Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Acta Scientiarum. Education

Print version ISSN 2178-5198On-line version ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.45 Maringá 2023 Epub Aug 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v45i1.65150

Articles

Mounting a starry sky: methodological posibilities with images in education research

1Universidade Tiradentes, Av. Murilo Dantas, 300, 49032-490, Aracaju, Sergipe, Brasil.

2Universidade Federal de Sergipe, São Cristovão, Sergipe, Brasil.

3University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada, Estados Unidos.

This article explores methodological possibilities when working with an image, since, as Foucault taught us, there is an unavoidable relationship of irreducibility from the image to the word, and vice versa. We aim to outline some methodological paths to think about an ethical pedagogy of looking at the image based on Foucault’s archeo-genealogical theories. To do so, we argue for the methodological power of an archeology embedded in the knowledge of images. This genealogical exercise allows us to think about a multiplicity of meanings about and with images anchored in Georges Didi-Huberman’s concept of montage where images as singular stars, when placed next to each other, allow for drawings of constellations that produce new spaces for the creation of thought, breathing zones and possible learnings of resistance. Drawing from the analysis of the Atlas Mnemosyne by the German art historian Aby Warburg, we use the term montage as a genealogical movement that seeks to emphasize the infinite work in front of an image, an exercise that allows us to think differently about what we are and what that we can become. In this scintillating ballet, a montage tries to apprehend the surviving and anachronistic dance that is the very historicity of the event that is the image - appearances, destruction and rebirths, or rather, an archeology of knowledge of and about the image that imposes a double condition on the order of knowledge: the inexhaustibility of the image and its abysmality. In its inexhaustibility we refer to the exuberance of its appearance, the way it opens us up beyond what is already known. It its abysmality we refer to, the dimensions of the image that are made irreducible to the provisional nature of the act of looking, a not-knowing which is insurmountable to our gaze in the face of the survival that make the images pulsate like living beings.

Keywords: image; montage; methodology; genealogy; education

A presente escrita é um esforço de realçar possibilidades metodológicas frente ao trabalho infinito diante da imagem, uma vez que, como bem nos ensinou Foucault, existe uma relação incontornável de irredutibilidade da imagem à palavra, e desta àquela. Com efeito, e a partir das teorizações arquegenealógicas foucaultianas, objetivamos delinear alguns caminhos metodológicos para pensarmos em uma pedagogia ética do olhar diante da imagem. Para tanto, argumentamos sobre a potência metodológica de uma arqueologia do saber das imagens, isto é, um exercício genealógico de pensar a multiplicidade de sentidos sobre e com imagens na tessitura do conceito de montagem proposto por Georges Didi-Huberman: os modos como as imagens, enquanto entes estelares singulares, nos permitem produzir, quando colocadas lado a lado, como em uma espécie de novos desenhos constelares, possíveis aprendizagens de resistências, de zonas de respiro, de espaços de criação do pensamento. Seguindo suas pistas, a partir de sua análise do Atlas Mnemosyne do historiador da arte alemão Aby Warburg, entendemos a montagem como um movimento genealógico que procura enfatizar o trabalho infinito diante de uma imagem, um exercício que nos permita pensar diferentemente o que somos e o que podemos vir a ser. Nesse bailado cintilante, a montagem tenta apreender a dança sobrevivente e anacrônica que é a historicidade mesma do acontecimento que é a imagem - aparecimentos, destruição e renascimentos, ou melhor, uma arqueologia do saber da e sobre a imagem que impõe à ordem do saber uma dupla condição: o inesgotável da imagem - a exuberância de seu aparecimento, o modo como nos abre para além do já sabido - e o abismal da imagem - as dimensões da imagem que se fazem irredutíveis à provisoriedade do ato de olhar, um não-saber que é intransponível ao nosso olhar diante da sobrevivência que fazem as imagens pulsar como entes vivos.

Palavras-chave: imagem; montagem; metodologia; genealogia; educação

El presente escrito muestra las posibilidades metodológicas al trabajar con la imagen, ya que, como nos enseñó Foucault, existe una relación insoslayable de irreductibilidad de la imagen a la palabra, y de una a la otra. En efecto, y a partir de las teorías arque-genealógicas de Foucault, pretendemos esbozar algunos caminos metodológicos para pensar una pedagogía ética de la mirada de la imagen. Para ello, argumentamos sobre la potencia metodológica de una arqueología del conocimiento de las imágenes, es decir, un ejercicio genealógico de pensar la multiplicidad de significados sobre y con las imágenes en el entramado del concepto de montaje propuesto por Georges Didi- Huberman: los modos en que las imágenes, como seres estelares singulares, nos permiten producir, puestas una al lado de la otra, como en una especie de nuevos dibujos de constelaciones, posibles aprendizajes de resistencias, zonas de respiración, espacios de creación de pensamiento. Es a partir del análisis del Atlas Mnemosyne del historiador de arte alemán Aby Warburg, que entendemos el montaje como un movimiento genealógico que busca enfatizar la obra infinita frente a una imagen, un ejercicio que nos permite pensar diferente sobre lo que somos y lo que podemos llegar a ser. En este centelleante ballet, el montaje intenta aprehender la danza sobreviviente y anacrónica que es la historicidad misma del acontecimiento que es la imagen -apariciones, destrucciones y renacimientos, o más bien, una arqueología del saber de y sobre la imagen que se impone al orden del conocimiento una doble condición: lo inagotable de la imagen -la exuberancia de su apariencia, el modo en que nos abre más allá de lo ya conocido- y lo abismal de la imagen -las dimensiones de la imagen que se hacen irreductibles a lo provisional como la naturaleza del acto de mirar, un no-saber infranqueable a nuestra mirada frente a la supervivencia que hace que las imágenes palpiten como seres vivos.

