INTRODUCTION

“No one is born a good citizen […] a society that cuts itself off from its youth severs its lifeline”, stated former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan at the opening of the World Conference of Ministers Responsible for Youth on 1998 in Lisbon (UNITED NATIONS, 1998 Aug. 10). Consequently, the remedy against society’s disintegration seems to be education, and, in accordance with the historical context of the statement, education in public schools free of charge. The perception of schooling changed significantly at the end of the 18th century. A variety of actors such as state and education theorists, politicians and locally active people engaged in programmatic debates about the relationship between individuals and the state, citizenship and education. Montesquieu developed his theory about this relationship by claiming that “the laws of education have to be in relation to the principles of government”1 (MONTESQUIEU, 1949, p. 29). Throughout the 19th century, local schools slowly developed into territorially connected school systems and institutions of mass schooling that required space, specific and exclusive buildings for the purpose of schooling.

This article analyses the relationship between the state and its members as constructed through the school building. Historical evidence found in newspaper articles, professional journals, documents related to world exhibitions, and other programmatic material is used to detect discourses, policies and practices of how the school building was conceived to shape the (future) citizen in relation to specific historical-political contexts. The analysis is based on the cases Switzerland and Luxembourg departing from their correspondent historical moment when the need for specific and exclusive buildings for schooling was more intensively articulated: in Switzerland at the beginning of the 19th century, in Luxembourg in the 1880s. Both countries have relevant common and differing characteristics to discuss the school building’s role in building citizens. They are both multilingual states. Switzerland has four official languages distributed in cantons, political unities themselves; Luxembourg’s official three languages2 are distributed on different areas of public life, which makes its multilingualism a social multilingualism. This multilingualism represented a challenge for the establishment of a political unity, as it posed a severe challenge to the ideology of “one nation one language” (BLOMMAERT; VERSCHUEREN, 1991). Both countries presented strategies and discourses to produce unity by means of constructing the ideal citizen through school education, coinciding with the intensified debates and construction of school buildings. But they had - and still have - different political systems. Switzerland is a federal democracy and Luxembourg a monarchy. Both cases demonstrate the relation between nationally unifying, equalizing, and differentiating mechanisms, and the complex ways in which societal expectations were shaped.

As both Switzerland and Luxembourg were small states surrounded by powerful nation-states, they were concerned with issues of nationality and with constructing the nation-state. The first section of the article will expose the theoretical framework both of the concept of nation-state, and of school buildings as historical source from which we can formulate hypothesis about the role of school architecture in the nation building process. The second and third sections expose the case studies Switzerland and Luxembourg. Finally, the last section discusses the results of the comparisons identifying common or differing levels and spaces of discourse that construct nations via the school building as educator.

SCHOOL BUILDINGS AS SYMBOLIC RESOURCES OF NATION-STATE AND CITIZENSHIP

Since the onset of modernity and with it the development of a complex institutional and material schooling infrastructure, western societies share the expectation that children leave school as educated citizens (OSTERWALDER, 2011; TRÖHLER et al., 2011). This expectation is strongly linked to the idea of state, nation, and the nation-state as constructed during the 19th century: an equation of a territorially defined state, a collectiveness of sovereign people and a concept of nation consisting in voluntary or imagined communities through collectively and willingly taken decisions or through language, ethnicity or other common characteristics (ANDERSON, 2016; HOBSBAWM, 2012). Nations, though, are not static entities, their construction is a dynamic and historically contingent process, in which discursively involved actors draw on symbolic resources and apply different mechanisms to create boundaries between the people and the state resulting in definitions of nationhood (ZIMMER, 2003b).

Schools have been widely discussed as spaces where concepts such as nationhood could be transmitted. And the material place where schooling takes place, the school building, like other institutional or public architectures, was also central to the cultural self-understanding of nation-states, as a materialisation of their political power (e. g. ROTHMAN, 1971), and as part of a broader historicist repertoire to invent national traditions (HOBSBAWM; RANGER, 2015) manifested as much through the un-built as through the built (COLVIN, 1983). Thus, we analyse school in a broader cultural context comprising phenomena of nation-building and focusing school buildings as symbolic resources along political values and institutions, culture, history, and geography (ZIMMER, 2003b). School buildings meet these criteria: they represent the institution that is responsible for the transmission of a society’s knowledge and values, they are themselves culturally and historically embedded objects, and they are part of a country’s geographical distribution. We interpret school buildings as more than just merely cultural artefacts or containers of schooling, or a social milieu; instead, we look at them as a discourse that institutes notions of citizen(s) and school child(ren). School buildings also transport a concept of schooling: they are the first publicly seen idea of schooling and they are both materially and immaterially permanent, different than other curricular components of the grammar of schooling. Indeed, the school building is inseparable part of school memories: Thinking of children being transformed by school goes along with imagining the act of physically attending lessons in a school building or simply with the school building as the binding element between the adult and the remembrance of the former school child.3

The above discussed concepts of nation, nation-state, and school buildings nurture the hypothesis that school buildings, as materialisation of a public institution and as cultural expression, function as a symbolic resource and contribute to construct not only the idea of nationhood, but also of the future citizens of the nation-state. Through the specifics of its materiality, school buildings shape societal expectations about the kind of citizen to be produced by schooling, the skills and knowledge a student of a specific school has and how his or her future shall become. Yet, school buildings’ contribution to form nation-state citizens is not merely a process of power and control: Escolano Benito (2003, p. 53-64) described the school houses as synthesizers for all elements of educational culture, where the child is transformed into the school child, into the subject of school culture (p. 55), and, as we argue, the citizen. School buildings, as the neuralgic centres for the initiation into the rites of cultural sociability and civilisation norms, hence are considered as

the organisational means of a life world involving teachers and students as well as the norms that supported the educational sociability of the agents intervening in the instructional processes (Ibid., p. 55).

