Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1519-5902versão On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.20 Maringá 2020 Epub 01-Ago-2020

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e122

DOSIER

Brazilian History textbooks approaches about Brazil’s presence in the Latin American Southern Cone, in the nineteenth century

1Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Caicó, RN, Brasil.

2Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife, PE, Brasil

This search aimed at identifying and characterize the Brazilian History textbooks regarding the Brazilian presence in the platinum region, in the second half of the nineteenth century. Thirteen textbooks from different temporalities were selected, which comprehend a period from 1886 to 1999. The books selection observed some the criteria, such as having several editions, their adoption by elementary school networks, and the social-institutional position of the authors. The source analysis was done by the content analysis technique. Three groups of authors were characterized, with different concepts. Furthermore, some permanencies on the narratives of the analyzed textbooks were observed, such as the Brazilian Imperium guaranteeing the independency of Uruguay.

Keywords: brazilian imperialism; Platinum America; history textbooks

Constituiu objetivo da pesquisa em identificar e caracterizar abordagens em livros didáticos de História do Brasil em relação à presença brasileira na região platina, na segunda metade do século XIX. Foi selecionado um total de 13 livros didáticos de diferentes temporalidades, compreendendo o período de 1886 a 1999. A seleção dos livros observou critérios como possuir inúmeras edições, ter sido adotado por escolas das redes de ensino da educação básica e o lugar socioinstitucional dos autores. A análise das fontes se fez por meio da técnica da análise de conteúdo. Caracterizamos três conjuntos de autores com concepções diversas. Apesar disso, foram observadas permanências nas narrativas dos livros analisados, como a do Império brasileiro como garantidor da independência do Uruguai.

Palavras-chave: imperialismo brasileiro; América Platina; livros didáticos de história

El objetivo de la investigación fue identificar y caracterizar enfoques en los libros de texto de Historia del Brasil en relación con la presencia brasileña en la región del plata, en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. Se seleccionó un total de 13 libros de texto de diferentes períodos, comprendido entre 1886 y 1999. Se observó criterios tales como tener numerosas ediciones, haber sido adoptados por escuelas de educación básica y el lugar socioinstitucional de los autores. El análisis de las fuentes se realizó a través de la técnica de análisis de contenido. Pudimos caracterizar 3 conjuntos de autores con diferentes concepciones. Sin embargo, se observaron permanencias en las narrativas de los libros analizados, como la del Imperio brasileño como protector de la independencia de Uruguay.

Palabras clave: imperialismo brasileño; América Platina; libros de texto de historia

Introduction

As Bobbio, Matteucci and Pasquino (1998, p. 611) we considered that “[...] although the phenomenon usually linked to the expression Imperialism [...] have been manifested under different ways and modalities in all times of History, this expression is partially recent”. The authors indicate that a series of systematic studies on the various phenomena linked to what would be called ‘imperialism’ has begun only in the late Twentieth Century.

Despite we recognize that since the late Nineteenth Century until the current days several currents of thoughts have dealt the specific matter of imperialism, the discussion on the concept may start by detaching the expression by Bobbio, Matteucci and Pasquino (1998, p. 611), who point the imperialism as “[...] violent expansion by states or similar political systems within their territorial influence or direct power, and ways of economic exploitation to the detriment of the subjugated states or peoples”.

Further the economic matters highlighted by the authors, we add those of a political and cultural nature, because the phenomenon of imperialism has exceeded the dynamics of economic interests. Several authors, such as those who write on the post-colonial period have studied political and cultural impacts of imperialist policies in countries or regions which were colonized in the American and African continents, especially. Regarding the American continent, a series of historical events seems to gather attributes that may be explained based on the notion presented. A direct or with the use of allies of occasion British interference on policies of countries from the platinum region in the Nineteenth Century produced events that made an imperialist order evident, dominated by interests or industrial capital. Countries of the region have taken initiatives in order to interfere on the political and economic order of their neighbors, what produced tensions and conflicts which demanded actions by diplomatic bodies, or in the limit, they were solved in a bellicose way, such as the War of Paraguay. Events such this last one and by extension this effects and consequences are relevant because they influence the directions of relations among the nations of the region over the centuries that followed.

Each region’s History and historiography have conceived descriptions, explanations and analysis that allowed settling and guide national policies, sometimes justifying these policies, sometimes criticizing them. This symbolic content has contributed to forge the idea of nation and national in the late third of the Nineteenth Century, when it invaded the Elementary Schools in implementation and expansion in the next century. It started to make part of the syllabus and being present in most lustrous curricular object among all, the History textbook. It does not mean that only to History the task to contribute for the formation of ideas of nation, nationality and national sovereignty was reserved. Other curriculum subjects have contributed and still contributes to it, but it was especially attributed to the History answer for that. Authors such as Bittencourt (2008, 1990), Nadai (1992-1993) and Abud (1997, 1998, 2011) have referred to this configuration of the History teaching in Elementary School when it was introduced in the syllabus in the early decades of the Nineteenth Century, and also in the next decades. Despite what the critics affirm, it also demonstrates that the school constitutes a social institution permeable by what happens in the society, either when it is called to disseminate and instill in children and young people the contents of an uncritical nationalism, or when it criticizes that same nationalism and announces respect in relations between among and peoples.

This order of debates articulates the issue with the general thematic of the dossier, ‘Emancipation processes and education in America: history, politics, and culture (19th and 20th centuries)’ - even by the educational policy dimension in a critical reflexive perspective that guides it, either by the continental space where the events have occurred, or by the chronological clipping selected.

Studies and researches on the History textbook in Brazil

Within the space reserved for this study, we intend to identify and characterize the approaches that authors of Brazilian textbooks selected for this research have chosen on the matter of Brazilian imperialism in Platinum region on the nineteenth century second half.

Thereby, we disagree with what Choppin (2002) found regarding the negligent deal that historians had dealt with this object of school knowledge. “If manuals have been neglected for long time by historians, it is also because they were considered as simple mirrors of Society from which they come - an ingenuous conception - or such as ideological and cultural vectors” (Choppin, 2002, p. 10.)

In Brazil, studies and researches that take the textbook as object of analysis belong to a tradition that dates back to the 1950s, when Rafael Grisi (1951) produced the seminal work titled Teaching of Reading: method and booklet (O ensino da leitura: o método e a cartilha in Portuguese), study by which, according to the title itself, the reading method of booklets is taken as object of study (Freitag et al., 1989). In the following decade, the writer who was born in the state of Pernambuco in Brazil, called Osman Lins, published a study in 1965, in which he examined 50 Portuguese language compendiums used in the secondary teaching, that correspond to the High School (ginásio and científico/clássico, as called in Brazilian Portuguese at that period), focusing in literary texts selected which were part of the mentioned compendiums. His findings made evident the marginal place reserved to the Portuguese and Brazilian classic texts and the distance regarding the Brazilian People daily problems, what made him conclude the outdated texts that compound the collections examined.

Lins’ studied was repeated ten years later, this time by examining 20 books launched for Portuguese teaching in the same levels studied in 1965. The results found showed important changes not only in the contexts of the books, as well as in their manufacturing process. On one hand, the study found the topicality of the (contemporary) authors, e.g. Carlos Drummond de Andrade, João Cabral de Melo Neto, Cecília Meireles and the permanence of forgetting the classic ones, such as Machado de Assis and Eça de Queiroz. Lins (2018) observed the emergency of images in the composition of pages, phenomenon that followed a certain favor to the image, suggesting what the author called ‘iconographic delirium’, what in the limit gestated a kind of ‘Educational Disneyland’ that invaded the spaces of the most eye-catching teaching material.

In fact, what Lins denounced in his work were the effects of modernization because of the emergent market of books and its subordination to the cultural industry which was growing in the country.

Thereby, the author accused a textual standardization as signal to the market character observed in the book. The author also criticized the abuse on the simulated playful tone and the pretense camaraderie between author and reader.

A study published in 1976 which was coordinated by the professor Maria de Lourdes Chagas Nosella, and suggestively titled Beautiful lies: ideology underlying didactic texts (As belas mentiras: a ideologia subjacente aos textos didáticos in Portuguese), announced the directions that research on the most important material of the school curriculum in Brazil was taken. The analysis of textbooks used in the four early grades of what was called first degree, that correspond to the early years of the elementary school made evident the pernicious effect of ideologization of texts about unprotected children, those who belonged to the working class. The critical character of discussions by Nosella was in fact a transposition to the Brazilian context of what was made years before by Marisa Bonazzi and Umberto Eco for Italian reading books, whose report won the evocative title Lies that seem to be true (Mentiras que parecem verdades in Portuguese - 1980).