Palabras-clave: imágen; montage; metodologia; genealogia; educatción

Introduction

Faced with the blank page, stands the difficult task of producing writing, of dirtying not only the white space of the page, but also our hands, our bodies, and our subjectivities. In short, we ourselves, are moved and transformed by that which we write. Inspired by Michel Foucault, writing is problematized here as a way of mobilizing our thinking in a movement to transform who we are. In Foucault’s words, the writing of his books was constructed as an exercise in “[...] making [of] ourselves, and of inviting others to make [with us] [...] an experience of what we are, of what is not only our past, but also our present, [...] in such a way that we emerge transformed” (Foucault, 2013a, p. 192).

Following Foucault, is not in any way a new reflection in the field of education and writing as an alternative way of creating other ways of thinking, saying and, potentially, relating to ourselves and others (Fischer, 2005; Loponte, 2006; Meyer & Paraíso, 2012). In effect, this text is an exercise in defining a possible theoretical-methodological path to research with and on images in education, thinking of this path, first, as an ethical-political act that we undertake in the face of what in the world touches us and which, consequently, we transform into research objects. If we bet, as stated above, on writing as a way of involving ourselves, it is because it constitutes, for us, a task of imbuing each saying and through writing, we produce with the “[...] passion of the one who creates [...]”, as Rosa Fischer (2005, p. 117) invited us to think. Writing, therefore, would be an ethical-political act through which we can problematize how what we study “[...] has to do with our life, with what we love and that becomes living flesh in us” (Fischer, 2005 , p. 117).

In the field of education, image research was, as can be seen, in a more general panorama of GT 23 of ANPEd, deeply marked by the theoretical-conceptual lenses of cultural studies in education implicated in Michel Foucault’s power analysis. From a plurality of “[...] regimes of visuality (films, soap operas, electronic games, advertisements, game shows), images, understood as cultural artifacts, operate as powerful cultural pedagogies in contemporary times, transmitting knowledge and values, words and advice, which question us daily and, thus, teach normative ways of being and living” (Balthazar & Marcello, 2018, p. 9). In addition to this decisive mark in the field of education, we aim to suggest some theoretical-methodological outlines that allow us to propose writing that moves away from the educational dimension that disciplines bodies towards the proposition of the possible learning of resistance, of breathing zones, of spaces, of pulsating creations in and through images, since, “[...] a pedagogy that takes a position through, in and with the image is, therefore, a pedagogy that provokes us to ‘see abysses where there are common places’. It is a pedagogy that mobilizes us to learn not through consensus, but through conflict, deviation, difference” (Balthazar, 2019, p. 219, emphasis added).

In other words, we aim to contribute to research in education that has sought to “[…] stimulate new work ‘towards another ‘Foucault effect’ in research in education’ - beyond disciplines and the analysis of power, beyond the modes of subjectivization that ‘constrain us’, in addition to the practices of surveillance and punishment - but, obviously, without abandoning these aspects that are absolutely essential to Foucauldian studies” (Fischer & Marcello, 2016, p. 160, emphasis added). In this sense, and within the scope of research with images, this is an infinite work, as Foucault (1987)said when thinking about the relationship between the irreducibility of the image to the word, and from the word to that. After all, “[...] no matter how much you say what you see, what you see is never in what you say, and no matter how much you make it clear through images, metaphors, comparisons what you are going to say, what the place where they shine is not the one that the eyes roam, but the one that the successions of syntax define” (Foucault, 1987, p. 25). In effect, Foucault speaks of a force in the image, through words, that disturbs the very possibility of knowing how to name everything we see through the imperative of representation; “[...] not due to the incompetence of those who look, but due to the resistance of the image itself, which unfolds the sayings that are made about it always into new possibilities” (Marcello, 2005, p. 56). In terms of a question, we take on the challenge of problematizing: how to propose a methodology that translates, minimally, as the infinity of the ethical task of looking at the image? More specifically, how can we build a methodology that makes this task possible for us to grasp images precisely where they escape us, in the space where relationships of not knowing are woven into life’s potential?

From the perspective of these propositions, we launch ourselves into the almost silent work of rehearsing a methodology that places us on the border of action/passivity in the face of the embarrassment that the image causes us when it escapes, like a flash, the order of the word, of knowledge, of representation. To account for this, we argue about the outlines of an ‘archaeology of image knowledge’, that is, a genealogical exercise of thinking about and with images in the fabric of the concept of montage proposed by Georges Didi-Huberman, based on his reading of philosophers such as Aby Warburg, Walter Benjamin and, most decisively for us, Michel Foucault. Therefore, the methodological bet we make lies in how editing allows us to move away from the idea of the image as a singular fruit of a desire to know towards a concept of image that is irreducible to the order of discourse, suggesting to us the possibility of apprehending, even if contingently, that which in the images escapes our knowledge and calls us to transform our thinking.

An ethical choice in the face of the life and death of the image

To continue our discussion, we return to a question raised by Silvio Gallo (2016, p. 16): “[...] what can an image do?”. Taking into account the almost omnipresent place of images in our culture, as several authors have pointed out (Didi-Huberman, 2012; Alloa, 2015; Sontag, 2004), Gallo called on us to challenge the meanings so deeply rooted in Western societies, of an almost unavoidable correspondence between the concept of image and that of representation, under which the “[...] image informs, conforms, induces non-thought” (Gallo, 2016, p. 20). We are, therefore, faced with a methodological proposition about the concept of image that we seek to move away from here: the image as a cultural artifact that educates us only in a normative way - which, in Jacques Rancière’s terms (2015, p. 192), is a bet that “[...] the images would be nothing, just lifeless simulacra, and would be everything, the reality of alienated life”. Under this theoretical-methodological bet on screen, we would become individuals in front of images who are singularly subjected to the hegemonic truths of our time: “[...] when we are in front of an image - of art, of the media, of cinema, of theater - perceived as an instrument of established powers (biopower), a markedly dogmatic pedagogical relationship is established in the act of looking; teaching us knowledge and values under which our bodies need to build and conform” (Balthazar, 2019, p. 215).

