Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1519-5902versión On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.18 Campinas 2018 Epub 01-Jun-2018

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v18.2018.e036

Articles

Beyond the domestic gifts: the trajectory of teacher benedita da trindade in são paulo's all-girl schools

1Rede Municipal de Ensino de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, Brasil

Abstract: After the Law of October 15, 1827, which inaugurated public school for girls, the first contest for a female scholl in the province was performed in São Paulo in April 1828. Benedita Trindade do Lado de Christo was approved and became the first public teacher in São Paulo, occupying position of teacher of Sé. She taught until 1859, retiring after teaching for 32 years. This investigation approaches her trajectory to problematize the presence and absence of domestic gifts in the feminine teaching of São Paulo. In a micro-historical perspective, we followed the ‘string of the name’ of the teacher and interpretations are made of her experiences. The sources are the public education legislation, the Public Archive manuscripts of the State of São Paulo, minutes of the City Council of São Paulo and the published notes on female teaching in the periodicals of the province, available at the Newspaper Library of the National Library, covering the period between 1820 and 1875.

Keywords: history of education; teacher; women's education; Empire of Brazil

Resumo: Após a lei de 15 de outubro de 1827, que inaugurava as aulas públicas para meninas, foi realizado, em São Paulo, em abril de 1828, o primeiro concurso para uma cadeira feminina na província. Benedita da Trindade do Lado de Christo foi a aprovada e se tornou a primeira professora pública paulista, ocupando a cadeira da Sé. A mestra lecionou até 1859, aposentando-se após 32 anos na docência. Esta investigação retoma a sua trajetória para problematizar a presença e ausência das prendas domésticas no magistério feminino paulista. Numa perspectiva micro-histórica, persegue-se o ‘fio do nome’ da mestra e tecem-se interpretações sobre suas experiências. As fontes são a legislação da instrução pública, os manuscritos do Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo, atas da câmara de vereadores de São Paulo e as notas publicadas sobre magistério feminino nos periódicos da província, disponíveis na Hemeroteca Digital da Biblioteca Nacional, cobrindo o período entre as décadas de 1820-1875.

Palavras-chave: história da educação; professora; educação da mulher; Brasil Império

Resumen: Después de la Ley del 15 de octubre de 1827, que inauguraba las clases públicas para las niñas, se realizó, en São Paulo-Brasil, en abril de 1828, el primer concurso para una silla vacante femenina en la provincia. Benedita da Trindade do Lado de Christo fue la aprobada y se convirtió en la primera profesora pública paulista, ocupando la silla de la región de la Sé. La maestra enseñó hasta 1859, jubilándose tras 32 años en la docencia. Esta investigación retoma su trayectoria para problematizar la presencia y ausencia de las habilidades domésticas en el magisterio femenino paulista. Bajo una perspectiva micro-histórica, se persigue el "hilo del nombre" de la maestra y se teje interpretaciones sobre sus experiencias. Las fuentes son la legislación de la instrucción pública, los manuscritos del Archivo Público del Estado de São Paulo, actas de la Cámara de concejales de São Paulo y las notas publicadas sobre magisterio femenino en los periódicos de la provincia, disponibles en la Hemeroteca Digital de la Biblioteca Nacional, en el período entre las décadas de 1820-1875.Resumen: Después de la Ley del 15 de octubre de 1827, que inauguraba las clases públicas para las niñas, se realizó, en São Paulo-Brasil, en abril de 1828, el primer concurso para una silla vacante femenina en la provincia. Benedita da Trindade do Lado de Christo fue la aprobada y se convirtió en la primera profesora pública paulista, ocupando la silla de la región de la Sé. La maestra enseñó hasta 1859, jubilándose tras 32 años en la docencia. Esta investigación retoma su trayectoria para problematizar la presencia y ausencia de las habilidades domésticas en el magisterio femenino paulista. Bajo una perspectiva micro-histórica, se persigue el "hilo del nombre" de la maestra y se teje interpretaciones sobre sus experiencias. Las fuentes son la legislación de la instrucción pública, los manuscritos del Archivo Público del Estado de São Paulo, actas de la Cámara de concejales de São Paulo y las notas publicadas sobre magisterio femenino en los periódicos de la provincia, disponibles en la Hemeroteca Digital de la Biblioteca Nacional, en el período entre las décadas de 1820-1875.

Palabras clave: Historia de la Educación; Profesora; Educación de la mujer; Brasil Imperio

Introduction

Death - After long sufferings, died yesterday, at advanced age, Mrs. D. Benedita da Trindade do Lado de Christo, a public professor who has been a retired teacher for many years.

The deceased was one of the first public teachers of the capital, where, during her time of teaching, she always had a lot of fame and sympathy both for her abilities and for her excellent character.

Her school was trustworthy and therefore very frequented, so much so that even today there are still in our best society respectable and virtuous mothers of the family who were disciples of Mrs. D. Benedita da Trindade.

Retired for a long time, her life was lately obscure and very poor and she was until the extreme hour, but always worthy of consideration and appreciation.

(Nota de falecimento... 1875, p. 3).

The note in the Correio Paulistano, dated October 1875, about the death of the teacher Benedita da Trindade do Lado de Christo after ‘long suffering’ in an ‘obscure and very poor’ condition raises questions when we insert her into the teacher’s trajectory. She is the pioneer as a public teacher of the first letters of the province of São Paulo who, throughout her life, has taken innovative initiatives, such as enrolling for a competition for teaching (newly created position), taking examinations, being approved, teach for 32 years fulfilling administrative requirements of the position, act as examiner of other candidates, and other possibilities of teaching on the scene. The latest values of her retirement are discrepant with the condition so precarious at the time of death and evidence that paid work was a material necessity for this teacher and possibly for other women who sought the public teaching as an option in the labor market.

The imperial city of São Paulo, capital of the province, was contemplated with the creation of a girls’ class in 1828, six months after the law of 1827. The entrance of Benedita da Trindade into the public teaching profession took place through a competition in which other two candidates participated in. They were: Benedita Maria de Jezus and Joaquina Roza de Vasconcellos. In the application for registration, the candidate Benedita da Trindade attached a copy of her baptismal certificate. By this, it is known that she was approximately 28 years old (she was baptized in 1800). The baptism was held in Freguesia da Sé with Manuel Buenno de Azevedo, single, aide, and Gertrudes M. Buenno, married as godparents, all from the same parish. The mother and the godparents seem to have lived near the parish of Sé and shared the surname, since Benedita da Trindade did not have the name Buenno. Her mother, Anna Buenno was single and had two other children29, Maria Leocádia do Sacramento30 and Jesuino Buenno de Azevedo31. The son became a priest, identified by the memorialist Antonio Egydio Martins as the ‘Father Colchete’ (Martins, 2003, p. 307, author’s emphasis). Both daughters were celibate, bastards and officially acted in women’s education in the city of São Paulo in the 1830s to 1850s32. As free, possibly poor, bastards, and single-mother daughters33, it is likely that access to education and to the public teaching profession was hampered by obstacles of a patriarchal, hierarchical, and excluding society, as was 19th century Brazil. On the other hand, it is quite possible that the entrance and stay in the female public education of the province of São Paulo were favored by the backs of prestigious subjects in the local society. The sources did not allow us to identify how the sisters took ownership of the literate culture and possible clientelistic networks.

The objective of this article is to interpret aspects of the teacher’s trajectory as an experience that makes it possible to problematize the presence and absence of domestic gifts in female teaching profession in the second and third quarters of the 19th century in São Paulo34. In order to do so, we have taken up previous investigations that addressed the experience of Mrs. Benedita, elements of the context at the time and sources, some already known and others not yet explored by historiography. Some studies in history of education have focused on teachers in the 19th century35 and contributed to the understanding of 19th century teaching work. We believe that knowing some aspects of the history of the teaching profession through the exercise of gender otherness allows not only to tell about the specificities of women’s history, but also offers the possibility of problematizing 19th century teaching profession from another perspective (Perrot, 1995, 2007; Tilly, 1994).

As a starting point for this narrative, we returned almost five decades before the teacher’ s death to analyze the legislation that made possible the trajectory of Benedita da Trindade in the teaching profession - and of many other female teachers throughout the empire of Brazil.

The legal creation of the girls’ first letters classes

The general law of October 15, 1827 predicted the possibility and defined the general characteristics of the female class. Its articles determined the criteria for creating chairs; they defined salaries and possible teacher bonuses; indicated the method of preference; signaled a few material questions regarding building and utensils; determined the knowledge that should be taught; explicit the form of teacher provision and recruitment; they defined the post of public teacher of first letters as lifelong; and pointed out that the punishments should be those of the Lancaster method. Adriana M. P. Silva (2007) considers that the law of October 15 defined the factor ‘population’ as the main criterion for creating classes of first letters. The possibility of opening classes both in cities and in villages and parishes - and the absence of a defined minimum number of inhabitants - opened up to the demands of the population and negotiations between local and provincial powers. Cynthia Greive Veiga (2007) considers that, with regard to the application of legal prescriptions, there was no uniformity in the different provinces. For José Gondra and Alessandra Schueler (2008, p. 53), this law ratified the organization of elementary public education in the form of “[…] schools of reading, writing, counting and believing […]”, already contemplated in the royal classes36.

