Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1519-5902versión On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.18 Campinas 2018 Epub 01-Jun-2018

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v18.2018.e034

DOSIER

Male and female teachers of Primary public schools in Cotia (SP, 1870-1885): teachers’ trajectories and strategies of teaching as craft

1Professora de História do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil

2Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil

Abstract: This article introduces fourteen public primary teachers who had taught from 1870 to 1885 in Cotia, a countryside municipality in the surroundings of São Paulo. The aim was to examine their teaching practice as well their engagement in other sectors of society. It focuses on a male and a female teachers who were responsible for the first masculine and feminine schools for over than 25 years. They formed a couple in their private life and taught in the same schoolhouse. The main sources were reports from teachers, government and inspectors, newspapers, enrollment books, demographic data, baptismal and marriage certificates, and letters. The article is divided into three sections. In the first one, we present Cotia and its culture conceived as caipira. Next, we explore the trajectory of the teaching couple. Finally, we highlight some information about the ten other male teachers and two female ones.

Keywords: history of education; primary teachers; Empire of Brazil; public school.

Resumo: Este artigo apresenta 14 docentes públicos que lecionaram entre os anos de 1870 e 1885 em Cotia, município caipira do entorno de São Paulo. Detalha suas áreas de atuação na docência e em outros setores da sociedade, com destaque a um professor e uma professora que ficaram responsáveis pelas Primeiras Cadeiras de primeiras letras por mais de 25 anos, formaram um casal na vida privada e lecionaram na mesma casa. As principais fontes utilizadas foram relatórios de professores, de governo e de inspetores, jornais, livros de matrícula, dados demográficos, certidões de batismo e casamento e ofícios diversos. Está dividido em três partes. Na primeira discorre sobre Cotia e a cultura caipira. A seguir, debruça-se sobre o casal docente. Por fim, apresenta os demais dez professores e duas professoras que, no período estudado, assumiram cadeiras no município.

Palavras-chave: história da educação; professor de primeiras letras; Brasil Império; escola pública

Resumen: Este artículo presenta catorce docentes públicos que enseñaron entre los años 1870 y 1885 en Cotia, municipio “caipira” (rural) del entorno de São Paulo-Brasil. Examina sus áreas de actuación en la docencia y en otros sectores de la sociedad, con destaque a un maestro y una maestra responsables por las primeras Escuelas de primeras letras por más de 25 años, formaron una pareja en la vida privada y enseñaron en la misma casa. Las principales fuentes utilizadas fueron informes de maestros, de gobierno y de inspectores, periódicos, libros de matrícula, datos demográficos, certificados de bautismo y matrimonio y diversos oficios. Está dividido en tres partes. En la primera discurre sobre Cotia y la cultura “caipira” (rural). A continuación, se centra en la pareja docente. Por último, presenta a los demás, diez maestros y dos maestras, que en el período estudiado asumieron Escuelas en el municipio.

Palabras clave: Historia de la Educación; profesor de primeras letras; Brasil Imperio; escuela pública

Introduction

This article intends to contribute to the understanding of the singularities of the history of education when approaching the performance of male and female teachers of primary public schools in Cotia, a country town in the surroundings of São Paulo, in the late nineteenth century. The main sources used were periodicals (especially publications in newspapers, such as orders of provincial government sectors, anonymous notes and chronicles), government reports, Public Instruction reports (from inspectors and teachers), enrollment books, demographic data, baptism and marriage certificates, and various offices. As a methodology, we follow the threads of the name, as proposed by Ginzburg and Poni (1991). The dossier allowed the tracing of 14 teachers in Cotia in the last decades of the nineteenth century and allowed to identify the other public positions and functions that they occupied concurrently or not with the teaching practice and to verify that the male teachers transited in areas such as public safety, justice and the arts.

The analysis highlights the trajectories of João José Coelho and Maria Joanna do Sacramento. Respectively male teacher and female teacher of the First two public chairs created in the Village, who remained in the teaching profession for more than 25 years, formed a couple in private life and taught in the same house from 1873 to1885. To understand the relationship between private life and teaching practice, we used the category teacher-homes of Munhoz and Vidal (2014). About the other teachers, we make brief considerations. The information is more sparse in function of the spatial (Village of Cotia) and temporal clipping of the research (1870-1885), which privileged the teaching experience of the couple. Before presenting these characters, however, we discussed the country town of Cotia, in order to compose the scenario in which they lived and, at the same time, to explain what we understand by caipira ‘culture.

Village of Cotia and the ‘caipira’ culture of São Paulo

The municipality of Cotia22 in the nineteenth century was characterized by rurality, with a predominance of small farmers and agricultural production focused on subsistence, the domestic market and, to a lesser extent, supplying the capital. In the words of Antonio Candido (2001a), it was like a particular rustic culture that denominated of caipira. According to the author, rustic culture (and society) expresses the “[…] universe of the traditional cultures of the man of the field; which resulted from the adjustment of the Portuguese colonizer to the New World […]”, which implies “[…] a constant incorporation and reinterpretation of traces, which are changing along the rural-urban continuum” (p. 26); and ‘caipira culture (and society)’ includes this characteristic of rustic culture, restricting itself to the particular universe of São Paulo23 (Candido, 2001a, p. 28)2.

Geographer Pasquale Petrone (1995) called caipira belt the area around the capital of São Paulo, formed especially since the second half of the nineteenth century. It is constituted by villages initiated in the colonial time, being the caipiras formed, to a large extent, by mestizos with indigenous ancestry (p. 374). According to the author, a “[…] belt of poor land around the agglomerate […]” of the capital was developed with “[…] a dominant subsistence agriculture, characterized by the small farm system” (p. 371). For Petrone,

For a century, caipiras marked the cultural landscape of the outskirts of São Paulo, their contacts with the metropolis being made at the expense of a modest commercial activity: using isolated freighters, small troops, or ox carts, they took their merchandise to the city and contributed to create a picturesque chapter that then characterized some metropolitan angles [...] (Petrone, 1995, p.375, emphasis added).

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Cotia began economic decline, due to the end of tropeirismo24 and the rise of coffee cultivation. Neither the construction of two stations of the Sorocabana railroad came to reflect positively in the local economy as it happened in other cities of São Paulo. In Cotia, the stations were constructed far from the Village, headquarters of the administration.

Wissenbach (1998), in analyzing criminal cases in an attempt to rebuild the lives of enslaved and freedman people in the first Comarca of São Paulo (of which Cotia was a part) in the second half of the nineteenth century, observed that in rural areas around the capital poverty was the “[…] major issue to be faced” (p.103), by both masters and slaves. In these areas, the masters did not have many slaves. Together they worked in the field, without any other individual moderating this relationship (as the overseer), as it happened in other richer regions.

A chronicle published by Salambô in the Correio Paulistano newspaper of 1872 is representative of the caipira everyday life and brings two characters from local schooling. Titled a newspaper reader, Salambô sent long chronicles to the newspaper editor of the newspaper Diário de São Paulo in 1872, published in the section Publicações Perdidas and titled Sobre o que vai pela Paulicéa. In them, with ironic and reporting content, the author talked about diverse subjects. The newspaper chronicle, for Antonio Candido (1992, p.14), is organized

Through the subjects, of the loose composition, of nature of unnecessary thing that it usually takes, it adjusts to the sensitivity of the whole day. Mainly because it elaborates a language that speaks closely to our more natural way of being. In its unpretentiousness, it humanizes;

[...]

By taking shelter in this transient vehicle [the newspaper], its intention is not that of writers who think of ‘staying’, that is, remaining in the memory and admiration of posterity; and its perspective is not that of those who write from the top of the mountain, but from the simple ground floor25.

From the ‘ground floor’, Salambô invited the ‘friend’ editor to a ‘jaboticabas walk’. According to him, “[…] the São Paulo person passes without eating, without drinking, without sleeping, but does not pass without the jaboticabas”, fruit preferred by the caipira, according to Candido (2001a, p. 72). Referring to the visit to Cotia in the company of a friend - Salambô looking for the jabuticabas and the friend by virtue of an inheritance -, the chronicler portrays two public teachers from Cotia.