Nosella’s research assumed in that early years of 1970 decade a purposeful character when defended the suspension of the purchase and free distribution by the States of books that the evaluation pointed these pernicious effects and distribution of resources to the schools in order to the professor indicate the book and the material that he or she wanted to use. The work started to influence an important amount of critic studies on the textbook emphasizing the analysis of the served contents. If Lins, in a pioneer way had called attention to the fact that books are not exempt cultural goods, neutral ones in another explanation, Nosella deepen this perception when explained the ideological character of the served contents.

In the 1980s decade, the first big research of the state of knowledge on the textbook came to the light, coordinated by the professor Bárbara Freitag. The research concluded that the analysis on the textbook content has become one of the most explored content. It found that the analysis on the textbook content was occurring since the 1940s, but it was intensified in the 1980s first half. In this last one, two great tendencies were configurated: the displacement of analysis from the official evaluating entities to the scientific-academic public institutions and the emphasis to the needy child, chosen by thesis, books and articles as the privileged subject of research, because numerous of these texts searched for solve the problem of the needy one, proposing reformulation of textbook content.

The studies on the textbooks became noble ones and were expanded for several countries. In France the figure of Alain Choppin (2002, 2004) is highlighted because of his contribution to a better definition of this cultural good, that is why we take to this work the meanings that he has attributed, which we retained to walk with them during this analysis. To Chopin, quoted by Batista and Rojo (2005), ‘textbooks’ or ‘school manuals’ are terms that design ‘classroom utilities’. They are produced with the aim at helping to teach a certain subject by presenting an extensive set of curriculum content according to a progression, under unities or lessons form, and through an organization to favor both collective usage (in the classroom) and individual ones (at home or in the classroom). “The textbook is in the classroom daily and it constitutes one of the basic elements to organize the teaching work” (Batista, 2005, p.17).

In the same period that Choppin was producing his Works in the Institut National de Recherche Pédagogique (INRP) - Paris, France -, in Brazil, Circe Bittencourt was defending his thesis in the Social History area at the University of São Paulo (Universidade de São Paulo - USP), titled Textbook and historical knowledge: a history of school knowledge (Livro didático e conhecimento histórico: uma história do saber escolar - 1993), and she was introducing new elements to understand the textbook, what pointed it as a complex cultural object. Bittencourt based her research on the concepts of the Frankfurt School to announce the textbook as a product (commodity) of the cultural industry. This economic cultural dimension incorporates the idea of the book as a school knowledge support and pedagogical methods, as well as a vehicle of values and ideologies system. There is no doubt that Bittencourt enlarged the understanding on this cultural good and its presence at school and in the teaching pedagogical practice of the history teacher.

Twenty first century will bring renovation of interest in textbook studies expressed by another research of the state of knowledge type, this time carried out by Antonio Augusto Batista and Roxane Rojo, titled Textbooks in Brazil: scientific production (Livros escolares no Brasil: a produção científica in Portuguese - 2005)28. In this second study other aspects on the knowledge production regarding the textbook were privileged. They were concentrated in the academic production, especially those from the graduation programs. Ergo, they identified the volume and temporary distribution of scientific knowledge (thesis, dissertations, articles, communication) in the period from 1987 to 2001. They were concerned in describing the circuit of knowledge diffusion. Regarding the interests in these researches, they identified the privileged content through the analysis, higher education institutions where they were produced, as well as those in which more works were concentrated. They were concerned in point the public nature of these institutions, their localization, and the frequency of works by knowledge area. The survey of Works showed this is a quite promising investigation dominium29.

Thereby, this investigation is within this research tradition, which drinks from its contributions, also searching for enlarge the borders of knowledge regarding the History field and the teaching of classic contents of programs in the same area in the Basic Education.

In the next section we present the research procedures which allowed the selection of textbooks analyzed and the criteria used to choose them.

Textbooks selected for the research

We were driven to analyze History textbooks by several reasons. These objects of curriculum and for teaching always followed us in our school and extra school learning experiences. Some researches point the textbook as the written work that is most present in Brazilian homes (Bittencourt, 1997). Even more than literature books, much more than newspapers and magazines, and infinitely more than technical-scientific books. The same researches point that the more social disadvantaged and poor the homes, lower the genre works diversity. Therefore, for most lower-class families, the textbook is almost the only genre of written text in their homes (Bittencourt, 1997).

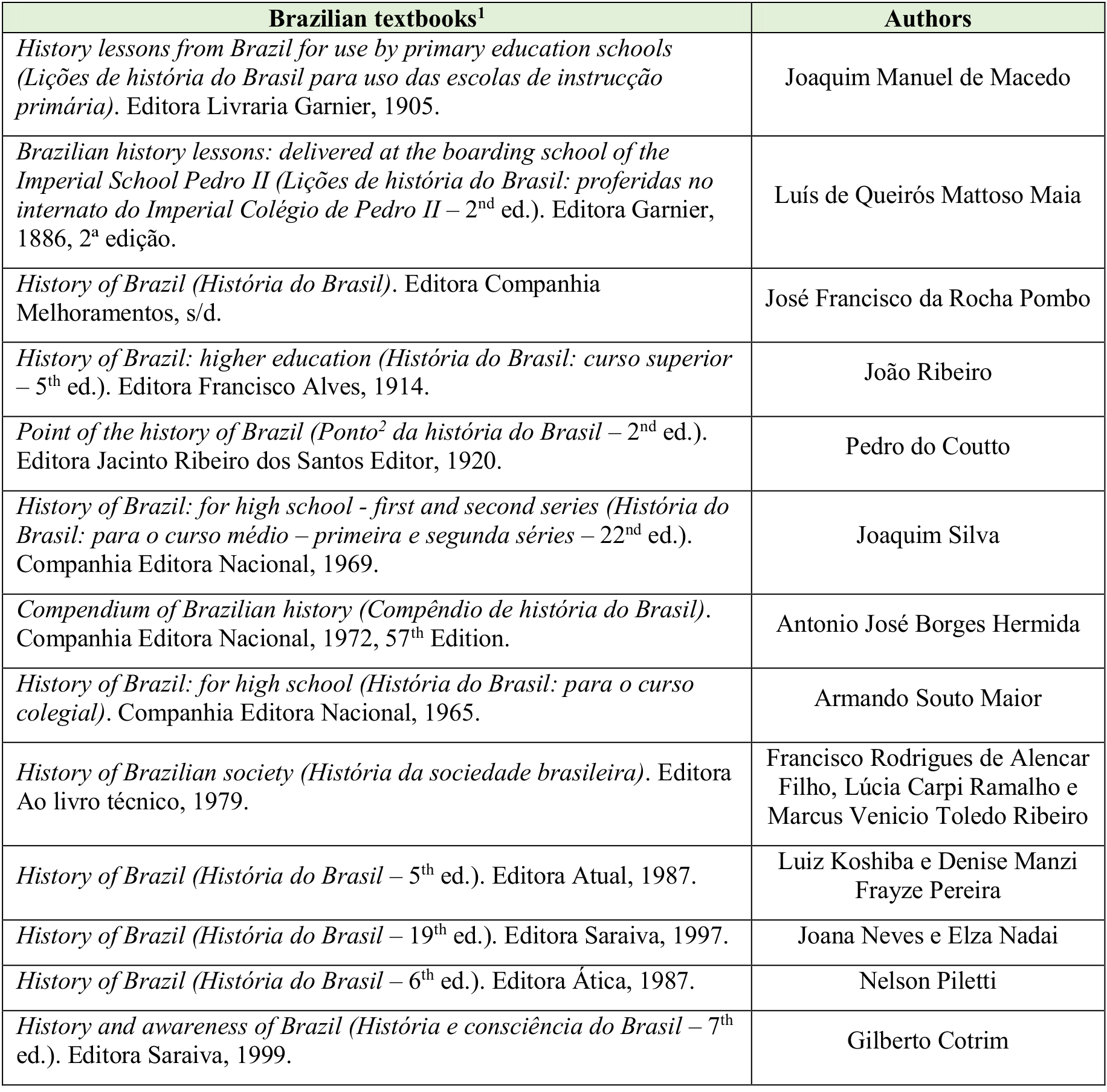

Regarding this research, we were driven to analyze the History of Brazil textbooks, as explained before, but those written and published in different contexts of production, covering a period from 186130 to 1999. We searched in the collection of didactic works of History of Brazil those books that have good acceptance in the editorial and school settings, and which contributed for the meaning assignment process of ‘historical awareness’31 of Brazilian children and young generations. To select the books from the announced intentions, we observed the following criteria: (1) works with numerous editions32 and (2) the social institutional place of authors33. By observing the criteria detached, we selected 13 Brazilian textbooks from different periods34 which were organized in the Frame 1, as follows, distributed by their publishing data.

