Introduction

An underestimated effect provoked by the virtual mode of schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic was the dislocation of teachers and students from a collective education project. Schooling practices became sophisticatedly individual and oriented to simplifying educational goals to the core elements of the official curriculum. It is in this sense that returning to high school after quarantine has been marked by emotional crisis, aggressiveness, and problems with navigating and negotiating shared spaces. However, this educational dislocation from the physical school has also made visible that contemporary youth are deviating radically away from simply filling out their educational project through school systems alone. High school students are framing educational projects rooted in practical benefits and claiming educational experiences that reflect other ways of knowing. This dislocation becomes more evident when one directs analytical focus on the educational projects of immigrant students and families in South American contexts because they embody a cultural diversity underestimated by the school system. Migration is life experience, life ambitions, life aspirations, and efforts to transform constraining social circumstances. All this places considerable pressure on domestic school systems to recognize the cultural diversity of immigrant students as a value to be integrated into formal education. The development of educational responses - that would address the complex dimensions of the diversity embodied in immigrant students’ life histories and the challenges that these present to domestic educational systems - constitute an area of investigation that has been insufficiently examined by educational researchers.

The purpose of this article is to theoretically frame a research design to address the cultural diversity of South American immigrant students as a fund of knowledge-the assumption that people’s life experiences, and transactions over the same, involve competencies and knowledge (Gonzalez, Moll, & Amanti, 2006) that drive the formation of identities marked by the transnational forces, connection, and imaginations (Burawoy et al., 2000). To accomplish this purpose, in the first section of this article, we present a summary of the Community Cultural Wealth model (CCW). Then, considering the relevance and limitations of applying CCW to the Global South scenarios, we explore two concepts used in postcolonial theory as elements to complement inquiries culturally and historically about the fund of knowledge in South-South migration scenarios. Next, we introduce a proposal for a qualitative research design that seeks to integrate the CCW and postcolonial theory frameworks through Critical Discourses Analysis (Fairclough, 2003) and Testimonios, a counter-storytelling technique (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). Finally, in the concluding section of the article, we share our reflections on the implications and potential contribution of the research design to a reimagination of the study of cultural diversity and agency of immigrant students in present-day educational contexts.

The Community Cultural Wealth: a model to counter the deficit thinking ideology

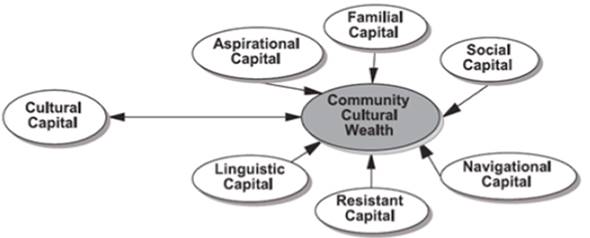

In her article, ‘Whose culture has capital’, Tara Yosso introduces scholarly readers to The Community Cultural Wealth (CCW) model, arguing for a framework that would systematically recognize and apply heuristically the working notion that a Community of Color both constitutes and retains and produces cultural knowledge with "[…] aspirational, navigational, social, linguistic, familial, and resistant capital” (Yosso, 2005, p. 78) (see Figure 1). Tara Yosso extends Pierre Bourdieu's concept of cultural capital by honoring the cultural practices and asset-based values of communities in contexts of migration or mobility that exercise permanent adaptability in navigating and negotiating societies. The CCW model points out that when the cultural capital theory is articulated to or applied to the specific case of Chicanos or Latinx groups in the US, the knowledge experiences of these groups remain underestimated. In this context, Yosso (2005) provides a culturally situated model which includes six cultural capitals that address the experiential knowledge of communities of color, honoring the cultural practices and asset-based values of communities in contexts of migration or mobility that existentially require and apply practices of permanent adaptability in order to navigate and negotiate societies.

