Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1519-5902versão On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.20 Maringá 2020 Epub 01-Ago-2020

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e126

DOSIER

‘For lighting the past’: books and education in the context of the fiftieth anniversary of the Independence (Brazilian capital, 1870s)

1Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil.

In this study, we thought about ways to approach the country's political emancipation. We questioned some ‘remains’, places of memories: the books, responsible for the intervention, education, constitution and legitimation of certain representations about Independence. These are: Ideias por coordenar a respeito da emancipação by Maria Durocher (1871a) and A independencia e o Imperio do Brazil by Alexandre Moraes (1877). We concluded the analysis by understanding the distinct objectives of each work and their similarities, such as the fact that they relate the incompatibility between independence and slavery. In the educational aspect, Durocher defended formal education while Mello Moraes was a true narrative based on facts and documents, which would constitute the history for the formation of youth.

Keywords: memory; history of education; books; political emancipation

Neste estudo pensamos formas de abordar a emancipação política do país. Interrogamos alguns ‘restos’, lugares de memórias: os livros, responsáveis pela intervenção, educação, constituição e legitimação de determinadas representações acerca da Independência. Tratam-se de: Ideias por coordenar a respeito da emancipação de Maria Durocher (1871a) e A independencia e o Imperio do Brazil de Alexandre Moraes (1877). Concluímos a análise entendendo os objetivos distintos de cada obra e suas semelhanças, como o fato de relacionarem a incompatibilidade da independência com a escravidão. No aspecto educacional, Durocher defendia a educação formal, enquanto Mello Moraes uma narrativa verdadeira baseada em fatos e documentos, que se constituiria a história para formação da juventude.

Palavras-chave: memória; história da educação; livros; emancipação política

En este estudio pensamos en formas de abordar la emancipación política del país. Cuestionamos algunos ‘restos’, lugares de recuerdos: los libros, responsables de la intervención, educación, constitución y legitimación de ciertas representaciones sobre la Independencia. Estas son: Ideias por coordenar a respeito da emancipação de Maria Durocher (1871a) y A independencia e o Imperio do Brazil de Alexandre Moraes (1877). Concluimos el análisis comprendiendo los distintos objetivos de cada trabajo y sus similitudes, como el hecho de que relacionan la incompatibilidad de la independencia con la esclavitud. En el aspecto educativo, Durocher defendió la educación formal, mientras que Mello Moares era una verdadera narrativa basada en hechos y documentos, que constituiría la historia para la formación de la juventud.

Palabras clave: memoria; historia de la educación; libros; emancipación política

Introduction

Investigating the event of emancipation in Brazil, in 1822, is a task, while investigating words and representations erected later about it, is another task, since they are memory-building exercises. Michael Pollak announces how ‘potentially problematic’ the character of memories is, understanding that one does not try to deal with social facts as ‘things’, but to analyze how social facts become ‘things’, how and by whom they are crystallized and endowed with duration and stability (Pollak, 1989).

The theme of Brazil’s independence has become more current due to its bicentenary (2022). It is natural that, for this reason, researchers from different areas turn to wonder, question, reveal or denaturalize certain perspectives that time, subjects, history, institutions forged about it, also see and review certain sources, evidence and data.

Among the contemporaries of the nineteenth century, there was even an interest in leaving the memory of independence alive to criticize it or make it emerge as a milestone in the birth of the Brazilian nation. In many ways, emancipation was announced, studied, spoken, criticized, celebrated. The general and specialized press circulated, especially in September editions, its news, notes and ideas. Some newspapers were even created to address political issues linked to emancipation, making reference to the date in the title itself, such as Sete de Setembro (Alagoas, 1876), O Sete de Setembro (São Paulo, 1865), 7 de Setembro (Rio de Janeiro, 1859) and O Sete de Setembro (Rio de Janeiro, 1833), among others.

Likewise, many associations were created with the specific function of celebrating the birthdays of September 7. The commemorative societies, thus identified, were numerous, but their ways of celebrating were always very similar: fireworks, music band, civic parade, façade decoration, etc. Among them, we highlight the Sociedade Comemorativa da Independência do Império (1869-1888), Sociedade Independência (1876), Sociedade Independência (1863), Sociedade dos Cavaleiros do Ipiranga (1853), Sociedade Independência Brasileira (1857), Sociedade Festival Sete de Setembro (1859), Sociedade Independência Nacional (1856), Sociedade Conservadora Sete de Setembro (1872), Sociedade Defensora da Liberdade e Independência Nacional (1831).

The memories and representations forged from such investments were diversified, as it should be, the result of tensions and clashes involved in the process of understanding and making understand a certain angle of the colony’s political emancipation, its protagonists, political actions, scenarios, historical dates. Studying the collective memories strongly constituted, like the national memory, implies preliminarily in the analysis of its function, since it is integrated with the attempts to define and reinforce feelings of belonging (Pollak, 1989).

This time, places are forged where memory crystallizes and takes refuge from a certain past, definitely dead. As Pierre Nora teaches, history is exactly what our societies condemned to oblivion make of the past. For him, the places of memory are, above all, remains, the extreme form where a commemorative conscience survives in a story that calls it. History exists because there is no spontaneous memory, places of memory are born and live because archives are created, birthdays are held, celebrations are organized, funeral praises are pronounced, “[...] operations that are not natural” (Nora, 1993, p. 12-13).

In the set of so many and varied investments related to the theme of Brazilian Independence, this approach with which we operate is interested in interrogating some of these ‘remains’, places of memories, specific devices: books and their authors, responsible for intervention, education, constitution and formalization of certain representations about Independence and its ephemeris, such as its 50th anniversary (1872), completed in the decade of elaboration and publication of such works. It is, therefore, the analysis of the books: Ideias por coordenar a respeito da emancipação by Maria Josefina Matildes Durocher (1871a) and A independencia e o Imperio do Brazil by Alexandre José Mello de Moraes (1877)16.

The words written by these authors are added to a set of other initiatives elaborated in that context and with similar objectives, for example: Recordações da vida patriótica by Antonio Pereira Rebouças (1879); Analyse e commentario da Constituição politica do Imperio do Brazil, ou, theoria e pratica do governo constitucional brasileiro by Joaquim Rodrigues Souza (1867); O sete de setembro de 1857: tributo a memoria dos heroes da independencia do imperio do Brasil (1857); Relação dos cidadãos que tomaram parte no governo do Brazil no periodo de março de 1808 a 15 de novembro de 1889 by Miguel Archanjo Galvão (1894); A Marinha de guerra do Brasil na lucta da independencia: apontamentos para a historia (1880); Historia da fundação do imperio brasileiro by João Manuel Pereira da Silva (1864).

The aforementioned list and the documentary series selected here (Moraes and Durocher) show how the theme has become an object of interest and concern for different subjects, enrolled in different fields of knowledge. All of them, possibly, with a common goal of making interpretations of a certain past (the political emancipation of Brazil in 1822) appear in the present (the 1870s). Pierre Nora draws our attention to this: “The national definition of the present imperiously called its justification for the illumination of the past” (Nora, 1993, p. 11).