Imperial School Pedro II and the Brazilian Historical and Geographic Institute (IHGB in its Brazilian Portuguese acronym) are two of the main institutions that since the Nineteenth Century until the Twentieth Century early decades were responsible by institutionalization of historical knowledge. The first one in a school curriculum level, and the second in an academic level. It is important highlight the role as a reference school played by the Imperial School Pedro II until the creation of the Ministry of Education in the 1930s decade. The syllabus of the mentioned school exercised almost the national curriculum function for long time, because numerous educational institutions of the various Brazilian provinces, which were called States after 1930s, organized their curriculum from the one developed by that school. The textbooks written by the professor who work at Pedro II have had the quality label and they start to be adopted by other Brazilian provinces/States. It is where certainly coming the longevity of these textbooks, materialized in their several editions, what generates our interest to analyze them (Vechia & Lorenz, 1998; Nadai, 1992-1993).

We detach that our aim in the following analyzes was not point to the possible historical or pedagogical mistakes of authors, and neither indicate those who supposedly would be more coherent or updated regarding the discussions of their time on the Brazilian imperialism in the Latin American South Cone in the Nineteenth Century. We choose work with a large temporal clipping and therefore any analysis in this sense would take the risk to be anachronistic one. That is the reason why we preferred carrying out a contextualized analysis by which selected books were inserted in their production context searching for didactic and pedagogical, curriculum and historiographic elements resources available at each time.

Brazilian imperialism in History of Brazil textbooks

In order to organize information surveyed from the didactic Works selected, we constructed the central category of analysis detached35, guided by the aim at identifying and characterize the approaches that authors of textbooks performed regarding the Brazilian imperialism in the Platinum region in the Nineteenth Century second half.

Six textbooks analyzed - by Macedo (1905)36, Maia (1886)37, Rocha Pombo (s/d)38, Silva (1969)39, Borges Hermida (1972)40 and Souto Maior (1965)41 - do not recognize Brazilian imperialist policy. These authors used arguments to justify Brazilian interventions in Prata and defended basically a thesis that Brazil would be ‘obliged’ to interview in the Platinum countries.

Imperial actions in these countries were configurated, for the mentioned authors, more as reaction and defense than an imperialist attitude, in other words, it was a violent expansion of Brazilian State on the territorial area under its influence, to the detriment of the Uruguayan and Paraguayan states and peoples.

Brazilian conflicts in Uruguay and Argentina in the 1850s decade and again in Uruguay in the next decade were presented as ‘inevitable’ conflicts. The thesis of ‘inevitability of conflict’ appeared in the work by Macedo (1905), who affirmed:

[...] the border of the empire of Brazil in Rio Grande do Sul was frequently violated; besides, Rosas and Oribe unintentionally undone Brazilian vassals who lived in Argentina and Uruguay; and as the repeated complaints of the government of Brazil have not been answered, the war has become inevitable (p. 385, emphasis added).

Macedo (1905, p. 390), when questioning the students, asked a curious question whose character of induction opened the intention up to make the author’s thesis prevail: “Why the war became inevitable?”. The matter of inevitability of the war was already settled, it would be enough for the student to explain its motive. The war against Uruguay in the next decade (1864-65) was also justified by the author and presented as a reaction to the violence against Brazilian which practiced in that region: “The war against the Eastern Republic of Uruguay was caused by the ongoing complaints by Brazilian residents in this Republic. Brazil vassals suffered assaults, thefts, and all kinds of violence” (Macedo (1905, p. 392).

Maia (1886) used the same arguments than Macedo (1905) and affirmed:

Oribe’s hordes bothered our Southern borders with incessant depredations that have already motivated the invasion of baron of Jacuhy in Banda Oriental. - Brazilian government used pacific and diplomatic means with an admirable long-suffering against the constant exigences by the Argentinian government passed on from acrimonious and insolent language which did not disguise the bad faith and audacious pretensions by the Buenos Ayres dictator. [...] whose [war] responsibility must weigh entirely on Rosas the tyrant (Maia, 1886, p. 354).

Maia (1886) pointed the war against Oribe and Rosas as the last Brazilian resource when all the possibilities for diplomatic resolution were depleted. Brazil intervention in Uruguay in 1864 was explained by Maia as a Brazilian reaction: (1) to the “mistreatment and harassment suffered by Brazilian citizens in the Eastern State [...]” and (2) because Uruguay government did not answered to the requirements of the Empire of Brazil. Maia (1886), defended the legitimacy of Brazilian intervention by affirming: “The procedure of the empire in such a conjecture was quite fair that the Argentinian Ministry D. Rufino de Elizalde recognized that it was in a protocol he signed with the Brazilian plenipotentiary (August 22nd)” (Maia, 1886, p. 361).

Silva (1969, p. 244) also intended point the ‘legitimate interests’ by Brazil in Prata, once “[...] it was the single entrance to reach the Mato Grosso lands by waterway”. For this author, Brazilian interventions were supported in the defense of national ‘legitimate interests’ in the region. For Rocha Pombo (undated), Brazilian interventions in Uruguay were presented as the only possible solution - an ‘extreme’ but necessary ‘resource’.

Silva (1969) and Borges Hermida (1972) repeated the same argument, that Brazil would have been impelled to intervene in Uruguay and Argentina. The first author defended that the conflict by the Empire against Aguirre in 1864 occurred because he “[...] started to chase and mistreat Brazilians” (Silva, 1969, p. 244), arguing that the weapons were the last option and they only were used because Brazilian complaints were not answered42. The second author detached that “[...] the blancos43, enemies of Brazil, mistreated Brazilian residents in Uruguay, and invading the Rio Grande territory, attacked farms and stole cattle” (Borges Hermida, 1972, p. 225), also because of this, the Empire of Brazil, not without first trying to resolve issues through diplomatic channels, would have used the extreme resource of weapons.

Souto Maior (1965, p. 321), in his turn, also detached the attempts by the Brazilian Empire to resolve issues with Uruguay through diplomatic channels:

on May 18th our envoy delivered a delicate note to the government of Aguirre setting out the purposes of his mission: [he] asked for compensation for the damages caused to the Brazilians at the border and punishment of those responsible for the robberies [...] [he] received official response in very rude terms.

It is interesting observe that the note send by the Empire of Brazil is ‘delicate’ and the answer was ‘rude’. We may glimpse here, maybe a narrative based on the confrontation between civilized versus barbaric, a view strongly disseminated by Brazilian nationalist historiography regarding the Southern neighbors, and full of a bias based on the colonial thinking.

Souto Maior (1965, p. 319) detached that the Empire granted “[...] financial aid so that the Oribe’s troops were defeated”. In contrast to this statement, he emphasized that the Empire only would have taken such an action because it was “[...] concerned with the events of its southern borders, which not only seriously damaged Rio Grande do Sul but also prevented the waterway access to Mato Grosso”.

As the ‘financial aid’ would have been insufficient, the Empire started the military action. Brazilian interventions would then have gone from ‘financial aid’ to ‘military action’. Anyway, both one and the other, imperialist actions widely known in platinum region history are softened in Souto Maior’s narrative (1965), since the Brazilian State would only have taken such actions because of its concerns on the southern borders and the free access to the River Plate.

Souto Maior (1965) emphasized that Brazilian Empire did not intend to reattach Uruguay, according to rumors that had spread in Montevideo. For this author, there were Strong reasons for the Brazilian government considered interests to preserve that countries independence44. For Maia (1886), Rocha Pombo (undated) and Silva (1969) too, Brazil was the one which will ensure the peace in Prata region, and as a protector of Uruguay's independence. This is a common discourse at that time, propagated by nationalist historiography.

Regarding the War of Paraguay, Rocha Pombo (undated) produced an extremely negative analysis of Paraguayan soldiers, seen as ‘crazy’, ‘fanatics’ and designated by the collective ‘chusma’45. Influenced by the ‘memorialist-military-patriotic’ historiography - of a nationalist nature -, he portrayed an image of Brazil as liberator of the Paraguayan people from the tyranny of López: “Population of all points that were already free from the tyranny elected Diaz de Bedoya, Cyrillo Rivarola and Carlos Loixaga to constitute the Government Board” (Rocha Pombo, undated, p. 278)46.

It is important highlight that the traditional historiography about the War of Paraguay, that these History textbooks of these authors would be the expression of their didactic transposition47 (Chevallard, 1998), and privileged in their approaches the war strategies, also praising military commanders, such as Duke of Caxias and Count D´Eu. The first moment of Brazilian historiography was configurated more as a memorialist-patriotic narrative than an historical analysis itself. In these narratives there was usually the prevalence of an interpretation that pointed the Paraguayan government - personified in Francisco Solano López figure - as the cause of the conflict. This historiography became hegemonic in Brazil at the end of the nineteenth century, until at least the 1960s decade.

