Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Acta Scientiarum. Education

Print version ISSN 2178-5198On-line version ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.45 Maringá 2023 Epub Oct 01, 2022

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v45i1.55295

TEACHERS' FORMATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

Pedagogical coordination: perceptions of school coordinators in a democratic management perspective

1Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia, Estrada Bem Querer, Km-04, 45083-900, Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, Brasil.

Resultantly from a master's research that aims to analyze the perceptions of school coordinators about the work of pedagogical coordination from the democratic management perspective as well as the challenges at carrying out collective work. The research was developed in the Municipal network of Education - Elementary School, in Itapetinga, Bahia, having as investigation subjects seven school pedagogical coordinators, four school managers and two technical coordinators. As a method of analysis, the study is based on dialectics, in the perspective of historical materialism. We appropriated the bibliographic research for the theoretical deepening of the object of study and, as instruments for data collection, we used documentary analysis and semi-structured interviews. The research results reveal, among other aspects, important points of reflection: the conditions of the coordinator to 'articulate' pedagogical activities within spaces that are not democratic; training can not be only the pedagogical coordinator duty, but requires an action of the state; the difficulties encountered by the coordinator when there are no working conditions and performance of their duties ensured by the government of the state.

Keywords: pedagogical coordinator; educational management; participation; collective work

Resultante de uma pesquisa de mestrado, este trabalho tem como objetivo analisar as percepções dos coordenadores escolares sobre o trabalho de coordenação pedagógica na perspectiva da gestão democrática, bem como os desafios na execução do trabalho coletivo. A pesquisa desenvolveu-se na Rede Municipal de Educação - Ensino Fundamental, em Itapetinga-BA, tendo como sujeitos da investigação sete coordenadores pedagógicos escolares, quatro gestores das escolas onde atuam os coordenadores pedagógicos e dois coordenadores técnicos. Como método de análise, o estudo pauta-se na dialética, na perspectiva do materialismo histórico. Apropriamo-nos da pesquisa bibliográfica para o aprofundamento teórico do objeto de estudo e, como instrumentos para coleta de dados, utilizamo-nos da análise documental e da entrevista semiestruturada. Os resultados da pesquisa revelam, entre outros aspectos, importantes pontos de reflexão: as condições do coordenador para ‘articular’ as atividades pedagógicas dentro de espaços que não se constituem democráticos; a formação não pode recair apenas sobre o coordenador pedagógico, mas exige uma atuação do Estado; as dificuldades encontradas pelo coordenador quando não há condições de trabalho e de desempenho das suas atribuições asseguradas pelo Estado.

Palavras-chave: coordenador pedagógico; gestão educacional; participação; trabalho coletivo

Como resultado de una investigación de maestría, este trabajo tiene como objetivo analizar las percepciones de los coordinadores escolares sobre el trabajo de la coordinación pedagógica desde la perspectiva de la gestión democrática, así como los desafíos en la ejecución del trabajo colectivo. La investigación se desarrolló en la Red Municipal de Educación - Escuela Primaria, en Itapetinga, Bahia, con siete coordinadores pedagógicos escolares y cuatro administradores escolares de la misma institución y dos coordinadores técnicos. Como método de análisis, el estudio se basa en la dialéctica, desde la perspectiva del materialismo histórico. Nos apropiamos de la investigación bibliográfica para la profundización teórica del objeto de estudio y, como instrumentos para la recolección de datos, utilizamos análisis documentales y entrevistas semi estructuradas. Los resultados de la investigación revelan, entre otros aspectos, puntos importantes para la reflexión: las condiciones del coordinador para ‘articular’ las actividades pedagógicas dentro de espacios que no son democráticos; la capacitación no solo puede recaer en el coordinador pedagógico, sino que requiere la acción del Estado; las dificultades encontradas por el coordinador cuando no hay condiciones de trabajo y el desempeño de sus funciones garantizadas por el Estado.

Palabras clave: coordinador pedagógico; gestión educativa; participación; trabajo colectivo

Introduction

At the end of the twentieth century, discussions around democratic issues were intensified. According to Silva (2011, p.2), "[...] democracy has come to qualify processes, activities or relationships based on the dialogue, participation, law and respect for diversity”. This point of view, according to the author, builds actions of belonging and strengthens conceptions of collectivity. In education, democracy and school constitute a path towards opportunizing interactions between subjects through educational practice, "[...] strengthening new culture and fundamental political-social relations for a democratic society" (Silva, 2011, p. 2).

It is possible to refer to the process of democratic educational management as a process of transformation through collective work, since, in the condition of public policy, it is capable of promoting the effectiveness of the principle of participation in the school context. It is possible as well, when talking about democratic management and the principle of participation, to refer to the importance of the work of the pedagogical coordinator as an effective possibility of involving the school community in decision-making, since it is up to this professional the role of participating in the planning, guidance, monitoring and mobilization to the effectiveness of the pedagogical proposal, in a perspective of collective work. According to Placco, Souza and Almeida (2012), pedagogical coordinators, in the school environment, in view of their attributions, play a decisive role in the process of articulation, formation and democratization of relationships in school, as they stimulate natural and essentially participatory practices in educational pedagogical practice, in an autonomous and also transformative way.