In this sense, the books were analyzed from their content, form, themes, approach, narrative and articulations established with Independence and education, highlighting what kind of memories and angles they sought to erect and legitimize. In the same way, it is important to highlight the purposes explained in each work, one of which, by Durocher, is purposeful, with political projects for an independent and enslaver Brazil, having been dedicated to the Assembly of Deputies. The other book, by Moraes, constitutes a historical review, an acid criticism of the whole set of elements instituted around Brazilian Independence (its heroes and characters, its setting, its reasons, its continuities).17

Ideas to coordinate regarding the emancipation (1871)

When thinking about Brazil’s independence and the many events that made the liberation from the Colony peculiar, we can observe the continuation of a monarchy, the government by a Portuguese representative and the permanence of slavery. The latter, a brand that plagued the then Imperial Brazil until the eve of the beginning of the republican regime, became one of the most significant targets of criticism to the government and Independence, especially on its anniversaries where the date was celebrated, sometimes occurring, the release of enslaved people as a sign of celebration for the ephemeris. Examples of this are some newspaper notes, as illustrated in figure 1 below:

Gazeta reported that the Atheneu Cearense school promoted celebrations for independence by freeing a slave woman (totaling 13 in an unmentioned period). Likewise, the City Hall appeared on the pages of O Mequetrefe due to the way it proceeded with the celebrations on that 63rd anniversary of Brazil’s political emancipation: handing manumission letters to many enslaved people. The text argued:

Never has so much been written about the great day of our independence as this year [...] However, the party this year had this better than the others: the Municipal Chamber, assisted by the municipalities, granted a hundred and so many manumission letters. I could not find Edility a more worthy way to commemorate the independence of our dear country (O Mequetrefe, 1885, p. 2)

The issue did not go unnoticed during the period, having been the subject of debates by various groups and citizens and the target of palliative measures18 until the well-known Golden Law of 1888 and later. Among the challenges of the Liberal Party and the actions of the abolitionist movement in the arts, creating associations, the search for foreign allies, initiatives in public institutions, press support, civil disobedience and public opinion persuasion ceremonies (Alonso, 2015) included common citizens like the French midwife Maria Josefina, who in the 1870s exposed her ideas about the incompatibility between independent nation and slavery.

Maria Josephina Mathilde Durocher, or as she used to introduce herself, Madame Durocher “Midwife from the medical school in Rio de Janeiro, midwife at the imperial house, former midwife to His Highness and late Princess D. Leopoldina, Duchess of Saxe Coburgo and Gotha, and honorary member of the imperial academy of medicine in Rio de Janeiro” (Durocher, 1871a, p. 1)19, was one of the 19th century women concerned with the political and social events of her time and, therefore, sought to intervene in the direction of the country.

She supported the thesis that in an independent country there was no room for slavery, worked in the slavery cause by offering her services in the maternity ward or birth ward of the Casa de Saúde Nossa Senhora da Ajuda (Rua da Alfandega, 106) for enslaved women offering including the necessary clothes (Nicolau, 2018). In 1871, she wrote the book Ideias por coordenar a’ respeito da emancipação, dedicated to the baron of Cotegipe as a friend and destined to the assembly so that her reflections ‘could be heard’. She justified her writing by saying “[...] judge me equally as a Brazilian citizen with the right to express my ideas in this regard” (Durocher, 1871a, p. 5), as shown in figure 2:

Fonte: Biblioteca do Senado Federal

Figure 2 Cover of the book Ideias por coordenar a’ respeito da emancipação

The author of the book was born in 1809, in Nancy, France, but at about seven years old she came to Brazil with her mother Anne Nicolli Colette Durocher20. The two French women were in the migratory contingent of this country that came to Brazil in the first decades of the 19th century, between 1808 and 1820, a reality that has intensified since 1850 with the urbanization improvements of the Court and the increase of capital, generating job opportunities (Nicolau, 2018). And so, the single mother (about 26 years old) and with a declared profession of florist and seamstress, and her young daughter, after spending five months traveling, arrived at the Court in March 1816 (Mott, 1994).

Maria Durocher’s education took place in a private school in Brazil, learning languages like German and English. She worked in her mother’s trade, in addition to working as a florist and dressmaker, taking over the establishment of the family after her mother’s death in 1829. At this time, single, with 23 years and two children, she decided to become Madame Durocher starting private classes on childbirth with a physician and, later, on the course at the Imperial Academy of Medicine in 1832, having been the first woman to enroll. Upon completing the birth course, she was the first graduate in Brazil (Mott, 1994).

Madame Durocher, whose image is shown in figure 3 above, was criticized for keeping her birthing house in Freguesia do Sacramento next to her residence, which is why she received warnings from the government, with the risk of having her specialist license revoked (Nicolau, 2018). It seems, however, that such criticisms did not discourage the woman who, “[...] educated by an extreme religious and liberal mother [...]”, helped to undertake actions that transformed her into a midwife with great prestige in the Court (Durocher, 1871b, p. 9). Much of this is the result of her joining as the first woman to be a member of the Imperial Academy of Medicine and to sign medical texts under her own name (Durocher, 1871b). In her speech, she bravely defended that midwives should be educated people, being credited for reformulating the course at the Imperial Academy of Medicine. During her life, Durocher assisted more than 5,000 births, including watching the highness Leopoldina, as she herself liked to refer.

Her book analyzed here, with only 25 pages in total and eight chapters, was organized like this:

Table 1 Organization of the book Ideias por coordenar a respeito da Emancipação

| Topics | Title |

|---|---|

| 1 | Emancipação |

| 2 | Independência do Brazil |

| 3 | Meios da emancipação (4) |

| 4 | Resultado da emancipação gradual |

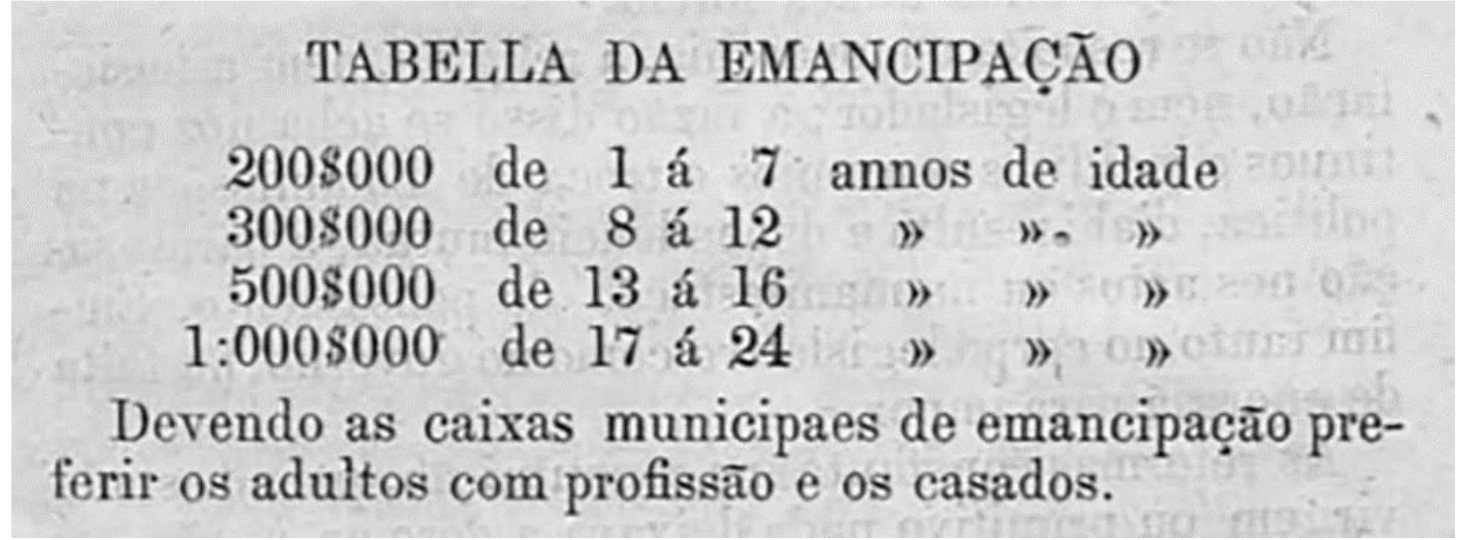

| 5 | Tabela da emancipação |

| 6 | Respostas aos argumentos |

| 7 | Abolição da venda de homens |

| 8 | Algumas ideias a respeito do melhoramento das organizações administrativas e Ministério |

Source: Durocher (1871a).