Ribeiro (1914)48, Coutto (1920)49, Alencar Filho, Ramalho and Ribeiro (1979), Koshiba and Pereira (1987)50, Nadai and Neves (1997), Piletti (1987) and Cotrim (1999)51 recognized Brazilian imperialist attitudes regarding the neighboring countries of Prata but each one of them printed certain peculiarities in their analyzes, which we detached as follows. Ribeiro (1914), for example, considers Brazilian imperialism in republics of Prata as ‘the bigger mistake of the second empire’:

The bigger mistake if the second reign (that however did not make it unpopular) was criminally recovering tradition, even forgotten in the first one, of the military supremacy and policy in small States of Prata, then unhappy with themselves for the scourge of corruption and tyranny (Ribeiro, 1914, p. 508).

Even criticizing Brazilian imperialism in Prata region, Ribeiro (1914, p. 508), as we may infer by the quotation above, also expressed a negative vision of the neighboring republics, considered by him as countries “[...] countries unhappy with the scourge of corruption and tyranny”. However, we could affirm that eve the author criticizing Brazilian ‘military and political supremacy’ in ‘small States of Prata’, his vision regarding Brazilian imperialism is double, because he defended that Brazil would have ‘been dragged’ to international issues and conflicts in Prata region: “[...] Brazil is dragged again to the policy (very unjustifiable, we said) of supremacy on the southern States” (Ribeiro, 1914, p. 511-512). Na adverse context would lead, in a natural and inevitable way, the country to exercise hegemony over the Platinum region.

It is interesting notice the ambivalences out from the analysis by Ribeiro (1914), because at the same time that the author pointes that Brazil was ‘dragged to the policy of supremacy’ in Prata, he referred it as very unjustifiable. However, the idea itself to be dragged means that it is against the will - or as the last option to be taken, what may be understood as a disclaimer position. Regardless, it is important emphasize, under the risk of incurring anachronism, which the edition of the book analyzed was published in 1914 - and its first edition is dated in 1900 - period of prevalence in hegemonic way in Brazil, the nationalist historiography regarding the War of Paraguay and the Brazilian performance in Southern Cone. Therefore, the author’s dubiety may be positioned in its appropriate place, because at the same time that a transgression to the hegemonic conception on the participation of Brazil in the War of Paraguay and the interference in the neighboring countries was performed, he recurred to certain explaining elements traditionally accepted and contemporary to that time of the work was produced.

Ribeiro (1914), even bringing new explaining elements in his analysis, he repeated, as we said, some arguments of nationalist historiography, like this one in which the Empire of Brazil would have been the ‘guarantor’ of Uruguay’s independence when faced Rosas and Oribe, or when he referred the Platinum republics in a negative way:

States of Prata were for a long time not loyal and uncomfortable neighbors for us, and whose friendship could not be counted, attentive to the perpetual instability and demoralization of the governments of lords or tyrants under which they lived. This not loyalty had an explanation in which they were quite inferior, and they did not want to confess it. Brazil seemed for them as an arbitrator and forced judge that the circumstances of that time imposed on them (Ribeiro, 1914, p. 512. emphasis added).

Ribeiro (1914, p. 515) presented not only a negative vision of the neighboring republics but of the Paraguayan People itself, specifically:

Paraguay, since long ago, lived under an absolute regimen, despite the exteriority of some republican formulas, and its inhabitants were coerced under strong discipline, they blindly obeyed their dictators. Lacking virtues, they had the religious and political fanaticism according their own exclusivism of their national culture, influences all trade with the rest of the universe. Martial law or the state of siege was always in constant force in Paraguay.

Ribeiro (1914), at same time in which he searched question whether the fact that Brazil would have been the ‘civilized’ country fighting a ‘barbaric’ country - regarding the War of Paraguay -, could not failed to escape current explanations at the time and finished by detach the ‘inferiority’ of the platinum republics and the ‘superior’ position of the Brazilian Empire. It is interesting notice out as Ribeiro produced a narrative which, while criticizes Brazil's hegemony policy in the Prata, centralizes his analysis in the binomial civilization versus barbarism:

In these republics, true military feuds, not yet consolidated by time, the opposition party achieved triumph only through revolution; to this violent resource, Brazil came to offer another worse, the call for foreign intervention. Civilization and the liberal ideas never could serve as a pretext and still justify the immorality of our conduct (Ribeiro, 1914, p. 512).

Ribeiro’s (1914) argumentation heart was concentrated in the following position: although the objective was to bring ‘civilization’ and ‘political stability’ to a special region, armed action would not justify such an attempt. In other words, criticism of Brazilian imperialism in the platinum region is accompanied by, at the same time, by recognition of ‘superiority’ - moral and civilizational - of Brazil in front of the neighboring republics.

Ribeiro (1914) strongly diverged from authors of his time regarding the conflicts between Uruguayans and Brazilian gaucho ranchers in southern borders of the country. According to this author, they were the last ones who intervened in Uruguay's domestic politics and the attitudes of the government of that country were understood as ‘retaliation’. Ribeiro (1914, p. 513) pointed that our neighbors “[...]then looked at us with justified fear”.

Despite the author had detached the ‘peace spirit’ which ‘personally cheered’ Saraiva points out that “[...] imperial policy was too arrogant to be listened to with pleasure in the small republic [Uruguay]” (Ribeiro, 1914, p. 514). He considered Brazil's intervention in Uruguay as “[...] unworthy and humiliating”.

Regarding Paraguay in 1850s decade, Ribeiro (1914) affirmed that the Empire used its intimidation to push the Guarany country, under Carlos López’s commandment, signed treaties related to border issues between the two countries. Ribeiro pointed the three neighboring republic as satellites regarding Brazilian external politics: “[...] the world, however, did not fail to realize how precarious was the luck of the three republics that, alongside Brazil, appeared on satellites of its foreign policy” (Ribeiro, 1914, p. 517).

Coutto (1920), such as Ribeiro (1914), was dubious in relation to Brazilian imperialism, because at the same time in which he pointed to the Brazilian policy in Prata as the ‘single responsible’ by the War of Paraguay, on the other hand, he softened Brazilian interventions in Uruguay and Argentina. The author made an interesting analogy between the British and Brazilian Imperialism, detaching the following contradiction: Brazil suffered the British imperialism, and at the same time inflicted it to other smaller countries its own imperialism52:

The less dignified attitude used by strong peoples towards those who do not have considerable armies and powerful armaments, Brazil had the proof, in the role of offended, pending with England, known as the Christie Question, named after the British plenipotentiary [...] This highly condemnable procedure by England part, and that is moreover the one followed by all militarily strong countries, provoked just and worthy revolts by Brazilians. [...] however, it is not excluded to remember that Brazil he practiced the same with its then weak neighbors, undoubtedly our enemies but worthy of respect and protection. Pedro II did not understand like this, that that at all times disturbed the order, including assisting revolted warlords against the instituted power [...] England's conduct was as incorrect in this as in other cases, as it is commonly the arrogance that pseudo-civilized countries exert against those inferior to them in armed force (Coutto, 1920, p. 204-207, emphasis added).

In Coutto’s work (1920), Brazil figured as a regional potency that interfered in internal questions of neighboring countries. In this sense, England exercised a global imperialism, and mutatis mutandi, Brazil exercised a regional one. The author performed a severe critic regarding the countries which, with superior war force, intervened in smaller countries under the civilizational pretext. Despite all these critics performed by Coutto (1920, p. 201, emphasis added), he retaken the current explanation of that time and affirmed that

[...] Before so critic situation that even foreigners were respected, intervention from any potency interested in the American peace is imposed; and Brazil was obliged to do it, because it was favorable to the complete autonomy of Uruguay.

Despite strongly criticizing Brazilian imperialism, Coutto (1920) pointed Brazil’s intervention in Uruguay as something that was obliged to do, that is the contradiction and dubiousness of the author. However, the same logic used by Ribeiro (1914) may be used to Coutto, because the work analyzed is of 1920 and the first edition of 1918.

Following the hegemonic historiographical view of the time, based on nationalism, Coutto (1920) affirmed that Brazilian State was obliged to intervene to preserve the independence and the peace in Uruguay. Brazilian imperialism/interventionism is softened, seen as something necessary. Brazil would safeguard Uruguay’s Independence and autonomy, defending it from Rosas’ imperialism (Argentina).

However, Coutto (1920, p. 204) promoted a critic to Pedro II’s government, affirming he has ensured the Independence of Uruguay exchanging by “[...] requiring great favors [...]”, such as “[...] requiring devolution of slaves who escape to there”. The author still detached fears that neighboring countries had about the foreign policy of the Empire of Brazil.

Solano López, offering his mediation, worked to some extent in self-defense, because according to data from imperial government, it was quite possible after crushing Uruguay, the echoes of triumph get his homeland (p. 208). [...]

It is true that López has long been preparing for war; however, in no way this should cause admiration, because the suspicion that Brazil then inspired neighboring republics (Coutto, 1920, p. 213).

