Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Acta Scientiarum. Education

versión impresa ISSN 2178-5198versión On-line ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.45 Maringá 2023 Epub 01-Dic-2023

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v45i1.63098

TEACHERS' FORMATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

Understandings on the use of pesticides by graduate students of a Rural Undergraduate Course of Nature Sciences

1Programa de Pós-graduação em Ensino de Ciências, Instituto de Física, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Av. Costa e Silva, s/n, 79070-900, Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil.

2Instituto de Física, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil.

3Faculdade de Ciências Exatas e da Terra, Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados, Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil.

4Instituto de Química, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil.

The present study shows an understanding of the perceptions of the pesticide theme by graduates of the Nature Science undergraduate course of the Intercultural Indigenous Faculty of a public university, without directly addressing environmental issues and the health of farmers and their families: intoxication, cancer, depression, among other diseases. The data were collected from course completion papers produced by graduate students from the Nature Sciences undergraduate course as a partial result of the doctoral thesis in the Postgraduate Course in Science Teaching of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS). To clarify the results, the methodology of Discursive Textual Analysis (DTA) was used, and it was possible to observe that the farmer’s low level of education interferes both in the perception of the risks and in the use of pesticides. Furthermore, they do not use Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs) and, consequently, apply pesticides on a large scale, without knowledge of the toxicity level, contributing to the monoculture practices within the agribusiness activities. This result contributed to rethinking the initial training of teachers of rural schools, supported by Paulo Freire’s theory, as a way to raise awareness and critical reflection on the risks of exposure to pesticides in order to promote sustainable agroecological practices and strengthen the debate on Education in/of the Rural areas.

Keywords: initial training of teachers; Freire; agroecology

O presente estudo apresenta a compreensão das percepções sobre o tema agrotóxico de egressos/as de um curso de Licenciatura do Campo de Ciências da Natureza integrado a Faculdade Intercultural Indígena de uma universidade pública, sem abordar diretamente as questões ambientais e de saúde dos agricultores e suas famílias: intoxicação, câncer, depressão, dentre outras doenças. O material empírico foi constituído a partir de Trabalhos de Conclusão de Curso (TCC) produzidos por estudantes egressos/as do referido curso, como resultado parcial da tese de doutoramento no curso de Pós-Graduação em Ensino de Ciências da Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS). Para a elucidação das compreensões, foi utilizada a metodologia de Análise Textual Discursiva (ATD), sendo possível observar que o baixo grau de escolaridade dos/as agricultores/as interfere tanto na percepção dos riscos quanto no uso dos agrotóxicos. Outrossim, eles/as não utilizam os Equipamentos de Proteção Individual (EPI’s) e, consequentemente, aplicam estes produtos em larga escala, sem conhecimento do grau de toxidez, contribuindo para as práticas de monocultura dentro das atividades do agronegócio. Esse resultado contribuiu para repensar a formação inicial de professores/as do Campo, apoiada na teoria de Paulo Freire, como forma de sensibilização e reflexão crítica quanto aos riscos à exposição de agrotóxicos, a fim de impulsionar práticas sustentáveis agroecológicas e fortalecer o debate da Educação no/do Campo.

Palavras-chave: formação inicial de professores/as; Freire; agroecologia

El presente estudio presenta la comprensión de las percepciones del tema plaguicidas por parte de egresados de la carrera de Ciencias de la Naturaleza de la Facultad Intercultural Indígena de una universidad pública, sin abordar directamente los problemas medioambientales y de la salud de los agricultores y sus familias: intoxicación, cáncer, depresión, entre otras enfermedades. Los datos se recogieron a partir de los trabajos de finalización de carrera elaborados por estudiantes licenciados en Ciencias de la Naturaleza, como resultado parcial de la tesis doctoral del Postgrado en Enseñanza de Ciencias de la Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS). Para dilucidar los resultados, se utilizó la metodología de Análisis del Discurso Textual (ATD), y se pudo observar que el bajo nivel de educación de los agricultores interfiere em la percepción de los riesgos relativos al uso de plaguicidas. Además, no utilizan equipos de protección individual (EPIs) y, en consecuencia, aplican plaguicidas a gran escala sin conocer el grado de toxicidad, lo que contribuye a las prácticas de monocultivo dentro de las actividades del agronegocio. Este resultado contribuyó a repensar la formación inicial de los profesores de las escuelas rurales, apoyándose en la teoría de Paulo Freire, como forma de sensibilizar y reflexionar críticamente sobre los riesgos de la exposición a plaguicidas, con el fin de fomentar prácticas agroecológicas sostenibles y fortalecer el debate sobre la Educación Rural.

Palabras clave: formación inicial de profesores/as; Freire; agroecología

A dialogical preamble to Education in/of the Rural areas

Popular education in Brazil gained strength from the II National Congress of Adult Education in the mid-1960s. During this period, the Congress served as a stimulus for new educational ideas and methods for youth and adults. Since then, Brazilian popular education has developed as a set of educational practices unveiled in the historical movement led by popular sectors as a movement for the liberation and emancipation of these populations. This popular education encompasses Education in/of the Rural areas, which involves social movements such as popular education movements, Catholic action movements (agrarian youth), rural social movements (peasant leagues, rural assistance service, among others), and other popular action movements (Carvalho, 2016).

Ruralist and urbanizing fronts predominated in pedagogical discourses from the 1930s until the 1970s, encompassing the counter-hegemonic system. Signs of transformation appeared in the mid-1990s as social and union movements articulated themselves, seeking from the government the guarantee of constructing public policies for Rural populations with pedagogical proposals that respected the reality, the forms of production, land management, ways of living and coexisting of these people who, until then, were forgotten (Carvalho, 2016).

The Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST) constituted an important milestone for Rural Education in the mid-1990s during Brazil's process of redemocratization. This movement held the I National Meeting of Educators of Agrarian Reform (I ENERA) in partnership with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the National Conference of Bishops of Brazil (CNBB), and the University of Brasília (UnB). This partnership resulted in the I National Conference for Basic Rural Education, held in Luziânia-GO in 1998. This Conference highlighted a more articulated debate among social and union movements regarding public policies for Education in/of the Rural areas (Carvalho, 2016).

Given the above, Caldart, Pereira, Alentejano, and Frigotto (2012) reflect on the importance of public policies that integrate peasants into the educational context, valuing the identity of these peoples:

By affirming the struggle for public policies that guarantee rural workers' right to education, especially to school, and to an education that is in and of the rural area, social movements question Brazilian society: why do peasants not need access to school in our social formation, and why does the proclaimed universalization of basic education not include rural workers? (Caldart et al., 2012, p. 259).

