Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1519-5902versión On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.18 Campinas 2018 Epub 01-Jun-2018

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v18.2018.e035

Articles

Places of teaching in the Imperial Court: the protagonism of the primary teacher Candido Matheus de Faria Pardal

1Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Duque de Caxias, RJ, Brasil

Abstract: This study intended to analyze the trajectory of the primary public teacher Candido Matheus de Faria Pardal (1818-1888), articulating the teaching and his performance by different spaces and associations of social, political, economic, religious and recreational character, in the Capital of the Brazilian Empire. The art of teaching, the spaces in which he acted and the relations constituted with the most varied subjects enabled the teacher to gain experience and visibility in the Court and in other provinces of the country. His trajectory allows him to compose a dynamic scenario around the teaching profession in the 19th century that gives prominence to the activity of teaching, but also to associate, amuse, elect, order, among many others, showing heterogeneous ways of being and being in the city. To perform the research were used newspapers of the 19th century press, available digitally in the Brazilian national library; handwritten documents of the General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro; Reports of the General Inspectorate of Primary and Secondary Education of the Court; documents from the Archives of the D. João VI Museum and the Archives of the Pedro II College. By tracking the ‘name string’, it was possible to gather a variety of information about the life of this teacher analyzed in sets of scales that organize the reflection in two parts. The first deals with the performance of the Candido Pardal in the classroom; the second analyzes his performance in the city unfolding in the local, political, social, economic, religious and recreational spheres.

Keywords: history of education; teachers; life trajectory; Brazilian Empire.

Resumo: Este estudo apresenta uma análise da trajetória do professor Candido Matheus de Faria Pardal (1818-1888) articulando a docência e sua atuação por diferentes espaços e associações de caráter social, político, econômico, religioso e recreativo, na capital do Império brasileiro. A arte de ensinar, os espaços onde atuou e as relações constituídas com os mais variados sujeitos possibilitaram ao professor ganhar experiência e visibilidade na Corte e em outras províncias do país. Sua trajetória permite compor um dinâmico cenário em torno do ofício docente no século XIX que dá relevo à atividade de ensinar, mas também a de associar-se, divertir-se, eleger, ordenar, entre tantas outras, apontando heterogêneos modos de ser e estar na cidade. Para realização da pesquisa foram usados jornais da imprensa oitocentista, disponibilizados pela Hemeroteca da Biblioteca Nacional; documentos manuscritos do Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro; Relatórios da Inspetoria Geral de Instrução Primária e Secundária da Corte; documentos do Arquivo do Museu D. João VI e do Arquivo do Colégio Pedro II. Ao rastrear o ‘fio do nome’ foi possível levantar uma variedade de informações a respeito da vida deste professor, analisadas em jogos de escalas que organizam a reflexão em duas partes. A primeira trata da atuação de Pardal em sala de aula; a segunda analisa a sua atuação na cidade se desdobrando nos âmbitos local, político, social, econômico, religioso e recreativo.

Palavras-chave: história da educação; professores; trajetória de vida; Brasil Império

Resumen: Este estudio presenta un análisis de la trayectoria del profesor Candido Matheus de Faria Pardal (1818-1888), articulando la docencia y su actuación por diferentes espacios y asociaciones de carácter social, político, económico, religioso y recreativo, en la Capital del Imperio brasileño. El arte de enseñar, los espacios en que actuó y las relaciones constituidas con los más variados sujetos permitieron al profesor ganar experiencia y visibilidad en la Corte y en otras provincias del país. Su trayectoria permite componer un dinámico escenario alrededor del oficio docente en el siglo XIX que da relieve a la actividad de enseñar, pero también a asociarse, divertirse, elegir, ordenar, entre tantas otras, apuntando heterogéneos modos de ser y estar en la ciudad. Para la realización de la investigación se utilizaron periódicos de la prensa ochocentista, disponibles en la Hemeroteca de la Biblioteca Nacional de Brasil; documentos manuscritos del Archivo General de la Ciudad de Rio de Janeiro; Informes de la Inspectoría General de Instrucción Primaria y Secundaria de la Corte; documentos del Archivo del Museo D. João VI y del Archivo del Colegio Pedro II. Al rastrear el "hilo del nombre" fue posible encontrar una variedad de informaciones acerca de la vida de este profesor, analizadas en juegos de escalas que organizan la reflexión en dos partes. La primera trata de la actuación de Pardal en el aula; la segunda analiza su actuación en la ciudad que se desdoblan en los ámbitos local, político, social, económico, religioso y recreativo.

Palabras clave: Historia de la Educación; Profesores; Trayectoria de vida; Brasil Imperio

Introduction

Candido Matheus de FariaPardal (1818-1888), considered by the teaching staff at the time a ‘dean of public professors’, practiced the teaching profession in the municipality of the Court, capital of the Empire, for approximately 42 years. He worked in primary, secondary and vocational education. Hetaught to read and write, drawing, calligraphy and grammar, in public and private institutions, for boys and girls. He used the mutual method and then the mixed method. He was director of the municipal schools opened in the 1870s, examiner and writer of compendia, member of public contests and various exams. Due to the long permanence in teaching, the teacher had the possibility of witnessing a series of changes and also of permanence in the process of schooling and profession that took place in the Court, in the legal, political and pedagogical sphere. But he was also able to follow and participate in other types of changes, those of the subjects, whether they were of the profession, government or schooling. In this sense, as regent, he witnessed and acted in pedagogical changes, in the school bureaucracy and in the public attended; as a colleague, he accompanied the movement of teachers’ appointments - in many of which he had a direct participation in being a member of examination boards - removals, retirements and exonerations; while a subordinate employee of the State, he observed the establishment of laws, norms, policies and forms of management on the part of the government; and as a subject of the city, changes in urban space and in society of Rio de Janeiro. He witnessed, but also interacted and, at the same time, changed with the teaching profession, the school and the city.

It also calls attention his work in other places that exceed the limits of the school, but possibly connected to it, that allowed the exercise of a teaching protagonism and constitute ways of being inserted in the society. In the meantime, the purpose of this work was to analyze a part of Professor Pardal’s trajectory through a scenario that articulates teaching and his performance in different religious, recreational, social and political spaces in the capital of the Brazilian Empire. It was sought to investigate by which places it transited, the relations established during the life, what were the political and social actions in the society of the time that gave prominence to this professor, whose name circulated significantly by the pedagogical press and, mainly, in the news in general.

In order to carry out the study, a set of sources was used, composed of newspapers of the 19th century press, made available by the Newspaper Libraryof the National Library; manuscript documents of the General Archive of the City of Rio de Janeiro (AGCRJ); Reports of the General Inspectorate of Primary and Secondary Education of the Court (IGIPSC); documents from the D. João VI Museum Archive - UFRJ and the Pedro II College Archive (NUDOM).

The research used the methodological resource of tracking the “name string” of Ginzburg and Poni (1991). The tracking work resorted to a diverse and voluminous set of sources that, like a compass, contributed to delineate paths, strategies of research, analysis and writing. By tracking the ‘name string’, it was possible to gather a variety of information about the life of this teacher, analyzed from the concept of game of scales of Revel (1998, p. 20), where the local and the global are intertwined, considering that “[…] varying the objective does not only mean increasing (or decreasing) the size of the object on the screen, it means changing its shape and its pattern”. Revel (1998, p. 28) points out that, in the experience of microanalysis, “[…] each historical actor participates, in a close or distant way, in processes - and therefore, inserts in contexts - of variable dimensions and levels, from the most local to the most global”. Thus, for the author, there is no hiatus or opposition between local history and global history.

The study is organized in two parts. The first deals with the role of Pardal in the classroom; the second analyzes his performance in the city unfolding in the local, political, social, economic, religious and recreational spheres.