The aspirational capital is related to the resiliency of Brown and Black social subjects in their confrontation with oppressive realities by nurturing hopes and dreams in the future and articulating new forms of cultural action and the creation of possibilities (Gángara,1995 as cited in Yosso, 2005). Linguistic capital addresses the value of bilingual education, cultural language, and the context of Communities of Color. This dimension also retrieves a strong oral tradition of knowledge that connects generations in the community and advises students on how to navigate schools. The third capital, the familial capital, aims to strengthen the community's well-being; it recognizes an extended family unit that can include the nuclear family (parents-children) and other generations or blood affiliations. The familial capital applies to communitarian institutions as well, such as clubs and churches. This capital promotes consciousness of care and decreases isolation-related problems. Social capital, instead, aims to connect the community and to provide them with resources such as emotional support to navigate society's institutions (Stanton-Salazar, 2001 as cited by Yosso, 2005).

The navigational capital recognizes students' inner skills to pass through educational scenarios of hostility marked by racism, fewer educational opportunities, inequality, and a dominant culture. Additionally, navigational capital identifies the student's agency as a bridge between institutional constraints and community development. Finally, the resistance capital values the oppositional knowledge developed by communities through several strategies to take cultural pride and thus resist violence and oppression. All said, the Community Cultural Wealth model extends and diversifies Pierre Bourdieu's concept of cultural capital by pointing to a range of assets that elevate People of Color's trajectories and focusing analytical attention on agency and cultural maneuverability. In this way, CCW helps counter deficit thinking ideology so deeply embedded in educational policy and research practice.

Deficit thinking works as a dominant normative framework that constrains theoretical and empirical efforts to retrieve Brown and Black People’s experiences by assuming students and parents of color are limited to White dominant societal values. Generally, in mainstream education policy and research, Latinx students have been too glibly associated with educational failure founded on the stereotypical assumption of the absence of parental support for the schooling process and cultural barriers, such as the lack of the English proficiency level demanded by the school (Solórzano, 1997). In response to deficit thinking, Rocha (2020) explores how consejos (advice) of Latinx parents with first-generation female students can shape educational goals that encourage persistence in obtaining a higher education degree. In her study, Calderon-Berumen (2020) delves into the role of Latina immigrant mothers as educators who bravely confront the prevailing cultural norms in educational environments. Thus, the CCW responds in depth to deficit thinking by exploring alternative types of agencies and resistance and by taking into account the experiential knowledge of Latinxs. CCW,therefore, opens a research and policy avenue that foregrounds inquiry into the conjunctures of these communities and the world and the dynamic resources and forms of action that define their encounter with dominant institutions, more comprehensively validating their histories and production of knowledge.

Examining the notion of community in CCW model

Yosso firmly situates CCW in a notion of community rooted in what Rocha (2020) defines as educational familismo. That is, the fund of knowledge students derives from their families through practices such as cuentos, and consejos to wisely navigate educational settings. The family plays a double function by organizing the mechanism of the experiential-knowledge to produce the assets of community wealth. Secondly, racial classification has placed peoples, from different continents and cultural development, in a racial classification that allows the development of liberalism, governance, and colonialism as modern racism (Lowe, 2015). This racial/ethical classification has minoritized the no-white groups by setting up the color line myth to align the global economy and individualistic values. For instance, the Model Minority Myth (MMM) addresses the racial classification to highlight the seemly assimilation practices of Asian American to get success in US. All of this is in contrast to African American groups that are depicted as failures in assimilation practices (Walton & Truong, 2022). As we explained in the first section, the CCW is far from addressing the systemic oppression of minoritized groups; still, what we want to stake is that placing community's ideas in familial interactions tends to reproduce an analysis of assumptions associated with the cultural heritage that not always responded in that direction. At this point, we consider that some annotation about the overlapping of community and familismo in the CCW model.

The notion of community according to people’s singular origin is complicated and contradicted by the Latin American context since our bodies have been marked by a colonial production of mestizaje and the development of national identities as peripheral versions of modern states. Rather than an ethnic-racial development of identities around the notion of community, Latin America remains open to the intersection of multiple projects: from the dominant western mainstream notions of civilization to indigenous schemes, which have interwoven over periods of silence and struggle. Likewise, postcolonial aesthetics, literature, and political projects, where racialized differences find room to transgress power structures (Dimitriadis & McCarthy, 2001). In effect, Latin America has been embedded in projects that create a peripherical understanding of modernity, therefore, community.