The concept of Rural Education implies the effective participation of social movements as part of the struggle for the rural public. The debate on agrarian issues and their assumptions are elements that guide this approach in which all these forms of knowledge are integral parts of the educational process. Their knowledge, skills, values, ways of producing, relating to the land, and sharing life are fundamentally important. On the other hand, the term Rural Education refers to a reflection of society based on the right to education, conceived from their place of life and its historical and cultural context, as well as their human and social needs, aiming for the struggle for education as a universal right, not as a compensatory policy8.

With this understanding of the written approaches, the Rural areas, according to the Operational Guidelines for Basic Education in Rural Schools (Resolution No. 1 CNE/CEB, 2002), brings its specific context for understanding educational spaces. The concept of Rural is presented as a territory, notably where the subject is immersed with their way of life and production. The organicity of these subjects in the Rural area involves symbolisms permeated by cultural diversity, multiplicity of knowledge about the land, with movements of struggle, social mobilization, and sustainability strategies.

Therefore, the concept of Rural area must be understood as part of the struggle of peasant populations. The territorial issue is very important as it brings the idea of sustainability and solidarity. It is through this territorial understanding that such a concept is constructed by the organicity of social movements, which constitute the essential and guiding element to build the pedagogical proposal of these people. The characterization and legitimacy of this Rural mass in social, economic, political, and cultural spheres are understood through the aspirations of groups and the local community.

In this sense, the Secretariat for Continued Education, Literacy, and Diversity (SECAD) of the Ministry of Education (MEC) was the body that forwarded Decision No. 1 (2006) to the Basic Education Chamber (CEB) of the National Education Council (CNE), published in the Official Gazette of the Union on 03/15/2006, addressing the pedagogy of alternation, securing its approval. It was through the experience of Rural Family Homes that seven components or invariants emerged, elucidating the characteristics of the pedagogy of alternation: the alternator, the educational project, the place of socio-professional interactions, the network of partners, the pedagogical device, the pedagogical context, trainers, and other educational actors (Gimonet, 1998)9.

Enhancing the functioning of alternation pedagogy, promoting balance among these invariants, is a challenge for the development of Education in/of the Rural area. This balance is always unstable since they are subjects in action within a system that is open and linked to life. And life is always change and evolution (Gimonet, 1998). Therefore, Rural Education stems from an understanding of what social movements are and how they can assist in the educational process of peasants.

In Brazil, a growing number of studies produced by educational institutions and farmer organizations point to the technical and economic feasibility of agroecology for food production, as well as for natural resource conservation (Mattiazzi, 2017). Agroecology is one of the activities that emerge primarily in the regions of São Paulo state, as exposure to pesticides has been causing potential health issues for the settled population, such as hearing loss, gastrointestinal problems (stomachaches), and cancer, affecting all age groups. Nevertheless, in the region of Mato Grosso do Sul, which encompasses the universe of this research, agribusiness activities still prevail.

Given this reality, contemplating and promoting agroecological practices can reduce the impacts caused by the excessive use of pesticides. Thus, this research aimed to investigate the understanding of peasant students' perceptions regarding the pesticide theme based on the debate on Rural Education in order to reflect on the initial training of Rural teachers in an emancipatory and critical manner in the Rural Education Undergraduate Course (LEDUC) in the Natural Sciences area. For this purpose, the following research question was formulated: How do the understandings of graduates from the LEDUC Course about the pesticide theme presented in their course completion papers10?

The exposure of these peasant workers to pesticides has been the subject of research, such as Pavanelli (2019), Castro (2017), and Mattiazzi (2017). The interest of most of these researchers is to promote the role of agroecology as an alternative source of agricultural practices and to disseminate a better quality of life for farmers, as most do not have a high level of education, making it difficult to understand the damage that these inputs can cause to human health.

Considering that pesticides are present in the work relations of peasant students, who perform agricultural activities on their plots, it's noteworthy that the emancipatory and critical training of these future educators at the university will be revealed by the possibilities and potentialities of the Freirean perspective to build the debate on Rural Education.

Pesticides are considered chemical and biological products that can be used in crops to combat certain pests (fungi, nematodes, bacteria, insects, weeds, rodents), applied according to the plantation (Castro, 2017). Therefore, as Rural Education focuses on an education tailored to those living in rural areas, it is necessary for this thematic approach to be introduced into the educational context of Nature Science studies of the LEDUC course for rural students.

In this sense, Paulo Freire's work entitled Pedagogy of the Oppressed brings important contributions to understanding how to unveil the reality of the oppressed and make them subjects in the process of constructing society, shaping a new educator for Rural schools. In Rural schools, there is the Pedagogical Political Project (PPP), which must be developed together with the school community (managers, coordinators, lunch staff, janitors, bus drivers) and the Rural community, in this case, the families of the students. Thus, the identity of the peasants is legitimized in the construction of this important document of the school, complying with Resolution No. 1, dated April 3, 2002 (CNE/CEB).

It's worth noting that the National Program for Rural Education (Pronacampo), held in March 2012, was defined as a policy for Rural Education in Decree No. 7,352 (2010), of November 4, 2010, arising from mobilizations of rural workers with aspects of 'rural education', driven by capitalism in the rural areas. Based on this, we highlight some intertwined challenges in Rural Education in Brazil.

On the other hand, the Program to Support Higher Education in Rural Education (Procampo) was created in 2007 by MEC, through the SECAD initiative, as a result of partnerships between public higher education institutions to promote the training of educators for rural schools in basic education.

PROCAMPO recognizes and advocates for the need for initial training for educators working in rural schools. This program, as a public policy, contributes to the debate surrounding educational issues that must be seriously and widely discussed by the Brazilian government. As observed in the country's history, educational policy, until then destined for rural areas, considered such spaces merely as extensions of the city, so that the school institution, curricula, histories, identities, and memories of educators were constantly disregarded (Santos & Silva, 2016, p. 140).

In this sense, the program was initially implemented at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), the Federal University of Sergipe (UFS), and the University of Brasília (UnB), with a PPP elaborated by representatives of the universities and social movements in each state, considering that the alternation pedagogy posed a challenge for teachers.