Through these buildings, children learn to make sense of the world (DAVID; WEINSTEIN, 1987). Hence, it is also here, how taxonomic categories like social class, race, gender, sexuality, expertise, or law come into relationship with one another (e. g. JERRAM, 2013).

The hypothesis of this study will be discussed on the basis of two case studies: Switzerland and Luxembourg as multilingual states and their specific agendas for constructing nation-state citizens. For multilingual nation-states school buildings are significant tools to enable the interaction between the nation-state and its citizens by drawing on different means of communication beyond spoken or written language. Research on the semiotic potential and mechanisms of buildings explains how they express meaning: Buildings can be understood as texts (“architextures”; cf. LEFEBVRE, 1974) that are independent from specific national languages (GOODMAN, 1985; PREZIOSI, 1979; WHYTE, 2006). They can refer to a nationally unifying set of forms, materials, symbols and means of representation that are open and understandable to all state inhabitants regardless of their language. Semiotic research has also demonstrated that a 'code' does not exist autonomously but as a system of relationships; hence the school buildings are culturally bound and thus, they mirror the multiple linguistic setting of nation-states. They speak differently to different addressees of the educational discourse.

THE SWISS EXAMPLE

Each canton legislates in its own way. […] As a result, the school organisation differs significantly from one canton to another despite the analogies and the shared background. Switzerland, a sort of melting pot of social experience, is a striking example, perhaps unique in the world, of such a small country enjoying such great political and administrative decentralisation, which is also reflected in the individualist character of architectural manifestations4 (BAUDIN, 1917, p. 10).

Architect Henry Baudin precisely characterised the Swiss nation-state in the above cited passage: The melting-pot of social experience refers to the Swiss linguistic, confessional and cultural diversity, and the traditional political autonomy of cantons with decentralized administration and highly empowered communes that challenged the construction of a unified nation-state during the 19th century.

At the turn from the 18th to the 19th century, Switzerland consisted in a loose bond of independent states - they had cooperation agreements but not a common constitution - that were forcedly unified to a centralistic, short-living Helvetic Republic (1798-1803) by Napoleon Bonaparte (GIUDICI; MUELLER, 2017). In the context of Enlightenment and Liberalism, the government of the Helvetic Republic intended to establish a school system that should guarantee the success of the republican state by means of educated citizens (BÜTIKOFER, 2006; OSTERWALDER, 2000, 2014). By the 1830s, Swiss cantons began to implement liberal constitutions that organized the cantonal polities and especially school laws ranging between federalist and centralist concepts (CROUSAZ et al., 2017). But it was not until 1848 that the modern federal Swiss state was founded as the loose bond of independent states gave itself the first federal constitution. Nevertheless, the cantons understand themselves until today as republics and sovereign states equally represented within the federal state.5 Within the education system, the federal constitution empowered the Federal Government to create institutes of higher education; the Swiss Polytechnic University (now ETH) was founded in 1855 and played an important role in the nation-building process (GUGERLI et al., 2010). On behalf of the federal constitutional reform in 1874, schooling was established compulsory, free of charge and run by the state guaranteeing freedom of religion (BUNDESVERFASSUNG…, 1874, Art. 28). These conditions already figured in most cantonal constitutions; nevertheless, their inclusion in the federal constitution was highly controversial because it seemed to threaten the autonomy of the cantons (CRIBLEZ; HUBER, 2008).

In 1882, Ernest Renan described Switzerland as a nation by will and consent, a state that consciously opts for a community of diverse citizenry (RENAN, 1990). It was this diversity that became constitutive of the national identity, the multilevel state polity, and the cantonal school laws. School issues in general and school-building regulations specifically remained until today within the competences of the cantons and the communes. Drawing on Zimmer’s study on the changing concepts of national identity in relationship to domestic and international contexts and historical junctures (ZIMMER, 2003a), we will analyse how the school building defines Swiss citizenship oscillating between the local, cantonal and national.

THE CANTONS AS SMALL NATIONS: CANTONAL SCHOOL BUILDING REGULATIONS AND NATIONAL DISCOURSES

Despite Baudin’s statement of the individualistic architecture which explicitly included the school buildings, historiography in the 20th century tended to affirm the opposite with regard to the 19th century schoolhouses asserting that they were all schematic, at best variations of one another (OBERHÄNSLI, 1996; SCHNEIDER, 2008). This undifferentiated interpretation is though nurtured by professionalisation of the architects and the heritage protection movement during the early 20th century (HELFENBERGER, 2013). The development of regulations concerning the school buildings and public discussions in Switzerland demonstrate through standardisation and diversity that school buildings were embedded in the context of nation-building as well in the cantons as in the later Swiss Confederation, and thus contributed to the construction of the cantonal and the national Swiss citizen.

From the need for knowledge to standardised expectations

By the 1830s, cantons with liberal governments such as Bern and Zurich discussed the release of official and binding regulations for the construction of school buildings accompanied by prototypes. The local authorities in the Canton of Zurich appealed to cantonal authorities explicitly demanding for official regulations claiming the building masters’ lack of knowledge (HOTTINGER, 1830). The cantonal authorities responded appealing themselves to architects and teachers as professional authorities (HELFENBERGER, 2013). Bern had indeed own prototypes or plans of specific school buildings acknowledged as role models in use, but Zurich was the first Swiss canton to officially regulate the construction of school buildings (ANLEITUNG…, 1835, MUSTERPLÄNE…, 1836). Although required by the Bernese school law from 1835, official regulations and prototypes were not released before 1881 (SCHNEEBERGER, 2005, p. 24). And most cantons did not follow until the 1870s and 1880s after the federal constitutional reform in 1874. Drafts of the constitution included subsidies from the federal government and a collection of prototypes to relieve the cantons’ expenses (SCHNEEBERGER, 2005). As part of the school system, rejection of a national school law and national school building prototypes emphasize the independent character of the cantons as “small nations” themselves.