Operationalizing a methodology with and about images under the imperative of representation says, as Georges Didi-Huberman teaches us, about our ethical choice, as researchers, to establish a will to power ‘over’ the image, in a movement that impoverishes its powers and meanings under the aegis of our desire for knowledge: “[...] it is understood that it is, once again, a matter of highlighting the gesture without which the [image] loses its poetic density and dries up into an immobile and dead discourse” (Didi-Huberman, 2017, p. 198). Taking a critical view of the idea of image as a mere representation, as a symptom of the normative order of things, is an exercise in outlining a different bet on the concept of image, so that we could speak in “[...] a thought-image [...]” in education: an image that, in its relationship with us, in the very act of looking, “[...] delirious and creates” as described by Silvio Gallo (2016, p 23). We speak, therefore, of an understanding of the image that privileges the dimensions that, in it, call us to hold tension in the truths of which we are subjects, which, for us, constitutes a gesture of opening ourselves to the pedagogical power of the image in “ [...] deconstruct and then renew our language and, consequently, our thinking” (Didi-Huberman, 2015a, p. 306).

How, then, can we guide ourselves, methodologically speaking, in the face of all the potential pitfalls of the multiple meanings of images? How to organize a way of knowing that does not take our perspective as researchers as the founding element, but rather as a passing element in front of an object that transcends us in terms of life and death? If, as Didi-Huberman (2012, p. 211) put it, researching with images means being “[...] faced with an immense and rhizomatic archive of heterogeneous images that is difficult to master, organize and understand, precisely because its labyrinth is made of intervals and gaps as much as of observable things [...]”, it is in the exercise of apprehending this archive in its games of life and death, of survival and destruction, that an exercise of imagination and montage is required that takes as the first locus the very historicity of the images: it is trying to create archeology that always calls us to “[...] risk placing, one next to the other, traces of surviving things, necessarily heterogeneous and anachronistic, since they come of separate places and times disunited by gaps” (Didi-Huberman, 2012, p. 211).

Talking about an archeology of knowledge of images irremediably requires us to focus on the concept of history proposed by Michel Foucault’s thought. Thus, taking Foucault’s genealogical method as inspiration for a methodology with and about images that is always inconsistent with the comfort of what is already known, takes us away from the place of fixity of “[...] history of historians [...]”, as described by Foucault (2013b, p. 284). Placing us, therefore, in the turbulent waters of a history ‘that will reintroduce the discontinuous into our own being’, in short, that ‘will divide our feelings; it will dramatize our instincts; it will multiply our body and oppose it to ourselves. Like laughter in the face of the pretensions of reaching the truth about the past, Foucault’s genealogy places, in many ways, the historical fact in erasure, suggesting we problematize the infinity of a myriad of events as a discontinuity that, in some way, touches us and calls us to think.

That said, we understand that Michel Foucault’s ambiguous genealogy allowed authors, such as Georges Didi-Huberman, to expand the lexicon of methodologies on the image, breaking, as we have already said, with the idea of a total history in the name of a history that privileges the discontinuity of events. In this lies one and the same task: that of “[...] ‘marking the singularity of events’, outside of any monotonous purpose, to spy on them where they are least expected and in what passes for having no history at all” (Foucault, 2013b, p. 273, emphasis added). In other words, Foucault proposed, by privileging singularities, to create history in a way that was far from the search for an origin: this place that would hold, unequivocally, any and all truths about the past.

In the context of image studies, the idea of origin would be close to Michael Baxandall’s (2006) proposals for analyzing the period’s perspective, as it privileges problematizing art from a social history perspective. In a critique of Baxandall’s (2006) proposal, Maria Lúcia Kern (2010) pointed out how this social art historian proposed that we operate with the idea of historically pertinent visual categories, so that, to understand an image, it would be necessary to bring it closer from a source belonging to an intrinsic reality, that is, produced in its time. As an example, we remember how Baxandall (2006) analyzed the work Dame prenant son thé (1735) by the baroque painter Jean-Baptiste Chardin, relating it to other productions from the same period: the empiricist tendency present in philosophy (like John Locke ) and in science (like Isaac Newton); because, for this social historian of art, “[...] there is a certain affinity between a type of thought and a type of painting” (Baxandall, 2006, p. 123).

Here, there is an overlap between the idea of a period perspective and some myths inherited from the conceptions that surrounded 19th-century historicism, placing images under the premise of euchronism: thinking about the past based on categories and analogies with sources from the period itself. Thus, the same temporal marker would agglutinate a given set of artists, of images, searching, above all, for an essence that such works would have, would share, as symptoms of the same time (Didi-Huberman, 2015b). In terms of Foucault’s analysis (2013b, p. 275, emphasis added), “[...] looking for such an origin is trying to collect what ‘was before’, the ‘that very thing’ of an image exactly suited to oneself; [...] it is wanting to take off all the masks to finally reveal a primary identity”. As already mentioned in the analysis by Didi-Huberman (2015b), this euchronic temporal premise is dear to iconology, especially linked to Panofsky’s dispositions. In it, the image is conceived as a remnant of a bygone time that, in some way, could be restored, in its totality and essential truth, through - borrowing the term from Foucault (2013b, p. 275) - the historian’s gaze who does not “[...] listen to history [...]” but rather believes it “[...] as metaphysics”.