Given this reality, the articulated training between University Time (UT) and Community Time (CT) is the movement of alternation pedagogy and shows us possibilities for dialogue between temporalities and spatialities of different contexts, favoring the overcoming of one of the most significant challenges in the training of Rural teachers: the conditions of the formative process in dialogue with culture, leisure, religion, and work (Santos & Silva, 2016). Thus, the training of Rural teachers could instill specificities of the singularities that represent them.

The specific training of rural educators can mean guarantees of practices coherent with the values and principles of Rural Education, recognizing the social relations established there and many other aspects that point to the rural territory, not as an extension of the city, but as a valorization of ways of life, desires, and trajectories. On the other hand, such training should not be analyzed solely from the perspective of valuing community knowledge. It needs to be understood, especially, in the dimension of autonomy and in the organization of another society that confronts any form of oppression. In this sense, the demands present in rural schools require educators whose training enables them to understand the current rural reality. A rural area pressured by an exclusionary economic model and demanding intense resistance from its subjects, educators, and leaders of social movements. This is another objective of Procampo in defense of Rural Education (Santos & Silva, 2016, p. 141).

Reflecting on liberating praxis is necessary, as it is based on action-reflection, in the sense of being unfinished beings, in the process of overcoming one's own reality. Therefore, in the practice of dialogue, one sees the consolidation of praxis constituted from a dialectical unity (subjective versus objective). In this context, the process of humanization for Paulo Freire represents possibilities for beings considered unfinished and aware of their unfinishedness, stemming from a history, a real, concrete, and objective context. The unveiling of this reality is affirmed in the yearning for freedom, social justice, the struggle of the oppressed for the recovery of their stolen humanity (Freire, 2016).

The process of dehumanization referred to is not merely a stolen humanity but a violence on the part of the oppressors, the 'being less.' The struggle of the oppressed to overcome the 'being less' is a condition for restoring both oppressors and oppressed. According to Freire (2016, p. 41), “[...] here lies the great humanistic and historical task of the oppressed - to liberate themselves and the oppressors.” Furthermore, for Freire (2016, p. 53), “This overcoming demands the critical insertion of the oppressed into the oppressive reality, with which, objectifying it, they simultaneously act upon it.” The critical insertion reflected in the work 'Pedagogy of the Oppressed' refers to what might be possible from the dialectic of subjectivity and objectivity. The immersion of the oppressed in reality and the feeling of powerlessness in the face of the oppressive reality creates the boundary situation11. According to Paulo Freire (2016), the path to a humanizing pedagogy is a permanent dialogical relationship.

Considering these points from the work, it is deemed necessary to discuss that “banking education” is an instrument of the system's oppression. For Freire (2016, p. 80): “Instead of communicating, the educator makes deposits and communications that the students, mere receptors, patiently receive, memorize, and repeat. This is the banking concept of education.”

The role of the educator in this perspective is to position themselves to impel their students in the process of struggling for their liberation, guiding them towards humanization, in a movement of praxis, which implies the action and reflection of humans on the world to transform it (Freire, 2016). Dialogue is the cognitive act to unveil reality and promote problem-posing education. The difference is that banking education provides assistance while problem-posing education criticizes. Dialogue is an act of love. Thus, problem-posing education incorporates dialogue based on a horizontal relationship, founded on trust between subjects. In contrast, the banking concept of education is an antidialogical process (Freire, 2016).

With that said, the peasant, through their academic formation, can develop critical thinking as a possibility to reflect and problematize reality, seeking alternatives and conditions to unveil reality for transformation. This is possible with the support of social movements, the articulation with pedagogical practice applied in the classroom, the participation of student families (settlement community), and the empowerment of any public role the teacher may assume. Thus, the triad: school, student, family is brought up to speed on decisive issues in search of specific public policies for the peasantry. For Paulo Freire (2016), beings are capable of becoming subjects capable of generating liberating situations from reality.

Discursive Textual Analysis (DTA)

Partial analyses were carried out on 21 Course Completion Papers12, some presented as monographic articles13, out of a total of 28 productions defended by graduates of the LEDUC course integrated with an Indigenous Intercultural Faculty of a public university for the academic year 2014. The 7 productions not analyzed were not publicly available at the time of this research investigation.

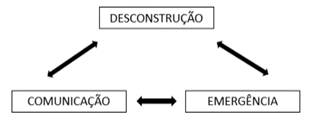

The organization of the analyses was based on four basic elements of Discursive Textual Analysis (DTA), with the first three constituting a cycle: 1) dismantling of texts; 2) establishing relationships; 3) capturing the emergent new; and 4) a self-organized process. Figure 1 presents DTA as a cycle.

In the first movement of the cycle, there is a deconstruction of the texts, in which the research information is analyzed. At this moment, the disordered fragmentation of information is self-organized with the conscious and unconscious involvement of the researcher, imbuing itself with intended new understandings. It is a disordered movement of information (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2016). Following this, Table 1 systematizes the title, the author (classified as Student A, B, C, etc., and numerically in ascending order), the year of publication, and the type of work.

Table 1 Course Completion Papers (TCCs) and articles from the 2014 LEDUC class, presented at the Indigenous Intercultural Faculty of UFGD.

| Title | Author and year | Type | Stage of the triad cycle: unitarization |

| The production of vegetables in the Eldorado II settlement, Fetagri group: obstacles and challenges | Student A1 (2018) | Article | |

| The difficulties of settlement residents in irregular lots in São Judas settlement | Student B2 (2018) | Article | |

| Environmental actions developed at Caburai municipal school in Santo Antônio settlement | Student C3 (2018) | Article | |

| The impact of soybean monoculture on food sovereignty: a study on changes in milk production in Itamarati-Fetagri settlement | Student D4 (2018) | Article | |

| The history of youth and adult education in Santa Rosa settlement | Student E5 (2019) | Article | |

| The peasant perspective on the impact of wildlife on the crops in Colônia Nova settlement, Nioaque, MS | Student F6 (2018) | TCC | |

| Farmers' perception of the capybara's influence on agriculture in Laguna Carapã, MS | Student G7 (2018) | TCC | |

| ‘Poison rules here!’: an analysis of the production method in Alambari-FAF settlement - a case study involving settled women | Student H8 (2018) | Article | |

| The presence of Senar in Eldorado 2 settlement, Sidrolândia/MS: a case study with farming families | Student I9 (2018) | TCC | |

| An analysis of students' perception at Padre André Capelli municipal agrotechnical school regarding school waste and recycling possibilities | Student J10 (2018) | Article | |