Zurich had sent two copies of its regulation and prototypes to each cantonal authority immediately after issued. Thus, the authorities throughout Switzerland were at least informed about certain norms (HELFENBERGER, 2013). Indeed, those cantons that released or revised school building regulations between 1852 and 1900 drew in part on Zurich’s regulation from 1835 and its later revisions. In consequence, these documents reveal a certain degree of standardisation with respect to the expectations regarding construction quality, hygiene, pedagogic needs, and aesthetic outcome.

The Zurich prototypes from 1836 were designed in a classical style that has been interpreted as “representative” of the new established centralistic cantonal power in the sense of referring to other cantonal public buildings deliberately ignoring the private bourgeois and patrician houses of the time, which also adopted the neo-classical style. Since the teacher’s apartment was often included in the schoolhouse, it is more likely that the design also should represent the given local anchoring of the school, and the teacher’s role and increasing status since the last third of the 18th century (BRÜHWILER, 2014; HELFENBERGER, 2016). The teacher’s apartment in the schoolhouse was also subject to discussion because it was part of the teacher’s salary and it was expected to attract qualified personnel (BRÜHWILER, 2016; HELFENBERGER, 2013). Also, Bern’s school buildings varied throughout the 19th century according to the local conditions instead of relying only on Zurich or Bern’s neo-classical or mixed style prototypes (SCHNEEBERGER, 2005).

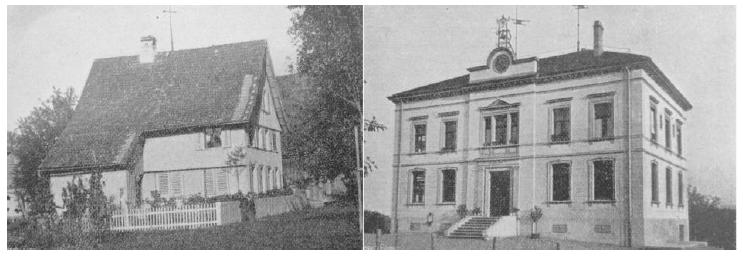

A quarter century later, when Zurich’s cantonal authorities inspected the commune’s schoolhouses and revised the regulation between 1859 and 1861, the local anchoring of the schoolhouse persisted, and the expectations and rating scales still differed importantly. Neither aesthetics nor administrative procedures were standardised. With the constitution of the Swiss Teachers Association and the publication of local and regional official reports in the association’s journal, the schoolhouse became an object of local profile and competition (HELFENBERGER, 2013). Indeed, none of the later cantonal regulations prescribed a specific style or binding general rules for external architecture, but rather claimed for well-balanced and unpretentious design (e. g. GROB, 1887, p. 162; VERORDNUNG…, 4.5.1891, § 32). Despite the explicit denial of luxury, a certain degree of standardisation took place towards the end of the 19th century depending on local interests and conditions. Claiming an unpretentious external design did not mean to abstain from noble façade decorations to distinguish the school buildings from factories and to beware the character of a public building. In the canton of Bern “worthy exterior” meant usually a classic or neo-renaissance style and placing the school building exposed to important streets instead of separated and free standing as recommended by hygiene experts. Thus, the school buildings in rural communes stood out from the environment6 (SCHNEEBERGER, 2005, p. 110-114). The new schoolhouse in Hohentannen, Canton of Thurgau, built in 1903, is an example of this tendency (Fig. 1). From the teacher’s perspective, the new building reflected the sacrifice of a rural commune in favour of progress and education remarking that the community equalled urban communes’ sacrifice, thus enhancing the importance given to education by rural citizens (HELFENBERGER, 2013).

Source: Schweizerische Lehrerzeitung, v. 48, p. 285, 1903.

Figure 1 Hohentannen before (1809) and after “standardisation” (1903). Old and new schoolhouse in Hohentannen (Canton of Thurgau).

The standardized expectations throughout Switzerland functioned as symbolic resources for defining national identity as they could be transformed into common values and knowledge with unifying effect in a time marked by the Franco-German War and the World Exhibitions.

Positioning school and school buildings between the local and the international: knowledge and local traditions as symbolic resources

The trend towards standardisation has to be understood within the context of world fairs, the Swiss national exhibition in 1883, school and hygiene exhibitions, which stimulated the self-representation of cantons and nations through education and school buildings. National and international expertise became more relevant than local suggestions (HELFENBERGER, 2018). On behalf of the international World Fair in Paris 1878, the Bundesrat (Swiss National Government) wished to exhibit the Swiss school system (ZUR PARISER…, 1877). The cantons were called to send their exhibits to Zurich. The organizers were concerned about exhibiting a Swiss school system that was not unitary, and thus, not national. This concern persisted 1883 when the Swiss national exhibition took place in Zurich. A commission consisting of cantonal representatives appointed in 1881 concluded that the exhibition should be national and therefore based not on cantonal but on factual and educational criteria and knowledge (WETTSTEIN, 1884, p. 25-26).

Although the Federal Government did not have competences regarding compulsory schooling - except for the subsidiary role in case the cantons did not provide sufficiently for it - the Federal Department of Home Affairs ordered a report on the existing permanent school exhibitions in 1887.7 The report suggested to organize these exhibitions by thematic profiles - the exhibits on school buildings were proposed to be in Bern - instead of structured by cantons to create a Swiss school exhibition: “Combined, all exhibitions offer the harmonious image of a large […], genuine, unified Swiss school exhibition” to be shown at world fairs8 (GUNZINGER, 1887, p. 139).

The general criteria “factual” and “pedagogic” applied also for school buildings. As factual criteria with regard of the school buildings may apply quality, hygienic and pedagogic standards which could be labelled as Swiss. Further, there is one element of the school buildings that helped the schoolhouse break through as a national Swiss feature: the heating and ventilation systems as products of the highest education institution in Switzerland, the ETH. Swiss engineers were internationally considered innovators of heating and ventilation systems applied in schoolhouses (HELFENBERGER, 2018). Thus, school buildings could represent the nation along the ETH, which was both product and motor of the modern Swiss state (GUGERLI et al., 2010). Parallel to the development of this “Swissness” in the international context, the cantons and even cities still emphasized their independence by highlighting their school buildings. On behalf of the national exhibition 1896 in Geneva for example, Zurich exposed a photographic poster of its most representative school buildings in Zurich City (Fig. 2). And local master masons published reviews on the newest communal or cantonal buildings (e. g. GEISER, 1901; NEUERE SCHULHAUSBAUTEN…, 1906).