Coutto (1920) is very explicit and emphatic in stating that Brazilian imperialist policy that generated the War of Paraguay. Nevertheless, he described it as whether it was a result from Dom Pedro II’s own will (selfishness). In Coutto’s narrative, sometimes Brazilian imperialism is criticized, been pointed as the cause of the War of Paraguay, whole in another ones it is pointed as necessary, in the sense of preserve Uruguay’s independence and peace. Thereby, Brazil is represented by the author both as an imperialist regional potency that intervene in neighboring countries, even generating serious war conflicts, and as maintainer of the integrity of smaller countries, e.g. Uruguay and Paraguay (of post war), helpless in the face of Argentine imperialism.

According to Alencar Filho, Ramalho and Ribeiro (1979), Brazilian supremacy in Prata had, in the last analysis, the intention to avoid the emergence of any other ‘great nation’ in the region.

Aiming to prevent the consolidation of any ‘big nation’ in the region - in which met the British interests - Brazil always supported the independence of small countries, such as Paraguay. Hence, it preserved its political supremacy in the area, as well as the ‘free navigation in the La Plata Basin’ (Alencar Filho, Ramalho, & Ribeiro, 1979, p. 168, emphasis by the author).

According to the authors previously mentioned, until 1850s decade, “[...] Brazilian interventions had only been diplomatic, but from 1851 the action started to be a military one” (Alencar Filho, Ramalho, & Ribeiro, 1979, p. 168). As explanation for military actions in neighboring countries, the authors pointed the interest of “Southern ranchers and charqueadores53, who suffered ‘competition from the platinum production’ and they saw the military intervention as a solution for their problems” (Alencar Filho, Ramalho, & Ribeiro, 1979, p. 168, emphasis by the authors). The authors still detached the Brazilian empire concern on ‘better controlling the southern region of the country’, because it had already attempted political separation.

Alencar Filho, Ramalho and Ribeiro (1979), differently from other authors analyzed until here, Brazilian interventions in neighboring countries, especially in Uruguay, were explained from economic interests of Southern ranchers and charqueadores who saw it as a way to finish the competition from the neighboring country through military intervention, allied to the wish by the Empire for maintain Brazil cohesive, meeting the southerners interests. But in the background, there are also violations of Brazilian borders by individuals/groups from Uruguay, as well as looting that southern ranchers suffered from their neighbor.

Regarding Brazilian imperialism in Platinum region54, the position adopted by Koshiba and Pereira (1987) is dubious: they softened Brazil’s interventions in Uruguay, but on the other hand, they presented critical position before the Brazilian imperialist action regarding the Guarany country in the War of Paraguay. These authors pointed Brazilian intervention in Uruguay, against Oribe in 1850-1852, as a way to avoid that Rosas annex the Uruguayan territory, it means that in 1980s decade the argument that Brazilian intervention in Uruguay would be to safeguard the Independence of that country was repeated by Koshiba and Pereira (1987): “To avoid the worst [annexation of Uruguay by Argentina of Rosas], Brazil supported Rivera against Oribe and Rosas, intensifying tensions between Brazil and Argentina. The confrontation between the two countries seemed to be inevitable” (Koshiba & Pereira, 1987, p. 220).

Brazil’s intervention in Aguirre’s government in 1864-65 was also represented by Koshiba and Pereira (1987) as something inevitable, like the resource to be used, thus consciously or unconsciously justifying the bellicose and imperialist attitudes of Brazil. For these authors, the following reasons lead Brazilian empire to intervene in Uruguay.

Retaliations against Brazilian citizens resident in Uruguay, violations of Brazilian borders and attacks to gaucho ranches by Uruguayan armed gangs. Therefore, the imperial government decided to protest and demand compensation from the Uruguayan government, which remained indifferent [...] to Brazil there was no other way but reprisal armed by land and sea (Koshiba & Pereira, 1987, p. 221, emphasis added).

Both for Nadai and Neves (1997) and for Piletti (1987), Brazil was represented more as a Britain’s ‘puppet’ than as a regional potency imposing its will and force55. According to Nadai and Neves (1997, p. 225), for example, Brazil was a representative of England in Platinum region. The authors affirmed that in Brazilian interventions in neighboring countries “[...] the interests at stake were rarely Brazilians” (Piletti, 1987, p. 115). However, they suggest that both Brazil and Argentina also had interests at stake in this conflict, and they not act only by England’s influence: “Brazil and Argentina, in their turn, had interests in some land areas of Paraguay”. They also affirmed that, at the end of the War of Paraguay, “[...] Brazil and Argentina got the lands they intended - 140.000 square kilometers - but on the other hand, they increased their dependence on England” (Piletti, 1987, p. 115). Imperialisms of Brazil and Argentina are presented by the same author in a set, in other words, as there was convergence between them. Another part of the text in which we could glimpse the Brazilian and Argentine imperialisms is when the author approached the matter of the Triple Alliance Treaty, reporting that its objective was “[...] destroying and sharing Paraguay” (Piletti, 1987, p. 115), showing imperialists and bellicose intentions by the allies.

The authors of didactic works mentioned in the paragraph above may be pointed as representatives of the so-called revisionist historiographical strand on the War of Paraguay, which supports the imperialism, especially the one played by Great Britain, that would be the main engine of the war. Analyzing this historiography, we observed the relevance of economic causes, especially those linked to the development of international capitalism. However, despite the indication of economic causes, in which the British imperialism presented founding role, the authors did not exclusively attribute to the economic elites of that country the cause of the war, because they recognized the role of local elites as agents that favored the penetration and exploitation of British power in the region.

Unlike Borges Hermida (1972), Nadai and Neves (1997, p. 225), they questioned the image of Brazil as a friendly country and referred to the foreign policy of the Second Empire as an example: “Despite the image of a peaceful country, which stood out for its cordiality in international relations, Brazil maintained serious and constant conflicts with neighboring countries throughout the heyday of the Second Reign”. The authors detached that the conflicts that occurred in Prata have relation with Brazil's interventionist policy, which intervened in internal matters of its neighbors: “For the most part, these conflicts were related to Brazil's interference in the internal issues of other countries or in the issues that led these countries to face each other” (Nadai & Neves, 1997, p. 225).

This treatment of the War expresses a certain shift in the axis observed at a given moment in Brazilian historiographic production. In the mid-1980s in the production centers of historical knowledge began to emerge a historiographical perspective on the War of Paraguay which became generically known as ‘neo revisionism’. This perspective brought together several academic researches with varied focuses on the platinum conflict, but that present some common characteristics, such as: (1) they are academic researches based on abundant historical documentation; (2) they question the British participation and responsibility in the conflict; (3) they question Paraguay's economic development; and (4) they present regional conflicts and interests as reasons for the War56.

Nadai and Neves (1997, p. 229), possibly inspired by some elements of this last approach, made clear that the Empire of Brazil insisted on the annihilation of Paraguay: “The War [of Paraguay] was almost decided in favor of the allies, but the fight continued until 1870. Allies, especially Brazilian ones, insisted in annihilation of Paraguay and the elimination of Solano López”.

Cotrim (1999, p. 206), author of the last Brazilian book analyzed pointed that initially there were ‘many interests’ of the Brazilian Empire over the Prata region. However, the author made three of them evident: (1) “Guaranteeing the right of navigation on the River Plate [...]”, only access, at the time, to the province of Mato Grosso; (2) “Prevent groups of people from Uruguay from invading Brazilian borders and attacking farms in Rio Grande do Sul” (Cotrim, 1999, p. 207) and (3) Prevent Argentina from annexing Uruguay. For the author, “[...] from the union between Oribe and Rosas appeared a political line which contradicted Brazilian interests in the Prata region [...]”. Wherefore, “Brazil resolved intervene militarily in the Platinum region to preserve its economic and political interests” (Cotrim, 1999, p. 207). According to the author, Brazilian interests were based on prevent that: (1) Rosas annexing Uruguay and (2) the borders of Rio Grande were invaded by Uruguayans, source of the conflicts with farmers from Rio Grande do Sul.

When dealing with the ‘War against Aguirre’, Cotrim (1999) affirmed that Brazil intervened in Uruguay because it saw its ‘interests harmed’. He still affirmed that the Empire tried to resolve the problem diplomatically but “Aguirre, who belonged to the White Party (Partido Blanco), paid little attention to requests made by the Brazilian government [...]”, so, when “[...] understood that the requirements will not be attended, Brazilian imperial government resolved declaring war on Uruguay” (Cotrim, 1999, p. 208).

