Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Acta Scientiarum. Education

Print version ISSN 2178-5198On-line version ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.45 Maringá 2023 Epub Oct 01, 2022

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v45i1.55512

TEACHERS' FORMATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

Guiding-executing dimension of teaching activity: an experience with the continuing education of professionals in Early Childhood Education

1Universidade Estadual do Paraná, Avenida Gabriel Experidião, s/n, 87703-000, Paranavaí, Paraná, Brasil

2Instituto Federal do Paraná, Capanema, Paraná, Brasil .

3Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Cascavel, Cascavel, Paraná, Brasil.

This article aims to portray and understand the training professionals in early childhood education in the municipal public education network in Cascavel - PR, their course, and the challenges of its continuity. For this, it is based on the Historical-Cultural Theory, especially in the Activity category, and presents reflective elements on the continuing education of professionals in early childhood education, inserting the teacher in teaching activity. The text socializes the formative trajectory advocated in the direction of forming trainees based on the experience unleashed in the municipal public school system in Cascavel-PR. In addition to listing some challenges in the training of professionals in this stage of primary education, which reflect, to a certain extent, the general educational problems, this article discusses some possibilities of action in the direction of qualifying the pedagogical work to be developed in early childhood education. Its proposal was the organization of formation based on four spheres, mobilizing different training fronts (teacher-trainers; team-SEMED, coordinators and coordinators of schools and CMEIs and early childhood education professionals), to collectively create conditions for a continuous and permanent formation, aim at the historical-cultural conception of education as the humanization of the subjects involved. Thus, in the course of continuing education, it is essential to form and create conditions so that actions and operations, through the process of planning and organizing teaching as a social meaning in teaching activity, acquire personal meaning and become a source of teacher self-development, ensuring the conscious character in the unity between the principles of orientation and execution.

Keywords: continuing teacher formation; child education; teaching activity

O presente artigo tem por objetivo retratar e compreender a formação dos profissionais da educação infantil da rede pública municipal de educação em Cascavel - PR, seu percurso e os desafios da continuidade desse. Para isso, fundamenta-se na Teoria Histórico-Cultural, especialmente, na categoria de Atividade e apresenta elementos reflexivos sobre a formação continuada de profissionais da educação infantil, inserindo-os em ‘atividade de ensino’. O texto socializa a trajetória formativa preconizada na direção de ‘formar formando’, a partir da experiência desencadeada na rede pública municipal de ensino de Cascavel-PR. Além de elencar alguns desafios no âmbito formativo dos profissionais dessa etapa da educação básica, os quais refletem, em certa medida, os problemas educacionais gerais, este artigo discorre sobre algumas possibilidades de ação na direção de qualificar o trabalho pedagógico a ser desenvolvido na educação infantil, cuja proposta foi a organização da formação com base em quatro esferas, mobilizando diferentes frentes de formação (professoras-formadores; equipe-SEMED, coordenadores e coordenadoras de escolas e CMEIs e profissionais da educação infantil), na intenção de criar coletivamente condições para uma formação contínua e permanente, mirando a concepção histórico-cultural de educação como humanização dos sujeitos envolvidos. Assim, no percurso de formação continuada, é fundamental formar e criar condições para que as ações e as operações, por meio do processo de planejamento e de organização do ensino como significado social na atividade docente, adquiram sentido pessoal e convertam-se como fonte de ‘autodesenvolvimento’ do professor, garantindo o caráter consciente na unidade entre os princípios de orientação e de execução.

Palavras-chave: formação continuada de profissionais; educação infantil; atividade de ensino

Este artículo tiene como objetivo retratar y comprender la formación de los profesionales en educación infantil en la red de educación pública municipal de Cascavel-PR, su rumbo y los desafíos de su continuidad. Para ello, se basa en la Teoría Histórico-Cultural, especialmente en la categoría Actividad y presenta elementos reflexivos sobre la formación continua de los profesionales en educación infantil, insertando al docente en la actividad docente. El texto socializa la trayectoria formativa propugnada en la dirección de formar aprendices, a partir de la experiencia desatada en el sistema de escuelas públicas municipales de Cascavel-PR. Además de enumerar algunos desafíos en la formación de profesionales en esta etapa de la educación básica, que reflejan, en cierta medida, la problemática educativa general, este artículo discute algunas posibilidades de acción en la dirección de cualificar la labor pedagógica a desarrollar en educación infantil, cuya propuesta fue la organización de la formación desde cuatro ámbitos, movilizando diferentes frentes de formación (docentes-formadores; equipo-SEMED, coordinadores y coordinadores escolares y CMEIs y profesionales de la educación infantil), con el objetivo de crear colectivamente condiciones de formación continua y permanente, con el objetivo a la concepción histórico-cultural de la educación como humanización de los sujetos involucrados. Así, en el transcurso de la formación continua es fundamental formar y crear condiciones para que las acciones y operaciones, a través del proceso de planificación y organización de la enseñanza como sentido social en la actividad docente, adquieran sentido personal y se conviertan en fuente de autodesarrollo docente, asegurando el carácter consciente en la unidad entre los principios de orientación y ejecución.