| Socio-environmental aspects and non-conventional food plants (PANCs) in Tamakavi settlement, Itaquiraí, MS | Student K11 (2018) | TCC | |

| The consumption of PANCs in Joaquim das Neves community, MST settlement Itamarati I | Student L12 (2018) | Article | |

| Initial teacher training in rural education: expectations and challenges of future Natural Sciences teachers | Student M13 (2018) | TCC | |

| Accessible pedagogical practices: alternative prototypes as a proposal for Physics teaching | Student N14 (2018) | TCC | |

| Rural experiences in city schools: why and for whom? | Student O15 (2018) | Article | |

| The importance and challenges of rural education and the closure of the Retirada da Laguna rural school | Student P16 (2018) | Article | |

| History and memory: encampment, land acquisition, education, school, and socioeconomic organization in Taquaral settlement in Corumbá, MS | Student Q17 (2019) | TCC | |

| Biodigester as didactic material in Natural Sciences teaching in Rural Education | Student R18 (2018) | TCC | |

| Bird species in Areias settlement, Nioaque, Mato Grosso do Sul | Student S19 (2018) | Article | |

| Use and conservation of permanent preservation areas and legal reserves in Boa Vista settlement, Ponta Porã, MS | Student T20 (2018) | TCC | |

| Disposal of inorganic and organic waste in Palmeira settlement, Nioaque, Mato Grosso do Sul | Student U21 (2018) | TCC |

Source: Adapted from Domingos, Pires and Oliveira (2020, p. 3-5).

Next, starting from the reading of the empirical material, the process began to extract units of meaning, which are not included in this article but totaled 544 units. It was possible to deepen the investigation of the research question by analyzing these units and seeking the central idea for each observed material, as if they were keywords (coding of units of meaning).

Coding is highly important for the analytical process. The following example can help clarify this process: the text of Student A (2018) was coded as A1; consequently, all fragments or units of meaning extracted from this text coded as U will have the sequence A1U1 (coding of the first unit of meaning). This means the first fragment taken from text A will be U1, and so forth: U2, U3. An explanation of this step is necessary to align our understanding of the procedure. Table 2 outlines the example of deconstructing units of meaning.

Table 2 Units of meaning that constitute the initial movement of analysis, unitization.

| Codifications of students' units of meanings A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U |

| Student A1: Peasant agriculture, agribusiness, cooperatives. |

| Student B2: agrarian issue, peasant agriculture, agribusiness. |

| Student C3: Sustainability and Rural Education, pedagogical political project, land, life, and work axis. |

| Student D4: monoculture, agribusiness, subsistence. |

| Student E5: History of Youth and Adult Education (YAE) in rural areas, literacy, plurality of subjects, diversity of context. |

| Student F6: The importance of wild animals in ethnozoology knowledge, cattle breeding activity by peasants, difficulty in obtaining inputs (diesel oil, fertilizers, pesticides, packaging) for agricultural practices. |

| Student G7: Curriculum and ethnozoology, traditional values of the community, awareness, and preservation of fauna and flora. |

| Student H8: Agroecological practices versus monoculture, women in rural areas, heads of households, healthy food without the use of pesticides. |

| Student I9: Family farming, technical assistance, income generation. |

| Student J10: Environmental education, selective waste collection, rural school. |

| Student K11: Food sovereignty, Non-Conventional Food Plants (PANCs), family farming. |

| Aluno L12: soberania alimentar, PANCs, agrotóxico. Student L12: Food sovereignty, PANCs, pesticides. |

| Student M13: Rural teacher training, Rural Education, rural school. |

| Student N14: Rural school, prototypes, Rural Education. |

| Student O15: Rural school, rural experiences, education system. |

| Student P16: Education in/of the Rural areas, rural school, closure of rural schools, initial training of rural educators. |

| Student Q17: Education in/of the Rural areas, rural school, closure of rural schools, initial training of rural educators, social movements, family farming, Lula governments, school transportation. |

| Student R18: Rural school, interdisciplinary, didactic sequence, chemistry, physics, and biology content. |

| Student S19: Interdisciplinarity, initial training, peasant identity. |

| Student T20: Pesticides, agroecology, agribusiness, commodities, peasant identity, characteristics of agrarian reform, monoculture, glyphosate, environmental education, social movements, Paulo Freire's conscientizing methodology. |

| Student U21: Chemistry, physics, and biology content, interdisciplinarity, problematization, Education in/of the Rural areas, pesticides. |

Source: Adapted from Domingos et al. (2020, p. 6-7).

The second stage of the cycle is the process of establishing relationships or categorization. At this stage, relationships are constructed between the base units, combining and classifying them, forming sets of meaningful elements, as completely as possible, but never finalized. This process of aggregation is the central part of DTA, as it highlights the construction of understandings regarding the investigated phenomena, characterizing this stage as a self-organizational process, stemming from the emergent understandings in the analytical process (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2016).

The capturing of the new emergent is the phase where the intuitions existing in the first moment, whether unconscious or conscious, undergo sudden insights of emergent understanding, which, according to Moraes and Galiazzi (2016), are 'rays of light' in the 'storm of ideas'. Categorization emerges from the search for understanding the unitization process, in which the hermeneutic circle is activated. This circle corresponds to the process of going back and forth in the codifications of unitization to find meanings and significance to understand the research objectives.

In this movement, the phenomenological attitude of the researcher is important as it brings the understanding closer to what the investigated subject expresses in writing. It is an action of grasping what the 'other' brings as theorization of the observed phenomenon. Additionally, categories are formed through continuous comparison between units of meaning and grouping; aggregation of codifications, of similar elements that give meaning to the investigated phenomenon.

Categorization can be constructed on different levels. In some cases, as in this research, it is classified into initial, intermediate, and final categories, with the aim of increasing the comprehensiveness of understanding and delimiting with greater precision and a smaller number of categories (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2016). Thinking about this systematization of categories, Table 3 was developed.

The third and final moment of the analysis movement was the construction of the metatext or the communication of emergent understandings, which can be descriptive or interpretative. Both movements contributed to this research during reflections and understandings, always returning, when necessary, to the units of meaning, providing theoretical depth to the interpretation, aspects inherent to the hermeneutic circle (Moraes & Galiazzi, 2016).

Thus, the triad of 'unitization,' 'categorization,' and 'metatext' constituted the path of the DTA analysis methodology. The metatext was configured according to the understandings of the set of categories developed in the analyses, which emerged in the final categories that signaled the construction of the metatext titled: The Agrarian Issue and Agrarian Capitalism in Mato Grosso do Sul.

