the learning situation to discuss the concept of identity using superheroes from the Marvel universe. This criticism is not limited to the teaching material of the State of São Paulo, which involves bringing concepts closer to the sociocultural reality of the students; and the textbook itself would not fulfill such a role, given the regional and local differences in our country. Thus, any uniformity of learning situations would be harmful to this didactic transposition, which does not imply denying the need for a national curriculum, but rather demanding and fighting for adequate working and training conditions so that each teacher could produce their own didactic material and insert learning situations which are closer to their realities, which in the working conditions and precariousness of the teaching profession seems to me a somewhat distant future.

Finally, although Paul Willis emphasizes that the counter-school culture produced by students is a conscious and autonomous response to the imposition of school, on the other hand it does not have transforming content, as it does not have the breadth as a general political transformative movement of the school and society. However, although we use and agree with Willis’ theses, we observe that the school and teaching of sociology have a critical and questioning capacity when it allows students to reflect on their surroundings and make the necessary connections with their macro-sociological reality. We are not advocating the transforming character of a single discipline in the face of a broader structure of society, but from the experience we had, it is possible to adapt sociological knowledge to the sociocultural reality of students, producing a critical look at their reality and surroundings; such criticality is to observe social phenomena with a certain estrangement, and this is possible with the scientific knowledge and the instruments that sociology provides them (teachers/administrators) within a school which must be more open, democratic, broad and inclusive to young Brazilians.

REFERENCES

Arruda, M. A. N. (1995). A sociologia no Brasil: Florestan Fernandes e a “escola paulista”. In S. Miceli. História das Ciências Sociais no Brasil (Vol. 2, p. 107-231). São Paulo, SP: Editora Sumaré; Fapesp. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1983). Gostos de classe e estilos de vida. In R. Ortiz. Pierre Bourdieu. Sociologia (Col. Grandes Cientistas Sociais, Vol. 39). São Paulo, SP: Ática. [ Links ]

Castro, M. (1998). Um estudo das relações de poder na escola pública de ensino fundamental à luz de Weber e Bourdieu: do poder formal, impessoal e simbólico ao poder explícito. Revista da Faculdade de Educação, 24(1), 9-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-25551998000100002 [ Links ]

Cuche, D. (2002). A noção de cultura nas ciências sociais. Bauru, SP: Edusc. [ Links ]

Cunha, M. V., & Totti, M. A. (2004). Do manifesto dos pioneiros à sociologia educacional: ciência social e democracia na educação brasileira. In M. C. Xavier. Manifesto dos pioneiros da educação: um legado educacional em debate. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: FGV. [ Links ]

Fernandes, F. (1958). A etnologia e a sociologia no Brasil. São Paulo, SP: Anhembi. [ Links ]

Lahuerta, M. (1999). Intelectuais e transição: entre a política e a profissão (Tese de Doutorado). Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Limongi, F. (2015). Revista Sociologia. In R. E. Almeida, & I. O. P. Silva. As ciências sociais em revista: temas e debates da Revista Sociologia 1939-1966 (p. 153-177). São Paulo, SP: Editora Sociologia e Política. [ Links ]

Maia, D., Fresche, E., Santos, L. A. & Gomes, N. L. (2020). Contextualizando a obra aprendendo... Revista Mediações, 5(2), 211-231. [ Links ]

Mendonça, S. G. L. (2011). A crise de sentidos e significados na escola: a contribuição do olhar sociológico. Cadernos Cedes, 31(85), 341-357. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-32622011000300003 [ Links ]

Mendonça, S. G. L. (2017). Os processos de institucionalização da sociologia no ensino médio (1996-2016). In I. L. F. Silva, & D. N. Gonçalves. A sociologia na educação básica (p. 55-75). São Paulo, SP: Annablume. [ Links ]

Pimenta, M. M., & Schrijnemaekers, S. C. (2011). Sociologia no ensino médio: escrevendo cadernos para o projeto São Paulo faz escola. Cadernos Cedes, 31(85), 405-423. [ Links ]

Ramos, G. A. (1995). Introdução crítica à sociologia brasileira. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: UFRJ. [ Links ]

