Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1519-5902versão On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.20 Maringá 2020 Epub 01-Ago-2020

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e118

Original article

Children’s Literature editing in Fortaleza. regional variations and cultural mediations

1Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brasil.

This article analyzes, from the perspective of Pierre Bourdieu’s sociology, the processes involving the editing and distribution of children’s books in the city of Fortaleza, located in the Northeast of Brazil. To this end, it focuses on the practices of agents and institutions that work toward establishing a relatively autonomous editorial space. It chose, as empirical material, Edições Demócrito Rocha and Editora Dummar, companies linked to Grupo de Comunicação O Povo. The hypothesis to be tested is that the uniqueness of a regional space is paradoxically achieved through heteronomy. From this perspective, the state’s role in editorial production is fundamental, from the classification of themes encompassing popular culture, tradition and heritage, to the purchase of books, and public notices intended for the sector. This system identifies the promotion of local culture as a means to ‘assemble the pieces’ of the Brazilian literary nation. The space for children’s book editing in Fortaleza thus constitutes a dependent and peripheral subfield of production within a national space, also dependent and peripheral in relation to transnational linguistic spaces.

Keywords: book and edition history; children's literary space; autonomy; heteronomy; children's literature in Fortaleza

Este artigo analisa, na perspectiva da sociologia de Pierre Bourdieu, os processos de edição e circulação de livros infantis na cidade de Fortaleza, situada no nordeste do Brasil. Para tanto, enfoca as práticas de agentes e instituições que atuam na constituição de um espaço editorial relativamente autônomo. Como material empírico, elege as Edições Demócrito Rocha e a Editora Dummar, empresas vinculadas ao Grupo de Comunicação O Povo. A hipótese testada é a de que a singularidade de um espaço regional é paradoxalmente conquistada por meio da heteronomia. Nessa perspectiva, é fundamental a atuação do Estado na produção editorial, desde a classificação dos temas da cultura popular, da tradição e do patrimônio, até a compra de livros e editais destinados ao setor. Esse sistema identifica a promoção da cultura local como um modo de ‘juntar as partes’ da nação literária brasileira. O espaço de edição de livros infantis em Fortaleza constitui-se, desse modo, um subcampo de produção dependente e periférico dentro de um espaço nacional também dependente e periférico com relação aos espaços linguísticos transnacionais.

Palavras-chave: história do livro e da edição; espaço literário infantil; autonomia; heteronomia; literatura infantil em Fortaleza

Este artículo analiza, desde la perspectiva de sociología de Pierre Bourdieu, los procesos de edición y circulación de libros infantiles en la ciudad de Fortaleza, ubicada en el noreste de Brasil. La investigación se centra en las prácticas de los agentes e instituciones que actúan para constituir un espacio editorial relativamente autónomo. Con material empírico, elige las ediciones de Demócrito Rocha y Editora Dummar, empresas vinculadas al “Grupo de Comunicação O Povo”. La hipótesis probada es que la singularidad de un espacio regional se conquista paradójicamente a través de la heteronomía. En esta perspectiva, la acción del Estado es fundamental en la producción editorial, desde la clasificación de los temas de cultura popular, tradición y patrimonio hasta la compra de libros y avisos públicos destinados al sector. Este sistema identifica la promoción de la cultura local como una forma de 'unir partes' de la nación literaria brasileña. El espacio para la edición de libros infantiles en Fortaleza se constituyó, por lo tanto, en un subcampo de producción dependiente y periférica dentro de un espacio nacional también dependiente y periféricos con respecto a los espacios lingüísticos transaccionales.

Palabras clave: historia de libros y ediciones; espacio literario infantil; heteronomía; autonomía; literatura infantil en Fortaleza

Introduction

To analyze Edições Demócrito Rocha (EDR) and Editora Dummar (ED) - the former, a non-profit publisher belonging to Demócrito Rocha Foundation [Fundação Demócrito Rocha] (FDR); the latter, a commercial publisher belonging to Grupo de Comunicação O Povo, whose journalistic institution is one of the oldest in Ceará -, we worked with the publishers’ digital catalogs, with the book “Rachel: o mundo por escrito” [Rachel: The World in Writing], with the construction of a map in the Google Maps platform, in addition to documental sources made up of files and news stories available in libraries, collections or also online. From a thematic point of view, the titles published by both publishing houses address aspects of Ceará’s popular culture (literature, heritage, local personalities, legends and tradition) and are relevant to the early structuring of the editorial space linked to school demand, which, by the way, guides their production. Popular culture themes, for instance, are highlighted in government procurement notices and in curriculum parameters. As a result, the strategy of the agents is both to meet the demand of the state and schools through curricular parameters, and to contribute to the legitimation of local culture before national culture. To interpret the conditions of book production and distribution, we describe the journeys of writers, illustrators, editors and booksellers, protagonists in the mediations of the analyzed practice space.9 10 11 12

The study of the relations between agents put us before a double scale of observation, national and local, redefining the place of the periphery in the history of Brazilian children’s literary editing. The scales reflect the flow of practices in institutions, their links to the notions of a Ceará identity and a national identity, which proved to be of paramount importance for the conception of space. This delimitation is motivated by the idea that the relations between cultural products and social spaces are built in different ways in each case. Or rather, the set of practices, strategies and results that make up the symbolic system of the Brazilian social world produces singular meanings. The editorial production space, inspired by Pierre Bourdieu’s field theory (2013), allowed, above all, identifying the agents and their mediations; for this reason, it worked as a methodological tool.