A public teacher (the 1st) taught classes in cotton shirt sleeves, slippers without socks, hat of reeds, eyeglasses, a double-sided cigarette, which looked like an ear of corn, and a knife to the belt.

About the second teacher Manoel Mulher told me things from the oldies goldies.

He says that the said teacher has disturbed him in such a way that he no longer knows which is the right hand. The account lesson starts from 6 in 6 to 36, nine less 0, and that is what the explanation is summed up, which is summed up to 0. The teacher, is still ManoelMulher who informs, does not admit the metric system to be difficult, prefers the cubits and bushels, which, he assures, are more convenient to the ‘merchant’: falla ex cathedra, as says the neighbor Fulgencio.

To put order to school, the man proposed to the government the adoption of mucunan, to correct the boys.

It must have been interesting the man armed with mucunan! S. Lourenço by the side of the grill, instrument of his torture.

So well does the boy Joaquim Rodrigues, who opened a school and has nine disciples, he is more prudent and less clever than the teacher of ‘lust’, who when he ‘comes across’ an erotic question soon ‘deepens’ it.

But let us leave the business of Cotia and let us talk about jaboticabas [...] (Salambô, 1872, p. 2, emphasis added).

Although the chronicle was published in 1872, the narrative seems to refer to an earlier time. Quite possibly, Salambô met the first public teacher of Cotia, Antônio Barreto. Of the second, João José Coelho, only had news by former student Manoel Mulher. The informality of dress in the exercise of teaching suggests the first teacher in caipira clothes. Besides the clothes, a characteristic gesture of the caipira culture composes the scene: the long cigarette. Another element of current use (São Paulo, 1874, 1886)26, part of the caipira dress, drew the attention of the chronicler: the carrying of a knife to the waist during the lessons.

About the second teacher, the satire moves to the content of the classes. Instead of teaching the metric system, he preferred ‘cubits and bushels’, a knowledge ‘more convenient for the merchant’. With many lands, besiegers and planters, the teacher might attribute to practical life the content to be taught in school. A similar case was pointed out in the narrative of the trajectory of a teacher from Paranaguá, Hildebrando, built by Munhoz (2012). The author demonstrated that the teacher adapted the knowledge taught to the local context and concluded that this contributed to the frequency of the students. Paranaguá, a port city, was the scene of several commercial transactions and the necessary accounting skills.

To ‘correct’ the students, the second teacher used ‘mucunan’, “[…] legume herb that produces hairy pods that cause allergy and irritation” (Borba, 2004, p. 945). Another subject mentioned in the letter was Joaquim Rodrigues, a ‘boy’‘more prudent’ than the public teacher (accused of speaking immoralities). He became a private teacher, opened a school and had nine students. Considering that most of the documents used in this article are institutional, the Chronicle of Salambô helps to construct another point of view on the teaching profession in the second half of the nineteenth century.

In the following two items, we discussed public male 11 teachers and three female teachers, in order to establish a relationship between their actions, local society and the schooling process. The trajectories were constructed, following the threads of the name (Ginzburg & Poni, 1991), in periodicals from São Paulo27. Eliminating false cognates, we were able to identify public positions, participations in party directories, among others, exercised in concomitance or not to teaching.

Initially, we presented João José Coelho and Maria Joanna do Sacramento. The other male and female teachers and their experiences, privileging the period in which they taught in Cotia, make up another subitem. Unlike the couple, about these ten male teachers and two female teachers, there is little information or because of the little time they were in the municipality or that the course in the teaching profession has exceeded the period delimited for the research. Their presence, however, makes it possible to understand the schooling scenario in the municipality and to locate the trajectory of the teaching couple in the correlation between the peers, as well as to highlight some of the characteristics of the teaching profession in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Teachers of the First Chairs in public life and couple in private life: Maria Joanna do Sacramento and João José Coelho

Maria Joanna and João José were teachers of First Chairs in the Village of Cotia since joining the teaching profession. She began to teach in the feminine school in 1858 and he, in the masculine one in 1860. They retired in the same year, 1885. They had “[...] honest conduct and regularity of life with those who are known, publicly and privately […]”, according to district inspector Manoel Joaquim da Luz, in a report of 1869(Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP], lata CO5044). They married in November of 1873 (Brasil casamentos…, 1873) and from there they began to teach in the same house. In the nineteenth century,

The house, which for the most part was also the school, was the scene of many conflicting relations between the teachers themselves, their respective families and the government, presenting a tangle of relationships in which the public and the private confused, often tense and heterogeneously (Borges, 2014, p.68).

In Cotia, the spaces used as schools were mostly the home of teachers and, sometimes, of other citizens or chapels. The residence of the couple of teachers was the scenario of two schools, at the same time, from 9 to 14 hours. The female classes took place in the living room of the house and the male ones in the living room outside; which was possibly related to the social dynamics in which women should remain in the private space.

What were the effects of the couple’s classes in the locality and their work on the development of schooling in Cotia? Without disregarding the desire to be together, married, could the results of this proximity of relationship be discussed as a tactic in acting in the teaching profession? To discuss these issues, we will first address the trajectory of Maria Joanna, then the couple’s teaching practice and, finally, the trajectory of João José and its unfoldings.

Maria Joanna do Sacramento has taught for 27 years in the First Feminine School of the Village of Cotia. She was nominated on June 1st, 1858 and was sworn in before the City Council on the 30th of that month (APESP, ref. CO1007, 30/06/1858). In May 1869, she was approved in an examination to receive 200 thousand réis per year, in addition to the salary, an advantage established by the educational legislation to the approved teachers (Correio Paulistano, 1869). Unfortunately, no information was found about her life outside school, except for the name of her parents, that she married João José Coelho in 1873 and had no children.

According to the marriage registration (Brasil casamentos…, 1873), Maria Joanna do Sacramento was born in Cotia, daughter of Manoel José da Rocha and Anna Joaquina do Rosario. About her father, nothing else was located, a sign that he did not hold positions or had greater visibility in the period. The teachers’ wedding was witnessed by Antonio Barreto, a former teacher and friend of the groom, and in that year, district inspector, and José Joaquim Pedroso Junior, road inspector and mayor. The ceremony took place in a private oratory, indicating the desire for privacy for the sacrament, since in the pages of the marriage book there is only mention of marriages occurring in the Mother Church.

The public life of Maria Joanna was linked only to the position of teacher of the feminine chair of Cotia, at least that documented in the sources. The fact can be credited to the patriarchal society in which she lived. She may have been very active with the families of her students, but this activity, if existed, left no trace. According to Maria Lúcia Hilsdorf (2003), “[…] the female teacher, principal or school owner is a recurring figure of Brazilian society between the 1850s and 1900s”. Hilsdorf (1999, 2003) analyzed the presence/absence of women in the school environment in the nineteenth century in São Paulo from data contained in “[…] 312 titles of newspapers, almanacs, yearbooks, magazines and other cultural and variety publications of the time” (1999, p.8), as “[…] the woman-teacher, the woman-owner of schools, and the student” (Hilsdorf, 1999, p.10).

In any case, women are there, in action, educating and being educated long before the Public Normal School opened their doors to them in 1876: in the case of public female teachers, being approved for the teaching profession in palace examinations or with the City Councils, or sometimes simply named after interference from political sponsors; and in the case of private female teachers, requesting registration in the Province, as prescribed by law, or teaching in the house itself, without interference from the authorities. (HILSDORF, 2003).

Maria Joanna was among the female teachers pointed by Hilsdorf (1999, 2003) as an example of a woman who spent a long period in teaching, along with 12 other female teachers (Hilsdorf, 2003). According to the author’s sources, Maria Joanna do Sacramento remained in office in Cotia from 1858 to 1873. We have, however, obtained documents attesting to her exercise for an even longer time, until 1885. Until 1884, Cotia had only one female public school and some private ones.