According to table 1 presented above, the work expressed all her arguments correlating Brazilian political independence and its incompatibility with the slavery of those born in Brazil:

It is clear that the independence was partial and its beneficial effects will not extend to all Brazilians and will only touch those Brazilians who, by a lucky chance of luck, were free and to the children of the Portuguese, leaving a much larger number of Brazilians in the forgotten and consequently in slavery (Durocher, 1871a, p. 6).

For Maria Josephina, in the 1870s, the issue of slave freedom was much more difficult to resolve than at the time of Brazil’s proclamation of independence. In 1822, the Liberals could have decreed the end of slavery, as there were more African slaves than Brazilians and so a decree on the freedom of slaves would not harm work in the fields and would, over time, turn a contingent of free men into “ [...] citizens raised and educated in freedom ”(Durocher, 1871a, p. 7).

In 1870, the number of slaves born in Brazil was 5 million, reflecting the nonsense of a monarchical, constitutional and representative country. For the midwife, the cause of this absurdity was due to three factors: the Portuguese habit of understanding the slave as a thing, the lack of moral education, and the lack of virtue of the slaves so that even freedmen work in the interests of farms of the country, which is also theirs.

This was the problem posed by the author: the sudden emancipation of slaves who had the ideas of revenge against the barbarities committed by their owners. To combat the atrocities of the rebels, only fire against fire would be effective and this would result in death and loss, as they would not have slaves or free men as labor for work. It was necessary, in the state of civilization and freedom that the country was, to take better care of aspects related to the end of slavery and the exercise of freedom of these subjects. This was what she set out to demonstrate through what constituted her project of gradual liberation, divided into four steps, entitled ‘Means of emancipation’. In this way, Brazil’s independence would only be ‘total’, when it reached all Brazilians, which would prevent a future of barbarism and the collapse of the country’s main source of wealth, farming.

Her referred project of gradual liberation would be based on the moral education of slaves, so that they could know how to make use of their freedom, not becoming lazy, thieves or using their freedom in revenge. That would be her first step. For that, there would be the adoption of a code in which their rights and duties were being taught and, likewise, the limit of authority of the owners. The definitions of both would become ‘subordinate’ and ‘superior’, in order to give more dignity to man. This regulation would contain how the relationship between slave and owner would take place. A kind of employment contract, or labor legislation, whose function would be to regulate issues such as food, clothing, days and hours of work, punishments for absences, authorization to leave, rest on Sundays, obligation to practice religion (listen to mass and annual confession). The use of the code, which would be made by an impartial legislator, could bring, according to Durocher, the hope of a better future, calming the rebels and concomitantly with the superiors guaranteeing their authority.

The second step was the creation of a philanthropic tax forcing free people to pay 500 réis per semester or 1000 réis annually, to be destined to the causes of emancipation. Connected to this was the third step, indicating that these resources would be destined for the annual festivities of independence, when the emancipation of one or more slaves would be made, a very common practice in the period, as mentioned above.

In the press, references to these types of celebrations mentioned in the book by Durocher were recurrent. Such celebrations mixed speeches, music, fires and these types of political acts. In the 1885 O Mequetrefe newspaper, a cartoon was published indicating the way in which the City Council drew up its celebration of September 7:

The aforementioned figure 4 honored the City Council because of the way it proceeded with the commemorations on that 63rd anniversary of Brazil’s political emancipation: handing manumission letters to many enslaved people

Two years later, Gazeta de Notícias published an article entitled ‘Sete de Setembro’, in which the celebrations organized by the Sociedade Comemorativa da Independência were described “[...] ‘The city council takes part, freeing 70 slaves’. In bandstands, naval bands and marine empires will play until dawn. Luminous beams on Sto. Antônio hill and correspondent on Praça da Constituição” (Gazeta de Notícias, 1887, p. 1, emphasis added).

In other words, on two separate occasions when the anniversaries of Brazilian political independence were celebrated, the Council proceeded with the release of the enslaved, as suggested by Durocher’s third step. And her fourth step was the formulation of a table that fixed the price of the slave according to age, as outlined in the book and according to figure 5 below:

The last step in Durocher’s project was the execution of a decree that would make all Brazilian-born slaves free. In this sense, for Durocher, the result of partial emancipation would consist in the acquisition, by the slaves, of good customs and morals to the point that the owners would understand the dignity of men by not treating them as things. Thus, the children of the owners would grow up with the tutored minors, and observing the good examples of obedience to the regiment, the practice of justice and humanity would be fixed in future generations:

[...] ennobling the heart of the future generation that will make Brazil a great empire not because of its extension and territorial wealth and favorable geographic position, but because of morals, education, industry and assiduity to intellectual and material work (Durocher, 1871a, p. 17).

At the end of her writings, she suggests that the sale of slaves while it could not be abolished should change names for “[...] transferring inferiors at the price of” (Durocher, 1871a, p. 19) in order to avoid the uprising of the rebels and bring more dignity to man. In addition to this, Durocher still makes considerations about the political administration of the country, because, according to her, the governors were concerned with several issues, leaving them no opportunity to dedicate themselves to those that really mattered for the future of the country, such as the emancipation of slaves.

We note in Durocher’s propositions similarities with Decree Law 2040 of September 28, 1871, the well-known Law of the Free Womb21. The text of the law and the text of the midwife date from the same year, but it is not possible to define in which month the book was released and whether it was before or after the law22. The fact is that, among the similarities, there were similarities of prescriptions regarding the education of minors:

Among the duties imposed on the tutor, education should not be overlooked; minors will go to mutual schools or have hours dedicated to their studies on the farms, education must consist of at least the following: Christian doctrine, Portuguese, Arithmetic, homeland history, and notions about geography, that is, the essential rudiments to have an idea of what is this machine called the world (Durocher, 1871a, p. 14)23.

Therefore, the school would be the fundamental device to execute the plan of moral and intellectual education of the freed slaves, so that they could be civilized, moralized, polished. So that, from the formal practice of schooling, they could understand this machine called the world.

The logic of the emancipation fund “[...] by the capitals of the municipal bank” (Durocher, 1871a, p. 15) is also similar to the article of the law, which says: “Art. 3rd. The number of slaves released each year in each province of the Empire will correspond to the annual available quota of the fund destined for emancipation” (Decree law 2040, 1871). In addition, it is worth noting the relations that Durocher establishes between the country’s political emancipation and slavery, with moral instruction for the use of freedom as an effective solution for release, precisely in the period when the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Seven September.

In general, in that context, the ideas defended by Maria Josephina were put and being widely debated in public spaces, in the city hall, senate and press. The debates involved the understanding of nation projects, civilization, modernity, progress and, notably, slavery appeared as one of the biggest obstacles and backwardness of Brazilian society. For her, these issues were closely intertwined with the status of an independent country, with nation projects, with civilization.

In her view, the work she wrote was justified in her “[...] zeal and patriotism manifested in the desire that always accompanies me to see this beautiful Brazil shine [...]” and in her “[..] good intentions and because I understand that every citizen must contribute with his/her contingent of more or less intelligence, for everything he/she thinks can be useful and contribute to the welfare of the country” (Durocher, 1871, p. 25). Certainly, this was an understanding shared by Mello Moraes when publishing his book, as we will see.

Independence and the Empire of Brazil (1877)

Alexandre José de Mello Moraes was born in the city of Alagoas, in the former capital of the province of the same name, on July 23, 1816 and died at the age of 66, on September 6, 1882 in Rio de Janeiro, due to pneumonia24. He died at the time when he reenacted, for three months, the publication of Brazil Historico and on the eve of the celebration of the Independence of Brazil, a subject so debated in his books on the History of the Fatherland.