The second aspect of CCW's notion of community that we want to discuss is a theoretical issue provoked by the current global migration pattern on a regional scale, like South-South migration. Sadly, Chile's mainstream discourses produced by media and the government have codified transnational migration for the last twenty-five years as a dangerous reality for the national labor market and the increment of delinquency, despite the fact that Chile remains with the intermediary level of migration in Latin America. In this sense, it is difficult to identify immigrants as communities with funds of knowledge because the resentment operates in the articulation of mainstream discourses (Dimitriadis & McCarthy, 2001) in which racism and immigration are combined to reinvent projects of control over immigrants who are seen as transnational others in the local context. The mediation of immigrant life projects through discourses of poverty and racism drives back possibilities of honoring the experiential knowledge carried by the migration experience. All said, we suggest that researchers and policymakers complement their practices with more dynamic attention to rethinking the concept of Community. This rethinking of policy and research approaches to education, especially bearing upon the marginalized, should therefore deploy a more systematic understanding of the idea of the multiplicity that persists in the global context.

Some concepts from postcolonial theory complement CCW in South-South migration educational research

The postcolonial theory represents a cumulative body of theories committed to unveiling and contesting colonialism and neocolonialism practices in the ongoing relationship between the metropolis and periphery centers. Postcolonial theory attends to cultural and historical agencies against colonialism but takes as a central organizing concern the experiences of subaltern actors, their histories, and expressions of modernity (McCarthy, Giardina, Harewood, & Park, 2003). Postcolonial theory is geographically situated in the global relationship between the Global North, Global South, and Orientalism. It exposed imperial strategies of domination has paved the way for a cultural and intellectual examination of the nature of racism, colonial control, and its violent tactics (Go, 2016). From these relationships, the postcolonial reflection advocates turning up dominant beliefs that third-world ways of modernity are failed historical projects. Instead, it seeks to examine power asymmetries that frame center-periphery relationships considering multiple directions, where the agency of subalterns can indeed cave and transform metropolitan cultures and domination relationships. Disciplinary theoretical and methodological moves become more decisive in the coarticulation of postcolonial theory to cultural studies; In the field of educational research, postcolonial theory offers valuable insights into managing cultural and identity processes that are influenced by dominant ideologies and subalterns in educational settings and school knowledge. In framing an educational research design, this section reflects on the contribution of the notion of multiplicity and concrete study to place the CCW model as an organizing analytical framework for examining the dynamic entailment of South-South migration in the education fortunes of subaltern and marginalized immigrant youth.

Multiplicity

Considering Hall's (1989) notion of cultural identity, multiplicity is related to incomplete iterations between peoples' funds of belongingness (i.e., race/ethnic heritage of home countries) with their aspirational desires (i.e., social mobility process in host countries) conflating a common past with future spaces of reinvention. This iteration, from a postcolonial perspective, is productive in the sense that it allows immigrants to negotiate a different way of belongingness and produce decentered identities for surviving and resisting as a community. Also, multiplicity refers to understanding human migration concerning global processes. Dimitriadis and McCarthy (2001) defined multiplicity by considering large-scale development. The first avenue of multiplicity refers to the global enterprise of capital or neoliberal globalization that has accelerated the processes of global migration, technology, and cultural capital on a transnational scale. Social media's massive scale of imagination and representation is a second identified development. At this scalar level, multiplicity refers to the massive amplification of practices of self-production of images, mentalities, and possibilities driven by media cultures. Thirdly, multiplicity refers to critical interpretative frameworks around the post that have turned theoretical and methodological approaches around education. Accordingly, the authors identify at this level the popular language of endless possibilities of consumption that overwhelm daily lives affecting schooling and educational contexts.

In summary, in the global age, multiplicity arose as a new venue and habitat of undetermined crossroads influencing educational contexts. Therefore, we suggest that multiplicity recognizes another mode of understanding the experiential knowledge proposed in CCW that does not necessarily depend on stable notions of community. Rather, immigrant communities are involved in a dialogical production of meaning within a vast set of aspects in permanent transformation.