In Cotrim (1999), whose work is from the late 1990s decade, we may observe arguments similar to those made in late 19th century manuals, which prevailed in numerous other books along the Twentieth Century, as we could demonstrate in this text. Consciously or unconsciously, Cotrim still highlights that “[...] Brazil resolved military intervene in the Platinum region to preserve its economic and political interests” (Cotrim, 1999, p. 207), and finishes for soften Brazilian interventions in Platinum countries as ‘protector’ of the Independence of Uruguay and he defends that the Empire only had used force because its requirements were not attended, given the impression that Brazil would be ‘impelled’ to intervene.

It is important to detach that with the critic above, we are not questioning the author's positions regarding the theme, because we did not take the objective to point supposed correct or wrong ways to deal with the issue. However, we mark that even with differences between them, some arguments regarding Brazil's performance in the Platinum region produced even at the end of the nineteenth century would survive until the late twentieth century in History of Brazil textbooks.

Some considerations

National policies for Platinum region advanced in the sense of create a block of countries which based their interests originally in the economic-political nature that promoted an agenda which was so-called Mercosul. This continental articulation did not achieve a continuous and lineal development because of the instability that sometimes looms the region. Since the political destabilization that countries like Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay and, especially Brazil met from the beginning of 2010s decade, bases of a great South American agreement on common goals has suffered tremors. Studies and research that may understand the historical development of these countries and the relations between them, as the one that proposes to spread the present thematic dossier might help to enlarge the understanding on advances and impasses, limits and possibilities to construct a Latin American unity dreamed of by so many. The school and everything that involves the institution (professors, students, students’ families, educational managers, knowledge, curricula, textbooks, educational policies) need to be studied without losing sight that they are part of a broader issue, the construction of a just, inclusive, democratic America, and based on the respect to the cultural diversity. With this text, we searched for identify and characterize approaches in History textbooks on the Brazilian imperialism issue in the Platinum region in the Nineteenth Century second half through a large temporal clipping, understanding how each time constructed the knowledge on this historical event for the school. In the analysis performed, we could characterize 3 set of authors. The first one formed by Macedo (1905), Maia (1886), Rocha Pombo (undated), Silva (1969), Borges Hermida (1972), and Souto Maior (1965); a second one composed by Ribeiro (1914) and Coutto (1920); and a third one which has as integrant Alencar, Ramalho and Ribeiro (1979), Koshiba and Pereira (1987), Nadai and Neves (1997), Piletti (1987) and Cotrim (1999).

In the first set of authors prevailed the idea of inevitability of Brazilian interventions in the platinum region to consciously or unconsciously justify or soften the imperial government's attitudes towards the neighboring countries of the Southern Cone. For the authors previously mentioned, Brazil was presented as guarantor of peace in Prata and as protector of Uruguay's independence. It is important remember that this was a current discourse at that time, propagated by nationalist historiography.

In the second set of authors, who wrote their Works in the early Twentieth Century, certain ambivalence was demonstrated, because at the same time that they pointed to an inevitability of Brazilian interventions in Prata, they referred to it as unjustifiable. They condemned Empire performance, especially regarding the War of Paraguay, but they did not fail to have a negative view of neighboring nations and peoples.

A nationalist historiography prevailed, in a hegemonic way, in the writing period of this second set of authors, especially regarding the Brazilian performance in the Southern Cone. At the same time that they carried out a transgression of the hegemonic conception regarding the participation of Brazil in the War of Paraguay and the interferences in neighboring countries, they used certain explanatory elements traditionally accepted and current at the time of production of the works.

In the late 1970s, we could identify a change in the analysis of Brazilian imperialism in the platinum region in the textbooks that was part of the third set of books. Most authors who wrote History textbooks in this period would intentionally produce a history to escape heroic and nationalist narratives. A movement towards the writing of a school history that aimed to emphasize collectivities, with strong influences from social history and Marxism.

This third set of authors detached the internal contradictions and conflicts and regional rivalries in Prata or associated Brazilian action towards their neighbors as an influence of British imperialism and capitalism in the region, highlighting the economic interests of the last one. Despite the changes that took place in the writing of school history since the 1970s decade, some narratives remained in school books throughout the Twentieth Century, like the one in which the Brazilian Empire was pointed as the guarantor of Uruguay's independence.

REFERENCES

Abud, K. M. (1997). Currículos de história e políticas públicas: os programas de história do Brasil na escola secundária. In C. Bittencourt (Org.), O saber histórico na sala de aula (p. 28-41). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Abud, K. M. (1998). Formação da alma e do caráter nacional: o ensino de história na era Vargas. Revista Brasileira de História, 18(36), 103-113. [ Links ]

Abud, K. M. (2011). A guardiã das tradições: a história e seu código disciplinar. Educar em Revista, 42, 163-172. [ Links ]

Bandeira, L. A. M. (1982). O papel do Brasil na Bacia do Prata (da colonização ao Império) (Tese de Doutorado em Ciência Política). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (1977). Análise de conteúdo (Luis Antero Reto e Augusto Pinheiro, trad.). Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Batista, A. A. G. (2005b). A política de livros escolares no Brasil. In MEC/TV Escola. Materiais didáticos: escolha e uso (Boletim, 14, p. 12-24). Brasília, DF. [ Links ]

Batista, A. A. G., & Rojo, R. (2005). Livros escolares no Brasil: a produção científica. In M. G. C. Val & B. Marcuschi (Orgs.), Livros didáticos de língua portuguesa: letramento, inclusão e cidadania (p.13-45). Belo Horizonte: Ceale. [ Links ]

Bittencourt, C. M. F. (1993). Livro didático e conhecimento histórico: uma história do saber escolar (Tese de Doutorado em História Social). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Bittencourt, C. (2008). Livro didático e saber escolar 1810-1910. Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Bittencourt, C. (1997). Livro didático entre textos e imagens. In C. Bittencourt (Org.), O saber histórico na sala de aula . (p. 69-90). São Paulo: Contexto. [ Links ]

Bittencourt, C. (1990). Pátria, civilização e trabalho: o ensino de história nas escolas paulistas - 1917-1939 (1a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Bobbio, N., Matteucci, N., & Pasquino, G. Dicionário de política (11a ed., Vol. I). Brasília, DF: Editora da UNB. [ Links ]

Bonazzi, M., & Eco, U. (1980). Mentiras que parecem verdades. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Chevallard, Y. (1998). La transposición didáctica: del saber sábio al saber enseñado. Buenos Aires, AR: AIQUE Grupo Editorial. [ Links ]

Choppin, A. (2004). História dos livros e das edições didáticas: sobre o estado da arte. Educação e Pesquisa, 30(3), 549-566. [ Links ]

Choppin, A. (2002). O historiador e o livro escolar. História da Educação, (11), 5-24. [ Links ]

Cerri, L. F. (2001). Os conceitos de consciência histórica e os desafios da Didática da História. Revista de História Regional, 6(2), 93-112. [ Links ]

Chiavenatto, J. J. (1983). Genocídio americano: a Guerra do Paraguai (18a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Doratioto, F. (1991). A Guerra do Paraguai: 2ª visão. São Paulo, SP: Brasiliense . [ Links ]

Doratioto, F. (2002). Maldita guerra. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Ferraro, J. R. (2013). Compêndio de história do Brasil, de Borges Hermida: produção, editoração e circulação. In Anais do 27º Simpósio Nacional de História (p. 1-16). Natal, RN. [ Links ]

Freitag, B. et al. (1987). O estado da arte do livro didático no Brasil. Brasília, DF: INEP. [ Links ]

Freitag, B. et al. (1989). O livro didático em questão. São Paulo: Cortez. [ Links ]

Gasparello, A. M. (2004). Construtores de identidades: a pedagogia da nação nos livros didáticos da escola secundária brasileira. São Paulo, SP: Iglu. [ Links ]

Goodson, Y. (1997). A construção social do currículo. Lisboa, PT: Educa. [ Links ]

Grisi, R. (1951). O ensino da leitura: o método e a cartilha. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, 16(43). [ Links ]

Lins, O. Problemas inculturais brasileiros. Recife, PE: Edufpe, 2018. [ Links ]

Magalhães, M. S. (2011). A construção de um cânone republicano: a escrita da história escolar na virada do século XIX para o XX. In Anais do XXVI Simpósio Nacional de História - ANPUH (p. 1-15) São Paulo, SP. Disponível em: https://anpuh.org.br/index.php/documentos/anais/category-items/1-anais-simposios-anpuh/32-snh26 [ Links ]

Menezes, A. M. (1998). Guerra do Paraguai: como construímos o conflito. São Paulo, SP: Contexto . [ Links ]

Menezes, A. M. (2012). A guerra é nossa: a Inglaterra não provocou a Guerra do Paraguai. São Paulo, SP: Contexto . [ Links ]

Menezes, A. M. (1982). Solano Lopez, o Partido Blanco e a Guerra do Paraguai: análise da influência diplomática oriental sobre o Paraguai, 1862-1864 (Dissertação de Mestrado em História da América Latina). Tulane University, Estados Unidos. [ Links ]