When he was orphaned at the age of 11, his education was under the responsibility of his uncles, the Reverends Friar José de Santa Thereza, Carmelite, and Friar Francisco do Senhor do Bomfim, Franciscan, in the province of Bahia, where he studied humanities and as a result at the age of 17 he started teaching rhetoric, geography and other preparatory courses.

Subsequently, he enrolled at the Medical School of Bahia, graduating in 1840, at the age of 24. Mello Moraes stood out as a homeopathic doctor in Brazil, coming to be considered by some as the “[...] physician of doctor and worker of civilization and progress” (Jornal do Commercio, 1882, p. 1). However, his prominence appeared not to be only in medicine, where he made his livelihood. Some printed papers pointed out that it was in the sphere of letters that “[...] he shone with pure and serene light” (O Corsario, 1882, p. 2). His literary career began in 1843, as a writer for Correio Mercantil, a daily newspaper in Bahia, where he defended, as a politician affiliated with the conservative party, the cause of the friends involved in the 1844 revolution in Alagoas. In the following years, he collaborated with several other works, founding in 1845, Mercantil of Bahia, created with the same purpose of Correio Mercantil, in 1853, Medico do Povo, founded with the objective of defending Hahnemann’s homeopathic ideas, of which it once came to be an adversary and, in 1864, Brasil Histórico with a vast repertoire of historical and political documents. In 1868, he was elected general congressperson in the province of Alagoas by the Conservative party, this would have been the only public office held by Mello Moraes25.

Since then, politics, religion, medicine and the physical and natural sciences were daily discussed and published by him in the newspaper and in volumes, including a dictionary of botany. Of his 42 years of study, involving the most varied themes, 30 years have been dedicated to the history of Brazil. During that time, he collected various documents, such as biographies, correspondence, chronicles, newspapers, manuscripts, maps, rare works, pamphlets, processes, scripts, etc. There were more than one hundred letters, in a bound volume, written from José Bonifácio’s own hand, between the years 1822 to 1825, about the influence of independence and, more than 50 works of different subjects and varied formats.

Due to such experience with the universe of the written word, he was also responsible for the creation, in 1859, of the first public library in the province of Alagoas, donating a large number of books from his private library.

The name Mello Moraes makes up the history of Brazilian literature, becoming “[...] inscribed in gold letters, on the ceiling of the Pantheon honor hall, in Paris, as a representative of the history of Brazil” (O Cruzeiro, 1882, p. 4). Despite this recognition, for some, Moraes had not acquired the proper awards in his homeland, even being accused of plagiarism.

Compiler, chronicler, historian, public man, philosopher, Mello Moraes wrote many texts in the form of chronicles, newspapers, memoirs and works. Based on systematic studies, he ordered all documents, which he considered of interest to the history of Brazil. He most distinguished himself in this specialty, in researching, ordering and redistributing these materials. His analyses aimed to bring the ‘true’ light of the political and social events of the time, which, according to him, sought only to elude national good faith.

Among his authorial works, there are Considerações physiologicas sobre o homem e sobre as paixões e affectos em geral (1840); O educador da mocidade brasileira (1853); Ensaio Ccorográfico do Império do Brasil (1853); Physiologia das paixões e afeccões (1854); Memórias diárias da guerra do Brasil por espaço de nove anos (1855); Os Portugueses perante o mundo (1856); Elementos de literatura (1856); Corographia historica, five volumes (1858); Biographia do Senador Diogo Antonio Feijó (1861); O Brasil histórico, four volumes (1861); Apontamentos biográficos do Barão de Cairu (1863); Á posteridade: o Brasil histórico e a corografia histórica do Império do Brasil (1867); Gramatica analítica da língua portuguesa (1869); História do Brasil-Reino e Brasil-Império (1871); O Brasil social e político (1872); História da translação da corte portuguesa para o Brasil em 1807-1808 (1872); Diccionario de medicina e therapeutica homoeopathica (1872); História dos Jesuítas e suas missões na América do Sul (1872); A vida e morte do conselheiro Francisco Freire Alemão (1874); Carta política sobre o Brasil ao Senhor Francisco Lagomaggiore (1875); Phitographia ou botânica brasileira, aplicada á medicina, as artes e á indústria (1878); Crônica geral e minuciosa do Império do Brasil (1879); O tomo das terras dos jesuítas (1880). Added to these, the work that we are interested in analyzing here, was published in 1877, entitled A independência e o Império do Brasil, as shown in figure 6 below:

Fonte: Biblioteca Digital do Senado Federal

Figure 6 Cover of the work A independência e o Imperio do Brazil

The work consists of 388 pages and 101 chapters (some with only 1 page). On it, the author defends the family’s moral and religious education as a solution to a large part of ‘social illnesses’ and points out ‘custom’ as a ‘powerful’ element that should, in his opinion, prevail over human laws, orders and statutes. In order to understand the country’s historical and political scenario, Mello Moraes raised some questions that possibly disturbed political agents and the population in general: “Will Brazil later be a Republic? Was Counselor Dr. José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva the Patriarch of Brazil’s political independence? Did Brazil in its Independence have Patriarchs?” (Moraes, 1877, p. 1).

Thus, it addresses the republican political constitution of the government, in which all the people, or most of them, are expected to exercise sovereignty. However, the practice of slavery and the exemption of rights to some individuals destroyed, “[...] the pure essence, of the pure democratic spirit, which bases all its prestige on the virtue of customs, and on the personal merits of individuals [...]”, because the abuse of the ‘democratic’ government, had made it demagogic - “[...] everyone wants to rule and govern, and nobody obeys” (Moraes, 1877, p. 2).

At the beginning of the work, Mello Moraes reaffirms his commitment to ‘historical truths’, which he claimed to have been falsified by ignorance of some facts. For this reason, the first title of his book is named: “A verdade historica provada pelos documentos authenticos e pelos factos” (Moraes, 1877, p. 1-2).

Thereafter, the author divides his work into subtitles, as shown in Table 2 below:

Table 2 Organization of the book A independência e o Imperio do Brazil

| Topics | Title |

|---|---|

| Geral | A verdade historica provada pelos documentos authenticos e pelos factos |

| 1 | Origem dos governos |

| 2 | Formas de governo Republicano |

| 3 | Governo Monarchico |

| 3.1 | Monarchia |

| 4 | Retrospecto historico |

| 5 | Monarcha |

| 6 | Monarchia simples |

| 7 | Monarchia absoluta |

| 8 | Monarchia electiva |

| 9 | Monarchia hereditaria |

| 10 | Retrospecto historico e politico da Polonia |

| 11 | Soberania |

| 12 | Povo nação |

| 13 | Realeza |

| 14 | Usurpador e tyrano |

| 15 | Tyrania |

| 16 | Despotismo |

| 17 | Soberano |

| 18 | Liberdade |

| 19 | Leis |

| 20 | Justiça primitiva entre os povos da Europa e da Asia (Traduzido da obra de Mr. Aignau) |

| 21 | O povo romano, seu governo e suas instituições |

| 22 | Distribuição do povo e das classes sociais |

| 23 | Dictador |

| 24 | Policia |

| 25 | Enfermidades sociaes |

| 26 | Nacionalidade |

| 27 | Constituição do estado |

| 28 | A França proclama os direitos da humanidade pela Revolução |

| 29 | Os girondinos (extraido dos quadros historicos) |

| 30 | O Brazil nos tempos coloniaes, a imitação dos Estados Unidos, fez a primeira tentativa para a sua Independencia |

| 31 | O Brazil Colonial, O Brazil Reino e O Brazil Imperio |

| 31.1 | Independencia ou morte |

| 32 | A constituição do Imperio que nos foi offerecida em 11 de dezembro de 1823 |