However, as far as content is concerned, the imperial law of 1827 provided for a small increase in relation to the royal classes, through Article 6. It included the teaching of “[…] practices of broken, decimals and proportions” (Brasil, 1827). Such knowledge was related to marketing by weight, measures and product values; were therefore useful in business practices among other activities in the world of work. Geometry was added that was related to the practices in construction and agriculture. The teaching of the grammar of the national language and the suggestion of the ‘Constitution of the Empire’ and ‘History of Brazil’, as readings, indicates the concern with the establishment of a national language and the formation of the citizen for the consolidation of a Nation-State. Hilsdorf (2003, p. 44) considers that the law of 1827 represented a “[…] maintenance of public single classes of first letters of Pombaline origin”. The author highlights the inclusion of girls and the adoption of the mutual method as innovations.

In three short articles, women’s school education was inaugurated legally, five years after the country’s political emancipation. The three specific articles created the classes, defined the knowledge to be taught and ordered of the teachers. The creation of the chairs was conditional on the population criterion (such as the men’s) and the judgment of the provinces’ presidents in Council. Article 12 presents the gender differences. The knowledge provided in the first letter schools had been object of article 6, however, after announcing the creation of the female classes in article 11, the law presents an adequacy of teaching materials. This adjustment begins with the exclusion of ‘Geometry’ and the limitation of arithmetic to the four operations (Brasil, 1827, p. 71) 37 in girls’ classes. Regarding the remuneration, the same salaries were foreseen for female and male teachers - an equity that is worth noting because of the lack of marked asymmetry in gender relations in the period.

The law of 1827 was conceived within a paternalistic and unequal society in which the insertion of women into public literate spaces38 was slow, tutored and faced resistance. However, there were women who worked dynamically in public spaces, such as the streets of the city, inserted into the world of work as laundresses, dressers, grocers, quitters, midwives, seamstresses and other crafts. In the classic study entitled Quotidiano e poder em São Paulo no século XIX, Maria Odila LS Dias (1995)39 investigates “[…] poor women, alone or heads of families” (Dias 1995, p. 8) and their agencies in the world of work and asks how they were looking for survival and that of their dependents. There was an iconsphere of the “[…] feminine closure in the domestic space […]” that contrasted with “[…] a complex framework of differentiated social positions and functions […]” giving “[…] visibility to the multiplicity of experiences of the feminine in the period” (Gouvêa, 2003, p. 5). In the thesis that gave rise to the present study, we outline the contours of the world of women’s work, in which we highlight the various possibilities of being a woman who populated the experiences in São Paulo of the nineteen century, with the profound social, gender and racial inequalities of a slave country (Munhoz, 2018, ).

The feminine presence in the world of work was amplified at the time of the creation of the girls’ classes, a project officially elaborated exclusively by men in a context in which women were considered inferior and lived, almost always, under male guardianship. In discussions of the Constituent Assembly, prior to the 1824 Constitution, the theme of girls’ instruction was present. For the Constituent Assembly, an education commission was elected40.

Martim Francisco Ribeiro de Andrada had written, in 1816, a proposal for reform of minor studies in Sao Paulo that served as a guide for such a commission. The deputy Maciel da Costa (Marquês de Queluz) suggested that instruction be offered to the “[…] Brazilian youth [...] of both sexes […]”, since he considered that the Assembly did not intend “[…] to exclude women from the benefit of public education [and that...] to deprive such a large and interesting part of the human race, destined by nature and society to such important functions, was a grave inconvenience” (Sessão da Assembleia Constituinte, 1823, p. 55-56). The draft Constitution41 was not approved, but the proposal was taken up by the Commission that proposed the general law of Public Instruction of 1827. The deputies defended women’s education by arguing “[…] the usefulness and necessity of the good education of women […]” and emphasized that “[…] ordinarily Brazilian women endowed with talent [were] condemned to the deepest ignorance, being deprived even of those first principles of public morality, indispensable for being good mothers of families” (Excerpt from the deputy Romualdo de Seixas, Sessão da Câmara Geral dos Deputados, 16/06/1826 apud Rodrigues, 1962, p. 65). The offer of public instruction to the female population was aimed at overcoming superstitions and creeds, in the eyes of these rulers and their liberal principles.

There was the encouragement of female instruction in a format that outlined a school-based version of the moral codes of gender conduct that permeated society - as in any historical period - in which the social roles of ‘family mothers’ and wife were at the center. The law indicated the substitution of some knowledge - in relation to male classes - according to the social patterns of gender. Instead of “[…] practices of broken numbers, decimals, and proportions [and] more general notions of practical geometry […]” (intended for boys) - teachers should teach their pupils “[…] gifts that serve the domestic economy” (Brasil, 1827, p. 71). There was no specific definition of what such gifts would be, but the practices were mainly in the teaching of sewing and embroidery. The theme is significant in the history of the feminine teaching of São Paulo and, therefore, it is object of interpretation in the item that follows.

Domestic gifts in first letter classes in the province of São Paulo

In 1854, the district inspector of Sorocaba asked the general inspector of the Public Instruction what the ‘gifts’ were, who answered that they were “[…] needlework, embroidery, etc.” (Ofício do inspector de Sorocaba…, 1854)42. A quarrel around the teaching of domestic gifts in the public feminine teaching of São Paulo had begun much earlier. The question pervaded the practices of several teachers and the inspection of public instruction, as Leda Rodrigues (1962, p. 83) pointed out.

It is interesting to note the insistence with which both the District inspectors, the district attorneys, the General Inspector and the Presidents of the Province insisted that the teachers dedicate themselves carefully and carefully to the teaching of needlework.

Leda Rodrigues (1962) devoted herself to research on female education in São Paulo - from the colonial period to the Proclamation of the Republic and inventoried sources that indicated the presence of girls and women in school education processes between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries from a diachronic perspective. Many of the documentary references and questions were taken up by the historiography of São Paulo education.

Maria Lúcia Hisldorf, in her research on teacher Benedita (Hilsdorf, 1997), in her studies on the Educators’ Seminar (Hilsdorf, 2010), points out that the first mention, the absence of teaching gifts in the classes of the teacher of the city of São Paulo, in the sources, was held in the manuscript letter sent by the then director of the Seminary, Eliziária Cezília Espínola43, in September, 1829. The Seminário de Educandas was an establishment created in 1825 during the presidency of Lucas Monteiro de Barros (1st president of the province). For Hilsdorf (2010), this is one of the actions of the illustrated liberal philanthropy of the province of São Paulo44. The director’s manuscript reported on the Commission’s survey appointed by the House and brought a claim for salary increase by comparing the values of her salary and that of Benedita da Trindade, the first public teacher in the province, as well as the comparison between the works carried out by each one; Eliziária Espínola regretted that she received only 76$800 réis a year to feed, dress, give religious education, teach girls “[…] to read, write, count, bake, spin, sieve, embroider, make nets, make flowers […]”, and still performed the works of revenue, expense, and list writing that she was required to send each quarter as a director; while the teacher taught “[…] only reading, writing and nothing else […]” and enjoyed vacation and holidays (such as Thursdays) receiving an annual salary of 300$000 (Ofício de Eliziária Cezília Espínola, 1829)45.

The city of São Paulo was, in the middle of the 19th century, a small urban area with a little more than 22,000 inhabitants (Muller, 1923). The director of the Seminary in 1829, Eliziária Espinola, knew not only the value of the salary of the public teacher, but also what she taught (or did not teach) in her classes. If the first information was accessible in newspapers, as it appeared in the minutes of the session of the House and in documents of the provincial government that were published in the scarce and incipient periodicals; the second was probably information obtained from orality in relationships and secret talks. The point is that the absence of the gifts was not initially the object of a complaint of the inspection of the Instruction, but was informed in a demand of a ‘work colleague’, as an argument to justify her request for increase. Just over three years later, teacher Benedita herself (Ofício de Benedita Trindade do Lado de Christo, 1833a) reported that

The manner in which I give effect to Art. 12 of the Law of November 1546 of 1827, it is incumbent upon me to inform Your Excellency that I am ready to teach girls (never less than 50 effectively) 2 hours in the morning and as many as in the afternoon according to the Law on every working day, including the teaching of reading, writing, arithmetically speaking, the grammar of the national language, the principles of Christan Moral, and the doctrine of the Religion of the Empire: I also make them read the Political Constitution and the Geographic part of it, I cannot apply the girls to this study for the History of Brazil for lack of this work. Finally, I do not neglect to teach them everything that can make them good daughters of the same Empire and good mothers of families. I have offered to inform Your Excellency. May God always keep Your Excellency. São Paulo. February 5, 1833.