Thus, this article aims to analyze the perceptions of school coordinators about the work of the pedagogical coordination in a democratic management perspective, as well as the challenges in the execution of collective work. The research was developed in the Municipal Network of Education-Elementary School, in Itapetinga, Bahia, Brazil, having as research subjects seven school pedagogical coordinators. We appropriate the bibliographic research for the theoretical foundation of the studied object. We used documentary analysis and semi-structured interviews as instruments for data collection. As a strategy to ensure the anonymity of the research participants in the presentation and analysis of the data, we opted for the use of coded names. The research was registered at the Plataforma Brasil and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee through the academic point of view: 3.483.335. The theoretical foundation of this work is based mainly on the works of Bruno (2006), Gandin (1997), Mészáros (2002), Oliveira, Santos and Pereira (2015), Silva and Sampaio (2015), not dismissing other scholars whose contributions were necessary for the development of this research.

The study sought an approach to historical-dialectical materialism for data analysis, considering the following categories: totality, praxis, mediation and contradiction. Categories are concepts that reflect the aspects of the real field, as well as the relations existing and developed in this reality. In addition to the categories of method, which are universal, and specific of the historical-dialectical materialism, we used the categories of content of the Marxian work, labor, alienation and ideology. According to Masson (2012, p. 6), the content categories “[...] concern the specificity of the object investigated and the purposes of the investigation, with its due temporal cut and delimitation of the topic to be researched”.

Initially we present a brief discussion about the work of pedagogical coordination in the context of the collective work of the school, highlighting, the relevance to the democratic management process. Later we present an analysis of the data and the results of the research, taking into account all aspects observed and investigated, confronting conceptions and identifying contradictions.

Pedagogical coordinator and the collective work at school: theoretical considerations

The proposed model of democratic management, still far from the real purpose, is concerned with the strengthening of the mechanisms of participation in school units. This aspect is of undeniable relevance for the constitution of educational practices more consistent with the needs of the community. In the case of the pedagogical dimension of the school, the coordinator has the responsibility of developing an articulated work with the teachers and the entire school community.

The contribution of the pedagogical coordination in participatory actions is a process to be built in everyday life from the desire of the community that makes up the school unit, regardless of whether it is officially established. To build new perceptions and concepts, the coordinator “[...] needs pedagogical meetings and collective planning, so that, together with other teachers and the school's pedagogical team, they can reconsider their practices” (Oliveira et al., 2015, p. 150). Democratic management and participatory practices should be configured by the search for reflective and coherent paths with the school context. That way, it is essential to carry out collective work the recognition of some essential factors in this process: the planning of collective work; articulation between public policies and pedagogical practice; participation mechanisms; working with continued education and the achievement of autonomy.

Collective work is built, and for this, planning is required. It is necessary to think about the strategies for carrying out this task. This is not a step-by-step, a ready-made and finished road map, but rather the definition of articulations that stimulate participation and reflective positioning. According to Gandin (1997), following a script mechanically will only formalize the work, one must be attentive to changes, circumstances, problems and stimuli. The author also points out that it is necessary to take into account theoretical knowledge, in global terms, and the relationship with their understanding of educational organization.

Faced with a desire to make collective decisions, the work of the pedagogical coordinator needs to be organized and prepared to listen and collect the desires of the collective, and this does not imply accepting only what it is considered important, but gathering all the information, organizing it, systematizing it and bringing it to debate and decisions. Danilo Gandin (1997), when dealing with planning and collective work, emphasizes that, in this dynamic, it is not enough just to collect suggestions or make a selection of those that will meet the expectations and ideas of those who are coordinating the work. For the planning of a collective and participatory action, it is necessary to think of a way to gather, and not summarize, people's ideas.

From the perspective of the so-called democratic management, the action of the pedagogical coordinator enables the bridge between public policies and the real need for a school community full of conflicts and unrest. This is the great dilemma/challenge of the pedagogical coordinator, to promote articulating actions with democratic management principles, disassociating themselves from models impregnated in the educational management system, such as managerial management and shared management.

Thus, what is seen in schools are projects injected and plastered in the form of law, which, hierarchically and bureaucratically, must be executed under the mediation and with the articulation of the pedagogical coordinator. In addition, these projects are permeated by the interests of the neo-liberal market and capitalist links. This condition limits mobilizing actions, focused on the principle of participation. With little time for planning and articulation, these projects end up being developed in the school environment without reflective analysis or, when there is, without an alternative of non-execution.

In addition to what the bibliography points out about the role of the pedagogical coordinator, it is necessary to get rid of paradigmatic concepts, implemented by management makeup models, which focus on the control of results and the accountability of failure only to school professionals. This is an incontestable situation, since “in the field of educational organization and a prolific management, especially in relation to public policies, the managerial administrative paradigm, which seeks to transfer the logic to the specificity of the institutional culture of the school, the process and the business administrative pattern, centered on efficiency and effectiveness” (Silva & Sampaio, 2015, p. 969).