The Emergence of a Teacher

In the historiography of education, Candido Matheus de Faria Pardal is commonly cited in the research as one of the signatories of the Manifest of Teachers of the Court of 1871 (Schueler, 2002; Lemos, 2006; Borges, 2008), as director of municipal schools (Gondra & Schueler, 2008) and as an author, along with José Ortiz, of a grammar (Teixeira, 2008; Schueler, 2008). Born in Rio de Janeiro, Pardal was born on January 10, 1818 (Blake, 1899). His filiation was located during the newspaper research. According to information obtained in the list of qualification of the voters of Engenho Novo (Diário do Rio de Janeiro, 1877) was the son of Matheus Henriques de Faria. His mother was identified during the survey of the relatives of the students of the Public School of Santa Rita of 1855. A woman responsible for one of the students was the mother of Pardal. Shewascalled Elisa Vieira da Silva (Gazeta de Notícias, 1881).

Pardal was a drawing student at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, where he won a gold medal in historical painting, a prize that favored his admission as a drawing teacher at the Pedro II Imperial College in 1839. In 1837, two years earlier, Pardal had been approved in public contest for primary teacher of the Public School of Santa Rita, where he remained until 1874 when he retired from office. In 1872, he was appointed director of the municipal schools, maintained by the City Hall, an indication related to its political action by the Conservative Party.

The geographical establishment of Pardal in the neighboring region of Santa Rita and Santana allowed him to build more lasting relations with the locality, a temporary permanence that makes the space a source of tensions and strategies (Borges & Vidal, 2016). The paths of ex-students, parents, guardians and the teacher crossed several times after the children left the school of Santa Rita, because, as dynamic characters, they attended and worked in other spaces. These spaces, although they were no longer that of the school, were also places of learning, as Costa (2012, p. 20) points out, who, working with a broader conception of education, makes an analysis about “[…] educating as lived experience, teaching and learning among the own popular subjects, even outside of school, in workers’ associations, or in a more diffused way in their everyday life”.

In this sense, the practice of reading and writing in their daily lives passes through the experience of learning with Professor Pardal and observing his agencies, with which students may also have learned more than school content. When they lived in a space where their parents, guardians and the teacher, in the exercise of other activities, engaged in relationships outside the school environment, but at the same time in connection with it, could learn political games, resistance strategies, claims, forms of insertion in the city, ways of being and being in the capital of the Empire, many of which are recorded in the various newspaper notes of the 19th century.

How did the teacher’s trajectory enable him to construct an image of ‘illustrious’ in the class? Keeping news from newspapers provides us with insights into the process of building a supposedly successful ‘career’ in teaching. In the series of complimentary news published by the newspapers, one of the Correio Mercantil (1859), is strategically signed by the codename ‘Impartiality’.

We witnessed on the 20th of the current, the closing of the classes of the public school of Santa Rita, directed by Illustrious Mr. Candido Matheus de Faria Pardal; and on this occasion we were surprised to see the advancement and application of his disciples, as they argued over grammar, Christian doctrine, arithmetic, etc., in a prodigious way.

We have long had Mr. Faria Pardal in consideration for his talent and illustration as well as for his fine qualities, but from this day forward this concept was elevated by seeing the friendship, the effort and dedication that he employs with his disciples, in order for them, for the future, place themselves in the highest positions.

Congratulations, then, to the parents of the students for having given the care of the education of their children to such a different person; Congratulations to Mr. Pardalfor seeing that his work has not been fruitless.

Mr. Pardal will excuse me if, with these words, I offended his modesty, but they are daughters of the ‘Impartiality’.

The public exhibition of student exams and the closure of school activities was a practice frequently used by Pardal, both in the public school of Santa Rita and in municipal schools. It was possible to locate several advertisements where Pardal notices or invites interested parties to attend the ‘spectacle’, a strategy that could function as a kind of ‘showcase’ of the school - at a time when exhibitions were in vogue (Vidal, 2006; Barbuy, 2006) -, where the good results of a pedagogical investment made by Pardal, to which it was intended to give visibility, would be exhibited. It was a way of publicizing the advantages of the methods worked and selected by the teacher, as well as the programs, books, and perhaps materials used. The strategy seems to have been fruitful, as newspapers published praise notes about the exhibition. The congratulations of parents and the expectation that students put themselves in “high positions” presented by the newspaper also draw the attention of readers to the school, to which is intended to confer prestige. Coining the idea of ‘exhibition school’, inspired by the ‘exhibition city’ of Heloisa Barbuy, may have many limits in the case of the school of Santa Rita, starting with the fact that it does not work in its own building, but in the same house where the teacher Pardal resided. But the concept can be better explored in the municipal schools of São Sebastião and São José, palaces built specifically for this purpose. These schools received constant visits, had a special book to register them and received a prize in the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876.

Teaching in the city

Studies of Fonseca (2010), about the royal teachers in the captaincy of Minas Gerais, therefore in a period more backward in time, indicate their relations with the administration and with the communities where they were inserted, their activities in teaching and in other social instances, demonstrating that

[...] they were also active subjects in the construction of strategies of social insertion through literacy and that the exercise of this profession was both their means of material survival as the starting point for reaching other positions in society. The royal teaching profession was the mark that distinguished many of them and offers us another way of approaching the lives of these individuals in their relationship with others and with the society in which they lived (Fonseca, 2010, p.18).