| 33 | Veto |

| 34 | Caracter dos brazileiros e physionomia do Brazil |

| 35 | Independencia do Brazil |

| 36 | Relações do príncipe D. Pedro com José Bonifacio |

| 37 | Castigo barbaro nos soldados portugueses, da divisão de Portugal no dia 30 de setembro de l822 |

| 38 | José Bonifacio concorreu para os desatinos do príncipe D. Pedro - tentativa de assassinato de Luiz Augusto May, redactor do periodico (Malagueta) |

| 39 | Demissão dos andradas no dia 28 de outubro de 1822, e farça ridicula que se deu no dia 30 do mesmo mez |

| 40 | Processo mandado instaurar no dia 30 de outubro, e começado no dia 4 de novembro de 1822 j seguindo a devassa geral em todo o Imperio, contra os inimigos dos Andradas. |

| 41 | Despotismo horroroso do ministro Jose Bonifacio (São documentos officiaes) |

| 41.1 | Decreto de 11 de Dezembro mandando sequestrar os bens dos súbditos de Portugal |

| 42 | Deportação dos Andradas, e historia da charrua « Loconia |

| 43 | Os presos brasileiros são salyos da traição, pela honradez do 2° commandante, José Joaquim Raposo |

| 44 | Dá fundo a Luconia no porto de vigo, e novos perigos se apresentam para os passageiros, que são salvos por intervenção do governo inglez |

| 45 | Providencias tomadas |

| 46 | Desembarcaram os passageiros da Luconia e partem por terra para Bordeaux |

| 47 | Destino da charrua Luconia |

| 48 | São devassados os Andradas, seus amigos e o periodico Tamoyo |

| 49 | Reflexões a respeito do golpe de estado de 12 de novembro de 1823 - o que foram os Andradas e o patriarchado da independencia |

| 50 | O patriarchado da Independencia do Brazil |

| 51 | Quando começou a idéa do patriarchado da Independencia do Brazil, attribuida a J. Bonifacio de Andrada e Silva |

| 52 | Provocações da sociedade militar |

| 53 | Acontecimentos no dia 5 de dezembro de 1833 - demissão do tutor imperial - quebramento das typographias Paraguassu e diario do rio |

| 54 | É accusado o periodico Lafuente e verdadeiro Caramuru |

| 55 | Suspensão do tutor |

| 56 | Nomeação do Marquez de Itanhanhm para tutor interino |

| 57 | Proclamação da Regencia |

| 58 | Prisão de José Bonifacio |

| 59 | Juiso de um contemporaneo sobre José Bonifacio, como operário da Independencia do Brasil, e o seu patriarchado |

| 60 | Exposição dos planos dos restauradores, tendo á sua frente José Bonifacio |

| 61 | Um bonito episodio |

| 62 | O patriotismo dos Andradas apregoado pelos jornaes contemporaneos |

| 63 | Astréa n. 824 de quinta-feira, 26 abril de 1832 - combate dos caramurus |

| 64 | Relação dos paisanos que foram presos no campo da honra, na occasião do ataque do dia 2 de abril de 1832, e que se acham na cadêa |

| 65 | Dissecação politica entre Antonio Carlos e Evaristo Ferreira da Veiga |

| 66 | Extracto do discurso, que proferio na camara dos deputados, em 21 de maio de 1832 o sr. Diogo Antonio Feijó, como ministro da justiça |

| 67 | O Imperador d. Pedro I não foi o fundador do Imperio do Brasil e sim El-rei o sr. d. João VI |

| 67.1 | Revolução de Portugal de 24 de Agosto de 1820 |

| 68 | Desde quando data o pensamento da mudança da côrte Portugueza para o Brazil |

| 69 | Fundação do Imperio brazileiro |

| 70 | O principe regente da conta a seu pai dos movimentos do dia 5 de junho, e se pronuncia contra a causa do Brazil |

| 71 | Pedro aos fluminenses |

| 72 | A provincia de S. Paulo elege a sua junta provisoria |

| 73 | Documentos justificativos - Bellezas do tempo |

| 74 | O que decidiu José Bonifacio de Andrada e Silva, aderir a’ causa no Brazil, antes de ser ministro |

| 75 | Para a deportação |

| 76 | O Imperador mandando processar os Andradas como architectos da ruina da nação em caracter de sediciosos |

| 77 | Regresso dos Andradas do desterro na Europa |

| 78 | Requerimento |

| 79 | Jose Bonifacio fazendo com a sua mão, o seu proprio retrato |

| 80 | Trechos das cartas que tenho a vista |

| 81 | Voltam os Andradas do desterro |

| 82 | Desconcertos e absurdos do governo do Brazil por não conhecer os homens e a Historia do paiz |

| 83 | Serviços dos Andradas a’ causa da patria |

| 84 | Jury da capital |

| 85 | Morte de José Bonifacio |

| 86 | A independencia dos Estados-Unidos da America do Norte, conquistada pelo sangue; e a independencia do Brasil comprada a peso de ouro |

| 87 | Divida de Portugal |

| 88 | José Bonifacio de Andrada e Silva, comparado com Jorge Washington, este libertador da sua patria e o outro Anarchista e patriarcha do que não fez |

| 89 | Origem da corrupção - os partidos politicos no Brazjl e o parlamentarismo, filhos da escola de direito |

| 90 | Physionomia do tempo e desatinos das facções sem nenhuma idéa politica |

| 91 | Escandalos e miserias do tempo |

| 92 | Resposta a’ defeza dos negociadores do emprestimo brazileiro, contra as invectivas do parecer da commissão da camara dos deputados |

| 93 | Emprestimo particular acceitado |

| 93.1 | Despeza annual |

| 94 | Emprestimo publico rejeitado |

| 94.1 | Despeza annual |

| 95 | Declaração |

| 96 | Denuncia contra o ex-ministro da fazenda, visconde do Rio-Branco |

| 97 | Mais um esquife que passa |

| 98 | O desmoronamento |

| 99 | Futuro da monarchia no Brazil |

| 100 | Como se sabe a historia da Independencia |

| 101 | Carta politica sobre o Brazil |

Source: Moraes (1877).

Mello Morais discusses Independence from a political-critical perspective, based, according to him, on documents extracted from libraries and archives. It begins with the origin of governments and their respective forms of action, and ends with a political letter about Brazil.

In political terms, there was a clear distinction: Republican governments were democratic and monarchical government was either despotic or absolute. In this case, it seems to be clear his opposition to the Brazilian political system at the time.

When defending the sovereignty of the people26 in a nation27, Mello Moraes proposed the application of popular education, which would be responsible for forming a national and public character in accordance with predetermined customs. A very valued subject in his work, he brings to light the importance of freedom, the ability to do not what one wants, but what reason advises to be done. Thus, the free man was born, with essential and preserved natural rights, without being deprived of them, fundamentals of justice, equity and security. Therefore, society should establish laws, which would act as rules for all, in order to guarantee social harmony and common benefit. This perspective, in his words, was aroused in men from France with the proclamation of the humanitarian idea contained in the declaration of the rights of man and the citizen.

In addressing Independence, Moraes points out other emancipation processes that preceded the year 1822, as occurred in Minas Gerais (1789), after the news of the revolution in the United States of North America, through two enthusiasts of republican ideas: the Ensign Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, nicknamed Tiradentes and bachelor José Alves Maciel.