Palabras claves: educación continua del profesorado; educación infantil; actividad docente

Introduction

The continuing education of early childhood education professionals is recent as a public policy and, as a result, in the last two decades, concerning legislation, there is a set of national guidelines that contribute to direct this formative process: Resolution CNE/CP no. 1 (Brazil, 2002); Resolution CNE/CP no. 2 (Brazil, 2015); Resolution CNE/CP no. 2, (Brazil, 2019). Besides this legal support, influential researchers still discuss this theme from a critical perspective (Basso, 1998; Franco & Longarezi, 2011; Dias & Souza, 2017; Moraes, Lazaretti, & Arrais, 2018;). This article is structured from these theoretical-methodological reflections since the experience in acting in continuing education with early childhood education professionals5 has shown mismatches between theoretical guidelines and practical demands. The idea of constant updating, i.e., of investing in in-service training as a condition for improving the quality of public education, comes up against how this training is materialized in many institutions and municipalities. To comply with the legal determinations, there is a massive investment in seminars and lectures for large audiences, usually at the beginning of each semester of the school year, often organized to comply with legal determinations whose focus involves random topics, which have even reverberated in motivational lectures and qualify little or nothing the teaching work.

In the search to face this challenge and contribute to the teaching performance, this scenario provoked us to trace new paths and plan continuing education actions in unity with the principles of ‘orientation’ and the principles of ‘execution.’ These principles are anchored in the assumptions of the Cultural-Historical Theory, especially in studies on the category ‘activity’ from the elaborations of Leontiev (1978; 1988), which explains that the needs, motives, and tasks guide human activity before the surrounding reality, as a psychic reflection and forms of representation in thought, and the satisfaction of these needs is given through actions and operations, that is, the execution dimension.

In this formative process, we adopt teaching as a teacher’s activity and as “[...] a particularity in the general context of human activities, in the process of appropriation of cultural goods produced by humanity throughout history” (Moraes et al., 2018, p. 650, our translation). At the same time, teachers also need motives that mobilize them for their activity and to constitute themselves as subjects in the activity. In this sense, to insert the professional of early childhood education in activity is to mobilize needs, while forming motives is to act in the guiding dimension. What would these needs and motives be in professionals already working in early childhood education? The object of the activity of this professional is the organization of teaching; therefore, their motive must coincide with this object, and this involves mastering and mobilizing theoretical and pedagogical knowledge that materializes in actions and operations, such as the execution dimension. Given this, it is essential to train and create conditions for these actions and operations in the process of planning and organizing teaching and, thus, the social meaning of teaching activity acquires personal meaning and becomes a source of “self-development” for the teacher, ensuring the conscious character in the unity between the principles of guidance and execution.

Thus, this text explains some of the paths taken in the guiding-executing dimension for the continuing education of early childhood education professionals based on the experience in the municipality of Cascavel-PR. Thus, in advance, we clarify that this training process is ongoing and bet on the movement of longitudinal continuity anchored in the premise of ‘training by training’ in which the teacher, in their teaching activity, also trains themselves (Moraes et al., 2018). Therefore, this article aims to portray and understand the training of early childhood education professionals in the municipal public education network in Cascavel - PR, its course, and the challenges of continuing this process.

The experience of continuing education for early childhood education professionals in Cascavel: trajectories and perspectives

The provision of continuing education for early childhood education professionals in Cascavel-PR followed the historical and legal changes in the Brazilian scenario. Until 1999, this stage of primary education was linked to the Secretariat of Social Action, which was responsible for maintaining daycare centers with a welfare character. The professionals who worked with children from zero to six had no specific academic training; the position was called monitor. Concomitantly to this scenario, deliberations that would affect this conjuncture were already underway, such as the Federal Constitution of 1988 (Brazil, 1988), which guaranteed access to education as one of the fundamental rights of the child, and the promulgation of the Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional (National Education Guidelines and Framework Law) (LDBEN) under Law No. 9,394 (Brazil, 1996). Its Article 21, item I, defined Early Childhood Education as the first stage of primary education6. The conception of early childhood education advocated by the LDBEN, in its Art. 29, “[...] is the full development of the child up to six years of age, in its physical, psychological, intellectual and social aspects, complementing the action of the family and the community” (Brazil, 1996, our translation). Therefore, the referred Law, in its Art. 61, states that the training of teachers to work in primary education should be in higher education, in a degree course, admitting as minimum training the high school level, in the standard modality.

To ensure these legal prerogatives, in the early 2000s, the Municipal Secretariat of Education (SEMED) took over the administration of 25 daycare centers and, with the Municipal Decree No. 5,166, dated December 5, 2000 (Cascavel, 2000), these units were named Centros de Educação Infantil (Early Childhood Education Centers) (CEIs). Later, these units were recognized by the State Secretariat of Education (SEED) and renamed Centros Municipais de Educação Infantil (Municipal Centers for Early Childhood Education) (CMEIs), serving children from 0 to 3 (zero to three) years old in the daycare stage and from 3 to 6 (three to six) years old in pre-school7. In this transitional period, SEMED appointed a team composed of a teacher, a social worker, and a psychologist to reorganize the work already underway in the daycare centers. Despite all the implicit and explicit challenges, this period represented an essential step for the Municipal Network; however, it still lacked some legacy: there was a significant number of professionals who worked directly in Early Childhood Education (the Monitors) who migrated from the Secretariat of Social Action to the Municipal Secretariat of Education. In addition, there was also the entry of trainees in the Education area and only one teacher (appointed by SEMED), whose training was in middle school, with administrative and pedagogical duties, among others. This situation remained until 2014.