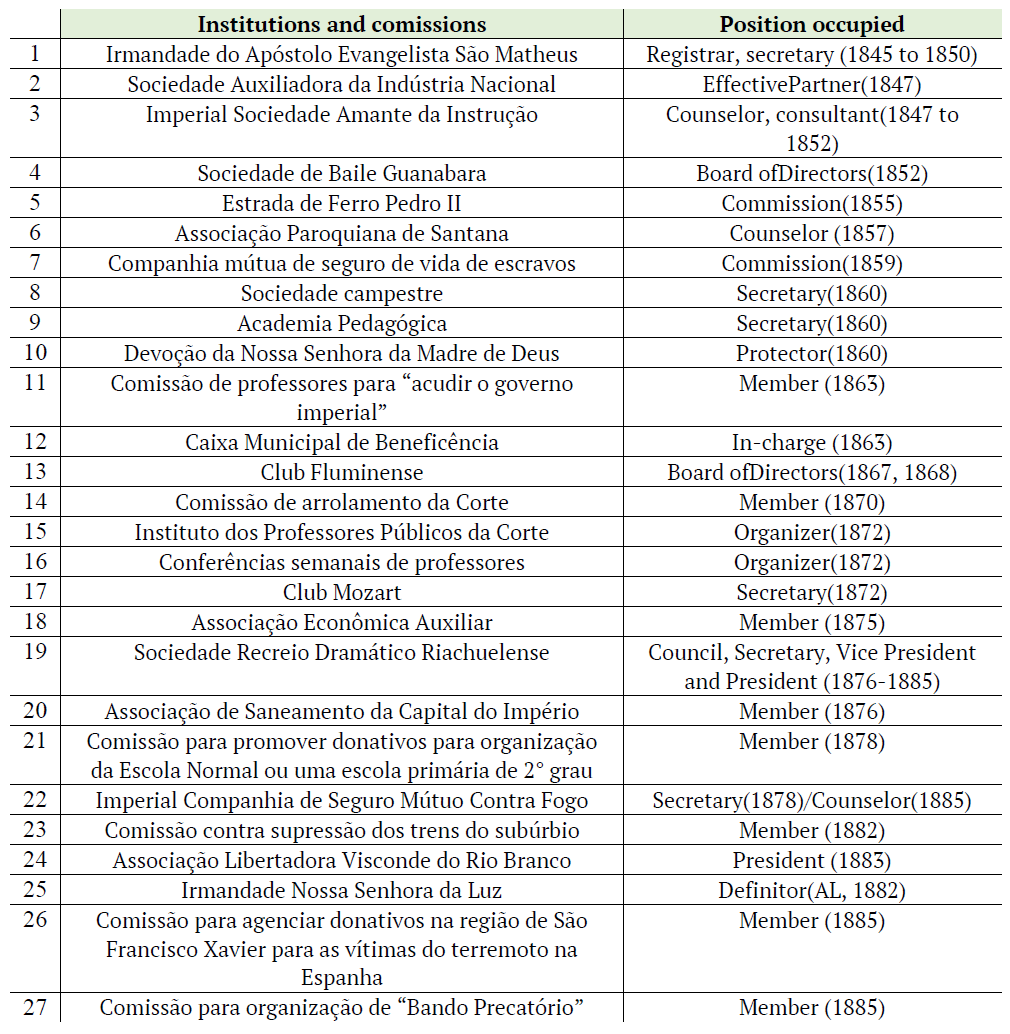

In such a way, from the house to the street, we can observe public and assistant professors participating in various social circles. Agustín Escolano discusses the importance of analyzing the genesis and functioning of teachers’ sociability circles and networks in order to understand “[…] the societal configuration of the teaching profession, an essential aspect to analyze the development of the teaching profession” (2011, p. 23, our translation)9. And he cites the brotherhoods, corporations, associations, conferences, centers of collaboration, spaces of practice and professional press as the places where the teacher sociability was formalized and the art of teaching spread. For Viscardi (2004, p. 100), associations played a key role in civil society by helping to reinforce collective identities or even “[…] function as facilitators of the citizenship building process”. Box 1, about the institutions and activities of which Professor Pardal was part, built from the research, reflects the different dimensions of the activities of the public teacher at the Court in line with the issues under discussion at the time.

The number of institutions and social, economic, cultural and religious activities with which the teacher has been involved is considerably large. It should be noted that only journalism reports were included in the box, as it was not possible to evaluate his participation in other institutions that did not have the privilege of receiving a press release, as well as those in which Pardal did not occupy a management position. This shows that the teacher was a very socially active person. He circulated through various social spheres, from the ‘good society’ of the Club Fluminense (Diário do Rio de Janeiro, 1867), to the commission appointed by residents of the suburb, allowing the constitution of a diversified network of sociability. He operated with the hypothesis that, by participating in these spaces, occupying different positions and garnering support from subjects from different social circles, Pardal invested in a public career - possibly in local politics - and exerted a teaching role in society.

Local action

In 1882, Professor Pardal was the rapporteur for a committee against suppression of suburban trains, which feared seeing a depopulated region and the uninhabited houses that represented ‘the accumulated capital at the expense of immense sacrifices of workers and citizens’. With ‘eloquent words’, the teacher, former owner of a slave, thanked the editor of the newspaper, the abolitionist José do Patrocínio, for his energetic attitude to rule against the suppression of trains. Patrocínio thanked for asserting that the Gazeta da Tarde was the ‘newspaper of the people’ and that it did no more than its duty (Gazeta da Tarde, 1882).

Popular initiatives to claim improvements for the regions where they lived or interceded on behalf of certain subjects seemed to be quite common and could often be seen in the press. Teachers, as part of the population, were not oblivious to the mobilizations. In some cases, the involvement of the school and the teacher with the mobilizations seemed to be significant and fairly close, using the school space itself. The case of the meeting for the organization of the Associação de Saneamento da Capital do Império illustrates the situation (O Globo, 1876). The event took place on October 15, 1876, at the São José municipal school and was attended by countless people, including some teachers such as Pardal (director of the school) and Carlos Augusto Soares Brazil. This episode and its unfolding also signal the relations between a local institution and issues of the wider space of the city that mobilize different subjects and their networks.

The association emerged from a hygienist point of view. Its organizers, faced with the conditions of the city at that time, called for an urgent reaction from the population, claiming that it was impossible to “[…] remain indifferent for a long time to the disgusting spectacle that progressively presents the capital of the Empire under sanitary conditions every year” (O Globo, 1876). The opening speech of the session, given by the doctor Franklin do Amaral, referred to the data produced by a device that also had the participation of teachers: the population recensus. This was not a population initiative but was related to it. The procedure also made use of the school space, as in the case of the enrollment commission responsible for recensing the second district of Santana of which Pardal was president. Its first meeting took place in Largo da Imperatriz, 125, address of the school of Santa Rita (Diário do Rio de Janeiro, 1870).

The appointment of public teachers among those invited to work in the census fits well in the perspective raised by Mattos (1994), of teachers as strategic parts in the public administration and construction of the State; and also in an analysis by Carvalho (2007) that the circulation by different positions of the public administration conferred political experience to the subjects. Although they are of different proportions, the activities of teachers in local activities gave them a local experience and publicity of their image that could be used in political situations. The proximity of the teacher to the population made him a potential agent to carry out this type of task, due to the knowledge of the inhabitants of the locality, besides possessing privileged information for being responsible for the school document that contain data useful to the census: the enrollment map of the school, which, among other things, records the names of the students, parents or guardians and their addresses.

The population was also mobilized when Professor Pardal was summoned to assist in another civic and festive activity: the organization of the festivities adopted by the city council to celebrate the “[…] decisive victory of the allied armies in the Republic of Paraguay” (Câmara Municipal, 1868, p. 1). The city council urged residents to light their homes for three days and appointed committees to make efforts to assemble triumphal arches, artifacts, and lighting in public places during holidays. It should be noted that Candido Matheus de FariaPardal Junior, son of the teacher, also fought in the war and was in list of injured in the battle of Curupaity (O Publicador, 1866).

Another activity related to local life concerns the structure of the police apparatus. Each province would have a police chief. In Rio de Janeiro, he was appointed by the emperor and was reported to the Minister of Justice, indicating the delegates and subdelegates, to be appointed also by the emperor, and the latter indicated the block inspectors to be submitted to the approval of the police chief.

The subdelegates were distributed to the districts and could appoint ‘justice officers’ to assist them or to please friends with a position that was unpaid but dispensed from the national guard service. The smallest administrative division was the block, of which a resident was named a ‘block inspector’, also unpaid and subordinate to the subdelegates, whose role was “[…] to be alert to suspicious, malevolent or illegal activities in their local jurisdiction, to make arrests in flagrante and to respond to requests for help from other authorities” (Holloway, 1997, p. 161).

During the research, the participation of both teachers and parents of students in these functions was found. Francisco Xavier da Silva Moura, father of a student enrolled in 1855 at Santa Rita public school, who had already been a block inspector in 1850, was an alternate of the subdelegate of the same parish (1874), as well as Professor Pardal, alternate of the subdelegate of the second district of Santana (Diário do Rio de Janeiro, 1861). The following year, Pardal assumed the status of subdelegate and published a note on the day and time of attendance of the post, and the place, his residence in Rua da Imperatriz, 125, that is, the same address of the school where he taught (Correio Mercantil, 1862).

To the singular condition of Professor Pardal at that moment is attributed great symbolic power. The combination of school, substation of police and residence brings the bonds existing in the agreement between the subjects who educate and those who must be educated, those who watch and those who must be watched, those who punish and those who should be punished. It should be remembered that the subjects of the public education apparatus could resort to those of the police apparatus to supervise and oblige parents and guardians to send their children to school. With the coexistence of the apparatuses in the same space, Professor Pardal embodied, without leaving home, the functions of teaching, guarding and punishing, constituting in such a way an exquisite triad of actions that went perfectly to meet the schemes of governability engendered by the Imperial State.

Political action

The Constitution of 1824 established the minimum age of 25 years (21 for married men, military men, clerics and bachelors) and instituted the minimum annual income criterion of 100 thousand réis per year to be a voter10 and 200 thousand to be an elector. From the reform of 1846, the calculation was changed to silver, which was equivalent to double those values. There was no requirement for literacy, but it was necessary to carry out the qualification of the voters that was given before the day of the elections, through a meeting formed in each parish, presided over by the justice of the peace.

[...] in the primary election, where poor voters participated, qualification boards have always represented the way in which owners and electoral political leaders manipulated local power, so that the customs of electoral violence and arbitrary recruitment had roots in colonial society, and would persist until the crisis of slavery imposed the need for new resources to attract the free laborer (Dias, 1998, p. 71).

Some subjects investigated in this study composed the boards, actively participating in the qualification of the voters, that is, evaluating the right to vote of those who could be considered citizens. In the same set of people connected to the school, therefore, there were those who could be voters, those who evaluated who could vote, those who did not vote and those who could be voters, whose children and guardians shared the same primary school classroom.