As well as problematizing the prominent place given to the date of September 7, 1822, throughout his text, Moraes dismisses some subjects from the position of heroes. And in this case, he instituted another, as is the case of Tiradentes (hanged on April 21, 1792, in the field of S. Domingos in Rio de Janeiro), having the body beheaded and quartered. Electing other important facts, he mentions similar emancipation initiatives in other provinces, such as Bahia, and its protagonists (Cypriano José Barata de Almeida and Marcelino Antonio de Souza) “[...] who in their meetings gave life to freedom and Napoleon”. Or Pernambuco, described as one of the provinces that was dissatisfied with royalty in Brazil and for that reason sought the Republic. In the name of this governmental change, many were hanged and shot, having “[...] their bodies dragged in ponytails, cut off their heads and hands, and exposed in public places, for example of the new conjurations” (Moraes, 1877, p. 64-67).

Still contesting the cry of ‘Independence or death’ on the banks of the Ypiranga, his great objective in the book, Moraes elaborated ten questions for Manoel Marcondes de Oliveira Mello, baron of Pindamonhangaba and travel companion of the prince regent at the time. The latter answered the request in 1862, by means of a letter published by Moraes for the first time in 1864 (in the first series of Brazil historico) and then in his 1877 work, analyzed here. By launching the questions and answers contained in the letter in the work, the historian demonstrates that it was constituted as a document, an oral record. These ten questions were answered by Manoel Oliveira, 40 years after the event, so he admitted that he could have streaked from his memory many facts and circumstances that, possibly, would contribute to the understanding of the Independence process. The fact is that, due to random or deliberate forgetfulness, memory is always selective.

Moraes narrates the creation of the political Constitution project that aimed to establish the governmental separation of the Kingdom of Brazil, Portugal and the Algarves. But, for him, all seven gentlemen who made up the commission in the Constituent Assembly, although honorable, “[...] had no practical knowledge and no experience of the government of men, in order to properly fulfill their mandate” (Moraes, 1877, p. 87). Furthermore, he considered this project to be falsified, since congressmen did not take care of the nation’s interests, consumed time with banal discussions and demoralized the public good, to the point that the government did not consult public opinion, at the same time that the Constitution itself advised them to do it.

This time, before a Constituent Assembly, according to him, “[...] composed of ambitious old people, accustomed to the absolute regime, and of young people without experience [...]”, Brazil’s political independence became a lie in this respect (Moraes, 1877, p. 98).

Faced with this socio-political context, he described that Brazilians, these “[...] enthusiasts of the beautiful ideal, and friends of freedom” (Moraes, 1877, p. 100) were unhappy with the representatives of politics. Thus, asks: “Counselor José Bonifacio de Andrade e Silva28, was the Patriarch of Political Independence of Brazil? Did Brazil in its Independence in 1822 have Patriarchs?” (Moraes, 1877, p. 100). Although Bonifácio was consecrated in history as patriarch of Independence, for Moraes he was against it because of pecuniary interests, as he denounces: as a pensioner of the State and because he received the royal treasury of 18 thousand cruzados, “[.. .] the uncertainty about changing the new order of political things did not suit him; but it is known that his brother Antonio Carlos, constantly wrote to him from Lisbon, in favor of the cause of Brazil ”(Moraes, 1877, p. 257-258).

Questioning the political power exercised by him, Moraes states that to deny Andradista (a kind of faction, political party created by Bonifácio), was to be “[...] considered ‘demagogue’, ‘anarchist’, ‘republican’ and ‘conspirator’; and when they were out of power, the rulers were ‘despots’, ‘tyrants’, and against those who fought war of death” (Moraes, 1877, p. 104, emphasis added). Therefore, he was “[...] a despot who did not choose the means to pursue his ends, and even destroy his enemies’. As an example, he cites the case of the copywriter of the Correio do Rio de Janeiro, João Soares Lisboa, who was censored and put in prison for being liberal and, while in prison, he was ordered to leave Brazil (Moraes, 1877, p. 133-136).

The author strongly attests to the practices of persecution exercised by José Bonifácio to everyone who opposed his official acts29:

At the head of the government, when Brazil was moving to consolidate its independence, it undermined the individual freedom of the people and human reason. He has to deport thirty-odd people from the most influential of his own province, for opposing his brother; he ordered prosecutions for imaginary crimes; he had ordered to beat and arrest journalists, as he did on June 6, 1823, against Luiz Augusto Mey, which almost killed him and crippled for life. For pride and vanity, he always put his person on par with that of the sovereign. As an uncritical man, he listened to all those around him, committing therefore madness without consulting conveniences (Moraes, 1877, p. 136).

In his view, it was a construction historically forged, since, alongside names like José Bonifácio, many competed for the post of patriarchs of Independence, Brazilians and Portuguese. An Independence that had already been prepared before in Rio de Janeiro and, later, in São Paulo and Minas Gerais, on December 23, 1821, when the patriots of Rio de Janeiro provided for the retention of the departure of the prince regent and obtained the right consent, of ‘fico’.

As an indication of a historical construction, it is observed that until the year 1832, there was no mention of the patriarchate of independence in Brazil, “[...] because those who had competed directly and enthusiastically for it, did not want to adorn themselves with that pompous title [...]” and that “[...] it was not up to anyone, because the independence of Brazil was the supreme idea of all Brazilians and of many Portuguese” (Moraes, 1877, p. 137- 138).

Moraes also records that despite this title directed to José Bonifácio, he was suspended from the exercise of tutoring the Emperor and his sisters, by means of a letter from the Regency addressed to him on December 15, 1833. This request from the government would only be obeyed by force by Bonifácio, because he considered him unjust, despotic and premeditated, and if executed it would only serve to shame the Empire. On the other hand, the Regency maintained the action and ordered all the presidents to be informed of the dismissal of the advisor José Bonifácio as tutor to the “[...] imperial boys” (Moraes, 1877, p. 151).

According to Moraes’ narrative, José Bonifácio resisted the summons made by the peace judges, passing the tutelage of the imperial boys to the Marquis of Itanhannem and, therefore, Captain João Nepomuceno Castrioto was ordered to arrest him. Soon after being arrested, Bonifácio was sent to the island of Paquetá and by a resolution of the Congressional Chamber, of May 27, 1834, the removal of the tutoring of imperial boys was confirmed and on July 5, he appeared before the jury Court to answer for his crimes. He was defended by Dr. Candido Ladisláo Japiassú de Figueira e Mello and obtained his acquittal.

In this work, it was very clear that Mello Moraes sought to deconstruct the scream of Independence, which reverberated throughout the Brazilian territory and won over to the images of patriarchs, as history tried to establish through the most different memorable official writings of the time and the press. In its version, history was a result of the cooperation of patriotic citizens rather than a reflection of the action of a single political agent, Dom Pedro I.

Likewise, he endeavored for his writing to deconstruct the election of José Bonifácio as the representation of this Independence, questioning the condition raised by him, pointing out that the patriarch had not received such glory for the fact of being Minister of the State, because if so his other colleagues would also have the same right.