In order to follow current legislation, the municipality hired, through public exams, professionals with the position of educational monitor with a high school degree, later framed by Law No. 6,008 of March 28, 2012 (Cascavel, 2012). Its Article 1 changed the mentioned position to Early Childhood Education Teacher. In addition, Article 2 established the position’s duties: to perform and plan pedagogical activities in the Early Childhood Education Centers and educational programs and to carry out work related to the child’s care concerning hygiene and nutrition. In 2012, to meet the significant demand for Early Childhood Education, the position of support agent was implemented, with duties to assist the Early Childhood Teacher, given that this position does not require training in teaching.

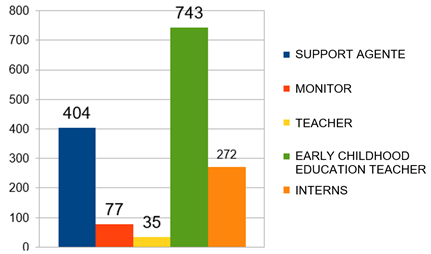

As of 2013, Municipal Centers for Early Childhood Education staff consisted of Monitors, Support Agents, interns, and Early Childhood Education Teachers, teachers, and the positions of director and pedagogical coordinator. In 2014, the Plan for the Position, Career, Salary, and Appreciation of the Teachers of the Municipal Teaching Network of Cascavel-PR was reformulated, contemplating the position of Early Childhood Education teacher, as set forth by the Fund for Development of Basic Education and Appreciation of the Teaching Profession (FUNDEB). The referred document, in Goal XII, guarantees continued training for education professionals and ensures, in Article 12, continued training for teachers and education professionals, respecting the theoretical and methodological conception of the Cascavel Municipal Public Education Network Curriculum of 2008 (Cascavel, 2008). In Figure 1, we observe that different professionals are working in early childhood education, with diverse training processes, which reverberates in the complex and contradictory possibilities of training and teaching activities to be faced in the continuing education process and the collective of professionals has faced this challenge for over a decade.

Source: elaborated by the authors based on data systematized in the document Plano Municipal para Infância e Adolescência (Municipal Plan for Children and Adolescents) - PMIA (Cascavel, 2019)

Figure 1 Professionals of Early Childhood Education in the Cascavel Public Education.

We consider how complex this scenario of early childhood education professionals is, in which this diversity of positions still presents many without adequate training and qualification for this activity. This is not a local problem specific to the municipality of Cascavel but a dilemma in many municipalities. It is important to clarify that, according to LDBEN no. 9,394/96 (Brazil, 1996), an education professional is one who, even without specific training, develops actions to support teaching (Moreira, Saito, Volsi, & Lazaretti 2019).

Moreover, this condition of the early childhood education professional without the proper specific initial training reverberates in a performance that contributes to the unfeasibility of a coherent and articulated pedagogical practice between the principles of guidance and the principles of execution. Thus, in the direction of continuing the process of qualifying them, SEMED instituted a Plan of positions, careers, remuneration, and valorization of the teaching staff of the Municipal Public Teaching of the of Cascavel (Law no. 6, 445, (Cascavel, 2014), ensuring their continued education through courses, meetings, seminars, symposia, conferences, congresses, and other improvement or training processes, when designated or called by the competent body, preferably during working hours, adding up to an hourly load equal to or greater than 40 hours annually, as provided in the aforementioned document.

Given these legal prerogatives regarding the continuing education of early childhood education professionals, the Municipal Teaching Network of Cascavel-PR initiated, in 2004, a systematic training process, guided mainly by the need to develop and implement a curriculum for Early Childhood Education. To ensure a theoretical and methodological unity, the studies, debates, and reflections were guided by the perspective of Critical Historical Pedagogy, materializing in the Curriculum for the Municipal Public Teaching of Cascavel.

To this end, since the implementation of the curriculum in 2008, there has been an investment in continuing education about the philosophical, pedagogical, and psychological assumptions that underpin the pedagogical curriculum proposal, organized through seminars and lectures with content involving the social function of the school, teaching and learning process, periodization of psychic development, as well as workshops and short courses to support the planning of school subjects. We understand that it was an advance to guarantee, according to the local legislation, these training processes and to direct the training from a theoretical and methodological basis in a critical perspective. However, mobilizing these professionals, training them with relevant content for their performance, and, at the same time, mastering the specific contents of the curricular components proved to be a challenge since, at that moment, the need for the curriculum was structured by disciplinary contents; however, there was not yet a solid understanding of the specificity of child development and the most favorable teaching actions for learning. Thus, the triad was fissured: the content to be taught was hierarchized, and the understanding of the child that learns and the appropriate ways to teach were secondary.

After a decade of this implementation, and following the theoretical debates in the area of early childhood education and in the normative apparatus, especially to meet the 2015-2025 Municipal Education Plan (Law No. 6,496 (Cascavel, 2015a) and Resolution CNE/CP No. 2 of December 22, 2017 (Brazil, 2017), which establishes and guides the implementation of the Common National Curriculum Base (BNCC), there was a need to review, expand, and update the Curriculum, prioritizing the critical-historical and cultural-historical conception.