Source: Zentralbibliothek Zürich, ca. 1896.

Figure 2 New school buildings from Zurich City: compiled for the National Exhibition in Geneva, 1896.

In addition, the local significance of the schoolhouse was increasingly discussed at the beginning of the 20th century, a period marked by high investment in building construction, demolition of traditional buildings substituted by modern art nouveau buildings and international demographic movement. This accelerated change and modernisation process was accompanied by its counterpart, the life reform movement, as answer to the perceived and dreaded loss of cultural identity. In this context, the Swiss Heritage Society was founded in 1905 to protect material and immaterial goods identified with national culture and identity (HELFENBERGER, 2013; PFISTER, 1997, p. 53-56). In the Society’s magazine, the schoolhouse was defined as a “silent co-educator”. As a public building, it was part of the public estate and thus it should materialise the community awareness, express the character of the people. Thus, architecture and schoolhouse design should follow local traditions instead of imitating foreign aesthetics - and foreign meant here not only extra-national, but also the import of urban architecture into rural communes. Otherwise the child would not identify with its commune, would not feel “at home” in the schoolhouse. The schoolhouse as silent co-educator also meant aesthetic education to enable people to distinguish between good and bad architecture, to decorate their future homes with local craftsmen industry, and to help them preserve a happy school remembrance (BLOESCH, 1916; HELFENBERGER, 2013; WERNLY, 1907).

While the Swiss pavilion at the international hygiene exhibition in Dresden presented Switzerland as Swiss nation, in Switzerland, nationality or nationhood were being linked more and more to the local commune constructing the national without mentioning the nation-state in a political sense. 1912, architect J. E. Fritschi published a review of school buildings constructed in Switzerland that year. As typical examples serve schoolhouses built in communes, not in cantons: St. Gallen City, Zollikerberg (Zurich), Bümpliz (Bern), and Neuhausen (Schaffhausen) (FRITSCHI, 1913, p. 554-555). Instead of using the term “national” or “Swiss”, he referred to Switzerland as the fatherland. The national unity was constructed by professional architecture standards combining hygiene and architecture quality with aesthetic adaptation to the local environment as new criteria besides splendour and impressiveness that honoured the communes (FRITSCHI, 1913, p. 551). In accordance with the idea of the schoolhouse as a home for the schoolchild, now mighty but frugal façades and interiors were reflecting “great love” and artistic skill resulting in “facilit[ies] on which the community may be proud” (FRITSCHI, 1913, p. 554).

ANCHORING CITIZENS THROUGH SCHOOL BUILDINGS

The schoolhouse was seen as an important indicator of citizenship because of the high expenditures that it conveyed for the public hand demonstrating the patriotic sacrifice of the people in favour of the local and the national development. Appealing and acknowledging the willingness for sacrifice in favour of education was a form of anchoring adult and child citizens. The school building as transmitter of educational content was not a novelty of the heritage protection movement. German doctor Georg Varrentrapp compared 1869 the schoolhouse with a textbook from which the child, the future adult and citizen, could learn. Recalling on Zurich’s school building regulation from 1861,9 he concluded that the schoolhouse had to be placed slightly elevated to make its importance visible to children and citizens (VARRENTRAPP, 1869). In the early 20th century, cantonal regulations for school buildings emphasized the schoolhouse’s role as educator in hygiene. The schoolhouse should be a model of cleanliness and order for the children (KREISSCHREIBEN…, 13.11.1911, s. p.). But schoolchildren should also take care of the schoolhouse by keeping it clean (REGULATIV…, 9.7.1907, Art. 66), and be accountable in case they damage buildings or furniture (RÈGLEMENT…, 15.2.1907, Art. 93).

Civic engagement for the local school could be rewarded, eventually integrating offices of local school authorities into the school building as it was the case in the City of St. Gallen in 1912, when the vocational school was intended to be a “home” not only for the future craftsman to promote local industry, but also for the school authorities and administrators (FRITSCHI, 1913, p. 551-554).

The heritage protection movement coincided with the increasing number of architects graduated from the ETH. These architects engaged against the monopole of cities’ and communes’ official architects and discursively transformed the schoolhouse from a functional into an artistic building, adding - not substituting - the idea of reaching the children’s soul to the idea of the hygienically educated citizen. The combination of local anchoring through the engagement of public hand and people, the professional interests of architects and doctors, and the democratic procedures of the Swiss political system transformed the silent co-educator into a “secret co-educator” that was assumed to directly influence the soul of the schoolchild (HELFENBERGER, 2013). Henry Baudin explained in 1917:

These simultaneous [educational] actions […] have a happy influence on […] the creation of equipped generations armed for the harsh material and moral struggle for life. It is therefore not foolhardy to say that […] in Switzerland, school architecture can be considered, if not as a primordial factor, but as a powerful and indispensable auxiliary to education and instruction, because, more and more, Swiss architects are dominated by the idea of making school "a house of gaiety and light where the soul of the child would open itself with a smile to the beauty of things10 (BAUDIN, 1917, p. 12).