In 1881, Dias (1998) recalls that the Saraiva law extinguished the primary elections of poor voters and prohibited the illiterate vote. Carvalho (2007) points out that the participation rate in the elections fell drastically, only being recovered in 1945. But until 1881, when there were a series of changes, many parents and guardians of the year 1855 were involved in the electoral process in the Court, as well as Professor Pardal who was a voter, was on the voting slatesfor the voters, voted in the second-degree elections, participated in the qualifying tables and was involved in an episode of violence in the dispute between parties during the elections in 1868. By adjusting the lens of the investigation, it becomes possible to understand the dynamics of electoral processes from different scales of observation, showing both the dynamics of local events and those of greater magnitude, involving ‘poor voters’, local authorities, politicians of different echelons, and rulers. This procedure allows to visualize the political action of Professor Pardal through games of scales, according to Revel’s concept (1998), focusing his transit through diverse spaces and political roles.

The first newspaper note located during the search with the name of Pardalin the electoral process dates from 24/12/1850 (Correio Mercantil) in which he already appears on the voters lists, as an alternate. In the years that followed, the professor now appeared as a voter, now as an alternate, or as a member of the polling stations (scrutineer and board member). Some notes refer to him as voter by the Conservative Party - a link that gave him the position of director of municipal schools - but in his first appearances on electoral matters, such as that of 1856, Pardal was on the list of Zacharias de Góesand Vasconcellos, a liberal politician, which demonstrates the complex party game of the time. The result of the vote elected Pardal, along with Zacharias, Francisco Joaquim de Nazareth, Visconde de Itaboraí (who had been inspector of the Court’s instruction until the year before, 1855, when he assumed the post Eusébio de Queiroz), and Porfirio José da Rocha, doctor and justice of the peace. The mix can be understood as part of the conciliation policy begun in 1853, including the Liberal and Conservative parties. Pardal appeared again in the slate of Zacharias in 1860 in a list published, supposedly like provocation, by the newspaper Correio Mercantil, and titled Chapa Policial de Santana (1860), perhaps by the number of people who occupied positions of the apparatus of repression of the state.

According to Graham (1995, p. 359, our translation)11, the elections mobilized the interest of the majority of the male population and the result “[…] was that elections could be popular events where local leaders reaffirmed their pre-eminence before a broad audience”. Graham also notes that although candidates for deputies received votes only from voters, they did so through letters addressed to them and also to “[…] notable members of the people, each local boss demonstrated his importance by inducing voters, his clients, to participate in tumultuous manifestations” (Graham, 1995, p. 359, our translation)12. The result, Graham says, could end in widespread joy or armed confrontation.

Pardal and Marcos Bernardino da Costa Passos (who was not yet a public teacher at the time) are the oldest teachers found as voters, both as substitutes, in 1850. It can be observed that the voter professors identified were from different parishes, between urban and rural, and by acting in electoral processes helped to shape the political scenario of the time.

In the set of teachers who worked at the Court, there were those attached to the Progressive Party, the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party, which demonstrates that there was not only a political position within the category and that this did not prevent teachers from different political groups from acting together in favor of the class. Despite the rivalries within the primary public teaching, as evidenced by the pedagogical press (Villela, 2002), there was an attempt to get an image of unity.

The parish of Santana had over three decades always a primary teacher as a voter, contributing to the political configuration of the governing bodies and local disputes. Although Sparrow and Cony were linked to opposing parties, political rivalry did not translate into personal disagreements. Cony and Sparrow, for example, have adopted similar pedagogical experiences, such as the appropriation of the Rapet13system, and notes in the press record Cony’s praise for Pardal’s work.

In the 1880s, when he lived in Engenho Novo, Pardal appeared on a list published in the newspaper as a city councilor (O Paiz, 1885). The note reported that the councilmen had delivered to the treasury of the city hall the ‘collected’ amount in Engenho Novo. This was the only mention found at the post of city councilor occupied by Pardal during the survey, it was not possible to obtain more information about the fact or to verify if the note had been in error to include the name Pardal. The list of councilmen published by Almanak Laemmert in this period does not bear the name Pardal, for example. However, the possibility of electing a retired professor to a higher position in electoral processes could suggest the conquest/construction of a public importance and image throughout his career in Rio de Janeiro.

Another position that was related to the elections was that of justice of the peace that was elected in the elections of second degree, along with the councilmen. The reform of the Code of Criminal Procedure in 1841 limited its powers, but according to Flory (1986) his figure continued to represent a local authority of social control. The subsections of article 91 of the Code that refer to the role of the justice of the peace were:

§ 4º To put into custody the drunk, during the drunkenness.

§ 5º To avoid the quarrels, trying to reconcile the parts; to make sure that there are no vagrants or beggars, obliging them to live honest work, and correcting alcoholics, turbulent, and scandalous whores, who disturb public tranquility, forcing them to assign a term of well-being, subject to penalty; and watching over their subsequent procedure.

§ 6º To destroy quilombos, and to ensure that they do not form.

§ 7º To make record of body of crime in cases [...].

§ 9º To have a list of the criminals to arrest them, when they are in your district [...].

§ 14º To search for the composition of all disputes, and doubts, that arise among residents of your district, about private roads, crossings, and passages of rivers or streams; about the use of water used in agriculture or mining; of pastures, fisheries, and hunts; the boundaries, the fencing, and the enclosures of the farms and fields; and finally about the damage done by slaves, family members, or domestic animals.

Pardal held the position in Engenho Novo when he had already retired. At least seven teachers have also performed or applied for the position. According to Rodycz (2003, p. 12), “[…] it represented a step towards achieving social and financial ambitions […]”, a way to broaden their circle of influence and “[…] gain advantages over their neighbors, who were paired with the many favors they could give them as a judge”. The presence of primary teachers in the function of justice of the peace was also identified by Moraes (2015) in the village of Cotia, in the province of São Paulo, and by Munhoz (2012) in the fifth district of São Paulo, which included the villages of Curitiba and Paranaguá (regions belonging to the current State of Paraná), including the positions of jury and councilor, serving as an example to demonstrate that the teaching involvement in such activities also occurred in other regions of the country.

Flory (1986, p. 109, our translation)14 emphasizes the local and informal importance of the justice of the peace. In his parish “[…] he was a flesh-and-blood personality whose powers were defined in equal measure by individual and community pressures rather than by statutes and decrees”. A primary public-school teacher, while serving as a justice of the peace, could combine different but related functions: educate and help maintain order, thus embodying two ‘missions’. A single individual was at least at the same time an elector, a justice of the peace, and a public teacher. According to Flory, “[…] since he was such a basic figure and a product of his environment, to describe the imperial justice of the peace is, in large part, to describe the political and social life of the Brazilian parish community” (p. 109, our translation)15. Thus, in the case of the parishes where there was the most intense activity of primary public teachers occupying positions such as this one, one can think that to describe the justice of the peace can be to describe the political and social life, but also the school life of that space.

The interest of the primary public-school teachers to occupy the position of justice of the peace also calls attention, as well as the fact of teaching and the performing the judiciary in the same place, the public-school building. It was a sign that school, rather than a space for teaching to read and write, could represent a political place, concentrating instruction policy and local problem-solving policy. Thus, the presence of a school in the locality could generate more effects than expected by primary schooling, depending on the teacher’s involvement with social agencies. Electoral, ordering, punitive, conciliatory effects. In this sense, the importance of the role of the school in the parish could extrapolate the intentions desired with the schooling process, since it could be intensely involved with other political and social processes.

Being summoned to compose the jury of the Court also had relation with the elections, since its members were designated from the question of probity and the criterion of eligibility in the elections of second degree. Pardal was several times selected for the jury in sessions where the public prosecutor (who participated in jury qualification) was his former student Antonio Ferreira Vianna, inspector of the municipal schools in 1872.