Given this demand, in 2018, we became involved in the process of reorganizing the training of early childhood education professionals based on SEMED’s proposal, which occurred in a double movement: reviewing and updating the Municipal Curriculum of 2008 and organizing and acting in the continuing education of early childhood education professionals. In this, a problem emerged: if there is a curriculum, in a critical perspective in force for a decade, and there was also continuing education to subsidize the approach of the curriculum and instrumentalize the professionals, how is this theoretical and practical conception materialized and effective in the planning and teaching actions in Early Childhood Education?

Based on this concern, before starting the curriculum review and continuing education organization, we mapped the organization and pedagogical planning in school spaces by visiting some CMEIs. In this guided visit, we captured scenes of a pedagogical practice that locally elucidates mistakes in training professionals in early childhood education and perhaps in primary education in Brazil. They are mistakes that result from the mismatch between the results of non-specific training in the area of activity or the fragmented initial training, which reflect in the non-effectiveness of solid pedagogical practice and reveal the need to invest in continued training longitudinally, especially regarding the philosophical, psychological, and pedagogical foundations of the announced perspective. We captured, from this particularity, the teaching practices of schools and CMEIs in the municipality, which still showed some weaknesses in implementing a curriculum coherently and consciously, with teaching actions organized from commemorative dates and excessive records in the children’s notebooks aimed at training in reading and writing. The organization of the internal space of the classrooms had too much exposure to standardized tasks and a furniture layout that made the circulation of the children unfeasible since the tables and chairs occupied the centrality of the classrooms, arranged in rows. Although the external space of these visited institutions was ample, with different environments and proposals, we did not find children and teachers enjoying or occupying these places.

These scenes cannot be explained in isolation. It is necessary to understand that training the teacher as a subject of their activity that reflects and understands their actions and operations is a challenge, given that the process of initial and continuing education, hostage to discontinuous and fragmented policies, clear dichotomies between theory and practice, content and form, disciplinary content and pedagogical-didactic knowledge (Saviani, 2014). In addition, in early childhood education, we have not yet overcome the historical debt in relation to the varied facets of early childhood education professionals. With that, the “[...] persistence of the presence of professionals without adequate qualification and training presents itself as an old obstacle that negatively leads the history of this educational segment” (Moreira et al., 2019, p. 18, our translation).

In summary, it is necessary to overcome the dichotomy between the guidance and execution principles of early childhood education professionals. To face this challenge, Saviani proposes:

Against the various forms of manifestation of the pedagogical paradox, we understand that its solution demands a theoretical formulation that overcomes the excluding oppositions and manages to articulate theory and practice, content and form, as well as teacher and student, in a comprehensive unity of these poles that, opposing each other, energize and set in motion the pedagogical work (Saviani, 2014, p. 71, our translation).

We do not deny the difficulties of materializing coherent and socially referenced training since the teacher’s initial training is often given fairly and emptied of fundamental knowledge. The conditions of their precarious performance, crossed by antagonisms, immediate reforms, and the growing precariousness of the teaching work, make it impossible to rise to effective and conscious teaching activity. Moraes et al. (2018, p. 649, our translation) state that the “educational process and the teacher’s teaching activity are not always understandable by them since their motives do not always correspond to the social objective of their actions.”

Given this scenario, we developed a hypothesis: the guiding principles - needs, motives, and goals - do not correspond to the execution principles - the actions and operations. Thus, the motives that should correspond to the object of teaching activity do not consciously and coherently mobilize the teaching actions. For the Cultural-Historical Theory, the motive of the activity is what impels the subject to act and directs this action to satisfy a certain need, “[...] he main thing is that behind activity there should always be a need, that it should always answer one need or another” (Leontiev, 1978, p. 82). However, in the process of subject formation, different motives mobilize the subject: motives that are only understandable and effective. Often, the motives are only understandable, i.e., they are narrow, particular, and last for a short time under direct circumstances. For example, the teacher participates in a pedagogical training course just to get a certificate or a career progression, or does their lesson planning as a bureaucratic operation and not to expand their cultural training or as a need to better understand the field of action, i.e., really effective motives, which are more constant, act for a long time, and are not restricted to immediate and causal circumstances. However, these motives can act simultaneously, form a single system, and transform themselves. In other words, the teacher’s initial motive - just understandable - participated in the training to fulfill the workload and receive a certificate. Thus, their behavior could be not paying attention and not being affected by the content of the lecture, or having their attention is drawn to some aspect of the lecture, then some content begins to change their behavior and, based on this, the teacher is encouraged to participate in new courses and becomes aware of the role of training and study in the teaching performance; hence, the motives become effective. Leontiev (1988, p. 71) states that in this transformation of motives - from just understandable to effective - “An objectification of their needs occurs, which means that they are understood at a higher level.”

Given the above, it was necessary to explain what the motives that move teachers in their activity are or if, in fact, this activity has formed in these teachers. Thus, we organized a longitudinal continuing education proposal, betting on ‘forming by forming in activity,’ which started in 2018 and is ongoing. Here, we record the formative actions of the years 2018 and 2019. This bet intertwined the need to revise and update the curriculum, inserting teachers in directed and oriented studies, but mainly, to articulate the theoretical and methodological assumptions of Critical Historical Pedagogy and the Cultural Historical Theory with effectiveness in the actions of planning, organization, and didactic intervention of teaching practices. It became latent to put these early childhood education professionals ‘in teaching activity.’