Table 3 Initial, intermediate, and final categories.

| Initial categories: titles emerged after the identification of keywords | Intermediate categories addressed in the debate on Education in/of the Rural areas | Classification of terms of intermediate categories: agrarian issue/agrarian capitalism | Final categories in the debate on Education in/of the Rural areas |

| Understanding peasant agriculture: is it possible to create cooperatives to legitimize the production of vegetables for rural communities? (Student A1) Food sovereignty and its relationship with the agrarian issue in MS (Student B2) | Peasant agriculture, food sovereignty | Agrarian issue | Concepts of the agrarian issue in MS, agroecology: debate on Education in/of the Rural areas, peasant agriculture, food sovereignty, environmental education, using Paulo Freire's framework to guide research, women's work, invisibility. Social movements. Characteristics of the debate on Education in/of the Rural areas; characteristics of agrarian reform, initial teacher training. |

| The importance of official documents in Rural Education (Student C3) The role of environmental education in the understanding of selective waste collection in rural schools (Student J10) | Environmental education | Agrarian issue | Concepts of agrarian capitalism in MS, agribusiness: leases, land sales for survival, monoculture, pesticides. Modes of agricultural activities: agribusiness versus agroecology. |

| The plurality of rural subjects and the history of literacy in Youth and Adult Education (Student E5) Possibilities of ethnozoology in peasant activities in the region of Nioaque/MS (Student F6) Ethnozoology and curriculum: possibilities and traditional aspects of fauna and flora preservation in the region of Laguna Carapã/MS (Student G7) The training of rural educators for rural schools (Student M13) The use of prototypes in rural schools for Rural Education (Student N14) An insight into rural experiences legitimizing the rural school curriculum (Student O15) | Debate on Education in/of the Rural areas | Agrarian issue/Agrarian capitalism | |

| The plurality of rural subjects and the history of literacy in Youth and Adult Education (Student E5) The training of rural educators for Rural Schools (Student M13) The use of prototypes in rural schools for Rural Education (Student N14) An insight into rural experiences legitimizing the curriculum of rural schools (Student O15) | Paulo Freire's framework to guide the research | Agrarian issue | |

| Monoculture as the subsistence of agribusiness (Student D4) The strength of peasant women's labor: agroecological practices versus monoculture (Student H8) The importance of technical assistance for the development of family farming and income generation possibilities (Student I9) The training of rural educators for rural schools (Student M13) | Social movements | Agrarian issue | |

| The strength of peasant women's labor: agroecological practices versus monoculture (Student H8) The cultivation of PANCs by peasants: aspects of food sovereignty (Student K11) The poison is on the table: cultivating PANCs as a possibility for healthy food in food sovereignty (Student L12) | Female labor, invisibility; agroecological practices | Agrarian issue | |

| The importance of technical assistance for the development of family farming and income generation possibilities (Student I9) | Leasing, lot sales for survival | Agrarian capitalism | |

| Monoculture as the subsistence of agribusiness (Student D4) The cultivation of PANCs by peasants: aspects of food sovereignty (Student K11) The poison is on the table: cultivating PANCs as a possibility for healthy food in food sovereignty (Student L12) The strength of peasant women's labor: agroecological practices versus monoculture (Student H8) | Monoculture, pesticides | Agrarian capitalism | |

| Initial training of rural teachers and the debate on Education in/of the Rural areas (Students P16 and Q17) Interdisciplinarity and didactic sequence as possibilities in the initial training of rural teachers (Student R18) Official documents delimiting Education in/of the Rural areas (Student S19) The characteristics of agrarian reform today and the implications of pesticide use (Student T20) Disposal of organic and inorganic waste as possibilities in the initial training of rural teachers (Student U21) | Social movements, agrarian reform, agroecology, agribusiness (commodities), monoculture, pesticides, initial training, interdisciplinarity, environmental education | Characteristics of the debate on Education in/of the Rural areas; agribusiness versus agroecology; characteristics of agrarian reform, initial teacher training |

Source: Adapted from Domingos et al. (2020, p. 7-11).

The agrarian issue and agrarian capitalism in Mato Grosso do Sul

The process of categorization (initial, intermediate, and final) allowed for profound reflections on the understanding of perceptions of Nature Science teachers from LEDUC, resulting from the analysis process of the pesticides theme. The dichotomy of agrarian capitalism versus the agrarian issue arises as a result of the context in which the students are immersed, which is the region of Mato Grosso do Sul, specifically the municipalities of Sidrolândia, Laguna Carapã, Nioaque, Corumbá, Itaquiraí, Rio Brilhante, Dourados, and Nova Alvorada do Sul. Thus, the understandings of the characteristics of Education in/of the Rural areas are biased towards the agricultural practices developed by the students, instilling aspects of agroecology as a sustainable method and agribusiness as a large-scale production method, stemming from the use of pesticides, mainly glyphosate in soybean cultivation.

Highlighting a fluctuating reading of the elements that characterize Education in/of the Rural areas, such as peasant agriculture that can prevent rural exodus, Student A (2018) brings a passage, in the unit of meaning, that enhances agroecology as an alternative agricultural practice to the use of agrochemicals: "[...] how this activity can play an important role in the socioeconomic and cultural sphere in society producing healthy food with agroecological practices" (A1U2a). In another fragment of the text, the author points out the difficulties encountered by small producers regarding their agricultural activities in the municipality of Sidrolândia/MS (research region): "Some produce only for their own consumption (food sovereignty)14. Others still try to market the surplus from subsistence production. And others still engage in cattle breeding" (A1U4). "The commercialization of products from peasant agriculture faces difficulties regarding the flow of production. The lack of transportation leaves the goods in the hands of intermediaries, causing a differentiation in their selling value, resulting in losses for small producers" (A1U5). Student A (2018) also mentions a possible solution to the intermediaries' problem: "[...] the creation of cooperatives that can facilitate the sale and commercialization of goods at better prices" (A1U23).

As the economy in the state is mainly sustained by agriculture and livestock, the use of pesticides usually occurs in the agribusiness production mode, with monoculture cultivation in some settlements of agrarian reform. In the Dourados region, this thematic approach is contextualized by survival aspirations. Agrarian reform with the principles of family farming privileges settlers with local production free of pesticides. Thus, agroecology constitutes an important element in the role of training future Nature Science teachers. The text excerpt from Student B (2018) highlights that "[...] understanding agrarian reform in our country characterizes understanding the struggle and permanence of peasant people in the rural areas" (B2U2a).