As Georges Didi-Huberman (2015b) demonstrated, something is lost from the power of images the moment we pursue, in a unique way, euchronism, even though this is an important, fundamental, and insurmountable dimension. Therefore, Georges Didi-Huberman invited us to think about images inscribed in another time, oblivious to the incessant search of the art historian who frames the image as a symptom of its moment of creation, as a carrier of an essence of the context of its first appearance (as if it were, therefore, just an effect, the most obvious result of a certain context; the obsession with fitting images from the history of art to this or that period, linking them to this or that ‘movement’, would be one example of this for the author). In other words, Didi-Huberman proposed to show precisely the opposite: how images escape the canonical order of discourse in art history.

Therefore, Didi-Huberman bet that, in the images, there is a vocation for survival, making them irreducible to their time of production. As the French historian put it, the image, as a surviving form, “[...] disappears at a point in history, reappears much later, therefore, in the still ill-defined limbo of a collective memory” (Didi-Huberman, 2013a, p. 55). In order to better exemplify Didi-Huberman’s notion of survival, Gabriela Almeida (2016) shows us how the issue of the survival of images became a central key in Warburg’s thought, under the term Nachleben, so that survival refers to the resurgences or reappearances experienced by the image over time. It is, therefore, the survival of its own destruction that makes the image a constant mutation, a kind of trail of multiple times that have passed and displaced it. The survival of the image is, therefore, a temporal disorientation, challenging us to think in an anachronistic configuration of time (and, why not say, of history): “[...] anachronism would be, therefore, in a first approximation, a temporal way of expressing the exuberance, complexity, and overdetermination of images” (Didi-Huberman, 2015b, p. 22).

As an archive, the images are never already arranged. Rather, they are singular entities that, in their survival, in their complexity, we put together to compose specific meanings about our research topic. Thus, in Foucault’s way, seeing the singular intensities that we experience in front of each image is, therefore, betting that each image constitutes itself as a kind of star - in each one shines, in a very particular way, a story of life and death, a flash and an erasure of an apparition and destruction. In effect, we think of the methodology as a pedagogical gesture that invites us to transform the act of looking, “[...] into a kind of surrender, of letting oneself be carried away, of supporting a look in relation to the intensity of evidence” (Fischer & Marcello, 2016, p. 18).

Methodologically speaking, how can we problematize the fractures, the discontinuous rhythms, and the clashes of multiple pulsating times in the images? More than that, how can we bet on the anachronistic survival character of images to problematize art in its power to embarrass and confront us as a non-knowledge?

Mounting as a methodology, mounting constellations

It is necessary to return once again to archegenealogy, since it teaches us, as Foucault put it (2013b, p. 276), to “[...] laugh at the solemnity of the origin [...]” as an act of directing ourselves to a problematization of events that privileges “[...] their shocks, their surprises, the wavering victories, the poorly digested defeats” (Foucault, 2013b, p. 276). Therefore, the genealogical method is thought of here as permission to look at the images, no longer seeking to frame them in a possible linearity, but, rather, problematizing them in their movements of radical discontinuities and temporal ruptures. Therefore, what is appropriate is to look at the possibility of resorting to the emergence of images as singular events: “[...] this entry into the scene of forces, the leaps through which they pass from the backstage to the stage” (Foucault, 2013b, p. 282).

From a perspective, Didi-Huberman gave us clues, based on his analysis of the Atlas Mnemosyne by the German art historian Aby Warburg, for the construction of a genealogical path that allows us to problematize images in spaces that escape us, inviting us, thus, to a relationship of suspension of knowledge in the name of allowing ourselves to be grasped by the multiplicity of meanings, of memories that inhabit the images. According to this philosopher of the image, the time of the image is not the time of the history of science, of knowledge, but, as privileged in the Atlas, the time of its singularity as an event of multiple times: the past that the images emanate from them finds itself permanently reconfigured before the multiple gifts that look at it; facing the future, it is probably the one who will survive us (Didi-Huberman, 2015b). If the image is the element of duration and we are the transitory element, before the image we are placed on the edge of temporal fissures that make them irreducible to a knowledge that intends to name everything.

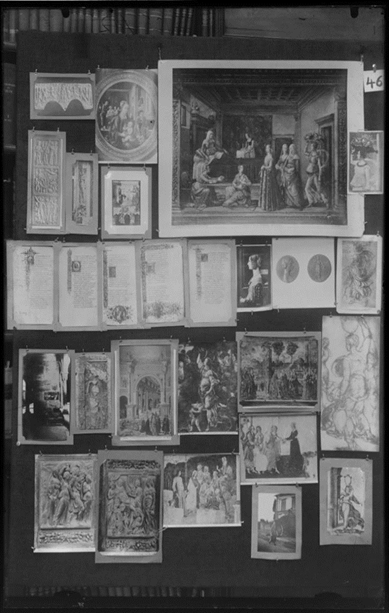

Through Didi-Huberman’s studies, we understand that Warburg thought, with his imagery Atlas, about the complexity of human life, the daily struggle faced with an ineluctable fragility of life; hence his refusal to fix the images in an orderly and definitive account. In short, the Atlas is a project that began in 1924 and brings together around 20 years of Warburg’s work, thus creating itself as a set of compositions between images apparently without temporal, cultural or geographic relationship. In the Atlas, 971 images were arranged and organized in the form of large panels, producing a kind of mosaic, in which the pieces (the images) communicate through a disjunction. The historian Daniela Campos (2016a), in one of her many studies on the thought of Didi-Huberman and Warburg, mentioned how the Mnemosyne Atlas did not have an endpoint due to the death of the German art historian, at which time it was composed of 79 panels: “[...] they were wooden screens, measuring 1.5 by 2 meters, covered in black fabric. Copies of paintings, photographic reproductions, pieces of periodicals, images and texts taken from graphic material were fixed onto these fabrics - thus organized based on thematic axes” (Campos, 2016a, p. 14).