In the formation of the Brazilian literary editing aimed at children and youths, a discourse in favor of promoting culture and creating readers is recurring (Leão, 2012). In Fortaleza, this constant, in addition to being one of the main objectives that guide editorial practices, also guides the school demand for production of books, be they of the teaching or literary sort. Our main goal is to show how folklore themes, legends, as well as characters and landscapes that refer to the hinterland and the sea, are at the base of the construction of what is collectively represented as Ceará culture. Thus, the logic of government demand − purchasing books for distribution and use in schools − ends up shaping the analyzed space. In the same way, we sought to show that the incipient specialization of producing and mediating agents also depends on the action of the state - because without the support of federal, state and municipal governments, it would be impossible to create literary fairs -, on the growth of the market and, consequently, on a future autonomy in relation to other national and transnational markets. We have come to the conclusion that, in Fortaleza, the children’s book editing space demarcates a singularity in comparison with other regions in Brazil, already renowned for their production and distribution of literary works, such as those from the cities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In other words, the singular mark in Fortaleza’s cultural history of books and printed matter is its dependence on the government. This autonomy in heteronomy is aimed at in the close relationship with the fields of political and economic power, in the low sales of the book sector, in the multiple roles taken on by editors, who work as writers, illustrators, and, in some cases, in autodidacticism practices as an authorial strategy.

Books in Fortaleza: Morphology of the Literary Space

In the 19th century, the increased distribution and, consequently, the popularization of children’s literature in Fortaleza were strongly impacted by the bookstore business. Livraria Oliveira and Libro-Papelaria Gualter were pioneering establishments in providing teaching and literary books for children and youths, with imported, translated and national titles. In addition to books and printed matter in general, cordel booklets also stood out in these shops, reproducing fairy tales with the adventures of kings, queens, nobles and maidens of European courts from centuries ago. Silva (2001) tells us about the offer of booklets, sold at low prices and in large quantities, as supporting elements to oral and visual readings addressed, preferably, to those who did not have direct access to written culture. Thus, traditional European stories, within the genres of fairy tales, poetry and biography of famous figures, marked Ceará’s popular imagination with the wide distribution of cordel booklets.

In 1870, booklets by Roberto do Diabo and João de Calais were a hit at Livraria Oliveira. At the same time that, in 1891, Libro-Papelaria Gualter was betting on books, more noble and sophisticated, with renown titles by Jules Verne, Countess of Ségur, Maria Amália Vaz de Carvalho and La Fontaine (Silva, 2001). This bookstore also had The Adventures of Robison Crusoe, by Defoe - translated by Professor Carlos Jansen, from Rio de Janeiro -, alongside D. Quixote and Gulliver’s Travels (Silva, 2001).

This small sample suggests that bookstores in Fortaleza operated as a commercial warehouse for Rio de Janeiro’s bookstores Garnier, Laemmert and Francisco Alves, which, in their turn, imported books directly from the European capitals Lisbon, Porto and Paris. Another effort to keep up with western modernity was carried out by advertisements published in the newspapers of the last decades of the century, which announced collections of illustrated books, such as “O carrapatinho” [The Little Trick], “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves”, “Puss in Boots”, “Margarida, a pastorinha” [Margarida, The Little Shepherd], “Bluebeard”, “Alladin and the Magic Lamp”, “The Little Glass Slipper” and “Sleeping Beauty”. Some newspapers, such as Pedro II, Constituição, Cearense and Libertador, would post lists of newly arrived books on the ships that docked in the port of Fortaleza.

At the other end of the printing circuit, and as the educational system developed, children were becoming a new audience for the book market in Fortaleza. Children’s literature works targeted the elite’s illustrated families and were written by authors with purchasing power to produce, edit and launch their own books. This trend is observed throughout the 20th century. Even today, many children’s book writers are educators who dedicate themselves to other genres and age groups. Illustrative of this reality is the journey of Artur Eduardo Benevides, a professor at the Federal University of Ceará, who published, in 1975, the book “O menino e o arco-íris” [The Boy and the Rainbow] (Fortaleza, 2005). Another milestone in children’s literature in Ceará, written by a novelist not specialized in the genre, is “O menino mágico” [The Magic Boy], by Rachel de Queiroz. Published in 1975, it won the Jabuti Prize for Children’s Literature. The writer also launched, in Rio de Janeiro, the books “Andira”, in 1992; “Cafute & Pena-de-Prata”, in 1996; “Xerimbabo”, in 2002; and “Memórias de menina” [A Girl’s Childhood Memories], in 2003.

In 1981, the Brazilian Rural Life Library project consolidates a partnership between the Federal University of Ceará and the Ministry of Education. The project proposed the editing and distribution of regional literary works to encourage reading in peripheral communities, which gave children’s literature in Ceará a little momentum (Fortaleza, 2005). To develop the project, it was necessary to map the culture, the vocabulary and the imagination of Ceará’s rural population. More than 50 titles were published by writers and professors. Collection works had pedagogical recommendations, with suggestions at the end of the books on their use in schools. It is interesting to note that the Brazilian Rural Life Library project provided opportunities for hiring illustrators and for composing an editorial team, signaling the steps toward the professionalization of the sector. Over the years, the budget invested by the federal government was gradually reduced, compromising the quality of publications and culminating in the cancellation of the project.

The implementation of the children’s literature discipline at the Federal University of Ceará’s School of Languages, in 1987, was another decisive moment in the formation of a space for children’s literature books in Fortaleza. The Federal University of Ceará was one of the first to integrate children’s literature as discipline into the curriculum of their undergraduate languages course. Professor Horácio Dídimo, PhD in Comparative Literature and author of books for children, was responsible for this endeavor. Dídimo wrote, among several works, “A cara dos algarismos” [The Face of the Numerals] and “As historinhas do Mestre Jabuti” [The Little Stories of Master Jabuti] (Fortaleza, 2005). Some of his books were published by Edições Demócrito Rocha. From then on, new names appeared, such as Helena Lutéscia, Elvira Drummond, Heitor Simões, Mino, Lauro Sérgio, Almir Mota, Klévisson Viana, Arlene Holanda and Socorro Acioli.