The pedagogical coordinator needs to develop his activities in the perspective of promoting actions in the school daily life that help overcome dissatisfaction and stimulate participation in its most concrete sense. It is about mediating the public policies implemented and the classroom work, carried out through the pedagogical practice. The coordinator has the role of mediator and articulator: discuss and reflect with teachers these policies, align them with the school's pedagogical proposal, the administrative reality and, at the same time, be sensitive to the dissatisfaction of a category that feels devalued, facing the precariousness of work.

Pires (2005), when analyzing the power relations in school daily life, focusing on the work developed by the pedagogical coordinator, highlights that the “[...] effective participation in the decision-making process at school supposes not only internal openness to participation at the political level, but also the autonomy of the school in relation to the central administrative bodies and the power structure of society, in which it is inserted” (Pires, 2005, p. 67). Democratizing power relations within the school can become, for the pedagogical coordinator, a possibility of building participatory spaces that will overcome centralized models of school organization. Actions that require the perception of the daily life of a school institution in an individual and collective perspective.

In the collective perspective, it is also evident the assignment of stimulating the mechanisms of participation in the school environment, committing to the effectiveness of a democratic surrounding. Decision-making at school must necessarily take place collectively. For this, it is necessary to understand that everyone who occupies and is part of the school dynamics must be given the opportunity to participate.

The work with a focus on change, carried out under the mediation of the pedagogical coordinator through collective work, will put at her/his disposal the mechanisms of participation in the bias of democratic principles through effective democratic management. The educational management is responsible for directing the process of organization and the functioning of institutions committed to human formation “[...] through a new knowledge that 'illuminates' the various democratic forms of conducting the educational process” (Ferreira, 2008, p. 104, emphasis added).

The activation of participation mechanisms in school spaces, such as direct election to principals, school boards, student unions, parents' associations, and class councils, is essential for the collective work. They are communication spaces that must be used and explored. Through them, it is possible to establish participatory and decisive relations, starting from the understanding of individual conceptions to collective ones and from collective conceptions to individual ones.

The administrative models that occupy the schools have directly interfered in the professional development of teachers, since they come from a neoliberal dictatorship whose “[...] educational reforms in Brazil are based on the principles of greater efficiency and productivity aimed for economic growth” (Brito, Prado, & Nunes, 2017, p. 168). It becomes evident in these models that articulating actions, based on the principles of participation, are not an interesting proposal.

Continuing education is a tool capable of building spaces for reflection, but it is the least performed assignment, because ordinary tasks takes up the time of the pedagogical coordinator. The moments of formation must be opportunized in the school institutions under the mediation of the coordinator. Continuing education is an important space for collective communication and the exercise of decision-making power, because “[...] it represents the possibility of deepening debates concerning the dilemmas and potentialities inherent in the educational process, [...]" (Silva & Sampaio, 2015, p. 966). The authors add that this space may represent the path to the reconquest of autonomy in an emancipatory perspective that provokes reflection, analysis and political transformations of the reality and professional practice, overcoming the domain of instituted power structures.

Overcoming the ideologies imposed by the power structure is a complex task. It requires critical and articulate action. The pedagogical coordination activity has attributions connected to this complexity and, therefore, is a challenging task. It is noteworthy that, "[...] considering the collective pedagogical work [...]”, it is possible to recognize, in this function, the “[...] own complexity of any action that intends the real and autonomous growth of people” (Bruno, 2006, p. 15). Garrido (2001) also expresses the complexity of the collective work that must be developed by the pedagogical coordinator with a view to social transformations, through the conquest of autonomy, by stating that “[...] this forming, articulating and transforming task is difficult, first, because there are no formulas ready to be reproduced [...]”. Second, because changing pedagogical practices is not just a technical task [...]" (Garrido, 2001, p. 9).

Thus, in this practice of action and reflection, it is necessary to work attentive to the transformations, without disregarding the following points: the context of democratic management as a form of organization of the educational work and the construction of new concepts; the understanding of the historical factors that promoted the principle of democratic management before a neoliberal policy; the overcoming of managerial or shared management models that become obstacles in collective work; the stimulus to the principle of participation through the mechanisms that are available for the school work, as a practice of democratic management; the appreciation of the function for the construction of professional identity, better defining and understanding their real attributions; the understanding of continuing education as a form of collective work and a moment of reflection about the pedagogical practice; the importance of the autonomy as a result of strengthening the participation.

Democratic management in the work of the pedagogical coordinator of the municipal Public School of Itapetinga, Bahia: the limits and contradictions

In pedagogical actions, the desire and needs of the entire school community are realized. They also materialize ideologies and establish links with alienating conceptions of business management models, with characteristics that neutralize participation as a political act. Parents, teachers, students, school managers, among other representatives of the school community, are fundamental pieces to overcome these models, however, they must be provided with spaces for collective action, rescuing, above all, autonomy as a democratic value. "In practical terms, however, we know that such a collective project is a very difficult goal to achieve. Personal and institutional barriers are not lacking” (Bruno, 2006, p. 14).

When the research subjects expressed their perceptions about the performance of pedagogical coordinators in the face of collective work, the evidence of the limits and contradictions of this practice in the school space have become evident, when it was observed that, among the activities performed on a daily basis, the direct work with participation mechanisms was not mentioned. It is highlighted that the class council and parent meeting were mentioned, but not as a collective participatory space and, yes, as a routine action (the class council at the end of every school unit, pedagogical shift, informative evaluation periods for parents, among others), aiming at the description of activities performed in the classroom by the teacher and performed by the school as a whole.