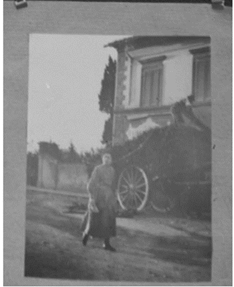

On plate 46 of the Atlas (Figure 1), for example, Warburg arranged, side by side, a series of 26 images brought together as anachronistic variations of the most prominent image on the plate, namely, the fresco by the Renaissance painter Domenico Ghirlandaio of a woman carrying fruit: there are “[...] images by Lippi, Raphael, Botticelli and even a photograph taken by Warburg of a peasant woman in Settignano [...]. The panel also highlights how literary expression plays a crucial and dialogical role in the history of Renaissance art” (Johnson, 2012, p. 100). Thus said, and according to the philosopher Giorgio Agamben (2011), Aby Warburg places, on the black background, images that are, at the same time, reproductions of other images, but original in their own right: Starting from a Longobard relief from the 19th century VII to a fresco by Ghirlandaio in S. Maria Novella (the latter depicts the female figure that Warburg jokingly called ‘Miss Quickbring’ and that, in an exchange about the nymph, Jolles characterizes as “[...] the object of my dreams which turns each time into an enchanting nightmare”) (Agamben, 2011, p. 64). The same panel also contains figures from Raffaello’s water carrier to a Tuscan peasant woman photographed by Warburg in Settignano.

For the philosopher, the board brings to life, in its mounting, the very meaning of the more general objective of Warburg’s work and which structures the very method of his Atlas: the gestures, the drapes of the fabrics or the hair of the well-known female figures ( Figures 2 and 3) and unknown (Figures 4 and 5)-which mostly inhabit plate 46-are symptomatic of the ‘movement of images’, their life as surviving entities, as entities with anachronistic historicities, which has haunted Aby Warburg’s thinking since his thesis The Birth of Venus.

Figure 1 Panel 46 of Bilderatlas Mnemosyne by Aby Warburg (1927-1929). The Warburg Institute, London (Warburg.libary, 2013/2016).

Figure 2 Portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni by Domenico de Ghirlandaio (1488), located in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid (Warburg.libary, 2013/2016).

Figure 3 Giovanna Tornabuoni in bronze medal by Niccolò Fiorentino (1485) (Warburg.libary, 2013/2016).

Figure 4 Drawing of a woman by Giuliano da Sangallo (Early 16th century), located in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence (Warburg.libary, 2013/2016).

Figure 5 Peasant woman photographed by Aby Warburg (No date), located at the Warburg Institute in London (Warburg .libary, 2013/2016).

In the same vein as Agamben (2011) on the figure of the pulsating nymph in the constellation that makes up plate 46, Daniela Campos provokes us to think about how the movement that pulses in the historicity of images - their genesis, their life, their destruction, their survival - is one of the main elements of Warburg’s image thinking:

[...]this inversion in the gaze is one of its great theoretical characteristics in the history of art. Warburg taught us to cultivate an observation of detail, eyes that do not necessarily look at what is most evident in the image: its main theme. In the thesis [on Botticelli’s Venus], Warburg slightly shifted his gaze to the floating locks of hair in the wind, to the fluid and draped fabrics. And it is there, in the formula of movement, in this fluent form, which he clearly recognized, the fundamental pathos of the image (Campos, 2020, p. 234).

In view of Plate 46, we cannot look for an archetype or the origin from which the images are derived, since “[...] none are original; none is simply a copy” (Agamben, 2011, p. 64). Thus, the nymph is, as a symptom of the living movement of the image, made of time itself: the nymph is “[...] a being whose form coincides punctually with its matter and whose origin is inseparable from its becoming, this is what we call time; which Kant, on the same basis, defined in terms of self-affection. [...]. they are crystals of historical memory, crystals that are ghosted” (Agamben, 2011, p. 65). Thus, and more than proposing an analysis per se of the images on Plate 46, what matters to us, more simply, is what they tell us about the method of mounting itself and what it invites us to do; that is, thinking of the nymph as a theoretical character by Warburg about the surviving and anachronistic character of images:

The nymph would be the character who would present this movement of the soul in her locks and dresses. Fixing the movement of life in an image was one of the great questions of the ancients that seemed to resurface in the Tuscan Renaissance. Human life is a fundamentally fleeting element. The image is, in the face of life, the element of survival. The certainty, or hope, we have is that the image will survive us. And how to present the movement of something as volatile as life in a more lasting materiality, be it stone, wood, or canvas. This is one of the deepest and oldest questions that man has faced with images. This is one of the deepest and most distressing questions that we seem to want to resolve with the nymph. Thinking of the nymph as a Warburghian theoretical character inscribes her exactly as a heroine from a distant time who always returns (Campos, 2020, p. 237).

We are, therefore, faced with a montage, as this work by Warburg can be called: a method that tries, in some way, to bring about the appearance, in the encounter of dissimilar images, of certain intimate relationships, of certain correspondences capable of providing a transversal knowledge of the inexhaustible complexity of those objects (Didi-Huberman, 2013b). It can be said that, through the Atlas, the German art historian proposed to compose another history of art:

The Warburgian atlas is an object designed based on a bet. The bet that the images, grouped in a certain way, would offer us the possibility - or rather, the inexhaustible resource - of a reinterpretation of the world. Linking the disparate pieces in a different way, redistributing their dissemination, a way of guiding and interpreting it, is certain; but also to respect it, to reassemble it without intending to summarize or exhaust it (Didi-Huberman, 2013b, p. 21).