In Rio de Janeiro, the law prescribed six jury sessions throughout the year. The trial process had several stages. In one of them, the judge read a summary of the testimony and asked questions to the jury about the existence of the offense, guilt, degree of guilt and compensation. If the jurors declared the defendant as guilty, the judge of the law dictated the sentence “[…] this being virtually his only direct role in the whole process” (Flory, 1986, p. 187, our translation)16.

The first appearance of Pardal as a member of the jury, in the material researched, occurs in Correio da Tarde (1860), in a list that also included Justiniano José da Rocha in the body of jurors. The last one, in the newspaper Brazil - Órgão do Partido Conservador of 3/12/1884. In such notes, there was no description of the cases to be judged. But in the session dealt with in the Correio Mercantil (1861), in which Pardal was listed as a juror and the prosecutor was also Antonio Ferreira Vianna, the cases presented were of murder, theft, stellation and resistance. Crimes of various categories, about which the Professor Pardal would issue one more type of opinion, among several that his office gave him.

According to Flory (1986), both the jury and the justice of the peace consisted of innovative institutions in Imperial Brazil. Popular jurisdictional bodies that, according to Rodycz (2003, p. 4), constituted the decentralization and democratization of justice “[…] considered anachronistic and distanced from the people […]”, despite the failure, especially of the figure of the justice of the peace, caused by the pressure of the oligarchic forces. In this sense, in spite of the disciplinary character, it is necessary to emphasize the force of the representation that meant the existence of primary teachers exercising such functions of “[…] popular participation in the administration of Justice” (Rodycz, 2003, p. 29).

Acting in associations, companies and brotherhoods

In the 19thcentury, it is possible to observe a considerable number of institutions with diverse purposes linked to beneficence, religion, literary field, education, diffusion of science, security, montepios, mutual aid, insurers, among other areas, according to a study by Pereira de Jesus (2013). Although some have a well-defined performance, it is worth noting the difficulty of classifying the field of action of some other institutions by extrapolating or overlapping different fronts of action, although the nomenclature indicates a certain purpose as a major flag. In this sense, the alert must be considered in the different institutions gathered in this same part of the analysis.

The significant presence of teachers in such institutions should not be overlooked, reiterating Escolano’s warning (2011), both because such spaces formalize teacher sociability and because they help to spread the art of teaching.

In 1847, Pardal appeared on the list of guests to become effective members of the Sociedade Auxiliadora da Indústria Nacional (O Auxiliador da Indústria Nacional, 1847a), whose acceptance was recorded in the in the society’s journal the following month (O Auxiliador da Indústria Nacional, 1847b). He was appointed by the perpetual secretary of society, Emilio Joaquim da Silva Maia, who, like Pardal, was also a professor of natural history, geology and physical sciences at the Pedro II Imperial College. The indication to the society, therefore, came from a network of sociability ofPardal in a school space where he worked and allowed him to build other networks of relations.

Inspired by the Société d’encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale, the Sociedade Auxiliadora da Indústria Nacional (SAIN), according to Carvalho (2007) was created in 1827 and did not refer to industry in the current sense, but to the productive activity in general that was agricultural at the time. Carvalho points out that SAIN was closer to a study center or literary society, with “[…] more symbolic and honorable than instrumental […]” participation of politicians (2007, p. 52). It served as a “[…]forum in which the more progressive elements defended their views […]”, such as the replacement of slave labor, a clamor that did not achieve much success. However, elements of government used the studies of society to defend certain reforms.

SAIN had a periodical, O Auxiliador da Indústria Nacional, published after 1833: “[…] an activity of diffusion of scientific and technological knowledge produced within a specific community, the Sociedade Auxiliadora da Indústria Nacional” (Barreto, 2009, p. 270). It should be noted that SAIN also participated in the founding of other societies such as the Sociedade de Colonização in 1835, the Instituto Históricoe GeográficoBrasileiro in 1838 and the Instituto Fluminense de Agricultura in 1860 (Gondra & Schueler, 2008).

All members who were duly qualified could attend any session, propose memoirs and writings that would contribute to the improvement of the industry or the progress of society, as well as use the library, examine the machines, consult the records, minutes and records of the Board (Barreto, 2009). Such spaces inside the SAIN could favor the contact of its members with the foreign innovations and theories, propitiating the international circulation of ideas.

Pedagogical initiatives were also part of SAIN. In 1848, there was a reform of the statutes, one year after Pardal’s entry as an effective member, which may have allowed him to participate in the discussions that purported to change the document. Barreto points out that the new statutes established “[…] the institutionality of the association as a space of educational character” (2009, p. 224). Thus, the society aimed to make available to the public machines, specialized library, collection of natural products, a periodical and classes to develop the industrial doctrines.

Teachers also resorted to mutual aid, security, savings and insurance institutions, among others, as a means of ensuring some assistance in difficult situations in private life. There were those founded and directed to the teaching class, but several teachers were also members of other institutions that were not

corporate. Pardal was a member of the Associação Econômica Auxiliar, in charge of the Caixa Municipal de Beneficência, and also served on the board of directors, as secretary and councilor, of the ‘Imperial Companhia de Seguro Mútuo Contra Fogo’. Founded in 1854, the company had, under the 1877 statute, the “[…] principal and sole purpose of mutually guaranteeing to its members any risks and damages arising from fires caused to the properties which are safe there” (Brasil, 1877a). According to Saes and Gambi (2009, p. 2), “[…] the expansion of this activity was closely associated with the growing needs imposed on a changing society”.

Mutual insurance companies were societies “[…] in which all partners had as owners the same type of insured object: vessels, slaves, buildings or other commodities” (Saes & Gambi, 2009, p. 15). Thus, another insurance company of which Pardal was a member, CompanhiaMútua de Seguro de Vida de Escravos, calls attention. According to Saes and Gambi (2009), the insurance of slaves transported by ships was not allowed by the Brazilian Commercial Code because of the prohibition of slave trade, but as the slave had high value on farms and urban properties “[…] their insurance became a peculiarity of the national market, while slavery had already been abolished almost everywhere in the world” (Saes & Gambi, 2009, p. 16).

Other institutions that were part of the daily life of the city and the life of the teachers were the brotherhoods, devotions, confraternities, third-orders among other organizations of a religious nature. They were generally intended to encourage devotion to a saint and to promote charitable actions. Brotherhoods, organized by laymen, and third-orders subordinated to religious orders, with greater power and money, had hospitals and activities aimed at serving the poor. They could favor the gathering of subjects from different social groups, establish ‘vertical solidarities’ and also serve as associations of class, profession, nationality and ethnicity (Abreu, 1999).

Pardal held positions in the administration of three brotherhoods/devotions: he was registrar and secretary of the Irmandade do Apóstolo Evangelista São Matheus; protector of the Devoção da Nossa Senhora da Madre de Deus; and Definer of the IrmandadeNossa Senhora da Luz. In the cases of the Irmandade de São Matheus and theDevoção, the performance of Pardal was marked by the authorship and publication of notes with different purposes in the newspapers.

As protector of the Devoção in 1860 Pardal summoned the devotees to send their alms to the address largo da Imperatriz, n. 121 (Correio Mercantil, 1860). The ad puts ‘pharmacy’ in parentheses, to highlight, because as already mentioned, this address was the same as the public school of Santa Rita.

The process of forming a group of ‘devotion’ had a simple trajectory, according to Cavalcanti (2004). It was enough to achieve a certain level of organization, to register rights and duties in a ‘compromise’, a kind of statute that defined discipline rules without the need for official formalization: “They could be structured around a street oratory, private house, a church with the permission of the proprietary Brotherhood or its parish priest” (Cavalcanti, 2004, p. 206). The simple organization allows us to understand the combined place for the delivery of alms from devotees, the pharmacy. Convenient place for the ‘protector’ Pardal, because it was close to the teacher and would not disturb the progress of classes in school.