Nadai, E. (1992-1993). O ensino de História no Brasil: trajetória e perspectiva. Revista Brasileira de História , 13(25/26), 143-162. [ Links ]

Nosella, M. L. C. (1976). As belas mentiras: a ideologia subjacente aos textos didáticos. São Paulo: Cortez . [ Links ]

Pinto Jr., A. (2010). Professor Joaquim Silva, um autor da história ensinada do Brasil: livros didáticos e educação moderna dos sentidos (1940 -1951) (Tese de Doutoramento em Educação). Unicamp, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Pomer, L. (1980). A Guerra do Paraguai: a grande tragédia rio-platense (Yara Peres, trad.). São Paulo, SP: Global. [ Links ]

Rüsen, Jörn. (2006). Historiografia comparativa intercultural. In J. Malerba (Org.), A história escrita: teoria e história da historiografia (Jurandir Malerba, trad., p. 115-137). São Paulo, SP: Contexto . [ Links ]

Salles, R. (1990). Guerra do Paraguai: escravidão e cidadania na formação do exército (1a ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Squinelo, A. P. (2002). A Guerra do Paraguai, essa desconhecida... ensino, memória e história de um conflito secular. Campo Grande, MS: UCDB. [ Links ]

Squinelo, A. P. (2016a). 150 anos após - a Guerra do Paraguai: entreolhares do Brasil, Paraguai, Argentina e Uruguai (1a ed., Vol. 1). Campo Grande, MS: Ed. UFMS. [ Links ]

Squinelo, A. P. (2016b). 150 anos após: a Guerra do Paraguai: entreolhares do Brasil, Paraguai, Argentina e Uruguai (1a ed., Vol. 2). Campo Grande, MS: Ed. UFMS . [ Links ]

Squinelo, A. P., & Telesca, I. (Org.). (2009). 150 após - A Guerra do Paraguai:Entreolhares do Brasil, Paraguai, Argentina e Uruguai (1a ed., Vol. 3). Campo Grande, MS: Life. [ Links ]

Toral, A. (2001). Imagens em desordem: a iconografia da Guerra do Paraguai (1864- 1870). São Paulo, SP: Humanitas. [ Links ]

Unicamp. (1989). O que sabemos sobre o livro didático? Catálogo analítico. Campinas, SP: Editora da Unicamp. [ Links ]

Vechia, A., & Lorenz, K. (1998). Programa de ensino da escola secundária brasileira - 1850-1951. Curitiba, PR: Edição dos Organizadores. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Alencar Filho, F. R., Ramalho, L. C., & Ribeiro, M. T. (1979). História da sociedade brasileira. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Ao Livro Técnico. [ Links ]

Borges Hermida, A. J. Compêndio de história do Brasil (57a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Companhia Editora Nacional. [ Links ]

Cotrim, G. (1999). História e consciência do Brasil (7a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Saraiva. [ Links ]

Coutto, P. (1920). Ponto da História do Brasil (2a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Jacinto Ribeiro dos Santos Editor. [ Links ]

Koshiba, L., & Pereira, D. M. (1987). História do Brasil (5a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Atual. [ Links ]

Macedo, J. M. (1905). Lições de História do Brasil para uso das escolas de instrucção primária. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Livraria Garnier. [ Links ]

Maia, L. Q. M. (1886). Lições de história do Brasil: proferidas no internato do Imperial Colégio de Pedro II (2a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Garnier. [ Links ]

Nadai, E., & Neves, J. (1997). História do Brasil (19a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Saraiva . [ Links ]

Piletti, N. (1987). História do Brasil (6a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Ática. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, J. (1914). História do Brasil: curso superior (5a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Francisco Alves. [ Links ]

Rocha Pombo, J. F. (n.d.). História do Brasil. São Paulo, SP: Editora Companhia Melhoramentos. [ Links ]

Silva, J. (1969). História do Brasil : para o curso médio - primeira e segunda séries (22a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Companhia Editora Nacional . [ Links ]

Souto Maior, A. (1965 ). História do Brasil : para o curso colegial. São Paulo, SP: Companhia Editora Nacional . [ Links ]

28The work by Batista and Rojo (2005) is based on two other important researches, also of type state of knowledge: one of them by Freitag et al. (1987) and the other by Unicamp (1989).

29Na example may be found more recently in collective Works under by organization of professors Margarida Dias de Oliveira and Maria Inês Sucupira Stamatto, both workers of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. These works deal with relations among teaching history, didactic books, and the National Textbook Program (PNLD in its Brazilian Portuguese acronym). Several authors of these books have acted as evaluators for the PNLD in the History field, and they could deal with the most various matters regarding the didactic works.

30Consulted edition published in 1905, according to the Table 01.

31We understand historical awareness as “[...] a phenomenon inherent to the human existence” (Cerri, 2001, p. 96), an ‘anthropological universal’ (Rüsen, 2006). We pondered that any considering regarding the defense that there are people or Peoples who do not have historical awareness may generate the old dichotomy between civilization and barbarism. It is where the use of the expression ‘meaning assignment of historical consciousness’ instead of ‘production or construction of historical consciousness’ comes from.

32Works with numerous editions may be representative of a relative acceptance in the school setting of textbooks, and therefore of this participation for years in a row in the process of attributing meaning to ‘historical awareness’ of several Brazilian students and professors.

33Numerous selected books had professor at the Imperial School Pedro II as authors, and/or were members of the Brazilian Historical and Geographic Institute (IHGB).

34We preferred use a large temporal clipping by understand the school knowledge in the curriculum constituted as a historical and social construction (Goodson, 1997), and thus, when we observed the clipping established, we could better notice out the narrative construction around Brazilian imperialism in Latin American South Cone (19th Century) in History of Brazil textbooks selected for the research, and glimpsing how each time period constructed the knowledge on this event for the school.

35To construct the analysis category highlighted we used the categorical thematic content analysis technique according to Bardin (1977).

36According to Bittencourt (2008), the first edition of the work by Macedo is of 1861. The edition examined is of 1905.

37For Gasparello (2004), the first edition of the work by Maia was published probably in 1880 by the editor Dias da Silva Júnior. The edition examined is of 1886.

38There is no indication of year or edition of the work but the book’s presentation by the own author is titled This little History (Esta pequena historia) is dated 1918. There is still the author’s authorization allowing the spelling that suits the publisher dated 1925.

39 Arnaldo Pinto Jr. (2010) affirms that information on Joaquim Silva are extremely scarce. Silva had numerous didactic Works on History published by Companhia Editora Nacional since at least 1940s decade, and he was together Borges Hermida the most used author in Brazil in the years 1960s and 1970s.

40According to Ferraro (2013, p. 8), the Works by Borges Hermida were edited by Companhia Editora Nacional between 1959 and 1989, “[...] with varied titles of History of Brazil and General History, being constant in their periodicity”.

41Souto Maior started his work of authorship of textbooks on History in the 1960s, by Editora Nacional. It is possible that the work analyzed would be the first edition.

42The last question of a questionnaire in the book by Silva (1969, p. 205, emphasis added) quite reinforces the idea that Brazil was ‘forced’ to intervene in the war (against Uruguay and Argentina): “Why was Brazil ‘forced to intervene in the war’?”.

44 Souto Maior (1965) still detached that, even in a conflict with Uruguay, there was the interest by Brazilian government to preserve the independence of that country. For the author mentioned, Saraiva assigned a declaration in Buenos Aires that the independence of the Uruguayan state would be respected. The author still highlighted that another agreement has been assigned, this a secret one, with Venâncio Flores.

46Rocha Pombo gave emphasis to the possibility to grant the Paraguayan people the power to choose by vote who they would be the representatives in the Provisional Government Board. However, we detach that before such situation that the country was facing, we could ask: who would be the people who could vote? What social segments did they belong to? And maybe the more important questions: Who would be the candidates? Were they figures that the Empire did not support?

47This fruitful and creative notion has in Yves Chevallard, professor at IUFM, Aix-Marseille, France, one of the authors who systematize it. According to Chevallard, the knowledge taught at school proceeds from a qualitative modification of academic knowledge, by which it is possible to denaturalize it order to be understood by the student.

48 Marcelo de Souza Magalhães (2011) supports the first edition of Ribeiro’s work was published in 1914.

49According to Gasparello (2004), the first edition of ‘Point of the history of Brazil’, by Pedro do Coutto, was published in 1918. We examined the edition of 1920.

50The first editions of the books by Alencar Filho, Ramalho and Ribeiro, and by Koshiba and Pereira were published in the late 1970s decade.

51The first editions of the Works by Nadai and Neves (1997), and by Piletti (1987) were published in the early 1980s decade, with numerous re-editions in 1990s decade, while those by Cotrim were published in the early 1990s decade.