Concrete studies

According to Stuart Hall (1986), Gramsci laid out the terms for the methodological application of concrete studies as a way to socially analyze modern forms of power as constituting hegemonic, and therefore negotiated, congeries of relations rather than a zero-sum political game. This represented a forward advance in Marxist studies of power and everyday life. Concrete studies called attention to new historical conditions and relations informed by immigration and the new social movements that were expressing themselves in modern society in the form of new subjectivities articulated within the nation from transnational sources and connections. Through concrete studies, Hall sought to problematize race and ethnicity by calling attention to transnational realities. Hall works on the notion of historical conjuncture to explain concreteness, where universalist theories cannot fully explain the social interaction of actors, institutions, and popular culture formation transnationalism. This approach to analysis focuses on describing the cultural dynamics of social conflicts, taking into account regional and national differences. Actors in these conflicts form alliances based on their historical, economic, and political circumstances, with civil society and popular culture playing a significant role. The emphasis is on empirical data rather than abstract ideas. These social alliances are underlaid in the articulation principle of the development of authority over historical projects that individuals produce in particular contexts (Bobo, 2006). To explain this process, Hall (2001) maintains that attention must be paid to social articulations or moments in which the existing arena of social relations and the balance of power between contesting social groups reveal ‘critical breaks’ and ‘ruptures’ that might disclose new alliances and new formations. These new developments both augur and precipitate critical transformations in the present and future direction of society.

Therefore, considering that South-South migration is a relatively new phenomenon in South America and the lack of problematization of immigrant students as new social subjects with transnational experiences that are producing cultural transformation in the educational system, the concrete dimension helps us pay attention to at least two aspects of inquiry cultural diversity with immigrant students in the following ways. First, it is important to track the history of participants and dominant discourses about migration affecting the treatment of immigrants in the media, schools, and society. This double historical scene provides clusters of arguments to challenge mainstream notions of immigrant subjects and, potentially, context-based possibilities to build alternative abstractions about the inquiry. Secondly, concrete studies help bolster interest in and understanding of unequal scenarios via paying attention to contradictions and tensions in the research problem. Because historical concreteness works by overlapping different temporalities and directions, contradictions and tensions are crucial to get a sense of vis-à-vis associations where colonial mechanisms are reinvented within society by producing gradual penetrations of racism. The point here is that abstraction at the lower level of concrete operations and everyday cultural transactions and experiences provides rich information to unveil current identity formation, connected as it is, to local conjunctures and their nexus to global conditions.

A qualitative research design to integrate the CCW model and postcolonial framework

At this point, we wanted to be concrete about a qualitative research design to translate the CCW in South-South migration patterns. To accomplish this, we describe some characteristics of the research context that provided the lessons for this article. Then, we deployed the use of Critical Discourses Analysis and Testimonios as complementary methods.

The research context

We attempt to analyze the cultural wealth production (Yosso, 2005) of immigrant students and their families situated in contexts of permanent adaptability to navigate the inequalities they confront in northern Chile. The questions addressed are: 1) How do immigrant students and their families set up alliances, negotiations, and resistance to develop durable educational pathways? 2) What are the role of mainstream discourses in educational policies and stakeholders to reinvent immigrant’s governance? and 3) How are counter-narratives deployed by immigrant actors?

The research addresses a global lens to understand two cities: Antofagasta and Arica, which are enclaves of the global economy in permanent friction or exceptionalism against the ‘national space.’ Shaping as vertical forces that are interwoven throughout the economic, social, and cultural domains, this global nature of the economy ends up managing the local population and spaces (Ong, 2006). Still, those relationships are distinctive and need to be unmasked to fully explore and go beneath the surface of putative homogeneity associated with globalization. This requires, as Tsing (2005) argues, validating subaltern ways of knowing and the friction and collision of global with local conditions and subaltern ways of knowing. From a methodological perspective, the validation of this multiplicity or imprecise ways of knowing is a critical response to social sciences fixed to uniform and finalist categories about the space or lived experience (Sassen, 2002; Saukko, 2003; Wimmer & Glick Schiller, 2002). Particularly in El Norte Grande, these imprecise ways take place in the lived experiences of immigrant families, who coexist in liminal spaces for access to a house or job while they materialize their project of life associated with desires for better education, health, and safety.