Article 12 was what replaced geometry with gifts. Curiously, although Benedita da Trindade states that she is going to explain ‘the manner in which I give effect to Art. 12’, she did not mention the gifts. But, unlike Eliziária Espinola stated, the city’s teacher insisted on registering that she taught much more than just ‘reading and writing’. She listed all the other knowledge required by law, except for gifts, starting with reading, writing and arithmetic, passing through religion, politics and geography and justifying the absence of history due to lack of textbooks. For the teacher, teaching ‘everything that can make girls good daughters of the Empire and good mothers of the family’ meant teaching reading, writing, etc. and did not include sewing, embroidery and the like. Indirect insinuations such as those of the first director of the Seminário de Educandas, more explicit denunciations and questions about the subject occurred since 1829 advancing throughout the decades of 1830 to 1850. It was possible to locate a set of records referring to the complaint of the gifts, between 1829 and 1858, in the chairs of the Sé and in other girls’ classes. The only case prior to the 1850s is that of Benedita da Trindade.

In the majority, the charges and complaints stand out so that article 12 of the law of October 15, 1827 was fulfilled and the gifts effectively taught. Between the end of 1832 and the beginning of 1833, the City Council of São Paulo - which was responsible for supervising public education47 - registered the first questions to the professor of the Sé about the absence. On this occasion, not teaching the gifts seemed not to cause great controversy, although its teaching was already provided by law. The ‘failure’ was identified, but the justifications presented - lack of time or lack of knowledge about what knowledge included - were accepted; at least by a portion of the members of the inspection.

On March 26, 1832, a ‘Regulation for the teachers of the Province of São Paulo’ had been approved. This regulation is important because it contains instructions directed specifically to teachers of first letters from São Paulo, and also because one of its articles has been literally quoted by Professor Benedita da Trindade. In May 1833, in an answer to a letter of May 8, which questioned her about the absence, the teacher Benedita da Trindade (Ofício de Benedita Trindade do Lado de Cristo, 1833b, emphasis added) wrote explicitly:

Governing myself in the teaching of my pupils by the Regulation given by the Excellency Government of this Province, dated March 26, 1832, that on April 11 of the same year I was informed by the Municipal Council ‘not to teach the necessary gifts to the domestic economy provided for in Article 12 of the Law of 15 of october, because they are excluded by the content of Article 3 of the same Regulation that goes together in copy’.

‘However, if Your Excellency considers it right that I should teach these gifts, I will execute your Orders with the same zeal and activity with which I have hitherto served’. God Save Your Excellency for many years.

São Paulo May 13, 1833.

Benedita da Trindade - Professor of Girls’s School (Emphasis added).

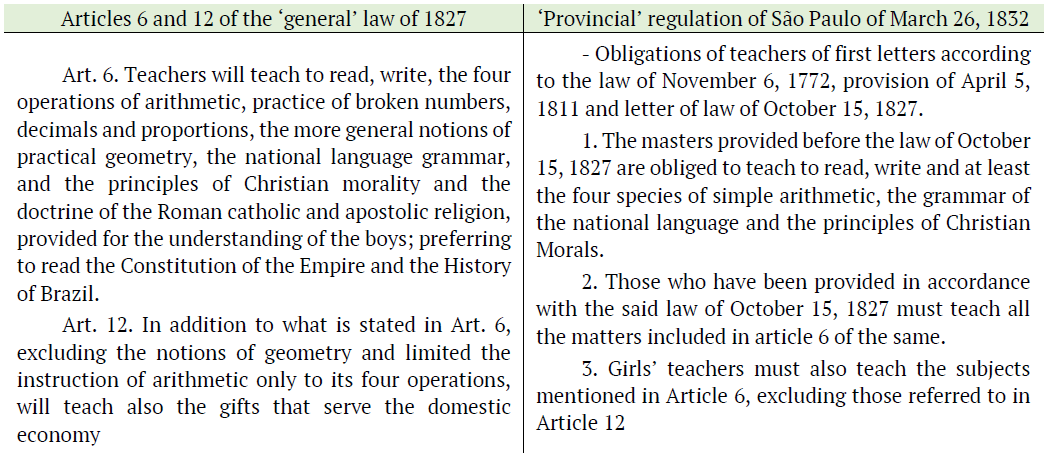

The teacher’s response indicates that in 1833 it was possible to negotiate the teaching of domestic gifts. To legitimize her justification, Benedita da Trindade copied article 3 of the “Regulation given by the Excellency Government of this Province of S. Paulo on March 25, 1832 to the Teachers of first letters” (Regulamento… 1832) and attached to the letter of reply. According to the copy, the article stated that ‘Girls’ teachers should also teach the subjects referred to in Article 6 to the exclusion of those referred to in Article 12. When we look at this regulation, we find an ambiguity in the legislation. The Box 1 below lists, on the left, the transcription of articles 6 and 12 of the general law of 1827 and, on the right, the first three articles of the provincial regulation of 1832:

Source: Munhoz (2018, p. 122), (Brasil, 1827, p. 71) e O Novo Farol Paulistano (1832, p. 1).

Box 1: Articles of the general law cited by the provincial regulation of March 26, 1832.

Article 3 of the 1832 regulation dictated that teachers should teach the subjects of article 6 of the law of 1827: “[…] read, write, the four operations of arithmetic, practice of broken numbers, decimals and proportions, more general notions of geometry practice, the grammar of national language, and the principles of Christian morality and the doctrine of the Roman Catholic and apostolic religion” (Brasil, 1827). It also determined the “[…] exclusion of the [subjects] ‘referred to in article 12’” (Brasil, 1827, author’s emphasis). It is precisely in this section that one finds the ambiguity. Was the exclusion provided for in Article 3 of the 1832 Regulation a reiteration of the exclusion of the geometry of girls’ classes, already provided for in general law, or did it refer to the exclusion of domestic gifts, which was the subject added by this article? The social practices would have resulted in a provincial norm that returned to the first letter classes for the knowledge of reading, writing, arithmetic and religious doctrine or the provincial law would have reinforced the sewing, inside the schools, differentiating the knowledge according to the standards of gender behavior of the time?

Cunning and creative (Certeau, 1994), teacher Benedita da Trindade used the regulation to justify the absence of the gifts in her classes. The difficulty in contemplating the teaching of the gifts in public classes of first letters of the Sé had already arisen and it was considered that the time was scarce for its teaching added to the one of the other subjects; thus, the cunning, the legal repertoire and the position of the teacher, added to the obstacles already faced for the effectiveness of the law could have justified its exclusion. The teacher knew the laws and followed their promulgations, mobilizing them to justify what she did not teach in her classes. Notwithstanding Benedita’s interpretation, the understanding that the regulation reinforced the exclusion of geometry is the most plausible, since it ordered to teach the subjects of article 6 of the law of 1827 to the exclusion of those of the same article 6 that were mentioned in the article 12, that is, ‘broken, decimals and proportions, the more general notions of practical geometry’. In this reading, the domestic gifts were not specifically regulated by the Paulista regulation.

The manner in which Benedita da Trindade put herself also allows us to speculate on a possible political position by choosing to follow provincial law (1832) and not general law (1827). This initial moment of the ‘domestic gifts quarrel’ unfolded in the time of the Regency in which the oppositions between provincials and centralists were recurrent in several provinces of the Empire (Mattos, 2004). In the early 1840s, liberal revolts occurred in Minas Gerais and São Paulo, “[…] contrary to the centralist tendency that was consolidating in the country […]” understood by historiography as “[…] a liberal reaction against the conservative ‘return’ instituted mainly by the Law of Interpretation to the Additional Act and the Reform of the Criminal Code” (Oliveira, 2008, p. 6, author’s emphasis). In this perspective, the teacher from São Paulo may have been a provincial who expressed her position through pedagogical practices48. The participation of the teacher in the ‘Sociedade Sete de Setembro’ 49 is a clue to her political commitment. In January 1859, she was included in the list of members who contributed with cash donations to the celebrations of Independence promoted by society (Correio Paulistano, 1859).

Subsequent denunciations by houses and inspectors made against Benedita da Trindade and other women teachers, demanding the teaching of the domestic gifts, reinforce the interpretation that the regulation did not exclude the gifts and, consequently, the alignment between those in charge of the local inspection of public education and the rulings of the Imperial court. The character of the law is apprehended as a ‘field of struggles’, a negotiating arena (Thompson, 1987).

Maria Lucia Hilsdorf (1997) pointed out that the regulation that Benedita da Trindade relied on in her defense was subsequent to the fact that had generated the complaint. That is, it was known, through the requirements of the director of the Seminário de Educandas, that since 1829 (at least), the teacher stopped teaching sewing and the like. Considering this fact, Hilsdorf (1997) mocked that the teacher’s explanation ‘was irrelevant’, since she did not teach the gifts even before the regulation allowed the exclusion. It is even more ironic (and astute) to think that the teacher justified the absence by using a regulation that determined exactly the opposite.