Thus, the Atlas was an exercise in putting, where historicism had failed, thought in motion, a thought-through mounting. The driving principle of Atlas, of editing, is imagination. We do not speak of imagination as a free personal fantasy, but as an intense exercise that, in the act of looking, can “[...] set the multiple in motion, of not isolating anything, of making gaps and analogies emerge, indeterminacies and overdeterminations at play in the image” (Didi-Huberman, 2012, p. 155). In effect, imagination - like Warburg’s Atlas - allows us to assemble and disassemble images of plural forms, placing them in a permanent exchange capable of, using Foucault’s term (2013b), multiplying events.

Producing a story through editing is, perhaps, making another story. In effect, and far from syntheses and fictions that become truths, this other story requires us to assume something as singular as the images themselves that it puts into dialogue: the multiplication of the images’ meanings created at the moment they are placed next to each other. Imagination would then become the trigger for a (dis/re)assembly of the survivals of images, in a radical anachronization of history itself. More centrally, imagining the survival of the image through montage is, as Didi-Huberman (2015b, p. 16, emphasis added) from Warburg invited us, to problematize ‘the anachronization of history itself’ for an insurmountable issue: “[ ...] how can we account for the ‘present’ of this experience [in front of the image], the ‘memory’ that it evokes, the ‘future’ that it insinuates?” It is, therefore, a radical anachronization of time - in its three possible dimensions: present, past, and future - that history, in turn, finds itself anachronized.

The first dimension of this question - which is certainly inseparable from the other two, but let us examine, for didactic reasons, one at a time - refers to the ways in which ‘survival anachronizes the present itself’. In a study on the concept of montage, Daniela Campos (2017) showed how Didi-Huberman, through Benjamin’s thinking, demonstrated the ways in which we can only problematize the past through our present experiences, which are an ineluctable mark in the analysis of what we make of the remnants of the past that have come down to us. As a ‘dismantling’ of someone else’s structures (the past), the place of the now in our gaze undoes the very possibility of a history that seeks the origin, the essence, of a bygone time that would reside in images, in a kind of dialectic in that the past that resides in the image is, by us, seen in the present. To better understand this movement, let us remember, here, how Didi-Huberman (2015b) showed, with Benjamin, how this dialectical fecundity of the image is present in the optical model of the kaleidoscope, an optical toy that was successful in Paris in the 1820s. Inside the metallic box, the visual material of the kaleidoscope - arranged inside (pieces of glass, shells, glass, fabric) - is of the order of a past time, that is, like traces or traces of pasts that the image touched and that touched it. As “[...] blurs of time [...]” (Didi-Huberman, 2015b, p. 145) past tense, the dialectic of time operates through the gaze that, from the present, from our present, we cast on the image and that she, in her survival, casts upon us. In the relationship of the gaze, the polyrhythm of times - times gone by, times of now - is created from the encounter of this visual material dismantled within a kaleidoscope, that is, in the rotation of the device under our hands and our gaze, these traces of the past are reassembled in (or rather, combined with inhabiting) an image in the present. In other words, images from the past are ‘dismantled’ to be ‘reassembled’ by us in the present, forming a kind of ‘imaginative poetics of survival’.

We are, therefore, faced with the second dimension of the issue: ‘survival anachronizes the past’. We resort, once again, to another study by Daniela Campos carried out based on Didi-Huberman’s concept of survival:

[...] just like us, the individuals whose works we studied had different temporal experiments, memories and contact with different pasts. Diverse temporalities and multiple representations. ‘Artists manipulate times that are not theirs’. And the image is one of the many objects in which this plurality reverberates. ‘The image can be seen and analyzed in a ‘distemporary’’ (Campos, 2016b p. 53, emphasis added).

From the excerpt above, it is necessary to recognize the multiple times that inhabit each image. How each artistic production dates back not only to the time we look at it, but also to a past more distant from that of its emergence. There are no origins, only outbreaks of surviving times. It is inevitable for us to remember Foucault’s (2013c) text called Photogenic Painting, written in 1975, for the artist Gérard Fromanger’s exhibition. In it, Foucault (2013c, p. 350) made references to a tradition that, for some time, was lost in the visual arts, to that “[...] beautiful hermaphrodite [...]” of the “[...] image androgynous [...]” that combines a montage of images. When analyzing Fromanger’s method, the French philosopher told us how the artist went to the streets to take photos at random and, subsequently, in the darkness of a room, a projector relaunched the image on a canvas, at which point he applied the painting; it is an act of “[...] creating a frame-event on the photo-event [...], a focus of myriads of gushing images” (Foucault, 2013c, p. 355). In a movement that goes from the street to the photographic act and, from there, to the projection that leads to painting, Fromanger reveals the anachronistic movement of his images, as they are populated by heterogeneous times that make his paintings “[...] a place of passage [of so many other images that precede them], infinite transition, populated and passing painting” (Foucault, 2013c, p. 358). When ‘reassembling’ an ‘imaginal poetics of survival’ in the present, it is necessary to recognize that images do not speak singularly of their moment of creation - only of this or that movement, of this or that aesthetic -, but are made, at every moment, a locus of impure times that are memories of plural pasts before them and that, perhaps, survive our gaze stuck in the now.