From 1873, Maria Joanna and João José gave classes at the couple’s house. Maria Joanna’s class has always had frequent students, never fewer than the number required by the government (20), which suggests both she mobilized some tactics to keep open the school and an acceptance of the community. In the first case, it must be considered that schools with a lower than minimum enrollment were suppressed. Therefore, the maintenance of the chair required the registration, although not always reliable, of at least 20 students. In the second, it can signal that those responsible for the students did not bother with the coexistence with boys. According to Gouvêa (2003), the presence of girls in school sometimes confronted traditional values and found parents’ resistance in allowing their daughters to attend another residence, where there were also boys and men, as well as boys and husbands of the teachers.

According to article 92 of the Provincial Instruction Regulations of 1869, girls in boys’ schools and boys in girls’ schools would not be admitted. In the case of the teachers’ chairs of Cotia, although the house was the same, the rooms were different, which appears as another tactic used by the couple to circumvent the legal norms. It is worth mentioning the presence of boys, girls, siblingsin the schools. Possibly, it was a convenience for those responsible to have their children in the same house at the same time (Moraes, 2015).

A similar case was analyzed by Valdeniza Barra (2005). In 1864, a father filed suit against João Maria de Toledo, married to Elisa Carolina de Toledo Dantas, both public teachers of the Village of Penha de França, capital of São Paulo. Among the denunciations made by the father, it was stated that the schools operated in different houses, but that the teacher had the habit of teaching for his students in his house (place of the feminine school). The couple’s residence thus began to accommodate the two schools, an unauthorized practice, according to Barra28. The teacher gathered testimony from ten witnesses in his favor, collected mostly from those responsible for his students, reporting that they had good apprenticeship, and was able to remain in office after the contest.

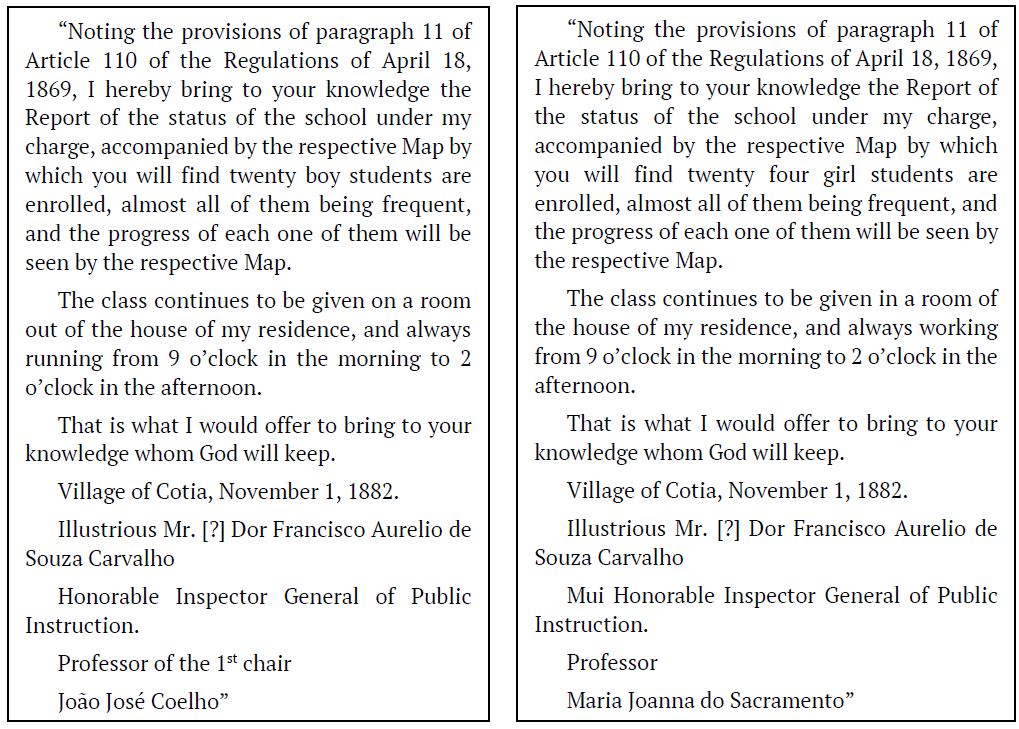

For Vidal (2010), one of the constituent elements of teacher experience is the intersubjective relationship established with different social (and school) actors at the various levels. Within the different spaces of sociability, she emphasizes “[…] the interpenetration between professional life and personal life” (Vidal, 2010, p. 720). It is possible to discuss the relationship between teachers Maria Joanna and João José and the influence (or not) of private life on the public life of teachers, especially on the teaching practice. Corroborating this analysis, two reports were located, one from Maria Joanna and another from João José, written in the same way with identical sentences29. Other reports from the couple are also very similar, but the ones below are highlighted. It seems to copy each other, despite the different handwriting on the original documents that match the letters of each teacher in their respective student enrollment books. The transcript of these documents (both located in APESP, Manuscripts, ref. CO5044) follows:

It is possible, in this case, to use the concept of teacher-homes, proposed by Munhoz and Vidal (2014, p.2) “[…] for the interpretation on the experiences of teachers with parental relationships, exercised in domestic spaces that were open to the public for conducting classes”. In the article, the authors investigated the trajectory of teachers from the 5th Comarca of São Paulo, later Paraná, in the first half of the nineteenth century, in the exercise of teaching, and the influence of kinship networks, having as main sources the frequency maps sent by teachers to the inspectorate of public education.

Munhoz and Vidal (2014, p. 15) pointed out that this “[…] path of interpretation is profitable when we observe very similar relations in the nineteenth century Brazil of predominance of parenting in the organization of the social fabric”. Analyzing the mapping of sibling teachers or parents and children, they interpreted it as a “[…] shared and transmitted know-how from teacher to teacher or executed by only one of them in the cases of teacher homes, as a task attributed to one of the subjects who worked together socially dividing work” (Munhoz & Vidal, 2014, p.13).

The connected trajectories of João José Coelho and Maria Joanna do Sacramento in the private environment are projected as an example of a teaching experience, materialized in the public instruction documents elaborated by them, constituted as “[…] fragments of school practices” (Munhoz& Vidal, 2014, p.10). In this perspective, it is possible to think of the interior of the family composed by this couple: in spite of exercising their function before marrying together, the immaterial inheritance - concept borrowed by the authors from Giovanni Levi (2000) - is in the practice of teaching, practice absorption and, when married, sharing knowledge.

However, although there is an approximation of becoming a teacher present in the reports, the couple differs in the act of qualifying their students in the enrollment lists (APESP, ref. EO2230, EO3182, ref. EO2234, EO3030). On each page of the enrollment books there was mandatory information that should be filled out by the teachers, according to the 1869 Regulations. But comparing the information given by Maria Joanna and João José about the students and their guardians, there is a significant difference. She did not attribute qualities to the girl students and fathers/mothers. She registered only the necessary data (the names) without qualifying them, except if the father or the mother had died, there followed the qualifications ‘deceased’. In turn, the male teacher placed the word ‘naïve’30, in front of the names of some of his students, or of some mothers the adjective ‘slave’ or ‘single’.

At a time when the slaveholding and patriarchal order prevailed, the absence of qualifiers in the books of Maria Joanna and their presence in the book of João José instigate the analysis. Other male teachers with collated books also qualified the students31, but Maria Joanna avoided registering such attributes. When reading her list there are only names of girls and their guardians. There would be no student daughter of slave or single mother in her class? Is it a gender issue, that is, the registration of girls would not have this information? Was it an intentional (and political) act or only strict compliance with what was requested by the regulation?

It seems plausible to consider the intentionality of the act, since the reports indicate that Maria Joanna and João José shared knowledge. In addition, in the books of Maria Joanna there were girls whose guardians were the mothers and not the fathers, which suggests that at least one of them was not married. João José, on the other hand, was master of at least two slaves, Caetano (Diário de São Paulo, 1871)32 and Vicencia (APESP, ref. EO3030)33. Perhaps this is why he qualified his students and mothers as ‘naïve’ and ‘slaves’, respectively. However, if Maria Joanna and João José were married, she probably used the services of these slaves. There is also the question of the Law of the Free Womb and the responsibility of the masters for the instruction of the ‘naïve’. Taking this law into account, the qualification by the teacher was perhaps a way of recording its fulfillment, since the first ‘naïve’ students were registered after 1881.