52 Alencar Filho, Ramalho and Ribeiro (1979, p. 168) also performed the same analogy.

54For Koshiba and Pereira (1987, p. 220), Brazilian imperialism in Platinum region context appears contrasting another imperialist force: Argentine. For these authors, Brazilian interests in Prata region “[...] were so vital that, since D. João VI, an interventionist policy was inaugurated, culminating in the annexation of Cisplatin - future Uruguay -, which remained as Brazilian province until 1827”.

55This current of thought had place mainly between the 1960s and 1980s decades, and it had as detached authors Pomer (1980) and Chiavenato (1983).

56Here we highlight the Works by the professors Luiz Alberto Moniz Bandeira (1982), Alfredo da Mota Menezes (1982, 1998, 2012), Ricardo Salles (1990), Francisco Doratioto (1991, 2002), André Toral (2001) and Ana Paula Squinelo (2002), only to register some examples. At the present time, an important collection serves to demarcate this rethinking the War of Paraguay, more than 150 years after the beginning of the conflict, organized by the professor Ana Paula Squinelo. The collection brings together experts in the theme from the four countries involved in the conflict and currently counts with three volumes. For more information: Squinelo (2016a; 2016b) and Squinelo and Telesca (2019).

62How to cite this article: Salles, A. M., & Batista, J., Neto. Brazilian History textbooks approaches about Brazil’s presence in the Latin American Southern Cone, in the nineteenth century. (2020). Brazilian Journal of History of Education 20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e122 Brazilian History textbooks approaches about Brazil’s presence in the Latin American Southern Cone, in the nineteenth century (CC-BY 4).

1O trabalho de Batista e Rojo (2005) apoia-se em duas outras pesquisas de fôlego, também do tipo estado do conhecimento, a saber: Freitag et al. (1987) e Unicamp (1989).

2Exemplo disso pode ser encontrado, mais recentemente, em diversas obras coletivas, sob a organização das professoras Margarida Dias de Oliveira e Maria Inês Sucupira Stamatto, ambas da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Essas obras tratam das relações entre ensino de História, livros didáticos e o Programa Nacional do Livro Didático (PNLD). Os diversos autores dessas obras atuaram também como avaliadores do PNLD para a área de História e puderam tratar dos mais diversos assuntos referentes às obras didáticas.

3A edição consultada data de 1905, conforme Quadro 01.

4Entendemos consciência histórica como “[...] um fenômeno inerente à existência humana” (Cerri, 2001, p. 96), um ‘universal antropológico’ (Rüsen, 2006). Ponderamos que qualquer consideração em relação à defesa de que existem pessoas ou povos que não possuem consciência histórica possa gerar a velha dicotomia entre civilização e barbárie. Daí a utilização da expressão ‘atribuição de sentido da consciência histórica’ ao invés de ‘produção ou construção de consciência histórica’.

5Obras com inúmeras edições podem ser representativas de uma relativa aceitação no cenário escolar de livros didáticos e, por conseguinte, da sua participação, por anos seguidos, no processo de atribuição de sentido da ‘consciência histórica’ de muitos estudantes e professores brasileiros.

6Vários dos livros selecionados por nós tiveram como autores professores do Colégio Pedro II e/ou foram membros do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro (IHGB).

7Preferimos adotar um longo recorte temporal por entendermos que o conhecimento escolar presente no currículo se constitui em uma construção histórica e social (Goodson, 1997) e, nesse sentido, ao observarmos o recorte estabelecido, conseguiríamos perceber melhor a construção narrativa em torno do imperialismo brasileiro no Cone Sul latino-americano (século XIX) nos livros didáticos de História do Brasil selecionados para a pesquisa e vislumbrar como cada época construiu o conhecimento sobre esse evento histórico para a escola.

8Para construir a categoria de análise em destaque, utilizamos a técnica de análise temática categorial de conteúdo conforme preconiza Bardin (1977).

9Segundo Bittencourt (2008), a primeira edição da obra de Macedo data de 1861. A edição examinada é de 1905.

10De acordo com Gasparello (2004), a primeira edição da obra de Maia foi publicada provavelmente em 1880 pela editora Dias da Silva Júnior. A edição examinada data de 1886.

11Não há a indicação do ano ou da edição da obra, contudo a apresentação do livro, escrita pelo próprio autor e intitulada Esta pequena historia, data de 1918. Há, ainda, a autorização do autor permitindo a utilização da grafia que conviesse a editora, que data de 1925.

12 Arnaldo Pinto Jr. (2010) afirma que as informações sobre Joaquim Silva são extremamente escassas. Silva teve diversas obras didáticas de História publicadas pela Companhia Editora Nacional desde pelo menos a década de 1940 e foi, juntamente com Borges Hermida, o autor mais utilizado no Brasil nos anos de 1960 e 1970.

13Segundo Ferraro (2013, p. 8), as obras de Borges Hermida foram editadas pela Companhia Editora Nacional entre 1959 e 1989, “[...] com títulos variados de História do Brasil e História Geral, sendo constantes em sua periodicidade”.

14Souto Maior iniciou seu trabalho de autoria de livros didáticos sobre História na década de 1960, pela editora Nacional. É possível que a obra em análise seja a primeira edição.

15A última pergunta de um questionário constante da obra de Silva (1969, p. 205, grifo nosso) reforça bem a ideia de que o Brasil fora ‘forçado’ a intervir na guerra (contra Uruguai e Argentina): “Por que foi o Brasil ‘forçado a intervir na guerra’?”.

16 Souto Maior (1965) destacou ainda que, mesmo em conflito com o Uruguai, havia o interesse, por parte do governo brasileiro, na preservação da independência daquele país. Para o autor mencionado, Saraiva assinou em Buenos Aires uma declaração informando que a independência do Estado uruguaio seria respeitada. O autor destacou, ainda, que foi assinado outro acordo, este secreto, com Venâncio Flores.

18Rocha Pombo deu ênfase a possibilidade de ser concedido ao povo paraguaio o poder de escolha pelo voto quais seriam os representantes na Junta do Governo Provisório. Contudo, destacaríamos que diante de tal situação que se encontrava o país, poderíamos questionar: quais seriam as pessoas que poderiam votar? A que segmentos sociais eles pertenciam? E, talvez, o mais importante: Quem seriam os votados? Seriam figuras que o Império não apoiasse?

19Essa noção fecunda e criativa tem em Yves Chevallard, professor do IUFM de Aix-Marseille, França, um dos sistematizadores. Para Chevallard, o saber que se ensina na escola procede de uma modificação qualitativa do saber acadêmico, pela qual se chega a desnaturalizá-lo com o fim de que seja compreendido pelo aluno.

20 Marcelo de Souza Magalhães (2011) sustenta que a primeira edição do livro de Ribeiro data de 1900. Examinamos a edição de 1914.

21Segundo Gasparello (2004), a primeira edição de ‘Pontos da História do Brasil’, de Pedro do Coutto, foi publicada em 1918. Examinamos a edição de 1920.

22As primeiras edições dos livros de Alencar Filho, Ramalho e Ribeiro e de Koshiba e Pereira datam do final da década de 1970.

23As primeiras edições das obras de Nadai e Neves (1997) e de Piletti (1987) chegaram ao público no início da década de 1980, com inúmeras reedições nas décadas de 1990, enquanto as de Cotrim foram publicadas no início da década de 1990.

24 Alencar Filho, Ramalho e Ribeiro (1979, p. 168) também realizaram a mesma analogia.

25Em Koshiba e Pereira (1987, p. 220), o imperialismo brasileiro no contexto da região Platina aparece contraposto a outra força imperialista, a Argentina. Para esses autores, os interesses brasileiros na região do Prata “[...] eram tão vitais que, desde D. João VI, inaugurou-se uma política intervencionista, culminando na anexação da Cisplatina - futuro Uruguai -, que permaneceu como província do Brasil até 1827”.

26Essa corrente de pensamento teve espaço entre as décadas de 1960 a 1980, sobretudo, e tiveram como autores destacados Pomer (1980) e Chiavenato (1983).

27Destacamos aqui as obras dos professores Luiz Alberto Moniz Bandeira (1982), Alfredo da Mota Menezes (1982, 1998, 2012), Ricardo Salles (1990), Francisco Doratioto (1991, 2002), André Toral (2001) e Ana Paula Squinelo (2002), apenas para registrar alguns exemplos. No momento atual, uma importante coleção que serve para demarcar esse repensar sobre a Guerra do Paraguai, mais de 150 anos após o início do conflito, é a organizada pela professora Ana Paula Squinelo. A coleção reúne especialistas na temática dos quatro países envolvidos no conflito e conta atualmente com três volumes. Ver: Squinelo (2016a; 2016b) e Squinelo e Telesca (2019).

Received: May 29, 2020; Accepted: June 30, 2020

texto em

texto em