Finally, then, we find ourselves faced with how ‘survival anachronizes the future’, because, if we disassemble to reassemble, joining images in this poetic imagery of survival is, in effect, an act of creating a new montage. When recalling Didi-Huberman’s words in a recent seminar, Daniela Campos (2017) offers us an analogy of montage to the mysterious figure of the fortune teller, since, with her deck of surviving images, the fortune teller seeks “[...] a premonition of the time to come” (Campos, 2017, p. 270). For the authors, therefore, Didi-Huberman provokes us to think about how to ‘reassemble’ different types of images through a particular approach to produce transformations in the images, in the sense of promoting, through a new ‘montage’, new meanings, a kind of ‘opening our eyes to something new’.

To better exemplify how survival anachronizes the future, we can bring to the discussion the film The Hours, produced in 2003, by director Stephen Daldry. In it, we certainly find a ‘present return’ (from the time of the film’s production) of memories from distant pasts (at least, the reference to the work Mrs. Dolloway written by Virginia Woolf, in the early 1920s, and to the lives of three characters from the book of the same name by author Michael Cunningham, from 1999: Virginia Woolf, played by Nicole Kidman; the character played by Juliane Moore, Laura Brown, who reads Mrs. Dolloway in 1949 Los Angeles; and Clarissa Vaughan, a character played by Maryl Streep, who shares, at the beginning of the 21st century, not only the first name of Mrs. Dolloway, but, above all, her trajectory organizing, over the course of a day, a party. ‘What a new montage’, however, do we see in the film? Of the many possible analyses, we chose a dimension analyzed by Guacira Louro (2017): despite the characters’ lives being distant in time, they share feelings, fears, impulses; they ‘all have affections and desires that transcend borders’. Each one of these women experienced a kiss, love with another woman, an affection that was hidden at the time of Clarissa Dolloway; to be lived in intensity at the time of Virginia Woolf; to be a liberation movement at the time of Laura Brown and, finally, to be a new normality at the time of Clarissa Vaughan. According to Guacira Louro (2017, p. 122), “[...] their kisses may have been more or less fortuitous, but they ended up becoming, in some way, perennial”. The kiss is the image that the montage of The Hours gives us, making us question the limits of gender and sexuality norms that determine which types of love are possible for us. Thus, Stephen Daldry’s film (2003) combines times of multiple experiences of images of lesbianism, allowing us in this new image montage - made possible by the dis/reassembly he made of Woolf and Cunningham’s books - to reach other meanings about affection and love. Ultimately, the montage emerges as an insurmountable warning before our eyes: it is possible, after all, to create a future where gender and sexuality power relations are radically diluted and transitory.

Usually, the surviving character of images is a fruitful element of the (dis/re)appearances of images, which in them becomes subject to “[...] remembrance [past], return [present], or even rebirth [future ]” (Didi-Huberman, 2013a, p. 72). Combining images through montage is, then, inscribing them in another time: not that of the linearity inherited by historicism, but that of an archegenealogy that insinuates itself through jumps, cuts, through the disjunction between images, at first, disparate, without any immediate relationship between each other. In doing so, the montage establishes other relationships between the images - relationships that are not given in advance, through knowledge outside them, but created, even theoretically, by the person who edits. In doing so, the (dis/re)assembly ends up producing another type of knowledge about and through images: an unpredictable knowledge, always subject to change (since the same image can give rise to other forms of knowledge, in the face of other combinations).

Warburg’s method is, therefore, an exercise in assembling, disassembling, and reassembling possible configurations on the panels, conceived by Didi-Huberman (2013a), as a work table for the researcher and the image researcher; finally, the panel is a metaphor for in support “[...] of encounters and temporary arrangements” (Didi-Huberman, 2013a, p. 18). Far from thinking fixedly about (dis/re)assembly under the metaphor of the panel is, despite being simple, a power to understand that methodologically we are, first of all, talking about an opening to new possibilities, new encounters, new configurations, new multiplicities through, in, and between the images: “[...] support for meetings, constituted by the table itself, as a resource of beauty or knowledge - analytical, by cuts, by reframing or by dissection - new” (Didi-Huberman, 2013a, p. 18).

Final considerations

In addition to the syntheses of representation, montage is, therefore, a genealogical movement that seeks to emphasize the infinite work faced with an image: that of bringing together (remembering the multiplicity of dis/re/montages) on a panel - in the case of research in education, the blank sheet of each page of a thesis or dissertation - images capable of “[...] ‘forming a constellation’ [...]” (Didi-Huberman, 2013a, p. 221, emphasis added ) that allows us to guide our thinking, in an exercise of thinking differently about what we are and what we could become. We are talking about a pedagogical gesture that emphasizes a displacement of the gaze that presupposes, in and through the (dis/re)assembly of a constellation of images, the Warburguian Übershen: “[...] seeing with a comprehensive gaze and making certain things or relationships stand out; but it also means not seeing, not capturing everything, omitting anything that, in the ‘aperçu’ itself, jumps out, escapes us in the depths of the unknown” (Didi-Huberman, 2013a, p. 243, emphasis added).

As a methodological process, therefore, (dis/re)assembly attempts to grasp the surviving and anachronistic dance that is the very historicity of the event that is the image - appearances, destruction, and rebirths -, in a genealogy - or better, an archeology of the knowledge of and about the image (Didi-Huberman, 2015b) - which imposes on the order of knowledge (because, ineluctably, we are producing knowledge, but, far from the knowing subject’s will to know, we inscribe ourselves in the space of a wavering knowledge, a knowledge that seeks to dance under and with the constellation of images) a double condition: the inexhaustibility of the image - the exuberance of its appearance, the way it opens us beyond what is already known - and the abysmal of the image - the dimensions of the image that become irreducible to the provisional act of looking, a not-knowing that is insurmountable to our gaze in the face of the survival that makes images pulse like living beings.