Given this organization, we assume that the teacher’s activity is dependent on a theory that allows objectively systematizing the practice, i.e., theory and practice are two poles that form a unit (Moura, Sforni, & Lopes, 2017). This requires that teachers become aware of their actions and realize and understand the theoretical principles of the philosophical, psychological, and pedagogical assumptions underpinning the curriculum proposal to effect a coherent and conscious pedagogical practice. According to Moraes et al. (2018), in order to make the teacher’s teaching activity effective, it is essential to train and invest in “[...] the teacher’s study actions, which have as a fundamental content the appropriation of generalized fundamentals and procedures, that is, the teacher needs to appropriate both what they will teach and the means to accomplish such task” (Moraes et al., 2018, p. 645, our translation). In this continuing education proposal with early childhood education professionals in Cascavel-PR, we invested in study actions that would allow us to reveal the movement of the teacher’s thinking based on their conceptions of children, school education, and society, capturing the contradictions and theoretical-practical ruptures from the objective conditions. To capture these contradictions in the formative process of the teacher who works in early childhood education is to understand that their activity is regulated by the social situation of development in which they are inserted and that the possibilities of learning and training are dependent and codetermined by the subject-society relationship. This means that it is in and through the activity that the subject’s psychism develops, and this activity is formed in a living relationship between the person and the surrounding world, acting on nature, people, and things (Petrovski, 1985). In this sense, to form the teacher in activity is to act on their psyche and personality, transforming it in this process by interacting, experimenting, and establishing actual links with the object of their activity.

In the direction of mobilizing motives that correspond to the social objective of their action, we organized the formative process in four spheres, the first two of which were directly carried out with the direction and organization of the teacher trainers. The spheres are as follows: a) training of coordinators and coordinators of schools and CMEIs for theoretical-methodological deepening of an adequate organization of teaching in the perspective assumed by the collective; b) guidelines, studies, and systematization in the team-SEMED8, together with the teacher-trainers, for the on-site trainings of professionals of early childhood education of CMEIs and schools; c) the professionals from the schools and CMEIs, in addition to participating in the training sessions at the teaching units, took part in the study sessions organized by SEMED’s coordinators based on the curricular components, reflecting on and organizing the teaching plans based on the triad child-content-form; d) the school coordinators, based on the orientations, studies and discussions with the teacher-trainers, organized formative moments with the professionals in their teaching units, revising and revising texts, organizing study groups, collective syntheses and structuring plans and actions of educational intervention, in a theoretical-practical articulation. The last two occur as a dialectical process, in which the movement in the effectiveness of the training is carried out by the SEMED team and with the pedagogical coordinators of the teaching units.

As teacher-trainers, we act in a double movement. The first movement consists in training the school and CMEI coordinators based on the essential contents for working in early childhood education, anchored in the assumptions of the Cultural-Historical Theory and Critical Historical Pedagogy, with emphasis on the concept of the child and child development, organization of space and time, pedagogical planning, among others that are still in progress. Concomitantly, the second aims to invest in the SEMED team to train teachers from schools and CMEIs based on the specificity of each stage of early childhood education in relation to teaching content and ways of teaching that are more consistent with the learning child, i.e., planning and organizing teaching proposals according to the triad child-content-form.

In this direction, one of this proposal’s first actions was to mobilize the motives and needs of those involved (coordinators and professionals in early childhood education) in correspondence with the teaching content. Was it possible to form these motives to put the teacher into teaching activity through study actions?

To insert teachers into activity is to move them towards the objectification of teaching, mobilizing them for the organization of actions and means to perform these actions in a guided and intentional way (Moura et al., 2017). To this end, mobilizing and organizing these actions and operations through a learning-triggering situation “[...] necessarily aims at the appropriation of knowledge considered ‘relevant’ from a social point of view, so that the subject is equipped with theoretical, methodological, and ethical tools that provide their with full participation in the community to which he/she belongs” (Moura, Araujo, & Serrão, 2019, p. 423, their emphasis, our translation). In this sense, the starting point was to identify what could be a tension-generating problem in the social practice arising from the guided tours in the Early Childhood Education Centers, which could put teachers as subjects in activity. Thus, we elaborated a teaching episode (Figure 2) that contained a learning trigger situation capable of mobilizing the coordinators to overcome these misconceptions with the teachers to propose new teaching situations.

The presentation of this teaching case triggered the coordinators’ reflections, notes, and analysis, guided by mobilizing questions: did the proposed planning consider child-content-form? To what content did the proposed tasks correspond? Were they appropriate to the objectives and the periodization? Which contents or disciplines could involve this theme? From this collective debate, each participant had to organize this discussion and elaborate a didactic proposition that contemplated the theme in content form, pointing out the curricular subject or subjects. It is important to clarify that this teaching case is a fictional scene; however, it contained the elements of the teaching practice identified in the guided visits to the CMEIs and schools in the city, such as, for example, standardized tasks, appeal to commemorative dates, and stereotypical decoration.