Moving forward in the problematization of the absence of gifts, it is possible to interpret the legal ambiguity and the teacher’s responses as evidences of a literate resistance in the girls’ public classes of first letters of the Sé and of a possible tradition of the transmission of the gifts inside the domestic spaces. In a perspective in which laws are analyzed “[…] not only as a legal order, but also as language and social practice” (Faria Filho, 1998, p. 92), with a view to highlighting the negotiations that cross them. Edward Palmer Thompson (1998, p. 86) emphasizes ‘custom’ as an “[…] interface of law with practice […]”, which can be regarded both as “[…] praxis [...] and also as law”. For the author, customs rest on “[…] two pillars - the use in common and the immemorial time” (Thompson, 1998, p. 86). For Adriano Luiz Duarte,

What seems fundamental, in Thompson’s suggestions, is to perceive the relation between custom and law. And this relationship is always unstable and changeable. An example of this is given by the fact that registering customs, sometimes orally inherited, was a way of guaranteeing customary rights in the law. And, to ensure the maintenance of rights, custom could become very complex and sociologically sophisticated. That is to say, there was nothing static either in the custom nor in the law. Exactly so, the law does not appear as an instrument of domination of one class over another, but as an open and indefinite field of struggles, in which the complexity of customs plays a decisive role (2010, p. 177).

Working with these reflections on ‘custom’ and ‘law’, it is possible to risk an interpretation for the thematic of the gifts in the 19th century lands of São Paulo. The issue was not of domination of one class over another, but gender-based social relations that involved power, hierarchies and negotiations between subjects in the struggle for domains in different spaces. In this scenario of the young Empire of Brazil, one observes the dynamicity and the arena of conflicts between customs and law. The transmission of needle knowledge constituted the female experiences in the spaces of the house; weaving and sewing constituted the set of minimum knowledge for human survival, such as food, housing, and so on and its transmission was part of the family dynamics. When we observed the fires (homes) in the city of São Paulo, we identified many women who reported living from their seams (Dias, 1995).

In the same period, the female public education was inaugurated in the different provinces. It is important to emphasize that before 1827, other experiences of instruction of the female population were experienced since the colony with private female and male teachers (paid or not) and preceptors. Official female schooling was too recent to rely on the pillar of ‘immemorial time’ (Thompson, 1998) - and it was effected through a slow process of creation of chairs. However, boys’ public education already had a longer time in Brazil, with royal classes, and was in line with the tradition of the former metropolis, inserted among the western countries.

Guy Vincent, Bernard Lahire and Daniel Thin (2001, p. 27) called the social process that made the form of hegemonic school socialization an “[…] invention of the modern school form”. This ‘form’ is understood as one of the interfaces of the new urban order that redefined civil and religious rights from the 17th century onwards in Western countries. This form of socialization was accomplished through the constitution of specific spaces and the pedagogization of social relations of learning. There was a systematization of teaching with formalized book-based knowledge and the learning of specific forms of power. The authors point out the deep links that link school and written culture to a socio-historical whole. The emergence of modern states was accompanied by the organization of secular teaching systems and a continuous movement of homogenization of the various models of socialization and transmission of knowledge. In these official educational systems, in order to access any kind of school knowledge, it is necessary to master the written language (Vicent, Lahire & Thin, 2001).

In this perspective, the absence of domestic gifts in the classes of teacher Benedita da Trindade can be read as an interface of this process of invention of the modern school form and of affirmation of the centrality of the writing-based knowledge in the schools, including in a girls’ class, standing out in relation to the gifts, which were already transmitted in domestic spaces.

In July 1838, the city council considered that ‘the teacher show[ed] zeal’ and that she adopted the catechism “[…] of Bishop Colbert, who in fact [was] one of the best” (Ofício da Câmara ao Presidente da Província, 1838, p. 133). The opinion acknowledged the quality of Sé’s public girls’ class and ended by stating that the time of 4 hours, determined by law, was little for what was “[…] taught and therefore [was] unworkable the teaching of sewing” (Ofício da Câmara ao Presidente da Província, 1838, p. 133). Thus, the justification for lack of time - quite feasible - was triggered by the teacher, and for some time considered legitimate by a portion of the rulers who inspected the public education.

However, a pressure movement so that the domestic gifts were included in the girls’ schools was being strengthened. In 1835, the inspection suggested a readjustment of the hours of the classes of the teacher Benedita to contemplate the teaching of these knowledge.

In the course of this Class it is impossible for the Teacher to fulfill the order of teaching gifts for domestic use: ‘I therefore think it necessary that you represent the Your Excellency President, so that he (if he finds it useful) will alter the course of her teaching, forcing her to teach in the morning to sew and embroider, and in the afternoon, to read and write with advantage for opposing objects, nor will the family fathers want to submit their daughters to such a light teaching as now happens’ [...] (Ofício de José Ignacio Silveira da Mota, 1835, emphasis added).

The charge for teaching sewing and embroidery was accompanied by suggestions for redefinitions in the division of time between the different subjects. Vincent et al. (2001, p. 29) point out that the school socialization mode also accomplishes the “[…] schooling of social relations of learning [and is] inseparable from a scripturalization-codification of knowledge and practices”. Possibly, the gifts also underwent a process of codification to become feasible inside the schools. Margin for negotiation was reduced throughout the 1830s. Literate resistance provided even more space for the invention of a ‘gifted’ tradition in girls’ schools. In 1846, Provincial Law 34 determined that

Art. 2. The primary education for the female gender shall consist of the same subject matter as the preceding article, excluding geometry: and limited to arithmetic the theory and practice of the four operations; and also, of domestic gifts that serve the domestic economy (São Paulo, 1846).

Leda Rodrigues (1962) and Maria Lucia Hilsdorf (1997) agree on the interpretation that the pressure movement has been accentuated throughout the 19th century. For Hilsdorf, the behavior of not teaching the gifts did not mean that teacher Benedita da Trindade “[…] violated a norm and reversed an image, [or that] she was ‘advanced for her time’ or even feminist” (Hilsdorf, 1997, p. 99, emphasis added). But that there was a social change, from the beginning to the second half of the 19th century, which came about through a pressure of society, through legislation and normalization, “[…] to make all women appear as the ‘angel of the home […]” with the imposition of ‘feminine work’ (Hilsdorf, 1997, p. 99, author’s emphasis) to public girls’ classes through supervision, denunciations and admonitions to teachers.