The teaching careers of Maria Joanna and João José have another common characteristic: they remained in the same chair since they became public teachers, retiring in the same year, 1885, she with 27 years of teaching and he with 25. According to Borges and Vidal (2016, p. 192), “[…] the time of work of the subjects involved in the schooling process [...] allows the establishment of more lasting relationships with the school’s insertion space”. In the case of the couple of teachers, it is important to point out that both were from Cotia and had assumed the First Chairs in the Village. On the one hand, they seemed to be in a comfortable position compared to other local teachers, and there was no reason to remove them. On the other, this favored their insertion in other public positions and a relative local influence.

If no documents on public life were found besides the teaching of Maria Joanna, the same cannot be said for João José Coelho, who obtained other functions, indicating the establishment of a network of relations gained through the exercise of teaching. Even before being a teacher, he had been captain of the municipal guard in 1855, a position he had only exonerated in 1864, which may suggest that his insertion in the teaching profession was the result of a ‘help’ from local potentates.

He was born in 1833 in Cotia, son of Luiz Antonio Coelho and Joaquina Maria Soares (Brasil batismos…, 1833). He was a student of Antonio Barreto, teacher of the only public chair in Cotia, when it was still part of the city of São Paulo territory (APESP, ref. CO4915, CO5044). Antonio Barreto was possibly his greatest influence on teaching practice and the friendship of the two followed over the years. João José Coelho passed an examination and joined the teaching profession in 1860, the year in which he took over the Male Chair of the Village of Cotia. After becoming a teacher, he was the postmaster and interim registrar of the justice of the peace and registrar of the justice of the peace. In the documents of public instruction after his retirement, his name also appeared in minutes of Municipal Council in the 1890s, as secretary. Before marrying Maria Joanna, he was a widower. He married Guilhermina Leite de Carvalho (Pedigree resources file, 2017), in 1853, with whom he had five children, all his and Maria Joanna’s students. He was also a teacher and tutor to some boys who lived with him34.

Two denunciations against João José were found in newspapers of the time. In a publication signed by Amoralidade (Correio Paulistano, 1873, p. 2), addressed to the General Inspector of Public Instruction, the teacher was accused of holding other public positions. The author alleged illegality, citing part of the 1869 Regulation that did not allow public teachers to hold other positions considered ‘incompatible’, and mentioning that another article ‘against certain abuses’ had previously been published in the newspaper. According to A moralidade, in addition to being a teacher, registrar of the justice of the peace (acting and effective) clerk and mail agent, João José also held the positions of public prosecutor and general and provincial collector. The author suggested that João José should resign from his teaching position, “[…] in what much the ill-fated Village of Cutia will gain!...”. However, in the Regulation there is no mention of what positions were considered incompatible with teaching. It should be noted that the complaint was published a few days after the teacher’s marriage to Maria Joanna. Perhaps these quarrels, in addition to being his second marriage, have influenced the couple to choose a ceremony in a particular oratory.

Less than two months later, another publication (Correio Paulistano, 1874, p.2) involved the name of João José. The note was signed by G. J. P. and reported that on December 31, 1873, he had also published an article in Correio Paulistanoin which he pointed out that “[…] he would not hesitate to present a complaint or anything against the teacher of the Village of Cutia” (we did not find this edition of the newspaper). In the publication of February 12, 1874, G.J.P. reported that on the 7th of that month he had given the president of the province a representation against the teacher for the regulation to be fulfilled. According to the author, “[…] it is only in this way that we will have a guarantee, and that it will not be done only that the village rulers determine in their high arrogance and dominion in the small hamlets [...]”, wishing that the “[…] scandals and patronages that went beyond practice”.

Unfortunately, the representation cited in the note was not found and we did not discover the unfolding of the case, but it is known that João José remained in the position of teacher of the First chair of the Village until 1885 and as agent of the mail until 1884, being exonerated by request. There is no official document citing João José Coelho, only those anonymous newspaper notes. Without neglecting the problematic of our archives, whose documentary set available to them is far behind all the documents produced, it may be possible to consider that João José enjoyed a shield in the municipality constituted by a network of relations derived from clientelism and transit in the various public spaces where he worked. However, these episodes allow us to point out aspects of the teacher’s behavior and the coexistence between teachers and the local population, as in other studies about the schooling process in the nineteenth century (Barra, 2005; Silva, 2007; Borges & Vidal, 2016).

Taking into account the ‘shielding’ hypothesis of João José Coelho, it can be said that this was not uncommon in public education, as shown by Barra (2005), analyzing the case of the female teacher of São Sebastião, Francisca Augusta Cortez, protected by the local lieutenant colonel, and Silva (2007, p. 187), investigating the schooling in the State of Permabuco, the case of Francisco Briguel Cezar de Menezes de Nazaré do Cabo, protected by Manoel do Rego Barros, a powerful man in the locality. Silva also analyzed some episodes in which public teachers were the target of complaints from residents. He stressed, however, especially for the teachers of the first half of the nineteenth century, that the complaints “[…] could come either from government agents, from communities and ordinary people. But they could also originate from the greed of some to the occupation of the post of public teacher”.

Similar case to that of João José was mentioned by Silva (2007). In 1853, a teacher from Pernambuco held the following positions: councilor, justice of the peace, general caretaker of orphans, lawyer, substitute delegate, assistant to the fiscal prosecutor, major of the national guard and consular agent of his most faithful majesty, according to the report of the General Director of instruction. For the author,

Such a multiplicity of positions makes it even more difficult for me to believe in the report, and it makes me think of the extreme link between that teacher and the local potentates, if he were not one of them. Incidentally, this is a strong possibility (Silva, 2007, p.191).

It seems that João José was one of the main pieces of Cotia’s political practices, enjoying a status that allowed to cross in several sectors. If he was the teacher Salambô referred to in his chronicle, adding up the elements presented here, we have a subject that is not adequate for what was advocated as an ideal of a teacher, at least with reference to the law. In article 110 of the regulation of 1869, “[…] of the obligations of teachers […]”, he had to “[…] give examples of politeness and morality in words and works […]” and not “[…] hold any public position or [exercise] any profession or industry incompatible with the exercise of teaching”. In addition to speaking immoralities, the teacher held various public positions, as denounced by Amoralidade and G.J.P.

Other male and female teachers

Besides the couple Maria Joanna and João José, other teachers taught in the schools of Cotia between 1870 and 1885. Some stayed for a short time in the place and soon were transferred to another municipality; others, born in Cotia, stayed and taught in more than one public chair.

Manoel de Moraes Pinto was hired in 1858 for the only public chair in Cotia, the male chair - shortly after the retirement of Cotia’s first public teacher, Antonio Barreto - but he stayed for a few months. Later he taught in Itapecerica and Araçariguama, neighboring municipalities to Cotia. In 1864, he was captain of the police guard of the Village of Cotia, leaving the position when assumed the chair of Itapecerica. He returned to work in Cotia as a teacher in 1880, removed from Araçariguama to the chair of the neighborhood of Várzea-Grande, where he remained until 1884. On request, he was transferred to the chair of Capitão Jerônimo, remaining there until the early 1890s. He became a lifelong teacher in 188735.

Marcolino Pinto de Queiroz worked for 30 years in the role of teacher, adding the chairs of the neighborhood of Itaqui (1871-1875) and Second Male Chair of the Village (1875-1901). He retired in 1901. Prior to acting in Cotia, he taught in Mogi-Mirim and Pirapora. In Cotia, he was also a music teacher, justice of the peace and Secretary of the Republican Party (PR). The functions, with the exception of the position of secretary of the PR, were carried out concurrently with that of teacher and assumed after his entry into the public teaching profession36.