Based on this problematization, the coordinators in each of their teaching units organized study groups with the professionals in order to mobilize each one to plan a teaching situation considering the triad: a) the child and the period of development; b) the content to be taught from a curricular component; c) methodological approaches and resources appropriate to the principles studied. From this triggering situation, the professionals revealed an incipient understanding of the triad, primarily the domain of the specific content of the curricular components, in order to propose teaching actions that promote and insert the child into the activity. We observed that this case mobilized motives in the professionals, putting them in activity, impelling them to organize actions and operations, and acting and training in the guiding-executing dimension. When planning and executing actions and evaluating the teaching and learning process, this proposal demanded that teachers resort to theoretical knowledge and principles, which became the driving force of their training. These training spaces, organized in the four spheres mentioned above, provided mental elaborations and real possibilities for teacher training and performance, allowing reworking, involvement, and new meanings about the teaching activity. According to Franco and Longarezi (2011), it is necessary to invest in different training fronts in a shared and longitudinal manner because the process of appropriation is only materialized

[...] as the teachers’ motives relate to the content of the action, and this has a direct connection with the concrete conditions of their teaching life. If the teacher’s relations with reality change in an attempt to meet his or her needs and interests, this means that the continuing education actions must also be reorganized in their teaching life. These actions start to make sense to the teacher because they mean something extremely valuable to their pedagogical and personal performance, in short, in the concrete social practice (Franco & Longarezi, 2011, p. 578, our translation).

In continuity, the SEED team carried out formative actions directed to professionals, with training in small groups of professionals from CMEIs and schools, identifying new learning-triggering situations for teachers through the planning of teaching actions, reflections, and proposals on the organization of the early childhood education space, with periodic meetings between the SEED team and school and CMEI coordinators, as well as periodic meetings with other professionals from these school units.

It is important to highlight that this formative sphere - the SEED team and the coordinators, in an effective relationship with the teaching units and their professionals - is still insufficient to ensure more accurate and coherent training with the theoretical conception in question, due to the very situation still being structured and to the significant number of professionals involved in this formative process, with diverse formative trajectories.

Therefore, we understand that the way forward would be to guarantee entry in the career of Early Childhood Education professionals and invest in their initial training in order to insert all these professionals in the condition of teacher, according to the legal and pedagogical prerogatives, because we also evaluate that it is possible to ensure that, in the inter-relations between the different professionals who work in the teaching units, there is sharing of experiences and studies, and this corroborates the possibility of ‘training by training.’

In addition, the teacher trainers accompanied the SEMED team in loco, directing the study groups of each curriculum component as an action to re-design the curriculum, and directed the SEMED team to the training demands in order to implement the work proposal on two fronts, mentioned in this article: the unity in the preparation of the text of the curriculum document and the effective teaching practice desired by the educational theory on the agenda. For the systematization of studies from the curricular components with the teacher-trainers, the meetings began in the first semester of 2019, with the areas: Art, Body Culture, Language, and Social Sciences. In this formative model, it was necessary to previously read theoretical texts on the process of periodization of child development based on the assumptions of the Cultural-Historical Theory and the meetings aimed at the process of reflection and development of teaching actions, in order to understand the theoretical-practical movement. This study that directed the discussions was fundamental to rethink the content-form relationship since the contents present in the curricular components need to be incorporated by the new generations in order to guarantee the humanization of the subjects, in this case, babies and young children. Thus, we argue that teaching in early childhood education should be guided by curricular components organized by teaching content, but the way to teach involves reflecting on the organization of space and time, the grouping of babies and children, and the resources and strategies most favorable to learning. These elements that correspond to the way of teaching are in the process of study and continuity in the longitudinal training proposal. This means that “[...] education does not transform directly and immediately, but in an indirect and mediated way, that is, acting on the subjects of the practice” (Saviani, 2008, p. 73, our translation). Therefore, we reiterate Sánchez Vazquez’s reflections, brought by Saviani:

Theory in itself [...] does not transform the world. It can contribute to its transformation, but for that, it has to come out of itself, and, in the first place, it has to be assimilated by those who will bring about such transformation with their real, effective acts. Between the theory and the transforming practical activity, there is a work of education of consciences, of organization of the material means and concrete plans of action; all this as an indispensable passage to develop real, effective actions. In this sense, a theory is practical to the extent that it materializes, through a series of mediations, what previously existed only ideally, as knowledge of reality or ideal anticipation of its transformation (Vàsquez, 1968 apud Saviani, 2008, p. 73, their emphasis, our translation).

Therefore, the necessary reorganization of the training process for early childhood education professionals is intended to shed light on the gaps in their initial and continuing education.

The studies carried out and the actions triggered so far allowed some reflections on continuing education from the theoretical and methodological framework adopted in this municipal network, among which it was possible to list the necessary recognition of some achievements already visualized: a) teaching as an activity of the professional in early childhood education taken in an increasingly conscious way, recognizing that its performance depends on actions of studies and training processes, in order to correspond to the educational purpose of the educational conception defended by the collective; b) the recognition that the content is an important component in the organization of teaching, but it is still necessary, in addition to the conceptual domain by the professional, to elaborate and effect teaching actions more favorable to learning and development of babies and children, that is, the triad child-content-form as a direction for planning and pedagogical intervention; c) overcoming practices of rigid adaptation to pre-defined schedules and routines, with the awareness of professionals, understanding the importance of welcoming and flexible schedules in the institutions, considering the specificity of babies, children and family; d) the organization of directed and shared actions between professional-child and child-child, with toys and structured and non-structured resources; e) the expressive decrease in the use of notebooks with printed and mechanical tasks, allowing the proposition of productive activities carried out by and with the child; f) the transformation of spaces as mere decoration for the child, with stereotyped and impoverished designs, for the organization of environments based on the productions made with and by the children, based on rich and diverse cultural experiences; g) from sterile spaces, with desks lined up, restricted to the internal use of the classroom, to the planning of rich environments for exploration, circulation, and diverse games, expanding the possibilities for the actions of teaching, learning, and development of the child.