In the case of the class council, it showed relevance in the interviews, as collective and decision-making power, only regarding the student's school life, in aspects related to quantitative (grades) and qualitative (behavior) data. There is no time in the council to discuss ways and solutions to problems, which is configured more as a space for solving technical and informational issues than for discussion and reflection, as can be seen when the interviewee declares that: “[...] this class council that is often presented with a greater importance at the end of the year, when it is time to approve or disapprove [...]" (Force, 2019).

As for the issue of the parent meeting, it boils down to moments of transmission of information and compliance with administrative-bureaucratic procedures. This is proven in the testimony of an interviewee, when he states that “[...] from the parents, from the family, we have no participation. They only attend because they are invited, and no matter how much we insist, they do not have interest of contributing to the public school” (Strength, 2019).

The testimony shows the lack of 'interest' of the parents, however, according to Lück, Girling, and Keith (2012), the participation of parents in school, in most cases, is only desired to deal with technical and administrative matters. According to Bruno (2006), this resistance to participation, also on the part of education professionals, occurs because “[...] one of the difficulties of collective work is in the confrontation of expectations and desires of the subjects involved” (Bruno, 2006, p. 14). It is in this sense that the planning of collective work is necessary, with a view to provoking truly participatory actions. According to Gandin (1997), it is necessary to plan the moments of collective meetings and articulate strategies that facilitate the participation and the meeting itself, not only of people, but essentially of ideas, which need to be collected and discussed, before taking decisions. For this author, it is important not to disregard in the planning the aspects related to the reality of the school institution and the understanding of people about this reality and, therefore, to keep the planning flexible and adaptable to the various situations revealed by the community.

The research subjects described the activities that they considered to be planned with the participation of the community and the activities that they considered to be executed, as will be presented in Table 1, below. Before, however, it is necessary to highlight the testimony of an interviewee regarding the limitations, since he declares that: “[...] if the school community that we refer includes the janitor, lunch ladies, the cleaning staff, the principal, the coordinators, the teachers [...] I have to admit that I do not plan any activity including them all” (Balance, 2019).

It is also observed, in this regard, a contradictory position in relation to the previous statement, because an interviewee exposes: “[...] most activities are planned with the participation sometimes of smaller groups, sometimes of larger groups. We count in a lower percentage with the participation of families in these plans, due to a series of factors” (Determination, 2019).

The divergence presented in the opinions of the interviewees occurs due to the way each interprets and understands participatory processes. According to Gandin (1997), people quite associate participation in large plenaries and voting processes as a form of decision-making. According to the Author, This is an interesting process, however, it does not guarantee a transformative practice and a wide theoretical view. It is necessary to be attentive to the circumstances that involve collective moments, because, according to the author, the mistaken understanding of participation becomes a way for the authorities to preserve power and limits on the decisions of the people. This aspect may represent what Marx would call 'false consciousness', which 'legitimizes itself'. It is the expression of the strength of the dominant ideology that “[...] collects elements of reality and reconfigures them without establishing the links between this reconfiguration and the represented reality [...] it appears to us as an unquestionable construction [...] "(Hungaro, 2014, p. 54).

Although collective planning is expressed in the regulatory documents of pedagogical activities, the interviewees revealed the contradictions, emphasizing that there are few moments of planning and that, when they occur, they occur in light and succinct circumstances. Table 1 shows the activities that the coordinators are able to plan and execute with the help of the community.

Table 1 Activities planned and executed with the participation of the school community.

| The structure and adequacy of thePedagogical Political Project - PPP | Monitoring the entry and exit of students |

| The actions carried out during the school year: commemorative dates, evaluation calendar, among others. |

Meetings and communications to parents |

| Preparation and implementation of school projects | Projects with the help of teachers |

Source: Prepared by the researcher based on the interviews of the research subjects.

Some situations were pointed out as factors that obstruct collective planning, among them stands out the performance of the school manager: "[...] the manager is not very effectively involved with the pedagogical actions, I can say that the pedagogical issue is also one of the responsibilities of managers, even if he is not effectively responsible for what happens, but also needs this monitoring of the manager [...]" (Endurance, 2019).

In this statement, it is possible to perceive characteristics of the shared management model, in which each performs their function, without involvement in other demands, and/or characteristics of the managerial management model, whose director occupies the largest role in the hierarchy and only delegates activities. Whatever the model in the school is, the omission regarding the involvement in the pedagogical activities of the school, on the part of managers, can represent: a strong indication that education professionals still do not know their roles within a school unit that should function on democratic principles; the fear of making commitments, considering that the tendency of accountability injected by neo-liberal politics, in the process of decentralization, overloads school units and, therefore, managers prefer to delegate tasks to minimize the weight of responsibilities; form of control over the team, positioning itself only as a also perpetuating the form of organization implemented by capitalist market policy.