In this South American version of Global Cities (Sassen, 2002), the research attempts to interweave lived experiences of immigrant students and their families, where multiple ways for building their life projects shed light on the circulation of transnational cultures in the educational system by intertwining social alliances via the circulation of forms, styles, and cultures (Appadurai, 2013) At the same time, the critical discourse analysis of educational policies related to cultural diversity aims to trace a prevalence of cultural and ideological discourses about Chilean normalcy (Infante & Matus, 2009; Matus, 2019), which limits the chances for honoring and validating the multiple expressions of immigrant students. Indeed, immigrant students are mediated by normatively prescribed categories about vulnerability, educational deficit, and structural discrimination related to culture, skin, or poverty. All said, In the following section, we introduce a complementary qualitative design that seeks to integrate the CCW and postcolonial theory frameworks via Critical Discourses Analysis (Fairclough, 2003) and Testimonios, a counter-storytelling technique (Solórzano & Bernal, 2001).

Critical discourse analysis (CDA): intertextuality and evaluative argumentation

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is a qualitative analytical approach aimed at describing, interpreting, and explaining the role that discourses play in validating and reproducing social inequalities (Mullet, 2018). By focusing on the (re)production of ideology in global contexts, CDA contributes to this research by unpacking neutrality and nominalization ideas (Fairclough, 2003) sustained by educational stakeholders and institutional information that rule public schools.

In implementing the CDA, we suggest deductive-inductive coding to identify the neutral facade or nominalization (Fairclough, 2003) of educational discourses related to public schools and their treatment of the cultural diversity the immigrant students represent. From the inductive-deductive coding, the next step aims to frame an intertextual analysis of master sentences to trace how educational policies contribute to the rationale of schooling practices that reinforce immigrants’ portrait as outsiders (Vavrus & Bartlett, 2009). For instance, in the study of cultural diversity in Chile, we analyzed educational policies that address diversity from the perspective lens: special education, socio-economic background, and interculturality.

In articulating the intertextual analysis into a global-local reading, we consider the categories of pertinency, relevancy, and policy context (Palacios Díaz, Hidalgo Kawada, Cornejo Chávez, & Suárez Monzón, 2019) by an evaluative argumentation. This analytical strategy involves movements of argument structures and denounce-announce actions to identify tension in the system and potential paths for a transformative agency. Thus, intertextuality helps to identify dominant discourses about cultural diversity in aspects of ideology and power.

To implement these qualitative analytical strategies, we draw on the methodological guide developed by Mullet (2018). This guide includes the settled features developed by the CDA network during the 1990s with an analytical strategy useful for its flexibility and simplicity (see Table 1). Mullet complements the agreed features of CDA by main references in the field with a strategy to apply CDA in a different field, which allow an easier transferability of CDA.

Table 1 Methodological strategy in CDA (Summary of Mullet, 2018).

| Characteristic in common (Mullet 2018, p. 120) | Stage of Analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| CDA scholars in the 1990s: Fairclough, Kress, Van Leuuwen, Van Dijk, and Wodak | - a problem-oriented focus | 1. select the discourse |

| - an emphasis on language | 2. locate and prepare data sources | |

| - the view | 3. explore the background of the texts | |

| - that power relations are discursive | 4. identify overarching themes | |

| - the belief that discourses are situated in contexts | 5. analyze external relations in the text (interdiscursivity) | |

| - the idea that expressions of language are never neutral | 6. analyze the internal relations in the texts | |

| - an analysis process that is systematic, interpretive, descriptive, and explanatory (Mullet 2018, p. 120) | 7. interpret the data | |

In applying CDA, the content analysis can interrogate assumptions about diversity in the educational system to establish a set of cluster-driven educational stakeholders' responses. The CDA analysis scope is an intermediary range between global or macro-political forces that influence states' efforts to manage diversity and the everyday responses of educational stakeholders in schools (i.e., teachers, principals, evaluators). The ideological information provided by CDA serves as a helpful complement to narrating the life project of immigrant subjects. By linking ideological assumptions in the research and providing context for sharing counter stories of immigrant students, CDA contributes to a more comprehensive understanding.