As teacher of Itaqui, Marcolino was appointed adjunt attorney in the district of São Roque, according to a letter from district inspector Antonio Barreto to the general inspector of public instruction of 1874 (APESP, ref. CO5044). In 1875, he gained the position of teacher of the Second Male Chair of the Village of Cotia, transferred from the chair of Itaqui. During his time in the Second Chair of the Village of Cotia, and while João José Coelho was teaching in the First Chair, he always had more students than João José, except for the opening year, since the school began to work in May. At the beginning of 1876, seven students of João José Coelho transferred to Marcolino’s chair (APESP, ref. EO2918). Among them were the children of politically influential figures, which may indicate a preference for Marcolino or the location of the school.

Severiano José de Ramos spent five years in Cotia, teaching in the chair of Várzea-Grande (from 1871 to 1876). He stood out as the first teacher of the municipality to attend the Normal School, enrolling in November 1875. Only seven months later, in June 1876, he was transferred to the chair of Lageado, district of Penha de França, in the capital of São Paulo (Diário de São Paulo, 1875, 1876). It took advantage of the incentive given by the legislation of the period. According to section II of Law 9 of March 22, 1874, which specifically dealt with the creation of the Normal School, public teachers could enroll as a normal student, establishing some advantages:

Art. 8.º [...]

§ 14. - The current Public Teachers can enroll in the Normal School, guaranteeing the Province their salaries for two years.

Art. 9.º - Students of the Normal School who, obtaining a certificate of habilitation, will be considered for life in the Chairs.

In addition to the guarantee of two years of salary and life tenure to those qualified, only public teachers and the admittedly poor students would study for free. The others were to pay a sum to the province. Subsequently to Severiano, in 1885, another female teacher who had studied at the Normal School came to practice in Cotia: Analia Franco, teacher of the First Female Chair in the Village from 1885 to 1887.

Teacher very present in the schooling process of Cotia in the second half of the nineteenth century, José Custódio de Queiroz taught for 25 years in the public chairs of the municipality of Sorocamirim, Carapicuíba, Capitão Jerônimo, Lavapés and First Chair of the Village. Of all, he left by removal, except for the chair of Carapicuíba, from which he asked for exemption and the chair of Cotia, where he retired. He was nominated for all positions and did not pass examinations, configuring what we can call a ‘joker’ teacher in schools where the vacancy was not filled by a teacher after examination37.

According to the newspapers, he held other positions, especially after retirement in 1898. He was a police chief, assistant captain and captain-helper of the national guard, first deputy to the federal judge and member of the Cotia PR directory. In 1875, he was a weights and measures gauge, a function that also had to be exercised by public teachers, according to the Posture Regulation of the Village of Cutia of 1886. He became a life teacher in 1885 after taking the First Chair in the Village. In a note about his death at age 70, he was remembered only for his role as a teacher (Correio Paulistano, 1922).

Antonio Manoel Vieira joined the teaching profession in August 1872, and that same year he took the chair of the neighborhood of Sorocamirim, remaining until 1876, when he was removed to the chair of Campo Limpo, municipality of Santo Amaro (Diário de São Paulo, 1872; Correio Paulistano, 1876).

João Rodrigues de Jesus assumed the chair of Carapicuíba in 1880 and there are reports of him in this chair until 1881. Despite signing as teacher of Carapicuíba, since 1878, the chair had been transferred to Barueri, a neighborhood of the municipality of Parnaíba (neighboring Cotia), which also served the Carapicuibanos. In 1886 and 1888, the name of João Rodrigues de Jesus is as teacher of the Second Chair of the Village of Parnaíba (Almanach da Província de São Paulo, 1886; Correio Paulistano, 1888).

In the year 1880, João Cezar de Abreu e Silva was appointed teacher of primary school of the chair of Sorocamirim. He did not, however, hold office. The government report states that this chair was ‘without students’ (public instruction report in the province of São Paulo, 1880). In 1884, the name appears connected to the masculine chair of Perus, neighborhood of São Paulo city (Almanach Administrativo, Comercial e Industrial da Provincia de São Paulo, 1884). Sorocamirim chair was also occupied by João Maria Thomaz from 1882 to 1888, who did not hold other public office, at least according to the newspapers consulted38.

Joaquim Chrispim de Oliveira was a public teacher for about 30 years, retiring in 1913 in the Second Chair of the Village of Cotia. He began to teach in the municipality, when assuming the chair of the neighborhood of São João in 1882, where he remained until at least 1887, date of the last note of newspaper where his name is associated with this chair and that informs on a license of 40 days for treatment of health. The following year, he held a suspended position for the suppression of the school in the Lavapés neighborhood, where he was an intermediate teacher. In 1909, he taught in the chair of the neighborhood of Graça, in Cotia, when was removed by decree for the Second Male Chair of the Village. He died suddenly at the age of 69 in 1921. On the note about his death it is only that he was a ‘retired teacher’. However, in news of 1918, he had been appointed first substitute of federal judge in Cotia, position that possibly never had assumed39.

The Second Female public chair of Cotia was created in 1884 (26 years after the first, in 1858), and was assumed by Catharina Etelvina Pedroso (Correio Paulistano, 1884). There is no more information in newspapers about her public life. About her private life, in the enrollment book of the first female chair in the Village (APESP, ref. EO2230), when she was still a student, she appears to be the daughter of José Joaquim Pedroso. Captain José Joaquim Pedroso was mayor of the city from 1865 to 1868, a councilor, judge of the peace, subdelegate, voter40, and possibly Cotia’s greatest slave owner at the time. She was the sister of José Joaquim Pedroso Junior, mayor, road inspector, among other functions. Therefore, she was sister and daughter of influential figures with public positions in the municipality.

Catharina was a pupil of Maria Joanna do Sacramento between 1870 and 1877 and quite possibly had the teacher as the greatest or one of her greatest references as a teacher. For Borges and Vidal,

The long trajectory developed in the same school may have contributed to the development of educational experiences that have become a reference among teachers - it is important to note that they also helped to train teachers through ‘training by practice’ established by the 1854 regulation - and to consolidate a certain position in society (Borges & Vidal, 2016, p.194).

According to Vidal (2010, p. 712), another constituent element of the teaching experience is the school trajectory of teachers, the “[…] experience accumulated by the teacher subject throughout his life […]”, which encompasses his experience as a teacher as well as his experiences as a student since the beginning of schooling.

In October 1885, João Baptista Cepellos took the chair of Várzea-Grande, where he taught until October 23, 1887 when he died. His teaching experience in Cotia, however, began in 1874, when he opened a private school “[…] without proceeding with the provisions of Article 154 of the Regulation of April 18, 1869” (APESP, ref. CO5044), since he did not have the qualification to teach. Apparently, the school was closed by the district inspector41. This teacher was the father of Manoel Baptista Cepellos, consecrated poet of Cotia.

Anália Emilia Franco42 was at the head of the First Female Chair in the Village of Cotia from 1885 to 1887. Before moving to Cotia, she lived in São Carlos do Pinhal (now São Carlos), where she taught at School Santa Cecília, primary and secondary education for girls, founded in 1882 by Anália Franco (Almanach Administrativo, Commercial e Industrial, 1885). During the period in which she was a teacher in Cotia, she was granted advantages by law nº 78 of April 6, 1885 to normal teachers who continued to practice public teaching. She went on leave for at least six months to take care of a dyspepsia in Rio de Janeiro, according to letters from the 1886 Inspectorate, during which period she was replaced by Leonilbes [?] C. de Souza Gouvêa and Maria José de Toledo Aymberé (APESP, ref CO5044). In August of 1887, Analia was transferred to the chair of Taubaté, in the Paraíba Valley, more than 220 kilometers from Cotia (Correio Paulistano, 1885, 1887).

Teacher since 1872, Anália Franco has been enrolled in the Normal School in 1877, graduating in 1878. During her career, she became involved in the education of daughters of slaves, taught in some municipalities of São Paulo, created several philanthropic establishments, collaborated with newspapers and magazines with articles on disadvantaged classes, founded her own magazine, Álbum de Meninas: uma revista literária e educative dedicada às jovens brasileiras43, among other activities. However, the work that had Anália Franco as subject and object of research does not mention her passage by Cotia, even claiming a gap in her work in teaching. Therefore, this investigation contributed to unveil part of her history between 1885 and 1887.