In this regard, once again, there was no mention of activities planned and executed through the articulation of important mechanisms of participation of a democratic management: the direct election of directors, the election of school boards, the organization of student unions, the articulation of parents' associations, among others. For Ferreira (2008, p. 71), “[...] communication between people with different backgrounds and skills, that is, between agents endowed with different competencies for the construction of a collective and consensual plan of action”. The participation mechanisms favor this communication and the gathering of the most diverse opinions and ideas. Mészáros (2002, p. 28) is blunt about participation, stating “[...] that all talk of sharing power with the workforce, or of allowing their participation in capital's decision-making processes, exists only as fiction, or as a cynical and deliberate camouflage of reality”. This conception of Mészáros (2002) helps us to clarify the contradictions existing in schools, when it is not possible to articulate the mechanisms of participation, nor the organization of the school under a democratic management model.

The interviewees were asked about the organization of the schools in which they worked, taking into account the context of democratic management. In Table 2 we present a summary of the statements.

It is possible to capture, in the testimonies, a strong sense of school organization and management linked to the so-called managerial pattern, presenting, hierarchically, the prevalence of the following structure: director, vice-director, pedagogical coordinator and educational advisor. None of the interviewees was able to correlate or cite the legal mechanisms of participation as integral components of the organization of school management.

Also about the school organization, when asked if they consider that the school where they work presents a model of democratic and participatory management, it was possible to see that the opinions were divergent. Table 3 presents the participants' reports on the issue.

Table 2 Organization of school management from the perspective of the research participants.

| Interviewee | Organization of school management |

| (Balance, 2019) | "The management of the school is organized within [...] I'm not going to call it a pyramid, but we have the direction, the vice direction and the coordination”. |

| (Determination, 2019) | “In the schools where I work the management is organized in direction, vice-direction, pedagogical coordination and educational guidance service (SOE in Portuguese)”. |

| (Endurance, 2019) | "Although the management team has theoretical knowledge about the role of the manager, the role of the coordinator, I realize that the team needs an organization. There is a confusion of roles, where the coordinator, SOE, management support and even the school secretary assumes and develops actions that are the responsibility of the manager, in this case it is the principal's responsibility [...]”. |

Source: Prepared by the researcher based on the interviews of the research subjects.

Table 3 Characterization of the school management from the perspective of research participants.

| Interviewee | School is, or is not, democratic and participatory |

| (Balance, 2019) | "I consider the management of the school democratic and participatory, only it is more democratic than participatory”. |

| (Determination, 2019) | “I believe that we have not yet been able to reach a percentage that allows us to characterize the management that, many times, is configured as participatory, and other times as democratic, the latter in less intensity”. |

| (Courage, 2019) | “If this type of management is democratic or participatory, I have a little doubt, between democratic or participatory. I prefer not to comment.” |

| (Endurance, 2019) | “I do not consider the management of the school democratic and participatory. Some decisions are made by the manager without being shared with the team. Despite spending practically all the time involved with the financial issue, the accountability is precarious, the programs and the resource that the school has are not exposed, the assets acquired are not presented to the community, the meetings are fragmented and with the purpose of collecting signatures”. |

| (Hope, 2019) | "Yes, taking into account the principles provided for in the law of guidelines and bases of national education (LDBEN in portuguese) [...] Another aspect of democratic management is the choice of school managers, however, it still occurs by indication". |

| (Focus, 2019) | “I believe that the direction of the school will be democratic, yes, because we are living in a time where everyone has a turn and a voice. Some refuse to participate, others think that it is not worth having an opinion... but decision-making is still centralized [...]”. |

| (Overcoming, 2019) | “I feel it will depend on the moment and the situation. In some moments it is democratic: everyone has a turn, they speak, they have an opinion, they decide. In some moments it is also participatory: we get everyone involved. However, in some moments it is managerial: no matter how hard one tries to involve everyone, the voice in a hierarchical way ends up prevailing”. |

Source: Prepared by the researcher based on the interviews of the research subjects.

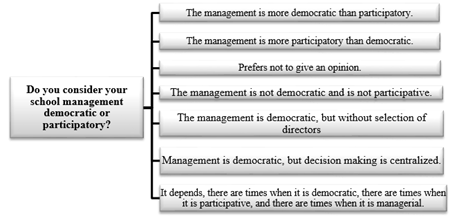

Table 3 shows a disagreement of ideas among the interviewees. The relevance of this information consists in the perception that, according to the conceptions presented by the coordinators, in the municipality of Itapetinga there is no definition of a management policy, especially regarding to the democratic management policy. The data reveal the following divergences, shown in Figure 1.

Source: Prepared by the researcher based on the interviews of the research subjects.

Figure 1. Democratic and participatory management in schools from the perspective of the interviewees.

It is observed that, in this aspect, each interviewee made a characterization of the functioning of the school management. This data implies that each school in the municipal network works from a management perspective that depends on the understanding of those who assume the functions of power. According to Ferreira (2008, p. 71),

Every organization that tries to implement and develop participatory practices lives under the constant threat of bureaucratic and authoritarian reconversion of its best efforts. The reasons for this are diverse: life experience of members, ideological overvaluation of traditional forms of management, political demands that are difficult to reconcile, etc.