The books that bring Ceará as a scenario build a social representation of the northeastern culture, from the enchantment with the moonlight and the stars, to adventures set in the past as a form of historical knowledge. “A trama de Rachel: o mundo por escrito” [Rachel’s Story: The World in Writing], by Tércia Montenegro (2010), is built, amid oil lanterns and lamps, with elements typical of the state of Ceará, such as horseback riding under the sun, the star-painted sky, the religiosity of some characters, saraus (cultural events), family gatherings, and the stories told by grandmothers. The narrator invites the reader to visit the city of Quixadá, Sítio do Junco, Lagoa do Seixo, the city of Juazeiro do Norte, Serra de Baturité, or Guaramiranga, as well as, in Fortaleza, Praça do Ferreira, Café Globo and Sítio do Pici. Cuisine also finds representation in the narrative. Tapioca, couscous, cowpea, coconut and papaya jams and fruits share the plot with real characters from Ceará’s and Brazil’s literary history, such as Antônio Sales, Graça Aranha, José de Alencar and Father Cícero. The intertwining between the local and the national, the coast and the hinterland, reconstructs an imagined Ceará. Ties are formed around the feeling of belonging to a place and around the identification of symbols from the past.

In September 1976, the Department of Culture and Sports of Ceará’s government performed a diagnosis on cordel literature. The objective was to learn about the production conditions of this activity in order to provide subsidies for its preservation and to foster cordel literature in the state. Among the cities visited by the researchers were Juazeiro do Norte, Crato and Barbalha, important centers for booklet production and distribution in northeastern Brazil. Photographs, booklets and interviews with cordel masters, such as Patativa do Assaré and Manoel Caboclo, were collected. From this material, the first volume by Coleção Povo e Cultura was born, “Antologia da literatura de cordel” [Cordel Literature Anthology], published in 1978 (Oliveira, 2015). In January of the same year, the diagnostic project became a ‘disseminator’, with the purpose of stimulating research and the study of manifestations of popular literature in the Northeast. The diagnostic and dissemination projects helped in broadening discussions around popular literature, as they aimed to identify its production and distribution conditions, as well as its history and sociocultural importance.

In 2003, the Coordination for Policies on Books and Collections was created, within the scope of the State Plan for Culture. This division was responsible, in Fortaleza, for public policies related to books, reading and literature, as well as for the equipment of Governor Menezes Pimentel Public Library, Ceará State’s Public Archive, Juvenal Galeno House, and the Public Libraries State System. In 2004, another government initiative stands out, Law No. 13.549, of December 23, 2004, which institutes the state book policy (FLLLEC: Fórum de Literatura, Livro e Leitura do Estado do Ceará (Ceará State’s Literature, Book and Reading Forum), 2019). That same year, the State Council for Book and Reading in Ceará was also created, and the Ceará State’s Literature Forum was articulated, which, years later, had its name changed to Ceará State’s Literature, Book and Reading Forum.13

In 2004, the Department of Education developed the Literacy at the Right Age Program [Programa de Alfabetização na Idade Certa] (PAIC). By means of it, several axes were instituted, which aimed at improving education for children from public schools up to the fifth grade of elementary education. It includes the Children’s Literature and Reader Formation Axis, which has as one of its objectives to publish the Prose and Poetry PAIC Collection. For this collection to be produced, a selection process is carried out, through a public notice, to hire writers, illustrators, editorial coordinator and graphic designer. In addition, the publications have Ceará’s heritage and popular culture as theme. The program, however, is criticized by some local editors for the way it is conducted; they question not only the choice process and the literary quality of the authors14, but also the quality of the graphic material of the books and, mainly, the role of the state as a promoter of the local editing market. According to Júlia Barros, a cultural producer at the publishing house Casa da Prosa, the biggest problem with the Prose and Poetry PAIC Collection is that the state government fulfills the role of a publisher instead of contributing to stimulating the book production chain that already exists in the city. The selection process notice does not include publishing houses, only authors and illustrators15. Also according to Júlia Barros, the state should create a bidding process for publishers. Now, if there is a public notice aimed at new authors, the winner would need to hire a publisher to publish their book.

Moreover, Arlene Holanda, a writer and editor at IMEPH, says that the states of Minas Gerais and São Paulo purchase books from Ceará’s publishers through public notices - in addition to the governments of Belo Horizonte and São Paulo. In 2018, the city of Fortaleza launched a public notice for the procurement of literary, technical and supplementary educational material for libraries of public schools in the municipality. Everything leads us to believe that the symbolic and marketing aspects are aligned, within the space, in favor of the formation of not only children’s literature, but of a market for this type of literature.

The Children’s Books by Edições Demócrito Rocha and Editora Dummar

The young reader is confronted with a series of constraints and rules and, one way or another, is controlled by the adults involved in the production and distribution of children’s literature books (Leão, 2007), be they writers, editors, booksellers, teachers, or even caregivers, such as parents. The texts are written and published with the aim of controlling the child’s sense-making as to the world (Chartier, 1999, p. 7). This can be explained by the historian Roger Chartier (1999), who understands a book as an object whose goal has always been to apply an order of deciphering, of comprehension, or the order desired by the figure of an authority that requests it or allows it to be published. Thus, books are cultural goods whose forms guide the imposition of a meaning, of the uses that can be employed and of the appropriations that can be done by readers. The reception of the book has, however, the ability to invent, displace and transform its text. It is also the readers, in the role of recipients (as well as the individuals involved in the production of books: writers, editors, etc.), who are assigned the task of giving meaning to works through their devices and dispositions and who, through mental and affective schemes, decipher the culture and formation of social bonds in the communities in which they belong (Chartier, 1999). That is, the reader is affected by the work they read but, at the same time, has an effect on it as well, being appropriated and appropriating.