Final considerations

After discussing the trajectories of 11 male teachers and three female teachers, we can affirm that five public male teachers from the State of São Paulo went through one or more sectors, performing other functions, sometimes related to public security, or to justice, but also in the arts, private education or integrating political party. They were João José Coelho, Manoel de Moraes Pinto, Marcolino Pinto, José Custódio de Queiroz and João Baptista Cepellos. Only one female teacher, Anália Franco, had activities in philanthropy and journalism. Three male teachers took functions concomitant to the office of public teacher: João José Coelho, Marcolino Pinto and José Custódio de Queiroz.

According to data from the Census of 1872, in Cotia, of 5,024 inhabitants, only 263 knew how to read, which gave literates the possibility of entering the public service. But with the exception of João José Coelho, no other male teacher held public position before becoming a teacher, demonstrating that experience as a teacher and the networks of relationships then established contributed to the transit of these subjects in other segments of the public service.

For Borges (2014), the teachers, on the one hand, were agents of the administration.

On the other hand, teachers knew that they possessed the possibility of exercising a power, an agency - propitiated by the autonomy of which they were imbued in the exercise of their profession, but also conferred by their condition of being in closer contact with the people - in favor of their own interests, be they professional, economic, social or political (Borges, 2014, p. 105).

According to Hilsdorf (1998), the teachers were in the layer of those who were not of the bourgeoisie, nor of the popular layer. According to Silva (2007, p. 125), the public teaching profession worked as “[…] one of the components of clientele networks and as an individual access door to obtaining the benefits of the State”. The teacher was the “[…] bearer of significant social prestige among the most modest layers of society, and significantly valued for entry into local clientele networks” (p. 173-174).

This network of relations seemed to have a strong influence mainly on the trajectory of João José Coelho, who, despite being denounced for the excess of positions and for other ‘peculiarities’, continued to work in the teaching profession. The collected sources allowed to construct the figure of a man with local powers that ‘shielded’ him, a subject of prestige and belonging to the nucleus of the political potentate. The marriage with Maria Joanna provided the creation of a teacher home, with some common professional practices.

The issue of teacher relocation should be highlighted. In Cotia, with the exception of João José Coelho, Maria Joanna do Sacramento and Catharina Etelvina Pedroso, apparently comfortable with schools and workplaces (located in the municipality where they were born and raised, and based in the Village), all teachers removed themselves from schools, some with more, others with less frequency. In Rio de Janeiro,

[…] transit through different regions of the city allowed the teacher to have greater knowledge of the terrain in which he operated and, in some way, to strengthen teaching agencies and the ties of solidarity among his colleagues, since the questions demanded by one could be better understood by others who already would have passed through the same region. The knowledge acquired by the ‘rotation of the Chairs’ could also give the teacher an important experience to perform in the social and political life of the city (Borges, 2014, p. 77-78, author’s emphasis).

One of the teachers from Cotia, José Custódio de Queiroz, went through five local schools in different neighborhoods. Certainly, these displacements favored him a great knowledge about the municipality, which possibly impacted the exercise of his functions like police chief and justice of the peace.

Working with the concept of ‘discomfort’, Dayana Lima (2014) investigated the reasons for removals of effective primary teachers from Recife and Olinda between 1860 and 1880 and concluded that it was a common phenomenon in these municipalities, with removals and medical licenses (these, especially, of teachers) the main reasons. Lima understood as discomfort “[…] the problematic practices described by the public authorities in relation to the needs of teacher’s removal in the exercise of their work” (p.17-18), noting that medical licenses, school transfers, absences from work, substitutions of teachers and drop-out cases were commonplace in teaching life.

According to the sources, in Cotia, the phenomenon of discomfort was also present among teachers, especially among teachers in the neighborhoods, who generally transferred with less than four years of office. The transfers were possibly related to the characteristic of caipira neighborhoods, marked by rusticity, by the minimum social and minimum vital (Candido, 2001a). Teachers preferred to move to other municipalities, the Village, or neighborhoods closer to it. Of the 14 teachers presented, eight remained teaching in Cotia. Six went to other municipalities, suggesting that perhaps Cotia was a place of passage waiting for a more opportune place to teach. The discomfort was also present in the leaves to take care of diseases, as in the case of Analia Franco, who went to Rio de Janeiro to treat dyspepsia; of JoaquimChrispim who took a 40-day leave, in addition to other teachers with shorter licenses.

Going through the trajectory of these teachers proved to be an efficient way of approaching and understanding the specificities of Cotia’s schooling practices in the third quarter of the nineteenth century. In this composition of characters, we identified the presence of teachers until then anonymous and also of the consecrated teacher Anália Franco, who acted in the municipality, in a passage unknown by a historiography of education focused on figures of greater visibility.

REFERENCES

Almanach da Província de São Paulo. (1886). p. 397 [ Links ]

Almanach Administrativo, Commercial e Industrial. (1885). p. 490. [ Links ]

Almanach Administrativo, Comercial e Industrial da Provincia de São Paulo. (1884). [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Manuscritos. Lata de Ofícios Diversos da Instrução Pública de Cotia e de outros municípios, número de referência CO5044, Relatório de inspetor de distrito de 1869. [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Ofícios Diversos, Ofícios Diversos de Cotia, ref. CO1007. Ofício da Câmara Municipal de 30 jun. 1858. [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Manuscritos. Lata de Ofícios Diversos da Instrução Pública de Cotia e de outros municípios, número de referência CO5044. Relatórios dos professores João José Coelho e Maria Joanna do Sacramento de 1 nov 1882. [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Livros de Matrícula da Primeira Cadeira Masculina da Vila de Cotia, número de referência EO2230 (1870-1877), EO3182 (1878-1885); e da Cadeira Feminina da Vila de Cotia, ref. EO2234 (1870-1877), EO3030 (1878- 1885). [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Livro de Matrícula da Primeira Cadeira Masculina da Vila de Cotia, número de referência EO3030, 1878-1885. [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Manuscritos. Lata de Ofícios Diversos da Instrução Pública de Cotia e de outros municípios, Mapas de frequência de 1839, 1843 a 1846, números de referência CO4915 e CO5044. [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Manuscritos. Lata de Ofícios Diversos da Instrução Pública de Cotia e de outros municípios, Mapas de frequência de 1839, 1843 a 1846, números de referência CO4915 e CO5044 . [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Manuscritos. Lata de Ofícios Diversos da Instrução Pública de Cotia e de outros municípios, Mapas de frequência de 1839, 1843 a 1846, números de referência CO4915 e CO5044 . [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Livros de Matrícula, ref. EO2918, Livro de Matrícula da 2ª Cadeira da Vila de Cotia, 1875-1882. [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Livro de Matrícula, ref. EO2230, Livro de Matrícula da Escola Feminina da Vila de Cotia, 1870 a 1879. [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Manuscritos. Lata de Ofícios Diversos da Instrução Pública de Cotia e de outros municípios, ref. CO5044. [ Links ]

Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo [APESP]. Série Instrução Pública - Manuscritos. Lata de Ofícios Diversos da Instrução Pública de Cotia e de outros municípios, ref. CO5044 . Ofício do Inspetor Geral da I. P. para o Presidente da Província de 21 agosto 1886. [ Links ]

Azevedo, A. R. de. (2010). “Os espíritas e Anália Franco: práticas de assistência e escolarização da infância no início do século XX”. Cadernos de História Educação, 9(2), 292‐307. [ Links ]

Barra, V. (2005). Briga de vizinhos: um estudo dos processos de constituição da escola pública de instrução primária na província paulista (1853-1889) (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Borba, F. S. (Org.) (2004). Dicionário Unesp do português contemporâneo. São Paulo, SP: Editora Unesp. [ Links ]

Borges, A. (2014). A urdidura do magistério primário na Corte Imperial: um professor na trama de relações e agências (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Borges, A., & Vidal, D. G. (2016). Racionalização da oferta e estratégias de distinção social: relações entre escola, distribuição espacial e família no Oitocentos (Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 16, (2 [41]), 175-201. [ Links ]