The reasons highlighted by the author help understanding the diversity of perceptions mentioned in Figure 1, presented previewsly. In these statements was also possible to highlight the following reasons:

- The understanding that democratic management and participation are different processes, and the uncertainty between what is democratic management and what is participation;

- Lack of knowledge of the organizational processes of school management and the principle of participation or fear of taking a position, since they believe that they will be making a judgment of their colleague and not of an entire organizational structure, when they prefer not to give their opinion;

- The conviction that Democratic management processes have not yet been established within school units, as it confirms the centralization of decisions in the principal and the lack of transparency regarding administrative and financial issues with the community;

- The divergence in stating that management is democratic, however, makes a reservation that one of the main mechanisms of participation, the election of directors, has not yet happened;

- The contradiction in stating that management is democratic, even admitting the little participation of the community and the centralization of decision-making;

- The revelation that the management of the school is organized according to circumstances or convenience. The organization of the school will be characterized to depend on the results obtained before the decision making.

All these aspects imply a great challenge for the development of a collective work, because, according to Mészáros (2002, p. 1035), “[...] the idea of a fully conscious collective totalization, through class action and without the self-determined participation of its individual members, is a dubious proposition”. The composition of a management team that still cannot have clarity of management conceptions and principles of participation becomes a factor that prevents the overcoming of neoliberal ideological models and strengthens the control policy, management and shared models that do not privilege the construction of participatory conceptions and practices.

In the testimonies, the impacts of public policies on the work of pedagogical coordination were analyzed and, in this issue, the power exercised by the ideology of the ruling class over pedagogical practice and the situation of alienation of work revealed in the testimonies of the interviewees were also evidenced. The coordinator, as previously mentioned, plays the role of an articulator between public policies and pedagogical actions, however, they face challenges and obstacles every day, because of this mediation action, between public policies and pedagogical practice, only happens reflexively when a space with a proposal for school organization in the perspective of democratic management is provided for the coordinator, in which they are able to appropriate the mechanisms of participation, acting with autonomy in the face of control policies.

In an attempt to understand the difficulties of collective work, with regard to the projects that are launched by the government and the articulating conditions of the school coordinator, the interviewees answered if the projects implemented by the government are executed in the school unit, if they suffer changes; and if they suffer, they should explain the reason of the changes.

In terms of execution, the interviewees mentioned that there are many projects that reach the school and that most of them are executed. However, it is evident in the interviews that the main reason for execution is the obligation and bureaucratic fulfillment of the actions imposed hierarchically, as it is possible to observe when one of the interviewees states: "[...] we receive projects determined by the Secretary of Education, by the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC), which reach the school and must be executed” (Balance, 2019).

Projects are implemented in schools through educational policies that present a discourse aimed at improving the quality of teaching. Moraes (2014) makes a strong criticism by pointing out that these policies are loaded with content that serve to model people's behavior ensuring the maintenance of the capitalist mode of production and that the entire organizational structure, laws and various interpretations that follow educational policies “[...] carry precious criteria and have a practical function of restricting, guiding, prohibiting, marking limits (public/private) of the behaviors and activities of the subjects” (Moraes, 2014, p. 190).

As for the changes of the projects in the school units, the coordinators mentioned that, although they already arrive ready, they usually undergo changes. These changes aim to adapt the projects to the reality of the school. One respondent states that the projects "[...] are always read, discussed and adapted to the reality of the school unit (Determination, 2019)”. Another statement reaffirms this perception by stating: "[...] we have the project of the municipal network that needs to be fulfilled. It has a deadline and a completion date. They arrive at schools ready, but the coordinator has the autonomy to make some adjustments” (Courage, 2019).

In the exposition of the statements, it is possible to record some considerations, emphasizing the limits and contradictions. To the limits when they reveal that projects are executed because it is necessary to comply with the determinations. Contradictions when they affirm that they make use of autonomy to make the adjustments.

Autonomy, in the concrete reality of the interviewees, appears as a power of adaptation and not of construction and decision of actions. In this case, this ‘limited’ autonomy must be reconsidered in the face of the activities developed by the pedagogical coordinator and also the understanding that this professional presents.

When seeking the vision of autonomy in the work of the pedagogical coordinator, as an articulator of participatory actions that involve positions and decisions that significantly interfere in school dynamics and in the way the school deals with Democratic issues, we find two positions that also express limits and contradictions. First, a dubious vision, since, at the same time that they claim to have autonomy, they delimit situations in which they can or cannot decide. Second, an affirmative view, since they signal that their opinions are always requested when making decisions. It is possible to see these positions in the following statements.

Doubtful view: "[...] the relationship between the work of the coordinator and participation in school decision-making, with regard to decision-making in the pedagogical part, is not always [...] how do you say that? [...] is not always autonomous. Sometimes I don't have all this autonomy to solve these situations” (Courage, 2019).

Affirmative view:

[...] my director always counts on my opinion. Requested [...] on many things that were done in school via the secretary. The secretary came to the school and met with the employees, with the teachers, coordination, management, so that we could also visualize together a way of doing the work and surely they are always seeking our opinion so that we can do the best (Balance, 2019).