Student D (2018) reports the influence of agribusiness on farmers:

Some have chosen agribusiness culture because they understand that by doing so, they could stay in the settlement without moving elsewhere in search of better living conditions. For a small part of the families, continuing with dairy farming, at least on a portion of the plot, is important to have another source of income and supplement the family's needs (D4U5a).

Regarding this passage, Paulo Freire (2016, p. 54) indicates 'limit situation' as the powerlessness of the 'oppressed' in the face of the 'oppressive reality', which seems insurmountable. This moment is marked when rural peoples sell or lease their plots to large landowners due to the lack of adequate conditions and public policies aimed at meeting their demands. The role of the rural educator is to drive the overcoming of this reality, fostering 'critical insertion' in the student. The oppressed recognize themselves as such and seek, through praxis (reflection and action) of humanity, to transform reality.

Paulo Freire also highlights the possibility of dialogicity within this movement. It is important here to emphasize the significance of future Nature Science teachers, especially those from LEDUC, assuming a position as unfinished beings and being aware of their incompleteness. The role of revealing reality by the popular masses is challenging and involves critical and transformative action in a real context in pursuit of greater humanization.

Social movements take a position within the agrarian reform in the country, as well as in the effective participation in shaping peasant leaderships, but face some limitations from the standpoint of a production mode based on monoculture (Domingos et al., 2020). Therefore, Student Q (2019) highlights the importance of social movements as constituents of the voices of peasants:

Social movements are very important for carrying out collective action, organization, and awareness of society's rights. During periods of difficulties, they have always supported and encouraged landless workers, acting as spokespersons between the camped people and the government (Q17U 19a).

Thus, monoculture poses a risk to peasant agriculture, as it caters to market demand, altering the production identity of rural people based on food sovereignty, and delegitimizes the role of Education in/of the Rural areas.

For Student E (2019), the importance of Adult and Youth Education emerges as an alternative to eradicate illiteracy, encouraging reflection on real-life situations:

[…] one of the major goals of the Brazilian State to reduce illiteracy is through proposals that provide the population, whose age no longer fits into elementary and high school education, but rather a complement to their educational background (E5U7a).

In another text fragment, Student E (2019) emphasizes:

It is important to note that education in rural areas did not always have the same rights as urban education, and to make this happen, several international conferences were held with the aim of taking measures regarding offering equal rights in education, both in urban and rural areas, aiming for improvements for those who did not have access to education at the right time (E5U8b).

According to Student E's (2019) fragment, it is possible to verify the low level of education in the context of various settlements, hindering the understanding of peasant farmers regarding the issue of pesticide use. Here, it is worth noting that the role of graduates is to drive the development of alternative agricultural activities for sustainability, even if they are embedded in the context of monoculture production with the use of agricultural pesticides. In this vein, we bring the text fragment from Student K (2018), highlighting the lack of knowledge among peasants (settled farmers) about Non-Conventional Food Plants (PANCs):

Another reason for the low local diversity in the use of PANCs is the settlers' lack of knowledge about the possibilities of using plants considered 'weeds' existing in the settlement and throughout the state of Mato Grosso do Sul (K11U16a).

Knowing the agricultural practice involving the use of PANCs, Student L (2018) points out this practice as a sustainable alternative:

Non-Conventional Food Plants are unconventional food resources that can and should be present in the diet, contributing to the sovereignty and food security of the population in general, especially because they are plants that do not require much care in cultivation, as happens with those that are frequently consumed and most of the time receive tons of pesticides to grow and prevent pests. PANCs enrich the diet and are healthier, mainly because they are free of agrochemicals (L12U9a).

Therefore, PANCs align with the proposal of family farming, which still prevails in the settlements of agrarian reform in Mato Grosso do Sul, where farmers play a more collaborative and sustainable productive role, despite the numerous challenges imposed by agribusiness, thus minimizing the exposure of plants to pesticides and environmental pollution in general.

The cultivation of PANCs constitutes a group of plants that could be acquired by food acquisition programs, such as the National School Meals Program (PNAE) and the Food Acquisition Program (PAA), implemented in Lula's government in 2003 and reinstated in the current Lula administration, providing students and the entire school community with a more diversified, nutrient-rich, and food-secure meal (Domingos et al., 2020).

In addition to sustainable agricultural practices, in Student H's (2018) text fragment, elements of the limit situation for students appear:

[...] as well as the high demand from residents who leased their lands for soybean and corn cultivation with extensive use of agricultural pesticides. In this region, it became evident that agroecological practices are still a novelty, and residents do not engage in them (H8U2a).

Student H (2018) also highlights the participation of female labor in the formation of the Alambari-FAF settlement, where peasant women were involved in agriculture development, either through agroecological techniques (trying to observe and understand how some residents acquired knowledge about it) or by using capitalist agricultural techniques, with extensive use of inputs and agricultural pesticides. According to the excerpt from Student H (2018), female work reaffirms sustainable practices: "Thus, ... agroecology involving women begins to gain prominence when they, peasant women, relate their tasks to agroecological practice" (H8U45).

Female labor is carried out in their backyard gardens, and they contribute to the weeding, especially during planting and harvesting seasons. Being protagonists in production, even without recognition, they assert their rights, occupying lands, planting, harvesting, seeking achievements, and independence in their own history (H8U47b).

Student H (2018) also considers it important to reaffirm that agrarian reform is legitimized by agroecological practices as the identity of rural people.

This research reveals the significance of understanding the land's value for those who live and produce on it, and how they perceive these recurring changes differently from those who did not experience the land conquest process. Therefore, it is necessary to create actions and public policies to reverse this situation and live a true agrarian reform and family farming, so that all settlers can benefit from local production free from pesticides (H8U60c).

According to this approach, it is worth mentioning that the Pesticide Law, Law No. 7,802 (1989), dated July 11th, 1989, and its regulation by Decree No. 98,816 (1990), dated January 11th, 1990, regulate pesticides at all stages and their production, commercialization, and use cycle (Alves Filho, 2002). With the approval of this Law, new and important aspects were regulated, configuring a new risk management structure regarding pesticides, especially concerning waste disposal that causes damage to the environment and public health.