Santos, W. G. (2002). Roteiro bibliográfico do pensamento político-social brasileiro (1870-1965). Belo Horizonte, MG: UFMG; Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Casa de Oswaldo Cruz. [ Links ]

Saraví, G. A. (2013). De laexclusión a lafragmentación de la experiencia escolar. In R. B. Sant’Ana & P. Abrantes. Aprendendo a ser trabalhador: um encontro coletivo com a obra de Paul Willis (p. 79-100). Curitiba, PR: CRV. [ Links ]

Secretaria da Educação do Estado de São Paulo. (2014). Caderno do Aluno: Sociologia,(Ensino Médio, Vol. 1, 1ª série). São Paulo, SP: Secretaria da Educação. [ Links ]

Souza, L. L. (2019). São Paulo faz escola e o ensino de sociologia: trajetória e análise (Dissertação de Mestrado). Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Marília. [ Links ]

Vellei, A. S. (2020). São Paulo faz escola e (contra)formação de professores: ensino de sociologia em atividade? (Dissertação de Mestrado). Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Marília. [ Links ]

Vieira Junior, I. (2021). Torto arado. São Paulo, SP: Todavia. [ Links ]

Werneck Vianna, L. (1997). A revolução passiva. Iberismo e americano no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Revan. [ Links ]

Willis, P. (1991). Aprendendo a ser trabalhador: escola, resistência e reprodução. Porto Alegre, RS: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

10This work was financed by the projects of the Teaching Nucleus of Unesp and PIBID/Capes of an institutional nature and by the signing of an agreement between the secretary of the state of São Paulo, the University and, in the case of Pibid, with the funding agency.

11Alberto Guerreiro Ramos was a distinguished Brazilian sociologist from Bahia, born in Santo Amaro da Purificação, joined the staff of Iseb, became famous for his studies on the racial issue, public administration and the need to create a national sociology. Among numerous books and articles, Critical Introduction to Brazilian Sociology of 1957 and The Sociological Reduction of 1958 stand out.

12The Sociology discipline has dense and abstract content; when working on concepts, themes and authors, it is envisaged to analyze and understand society, its conflicts, its cultures and other aspects that involve the complexity of life in society. Thus, it is not an easy task to translate these questions to high school students, and it is necessary to adapt such knowledge to the sociocultural reality of the students. In addition to this issue, it is worth mentioning that other disciplines in the humanities area have a greater history in the curriculum than the Sociology discipline, marked by a long absence from the curriculum from 1942 to 2008.

14Something that is interesting to note in the bibliographic survey carried out by Souza (2019) is that there is significant material from studies on São Paulo faz Escola, but on a smaller scale involving specific disciplines. “In the bibliographic mapping, the volume of works with the theme of Sociology is much smaller than the works that involve other subjects of basic education. He understands that this occurred due to the relevance of the object of study and the fact that its performance and effects are still in progress” (Souza, 2019, p. 33). Despite the relevance of the object, the empirical survey reveals a gap in studies on the teaching material of the discipline of sociology of the São Paulo government.

15Pibid (Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação à Docência) was created in 2007 and coordinated by the On-site Basic Education Board of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes). Pibid works to stimulate teaching among undergraduate students and to value teaching, aiming to provide students who are in the first half of the degree a practical approach to the daily life of basic public education schools and the context in which they are inserted.

16This is the Capes/Unesp Agreement and the São Paulo State Department of Education under process no. 88887.697113/2022-00

17En ambos planteamientos además, la clase se expressa a través de la experiencia escolar. En Willis la contra-cultura de los jóvenes de classe trabajadora consiste em uma práctica colectiva que produce experiencias y sentidos penetrados por sus condiciones estructurales; en Bourdieu y Passeron, la experiencia escolar de los universitários está marcada por el habitus y el capital cultural que deben a la condición de clase de sus hogares de origen. Dicho en outras palabras, la dimensión cultural de la condición de classe es uma medación clave em lareproducción de las desigualdades educativas, promoviendo a unos y excluyendo a otros (Saraví, 2013, p. 86)

Received: January 29, 2022; Accepted: May 04, 2022

texto em

texto em