Brasil (Império). (1871). Lei nº 2.040, de 28 de setembro de 1871. Lei do Ventre Livre. Recuperado de:http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lim/LIM2040.htm [ Links ]

Brasil Batismos, 1688-1935. (1833, 02 de fevereiro). FamilySearch, registro de nascimento de Joao Coelho. Cotia, SP. Recuperado de:https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XJPB-QXJ [ Links ]

Brasil Casamentos, 1730-1955. (1873, 08 de novembro). FamilySearch, registro de Casamento de Joao Jose Coelho e Maria Joanna Do Sacramento. Cotia, SP. Recuperado de:https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/V2KW-T22 [ Links ]

Candido, A. (1992). A vida ao rés-do-chão. In A. Candido, A. (Org.). A crônica: o gênero, sua fixação e suas transformações no Brasil (p. 13- 22). Campinas, SP: Ed. Unicamp. [ Links ]

Candido, A. (2001a). Os parceiros do Rio Bonito: estudo sobre o caipira paulista e a transformação dos seus meios de vida. São Paulo, SP: Editora 34. [ Links ]

Candido, A. (2001b). Entrevista com o autor sobre os caipiras. In I. G. Ferraz (Dir.). Intérpretes do Brasil. Documentário/DVD duplo. [ Links ]

Chalhoub, S., Neves, M. de S., & Pereira, L. A. M. (Orgs). (2005). História em cousas miúdas: capítulos de história social da crônica no Brasil. Campinas, SP: Ed. da Unicamp. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano. (1869, 15 de maio). [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1873, 20 de dezembro). p.2. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1874. 12 de fevereiro). p.2. [ Links ]

Diário de São Paulo. (1875, 30 de novembro). p. 3. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1876, 4 maio). p. 2. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1884, 12 de março). p. 3. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1885, 27 de maio). p. 2. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1887, 21 de agosto). p. 2. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1888, 25 de setembro). p. 1. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1922, 8 de novembro). p. 5. [ Links ]

Diário de São Paulo . (1872, 23 de agosto). p. 3. [ Links ]

Diário de São Paulo . (1871, 05 de julho). p. 2. [ Links ]

Diário de São Paulo . (1876, 19 de agosto). p. 1-2. [ Links ]

Ginzburg, C., & Poni, C. (1991). O nome e o como: troca desigual e mercado historiográfico.In: C. Ginzburg, E. Castelnuovo & C. Poni (Org.). A micro-história e outros ensaios (p.169-178). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Bertrand Brasil. [ Links ]

Gouvêa, M. C. S. (2003). Os fios de Penélope: a mulher e a educação feminina no século XIX. Anais da 26ª Reunião Anual da Anped.Poços de Caldas, MG. [ Links ]

Hilsdorf, M. L. S. (1999). Tempos de escola: fontes para a presença feminina na educação de São Paulo - século XIX. São Paulo, SP: Ed. Plêiade. [ Links ]

Hilsdorf, M. L. S. (2003). À Sombra da Escola Normal: achegas para uma outra história da profissão docente. In Anais do25ºISCHE, International Standing Conference for the History of Education, São Paulo, SP. [ Links ]

Hilsdorf, M. L. S. (1998). Mestra Benedita ensina primeiras letras em São Paulo (1828-1858). Sociedade Portuguesa de Ciências da Educação. Leitura e Escrita em Portugal e no Brasil, 1500-1970 (Vol. II, p. 521-528). Porto, PT. [ Links ]

Instituto Geográfico e Cartográfico do Estado de São Paulo [IGC]. (1995). Municípios e distritos do Estado de São Paulo. São Paulo, SP: IGC. [ Links ]

Levi, G. (2000). Herança imaterial: trajetória de um exorcista no Piemonte no século XVII. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira. [ Links ]

Lima, D. R. P. (2014). Sinais do “desconforto” no exercício da docência pública em Recife e Olinda (1860-1880)(Dissertação de Mestrado em Educação). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife. [ Links ]

Lodi-Correa, S. (2009). Anália Franco e sua ação socio-educacional na transição do Império para a República. 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas. [ Links ]

Monteiro, E. C. (2004). Anália Franco: a grande dama da educação brasileira. São Paulo, SP: Madras. [ Links ]

Moraes, F. (2015). O processo de escolarização pública na Vila de Cotia no contexto cultural caipira (1870-1885) (Dissertação de Mestrado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo . [ Links ]

Munhoz, F. G. (2012). Experiência docente no século XIX:trajetórias de professores de primeiras letras da 5ª comarca da Província de São Paulo e da Província do Paraná (Dissertação de Mestrado em educação). Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo . [ Links ]

Munhoz, F. G., & Vidal, D. G. (2014). Experiência docente oitocentista e transmissão familiar do magistério na 5ª Comarca da Província de São Paulo. Anais do10ºCongresso Luso-Brasileiro de História da Educação (p. 1-17), Curitiba, PR. Publicado em MUNHOZ, F. G; VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves. Experiencia docente y transmisión familiar del magisterio en Brasil. Revista Mexicana de Historia de la Educación, v. III, p. 125-157, 2015. [ Links ]

Ofício do inspertor de instrução pública ao Insp. Geral. (1874, 19 de janeiro). [ Links ]

Oliveira, E. C. (2007). Anália Franco e a Associação Feminina Beneficente e Instrutiva: idéias e práticas educativas para a criança e para a mulher (1870 - 1920) (Dissertação de Mestrado em Educação). Universidade São Francisco, Itatiba. [ Links ]

Pedigree resource file [Arquivo de recursos de linhagem]. (2017). FamilySearch, Guilhermina /Leite de Carvalho. Recuperado de: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:2:SPDP-MT8 [ Links ]

Petrone, P. (1995). Aldeamentos paulistas. São Paulo, SP: Edusp. [ Links ]

Pinto, A. M. (1900). A cidade de S. Paulo em 1900: impressões de viagem. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Imprensa Nacional. [ Links ]

Portela, D. (2016). A trajetória profissional da educadora Anália Emília Franco em São Paulo (1853-1919) (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo . [ Links ]

Salambô. (1872, 27 de outubro). Sobre o que vae pela Paulicéa - VII. Correio Paulistano . p. 2. [ Links ]

São Paulo (Estado). (1874). Regulamento de 18 de abril de 1869 - para Instrução Pública e particular da Província. São Paulo, SP: Tipografia Correio Paulistano . [ Links ]

São Paulo (Estado). Assembleia Legislativa do Estado de São Paulo. (1874). Lei nº 9 de 22 de março de 1874. Recuperado de: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/lei/1874/lei-9-22.03.1874.html [ Links ]

São Paulo (Estado). Assembleia Legislativa do Estado de São Paulo. (1846). Lei nº 34, de 16 de março de 1846. Recuperado de: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/lei/1846/lei-34-16.03.1846.html [ Links ]

São Paulo. Assembleia Legislativa. (1874). Resolução nº 57. Recuperado de: http://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/resolucao/1874/resolucao-57-28.04.1874.html [ Links ]

São Paulo. Assembleia Legislativa. (1886). Resolução nº 136. Recuperado de: http://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/resolucao/1886/resolucao-136-08.06.1886.html [ Links ]

Silva, A. M. P. (2007). Processos de construção da escolarização em Pernambuco, em fins do século XVIII e primeira metade do século XIX. Recife, PE: EdUFPE. [ Links ]

Vidal, D. G. (2010). A docência como uma experiência coletiva: questões para debate. In A. Dalben, J. Diniz, L. Leal & L. Santos (Orgs.), Convergências e tensões no campo da formação e do trabalho docente: didática, formação de professores, trabalho docente (p. 711-734). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Wissenbach, M. C. (1998). Sonhos africanos, vivências ladinas: escravos e forros em São Paulo (1850-1888). São Paulo, SP: Hucitec. [ Links ]

22In the period from 1870 to 1885, Cotia comprised the territories of the current municipalities of Cotia, Itapevi, Vargem Grande Paulista, Jandira and part of Embu das Artes and Carapicuíba (IGC-SP, 1995), currently belonging to the metropolitan region of São Paulo; and also of a small part of the capital, since it was a limit with this one in the region of the JaguarahéStream, now located in the district of Jaguaré in São Paulo (Report presented to the Excellency President of the Province of São Paulo, 1888; Pinto, 1900).