The literary production for children and social experiences, such as reading, are comprehended in models and collective norms that affirm themselves through social pacts (between author and work, author and reader, reader and work...) and develop in particular ways at every text and in every community of interpretation - which shape the universe of readers, whose relationship with the text stems from the union of skills, uses and codes of interest. The reader engages in an activity that is not restricted to the automatisms of conscience, to which producers impose cultural models. It is through reading, an oftentimes solitary action, that the child’s subjectivity is virtually invaded and, frequently, reaches an intimacy with the text that is not always achieved by adults, turning reading into a practice (Zilberman, 1987).

Reading practices bring into play the relationship between body and book, as well as the various possibilities of using writing and the categories that guarantee its apprehension, constituting new ways of producing sense. The uniqueness of the reader, under the circumstances in which the latter is found, is crossed by something that makes them similar to other individuals in the same community. Change is brought about through the specificity of reader communities, which, at different times, are not controlled according to the same principles. The fragmentation of such communities is the result of “[...] distinctions between classes, different learning processes, a longer or shorter schooling, a more or less secure mastery of written culture” (Lebrun, 1998, p. 92). Readers from other eras were affected by psychogenetic, formative functions, or even used reading as a tool for inculcating practices.

In order to find out about the functions of the books of a certain reader community or, in the case of this research, to understand the particularities of the works produced by the editorial space in Fortaleza, one needs to resort to its catalogs and works. To this end, three catalogs by Edições Demócrito Rocha are used, corresponding to 2013-2014, 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 (Children’s and youth catalog..., 2017a, 2017b, 2017c). The digital catalog is divided by level of education, from elementary school I to high school, and reading fluency, whose categorization is defined as beginner reader (from 6 and 7 years old), developing reader (from 8 and 9 years old), fluent reader (from 10 and 11 years old), and critical reader (from 12 and 13 years old) - standard classification adopted by most publishing houses that publish children’s books. The publisher complies with the National Curriculum Parameters [Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais] (PCNs) and has books in the following genres: prose, poetry, cordel, chronicle, picture book, comics, short story, novel and narrative. Their thematic contents deal with the environment, legends and adaptations, music and teaching materials, such as mathematics, history and geography. The regional theme addresses Ceará’s indigenous identity, landscapes and characters, mainly when it comes to the sea and the hinterland, drawing what we can refer to as the Ceará imagery.

The publisher’s catalog is a minimal unit of classifications of the book world that provides the researcher with a system of traces from which the individual’s interpretation can be expanded to the states of development of a market and the types of social ties that surround editing as a specific force in a power field (Sorá, 2010). The set of titles, authors, genres and collections are distributed hierarchically, from an order that refers to the classifying agent and the genesis of the latter’s practical reasons. This distribution is also a means that the agents find to form an identity and a world view, considering what should or should not be said about the company, which books should be read, which audience should read each work, etc. It can also be understood as a way of organizing the works by means of the intentions of the editors, in a defense of cultural promotion through the symbolic highlight of children’s book production. Publishers use the catalog as a strategy to access certain spaces and advertise the books produced, bringing them to private schools, which will choose the books that will be used as supplementary and worked on in the classroom, in addition to participating in public notices concerning federal, state and municipal programs - such as the Library at School National Program [Programa Nacional Biblioteca na Escola] (PNBE) and the National Textbook Program [Programa Nacional do Livro Didático] (PNLD).16

The discourse contained in them draws attention to innovations in the editorial segment and to educational needs, with the aim of contributing to the pedagogical practice in the classroom. Edições Demócrito Rocha stands as one of the most relevant publishing houses in the Northeast, offering subsidies to teachers and students by selecting books for the classroom and school libraries. There is a presentation for teachers, a section for a history textbook (“Construindo o Ceará: história” (Building Ceará: History)) and a geography textbook (“Construindo o Ceará: Geografia” (Building Ceará: Geography)), a section for children’s books, and another one for the main authors of the house, such as Horácio Dídimo, Tércia Montenegro and Socorro Acioli. The book “Fortaleza: a criança e a cidade” [Fortaleza: Children and the City] covers both school subjects (history and geography) and won the MEC National Award for Best Textbook in 2010. Through these publications, the publisher’s discourse is one of partnership with schools and teachers.

Children’s books are presented in a collection made up of works whose content dialogues with Ceará’s culture and imagery. Most authors and illustrators are from the Northeast, and one of the publisher’s goals is to stimulate curiosity, discoveries and the formation of readers. For EDR, it is important that the encounter between readers and books happens through authorship, illustrations and graphic design, boosting the formation of new readers.

In “É pra ler ou pra comer?” [Should I Read or Eat This?], the author Socorro Acioli (2012) tells children the story of the Spiritual Bakery. Three characters from Ceará’s culture are featured: the brothers Sânzio de Azevedo, professor of literature and specialist at Spiritual Bakery, and Miguel Ângelo de Azevedo (Nirez), who owns the Nirez Archive (one of the largest spaces for storing various documents about the history of Ceará), in addition to Rubens de Azevedo, an astronomer after whom the planetarium of the Dragão do Mar Center for Art and Culture is named. The book is adopted in private schools, is part of the collection of the Dolor Barreira Municipal Library, was awarded the honorable mention ‘Highly Recommended’ by the National Foundation for Children’s and Youth Books [Fundação Nacional do Livro Infantil e Juvenil] (FNLIJ) and was featured in the catalog of the Bologna Fair (2005). It also has a presentation by the writer and researcher Gilmar de Carvalho, and a letter from Socorro Acioli to readers. “A batalha de Jericoacoara” [The Jericoacoara Battle] is a book written by Daniel Adjafre (2009) and tells the story of three friends who return to the past after passing by Pedra Furada on windsurf boards. There they meet Portuguese soldiers and, together, defend the fort against French pirates. At the end of the book, there are instructions for teachers on how to use it in the classroom. In its turn, “Patativa do Assaré, o poeta passarinho” [Patativa do Assaré, The Bird Poet] is written by Fabiano Piúba, secretary of culture for the state of Ceará. The work is prefaced by the writer Gilmar de Carvalho and tells the story of Patativa do Assaré as poetry. At the end, there is a short biography about Patativa and a glossary of popular language. All books include a brief biography of their authors and illustrators. These data indicate that the publisher has an inclination for publications aimed at the teaching of Ceará and Northeastern culture in connection with the school demand, which uses the works as supplementary content in classrooms and libraries.