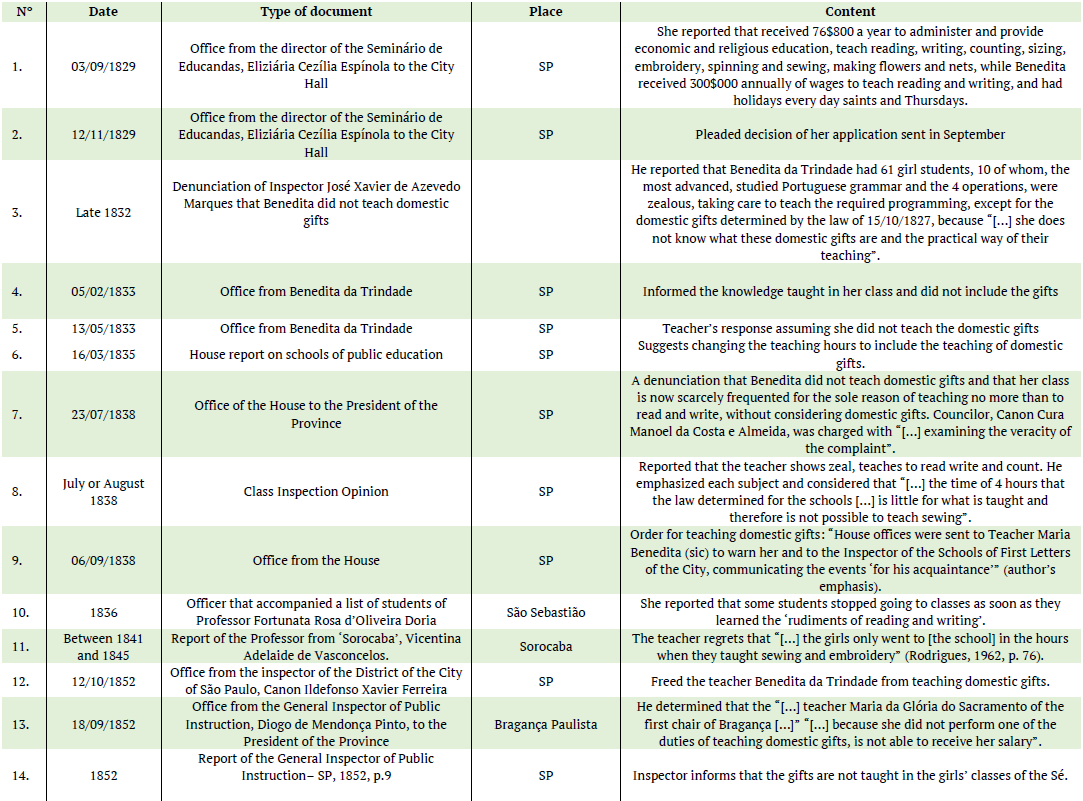

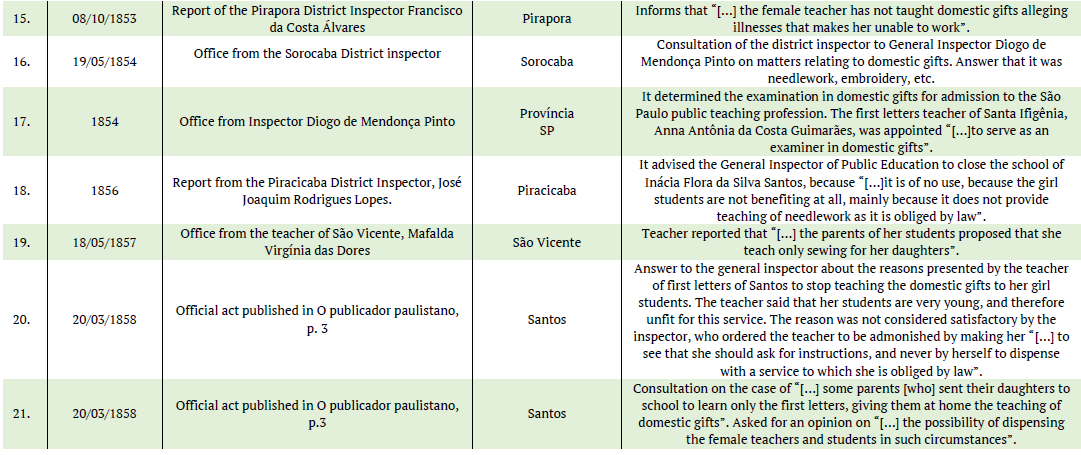

Besides Benedita da Trindade, other female teachers stopped teaching the gifts and were reprimanded for it. The difference is that the other episodes are all after 1850. Box 2 lists the cases that involved issues related to the teaching of domestic gifts.

Source: Munhoz (2018, p. 39), Rodrigues (1962), Hilsdorf (1997), reports of presidents of the Province of São Paulo; reports of the Inspector of Public Instruction Diogo de Mendonça Pinto, offices from the City House of São Paulo and notes published in the periodicals of the Province of São Paulo.

Box 2: Notes on the absence of teaching domestic gifts in public girls’ classrooms.

In September 1852, the general inspector informed the president that Professor Maria da Glória do Sacramento, from Bragança Paulista, was not qualified to receive her salary because she had not performed the duty of teaching domestic gifts. In Piracicaba50, in 1856, the district inspector advised that general the inspector close the school of teacher Inácia Flora da Silva Santos, for “[…] being of no use, because the girls are not benefiting, especially because she does not provide education of needlework as it she obliged by law” (Relatório do Inspetor de Distrito José Joaquim Rodrigues Lopes, Sorocaba, 1856 apud Rodrigues, 1962, p. 84).

In the same perspective, there were cases of families that only demanded the teaching of sewing in the classes of first letters. In 1857, the female teacher of São Vicente informed the General Inspector that “[…] the parents of her girl students had proposed that she teach only sewing for her daughters, because reading and writing would do them no good and that, therefore, it was a nonsense spend time to learn this” (Ofício da Professora pública de primeiras letras, Mafalda Virgínia das Dores, 1857).

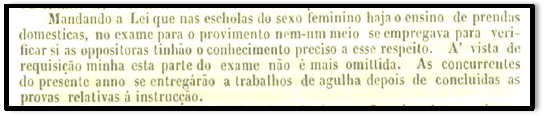

Leda Rodrigues (1962) and Maria Lucia Hilsdorf (1997) agree that such pressures led the General Inspector of Public Instruction to interfere in the 1850s by imposing that “[…] the examinations of the candidates for the position of public female teachers to include performance in needlework” (Hilsdorf, 1997, p. 99). We agree with interpretation; we consider that the apex of this pressure movement was the inclusion of an evaluation in gifts in the examinations for admission in the feminine public teaching from 1854, when the general inspector of the Public Instruction, Diogo de Mendonça Pinto, triggered the resources available to ensure compliance of law. He devoted himself directly to the project and recorded in the 1854 report:

Source: Public Archive of the State of São Paulo, Digital Repository.

Figure 1: Excerpt from the General Report of the Public Instruction, SP, 1854, p. 14.

The General Inspector’s request can be read as a strategic action by a man in a place of power (Certeau, 1994), in order to ensure compliance with the law. The implementation of the examination in gifts, in the province of São Paulo, occurred in the same year in which the ‘Decree 1331-A, of February 17, 1854’ was promulgated in the Court, the reform Couto Ferraz, that determined, in article 19, that “[…] in examinations for female teachers, the examiners will hear the judgment of a public female teacher, or a lady appointed for this purpose by the Government, about the various needlework” (Brasil, 1854, p. 45).

The temporal and content similarities between the decree of the Court and the provincial law indicate the circulation of laws and relations between the province of São Paulo, Court and other provinces, as well as their social representations in the different regions of the Empire. The Couto Ferraz decree, of February 1854, had an intense circulation throughout the country and probably influenced Diogo de Mendonça Pinto and other 19th century characters of São Paulo, contributing to the strengthening of a culture that devotes a significant part of the girls’s school time to learning the domestic gifts (the general report of the São Paulo Public Instruction of 1854 was in December). Heloísa Villela (2002) and Mattos (2004) emphasize that the imperial state wanted the teacher to be an agent capable of reproducing a knowledge that preserved society as presented and did not subvert the social structure. The establishment of the examinations in gifts was one of the actions, concomitant to the intensification of the fiscalization, that favored the accomplishment of the needleworks in the feminine public classes and the relative maintenance of the hegemonic relations of gender. There were changes, but these were aligned to standards of conduct.

To perform the examinations on gifts, it was necessary the participation of a sapient person in the needleworks for the evaluation of the candidates. As it was a domain considered feminine, the chosen one for the accomplishment of these examinations was Anna Antonia Costa Guimarães - public professor of the chair of Santa Ifigênia from 1853, graduate at Seminário de Educandas. As a child, she entered as an orphan the Seminário in 1829 (the year following the creation), at approximately nine years of age. In 1839, director Maria Leocádia do Sacramento reported that Anna Antonia, aged 19, a native to Jundiaí and daughter of Francisco de Paula Ferreira, “[…] was able to read, write, count, sew, embroider, mark, to make nets and the most domestic uses” (Relação de educandas…, 1840). The former student who became a public teacher continued to reside in the Seminário even after her appointment.

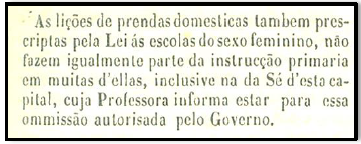

If the pressure for teaching gifts, begun in the second half of the 1830s, can be considered victorious with the requirement of the examinations for the beginners in teaching profession from 1854, the historical processes are crossed by negotiations and projects different from those that are have become hegemonic. On October 12, 1852, “[…] the teacher Benedita da Trindade had been able to dispense her disciples from manual labor, proving to be scarce time to teach reading and writing and suggesting that these gifts could be learned by the pupils in their own homes” (Rodrigues, 1962, p. 83)51. Thus, even after two decades of denunciations and charges, in 1852 the General Inspector of Public Instruction exposed (and lamented) in the general report of the Public Instruction that the teacher of the Sé - the only chair in the capital until 1853 - still did not teach the domestic gifts:

Source: Public Archive of the State of São Paulo, Digital Repository.

Figure 2: Excerpt from the general report of the Public Instruction of Diogo de Mendonça Pinto, 1852, p. 9.

The inspector insisted that the teacher’s ‘omission’ had been authorized by the government, according to the teacher’s own information. In the province’s main female public education chair, the almost total absence of domestic gifts is observed for more than 20 years, in spite of what was prescribed by legislation and successive charges. We located 14 lists of Benedita da Trindade students from the years 1832 to 1842 and from 1846 to 1848; in them, the teacher reported the progress of her pupils, and sewing was cited in only two years: 1839 and 1840, and even in these years it was mentioned only in the description of the state of knowledge of five girls (43 were enrolled in 1839 and 41 in 1840). It is possible that the families have requested the learning or that the teacher has registered knowledge that was not taught in the school. After 1840, there were other denunciations of absence of the gifts in the classes of the Sé.

Although the cases of charging and denunciations of the teachers in cases of absence of the teaching of the domestic gifts prevailed, there were situations in which the schools were cogitate to leave aside the sewing and to concentrate on the teaching of reading, writing and arithmetic. In Santos, some families demonstrated to the government suggesting the exclusion of the subject. The newspaper O Publicador Paulistano (1858, p. 3) mentioned the case of “[…] some parents [who] send their daughters to school to learn only the first letters, giving them at home the teaching of domestic gifts […]”, requesting an opinion from the general inspector about the possibility of dispensing the teacher and her students in such circumstances. The response was not localized, but the application record evidences the coexistence of different perspectives of girls’ school education within the same society. Although in much smaller numbers, the experiences of female instruction without the gifts were a possibility in the province of São Paulo and it is fundamental to give visibility to these dissonant experiences. In history, non-hegemonic projects matter in the construction of narratives that seek to interpret how subjects dealt, negotiated, conformed and resisted in face of the constraints in which they lived. To regard them as historical experiences is to interpret the voices of subjects in their time and tradition as an arena of conflict, “[…] an arena of conflicting elements, which only under imperious pressure [...] takes the form of a ‘system’” (Thompson, 1998, p. 16-17, author’s emphasis).