Interviewees who cited the lack of autonomy said that the performance of their duties is compromised. They report that it is impossible to develop a democratic school without the autonomy of its actors. This lack of autonomy is closely associated with the form of educational organization, in which the figure of the school manager is still centralized, and the obligation to comply with hierarchical determinations:

Unfortunately, as a coordinator, I do not have autonomy because the direction interferes a lot in some decisions, and I feel trapped sometimes in making decisions, and in trying to modify some things that I know are not right, so I do not have a hundred percent of autonomy (Courage, 2019).

There is no democratic management without autonomy and participation. For Silva and Sampaio (2015, p. 967), “[...] the autonomy of the pedagogical coordinator, in the process of management and organization of school work, occurs in this articulation between the potential added to continuing education, capable of collectively constituting critical reflection”. The most appropriate time to carry out these reflections is in the execution of the role of trainer, assigned to the pedagogical coordinator. In this situation, it presents conditions to appropriate the various communication spaces of the school, aiming at the critical analysis of reality. However, the interviewees cited the limitations of the Coordinator regarding the execution of the training role, revealing the secondary role of this assignment in school daily life, as in the following statement: “[...] with so many demands, inside and outside schools, formation has always been in the second or third plan, and we almost never manage to carry it out, although when doing complementary activities we seek to arouse some discussions and reflections, even if punctual” (Determination, 2019).

They emphasized that a Complementary Activity (CA)2 it is the best space for training and that the activities carried out in this space are not only informative, but also formative. This is evident when the deponent states: "[...] CA times are destined for this purpose (formation) and for the planning of the teachers. When there is a need to go further on a topic, these little formations occur through the reading of some material and discussions” (Focus, 2019). They also pointed out that the time of the CA is not enough to carry out training moments and mentioned some activities carried out in the time available for dialogue:

I don't have time for teacher training, it is complicated. Currently, to do a teacher training I need to suspend a class, because our CA is done daily and by area [...] we even use this time to discuss some problems they are having in the classroom, to help with some material they are needing, to choose activities for the week, for projects (Courage, 2019).

One interviewee referred to external training offered by the Municipal Department of Education (SME in Portuguese) or by other institutions, emphasizing the low motivation of teachers who consider trainers with little experience of educational practice and that the theoretical foundations of training have no practical applicability.

Within the school unit there are almost no training moments. Firstly, lack of time. We do not have time to be stopping and developing these actions because of the fulfillment of the two hundred school days with students. The lack of resources to hire professionals for training is the second point. The third is due to the lack of credibility of the team with the formations. According to them [the teachers], people who master the theory speak easily of things that they know that in practice gain another dimension (Endurance, 2019).

It is possible to highlight the existing contradictions and determinations in the work of the pedagogical coordinator in the face of democratic management. The CA time is cited as adequate for teacher training, under the articulation of pedagogical coordination, however, they reveal that the time available for the weekly activity is not enough to meet the demand of the training and everything else that the school dynamics require. The coordinator is unable to articulate training actions to be carried out at the time of the CAs. They end up boiled down to ‘informative’ moments. This situation awakens in the coordinators a constant feeling that they cannot effectively carry out their collective functions with the teacher and with quality. Faced with this situation, the coordinators end up positioning themselves in an indifferent way in relation to activities aimed at the democratic management supported by actions that encourage participation and collective decision-making.

Final considerations

The analysis of the perceptions of school coordinators about the work of pedagogical coordination from the perspective of democratic management, as well as the challenges in the execution of collective work in the Municipal Education - Elementary School Network in Itapetinga, Bahia showed that the coordinators develop other activities aimed at solving emergency and routine problems, diverting the focus of pedagogical work. The attributions based on participation, collective decision-making and continuing education of teachers end up in the background or are not even developed/executed. Hence the difficulty of working through the proposal of democratic school management.

The collective work becomes a great challenge for the pedagogical coordinator of the Municipal Education Network of Itapetinga. First, because not everyone recognizes collective work as one of the assignments. Second, because not enough time has been allocated for collective decision-making spaces. It is contradictory because everyone recognizes the importance of the mechanisms, but fails to implement them in practice. Many are still attached to traditional forms of management, due to the historical constructions of a capitalist society, the formation of professional identity supported by administrative structures, the guarantee of control and power, the difficulty of access to theoretical and critical knowledge on issues involving school management, the few conditions of spaces for training in a discursive and emancipatory perspective, among many other factors.

We assume that the challenge presented to the pedagogical coordinators corresponds to the possibility of creating democratic spaces that overcome uncertainties and indecisions and to recognize and make collective work legitimate, having the mechanisms of participation as a reference. We also emphasize the importance of understanding participation, not as a technical and bureaucratic activity, but as a political and transformative act.

In this study, we point out the need for training spaces of a political and pedagogical nature, both for coordinators and for managers and teachers. The coordinator is responsible for the construction of formative and collective spaces. It is also up to the coordinator to articulate communication and dialogue for the meeting of ideas, perceptions and aspirations, through a collective work that opens spaces for the most diverse conceptions and experiences, however, few opportunities are intended for this professional to perform this work.