According to Altieri (2012), the economy is increasingly globalized, imposing monoculture practices in contrast to agroecological practices, thus causing a crisis in the global food system, a direct result of the industrial model of agriculture, as it affects biodiversity with greenhouse gases against profits obtained on a large scale. The agrarian issue and agrarian reform are distinct but progress through historical time with some similarities: political subjects raise the agrarian issue as well as a proposal for agrarian reform (Constituent Assembly). Not obtaining political support, the agrarian structure continues as previously established, based strictly on property rights aimed at market buying and selling (Delgado, 2018).

In another text fragment, Student H (2018) points out the limitations experienced in agricultural production:

[...] the need of small producers for the consumer market, as they feel threatened, finding in agribusiness a way to expand their ideals, often ignoring that the agrarian reform project has caused damage to the production forms of settlers, who suffer from the lack of outlets for their horticultural products (H8U5).

Student H (2018) also reports that agricultural activities were developed by indigenous peoples considered traditional: "The first forms of working with the land occurred through indigenous cultures, which, in general, cleared the forest and burned (slash-and-burn) for land clearance and food planting" (H8U7d).

In this sense, Student H (2018) suggests that this knowledge of planting and cultivating the land, so widely used by traditional peoples, the indigenous, passed from generation to generation and was lost, which influenced other peoples. Currently, they engage in agroecological activities because they know how to work the land and make it productive, but they are not valued in small-scale production. Agroecology emphasizes precisely these ways of dealing with the land, seeking soil, forest, river, and field balance.

In the more recent historical context, there was a proposal for agrarian reform, overturned during the military government, and the recovery of the proposal (Constituent Assembly), also defeated in the 2000s, as it was relative to the agrarian issue of the 1960s. Therefore, the contemporary scenario carries marks of the land tenure system established in 1988 with the norms of the dominant policy and their respective associated problems. Hence, the agrarian structure inherits from the military regime the rural land property right since the Constitution of 1988 (Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil, 1988), as a criterion of social and environmental function, and adds the territorial rights of indigenous peoples and quilombola communities. The cycle of political economy is strengthened by agribusiness (commodification of territorial spaces) (Delgado, 2018).

In this perspective, distortions grow in Brazilian social policy with the 'disassembly' of labor relations through social rights such as public health, quality basic public education, social security, social assistance, and unemployment insurance. The agrarian issue aims to reflect on the problematization of the property structure, land possession/use, and their social subjects. However, agrarian reform constitutes a political and counter-hegemonic struggle that aims at the socio-economic conditions of the agrarian issue.

For Fernandes (2018), the term Paradigm of the Agrarian Issue (PQA) depicts scholars of agrarian reform, and the Paradigm of Agrarian Capitalism (PCA) refers to those who have no interest in agrarian reform, signaling differences between the conflicts generated by land disputes and development models.

Conflictuality is, besides conflicts over land, the confrontation that puts non-capitalist and capitalist social relations face to face, disputing lands, territories, public policies, development models, and governments. The central element of conflictuality is the dispute between agribusiness and peasantry (Fernandes, 2018, p. 63).

According to Fernandes (2018), this dispute is based on the continuous and accelerated tendency of agribusiness, wage labor, large companies, and multinationals producing in the model of monoculture for large-scale exports. This predominant agricultural sector development model in the current context, whose origin was the so-called 'conservative modernization of agriculture', pits the peasantry or family farmer who strives for development based on family (associative or cooperative) labor, called agroecology, in its own education projects, in institutional and popular markets, against conflicts and conflictualities that form the agrarian structure and rethink the agrarian issue from time to time (Fernandes, 2018).

In this context, Student I (2018) reflects on agricultural production: "Small and medium-sized Brazilian rural properties consist of a large part of the country's farmers; they are usually rural workers who produce various crops with little technology and family labor" (I9U1a). It is clear to Student I (2018) that the food from small producers, stemming from agrarian reform, feeds millions of Brazilians. However, it is the large landowners who have the power of investments in monoculture to meet the market on a large scale. The fact is that small and medium-sized producers suffer from low productivity, low prices, high costs, etc. This results in the sale or lease of their lots and properties, which are usually acquired by large landowners engaged in agribusiness.

It is worth noting that Student I (2018) reports that the settlers initially received resources and incentives from the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra) in partnership with technical assistance Crescer, which helped the families. However, with the change of the federal government, this support was discontinued. Currently, according to Student I (2018), the settlement faces a very sad reality as the lot owners sell or lease them to people coming from the city in search of better living conditions. A significant part of the settlement cultivates soybeans and corn; those who do not plant have leased their lots to agribusiness, considering that the settlers do not have income to survive from their lots. The remaining lots produce vegetables, taken for sale at the Central Supply of Mato Grosso do Sul (CEASA) in Campo Grande/MS. Some still have cows for milk; others have a few fruit trees.

In this sense, the National Rural Learning Service (SENAR) contributed little to the continuity of these families in agroecological productivity. The courses offered, according to Student I (2018), served for personal production rather than income generation, notably demonstrating the mismatch between public policies and technical assistance offered to settled families.

Therefore, since the low level of education was identified during the analysis as an element that interferes with farmers' perception of the risks caused by exposure to pesticides, the commitment of the Undergraduate Course in Rural Education in the field of Nature Sciences signals reinforcing agroecological practices as a means to minimize this impact on the environment and human health.

Final considerations

The LEDUC course works from a multidisciplinary perspective, and teachers in Human Sciences guide final course works to train students in Natural Sciences, providing different perspectives in pedagogical formation, as they come from distinct areas such as Chemistry, Physics, Agronomy, Biology, Geography, Pedagogy, Philosophy, and Sociology. This allows for an understanding of the initial formation's role in constructing scientific knowledge anchored in social, political, economic articulations, and the peasants' own historical life constructions.

Consequently, the formation of rural educators with a critical bias towards peasant aspirations was stimulated through this multidisciplinary articulation and in relation to research work that pointed out the pesticide issue with profound reflections. Thus, we highlight that the low level of education of the majority of agricultural producers is a reason why they do not use PPEs and, consequently, apply pesticides on a large scale without knowledge of toxicity levels. Furthermore, they contribute to monoculture practices within agribusiness activities.

Of the 21 analyzed works, nine presented reflections on pesticides without directly addressing environmental issues and the health of farmers and their families: intoxication, cancer, depression, among other diseases. This is considered a significant number, considering the different approaches of the Final Course Works.

Due to the mentioned facts and based on these perceptions and understandings of the pesticide theme presented by LEDUC graduates, there is a vision to enhance the initial training of rural teachers by encouraging the development of agroecological practices to provide a better quality of life for peasants, with healthy food. These practices could also allow them to participate in government food programs alongside rural schools. Finally, the continuity of research is necessary to ensure critical and emancipatory initial training for rural educators and thus contribute to understanding the risks caused to the health of rural workers due to the large-scale use of pesticides in agriculture.