THE MULTIFACETED SWISS CITIZEN

The school building in Switzerland supported the construction of a multifaceted Swiss citizen: it includes local, cantonal, national and international spaces of knowledge, and the involvement of laymen and professionals. The school building is a part of schooling that cannot be clearly assigned to one sole profession or one political authority. Thus, it represents at the same time an area of competition and the material synthesis of such relations. Local engagement and local aesthetics anchored the citizen to the commune. National exhibitions and cantonal competition anchored the citizen to the canton. The technological output of the ETH and its international competitiveness anchored the citizen to the nation state. All these factors, people’s sacrifice, aesthetics, technology, political authority in a multilevel system, and professional discourse unified by science rather than by the nation-state merged into the school building as a co-educator that was supposed to differentiate and standardise at the same time. Differentiation meant being a Swiss citizen in contrast to other nation states, a citizen of a specific canton, and within a canton a citizen of a specific commune. Standardisation meant the shared expectation not only with respect of the technological and aesthetic quality of the school building, but also that education at all levels of the system was a pillar of the Swiss state and a common trait of the Swiss citizen.

THE LUXEMBOURGISH EXAMPLE

Unification of the Luxembourgian Nation

Multilingual Luxembourg, a tiny Grand Duchy in the middle of Europe, situated between Germany and France, could not built its national vision on a monolingual citizenship. In the course of history, it had been considered part of Germany, France, Belgium and the Netherlands, giving rise to the idea of a societal bilingualism. Thus, Luxembourg was deeply concerned about national autonomy, size, and international competitiveness.

The combination of a German-speaking population majority and traditionally French-speaking (urban) elites promoted the idea of a specific “mixed culture” assuming that the best cultural influences of the neighbouring states came together in a unique mixture. This unique mixture is also omnipresent in architectural multilingualism. Research on Luxembourgian architecture in general has conceptualized this mixture as “knocking signs in the middle of Europe” (NOTTROT et al., 1999): Luxembourgian architecture has combined typically local and national features with international influences since the 18th century due to the arrival of Tyrolean builders (WAGNER, 2010). And still today, Luxembourgian scenery reveals very different contingent architectural traces of Italian, Spanish, Wallonish (de Beauffe), French (Vauban), Austrian, and Prussian architecture.

To understand the complex relations between the built school environment and visions of nation-state citizenship in this specific „mixed culture“, we will discuss the role of school buildings in the unification of the nation, the local schoolhouse as a medium to create local milieus and biotopes for different kinds of citizens, and how these local differentiations - unlike Switzerland - followed a discourse of social hierarchies and differentiation within the nation that distinguished „centre“ from „periphery“. Historical evidence will be drawn from two national construction booms in the 1870-80s and the 1950-60s.

A nation with a built centre: Luxembourg City as an urban educational model

Luxembourg’s schoolhouse history mirrors the long nation-building process. In the late 18th century, schooling in larger towns took place within other local authority spaces, as the case of the city of Wiltz illustrates: The same building hosted not only the local primary school but also the bailiff, the local police, and the hunter of the Duke (THEIN, 1991), thus forming an inseparable unit of state power, local noble privileges, and school. When Luxembourg was under French rule during the French Revolution, this unit fell largely apart: many schoolhouses were assigned to the commune and the spaces of local noble privilege were auctioned to local notables.

A Luxembourgian state had been planned 1815 at the Congress of Vienna, though it was governed by the Dutch monarchy in personal union. This province of Luxembourg commonly rented buildings for the winter months for the purpose of schooling: In 1817, Luxembourg counted 168 rented winter schools for 500 schoolmasters. Simultaneously, the government arranged architectural competitions for the erection of new schools, and appointed a commission consisting of state architecture commissioners, a geologist, and major local notables; yet, there was no education expert involved at all (THEIN, 1991, p. 113). But still after independence in 1839, many communes, especially in rural areas such as the Oesling, held school without a school building.

In the 1870s and 1880s, however, the reuse of buildings that had not originally been created for schooling was criticized as inappropriate and untimely. Michel Rodange, for instance, wrote in his famous animal story, Rénert, one of the most well-known literary projects of Luxembourgian nation-building, about the school in Waldbillig, a former shed:

The roof on it is transparent,

its straw is flying through the village,

it is fitting to a schoolhouse

like a funnel to a basket (RODANGE, 1872, p. 152).11

From then on, an exclusive building for school became a standard initiated in the centre and diffusing to the periphery. The idea of schools as “an establishment of pure and simple instruction” became dominant discourse (WINGERT, 1939, p. 142).

This period of school construction is directly linked to contexts of nation-building that went hand in hand with the formation of the nation’s built centre: In 1867, Luxembourg’s fortress, which had hosted a Prussian garrison and was considered unconquerable, was demolished in consequence of negotiations between France and Germany that lead to the declaration of Luxembourg’s neutrality. The demolition of the fortress fundamentally changed the capital city’s appearance. At the same time, Luxembourg changed from an emigration to an immigration country and experienced a distinct economic upturn. This development entailed a drastic policy change within the new state.

The city now expanded during the following decades beyond the former fortress boundaries and evolved architecturally and urbanistically: City boulevards and parks, plateaus and bridges were built, that connected the new quarters around the train station with the city centre. School building activities of this time include the schools in Pfaffenthal (1872), Bonnevoie (1872), Clausen (1876), Hollerich (1877 and 1885), and Grund (1878). The 1870s also brought a new prosperity to Luxembourg’s communes, especially of the centre: Schools were built for example in Muhlenbach (1884), Dommeldange (1889), Eich-Neudorf (1871-1877), and Pulvermühle (1880). The broad cultural and educational policy reform projects were likely endorsed by increasing institutionalisation, standardisation, and systematisation. They furthermore widened existing educational structures that had been perceived as local or strata-bound foremost urban-capital phenomena, to national projects. One of these reforms was the implementation of mandatory schooling in 1881 that expanded and organised the public-school system. Sources such as postcards with images of school buildings emphasised the aspirations of making primary schooling available for all citizens and demonstrated the transformation of the school building into a symbol of progress (or failure) of the modern public-school system (SCHREIBER, 2017).