Between the 1830s and 1850s, the charge for teaching domestic gifts crossed the trajectory of teacher Benedita da Trindade and other teachers from São Paulo, with a more gifted tradition in women’s teaching profession, which, however, did not prevent dissonant experiences, such as class of Sé, in which the absence of the teaching of needleworks is observed.

Final Considerations

To the unprecedented experience of examination for admission to the teaching profession were added other news as the teaching was gradually being appropriated by women teachers in the province. If, in 1828, they debuted as candidates in the contests, over the years, they were incorporated into the examining commissions that evaluated the new ‘opponents’52. According to Leda Rodrigues (1962, p. 81), since 1844, Benedita da Trindade was summoned to appear at the government palace composing commissions “[…] made up of bachelors of the Faculty of Law and clergymen”. In 1851, the teacher’s convocation was published in the newspaper O governista (1851). Composing a committee formed by the teacher of the Normal School Manoel José Chaves53, the professor of the Faculty of Law of Largo de São Francisco and provincial deputy, Dr. Antonio Joaquim Ribas54 and the teacher of first letters of the first chair of the city of São Paulo, Carlos José da Silva Telles (who had adopted the mutual method); teacher Benedita da Trindade - occupying the symbolic last place of the list, but included in the list - was among the elite of teaching of the capital of the province of São Paulo. In January, 1852, she was again called “[…] to examine the competitors to the female chairs of first letters” (A Aurora Paulista, 1852, p. 1).

In the interior of the province, other teachers also composed examining commissions in localities of their regions. It was the case of Professor Vicentina Adelaide de Vasconcellos who - along with her colleagues Francisco de Paula Xavier de Toledo, a professor of Latinity and French language and Francisco Luiz de Abreu Medeiros, teacher of the second chair of first letters, all of Sorocaba - examined and fully approved Zeferina de Vasconcellos as an interim teacher of Capivary (Correio Paulistano, 1858, p. 2).

In the province of São Paulo, besides Benedita da Trindade and Vicentina Vasconcellos, there was another examining female teacher during the period. This is Anna Antonia da Costa Guimarães, who was appointed professor of first letters in 1853 for the chair of Santa Ifigênia and was designated “[…] to serve as examiner in domestic gifts […]” in 1854 (Rodrigues 1962, p. 83). In a series of correspondence published in the newspaper O Publicador Paulistano, between October 1858 and August 1859, an indignant reader from the city of Guarulhos who signed as ‘a father of family’ denounced a case of favoring the candidate ‘D. Catharina’ to the teaching profession of the locality, according to the author, for being the wife of an influential figure. The indignant reader considered that the candidate did a ‘scandalous examination’ not being able to recite the ‘Our Father’, nor to write the numbers and read a writing. Regarding the examination on gifts, he reported that “Mrs. D. Anna Antonia, picking her up to a secret room to examine her in domestic gifts, later testified that she had not taken any and that the service had already come done from home” (O Publicador Paulistano, 1859, p. 4). The complaint confirms the performance of Anna Antonia da Costa Guimarães as an examiner in gifts and that this part of the contest was not public but held in a more secluded manner. In addition, the case indicates that even in the cases of entry through contest, there was the practice of favoring.

The recruitment of teachers as selectors in the contests increased the participation of women in spaces of greater visibility in public education. It was also a device of hierarchy within the teaching profession. Male and female teachers were summoned by the provincial government and many responded affirmatively to the calls participating in these processes. The admission of female teachers in the exercise of this function - both composing almost absolutely male committees (reading, writing, arithmetic and Christian doctrine examinations - common subjects in the male and female classes), as well as in the evaluation of the candidates in the knowledges considered feminine (domestic gifts) projected them into public life and engendered them in the hierarchy as agents of the provincial administration - strategic pieces in the construction of the Imperial State (Villela, 2002; Mattos, 2004).

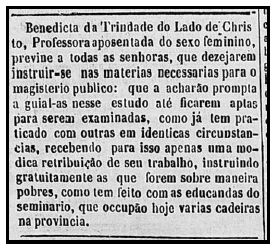

When retiring, the teacher Benedita da Trindade did not abandon the teaching. After offering to teach at the Seminário de Educandas, still in 1859, and not taking the chair, she published an unusual advertisement in Correio Paulistano.

The announcement evidences that the teacher did not end life in the teaching work with the retirement. On the contrary, she continued offering to instruct ladies in the necessary subjects for the examinations to enter the teaching profession, that is, she prepared women candidates for public examinations, being arranged to work free for the very poor. She thus placed herself as an educational agent and disputed a space in the formation of the new female teaching generations. As a way of conferring legitimacy and prestige on her own trajectory, she pointed out that some former students (who had graduated from the Seminário de Educandas), who were her disciples, had already become teachers. The announcement is a very important thread, because it demonstrates that the history of female teaching practice and teacher training have many other facets besides that experienced within normal schools, two decades later55, so highlighted by historiography. We did not find the advertisement repeated in other editions of Correio Paulistano - a practice that was quite common in the 19th century periodicals. Thus, it is not possible to know if she would have continued the practice without advertising in newspapers, given up on the idea or suffered some kind of embarrassment by the Inspection of Public Instruction. The questions remain ... Benedita da Trindade and her possible students would have woven solidary relations and made effective the transmission of the teaching profession as an ‘immaterial inheritance’ (Levi, 2000) among women from the lower classes in the middle of the 19th century? The concept of Giovani Levi (2000) was formulated in the research on the trajectory of an Italian priest in the 18th century, proposing a reading of the family as an enlarged nucleus that uses cooperation, solidarity, exchange of favors and reciprocities with other groups that contribute directly with its survival and strengthening. The announcement of a retired teacher volunteering to form new aspirants, the only one of the genre so far, is a remnant of practices engendered by the subjects themselves on the margins of official action.

Between the announcement of 1859 and the news of her death in 1875, we located only two records about the teacher in the sources, both referring to the retirement. The first in February 1860, the year after the granting of retirement, determined that Benedita da Trindade would receive the full wages and the allowance provided for by the Budget Law (report of the Inspector of Public Instruction, attached to that of the president of the province of S. Paulo, 1860). The second is the page of Almanak da Província de São Paulo (1873) which brings the pension values of retired teachers. The value of Benedita’s pension was 920$000 a year, the highest value among female teachers. Among men, the highest value was the pension of the teacher of São Sebastião, who received 1:099$320 per year. The values of the pensions of these two were significantly higher than the others56 - and even the pension of the teacher of the Normal School. Therefore, the news about the death of the teacher in such precarious conditions causes strangeness. One hypothesis is that teacher Benedita da Trindade has not received her retirement in the final period of her life, perhaps because she was physically unable to meet bureaucratic demands for receipt.

We consider that a gifted tradition conformed the invention of the female public teaching profession without canceling literate resistances. Benedita da Trindade was the main exponent of the teachers who said no to legislation, to the teaching of domestic gifts. The teacher’s refusal, a sneak attack, occurred during the Regencial period, when there was a tendency of the imperial government to centralize power in the Court.

The Thompsonian perspective on the process of constitution of the English working class, of its ‘making itself’, allowed an approach of the feminine teaching profession as a group of workers in formation process (Thompson, 2002, 2004a, 2004b). We emphasize that these teachers were forming. The girls’ public schools, created after 1828, were spaces in which school cultures were set up in relation to women’s cultures, marked by gender and class belongings. They were hybrid places permeated by aspects that were between the public and the private, the allowed and the interdict, between the will of the subjects and what the material conditions of life limited and made possible.

Finishing the narrative, we consider that the preponderance of a gifted tradition in girls’ schools was one of the facets of the conformation of school culture to the social patterns of gender of the 19th century society. In the period, there was a process of expansion of female public schooling, whose daily construction, despite being the target of all kinds of conformations, was able to count on dissonant experiences, negotiations, contradictions and resistances.