As a registrar and secretary of the Irmandade de São Matheus, Pardal announced in the newspapers of great circulation, Diário do Rio de Janeiro and OMercantil, the feasts in honor of the apostle, between 1845 and 1850. According to Abreu (1999), the feasts were the maximum moment of the brotherhoods, whether large or small, and allow to understand “[…] the exercise of popular religiosity and its dynamic, creative and political relationship with the different segments of society” (Abreu, 1999, p. 37).

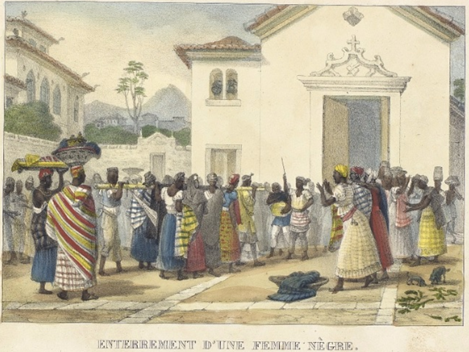

In the announcements, it was reported that São Matheus was ‘erect’ or ‘is venerated’ in the Church Nossa Senhora de Lampadosa, where the feast was held. This church, located in the parish of Sacramento, appears in historiography as a space frequented by blacks. Lopes (2006) points out that the church, in the first half of the 19th century, belonged to a mulatto brotherhood, served by black clergy and housed a ‘cemetery of wealthy Africans’.

A watercolor lithograph by Jean-Baptiste Debret, called ‘Funeral of a Black Woman’, has as its background the church (Leenhardt, 2006). The scene, according to Leenhardt, portrays a space with strong symbolic connotation and is treated as a document in the study of the rituals of life of the African population in Brazil. Through the image, he points out, for example, that African women are familiar with Catholic religious experience because they are forced to follow their mistresses with the rituals of religion. This analysis is made in contrast to the lithograph ‘Funeral procession for the son of a black king’, also of Debret, in which the scene does not denote the same perspective of order of “Funeral of a Black Woman” (Leenhardt, 2006).

Source: Debret (1839, plank 16).

Figure 1: ‘Funeral of a Black Woman’ of Jean-Batiste Debret. In the background, the Church Nossa Senhora de Lampadosa.

Among the churchgoers is Machado de Assis who lived in Morro do Livramento, near the public school of Santa Rita. Facioli (2008) states that Machado de Assis’s stepmother, after his father’s death in 1851, started to make and sell sweets as a means of support. To help, Machado became an auxiliary of the sacristan of the Church Nossa Senhora de Lampadosa, which Facioli points out to be one of the most important brotherhoods of slaves, freedmen and free blacks.

The characteristics of Brazilian society in the 19th century make the analysis of relationships in the period quite complex, such as the way that Pardal dealt with the issue of slavery and abolitionism over time. He was a board member of an upright brotherhood in a black church, at a time when he owned a slave. It was at this time, more precisely at the end of the year 1848, that his slave, João Congo, attacked his life, and was imprisoned for it (Correio Mercantil, 1848). He was a member of the commission of the Companhia Mútua de Seguro de Vida de Escravos and later of an abolitionist society, of which he was elected president, in 1883. On the day of his inauguration, he delivered a speech in which he proposed to change the name of the ‘Associação Libertadora Visconde do Rio Branco’ to ‘Sociedade Abolicionista Visconde do Rio Branco’ “[…] so that one could have the purpose of abolitionist ideas” (Gazeta da Tarde, 1883). The meaning of this proposed change in terminology and its adoption suggests changes in the level of discussions about the topic and the demand for an increase in the entity’s performance.

Such facts occurred in distinct phases of the teacher’s life. The incident with João Congo occurred when Pardal was 30 years old and participation in the abolitionist society occurred at the age of 65. According to Barros (2017), it was not uncommon for a teacher to have slaves. In a study about the presence of blacks in the literate universe in the Paraíba do Norte Province, the author addresses the case of Professor Manuel Cardoso Vieira (1848-1880), black, belonging to the Paraiba elite and owner of several slaves who, two years before dying, he joined the political group of abolitionists. The different positions that Pardal and the professors occupied in relation to the enslaved population indicate the complexity of 19thcentury Brazilian society and the need for both researches that verticalize in synchrony and studies that address diachrony, thus allowing the understanding of a heterogeneous process of constitution of ways of thinking and acting.

Acting in recreational activities

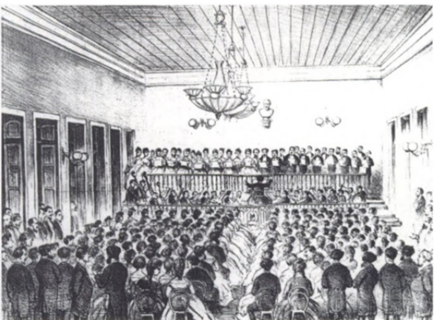

Pardal was a member of several recreational and musical societies, such as the Sociedade de Baile Guanabara, Sociedade Campestre, Club Fluminense, Club Mozart and SociedadeRecreioDramáticoRiachuelense. According to Silva (2007), several concert promoters were created in the second half of the 19th century, such as the Club Mozart, which played an important role in the music scenario of Rio de Janeiro. Based on Cristina Magaldi’s research, Silva points out that

[...] the music clubs are also part of the process of urban modernization of the city that had between its main influences England and France. The music clubs also provided a cosmopolitan air for the musical life in the court becoming important agents in the promotion of concerts in the city (Silva, 2007, p.22).

Pardal was secretary at Club Mozart (Correio do Brazil, 1872), a recreational institution founded in 1867, focused on the development of vocal and instrumental music. Magaldi (2004) points out that the club was a space frequented by the elite and that the statutes established that its members should demonstrate good conduct and “[…] a decent position in society” (Magaldi, 2004, p. 70). In charge of treasurer of the institution, the AlmanakLaemmert of 1884 registers another primary teacher, Gustavo José Alberto, from Bahia and black, according to Schueler (2007). In this sense, it should also be noted that according to Silva (2007, p. 24), Machado de Assis was a librarian of the Club Beethoven, representing the insertion of a portion of the population in institutions understood as elitist: “[…] despite the segregation, these recreational institutions made possible a coexistence of different socially people, but that were linked around a kind of fun”.

Source: Magaldi (2004, p. 71)..

Figure 2: Gala concert at Club Mozart, extracted from the newspaper A Vida Fluminense.

The Mozart Club also had its contribution share in the organization of the category, because its space would be used for teachers’ meeting in 1884 (Gazeta da Tarde, 1884). The convocation was followed by a large list of teachers, including four women. Gustavo, the Club treasurer mentioned in this period, is not on the list, but may have facilitated the authorization to hold the event in a place whose members should have good conduct and decent social position. This fact denotes the transit, the agency and the exchange between the spaces, subjects and activities that, at the beginning, were not correlated, but ended up being connected by the networks of sociability of the subjects that put them in operation.

Pardal was also secretary of the Sociedade Campestre and, in the same period, also counted with a teaching colleague as part of the management team, the teacher of the public school of Candelária, Luiz Thomaz de Oliveira, as procurator (Correio Mercantil, 1860). The partnership with colleagues also took place in another institution, the Sociedade Particular Recreio Dramático Riachuelense. According to the statute of 1877 (Brasil, 1877b), it had “[…] to promote among its associates the recreation and instruction through representations of dramas, tragedies, comedies, etc.”. The society owned a land registered in its own statute.

Art. 7º The Society’s assets are: twenty-two meters of land to Street D. Anna Nery at Riachuelo Station and the theater being built on the same plot, all worth twenty thousand réis, represented by two hundred shares of one hundred thousand réis each.

Coincidentally or not, the land was on the same street where Pardal was resident in the parish of Engenho Novo, probably in 1874, the year in which he was exonerated from the post of subdelegate for reasons of change (Diário do Rio de Janeiro, 1874). The geographical proximity between residence and society facilitated the presence of the professor in the various positions he held in the society’s board of directors. The professor’s wife, ElysaPardal, participated in several plays atRiachuelense and received several accolades in the newspapers for her considered talent (Gazeta da Noite, 1880a, 1880b; Gazetinha, 1881; A Folha Nova, 1884; Brazil - Órgão do Partido Conservador, 1884).