Counter storytelling: testimonios

Community Cultural Wealth (CCW) addresses the Critical Race Theory and Latinx studies which return to inquiry with the oral and lived experiences of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) to unveil ideological systems of domination. The art of cuentos, storytelling, and testimonios give voice to oral and lived experiences, and all of these methods fall under the branch of counterstories. Counterstories are defined as BIPOC narratives that critically reframe their reality outside mainstream narratives or stock histories. Delgado (1989) explains that giving voices to people in oppressed situations allows the identification of daily cultural artifacts and ideologies that reproduce racism and connect ‘the narrator’ with a community’s collective wisdom. This double dimension of counterstories is important because the ‘critique from below’ is complemented by a community-building function, where alternative possibilities are negotiated, and a new consciousness is enacted - a transformative one (Delgado, 1989; DeCuir & Dixson, 2004). In this article, we are proposing testimonies as the primary study approach. We understand testimonies as a qualitative method that brings personal and reflexive narratives, naturally oral. However, the difference with other story methods is that testimony is taken and written by a researcher (Saukko, 2003).

Methodologically, Reyes and Curry (2012) define testimonio as ‘a unique expression of the methodological use of spoken accounts of oppressions’, mainly retrieved by Chicanx scholars who adopted a recovering approach to managing narratives. This approach involves the process of translating oral accounts into qualitative analysis by taking the stories, reading the narratives, and creating analysis. As a qualitative technique of spoken accounts thus, testimonio considers the voices of oppressed communities, naming or renaming injustices from the bottom, and a process of awareness and empowerment that drives hope in the narrator and community. In this context, testimonios help contextualize the analysis of cultural diversity into an articulated analysis that involves narratives of immigrant subjects in permanent identity construction. From here, testimonies can retrieve oral accounts to frame narratives of ‘what’s going on’? with cultural diversity in everyday life. In framing testimonios, we collect semi-structured interviews in the Northern region of Chile from immigrants from Colombia, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Chile (transnational families). The collection of data addresses questions about personal identity, educational trajectory in past-present-and-future tense, migration experiences, and social anchors in the territory. Regarding participants, we work with two-generation (mothers and students) to explore nuances on the way to engage in educational projects.

The data analysis addresses Anfara's (2002) three iterative analytical steps: inductive-deductive coding, individual and across-themes analysis, and abductive coding. The analytical goal is to embed testimonies in a wider context provided by CDA analysis of educational policies about diversity, and the analysis of relationships associated with multiplicity and the acceleration of time and spaces that neoliberal globalization brings to the cultural diversity of immigrant subjects.

Conclusion

The postcolonial theory places relevant contributions to educational researchers and educators as well as the Community Cultural Wealth model engages an educational research agenda for honoring funds of knowledge of oppressed people. In the ongoing debate about fractures, expansions, and openings within post-critical educational methods, we attempt to contribute by developing theoretical elements that frame a complementary qualitative approach to address cultural aspects and identity formation of immigrant families in South-South migration patterns. In this conclusion, we want to mention three parts:

Firstly, in addressing the expansion of methodologies, social researchers cannot take away the fact that different disciplines produce different kinds of knowledge; still, to address the complex research problems, one needs to address different methodologies that help explain a social problem that theories cannot fully provide (McCall, 2005). The concrete studies framework thus contributes to engaging complex research problem because its origin took place in the debate about race and ethnicity in transnational realities.

Secondly, multiplicity invites educational researchers to embrace social phenomena from differences and ambiguities more than attempting to control social phenomena into fixed categories. This postcolonial multiplicity has committed to opening new strategies to understand the agency that we think complement the CCW's understanding of agency.

Thirdly, the complement of CDA and Counter-storytelling strategies provides important leads and openings for research on cultural diversity in educational contexts to recognize immigrant agency in uneven educational scenarios. Additionally, we point out that taking attention to experiential knowledge, the examination of cultural diversity can be translated to the elaboration of educational tactics to switch the dominant deficit thinking for discourses that embrace transnational realities in a positive sense. All said, we invite researchers and policymakers to give space to dig into the contextual analysis of cultural diversity to turn the dominant ideology of diversity in education contexts.