Another important school expansion took place after World War II. Construction activity in general boomed in the 1950s with financial support from the USA to replace the schools destructed during war. Also new primary and middle schools were constructed all over the country, especially in the rural and structurally weak Luxembourgian North. The exterior appearance of schools followed a widely uniform construction and design regardless of school track and school type. This school building expansion was seen as a correlate of hope and progress for a new future: “a mental tower of cultural aspirations and national cooperation […] that shall promise a happy future in a renewed Luxembourg” (ANLUX…, MEN-1620, 1948).12

As a symbol of progress and hope, the school building took effect both locally, where it also promised a new dimension of social justice and chances especially for the children of industrial workers, and internationally, where it signalised that Luxembourg could keep track with international development:

Down in the valley, the father is working at the iron works, but from time to time he looks toward the Fonderie quarter, where his son is being prepared in the new school building for his future life (ANLUX…, MEN-1622, 1948).13

Equal chances and national coherence were core points of the school construction programme and its correspondent discourses: Hierarchical differences that had existed so far, such as the ascetic character of schools in the rural North, were retrospectively attributed to climatic circumstances like rough winds, instead of societal hierarchies (SIMON, 1990). The schools should now foremost respond to the “criteria of functionality and rationality” (ANLUX…, MEN-1620, s. d., app. 1960) by assuming that a luxury and representation free architectural environment was more likely to correspond to the school’s pedagogical and educative assignment.

A remarkable public attention in the 1960s - over 30 newspaper articles in two years - stressed the equalizing and unifying notion of new primary schools and school centres that were moreover celebrated with grand public opening ceremonies embedded in religious and local rituals (LUXEMBURGER WORT, Oct. 6, 1969, p. 5; July 16, 1970, p. 6) The new entities of the unified school system symbolized the community project: they received Catholic consecrations, people sung the national anthem, the construction charter was immured, and the traditional hammerscale was celebrated. Among the local guests were not only representatives of the commune, clergymen and politicians, but also prominent army and police members (e. g. LUXEMBURGER WORT, Oct. 6, 1969).

Over the decades, the school buildings became national institutional buildings that served for national unification in manifold ways, some of which will be outlined hereafter.

The school building as public building and moral architecture

A former city school student reported, how the view from the classroom to the cathedral, the citizen administration building, and the post office with its imposing clock impressed the school children (SCHWAB, 1969). Indeed, school buildings formed a public complex as moral architecture together with other institutions of the nation-state (ROTHMAN, 1971). The location of the school building mirrored the institution’s role within the commune and the state: “the school, like the church, is a dominant of the village, the city, the scene (paysage) and the country (pays)”14 (FRIEDEN, 1955, p. 265).

In most Luxembourgish communes in the 19th and beginning 20th centuries, school buildings were built near churches and were connected to them by a narrow path. The construction boom in the 1950s and 1960s brought forth new complex architectural relationships with school buildings, such as spatial interactions with saving banks, post offices, and community houses. Community services like the commune secretariat and assembly spaces for the local councils shared space with school (SCHREIBER, 2017).

Rothman has outlined how the construction of state buildings was associated with the “triumph of good over evil, of order over chaos” (ROTHMAN, 1971, p. 85) referring to the French Revolution as negative counterexample: Paris had built in hundred years more beautiful streets than Luxembourg, and yet, France’s own people had burnt them to ashes because they lacked good education and morality. Thus, school’s public embedding went hand in hand with the definition of national values to morally educate the young to become loyal state citizens (LUXEMBURGER WORT, Feb. 10, 1873). Deficiencies of school buildings were brought in correlation with a moral deficit. For instance, schools were criticized for having too many classrooms aligned along too narrow corridors:

[It is] impossible to maintain order and discipline […] before or after school and during breaks, even to observe shame and morality; […] especially the boys become habits of exuberance and impertinence, of brutality and meanness (Ibid.).15

These moral features attributed to school buildings show how persistent the 19th century notion of the nation-state as a moral nation was in the 20th century. In the 1950s, less obvious but not less intense, it was expected that the school building should teach the child to shape the milieu by him - or herself, making it better, more beautiful and more valuable. For this purpose, the school building should further - apart from developing children’s intelligence - the moral character of the schoolchild, e.g. the desire for activity, practical and aesthetic sense (GREISCH, 1955).

The moral character of the school system was supported especially in rural areas by a new type of school building, the so-called school centre (LUXEMBURGER WORT, Mar. 21, 1968). They functioned as a wholesome biotope of the local community and steered behaviour where there was a general mistrust in the population: They integrated canteens, classes vertes, (“green classes”, possibilities for outdoor learning activities, e.g. via school gardens or eco-preparations; cf. KLEIN, 2005) social measures such as a milk breakfast for all students or sports facilities (LUXEMBURGER WORT, Sept. 15, 1970, p. 10) and promoted the ideal of schooling as an all-embracive school experience with creative spaces for the local community encounters across ages and beyond class boundaries.

DIFFERENT LIVING SPACES: SCHOOLS AS MILIEUS

The commune as the small nation

School buildings also worked as tools for anchoring citizens. The school building’s location served the communities to distinguish good and bad areas. Until the late 19th century, schools were at any case placed in non-commercial spaces, in civic zones with other public buildings or in domestic, residential zones intending to attract young families to the suburbs. A sense for the local community should be fostered by also encouraging parents to tightly hold the population together (FISCHBACH et al., 1955).