In addition, he concludes that Independence was a political lie because Brazil was given as a donation to the government of Portugal, to those who preceded them, as remuneration for services, reserving the Crown only the right to govern, “[...] claiming some properties (urban, territorial, commerce, navigation, etc.) [...]” and that these were “[...] bought by Brazilians to the crown of Portugal, for 2 million pounds sterling, at the time when he recognized the ‘nominal’ Independence” (Moraes, 1877, p. 360, emphasis added)

In his penultimate title (chapter ‘As we know the history of Independence’), Mello Moraes indicates some ways of circulating his work, thus showing possible readers of his ‘true history’ about the political process of emancipation in Brazil. He publishes in its entirety a correspondence with the Commemorative Society for the Independence of the Empire, dated October 21, 1872 (year of the fiftieth anniversary). In correspondence, the Society requests donation of copies of his works, in which the “[...] worthy author, who quotes with truth and thoroughness those facts” (Moraes, 1877, p. 353-354). His positive response, also published in the book, records the sending of his works and notes: “My work will justify what I say, indicating the sources on which I based the truths I wrote, to say to those to come: About this glory, I am only happy. That I loved my land and my people” (Moraes, 1877, p. 353-354). Then, ‘thanking the proof of consideration, which he has just received’, the President of the Society, Américo Rodrigues Gambôa, takes the opportunity to report to Mello Moraes a request from the Municipal Chamber of the Court so that he could collaborate with a recently approved project (March 1873):

In a session of March 15th of this year, this chamber resolved, by the unanimity of its members, to complete the thought, which presided over the creation of municipal schools, establishing a library in the city hall of this court. Desirous of carrying out this idea of such great reach and profit, this very illustrious Chamber asks for your valuable assistance, and asks you, as a cultist of letters and sciences, ‘deign to donate to the nascent library with a copy of each one of your productions’, for which you have been recommending so much for in the world of letters and to the gratitude of the country, which is proud to count you as one of its beloved sons. Counting on the feelings that ennoble you, please, you accept the most sincere thanks that this chamber sends you, for the much that you hope will do in favor of the instruction of the youth of Rio de Janeiro, for whom, mainly, the municipal library is created. (Moraes, 1877, p. 352-356, emphasis added).

In naming the chapter of the work ‘As we know the history of Independence’ and narrating in it some evidence of the circulation, reading and adoption of this book (and the others), Mello Moraes seems to want to make evident the paths by which it would be possible to spread knowledge that he treats as true about this episode of national political history. How do you know the history of independence, anyway? Writing and narrating the truth with sources and circulating (donation to society) or making available (municipal library) what was written, making this truth public. And it cannot be neglected that the aforementioned project approved by the Chamber was intended for “[...] the instruction of the youth of Rio de Janeiro, for whom, above all, the municipal library is created” (Moraes, 1877, p. 356).

This time, even though it has not been adopted as a school textbook for official education, the fact that it is being ‘adopted’ as one of the rest of the set of investments in a public library aimed at training young people, can highlight important aspects of use, reading and circulation of this type of knowledge about the history of Brazil - contrary to established heroes (José Bonifácio), to legitimate scenarios (Ipiranga River), and other narratives established by official history.

Final considerations

A Brazilian and a naturalized Brazilian woman, public persons, endeavored in the task of thinking about the history of Brazil from its condition as an independent nation, developing narrative strategies to reveal certain perspectives of progress, politics, civility, truth, education, freedom, past, present and future. Neither of the two works makes reference to the fiftieth anniversary of national independence, even though they are being published in the context of such ephemeris (1870s). Perhaps it is quite clear that both were not written to celebrate, but to surprise, review, criticize, set limits and delays that would mark the country in its emancipated condition.

In this sense, both works relate the incompatibility of independence with slavery, understood as barbarism in the scenario of civilization. Central aspect in the book by the midwife Durocher, the permanence of the condition of a slave country made independence a lie, a partial emancipation. Reason for her to write 25 pages for the Assembly, containing ideas, projects and political, educational and social solutions for reviewing the Brazilian scenario. In Mello Moraes, slavery was not a major concern, it was related to the issue of the exemption of rights for some individuals, which would destroy ‘the pure essence, of the pure democratic spirit’.

With regard to the educational aspect, Durocher defended formal education as the path to the gradual process of emancipation of the slave, understanding that knowledge, the lights of instruction, would be the effective device against the misuse of freedoms. Meanwhile, Mello Moraes exercise in reviewing and rewriting a history of the process of political emancipation in Brazil constituted specialized knowledge for the formation and instruction of youth in Rio de Janeiro.

In the same way, we cannot avoid an analysis that understands the book itself as an educational and cultural experience. The production and uses of such works represent the circulation of ideas, knowledge, representations and perspectives that (un)form, instruct. As Antônio Almeida de Oliveira observes, in his book O Ensino Público “[...] the book is one of the engines of the world, or that its influence comprises the material, moral and intellectual life of peoples. Man, educate yourself in the experience that the book represents” (Oliveira, 2003, p. 273).

Therefore, interested in the ‘experience that the book represents’, we brought to the analysis two investments aimed at reflecting on this historical, social and political landmark of the country, articulating its problem with education. Adding efforts to those of researchers who have been thinking about Independence from the perspective of its bicentenary, we seek to surprise, question, reveal or denaturalize certain perspectives that time, subjects, history, institutions forged about them, about us.

REFERENCES

Alonso, A. (2015). Flores, votos e balas: o movimento abolicionista brasileiro (1868-1888). São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

O Corsario. (1882, 16 de setembro). [ Links ]

O Cruzeiro. (1882, 7 de setembro). [ Links ]

O Cruzeiro . (1882, 23 de setembro). [ Links ]

Decreto lei nº 2.040, de 28 de setembro de 1871. Declara de condição livre os filhos de mulher escrava que nascerem desde a data desta lei, libertos os escravos da Nação e outros, e providencia sobre a criação e tratamento daquelles filhos menores e sobre a libertação annaul de escravos... Recuperado de: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lim/lim2040.htm [ Links ]

Diario do Brazil. (1882, 7 de setembro). [ Links ]

Durocher, M. J. M. (1871b). Deve ou não haver parteiras? Anais Brasilienses de Medicina, 22(9). [ Links ]

Durocher, M. J. M. (1871a). Ideias por coordenar a’respeito da emancipação. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Typographia do Diario do Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Galvão, M. A. (1894). Relação dos cidadãos que tomaram parte no governo do Brazil no periodo de março de 1808 a 15 de novembro de 1889. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora: Imprensa Nacional. [ Links ]

Gazeta da Tarde. (1882, 7 de setembro). [ Links ]

Gazeta de Notícias. (1875, 08 de outubro). n. 68, p. 1. [ Links ]

Gazeta de Notícias . (1887, 07 de setembro). p. 1. [ Links ]

Jornal do Commercio. (1882, 7 de setembro). n. 249, p. 1. [ Links ]

Maria Josephina Mathilde Durocher. (2020). Recuperado de: http://www.anm.org.br/conteudo_view.asp?id=574&descricao [ Links ]

A Marinha de guerra do Brasil na lucta da independencia: apontamentos para a historia. (1880). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Typ. de J. D. de Oliveira. [ Links ]

O Mequetrefe. (1885, 10 de setembro). n. 385, p. 2. [ Links ]

Moraes, A. J. M. (1877). A independencia e o Imperio do Brazil. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Typ. Universal de Laemmert. [ Links ]

Mott, M. L. B. (1994). Madame Durocher, modista e parteira. Revista Estudos Feministas, 1(2), 101-116. [ Links ]

Nicolau, G. P. (2018). Hasteando a bandeira tricolor em outros cantos: a imigração francesa no Rio de Janeiro (1850-1914) (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói. [ Links ]

Nora, P. (1993). Entre memória e história. A problemática dos lugares (Yara Aun Khoury, trad.). Revista História e Cultura, 10, 7-28. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. A. (2003). O ensino público. Brasília, DF: Senado Federal. Conselho Editorial. [ Links ]

Pollak M. (1989). Memória, esquecimento, silêncio. Estudos Históricos, 2(3), 3-15. [ Links ]

Rebouças, A. P. (1879). Recordações da vida patriótica. Rio de Janeiro: Typ. G. Leuzinger Filhos. [ Links ]

O sete de setembro de 1857: tributo a memoria dos heroes da independencia do imperio do Brasil. (1857). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Paula Brito. [ Links ]

Silva, J. M. P. (1864). Historia da fundação do imperio brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: B. L. Garnier. [ Links ]

Souza, J. R. (1867). Analyse e commentario da Constituição politica do Imperio do Brazil, ou, theoria e pratica do governo constitucional brasileiro. São Luiz, MA: Editora: B. de Mattos. [ Links ]

17The analysis of each work will be based on the chronological order of its publication (1871 and 1879, respectively).