Under the 1877 statute, the society management consisted of a board of seven members and a council of ten members, all shareholders. The director board consisted of the president, vice president, scene director, first secretary, second secretary, treasurer and prosecutor. Professor Pardal held various positions. He served on the board, was secretary, vice president and president. In the same period that he was vice-president, Professor Augusto Candido Xavier Cony - who at that time also became an elector in the parish of Santana by the Liberal Party -, assumed the commission of accounts of the entity (O Cruzeiro, 1878).

Society is also an example of the fact that political issues often arise in leisure spaces. While Cony, linked to the Liberal Party, was active in the theatrical sector of society, the same space was the site of the meeting of voters of Engenho Novo in 1882, a group of which Pardal was a part (Almanak Laemmert, 1882). Also, in the theater, took office the board of the mentioned Associação Libertadora Visconde do Rio Branco, of which Pardal became president. Just as in the case of Club Mozart, the place was used for meetings for purposes other than recreational purposes.

Such aspects should not be seen as mere coincidence. We do not have more information that indicates the process that led to the installation of meetings of teachers in spaces belonging to a distinct activity institution such as recreational and literary. Nevertheless, subjects who travel through such places should be considered in the processes of agency and of social, political and professional articulation that demand the mobilization of their networks of sociability, diverse subjects, spaces and institutions.

Silva (2007, p. 10) affirms that “[…] the development of these clubs occurs in parallel to the decline of meetings within the home, since it creates an environment specific to discussion, listening, games and reading”. We can also observe that they also emerged as spaces where teachers sought a moment for recreation and, at the same time, could function as an important place for the development of diverse sociabilities. In this sense, music, theater, literature and other recreational activities could be spaces for leisure as well as for making politics, social movements and professional meetings, apparently alien to the space of fun, but with several connections in view of the networks of sociabilities constituted. As Escolano (2011) points out, the history of the teaching profession is also the way in which the actors of education sought to legitimize their social and cultural protagonism from their own practice, which goes beyond the walls of the classroom.

Final Considerations

The collection of notes, articles, satires, advertisements and other types of texts that make up the printed journal genre provided a considerable body of information about the circulation of a subject who acted in school, from school and on school. The displacements that Pardal carried out, especially from functions, from teacher to justice of the peace, to subdelegate of police, elector and president of a recreational institution and an abolitionist society, shows by what spaces and social circles they have transited during their trajectory.

In this sense, Carvalho’s idea (2007) contributes to the fact that politicians circulated around the country in different positions to gain political experience and develop a less provincial perspective. In adjusting the scale to a microhistorical approach, Pardal could be, from a local perspective, a teacher who was not limited to the school space and circulated through different positions and social coexistences that, intentionally or not, provided the formation of networks of sociability, as well as the acquisition of a political experience and acumen that allowed him to gain notoriety and possibly votes.

Although the present study focused on the performance of a teacher, the research made it possible to observe a significant number of primary public teachers in different spheres of action, both locally and in larger issues, demanding to adjust the observation lenses from the concept of scale games, in the collection and analysis of data.

In a very heterogeneous way, the sources investigated point to teachers engaged in undersigned for both solving local problems, as of greater geographic reach, and, for example, in favor of the election of politicians; in the organization of varied local commissions, as well as in commissions of larger institutions such as the Sociedade Auxiliadora da Indústria Nacional. Having teachers in their staffs could give institutions greater legitimacy, assist their organization and fulfill their goals, as suggested by the speech of some entities recorded in newspaper notes. Government and sectors of the population recognized in the teacher an important figure in social processes, and could help both the government in the task of administering society and in the administration of associations of popular or elitist initiative.

The inclusion and performance of teachers as partners, counselors and administrators point to a teaching role in the city, exercised in different levels of activity, institutions and intensity, as observed by Escolano (2011). They were actively involved with order, politics, economy, beneficence, religiosity, and leisure in the city. Despite low salaries, primary teachers used varied strategies and fled from the representation of a passive, modest teacher who would have only dedication to teaching.

REFERENCES

Abreu, M. (1999). O império do divino: festas religiosas e cultura popular no Rio de Janeiro (1830-1900). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Nova Fronteira. [ Links ]

Almanak Laemmert. (1882). [ Links ]

Almanak Laemmert. (1884). [ Links ]

O Auxiliador da Indústria Nacional. (1847a, 15 de setembro). [ Links ]

O Auxiliador da Indústria Nacional. (1847b, 27 de outubro). [ Links ]

Barbuy, H. (2006). A cidade-exposição: comércio e cosmopolitismo em São Paulo, 1860-1914. São Paulo, SP: Edusp. [ Links ]

Barreto, P. R. C. (2009). Sociedade auxiliadora da indústria nacional: o templo carioca de Palas Atena (Tese de Doutorado em História das Ciências, Técnicas e Epistemologia). Instituto de Química, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Barros, S. A. P. (2017). Universo letrado, educação e população negra na Parayba do Norte (século XIX) (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Blake, S. (1899). Dicionário bibliographico brazileiro. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Typographia Nacional. [ Links ]

Borges, A. (2008). Ordem no ensino: a inspeção de professores primários na Capital do Império Brasileiro (1854-1865) (Dissertação de Mestrado em educação). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da UERJ, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Borges, A. (2014). A urdidura do magistério primário na Corte Imperial: um professor na trama de relações e agências (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo . [ Links ]

Borges, A., & Vidal, D. G. (2016). Racionalização da oferta e estratégias de distinção social: relações entre escola, distribuição espacial e família no Oitocentos (Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 16 [2 (41)], 175-201. [ Links ]

Brasil. (1877a). Decreto nº 6.756, de 24 de novembro de 1877. Approva, com alterações, a reforma dos estatutos da Imperial Companhia de seguro mutuo contra fogo. Lex: Coleção de Leis do Império do Brasil, 2, 920-933. [ Links ]

Brasil. (1877b). Decreto n. 6.519, de 13 de março de 1877. Approva os estatutos da Sociedade particular Recreio Dramatico Riachuelense. Lex: Coleção de Leis do Império do Brasil , 1, 179-184. [ Links ]

Brazil - Órgão do Partido Conservador. (1884a, 8 de agosto). [ Links ]

Brazil - Órgão do Partido Conservador. (1884b, 3 de dezembro). [ Links ]

Câmara Municipal. (1868). Programa dos festejos adotados pela Ilustríssima Câmara Municipal da Corte por terem lugar a chegada da faustosa notícia da vitória decisiva do exército dos aliados na República do Paraguai. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Tipografia Perseverança. [ Links ]

Carvalho, J. M. (2007). A construção da ordem: a elite política imperial: Teatro das sombras: a política imperial (3a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira. [ Links ]

Cavalcanti, N. (2004). O Rio de Janeiro setencentista: a vida e a construção da cidade da invasão francesa até a chegada da Corte. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Jorge Zahar. [ Links ]

Correio do Brazil. (1872, 28 de dezembro). [ Links ]

Correio da Tarde. (1860, 25 de fevereiro). [ Links ]

Correio Mercantil. (1848, 31 de dezembro). [ Links ]

Correio Mercantil . (1850, 24 de dezembro). [ Links ]

Correio Mercantil . (1860, 15 de abril). [ Links ]

Correio Mercantil . (1860, 4 de outubro). [ Links ]

Correio Mercantil . (1860, 22 de dezembro). [ Links ]

Correio Mercantil . (1861, 8 de agosto). [ Links ]

Correio Mercantil . (1862, 16 de setembro). [ Links ]

Correio Mercantil . (1859, 23 de dezembro). [ Links ]

Costa, A. L. J. da. (2012). O educar-se das classes populares oitocentistas no Rio de Janeiro entre a escolarização e a experiência (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo . [ Links ]

O Cruzeiro. (1878, 13 de junho). [ Links ]