REFERENCES

Algranti, L. M. (1992) Honradas e devotas: mulheres da colônia. Estudo sobre a condição feminina através dos conventos e recolhimentos do sudeste - 1750-1822 (Tese de doutorado). Faculdade de Filosofia Ciências Humanas e Letras. Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Almanak da Província de São Paulo. (1873). p. 84. [ Links ]

A Aurora Paulista. (1852, 25 de março). p. 1. [ Links ]

Brasil. (1824). Constituição política do Império. Recuperado de: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao24.htm. [ Links ]

Brasil. (1827). Lei geral da instrução pública de 15 de Outubro de 1827. Coleção de Leis do Império do Brasil, 1(pt. I), 71. [ Links ]

Brasil. (1828). Dá nova fórma ás Camaras Municipaes, marca suas attribuições, e o processo para a sua eleição, e dos Juizes de Paz.Coleção de Leis do Império do Brasil. Recuperado de: http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/lei_sn/1824-1899/lei-38281-1-outubro-1828-566368-publicacaooriginal-89945-pl.html [ Links ]

Brasil. Câmara dos Deputados. (1854). Decreto nº 1.331-A, de 17 de fevereiro de 1854. Approva o Regulamento para a reforma do ensino primario e secundario do Municipio da Côrte. Coleção de Leis do Império do Brasil, 1, pt 1, 45. [ Links ]

Carvalho, P. (2015). De uma "cientificidade difusa": o coronel e as práticas colecionistas do Museu Sertório na São Paulo em fins do século XIX. Anais do Museu Paulista: História e Cultura Material, 23(2), 189-210.Recuperado de: https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-02672015v23n0207 [ Links ]

Certeau, M. D. (1994). A invenção do cotidiano:artes de fazer. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Chamon, C. S. (2005). Maria Guilhermina Loureiro de Andrade:a trajetória profissional de uma educadora (1869/1913)(Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano. (1858,13 de dezembro). p. 2. [ Links ]

Correio Paulistano . (1859, 19 de janeiro). p.3. [ Links ]

Dias, M. O. L. S. (1995). Quotidiano e poder em São Paulo no século XIX. São Paulo, SP: Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Duarte, A. L. (2010). “Lei, justiça e direito: algumas sugestões de leitura da obra de E. P. Thompson”. Revista Sociologia Política, Curitiba, 18 (36), 175-186. [ Links ]

Faria Filho, L. M. (1998). A legislação escolar como fonte para a História da Educação: uma tentativa de interpretação. In Educação, modernidade e civilização (p. 89-125). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Fonseca, T. N. de L. (2007). Um mestre na Capitania. Revista do Arquivo Público Mineiro, XLIII, 170-183. [ Links ]

Gondra, J. G.,&. Schueler, A. F. (2008). Educação, poder e sociedade no império brasileiro. São Paulo, SP: Cortez. [ Links ]

Gouvêa, M. C. S. (2003). “Os fios de Penélope: a mulher e a educação feminina no século XIX”. In Anais da 26ª Reunião da Anped (p. 1-12). Poços de Caldas, MG. [ Links ]

O governista. (1851,09 de abril). p.2. [ Links ]

Hilsdorf, M. L. S. (1997). Mestra Benedita ensina primeiras letras em São Paulo. São Paulo, SP: Plêiade. [ Links ]

Hilsdorf, M. L. S. (2003). História da educação brasileira: leituras. São Paulo, SP: Pioneira Thomson. [ Links ]

Hilsdorf, M. L. S. (2010). Tão longe, tão perto. As meninas do Seminário. In M.Stephanou, M. H. C. Bastos. Histórias e memórias da educação no Brasil (Vol. II: Século XIX, p. 52-67). Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes . [ Links ]

Hirata, A. (2011). Conselheiro Ribas: o sistematizador do direito civil brasileiro. Recuperado de: http://www.cartaforense.com.br/conteudo/colunas/conselheiro-ribas-o-sistematizador-do-direito-civil-brasileiro/7568 [ Links ]

Levi, G. (2000). Herança imaterial: trajetória de um exorcista no Piemonte no século XVII. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira. [ Links ]

Martins, A. E. (2003). São Paulo Antigo (Vol. II). São Paulo, SP: Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Mattos, I. R. (2004). O tempo saquarema. São Paulo, SP: Hucitec. [ Links ]

Monarcha, C. (1999). Escola normal da praça: o lado noturno das luzes. Campinas, SP: Unicamp. [ Links ]

Moraes Silva, A. D. (1813). Diccionario da língua portugueza recopilado dos vocabularios impressos ate agora, e nesta segunda edição novamente emendado e muito acrescentado, por Antonio de Moraes Silva (Vol. 2, 2a ed.).Lisboa. PT: [ Links ]

Muller, D. P. (1923). Ensaio d'un quadro estatístico da Província de São Paulo. São Paulo, SP. Reedição Litteral Secção de Obras d' "O Estado de São Paulo". [ Links ]

Munhoz, F. G. (2018). Invenção do magistério público feminino paulista: Mestra Benedita da Trindade do Lado de Cristo na trama de experiências docentes (1820-1860) (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Muniz, D. C. G. (2003). Um toque de gênero: história e educação em Minas Gerais (1835-1892). Brasília, DF: UnB, Finatec. [ Links ]

Nascimento, C. V. (2011). Caminhos da docência: trajetórias de mulheres professoras em Sabará - Minas Gerais (1830-1904) (Tese de Doutorado). Faculdade de Educação. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte . [ Links ]

Nota de falecimento de Benedicta da Trindade do Lado de Christo. (1875, 12 de outubro). Correio Paulistano . p. 3. [ Links ]

Ofício da Câmara ao Presidente da Província. (1838, 23 de julho). Registro Geral da Câmara de São Paulo, 28, 133. [ Links ]

Ofício de Benedita Trindade do Lado de Christo.(1833a, 05 de fevereiro). APESP, IP. [ Links ]

Ofício de Benedita Tridade do Lado de Cristo. (1833b, 13 de maio). APESP. [ Links ]

Ofício de Eliziária Cezília Espínola. (1829, 03 de setembro). APESP, OD. [ Links ]

Ofício de José Ignacio Silveira da Mota dirigido ao presidente da Câmara. (1835, 16 de março). APESP, IP. [ Links ]

Ofício da professora pública de primeiras letras, Mafalda Virgínia das Dores. (1857, 18 de maio). APESP, IP. [ Links ]

Ofício do Inspetor de Sorocaba ao presidente da Província. (1854, 19 de maio). APESP, IP. [ Links ]

Oliveira, V. de B. M. (2008). “O relacionamento entre a província de São Paulo e o governo Imperial: economia e política em meio ao embate entre centralização e descentralização (1835 - 1850)”. In Anais do 19º Encontro Regional de História: Poder, Violência e Exclusão. São Paulo. [ Links ]

O Novo Farol Paulistano. (1832, 30 de novembro). p. 1. [ Links ]

Pais, L. C. (2010). “Traços históricos do ensino da Aritmética nas últimas décadas do século XIX: livros didáticos escritos por José Theodoro de Souza Lobo”.Revista Brasileira de História da Matemática, 10 (20), 127-146. [ Links ]

Paulo, M. A. R.; Warde, M. J. (2015). “A estrutura administrativo-burocrática da instrução pública paulista instituída pelo Regulamento de 08 de novembro de 1851”. Cadernos de História da Educação, 14, 279-300. [ Links ]

Perrot, M. (1995). “Escrever uma história das mulheres: relato de uma experiência”.Cadernos Pagu, 4, 9-28. [ Links ]

Perrot, M. (2007). Minha história das mulheres. São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

O Publicador Paulistano. (1858, 20 de março). p.3. [ Links ]

O Publicador Paulistano. (1859, 06 de agosto). p.4. [ Links ]

Relação de educandas anexa ao relatório do Presidente de Província. (1840). [ Links ]

Regulamento provincial de 26 de março de 1832. (1832, 30 de novembro). O Novo Farol Paulistano. p. 1. [ Links ]

Relatório do Inspetor da Instrução Pública, anexo ao do Presidente da Província de S. Paulo. (1860). [ Links ]

Rodrigues, L. M. P. (1962). A instrução feminina em São Paulo. São Paulo, SP: Escolas Profissionais Salesianas. [ Links ]

Sá, C. M., Faria Filho, L. M., Lopes, E. M. T., Jinzenji, M. Y., Rosa, W. M., Nascimento, C. V., & Macedo, E. F. P. (2005). A história da feminização do magistério no Brasil: balanço e perspectivas de pesquisa. In A. M. C. Peixoto & M. Passos (Org.), A escola e seus atores - educação e profissão docente (p. 53-87). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica . [ Links ]

Sessão da Assembleia Constituinte. (1823, 11 de agosto). p. 55-56. [ Links ]

Sant'anna, T. F. (2010).Gênero, história e educação(Tese de Doutorado). Universidade de Brasília, Brasília. [ Links ]

São Paulo. (Estado). Assembléia Legislativa de São Paulo. (1846). Lei Provincial nº 34, de 16 de março de 1846. São Paulo, SP. [ Links ]

Silva, A. M. P. (2007). Processos de construção das práticas de escolarização em Pernambuco, em fins do século XVIII e primeira metade do século XIX. Recife, PE: Editora Universitária UFPE. [ Links ]

Thompson, E. P. (1998). Costume, lei e direito comum. In Costumes em comum:estudos sobre a cultura popular tradicional (p. 86-149). São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Tilly, L. A. (1994), Gênero, história das mulheres e história social. Cadernos Pagu , (3), 29-62. [ Links ]

Thompson, E. P. (1998). Costumes em comum. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras . [ Links ]

Thompson, E. P. (2004a). A formação da classe operária inglesa: a árvore da liberdade (Vol. 1). Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2004a. [ Links ]

Thompson, E. P. (2004b). A formação da classe operária inglesa: a maldiçao de Adão (Vol. 2). Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra , 2004b, vol.2. [ Links ]

Thompson, E. P. (2002). A formação da classe operária inglesa: a força dos trabalhadores (Vol. 3). Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra . [ Links ]

Senhores e caçadores. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra , 1987. [ Links ]

Veiga, C. G. (2007). História da educação. São Paulo, SP: Ática. [ Links ]

Villela, H. de O. S. (2002). Da palmatória à lanterna mágica: a escola normal da província do Rio de Janeiro entre o artesanato e a formação profissional (1868-1876) (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Villela, H. O. S. (2003). O mestre escola e a professora. In E. M. T. Lopes, L. M. Faria Filho& C. G. Veiga (Orgs.), 500 anos de educação no Brasil (p. ?-?). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica . [ Links ]

Vincent, G., Lahire, B., & Thin, D. (2001). Sobre a história e a teoria da forma escolar. Educação em Revista, (33), 7-47. Dossiê: Trabalho e Educação. [ Links ]

29She may have had other children, not located in the research sources. However, the memorialists refer to the three siblings: Benedita, Leocádia and Jesuíno (Father Colchete).