It is possible to perceive, within this perspective, that these works are aligned with a pedagogical and formative function, since it “[...] converts the artistic narrative into an artifact of immediate utility” (Souza, 2004, p. 82), that is, it turns the plot of the books into a history class about Ceará, when used in schools as a supplementary educational material. This is a different type of education compared to that seen in the republican period, with moralizing books, for it continues the formation of the Ceará identity - a method established by the concept of cearensidade through the literature produced in Ceará as of the 19th century.

Characters such as boat riders, cowboys, lacemakers and migrants are portrayed in prose and in poetry showing strength, courage and resignation in the face of the problems found in the hinterland and at sea. They are references of popular culture that, through cearensidade, expose the construction of a ‘mythology’ in which characters, landscapes, customs and cultural production elaborate a Ceará based on this set of factors (Júnior, 2003) and, thus, form and represent a ‘Ceará identity’ - likewise, figures such as writers, intellectuals and other personalities are also portrayed in an imagined Ceará in the literature.

The Book Protagonists: Regional Variations and Cultural Mediations

The overview presented above proves, in the space of Fortaleza, the close ties between the editing market and government actions. It is worth noting that, in Brazil, the creation of a market for elementary books equally depended on basic education. Thus, the children’s and youth books sector can be strengthened or weakened as programs and investments increase or decrease. This movement tends to create an unsafe tide crossed by editors and booksellers over the years.

The problem of lack of readers also harms this market. According to the study Reading Portraits of Brazil [Retratos da Leitura no Brasil], by the Pro-Book Institute, 14% of the population living in the Northeast are illiterate or have not attended school. In 2015, the number of readers - those who read at least one book in three months - stood at 51%, with 49% of non-readers. In 2011, the average number of books read per year in the Northeast dropped from 4.3 to 3.93 in 2015 (Retratos da leitura no Brasil, 2019). Also according to the survey, the age group of five to ten years old feels motivated to read, first, because they enjoy it (40%), and, second, as a school requirement (22%). The cover is the element of greatest influence (27%), followed by recommendations from teachers (18%). Another important fact is the influence of mothers on book reading (11%), followed by teachers (7%) and fathers (4%) - within the 33% who claimed to have had external influences.

In recent years, data such as these have guided public policies for the formation of readers. In Fortaleza, publishers develop projects with this same goal. The role of the editor, according to the executive of Edições Demócrito Rocha and of Editora Dummar, Regina Ribeiro ( Viana, 2019), is also to review concepts, dialogue with teachers and writers for the making of books, courses, debates and lectures, because there is a concern about forming readers and training teachers for this literary education to happen - based on the idea that readers are primarily formed in schools.

The Demócrito Rocha Foundation develops several courses, including one about reading mediators. This course aims to promote the engagement of teachers by offering fascicles and tests, in addition to a certificate at the end. Casa da Prosa carries out a storytelling project in schools; and IMEPH has a number of projects to encourage reading and literacy, such as Learning by Building, for early childhood education, and other ones aimed at the Literacy at the Right Age Program, the Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous Brazil Project, and On the Waves of Reading. Most of them come with book kits for students and teachers. Thus, there is the development of a space for children’s literature in Ceará.

It is necessary to understand that the social space tends to present itself as a physical space in the form of a certain set of distribution of agents and properties. As a consequence, all proposed differences in relation to the physical space are contained in the reified social space (or appropriate physical space), defined by the correspondence of a certain order of joint existence between agents and properties. In this way, the place and the site taken by an agent in the appropriate physical space form the indicators of their position in the social space. That is, the social space is contained, at the same time, in the objectivity of spatial structures and objective structures, which are the product of the incorporation of habitus, practices, capitals and dispositions (Bourdieu, 2013).

From the perspective of the field theory by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, the social cosmos is composed of an arrangement of social microcosms, relatively autonomous, in which the spaces of objective relations are the place of a logic and a specific need of the relations that manage the other fields (Lahire, 2017). The field is the microcosm that is within the macrocosm, consisting of the global social space (national or international). For every field, there is a game and specific rules, in which social interests are not reduced to other games or other fields. Thus, the field is seen as a system or a space structured by the positions that the various agents take in this field. The practices and strategies of agents can only become comprehensible if they are related to the positions of each agent within the field. And since every space is a space of disputes, a competition between the agents and the positions that they take comes into play, with the purpose of appropriating the monopoly of the specific capital of the field, or redefining that capital, which is distributed unevenly. Because of this, a hierarchy is established between the dominant and dominated parties. This unequal distribution of capital establishes the structure of the field, defining it by the state of a relation of forces (agents and institutions) in a continuous dispute within the field. Fighting against each other, the agents also have an interest in the existence of the field, which helps in maintaining an ‘objective complicity’ that goes beyond the fights that make them oppose each other. The field also has a relative autonomy, in which the disputes that develop inside have their own logic, even though the consequence of fights external to the field affect the result of internal force relations (Lahire, 2017). Each field has a corresponding habitus, in which only the agents and institutions that incorporate this habitus that is proper to the field will have conditions to enter the game dispute and believe in its importance.

For Lahire (2017), Bourdieu’s model is insensitive to other crucial differences that may designate other ‘fields’, such as the degree of professionalization and stabilization of the actors in the field. In view of this, it is possible to understand the ‘game’ as a ‘secondary field’, or a subfield, where remuneration, institutionalization and professionalization are precarious (Lahire, 2017).