23According to Candido (2001a and 2001b), the territory of São Paulo in this case covers approximately the region called Paulistânia: São Paulo, part of Minas Gerais, Paraná, Goiás and MatoGrosso, with the related area of rural Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo.

24Before the railways, trade in goods was carried out by muleteers in regions where there were no alternatives for sea or river navigation for distribution. The interior regions, distant from the coast, depended for a long time on this means of transportation by mules. This kind of trade in goods was called tropeirismo, because the muleteers displaced themselves in troops.

25For more information, cf. Candido (1992), and specifically on the use of chronicle in historical studies, cf. Chalhoub, Neves, Pereira (2005).

26Resolutions (posture articles) prohibiting the carrying of weapons to people who have not used them for work.

27Collection of nineteenth-century periodicals (consulted newspapers and almanacs). Available in the Digital Newspaper Library of the National Library (www.hemerotecadigital.bn.br).

28There is no mention of the law in this passage of the author’s text, however, the fact occurred in 1864. In Law 34 of 1846, it was stated in article 8: “The promiscuous frequency of both sexes in a school is only allowed when there are no different schools for both”. Subsequent to this law, came the Regulation of 1851 for Public Instruction, which deals with this question only for private instruction: “Art. 23. The directors of girls’ colleges where male students are admitted, or same-sex residents over the age of ten, except the principal’s husband, are subjected to the same fine”. Therefore, Article 8 of Law of 1846 was still in force.

29Other teachers in Cotia had similar ways of phrasing the sentences-perhaps there was a model report circulating locally-but there were also the reports that resembled no other.

30According to the Law of the Free Womb (Number 2040 of September 28, 1871), among other things, the children of slave women who were born as of September 28, 1871, were considered free, indicating the measures regarding raising and treatment of these unborn - commonly called ‘naïve’.

31In the dissertation (Moraes, 2015), six books of four chairs, two of the 1st Male Chair of the Village, two of the 1st Female Chair of the Village, one of the 2nd Male Chair of the Village and one of the Chair of Capitão Jerônimo, dating from 1870 to 1885, are analyzed.

32Alist with the names of men who worked in the repair and maintenance of the road from Cotia to the capital, included the slave of João José Coelho, called Caetano.

33In it, Vicencia was the mother of two students of João José who also lived with him. In the records of baptism of the children of Vicencia it is stated that she was single and slave of João José Coelho.

34Sources on the trajectory of João José Coelho: Correio Paulistano. (1855, 28 de abril). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1859, 23 de julho). p. 1; Ofício de 15/02/1861. APESP, Série Ofícios Diversos, Ofícios Diversos de Cotia, ref. CO1008; Correio Paulistano. (1863, 19 de agosto). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1864, 8 de julho). p. 1; Ofício de 2/11/1866. APESP, Série Ofícios Diversos, Ofícios Diversos de Cotia, ref. CO1008; Diário de São Paulo. (1867, 6 de fevereiro). p. 3; Correio Paulistano. (1869,4 de fevereiro). p. 1; Diário de São Paulo. (1872,22 de agosto). p. 2; Diário de São Paulo. (1878,9 de agosto). p. 1; A Constituinte de 6/12/1879, p. 1; Correio Paulistano. (1884,6 de janeiro). p. 1; Ata de installação do Conselho Municipal da Villa de Cotia, 13/09/1887; Ofício do presidente do Conselho Municipal de 20/06 e 20/07/1890 ao Diretor de I. P. APESP, Série Instrução Pública - Manuscritos, ref. CO5044.

35Sources on thetrajectory of Manoel de Moraes: Correio Paulistano. (1858,14 de novembro). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1864,8 de julho). p. 1; Diário de São Paulo. (1867,16 de novembro). p. 3; Diário de São Paulo. (1868,18 de setembro). p. 1; Diário de São Paulo. (1869,4 de fevereiro). p. 3; Amanak da Província de São Paulo. (1873). p. 392; Correio Paulistano. (1884,6 de março). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1887,10 de julho). p. 1; Correio Paulistano. (1891,25 de março). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1893,19 de janeiro). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1894,4 de fevereiro). p. 2.

36Sources on the trajectory of Marcolino available at: <http://www.jusbrasil.com.br/diarios/3667749/pg-17-diario-oficial-diario-oficial-do-estado-de-sao-paulo-dosp-de-04-01-1901>Acessed in: 7Aug. 2015; Diário de São Paulo. (1869,30 de outubro). p. 3; Diário de São Paulo. (1869,6 de novembro). p. 2; Diário de São Paulo. (1869,14 de novembro) ;Correio Paulistano. (1870,26 julho). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1871,15 de abril). p. 3; Correio Paulistano. (1872,23 de agosto). p. 2; Almanak da Província de São Paulo. (1873). p. 144-145; Diário de São Paulo. (1878,9 de agosto). p. 1; Correio Paulistano. (1915,25 de novembro). p. 5; Correio Paulistano. (1915,26 de novembro). p. 4; Correio Paulistano. (1915,12 de outubro).

37Sources on the trajectory of José Custódio: Diário de São Paulo. (1871,21 de dezembro). p. 1; Diário de São Paulo. (1872,28 de agosto). p. 2; Diário de São Paulo. (1875,9 de julho). p.1; Correio Paulistano. (1877,28 de julho). p. 2; Jornal da Tarde (SP). (1879, 19 de julho). p. 3; Ofício do inspetor de distrito Benedicto José d’Oliveira de 20/03/1884 ao inspetor geral da I.P.APESP, série I.P. - Manuscritos, ref. CO5044; Correio Paulistano. (1885,27 de maio). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1885, 11 de setembro). p. 1;Correio Paulistano, (1903,26 de janeiro). p. 1; Correio Paulistano. (1903, 2 de fevereiro). p. 1; Correio Paulistano. (1904,10 de outubro). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1907,17 de novembro). p. 1; Correio Paulistano. (1915,7 de novembro). p. 7; Correio Paulistano. (1915, 12 de outubro). p. 4; Correio Paulistano. (1922,8 de novembro). p. 5.

38Sources on the trajectory of João Maria Thomaz: Correio Paulistano. (1876,14 de novembro). p. 2; Diário de São Paulo. (1876,20 de outubro). p. 3; Correio Paulistano. (1880, 8 de setembro). p. 2; Jornal da Tarde (SP). (1881, 12 de julho). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1888,2 de fevereiro). p. 3.

39Sources on the trajectory of Joaquim Chrispim: Correio Paulistano. (1887,20 de setembro). p. 1; Correio Paulistano. (1898,30 de julho). p. 1; Correio Paulistano. (1899,7 de abril). p. 2; O Commercio de São Paulo. (1909,18 de março). p. 2; O Commercio de São Paulo. (1913,25 de julho). p. 2; Correio Paulistano. (1921,17 de maio). p. 4; Correio Paulistano. (1918,23 de janeiro). p. 4.

40Cf. Almanak da Província de São Paulo (1873); local newspaper Cotiato do dia. Available at:<http://cotiatododia.com.br/retro/cotiatododia2007/guias_publicos/vereadores_guiasdecotia.htm>Acessed in 14july2017; Câmara dos Vereadores. Available at: http://www.camaradecotia.sp.gov.br/presidentes.php

41Sources on the trajectory of João B. Cepellos: Correio Paulistano. (1885,5 de março). p. 3;Correio Paulistano. (1885,19 de junho). p. 1; Relatório do Inspetor Geral para o Presidente da Província de 21/01/1888, APESP, Série I.P. - Manuscritos, CO5044.

42For more information on Analia Franco see Monteiro (2004), Oliveira (2007), Lodi-Correa (2009), Azevedo (2010) e Portela (2016).

Received: November 13, 2017; Accepted: August 09, 2018

texto en

texto en