30Maria Leocádia do Sacramento was director of the ‘Seminário de Educandas’. According to Antonio Egydio Martins (2003), this occurred in the period from 1830 to 1859, she died in São Paulo in May 1899 at age 93 (Martins, 2003). In our investigation, we identified 1831 as the year of entry and 1858 as the year of exit, and the retirement was granted in 1859. We also located the baptismal record of Maria, daughter of Anna Buenno and unknown father, 1795 and, thus, she would be 104 years old in 1899.

31We did not locate Jesuino’s baptismal record. We know that he was the brother of Benedita and Maria Leocádia through Antonio Egydio Martins, who also reported that he served as janitor and sacristan of the “Igreja do Senhor Bom Jesus do Colégio” - the current ‘Pátio do Colégio’ (the church is currently called ‘São José de Anchieta e o beato Antônio de Categeró’), appointed by the 1870 Ordinance and who “[…] for many years served as singer chaplain for the Sé Cathedral and as sacristan of the São Pedro Church” (Martins, 2003, p. 307). The author did not specify the years in which Father Jesuíno held the post of singer chaplain of the Cathedral.

33In 19th century Brazil, codes of moral conduct classified, hierarchized and distinguished subjects by granting or denying access and imposing interdictions (Algranti, 1992).

34In the thesis (Munhoz, 2018) entitled Invenção do magistério público feminino paulista: Mestra Benedita da Trindade do Lado de Cristo na trama de experiências docentes (1820-1860) other aspects and questions that perpassed the constitution of the feminine teaching were problematized. such as wages, the transmission of teaching among women, among others.

35We highlight some studies: Villela (2003), Muniz (2003), Sá et al. (2005), Chamon (2005), Sant’Anna (2010), Nascimento (2011), Munhoz (2018).

36According to Thaís N. Fonseca (2007, p.172), “[…] the existence of royal teachers was made possible by the reform carried out in the reign of D. José I by the Marquis of Pombal”. In a first stage, held in 1759, it was eliminated the “[…] control of the Society of Jesus over education, by its expulsion from all Portuguese territories”. Their schools were closed and their teaching methods and materials, forbidden. Other methods and materials were defined and “[…] free, royal, Latin, Greek grammar and rhetorical classes […]” were created. In 1772, the second stage was held “[…] with a more complete reform of the minor studies […]”, in which were created free royal classes of reading, writing and counting of the State; whose maintenance came from the “[…] literary subsidy […]”, imposed especially for the provision of materials and payment of teachers’ salaries.

37Several studies on the history of mathematics teaching in the Empire mention the general law of 1827 (Pais, 2010), recording the expansion of mathematics contents in primary education, and the boys are taught the four operations of arithmetic, broken numbers practice, decimals, proportions, and general notions of geometry. As this law provided for a restriction on the teaching of girls, these same researches - whose scope of analysis is the teaching of mathematics - end up slipping in the theme of the teaching of domestic gifts by explaining that the general law restricted the teaching of mathematics for girls to four operations, in addition to teaching domestic gifts.

38Women acted dynamically in other public spaces, such as the streets of the city, inserted in the world of work as washerwomen, farmers, grocers, candy confectioners, midwives and other crafts. The iconsphere of the “[…] feminine closure in the domestic space […]” is contrasted with “[…] a complex framework of differentiated social positions and functions […]” that gives “[…] visibility to the multiplicity of experiences of the feminine in the period” (Gouvêa, 2003, p. 5). In the thesis that gave rise to the present study, we outline the contours of the world of women’s work, in which we highlight the various possibilities of being a woman who populated the experiences in the nineteenth century São Paulo, with the profound social, gender and racial inequalities of a slave country (Munhoz, 2018).

39Doctoral thesis defended in 1972 at the Faculty of Philosophy of Letters and Human Sciences of USP.

40It was constituted by Manoel Jacintho Nogueira da Gama, Martim Francisco Ribeiro de Andrada, Father Belchior Pinheiro de Oliveira, Antônio Gonçalves Gomide and Antonio Rodrigues Velloso de Oliveira (Rodrigues, 1962).

41The Constituent Assembly was dissolved by Imperial decree of November 12, 1823. On March 25, 1824, Pedro I granted a Constitution that established a monarchical, hereditary, constitutional, representative government and the Empire as the “[…] political association of all the Brazilian citizens […]”, being considered citizens those ‘born in Brazil’, whether naïve or freed, and also those born in Portugal or in their possessions residing in Brazil “[…] at the time when independence was proclaimed” (Brasil, 1824).

42Hereafter, the acronym APESP for the Public Archive of the State of São Paulo and IP for Public Instruction will be used.

43Eliziária Cezília Espínola was director of the Seminário de Educandas between 1825 and 1830 and was responsible for the care and education of the orphans who lived in it. Her father, Nicolau Batista de Freitas Espínola, was the director between 1825 and 1829, when he passed away. In the same year, Eliziária resigned. She died on May 27, 1878 (Martins, 2003).

44During the presidency of Lucas Monteiro de Barros, the Baron and Visconde de Congonhas do Campo were created: two seminaries for orphans (01 male and 01 female), the Public Library, the Botanical Garden, the House of Correction, reformed Lazareto and the Santa Casa com a Roda de expostos (Hilsdorf, 2010).

46In the manuscript, the teacher wrote ‘law of November 15, 1827’, but the teacher made a mistake, because the law is October 15, 1827.

47The law of October 1, 1828, which “[…] gives new shape to the city councils, makes its attributions, and the process for its election, and of the justices of the peace […]” provided, in article 70, that “[…] Will be inspected the school of first letters, and education and destiny of the poor orphans, in whose number do the exposed enter; and when these settlements, and those of charity, that treats the art. 69, whether they are found by law or in fact entrusted in any city or life to other individual or collective authorities, the councils will always help when it is on their part for the prosperity and increase of the said establishments” (Brasil, 1828).

48This interpretation was suggested by the professor Adriana Maria Paulo da Silva in the occasion of the defense of her thesis.

49According to Carvalho (2015, p. 192-193), the Sociedade Sete de Setembro was “[…] a private charitable organization whose purpose was to educate orphan girls in order to prepare them for teaching or marriage” (See also Correio Paulistano, 1855).

51Some documents from the Public Archive of the State of São Paulo cited by Leda Rodrigues were not located and therefore Although the cases of collection and denunciations of the teachers in cases of absence of the teaching of the domestic articles prevailed, there were situations in which the schools were thought to leave aside the sewing and to concentrate on the teaching of reading, writing and arithmetic are cited indirectly.

52The term ‘opponent’ refers to the candidates who participated in the contests in order to compete for the positions of the public teaching profession. Adriana M. P. Silva (2007, p. 171-172) describes the contests informing that "[…] the candidates should publicly argue with each other with questions concerning the subject or the level desired, in a kind of combat; - if there is only one candidate [...] there would be an oral test to answer questions raised by them”. The contemporary dictionary of Antonio Moraes Silva (1813, p. 368) defines opponent as “[…] who intends the lens chair”.

54He graduated from the Faculty of Law of São Paulo in 1840, where he became professor, teaching classes in history, political economy, administrative law, public law, civil law and ecclesiastical law. He was provincial deputy in several legislatures (Hirata, 2011).

55In São Paulo, the Normal School was exclusively masculine between 1846, when it was created, until 1867, when it was suppressed. The Normal School was reopened in 1875. The masculine section operated in the rooms of the Attachment Course of the Law Academy. The feminine one was inaugurated in 1876 and it worked in the Seminário da Glória (Monarcha, 1999).

56After them, the largest pensions among the teachers of first letters were those of the teacher from Ubatuba, Manoel Ignacio da Fonseca, who received 600$000, and the teachers of Itu, Rita Candida Pacheco Freire and Jacareí, Maria Laudelina de Moraes, who received 500$000 a year. The Normal School teacher received 800$000 of retirement and the Director of the Seminário de Educandas, Leocádia Maria do Sacramento (sister of Benedita da Trindade), received 460$000 annually.

Received: November 13, 2017; Accepted: August 09, 2018

texto en

texto en