REFERENCES

Altieri, M. (2012). Agroecologia: bases científicas para uma agricultura sustentável (3a ed. rev. ampl.). São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular; Rio de Janeiro, RJ: AS-PTA. [ Links ]

Alves Filho, J. P. (2002). Uso de agrotóxicos no Brasil: controle social e interesses corporativos. São Paulo, SP: Annablume; Fapesp. [ Links ]

Caldart, R. S., Pereira, I. B., Alentejano, P., & Frigotto, G. (Orgs.). (2012). Dicionário da educação do campo. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Escola Politécnica de Saúde Joaquim Venâncio; São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular . [ Links ]

Carvalho, R. A. (2016). Identidade e cultura dos povos do campo no Brasil: entre preconceitos e resistências, qual o papel da educação? Curitiba, PR: Appris. [ Links ]

Castro, R. G. (2017). Saúde do trabalhador: vulnerabilidade em hortas comunitárias frente ao uso de agrotóxicos em Palmas (Tocantins) (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal do Tocantins, Palmas. [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. (1988). Recuperado de http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicaocompilado.htm [ Links ]

Decreto nº 7.352, de 4 de novembro de 2010. (2010, 4 novembro). Dispõe sobre a política de educação do campo e o Programa Nacional de Educação na Reforma Agrária - PRONERA. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. Recuperado de http://portal.mec.gov.br/docman/marco-2012-pdf/10199-8-decreto-7352-de4-de-novembro-de-2010/file [ Links ]

Decreto nº 98.816, de 11 de janeiro de 1990. (1990, 11 janeiro). Regulamenta a Lei 7802, de 11/07/1989, que dispõe sobre a pesquisa, a experimentação, a produção, a embalagem e rotulagem, o transporte, o armazenamento, a comercialização, a propaganda comercial, a utilização, a importação, a exportação, o destino final dos resíduos e embalagens, o registro, a classificação, o controle, a inspeção e a fiscalização de agrotóxicos, seus componentes e afins, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. Recuperado de https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/antigos/d98816.htm [ Links ]

Delgado, G. C. (2018). A questão agrária hoje. In F. Coelho, & R. S. Camacho (Orgs.). O campo no Brasil contemporâneo: do governo FHC aos governos petistas (questão agrária e reforma agrária) (Vol. 1, p. 17-27). Curitiba, PR: CRV. [ Links ]

Domingos, D. C. A., Pires, D. X., & Oliveira, A. M. (2020). O debate da educação do/no campo no processo formativo dos professores de ciências da natureza. Anais do 1. Congresso Online Internacional de Sementes Crioulas e Agrobiodiversidade, 15(4). Dourados, MS: ABA. [ Links ]

Fernandes, B. M. (2018). Luta pela reforma agrária nos governos neoliberais e pós-neoliberais: a reforma agrária nos governos FHC, Lula e Dilma. In F. Coelho, & R. S. Camacho (Orgs.). O campo no Brasil contemporâneo: do governo FHC aos governos petistas (questão agrária e reforma agrária) (Vol. 1, p. 61-80). Curitiba, PR: CRV . [ Links ]

Freire, P. (2016). Pedagogia do oprimido (62a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Gimonet, J. C. (1998). L’alternance en formation. “Méthode pédagogique ou nouveau système éducatif?” L’experiénce des maisons familiales rurales. In J. N. Demol, & J. M. Pilon. Alternance, developpement personnel et local (p. 51-66, T. Burghgrave, Trad.). Paris, FR: L’Harmattan. [ Links ]

Lei nº 7.802, de 11 de julho de 1989. (1989, 11 julho). Dispõe sobre a pesquisa, a experimentação, a produção, a embalagem e rotulagem, o transporte, o armazenamento, a comercialização, a propaganda comercial, a utilização, a importação, a exportação, o destino final dos resíduos e embalagens, o registro, a classificação, o controle, a inspeção e a fiscalização de agrotóxicos, seus componentes e afins, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília . [ Links ]

Mattiazzi, A. L. (2017). Exposição a agrotóxicos e alterações auditivas em trabalhadores rurais (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul, Cerro Largo. [ Links ]

Moraes, R., & Galiazzi, M. C. (2016). Análise textual discursiva (Col. Educação em Ciências). Ijuí, RS: Unijuí. [ Links ]

Parecer nº 1, de 1 de fevereiro de 2006. (2006, 1 fevereiro). Recomenda a pedagogia da alternância em Escolas de Campo. CNE/CEB. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília . [ Links ]

Pavanelli, A. (2019). Vigilância em saúde de base territorial, integrada e participativa: uma experiência de formação em assentamentos rurais do pontal do Paranapanema (Dissertação de mestrado). Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Resolução nº 1, de 3 de abril de 2002. (2002, 3 abril). Diretrizes Operacionais para a Educação Básica nas Escolas de Campo. CNE/CEB. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília . [ Links ]

Santos, R. B., & Silva, M. A. (2016). Políticas públicas em educação do campo: Pronera, Procampo e Pronacampo. Revista Eletrônica de Educação, 10(2), 135-144. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14244/198271991549 [ Links ]

Streck, D. R., Redn, E., & Zitkoski, J. (Orgs.), (2010). Dicionário Paulo Freire (2a ed.). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

10The course completion papers were presented in the form of a course completion paper (TCC) and monographic articles.

11Limit situations are constituted by contradictions that involve individuals, producing an adherence to facts, instilling an idea of fatalism in what is happening to them. In the discussed text, the oppressed are not aware of their submission because the limit situation itself imposes powerlessness in the face of what is happening to them. Critical thinking can enable a process of problematizing reality and provide conditions for unveiling reality, aiming to transform it. According to Paulo Freire, individuals are capable of becoming subjects capable of generating liberating situations from reality. For further information, refer to: Streck, Redn, and Zitkoski (2010).

12Mandatory academic work serving as the final evaluation instrument for a higher education course, comprising an introduction, development, methodology, conclusion, and bibliographical references according to the norms of the Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT).

13Scientific communication research intended for publication in a journal within the field of interest.

14The concept of food sovereignty is respected due to the analyses carried out on the empirical material.

Received: March 30, 2022; Accepted: September 13, 2022

texto en

texto en