As stated, montage, as an archaeological work on images, it is not the search for great generalizations (implied to the order of image knowledge), but, rather, it is a concern with the unexpected that emerges from the encounter of (and with) images and which can constitute a rupture in the discursive order. Ultimately, mounting a constellation is an effort to transform ourselves through the dialogues we build between art, philosophy, and education, inviting us “[...] to place our thoughts ‘elsewhere’, in another way [...]” (Fischer & Marcello, 2016, p. 21, emphasis added) - which, for us, here, speaks to the urgent task of building a pedagogy with and about images that allows us to create ourselves as an unthinkable star that looks back at the sky.

Referências

Agamben, G. (2011). Nymphs. In J. Khalip, & R. Mitchell (Eds.), Releasing the image (p. 60-80). Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Alloa, E. (2015). Entre a transparência e a opacidade - o que a imagem dá a pensar. In E. Alloa (Org.), Pensar a imagem (p. 7-22). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Almeida, G. (2016). Por uma arqueologia crítica das imagens em Aby Warburg, André Malraux e Jean-Luc Godard. Significação, 43(46), 29-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-7114.sig.2016.115616 [ Links ]

Balthazar, G., & Marcello, F. (2018). Corpo, gênero e imagem: desafios e possibilidades aos estudos feministas em educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 23(1), 1-23. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782018230047 [ Links ]

Balthazar, G. (2019). Quando a pedagogia toma posição ou o que aprendemos com os homens do triângulo rosa?. Revista Periodicus, 11(1), 209-233. DOI: https://doi.org/10.9771/peri.v1i11.29218 [ Links ]

Baxandall, M. (2006). Padrões de intenção: a explicação histórica dos quadros. São Paulo, SP: Cia. das Letras. [ Links ]

Campos, D. (2016a). Um pensamento montado: Aby Warurg entre uma biblioteca e um Atlas. Revista Phoenix, 13(2), 1-20. [ Links ]

Campos, D. (2016b). A imagem e o anacronismo nas páginas da Garotas do Alceu. Dobras, 9(20), 53-67. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26563/dobras.v9i20.476 [ Links ]

Campos, D. (2017). Um saber montado: Georges Didi-Huberman a montar imagem e tempo. Aniki, 4(2), 269-288. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14591/aniki.v4n2.299 [ Links ]

Campos, D. (2020). A ninfa como personagem teórico de Warburg. Revista de História da Arte, 4(3), 225-245. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24978/mod.v4i3.4567 [ Links ]

Daldry, S. (Diretor), & Rudin, S., Fox, R. (Produtores). (2003). As horas [Mídia de gravação: Filme/DVD]. USA: Paramount Pictures. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. (2012). Quando as imagens tocam o real. Pós: Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes da Escola de Belas Artes da UFMG, 2(4), 204-219. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. (2013a). A imagem sobrevivente: história da arte e tempo de fantasmas segundo Aby Warburg. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Contraponto. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. (2013b). Altas ou a gaia ciência inquieta. Lisboa, PT: KKYM. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. (2015a). Falenas: ensaios sobre aparição. Lisboa, PT: KKYM. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. (2015b). Diante do tempo: história da arte e anacronismo das imagens. Belo Horizonte, MG: Editora da UFMG. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. (2017). Quando as imagens tomam posição. Belo Horizonte, MG: Editora da UFMG. [ Links ]

Fischer, R. (2005). Escrita acadêmica: a arte de assinar o que se lê. In M. V. Costa, & M. I. Bujes (Orgs.), Caminhos investigativos III (p. 117-140). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: DP&A. [ Links ]

Fischer, R., & Marcello, F. (2016). Pensar o outro no cinema: por uma ética das imagens. Revista Teias, 17(47), 13-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12957/teias.2016.24577 [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1987). As palavras e as coisas. São Paulo, SP: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (2013a). Conversa com Michel Foucault. In M. Foucault (Org.), Ditos e escritos VI: repensar a política (p. 289-347). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Forense Universitária. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (2013b). Nietzsche, a genealogia e a história. In M. Foucault (Org.), Ditos & Escritos II: arqueologia das ciências e história dos sistemas de pensamento (p. 271-295). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Forense Universitária. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (2013c). A pintura fotogênica. In M. Foucault (Org.), Ditos & escritos III: estética: literatura e pintura, música e cinema (p. 346-355). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Forense Universitária. [ Links ]

Gallo, S. (2016). Algumas notas em torno da pergunta: ‘o que pode a imagem?’. Revista Digital do LAV, 9(1), 16-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5902/1983734821766 [ Links ]

Johnson, C. (2012). Memory, metaphor, and Aby Warburg's Atlas of images. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Kern, M. L. (2010). Imagem, historiografia, memória e tempo. ArtCultura,12(21), 9-21. [ Links ]

Loponte, L. (2006). Escritas de si (e para os outros) na docência em arte. Educação, 31(2), 295-304. [ Links ]

Louro, G. (2017). Flor de açafrão: takes, cuts, close-ups. Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Marcello, F. (2005). Criança e o olhar sem corpo do cinema (Projeto de Doutorado em Educação). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. [ Links ]

Meyer, D., & Paraíso, M. (2012). Metodologias de pesquisas pós-críticas em educação. Belo Horizonte, BH: Mazza Edições. [ Links ]

Rancière, J. (2015). As imagens querem realmente viver? In E. Alloa (Org.). Pensar a imagem (p. 91-204). Belo Horizonte, BH: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Sontag, S. (2004). Sobre a fotografia. São Paulo, SP: Cia. das Letras. [ Links ]

Warburg.library . (2013/2016). Panel 46 - Nymph. 'Hurry-Bring-It' in the Tornabuoni circle. Domestification. Recuperado de https://warburg.library.cornell.edu/panel/46 [ Links ]

Received: September 25, 2022; Accepted: February 06, 2023

text in

text in