Such societal planning went hand in hand with the school system’s bureaucracy. The school buildings were for instance integrated into the official statistics, which provided the inspectors with concrete criteria to make classrooms comparable and evaluate schools. Reporting on school buildings was not prescribed to school inspectors; nevertheless, most of them criticised the school building situation in their reports, thus demonstrating that the schoolhouse provided ways of comparing communes regarding furnishings, size, orientation, location, sanitary installations, light, insonoration, the kitchen, even wall colour and very detailed instructions for the building’s measurement. Many schools did not meet requirements such as the clarification of the budget previous to construction (ANLUX…, MEN-1620, 1947-1960). To advance a school building project, documents of communal or national development were required: population statistics, estimated future school attendance, the commune’s demographic profiles and the school inspector’s expertise (ANLUX…, MEN-1620, 1964). Yet, despite these prescriptions, many school construction plans were approved without the documents. These measures were more likely to establish objective procedures involving official expertise than decision-making, supposedly aiming at overcoming intranational tensions between different occupational groups and stakeholders. The reports about school buildings also reveal that their construction was not at all purely rational, but indeed acknowledged other public dimensions of the school system, yet in a more implicit and less representational way. In order to make the children feel at home in the local community, both the built and the unbuilt, the criteria of functionality and rationality could for instance recede into the background: The school “has to be modest and simple, but homely” (ERPELDING, 1955, p. 339). Although the instructions clearly reject economic and prestige-bound differences between public schools, they allow for local adaptation to “cultural needs” (ANLUX…, MEN-1620, 1948). This reveals another aspect, the school building as the local community core.

The school building as core of the local community

The goal of the school construction policies was to strengthen the schools’ integration into the local community and to advance especially small rural schools of the “underdeveloped” Luxembourgian North (SCHUMACHER, 1955, p. 309). New primary and middle schools were built between 1945 and 1964 to favour a nationwide consistent school distribution. Apart from Luxembourg City with 50 new schools, the cantons of Wiltz (41) and Esch (41) had the most school constructions, followed by Clervaux (40), and also the most expensive new schools were built in the canton of Wiltz (ANLUX…, MEN-1620, 1945-1964).

The authorities and the public discourse in the 1950s and 1960s envisioned rather uniform school buildings throughout the nation, i.e. functional, rational and adapted to the villagescape. The architects were instructed to integrate schools into the existent environment making the learning process itself local through the school building: (ibid.) the most impressive examples are object lessons that often departed from the school building and proceeded to knowledge of the local commune, the canton and the nation. For local studies, too, the schoolhouse was used as a concrete object of instruction. Taking advantage of the usage of local products and topics for construction and decoration of the buildings, various doors, windows and other elements were used as motives for drawings (ERPELDING, 1955, p. 344).

However, the school buildings themselves included manifold aspects of local differentiation. Communal competition was fostered on levels other than the concrete shape, as is the case in the sums spent for schools, the order in which they were granted, and in popular petitions reacting to inequalities in this field (ANLUX…, MEN-1622, 1970; MEN-1623, 1960).

One example: Local press reports about primary schooling increased promptly in small communes like Kleinbettingen, Bondorf, Rumelange or Hobscheid. Not only chronicles and articles in local journals, but also in national newspapers depict a distinct narration of success stories of the small local primary schools (STEFFEN-KIRPACH, 1969).

In these periodicals, landscapes, regional and communal spaces, were depicted as milieus, as living spaces for different kinds of citizens. In public discourse, school politics became a venue for communal political competition. The local organisation of schooling in communes, their occupancy rate, number of children per class and other local issues were questions addressed more than any other topic by local councils and by the local population via public reports in newspapers directly comparing communities (LUXEMBURGER WORT, July 16, 1970, p. 13; July 16, 1968). National coherence was emphasized on a formal level. But on school level, subtle differences between schools became pluralized. The local community gave schools occasion to develop their own particularities such as participation opportunities for parents and municipality members, and classes for migrants and disabled children. (LUXEMBURGER WORT, July 11, 1969, p. 7) Criticism against total and centralized institutions was conveyed to schooling situations leading to re-empowered local councils, which were assigned responsibilities they had lost in the beginning of the 20th century. Especially rural communes claimed also for better regional accessibility (LUXEMBURGER WORT, Sept. 7, 1968; Oct. 12, 1968).

DIFFERENTIATED CITIZENS OF THE NATION-STATE

The analysis shows how schools served the construction of unified and equal citizenship. However, school buildings themselves held manifold opportunities for differentiation. Despite the propagation of a homogenous and “organic” school system, the school buildings served as a medium to distinguish the centre from the periphery. Ancient societal differences previous to Luxembourgian national unification lingered and were nationally legitimized, co-defined by the proximity to the nation’s centre. Two examples illustrate this.

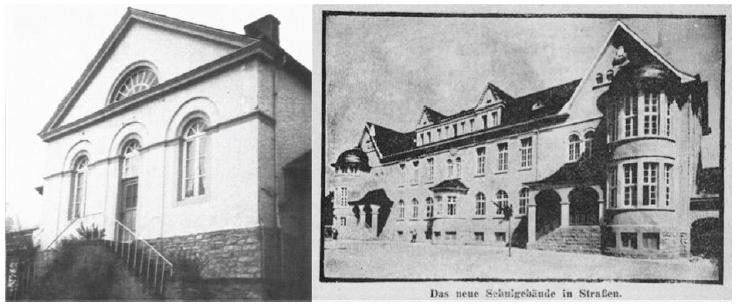

The first example concerns the processes, how uniform model school types spread from the capital to the country in the later 19th century, as a symbol of progress for the new nation-state. These model school types furthered a differentiation within the nation. The first standard model of school buildings had a clearly recognizable neo-classicist shape: it was an urban architectural model, a low building with colonnade-like elements, doors and windows with semi-circular, stilted and segmental arcs, festoons around the buildings, one uniform national model that spread the urban model of schooling (SIMON, 1990; SCHREIBER, 2017). This model with architectural reference to Greek temple fronts had become the standard school building and had occasioned a fever of imitation at the countryside (SIMON, 1990). By the 1880s, this standard model for school building shaped the image of the village significantly. This construction style is typical for Luxembourgian schools, churches, and major government and military buildings (Ibid.) (Fig. 3).

Source: Tageblatt, july 31, 1933.

Figure 3 Left: A standard school building from the 1880s (Hoesdorf). Right: A “modern” school building from the 1930s (Strassen).