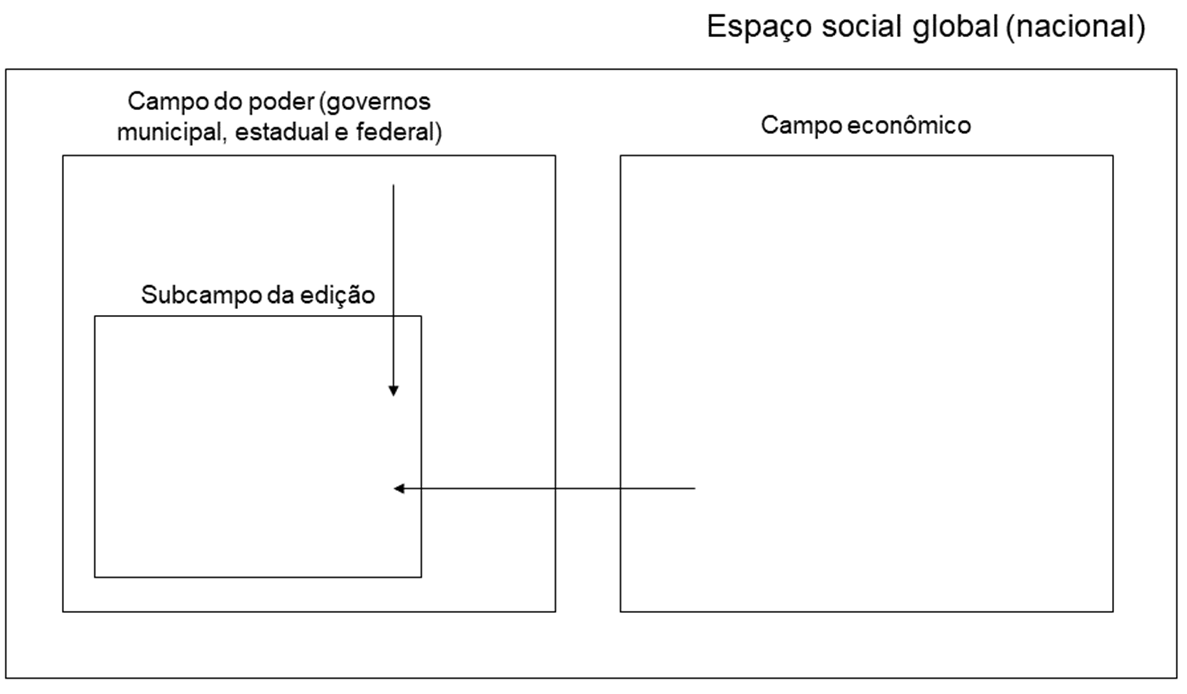

This set of concepts with which we have constituted the research approach allows us to understand the editing space for children’s books in Fortaleza as a subfield linked to the state’s power field. The (national) global social space is a macrocosm in which the power field, as a microcosm, is contained, ruling its forces, habitus and strategies, formulating practices that have a direct influence on the construction and development of its non-autonomous subfields, including that one where children’s literature is produced and distributed around the city. Competition fights take place within the subfield in the form of negotiations, confrontation of ideas and positions, as in the case of the agents who participate in the production of PAIC’s children’s book collection and those who are vehemently against the type of production that is done by the state of Ceará, without specific public notices for hiring publishers or purchasing books - which denotes an opposition in the field. In addition to the external fights in relation to central and peripheral publishers that are formed in the space, such as the relationship between São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, states that dominate the country’s editorial production as hegemonic centers, with Ceará being seen as a peripheral producer. There are also those agents who stand between the power field and the editing subfield; for instance, the secretary of culture for the state of Ceará, Fabiano dos Santos Piúba, who writes children’s books, actively works at the Biennial Book Fair and in other projects that involve matters related to books, reading and literature in both Ceará and Brazil.

As shown in Figure 1, the social interests of the agents who act in this subfield are subject to the interests of the state (as a power field) and of the market (linked to the economic field). Even though the agents have a relative autonomy with regard to their decisions on what is worth publishing or not, they are directly influenced by fights and competitions in upper fields. The political and economic powers possess, respectively, the monopoly of cultural capital and economic capital.

Figure 1 Explanation of the development of a global social space that encompasses both the power and economic fields, among several others, and brings the ‘editing in Ceará’ subfield inside the power field. The subfield also influences its upper fields, but the intention is to evidence the action of the fields on the subfield.

Source: The authors.

Edições Demócrito Rocha and Editora Dummar, being directly and indirectly linked to a private initiative company, even though EDR is tied to a non-profit company, which has its own legitimation body (the newspaper O Povo) and some economic capital, do not depend as much as other publishers on government funding. Even so, they follow the rules imposed by the dominant fields, such as the National Common Curricular Base (when writing about themes around heritage, tradition and popular culture) and the market game imposed by the economic field.

The state articulates, organizes and regulates editorial markets, formulating the operationalization of policies that condition editorial practices. This is why editors organize themselves in councils, associations and other groups to articulate and negotiate state decisions, seeking to reconcile interests (Muniz Jr., 2016). In both governmental and associative spheres, national statistics on book making and consumption are produced in order to render editorial markets intelligible. The national identity lays the groundwork for the production and distribution of works in territories other than those where the agents are from or act in, as well as in markets abroad.

It is worth noting that the globalization of culture redefines the meaning of tradition. Firstly, as permanence of a past and of a form of social organization that opposes to the modernization of societies; secondly, as a way of structuring social life, manifesting itself through electronic objects, “[...] its rapid conception of time, and of a ‘detached’ space” (Ortiz, 1994, p. 213, our emphasis). This second conception is a modern tradition that involves a popular-international memory, in which the elements that compose it can be recycled at any time - such as cordel and its adaptations. The past mixes with the present, determining new ways of being and conceiving the world - an identity-culture.