Besides, as a premise for the continuity of the educational process, we are organizing reflections inherent to the areas of knowledge and the specific didactics that were distributed in curricular components to ensure the effectiveness of the reformulated curriculum concomitantly to this continuing education process. In this way, we are working on the need to build teaching proposals and didactic experiences based on the professionals’ proposals and how they formulate their planning and didactic interventions.

As a possible path, we are aware that there are still gaps inherent to the local historical particularity of the municipality, but with a portrait of the general problems in the Brazilian educational field, especially in Child Education, explicitly regarding the initial and continued formation of teachers. It is necessary to reiterate that this intervention occurs within a critical, historical-critical, and cultural-historical educational theory; therefore, it keeps specific characteristics that have already been listed in this text. On these premises, we defend a proposal for continued training and outline goals for continuity precisely because we bet on the becoming expression of our arguments, in which the “training” of professionals in early childhood education occurs through the “teaching activity.” In this path, we insert the professionals in teaching activity, and, for some, perhaps, we form it by creating new needs linked to object-oriented motives. Teaching, as an object, mobilized motives that required planning and performing actions and operations that corresponded to the activity. In this proposition, we visualize the interdependence between the guiding and executing dimensions materializing in the teaching activity of the professionals involved in this formative process.

Final considerations

The formative process in question is being put into effect; therefore, we present some provisional syntheses of this path that already point to some perspectives. Throughout this text, we have argued the emphasis on the need to maintain the continued training of early childhood education professionals, as well as the necessary articulation with the initial training. Hence, the demand is eminent that the training process should occur in a systematic and planned way, with adequate time and conditions, in a collective and articulated way with the different actors involved.

The process of continuing professional education goes through public policies and is materialized through different models and conditions. In this trajectory, we see that there are ways to organize this training in a more promising way, investing in the teacher’s teaching activity, inserting them as the subject of the activity, seeking to form new motives, and mobilizing the need for the appropriation of knowledge necessary for their performance based on problems arising from the concrete social practice. In this sense, by proposing the organization model based on the four spheres, as reported in the text, we mobilized different training fronts (teacher-trainers; SEED team, school and CMEI coordinators, and early childhood education professionals) to create conditions for continuous and permanent training collectively, aim at the cultural-historical conception of education as the humanization of the subjects involved. Investing in the group of early childhood education professionals ensures that new subjects equipped with theoretical and practical knowledge can inspire new actions and operations that promote learning and the development of babies and children.

From these significant advances, in this provisional synthesis, we evaluate that the continuing education proposal consisted of a challenge being developed within the discussions held by the group of professionals involved and, as we conceive that it is in the “training by training” that there are clues for the development of this educational process, we hope that this proposal will illuminate new propositions, in a guiding-executing dimension.

REFERENCES

Basso, I. S. (1998). Significado e sentido do trabalho docente. Cadernos CEDES, 19(44), 19-32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-32621998000100003 [ Links ]

Brasil. Presidência da República. Casa Civil. Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos. (1988).Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Brasília, DF. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm [ Links ]

Brasil. Presidência da República. Casa Civil. Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos. (1996). Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, DF. Recuperado de http://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/lei9394_ldbn1.pdf [ Links ]

Brasil. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. (2002). Resolução CNE/CP nº 1, de 18 de fevereiro de 2002. Institui as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica, em nível superior, curso de licenciatura, de graduação plena. Brasília, DF. Recuperado de http://portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/rcp01_02.pdf [ Links ]

Brasil. Presidência da República. Casa Civil. Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos. (2013). Lei nº 12.796, de 4 de abril de 2013. Altera a Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, para dispor sobre a formação dos profissionais da educação e dar outras providências. Brasília, DF. Recuperado de https://bitiurl.com/aOAQG [ Links ]

Brasil. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. (2015). Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de 1 de julho de 2015. Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a formação inicial em nível superior (cursos de licenciatura, cursos de formação pedagógica para graduados e cursos de segunda licenciatura) e para a formação continuada. Brasília, DF. Recuperado de https://bitiurl.com/Wrcph [ Links ]

Brasil. Conselho Nacional de Educação. (2017). Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de 22 de dezembro de 2017. Institui e orienta a implantação da Base Nacional Comum Curricular, a ser respeitada obrigatoriamente ao longo das etapas e respectivas modalidades no âmbito da Educação Básica. Brasília, DF. Recuperado de https://bitiurl.com/vmfbQ [ Links ]

Brasil. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. (2019). Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de 20 de dezembro de 2019. Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica e institui a Base Nacional comum para Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Formação). Brasília, DF. Recuperado de https://bitiurl.com/wxvHd [ Links ]

Cascavel. (2000). Decreto nº 5.166, de 05 de dezembro de 2000. Cria os centros de Educação Infantil. Cascavel, PR. Recuperado de https://leismunicipais.com.br/a/pr/c/cascavel/decreto/2000/517/5166/decreto-n-5166-2000-cria-os-centros-de-educacao-infantil [ Links ]

Cascavel. Secretaria de Educação. (2008). Currículo para Rede Pública Municipal de Ensino de Cascavel. Cascavel, PR: Ed. Progressiva. [ Links ]