We reflect on the size of the responsibility assigned to the coordinator before the function of articulator, trainer and transformer. We asked about the conditions of this professional to 'articulate' pedagogical activities from the perspective of democratic management, within spaces that are not democratic. We also showed that the coordinator needs to articulate a team, which has an identity, its political and social positions, its references and its choices. Regarding the training role, we emphasize training as a public policy that guarantees the right of professionals and that, in fact, can promote benefits to the formation of identity, such as from the point of view of career remuneration, salary recognition and professional valorization. This responsibility cannot fall only on the pedagogical coordinator, but requires an action by the Government. As for the transformative function, we emphasize the difficulties encountered for changes to occur when there are no working conditions and performance of their duties ensured by the state.

REFERENCES

Bahia, Estado da Bahia. Casa Civil. (2002). Lei nº 8.261 de 29 de maio de 2002. Dispõe sobre o estatuto do magistério público do ensino fundamental e médio do Estado da Bahia. Recuperado de https://governo-ba.jusbrasil.com.br/legislacao/85404/lei-8261-02 [ Links ]

Brito, R. S., Prado, J. R., & Nunes, C. P. (2017). As condições de trabalho docente e o pós-estado de bem-estar social. Tempos e Espaços em Educação, 10(23), 165-174. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20952/revtee.v10i23.6676 [ Links ]

Bruno, E. B. G. (2006). O trabalho coletivo como espaço de formação. In A. A. Guimarães, C. H. Mate, E. B. G. Bruno, F. C. B. Villela, L. R. Almeida, L. H. S. Cristov, ... V. M. N. S. Placo (Orgs.), O coordenador pedagógico e a educação continuada (p. 13-20). São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Ferreira, N. S. C. (2008). A gestão da educação e as políticas de formação de profissionais da educação: desafios e compromissos. In N. S. C. Ferreira (Org.), Gestão democrática da educação: atuais tendências, novos desafios (p. 97-115). São Paulo, SP: Cortez. [ Links ]

Gandin, D. (1997). A prática do planejamento participativo: na educação e em outras instituições, grupos e movimentos dos campos cultural, social, político, religioso e governamental. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Garrido, E. (2001). Espaço de formação continuada para o professor coordenador. O coordenador pedagógico e a formação docente. In E. B. G. Bruno, L. R. Almeida, & L. H. S. Cristov (Orgs.), O coordenador pedagógico e a formação docente (p. 09-15). São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Hungaro, E. M. (2014). A questão do método na constituição da teoria social de Marx. In C. C. J. V. Sousa, & M. A. Silva (Orgs.), O método dialético na pesquisa em educação (p. 15-78). Brasília, DF: UnB. [ Links ]

Lück, H., Girling, R., & Keith, S. (2012). A escola participativa: o trabalho do gestor escolar. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Masson, G. (2012). As contribuições do método materialista histórico e dialético para a pesquisa sobre políticas educacionais. In Anais do IX Seminário de Pesquisa em Educação da Região Sul (p. 1-13). Caxias do Sul, RS. Recuperado de http://www.ucs.br/etc/conferencias/index.php/anpedsul/%209anpedsul/paper/viewFile/96 6/126 [ Links ]

Mészáros, I. (2002). Para além do capital. São Paulo, SP: Boitempo. [ Links ]

Moraes, R. A. (2014). O método materialista dialético e a consciência. In C. Cunha, J. V. Sousa, M. A. Silva, & E. Bombardi, (Orgs.). O método dialético na pesquisa em educação (p. 79-96). Brasília, DF: UnB. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. O., Santos, J. J. R., & Pereira, S. M. C. (2015.). Estudo introdutório sobre a constituição da coordenação pedagógica no contexto da rede estadual de ensino da Bahia (Direc 20). In C. P. Nunes, & N. M. C. Crusoé (Orgs.), Formação de professores, currículo e gestão educacional (p. 137-155). Curitiba, PR: CRV. [ Links ]

Placco, V. M. N. S., Souza, V. L. T., & Almeida, L. R. (2012). O coordenador pedagógico: aportes à proposição de políticas públicas. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 42(147), 754-771. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742012000300006 [ Links ]

Silva, A. L. (2011). Gestão democrática: a ação do colegiado escolar como estratégia de democratização da gestão. In Anais do 25º Simpósio Brasileiro e 2º Congresso Ibero-Americano de Política e Administração da Educação (p. 1-17). São Paulo, SP. Recuperado de https://www.anpae.org.br/simposio2011/cdrom2011/PDFs/trabalhosCompletos/ comunicacoesRelatos/0055.pdf [ Links ]

Silva, L. G. A., & Sampaio, C. L. (2015). Trabalho e autonomia do coordenador pedagógico no contexto das políticas públicas educacionais implementadas no estado de Minas Gerais. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 23(89), p. 964-983. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40362015000400007 [ Links ]

Pires, E. D. P. B. (2005). A prática do coordenador pedagógico: limites e perspectivas (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas. [ Links ]

2A complementary activity is considered to be the workload assigned by teachers in effective class management, with the collective participation of teachers, by area of knowledge, to the preparation and evaluation of didactic work, pedagogical meetings and professional improvement, according to the pedagogical proposal of each school unit (Bahia, 2002).

Received: August 18, 2020; Accepted: April 15, 2021

text in

text in