However, at the time this model had gained national popularity, a new model school type was already spreading from the towns of the centre, around Luxembourg City. Here, the usage of rectangular or low-arc windows was established around 1885. In the following decades until the Second World War this new building type also spread over the country in communes with a semirural, semi-industrial population. The doors and windows with semi-circular arcs that were so popular in the countryside, were now retrospectively criticized as “austere style of Florentine renaissance very much favoured in the German-speaking areas“ (WINGERT, 1939) while rectangular windows seemed to express “a more refined French taste and a more profound understanding of the practical pedagogical needs, but also in a sort of oppositional spirit against the administrative milieus that had made the school building of German genre the model school” (Ibid., p. 145). This type of school allowed towns aspiring to become cantonal centres to profile themselves as such. Redange for instance could position itself around 1900 as regional capital with the institutionalisation of artisan and vocational education (SIMON, 1990). The same holds true for Mersch where neo-gothic elements decorated schools. Mersch also aspired profiling itself as a town of (French-inspired) artisans and thus was one of the first communes to establish an upper primary school. The communes’ engagement in profile shaping was visible in the foremost eclectic use of historical architectural styles. It is not coincidence that the new school in Redange integrated elements that resemble the architecture of the wealthier French bourgeoisie.

The second example was the binary use of school centres and pavilion schools in mid 20th century. The concept of large school centres was only scheduled for the rural North as an active tool of societal planning to promote new village-centres (central villages; cf. GREISCH, 1955) and to anchor people to a new core of rural landscape. However, this model was not intended for implementation in the capital or Esch: Small pavilion schools were on the contrary built in cities and towns, or rather in their suburbs and residential zones, which also served to anchor citizens. One could talk of a suburbanisation of the city school. Some of the first pavilions were built in Belair, Pulvermühle, Hollerich, Limpertsberg, Grund, Clausen, or Dommeldange (PHILIPPART, 2014) - and it is remarkable how this list resembles the list of communes around Luxembourg City in the 1870s school expansion. Apparently, this is a list of nation-centre showcase projects; more pavilions followed in the industrial suburbs and outskirts of Luxembourg’s second biggest city Esch (ANLUX…, MEN-1620, 1945-1967), sufficiently distant to the infrastructure of the city (ANLUX…, MEN-1620, 1963).

Not only did these pavilion or garden schools schedule more space per child - up to 30 square meters - (SCHUMACHER, 1955, p. 309) pavilions were also placed in a more open way into calm and “natural” areas of the cities. Supposedly, pavilion schools were easier to expand. It also shows that societal planning initially did not calculate any population growth for the “periphery”.

BUILT NATIONS: PLURALISTIC UNITY AND “ORGANIC” DIFFERENTIATION

To look at school buildings as co-constructors of citizenship helped to understand the manifold and complex dimensions of school buildings as educators. Indeed, it showed that school buildings convey important expectations about the system of thought within a nation with its respective national imaginaries of unity or differentiation. School buildings represented both in Switzerland and Luxembourg symbols of success of the modern nation-state situating the nation culturally, morally and politically. Also, in both countries the school buildings comprised unifying and differentiating functions within a broad public sphere, in communicative and discursive fields, and in citizen logistics.

For the case of Luxembourg, school construction activities increased at times when the construction of a harmonious and stable nation-state society was at stake both in the 1880s and in the 1950s. In Switzerland school building activities do not necessarily coincide exclusively with the construction of the nation-state if this is understood as the establishment of the modern Helvetic Federation in 1848 and the following construction of the “nation by will” (Willensnation). But, since the Swiss citizen is in addition a citizen of a commune, evidenced in identity card and passport, it can be affirmed that school building activities coincide also with the establishment of a stable local and regional society.

School buildings functioned in Luxembourg and Switzerland as unifiers establishing or reinforcing (respectively) the commune as the core of the nation by defining norms and values through the cultural self-definition of the state. They also provided in both cases for communicative lines between local, national and international levels conveying expectations about the school system. But the concept of the commune and its place in the nation is fundamentally different in both states. In Luxembourg, aspects of social differentiation and distinction are part of the school constructions despite the symbolic representation as one homogenous national system. This concerns primarily the production of elite consciousness, and differentiation between local communities. A clear distinction between the centre and the periphery is recognizable, which equals communal competition also with a perspective of different chances of the future citizens within the nation. For instance, national models of "good" schoolhouse construction spread from the capital city towards the rural regions. The symbolic message sent by school buildings and school system was in Luxembourg that of an (allegedly) organic entity. In Switzerland, cultural, linguistic and local differentiation was precisely a main trait of national citizenship discourses until will and engagement for education became visible in standardised school buildings. But then again, schoolhouses’ local anchoring against schematic architectonic standardisation became a shared expectation which persists until today and equally represents not only diversity, but also claims for equal education for all.

By promoting core aesthetic values, school buildings were expected to promote common moral and civic values attached to local mores and national ideals at the same time. Luxembourg did this by creating different milieus that allegedly fit to the necessary different life-worlds of children, Switzerland by linking the local and the national through the different but complementary levels of the school system. Another unifying function of the school building consisted in its role in citizenship and societal policies aimed at anchoring the citizen by means of urban development projects. In Luxembourg this happened through the inclusion of elements of the state bureaucracy (such as inspections) in the school building (again revealing a system of thought of the nation as constructed top-down from the centre towards the periphery), while in Switzerland such bureaucratic elements were second-rate compared to the identification with education as a distinctive trait and anchoring tool.

The analysis could at least show the complicated and tense relations that surrounded the development of school construction between order, control and openness, between function and aesthetics, international influences and nation-building, and how school buildings provided educational and moral legitimation of societal expectations about schooling and the future citizens. Factors that mattered were for instance the location, distance, visibility, environment, duration, shape, size, reminiscence, similarity and difference, but also discourses and rituals. This article has foremost shown the overall importance of the local commune buildings in multilingual nation-states. To see, whether these are also factors important in monolingual nations, it might be useful for further research to pay more attention to a cartography of schools over time, their location within the community, as well as to what it reveals about power relations and schooling in nation-states.

text in

text in