18The gradual abolition of slavery went through the following laws: the Eusébio de Queirós Law of 1850, followed by the Law of the Free Womb of 1871 and the Sexagenarian Law of 1885.

19Writing on the cover of the book by Durocher Ideias por coordenar a’ respeito da emancipação of 1871.

21In the proposition of the midwife released, slaves born in Brazil would have the owner as their tutor and this would have the duties of tutoring supervised in each parish and village by a responsible person, in order to see how minors were treated, and tutors could be punished in law when abuses were found. The age of majority would be at the age of 25 in order to indemnify the guardian by means of work. And because at this age, he/she could already employ him/herself with experience in some branch of work and guide his/her morality by managing to obey the law.

22It is not possible to know on what exact date Madame Durocher’s book was published and not even if her suggestions were in any way incorporated into the law enacted on that September 28, 1871. However, it is possible to consider that somehow the midwife’s reflections influenced the discussions by deputies from the conservative and liberal parties who argued for several months the proposal of the conservative cabinet chaired by the Viscount of Rio Branco on May 27, 1871, and the friendship between Durocher and the baron of Cotegipe could be a route for such repercussion.

23In the letter of the law, such proposal is described as follows: “art. 1st: The children of the slave woman who were born in the Empire since the date of this law, will be considered free condition. §1. Said minor children will remain in power and under the authority of their mothers’ owners who will have an obligation to raise and treat them until the age of eight years. When the minor arrives at this age, the owner of the mother will have the option, either to receive from the State an indemnity of 600$000, or to use the services of the minor up to the age of 21 years old” (Decree law 2040, 1871).

24He married Maria Alexandrina de Mello Moraes and had four children, he died at 4:30 pm on September 6, 1882. His body was transported inside a coffin, from his son’s house, located at rua Rezende, 78, to the São João Baptista cemetery to be buried at 4 pm (O Cruzeiro, 1882; Diario do Brazil, 1882).

25According to the newspaper Gazeta da Tarde (1882), the government had refused Mello Moraes the position of chronicler of the Empire, to which he would serve free of charge. In return, Moraes published his works in the columns of that newspaper.

26People is “[...] the multitude of men from all social classes, from the same country, and from the same race” (Moraes, 1877, p. 12).

27Nation is “[...] the set of men and families, having a common origin, living in the same territory, under the same laws, with their own uses and customs and the same language” (Moraes, 1877, p. 12).

28Counselor José Bonifacio de Andrada e Silva graduated from the University of Coimbra, where he worked as a professor of metallurgy, later being appointed general intendant of the kingdom’s mines and metals, superintendent of the Mondego River and public works. When he retired from the position of professor, he went to live in Lisbon, and shortly thereafter he was called to exercise the function of secretary of the Royal Academy of Sciences. Finally, he was invited to be rector of the new University that would be created in Brazil (Moraes, 1877).

29José Bonifacio, was called by the prince regent of ‘my father’, “[...] to the point of going with the princess every day, to her house, in the square of Rocio, today Square da Constitution, corner of Sacramento, have lunch, and where they led to talk, and even went out for a walk together” (Moraes, 1877, p. 133).

How to cite this paper: Silva, E. O. C., Santos, A. M., Nascimento, F. A. N., & Limeira, A. M. ‘For lighting the past’: books and education in the context of the fiftieth anniversary of theIndependence (brazilian capital, 1870s). (2020). Brazilian Journal of History of Education, 20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e126 This paper is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC -BY 4).

2A análise de cada obra se dará a partir da ordem cronológica de sua publicação (1871 e 1879, respectivamente).

3A abolição gradual da escravidão passou pelas seguintes leis: Lei Eusébio de Queirós de 1850, seguida pela Lei do Ventre Livre de 1871 e a Lei dos Sexagenários de 1885.

6Na proposta da parteira sendo libertados os escravos nascidos no Brasil teriam o senhor como tutor e este os deveres da tutoria que seriam fiscalizados em cada freguesia e vila por um responsável, a fim de ver como os menores eram tratados, podendo os tutores serem punidos na lei quando abusos fossem decretados. A maioridade seria aos 25 anos a fim de indenizar por meios do trabalho o tutor. Porque também nesta idade já poderia se empregar com experiência em algum ramo do trabalho e guiar a sua moralidade conseguindo obedecer à lei.

7Não é possível saber em qual data exata o livro de madame Durocher foi publicado e nem mesmo se suas sugestões foram de alguma forma incorporadas a lei promulgada naquele 28 de setembro de 1871. Contudo é possível cogitar que de alguma maneira as reflexões da parteira influenciaram as discussões dos deputados dos partidos conservador e liberal que argumentavam por vários meses a proposta do gabinete conservador presidido pelo Visconde do Rio Branco em 27 de maio de 1871, podendo ser a amizade entre Durocher e o barão de Cotegipe uma via para tal repercussão.

8Na letra da lei tal proposta aparece descrita da seguinte forma: “art. 1º: Os filhos da mulher escrava que nascerem no Império desde a data desta lei, serão considerados de condição livre. §1. Os ditos filhos menores ficarão em poder e sob a autoridade dos senhores de suas mães, os quais terão obrigação de criá-los e tratá-los até a idade de oito anos completos. Chegando o filho da escrava a esta idade, o senhor da mãe terá a opção, ou de receber do Estado a indenização de 600$000, ou de utilizar-se dos serviços do menor até a idade de 21 anos completos” (Decreto lei nº 2.040, 1871).

9Casou-se com Maria Alexandrina de Mello Moraes e teve quatro filhos, faleceu às 16:30 horas do dia 06 de setembro de 1882. Seu corpo foi transportado dentro de um caixão, da casa de seu filho, localizada na rde Rezende, 78, até o cemitério São João Baptista para ser enterrado às 16 horas (O Cruzeiro, 1882; Diario do Brazil, 1882).

10Sua mãe faleceu em 20 de novembro de 1826 e seu pai em 13 de maio do ano seguinte (O Cruzeiro, 1882).

11Segundo o jornal Gazeta da Tarde (1882), o governo havia recusado a Mello Moraes o cargo de cronista do Império, o qual iria servir de forma gratuita. Como contrapartida, Moraes publicou seus trabalhos nas colunas do referido jornal.

12Povo é “[...] a multidão de homens de todas as classes sociaes, de um mesmo paiz, e de uma mesma raça” (Moraes, 1877, p. 12).

13Nação é “[...] o conjunto de homens e de famílias, tendo uma origem commum, vivendo sob o mesmo territorio, sob as mesmas leis, com usos e costumes proprios e a mesma linguagem” (Moraes, 1877, p. 12).

14O conselheiro José Bonifacio de Andrada e Silva formou-se na universidade de Coimbra, onde chegou a atuar como professor de metalurgia, sendo depois nomeado intendente geral das minas e metais do reino, superintendente do rio Mondego e obras públicas. Ao se aposentar do cargo de professor foi viver em Lisboa, e logo depois foi chamado para exercer a função de secretário da Academia Real das Ciências. Por fim, foi convidado para ser reitor da nova Universidade que seria criada no Brasil (Moraes, 1877).

15José Bonifacio, era chamado pelo príncipe regente de ‘meu pai’, “[...] a ponto de ir com a princeza todos os dias, para sua casa, no largo do Rocio, hoje Praça da Constituição, esquina da do Sacramento, almoçar, e onde levavam a conversar, e mesmo sahiam juntos a passeiar” (Moraes, 1877, p. 133).

Received: June 14, 2020; Accepted: June 26, 2020

texto em

texto em