Debret, J.-B. (1839). Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil (Tome troisième). Pa, FR: Firmin Didot Frères. Recuperado de: http://objdigital.bn.br/acervo_digital/div_iconografia/icon393054/icon393054.htm [ Links ]

Diário do Rio de Janeiro. (1861, 24 de setembro). [ Links ]

Diário do Rio de Janeiro . (1867, 23 de janeiro). [ Links ]

Diário do Rio de Janeiro . (1870, 10 de abril). [ Links ]

Diário do Rio de Janeiro . (1874, 5 de setembro). [ Links ]

Diário do Rio de Janeiro . (1877, 22 de janeiro). [ Links ]

Dias, M. O. L. da S. (1988). Sociabilidades sem história: votantes pobres no império, 1824-1881. In M. Freitas (Org.), Historiografia brasileira em perspectiva (p. 57-72). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Escolano Benito, A. (2011). Arte y oficio de enseñar. In Coloquio Nacional de Historia de la Educación (p. 17-26). El Burgo de Osma, ES: SEDHE. [ Links ]

Facioli, V. (2008). Um defunto estrambótico: análise e interpretação das Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas. São Paulo, SP: Edusp. [ Links ]

Flory, T. (1986). El juez de paz y el jurado en el Brasil Imperial, 1808-1871: control social y estabilidad política en el nuevo Estado. México, MX: Fondo de Cultura Econômica. [ Links ]

A Folha Nova. (1884, 7 de abril). [ Links ]

Fonseca, T. N. de L. e (2010). O ensino régio na Capitania de Minas Gerais (1772-1814). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Gazeta da Tarde. (1882, 20 de setembro). [ Links ]

Gazeta da Tarde . (1883, 7 de junho). [ Links ]

Gazeta da Tarde . (1884, 26 de abril). [ Links ]

Gazeta da Noite. (1880a, 21 de janeiro). [ Links ]

Gazeta da Noite . (1880b, 22 de janeiro). [ Links ]

Gazeta de Notícias. (1881, 12 de março). [ Links ]

Gazetinha. (1881, 8 de fevereiro). [ Links ]

Ginzburg, C., & Poni, C. (1991). O nome e o como. Troca desigual e mercado historiográfico. In: C. Ginzburg, E. Castelnuovo & C. Poni (Orgs.), A micro-história e outros ensaios (p.169-178). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Bertrand Brasil. [ Links ]

O Globo. (1876, 20 de outubro). [ Links ]

Gondra, J. G., & Schueler, A. F. M. de (2008). Educação, poder e sociedade no Império Brasileiro. São Paulo, SP: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

Graham, R. (1995). Formando um gobierno central: las elecciones y el ordem monárquico em el Brasil Del siglo XIX”. In A. Anino (Coord.), Historia de las elecciones en Iberoamericana, siglo XIX: de la formación del espacio político nacional. México, MX: Fondo de Cultura Econômica. [ Links ]

Holloway, T. (1997). Polícia no Rio de Janeiro: repressão e resistência numa cidade do século XIX (Francisco de Castro Azevedo, trad.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora FGV. [ Links ]

Leenhardt, J. (2006). Imagem e história em Viagem Pitoresca e Histórica ao Brasil de Jean-Baptiste Debret: o enterro do filho de um rei negro. In A. Lopes et al. (Orgs.), História e linguagens: texto, imagem, oralidade e representações. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: 7 Letras. [ Links ]

Lemos, D. C. de A. (2006). O discurso da ordem: a constituição do campo docente na Corte Imperial (Dissertação de Mestrado em educação). Faculdade de Educação da UERJ, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Lopes, N. (2006). Dicionário escolar afro-brasileiro. São Paulo, SP: Selo Negro edições. [ Links ]

Magaldi, C. (2004). Music in imperial Rio de Janeiro: european culture in a tropical milieu. Maryland, USA: The Scarecrow Press Inc. [ Links ]

Mattos, I. R. (1994). O tempo saquarema. São Paulo, SP: Hucitec. [ Links ]

Moraes, F. (2015). O processo de escolarização pública na Vila de Cotia no contexto cultural caipira (1870-1885) (Dissertação de Mestrado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo . [ Links ]

Munhoz, F. G. (2012). Experiência docente no século XIX.Trajetórias de professores de primeiras letras da 5ª comarca da Província de São Paulo e da Província do Paraná (Dissertação de Mestrado em educação). Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo . [ Links ]

O Paiz. (1885, 2 de setembro). [ Links ]

O Publicador. (1866, 31 de dezembro). [ Links ]

Revel, J. (1998). Jogos de escalas: a experiência da microanálise. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Fundação Getulio Vargas. [ Links ]

Pereira de Jesus, R. (2013). Cultura associativa no século XIX: atualização do repertório crítico dos registros de sociedades na cidade do Rio de Janeiro (1841-1889). In 27º Simpósio Nacional da ANPUH. Natal, RN. [ Links ]

Rodycz, W. C. (2003). O juiz de paz imperial: uma experiência de magistratura leiga e eletiva no Brasil. Justiça & História, 3(5), 35-72. [ Links ]

Saes, A. M., & Gambi, T. F. R. (2009). A formação das companhias de seguros na economia brasileira (1808-1864). História Econômica & História de Empresas, 12 (2), 1-36. [ Links ]

Schueler, A. F. M. de. (2007). Professores primários como intelectuais da cidade: um estudo sobre produção escrita e sociabilidade intelectual (Corte Imperial, 1860-1889). Revista de Educação Pública, 16 (32), 131-144. [ Links ]

Schueler, A. F. M. de. (2008). Práticas de escrita e sociabilidades intelectuais: professores-autores na Corte imperial (1860-1890). In Anais do 5º Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação (p. 1-18). Aracaju, SE. [ Links ]

Schueler, A. F. M. de. (2002). Culturas escolares e experiências docentes na cidade do Rio de Janeiro(1854-1889) (Tese de Doutorado em educação). Faculdade de Educação da UFF, Niterói. [ Links ]

Silva, J. G. (2007). Profusão de Luzes: os concertos nos clubes musicais e no Conservatório de Música do Império. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Fundação Biblioteca Nacional. [ Links ]

Teixeira, G. B. (2008). O grande mestre da escola: os livros de leitura para a Escola Primária da Capital do Império Brasileiro (Dissertação de Mestrado em educação). Faculdade de Educação da UERJ, Rio de Janeiro . [ Links ]

Vidal, D. G. (2006). O museu escolar brasileiro: Brasil, Portugal e França no âmbito de uma história conectada (final do século XIX). In A. Lopes, L. Faria Filho & R. Fernandes (Orgs.), Para a compreensão histórica da infância (p. 199-220). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica . [ Links ]

Villela, H. (2002). Imprensa pedagógica e constituição da profissão docente no século XIX: alguns embates. In J. Gondra (Org.), Dos arquivos à escrita da história: a educação brasileira entre o Império e a República (p.97-108). Bragança Paulista, SP: Edusf. [ Links ]

Viscardi, C. (2004). Mutualismo e filantropia. Locus -Revista de História, 10 (1), 99-113. [ Links ]

9“La configuración societaria de la profesionalidad de los docentes, un aspecto esencial para analizar el desarollo del ofício de enseñar”.

11“[...] era que las elecciones podían ser eventos populares donde los líderes locales reafirmaban su preeminência ante uma amplia audiência”.

12“[...] miembros notables del pueblo, cada patrón local demostraba su importancia induciendo a los votantes, sus clientes, a participar en tumultuosas manifestaciones”.

13Prepared by the French inspector Jean-Jacques Rapet and systematized in the book “Coursd’études des écolesprimaires” (Borges, 2014).

14“[...] era una personalidad de carne y hueso cuyos poderes estaban definidos en igual medida por las presiones individuales y comunitarias que por los estatutos y decretos”.

15“[...] como era una figura tan básica y um producto de su ambiente, describir al juez de paz imperial es, em gran parte, describir la vida política y social de la comunidad parroquial brasileña”.

Received: November 13, 2017; Accepted: August 09, 2018

texto en

texto en