In this sense, modernity is not just a way of being, a cultural expression that translates into and takes root in a specific social organization. It is also ideology. A set of values that hierarchize individuals, hiding the differences-inequalities of a modernity that aspires to be global (Ortiz, 1994, p. 215).

The global then takes a stand against the local and the national. The uniqueness intended by that which is identified as national is pushed aside to make room for the global, since, for this concept, distinction is what matters. Thus, the national takes on some qualities from the local, making diversity and authenticity essential characteristics. It is when the identity of the peoples presents itself, proving to be different from the outside (Ortiz, 2000, p. 55).

To refer to the local is to imagine a restricted and delimited space where the events of a group unfold. The local is mistaken, due to the territorial outline of the habits of that group, for what surrounds the individuals and what is present in their lives, giving the idea of familiarity. The national covers a wide space, though physically determined. The idea of historicity is added to the national, being molded according to the interests of its institutions, games, views and present-building policies, in a process that takes a space that is not only geographic, but built from (and because of) collective representation. The national and the local are not opposed. In fact, they form a cohesive unit. This uniqueness is what imposes the national to the local, through the existence of a national culture that is updated in different ways in different contexts - the state, the market, linguistic unification, for example, are instances that dictate the national space (Ortiz, 2000).

As previously seen, the themes of Ceará’s tradition, popular culture and identity appear constantly in the history of actions by the government of Ceará state. Whether through public policies, research or political discourse, the choice of a theme is not unbiased. It is part of taking a stance in the space, a way of demarcating an identity and the representation of the agents and institutions in the field that they have constituted - and continue to constitute. The construction of a local identity is connected to the preservation of memory, to a dispute over the legitimacy of a handicraft, a literature, a unique culture, but which does not exclude, despite localism, a national identity. The local culture is connected to the national culture by means of the school institution and government actions (municipal, state and federal), mainly through procurement notices or publications and curricular parameters that directly interfere in the preservation of these cultures (as well as in the sales of the editing sector), encouraging literary production around the theme. The objective is linked to an interest in connecting cultures as parts of the same place, forming a social space that houses several fields and subfields where editing centers and peripheries develop.

The centers also rule over the peripheries, which corresponds to the level of autonomy achieved in the field. In the case of books, the states with the lowest participation in the total national production are generally poorer, less urbanized or with fewer medium and large cities (Muniz Jr., 2016). These regions are also farther from large centers, with their production being most of the times labeled as ‘regional’ or ‘local’; in addition, they import books, magazines, television waves, etc. The centers regulate the exchanges between the inside and the outside, national and international, producing symbolic and practical effects.

Big Brazilian cities concentrate important editorial companies together with formal associations, informal collectives, establishment and visibility bodies - bookstores, distributors, printing offices, awards, fairs, etc. -, besides offering training for professionals to enter the editing market. These spaces also contain circulating capitals - cultural, economic and symbolic -, targets of the agents’ achievements, negotiations and conversions. Studying the arrangement among these variables, Muniz Jr. (2016) observes, is what allows identifying the existence of an editorial capital as a specific characteristic of cultural capital.

The professionalization of editing workers embodies a strong moment in the search for autonomy. It can be said that, in the case of Fortaleza, the agents are demarcated by the practice of autodidacticism and low professionalism. Some of them hold undergraduate degrees in languages, journalism and design, like illustrators. The undergraduate languages course, despite having been created in 1946 at the Federal University of Ceará’s School of Philosophy, Sciences and Languages, does not include editing training in its curricular base, and in the journalism program, created in 1965, the discipline that is most similar to the field of activity of book protagonists is graphic design. The design course, founded in 2011, is the closest one to editing careers, with disciplines covering graphic projects, history of typography, and paper engineering and binding. More recently, specialization courses in editorial design were created at private institutions, such as Sete de Setembro University.

The space for the production and distribution of children’s literature in the city of Fortaleza is characterized by an arrangement of practices, habitus and institutions that configure an editing subfield, whose main characteristic is the dependence on the state, provider of cultural and economic capital for investment in the sector. Lack of specialization, autodidacticism, printing at printing offices in other cities and regions, insufficient training courses in the field, and accumulation of functions are markers of a peripheral position in comparison with other editorial production centers. And, once again, indicators of the autonomy conquered by heteronomy.

Final Remarks

So far we have shown that the space in which children’s literature is produced and distributed in the city of Fortaleza is characterized by a heteronomy and an arrangement of practices, habitus and dispositions of the agents and institutions that form the editing subfield. Production depends mainly on the power and economic fields to be materialized, continuously legitimizing the state’s position as the ‘provider’ of a cultural and economic capital for investment in the city’s editorial sector. Lack of specialization, autodidacticism, search for printing offices in other states, few training courses in the editing field, and accumulation of functions are elements that help define a peripheral position before other states and cities and, once again, a heteronomy of the space. Despite competition disputes, the agents seek to be together for their growth and maturing.

The construction of a children’s book editing space is linked to games and rules that govern editing modes, themes, positions, journeys, dispositions and other structured and structuring structures that form the editing subfield: a heteronomous place in which its agents look for means to mature through the legitimation of local culture before other local cultures (and national culture also, even though it is partly due to external influence and linked to it as part of a whole), of partnerships with other agents and institutions outside territorial limits, in fairs and literary productions, but which also takes advantage of and claims dependence on the state by means of government procurement notices. That is, it is characterized as a peripheral space of dependent production.