Cascavel. Secretaria de Educação. (2019). Plano Municipal para Infância e Adolescência PMIA (2019-2024). Cascavel, PR. Recuperado de https://bitiurl.com/HuSQk [ Links ]

Cascavel. Câmara Municipal. (2012). Lei nº 6.008, de 28 de março de 2012. Dispõe sobre alterações no Plano de Cargos, Vencimentos e Carreiras do servidor Público Municipal, Lei Municipal n.º 3.800/ 2004 e na Lei Municipal n.º 4.212/ 2006, Plano de Cargo, Carreira, Salários e Valorização dos Professores da Rede Pública Municipal de ensino de Cascavel. Cascavel, PR. [ Links ]

Cascavel. Câmara Municipal. (2014). Lei nº 6.445, de 29 de dezembro de 2014. Dispõe sobre a reestruturação e gestão do plano de cargos, carreiras, remuneração e valorização dos profissionais do magistério da rede pública municipal de ensino no município de Cascavel. Cascavel, PR. [ Links ]

Cascavel. Câmara Municipal. (2015a). Lei nº 6.496, de 24 de junho de 2015. Plano Municipal de Educação - PME. Cascavel, PR. [ Links ]

Cascavel. Conselho Municipal de Educação. (2015b). Deliberação CME nº 001, de 17 de novembro de 2015. Altera o Artigo 5º e acrescenta o Artigo 8º - A da Deliberação nº 004/2013/CME/Cascavel. Cascavel, PR : CMEC. [ Links ]

Dias, M. S., & Souza, N. M. (2017). A atividade de formação do professor na licenciatura e na docência. In M. O. Moura (Org.), Educação escolar e pesquisa na teoria histórico-cultural (p. 183-210). São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Franco, P. L. J., & Longarezi, A. M. (2011). Elementos constituintes e constituidores da formação continuada de professores: contribuições da teoria da atividade. Educação e Filosofia, 25(50), 557-582. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14393/REVEDFIL.issn.0102-6801.v25n50a2011-07 [ Links ]

Leontiev, A. N. (1978). O desenvolvimento do psiquismo. Lisboa, PT: Horizonte Universitário. [ Links ]

Leontiev, A. N. (1988). Uma contribuição à teoria do desenvolvimento da psique infantil. In L. S. Vigotskii, A. R. Luria, & A. N. Leontiev, Linguagem, desenvolvimento e aprendizagem (M. P. Villalobos, Trad., p. 59-83). São Paulo, SP: Ícone. [ Links ]

Moraes, S. P. G., Lazaretti, L. M., & Arrais, L. F. L. (2018). Formar formando: o movimento de aprendizagem docente na oficina pedagógica de matemática. Obutchénie. Revista de Didática e Psicologia Pedagógica, 2(3), 643-668. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14393/OBv2n3.a2018-47439 [ Links ]

Moreira, J. A. S., Saito, H. I., Volsi, M. E. F., & Lazaretti, L. M. (2019). Valorização dos profissionais ou desprofissionalização na educação infantil? ‘novas’ e ‘velhas’ representações do professor. Revista Eletrônica de Educação, 1(12), 1-15. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14244/198271992663 [ Links ]

Moura, M. O., Sforni, M. S. F., & Lopes, A. R. (2017). A objetivação do ensino e o desenvolvimento do modo geral da aprendizagem da atividade pedagógica. In M. O. Moura, Educação escolar e pesquisa na teoria histórico-cultural (p. 71-100). São Paulo, SP: Edições Loyola. [ Links ]

Moura, M. O., Araujo, E. S., & Serrão, M. I. B. (2019). Atividade orientadora de ensino: fundamentos.Linhas Críticas,24(1), 411-430. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26512/lc.v24i0.19817 [ Links ]

Petrovski, A. (1985). Psicología general: manual didáctico para los institutos de pedagogia. Moscou. RU: Editorial Progreso. [ Links ]

Saviani, D. (2008). Escola e democracia. Campinas, SP: Autores Associados. [ Links ]

Saviani, D. (2014). O lunar de sepé: paixão, dilemas e perspectivas na educação. Campinas, SP: Autores Associados. [ Links ]

5In early childhood education, there are different professionals, especially in the experience described here, among which are monitors, support agents, interns, and teachers of early childhood education, and the positions of director and pedagogical coordinator.

6The LDBEN denominates 'daycare center' for children between 0 and 3 years old and 'pre-school' for children between 4 and 6 years old.

7With the Law No. 12,796, of April 4, 2013 (Brazil, 2013), in Article 6, the compulsory enrollment in Basic Education for children from 4 (four) years of age was regulated. To meet the provisions of this law, SEMED, through CME Deliberation 001, of November 17, 2015 (Cascavel, 2015b), ensured the attendance of children aged 4 (four) years in pre-school at CMEIs and Municipal Schools. In this period, there was a significant increase in enrollments in this stage of education due to children aged 4 and 5 (four and five) years old and due to the obligation.

8It is important to clarify that the SEMED in Cascavel-PR has a Pedagogical Department organized by a team of municipal pedagogical coordinators to advise and carry out the continuing education programs for all the professionals working in the Municipal Centers for Early Childhood Education and Municipal Schools that have classes for Elementary IV and V.

Received: August 29, 2020; Accepted: March 01, 2021

text in

text in