Finally, it is possible to perceive that heteronomy is present in the practices and strategies of agents and institutions, constructing the singularity of the children’s book editing space in Fortaleza. This statement is based on the fact that many agents claim a greater participation by the state - funds for literary fairs, government procurement notices, etc. - and that a supposed disconnection from it is not possible, as the lack of readers hinders purchases outside the school sector. Thus, school demands and government purchases are what make this market’s economy work, though poorly at times. Other signs of heteronomy are the agents’ lack of specialization, autodidacticism, accumulation of roles (producers, editors, writers, illustrators, 02 or more in only one agent), and commercial fragility. However, there are also signs of a search for autonomy, with reading mediation and reader formation courses, storytelling in schools and in the spaces of publishing houses, search for other markets and presentation of publications outside the state or country. The construction of a space for children’s literature editing in Fortaleza within a power field - dominated by municipal, state and federal governments - is influenced by said field as well as by the economic field. That is, it is located in a subfield formed by a dependent and peripheral production.

REFERENCES

Acioli, S. (2012). É pra ler ou pra comer? A história da Padaria Espiritual para crianças (3a ed.). Fortaleza, CE: Edições Demócrito Rocha. [ Links ]

Adjafre, D. (2009). A batalha de Jericoacoara. Fortaleza, CE: Edições Demócrito Rocha. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (2013). Espaço físico, espaço social e espaço físico apropriado. Revista Estudos Avançados, 27(79), 133-144. [ Links ]

Catálogo infantil e juvenil 2013/2014. (2017). Fortaleza, CE: Edições Demócrito Rocha. Recuperado de: https://issuu.com/edicoesdemocritorocha/docs/catalogo_edr_2013_-_web [ Links ]

Catálogo infantil e juvenil 2014/2015. (2017). Fortaleza, CE: Edições Demócrito Rocha. Recuperado de: https://issuu.com/edicoesdemocritorocha/docs/catalogo_edr-2014-2015_-_escolas [ Links ]

Catálogo infantil e juvenil 2015/2016. (2017). Fortaleza, CE: Edições Demócrito Rocha. Recuperado de: https://issuu.com/edicoesdemocritorocha/docs/catalogo-edr_2015-2016-issu [ Links ]

Chartier, R. (1999). A ordem dos livros: leitores, autores e bibliotecas na Europa entre os séculos XIV e XVIII. Brasília, DF: Editora Universidade de Brasília. [ Links ]

FLLLEC: Fórum de Literatura, Livro e Leitura do Estado do Ceará. (2019). Recuperado de: https://forumdeliteraturace.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/memoria_flllec.pdf [ Links ]

Fortaleza, E. M. S. (2005). Literatura infantil cearense: contos, encantos e desencantos. (TCC de Especialização em Leitura e Formação do Leitor). Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza. [ Links ]

Fundação Demócrito Rocha. (2017). Recuperado de: http://fdr.org.br/democrito-rocha/ [ Links ]

Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação [FNDE]. (2017). Programa do livro. Recuperado de http://www.fnde.gov.br/programas/programas-do-livro [ Links ]

Júnior, I. A. P. (2003). Cearensidade. In: G. Carvalho (Org.). Bonito pra chover: ensaios sobre a cultura cearense. Fortaleza: Edições Demócrito Rocha. [ Links ]

Lahire, B. C. (2017). Campo. In A. M. Catani et al. (Orgs.). Vocabulário Bourdieu. Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Leão, A. B. (2007). Norbert Elias e a educação. Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Leão, A. B. (2012). Brasil em Imaginação. Livros, impressos e leituras infantis (1890 - 1915). Fortaleza: INESP, UFC. [ Links ]

Lebrun, J. (1998). O leitor entre limitações e liberdade. In R. Chartier. A aventura do livro - do leitor ao navegador: conversações com Jean Lebrun. São Paulo, SP: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Montenegro, T. (2010). Rachel: o mundo por escrito. Fortaleza, CE: Edições Demócrito Rocha. [ Links ]

Muniz Jr., J. S. (2016). Girafas e bonsais: editores ‘independentes’ na Argentina e no Brasil (1991-2015) (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. A. R. (2015). Em busca do Ceará: a conveniência da cultura popular na figuração da cultura cearense (1948-1983) (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza. [ Links ]

Ortiz, R. (1994). Legitimidade e estilos de vida. In R. Ortiz. Mundialização e cultura. São Paulo, SP: Editora Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Ortiz, R. (2000). Um outro território: ensaios sobre a mundialização. São Paulo, SP: Olho D’água. [ Links ]

Ortiz, R. (1994). Românticos e folcloristas: cultura popular. São Paulo, SP: Editora Olho D’Água. [ Links ]

Retratos da leitura no Brasil. (2019). Recuperado de: http://prolivro.org.br/home/images/2016/Pesquisa_Retratos_da_Leitura_no_Brasil_-_2015.pdf [ Links ]

Silva, O. A. (2001). Pelas rotas dos livros: circulação de romances e conexões comerciais em Fortaleza (1870-1891). Fortaleza, CE: Expressão Gráfica e Editora. [ Links ]

Sorá, G. (2010). Brasilianas: José Olympio e a gênese do mercado editorial brasileiro. São Paulo, SP: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Souza, R. J. (2004). Leitura e alfabetização: a importância da poesia infantil nesse processo. In R. J. Souza (Org.), Caminhos para a formação do leitor (p. 61-78). São Paulo, SP: DCL. [ Links ]

Viana, K. (2019). Entrevista com Klévisson Viana [Entrevista concedida a Jáder Santana] (Folha de Rosto, n. 12). Fortaleza, CE: Podcast da Editora Dummar. Recuperado de: https://soundcloud.com/user-499629010/folha-de-rosto-5-um-bate-papo-com-klevisson-viana [ Links ]

Zilberman, R. (1987). Literatura infantil: autoritarismo e emancipação. São Paulo, SP: Ática. [ Links ]

23How to cite this article: Leão, A. B., & Sales, A. C. M. Children’s literature editing in Fortaleza: regional variations and cultural mediations. (2020). Brazilian Journal of History of Education, 20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e118

Received: November 28, 2019; Accepted: March 25, 2020

texto em

texto em